How often parents engage in shared book-reading with their preschool-age children is estimated to account for approximately 8% of the variance in children's oral language, emergent literacy, and later reading skills (Bus, Van Ijzendoorn, & Pellegrini, Reference Bus, Van Ijzendoorn and Pellegrini1995). Given that variability in children's language skills predicts school readiness, later language, literacy, and academic outcomes (NICHD, 2005; Rowe, Raudenbush, & Goldin-Meadow, Reference Rowe, Raudenbush and Goldin-Meadow2012; Walker, Greenwood, Hart, & Carta, Reference Walker, Greenwood, Hart and Carta1994), shared book-reading is considered an important tool for promoting preschool children's language skills (Dickinson, Griffith, Golinkoff, & Hirsh-Pasek, Reference Dickinson, Griffith, Golinkoff and Hirsh-Pasek2012.). Importantly, the quality of shared book-reading, as indexed by the presence of caregiver verbal interactions beyond simply reading the print in books, has been posited as a key mechanism though which shared book-reading influences language development (Fletcher & Reese, Reference Fletcher and Reese2005). A recent study showed that, although reading frequency in preschool predicted children's vocabulary outcomes at the end of the preschool year, only caregiver extra-textual talk predicted both language and literacy outcomes at the end of the preschool year and in kindergarten (Zucker, Cabell, Justice, Pentimonti, & Kaderavek, Reference Zucker, Cabell, Justice, Pentimonti and Kaderavek2013). One reason for this is that, although frequent shared book-reading exposes children to a potentially rich linguistic input (e.g., Cameron-Faulkner & Noble, Reference Cameron-Faulkner and Noble2013; Demir-Lira, Applebaum, Goldin-Meadow, & Levine, Reference Demir-Lira, Applebaum, Goldin-Meadow and Levine2019; Montag, Jones, & Smith, Reference Montag, Jones and Smith2015), caregiver extra-textual talk has the potential to support children's understanding and participation in discourse about the book in a way that is tailored to the child's current abilities. Other strong evidence for the role of caregiver extra-textual talk in children's language development comes from a meta-analysis of experimental shared book-reading studies, which found that interactive reading (i.e., where caregivers were trained to engage in extra-textual discussions about the book), as compared to non-interactive reading, had stronger benefits for toddlers and preschool-age children's vocabulary development (Mol, Bus, de Jong, & Smeets, Reference Mol, Bus, de Jong and Smeets2008). Thus, the benefits of shared book-reading for young children's language learning are greater when caregivers engage in extra-textual talk and support children's verbal participation in discussions about the book.

As children enter the preschool years, extra-textual talk that is linguistically rich and cognitively challenging becomes particularly beneficial for language learning. Specifically, abstract talk (also known as decontextualised, inferential, analytic, high demand, cognitively challenging, and non-immediate talk) has been shown to benefit preschoolers’ language skills. In shared book-reading, abstract talk involves linking the story to the child's life, inferences, predictions, and explanations, which move the conversation beyond what is perceptually available in the book. By contrast, concrete talk (also known as contextualised, literal, low demand, and immediate talk) often involves labelling and describing pictures (Sorsby & Martlew, Reference Sorsby and Martlew1991). In a recent study, Hindman, Connor, Jewkes, and Morrison (Reference Hindman, Connor, Jewkes and Morrison2008) found that both caregiver and child ‘decontextualised’ talk during shared reading at the start of the preschool year predicted children's expressive vocabulary scores at the end of the year, whereas ‘contextualised’ talk was negatively related to children's expressive vocabulary. Similarly, Dickinson and Porche (Reference Dickinson and Porche2011) found that teachers’ ‘analytic talk’ during shared book-reading in low-income preschool classrooms predicted children's receptive vocabulary into the fourth grade. More broadly, a relatively large body of research shows that caregiver speech that engages children in challenging, decontextualised conversations (e.g., talk about the past or future, and talk involving explanations) in different everyday contexts supports preschool-age children's vocabulary, syntax, and narrative development (e.g., Demir, Rowe, Heller, Goldin-Meadow, & Levine, Reference Demir, Rowe, Heller, Goldin-Meadow and Levine2015; DeTemple, Reference DeTemple, Dickinson and Tabors2001; Dickinson & Smith, Reference Dickinson and Smith1994; Hindman et al., Reference Hindman, Connor, Jewkes and Morrison2008; Peterson & McCabe, Reference Peterson and McCabe1994; Rowe, Reference Rowe2012).

The above reviewed research findings have motivated the design of language-boosting interventions, where caregivers are trained to engage their preschool-age children in rich and abstract conversations, both during shared book-reading (e.g., Morgan & Goldstein, Reference Morgan and Goldstein2004) and, more recently, in other everyday contexts (Leech, Wei, Harring, & Rowe, Reference Leech, Wei, Harring and Rowe2018). Separately, those interested in the benefits of shared book-reading for language development have called for research on the role of book genre in the quality of caregiver extra-textual talk (e.g., Aram, Reference Aram2008; Fletcher & Reese, Reference Fletcher and Reese2005). To date, the main focus of this work has been on the amount and quality of caregiver extra-textual talk when sharing informational books versus stories. A consistent finding here is that, when sharing informational books as compared to stories, caregivers have been shown to adopt a more ‘tutorial’ style, involving more extra-textual talk, more questions, and a greater level of abstract language use with their preschool- and school-aged children (e.g., Anderson, Anderson, Lynch, & Shapiro, Reference Anderson, Anderson, Lynch and Shapiro2004; Potter & Haynes, Reference Potter and Haynes2000; Price, van Kleeck, & Huberty, Reference Price, van Kleeck and Huberty2009; Torr & Clugston, Reference Torr and Clugston1999; but see Nyhout & O'Neill, Reference Nyhout and O'Neill2013, for a conflicting finding with toddlers). Likewise, perhaps reflecting the greater degree of abstraction, informational books have also been found to facilitate extra-textual talk that is linguistically richer, as indexed by lexical diversity and syntactic complexity (Price et al., Reference Price, van Kleeck and Huberty2009), which, in the broader literature on child-directed speech, has been found to predict preschool-age children's language development (see Hoff, Reference Hoff2006, for a review). Thus, informational books are recommended as a special tool for supporting preschool- and school-aged children's language and literacy development (Yopp & Yopp, Reference Yopp and Yopp2006).

