Introduction

Although primary elections were limited to the US context for almost a century, they have spread to many Western countries in the last few years. Consequently, notwithstanding the relative novelty of the phenomenon, academic studies in the field have exponentially increased over the last decade (Caul Kittilson and Scarrow, Reference Caul Kittilson and Scarrow2006; Hazan, Reference Hazan2006; Hazan and Rahat, Reference Hazan and Rahat2010; Astudillo, Reference Astudillo2012; Krouwel, Reference Krouwel2012; Cross and Blais, Reference Cross and Blais2012a, Reference Cross and Blaisb; Pilet and Cross, Reference Pilet and Cross2014; Gauja and Cross, Reference Gauja and Cross2015; Kenig et al., Reference Kenig, Cross, Pruysers and Rahat2015; Sandri et al., Reference Sandri, Seddone and Venturino2015; Boatright Reference Boatright2018). As a matter of fact, the term ‘primaries’ specifically refers to the selection of candidates for national or local elections involving all party members or, at least, party sympathizers (Pasquino, Reference Pasquino2006; Kenig et al., Reference Kenig, Cross, Pruysers and Rahat2015). Yet, this concept has been often used beyond its narrow meaning, to indicate more generally the growth of intra-party democracy and the involvement of a growing number of people in candidate and leader selection or in a party’s internal decision-making process (Kenig and Rahat, Reference Kenig and Rahat2012; Sandri et al., Reference Sandri, Seddone and Venturino2015). In fact, Kenig and Rahat (Reference Kenig and Rahat2012) talk of a ‘primary zone’, which also includes procedures of selection like party conventions and congresses.

The purpose of the paper is try to assess whether inclusive procedures of selection such as open or closed primary elections are more likely to select a candidate who can be competitive in the general election, compared with both ‘primary zone’ and top-down procedures. Of course, the present paper does not intend to solve an issue that is likely to continue to absorb the attention of scholars for a very long time. Nonetheless, it aims to provide a contribution to the debate by enlarging the empirical studies on candidate and leader selection at the European level, as comparative research in the field is still lacking.Footnote 1

Thus, after a brief section intended to justify the case selection, the following one summarizes the vast literature concerning the relation between primary elections and electoral performance. Subsequently, I introduce the main indicators to measure inclusiveness and next I present the respective empirical evidence concerning the 40 nomination processes (NPs) considered. The fifth section extensively presents both quantitative and qualitative considerations concerning the possible relation between electoral success and inclusiveness of the nomination process. In the conclusion this relation is investigated in a more general manner, also suggesting future research in the field.

Case selection and time-span

The sample includes 40 cases of national chief executive candidate selectionFootnote 2 from four Western European countries: France, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Specifically, I considered NPs intended to appoint prime ministerial/presidential candidates for the last five general elections (Presidential elections in France) held in each country.Footnote 3 As each country presents its own peculiarities in terms of mandate duration of Parliament/national executive and number of anticipated elections, the time-span varies from country to country. Yet, I preferred to focus on the same number of elections for all the considered countries rather than selecting a specific period of time, which would have meant having a country (i.e. France) with far fewer empirical cases to be observed compared with the others (especially Spain). All the considered empirical cases are presented in the appendix (see the replication dataset).

Table 1 Selectorate inclusiveness on a 10-points scale

a Incumbency means that the outgoing Prime Minister or President decides to stand for re-election and nobody (formally) opposes his/her candidacy. This category includes both informal decisions by the founding/outgoing leader (McElwain, Reference McElwain2006) or by the party elite and the candidate(s) involved, and uncontested races requiring a formal approval by the party top organs (Executive Committee, Parliamentary Party Group, etc.).

The aim was to maintain a coherent and homogeneous sample but also to guarantee variability in terms of candidate selection methods. Accordingly, the country selection includes two countries (Italy and France) where open primary elections have been widely experimented in the last decade; a country like Spain, which occasionally recurred to closed primaries and ‘primary zone’ systems during the last two decades; and the United Kingdom, which displays its own characteristic ways of leadership selection.

These five countries differ in terms of political traditions, electoral systems, forms of government, and party systems. Yet, in recent decades they have all been characterized by a similar centripetal competition articulated around two main parties or coalitions. For comparability reasons I decided to look at candidates and parties able to compete in the election for the country’s government (although in coalitions with smaller parties). Thus I only considered NPs addressed by the main nationwide centre-left and centre-right party in each country: the Socialist Party (PS) and the RPR/UMP/Republicans in France, the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) and the Popular Party (PP) in Spain, the Labour Party and the Conservative Party in the United Kingdom, the Democratic Party (PD) and the People of Freedom (PdL) in Italy.Footnote 4 In three out of four countries the political competition is no longer organized around these two parties, as there are currently other forces able to compete for the national government or the Presidency of the Republic, but these parties could not be included because they did not run in previous elections.

