Introduction

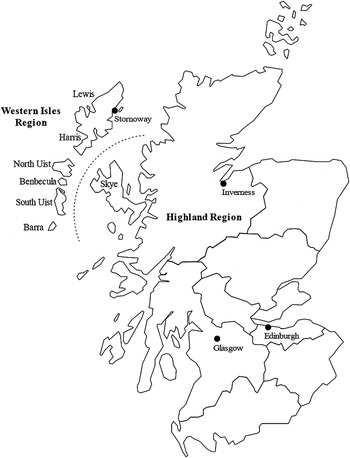

At a Presbyterian church service in the Western Isles of Scotland in 2000, I met a Scottish woman in her mid-twenties from the mainland who was studying Gaelic as a second-language learner. We were both living temporarily on the same island in Uist, the southern island group of the Western Isles, where over half the population is Gaelic-English bilingual (see Figure 1). I had come there for eight months to do ethnographic research, and she had come to live and work there for the summer hoping to improve her spoken Gaelic ability. She was earnest, friendly, and good-humored, and I admired her strong determination to speak Gaelic at all times. However, her Gaelic speech was halting, strongly influenced by English phonology, and punctuated by nervous giggles. I wondered at the time if her uncertain manner was exacerbated by the great difficulty she had in finding affordable accommodation and full-time employment in Uist.

When she began to attend the church regularly, she explained to everyone why she had decided to come to Uist, and she always attempted to speak in Gaelic to the Gaelic-English bilingual congregants. When she arrived, I had been attending the church for a few months already as part of my participant-observation fieldwork, and the minister and several congregants immediately directed her to me because “Emily is interested in Gaelic too” or “Emily is good at speaking Gaelic.” She and I spoke almost exclusively in Gaelic with each other during the next several months, at church services, social events, and chance meetings. After the first few weeks, however, I began to realize that the Gaelic-English bilinguals at church were repeatedly directing her to me for Gaelic conversation – and speaking to both of us in English most of the time. In so doing, they were effectively denying both of us any extended interaction with themselves in the medium of Gaelic, interaction that we both greatly desired for our own individual reasons.

FIGURE 1: Map of Scotland showing the Western Isles. This highly schematic map labels the major islands of the Western Isles, and indicates the boundaries of the administrative regions Eileanan Siar (Western Isles) and Highland Region (however, the other regional administrative boundaries depicted on the map are out of date.)

This woman never complained to me about the situation, but other adult Gaelic learners in Scotland expressed puzzled disappointment or frustration to one another about the reluctance of Gaelic “native speakers” to engage with them through the medium of Gaelic. In Alasdair MacCaluim’s 1998–1999 survey of adults learning Scottish Gaelic, 44 out of 643 respondents (6.8%) filled in an open-ended comment section on the survey with comments “critical of native speakers and their treatment of learners” (MacCaluim Reference MacCaluim2007:213). Representative comments included “In my experience native Gaelic speakers seem very unwilling (or too impatient) to converse in Gaelic with learners, and help them to improve” and “I cannot understand why native Gaelic speakers I have met are not supportive in maintaining their language and helping learners” (MacCaluim Reference MacCaluim2007:266). In 1998 an article titled “Despairing of native speakers,” which accused many native Gaelic speakers of a “resentment of learners,” appeared in Cothrom, the bilingual quarterly magazine of the Gaelic learners’ association in Scotland (formerly Comann an Luchd-Ionnsachaidh, now known as Clì Gàidhlig). Similarly, Newcombe noted in her study of adult Welsh learners in Wales, “One of the main problems for learners seeking to practise outside the classroom is persuading native speakers to maintain a conversation in Welsh” (Newcombe Reference Newcombe2007:40).

Ideological mismatches and conflicts between revitalization proponents and ordinary “native speakers” are typical of minority-language revitalization efforts aimed at halting processes of language shift (Dauenhauer & Dauenhauer 1998, Eckert Reference Eckert1983, Kabel Reference Kabel, McCoy and Scott2000, McDonald Reference McDonald1989, Trosset Reference Trosset1986). The first main argument of this article is that, while language ideologies are crucial components of processes of language shift and revitalization (Cavanaugh Reference Cavanaugh2004, Echeverria Reference Echeverria2003, Jaffe Reference Jaffe1999, McEwan-Fujita Reference McEwan-Fujita2003, Mertz Reference Mertz1982, Messing Reference Messing2007), affect is also a crucial component, and ideologies and affect are inseparably intertwined in the linguistic behavior of participants. The second main argument is that examining language shift and revitalization efforts from a perspective of language socialization (Ochs Reference Ochs, Gumperz and Levinson1996) allows us to explain how ideology and affect come to be conjoined in participants’ linguistic behavior and interpretation of social conflict.Footnote 2 This is so because a language socialization perspective draws attention to social interaction processes of “novices” being gradually socialized by “experts” through ongoing, recurrent linguistic practices to develop “an understanding of social actions, events, emotions, esthetics, knowledgeability, statuses, relationships, and other socio-cultural phenomena” in particular sociocultural contexts (Ochs Reference Ochs, Gumperz and Levinson1996:408). Such an approach is productive for the analysis of both language shift, perpetuated by linguistic socialization of children and adults, and language revitalization efforts, in which attempts to linguistically re-socialize both children and adults figure prominently. It is also productive because both language shift and revitalization are locally anchored in face-to-face interaction in which people enact and inculcate broader cultural meanings, ideologies, and structures of affect.

Language shift involves particular kinds of changes over time in the patterns of daily, habitual use of a spoken languageFootnote 3 in geographically defined communities. Gal (Reference Gal1979:1) describes language shift as a process in which “the habitual use of one language is being replaced by the habitual use of another” in “bilingual towns, villages, or neighborhoods.” Moore (Reference Moore1999:65) defines it as the process in which “the members of a local speech-community begin pervasively to abandon the use of one linguistic variety in favor of another, regardless of whether or not the language being abandoned continues to be spoken elsewhere.” Moore’s wording is ambiguous: Individuals may abandon the use of a linguistic variety altogether during the course of their own life cycle, but more commonly people seem to maintain the use of a variety with a particular network of interlocutors, while instead linguistically socializing younger individuals primarily or solely in the replacement language (consciously or unconsciously). Thus, changes in daily language use patterns favoring one language over another generally take place from one generation to the next, rather than in the life cycle of single individuals. Fishman (Reference Fishman1991:1) foregrounds this failure of intergenerational transmission in his description of the community context of language shift: “speech communities whose native languages are threatened because their intergenerational continuity is proceeding negatively, with fewer and fewer users (speakers, readers, writers and even understanders) or uses every generation.” Although language shift can be very usefully analyzed in regional and national perspective (e.g., Dorian Reference Dorian1981, Withers Reference Withers1984), language shift essentially involves face-to-face social interaction throughout the individual life cycle and across generations in the family, the home, and the local geographically bounded community where people encounter their neighbors and experience the local manifestations of the state and the nation through educational, religious, media, and other institutions.

During sociolinguistic processes of language shift, people indexically formulate ideologies of language, or “metapragmatic filters” (Mertz Reference Mertz1982) through which they interpret the macro-level changes they observe around them and according to which they shape their own linguistic and other behaviors (Gal Reference Gal1978, Reference Gal1979; Kulick Reference Kulick1992). Ideologies of language may be described as “cultural conceptions of language – its nature, structure, and use – and … conceptions of communicative behavior as an enactment of a collective order” (Woolard Reference Woolard1992, citing Silverstein Reference Silverstein1987:1–2; also see Gal Reference Gal1989, Schieffelin, Woolard & Kroskrity Reference Schieffelin, Woolard and Kroskrity1998, Silverstein Reference Silverstein, Clyne, Hanks and Hofbauer1979). The formation of language ideologies is “a process involving struggle among multiple conceptualizations” (Woolard & Schieffelin Reference Woolard and Schieffelin1994:58), or rather, struggle among multiple individuals and groups who base their positions on these conceptualizations. People enact ideologies of language shift and revitalization in discourse and other forms of social action (Cavanaugh Reference Cavanaugh2009, Jaffe Reference Jaffe1999, McEwan-Fujita Reference McEwan-Fujita2003, Messing Reference Messing2007).

