Introduction

User participation as a concept appeared in the welfare sector in Europe in the 1990s (Askheim et al., Reference Askheim, Christensen, Fluge and Guldvik2017). In the municipal care services in Norway, user participation has increased in importance over time. Generally, the legislation and the national policy documents express that ‘service users have a democratic right as citizens to influence their care’ (Askheim et al., Reference Askheim, Christensen, Fluge and Guldvik2017: 597). How the users are able to exert an influence in practice will to a certain degree be decided by the relation between the user and the care workers. However, this relationship takes place within certain structures that constitute the framework for how the user influence can be expressed and what the users may influence. In the service-delivery process, there are different structural factors that affect the users’ possibilities for influence. I refer to this with the phrase ‘the scope of possibilities for user influence’, which I have developed through the analysis of the data material. The shaping of these structures will be related to models of governance with associated user typologies (Osborne, Reference Osborne2010; Fotaki, Reference Fotaki2011; Dent and Pahor, Reference Dent and Pahor2015; Askheim et al., Reference Askheim, Christensen, Fluge and Guldvik2017).

This article has its basis in a study of municipal care services for adults, comprising home-based services (home help and home nursing), nursing homes and care services for persons with intellectual disabilities. The data set consists of interviews with managers at different levels of these areas of services, and it is the managers’ experiences and considerations that have been studied. The research question asked is as follows: How do the managers consider user influence, and how do structural factors in different care services affect the possibilities for user influence? The structural factors will be discussed in relation to different user typologies.

The Norwegian context

Like the other Nordic countries the Norwegian welfare state is extensive compared with other welfare states (Kautto et al., Reference Kautto, Fritzell, Hvinden, Kvist and Uusitalo2001). The Nordic countries are characterised as service states and care services are mainly organised as public services, not as cash benefits (Bambra, Reference Bambra2005). The development of the welfare state has resulted in Norwegian municipalities being responsible for an increasing number of welfare services, regardless of their size. The municipalities have the full responsibility for the provision of both institutions and home-based care services for their inhabitants. The municipal care services have grown increasingly and currently constitute a larger proportion of the care provision than the family-based caring (Otnes, Reference Otnes and Ramm2013). Older people make up a large majority of the users at nursing homes (90% are more than 67 years old). In the home-based services there is a wider age distribution, where older people constitutes about 60 per cent (Kjelvik and Mundal, Reference Kjelvik, Mundal and Ramm2013).

Traditionally, Norwegian municipalities have had extensive autonomy in how they meet their obligations to provide welfare services, but the state exerts significant control through legislation and grants (Pierre and Peters, Reference Pierre and Peters2000). Still, the municipalities retain extensive autonomy concerning the organisation of services and the choice of the kinds of competences that are needed to fulfil the welfare tasks (Tranvik and Fimreite, Reference Tranvik and Fimreite2006). There are several laws regulating user participation in the municipal care services. On the individual level the most important is the Patients’ and Users’ Rights Act, which says that the user is entitled to participate in both the allocation and the provision of services, and that the user’s opinion must be taken into consideration when designing the services (Pasient- og brukerrettighetsloven §3-1). This comprises the existence of processes and measures which allow the users to express their wants (user participation), but also that their wants should have consequences in the design and provision of services (user influence).

The allocation of care services is defined as an ‘individual decision’ (ID), that is, an administrative decision relating to the rights or duties of one or more specified persons, and is regulated by the Public Administration Act (Forvaltningsloven). This law has some formal requirements for IDs: they must be in writing; the grounds must be stated; and they must include information about both the procedures for appeals and how decisions can be reversed. The state regulations provides the frameworks and recommendations towards the municipalities. Nevertheless, in practice there is considerable latitude concerning user influence at the local level. The procedural regulations founded in the law implies that the ‘allocation of services’ can be distinguished as a separate function in the service-delivery process. In accordance with the single-purpose approach associated with New Public Management (Hood, Reference Hood1991), many municipalities have separated these functions into different organisational units (Vabø and Szebehely, Reference Vabø, Szebehely, Anttonen, Häikiö and Stefánsson2012). They have established an allocation unit separate from the providers of the services as a purchaser-provider model (PPM). Whether they have these functions organised in separate units or not, we can identify the two functions as two different stages in the service-delivery process. There is first an allocation of services, which is formulated in an ID in writing, and then the provision of services follows. Each municipality must decide if municipal providers will provide the care services exclusively or allow private providers to operate through user choice of provider or through tendering. The number of municipalities with private providers is low (Vabø et al., Reference Vabø, Christensen, Jacobsen, Trætteberg, Meagher and Szebehely2013). The majority of municipalities with a PPM have implemented this model in a regime with in-house providers of services.

