How do social movement organizations involved in abortion debates leverage a global crisis to pursue their goals? On April 8, 2020, the anti-abortion organization Campaign Life Coalition in Canada tweeted from their official Twitter account, “Playing politics during pandemic: It is sheer hypocrisy to assert that non-essential medical services must be suspended while, at the same time, allowing for #abortion on demand. Please contact your Premier. http://ow.ly/fe3f50z8N1t#AbortionIsNotHealthCare#AbortionIsNotEssential” (Campaign Life Coalition 2020). The link in this message takes the reader to the Campaign Life Coalition’s website and information on how to contact one’s Premier. The message is a call to action to demand that abortion services cease in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis and it argues that politicians in Canada are taking advantage of the crisis to provide abortion services, though abortion is already legal in Canada. The pandemic pushed the categorization of “essential” versus “non-essential” healthcare services into the limelight during the early days of the lockdowns that followed in its wake, and the mobilizing message (Snow et al. Reference Snow, Rochford, Worden and Benford1986) regarding politicians “playing politics” and demanding that abortion procedures cease fits with theories of “crisis exploitation” (Boin, ’t Hart, and McConnell Reference Boin, ’t Hart and McConnell2009) and how crisis can be used by political actors to mobilize support and push for change. Bringing together Crisis Exploitation Theory from the study of policy and communication and the concept of discursive opportunity structure from social movement theory, I ask to what extent and how social movement organizations (SMOs) working on the issue of abortion in several countries “exploited” the 2020 COVID-19 crisis.

The tweet from Campaign Life Coalition encouraging followers to contact their Premier reveals the way SMOs may view a crisis as an opportunity, or a critical discourse moment, that they can “grab” (Sawyers and Meyer Reference Sawyers and Meyer1999). While catchy newspaper headlines such as “How Abortion, Guns, and Church Closings Made Coronavirus a Culture War” (Peters Reference Peters2020) were featured in the media to point to how the abortion debate was “reignited” in the United States at the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, less attention was given to whether abortion was being framed in relation to the COVID-19 crisis in other countries. Did movements across countries impacted by the pandemic attempt to “exploit” the crisis? Are some types of social movement actors more likely to view the crisis as an opportunity than others? We know from the literature that political actors “scan their horizons for ‘problems’ in order to promote their own preferred ‘solutions,’ and may seek to appropriate critical incidents of various kinds for precisely that purpose” (Boin, ’t Hart, and McConnell Reference Boin, ’t Hart and McConnell2009, 83; Kingdon Reference Kingdon2010). In the case of major crisis such as the worldwide spread of COVID-19, this scanning may not be very involved, as the crisis dominated news cycles and policy agendas. Early studies on the impact of the COVID-19 crisis suggest that social justice activists were particularly active during the first months of the crisis and competed to “impose different narratives of the crisis and of the world that should come out of it” (Pleyers Reference Pleyers2020, 3). But do all SMOs respond similarly, and, if they incorporate crisis into their rhetoric, to what extent and in what ways do they do this? Turning to SMO activity on Twitter as a key location for discursive strategy and political debate in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, this study explores how crisis is exploited by SMOs involved in abortion debates.

Crisis Exploitation

Boin, ’t Hart, and McConnell (Reference Boin, ’t Hart and McConnell2009) propose a theory of crisis exploitation to explain how, through strategic framing contests over crisis situations, political leaders may capitalize on crises to boost their image or push through their preferred policy solutions. Their definition of “crisis exploitation” is “the purposeful utilization of crisis-type rhetoric to significantly alter levels of political support for public office-holders and public policies” (Boin, ’t Hart, and McConnell Reference Boin, ’t Hart and McConnell2009, 83; emphasis original). They propose their theory of crisis exploitation to explain the differences in policy and political outcomes across various countries and crisis scenarios. While “exploitation” has negative connotations, this process is a strategic political move for political elites, whose positions may be threatened by the crisis otherwise due to framing contests that take place with opponents or other political actors in the process of interpreting the crisis, its implications, and who is to blame.

Crises are recognized as possible focusing events (Birkland Reference Birkland1997, Reference Birkland1998, Reference Birkland2006) with agenda-setting potential if responded to strategically, and scholarship on “blame management” in crisis situations further delves into the exploration of how crises can be interpreted and framed (Hood et al. Reference Hood, Jennings, Hogwood and Beeston2007). Elites can exploit crises, but their images can also be damaged by crisis if oppositional politicians and groups are successful in placing blame on them (’t Hart Reference ’t Hart1993; ’t Hart and Tindall Reference ’t Hart, Tindall, Kane, Patapan and ’t Hart2009; Keeler Reference Keeler1993; Klein Reference Klein2010; Tarrow Reference Tarrow1998). Despite the risk, studies of crisis communication suggest that crises often lead to framing competitions among elites (Birkland Reference Birkland2006; Hodder and Martin Reference Hodder and Martin2009; Iyengar and Simon Reference Iyengar and Simon1993; Keeler Reference Keeler1993; Kuipers Reference Kuipers2005; Nord and Olsson Reference Nord and Olsson2013; Sood, Stockdale, and Rogers Reference Sood, Stockdale and Rogers1987). Other actors are involved in these framing competitions, such as journalists who grant or deny desired news media attention to concerned actors and may also participate in framing the crisis (Olsson and Nord Reference Olsson and Nord2015; Tian and Stewart Reference Tian and Stewart2005). While social movement actors are frequently alluded to as the “opponents” of political elites who may seek to use the crisis to create change and vie for media and public attention, studies of the way in which these actors engage with crisis are lacking.

Extant research on focusing events is helpful in looking at crisis or other unexpected and high-impact events that can help groups mobilize and engage in issue-expansion. According to this literature, these attempts can be quite successful because greater attention to a problem may lead to more negative views of policy handling the problem (Baumgartner and Jones Reference Baumgartner and Jones1993; Birkland Reference Birkland1998, 55). Studies on focusing events emphasize the role of pro-change groups in mobilizing around such events and exploiting the event in ways similar to how elites in the studies of crisis exploitation are seen doing (Birkland Reference Birkland1998; Boin, ’t Hart, and McConnell Reference Boin, ’t Hart and McConnell2009). It makes sense that a focusing event, which is defined by Birkland as a sudden, uncommon event that can be seen as harmful to at least some groups or geographic areas and becomes known to the public and policy makers simultaneously (Birkland Reference Birkland1998, 54), could spur action on the part of interested advocacy organizations and interest groups. To illustrate, Birkland uses the example of the Exxon Valdez oil spill and how environmental groups were able to create a causal narrative of the event as resulting from problems in policy that required a mobilized response to demand change from the government (Birkland Reference Birkland1998, 57). In this way, they exploited an existing crisis to propose change.