As for the time-span, the choice to consider a relatively short period (approximately the last two to three decades) was intended to guarantee a certain balance in the level of NPs inclusiveness. In fact, the more we look at the past, the more non-inclusive NPs do we find.

Primary elections and electoral performance: a wide-open debate

The relation between primary elections and electoral performance is one of the most highly debated issues in the literature on candidate and leader selection both in the United States and (more recently) outside, but a consensus fails to emerge.

The first point to be addressed is: are primary voters (also called ‘selectors’) strategic (i.e. they vote for the candidate who is most likely to win the general election) or do they tend to cast an ‘expressive’ vote? According to several US scholars (Bradyet al., Reference Brady, Han and Pope2007; Kernell et al., Reference Kernell, Jacobson and Kousser2009), those who take part in primary voting represent the most ‘extremist’ sections of a party, and therefore they sometimes tend to choose candidates who are not appreciated by the general electorate. Nevertheless, Katz (Reference Katz2001) claims that the enlargement of the selectorate is a way to counterbalance the weight of party activists in the process of selection, as the latter tend to be more attentive to ideology and policies than to the electoral appeal of a candidate. Other scholars stress that primary voters are very sensitive to the influence of opinion polls (Dolez and Laurent, Reference Dolez and Laurent2007; Lefebvre, Reference Lefebvre2011), which means that ‘electability’ (i.e. the capacity to win the general elections according to the polls) becomes the main criterion for choosing among candidates (Colomer, Reference Colomer2002; Ivaldi, Reference Ivaldi2007). Adams and Merrill (Reference Adams and Merrill2014) demonstrate a ‘strategic voting equivalence result’, according to which the best option for primary candidates is to adopt policy strategies addressed to the general electorate even when they expect primary voters to behave expressively. Accordingly, the candidates’ optimal strategies for expressive primary voting are strategies that make these candidates electable, which implies appealing to strategic primary voters, too.

Still, Massari (Reference Massari2004) claims that when party members and/or sympathizers who vote in the primary election surpass a certain threshold (hundreds of thousands of voters), the outcome is closer to the preference of the wider electorate, while in case of more limited participation the result is likely to reflect the preferences of militants and activists more concerned with ideological purity than electoral aims. Similarly, Venturino and Pasquino (Reference Venturino and Pasquino2009) maintains that the selectorate is actually very different from the general electorate only in the case of closed primaries, while the selectors who vote in open primaries are more representative of the characteristics and attitudes of the wider electorate.

Some scholars (Carey and Polga-Hecimovich, Reference Carey and Polga-Hecimovich2006, Reference Carey and Polga-Hecimovich2008) claim that candidates selected through primaries take advantage of a primary bonus in the general election, since the voters tend to sympathize for candidates whose election testifies the existence of intra-party democracy. In addition, primaries can contribute to solving internal diatribes on candidacies in a transparent way (Pasquino, Reference Pasquino2005). Moreover, the legitimation and publicity usually associated with primaries may strengthen the leader’s position in the post-primaries phase and thus improve his/her electoral prospects.

More recently, Ramiro (Reference Ramiro2016) confirmed the idea of an ‘electoral bonus’ for parties promoting primaries, on the basis of his empirical analysis of the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party’s performance in local elections. Specifically, he states that parties will achieve the best results in elections with high turnout and little competition in the primaries, which might show the popularity of the candidate. US scholars generally appear more pessimistic about primaries’ electoral effects than their European (and non-European) colleagues. American literature has long referred to a primary penalty that can damage the candidate at the general election, especially in case of divisive primaries (Hacker, Reference Hacker1965; Bernstein, Reference Bernstein1977; Ware, Reference Vicentini1979; Kenney and Rice, Reference Kenney and Rice1984; Kenney, Reference Kenney1988; Atkeson, Reference Atkeson1998; Hogan, Reference Hogan2003; Romero, Reference Romero2003; Carey and Polga-Hecimovich, Reference Carey and Polga-Hecimovich2006; Pierson and Smith, Reference Pierson and Smith1975; Makse and Sokhey, Reference Makse and Sokhey2008; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Petersheim and Wasson2010; Wichowsky, Reference Wichowsky2010; Lazarus, Reference Lazarus2018). When the primary outcome is very close, there is an increase in the risk that a certain percentage of selectors who supported the losing candidate(s) will not vote for the winner in the general election, preferring abstention or even a vote for the candidate of the opposite front. In fact, Southwell (Reference Southwell1986) demonstrated that both American parties have been plagued by a considerable amount of disloyalty on the part of supporters of candidates who failed to win the nomination. The behaviour of these ‘disgruntled primary voters’ can be interpreted as a reflection of factional politics in which primary elections may also be used to arbitrate between rival factions.

