I. Introduction

As the number and scope of international judicial bodies has risen dramatically in recent decades, so too has their influence on world politics. Today, over sixty quasi-judicial or dispute settlement bodies operate at either the global or regional level, including the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS), and the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU).Footnote 1 It therefore seems natural to ask whether and how these bodies’ greater involvement in global affairs transforms interstate relations. In particular, does the possibility of international judicial review change how states bargain out of court over a disputed issue that potentially falls under the court's jurisdiction? Much like in domestic legal systems—where the likelihood that potential litigants will reach agreement outside the courtroom is affected by both whether a court will hear their case and by their ability to predict how that court is likely to ruleFootnote 2—we propose that international courts cast a shadow that markedly changes potential litigants’ bargaining decisions.

Our argument is as follows. Rational potential litigants seek the best outcome possible for themselves and consider various dispute settlement mechanisms to achieve that goal. A judicial process offers one such mechanism. Yet it is not without costs—for example, it reduces their control over the dispute settlement process and outcome—and these costs may exceed those of alternative options, such as negotiation, conciliation, or mediation.Footnote 3 As the probability of these costs rises, litigants seek to minimize them—that is, they work to settle out of court.Footnote 4

The motivation and ability to settle a dispute, moreover, increases as litigants acquire information about which judicial body will hear their case. States often must first decideFootnote 5 or debateFootnote 6 where to apply for redress. If they disagree on the judicial body to use, then they need to sort this matter out first—either outside the judicial body (for example, in a compromis for ad hoc arbitration) or inside the body (for example, by contesting the body's jurisdiction). In contrast, if they agree on the acceptable body to hear their case (for example, when states apply to the ICJ under a special agreement), then no question about the body's jurisdiction arises. In some issue areas—for example, the law of the sea—states can make their preferences about acceptable judicial bodies known ex ante, meaning that if a case arises in that issue area and both states find a given judicial body acceptable, the likelihood rises that the acceptable body hears the case. The threat to “go to court,” in other words, crystallizes, and the disputants predict—admittedly, with some uncertainty—how the judicial body will rule.Footnote 7

As Richard Bilder has noted, “[T]he prospect of eventual judicial decision necessarily affects the way the parties think about the law. Inevitably, they will bargain and assess the value of various settlement proposals in terms of how they think a court will decide.”Footnote 8 In this way, as the threat to go to court grows, states increasingly bargain outside the judicial body through other dispute settlement mechanisms, such as negotiation or mediation. Through these alternative, non-judicial mechanisms, states not only minimize or avoid the material costs of litigation; they also can pursue a more favorable outcome than the one they expect the court to provide by retaining control over their dispute's settlement terms and benefiting from extralegal considerations. Because such incentives exist before and after cases are filed, the court's shadow both prevents the filing of some cases and influences the management of the cases that states do file.

To develop and evaluate the merits of this general argument, we focus on judicialization within the law of the sea regime, as embodied within the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).Footnote 9 UNCLOS creates elaborate dispute settlement procedures to address maritime disagreements between states parties. These states agree to eschew the use of military force and may choose among numerous peaceful techniques to manage their maritime disputes, including bilateral negotiations and conciliation.Footnote 10 Should these techniques be unavailable or fail, Article 287 identifies four compulsory and legally binding forums to assist the disputing states: (1) ITLOS; (2) the ICJ; (3) arbitration under Annex VII of UNCLOS; or (4) arbitration under Annex VIIIFootnote 11 of UNCLOS.Footnote 12

Annex VII arbitration serves as the default procedure. Yet the convention also allows states parties, a priori, both to specify whether they find each of the four compulsory forums acceptable for deciding their potential disputes and, among the options they find acceptable, to rank the order in which they prefer these forums to be used. States parties therefore not only make a general commitment to peaceful dispute settlement procedures (including Annex VII arbitration), but also can file optional declarations in support of particular judicial bodies. These latter declarations under Article 287 allow states parties to send two additional signals: (1) a greater general openness to judicial settlement (i.e., through a willingness to involve judicial bodies); and (2) a greater threat to take future law of the sea cases to a specific court—the ICJ, ITLOS, or both. The latter signal is the most important for present purposes.

Article 287 declarations almost always select a court, moving a dispute from default arbitration to adjudication—but only if both states’ declarations agree on which court to use. When that happens, the threat that the selected court hears the case in question grows. This portends the imposition of not only a binding settlement to the dispute, but also additional costs. Litigating states hold less control over their dispute's management and outcome in adjudication than in arbitration. The courts consequently cast a shadow, within which the disputing states know the court may hear the case, will rule if necessary, can often predict how it will rule, and can decide to settle the case before it does.

As of December 2020, 179 of 194 (or 92 percent of) states had signed UNCLOS, while 164 (or 92 percent of signatory) states ratified the convention. A small number of these states parties have active Article 287 declarations. Forty-seven (or 29 percent of) ratifying states recognize the jurisdiction of ITLOS, the ICJ, Annex VII arbitration, or Annex VIII arbitration for compulsory dispute settlement: thirty-nine states parties for ITLOS, twenty-eight for the ICJ, ten for Annex VII, and eleven for Annex VIII.Footnote 13

We argue that these declarations send signals that fundamentally change the bargaining behavior of the states parties that make them in three ways. First, these declarations increase the frequency with which states resort to bilateral negotiations and non-binding third party efforts (e.g., mediation or conciliation) to manage their maritime disagreements. They do so, we contend, mainly to avoid the costs of litigation and to obtain a more favorable outcome. Second, the declarations curtail the use of force. The right to submit a disagreement to a judicial body provides a way to alleviate the friction that an unresolved disagreement creates—a friction that might otherwise encourage states to use military force.Footnote 14 Indeed, military force often serves as a measure of “last resort,” something states use to demonstrate resolve, to bolster their bargaining position, or when other tools fail.Footnote 15 Adjudication supplies an alternative last outlet; by providing disputants with a final settlement, and through a process that does not allow military gains to prejudice adjudicated decisions, the advantages of using military force decline. Finally, fewer maritime disagreements will arise among declaring states parties in the first place, as these states parties signal a stronger commitment to the judicial processes that clarify potential areas of disagreement within UNCLOS.

