Introduction

The relationship between nationalism and architecture has been one of Turkish architectural historiography’s most challenging topics in the twentieth century. The challenge begins with the discursive terms “Islamic,” “Ottoman,” and “Turkish,” which have often been used interchangeably within art and architectural discourse. This confusion is partly due to the dominance of Orientalist art historiography, which mostly ignores regional and chronological differences. This article traces the usage of these terms by considering several art history texts published in the nineteenth and early twentieth century to demonstrate how the intelligentsia in the late Ottoman Empire and early Turkish Republic initially tried to identify their cultural artifacts. It was initiated by establishing an indigenous Ottoman architectural theory different from other Muslim countries, which became more nuanced over the decades with the coining of the term “Turkish architecture.” The dismantling of the term “Ottomanism” was not only a subtle change in terminology but also a significant shift in the intellectual milieu in early twentieth-century context.

The emergence and broader use of Turkish art and architecture as a term in the discipline of art history, and the conceptualization and production of national architecture in Turkey happened almost concurrently. An examination of the early use of Turkish national art in art historiography in place of more reductive Islamic art concepts may reveal why and to what extent this terminology was preferred. Turkish architectural historiography developed in German-speaking universities with art history toolkits and borrowed themes from archeology, philosophy, and architecture. The foundation of “Turkish art” as a subject of academic inquiry is attributed to the Vienna School of Art History led by Josef Strzygowski (1862–1941) and his students Heinrich Glück (1889–1930) and Ernst Diez (1878–1961). Influenced by Hegel’s theory of aesthetics, they believed art expresses the spirit of the culture in which it is created (Gaiger Reference Gaiger2011, 178–194; Houlgate Reference Houlgate and Zalta2020; Pancaroğlu Reference Pancaroğlu2007, 67–68). Therefore, they sought to find a “national” essence in different art forms and advanced the idea of a continuous evolution of Turkish art from Central Asia to Anatolia (Pancaroğlu Reference Pancaroğlu2007, 68, 71). It was Glück who coined the term “Turkish Art” in 1917 to distinguish a Turkish essence from those of other Islamic arts. Later, Diez wrote an extensive monography on Turkish art in 1946, and his assistant, Oktay Aslanapa (1914–2013), translated it into Turkish and republished it with revisions in 1955, before writing his own extensive survey, Turkish Art and Architecture, mainly for international readership, in 1971 (Aslanapa Reference Aslanapa1971).

The Viennese School influenced local Turkish art historians, including Celâl Esâd Arseven (Kuban Reference Kuban1969, 19), who published Türk Sanatı (Turkish Art) and its French translation, L’art Turc, in 1928 and 1939, respectively. Arseven (1875–1971) identified the characteristics of Turkish architecture by referring to its stylistic differences compared to its Persian and Arabian counterparts (Bozdoğan Reference Bozdoğan2007, 203–204). For him, the purity of Turkish architecture was vulgarized, if not contaminated, by foreign influences. In this respect, he understood the empire’s final years as replete with aesthetic decadence and indifference to the rules of classical Ottoman architecture (Arseven Reference Arseven1984 [1928], 178–180; Aslanapa Reference Aslanapa2004 [1986], 533, 597, 608). These authors typically referred to formal aspects and the coexistence of several revivalist architectural styles before turning their attention to the subsequent transitional period that aimed to establish a national architectural style in the early twentieth century. Consequently, late-nineteenth-century architecture was often simplified, neglected, or labeled as eclectic through their modernist lens.

Later art historians stressed formal details to avoid conceptual generalizations and emphasized the difference between the eclectic, historicist character of the long nineteenth century and quests for a new architecture in the early twentieth century. They also stressed the essential role of nationalist architecture in the making of the Turkish nation. For instance, in the 1970s, Metin Sözen, in his extensive survey of Modern Turkish architecture, categorized the empire’s final years as the “First National Architecture Period.” Yıldırım Yavuz and Süha Özkan presented a similar, but more nuanced, approach in the 1980s, adopting the same terminology in the chapter “Finding National Idiom: The First National Style” (Sözen Reference Sözen1984, 27–41; Yavuz and Özkan Reference Yavuz, Özkan, Holod and Evin1984, 51–67). For these authors, the beginning of the Second Constitutional Period (1908) was a political threshold that allowed the presence of different artistic and ideological frames in the Empire, and the Turkish national architecture movement was profoundly influenced by the spread of the nationalist ideas of the period. Such historiographies present architecture as a homogenous and anonymous production, reflecting national taste through a uniform, consistent, and identical style. They represent nationalist sentiments in society as evidence of this ideological interpretation, accentuating notable Turkish architects’ designs as nationalist experiments, while neglecting their particular differences.

Other historians, like Afife Batur, began to contextualize the emergence of national architecture by referring to the social and political developments of early-twentieth-century Turkey (Batur Reference Batur1983, Reference Batur2005; Holod and Evin Reference Holod and Ahmet1984). Since the 1990s, more recent scholarship has continued to challenge the stylistic shortcomings and limited contextualization of this period, aiming, instead, to consider a more comprehensive context inclusive of the world around Turkey with reference to the role of European Romanticism in the Turkish intellectual agenda (Cephanecigil and Akın Reference Cephanecigil and Akın2010; Bozdoğan Reference Bozdoğan2001; Bozdoğan and Akcan Reference Bozdoğan and Akcan2012; Tanju Reference Tanju2005).Footnote 1 While the inclusion of social and political contexts in art history can be considered an advancement, attaching cultural changes to major political events has also come under criticism (Bozdoğan Reference Bozdoğan2001, 31). For instance, as Kononenko puts, attempts to constitute a revival had already started before 1908, and the production of several designs by Kemaleddin Bey and Vedat Bey, prominent Turkish architects of the late Ottoman period, were in use before this political threshold, suggesting it is merely “wishful thinking” to consider 1908 as the beginning of a new epoch (Kononenko Reference Kononenko2018, 375).

This article, in what follows, presents a twofold analysis of the textual and practical construction of national architecture in the late Ottoman period. First, I examine how different texts depicted Ottoman architecture’s origins in the late Ottoman period by considering the legacy of Usûl-i Mimâri-i Osmani (1873) (The Fundamentals of Ottoman Architecture, Usûl hereafter),Footnote 2 which, in recent historiographical work, has been presented as a critical intellectual threshold and the earliest comprehensive text for the construction of national architectural culture in the late Ottoman Empire. Secondly, I offer a fresh perspective on another remarkable treatise of the period, Mimari-i İslam (Islamic Architecture) by Kemaleddin Bey (1906). I hope to demonstrate how Usûl’s contemporaries and following generations interpreted the 1873 text in ways more complicated than we assume. Next, turning to the early twentieth century, I consider the remarkable intellectual shift from Ottomanism to Turkish nationalism and its coincidence with the textual description and physical construction of public buildings, attesting to the variety of personal interpretations at the intersection of modernity and locality in architectural practice.