Language ideologies are a crucial component of the process of language shift, but I argue that affect is an equally crucial component. I have opted to use the term “affect” instead of “emotion,” following the usage of Ochs & Schieffelin (Reference Ochs and Schieffelin1989:7), who “take affect to be a broader term than emotion, to include feelings, moods, dispositions, and attitudes associated with persons and/or situations” (cf. Besnier Reference Besnier1990:420). Scholarship on the anthropology of emotion (Lutz & White Reference Lutz, Abu-Lughod and White1986) and the linguistic anthropology of language and emotion (Lutz & Abu-Lughod Reference Lutz and Abu-Lughod1990, Wilce Reference Wilce2009) has shown how culturally specific categories of affect are discursively constructed and displayed in linguistically mediated social interaction (Besnier Reference Besnier1990; Cavanaugh Reference Cavanaugh2009:13; Lutz & Abu-Lughod Reference Lutz and Abu-Lughod1990:11; Ochs & Schieffelin Reference Ochs and Schieffelin1989:7). While affect is constructed discursively, this process is not a one-way street: Established cultural categories of emotion and other kinds of affect also dialectically shape people’s metalinguistic discourse and their language behavior more generally, particularly in situations of language shift. Wilce Reference Wilce2009 advocates including affect, and its embodied dimension, in a broader definition of ideology. However, I believe that it is still useful to keep the terms analytically distinct, because each term can do different work. The concept of ideology as ideational notions or models brings in a consideration of social and power relations more usefully than does the internally focused concept of “attitudes” (Wilce Reference Wilce2009:115–116), yet I would argue that keeping the concept of affect separate still allows us to consider the intersection between embodiment and social action in language use more effectively than does the ideationally focused ideology.

Affect pervades discourse (Besnier Reference Besnier1990:421): “Whenever speakers (or writers) say anything, they encode their point of view towards it … The expression of such speakers’ attitudes is pervasive in all uses of language” (Stubbs Reference Stubbs1986:1, quoted in Englebretson Reference Englebretson and Englebretson2007:17). Speakers can express affective stance through a multitude of linguistic forms and structures (Besnier Reference Besnier1990:421; Ochs Reference Ochs, Gumperz and Levinson1996:411), and one may observe and analyze speakers’ affect by identifying ways in which they index their affective stance in language. Ochs (Reference Ochs, Gumperz and Levinson1996:410) defines affective stance as “a mood, attitude, feeling, and disposition, as well as degrees of emotional intensity vis-à-vis some focus of concern.”

Language ideologies and affect jointly contribute to processes of language shift and revitalization in familial and local community contexts through indexical, dialectical processes of language socialization. As Besnier (Reference Besnier1990:420) notes, principally citing the works of Ochs and Schieffelin, “In many cultures, affect plays a central role in language socialization, and vice versa.” Ideologies are never expressed or enacted without the speaker’s affective stance toward them being encoded in the discourse. Thus, when experts communicate ideologies to novices, they also communicate their affective stances toward these ideologies through processes of indexicality. As Ochs explains:

A basic tenet of language socialization research is that socialization is in part a process of assigning situational, i.e., indexical, meanings … to particular [linguistic] forms … To index is to point to the presence of some entity in the immediate situation-at-hand.

(Ochs Reference Ochs, Gumperz and Levinson1996:410–11, original emphasis)These indexical, or situational, meanings of linguistic forms are based on contiguity in time, space, or other connection, and may include “temporal, spatial, social identity, social act, social activity, affective or epistemic meanings” (Ochs Reference Ochs, Gumperz and Levinson1996:410). Indexes like code choice may be nonreferential (Silverstein Reference Silverstein, Basso and Selby1976), so that a codeswitch (from Gaelic to English, for example) invokes or indexes a particular dimension of a social situation with which it has become “conventionally associated” (Ochs Reference Ochs, Gumperz and Levinson1996:411; see also Blom & Gumperz Reference Blom, Gumperz, Gumperz and Hymes1972), without contributing to the referential meaning of a communicated proposition (Ochs Reference Ochs, Stigler, Shweder and Herdt1990). The assignment of indexical meanings to minority and majority linguistic varieties and code choices, often in opposing pairs, is a crucial dimension of language shift (Cavanaugh Reference Cavanaugh2009, Kulick Reference Kulick1992, Kuter Reference Kuter and Dorian1989).

The language socialization processes that contribute to language shift are dialectical and potentially reciprocal, and they occur continuously in the individual life cycle. They occur not only in the socialization of novice children by expert adults, but also in the socialization of novice adults by expert adults. Moreover, as Ochs points out, even if it is asymmetrical, socialization is always potentially bidirectional; novices may in fact socialize experts, and each may “impact each others’ discourse knowledge” (Ochs Reference Ochs, Stigler, Shweder and Herdt1990:302–3). In fact, the power struggle over who gets to play the role of “expert” (and thus of socializer) is one of the anthropologically interesting aspects of language shift and revitalization that can be studied ethnographically (e.g., Hill Reference Hill1985).

Language shift is a geographically and temporally uneven process that results in the uneven distribution of linguistic skills, ideologies, and affective orientations across populations. Changes in habitual linguistic behavior do not happen uniformly within any definable social context of shift, whether it is the family, the geographically defined locality or region, state institutions, or the nation-state as a unit (Dorian Reference Dorian1981, MacKinnon Reference MacKinnon1977). Nor do changes happen uniformly over time in a geographical area; there may be an apparently stable bilingualism for decades or centuries in a region, followed by a “tip” to the majority language marked by a relatively sudden change in intergenerational transmission practices among the majority of a community (Coleman Reference Coleman1975, Dorian Reference Dorian1981, Mertz Reference Mertz and Dorian1989). Therefore, in a situation of language shift, in any given community – or even family – individuals will be found with differing linguistic socialization experiences, which contribute to varying distributions of linguistic skills and varying ideological positions and affective stances on linguistic varieties and language use. (The 2001 Scottish census results illustrate the varying distributions of Gaelic linguistic skills in the case of shift from Gaelic to English; see Table 1.) Furthermore, any one of these elements may also shift over time for any given individual, owing in part to further socialization experiences. In a local geographically bounded community undergoing language shift, therefore, people who have been socialized into multiple and conflicting ideologies, and expectations of and affective orientations toward linguistic behavior, will be in frequent contact with one another.

TABLE 1. Gaelic language abilities claimed by respondents in the 2001 Scottish census.

Source:

Table UV12, General Register Office for Scotland, 2005.

When people observe language behavior in others and themselves that does not conform to their ideologized expectations, they take an affective stance as they express their reactions and evaluations. Lutz & White (Reference Lutz, Abu-Lughod and White1986:406) propose “looking at emotions as one cultural idiom for dealing with the persistent problems of social relationship.” They outline a taxonomy of these persistent and universal problems which includes two problems particularly relevant in processes of language shift: “1. the other’s violation of cultural codes or of ego’s personal expectations (or conflict more generally) … [and] 2. ego’s own violation of those codes, including social incompetence or personal inadequacy, and awareness of the possibility for such a failure” (Lutz & White Reference Lutz, Abu-Lughod and White1986:427). From this perspective, we can see how language shift and language revitalization efforts generate and express “persistent problems of social relationship” resulting from the mismatch between “cultural codes” or “personal expectations” of behavior of individuals socialized into different ideologies and affective stances about Gaelic language use.

Expressions of negative affectFootnote 4 seem to be common in situations of shift from a minority language to a state-sponsored European language, whether they take the form of grief over the loss (Dauenhauer & Dauenhauer Reference Dauenhauer, Dauenhauer and Quasthoff1995), regret and anger about not having the language passed on to oneself by one’s parents (MacCaluim Reference MacCaluim2007:267–68; Newton Reference Newton2005), shame at being a speaker of a minority language, or denigration and contempt from majority language speakers (Bonner Reference Bonner2001; Dauenhauer & Dauenhauer 1998:64–66; Kuter Reference Kuter and Dorian1989; Tsitsipis Reference Tsitsipis1981, Reference Tsitsipis1998). However, the language revitalization efforts that are aimed at halting language shift, particularly language-learning efforts, can also generate negative affect among participants. Trosset (Reference Trosset1986:185) applies literature on the anomie and shame of second-language learning in general to the experiences of adult learners of Welsh, discussing the embarrassment of becoming a childlike linguistic novice again as an adult, and the painful process of breaking down the old social identity and forging a new one. Newcombe (Reference Newcombe2007:66–70) likewise identifies anxiety as a major barrier to L2 Welsh language learning, using interviews and journals from participants in the Adult Welsh Learners’ Project to document the phenomenon.