The COVID-19 crisis is, of course, a different type of focusing event than an oil spill or, in the case of abortion, an event such as a woman’s death from unsafe abortion. There are more steps in the causal story linking COVID-19 to abortion politics compared to the steps needed to link the Exxon Valdez oil spill to environmental issues or a woman’s death due to unsafe abortion to restrictions on abortion access. Yet the COVID-19 crisis dominated the political, media, and public agendas—especially in the early months of the pandemic. Therefore, SMOs involved in abortion politics may have engaged in exploitation of the crisis. SMOs can be creative in their causal narratives in order to remain relevant in the face of “media storms” (Boydstun, Hardy, and Walgrave Reference Boydstun, Hardy and Walgrave2014; Gruszczynski Reference Gruszczynski2020) concerning news items that are not directly linked to their cause, and this is worth exploring.

At the same time, Boin, ’t Hart, and McConnell (Reference Boin, ’t Hart and McConnell2009) point out that political elites, or in the case of the Exxon Valdez oil spill, the companies and their political allies, may downplay the crisis or even ignore it in order to avoid negative consequences and blame, though Birkland suggests that how they respond may be influenced by other characteristics of the policy environment (Birkland Reference Birkland1997). When it comes to social movements, Rohlinger (Reference Rohlinger2014) suggests that there are times when SMOs may similarly practice “strategic silence” in the wake of high-profile events that make attention risky. For example, anti-abortion organizations in the United States were sometimes silent after shootings occurred at abortion clinics because any attempt to frame the event risked being associated with it. As such, when focusing events and crises occur, it may be the case that organizations prefer “strategic silences” when such events are challenging to frame in relation to their goals or could derail organizations’ long-term work and efforts. Yet we know little about whether and how these organizations respond to crisis and whether their responses are similar to those of elites.

Scholars have noted that incremental change is the hallmark of stable policy environments and such incremental change is accompanied by fairly consistent framing of issues because the powerful players have a monopoly over the policy arena and control the boundaries of debate (Baumgartner and Jones Reference Baumgartner and Jones2009; Kingdon Reference Kingdon2010). However, focusing events, including crises, may upset stability in policy environments and lead to opportunities for new frames to gain traction—and, indeed, may demand that new frames be used to discuss the crisis/issue by actors who want to maintain their positions (Birkland Reference Birkland1997). These focusing events and the framing competitions they prompt may lead to multiple and divergent frames and are not necessarily conducive to frames that provide the best actionable solutions, as studies on the impact of the Columbine school shooting show (Birkland and Lawrence Reference Birkland and Lawrence2009; Lawrence and Birkland Reference Lawrence and Birkland2004). But movements have a variety of incentives to exploit crisis, and indeed they may even construct crisis. When it comes to exploiting an existing crisis such as COVID-19, movements can place blame or criticize the handling of the crisis by elites who oppose them, heighten public attention to their cause by linking their issue to the attention-generating crisis, and place pressure on reluctant political allies to propose certain solutions to the crisis. For example, activists in some countries were able to use the COVID-19 crisis to bring attention to the burden of travelling for an abortion and the need for telemedicine by linking these to concerns about public health and travel restrictions in the wake of the virus in ways that previously were not possible.

The COVID-19 crisis has features that are relatively unique because it had worldwide impact, was responded to by governments in unprecedented ways, and was politicized, especially in certain countries, early on. But these features also make it an excellent crisis to study across countries in order to compare how organizations concerned with a specific issue handled the same crisis in different contexts. The virus dominated public, political, and media agendas across countries, and this makes it a unique opportunity to observe how movements responded. Social movement organizations frequently compete with one another to frame events, opening opportunities for vilification of their opponents and frame debunking (McCaffrey and Keys Reference McCaffrey and Keys2000; Rohlinger Reference Rohlinger2002). How do social movement organizations respond to crisis? To what extent did social movements working for and against abortion in their respective countries adjust their discursive strategies to respond to the COVID-19 crisis as it swept across the globe? The destabilizing effect of crisis can be framed as both a threat and an opportunity by SMOs, as will be shown.

Crisis Exploitation and Social Movement Discursive Opportunity Structure

Present but not accounted for in the elite-focused crisis exploitation theory are other interested parties such as social movements. Tarrow defines a social movement as “collective challenges, based on common purposes and social solidarities, in sustained interaction with elites, opponents, and authorities” (Tarrow Reference Tarrow1998, 3–4; emphasis original). These challenges may be sparked and led by social movement organizations that form in order to centralize collective action and these SMOs constantly scan the horizon looking for opportunities to have their voices heard.

Discursive opportunity structures, which provide a framework through which to identify successful framing strategies and reveal that “cultural elements in the broader environment facilitate and constrain successful social movement framing” (H. McCammon Reference McCammon2013), contribute to this discussion. The surrounding discursive opportunity structure may explain the way in which actors craft their frames to respond to their political environments (Koopmans and Olzak Reference Koopmans and Olzak2004). Studies of the discursive opportunity structure focus on the language social movements use to interpret that political environment and help explain the success or failure in the diffusion of some frames compared to others.

A frame is a “central organizing idea, suggesting what is at issue … frames are expressed over time as a story line” (Gamson and Wolfsfeld Reference Gamson and Wolfsfeld1993, 118). At the same time, Snow et al. (Reference Snow, Rochford, Worden and Benford1986, 476) point out that frames are “temporally variable and subject to reassessment and renegotiation.” McCammon (Reference McCammon2012) identifies a process of strategic adaptation wherein collective actors deploy frames (or other collective action strategies), assess their performance, and adjust them or change them if deemed necessary given their reception by target audiences. Not all organizations and actors abide by this process for myriad reasons—internal disagreements, lack of resources, and more; but McCammon argues that activists are more successful when they adapt strategically. Given the previous research on discursive opportunity structure and crisis exploitation, it follows that social movement organizations seeking to further their goals and heighten attention to their issues may view crisis and its disruption of the status quo as an opportunity to expand the realm of debate with language that frames their issue of concern in relation to the crisis.