Theoretical perspectives on individual adjustments of services

An essential component in a user-oriented perspective is that the services ought to be individually adjusted (Wistow and Barnes, Reference Wistow and Barnes1993; Newman and Vidler, Reference Newman and Vidler2006). It is important to distinguish between two aspects of individual adjustment of services. The first aspect concerns individual adjustment based on what the service user wants, namely, user influence. Both the legal formulations and the scholarly definitions express the users’ obligatory participation and influence in the designing and provision of services (Hanssen et al., Reference Hanssen, Humerfelt, Kjellevold, Norheim, Sommerseth and Hanssen2010). The second aspect covers what the user needs, which is based on a professional assessment of what the user can do him- or herself and what assistance the user requires. The exercise of professional discretion includes both the ‘wants’ and ‘needs’ aspects (Hanssen et al., Reference Hanssen, Humerfelt, Kjellevold, Norheim, Sommerseth and Hanssen2010).

One approach to the abovementioned aspects of individual adjustment of services is to distinguish between user typologies based on different understandings of the users and the user-provider relation (e.g. McLaughlin, Reference McLaughlin2009). I shall distinguish between (1) the traditional understanding of the user as a receiver of services (client), (2) the market-oriented understanding of the user as a customer and (3) the understanding of user as co-producer of services. These categories are also denominated as ‘voice’, ‘choice’ and ‘co-production’, reflecting a ‘deliberative’, ‘consumerist’ and ‘participative’ concept of user involvement, respectively (Fotaki, Reference Fotaki2011; Dent and Pahor, Reference Dent and Pahor2015; Andreassen, Reference Andreassen2018).

The traditional, paternalistic perspective, where the professional is the expert who knows best what the user needs, emphasises the allocation of services based on an assessment of needs. Accordingly, the service-delivery would emphasise both formalised guidelines and the standardisation of practices, and the users would be expected to trust the professionals’ expertise (Wistow and Barnes, Reference Wistow and Barnes1993; Fledderus et al., Reference Fledderus, Brandsen and Honingh2014). The user is designated as the ‘client’ and the professional has power to identify what the passive client needs (McLaughlin, Reference McLaughlin2009). With the increased importance of user participation, clients are supposed to be more active and to have the opportunity to influence the services through ‘voice’ (Hirschman, Reference Hirschman1970). The service users should have a say in the design and provision of services, though these must remain within the bounds of the traditional welfare-delivery system.

In the market-oriented understanding of the user as a customer, the individual’s influence is stressed: individual adjustments are put into practice through user influence. This perspective takes users to be rational individuals with pronounced preferences. The individual user must gain power at the expense of the professional (McLaughlin, Reference McLaughlin2009; Fledderus et al., Reference Fledderus, Brandsen and Honingh2014). This zero-sum understanding is based on the notions of professionals having self-interests and of conflicts of interests that inevitably arise between the professionals and the users (Newman and Vidler, Reference Newman and Vidler2006). Distrust characterises this relationship (Fledderus et al., Reference Fledderus, Brandsen and Honingh2014). Increased leeway for the professionals through the wider exercise of discretion may increase the power of professionals to further their own interests (Tummers and Bekkers, Reference Tummers and Bekkers2014). This calls for a limitation of professionals’ exercise of discretion. Competition between providers is supposed to increase quality and to give more user-oriented services because the users may choose to leave if they are unsatisfied (Hirschman, Reference Hirschman1970). Even though many highlight the choice of provider as important in this perspective, there are also other ways of securing the customer’s power in relation to the professional. Wistow and Barnes (Reference Wistow and Barnes1993) mention increased individual rights to services and the right of appeal as well as the development of service declarations that ensure predictability in the service-delivery.