An important potential source of negative affect in minority language learning seems to be the awareness that adult learners develop of their own and others’ inability to measure up to their ideologized expectations. In the case of Jaffe’s Corsican university students in the first-year Corsican language class at the Corsican Studies Institute, their “painful, strangled silence” on the first day of class was the result of their awareness of their own limited Corsican language competence in a context where the essentializing significance of Corsican competence for the Corsican ethnolinguistic nationalist agenda was foregrounded (Jaffe Reference Jaffe1999:200–2). In the case of Gaelic in Scotland, adult learners’ ideologized expectations of themselves and others seemed to concern the relative ease with which they expected to learn Gaelic, speak Gaelic to others, and have others speak Gaelic to them, based on their previous language-learning experiences, their residence in a Gaelic-speaking area, and/or their family background with Gaelic. In interviews with me, Gaelic learners described and enacted “Standard Average European” categories of emotion such as blame, shame, fear, uncertainty, bewilderment, envy, and lack of confidence in connection with their efforts to learn and speak Gaelic, whether as an avowed second language or as an avowedly reclaimed inheritance. Before discussing in greater detail the socialization and enactment of ideologies and affect in and by adult Gaelic learners, I shall describe the seven adults I interviewed for this study, and set them in the context of adult Gaelic learning in Scotland more generally.

Adult Gaelic “learners”: Context and Description

All adults learning Gaelic in Scotland are now doing so in the context of language shift. Gaelic speakers began to settle in Scotland in perhaps the late 5th century ce, and most of what is now known as Scotland was Gaelic-speaking at one time or another. Since the 13th century ce, Gaelic-speaking areas in Scotland have been shrinking (Thomson Reference Thomson and Thomson1994:89–90). By the 19th or early 20th century at least, an influx of English speakers and ideologies of language shift had weakened the Gaelic-speaking social norms of these areas. One native of the Isle of Lewis commented: “What used to happen in our communities, when someone came into our community without Gaelic, they had to learn it to survive. I would say the real decline set in in the late ’70s” (F1, #28). By the early 1980s, all Gaelic-speaking communities in Scotland no longer linguistically integrated the new adult members who joined through in-marriage and other forms of in-migration (MacArthur et al. Reference MacArthur, Macaulay, MacDonald, Macdonald, MacKay, MacLeod, MacQuarrie and Spencer1982:14, 16).

Galloway Reference Galloway1995 estimated the total number of adults actively learning Gaelic in Scotland to be approximately eight thousand. On the basis of a 1998–1999 survey of Gaelic learners, MacCaluim narrowed Galloway’s estimate to “fewer than 1000 fluent Gaelic learners and probably quite a lot fewer” (MacCaluim Reference MacCaluim2002:347; emphasis added). Unlike the Irish state education system, the Scottish education system does not contribute substantially to an increase in the number of people who can claim Gaelic language ability. This is so because Gaelic language education is not compulsory in Scotland at the national level, and in fact it is not available at all in many areas.Footnote 5 Nor is Gaelic language ability required for most kinds of state employment, excepting Gaelic-language or Gaelic-medium teaching in the Scottish education system and a handful of other clearly Gaelic-related positions.

The seven adult Gaelic learners interviewed in 2000 for this study lived in Uist (or “the Uists”), a group of islands in the southern half of the Western Isles that includes North Uist, Benbecula, South Uist, and several smaller adjoining islands (see Figure 1). The Western Isles are the only remaining area of Scotland, and the world, where over 60% of the population is able to speak and/or understand Gaelic.Footnote 6 In the 2001 census, 66% of the total population of the Uists over the age of three was counted as Gaelic speakers, or 3,206 out of 4,857 people (see Table 2).Footnote 7 The significance of my interviewees’ residence in the Western Isles is that they live in an area where they are more likely to interact on a daily basis with people who were socialized in childhood as Gaelic-English bilinguals. In the ideological framework of learning a state-sponsored majority language like French or Japanese, people normally assume that living in an area where the language is spoken in a community context will increase opportunities for hearing and speaking the language outside the highly controlled classroom context, and thus potentially lead to faster and better language acquisition. However, this is not necessarily the case in minority language situations (Kabel Reference Kabel, McCoy and Scott2000:135; Newcombe Reference Newcombe2007:41; Trosset Reference Trosset1986).

TABLE 2. 2001 Scottish Census Results: Number of Gaelic Speakers Living in the Uists and Benbecula. Extrapolated from 2001 Census, Table UV12, Knowledge of Gaelic.

Source:

Scotland’s Census Results Online, http://www.scrol.gov.uk/, General Register Office for Scotland, 2005.

Because of the small number of subjects, and their non-random recruitment as a convenience sample, I did not perform any formal statistical analyses to correlate responses with sociological factors such as age and occupation; instead, I offer a brief narrative description of the interviewees. However, my interviewees are demographically similar to the respondents in the 1998–1999 survey of 643 adults learning Scottish Gaelic mentioned above, which included 392 respondents living in Scotland (MacCaluim Reference MacCaluim2007). MacCaluim’s description of adult Gaelic learners in Scotland is the most complete in existence, and it helps to demonstrate by comparison that my interviewees were most likely representative of the small group of adults learning Gaelic while living in Uist.

My interviewees were mostly female (five women, two men), which is roughly congruent with the gender distribution of MacCaluim’s survey respondents resident in Scotland who were taking evening language courses. A majority of them were women, although for a variety of reasons this does not, as he indicates, prove that more of the adult learners in Scotland are actually women (MacCaluim Reference MacCaluim2007:114). The age distribution of my interviewees, who were all in their forties and fifties, was likewise congruent with that of MacCaluim’s survey respondents resident in Scotland, 61.6% of whom were aged 40 and over, with the single largest group (23.8%) aged 40–49 (MacCaluim Reference MacCaluim2007:115).

In their place of birth and stated nationality, which was congruent in all seven cases, four of my interviewees were Scottish, two were English, and one was U.S. American. This is also reminiscent of the proportions among MacCaluim’s survey respondents living in Scotland: 77.3% were raised in Scotland, 14.8% in the rest of the U.K., 2.55% in the rest of Europe, 1.3% raised in the United States, 1% in the Commonwealth, and 0.8% in more than one country (2007:118). All of my interviewees had moved to Uist as adults sometime between their mid-twenties and late fifties, and had lived there for between 2 and 20 years each. Though they had all made Uist their only home, none of them were considered “locals” in the locally defined sense of having been raised in Uist with at least one parent born in Uist (Burnett Reference Burnett1997). However, while four interviewees had no family connections with Uist, one had a spouse with Hebridean family connections, and two had a Gaelic-speaking parent originally from Uist but had been raised on the mainland of Scotland or elsewhere.

The interviewees had a range of employment statuses: four worked full-time outside the home, one was retired, one was on permanent disability, and one was financially independent and engaged in significant community volunteering. They were all university-educated, and in this regard they were also like the majority of MacCaluim’s respondents residing in Scotland, 52.1% of whom had a higher education qualification (MacCaluim Reference MacCaluim2007:122–28).

In regard to language ability, two were beginners, one intermediate, and four advanced, by my definition. The beginners had taken only two Gaelic courses over a period of 1 to 2 years at the time of the interview. The intermediate-level interviewee had taken several courses over a period of several years and could understand and hold some basic conversations. The advanced interviewees had attained quite high levels of oral, aural, reading, and writing proficiency: They could carry on conversations in Gaelic of varying length, understand conversations and to some extent Gaelic radio broadcasts, read texts written in Gaelic such as newspaper articles, and write letters and homework assignments, some with the use of a dictionary. Prior to interviewing them, I took a course with two of the advanced students, and I sat in on one class session of a course that one of the beginner students took.