Crisis Exploitation in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Expectations

The social movement theories and concepts described earlier are typically applied in times of relative normality. Combining the concepts of discursive opportunity structures and framing with the theory of crisis exploitation, the study explores the ways in which social movement organizations in four countries responded to the COVID-19 pandemic and whether they incorporated the pandemic into their narratives (Gamson and Wolfsfeld Reference Gamson and Wolfsfeld1993).

There are two core expectations that come from social movement and crisis exploitation theories. Because both suggest that actors who are seeking change will be proactive in seizing opportunities (Birkland Reference Birkland1998; Boin, ’t Hart, and McConnell Reference Boin, ’t Hart and McConnell2009; Gamson and Meyer Reference Gamson, Meyer, McAdam, McCarthy and Zald1996), the first expectation is that the “side” in the abortion debate that is fighting for significant change in the status of abortion will be more likely to see the crisis as a discursive opportunity that may be exploited to insert their arguments onto the agenda and will do this proactively (measured here as early incorporation of the crisis and references to the crisis in a high proportion of their tweets). The second expectation is based in what we know about movement-countermovement dynamics and suggests that framing competitions with opponents will lead to all movement organizations adjusting their language to some degree if their opponents are exploiting the crisis (Andrews Reference Andrews2002; Ayoub and Chetaille Reference Ayoub and Chetaille2020; Dorf and Tarrow Reference Dorf and Tarrow2014; McCaffrey and Keys Reference McCaffrey and Keys2000; Meyer and Staggenborg Reference Meyer and Staggenborg1996; Rohlinger Reference Rohlinger2002). Systematically observing whether the crisis is exploited across all of the countries under study is a key empirical contribution of this study.

These expectations are gleaned from the literature and tell us about the timing and extent of SMO responses to the COVID-19 crisis. A qualitative thematic analysis of the content of SMO’s tweets allows us to study organizations’ rhetorical responses to the crisis. Boin, ’t Hart, and McConnell (Reference Boin, ’t Hart and McConnell2009, 84) argue that, confronted with the same crisis, actors may adopt “fundamentally different postures” in framing contests. They may frame the crisis as an “unfortunate incident” that has nothing to do with them, denying that the incident is, indeed, a crisis or one that should have political impact. They may deem the crisis as a “critical threat to the collective good embodied in the status quo” (emphasis original) and will therefore defend the status quo against change, or they may deem events as a “critical opportunity” to expose problems with the status quo and push for their proposed solutions, which may include placing blame on those in charge and calling for their removal (Boin, ’t Hart, and McConnell Reference Boin, ’t Hart and McConnell2009, 84). When applied to social movements, these same types of responses can be seen as relevant possibilities. These three categories (ignoring/downplaying crisis, crisis as critical threat, and crisis as critical opportunity) are used to code and analyze the dominant crisis rhetoric (or lack of it) seen in SMO tweets.

Cases

Four countries are included in the study: The United States, Canada, the Republic of Ireland, and Northern Ireland. In each country, there are organizations dedicated to pro- and anti-abortion positions with various domestically situated goals related to these positions. The organizations included in the analysis from each country are listed in table 1. Due to space constraints, a few basic details about each country’s abortion laws and debate are provided here, bearing in mind that the situations in each country are complex.

Table 1 Details of organizations included in analysis

In Northern Ireland, the situation is especially complicated due to devolution. The most relevant information for the purpose of this analysis is that abortion was decriminalized on October 21, 2019 by Westminster, and Northern Ireland’s Department of Health was instructed to put the legislation into force by April 2020 (Yeginsu Reference Yeginsu2020); however, by March 2020 and the arrival of COVID-19, the government had not moved toward introducing abortion services in the country. Therefore, the pro-abortion rights organization is considered the movement for change, and as of August 2020 this SMO was still fighting for the implementation of abortion services. Across the border in the Republic of Ireland, a public referendum creating a mandate for liberalizing abortion laws was passed by a 66.4% majority in 2018. By January 2019 legislation was implemented, moving the country from only allowing abortion when a woman’s life was in danger to allowing abortion for any reason up to twelve weeks (O’Loughlin Reference O’Loughlin2018). For these reasons, the anti-abortion organization is considered the organization for change although this is a recent shift.

On the other side of the Atlantic, in the United States, the 1973 Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision limited the ability of states to restrict abortion access. However, contention over abortion is high and pro-abortion rights organizations are constantly battling threats to abortion rights at state and federal levels. Given the anti-abortion stance of the governing Trump administration during the time period under study and the recent appointment of three conservative judges to the Supreme Court, the abortion debate is active at the federal level and, as other scholars point out, the outcomes of many Supreme Court cases have been mixed with no absolute winners or losers (Munson Reference Munson2018).

Across states, there is great variation in abortion laws and access. Given this variation, national- and state-level organizations are included in the analysis. States with highly restrictive abortion laws (Missouri, Ohio, Texas) are included in the analysis along with two states (California and Massachusetts) where abortion laws are more liberal. Because of the precarious position of abortion access in early 2020, the anti-abortion policy stance of the executive branch, and the pro-abortion rights movement’s early success being the inspiration for the anti-abortion counter-movement, the pro-abortion rights organizations are considered most representative of the movement for change. However, due to the complexity of the policy environment, both sides could be considered movements for change; this, and the usefulness of applying these categories (“movements for change” and “movements against change”) to abortion SMOs in general, or during crisis specifically, is discussed in the results.

In Canada, contention over the status of abortion has remained relatively low since 1988 when the Supreme Court struck down Canada’s abortion law, though provincial-level healthcare policies vary and lead to variation in access to abortion services. There have been recent attempts to propose bills to restrict abortion in cases such as sex-selective abortion (Parliament of Canada 2020) and anti-abortion advocates have also changed their rhetoric to reflect more “pro-woman” arguments and appeal to younger audiences (Saurette and Gordon Reference Saurette and Gordon2016). Pro-abortion rights organizations have focused on expanding abortion access to rural areas and minority populations. In Canada, several organizations are included here to represent the variation in approaches to the abortion debate that has been the subject of scholarly attention in recent years (Halfmann Reference Halfmann2011; Saurette and Gordon Reference Saurette and Gordon2013, Reference Saurette and Gordon2016; Shaw and Norman Reference Shaw and Norman2020) and the anti-abortion organizations represent the movement for change.

Data and Methods

These cases include two countries where abortion is legal and the anti-abortion organizations could be considered the movements for change, and two countries where abortion is highly contested in vitriolic political and legal struggles and where the pro-abortion organizations may be considered representative of the movement for change. In all four countries, the COVID-19 virus dominated the agendas of the news media, politics, and public beginning around or shortly after March 1, 2020.