In this way, the article asks whether the intellectuals and architects of the 1870s and Second Constitutional Period, both of whom claimed to discover, legitimize, and practice a national architecture, understood the “national” character of architecture in comparable ways or if, alternatively, national architecture served as an umbrella term sheltering different approaches. By referring to Kemaleddin Bey’s writings, this article uncovers whether or not it is possible to discuss a sense of pluralism among these intellectuals and their notions of “national architecture” and, if so, what means were employed by the later generation to distinguish themselves from their predecessors.

I conceive of Kemaleddin Bey’s role as central to the understanding of the spatial and intellectual transformation of the period not because he was among the most productive architects of the period, but because he was a leading figure in the foundation of a national Turkish architectural theory and history in his time. As will be discussed in the following pages, his appointment to the Evkâf-ı Hümâyun Nezâreti (Ministry of the Pious Endowments) was particularly significant in promoting public buildings blended with a “Turkish character” for the modernizing Turkish city. To understand his response to the question of national taste, I consider the design and construction of the Fifth Vakıf Han, a student dormitory in İstanbul, in the final part of the article. Consulting several newspaper and journal articles contemporary with the dormitory’s design and construction, I examine how the textual appraisal of this building synthesizes modernity with “national taste” during the conceptual construction of national architecture in Turkey.

The impact and legacy of Usûl-i Mimâri-i Osmani (1873)

As Göksun Akyürek has analyzed, several descriptive texts were published in periodicals in the 1860s on the history of art and architecture. Mecmua-i Fünûn (The Journal of Sciences), the periodical of the Cemiyet-i İlmiye-i Osmani (Ottoman Science Society), published a few. Embracing the Ottomanist perspective, this journal was open to all Ottoman intellectuals wishing to publish, regardless of their ethnic or religious identity (Akyürek Reference Akyürek2009, 115–116). Predating Usûl, Mecmua-i Fünûn published serials on architecture and the city, including, Târih-i Ayasofya (History of Hagia Sophia) (1864–1867) by Alexander Constantinidis and Târih-i Kostantiniye (History of Constantinople) (1866–1867) by Alexander Themistoklis Phardys. Phardys also wrote the about history of the Çemberlitaş (Column of Constantine) in 1866 (Akyürek Reference Akyürek2009, 115–116). These were descriptive, monographic narratives informing their readers about architecture in formal terms. As the list of names and titles suggests, the contributions by non-Muslim Ottomans, especially Greeks, is noteworthy (Strauss Reference Strauss1995). Beginning in 1870, Ali Efendi, the publisher of Basiret, a popular newspaper, regularly wrote about urban developments and the mayoral services in İstanbul in his column, Şehir Mektupları (City Letters). Although nonacademic, his effort as a Muslim journalist reporting on problems witnessed in the city, including the protection of architectural heritage, were significant (Basiretçi Reference Basiretçi2001).

It is important to note that the efforts to establish art historiography in Turkey also coincided with the emergence and spread of new ideas: an Ottoman nation, Ottoman citizenship, and patriotism. These concepts were disseminated by Namık Kemal and his contemporaries İbrahim Şinasi, Ali Suavi, and Ziya Pasha in different literary genres. These were clear signs of Romanticist blows to the intellectual circles of the Empire since the 1860s (Mardin Reference Mardin2000). The Ottoman intelligentsia was observing the change in the İstanbul cityscape and its impetus in daily life, but its reflection in the textual domain often did not go beyond descriptive reports in newspapers and magazines. Therefore, the critical texts on the history and theory of art, architecture, and the city did not emerge for decades, with the more critical texts being published after the 1870s.

Developed within this historical context, Usûl was a comprehensive text on the theory and history of Ottoman architecture (Ersoy Reference Ersoy2007). A synthesis of progressive, positivist determinism, and romantic, historical construction found its place in this book, reflecting the zeitgeist of the Tanzimat era. Published for the 1873 Vienna Exposition under İbrahim Edhem Pasha, the Minister of Public Works, it was a trilingual book (Turkish, French, German), written and illustrated by a group of non-Muslim Ottoman and Levantine intellectuals, including Bogos Şaşıyan, Eugène Maillard, Marie de Launay, and Pierre Montani. The book comprises thirteen chapters and a glossary (de Launay et al Reference de Launay1873).

Usûl’s publication coincided with the spread of Romanticism, which shifted intellectual interest from the classical ages to medieval times in Europe, as medieval cities, their architecture and building techniques, and the preservation of medieval heritage were all at stake. The public interest toward history in the nineteenth century culminated in the awakening of European nations in modern terms, which resonated among the Ottoman intellectuals. Usûl’s authors utilized the text as a foundation for further research on the origins of Ottoman architecture. In academic literature, Usûl is considered a fundamental text for demonstrating the evolution of historical consciousness and the development of an evolutionary scheme for the history of Ottoman architecture (Baydar Reference Baydar2004, 22; Baydar Nalbantoğlu 1989, 60–66; Ersoy Reference Ersoy2007, 117 and Reference Ersoy2015, 4; Necipoğlu Reference Necipoğlu2007; Tanju Reference Tanju2007; Tanyeli Reference Tanyeli1990, 24; Yazıcı Reference Yazıcı2003, 12–19). Likely the earliest rhetorical text on Ottoman architecture (Durmuş and Gür Reference Durmuş and Gür2017), Usûl is supposed to have had two crucial functions: the legitimization of Ottoman architecture as a unique historical phenomenon in reaction to the claims of some Western art historians (Necipoğlu Reference Necipoğlu2007, 143) and the proposition of a linear evolution of Ottoman architecture akin to Vignola’s classical orders within Greek architecture. Usûl articulated this evolutionary scheme through scaled drawings of Ottoman buildings and their ornamentation. Referring metaphorically to biological growth, the rise of Ottoman architecture was presented as having been succeeded by decadence and decline in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

For modern historians, Usûl is an invaluable discovery. Beyond being a pioneering example of its genre in Ottoman history, it was a significant effort to communicate with the European world in cultural terms using European terminology (Ersoy Reference Ersoy2007, 117 and Reference Ersoy2015, 4). Here, the primary questions are: What was the impact of Usûl after its publication, and in what ways did it affect the Ottomans’ interpretation of their architectural trajectory? Did it promote further research on Ottoman architecture? And, finally, what was the interaction between the authors of Usûl and its readership, and did its contemporaries and the following generation emulate it or approach it with critical distance?