Less is known about the role of stories, and of different kinds of stories, in promoting beneficial kinds of extra-textual talk for children's language and literacy development. This is problematic because stories are the predominant genre found in nurseries and at home for preschool-age children (e.g., Yopp & Yopp, Reference Yopp and Yopp2006). Furthermore, many shared book-reading interventions, such as the well-known dialogic reading approach (Whitehurst et al., Reference Whitehurst, Falco, Lonigan, Fischel, DeBaryshe, Valdez-Menchaca and Caulfield1988), have used stories as the intervention context. There are a number of reasons to think that the story genre in general may promote beneficial extra-textual talk. For example, it may promote more ‘story-specific’ caregiver discourse about characters’ states and actions than informational books (Nyhout & O'Neill, Reference Nyhout and O'Neill2013, Reference Nyhout and O'Neill2014). However, the kinds of stories to which children may be exposed can vary greatly (e.g., Wagner, Reference Wagner2013). For example, some contain more text than others, some have manipulative features and contain rhyming text, and all have content that is less or more challenging for preschoolers to understand. Importantly, a small body of recent work on the role of specific characteristics of stories has shown that not all types of story picture-books are equal in their ability to facilitate caregiver extra-textual talk (e.g., Greenhoot, Beyer, & Curtis, Reference Greenhoot, Beyer and Curtis2014; Muhinyi & Hesketh, Reference Muhinyi and Hesketh2017). For example, stories with less text (versus those with more text) may facilitate more extra-textual talk per minute (Muhinyi & Hesketh, Reference Muhinyi and Hesketh2017), and those with illustrations (versus no illustrations) may facilitate more interactive readings (Greenhoot et al., Reference Greenhoot, Beyer and Curtis2014). Of interest in the present study are story characteristics that might promote linguistically rich and abstract caregiver extra-textual talk and, importantly, caregiver verbalisations that support preschool children's verbal participation in such discourse.

One story characteristic that might encourage beneficial caregiver extra-textual talk when sharing books with preschoolers is the complexity of the story (Fletcher & Reese, Reference Fletcher and Reese2005). In line with social interactionist theory (e.g., Vygotsky, Reference Vygotsky1978), sharing a more complex story (i.e., one with content that is more challenging for preschoolers to understand) might encourage rich caregiver extra-textual talk, as the caregiver seeks to support the child's understanding about challenging aspects of the story through discussion. By contrast, when sharing a simple story, fewer and less demanding caregiver verbalisations are expected, as less support is needed to facilitate the child's understanding of the story. The present study investigates the hypothesis that more complex stories will facilitate more beneficial caregiver extra-textual talk with preschoolers.

In the present study, a more complex story is defined as one with content that is more challenging for preschoolers to understand, and thus is likely to encourage parents to produce more (and more complex) language. Stories containing a false belief are considered particularly complex because preschool-age children show difficulties in understanding false belief, both as measured in experimental tasks (Wellman, Cross, & Watson, Reference Wellman, Cross and Watson2001) and as they occur in picture-books (Riggio & Cassidy, Reference Riggio and Cassidy2009). Thus, it follows that caregivers will need to spend more time mediating the story to the child, using linguistically richer and more abstract language to achieve this (e.g., providing explanations or predictions about a character's behaviours or actions based on their belief in contrast to reality). To date, books containing a false belief have been studied as a context for maternal mental-state talk and children's theory of mind development (e.g., Adrián, Clemente, & Villanueva, Reference Adrián, Clemente and Villanueva2007; Adrián, Clemente, Villanueva, & Rieffe, Reference Adrián, Clemente, Villanueva and Rieffe2005; Peskin & Astington, Reference Peskin and Astington2004). However, to our knowledge, no previous study has investigated the amount and quality of caregiver extra-textual talk afforded by these stories as compared to their less complex counterparts (i.e., similar picture-books containing no false belief).

The present study

The present study investigated the influence of story complexity on the amount and quality of caregiver extra-textual talk during shared reading with preschool-age children. Fifty-three caregiver–child dyads (3;00–4;11) were visited once at home and video-recorded sharing a complex story (i.e., containing a false belief central to the plot) and an ostensibly similar story (i.e., containing no false belief). We matched the stories on several salient characteristics (e.g., length of the story, style of the narrative and pictures, gender of the main protagonist, whether protagonists were humans or animals) so that effects observed could be attributed to the variable of interest as opposed to these features of the stories. The quality of caregiver extra-textual talk was coded for linguistic richness and level of abstraction, as in previous book genre comparison studies. In addition, caregiver extra-textual talk was coded for questions and elaborative follow-ups on children's responses to questions (e.g., hints and requests for more information). Thus, the coding aimed to capture both the linguistic and cognitive demands of the extra-textual talk, as well as the degree to which caregivers scaffolded children's verbal participation in challenging discussions about the plot. The main study hypothesis was that complex stories would facilitate more and higher-quality caregiver extra-textual talk. Based on previous research, we also hypothesised that there would be great variability across caregivers in their extra-textual talk, but that there would be some consistency in individuals’ reading styles across genres. Possible interactions of genre with child age and socioeconomic status (SES) were tested, although no specific hypotheses were made about these. In addition, we investigated whether children asked more challenging questions (e.g., why and how questions) when sharing the complex books, as such questions could serve as a mechanism in the provision of linguistically rich and abstract caregiver extra-textual talk when sharing these books.

The specific research questions were:

RQ1. How much variation exists in the amount and quality of extra-textual talk within and across mothers?

RQ2. Do complex books facilitate more and higher-quality extra-textual talk?

RQ3. Do complex books facilitate more child questions requiring caregiver explanations (e.g., why and how questions)?

