The role of maintenance conceptualization diagrams in CBT

Over the last 30 years cognitive behaviour therapy has proved itself as a treatment for a wide range of conditions. Its effectiveness is in no small part due to the ease with which it can be operationalized and manualized. Successful treatment protocols have almost invariably incorporated a model of how disorders are maintained through cognitive-behavioural cycles, with guidance on how these cycles can be broken. These formulations lend themselves to representation in visual form. The first and probably most influential of these is Clark's panic cycle (Clark, Reference Clark1986). This was initially a simple spiral: anxiety leads to autonomic nervous system activation, which is misinterpreted catastrophically as a sign of impending death, serious physical danger or madness. These cognitions in turn generate more anxiety and the spiral escalates. The concept of safety seeking behaviours was later added to the model (Salkovskis, Reference Salkovskis1991). Safety behaviours are voluntary behaviours undertaken to prevent the feared catastrophe occurring. They are directly and logically connected to the physical symptom and its feared consequence e.g. sensations of breathlessness are interpreted as the onset of suffocation and lead to safety behaviours such as overbreathing, loosening clothes around the neck, and opening windows. Similar diagrammatic conceptualizations have been developed for other anxiety disorders such as obsessive compulsive disorder (Salkovskis, Reference Salkovskis1985), health anxiety (Warwick and Salkovskis, Reference Warwick, Salkovskis, Scott, Williams and Beck1989), and social phobia (Clark and Wells, Reference Clark, Wells, Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hope and Schneier1995; Wells, Reference Wells1997) and a more complex model proposed for post traumatic stress disorder (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000). Sometimes a more generic anxiety model is used (Salkovskis, Reference Salkovskis and Salkosvskis1996, p. 53; Butler, Fennell and Hackmann, Reference Butler, Fennell and Hackmann2008). This usually has the core cognitive process in anxiety (perceived threat) in the centre, and a series of cycles representing the maintenance factors around the edge. These include selective attention, worry, rumination, avoidance, reassurance seeking, and safety seeking behaviours. These vicious circles look like the petals of a flower and so the rather incongruous but memorable nickname of the “vicious flower” has been given to this model. Maintenance diagrams have also been drawn for other disorders (see for instance Westbrook, Kennerley and Kirk, Reference Westbrook, Kennerley and Kirk2007).

These diagrams form an important component of treatment and are very much in keeping with the ethos of making all aspects of therapy explicit. Maintenance diagrams serve several purposes:

1. They help the therapist and patient to collaboratively conceptualize the presenting problems.

2. They socialize the patient into the cognitive model by demonstrating links between thoughts, feelings, behaviours and physical sensations.

3. They help with distancing and decentring by presenting confusing experiences in a simple, visual form.

4. They provide a “road map” to help the therapist identify and focus on factors that are likely to be important in a particular disorder.

5. They provide a clear rationale to form the basis for future therapy interventions.

Despite the widespread use of diagrams there has been little research to date into any aspects of sharing a case conceptualization. What research there is suggests that patients have both positive and negative reactions to case conceptualization (Evans and Parry, Reference Evans and Parry1996; Chadwick, Williams and Mackenzie, Reference Chadwick, Williams and Mackenzie2003), and the conceptualization may be valued more by the therapist than the patient.

Cognitive therapy for depression could be seen as the prototype for all CBT (Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery, Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery1979), so it is surprising that a generally accepted maintenance diagram for depression has not emerged. If a figurative representation of depression is created in a therapy it is usually either the basic ABC (antecedents, beliefs, consequences) model, the Five Areas model (Wright, Williams and Garland, Reference Wright, Williams and Garland2002), or a more idiosyncratic model derived for each individual patient (Kuyken, Padesky and Dudley, Reference Kuyken, Padesky and Dudley2009). The Five Areas model is a simple comprehensive model that is very useful in demonstrating the interaction of thoughts, emotions, behaviours and physical state. Because all four components of the system are linked by arrows, the patient can see how activity in one part of the system e.g. a thought like “I am unloveable” can produce an emotion of sadness and a behavioural reaction of avoidance of people. The fifth area is the environment or external world, which impinges upon all of the other systems. This model is, however, generic and not specific to depression. It illustrates interdependence well but does not easily demonstrate maintenance cycles as effectively as the vicious circle models of anxiety. Idiosyncratic models on the other hand have the advantage of being tailored to the patient's experience patient (Kuyken et al., Reference Kuyken, Padesky and Dudley2009) but often cannot be fully derived until later in therapy when therapist and patient have got to grips with the problems at hand. There is not, then, an “off the shelf” diagram for depression that can be used early in therapy to show the vicious cycles of depression in an analogous way to the panic cycle.