Following its publication there were rare attempts to evaluate the arguments of Usûl. A decade after its publication, an anonymous article published in Hamiyet, a magazine of literature and science, entitled Sanayi-i Nefîse-i Milliyemiz (Our National Fine Arts), reexamined and drew similar conclusions on Ottoman architecture to what Usûl had already proposed. As with Usûl’s methodology, the author employed a historical frame tracing the historical background of Ottoman architecture to produce a modern historical narrative in its favor. For this author, the great Ottoman architects, such as Mehmed, Hayreddin, Kasım, Kemaleddin, and Sinan, were not merely masters of their profession – they carefully examined Roman and Byzantine remnants to build up grand arches or domes, studied Arabian and Persian styles of ornamentation before synthesizing a new style, and codified the science of Ottoman architecture. However, Ottoman architecture was still understood to have gradually entered a period of decadence and decline in the hands of incapable European and non-Muslim kalfas (journeymen) (Sanayi-i Nefise 1886, 81–82).

Concerning such paradigms and the rediscovery of classical Ottoman architecture, Teracim-i Ahval: Mimar Sinan (The Biography of Sinan the Architect) is one of the earliest modern biographic examples. The author, given simply as Ahmed, was a language instructor at Gülhane Military Middle School in İstanbul. Published in Maârif, a magazine of science and literature, his article provides us with an archetypal account of this genre (Ahmed 1893). Ahmed’s text was among the earliest mythical constructions of Sinan’s image, which became increasingly popular during the early twentieth century. The mythologizing of Sinan through secondary materials set a precedent in portraying the “capable” architect. The existence of such texts demonstrates that Usûl, rather than constituting a sole, authoritative work on the Ottoman architectural tradition, opened a new channel for Ottoman intelligentsia to theorize and historicize an evolutionary scheme for Ottoman architecture. Notably, however, subsequent texts neither directly emulated nor rejected Usûl. Rather, they indicated vague positions in reference to its arguments.

Mimâri-i İslâm (Islamic Architecture)

Mimari-i İslam is a lengthy text published in 1906 by Kemaleddin Bey, a pioneering figure in early-twentieth-century Turkish architectural practice whose ascending professional career overlapped with the increasingly nationalist sentiments of the 1910s. His exploration of the basic tenets of Turkish architecture, however, went further back. Born in 1870 in İstanbul to a middle-class family, he taught and practiced architecture when the profession was largely supervised by the Levantine and non-Muslim subjects of the Empire. Following his graduation from civil engineering school in 1891, he worked for August Jasmund before going to Berlin on a state scholarship to study at Charlottenburg Technical School in 1895. After returning to İstanbul, he became acquainted with the nationalist circles of the city, and his primary concern became reinterpreting the Ottoman architectural vocabulary and applying it in public buildings. His appointment to the Sanâyi-i Nefîse Mektebi (School of Fine Arts) in 1900 and the İnşaat ve Tamirat Hey’et-i Fenniyyesi (Construction and Amendment Department) of the Ministry of Pious Endowments in 1909 played a crucial role in the realization of his architectural narrative, though earlier experiments with the refinement of Ottoman forms, as in the tombs of Gazi Osman Pasha and Ahmed Cevat Pasha (1900), can be identified (Figure 1). Kemaleddin Bey also served as the cofounder of the Osmanlı Mimar ve Mühendis Cemiyeti (Ottoman Engineers and Architects Society) in 1908. Through his buildings, writings, and educational roles, he was a leader in the architectural domain until his death in 1927 (Batur and Cephanecigil Reference Batur and Cephanecigil2009; Cengizkan Reference Cengizkan2009; Yavuz Reference Yavuz2009).

Figure 1. Tomb of Gazi Osman Pasha designed by Kemaleddin Bey (1900).

Kemaleddin Bey’s forty-five-page long architectural treatise, Mimari-i İslam, was not published in independent, booklet form, but, surprisingly, included in the 1906 salnâme (yearbook) of Bursa province (Kemaleddin 1906) – a striking detail as the format of yearbooks was strictly predefined (Duman Reference Duman2000). This occurrence may be read as a response to Usûl because its authors had shown a particular interest in the early Ottoman architecture of Bursa in their linear theory of Ottoman architecture. The editor of the yearbook clearly appreciated the significance of Bursa for the formative years of Ottoman architecture and underlined the necessity of including a text describing the distinctiveness of Bursa in architectural history in the preamble (Kemaleddin 1906, 142).

Like other chapters of the yearbook, the text includes several full-page images, mostly chosen from Bursa’s Ottoman monuments, yet there is no parallelism between the textual content and the order of the images (Figure 2). Although the title implies a comprehensive evaluation of Islamic architecture, the content is confined chiefly to Turkish-Islamic architecture in Anatolia. Significantly, what is regarded as Ottoman in Usûl’s terminology becomes Turkish in Kemaleddin Bey’s treatise. Other types of Muslim architecture (Arab and Persian) appear alongside Byzantine architecture in the text inasmuch as they are necessary to explain the Turkish context. The text’s leitmotif is familiar: constructing a progressive history of Islamic architecture and positioning Turkish architecture at the top of the aesthetical hierarchy. It can be argued that this was a response to the nineteenth-century art histories by European Orientalists, like Texier (Crane Reference Crane1972, 309–315; Necipoğlu Reference Necipoğlu2007, 143, 151). According to the author, Turkish architecture marks the highest level of achievement in the Islamic world when compared to its Persian and Arab predecessors. Upon considering Arab architecture, Kemaleddin Bey claimed that it offered nothing original in the planimetric layout and construction of buildings, though it mastered two-dimensional ornamentation. Therefore, he understood Arabs to be better decorators than they were good builders, who elegantly embellished all interiors. The Byzantines, in his estimation, however, were great builders, attaining a higher level in the theory and science of construction, calculation, distribution of building loads, and firmness of buildings. To a point, his arguments about Persian, Arab, and Byzantine architectures seem to align with an Orientalist outlook, however, Kemaleddin Bey later challenges European orientalist discourse by placing Turkish architecture above its predecessors. For him, while Turks kept Byzantine architecture’s structural and spatial principles as a guide, they enriched their buildings with authentic architectonic ornaments where necessary (Kemaleddin 1906, 143). Even though Kemaleddin Bey rejects the terms in Usûl’s trajectory of linear historical progress, for instance, he adopts the same methodology to explain Ottoman architecture in relation to its Arab, Persian, and Byzantine counterparts. Because he establishes a hierarchical order between Ottoman architecture and its other Muslim counterparts, aspects of his analysis can be read as a form of “Ottoman Orientalism” toward the non-Turkish cultures of the Muslim world. Kemaleddin Bey’s “Turkish art” assumes a mature form, synthesizing those “inferior” Arab art forms with Byzantine culture. Footnote 3

Figure 2. Two consecutive pages from Mimâri-i İslâm (1906) including Kemaleddin Bey’s treatise and a photograph of Hüdavendigar Mosque in Bursa.