In understanding the user as a co-producer, the emphasis is on the balance between the two aspects, implying that user influence and professional assessments in combination put the individual adjustment into practice. The users may have insufficient information about the services and are possibly insecure about their needs and preferences. Therefore, a dialogue about the services available and how to deliver them is necessary. In this dialogue, the professionals need to be concerned with activating the user’s own resources in the service production so that the public effort can supplement the user’s own efforts with the intention of help to self-help. The relationship between the professionals and the users is largely based on trust (Fledderus et al., Reference Fledderus, Brandsen and Honingh2014). Both parties have complementary competences and each contributes to the development of services through dialogue. This implies that both users and professionals must be empowered and the professionals being ‘able and confident to share power and accept user expertise’ (Needham and Carr, Reference Needham and Carr2009: 1). Professional discretion is important because it increases the leeway to adjust services to each individual user. However, the harmonious perspective, where the service users and the care workers have similar interests in the activation of the users’ own resources, is questionable. There may be tensions between the actors because the ‘needs’ and ‘wants’ can be contested concepts (Newman and Vidler, Reference Newman and Vidler2006: 204). There may even be situations where the pressure for activation and participation can result in the disempowerment of the users (Fotaki, Reference Fotaki2011; Dent and Pahor, Reference Dent and Pahor2015; Christensen and Pilling, Reference Christensen and Pilling2019). Dent and Pahor (Reference Dent and Pahor2015) identify three possible negative consequences of co-production that can contribute to this disempowerment. It may be a form of pressure to accept solutions that the professional providers suggest (‘forced responsibilisation’), subordination under a paternalistic relation (‘proto-professionalism’), or manipulation through education and guidance (‘manipulation’).

In summary, when the users are understood as clients, one can expect more paternalism and emphases on professional discretion, a focus on ‘needs’ over ‘wants’, and a standardisation of services and influence through ‘voice’. In the customer perspective, influence through ‘choice’ will be important, ‘wants’ overshadow ‘needs’, and there will be a reduction of professional discretion. The view of the user as co-producer will emphasise influence through dialogue, a mix of ‘needs’ and ‘wants’, power sharing between users and professionals and expectations that the users will take an active part in the delivery of services.

Furthermore, this will have an impact on the opportunities for the users to influence the services. I have developed the phrase ‘the scope of possibilities for user influence’ in order to characterise the latitude that established structures have for the users’ possibilities to exercise their influence on allocation and provision. This may include policy design, organisational features and professional norms and culture (Meyers and Vorsanger, Reference Meyers, Vorsanger, Peters and Pierre2007). Examples of features of policy design might include menus of municipal services or a service structure that is designed to make possible the choice of different services. Next, turning to the structural features or processes that characterise the service-delivery system as an organisation (Scott, Reference Scott2003), we have both a formal structure that includes rules, standardisation and other instruments of control that regulate behaviour, and an informal structure of norms and values developed among the care workers through their interactions. The latter is visible in their creation of informal patterns of behaviour, or coping mechanisms, through which they manage the contradictions of their work (Brodkin, Reference Brodkin and Hasenfeld2010; Meyers and Vorsanger, Reference Meyers, Vorsanger, Peters and Pierre2007). Thus, the structural features that define the scope of possibilities for user influence includes structural or institutional frames that the actors regard as given, natural and fixed in the short run. At the same time, it is not a deterministic situation; there is a certain latitude for actors to interpret what is possible within the frames. However, we can concur with Scott (Reference Scott2003) that practitioners’ discretion is clearly circumscribed because of the subordination to an administrative framework and that managerial control systems have increased.

Method and material

This article is based on a study of five Norwegian municipalities chosen according to organisation, size and geographical location. We chose municipalities that organise health and care services with a PPM and municipalities with a traditional organisation, where the same unit is responsible for both purchasing and providing the services. Further, we included municipalities in the sample with organisational variations of the different service areas. The municipalities in the sample differ according to size and geography in order to reflect the significant autonomy and large variations in size that Norwegian municipalities have. Table 1 gives an overview of the sample of municipalities, which have been anonymised.

Table 1. The sample of municipalities

Fjord city has adopted a PPM with a market; there are private providers in addition to the municipal providers in some of the service areas. In the two other municipalities with PPM there are only municipal service units. Mountain village had recently changed from a traditional organisation to a PPM when the study took place.

This study involved individual interviews with managers at different levels of the health and care services and one focus-group interview in each of the municipalities within a period of one and a half years (2015 and 2016). The number of individual interviews was 37, varying from five to ten in each municipality, depending on size and the way of organising the service apparatus. The majority of the informants were women (86%). More than half of the informants were nurses and many of them had further education in management and administration.

The individual interviews were semi-structured with an interview guide organised thematically. The main themes included how the managers experienced and considered user participation and user influence, both in general and within their own service areas in particular. The focus-group interviews took place after the individual interviews and included four or five of the informants from the individual interviews in each municipality. The groups consisted of managers from different service areas and the head of the allocation unit in the municipalities with PPM. These interviews addressed two main themes: the possibilities for user influence in the allocation and the provision of services and the development of user influence over time.