Probably the most widely used visual formulation in depression is the case conceptualization diagram (Beck, Reference Beck1995). This is extremely helpful but is a developmental rather than a maintenance model. Because there is no maintenance model available novice therapists can sometimes be tempted to move to this developmental conceptualization earlier than is advisable. In their self-help book, Manage Your Mood, Veale and Wilson (Reference Veale and Wilson2007) have proposed a vicious flower for depression. It has as its central point the patient's experience of depression and then radiating from this “petals” that contain behaviours and their consequences (Veale and Wilson, Reference Veale and Wilson2007, p. 66). However, this model is described in the context of behavioural activation rather than cognitive therapy. There is therefore still scope for a cognitive-behavioural maintenance diagram for depression on similar lines to those that have proved so helpful in anxiety.

What we know about the maintenance of depression

In a recent update on cognitive therapy for depression, Kuyken, Watkins and Beck (Reference Kuyken, Watkins, Beck, Gabbard, Beck and Holmes2003) described some modifications to the original cognitive model. These are the result of empirical and theoretical developments since the original depression model was formulated. Research has indicated that negative beliefs are activated in the presence of depressed mood and most of the cognitive processing in depression – negative thoughts, beliefs and interpretations – is mood state dependent (Miranda and Persons, Reference Miranda and Persons1988; Teasdale and Cox, Reference Teasdale and Cox2001). Kuyken et al. (Reference Kuyken, Watkins, Beck, Gabbard, Beck and Holmes2003) suggest depression is maintained by a stream of “negative ruminative automatic thoughts” that are consistent with deeper cognitive structures that are activated in dysphoric mood states. These cognitive structures in turn are linked to core modes. Modes have evolutionary value and “activate programmed strategies for carrying out basic categories of survival skills, such as defence from predators, the attack and defeat of enemies, procreation and energy conservation” (Alford and Beck, Reference Alford and Beck1997, p. 27). This concept is most accessible when we think of anxiety, where the idea of a threat mode in which attention, autonomic nervous system activity, and preparedness for action are all co-ordinated in what is often referred to as the fight or flight response. While the evolutionary significance of depression is less clear, the depression mode can be imagined as an integrating construct. As Kuyken et al. describe modes:

Core modes are interlocking information processing systems that draw on the parallel processing from cognitive, affective, and sensory processing modules (Teasdale and Barnard, 1993; A. T. Beck, Reference Beck and Salkovskis1996). Once instated in depression, these core modes have a self-maintaining property as mode-consistent biases of attention, overgeneralized memories, higher-order self-schemas, ruminative thinking, and sensory feedback loops from unpleasant bodily states ‘interlock’ in self-perpetuating cycles of processing. The more often a person has suffered depression, the more easily these core modes become automatic and easily activated (Segal, Williams, Teasdale and Gemar, Reference Segal, Williams, Teasdale and Gemar1996). The content of depressive core modes tends to be organized around themes of loss, defeat, failure, worthlessness, and unloveability. (Kuyken et al., Reference Kuyken, Watkins, Beck, Gabbard, Beck and Holmes2003, p. 113)

The idea of a mode as an organizing principle can give us the centre of our vicious flower for depression. This is in essence the pervasive negative view of the self, world and future first described by Beck (Reference Beck1976). There will be a tendency to process all information in a negative way, and so when we become depressed we believe things about ourselves we would never believe when well. But there will also be self-schemas in the mode that are very personal to ourselves: these are our negative core beliefs that may be niggling doubts or fears about our worth, ability or acceptability when we are euthymic, but become certainties when we are depressed. Life events that touch upon the rawness of these core beliefs can activate the depression mode. And when the depression mode is active it has as its cognitive centre these negative core beliefs.

The petals of the flower will be the maintenance processes that arise from the mode and tend to keep the mode active. The cognitive processes known to operate in depression have already been mentioned. They are overgeneralized memories (see Williams et al., Reference Williams, Barnhofer, Crane, Herman, Raes, Watkins and Dalgleish2007), self-schemas, and ruminative thinking (Grassia and Gibb, Reference Grassia and Gibb2008). Sensory feedback from bodily states is another maintenance factor in depression. An additional process that is receiving increased attention is the self-attacking or self-bullying seen in depression and other disorders (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2000).