Furthermore, when examining Usûl, Kemaleddin Bey fiercely challenged its content and methodology. For him, even though the graphic and technical quality of the book was to be appreciated, he found it a precarious source for architecture students because:

it is very erroneous from the point of the basic principles of fenn-i mi’mari (architectural science) and accordingly malign for the training architects. The essential part of the book entitled Tarz-ı mi’mâri-yi Osmanlının nazariyâtı (the theory of the Ottoman architectural style) and folios attached to the text should be, if possible, destroyed. (p. 183)Footnote 4

Kemaleddin Bey made further criticisms, scrutinizing Montani’s incorrect theory explaining the development of Ottoman architecture. He rejected Montani’s proposal of a linear pattern of formal development, dependent on detailed drawings inspired by the uninterrupted existence of Greek column orders in Western historiography.

The theory of basic principles introduced by Montani is almost nonsense. It is against the Ottoman style or the essence of Turkish building practices, and therefore it can be understood as a scorning of Ottoman style. The author’s vision was confined by Vignola’s Atlas of Architecture, known by any architecture student. He constituted his theory by making up a similar division of orders of columns and cornices, and then, he drew the column capitals consistent with orientalist style and, finally, gave a peculiar name for each. (p. 184)

Reflecting the pedagogical concerns of Kemaleddin Bey, who was teaching at the School of Fine Arts in the architecture department, this quotation suggests his preference for reading the evolution of Turkish architecture through architectonic terms, rather than stylistic references and accuses Montani of reducing architectural evolution to minor details of style instead of more significant spatial orders and innovations. Therefore, as Bozdoğan suggests, Kemaleddin Bey was an early advocate of reading Turkish architecture through a modernist lens who tried to reconcile Turkish architectural historiography with the rational character of modernity (2007). It seems that Kemaleddin Bey did not attack Montani in person. Instead, Montani might have represented cultural alienation for Kemaleddin Bey’s generation. For him, the effect of Montani’s historical inquiry meant unfavorable results in practice and, in fact, the inappropriate execution of recent restoration projects was attributed to his ignorant approach (Kemaleddin 1906, 184).

Importantly, and almost synchronously with the publication of Kemaleddin Bey’s treatise, was Celâl Esâd’s (Arseven) publication of a series of articles in İkdâm (Endeavor), a periodical active in 1906 and 1907, explaining the basic tenets of Islamic architecture, particularly in relation to Arab, Persian, and Ottoman architectures. In these articles, he acknowledges the significance of the former two for the development of the latter and underlines the originality of Ottoman architecture as a long-lasting architectural tradition (Esâd Reference Esâd2020a [1906]). His arguments reflect significant parallelism with Kemaleddin Bey’s, stressing similar themes, such as the emergence and rise of the Ottoman architectural tradition, the role of architect Sinan, and the decadence and decay of Ottoman architecture in the hands of foreign architects since the eighteenth century (Esâd Reference Esâd2020b [1907]).

Together, Kemaleddin Bey and Celâl Esâd would become leading figures of the Türk Ocağı (Turkish Hearth) social events during the Second Constitutional period. Despite the similarities in their arguments, though, it is essential to underline that Esâd used the term “Ottoman architecture” in contrast to Kemaleddin Bey’s insistence on “Turkish architecture.”

Considering this in light of Kemaleddin Bey’s active role as an instructor and architect, it is necessary to consider how his opinions may have been transmitted to his students and found reception in the Ministry Office or on construction sites. Furthermore, it can be argued that this generation might have coded Usûl as a typical example of cultural alienation of the Tanzimat era. Moreover, I argue that the narrative of Usûl may well have been understood as a case study in what to avoid, rather than what to aspire to for Kemaleddin Bey’s students’ generation.

There are several factual errors in the text as well. For instance, Kemaleddin Bey borrows a timeline of events of Islamic architecture from an unknown source, but he criticizes the list as incomplete – partially excluding Ottoman architecture – and erroneous – with several chronologic problems. These formal defects in the text point to a fundamental problem for the historical construction of Ottoman architecture in the late nineteenth century: limited availability of comprehensive books on Ottoman history (Akyürek Reference Akyürek2009, 117). It is important to note that, European Romanticism had already triggered the publication of several national or regional art and architectural history books after Viollet-le-Duc, whereas, in the Ottoman Empire, the original publications lagged for a considerable time. Excluding Usûl, the first comprehensive texts could arguably have been Turkish Architecture and Decoration (L’architecture et decoration turque) by Leon Parvilée (1874) and, decades later, Kemaleddin Bey and Celâl Esâd’s treatises in 1906 (Ersoy Reference Ersoy2007, 130–131).

The relative scarcity of texts on Ottoman art and architecture must have affected the educational curriculum of architects as well. Generally, Ottoman architecture was studied only in the last year of the architecture department curriculum in İstanbul (Baydar Nalbantoğlu 1989, 73). This condition must have partially changed after the appointment of Vedat Bey to the Academy of Fine Arts in 1899 and Kemaleddin Bey to the Civil Engineering School in 1900. Both figures’ presence in the architectural medium and activity in the schools were significant, and inevitably influenced the next generation of architects. As Gülsüm Baydar has pointed out, the Academy of Fine Arts’ students reacted strongly against the presence of non-Muslim instructors and their delivery of course content (Batur Reference Batur2003; Tanyeli Reference Tanyeli2007). Students demanded, “to learn Turkish architecture from Turkish instructors inspired by the Süleymaniye and the Selimiye [mosques] rather than St. Peters in Rome” (Baydar Nalbantoğlu 1989, 130). The first generation of Turkish students, who were later appointed as instructors in the academy, became role models for their students by delivering the national character of architecture. Architect Mehmet Nihat Nigizberk (1878–1945) wrote about Kemaleddin Bey’s desire to train students for years of continuous service and raise the interest in architecture (Mimar Nihat Reference Nihat1933) while another, Sedat Çetintaş (1889–1965), noted his passionate tone in Seljuk and Ottoman architectural history lectures (Cephanecigil Reference Cephanecigil2010, 80–89; Çetintaş Reference Çetintaş1944). For Vedat Bey, Kemaleddin Bey, and their students, the avoidance of Orientalist clichés about Islamic architecture was crucial (Civelek Reference Civelek2009, 137). This is reflected in Kemaleddin Bey’s writings, which expand upon the role of foreign influence in the decline of Turkish architecture. Kemaleddin Bey was an active participant in these discussions (Kemaleddin 1913a, 1913b) in publications such as Türk Yurdu. For Kemaleddin Bey, the national character of a building could be elicited through the architect’s erudition on the measurements and proportions of Ottoman architecture (Kononenko Reference Kononenko2018, 376).