We empirically evaluate the effects of UNCLOS on interstate maritime diplomatic conflicts with data from the Issue Correlates of War (ICOW) project.Footnote 16 ICOW identifies all contentious claims between 1900 and 2001 that involve maritime jurisdiction (e.g., the delimitation of Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) boundaries), resource, or access issues (e.g., fishing/oil extraction or navigational rights) between two or more countries.Footnote 17 These claims require that one state's official representative (i.e., a challenger) diplomatically contest—for example, by making a public statement—the status quo distribution of maritime disputes in a specific area over which another state (i.e., a target) exercises de facto control.Footnote 18 Law enforcement actions, such as the seizure of vessels operating illegally, consequently do not qualify as maritime claims, unless they occur within the context of a larger entitlement dispute.

Focusing on UNCLOS to investigate the shadow effects of judicialization offers four key advantages over studying these effects in other issue areas of international law. First, states frequently contest maritime areas, and international judicial bodies have a lengthy track record of involvement in these disputes. There are consequently a large number of disputes to analyze. Second, maritime claims are politically salient and carry a significant risk of both militarization and escalation, as recent tensions near the Spratly Islands or Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands illustrate.Footnote 19 These issues, in other words, merit global attention. Third, maritime claims concern entitlements to areas that states find valuable because of their sovereignty, resource, or strategic implications (e.g., control of straits). That value often reduces states’ willingness to resolve maritime disagreements through courts, making maritime claims an important area in which to examine the effects of potential judicial review on states’ out-of-court behavior. Finally, understanding the shadow effects of judicialization requires us to identify and analyze cases that never go to court. These cases prove difficult to locate in many contexts. Data on maritime claims, however—in the form of public statements by state representatives who contest maritime areas—provide us with the universe of potential cases. The data include, for example, clashes over maritime boundaries (e.g., the Gulf of Maine case), the legal status of rocks and islands (e.g., Venezuela's claim to Aves Island), historical maritime claims (e.g., the U.S.-Canadian disagreement over the Northwest Passage), fishing and other resources (e.g., the Fisheries Jurisdiction case), and navigational rights (e.g., the Corfu Strait case).Footnote 20 Binding conflict management occurs in only three percent of all peaceful efforts to resolve these potential cases. How the credible threat of going to court influences non-binding settlement attempts is much less understood.Footnote 21

Besides reporting its novel empirical findings and discussing their implications, this Article makes three additional contributions. First, it extends Mnookin and Kornhauser's famous analysis of domestic legal bargaining in the shadow of courts to the international level and finds support for it in that context.Footnote 22 When potential litigants gain greater certainty over whether and which court will hear their case, their out-of-court bargaining changes. Many analysts overlook such a possibility. By studying only the cases that come before the courts—largely, but not exclusively, due to data availability—they necessarily miss any effects the courts have on bargaining outside the courtroom. Second, our study exploits the issue-based approach to world politics to capture cases that never appear in court. This not only offers a more accurate test of judicial bodies’ shadow effects, but also demonstrates the wider applicability of the issue-based approach to studies of international law. Finally, the study explores the signaling effect of a specific, optional judicial commitment mechanism (Article 287 declarations) to investigate the effect of judicialization, thereby separating the effects of judicialization from the effects of legalization. As we explain, the subset of UNCLOS states parties that file such declarations indeed bargain differently, and our review of this subset reveals no obvious alternative explanation that accounts for both their declarations and their out-of-court behavior. We therefore conclude that international courts cast a shadow that fundamentally changes how states bargain over maritime issues outside the courtroom.

The remainder of the Article proceeds in five parts. Part II briefly summarizes the expansion of judicialization in world politics, as well as the debate about whether judicialization alters state behavior. Part III advances our theory about how judicialization changes interstate bargaining over maritime issues and derives a series of empirical hypotheses from the theory. Part IV outlines our empirical approach, which Part V subsequently employs to ascertain whether the evidence falsifies the theory's hypotheses. The latter Part also considers both the main potential criticisms of our theory and how the theory generalizes to other international judicial bodies. Finally, Part VI summarizes our main findings.

II. The Judicialization of International Relations: The Role of International Courts

The expanding number and scope of international courts reflects a broader trend toward greater institutionalization in world politics. Since the Napoleonic wars, states have signed thousands of treaties, many of which create informal (e.g., regimes) and formal (i.e., international organizations, or IGOs) institutions across a range of issue areas (e.g., preferential trade agreements, bilateral investment treaties, or military alliances). Many recently created courts are embedded within these treaties as an integral part of the regional or global institutions that the treaties establish. For example, the ICJ is embedded within the United Nations Charter; the Court of Justice of the European Union emerged from and evolves along with various European Union treaties; and ITLOS is an institution of UNCLOS. The presence of these courts not only mirrors and promotes greater legalization—that is, the growth of international legal constraints—but also deepens judicialization Footnote 23—that is, the proliferation of international courts, the enhanced jurisdictional purview of these courts, and therefore, the increasingly prominent role that they play.Footnote 24 Indeed, twenty-four international courts now have jurisdiction to adjudicateFootnote 25 interstate disputes.Footnote 26

The trend toward deeper judicialization has garnered attention only recently.Footnote 27 Scholars therefore continue to debate its merits, with particular interest in when and why states delegate authority to international courts. Optimists in the debate assert that recognizing the jurisdiction of international courts carries key benefits. Independent courts and tribunals can influence states’ foreign policy behavior directly (e.g., by resolving a disputed issue) and indirectly (e.g., bargaining in courts’ shadows). Although studied less frequently than direct effects, scholars repeatedly uncover indirect effects when studying institutions that establish compulsory jurisdiction for binding settlement, such as the ICJ, the World Trade Organization (WTO), or the International Criminal Court (ICC).Footnote 28 States that make optional clause declarations recognizing the jurisdiction of the ICJ, for example, are more likely to strike peaceful agreements to resolve interstate disputes outside the courtroom.Footnote 29 Similarly, the WTO's dispute settlement procedures encourage states to resolve their trade disputes without adjudication.Footnote 30 And research on the effects of the ICC reveals both that domestic human rights practices improve significantly within states that ratify the ICC (e.g., less torture and fewer extrajudicial killings) and that ICC indictments reduce mass atrocities in civil wars.Footnote 31