Behavioural inactivity has always been a focus of CBT for depression, particularly in the early stages of therapy. The success of behavioural activation as a stand alone treatment for depression (Jacobson, Martell and Dimidjian, Reference Jacobson, Martell and Dimidjian2001; Hopko, Lejuez, Ruggiero and Eifert, Reference Hopko, Lejuez, Ruggiero and Eifert2003) has led to renewed interest in behavioural factors, particularly the role of avoidance – behavioural, interpersonal, and affective. Within the behavioural activation model, avoidance is not only passive, but includes behaviours such as rumination and reassurance seeking.

Creating a maintenance model for depression

Taking these theoretical concepts and empirical findings as a starting point, a vicious (or sad!) flower was developed for depression. In its centre is the depressive mode – the state in which the organism is primed to expect it will fail to achieve goals or obtain rewards. As we have seen, in Beck's model this mode integrates the processing of affective, somatic, behavioural, cognitive and memory systems. The first model contained seven cycles. Six of these were based on the research findings described in the previous section: negative beliefs, negative interpretations, ruminations, affective state, somatic state, and behavioural avoidance. Memory bias was excluded as a separate cycle because it is not usually a significant focus in therapy and could potentially be included under the heading of negative interpretation. Given the importance of behaviours such as self-harm, substance misuse, and maladaptive interpersonal behaviours in maintaining depression, a cycle of “unhelpful behaviour” was added.

This “seven cycle” model was presented to nine students and supervisors on the Trinity College Dublin Post Graduate Diploma in CBT attending a workshop given by the author. Overall the group members were enthusiastic about the approach and recognized the need for a maintenance model for depression. There was some confusion over the relationship between this model and the Five Areas model, or “hot cross bun”, and the Beck Case Conceptualization Diagram. It was therefore decided that the model needed to be simpler and its relationship to the Five Areas model more clearly explained, so that therapists who were used to utilizing the more generic model could see how the two might be used together in the same therapy. The separate negative beliefs cycle was dropped, with the understanding that these might fit more easily in a developmental rather than maintenance conceptualization.

Description of the Six Cycles maintenance model for depression

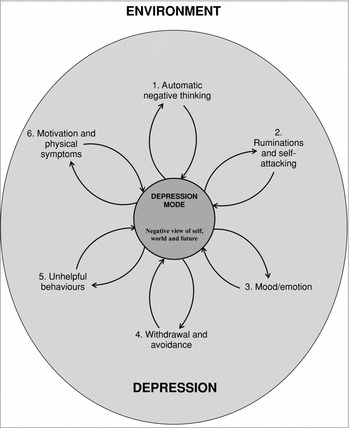

In this section the various elements of the maintenance model are described: the central depression mode, the six maintenance cycles, and the environmental context (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The 6 Cycles Maintenance Model

The six maintenance cycles can be seen as an expansion of the “hot cross bun”. There are two cognitive cycles (automatic negative thinking, and rumination/self attacking). There is a mood/emotion cycle. There are two behavioural cycles (withdrawal/avoidance, and unhelpful behaviour). Finally, there is a physical state cycle (motivation/physical state).

The different elements of the model are described with some suggestions for how they might be introduced to patients. Not all six cycles will necessarily be relevant for every person, but this in itself provides useful information; the therapist should not try to force the patient into the diagram in a Procrustean manner! The cycles also do not operate in isolation from one another. It needs to be understood that, just as with the vicious flower for anxiety, this is a simplification. All the elements can interact. Sometimes it can be helpful to show how one element leads on to another. For instance, you might get invited to a party but detect some hesitation in the voice of the person inviting you. You think “They don't really want me to come” (Automatic negative thinking). You then spend time dwelling on this thinking: “What have I done wrong?” “They don't want me. I have no social skills” (Rumination and self-attacking). This worsens your depression (Mood). You then just stay indoors all day (Withdrawal and avoidance) and perhaps drink a bottle of wine (Unhelpful behaviour), which makes you feel tired and unwell (Physical state). Each of these factors reinforces the depression itself but they also have an effect on each other.

The depression mode

Patients may relate to the concept of the depression mode more readily than the therapist, particularly if they have recurrent depression with euthymic periods between episodes. We have found that patients are very aware of how their whole mind and body changes when they become depressed. The concept may be more difficult for patients with dysthymia or chronic depression to understand because their negative thinking is more “ego-syntonic”.