To test whether social movement organizations “exploited” the COVID-19 crisis as a discursive opportunity and how they did this, I conduct an analysis of the Twitter activities of the several organizations involved in the abortion debates in each country. Twitter is a platform many organizations use to communicate to audiences and to aid in efforts to attract news media attention and the attention of political elites and allies (Austin and Jin Reference Austin and Jin2017; Bennett and Segerberg Reference Bennett and Segerberg2011, Reference Bennett and Segerberg2012; Conway, Kenski, and Wang Reference Conway, Kenski and Wang2015; Feezell Reference Feezell2018; Freelon and Karpf Reference Freelon and Karpf2015; Graham, Jackson, and Broersma Reference Graham, Jackson and Broersma2016; Hunt Reference Hunt2019; Hunt and Gruszczynski Reference Hunt and Gruszczynski2019; Stier, Schünemann, and Steiger Reference Stier, Schünemann and Steiger2018). Given that the COVID-19 crisis led to lockdowns and bans on normal social movement operations, their activities online and their discursive strategies to frame the crisis and maintain the organization despite not having access to other mobilization tools become particularly important to study. Table 1 provides details of the organizations included in the study across the four countries.

I retrieved the tweets of the organizations in table 1 using the rtweet package in R (Kearney Reference Kearney2017). The most recent 3,200 tweets were pulled from each individual account (which is all that is allowed through the Twitter API) on August 17, 2020. After filtering out Retweets—which may or may not be representative of an organization’s discursive strategy—and tweets prior to January 1, 2020, or after August 1 from the tweets of each organization, the resulting dataset includes a total of 12,051 tweets across the organization accounts in the eight-month period. The time period between January 1 and August 1 is deemed sufficient to capture any crisis-inspired responses among the organizations and to detect how long shifts in rhetoric last. After collecting all of the tweets, the organizations were coded into “Anti-Abortion Rights” or “Pro-Abortion Rights” groups by country. The organizations within the United States were also grouped by “state-level” and “national-level.” This is more manageable than looking at each of the organizations individually and, by using proportions in the descriptive data, the difference in number of tweets is accounted for and the competitions between the sides in the abortion debate can be compared more easily.

Patterns in how frequently organizations tweet before and after the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis show whether organizations became more or less active on Twitter as a result of the crisis. Pleyers (Reference Pleyers2020, 2) suggests that social justice movements have been particularly active during the pandemic both on and offline and observing tweeting patterns among SMOs helps establish whether these organizations ramped up their online activity or incorporated the crisis into their normal tweeting activities as they would other major events.

Additionally, I conduct a term search within the collected tweets for the terms “covid,” “corona,” “pandemic,” “lockdown,” or “virus” and pulled those tweets after March 1, 2020, that included any of these terms. I then hand-coded all tweets that were not included in the term search to determine whether they were tweets about the COVID-19 crisis or not. In most cases, the search terms were able to pick up COVID-19-related tweets but occasionally the hand-coding process revealed tweets that were about the crisis but did not include the search terms, with language such as “During this public health crisis.” These tweets were merged into the dataset of tweets returned by the search terms to create a dataset of COVID-19-related tweets from each organization between March 1 and August 1, 2020.

Finally, I conduct a qualitative thematic analysis (Ahmed et al. Reference Ahmed, Bath, Sbaffi and Demartini2019; Braun and Clarke Reference Braun and Clarke2006) using a mixed-method deductive approach wherein I applied categories derived from the literature to organize and analyze the SMO tweets. Following previous thematic analysis of Twitter content (Ahmed et al. Reference Ahmed, Bath, Sbaffi and Demartini2019), after narrowing down the data by collecting the COVID-19-related tweets from each of the twenty-two organizations, I read and coded these tweets into the three different categories of elite crisis rhetoric responses identified by Boin, ’t Hart, and McConnell (Reference Boin, ’t Hart and McConnell2009): 1) ignoring/downplaying crisis, 2) the crisis as a critical threat, and 3) the crisis as a critical opportunity.Footnote 1 Organizing COVID-19 tweets from the SMOs into these categories revealed similarities in crisis rhetoric across countries while also eliciting the ways SMO responses diverged across countries due to different policy environments. This provides a nuanced analysis of SMO crisis-rhetoric and points to explanations for variation across SMOs.