For optimists, delegating authority to international courts enhances the credibility of states’ institutional commitments, promotes cooperation within multilateral settings, mobilizes compliance constituencies, and helps detect and sanction non-compliance.Footnote 32 It can also reduce power asymmetries (occasionally, even giving standing to non-state actors), facilitate domestically unpopular agreements (i.e., absolves leaders of responsibility for concessions), and resolve coordination problems that involve factual or conventional ambiguities (e.g., border disputes)—with the adjudicator's judgment serving as “cheap talk” that clarifies existing conventions.Footnote 33 Through the last of these traits, international court case law influences the future behavior of actors in world politics.Footnote 34

The debate's pessimists, on the other hand, offer four reasons to be skeptical of international courts. First, powerful states only cede authority to international courts reluctantly, instead preferring bilateral negotiations or arbitral tribunals that give them greater control. Second, states deliberately restrict courts’ jurisdiction. They often elect either not to endorse optional compulsory jurisdiction clausesFootnote 35 or to place reservations on such clauses to preclude courts from hearing cases over highly salient issues. Third, international courts handle a small caseload, and these cases are costly to litigate.Footnote 36 Their effect will therefore be minimal and less efficient than other dispute settlement options. Finally, a multitude of courts with overlapping jurisdictions creates forum shopping behavior and (potentially) inconsistent legal decisions; mindful of this, states search for the forum in which they have the best chance of prevailing.Footnote 37

Both sides of the above debate share a central problem: they evaluate the efficacy of international judicial bodies through their direct actions. Such an approach sidelines potential selection effects, even though scholars know those selection effects exist. Posner and Yoo, for example, note that “states might settle their disputes in the shadow of an effective court because they can anticipate its judgment and compliance by the loser.”Footnote 38 Courts, in other words, exert not only direct effects but indirect effects as well. To fully comprehend judicialization, we must consider the shadow that courts cast and how this shadow influences interstate bargaining. If, as we argue, the commitments that states make under UNCLOS generally—or under Article 287 specifically—alter how they bargain over maritime issues, then we must theorize about how these commitments, and the judicial actors they reference, influence the bargaining process. That, in turn, demands that we consider the various alternatives available to states, including bilateral negotiations and non-binding third-party processes (such as mediation), alongside the judicial ones (e.g., arbitration or adjudication).Footnote 39

III. A Theory of UNCLOS Commitments and Interstate Bargaining

This Part begins with an overview of the dispute settlement provisions of UNCLOS. It next considers how states manage maritime claims in the absence of judicialization. Finally, it explains how the commitments that states parties make under UNCLOS, including their optional declarations under Article 287, influence the settlement of maritime disputes—both in and out of court.

A. An Overview of UNCLOS Dispute Settlement

States have engaged in maritime disputes for centuries. These claims initially hugged coastal states’ shorelines.Footnote 40 As technology advanced, however, states asserted more numerous and expansive maritime entitlements.Footnote 41 Amidst the multiplying, diverging claims, states worked toward an international consensus on the rights and obligations of both coastal and non-coastal states within various maritime zones. These efforts culminated in UNCLOS in 1982.Footnote 42 UNCLOS achieved much. Most importantly for this study, it set sharp limits to the territorial (12nm), contiguous (24nm), and exclusive economic zones (200nm); developed coastal and non-coastal states’ rights in these various zones; and established unique and comprehensive compulsory dispute settlement procedures.Footnote 43

Part XV of UNCLOS sets forth the dispute settlement procedures that interest us here.Footnote 44 Article 279 reaffirms states’ obligations under Articles 2(3), 33(1), and 51 of the UN Charter—namely, to resolve (maritime) disputes peacefullyFootnote 45—while Article 283 calls for an exchange of views among UNCLOS states parties involved in a maritime dispute.Footnote 46 Article 280 permits flexibility in the peaceful procedures states parties use to pursue a settlement.Footnote 47 Compulsory procedures, as Article 281 notes, kick in if states are unable to reach a settlement using non-compulsory methods.Footnote 48 Articles 281 and 282 recognize that the compulsory settlement process(es) envisioned under UNCLOS may arise through the obligations of states parties codified in other treaties;Footnote 49 it also clarifies that these non-UNCLOS obligations can take precedence over UNCLOS obligations.Footnote 50 Articles 284 to 286 then expand on the various conflict management tools available to states parties. Article 284, for example, discusses the use of conciliation,Footnote 51 and Article 286 explains the conditions under which the compulsory procedure applies.Footnote 52

Article 287 describes the compulsory dispute settlement procedure in greater detail. It provides states with the option to specify one or more of four mechanisms for deciding their future maritime disputes: (1) ITLOS;Footnote 53 (2) the ICJ; (3) Annex VII arbitration; or (4) Annex VIII arbitration.Footnote 54 If a state does not make a declaration under Article 287, or if two disputing states label different settlement forums acceptable, then the compulsory settlement procedure defaults to arbitration under Annex VII of UNCLOS.Footnote 55 If a state party does make such a declaration, it must do so before a maritime dispute arises. That declaration can indicate both which compulsory forum(s) it finds acceptable for deciding its future disputes, and should it find more than one forum acceptable, rank ordering its preferences over those acceptable forums. States may list a preference for more than one forum at each rank order. Nicaragua, for example, finds the ICJ acceptable, but no other forums; Canada ranks two distinct forums as an acceptable first preference, ITLOS and Annex VII arbitration; and Chile and Argentina both prefer ITLOS to operate first and Annex VIII arbitration to operate second.Footnote 56

Figure 1 summarizes the number and timing of states parties’ Article 287 declarations, both in the aggregate and across the four possible forums. ITLOS receives the strongest endorsement among states making such declarations; 24 percent of states parties (or thirty-nine) have filed Article 287 declarations designating a preference for this tribunal.Footnote 57 The ICJ proves only slightly less popular, particularly as a first preference (for preference orderings, see Tables A4–5, online appendix). Unlike with ITLOS, however, some states parties prefer ICJ involvement as a second or third best option. Finally, a select few states parties have filed Article 287 declarations in favor of arbitration under Annex VII (ten) or Annex VIII (eleven). The number of declarations has increased over time, especially since UNCLOS entered into force in 1994 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. States Parties and Their Declarations Under UNCLOS

Notes: (1) The Y-axis varies in each panel to highlight trends. (2) “Annex VII Only” refers to the frequency count we present, not declarations’ content. When states declare a preference for Annex VII (i.e., the default), they generally do so alongside other forums.