The mode can be introduced with a discussion of how depression affects the whole person: the way we feel, think, behave and even the way our body works. At the centre of this is a sense of life being emptied of pleasure and satisfaction. We feel helpless and hopeless and become preoccupied with ideas of loss, defeat and worthlessness. When the depression mode is active there is a shift, or bias, in our thinking that makes the glass always appear half empty. The list of cognitive distortions may be introduced at this point and the patient asked if any of these apply when he or she is depressed. The discussion of the depression mode as the driving force behind the depressive syndrome can end with the therapist suggesting that when we are in this state we can get trapped in vicious circles that keep us depressed. This leads on to a consideration of the individual maintenance cycles.

Beliefs are not given a separate cycle in this model, but can easily be included within the centre of the flower. So, core beliefs about the self, the world, others and the future will be a significant component of the depression mode when it is activated. Assumptions can be seen as the driving force behind the maintenance cycles e.g. “If I can please people they may not reject me” can be seen as a conditional belief that leads to the unhelpful behaviour of placation. The important consideration is that the mode may contain beliefs but is a broader construct than cognition alone. The mode integrates cognitive, behavioural, affective, motivational, and physical schemas.

Automatic negative thinking

This cycle serves to demonstrate how the pervasive negative bias in depression operates in specific situations. Material from thought diaries can be used to illustrate how situations that would normally be neutral or pleasant are seen in a negative light. Specific instances of cognitive distortions leading to misinterpretations of situations can be discussed under this heading. Automatic thoughts are seen as examples of negative interpretations generating spontaneous thoughts or images in a given situation. Through Socratic questioning the patient can begin to see how negative thinking deepens low mood and further reinforces depression.

Ruminations and self-attacking

The automatic negative thinking cycle refers to spontaneous biased interpretations of events. There are also processes in depression that are more conscious and controlled and get switched on by an interpretation of an event. When something bad happens, the depressed person does not let go of a negative event, but goes over it trying to work out how or why it happened, what he or she should have done differently, what has gone wrong. Rumination about recent events, or memories from the distant past, can be noted as part of this cycle. We can also make depression worse by constantly criticizing ourselves for what went wrong or who we are as a person, and Gilbert's concept of self-attacking can be discussed under this heading if relevant.

Mood and emotions

Low mood is a typical symptom of depression and is usually expressed as a subjective feeling of sadness or emptiness of feeling. In recurrent depression, dysphoric mood states are more likely to activate the core depressive mode in a negative feedback loop. These moods can also be part of a vicious circle of “depression about depression” when we beat ourselves up for no longer being cheerful or good company. The depressive syndrome is also associated with other emotions such as anxiety and irritability that can be included in this section.

Withdrawal and avoidance

Behavioural avoidance may well be one of the most significant maintenance factors in depression. When we are in the depressed mode our belief that we cannot get pleasure or success leads us to do less of the things we used to enjoy. Our negative thoughts tell us we will fail, be criticized or be disappointed. As a result we withdraw from being with people, put off doing things or give up on them completely. We may even end up staying in bed all day. These seem solutions to painful feelings at the time, but the result is that we never get the chance to test if our negative beliefs are true. We also reduce our chances of finding any pleasure or achievement when we are inactive.

Unhelpful behaviours

Because behavioural inactivity is so important in depression it has been separated from other behaviours, which are now under the heading of “unhelpful behaviours”. Sometimes they are schema consistent i.e. behaviours in keeping with the person's negative beliefs, such as expressing self-deprecating statements, depriving oneself of pleasure, moaning about the state of the world. Often they are compensatory strategies (Beck, Reference Beck1995): attempts to manage unpleasant feelings or to compensate for negative beliefs. For instance, drinking, substance misuse, comfort eating, or self-harm may all be attempts to escape from negative feelings. Pleasing others or reassurance seeking may be ways to make ourselves acceptable. These strategies appear helpful in the short term, but in the long term make matters worse.

Motivation and physical symptoms

Depression shuts down the whole system. It may be helpful to include loss of motivation and drive and anhedonia under the heading of biological aspects of depression. Physical symptoms of depression include insomnia, loss of appetite, tiredness, reduced libido, and psychomotor retardation. These lock the depressed person even more into the depression mode. They can also be interpreted as signs of inadequacy rather than as symptoms of depression. Thus reinforcing cycles are set up: e.g. tiredness leads to less activity, which generates thoughts such as “I'm lazy” and further worsens depression, which leads to more fatigue.

Environment

It is important not to divorce these vicious circles from the depressed person's life as a whole. Work, family, friends, where we live may all contribute to depression.