Results and Discussion

General Tweeting Patterns among SMOs

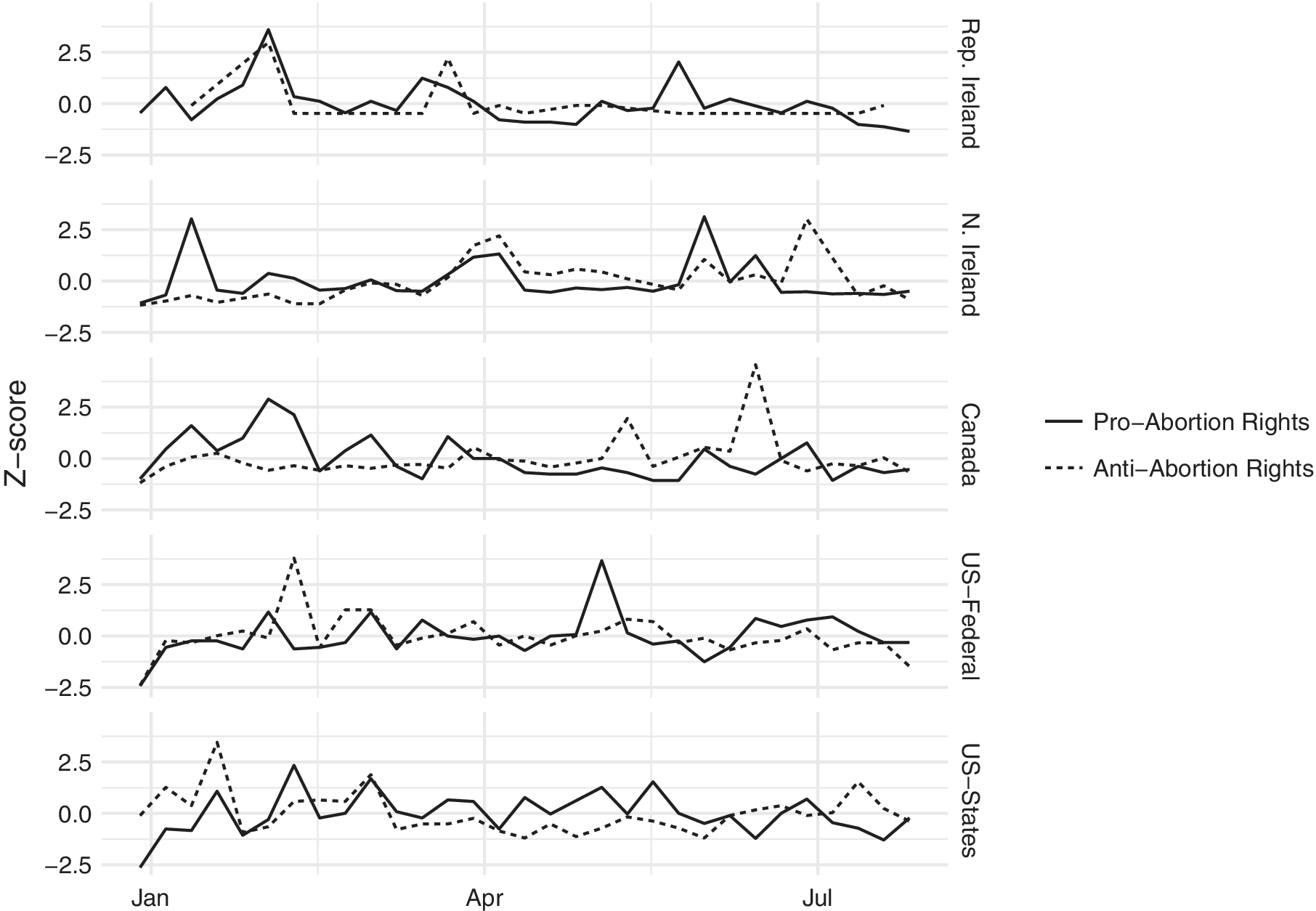

To what extent are organizations’ tweeting habits disrupted by the COVID-19 crisis and the stay-at-home orders initiated in many contexts? Figure 1 shows the number of tweets from anti-abortion rights and pro-abortion rights organizations over time in each country. Because there are different numbers of organizations included in the analysis for each country and all tweet at varying levels, the figure shows the deviation from the average number of tweets across the different organizations to show change in tweeting behavior.

Figure 1 Tweeting deviation from average

The figure illustrates that, in terms of tweeting frequency, organizations tended to respond to the COVID-19 crisis in a similar way to the way they handle other major events, with points of higher activity in response to the beginning of the crisis and other points of higher activity in response to other events.Footnote 2 For example, in mid-March in the Republic of Ireland there is a spike in pro-abortion rights tweets and these tweets featured demands for telemedicine and use of home abortion medicines to ensure access to abortion services in early pregnancy during the COVID-19 crisis (Abortion Rights Campaign 2020). In June, another increase in the average tweets from the organization account was about a vote on abortion regulations in Northern Ireland. While the COVID-19 crisis did increase tweeting among the organizations, it did not do so uniquely compared to other events. The extent to which tweets incorporated the crisis in their content is assessed next.

Adjusting to Crisis: Tweets Related to COVID-19

To begin answering the question of whether organizations adjusted their messages and to assess whether SMO responses align with the expectations of this paper that “pro-change” movements will proactively frame the crisis to further their goals (or, “exploit” it by using crisis-type rhetoric), a dataset of COVID-19-related tweets after March 1, 2020, was created (refer to the explanation in the data and methods section). In table 2 the proportion of tweets after March 1, 2020, that were about the COVID-19 crisis are presented. March 1 was chosen as the date when the COVID-19 pandemic started to become a pressing issue for the countries under study, though the crisis became more immediate about two weeks later when schools started being closed and governments began issuing stay-at-home orders.

Table 2 Proportion of tweets about COVID-19

* Total tweets after March 1, 2020.

** Highest proportion in each country in bold.

Table 2 suggests that the first expectation of this paper, that the movement for change will proactively “exploit” the COVID-19 crisis, does not hold. It appears to be true in most countries, but in Canada the movement for change is the anti-abortion movement and yet the pro-abortion rights organizations tweeted proportionately more about COVID-19 between March 1 and August 1.Footnote 3 This finding points to the possibility that something else was driving the way SMOs responded to the crisis. Being “pro-change” is potentially influential in other decisions SMOs make but it may not be a helpful distinction during times of crisis due to the way the status quo is disrupted or, perhaps, in relation to organizations involved in abortion debates generally, where anti- and pro-abortion actors both seek change in different ways (restricting or expanding abortion rights regardless of the legal status of abortion). The stronger pattern here seems to be ideological, with pro-abortion rights organizations more likely to incorporate the COVID-19 crisis into their messages. The Republic of Ireland is the only country where the anti-abortion organization had a higher proportion of tweets about COVID-19, but they tweeted very little overall (only twenty-five tweets total in the timeframe) and figure 2 reveals that they began tweeting about COVID-19 only after their opponents. This brings us to the second expectation, that organizations will adjust their rhetoric to respond to the crisis when their opponents do, which is discussed in the next section.

Figure 2 COVID-19 tweets

Movement-Countermovement Dynamics and Response Timing

Due to the way COVID-19 was politicized early in many countries by conservative actors with whom anti-abortion organizations tend to align politically, these SMOs may have been reluctant to engage with the crisis initially and found it challenging to frame, leading to “strategic silence” (Rohlinger Reference Rohlinger2014). Pro-abortion rights organizations, observing the way the pandemic exacerbated inequalities and highlighted issues of access for marginalized populations, were quicker to frame the crisis and “the world that should come out of it” (Pleyers Reference Pleyers2020, 3). Figure 2 provides further evidence that this, rather than their status as either the movement for or against change, may have been influential in determining the timing of movements’ responses. As pro-abortion rights organizations in each country scanned the horizon and identified the COVID-19 crisis as something that could impact abortion access, anti-abortion rights organizations saw prominent anti-abortion proponents such as Donald Trump (U.S.), Boris Johnson (UK), and Jair Bolsonaro (Brazil), as well as other politicians, publicly downplaying the seriousness of the threat posed by the virus. Figure 2 shows that across all of the countries under study, the anti-abortion organizations only began tweeting about the COVID-19 crisis after their opponents had already begun framing the crisis, suggesting a reluctance to address the issue until framing competitions were deemed unavoidable.