The various compulsory dispute settlement bodies acquire jurisdiction in three ways. The first originates through UNCLOS itself:

The ICJ, ITLOS, and Annex VII tribunals are all given broad jurisdiction under Article 288 to address (1) any dispute concerning the application or interpretation of the LOSC [Law of the Sea Convention] submitted consistently with Part XV and (2) any dispute concerning the interpretation or application of an international agreement related to the purposes of the LOSC submitted consistent with that agreement. … The jurisdiction of Annex VIII Special Arbitration … [deals] with disputes relating to (1) fisheries, (2) the protection and preservation of the marine environment, (3) marine scientific research, and (4) navigation, including pollution from vessels and by dumping.Footnote 58

In addition to UNCLOS, several other treaties have compromissory clauses that recognize the jurisdiction of ITLOS or the compulsory procedures in Part XV of the UNCLOS treaty—for example, the 1995 Agreement on the Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks, or the 2001 UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage.Footnote 59 Finally, ITLOS and the ICJ can obtain jurisdiction via a special agreement among disputing states.Footnote 60

Article 297 of UNCLOS circumscribes the types of disputes that the tribunals can hear.Footnote 61 Article 298 takes these exemptions one step further. It permits states parties the option to carve out three types of disputes from these compulsory jurisdiction procedures.Footnote 62 The first concerns maritime boundary cases—e.g., the delimitation of the territorial sea, EEZ, or continental shelf—as well as disputes involving historic bays and titles. Because delimitation disagreements frequently arise and, as with territorial disputes, states cede decision-making control over them reluctantly, such an exclusion is noteworthy. A second optional exemption covers disputes involving military activities. The South China Sea Arbitration tribunal, a dispute between the Philippines and China, referred to this exception, even though China did not specifically invoke it under Article 298(1)(b).Footnote 63 The third optional exemption provides that disputes being actively managed through the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) need not enter the compulsory process under UNCLOS, unless the UNSC stops managing them or funnels them into that process. Where a dispute is exempt from compulsory jurisdiction, UNCLOS encourages states to employ conciliation instead,Footnote 64 although Article 298 establishes a ratione temporis limitation to disputes that arise after UNCLOS enters into force.Footnote 65

The last panel of Figure 1 displays the number of states parties that have registered Article 298 declarations during the period 1982 to 2020. The number of these declarations has steadily climbed over time; roughly forty states parties have active Article 298 declarations as of December 31, 2020.Footnote 66 Their declarations most commonly exempt boundaries and historic bays (73 percent), followed by military activities (59 percent) and disputes with active UNSC involvement (46 percent).

B. Maritime Bargaining Without International Courts

This Section considers how states would negotiate maritime disputes in the absence of UNCLOS and its judicial processes. We envision a dyadic bargaining situation, in which two states consider challenging the status quo distribution of maritime entitlements within a specific geographic area. Many states, especially neighboring countries, delimit overlapping maritime areas through consensual agreements. Argentina and Uruguay, for example, do so through the Treaty of the Río de la Plata and its Maritime Limit, adopted in 1973.Footnote 67 Our analyses do not include these cases, but rather focus on bargaining situations in which one state diplomatically challenges the maritime claim that another state advances.Footnote 68

Figure 2 illustrates the ICOW Project's process for identifying and coding these competing maritime claims. This process has four stages. Stage 1 identifies the potential universe of cases in which a maritime dispute could theoretically and empirically arise—that is, instances in which a non-negligible possibility of a maritime dispute exists, even if the probability that such a dispute arises remains low. That universe relies on a list of dyads (or state-state pairs) that either (1) possess potentially overlapping maritime zones or (2) contain a major powerFootnote 69 paired with a coastal state.Footnote 70

Figure 2. The Maritime Claim Process

In Stage 2, official representatives of one state (i.e., the challenger) explicitly challenge another state's (i.e., the target's) maritime entitlements; ICOW labels this behavior as a “maritime claim.” If two states resolve their competing claims without issuing an official challenge to one another's entitlements (e.g., see the Argentina-Uruguay treaty, mentioned above), then no maritime claim exists. Only around 5 percent of all possible cases where a maritime diplomatic conflict could occur experience an actual maritime claim; the remainder do not. The maritime claims interest us here.

The competing jurisdictional claims of Canada and the United States over the Hecate Strait and the Dixon Entrance illustrate the onset of a maritime claim.Footnote 71 In 1903, the Alaska Boundary Tribunal established the “A-B line” that settled the Alaska-Canada boundary; yet differences remained about how to interpret the A-B line, specifically with respect to the maritime boundary.Footnote 72 Canada asserted that the A-B line constituted the international maritime boundary. The United States, in contrast, argued the boundary instead relied on the equidistance method, which would favor the United States by moving the boundary twelve miles south of the A-B line along most of its length.Footnote 73 Once Canada's official representatives explicitly challenged the status quo, and representatives of the United States affirmed their disagreement, an ICOW maritime claim began.Footnote 74

Once a maritime claim begins, states can employ myriad peaceful and militarized tools to manage—and hopefully, settle—the claim (Stage 3). They most often negotiate bilaterally, but also regularly seek third-party assistance via mediation or adjudication. Canada and the United States, for example, took a separate maritime claim case to the ICJ (e.g., the Gulf of Maine).Footnote 75 Finally, states occasionally use military force to pursue a maritime claim. In the disagreement over the Hecate Strait and Dixon Entrance, for example, militarization occurred in 1991 when a U.S. Coast Guard vessel boarded and seized a Canadian fishing boat in disputed waters.Footnote 76

Previous studies indicate that numerous factors determine the conditions under which states select among the various management options: the disputed issue's salience, the management history (e.g., whether and how often the involved states used militarized or peaceful tools to manage the issue previously), the relative capabilities (i.e., power) of the involved states, and whether states share membership in intergovernmental organizations.Footnote 77 A claim can stay in the management stage for an extended period; it leaves this stage only when the involved states conclusively resolve their diplomatic conflict over the maritime entitlements, whether through a peaceful agreement, the use of force, or one or both sides no longer pursuing a challenge (Stage 4).