When asked, the interviewees described a variety of motives for commencing and continuing the study of Gaelic, including being “keen on languages” in general, wishing to speak the language their parents had spoken, and wishing to learn more about the local culture, which they recognized as distinctively Gaelic.Footnote 8 One beginner without family ties to the islands, whom I call “Linda,” said “We just thought, well here we are, in the Western Isles, and the way to fit in is to have a go” (X5, #544). “Isabel,” who did have family ties, said “[My husband]’s from a Gaelic-speaking family, his parents were still alive, and his mother, she was quite keen that I learned, quite pro-Gaelic, she loved Gaelic with a passion, she was really good about speaking to me in Gaelic, so that was my motivation.” In general they seemed to regard their study of Gaelic as based on a combination of personal interest and goodwill; none were studying it for directly instrumental reasons of advancement in employment or in an academic or training course.Footnote 9

One important factor to consider in the overall struggles of both my interviewees and MacCaluim’s survey group to attain fluency in Gaelic is the difficulty of finding regular, coordinated language instruction. MacCaluim describes the Gaelic learning infrastructure in Scotland in great detail (2007:20–75) and concludes that provisions for adults to learn Gaelic are “fragmented, [with] many serious gaps in provision and lack[ing] any overall strategic coordination” (2007:228). In Uist I found that Gaelic language courses for adults were available from time to time, at various levels, in various formats, and in various venues, and the teachers who offered them were talented and dedicated, but there was no coordination between the offerings and no organized way to progress through a Gaelic language-learning curriculum. This is quite different from the situation described for some other Western European minority language situations, such as Basque in the Basque Autonomous Community (Azkue & Perales Reference Azkue and Perales2005). This lack of coordination has been a major factor holding back adults from learning Gaelic to fluency in any great number, as has the sheer difficulty of learning a language as an adult, though the ideological and affective socialization discussed in the following section also significantly shaped their learning experiences.

Ideologies and Affect of Language Shift and Minority Language Learning

Now I shall examine the ideological and affective mismatches that arise out of encounters between people with different language socialization experiences in the context of language shift in Uist, connected to my interviewees’ efforts to learn Gaelic as a second language. The adult learners interviewed for this study come from a variety of backgrounds; as already mentioned, two of the seven were children of “native speakers” who had not transmitted Gaelic to them in the home, while the other five were Scottish, English, or U.S. American and had no family connections with Gaelic (although one had previously lived and worked in Wales and observed the situation of Welsh). An important additional factor to consider is that the interviewees’ expressions of affect were discursively co-constructed with the interviewer, who was known to each interviewee not only as a researcher but also as an adult Gaelic learner with no family connections to Gaelic.

Socialization of ideology and affect in the family context of language shift

“Alison,” one of my advanced-level interviewees who had no family background with Gaelic, reflected on the advantage that she perceived in having a Gaelic-speaking family member: “I have this thing, I see everyone who’s become quite fluent in Gaelic, that they’re quite a good linguist, or they’ve got a Gaelic granny in the background that they haven’t told you about” (G11, #438). However, the experiences related to me by the two interviewees who had at least one Gaelic-speaking parent did not bear out the imagined advantage of a “Gaelic granny.” Both of them had been socialized by Gaelic-speaking parents not to speak Gaelic in the home, and they described and implied mismatched ideologies, expectations, and affective orientations toward Gaelic speaking in the family context that seem to have arisen out of their socialization experiences.

Both interviewees described several kinds of apparent “social relationship problems” (Lutz & White Reference Lutz, Abu-Lughod and White1986:406) regarding intergenerational non-transmission of Gaelic in their families. The problems included conflict between themselves and their parents about the non-transmission of Gaelic; conflict between themselves and other kin, particularly siblings and cousins, over the value of Gaelic; and problems both in acquiring Gaelic and in transmitting it to their own children. The problems seem to center on the previously mentioned themes of “the other’s violation of cultural codes or of ego’s personal expectations” and “ego’s own violation of those codes, including social incompetence or personal inadequacy” (Lutz & White Reference Lutz, Abu-Lughod and White1986:427).

We can best understand each of these types of problems if we ask in each case: (i) What is the ideological basis of the cultural code(s) or expectation being violated? And (ii) what kind of affective stance is the interviewee taking in interaction with the interviewer that frames this as a problem? For these learners, the ideological basis might best be described as a bundle of closely related nationalist ideologies of language applied in a language-learning context, including (i) the idea of “native speakers” as naturally produced entities rather than socialized beings, (ii) the accompanying naturalization of intergenerational mother tongue transmission, (iii) the idea of the family as the internally homogeneous unit of language socialization, (iv) the notion that Gaelic-speaking parents could transmit some essential Gaelic ethnic identity to them that would enable them to learn the language more easily (what Dauenhauer and Dauenhauer 1998:84 term the “genetic fallacy”), and (v) the idea of bilingualism as parallel monolingualisms (Heller Reference Heller2006). For the parents themselves, on the other side of the ideological mismatch, these covertly essentialist and nationalist ideologies of language learning were most likely countered by ideologies of ensuring the future success of their children by socializing them to speak English (Mertz Reference Mertz1982).

Answering the second question posed above, these interviewees took a stance of negative affect as they sketched the dimensions of their own family language socialization experience for the interviewer. The interviewees did not explicitly frame the intergenerational non-transmission of Gaelic by one or both of their parents as a problem, but as Besnier (Reference Besnier1990:428) points out, “affect is most commonly expressed covertly in natural discourse.” Affective stance, like other aspects of stance, is also relational and dependent on context (Englebretson Reference Englebretson and Englebretson2007:15). The very fact that these individuals actively undertook to learn Gaelic as adults, after being raised in a family with a Gaelic-speaking parent who linguistically socialized them to speak English instead, implicitly frames their effort as redressing a perceived conflict or failure, and frames the cessation of intergenerational language transmission in their family as a problem.

The first interviewee, “Jean,” raised the issue of her family background with me during an interview conducted after we had taken a six-week Gaelic course together (Alison, just mentioned, was also on the course). I did not record the interview; I took largely verbatim typed notes on a computer as I conducted it, and constructed a transcript from these notes immediately afterward. The interview was semi-structured; I was working from a schedule, but tailored it to fit each interviewee’s individual situation. A transcript of the relevant portion of our interview follows:Footnote 10

(1) 1 EM: So are there any people around that you speak to regularly in Gaelic?

2 Jean: None at all.

3 EM: Any.

4 Jean: I could, but I don’t.

5 EM: Not even a bit?

6 Jean: People speak in Gaelic, and I’ll answer in English, or whatever. But I listen. [to people

7 speaking Gaelic] ((pause)) But there’s plenty people I could speak to. My parents speak

8 Gaelic.

9 EM: Where do they live?

10 Jean: [Mainland city]. My mother’s from [island]. My father’s from [west coast Highland

11 village].

12 EM: Oh, on the mainland, so he speaks Gaelic too? That’s unusual these days, isn’t it, a

13 Gaelic speaker from the mainland?

14 Jean: {Yes, well, I think he didn’t speak Gaelic as much until he met my mother.}

15 EM: Do you have brothers and sisters?

16 Jean: I have five brothers and sisters, and none of them are interested in Gaelic.

17 […]

18 EM: Did your parents speak Gaelic in front of you so that they could talk without you

19 understanding?

20 Jean: Yes.

21 EM: What made you decide to start learning it yourself?

22 Jean: I came here on holiday. It was probably just the same, about seven years ago. I started

23 learning it. ((pause)) But I didn’t realize it would take so long.