One might argue that the study has a significant limitation because service users were not interviewed. Their views of these themes might have brought a more complete picture of the possibilities for user influence. However, I argue that the managers’ considerations have provided essential data for the examination of the scope of possibilities for user influence. They were able to describe and evaluate the frames and structural factors concerning the allocation and the provision of services and the room they give for user influence. To a lesser extent these analyses formed the basis of drawing conclusions about the actual user influence. Many of the managers, however, have extensive experience from working in the field, so they might be able to evaluate the development of user influence over time. The managers also have the responsibility for practices in place. The heads of the allocation units could evaluate what the users may influence and how this developed over time. To a lesser extent, they are able to evaluate the actual user influence in the single cases. Similarly, the managers responsible for the provision are able to evaluate what the users wish to influence on the basis of what they discuss within the service area. They have, however, less insight into the practice of user influence in daily service-delivery situations.

I have conducted a content analysis of the data (Wilkinson, Reference Wilkinson and Silverman2016) by alternating between analysing the total picture and delving deeper into specific areas. I began by identifying the themes that appeared in the material as a whole, and then I identified the differences and similarities across the municipalities as well as within each municipality. Next, the analysis became more goal-oriented towards the different themes and sub-themes that came to the fore throughout the first analysis. The analysis has been an ongoing interpretation between raw data, sub-themes and themes developed through the coding of the material into categories and sub-categories. This methodological approach provided opportunities for finding and describing patterns and structures and for focusing on similarities and differences (Rapley, Reference Rapley and Silverman2016). It was possible to analyse the informants’ considerations in the same municipality across different service areas, across management levels and between heads of allocation units and provision units in municipalities with PPM. Further, it was possible to analyse the informants’ considerations in the same service area across the municipalities.

Results

When the informants talked about and discussed user participation in more general terms they claimed that the services over time had become more oriented towards individuals and that the users had more influence than before. However, more concrete questions about what the users could actually influence in the allocation and provision of the services led to the uncovering of the underlying factors that contribute to framing and limiting user influence. The latitude for opportunities to influence the services within these frames constitutes what I call the scope of possibility for user influence.

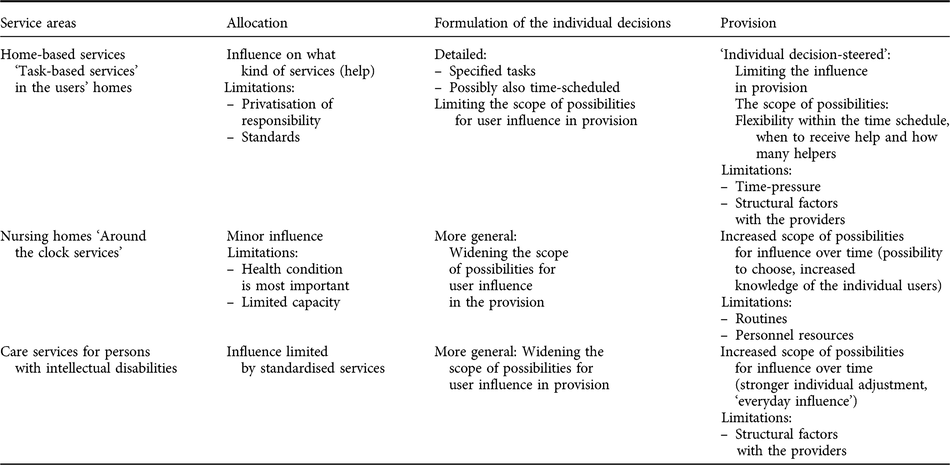

In the analysis of the scope of possibilities for user influence, the distinction between allocation and provision has been of major importance. The output from the allocation stage is an ID that contains information of the kind of and amount of services the individual user is to receive. This ID functions as input in the provision. The analysis has revealed that the actual formulation of the ID is an important structural factor for the possibility for user influence in the provision. Therefore, the service-delivery process comprises three stages: allocation, formulation of the IDs, and provision. Further, the analysis of data has revealed significant similarities within each of the service areas across the municipalities. The differences between the service areas appear as more important than the differences between the municipalities.