The finding that pro-abortion organizations were the first to begin adjusting their messages on Twitter is particularly interesting because in the case of the United States, the anti-abortion movement has gotten much media attention for their attempts to restrict abortion access through state governments’ stay-at-home orders that categorized abortion as a “non-essential” procedure (Tavernise Reference Tavernise2020). While their elite allies proactively exploited COVID-19 on the ground, anti-abortion organizations did not engage in “the purposeful utilization of crisis-type rhetoric” (Boin, ’t Hart, and McConnell Reference Boin, ’t Hart and McConnell2009, 83; emphasis original) very much on Twitter. Because their powerful allies were working on exploiting the crisis, these organizations may have deemed it unnecessary to address the crisis initially (Birkland Reference Birkland1997). But most of the organizations across countries did at some point engage in some level of COVID-19-related tweeting and in the United States the anti-abortion organizations were not far behind their opponents in doing this. Three “crisis-type” rhetoric categories that appeared in the tweets of the opposing organizations across different country contexts are identified and analyzed in the following section and shed more light on how organizations responded.

Three Categories of Crisis Rhetoric

Boin, ’t Hart, and McConnell (Reference Boin, ’t Hart and McConnell2009) suggest that political elites will respond to crisis in three possible ways depending on how they perceive the crisis and its potential impact on their image and power. They may ignore or downplay the crisis, view it as a critical threat and purport to defend the status quo from the threat, or view it as a critical opportunity and attempt to use it to propose and push for particular solutions. One of the expectations of this study was that movements for change would be most likely to view crisis as a critical opportunity, but the results of the quantitative analysis bring this into question. For the purposes of further elucidating our understanding of how crisis-type rhetoric manifests in abortion debates during the COVID-19 crisis and why, I analyzed all of the COVID-19-related tweets of the organizations under study and coded them into the three different categories identified by Boin, ’t Hart, and McConnell, regardless of whether or not the organization was working for change. Approaching the analysis in this way reveals that, while only the anti-abortion organizations initially ignored the crisis, all of the organizations across the four countries tweeted messages that constructed the crisis as a threat or an opportunity, though the policy environment they faced shaped these messages.

Ignoring or Downplaying COVID-19

As shown earlier, the anti-abortion organizations in all four countries tended to ignore the crisis at the beginning, which is similar to the response of many prominent anti-abortion elites. Instead, these organizations continued to focus their tweeting on their ongoing campaigns and issues of interest. For example, in Canada, the Conservative Party’s leadership race was of interest to the SMOs because there were several contenders with strong anti-abortion views, and a bill to ban sex-selective abortion—a core issue for anti-abortion organizations who want to see some type of legal restrictions placed on abortion—was introduced to parliament by MP Cathay Wagantall (Levitz Reference Levitz2020; Parliament of Canada 2020). But this did not last long and COVID-19-related content began appearing on anti-abortion rights organizations’ Twitter accounts around mid-March, just after their opponents began tweeting about the crisis.

When these anti-abortion SMOs did tweet about the COVID-19 crisis, their behavior differed from that of their opponents not only because they incorporated the crisis into their tweets less often, but also because they sometimes did so in less substantive ways. For example, the Canadian Centre for Bio-Ethical Reform (CCBR) posted a tweet with a video from one of their members and a quote from the video, “‘If we live in a country where we don’t give the death penalty to a guilty rapist who must be punished, why would we give the death penalty to their innocent child?’ #endthekilling #covid-19 #whywefight.” Neither the content of this tweet nor the video that was attached to it had any relation to COVID-19 other than the fact that it was posted on April 21, 2020, which was during the Canadian lockdown. The organization used the hashtag to identify their activism during the lockdown and to link their message to COVID-19 streams of discussions on Twitter, but this tweet does not substantively frame the crisis or abortion in relation to the crisis.

While the anti-abortion organizations across the four countries tended to engage with the crisis less and this can be seen as a type of “downplaying” its seriousness, there were no tweets that directly addressed the COVID-19 crisis and explicitly suggested that it was not a serious crisis. This is surprising given that these organizations frequently praised conservative political elites for their handling of the crisis even while some of these elites were refusing to implement stay-at-home orders and suggesting that the virus was not serious. Instead, in all four countries, including the United States where organizations routinely praised the Trump administration, they recognized the seriousness of the pandemic when they tweeted about it and their tweets tended to fall into the following two categories along with the tweets of pro-abortion rights organizations.

The COVID-19 Crisis as a Critical Threat

Anti-choice officials are using the #COVID19 crisis as an excuse to ban abortion. And they’re banking on us being too distracted by this pandemic to pay attention. But we’ll never stand idly by while they take away our fundamental reproductive freedom.

—NARAL, April 6, 2020Pro-abortion rights SMOs proactively responded to the crisis relatively early and frequently, including in ways that constructed it as a “critical threat” that required a defense of the status quo. This manifested most frequently in the framing competition over whether or not abortion is an essential procedure that was exempted from stay-at-home orders and business shutdowns. The quoted tweet above from U.S.-based NARAL on April 6 captures the way the virus was frequently deemed a threat to existing reproductive freedoms because politicians were attempting to use the pandemic as a way to restrict abortion access.

The tweets that fall into the category of “threat” appeared across the countries, but they do reveal the ways in which the policy environment influenced how threat was framed. In the United States, where anti-abortion elites were classifying abortion as an elective, non-essential procedure, organizations pointed to the fact that abortion is a time-sensitive procedure that is legal. On March 27, NARAL Pro-Choice California tweeted, “REMEMBER, #abortion is still legal in ALL 50 states. Never let the radical right’s ideology prevent you or a loved one from receiving the healthcare they may need during this global pandemic.” The pandemic was viewed as threatening the (often already precarious but still legal) status quo that allows access to abortion. In Northern Ireland, where abortion was decriminalized in October 2019 but had not yet been made available due to the devolved government’s inaction, defense of the status quo was less prominent even when the tweets focused on threat. Alliance for Choice argued that the crisis exacerbated the problems of not having abortion access with a quote from a linked article on July 13, “‘Decisions made at every level of the response to the pandemic are resulting in women being further cut off from sexual and reproductive health services, threatening sharp rises in maternal and neonatal mortality.’” The policy context—with abortion being legal but threatened in one country and abortion being recently decriminalized but not available in the other—colors the way in which the crisis was presented as a threat.