Method

Participants

Fifty-six children and their primary caregivers (all mothers) participated in this study. Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Manchester Research Ethics Committee (Ref. 16003). Participants from the Greater Manchester area (UK) were recruited via flyers distributed in nurseries, children's centres, and community spaces, and advertisements placed on relevant websites from April to November 2016. All participants provided informed consent. Data collection was incomplete for three participants (the child refused to share one or both books). Thus the final sample included 53 dyads. Caregiver SES was indexed by postcode using the Education Skills and Training Deprivation deciles of the English Indices of Multiple Deprivation (IMD, 2015), which is a national measure of neighbourhood SES based on indicators from seven domains (income, housing, employment, health, crime, education, and access to services). Participants lived in areas ranging from the most to the least deprived (see Table 1). Children were typically developing, monolingual English-speaking (22 boys and 31 girls) with no developmental or hearing disorder that could affect language development. This was confirmed by parent report as per the study inclusion criteria. Children ranged in age from 3;00 to 4;11 (M = 45.7 months, SD = 6.4 months) and their vocabulary raw scores ranged from 21 to 80 (M = 49.7, SD = 12.2), as measured by the British Picture Vocabulary Scale (BPVS-II; Dunn, Dunn, Whetton, & Burley, Reference Dunn, Dunn, Whetton and Burley1997). Standard scores on the BPVS ranged from 84 to 138 (M = 112.0, SD = 11.4), indicating that children had language abilities ranging from low-average to above-average. Forty-three of the children were White, six Mixed-race, two Asian, and two Black. Forty-three mothers (81%) had at least an undergraduate degree or equivalent, five (9%) had at least A-levels (equivalent to a high-school diploma in the US, usually obtained between 16 and 18 years of age and used as the basis of university entrance for undergraduate studies), three (6%) had at least five GCSEs (a general educational development credential, usually obtained at the end of the period of obligatory education between 14 and 16 years of age), and two (4%) had less than five GCSEs. English was reported as the only home language. Most mothers reported that their children were read to frequently at home (see Table 1). Each participant received a gift of a children's book and £10 as compensation for their time.

Table 1. Home reading frequency and socioeconomic status

Notes. N = 53. IMD = Indices of Multiple Deprivation (Education, Skills, and Training Deprivation deciles; 10 = least deprived). Percentages may not equal 100 because of rounding.

Materials

Story complexity was operationalised by the inferential demands of the story. Complex books involved a false belief central to the plot, which we predicted would elicit more conversation from the mother. By contrast, simple books involved no instances of false belief. Simple and complex books were identified and selected from high-street bookstores and libraries by the first author on the basis of previous work classifying children's picture-books by their theory of mind content (Cassidy et al., Reference Cassidy, Ball, Rourke, Werner, Feeny, Chu and Perkins1998). Four narrative picture-books were used (all published post 2000): two simple and two complex. These books were chosen as they were considered by the study authors to be representative of contemporary titles, and were as closely matched as possible to avoid effects of potentially confounding variables. Specifically, all four books contained text and colourful and vivid illustrations on every page, and were similar in their physical dimensions (paperback format, size, and length in pages and words). The books were gender neutral in their topics (i.e., they were not stereotypically considered suitable for girls or boys specifically) and were appropriate for three- and four-year-olds (publishers’ recommended age: 3–6 years), and were amended (pages and words removed as necessary) so that they were identical in length. Consequently, each book contained 22 pages and 310 words (on average 14 words per page). In all four stories, characters were animals and the main protagonist was male. All four stories were in the third person and each contained instances of direct speech. Table 2 shows an analysis of text complexity across the four picture-book stories.

Table 2. Text complexity by title

Notes. The relatively high number of multiclause utterances in Stop monkeying around was affected by the use of one particular construction (the gerund clause from the story title “Stop monkeying around”), which occurred several times in the story.

Simple books

Stop Monkeying Around (Christine Swift, 2013; published by Cupcake Books, London) is about a monkey who was bored. He tried to play with a sequence of other animals in the jungle, but only succeeded in annoying them. Eventually, he unexpectedly found another monkey, and they played together happily. The Polar Bear Paddle (David Bedford, 2009; published by QED Publishing, London) is about a polar bear who wanted to swim in the sea, but could only paddle. He observed various different creatures, and tried to copy them. In the end, he could still only paddle, but the other animals were impressed by it, and he taught them his technique. Although these books did not contain false belief, both contained references to characters’ mental states (e.g., mental-state verbs such as ‘think’, ‘like’, and ‘want’, and adjectives such as ‘sad’).

Complex books

In Pond Goose (Caroline Jayne Church, 2004; published by Oxford University Press, Oxford), a goose (the protagonist) deceived a fox by camouflaging his feathers against the hillside so that the fox could not see him. The fox falsely believed that the goose was not there. In Don't Cry Sly Fox (Henriette Barkow, 2002; published by Mantra Lingua, London), the protagonist, Sly the fox, and his friend, a hen, deceived Sly's mother by making a chicken from vegetables and fruit. Sly's mother falsely believed that the pretend chicken was real. The false belief was not explicitly stated in the text in either story, but was evident in characters’ behaviours as depicted by the illustrations and text. In both books, the false belief occurred when the protagonist deceived another character.

Procedure and transcription

On a single visit to participants’ homes, the researcher (the first author) explained that the purpose of the study was to investigate “how parents and children read different books together”, because “reading books with children may help their language development, such as their talking and understanding”. Demographic information was collected using a questionnaire. The researcher then played the Pop up Pirate game with the child in a familiarisation session, before conducting the language assessment. After this, the mother–child dyad was videoed sharing two of four possible books (one simple and one complex). All mothers confirmed that they and their children were unfamiliar with the specified books before the video-recording. The order in which books were read was counterbalanced across dyads to control for order effects (e.g., loss of interest). All dyads confirmed that they were unfamiliar with the books. Dyads were video-recorded as they read the books using a small digital camcorder (Samsung VP-MX20/ZEU) placed unobtrusively on a tripod approximately 2 m from the dyad at a 45° angle. The zoom function was used to capture the interaction more closely. The dyad was asked to sit in a place where they were comfortable or would normally read together, and the mother was instructed to “look at the two books with your child as you normally would”. If a television was on, the mother was asked to turn it off beforehand. During the video-recording, the researcher sat away from the dyad and scored a language assessment.