In all the municipalities and across service areas, the informants describe a procedure that is more or less standardised for how the first element in allocation of services should take place: ‘The home visit’ with a needs assessment and a dialogue. Therefore, I shall first describe how the municipalities process the applications of services. Each of the service areas structures the rest of this section. Within each of the service areas I analyse the scope of possibilities for user influence (opportunities and limitations) related to the stages of allocation, formulations of the IDs and provision. The findings are summarised in table 2.

Table 2. The scope of possibilities for user influence

Processing of applications of services for new service users

The main routine in the municipalities is to make a home visit to new applicants of care services. In the municipalities with PPM, persons from the allocation unit make home visits. In the two municipalities with traditional organisation, the home visit is also defined as a specialised function by the fact that it is made by a designated professional in each of the service units. During the home visit, there is an assessment of needs, a dialogue about what the user wants and a clarification of the expectations about how the municipal services can contribute. Several of the informants also underline the importance of the dialogue to reveal what the applicants really need because the applications can be insufficiently clear. Often the applicants also lack information about the services the municipality can offer. In the assessment of needs there is also an increasing emphasis put on activating the users and on mobilising their own resources in the service production. The informants argue that this resource-oriented approach is in the users’ own interests.

After the home visit, a decision of what kind and what amount of services should be offered to the user takes place. In the municipalities with PPM, the allocation unit makes this decision, while in municipalities with a traditional organisation, there is often a designated team of managers from one or more of the provision units that fulfils this task. The user/applicant does not participate in the formal process that ends in an ID of the services offered.

Home-based services

According to the informants from home-based care, the user influence on the allocation of services has increased over time, but the influence mostly relates to what kind of help or services one might receive. At the same time, the municipalities have limited the kind of help they offer and have raised the threshold for receiving help. Further, there has also been a standardisation of the amount and frequency of the help that contribute to limiting the scope of possibilities for user influence. It is prescribed how much time it takes to complete different tasks, though there is room for exercising individual discretion and allocating extra time for health-related reasons. However, several of the informants from the providers claim that this is done infrequently. There is also a marked trend towards increasing efficiency in the services. Moreover, there is a stronger emphasis on the users’ responsibility: the home-based services should only be a supplement and they should avoid taking over tasks that the users can do by themselves. They even reduce the number of visits by means of technology like safety alarms. Further, an everyday rehabilitation approach is on the horizon, where the ideal is to educate the users to be self-sufficient.

All the municipalities in the sample have detailed descriptions in the ID of which tasks the home-based services are to carry out, with a variation between municipalities according to whether the time is specified or not. Even if the time is not formulated in the decision, a time schedule is part of the working plans. Most of the informants from the home-based services also claim that the time pressure has increased over time. As a consequence, the flexibility in the provision is limited. The main rule is that these services should only do the tasks formulated in the ID. There may be situations where the user wants help with another task or where the provider sees that there is a need for help for something not mentioned in the ID. The municipalities have an opening for this if the task can be performed within the stipulated time schedule. In many cases, the individual employee will decide this. At the same time, some of the informants stress that this may be problematic because of the loyalty towards the colleagues. It may be regarded as unfavourable if someone has a reputation of being more ‘kind’ than others or doing tasks that no one else does, or if someone manages to do a lot more than others within the same time schedule. Further, the time pressure will imply that a task specified in the ID has to be left out if another task is done instead. When permanent changes in needs occur, one may have a re-evaluation of the ID.

Some aspects of the service provision are not regulated in the IDs and the providers in consultation with the users may decide on them. The informants emphasise that users want to influence when during the day they receive the help. The users who receive help in the morning, for instance, want it before 9:00. For the home nurses this creates problems of priority. They manage this by putting professional considerations first, like prioritising users who cannot get out of bed by themselves, who cannot make breakfast by themselves and who do not have someone in the house to help. According to the informants, some of the users want as few helpers as possible to relate to. The municipalities try different measures to meet this request, but several aspects of the service apparatus make this difficult, for example, sick leave and vacation, which creates the need for temporary workers, as well as rota systems, working hours and many part-time workers.

Nursing homes

The informants fully agree that it is more difficult to get a place in a nursing home than before and that the users are much sicker now. The priorities for admission are based on an assessment of needs particularly related to health condition. Another aspect being mentioned is when relatives are exhausted and the home-based services do not give sufficient help to compensate for this. However, the expansion of the home-nursing services has resulted in more people living in their homes longer than before. This has led to increased user influence in choosing to live at home, and, according to the informants, this is what most of the users want. This also fits well with the municipalities’ policy of expanding the home-based care because it is cheaper than institutional care.