24 EM: Do you speak it with your parents?

25 Jean: Only if I’m asking about my homework and things. Not really. I don’t find they’re

26 particularly good at ((small laugh)) understanding me. (N10, #440)

Jean subtly indexed a stance of negative affect through a style of self-disclosure that was constructed through several paralinguistic and discourse-level features. First, she used pauses and a laugh to precede and affectively frame moments of self-disclosure in lines 6–8, 22–23, and 25–26. The first self-disclosure in lines 6–8 revealed to me the existence of her Gaelic-speaking parents, who, she nonetheless implied, she did not speak to in Gaelic. The second self-disclosure in lines 22–23 was an explicit statement of how her Gaelic learning experience had violated her expectations about the amount of effort and time required to learn Gaelic, and the third self-disclosure in lines 25–26 was the reason for her inability to communicate in Gaelic with her Gaelic-speaking parents. The pauses added drama to her disclosure to me, and may have also indexed a reluctance to disclose the information, while the laugh indexed a sense of humorous irony and self-deprecation. The topics of these self-disclosures can be defined as problems of social relationship as defined earlier: (i) violated expectations of others, in this case her parents who did not transmit Gaelic to her as a child and who have difficulty speaking with her in Gaelic now, and (ii) violated expectations of self in the matter of acquiring Gaelic more easily as an adult child of Gaelic-speaking parents.

Jean’s interview responses were also distinguished by discourse-level features that constructed a negative affective stance. At certain moments, Jean self-disclosed with terse replies and the gradual, guarded revelation of information. Her responses to my questions were noticeably terse compared with those of the other seven interviewees, sometimes revealing the bare minimum, as seen in lines 1–4 and 18–20. Another example came later in the interview, which is not included in the transcript above:

(2) EM: Are there any people who greet you regularly in Gaelic, and then switch into English?

Jean: Yeah…. ((she trailed off and didn’t volunteer any more))

Jean’s tersest replies were on the topic of people not speaking Gaelic (despite their apparent ability): Jean not speaking Gaelic to others (although she could), her parents not speaking Gaelic to her (although they could), and other people in the community not speaking Gaelic to her (although they could). Her abbreviated replies, while possibly indicating a more reticent personality, could also be interpreted as affective stance markers constructing negative affect toward the dissonance between ideologized expectations (people who can speak Gaelic will naturally speak it in any given situation) and actual social events (people who can speak Gaelic don’t in certain situations). They also mirror and poetically intensify the topic itself: not speaking.

During the six-week course we had attended together, Jean had never mentioned her Gaelic-speaking parents to either me or Alison. During our interview, I used our social relationship based on our shared learning experience, and my prior observation of Jean’s considerable Gaelic language ability, as a license to gently press her on the point of whether she actually spoke Gaelic to anyone in the Gaelic-speaking community. I explore this point further in the following section, but here I focus on how she spontaneously disclosed information about her parents as Gaelic speakers (lines 5–8), her siblings as uninterested in Gaelic (lines 15–16), and her boyfriend as a Gaelic speaker with whom she did not speak Gaelic. In each case, she disclosed the information in a statement that augmented her direct response to a different question. In a section not included in the transcript above, she even introduced the topic as a non sequitur following a longer sequence of questions and answers about Gaelic speaking in the workplace:

(3) EM: [Does the organization where you work] have a Gaelic policy?

Jean: No. ((pause)) My boyfriend is from [the island], {he speaks Gaelic}, he would speak if I wanted to. I’m just not good at conversation, my mind goes blank when people speak to me.

When compared to Jean’s terse replies to other questions, these self-disclosures are even more noteworthy. Like her pauses, her volunteering of new information in this way created an affective impact on the researcher – it surprised me. And it constructed an affective stance toward the mismatch between her expectations and those of her five siblings: Her effort to learn Gaelic as an adult enacted the positive value of Gaelic, while she described in implicit contrast (and conflict) how her five siblings were not interested in Gaelic.

Finally, Jean’s self-disclosures are part of an even more complex discursive strategy, a “dance of disclosure” in which she alternated between denying and disclosing her own and others’ Gaelic-speaking ability and use to me. Her responses to my line of questioning about whether there was anyone with whom she regularly spoke in Gaelic form a striking sequence of denial and disclosure, which becomes clear when the relevant elements of the transcript are arranged in table form, with the denials shaded (see Table 3). Her terse replies to my questions in this dance of disclosure enact the shame and other negative affect of intergenerational language transmission failure for one individual in her own social and familial context of language shift: her sense of social incompetence and personal inadequacy over speaking Gaelic in everyday life, her failure to learn Gaelic quickly, and her failure to interact with her parents in Gaelic, which are framed as failures through negative affect and ideology. Framing her self-disclosures with pauses and a self-deprecating laugh, phrasing them with economy, and doling out information to me in a dance of denial and disclosure, Jean incrementally constructed an account of language shift in her family, her own learning efforts, and her negative affective stance toward these topics.

TABLE 3. Jean’s denial and disclosure of Gaelic speaking, Gaelic speaking ability, and availability of Gaelic speakers with whom to speak.

“Graham,” the other interviewee with a Gaelic-speaking parent, was the most fluent Gaelic speaker I interviewed. Similarly to Jean, he discussed interaction with his mother in Gaelic, and his mother’s Gaelic language ability in the context of family interaction, in poignant terms. I also quote the relevant section of his interview at length here before proceeding with the analysis:

(4) 1 EM: Is there anyone that you speak to exclusively in Gaelic?

2 Graham: No I don’t think so. […] …we’ll switch between Gaelic and English quite a lot… […]

3 My mother from time to time, on the phone, not so much face to face.

4 EM: Why not face to face?

5 Graham: Face to face you’re usually in the company of other people as well. Usually {there’s}

6 the company of other family members to consider.

7 EM: So [your mother] didn’t speak Gaelic to you at all as a child?

8 Graham: No, one or two words. A ghaoil, a lot of kids who’ve had Gaelic speaking parents

9 {would recognize that one}.

10 EM: Did you hear much Gaelic growing up then?

11 Graham: Uhm, not a lot, but that was at a time, and a place in fact, I was born in [large Scottish

12 city], but the family was basically based [overseas in a former British colony] at the

13 time, my father is English, and you’re talking [19]50s here, so there were different

14 attitudes around towards little languages like that.

15 EM: Did you know that your mother spoke Gaelic?

16 Graham: Oh yeah, we were conscious that mum spoke another language, because we would hear

17 her speak it on the phone to her sisters, we would come here [to the island] for summer

18 holidays, {And my father would occasionally ask my mother} “And how do you say

19 that thing in Gaelic, ((laughing)) how do you get those sounds out” ((guffawing,

20 honking and harumphing in an English accent imitating his father)), she was on a

21 losing streak, she did her best. My cousins spoke Gaelic, cousins of my own age, I

22 remember conversations with them. Because our first family experience was in

23 {another linguistic environment, I was conscious of some people being able to speak

24 more than one language.} I was very envious of my cousins. I remember saying I

25 wished I could speak another language. And they would come back with “Wish I only

26 spoke one.”

27 EM: Do you speak Gaelic to [your children]?

28 Graham: No, not much. Very little. No, it’s partly a confidence thing as well. I mean, I wouldn’t,

29 I suppose, the time to have done it would have been from the start, seven years ago

30 now, and that was in [Scottish city], it wasn’t here, and my Gaelic, I wasn’t confident

31 enough in my Gaelic to know if I would be able to handle that, I still don’t know the

32 Gaelic for fingers and thumbs, and bibs and things. ((pause)) Once [my younger child]

33 starts at the Gaelic medium unit it may easier or more natural.

34 EM: ((Picking up the thread of an earlier discussion we had about a conference paper I

35 had given, I told him that given my observations so far, I didn’t think it

36 necessarily would be.))

37 Graham: It’ll be a performance thing for our family. […] It’ll always be a conscious thing. (S1,

38#483)

In his interview, Graham signaled his affective stance toward his family language socialization experience with Gaelic in ways that were quite different from Jean’s, but were still subtle, implicit, and at the discourse level. He used general description, voicing, and direct reported speech to index both social and familial disapproval of Gaelic. In lines 5–6 and 11–14, he gave a sense of Gaelic speaking as something that had to be carefully managed in order to avoid disapproval from “other people,” “other family members,” and “different attitudes around,” whether in the home or out in public, on a Hebridean island or in a large Scottish city. Like many children of Gaelic speakers throughout the 20th century, in childhood he heard Gaelic being spoken around him, but almost never to him. He seems to have been socialized into the “etiquette of accommodation,” analyzed in detail in the following section, in which Gaelic should not be spoken in the presence of, or even within hearing distance of, non-Gaelic speakers. He voiced the disapproval of these un-named others – and of his English father – with the description of “different attitudes around toward little languages like that” in 1950s urban Scotland (lines 13–14). Unlike diminutives in many linguistic-cultural contexts, “little” in this case indexes a diminishment of status, and voices a negative affective stance.