The rise of new agents and ideas: Can a Turkish architectural revival be possible?

Kemaleddin Bey’s rejection of Usûl reflects a new understanding of Turkish art and architecture. The intellectual medium changed considerably in the period between the publication of Usûl and Kemaleddin Bey’s treatise. Kemaleddin Bey’s effort was an experiment in the genuine nationalist interpretation of classical art and architecture, which coincided with the birth of Turkish nationalism among the educated Ottoman elite.

Yet despite the changing cultural paradigm, it may be far-fetched to observe a mainstream Turkish architecture in material terms due to the ambiguity of terminology at the beginning of the twentieth century. Bozdoğan cautions the use of the term “national” to define the architectural culture of the 1908–1918 period. For her, Ottomanism, which was fabricated by Ottoman intellectuals, was promoted by the state as a binding agent for different ethnoreligious groups and architectural practice was still led mainly by non-Muslim architects despite the increasing number of Muslim-Turkish ones (Bozdoğan Reference Bozdoğan2001, 33). However, following the Balkan Wars and World War I, skepticism of Ottomanism emerged.

The dissemination of Kemaleddin Bey’s thoughts was triggered by the emergence and rise of new agents. Together, they served the proliferation of nationalist ideas and, consequently, pushed the rise of nationalist sentiments into the architectural realm. They prompted the production of texts on Ottoman architecture and stimulated a romantic interpretation of architecture at the turn of the century. This coincided with the graduation of the first Turkish students from the Academy and their appointment as instructors, thus increasing the commission of many public buildings that manifested their ideas. Likewise, an increasing number of journals became available for the dissemination of their thoughts. At this point, I would like to highlight the role of Ziya Gökalp and Kemaleddin Bey, who endeavored to contextualize and realize national culture, architecture, and history through their works. Compared to other arts, architecture became the most visible form of this zealous effort and the amelioration and purification of Ottoman architecture from “foreign influences” was the main issue in their official agenda.

Gökalp, a prominent figure of the cultural domain, utilized mass media and public events to disseminate his theory of culture. After arriving in İstanbul in 1912, he was elected to the Türk Ocağı (Turkish Hearth) executive committee, which pursued widespread domestic representation in line with its mission to inculcate a national culture among Turks (Tuncer et al Reference Tuncer1998). Despite its strong emphasis on Turkism, the organization intentionally kept political distance from the ruling Commitee of Union and Progess (CUP) government, even though they had similar social and cultural programs (Georgeon Reference Georgeon2006, 41; Üstel Reference Üstel1997). The society’s official publication, Türk Yurdu (Turkish Homeland), was a common platform for members to promote the society’s opinions. Many prominent figures, including Gökalp, held conferences hosted by the Turkish Hearth, on a broad spectrum of cultural topics, including national culture, Turkish history, art history, Turkish arts and crafts, and Ottoman architecture (Gümüşoğlu Reference Gümüşoğlu2003). During Ramadan in 1914 (Tuncer et al Reference Tuncer1998, 29–32) there were public seminars with titles such as “Turkish Art and Philosophy: About Mosques, Tombs, Palaces, Fountains and Houses” and “The Old İstanbul” by Celâl Esâd; “Ottoman Architecture” by Sarem Bey, the deputy director of the Fine Arts Academy; and “The Works of Our Ancestors in Bursa and Edirne” and “Ornament in Turkish Buildings: Wood and Marble Carving, and Wall and Ceiling Ornaments” by Hamdullah Suphi (Tanrıöver). As the titles of the events suggest, the aim was to build up a common understanding of the past, which was linked to the cultural building of Turkish nation (Cephanecigil and Akın Reference Cephanecigil and Akın2010, 32–33). To make public conferences more influential and visually appealing, the society acquired a remarkable collection of slides. Hamdullah Suphi, a well-known novelist and politician, used hundreds of slides in his conferences (Cephanecigil and Akın Reference Cephanecigil and Akın2010; Sarınay Reference Sarınay2005, 164). Such events must have inspired attendees to learn about Turkish history and arts. Renowned poet Ahmet Haşim describes the popularity of these events, saying:

[I]t stimulated the spread of architectural nationalism among the educated youth of İstanbul. Everyone was proud of discovering an old, unheard of architect’s name. The [journal] articles praised the significance and nobility of the old marble pieces. The poems admired the beauty of arches and columns. The literary language was full of terms borrowed from masonry and carpentry. (Akın Reference Akın and Batur2003, 32)

The romantic narrative prevailing in Ahmet Haşim’s observations signifies the radical change in the conscious appropriation of the city and its buildings in popular thought. Moreover, the novelty and poetic language emphasized here are clear indications of Romanticism. Ferit Cansever, who was among the leaders of the Turkish Hearth shared similar sentiments:

[T]he influential [speeches] stimulated our eyes to move slowly upwards and [consequently] we bowed respectfully before the architectural beauties of Süleymaniye [Mosque], Sultanahmet [Mosque], and Bayezid [Mosque]and concurrently we were proudly discovering our sense of belonging. (Cephanecigil and Akın Reference Cephanecigil and Akın2010, 33–34)

Such romantic concepts enabled the foundation of İstanbul Muhîbleri Cemiyeti (Society of İstanbul Lovers) in 1911, which aimed to protect the historical monuments, natural beauties, and indigenous urban texture of İstanbul through the creation of a collective awareness in the society (Cephanecigil and Akın Reference Cephanecigil and Akın2010, 33–34). In this context, the architectural medium in İstanbul during the war years seems similar to its European counterparts of the nineteenth century, emphasizing a solid interest in the cultural heritage inspired by Romanticism.

As these examples demonstrate, it was only around the outbreak of World War I that Ottomanism collapsed and eventually gave way to a promising Turkish nationalism, which would place the Turkish nation at the core of the Ottoman society. This inevitably necessitated the redefinition of nationhood. The texts of Kemaleddin Bey clearly develop the Turkishness of the culture as opposed to its Ottomanness. Here, the term “Turk” was no longer associated with sedentary, uneducated clans of Anatolia, but reinterpreted as a core cultural characteristic with roots going back for centuries to a great architectural heritage (Kemaleddin 1911, 1917). Turkism made use of the shared history, culture, and language of Turks (Bozdoğan Reference Bozdoğan2001, 35) and consequently, the young Turkish architects whom Kemaleddin Bey and Vedat Bey trained, rejected Orientalism and other European revivalisms in favor of classical Ottoman architecture forms (Bozdoğan Reference Bozdoğan2001, 35).