When long-term care in nursing homes is granted, the IDs are formulated in general terms, but the everyday life at the nursing home is relatively standardised, steered by routines because it is an institution that the individual has to adjust to. Still, the informants agree that there are more individual adjustments and greater possibilities for user influence in the nursing homes now than before. This has happened without any increase in the resources because they have differentiated the help. Consequently, they have saved resources and in some of the nursing homes they have tried to use these resources on more activities for the users. The following are examples of user influence being mentioned: selecting the times for getting out of bed in the morning and going to bed in the evening, opting to eat meals in their own room or together with others, deciding how often and when they want to shower, and choosing if they want to participate in activities or not. According to the informants, the nursing homes systematically collect background information about the users. The intention is to try to fulfil individual wishes and needs. The daily routines of institutional life and the time pressure resulting from limited personnel resources, however, still restrict the opportunities of influence. They are thus dependent on relatives, volunteers and other actors to accomplish individualised activities.

Care services for persons with intellectual disabilities

The care services for adult persons with intellectual disabilities in need of comprehensive care, is relatively standardised with shared houses with common areas, or flats without common areas but with a connected base for the care workers. When the municipalities offer these types of standardised services, there are fewer possibilities for persons with intellectual disabilities to choose where they want to live, what kind of work-related activities they prefer, the leisure activities they want to take part in and so on. Users in need of comprehensive care have to apply for a flat in municipally owned housing belonging to the care services. In some municipalities there are shortages of flats, resulting in applicants being put on a waiting list.

The IDs of the services offered by the municipalities to persons with intellectual disabilities are relatively general. The tasks are not time-scheduled, but the number of hours per week may be specified. Several of the informants say that this specified number of hours per week is not followed consistently and that general formulations of the IDs increase the opportunity to use the personnel resources more flexibly between users depending on changing needs and wants from day to day. The practice of not writing detailed IDs gives a scope of possibilities and discretion in the provision of the services.

Some informants describe some form of standardised everyday living for the persons living in these flats. Nevertheless, the informants agree that the service provision was more standardised before and that the users have more influence now. Individual concerns have greater focus than before and there is more freedom of choice in the everyday activities. This also creates for the care workers some challenges relating to diet, cleaning and keeping order in the flat and personal hygiene. The staff tries to supervise and motivate the users in these matters.

Discussion

I shall here summarise the factors that contribute to limiting the scope of possibility for user influence in the different service areas and in the stages of the service-delivery process, and discuss the findings in light of the differing user typologies.

In the allocation stage of the service-delivery process the home visit is a forum for user participation in the allocation of services and can be characterised as a structured dialogue between the professionals and the applicant of services. This procedure makes it possible to obtain a stronger individual adjustment of services. At the same time there is an increasing emphasis put on a resource-oriented approach. Public help is to be a supplement to the users’ own activity and the focus is on help to self-help. The informants legitimise this approach in a paternalistic way by arguing that this activation is for the users’ own good. This corresponds with what Newman and Vidler (Reference Newman and Vidler2006: 199) stress: ‘the involvement of the patient in their own treatment and care is likely to produce improved health outcomes’.

This approach can be interpreted in a co-production perspective, which involves the understanding of the user as co-producer and ‘the value of collaboration’ (Needham and Carr, Reference Needham and Carr2009: 2). Dialogue and clarification of both expectations and what the user can do her- or himself will be of importance in allocating services. Whitaker (Reference Whitaker1980: 244) describes this as ‘mutual adjustment’, where professionals and users ‘interact to establish a common understanding of the citizen’s problem and what each of them can do to help deal with it’. Mutual adjustment occurs when the actions determined from the professional and user are based on their common understanding of the problem. However, the expectation from the service apparatus regarding the user’s own efforts challenges the influence for users wanting to have a passive role as mere receivers of services. Therefore, we may claim that this is an underlying expectation that limits the scope of possibilities for user influence. Even though there is no obligation of activity in these services we cannot rule out that it may be manipulation or a sort of forced responsibilisation if the users feel that they have to accept the solutions the representatives from the service apparatus recommend (Dent and Pahor, Reference Dent and Pahor2015).

If we consider the other structural factors of importance in the different service areas, the study indicates three factors that impose limitations on the scope of possibilities for user influence in the allocation of services.