Video-recordings were transcribed by the researcher in CHAT format (from the CHILDES programs; MacWhinney, Reference MacWhinney2012). Two transcripts (.cha files) were created for each participant: one for each book shared. Transcription started when the mother opened the book and began to read or engage in book-related talk, and ended when they closed the book and/or their book-related talk ended. Real names (places or people) used by participants during the recordings were replaced by pseudonyms. Unintelligible words were transcribed as ‘xxx’ or phonetically transcribed if sounds were clearly distinguishable. Non-verbal behaviours (e.g., gazing, pointing, page turning) were transcribed where relevant to aid coding. Utterance boundaries were defined as outlined by Ratner and Brundage (Reference Ratner and Brundage2013), when two or more of the following cues were present: silence for two seconds or longer, terminal intonation, or a complete syntactic unit or pragmatically complete contribution (e.g., mother: “what's that?”; child: “a lizard”). Repetitions of the same word (e.g., “no no no”, “she runs very very very fast”) and rote counting (e.g. “one, two three, four”) were transcribed as single words. Character names (e.g., “Little Red”, “Little Monkey”, “Sly Fox”) were transcribed as single words (e.g., “Little_red”).

Measures

Word tokens

The amount of extra-textual talk during shared reading was indexed by the number of word tokens (i.e., the total number of words including repetitions of the same word). Number of word tokens was computed in the CLAN program (Computerized Language ANalysis).

Linguistic richness

Two measures of linguistic richness were also used: syntactic complexity and lexical diversity. Syntactic complexity was indexed by the mean length of utterances in words (MLUw), which is a measure of global structural complexity. Lexical diversity was indexed by the number of unique words (types). Both are widely used measures in previous research. Both were computed in CLAN.

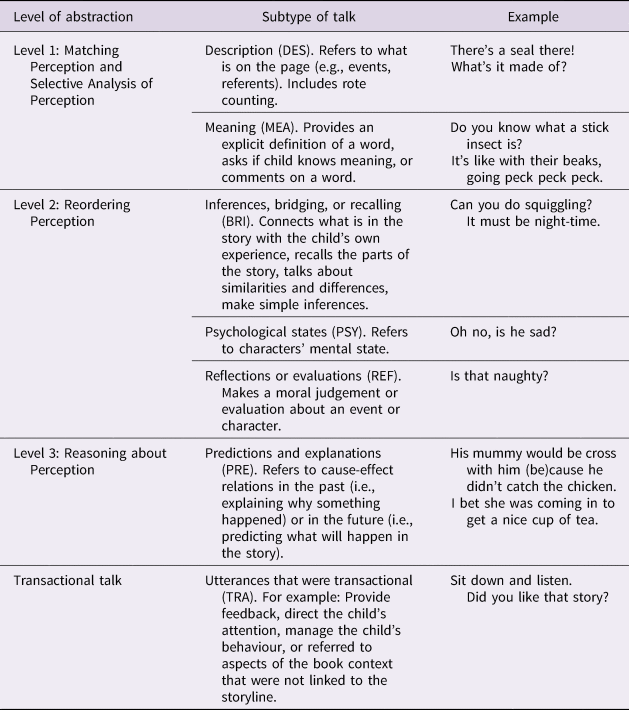

Level of abstraction

All maternal extra-textual utterances (i.e., beyond reading of the book text) were coded for level of abstraction according to the coding scheme in Table 3. This coding scheme was based on Coding Categories for Levels of Abstraction during book-reading (Price et al., Reference Price, van Kleeck and Huberty2009). Utterances that were not linked to the plot but related to the context or the child's behaviour were coded as transactional (Sorsby & Martlew, Reference Sorsby and Martlew1991). If an utterance contained elements from more than one category (e.g., an explanation might involve a lower-level inference), the higher level was coded. The level of abstraction was defined as the proportion of talk that was not bound to the here and now (i.e., utterances at Level 2 and Level 3), relative to the total amount of extra-textual talk. This index of abstraction corresponds to that used in previous work to index the level of ‘decontextualised’ talk across contexts while controlling for the total amount of talk (e.g., Rowe, Reference Rowe2012). To ensure reliability for abstract language coding, 20% of the transcripts were coded by a second coder. Disagreements were discussed and resolved after an initial transcript. Coding agreement for the level of abstraction was 79%. Weighted kappa (ĸ) with corrections made for chance was .76, indicating excellent reliability (Fleiss, Reference Fleiss1981).

Table 3. Coding scheme for maternal level of abstraction

Note. Coding scheme based on the Coding Categories for Levels of Abstraction (Price et al., Reference Price, van Kleeck and Huberty2009).

Number of questions

The number of questions was computed in CLAN by identifying all maternal utterances ending in a question mark. The output list was then hand-checked. All question types were counted.