Of course, the romantic appropriation of nationalism theorized by Ziya Gökalp and his companions required material testing grounds: new buildings for modern functions with a national architectural taste. In other words, the challenge was to demonstrate how to spatially reconcile culture (Turkish architecture) with civilization (modern functions). Such buildings would be crucial to assert that Turkish architecture was neither dead nor ahistorical. Instead, Ziya Gökalp and his colleagues endeavored to prove that Turkish architecture was also contemporary and could adopt a state-of-the-art construction technology. The following section examines one such testing ground and its popular reception in printed media: Kemaleddin Bey’s Fifth Vakıf Han.

The spatial manifestation of the ideal synthesis: A student dormitory project in İstanbul

A critical turning point enabled Kemaleddin Bey to practice his architectural discourse when in 1909 he was appointed as the head of the Construction and Repair Department of the Ministry of Endowment following its reorganization. This marked what is typically referred to as the most productive period (1909–1919) of his professional career (Yavuz Reference Yavuz1981, 62–63). During these years, he founded a team of designers and builders and initiated the repair and restoration of many religious buildings in İstanbul. Designing and constructing public buildings, such as mosques, schools, and revenue buildings, they also increased the endowments’ incomes and enhanced public services.

In this context, the Vakıf Han buildings are worth mentioning. They were primarily developed to meet the increasing demand for new shops, modern offices, and apartments in İstanbul’s commercial districts. Designed for construction on lots occupied by ruined pious endowments’ buildings, they were profitable investments for a ministry eager to maximize the lots’ use value (Altınyıldız Reference Altınyıldız2007; Yavuz Reference Yavuz1981, Reference Yavuz2009). Accordingly, their presence indicates an enthusiasm for new modern civic environments and represents a dramatic physical change in the city. What’s more, they demonstrate how the city absorbed modern living and working practices and incorporated them into the global capitalist economic system (Giddens Reference Giddens1991). Such remarkable changes resulted from property rights reform, urban planning, the introduction of administrative units like municipalities and municipal councils, and an increase in land prices and capital accumulation. These spatial changes were primarily observed in İstanbul’s Galata/Pera districts and spread to the rest of the city through the second half of the nineteenth century.

Among these spatial signs of change, apartment units reflected the shifting nature of family culture, blurring boundaries of public and private life, and relinquishing old codes of dwelling and their spatial characteristics (Akın Reference Akın1998; Baruh Reference Baruh2009; Öncel Reference Öncel2014). The provision of office spaces indicated the rise of a new social group: freelance professionals, commissioners, and commercial dealers, who could be considered anonymous agents of modernity in the cityscape. In addition to private entrepreneurship, meeting such spatial demands by a ministry indicates another remarkable aspect of Ottoman modernization: active participation of state agencies in the financing of public buildings and increasing of revenue (Altınyıldız Reference Altınyıldız2007, 286–287). Finally, despite emphasizing substantial historical references in the design of their façades, they were among the pioneering experiments of the current state-of-the-art construction technology and advanced several technological aspects of modernity: use of reinforced concrete and steel construction systems, modular design, modern equipment, central heating systems, and elevators (Uzun Reference Uzun2008, 58; Yavuz Reference Yavuz1976, 18).

Marking a radical change in attitude, the early years of the twentieth century witnessed opinions about the “ideal” blend of modernity and national taste to the foreground through the appraisal of new buildings (Gökalp Reference Gökalp1922; Kemaleddin 1913b). Vedat Bey’s Ministry of Post & Telegram building (1905–1909) located in Sirkeci, a central district of İstanbul that witnessed remarkable spatial transformations in the final quarter of the nineteenth century, is one work that exemplifies this development. Combining state-of-the-art technology and spatial configuration with many local (read Turkish) details it may well have encouraged Kemaleddin Bey and the Ministry to follow a similar approach in later projects.

The Vakıf Han buildings were designed in the period between 1911–1912. The first three of seven were completed before World War I, but construction of the fourth was suspended due to severe economic conditions and could only be inaugurated in 1926. Similarly, the construction of the fifth was halted, resuming only after substantial changes to the original project. The sixth and seventh were never built (Yavuz Reference Yavuz1981, 63–64). This section will analyze how the concept of Turkish architectural revival was textually elaborated and physically materialized in the building of the Fifth Vakıf Han.

While lesser known than the first four, the Fifth Vakıf Han was a popular topic in pronationalist media during its design and construction. Unlike the other revenue-generating projects, the Fifth Vakıf Han was unique in that was a charity dedicated to supporting the poor students of the city. As a dormitory, it held special significance, particularly as widening the basis of formal education was a stated goal among nationalist circles, including the CUP and Turkish Hearth (Gökalp Reference Gökalp1972, 46–47). In this context, authors celebrated the dormitory as an achievement in promoting mass education in the country, praising its symbolic significance, and highlighting its technical and functional features in detail. The Fifth Vakıf Han was intended for high school and university students requiring shelter in İstanbul (Türkan Reference Türkan2020, 160–170). A public investment funded and maintained by the Ministry of Pious Endowments, it was designed in the Construction and Repair department of the Ministry headed by Kemaleddin Bey in 1911. Inspired by the zeitgeist of the period, it sought to embody a “perfect” blend of advanced technology and materials, functional distribution of spaces, and comfort-related features.

Critical examination of different issues of Türk Yurdu (Turkish Homeland), which documented the design of the dormitory throughout 1911, enables us to address this idealized blend of culture and technology. According to one anonymous author, public and private spaces in the building would be physically separated by two distinct entrances. The public spaces would comprise a cafeteria and a canteen on the basement level and a lofty, two-story high conference room on the first floor. Hosting one of İstanbul’s largest halls, the building was praised for epitomizing the idealized mission of public education through the intensive use of this conference space after its inauguration. The private entrance, however, was designed for the exclusive use of the students and led to the administrative offices, reception hall, and telephone room on the ground floor. Additionally, a library with reading rooms and a shared worshipping space was planned. The private rooms would be located on the upper two floors, with wider (3–4 beds) and smaller (1–2 beds) rooms accommodating more than eighty students in total (Talebe Yurdu Reference Yurdu1911b, 567). Other articles emphasized the social function of the building, stating that this safe environment for the youth would support their physical and mental health while contributing to the development of their moral and religious values (Talebe Yurdu Reference Yurdu1911a, 311). Designed to be technologically advanced, it also boasted various novel comforts such as electricity, central heating, access to hot water twenty-four hours a day, and an elevator.

As for construction and ornamentation, the building was to follow Turkish building and adornment principles so that it would “be an exemplary case, showing students the benefits of the application of our architectural principles to modern buildings” (Talebe Yurdu Reference Yurdu1911b, 567).