First, there is the privatisation of responsibility in the home-based services. Tasks that the municipal services performed previously are eventually handed over to other actors to do (Vabø and Szebehely, Reference Vabø, Szebehely, Anttonen, Häikiö and Stefánsson2012). Thus, the scope of possibilities for user influence on what one may receive help from the municipal services has been limited over time. This development can also be interpreted as a forced responsibilisation through absence of essential services (Fotaki, Reference Fotaki2011; Dent and Pahor, Reference Dent and Pahor2015).

Secondly, the service structure imposes limitations. The standardised set of choices for persons with intellectual disabilities is an important factor limiting the scope of possibilities for influence. If they are in need of comprehensive help, they have limited opportunities to choose where to live and what kind of services they will receive. The findings accord with the conclusion in an Official Norwegian Report about the rights for persons with intellectual disabilities. The report states that there are indications that the health and care services for persons with intellectual disabilities are to a certain degree designed and offered as a standardised package, where the service users’ individual needs are to a lesser degree taken into consideration (NOU 2016: 17). Another aspect of this factor is how different interdependent services are dimensioned, especially how the home-based services and the institutional care are dimensionally related to each other. The user influence for receiving a place in nursing home is limited. This accords with findings on a national basis showing that the threshold for receiving a place in a nursing home is higher and that the recipients in nursing homes are sicker and more in need of care than before (Borgan, Reference Borgan2013). Over time we may claim that the lack of capacity in institutions increases the scope of possibilities for user influence to choose to live at home, while it reduces the possibilities to choose to have a place in nursing homes. Consequently, living at home as long as possible may be a forced choice (Christensen and Pilling, Reference Christensen and Pilling2019).

Thirdly, the increasing tendency towards standardisation in the home-based services that limits the user influence on the amount of help and the time spent. Standardisations may limit the possibilities for individual adjustments if they are practised rigidly (Vabø and Szebehely, Reference Vabø, Szebehely, Anttonen, Häikiö and Stefánsson2012). The Norwegian Directorate of Health is also concerned about the tension between standardisations and individual adjustments. They state that different types of standardisation of the allocation of services and the amount of services may be in conflict with the right to individual assessment and individual adjusted services, and with the individual right to participate in designing the services offered (Helsedirektoratet, 2016).

The study has also put emphasis on the importance of how IDs of services are formulated. Formulations that are more general will be less restrictive about the provision of services than detailed formulations, thereby widening the scope of possibilities for user influence. Detailed IDs give little room for user influence in the provision of services. In such cases, the possibilities of user influence is connected to the allocation stage.

An argument in favour of detailed IDs is that it gives more predictability and transparency for the users. Another is that they actually receive the services they have been offered in the ID, thereby preventing the providers from reallocating the resources to other users. In a customer perspective one may emphasise that there are conflicting interests between the professional and the users and that the professionals will be concerned about taking care of their own interests. Thus, the professional providers’ exercise of discretion has to be reduced and a way of doing that is to formulate detailed IDs. The home-based services may be characterised as ‘individual decision-steered’ services with detailed IDs. The scope of possibilities for user influence in the provision may to a certain extent lie in the flexibility to do tasks not mentioned in the IDs, but within the stipulated time schedule. Increasing time pressure limits the possibilities, and collegial norms among the employees may also limit the opportunities. Such collegial norms may be interpreted as a coping mechanism the practitioners have developed in order to manage the unwieldy demands of their jobs (Brodkin, Reference Brodkin and Hasenfeld2010). The providers can decide in matters not regulated in the IDs (with possibilities for the user to influence). Yet still, different structural factors in the service provision will put limitations on user influence, combined with the fact that professional considerations decide the priorities.

In the two other service areas the IDs are formulated more generally. This increases the scope of possibilities for user influence in the provision of services because the provision is steered by the ID to a lesser degree. An important argument in favour of more general IDs is that this facilitates more flexibility in the provision of services. A co-production perspective emphasises that the user and the professional may adjust the services to changing needs and wants (Needham and Carr, Reference Needham and Carr2009). However, this also requires the users to have actual opportunities to influence the services. In the care services for persons with intellectual disabilities, the informants claim that they have moved from standardised practices into a kind of ‘everyday influence’. In the nursing homes, the informants also emphasise that individual adjustment has increased through a stronger differentiation of services. Further, there are increased possibilities for influence by providing more choices and by collecting more knowledge about the individual user; the personnel can fulfil individual preferences to a larger extent. However, the study has revealed several factors that limit the scope of possibilities for user influence in the service provision. In the care for persons with intellectual disabilities, structural frames, like the rota system, may limit user influence. There may also be variations between different kinds of ‘flats’, because some of them may have a more institutional-like culture and are more steered by routines than others (Christensen and Nilssen, Reference Christensen and Nilssen2006). Nursing homes are ‘routine-steered’ institutions, which limits the scope of possibilities for user influence. Shortage of personnel resources limits the possibilities for individual adjustments (Ingstad, Reference Ingstad2010).