In the absence of international courts or arbitral bodies, states use the various bargaining tools available on an ad hoc basis. Treaties and historical practices guide decision making, and customary law shapes the reasonableness of the claims advanced (e.g., Canada's claims about how to extend the A-B line).Footnote 78 Ad hoc bargaining has advantages, such as greater flexibility and control over the dispute's management and outcome; yet it can also be inefficient and produce inconsistent outcomes—problems that grow as the number of affected states rises.

The maritime regime displays such a trend. The post-World War II expansion of fishing fleets, trawling technology, and naval activities, along with ambiguities in the law of the sea, increased both the frequency and variability in states’ maritime claims (e.g., the limits beyond the customary, three-mile territorial sea). When faced with such complexities, states often institutionalize conflict management, agreeing to common rules and dispute resolution processes. The standardization required for institutionalization reduces the onset of new disagreements; common guidelines and parameters set focal points, thereby discouraging other proposals from arising. The dispute resolution process then funnels any disagreements that arise into a predetermined process, the outcome of which reinforces standardization.

Negotiations over maritime areas change significantly after institutionalization. In its absence, powerful states hold strong advantages in dispute management; they can strongarm adversaries when negotiating bilaterally, selecting a mediator, or determining the composition and rules of ad hoc arbitration panels.Footnote 79 For this reason, powerful states reluctantly agree to the judicial settlement of maritime claims when facing weaker opponents; courts promise to level the playing field between the strong and the weak.Footnote 80 Nevertheless, strong states see advantages in institutionalization, despite the possibility that it erodes their bargaining advantage. Customary international law evolves slowly. To lock in their preferences, major powers benefit from embedding those preferences in institutions like UNCLOS. They accept weaker positions in individual cases in exchange for the prospect of achieving longer-term foreign policy goals.

C. Legalization: UNCLOS Commitments and Maritime Claim Management

At the time UNCLOS negotiations began, coastal states had advanced incongruous claims to maritime areas, and the international community lacked a strong consensus about states’ rights and obligations regarding these entitlements. Two states negotiating a maritime boundary, for example, found little guidance in customary law about how to establish a baseline from which to measure the boundary or what general principles acceptably divide maritime areas. Earlier UN Conferences addressed some of the ambiguities and laid the groundwork for UNCLOS, which codifies a far-reaching, legalized bargain—one that encompasses numerous issues related to the world's oceans, and sets forth a balance of rights and obligations for both states parties and third parties.

Legalization of maritime law affects interstate bargaining in three potential ways.Footnote 81 First, it reduces the likelihood that maritime claims arise (Hypothesis 1). When a state ratifies UNCLOS, it accepts the convention's delimitation standards, definitions, rights, and obligations.Footnote 82 This coordination, around a limited set of focal points, reduces the likelihood that a state will raise new maritime claims. The likelihood of such claims will be especially low if it questions entitlements vis-à-vis another state party to UNCLOS, since both of the involved states will then be constrained by the convention's rules.Footnote 83

Figure 3 illustrates this expected pattern. The average number of maritime claims per state increased from 1900 to 1982, dropped somewhat between 1982 and 1994—after UNCLOS opened for signature, but had not yet entered into force—and then declined rapidly after 1994, when the convention entered into force.Footnote 84 Because states parties broadly agree about one another's rights and obligations, as well as how to define them, they have less need to challenge the status quo. Claims therefore begin to fall once consensus emerges and continue to fall as that consensus gains strength.Footnote 85

Figure 3. Issue Correlates of War (ICOW) Maritime Claims, 1900–2010

Second, legalization through UNCLOS reduces the likelihood that states use force (Hypothesis 2). Articles 279 and 280, along with state commitments under the UN Charter, create an obligation to manage disagreements peacefully. Moreover, with respect to maritime claims, UNCLOS facilitates interstate coordination, aligns state expectations, generates information about the competing claims (including viable alternatives), lengthens the shadow of the future, and increases the reputation costs for acting contrary to the consensus it embodies. Through these various mechanisms, we expect a state party to UNCLOS to eschew the use of military force, particularly when managing its maritime claims. The aversion to force will be strongest in claims involving two states parties, since both face the incentives noted above (i.e., decreased benefits and increased costs to using force). In this way, UNCLOS exerts an indirect effect on interstate bargaining, similar to international institutions generally or the other instruments of peaceful dispute management found in multilateral treaties.Footnote 86

Finally, legalization encourages states parties to employ binding dispute settlement mechanisms to manage their maritime disputes if other methods fail (Hypothesis 3). Articles 281 to 287 supply these commitments. The logic underlying this hypothesis mirrors that discussed above: when preferences diverge and UNCLOS cannot immediately converge them (i.e., a maritime claim exists, perhaps over a matter of lingering ambiguity), states parties have clearer expectations about how to proceed. Above all, they plan to use peaceful techniques and anticipate the other will do the same. If they fail to resolve the divergence on their own (i.e., through negotiations), a community of actors and institutions stands ready to assist them.Footnote 87 That community includes mediators, as well as judicial and arbitral bodies—the latter being especially valuable if the claimants seek to set a legal precedent for the wider international community.

D. Judicialization: International Courts and Maritime Conflict Management

The judicialization of the law of the sea—i.e., the delegation of authority to international courts and arbitral bodies to define the meaning of UNCLOSFootnote 88—also influences state behavior within the maritime regime. States parties to UNCLOS agree to compulsory judicial processes if other peaceful tools do not resolve their maritime claim. Beyond this general commitment, and the default procedures that accompany it (i.e., arbitration under Annex VII of the convention), states parties can make optional declarations about the judicial bodies they prefer to hear cases involving their future maritime claims. The vast majority of these declarations select ITLOS or the ICJ as the preferred body (see Figure 1).