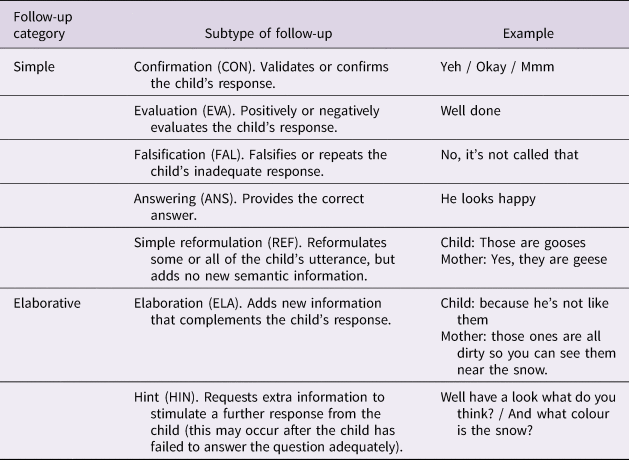

Elaborative follow-ups

Children's responses to maternal questions were identified and marked in CLAN. Maternal utterances that followed up on the child's response to a question were then identified in CLAN, and hand-coded as simple or elaborative (see Table 4 for examples). This coding scheme was based on work by Mehan (Reference Mehan1979) on the structure of social interaction in classrooms, and on more recent work on read-aloud interactions (Mascareño, Snow, Deunk, & Bosker, Reference Mascareño, Snow, Deunk and Bosker2016). The coding scheme provided an index of the degree to which caregivers followed up on their children's responses to questions, thus creating a collaborative interaction about topics in the story. Simple follow-ups were those that evaluated or provided basic feedback on the child's response (e.g., “okay”, “yes”), whereas elaborative follow-ups extended the child's response by asking for or providing more information on the same topic. If the mother followed up a child response with a simple and an elaborative follow-up (i.e., in the same turn), the follow-up was coded as elaborative. The degree of elaboration was calculated by dividing the number of elaborative follow-ups by the total number of follow-ups (i.e., both simple and elaborative). This index provided a measure of the extent to which caregiver verbalisations supported child-involved extended discussions. To ensure reliability for degree of elaboration, 20% of the transcripts were coded by a second coder. Disagreements were discussed and resolved after an initial transcript. Coding agreement for the degree of elaboration was 87.5%. Kappa (ĸ) with corrections made for chance was .76, indicating excellent reliability (Fleiss, Reference Fleiss1981).

Table 4. Coding scheme for maternal follow-ups

Note. Table adapted and modified from Mascareno et al. (Reference Mascareño, Snow, Deunk and Bosker2016).

Child questions

Children's challenging questions were defined as those that required an explanation from the caregiver (e.g., how and why questions, such as “why did he want to do that?”). Challenging questions were identified by using the kwal function in CLAN to identify all child questions (i.e., utterances ending in a question mark). Hits were hand-searched and coded.

Child language abilities

The British Picture Vocabulary Test 2nd edition (BPVS-II; Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Dunn, Whetton and Burley1997) was used to measure children's receptive vocabulary skill. This assessment involves the examiner saying a word, and the child pointing to the corresponding picture from a set of four on a page. The assessment comprises two practice trials and 14 sets of pictures each containing 12 test items (a total of 168 test items). Testing begins at the set indicated in the manual for the child's age (usually their basal level), and ends when the child reaches their ceiling level (eight or more errors in a set). Raw scores are calculated and converted to standardized (UK-normed) scores and percentile ranks. Administration time was approximately 10–15 minutes. One child had a missing BPVS score because she did not complete the language assessment. This score was replaced by the sample mean, as it was considered missing at random, i.e., the reason for missingness was unrelated to the child's probable language score given that the incomplete score was already in the typical range. The BPVS was selected for its ease of administration.

Statistical approach

Linear mixed-effects models (LMMs) were used to assess the main research question about the effects of story type on maternal and child speech. This approach has several advantages over t-tests or mixed factorial ANOVA in addressing the present research questions. Mixed modelling allows us to assess the effect of story type on each of the maternal outcomes while also accounting for variation across specific book titles by allowing the intercept to vary across book titles. This approach also eliminates the need to dichotomise continuous variables when testing for interactions among continuous variables (i.e., in this case IMD scores, BPVS scores, and child age) and the experimental factor (i.e., in this case story type). Unlike traditional regression, LMMs account for non-independent observations (i.e., dyads sharing both kinds of book in the present study) by modelling between- and within-subject variation separately (Raudenbush & Bryk, Reference Raudenbush and Bryk2002). For each dependent variable, an initial LMM was fitted with the random effects structure (varying intercepts for dyad and book title), and the fixed factors of story type, child age, and IMD scores. The random effects structure consisted of dyad and book title as random factors to account for variation within dyads and across specific book titles by allowing intercepts to vary across dyads and book titles. Initial multiple regression analyses were used to check for multicollinearity among variables and the presence of univariate and multivariate outliers, and residuals were plotted against fitted values to check for normality and homogeneity (Raudenbush & Bryk, Reference Raudenbush and Bryk2002). Then LMMs were fitted to assess the effect of story type on each of the maternal and child speech variables. To explore possible two-way interactions of child age, BPVS scores, and IMD scores with book type, subsequent models were fitted in a step-down manner (i.e., with and then without the interaction term), and Likelihood Ratio Tests (LRTs) were used to compare the model with and without the interaction term. In testing interactions, variables were first scaled and centred to aid interpretation. Models with interaction terms that did not significantly increase model fit were rejected. Models were fitted in R (version 3.5.2) using the lmer function of package lme4 version 1.1–19 (Bates, Mächler, Bolker, & Walker, Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015). The traditional alpha value cut-off was used (p < .05). We report t-values for each model, as well as p-values as obtained using the car package (Fox & Weisberg, Reference Fox and Weisberg2011). Residuals were plotted against fitted values to check for normality and homogeneity (Raudenbush & Bryk, Reference Raudenbush and Bryk2002).

Models were run on proportional measures for level of abstraction, questions, and the degree of elaborativeness, indexing quality while also controlling for the quantity extra-textual talk (i.e., showing whether the composition of mothers’ extra-textual talk was of greater quality, as opposed to reflecting whether mothers simply produced more speech overall). The results for raw frequencies are also presented. However, inferential statistics on the raw frequencies for these measures are presented only when the pattern of results differed.

Results

Descriptive statistics

All mothers produced extra-textual talk when sharing both the simple and complex books. Reading durations (seconds) were similar for the simple and complex books (M = 255 s, SD = 75, range = 135–472, and M = 257 s, SD = 84, range = 140–552, respectively). Table 5 shows descriptive statistics and Spearman's correlations for the book-reading variables of interest. Both frequencies and proportions are presented for the amount of abstract talk and elaborative follow-ups. The proportional measures control for differences in the amount of maternal talk, providing an index of the quality of mothers’ extra-textual talk. As such, proportions are used in the subsequent analyses (and separate results for frequencies are presented only where they differed from the proportional results).