Graham also used reported speech to great effect, constructing his own affective stance by reporting the stance-taking speech of others. First he implicitly contrasted his mother’s and his father’s own affective stances toward Gaelic. In lines 8–9, he mentioned the “one or two words” of Gaelic that his mother would speak to him as a child, quoting his mother’s use of the common Gaelic term of endearment A ghaoil (‘Love’, in the vocative case). Later in the interview, in lines 18–20, he quoted his English father denigrating his mother’s Gaelic. The fact that it was denigration was conveyed in Graham’s extraordinary mocking imitation of his father, which I described impressionistically in my notes taken during the unrecorded interview (lines 19–20). It was a brief, loud, deep-voiced outburst consisting of rapid alternation between laughter, nasal English-accented mock speech, and clearing of the throat (“harrumphing”) interspersed with voiced condescension, mockery, and distancing of Gaelic phonology (How do you get those sounds out) (see McEwan-Fujita Reference McEwan-Fujita2003:179–93 on similar mockery of Gaelic in the Scottish press). Graham implied that it was partly through his father’s denigration that he became aware of his mother’s ability to speak Gaelic. His affective stance is in support of his mother, describing her as repeatedly or inevitably losing a conflict with her husband, and doing her best to withstand the denigration of her native language and perhaps to preserve face in front of her children. He had aligned himself with his mother as a Gaelic speaker early in our interview, saying that he had learned Gaelic because it’s my mother’s language, and listing several other reasons before concluding and {it} seemed to me I should be learning my own.

Immediately after quoting his father, Graham constructed a poignant contrast between his own and his cousins’ desires to speak Gaelic vis-à-vis English, again through indirect and direct reported speech, in lines 21–26. Graham heightened the affective contrast between his monolingual young self who wanted to be bilingual, and his bilingual cousins who wanted to be monolingual, through the juxtaposition of his I wished I could speak another language with their Wish I could only speak one. In describing interaction with his cousins, Graham was even more explicit in indexing his affective stance of desire to speak Gaelic than he was in describing interaction between his parents.

Both Jean and Graham described and implied mismatched ideologies, expectations, and affective orientations toward Gaelic speaking in their family context. Their accounts to me of their early language socialization experiences demonstrate past and present conflict with siblings, cousins, and parents over the value of Gaelic. One more issue raised by both Jean’s and Graham’s interviews regarding the family context of language transmission was that they did not transmit it to their children as a first language. In Jean’s case, she did not arrive in Uist until her child was in secondary school. Her child started studying Gaelic as a subject at the local secondary school but soon dropped it because it was “too hard for her to keep up. […] Her careers advisor told her German would be more useful to her. But she’s dropped that now too.” Jean herself did not give any indication in the interview that she had ever considered it a possibility to transmit Gaelic to her child. Graham’s children were younger when he moved to Uist, but he did not arrive there until after his elder child had already started English-medium primary school on the mainland. Graham again explicitly expressed his affective stance toward transmitting Gaelic to his children as he explained how a “lack of confidence” with the language factored into not attempting to speak Gaelic to his children in the home. Both interviewees mention a number of social factors that did not or could not support them in transmitting Gaelic to their children, including the timing of their own Gaelic study, the timing of their move to Uist, and the state-sponsored institution of the school. Both interviewees also expressed an affective stance through explicit statements of a lack of confidence in their language learning, that probably contributed to the non-transmission of Gaelic to their own children.

Adult learners who were linguistically socialized by a Gaelic-speaking parent or parents, but who acquired Gaelic only incompletely or not at all in the family context, have had very different language socialization experiences than people with no living family connection to Gaelic. However, their particular experiences, skills, and socialized affective orientations toward Gaelic speaking are not usually taken into account in provisions for Gaelic learners in Scotland. For example, I have never seen such experiences acknowledged in the scenarios, dialogues, and other examples in Gaelic language textbooks and teaching materials. Unlike some other minority language situations (e.g., Cavanaugh Reference Cavanaugh2009), in Gaelic revitalization contexts the “adult learner” is usually assumed to be someone who has had no previous exposure to Gaelic in the home. However, of MacCaluim’s 392 survey respondents living in Scotland, 91 (or 23.2%) had at least one Gaelic-speaking parent, which he states is a much higher percentage than would be expected in the Scottish population as a whole (2007:148–49), and which suggests that adult children of Gaelic speakers who did not transmit the language to them are a significant constituency for Gaelic language-learning efforts. MacCaluim’s survey findings about respondents’ motivations to learn Gaelic are also suggestive of the same point: Respondents in Scotland gave a wide range of reasons for learning, but 16.1% rated as “very important” and 11.5% rated as “quite important” the motivation that “adult members of my family can/could speak Gaelic,” with 4.5% of the respondents in Scotland designating this in a separate response as their single “main reason for learning” (2007:158–9). Eliminating the “not applicable” respondents, MacCaluim further determined that 68.9% of respondents living in Scotland who claimed to have adult family members who can or could speak Gaelic rated this factor as either “very important” or “quite important” in their motivation for learning, and 53.6% of respondents who claimed to live in a Gaelic-speaking area rated this factor as either “very important” or “quite important” in their motivation for learning. In other words, MacCaluim found that “majorities of those living in Gaelic-speaking areas, [and] of those who have or had Gaelic-speaking members of their family … stated that these factors were important in their decision to learn the language” (2007:159–60). These facts could be usefully taken into account in language planning to support adult learners in the cause of revitalizing Gaelic-speaking residential areas.

Socialization of affect and ideology in the local context of language shift

The second ideological-affective mismatch concerns the discursive enactment of sociolinguistic boundaries at the local community level. The interviewees’ reports of their own and others’ linguistic behaviors, and the negative or ambivalent affective stances they took in their reports, show how these adult Gaelic learners were being socialized by some people in their Uist communities not to speak Gaelic in the community.

The ideological mismatch in this case is between “insiders” and “outsiders” in the local community context, who have been socialized into different sets of rules about the appropriate contexts for speaking Gaelic. Uist residents categorize people who settle in Uist as adults as “incomers,” a category opposed to “locals.” In theory these terms describe, respectively, people who have settled in the area as adults (or whose parents have), and people who were born in the area of at least one parent who was also born in the area (Burnett Reference Burnett1997; Macdonald Reference Macdonald1997:131–40). Throughout the Highlands, people assign sets of opposing values to these two categories: “Locals” are believed to belong to the area, to have roots and a history there, while “incomers” are believed not to belong to the area, to lack roots there, and to be “recent and fugitive” (Jedrej & Nuttall Reference Jedrej and Nuttall1996:94–95). In practice, the membership of each group is relative (Jedrej & Nuttall Reference Jedrej and Nuttall1996:173; Burnett Reference Burnett1997); for example, offspring of Uist people raised on the mainland of Scotland and who later settle in Uist do not exactly fit into either category; nor do people from other Hebridean islands who settle in Uist. However, the general equation of Gaelic with “local” and English with “incomer” is still prevalent among Gaelic speakers, and newcomers are socialized into it.

An accommodation norm involving judgments about the particular contexts in which it is appropriate to speak English or Gaelic plays a role in maintaining sociolinguistic boundaries between “incomers” and “locals” in Uist.Footnote 11 The central thesis of this norm can be formulated thus: It is rude to speak Gaelic to, or in the presence of, or within earshot of, a person who is not known to be a mother-tongue Gaelic speaker. Such accommodation norms have been documented in slightly differing forms in many European minority language situations, including the “ethic of politeness” observed by Trosset (Reference Trosset1986:68–82) among Welsh speakers, and the “etiquette of accommodation” observed by Woolard Reference Woolard1989 among middle-class Catalan speakers in Barcelona. The development of these practices is a result not only of the increased number of English monolinguals in Gaelic-speaking areas, but also of the historical shift in beliefs and behaviors of Gaelic-English bilinguals, as Susan Gal also noted for Hungarian-German bilinguals in an Austrian village:

But the presence of monolinguals in local inns and homes did not, it itself, revise linguistic etiquette. What has changed since the 1920s is not so much the pressure exerted by German monolinguals as the responses and conceptions of the bilinguals. They now acknowledge rather than resist the right of monolinguals to demand use of German in their presence.