Article 287 declarations function as signals that can influence bargaining. Under UNCLOS, Article 287 declarations provide a mechanism through which a state party signals its consent to use one or more judicial or arbitral forums to manage its maritime claims. When two states parties make identical declarations—for example, both indicate a preference only for ITLOS—the likelihood rises that the specified body will address their future disputes. As the “threat to go to court” gains credibility, bargaining behavior changes.

Before outlining the theoretical mechanism in greater detail, we digress briefly to discuss how judicialization under UNCLOS advances—both through case law and the prioritization of binding settlement in the convention's overall approach to maritime claim management. Case law offers one pathway through which judicialization deepens. Through case law, courts clarify legal ambiguities, demonstrate their authority, and build a record of how they decide the disputes that come before them. Several such rulings appeared well before states even contemplated UNCLOS. A 1909 Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) judgment, for example, fixed the disputed maritime boundary between Norway and Sweden (the Grisbådarna case), relying on Sweden's historical claims and lobster fishing activity in the disputed area.Footnote 89 In 1951, the ICJ likewise resolved a dispute between the United Kingdom and Norway over the latter's earlier claims to fishing zones that the British considered to be inconsistent with international law.Footnote 90 Similar judgments continued after the United Nations Conference(s) on the Law of the Sea began in 1958—and accelerated after UNCLOS opened for signature in 1982. To date, international judicial bodies have heard over seventy cases related to maritime issues (Tables A1–3, online Appendix), creating a rich body of case law on the law of the sea.

Case law casts a shadow over states’ out-of-court behavior in two distinct ways. First, it reduces uncertainty so that states bargain more efficiently and effectively.Footnote 91 Prior to UNCLOS, a broad range of bargaining outcomes existed and seemed plausible (i.e., competing focal points existed). Indeed, states claimed a wide range of entitlement limits (three to two hundred nautical miles) precisely because no obvious focal point existed without further interstate coordination.Footnote 92 Such a situation heightens uncertainty. As greater uncertainty infuses the bargaining process, the transaction costs of negotiation and litigation rise, advantaging those actors better able to bear the costs, such as major powers, or those whose positions more closely align with customary international law. Uncertainty also increases the likelihood that states will misestimate their respective legal positions, thereby prolonging or prematurely ending disagreements, altering the number of litigated cases, or changing the incentives for out-of-court settlement.

International courts confront uncertainty by hearing cases and generating case law that establishes or clarifies definitions, principles, rights, and obligations.Footnote 93 Courts facilitate, in other words, a common understanding of the facts (e.g., what constitutes an island) and how to choose among the multiple available focal points.Footnote 94 Indeed, when legal focal points emerge through a judicialized process, states use them to press for a peaceful resolution to their dispute, especially if those focal points legally advantage their substantive interests.Footnote 95

Courts also identify the party that violated the law and explain how and why the behavior constitutes a violation. Reducing uncertainty about what constitutes an illegal action increases the reputational costs for reneging on judgments and deters states that might behave similarly in the future. In so doing, ITLOS and the ICJ not only uphold the legal rules that comprise UNCLOS (i.e., legalization), but also create additional focal points on which future disputants’ expectations can converge (i.e., judicialization).Footnote 96 Importantly, these gaps are not trivial, as the case law on the law of the sea demonstrates.

Case law also has a second consequence for out-of-court bargaining: it enhances states’ ability to predict how a court will likely decide a future dispute. “States will prefer to submit matters to a tribunal or court when they can reasonably predict how a matter will be handled based on previous decisions.”Footnote 97 Through a court's decisions, (would-be) litigants peer into that court's reasoning—to understand not only the outcome (i.e., judgment), but also how the court reached it. This helps the (would-be) litigants bargain more successfully outside the courtroom, whether before filing a case or as a court considers it. Such an effect only exists, however, if the potential litigants know the court that will hear their case—a more likely circumstance within the maritime regime when each of the involved states has declared a preference for the same judicial forum through an Article 287 declaration. We develop this argument further below.

The North Sea Continental Shelf cases highlight case law's benefits.Footnote 98 The dispute arose between West Germany, Denmark, and the Netherlands after the discovery of oil in the North Sea in the 1960s. The Convention on the Continental Shelf, negotiated during the first United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, could not prevent such a disagreement, as it left uncertainty about how delimitation occurs in overlapping zones with concave coastlines.Footnote 99 Germany—a non-party to the convention—pushed for equity, rather than the convention's standard of equidistance from the shoreline, because it would receive little of the continental shelf under an equidistance rule. The ICJ determined that the equity principle applied. That decision paved the way for both a negotiated settlement between the involved states, additional interstate negotiations on the topic, and further articulation of delimitation rules in the case decisions that followed. It also informed (would-be) litigants about how the ICJ would reason in and decide similar, future cases.

UNCLOS goes beyond the ad hoc judicialization of specific cases, by placing adjudication and arbitration at the center of maritime dispute management. States admittedly have a wide range of non-peaceful (i.e., military) and peaceful tools available when managing maritime disputes, but the threat of court looms in the background. We use the term “threat” purposively here; although states frequently find court involvement beneficial, as when a state leader relies on a court for political cover against a domestically unpopular decision, judicial processes carry relatively greater costs than the alternative, peaceful tools available.Footnote 100 To go to court, states invest significant resources—in researching claims, writing legal documents, making arguments before the court, and maintaining the status quo (i.e., not prejudicing the case before the court); indeed, most court cases continue for multiple years. These costs incentivize rational states generally, as well as key subsets of particular states (e.g., weaker states, who might not be able to bear the costs), to avoid the courts if they can.Footnote 101