Table 5. Descriptive statistics (proportions in parenthesis) and Spearman's correlations for maternal extra-textual talk variables across story contexts

Notes. N = 53. MLUw = mean length of utterance in words. Proportion of abstract utterances was relative to the total number of utterances. Proportion of elaborative follow-ups was relative to the total number of follow-ups (this measure was calculated for n = 38, as the denominator was the total number of follow-ups rather than the total number of utterances);

* = p < .05, ** = p < .01 (two-tailed).

Variation in the amount and quality of extra-textual talk

As shown in Table 5, large standard deviations and ranges indicated large variability in the different aspects of maternal speech across mothers. Mothers’ word tokens during shared reading of both book types were positively skewed, indicating that the majority of mothers did not produce the number of word tokens at the higher end of the ranges in Table 5. As shown in Table 5, Spearman's correlations showed positive associations for the maternal speech variables of interest across the two story types (ρs = .238–.801), with the exception of the proportion of elaborative follow-ups (ρ = –.069). This indicates strong consistency in mothers’ individual reading styles in general. The lack of a relation for elaborative follow-ups across book types could reflect the relatively low frequency of elaborative follow-ups in the simple condition, or it could suggest that the use of elaborative follow-ups serves a different function depending on book type. Specifically, elaborative follow-ups could function to support children's participation in extended discussions involving explanations when sharing the complex book, but not in the simple book, where such discourse is extremely rare (see Table 5).

Before addressing the next research question, we explored possible sources of the variation in extra-textual talk by examining relations between the demographic variables (i.e., child age, child BPVS scores, and maternal SES) and the extra-textual talk variables across the two story types. As shown in Table 6, mothers tended to use less extra-textual talk with older children across book types. However, mothers asked more questions to children with more advanced language skills on average when sharing the complex books. Maternal SES (as indexed by IMD scores) tended to be positively related to all of the extra-textual talk measures (although it was only significantly related to MLUw and abstract talk in the simple book and MLUw in the complex book), indicating that on average mothers of higher SES tended to engage in more and higher-quality extra-textual talk.

Table 6. Spearman's correlations (ρ) between the extra-textual talk variables and child age and IMD scores

Notes. N = 53. BPVS = British Picture Vocabulary Scale (standardized scores presented). IMD = Indices of Multiple Deprivation (Education, Skills, and Training Deprivation deciles; 10 = least deprived). * = p < .05, ** = p < .001 (two-tailed).

Effect of story type on the amount and quality of extra-textual talk

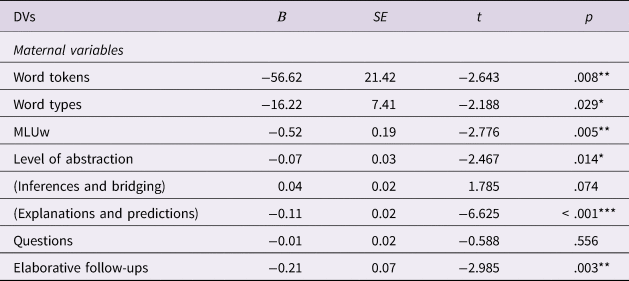

Table 7 shows the LMMs for effect of the type of story on each maternal speech variable. As shown in Table 7, the complex stories as compared to the simple ones facilitated a significantly greater number of word tokens and word types, significantly longer MLUw, and a significantly greater proportion of abstract utterances and elaborative follow-ups, but not questions. Accounting for variation across book titles and controlling for maternal SES and child age, mothers produced on average 57 more word tokens, 16 more word types, 7% more abstract talk, and 21% more elaborative follow-ups (relative to simple follow-ups) on child responses, and MLUw that was 0.5 words longer when sharing the complex stories as compared to the simple stories. Thus, on average mothers used more extra-textual talk and had a greater quality of extra-textual talk when sharing the complex book as compared to the simple book, as indexed by each of the variables of interest excluding questions. Note that when the model was run on the raw frequency measures, the number of questions mothers posed was significantly greater when sharing the complex stories (as compared to the simple stories) (B = –3.72, SE = 1.35, t = –2.755, p = .006), perhaps reflecting the greater overall amount of talk when sharing the complex stories. This was the only result that differed depending on whether the raw or proportional data were used.

Table 7. Estimated fixed-effects coefficients, t-values, and p-values from the LMMs predicting maternal extra-textual talk from book type

Notes. N = 53. LMM = linear mixed-effects model. DVs = dependent variables. MLUw = Mean length of utterances in words. All LMMs controlled for maternal SES and child age by including these as additional fixed factors. Random effects structures for each model consist of random intercepts for dyad and book title. Interactions between story type and each demographic variable (child age, child language abilities, and SES) were assessed by using Likelihood Ratio Test (LRT) procedures, but these are not presented as none were significant. * = p < .05, ** = p < .01, *** = p < .001.

Next, we explored whether caregivers’ greater level of abstraction in the complex books reflected a general increase in abstract talk or was driven by one particular level of abstract talk. Table 7 shows the LMM for the effect of story on lower level abstract talk (i.e., inferences and bridging) and higher-level abstract talk (i.e., explanations and predictions). As shown in Table 7, LMMs indicated that complex stories facilitated a greater proportion of higher-level abstract talk (i.e., predictions and explanations), but not lower-level abstract talk (i.e., inferences and bridging). Accounting for variation across book titles, mothers produced on average 11% more talk involving explanations and predictions when sharing the complex as compared to the simple stories. Thus, the increased level of abstraction was driven by extra-textual talk involving predictions and explanations.

Finally, we explored possible interactions of child age, BPVS scores, and SES with book type using LRT tests (as described above). There were no significant interactions of book type with age, BPVS scores, or SES for any of the maternal extra-textual talk variables.