However, the complexity and multi-causality of electoral behaviour call for caution regarding the hypothetical magnitude of the impact that variation in candidate selection methods may have on electoral support. In fact, some studies of non-European cases have found that internal competition often does not affect party electoral performance (Galderisi et al., Reference Galderisi, Ezra and Lyons2001; Carty et al., Reference Carty, Eagles and Sayers2003; Hazan and Rahat, Reference Hazan and Rahat2010). At the same time, some Italian scholars have stated that vigorous competition can even improve – rather than damage – the electoral outcome of the primary winner (Seddone and Venturino, Reference Seddone and Venturino2010; De Luca and Venturino, Reference De Luca and Venturino2017). A spectacular horse-race, they suggest, promotes the candidate’s image among the public at large, while a victory over competitive party challengers allows the winner to overcome internal factionalism, an element which may appeal to voters, who are generally allergic to intra-party divisions. In addition to this, the advocates of primary elections tend to stress that this instrument gives the chance to identify new leaders/candidates with potentially large popular support even when they are not important personalities within the party. According to this point of view, a vast selectorate is more likely to single out a young, communicative and charismatic candidate, who is also more likely to be electorally competitive in our era of ‘personalized politics’ (Massari, Reference Massari2004; Valbruzzi, Reference Valbruzzi2005; Pasquino, Reference Pasquino2006).

To sum up, the benefit of a primary is to enhance the expected valence of the nominee. On the contrary, its cost is the ideology that primary voters may impose on the party’s policy platform (Serra, Reference Serra2011) as well as the conflicts that may derive from a divisive race.

Assessing inclusiveness: not only (selectorate) size matters!

Although research focusing on the relation between candidate selection inclusiveness and electoral performance is not very widespread at the European level, studies concerning categorization and operationalization of selection methods abound (Kenig, Reference Kenig2009; Hazan and Rahat, Reference Hazan and Rahat2010; Pilet and Cross, Reference Pilet and Cross2014; Spies and Kaiser, Reference Spies and Kaiser2014). According to the literature in the field, the Table 1 main indicator to assess inclusiveness is the type of the selectorate, that is, the group of people called on to choose the candidate: the larger it is, the more inclusive the process. Pilet and Cross (Reference Pilet and Cross2014) consider six types of selectorate, ordered from the most to the least inclusive: membership, delegates, party council, party parliamentary group, and party leader. Mixed selectorates are also quite widespread, and in the last few years some parties have even involved party voters/sympathizers in candidate selection. However, the type of selectorate by itself is a rather trivial indicator of inclusiveness (in that it does not allow us to properly discriminate between different empirical cases) if we do not take into account other elements.

The central aspect to be considered is the extent to which the selectors are really free to decide on candidacies. Accordingly, first of all we have to distinguish between contested and uncontested races. In fact, a large selectorate may be called on to certify with a formal vote the nomination of a single candidate that has in fact already been decided. Thus, quite obviously, a contested race is assumed to be more inclusive than an uncontested one, regardless of the type of the selectorate (Kenig, Reference Kenig2009). That said, considering the whole set of NPs included in my sample and in order to properly discriminate among different empirical cases, the level of inclusiveness has been measured according to a 10-point scale, as shown in Table 1.

Another dimension which is usually considered in assessing inclusiveness in candidate and leader selection is the candidacy. Scholars usually address the candidacy dimension by focusing on the formal requirements needed to run as a candidate (Hazan, Reference Hazan2006; Kenig, Reference Kenig2009; Barberà et al., Reference Barberà, Bares, Bario and Teruel2010; Hazan and Rahat, Reference Hazan and Rahat2010). The more demanding the requirements, the less inclusive the candidacy. There are, nonetheless, a few authors who try to measure this dimension in a less formal way, by addressing the role played by the party elite in forming and possibly manipulating the candidates’ list in order to help the success of a single intended winner and/or avoid a divisive contest (Castaldo, Reference Castaldo2009; Vicentini, Reference Ware2014). According to this approach, the candidacy dimension is likely to affect the competitiveness of the race directly, though formal requirements may also have an impact. Thus, I intend to look to the effective number of candidates (ENC) as a control variable, in order to account for the impact of ‘factional politics’. Indeed, where there is only one effective candidate, I expect less divisiveness and fewer ‘disgruntled’ primary voters. The ENC was originally used by Kenig (Reference Kenig2009) to calculate the index of competitiveness/dispersion of leadership contests, and it is calculated in the same way as the effective number of parties by Laakso and Taagepera (Reference Laakso and Taagepera1979): ENC=1/∑Vi 2, Vi representing the share of votes of the candidate.

Finally, some studies suggest that candidates selected by non-competitive but highly participated primaries are more likely to win the election. Thus, another control variable refers to the number of people actually voting. In fact, the type of selectorate does not perfectly coincide with the size of the selectorate, although the literature typically uses selectorate type as an approximation to selectorate size. Of course, the more the selectorate is inclusive, the higher the expected number of people who will take part in the vote, especially in case of candidate and leader selection at the national level. However, the same selectorate may involve different numbers of people. For example, parliamentary party groups may range from a few individuals to hundreds of members. Party membership sizes also vary considerably, from a few hundred or thousand (or even fewer) to several hundred thousand, and voting turnout is also likely to change from ballot to ballot. Thus, I also consider the size of the selectorate and the level of participation, that is, the actual number of people who participated in the ballot, according to the criteria set in Table 2

Table 2 Number of selectors

.