(Gal Reference Gal1979:166)As Gal indicates, “the responses and conceptions of the bilinguals,” in other words their ideological-affective stances and behaviors, are the key factors in enacting this etiquette of accommodation.

This accommodation norm appears to have developed as a widespread social practice in Gaelic communities in Scotland by the second half of the 20th century. By the mid-1950s, a noted folklore collector in the Outer Hebrides stated that “Hebrideans nowadays always assume that the stranger is always English speaking” (MacLean 1956–Reference Maclean1957:26).Footnote 12 Dorian (Reference Dorian1981:79) noted that this etiquette of accommodation was “almost universally obeyed” in the 1970s among East Sutherland Gaelic speakers on the northeast coast of Scotland. The anthropologist Jack Coleman noted the operation of accommodation norms, which he termed the “Courtesy Rule,” in 1973 in Carloway, a Gaelic–English-speaking crofting township on the Isle of Lewis (Coleman Reference Coleman1975:79–84). One prominent Gaelic scholar from the Isle of Lewis observed flatly, “To behave otherwise is socially unacceptable” (Macaulay Reference Macaulay and Anderson1982:29). During the period of my fieldwork in 2000, a Uist woman in her sixties explained the norms to me in these terms:

(5) Och tha, well […] tha gu math mi– ((cleared throat)) ’se caran ill-mannered. Tha (e) gu math rude ma tha thu a’dol ( ) brudhinn Gàidhlig agus cuideigin ann nach eil a’tuigsinn Gàidhlig, tha mm... ah, chan eil e, chan eil e modhail idir (X4, #497).

‘Och yes, well […] it’s very im– ((cleared throat)) it’s somewhat ill-mannered. (It)’s very rude if you’re going ( ) to speak Gaelic and someone [is] there who doesn’t understand Gaelic, it’s mm… ah, it’s not, it’s not polite at all.’

Her use of the English expressions ill-mannered and rude in the midst of her Gaelic statement indexed the English position from which judgment is passed on Gaelic in this accommodation norm, while voicing and thus constituting an iconic performance of it.Footnote 13

Her codeswitching, together with the accommodation behavior more generally, indexed the defensive position of Gaelic-English bilinguals as a group in relationship to English and “monolingual” English speakers. This speaker has been socialized into a system of values in which English speakers hold the superior social and economic position and must always be accommodated. In Lewis in 1973, and in Uist a quarter-century later, locals were very aware that the rest of Britain thought of them as stupid peasants, and that Gaelic language use was considered symbolic of their bumpkin status (see also Cavanaugh Reference Cavanaugh2009:35–41, 55–62; Tsitsipis Reference Tsitsipis1981). Such views are expressed regularly in the Scottish press (McEwan-Fujita Reference McEwan-Fujita2003:159–231). Coleman argues that Gaelic speakers tried to protect themselves from judgments of this kind by avoiding the kinds of behaviors labeled as such, while in the presence of the labelers (Coleman Reference Coleman1975:78–79).

Coleman (1975:83) documented how Gaelic-English bilinguals were socialized into this system of behavior by parental instruction and example in the crofting township of Carloway on the Isle of Lewis. Such early socialization can be continually reinforced by unpleasant social encounters in school, and as adults in public and in the workplace. A Uist woman, “Flora,” told a story about her experience working in a local bank branch. Every other year, she said, the Scottish bank’s mainland headquarters sent a young and promising male trainee to the island branch to perform a thorough audit. On one of these occasions, the auditor expressed concern that the tellers’ use of Gaelic in the workplace might facilitate criminality:

He just suddenly thought, oh, do you not think they might be trying to rob you if they’re talking in Gaelic, you know, they might be trying to rob the place, y’kn– he was saying to the monitor and he tried to stop us speaking in Gaelic (Q1, #513).

Other similar anecdotes from people I talked to in the field indicate that on the mainland of Scotland as well, individuals speaking Gaelic with one another could be subject at any time to insults, directives to stop speaking Gaelic, and even physical violence from bystanders (cf. Gal Reference Gal1979:166; Dorian Reference Dorian1981:80). Judging from the relative infrequency of these accounts in my fieldnotes, such incidents may have been relatively rare in the past few decades. But they did occur, and even one incident could make a lasting impression and influence a person to significantly change his or her linguistic behavior. Part of the trauma of such incidents is that one never knows when or where they will happen, and they can happen when one least expects them.

Flora’s description of a workplace encounter with a customer whom she identified as an adult Gaelic learner demonstrates the impact that this socialization could have on the language “choice” of fluent Gaelic-English bilinguals. Flora described how she found herself on one occasion observing the etiquette of accommodation, despite her stated wishes to do otherwise:

(6) 1 Flora: There’s this day this lady came in [to the bank], and, she– I think– if I remember

2 rightly she was a doctor, I can’t remember where she was from. But ((pause))

3 maybe it’s just making an assumption when people come in the door, and, you’ve

4 seen the {people walk} (_), and you think, they’ll only have English

5 anyway, so, I don’t know whether it was that, that was on the brain but, this

6 particular lady had Gaelic. And she must have either, she must have learned the

7 language, and she was ((laughter started)) fairly proud of having I think, and she

8 was trying to talk to me in Gaelic, I couldn’t ((laughter ended)) really talk to her

9 in Gaelic, like, I couldn’t. My brain would just not (_) it, I was speaking

10 to her in English, all the time, didn’t matter what she said, I was... ((speech

11 dissolved in a laugh)). And I think, this is odd, you know. Because I knew fine,

12 what I– I was wanting to do, but I– ((pause))

13 EM: Which was to speak Gaelic?

14 Flora: Uh huh, but– it just didn’t happen. And she was almost out the door before I

15 could– before the brain just switched over and ((pause))

16 EM: You were able to?

17 Flora: Yeah.

18 EM: Was she mad?

19 Flora: No, she wasn’t, but she must have thought it really odd (#513).

Here Flora narrated the process of visually identifying and assessing a female bank customer before starting to speak to her.Footnote 14 She described making a determination of the customer as an outsider, by definition non-Gaelic-speaking, and speculated that this assessment influenced her brain to override her own will, making her unable to speak in Gaelic to the customer despite the customer’s repeated conversational turns in Gaelic. She described a conflict between her brain (lines 5, 9, and 15) and her will to speak Gaelic; slightly different from the Cartesian mind-body split, perhaps this is a modern anatomized version of the Christian “spirit is willing/flesh is weak” trope, with the part of the weak flesh played by the brain. At any rate, Flora’s pauses and laughter helped constitute an affective stance of puzzlement, embarrassment, and perhaps even distancing (McIntosh Reference McIntosh and Jaffe2009) toward her violated expectations of rational control over her own language choice. Flora had previously stated in our interview that she did not agree with the most extreme enactments of local accommodation norms. She gave me several examples of situations in which she had disagreed openly with other Gaelic-English bilinguals who felt it was rude to speak Gaelic in a particular situation. She was also open to being interviewed in Gaelic by me, and to speaking in Gaelic with me and other adult learners, as both Alison and I had observed.