Effect of story type on child questions requiring caregiver explanations

Only four children posed challenging questions when sharing the simple book, and eleven children posed challenging questions when sharing the complex book. The same children who posed challenging questions when sharing the simple books also posed them when sharing the complex books. Among the subset of children who asked questions when sharing either book (n = 11), the mean number of challenging questions posed when sharing the simple vs. the complex books was 0.82 (SD = 1.54, range = 0–5) and 2.3 (SD = 1.62, range = 1–6), respectively. These descriptive data show that the complex stories tended to facilitate more challenging questions from some children, but that these occurred very rarely in the sample. Inferential statistics were not used to address this question given the small number of children who posed challenging questions.

Discussion

It is well established that caregiver extra-textual talk during shared book-reading is beneficial for preschool-age children's language development. However, knowledge is lacking about the role of different book characteristics in promoting caregiver extra-textual talk. Here, we investigated the amount and quality of caregiver extra-textual talk as facilitated by stories that differed in their complexity. Complex stories were defined as those containing a false belief central to the plot, whereas simple stories had no false belief. Fifty-three mothers and their three- and four-year-old children shared both a simple and a complex story. To support the interpretation and generalizability of the results, (1) books were used that were commercially available and thus representative of those likely to be encountered by preschoolers, and (2) books were matched on key characteristics so that they were ostensibly very similar. Results from the linear mixed-effects models showed that the complex books encouraged more and higher-quality caregiver extra-textual talk, as hypothesised. Specifically, the complex books facilitated more extra-textual talk, more syntactically complex and lexically diverse extra-textual talk, and a greater level of abstraction (driven by explanations and predictions). In addition, although on average mothers posed similar proportions of questions when sharing simple and complex books, they elaborated more on children's responses to questions when sharing the complex books. Importantly, these effects on caregiver extra-textual talk were robust across mothers and book titles, despite great variability among individual mothers in their reading styles.

The present findings lend support to the hypothesis that complex stories, as compared to their simpler counterparts, provide increased opportunities for challenging and beneficial caregiver extra-textual talk with preschoolers (Fletcher & Reese, Reference Fletcher and Reese2005). We used books with a false belief central to the story to represent complex stories in the present study, as such stories are known to be challenging for preschool-age children. As hypothesised, these books encouraged caregiver extra-textual talk that was linguistically richer and more abstract. Interestingly, the greater level of abstraction and linguistic complexity in caregiver extra-textual talk when sharing the complex stories was driven by extra-textual talk at the highest level of abstraction (i.e., explanations and predictions). This higher level of abstraction was accompanied by a more elaborative style, where the caregiver followed up on children's responses to questions, scaffolding their verbal participation in discussions about the plot. The finding of this more elaborative style and the presence of explanatory utterances with the complex books is consistent with previous research on how challenging, explanatory discourse with preschoolers unfolds as part of a sequence characterised by elaborations on children's responses during shared book-reading and in other contexts (Gosen, Berenst, & de Glopper, Reference Gosen, Berenst and de Glopper2013; Snow & Kurland, Reference Snow, Kurland and Hicks1996). Although ostensibly similar to the complex stories, the simple stories in our study provided only limited opportunities for such extra-textual talk. Importantly, children's exposure to the kinds of co-constructed abstract discourse that we observed with the complex books in our study has been found to predict language development (e.g., Dickinson & Porche, Reference Dickinson and Porche2011; Dickinson & Smith, Reference Dickinson and Smith1994). Thus, complex stories as conceptualised in this study may be a particularly beneficial context for language learning.

These findings add to a significant body of work investigating the role of the book in caregiver extra-textual talk. Previous research on the role of the book on extra-textual talk has focused largely on informational books vs. stories, finding that informational books facilitate more abstract language use than stories (e.g., Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Anderson, Lynch and Shapiro2004; Potter & Haynes, Reference Potter and Haynes2000; Price et al., Reference Price, van Kleeck and Huberty2009; Torr & Clugston, Reference Torr and Clugston1999). One possible reason for this consistent finding is that caregivers are biased towards using a more tutorial style by the genre of the book (i.e., informational books may be seen as intended for teaching the child). However, the results presented here suggest that, even when books do not explicitly bias caregivers to use a more tutorial style, caregivers may increase the complexity of their extra-textual talk to reflect the demands of the content of the book in line with their children's developing abilities. Interestingly, we did not observe interactions between book type and child age or abilities in the present study. One interpretation of this is that the caregivers in this study were skilled at supporting children's participation in the more demanding discourse about the complex story in ways appropriate given the specific child. Support for this interpretation comes from the finding that mothers' extra-textual talk when sharing the complex books was characterised by the use of elaborative follow-ups (i.e., which build on and thus are individualised and sensitive to children's contributions).

A key implication of the present study is the importance of choosing stories in the light of children's developing abilities. As shown in our study, stories can be carefully selected to promote caregiver extra-textual talk that supports children's verbal participation in extended discussions about the plot (e.g., involving reasoning about characters’ motivations). Based on the present study findings, it is recommended that stories be selected with consideration of the kinds of opportunities they afford for extra-textual talk, as different kinds of stories will offer different opportunities for children's learning depending on the age of the child. In the preschool years, children benefit from more challenging interactions, such as those involving explanatory discourse (Rowe, Reference Rowe2012). Therefore, complex books, such as those containing a false belief, are likely to be particularly beneficial in the preschool years, and may serve to prepare them for the extended discourse that will be encountered in the classroom. As well as selecting books based on the opportunities they afford for beneficial extra-textual talk, it is also important to consider the child's own preferences. Letting the child choose the book for sharing may promote their engagement during shared book-reading (Ortiz, Stowe, & Arnold, Reference Ortiz, Stowe and Arnold2001), which, in turn, could encourage more meaningful and beneficial extra-textual discussions about the book (e.g., Malin, Cabrera, & Rowe, Reference Malin, Cabrera and Rowe2014).