NPs inclusiveness in four Western European countries: an overview

As shown by Table 3, the sample is balanced in terms of contested and uncontested races (19 vs. 21). Among uncontested races the best-covered category is clearly the one including incumbent candidates and candidates formally or informally appointed by the party elite. However, there are also few exceptions: the Spanish Popular Party recurs to a formal congressional vote by the party delegates in order to ratify the election (or reconfirmation) of the party leader, who is also the prime ministerial candidate to the general election. Moreover, we also have the very peculiar case of an uncontested closed primary to appoint Nicolas Sarkozy as UMP candidate for the 2007 French presidential elections.

Table 3 Overview of 40 nomination processes in four countries

ENC, effective number of candidates.

The ‘contested race’ category is characterized by larger variability in terms of selectorate inclusiveness, ranging from a vote of the parliamentary party group (as for the British Conservative party in 1997 and 2016) to party congresses with votes from delegates (the election of Zapatero as new PSOE leader in 2000), and to a dozen cases of closed and open primaries. Most of the time, these very inclusive selectorates are accompanied by a number of effective candidates larger than two. In some cases, however, (mainly in Italy) it is possible to suspect that the party elite had secured itself against unexpected results by intervening in the pre-selection phase in order to reduce the candidate offer, effectively producing a race in which, despite a high number of official candidates, the victory of one was beyond doubt.

While the Italian centre-left has been the ‘champion’ of open primaries since 2005 (long before the first experiments of primaire à la française took place), both main parties in France and the centre-left party in Spain recurred to the vote by the entire party membership at least once.

Yet, there are a few hybrid cases which deserve special mention. In fact, the British case represents a perfect example of ‘mixed selectorate’. On the one hand, we have the ‘electoral college’ system, adopted by the Labour Party from the beginning of the 1990s until the most recent reform of 2010. According to this system, the electoral college entrusted the selection of the party leader (who is automatically designed as prime ministerial candidate) to three different organs: 33% of the votes belongs to the party parliamentary group (both MPs and MEPs), another 33% rests in the hands of party members in the various constituencies, while the last third is entrusted to members of the Trade Unions. By contrast, since 2001, the Conservative party has chosen its leader through a system consisting in a series of eliminatory ballots led by the parliamentary party, which end up with a membership vote between the last two remaining candidates. The literature does not offer univocal indications to properly assess the inclusiveness of these kinds of systems in comparison with systems recurring to a unique selectorate. Yet, I would argue that the Conservative system falls halfway between closed primaries (involving only the party membership) and a vote by the party’s higher bodies. Thus, in terms of inclusiveness, I consider this system to be more inclusive than party congresses but less than a normal membership vote.

The Labour case is more complex. Oh the one hand the size of the selectorate goes beyond normal closed primaries, as it also encompass trade union members. On the other hand, the fact that the votes of hundreds of thousands of party and trade union members count no more that the votes of a few hundred MPs/MEPs suggests that we should consider this kind of ‘mixed selectorate’ slightly less inclusive than a party membership vote (but still more inclusive than the Conservative system).

Because of this peculiar mixed selectorate, during the 2000s the United Kingdom seemed to be the country where the selection procedures adopted by the two main parties converged the most. Nonetheless, things have changed recently, as the Labour party has moved towards a real one-member-one-vote system by adopting closed primaries to select its leader, a system that in fact has been largely depicted as ineffective and unreliable by the Conservatives. Actually, the Labour closed primary allows people from outside the party to register as ‘supporters’ and vote by paying a small fee (3£ at the beginning, successively increased up to 25£), while members of the trade unions are allowed to vote for free but have to register in advance. This makes the selectorate size larger than a normal party membership ballot, to the point that some observers defined this system as a ‘semi-open primary’ (Ware, Reference Ware2018: 35).

That said, France is currently the country presenting most similarities, as both centre-left PS and centre-right LR recently adopted open primaries to select their presidential candidate. On the contrary, in Italy there is the greatest distance between the by-now stabilized system of open primaries adopted by the Democratic PartyFootnote 5 and the ‘self-enthroned’ centre-right leadership of Berlusconi (Kenig, Reference Kenig2009). However, it is worth noting that Berlusconi’s inevitable decline has recently encouraged different centre-right leaders to demand primaries in order to select his successor. National coalition primaries were even formally scheduled for December 2012 but were finally abandoned when Berlusconi announced his intention to run for the sixth time as prime ministerial candidate in the 2013 general elections. Yet, a few attempts have been experimented at the local level, and the leadership of the (Northern) League – namely Berlusconi’s most important coalition partner, which also became the senior coalition partner after 2018 elections – has been decided by closed primaries. Accordingly, we cannot rule out that in the near future the selection procedures employed by the Italian centre-left and centre-right will resemble each other. Yet, the paradox of the 2018 Italian elections was that neither the centre-right coalition nor PD had a designed chief executive candidate. Nonetheless, Berlusconi acted as the coalition leader despite being unelectable after he was banned from public office due to his conviction for tax fraud in 2013.