External events and environmental factors may trigger the depression mode and play an important role in maintaining depression. This often happens because they are viewed through the lens of helplessness and hopelessness, and so the person gets stuck in pessimistic interpretations, loss of confidence in problem solving, ruminations and avoidance. The constraints of the environment may also make it harder to break out of depressive cycles. Critical partners reinforce low self-esteem and self-attacking; social isolation and lack of social support limits opportunities for getting positive feedback and validation; disability may limit the opportunities for behavioural activation; physical illness may worsen fatigue.

Testing the model

The Six Cycles model was presented to a group of 22 students attending the Institute of Psychiatry Postgraduate Diploma in CBT as part of a seminar on conceptualizing complex cases. These students were all trainee IAPT therapists. They were divided into pairs. One student was asked to role play a depressed patient with whom they had recently worked, while the other was instructed to role play a therapist using the model to construct a collaborative case conceptualization. After the role play they gave written feedback and answered the three questions about the experience (rating on a 4-point Likert scale: not at all, a little, a moderate amount, very useful). The results are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. “Therapist” and “Patient” ratings of usefulness of 6 cycles model

Two students commented positively on the depression mode (“Really liked saying depression mode – feels very accessible”) though one person felt the mode was difficult to explain. A number mentioned that the maintenance model had advantages over the hot cross bun (“Feels easier to link developmental factors into maintenance (than with hot cross bun).” “Helpful in putting all the pieces together as a whole as opposed to one specific example.”) Two commented on its value for treatment planning (“Very useful in terms of identifying areas to intervene.” “Gave indication of how I would lead intervention from there.”)

Suggestions for how to use the model in clinical practice

This model is potentially useful in any depressive state that has been present long enough for maintenance processes to take hold, but may be especially applicable to chronic, residual and recurrent depression. In a standard course of cognitive behavioural treatment of depression the Six Cycles model can be introduced during the early stages of treatment. It can be used to follow on from the generic Five Areas model (hot cross bun), or used instead of this model. While the Five Areas model is very helpful in deconstructing responses to particular situations, the Six Cycles model can give an overview of maintenance factors operating across a range of situations. It can do this without the need to explore a developmental conceptualization too early. The model can be introduced within the first two or three sessions when the patient is being socialized into the cognitive approach. It may be helpful to have done one or two “hot cross buns” to show the link between thoughts, feelings, behaviour and physical state. Then, as the target problems and goals are being identified, the six cycles can be used as a framework to explore how certain thoughts, feelings, behaviours and physical symptoms might be recurring across various situations. As the students found in their role play, the vicious flower helps to make sense of the confusing symptoms and experiences of depression and helps the patient decentre, becoming aware that these are indeed symptoms and not personal flaws. It also highlights which maintenance factors are important for this particular person, and may suggest targets for treatment. From here, the therapist may move on to constructing a more individualized maintenance model or a more longitudinal/developmental conceptualization.

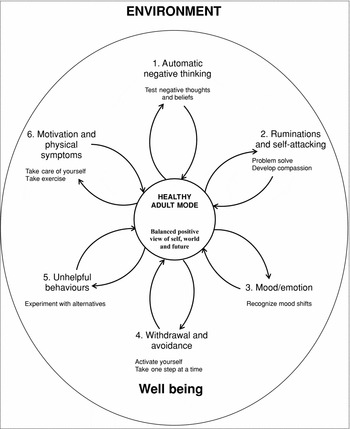

The model may have a useful role in relapse prevention work because someone with recurrent depression who is well will usually engage with the idea of the depression mode. The cycles that get activated quickly when the person becomes depressed can be recognized and an action plan for how to deal with them developed. Figure 2 outlines a “virtuous flower” with the “healthy adult mode” at its centre. It includes some suggestions for actions such as problem solving and compassionate thoughts and behaviours that can generate positive cycles.

Figure 2. Breaking out of vicious circles in depression

Summary

The Six Cycles model is a “vicious” or “sad” flower for depression based on current knowledge of the processes and maintenance factors in depression. It is an expansion of the Five Areas model. In a visual form, environmental context encloses the syndrome of depression. Depression comprises two cognitive cycles (automatic negative thinking and rumination/self-attacking), two behavioural cycles (withdrawal/avoidance and unhelpful behaviour), a mood cycle, and a motivation/physical symptoms cycle. Like similar maintenance diagrams for anxiety, the Six Cycles model may be helpful in conceptualization, socialization and treatment planning.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the students from Postgraduate Diplomas in CBT (Trinity College, Dublin and Institute of Psychiatry, London) for their very generous co-operation and constructive suggestions in the development of this model. Sheena Liness and Suzanne Byrne made helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper. This work has been supported by the Biomedical Research Centre, Institute of Psychiatry.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.