The choice of story is an especially important consideration for those conducting shared book-reading interventions. Complex stories, as defined in our study, may be particularly useful in shared book-reading interventions targeting preschool children's language skills through training caregivers to engage in rich and abstract discussions about the story (e.g., Morgan & Goldstein, Reference Morgan and Goldstein2004). By contrast, younger children, or those with language delays (who may not be developmentally ready for the more challenging kinds of discussions surrounding false-belief books), may benefit more from the less demanding extra-textual talk associated with simple stories. In addition to the complexity of the story, those designing shared book-reading interventions for younger children should consider other book characteristics. For example, a recent study showed that simple (i.e., non false-belief) stories with low amounts of text were particularly useful at promoting high rates of extra-textual talk with three-year-olds, as compared to their higher text, simple (i.e., also non false-belief) counterparts (Muhinyi & Hesketh, Reference Muhinyi and Hesketh2017). Thus, these kinds of stories may be appropriate for younger children and those with lower language skills.

In the light of these recommendations, the provision of resources in low-SES populations is also important. Recently, children's book access has been linked to linguistic and cognitive outcomes in children at developmental risk because of low SES (Baydar et al., Reference Baydar, Küntay, Yagmurlu, Aydemir, Cankaya, Göksen and Cemalcilar2014; Farver, Xu, Lonigan, & Eppe, Reference Farver, Xu, Lonigan and Eppe2013; Lugo-Gil & Tamis-LeMonda, Reference Lugo-Gil and Tamis-LeMonda2008). Thus, the provision of a wide repertoire of books should increase opportunities for preschool-age children's exposure to those books that are likely to be developmentally appropriate and promote optimal caregiver extra-textual talk to support language development.

A second key implication of this study is the need for interventions that teach caregivers both the importance of using abstract language during shared reading with preschool-age children, and importantly, how to engage children in discussions involving abstract talk. Importantly, when engaging children in more abstract discussions, some of the mothers in our study used questions and elaborative follow-ups, which build on the child's response and extend the conversation. However, consistent with previous research (e.g., Muhinyi & Hesketh, Reference Muhinyi and Hesketh2017; Nyhout & O'Niell, Reference Nyhout and O'Neill2013; Price et al., Reference Price, van Kleeck and Huberty2009), there was wide variation in mothers’ reading styles, and some mothers missed opportunities to engage their children in abstract conversations, even when sharing the complex stories. Parent-focused intervention studies may need to provide specific training on how to involve children in abstract talk through questioning and following up on children's responses in ways that extend the discussion. This is likely to be more beneficial than simply commenting or posing challenging questions which the child is not ready to answer without support.

More broadly, the findings of this study contribute to our understanding of the influence of context on caregiver–child interaction. Context-related differences have been explored across broad domains, such as mealtimes, book-reading, and toy play (Hoff, Reference Hoff2006). Adding to a growing body of work investigating the influence of specific characteristics within given contexts (e.g., different types of toys and books), the present study highlights the importance of micro-level features of the context in child-directed speech. Such micro-level analyses of context contribute to our understanding of how particular contexts may relate to children's language development, having implications both for practice and transactional theories of development (Sameroff, Reference Sameroff2009). Future work is needed to explore whether other kinds of stories that could be considered challenging for preschool-age children might also facilitate higher quality extra-textual talk. We do not yet know if all stories that are more complex in terms of their content will facilitate more and richer extra-textual talk with preschoolers, or if our findings are specific to false-belief vs. non-false-belief stories as examined here (or specific to stories requiring greater inferential understanding). For example, stories containing a scientific concept central to the plot (e.g., measurement or weight) may also facilitate more abstract talk from caregivers in terms of explanations and predictions, as in the present study. Such stories might also facilitate a greater proportion of lower-level abstract talk (not observed in the present study), such as discussions connecting the story to the child's own experiences involving a given concept.

There are several limitations to the present study, and some clear directions for future work. First, although relatively large, our sample was fairly homogenous in terms of several characteristics (i.e., reading frequency, desire to participate in research, and level of child engagement). Thus, it could be important for future research to examine the role of story subgenre in a more diverse sample, including one with greater variation in SES, reading frequency, and children's engagement/interest in book-reading. One way of achieving this might be to observe naturalistic shared book-reading in preschool classrooms across the SES continuum.

Second, we used a small pool of books in the present study (two stories that contained a false belief, and two that did not). Both of the complex stories had a false belief that was central to the plot, and in both books the false belief was depicted through the behaviours of the protagonists (as depicted in the pictures and described in the text), rather than being explicitly stated in the text. Future research should consider different variations of false-belief stories, and whether manipulating specific features of the stories (e.g., whether or not the false belief is explicitly stated in the text, and/or the text complexity of the stories) affects the extra-textual talk. One possibility is that stories where the false belief is explicitly stated in the text would not yield the same degree of challenging extra-textual talk as observed in the present study, because caregivers may perceive less of a need to explore children's understanding of complex aspects of the plot in extra-textual discussions when it is stated in the text.

Finally, we did not examine possible effects of genre on children's contributions in this study. This was because we would expect that effects of book complexity on children's contributions would be more evident in later readings, reflecting the influence of caregiver scaffolding on the false-belief book-reading on children's skills over time, in line with social interactionist theory (e.g., Peterson & McCabe, Reference Peterson and McCabe1994). Future research should investigate the role of book genre and complexity on children's productions over time (e.g., across repeated readings), and on children's subsequent language development.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate the role of story complexity on caregiver extra-textual talk. We found that stories that were more complex in terms of their content (i.e., contained a false belief) encouraged more abstract and linguistically complex extra-textual talk, as well as a more elaborative conversational style. Thus, the choice of story matters for those seeking to promote preschool children's language learning through shared book-reading.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by an Economic and Social Research Council studentship awarded to Amber Muhinyi (grant number ES/J500094/1). Caroline Rowland is supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (grant number ES/L008955/1). We thank the participating families for their time and willingness to take part, and Leone Buckle and Maxine Winstanley for help in transcription and coding. Declarations of interest: none.