Movement-countermovement dynamics also emerge when SMO rhetoric is put into the organizational schema of “threat” and “opportunity.” When proponents of abortion rights in Canada tweeted about the threat that the virus posed to people’s access to abortion and demanded that the government reinforce existing abortion rights by ensuring access to abortion during the pandemic, opponents of abortion in Canada responded to these calls with frames of opportunity. For example, We Need a Law posed the question, “When will the Canadian public wake up to the deeply contradictory stance of staying home to protect the vulnerable, while keeping abortion clinics open to kill the vulnerable?” (We Need a Law 2020). This tweet, based in the context of the lockdown, points to the opportunity provided by the unique circumstances of the COVID-19 crisis for people to perceive contradictions in the policy environment and it implies a solution: making abortion unavailable during the crisis (and beyond).

Anti-abortion messages were also categorized as framing the crisis as a threat to their cause when their opponents saw opportunity. In Canada, the Campaign Life Coalition tweeted on April 2 about the threat of government leaders allowing expanded access to the abortion pill due to the pandemic: “#Proabortion groups continue to urge Governments to keep abortion available during the #covid19 crisis. It's troubling that women's health is being endangered by resorting to telemedicine and DIY at-home abortions without any medical supervision.” The potential expansion of access to abortion pills and allowing women to take them at home rather than at a doctor’s office was also seen in Northern Ireland and accompanied a call from Precious Life for their supporters’ direct action: “WE NEED YOUR HELP Alliance for Choice and other Abortion obsessed activists are using #Covid_19 to place pressure on Northern Ireland's Health minister-Robin Swann MLA to legalise First Trimester At Home Abortion Pills!” (Precious Life 4/06/2020). The tweet contained a link with instructions on how to email the Health Minister and voice opposition to “DIY” abortions. This “threat” of expanded access to abortion pills, in turn, became a major issue for abortion rights advocates who saw the pandemic as an opportunity to argue in favor of such expansion.

The COVID-19 Crisis as a Critical Opportunity

The Covid-19 crisis also provides an opportunity, as increases in self-care and the use of telemedicine are expected. #SheMakesHerSafeChoice.

—Abortion Rights Campaign, April 18, 2020While the pandemic posed a serious threat across many arenas of life, the same disruption of the status quo that made it a threat also supported frames that emphasized opportunities for change. For the anti-abortion rights organizations, as noted earlier, opportunities typically came in the form of new ways to argue for the shutdown of abortion clinics—for the sake of public health—even if only temporarily. For example, Massachusetts Citizens for Life posted on May 8, 2020: “What about the double standard of performing elective surgeries during a public health crisis? … performing #abortion during #covid19 risks women's lives, & public safety.” Another way the crisis was framed as opportunity by these actors was in arguing that lives were being saved due to decreased abortion access during the pandemic, as seen in a tweet by Campaign Life Coalition on July 23, 2020: “The little lives saved by #Covid—but the #abortion industry isn’t pleased.”

For pro-abortion rights organizations, framing the crisis as an opportunity focused on the expansion of access to abortion pills through telemedicine and on challenging regulations such as waiting periods that require women to visit doctors’ offices multiple times before obtaining abortion pills (Mifepristone and Misoprostol). The travel restrictions and social distancing requirements put in place during the pandemic created new discursive opportunities relating to these goals. The quote by the Abortion Rights Campaign in the Republic of Ireland is an example. In their tweet, Abortion Rights Campaign literally states that the crisis could provide an opportunity for expanded access to abortion as “self-care.” The case of the Republic of Ireland is not only an example of crisis being framed as opportunity but also an example of crisis actually creating opportunity, as the government made access to early abortion via telemedicine a reality on April 8, 2020, only three weeks after the Abortion Rights Campaign and their allies first called for it to be introduced. As the tweet suggests, Abortion Rights Campaign saw the move to make abortion accessible at home during the pandemic due to stay-at-home orders as a first step toward widening norms of abortion self-care.

Telemedicine in the Republic of Ireland also helps to address it as an outlier in the analysis seen in table 2, where the Pro Life Campaign is the only anti-abortion organization across the four countries that tweets about COVID-19 proportionally more than the pro-abortion rights organization. In response to the Abortion Rights Campaign calling for abortions via telemedicine, the anti-abortion Pro Life Campaign responded by arguing that the idea of home abortions is “medically reckless” (Pro Life Campaign 2020) and dangerous for women. But the Pro Life Campaign did not tweet very often at all, and beyond a few tweets and a press release about the dangers of home abortion, they became generally silent about abortion during the pandemic and instead turned their attention to other issues, such as the impact of COVID-19 on the elderly. The anti-abortion movement’s decisive loss in the 2018 referendum on abortion seems to be reinforced in the government’s response to the pandemic and their relatively quick implementation of telemedicine for abortion access and this may explain why the Pro Life Campaign began to focus its efforts concerning the COVID-19 crisis on other issues.

The crisis was also frequently seen as a critical opportunity by pro-abortion rights organizations in Northern Ireland, who pushed for the need for home abortions via telemedicine because women could not travel to England to obtain an abortion during the pandemic. The issue of telemedicine had already been on the Alliance for Choice agenda as a core issue for rural and marginalized people prior to the COVID-19 crisis. The crisis opened new opportunities to attempt to put the issue more solidly on the political and public agenda. For example, Alliance for Choice posted on April 4, 2020, “There is no reason why NI cannot follow England, Scotland, & Wales in implementing telemedical abortion provision, and the failure to do so is causing, and will continue to cause, undue harm to thousands of women throughout the pandemic. #TelemedicineNow4NI.” The crisis presented a unique opportunity for the problems inherent in the abortion policy environment to be clearly singled out and a solution to these problems to be identified, especially by highlighting the way devolution was impacting women in Northern Ireland.

As of the writing of this article, telemedicine for abortion in Northern Ireland was a battle that had not yet been seen to completion. The efforts by the anti-abortion organization Precious Life were focused on this competition over telemedicine as they argued against what they called the “outrageous push for dangerous and deadly DIY Home Abortions” (Precious Life 2020), which falls more squarely in the category of framing the crisis as a threat and defending the status quo, though these responses were clearly prompted by the organizations’ desire to counter-frame the issue (McCaffrey and Keys Reference McCaffrey and Keys2000) and they are also very close to arguments made by anti-abortion organizations in the other countries in this study. Indeed, Precious Life rarely addressed the COVID-19 crisis in their tweets and so framing it as a threat or an opportunity were both relatively rare.