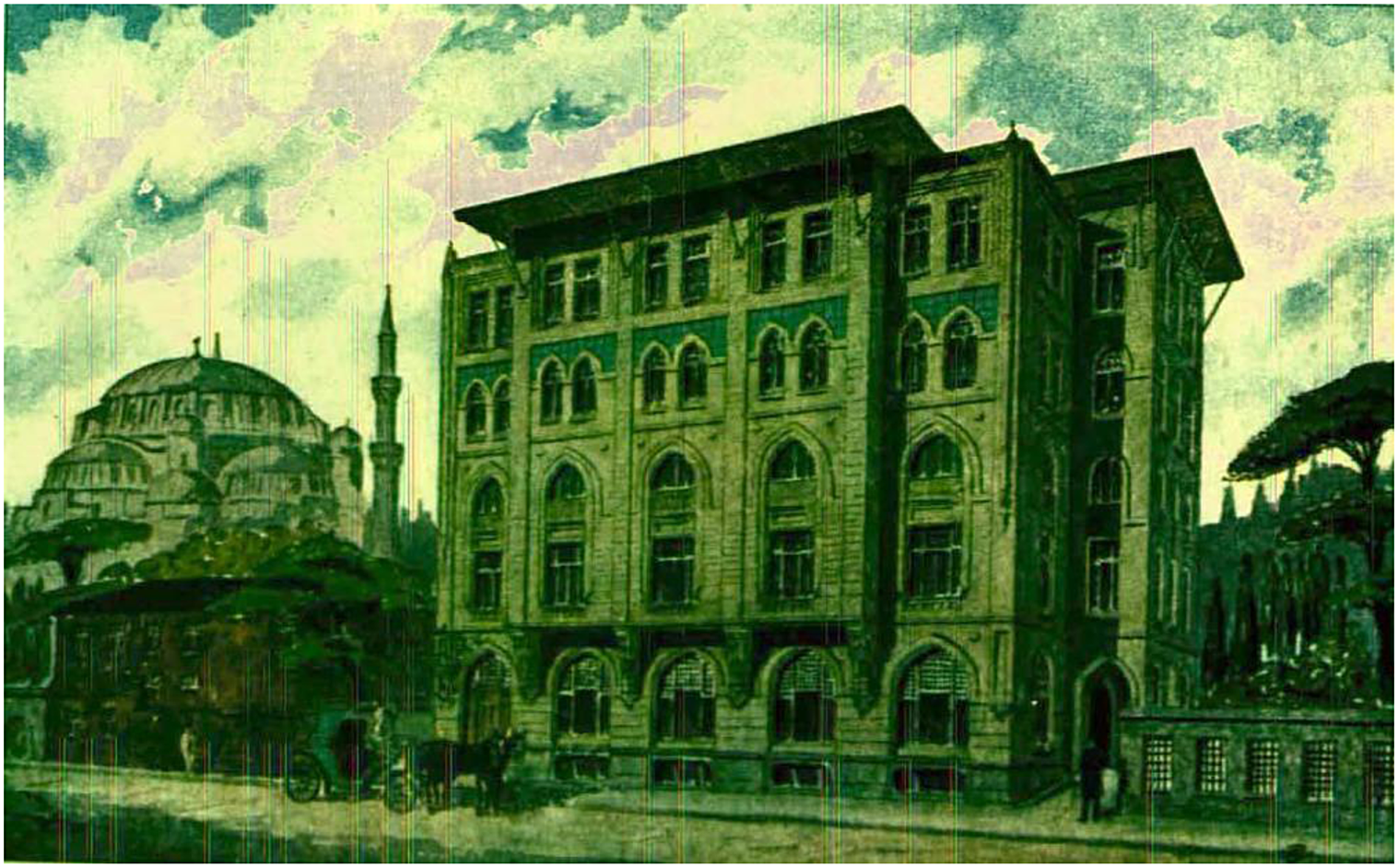

A full-page perspective image of the building was published in another issue (Figure 3), showcasing its location “in the most beautiful part of İstanbul” (Haftalık Havadis 1913, 200). Drawn by Kemaleddin Bey, the dormitory is represented from an angle that couples it with Şehzâde Mehmed Mosque (1543–1548), thus juxtaposing Kemaleddin Bey’s new design with Sinan’s masterpiece – the oft-touted index of the Classical Period in Ottoman architectural historiography. With a composition embracing the legacy of the classical tradition and materializing its evolution in a modern building centuries later, journalists associated Kemaleddin Bey’s work with the mythical image of Sinan. This reveals another cultural function of these articles; they depict Kemaleddin Bey as a national hero of his art. Through them, he is eulogized as “an architect, who revives Turkish architectural style,” and who “would leave a remarkable mark in the history of Ottoman civilization.” Kemaleddin Bey was thus fashioned as the flagbearer of the Turkish architectural style’s rebirth. Another article heralding the “genius art” of Kemaleddin Bey documented the building’s foundation laying ceremony and printed the commemorative text placed under the cornerstone (Haftalık Havadis 1913, 200). The dedicatory text reads:

Kemaleddin Bey, the principal architect and the virtuous general director of [the] Construction and Repair Department, has realized many aesthetic works along with the assistance of his staff. His works have rejuvenated Turkish architecture so far. On Monday, 5 Zi’lkâde 1331/23 Eylül 1329 [6 October 1913], this foundation stone of the “student dormitory” (the Fifth Vakıf Han) was placed in the presence of the merciful attendants to raise the next generation of Turks in the future. (Talebe Yurdunun 1913, 912)

Figure 3. A perspective drawing of the dormitory by Kemaleddin Bey.