Finally, the Spanish Popular Party seems to be one of the few European parties that has remained impenetrable to the ‘contagion’ (Sandri et al., Reference Sandri, Seddone and Venturino2015) of the tendency to democratization of candidate and leader selection methods, probably also because of its lasting permanence in power. By contrast, the PSOE is now used to closed primaries for the selection of the party leader, but still appears slightly more hesitant than its Italian and French centre-left counterparts in moving towards open primaries.

Assessing the relation between NP inclusiveness and candidate electoral performance

Correlation coefficients

Existing literature suggests that an inclusive process of candidate selection may either hurt a party by selecting extremist candidates and/or producing internal conflicts or improve performance by selecting high-valence candidates and/or enhancing a party’s image. As I have already pointed out, this everlasting dilemma between primary penalty and primary bonus is likely to absorb the attention of scholars for a very long time. In fact, my findings do not provide clear results in either direction.

Because of the small-N problem, the use of sophisticated statistical analyses is not recommended. Thus, at first I simply correlated the inclusiveness of each NP (measured on a 10-points scale) with a measure combining two indicators that I took as a proxy of the candidate electoral performance: (1) the distance between election victory and defeat (i.e. closeness between first and second most-voted party); and (2) differences (losses and gains) between the election under scrutiny and the previous one.Footnote 6 In fact, I could not simply consider the percentage of votes, as the different party systems and candidate/party offer mean that a 40% result for a mainstream party in one country (e.g. the United Kingdom) is not comparable with the same result in another country (e.g. Italy or France).

Moreover I also correlated NP inclusiveness with a dummy variable that accounts for the most obvious requirement of electoral success for a major office-seeking party, not necessarily addressed by the two previous indicators, namely the chief executive candidate’s ability to get into office: President of the Republic in France or Prime Minister able to form a government in the other three countries with a parliamentary system.

Of course, there are a lot of intervening variables that are likely to affect electoral performance: the electoral campaign, the overall economic situation of the country, a changing political offer, the government approval rate and so on and so forth. Unfortunately, controlling all these variables is not possible here because of the small-N and because it would require an enormous amount of supplementary work, but at least I can account for the effect of two variables that are already included in my data set, that is, incumbency and party/candidate left-right positioning (ideology). Moreover, I also controlled for the condition of favourite candidate/party according to the average of pre-electoral polls.

The findings are shown in Table 4. If we do not control for the previously mentioned intervening variables, we get negative correlation coefficients, but they are too close to zero to hypothesize a linear relation between inclusiveness and electoral performance. Once we control for these variables, even the very weak orientation that I found at the beginning completely disappears. This is because, on average, incumbent and centre-right candidates/parties included in my sample perform slightly better than centre-left and non-incumbent candidates/parties.

Table 4 Nomination processes (NPs) inclusiveness vis-à-vis electoral performance

The (negative) correlation coefficients increase a bit when controlling for the ENC, but they remain rather low and not significant at conventional levels. Moreover, the correlation is much lower controlling for incumbency and ideology. However, even this very small increase suggest that ‘factional politics’ is a variable to be taken into account while addressing the effects of inclusive candidate selection processes. Instead, the effect of participation/selectorate size is by itself trivial, although it is true that candidates selected by highly participated and less competitive ballots are slightly more successful (or are less unsuccessful) than candidates selected by competitive and not highly participated ballots.

More specifically, among the 19 candidates selected by contested procedures, only seven performed quite or very well, meaning that the party/candidate was the most voted and increased its voting share compared with the previous election. Interestingly enough, even among the remaining 21 uncontested NPs we find only seven candidates who had a good or very good electoral performance.