In the United States and Canada, calls for telemedicine and home abortions were also present. For example, NARAL tweeted messages such as, “The #COVID19 crisis has exposed significant gaps in the reproductive care system. The solutions are clear: telemedicine abortion, free birth control, ACA-covered reproductive care. Safeguarding access is crucial, even more so during a pandemic” (NARAL, April 4, 2020). This message mixes the threat to access with the opportunity presented by the crisis to see the problems in the current policy environment that need to change. But in the United States, because abortion access was legal and actively under threat due to attempts to classify it as non-essential, addressing this took precedence over calls for home abortions. Table 3 shows the percentage of COVID-19-related tweets that were coded as either “threat” or “opportunity” frames from the organizations in each country.

Table 3 Percentage of COVID-19 tweets framing the crisis as threat or opportunity*

* Tweets that were not about abortion or did not frame the crisis were coded as “other” and are not included in this table.

The table reveals that, across the countries, when pro-abortion rights organizations substantively framed the crisis, they tended to frame the crisis as a threat except in Northern Ireland. Anti-abortion organizations were also more likely to frame the crisis as a threat rather than an opportunity except in the United States. In the United States, the federal organization (National Right to Life Committee) framed the crisis equally as a threat and an opportunity, while at the state level, the anti-abortion organizations framed the crisis an opportunity by a larger margin. These findings point to some fascinating possibilities in explaining how social movements respond to crisis, with a combination of ideology and policy environment presenting as influential. In places where the abortion debate is arguably most competitive (currently, the United States and Northern Ireland), some organizations capitalized on the opportunities afforded by the crisis. But overall, most of the organizations, regardless of ideology and context, tended toward framing the crisis as an external threat and crafted messages about how to manage abortion access in light of this threat.

Conclusion

I apply crisis exploitation theory to social movement organizations and test whether SMOs adjust their activities and rhetoric on Twitter to “exploit” crisis in order to further their goals. Based on previous literature on social movements and elite crisis exploitation, I expected that movements working toward changing the status of abortion would be more likely to proactively exploit the COVID-19 crisis despite different situations across countries. This does not seem to be the case. Instead, pro-abortion rights organizations tended to tweet more frequently about the COVID-19 crisis compared to their opponents across the countries. Only after pro-abortion rights organizations began framing the crisis did their anti-abortion opponents join them in this crisis rhetoric—which supports the second expectation of this study concerning movement-countermovement dynamics. Beyond this example of how opposing movements engage in framing competitions, this study makes several other contributions.

First, I provide a mixed-methods, systematic analysis of the rhetoric of anti- and pro-abortion organizations across four countries and find similarities in their responses to the crisis that may be classified into three overarching categories of crisis-type rhetoric. These categories show that, while policy environment certainly played a role in these organizations’ approaches to framing the crisis, most of the organizations sometimes framed the crisis as both a threat and an opportunity, with the most emphasis placed on threat. While anti-abortion organizations were less likely to respond to the crisis in their rhetoric overall (in the Republic of Ireland the anti-abortion organization did tweet about COVID-19 at a higher rate but these tweets were often about non-abortion issues), all of the organizations acknowledged the impact of the crisis on society to some extent. This may be due to the unique features of the COVID-19 crisis that made it challenging to ignore.

Second, social movement response to crisis is understudied, as frequently these responses are analyzed only when a crisis is a clear “focusing event” for the movement and not when the crisis is wide-spread and its impact dispersed. This study builds on our knowledge of how movement organizations deal with punctuations that disrupt their routines and reveals that SMOs in four countries—regardless of position relative to the status quo and ideology—were compelled to respond to the crisis in some way, incorporating it into their arguments in sometimes quite provocative ways. For example, the Canadian Centre for Bioethical Reform, an organization known for its controversial use of images of fetuses, posted on March 26, 2020, “During the crisis, truck drivers are essential. Our truck drivers are dedicated to bringing the truth to the public when we can’t have face to face conversations” (Canadian CBR 2020). Attached to the message, which originally was posted on Instagram, was a photo of one of their trucks with an image of an aborted fetus and the message “Abortion Kills Children.” While most of the rhetoric used by anti-abortion organizations was not like this, it is an example that highlights the myriad ways in which abortion was framed in the terms of the pandemic.

Finally, my research suggests that status as the movement for or against change does not seem to be the core driver of movement organizations’ rhetorical responses to the COVID-19 crisis, calling into question the usefulness of applying these categories during crisis. Given what we know about social movements, it is surprising that SMOs, especially pro-change SMOs, did not proactively exploit the crisis as an opportunity more. It may be that the wide-spread impact of COVID-19 made organizations quick to see its potential to be used by opponents to either expand or restrict abortion access. Therefore, it was primarily seen as a threat, though typically not exclusively. This is reinforced in that the only SMOs to frame the crisis as an opportunity more than as a threat were pro-abortion rights activists in Northern Ireland, where there is currently no access to abortion to be defended, and anti-abortion activists at the state-level in the United States, where elite actors began restricting abortion early in the pandemic (though these attempts were challenged and eventually reversed; see Sobel et al. Reference Sobel, Ramaswamy, Frederiksen and Salganicoff2020).

The role of ideology and elite responses to the pandemic evidently is important to how social movements respond to the crisis on social media and this is further reason to continue research into how SMOs exploit crisis. Future research would benefit from studying the rhetoric of elites and comparing it to social movement organization rhetoric during both “normal times” and times of crisis to explore the dynamics between social movements and their elite allies or foes. Another compelling possibility is to study SMO responses to different crises, comparing responses to the COVID-19 crisis with a crisis more targeted and relevant to specific movements. Finally, because movements form in response to perceived injustices, problems, or threats, they may tend to see the world in terms of crisis and managing crisis. The use of Boin, ’t Hart, and McConnell’s categories of “ignoring/downplaying,” “threat,” and “opportunity” could be gainfully applied to social movement framing in non-crisis moments and compared to framing during crisis to reveal more about the extent to which crisis influences the general framing strategies and mobilizing tactics of movements.

The current research leaves us with relevant questions and avenues for future research and also contributes to these ongoing conversations by revealing that during the COVID-19 crisis, the movement for change in a country was not necessarily the movement that tweeted about the crisis the most in an attempt to exploit it. While the reason anti-abortion actors were reluctant to directly address the COVID-19 crisis in their tweets may have been political, the way in which the crisis was addressed does not seem to have been driven by the same force, and anti- and pro-abortion actors at times framed the crisis as both threat and opportunity—influenced by their relative policy environments.

Acknowledgments

She would like to thank the editor, Michael Bernhard, and the four anonymous reviewers for their excellent and thoughtful suggestions during the review process. Thank you to Mike Gruszczynski for his helpful feedback on the manuscript.