Even if states can afford to bear the transaction costs associated with litigation, they still often prefer to avoid it. States hold little influence over the judges involved in deciding a case, the established rules and procedures for hearing a case, the existing case law, and—as a result—the outcomes of judicial proceedings. Political leaders therefore seriously consider whether the state can obtain a better outcome without the court's involvement. Without invoking a binding process, the involved states need not accept a settlement against their individual wills (i.e., comply with an unpopular or undesirable judgmentFootnote 102); without legal principles and precedent bounding the settlement terms they consider, they gain flexibility in settlement design; and without a legal procedure to govern the settlement process, it moves at their desired pace—no slower, no faster.Footnote 103

Two additional conditions enhance the desire to avoid a binding settlement. First, as an issue's salience rises, states increasingly hesitate to permit court involvement. States expect a court to decide an issue with finality. For relatively more salient issues—e.g., maritime claims, which touch on issues of sovereignty, state security, and economic livelihood—concessions carry greater costs, whether material or psychological. States may therefore prefer no settlement to one they find suboptimal, especially if the latter might be forced upon them. Second, as the power disparity between the disputing states grows, the more powerful state will forestall court involvement. A more powerful state holds a bargaining advantage outside the courtroom. It also faces audience costs (i.e., domestic backlash) if it loses to a weaker adversary. After the ICJ awarded the Bakassi Peninsula to Cameroon, for example, Nigerians in the area protested against the judgment. The Nigerian government repressed the protesters to bring the situation back under control. Meanwhile, multilateral pressure pushed Nigeria—the stronger state—to comply with the court's judgment.Footnote 104

To minimize the various litigation costs outlined above, states prefer to reach agreement outside the courtroom.Footnote 105 Judicial and arbitral bodies under UNCLOS consequently influence the management of maritime claims in several ways. First, they offer a relatively costly tool as a method of last resort. That, in turn, encourages potential litigants to pursue other forms of peaceful, non-binding conflict management that allow them to retain greater control over the management of highly salient foreign policy issues and to avoid the costs of litigation. Potential litigants eschew violence, not only because UNCLOS discourages it, but also because they no longer need to use force as the method of last resort. The courts play that role.Footnote 106

A further judicialization mechanism arises through the signals that states can send via the process that UNCLOS creates. Besides establishing a new court to hear maritime disputes, Article 287 allows states to make optional declarations about the judicial bodies they prefer to hear any of their future maritime cases. These declarations represent an additional commitment to judicial processes under UNCLOS. We note though that only a minority of states parties (29 percent) to UNCLOS make such declarations.. This raises a puzzle. If sending signals about preferred judicial forums improves the chances for peaceful resolution, why do all states parties not make a declaration?

We argue that states use Article 287 declarations to signal their commitment to judicial processes—at least with respect to their maritime claims. Militarized interstate conflict has high costs (e.g., armaments, personnel, resources, deployments, or fatalities), so states have an incentive to use less costly, peaceful methods to manage their disputes instead. At the same time, they must avoid being unprepared for a military campaign that an adversary launches. This leads to parallel policies: a desire for diplomacy and a preparation for military conflict. In an anarchic system, adversaries find these latter preparations suspicious—not only for the policy dissonance, but also because they worry the other side holds a hidden intention to launch a surprise attack that will victimize them. Leaders consequently face a challenge—namely, how to convince others that their state desires peaceful conflict management, regardless of any ongoing military preparations or the incentive to use the military if the opportunity presents itself.

Ratification of UNCLOS offers a way to signal more benign intentions. Ratification indicates that a state generally accepts the peaceful management of maritime claims. Optional declarations under Article 287, however, act as an additional signaling device. Rather than simply accept the default compulsory procedure (i.e., Annex VII arbitration), declaring states commit to (a) particular, additional judicial forum(s) and push the default into the background. These additional forums typically give the declaring state less control over its dispute's management. In arbitration (e.g., the default process, under Annex VII), disputing states retain the ability to appoint (or agree upon) arbiters (e.g., at the PCA), determine logistics (e.g., where arbitration occurs), and (perhaps) limit the scope of the arbiters’ decision. The arbiters, in turn, control the process once set in motion. Thus, through appointing the arbiters, disputing states exercise some indirect control over their dispute's management. Adjudication removes that control. When, therefore, a state declares ITLOS or the ICJ as an acceptable forum to decide its maritime claims (under Article 287), a circumstance that covers the majority of declarations, it also indicates a willingness to cede greater control to judicial bodies than required under UNCLOS.

Declaring states also signal which judicial body will likely manage a dispute that arises. From a case law perspective, that signal perhaps carries less weight; the maritime regime, including its various judicial bodies, likely integrates case law across disparate judicial bodies. Nevertheless, uncertainty declines in the face of such a signal. An adversary involved in a maritime claim knows exactly which judicial forum a declaring state will try to use. If two states each declare a preference for the same judicial forum, the threat of that court's involvement rises. Being better able to anticipate the forum's involvement—as well as read the potential effects of that forum's composition, rules, procedures, and judgments, alongside case law generally—states anticipate how the court will rule. That anticipation incentivizes and guides bargaining outside the courtroom (i.e., a judicialization effect), above and behind what a general commitment to UNCLOS provides (i.e., a legalization effect).Footnote 107

We expect that Article 287 declarations alter interstate bargaining in three ways. First, they reduce the likelihood that two states experience maritime claims (Hypothesis 4). Identifying judicial bodies as “acceptable” necessarily implies that one embraces their involvement, reasoning, and case law. That case law clarifies ambiguities in maritime law, causing many (potential) sources of dispute to disappear—not merely for the litigants involved, but for future, potential litigants as well.

Second, Article 287 declarations decrease the use of military force (Hypothesis 5). In the international system, states often use military force as a measure of last resort, when other, less costly options prove insufficient. An Article 287 declaration not only reinforces (alongside joining UNCLOS) a general desire to use judicial bodies for this purpose instead, but also demonstrates a greater willingness to cede control over dispute management (e.g., swapping Annex VII arbitration for adjudication via ITLOS or the ICJ). This does not mean that states never use military force; rather, its use declines because a state has greater information about its adversary's type—namely, how strongly it prefers peaceful conflict management to force.