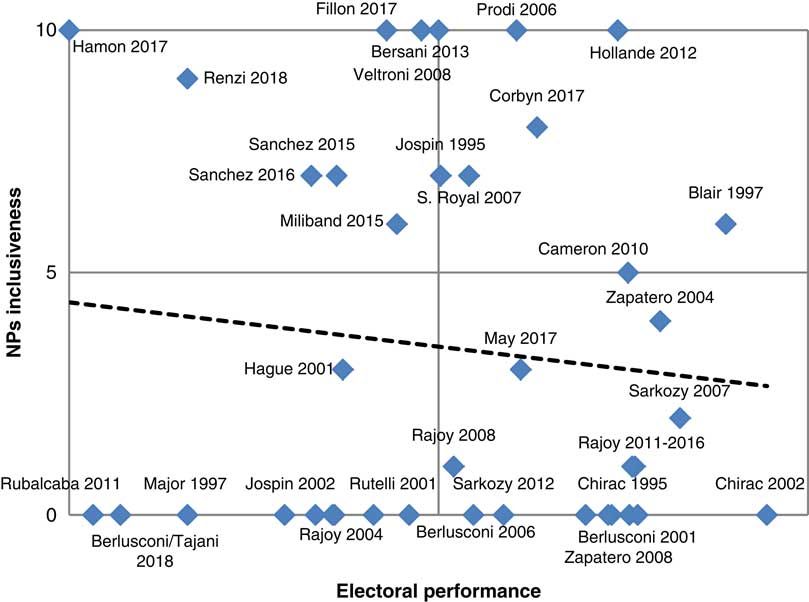

Moreover, nine out of 11 candidates selected by (contested) primaries lost the general elections. It is hard to notice clear distinctions in the electoral outcomes for candidates according to whether they were selected by closed or open primaries. In fact, we have four closed primaries (not counting the uncontested election of Sarkozy by UMP members in 2007) with no electoral success (although Corbyn did show a good electoral performance), and seven open primaries with only two winning candidates (but one, Prodi in 2006, succeeded with an incredibly small margin and was unable to secure a solid parliamentary majority) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Nomination processes (NPs) inclusiveness vis-à-vis candidate electoral performance.

Instead, three out of four candidates selected by ‘primary zone’ systems, namely contested races characterized by a medium level of inclusiveness (party congress: Zapatero; electoral college: Blair and Miliband; party members+MPs vote: Cameron) won the elections. In fact, if we exclude ‘primary zone’ contests and we only look at uncontested races vis-à-vis (closed or open) primary elections, the negative correlation between NP inclusiveness and electoral performance increases a bit (−0.126; −0.216). Still, this is insufficient to embrace ‘primary penalty’ theories, as also shown in the scatter-plot above. Accordingly, further ‘qualitative’ considerations are needed.

Do primary elections reward extremist candidates?

Arguments suggesting that inclusive mechanisms of selection tend to reward extremist candidates remain partly unconfirmed by my findings. The Republican nomination of Donald Trump in 2016 recently (re)confirmed that a radical outsider can be successful in US primaries, even against the will of his/her own party establishment. In Europe, too, and especially in Italy, this has occurred sometimes in procedures of selection held at the local or regional level. However, on the basis of the empirical cases considered here, my impression is that European selectors are generally ‘strategic’ when they are called on to select national leaders/candidates. In fact, they do not seem particularly willing to support outsiders or go against the preferences of the party elite. Rather, they generally reward the candidate who is considered more likely to win the nomination (viability) and the successive elections (electability), irrespective of his/her ideological stances. In fact, in most of the considered primaries and ‘primary zone’ NPs, the candidate who won the contest was the most ‘electable’ one and the one closest to the political centre (or at least not the most extremist): Jospin, Prodi, Blair, Cameron, Royal, Veltroni, Hollande, Sanchez, Renzi, Fillon.Footnote 7 Zapatero’s success in the 2000 PSOE Congress was quite unexpected, and the fact he only had a short political career at that time suggests he could be considered as a kind of outsider, but for sure he was not perceived as an extremist candidate.

However, in a few cases Kernell’s prediction proved correct: the success of Bersani against Renzi in the 2013 Italian primaries, that of Hamon in 2017 PS presidential primaries, that of Ed Miliband against his elder brother David in the 2010 Labour leadership election, and that of Jeremy Corbyn in the (two) successive Labour leadership contest(s). However, it is impossible to define Bersani and Ed Miliband as ‘outsiders’ or ‘extremist’ candidates: they were merely slightly more left-wing (and they campaigned to portray themselves as more left-wing) than their challenger(s), but still they were leading figures who could count on strong support within their parties (especially Bersani, who was the party chairman at the time of the primaries). The argument is different for Hamon and Corbyn, as I will explain further on. Still, it is true that these four candidates, for different reasons and in different ways, lost the general elections. As for Bersani, Miliband, and Hamon, many observers – media figures and political commentators more than scholars – suggested that their more moderate challengers (David Miliband, Matteo Renzi, Manuel Valls) could have done better (or at least less worse), but of course these are just speculations that cannot be verified. On the contrary Corbyn’s electoral performance has been widely portrayed as extremely positive (Dorey, Reference Dorey2017), as he obtained the best vote percentage for Labour in the last 15 years and prevented the Conservatives from winning an absolute majority of seats. In any case, I would suggest that the success of a ‘radical candidate’ in a primary election is not necessarily the result of a cleavage between the moderate general electorate of a country and the extremist members or sympathizers of a political party. Rather, it could reflect a shift in the political sentiment of the population, with new criteria for the voting choice replacing the ideological positioning of a candidate, such as political renewal, anti-establishment stances, personal charisma, and so on. Thus, supporting a ‘radical’ candidate could also be a strategic choice. On the other hand, Corbyn’s (partial) success (vs. the serious defeats of many apparently ‘electable’ candidates, as for instance Renzi in the 2018 Italian election) is just the latest demonstration that ‘electability’ and ‘electoral performance’ are not at all overlapping concepts, especially when the polls refer to the period in which the NP is held, which usually occurs many months (or even years) before the general elections.