In summary, the analysis of the data has revealed elements from different user typologies. This is in accordance with the literature that emphasises that organisations can have several different and even contradictionary institutional logics that give them a hybrid character (Andreassen, Reference Andreassen2018). Fotaki (Reference Fotaki2011: 950) concludes that the user typologies should not ‘be seen as distinct categories but rather as positions on a continuum, or as mutually interchanging entities co-existing alongside each other’. Askheim et al. (Reference Askheim, Christensen, Fluge and Guldvik2017) argue that different approaches to user participation compete for hegemony over time. Christensen and Pilling (Reference Christensen and Pilling2019) point to various discourses and emphasise the need to examine all nuances in critical analyses.

I argue that the perspective of the user as customer is of minor importance in the municipalities in this study. In one of the municipalities, the users of home-based services can choose between the public and a few private providers, but in the others the public provider is the only one. With respect to the services on offer, the users can exert their influence through the dialogue in the home visit. This is a consulting role where the representatives from the service apparatus can promise to consider their views. The users do not participate in the final decision about the allocation of services. Therefore, in this context user influence in a more restricted sense describes the situation more accurately than ‘choice’. The users may present their wants and argue for these, but the service apparatus makes the formal decision. Detailed IDs in the home-based services may be interpreted as an element of a customer perspective. There are also elements of choice with the increased possibility to stay at home as long as possible with home-based services, and in the nursing homes and care for the intellectual disabled in concrete everyday activities. Nevertheless, the elements of choice are so marginal that we may conclude that the idea of the consumer provided some measure of inspiration, but the service user as a customer has not been realised at all.

There are elements of understanding the user as co-producer through the dialogue and the increasing importance of activation of the users in their own service production. This has also contributed to increased efficiency because the differentiation of help may be efficient, more economical and more accurate. In this context, the managers will argue that user involvement may be interpreted as a ‘win-win situation’ for both the users and the service apparatus (Askheim et al., Reference Askheim, Christensen, Fluge and Guldvik2017: 15). The intention of the generally formulated IDs is also to give the opportunity to maintain flexibility in the provision of services through a dialogue between the users and care workers.

Nevertheless, I argue that the most dominant understanding of the users is as clients with the possibility to influence on the service delivery through voice. The standards, the paternalistic approach to responsibility as ‘good for you’, the coping strategies of the care workers and the stress on professional priorities all point in that direction. This even includes the general IDs if the actual impact is that the professionals are given more power.

Conclusion

This study has analysed user influence as an important aspect of individual adjustment of services in the municipal care sector. The empirical basis for the study has been interviews with managers at different levels and service areas in five Norwegian municipalities. When the managers speak in general terms, they claim the services have been more individualised and user influence has increased over time. However, a critical analysis of the actual stages and elements in the service-delivery process has revealed structural factors that contribute to a limitation of the individual adjustment of services. Established structures and frameworks determine users’ opportunities to influence the service-delivery process, which I denote as the scope of possibilities for user influence. The most important restrictive factors are the existing set of choices of municipal services, the service structure, how the individual decisions are formulated, the standardisation of services, the increasing time pressure as well as the work routines and patterns of practice and the care workers’ norms. In the short run, these elements will appear as stable, even though there might be room for actors to challenge the frames or to exercise discretion within the frames. In the long run, changes of the structures will be possible if municipal politicians have the will to change them.

This article also contributes to a further understanding of the relationship between the different typologies of the service users and the structural features. Even though we find elements from different user typologies, the conclusion is that the understanding of the user as a client is dominant. There seems to be a growing understanding of the user as co-producer, while the customer perspective is of marginal importance. These findings indicate that the Norwegian welfare system differ from the development of marketisation which has been the case in many other European countries.

Acknowledgements

This article is based on a study called ‘Making user participation work – from policy to practice’, funded by the Norwegian Research Council. I want to thank colleagues and co-researchers for their useful input, especially Ole Petter Askheim for his comments on earlier drafts of this article. The reviewers of the journal have also made insightful comments that have helped me to clarify and improve the article.