Flora’s anecdote illustrates how this accommodation norm – this nexus of ideology and affect in the speaking body – could shape the behavior of first-language Gaelic-English bilingual speakers in Uist in their interactions with my interviewees. It could be described as a process in which the local Gaelic speakers (as experts) were socializing the novices into the local pattern of “English to strangers, Gaelic to locals.” At the same time, the bilingual experts were socializing the novices into an affective stance of fear and distrust of unknown speakers, and caution around sociolinguistic boundaries.Footnote 15

Most of the adult learner interviewees’ descriptions and explanations of speaking Gaelic – or not – to other people in the community were characterized by a negative affective stance. For example, I asked the interviewees a series of questions about whether there was anyone to whom they spoke regularly in Gaelic, and the circumstances under which they did speak to people in Gaelic in their daily lives. In describing their situations, four of the seven interviewees said that they did not speak Gaelic to people very often because of a lack of individual initiative, will, or courage. However, their complex affective stances indicate some dissonance with this explanation, as do their descriptions of negative social reactions from other community members that contributed to their situation of not being able to speak Gaelic, or others not speaking to them in Gaelic. This contradictory position signaled by affective stance, similar to Flora’s, shows how the local speakers’ etiquette of accommodation may have been gradually inculcated as an embodied affective-ideological rule of sociolinguistic interaction for these interviewees living in the Western Isles.

The best example of blaming lack of interaction in Gaelic on oneself is Jean (“I could, but I don’t”), whose responses I analyzed at length in the previous section as a “dance of disclosure” signaling an affective stance of shame about her failure to speak Gaelic. Jean’s family experience with Gaelic demonstrated how Gaelic was inaccessible to her despite her having been raised by two Gaelic-speaking parents. Jean’s workplace experience also shows how the sociolinguistic boundaries of Gaelic and English speaking invisibly criss-cross social space in bilingual areas. Jean worked in an office with a Gaelic-speaking secretary, where I interviewed her. Soon after the long excerpt quoted in the previous section, the telephone rang while I was asking her about the use of Gaelic in her workplace. We both paused and heard the secretary, “Katag,” in the room next door answer the phone in Gaelic and continue talking at length in Gaelic to the person at the other end of the line. Breaking our pause, Jean then volunteered to me, “I hear it a lot, Katag uses Gaelic all the time. I never have to ask her what she’s saying.” But a few moments later, when I tried to elicit further commentary on patterns of Gaelic use by other community members with her, I was again met with a terse reply:

(7) EM: Are there any people who greet you regularly in Gaelic, and then switch into English?

Jean: Yeah.

She volunteered no further comments on the topic and I did not want to press her, since I had already pressed her earlier. For Jean, it seems that Gaelic was always a little bit out of reach. With her parents on the mainland, she spoke but was not understood; in Uist she understood but did not speak.

When I asked “Who do you speak to regularly in Gaelic?” other interviewees gave similar replies. Alison replied “No one. I do have people that I could speak in Gaelic to, but they have trouble understanding me and it’s too much of an effort.” Isabel answered the question by referring to one particular person at a local organization and said “I do sometimes speak to him in Gaelic, I could do more if I put my mind to it” (D5, #428).

An energetic and animated woman in her fifties, whom I have already referred to as “Linda,” described in her responses not only self-blame, but also particular patterns of interaction with her neighbors that make her socialization experience clear. Early in our interview, Linda made the connection between the etiquette of accommodation and local norms of hospitality, but she still found it troubling that her efforts to speak Gaelic were rebuffed:

(8) 1 EM: What Gaelic lessons or classes have you taken?

2 […Discussion and clarification between EM and Linda followed…]

3 EM: Was it the beginners’ class?

4 Linda: Absolute. I had not a clue. We just thought, well here we are, in the Western Isles, and

5 the way to fit in is to have a go.

6 EM: Do you think it did help you to fit in?

7 Linda: No. I think we would have fitted in anyway. Yes. They’re nice friendly people that live

8 here. And if you’re nice and friendly in return, it doesn’t matter what language you speak.

9 Plus the fact that they’re so polite, they wouldn’t speak Gaelic in front of you anyway.

10 Which niggles a little bit. Because I wish they would. (X5, #544)

Linda’s response contains a parallel structure in which nice friendly people (locals) and nice and friendly in return (ego, the incomer) getting along contrasts with so polite, they wouldn’t speak Gaelic in front of you anyway (locals) and I wish they would (ego, the incomer), who conflict in their orientations to speaking Gaelic. The pauses before and after Which niggles a little bit dramatized her explicit complaint even as she minimized it with a little bit and niggles (‘to gnaw’, but its other meanings have connotations of minor and petty). Her affective stance enacted her ambivalence and uneasiness about the discrepancy between Uist natives’ standard of friendly and polite behavior, and her own desire as an incomer to be spoken to in Gaelic.

Linda immediately went on without prompting to give examples of encounters with her neighbors in Uist:

(9) For instance, one day I plucked up the courage. I was always willing to have a go in a class, but when I’m outside that’s different. The neighbor ((pointing out the window)) came down, and I said, Tha i breagha. With the proper enthusiasm. And he said, “That’s right.” ((laugh)) Even if he hadn’t understood it, I wanted a reply in Gaelic! {_} And I thought, it took me so much effort to do that. It’s a nice phrase, {_} And I said it to someone else, and he said, “Yes! And you’ve pronounced it correctly, with the emphasis in the right place!” {_} And I know, and thought, I know (X5, #544).

Linda had learned enough in her beginner Gaelic classes about Gaelic greetings to know how to produce the first pair-part of an appropriate greeting-greeting adjacency pair (Schegloff Reference Schegloff2007), with a comment about the weather, such as Tha i breagha ‘It’s beautiful’, using the locally appropriate feminine pronoun i to refer to the weather (which is masculine e in other dialect areas). She had also learned how to produce this phrase with a reasonably accurate approximation of Gaelic phonology, as her retelling indicated to me. She expected that an appropriate reply to her comment would have been a comment in Gaelic acknowledging or elaborating on her comment about the weather – something like Tha gu dearbh ‘Yes indeed’. Such a reply would have completed the adjacency pair of a typical Gaelic greeting.

Instead, in the first brief interaction Linda described, her neighbor violated the turn sequence of the greeting adjacency pair in two ways. First, he initiated a codeswitch from Gaelic to English in the middle of the pair, a switch which Linda implies continued for the remainder of the interaction. Second, he offered a dispreferred response, That’s right, which constituted an evaluation of her Gaelic use and shifted his footing in the conversation from that of an egalitarian neighbor to a hierarchical position of a teacher evaluating a pupil. Although the response also could be interpreted as an agreement with the truth value of her statement, the fact that the comment was an evaluation is made more clear by the codeswitch, and by comparison with her second conversation partner’s comment as reported by Linda. This contained an agreement with the truth value of her statement (Yes) and a separate evaluation of its technical execution (And you’ve pronounced it correctly...). Thus, this English evaluation response violated local Gaelic interactional norms of greeting, codeswitching, and egalitarian social footing (Ducey Reference Ducey1956; Parman Reference Parman1990).

When Linda spoke in Gaelic to her neighbor, she was attempting to “fit in” to the local community of Uist. Linda had moved into the area, bought a house that had previously been inhabited by a Gaelic speaker, and was learning to speak her neighbor’s stigmatized first language. He turned the greeting exchange into an evaluation of the “incomer” by the “local,” a switch to judgment by the very person who may have felt that he was usually being judged (see e.g. Hill Reference Hill1985). Through his meta-level comment on grammar, Linda’s neighbor dictated the choice of language, and the position from which to display superior knowledge. He created a conversational disjuncture that indexes a larger social disjuncture between participants who occupy the same geographical space but belong to different sociolinguistic communities with different criteria for membership, and radically different experiences of language socialization.

After relating this anecdote, Linda told me that she wanted a reply, not an evaluation, and looked sad (as I typed in my interview notes at the time). I then asked Linda, “Who do you speak to in Gaelic now? Is there anyone?” She answered:

(10) Well not really, because this one ((gesturing out the window to her neighbor)) will only answer me in English. Yeah! I can’t think of anyone really. I go into the shop at Drumbeg and try to get my courage up. But I don’t.

Linda’s explanation of her failure of courage and will, read in the context of her affective stance and her account of her neighbors’ behavior, shows how on some level she seems to be aware of the social nature of the problem. She is actually saying that she doesn’t have the courage to override local norms and local definitions of polite behavior – the courage to be rude by local standards. Blaming herself is a way of remaining humble, and avoiding explicit criticism of her neighbors and fellow community members, while commenting on the social situation.