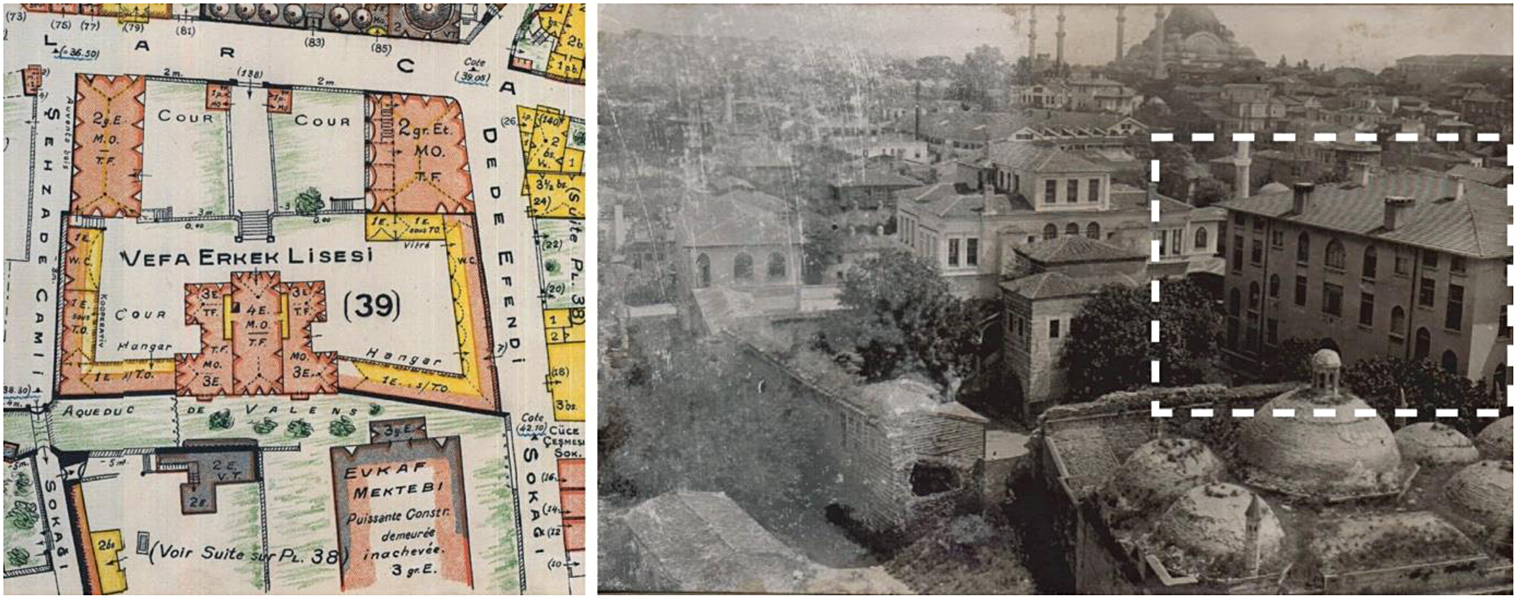

Bringing together several nationalist motifs, including the architect as national hero, the idealized public building, and its role in raising educated generations of the future, the media’s appreciation of Kemaleddin Bey’s Vakıf Han design, along with many of his other buildings, invited the masses to reconcile modernity with historicity. During the long war years, however, the building reached only the third-floor level before being abandoned due to economic hardship. According Kemaleddin Bey’s personal notes, which capture his disappointment with its current state, the building was incomplete, albeit, intact in 1922 (Çetintaş Reference Çetintaş1944, 171). In 1923, the Ministry of Education modified the project, removing two unconstructed upper floors, the conference hall, and the distinctive decorative program of the façade from the plans. After its inauguration, it served as the Teachers’ College (Yüksek Muallim Mektebi) until 1949 (Yavuz Reference Yavuz2009, 203–206) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Left: The Fifth Vakıf Han (labeled Evkaf Mektebi) on the Pervititch Insurance Maps (1934); Right: General view of the building in 1943.

Though the cultural synthesis approach employed in the plans for the Fifth Vakıf Han remained prevalent until Gökalp’s death in 1924, it was seriously challenged by intellectuals in the architectural field by the late 1920s (Bozdoğan Reference Bozdoğan2001, 59–60). Moreover, the unexpected death of Kemaleddin Bey in 1927 followed by the Ministry’s work with Ernst Egli and other like-minded Europeans who favored Modern Architecture, such as Bruno Taut and Clemenz Holzmeister, encouraged Modern Architecture to replace Turkish revivalist approaches. Many young Turkish architects also embraced this new approach enthusiastically because, as Bozdoğan has rightly pointed out, the new political regime sought to sever its connections to the Ottoman past. In architectural terms, this corresponded with the replacement of Ottoman forms with unornamented cubic buildings, a new vocabulary that complemented the rationalist and positivist nature of the Kemalist reforms. Therefore, a “new architecture” for “the new Republic” became the motto for new public constructions (Bozdoğan Reference Bozdoğan2001, 54). Nevertheless, despite the rhetorical break from the past in the 1930s, it is important to acknowledge that adopting this new architecture did not result in the immediate rejection of Ottoman architectural heritage for the early Republican intelligentsia. Besides, a sense of monumentality and classicism was always at stake, even in many cubic buildings in Ankara. Therefore, it is possible to talk about a gradual transition rather than a revolutionary break to explain the relationship between the Ottoman revivalists and early Republican Modernists because both were historicist (Bozdoğan Reference Bozdoğan2001, 56–105).

Conclusion

As demonstrated in this article, rather than following a single path to the reading of nationalist narratives, one may examine the textual construction of national themes in late Ottoman architecture by revisiting critical, historical texts. Interestingly, while many of the intellectual products of the Tanzimat era that culminated in Usûl served the principal motivation of legitimizing Ottoman architecture in European terms, it did not create an intellectual impact immediately among architects. Instead, as suggested by other late-nineteenth-century texts, Usul’s evolutionary trajectory was replicated, even though its central tenets were questioned. As a case in point, Kemaleddin Bey’s Mimari-i İslam exposes a moment of historiographical crisis at the turn of the century. As a reader of Usûl, Kemaleddin Bey maintained a critical distance toward the content of the text, though he did not hesitate to adopt its methodological toolset in the development of his own. Despite his objections to its arguments, he reproduced Usûl’s historiographical methodology by relying on an evolutionary scheme and employing an Ottoman Orientalism against other Islamic architectures. Though they challenged the text, Ottoman intellectuals like Kemaleddin Bey ultimately relied on Usul to think about the transformation of Ottoman architectural tradition since the fifteenth century (Gökalp Reference Gökalp1922; Kemaleddin 1911, 1913a, 1913b, 1917; Mehmet Reference Mehmed1913).

During the Second Constitutional Period, beyond the textual construction of national architecture, the intellectual medium was also enriched through the erection of new public buildings. The Ministry of Pious Endowments played a critical role in making these public buildings possible. Romanticism was a guiding component of the mainstream ideology of Turkish nationalism in this era, during which nationalist ideologues promoted architecture that reflected a national taste in its reproduction of Ottoman Classical heritage through revivalist elements. Therefore, the new architecture of the era became the medium for the different forms of Ottoman revivalism. Authors of pronationalist media went one step beyond the appraisal of the Ottoman architectural tradition. Just as Gökalp espoused in his writings, architects and anonymous authors problematized the reconciliation of tradition with modernity in public buildings. The official duty of Kemaleddin Bey in the Ministry of Endowments was intertwined with the realization of these design aspirations, and he was, for a time, the flagbearer of this approach in both his writings and designs. Using the example of Kemaleddin Bey’s student dormitory, this article identifies the role of pronationalist media and the alignment of modern functions with technology in the production of national taste during this period. Thus, the textual constitution of a modern genius architect image and many in-text references to the spatial formation, use of technology, comfort standards, and social impact of the building coherently reveal less-known aspects of architectural production in the early twentieth century.