Does primary divisiveness affect electoral performance?

The findings only partially confirm the theory that the electoral performance could be hurt by a divisive (i.e. very competitive) process of selection. Yet it is true that the (very weak) negative correlation between inclusiveness and electoral performance increases once controlling for the ENC. However, it is worth noting that many candidates who triumphed in the primaries with percentages between 60 and 70% ended up having unsatisfactory results in the general election. Thus, I suspect that the magnitude of the success in the NP is largely irrelevant, even if it is accompanied by huge participation: winning with a 40% margin over the challenger(s) is not necessarily better than winning with a 20% margin. Yet, winning with a tight margin is more likely to negatively affect the candidate’s successive electoral performance. This is well exemplified by the case of Ed Miliband, who conquered the Labour leadership against his elder brother with only a 1% margin after four voting rounds, and finally performed quite badly in the 2015 UK election. However, we also have a candidate (Zapatero) who won the party Congress with a very narrow margin (nine votes) but then performed extremely well in the election, although the outcome of the 2004 Spanish election was highly affected by external factors.

In any case, the concept of divisiveness does not end with the closeness between the competing candidates. In fact, we can also consider the level of negativity in the electoral campaign preceding the intra-party ballot (Djupe and Peterson, Reference Djupe and Peterson2002; Peterson and Djupe, Reference Peterson and Djupe2005; Venturino and Pasquino, Reference Venturino and Pasquino2009) as well as the party elite’s preferences among competing candidates. From this point of view, the primaries rewarding Corbyn were also clearly divisive, though he succeeded with a large margin over his challenger(s). Still, his electoral performance was good.

On the contrary, the latest Socialist primaries in France perfectly accord with the negative effect of divisiveness on electoral performance. Of course, the success of the leftist candidate Hamon must be placed in the context of overall bleak electoral prospects for the Socialists. Because of the unpopularity of the outgoing Hollande government, it was expected that no PS candidate would reach the second ballot of the Presidential elections. Thus, it is difficult to ascertain whether ‘ideological purity’ won over ‘electability’ in the mind of the Socialist selectors. It was unclear whether this trade-off was at stake in any meaningful sense, especially considering that the moderate candidate and outgoing Prime Minister Valls suffered from the same unpopularity as Hollande. That said, Hamon’s result in the first run of the presidential election was even worse than expected, with a mere 6.3%, making it the worst defeat in recent PS history and, more widely, one of the worst percentage results ever obtained by social-democratic forces in Europe. Interestingly, Hamon won the first round of the primaries with about 1.2 million votes. In the presidential elections, however, he gained slightly over 2 million votes, that is to say only 200,000 more preferences than the total votes expressed in the second turn of the primaries. This suggests not only that Hamon was unable to mobilize Socialist voters who did not vote in the primaries, but also that a (large) part of those who supported Valls in the primaries did not vote for Hamon in the election. This is not surprising, as Valls himself clearly stated that he would vote for Macron rather than backing the socialist nominee. Accordingly, albeit Hamon won with a decent margin over Valls (59 vs. 41%), the primaries proved to be divisive. It is also possible to suspect, moreover, that a part of Hamon’s own primary voters eventually decided to abandon their own candidate, possibly to benefit the extreme-left candidate Melenchon, who appeared to have more chances to reach the run-off.

Primary elections did not work very well for the main Socialists’ opponents either. In November 2016, when the Republicans celebrated the first open primaries in the history of the French centre-right, many people thought they were going to select the next President. François Fillon, the winner of these primaries, appeared to be the only candidate able to stop Marine Le Pen’s ascent. As we know, just a few months later Fillon was overwhelmed by the scandal concerning the fictitious alleged employment given to his wife, and his electoral prospects collapsed. Fillon remained in the game notwithstanding the opposition and embarrassment of sections of his party, and he finally obtained a result which, all things considered, was better than the expected. Yet it was the first time in history that the centre-right Gaullist party did not reach the second ballot in the presidential election. Nonetheless, the primaries’ divisiveness cannot be considered a reason for this defeat.

In any case, what happened in France is probably the worst advertisement for primary elections. It was the first time in Europe that both the centre-right and the centre-left party selected their own chief executive candidate by open primaries, and both of them spectacularly lost the election. However, far from demonstrating the danger of primary elections, this confirms the quite obvious conclusion that the electoral ‘effectiveness’ of primaries is largely linked to the political context of the moment.

Primary bonus as a multiplying effect of a competitive advantage

What has been said up to now does not clearly confirm the existence of a primary penalty (although this was shown in a few isolated cases), but it seems to deny that a primary bonus exists at all. Yet, I would not completely refuse the possible positive effects of an inclusive process of selection. For instance, it is true that I observed a sharp increase in the polls for primary winners just after their success. This is clearly an effect of his/her visibility on the media during the primary campaign. Moreover, running in primary elections seems to have contributed to update the image of leaders and candidates that otherwise would have been seen as part of the old party establishment, as was the case for long-time politicians such as Jospin, Veltroni, Hollande, and Bersani. In this respect, a ‘competitive’ candidate counting on favourable polls could take advantage of the legitimation and publicity usually associated with an inclusive process of selection to give momentum to his/her electoral campaign. Anyway, it is self-evident that primaries are not able to significantly improve the electoral performance of an ‘underdog’ candidate. Similarly, they cannot guarantee electoral success if they reward candidates confident of winning the election who then go on to conduct a weak electoral campaign (as was the case for Bersani in 2013 and partly Prodi in 2006), or else are overwhelmed by external scandals (Fillon in 2017), even if they have been selected by an overwhelming majority and by millions of people.

Instead, aspirants to the nomination appearing to have the right characteristics to become a competitive candidate are quite likely to get into office either with inclusive or more oligarchic procedures of selection. This is perfectly exemplified by the case of Tony Blair in 1994, when he succeeded in gaining the support of both party/trade union members and the parliamentary party group. In this context, the initial opposition to an (apparently) competitive electoral candidate such as Renzi by the PD establishment in the 2012 primaries represents an exception. Nonetheless, at that time the party establishment was convinced that electoral success was at hand, thus keeping the centre-left coalition united was more important than chasing the polls. Yet, in the space of a single year, just after the electoral defeat (or ‘non-success’ as Bersani defined it) in the 2013 elections, most of Renzi’s former opponents within the party had enthusiastically moved to his side, showing that in general – also in Italy, also within the party establishment – ‘electability’ tends to prevail over ‘identity’. Nonetheless, Renzi’s electoral performance in 2018 election was extremely poor.

In any event, Blair’s example contradicts the idea that the party elite is often bearer of outdated and/or radical positions that hinder the tactics of ‘modernizing’ leaders, as already pointed out by scholars such as Melchionda (Reference Melchionda2005) and Floridia (Reference Floridia2011). It is only when a ‘natural’ candidate is lacking (as has been the case for two decades within the Labour party), that party elite and grassroots preferences are more likely to split, and the latter may decide to reward an ‘extremist’ and apparently ‘unelectable’ candidate such as Corbyn, who however in the end revealed himself to be far more electorally competitive than many of the other supposedly ‘electable’ candidates included in my sample.

Concluding remarks

The issue of whether primary elections effectively help the selected candidate to win the general elections or not is still an open question. Nevertheless, the fact that more and more people are currently allowed to participate in the selection of leaders and candidates represents one of the most significant political innovations of the last few decades. Thus, according to primaries’ advocates, the spread of selection systems involving a large number of people could contribute to containing the growing dissatisfaction with politics affecting large sections of the citizenry. Actually the popularity of primaries is currently decreasing parallel to their decreasing novelty. As with every innovation there are both positive and negative aspects that still need to be fully understood, and this is the reason why this line of research is likely to have a long life. After all, the selection of the ruling class is a crucial issue for current politics, and not only for academics.

Because of the small-N problem and the impossibility of controlling for all the intervening variables, this study has not found clear answers concerning the possible relation between NP inclusiveness and electoral performance. It has, however, developed a number of indicators which could be a useful starting point for future and more widespread empirical research in the field. In fact, the recourse to more inclusive mechanisms of selection is currently increasing all over Europe due to a sort of contagion effect (Sandri et al., Reference Sandri, Seddone and Venturino2015). Accordingly, it is quite likely that in a few years’ time the sample could be significantly enlarged, both in terms of the empirical cases available with my current case selection, and possibly by adding new countries and parties to the analysis.

Nonetheless, my findings do provide a few elements (strictly interlinked) which have to be considered: they show that on the one hand incumbent candidates are more likely to win the elections; while on the other hand candidates selected by primary elections seem to be (slightly) less successful than candidates selected in other ways (or to say it better, they are more unsuccessful than candidates selected with less inclusive systems). Of course, incumbent candidates are (generally) not required to pass through a contested race to be re-appointed. On the contrary, a party usually decides to recur to primary elections or ‘primary zone’ systems because of the absence of a ‘natural’ candidate. Thus, primary elections may be an attempt to react to a leadership void, or they can be used to attempt to re-launch a party in trouble. In fact, several studies show that parties adopt primaries after an electoral defeat. On such occasions the candidate is likely to lose the election because he/she in fact starts from an disadvantage position, though of course this does not mean that primary elections cause electoral failure. Instead, they may even have improved his/her chances by providing legitimation and publicity, although the possible negative effect of a divisive NP must also be taken into account as well (unfortunately, it is impossible to have a counterfactual). In sum, other things being equal, I argue that entrusting candidate and leadership selection to a larger number of people is not necessarily a risk in electoral terms, although I decisively deny any ‘magical’ effect.

Data

The replication dataset is available at http://thedata.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/ipsr-risp

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the editors and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions.

Financial Support

This research received no grants from public, commercial, or non-profit funding agency.