Finally, these optional declarations increase the use of non-binding conflict management tools (e.g., negotiation and mediation; Hypothesis 6). As we note above, because Article 287 declarations more credibly threaten the involvement of a specific judicial body—and one that requires them to cede greater control over their dispute's management—they provide a state with greater information about the adversary's type. At one level, this information concerns a preference for military versus peaceful management tools (see above). At another level, though, it concerns preferences over specific peaceful management tools.Footnote 108 A declaring state demonstrates a willingness to cede greater control to the courts and to invoke a specific court for that purpose. The threat of that court's involvement therefore rises, transforming a vaguer commitment with greater control into a more concrete commitment with less control. To avoid that possibility and the costs that accompany it, the involved states more frequently employ negotiation and mediation in the courts’ shadows—much as prosecutors and defense attorneys reach plea bargains in domestic courts, given the credible threat of a jury trial.

We expect the signal—and therefore, the above effects—to appear most prominently in situations where two states have made an ex ante Article 287 declaration in support of the same judicial body (e.g., both find the ICJ acceptable and prefer its involvement most). If two declaring states instead recognize different forums (i.e., a weaker judicialization signal)—or one or more state in the pair makes no Article 287 declaration (i.e., a weaker judicialization signal still)—then the default arbitration procedure applies (under Annex VII of UNCLOS). That default procedure signals a commitment to the compulsory settlement of maritime claims, too, meaning that states parties that make no Article 287 declaration should behave differently than states that have not ratified UNCLOS. Because the signal is weaker in such cases, however, we expect such states to bargain in the shadow of the courts less often than those with Article 287 declarations.

Data on maritime claim management supplies prima facie evidence consistent with our argument about the signaling effect of Article 287 declarations (see Table B12, online Appendix). In a given year, the probability that states use bilateral negotiations to address a maritime claim is 78 percent higher for states parties to UNCLOS with Article 287 declarations (probability = 0.16) than those without Article 287 declarations (probability = 0.09). No obvious alternative explains why the subset of declaring states would behave in such a way. We therefore conclude that it is plausible for Article 287 declarations to send signals that alter out-of-court bargaining behavior.

IV. Research Design

We test our theoretical argument empirically through three distinct logistic regression analyses, which examine the effects of UNCLOS legalization and judicialization from numerous angles. These analyses retain the key independent variables of interest, but vary with respect to the dependent variable, unit of analysis, and temporal domain.

The first analysis studies the effect of UNCLOS on ICOW maritime claims within politically relevant dyad-years during the period 1970–2001 (n = 23,737 dyad-years). A dyad-year takes snapshots of state-state pairings during each year of their joint existence (e.g., United States-Canada 1920, United States-Canada 1921, and so on). Politically relevant dyads capture only the state-state pairings in which members are (1) land contiguous, (2) separated by up to 250 miles of water, or (3) include at least one major state.Footnote 109 A maritime claim occurs when official representatives of two governments diplomatically contest the sovereignty or usage of a given maritime space.Footnote 110 As noted earlier, these claims constitute the population of maritime cases that could go to court. Our analyses employ the ICOW dataset on maritime claims in the Western Hemisphere, Europe, and the Middle East from 1900–2001, which records 143 dyadic maritime claims.Footnote 111

The second analysis examines the effect of UNCLOS on dyadic interstate conflict. It uses the politically relevant dyad-year during the period 1920–2001 as the unit of analysis (n = 70,511 dyad-years). We measure interstate conflict through the Correlates of War (COW) Project's Militarized Interstate Dispute (MID) dataset.Footnote 112 A MID occurs when one state threatens, displays, or uses force against another state. “Onset” dichotomously captures the dyad-year in which a MID begins (2.4 percent of the dyad-years).

The final analysis considers the effect of UNCLOS on the management of ICOW maritime claims. The unit of analysis here shifts to the ICOW claim-dyad-year during the period 1900–2001. For example, the U.S.-Canada claim involving the Hecate Strait and Dixon Entrance extends from 1920–2001 in the dataset (and remains unresolved as of the last year of the dataset). Thus, this claim adds eighty-two claim-dyad-years to the analysis. As noted earlier, claimants can use many peaceful techniques to manage their claim. A dichotomous variable first captures whether dyad members use any peaceful settlement attempt toward this goal in a given claim-dyad-year, including binding third-party assistance (e.g., adjudication or arbitration), non-binding third-party assistance (e.g., mediation, good offices, or conciliation), and bilateral negotiations. After this initial, aggregate analysis, we then study each technique subcomponent separately to understand the potential judicialization effects of UNCLOS better. Finally, because states can also use military force to manage their claim, we consider this possibility as well.Footnote 113 The second analysis (MID onset; see above) examines militarized disputes between politically relevant dyads, while the third analysis investigates only whether states use force to resolve their specific, diplomatic claims to maritime areas.

A. Independent Variables

Three sets of independent variables capture the legalization and judicialization characteristics of UNCLOS. The first set denotes dichotomously whether one or both dyad members signed UNCLOS (two distinct variables), and whether one or both dyad members ratified UNCLOS (another two distinct variables).Footnote 114 A second set entertains any broader systemic effects through two dichotomous variables that indicate whether the UNCLOS regime exists (1983 onward) and whether the UNCLOS regime is in force (1995 onward). The third set focuses on state declarations under Article 287 of UNCLOS. Dichotomous variables measure whether both (joint) states declare a preference that any disputes involving them be addressed by the International Court of Justice (ICJ 287 declaration), the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS 287 declaration), or Annex VIII (three distinct variables). These declarations, we argue, signal concrete commitments to judicial processes and provide more information about which judicial forum will hear (potential) future cases. States making multiple 287 declarations (one/both [states]) potentially send stronger signals of their commitment to judicial processes—a possibility we also consider (another distinct variable). Chile and Argentina, for example, recognize multiple acceptable forums under Article 287 during their claim to the Beagle Channel, and the data capture that characteristic. Finally, states that declare no preference(s) under Article 287 trigger the Annex VII default procedure; we consequently combine them with those making specific Annex VII declarations in a separate dichotomous measure: Annex VII default.Footnote 115

B. Control Variables

Each of our logistic regression models extends analyses presented in earlier published work. We build upon the models of claim onset, MID onset, and issue management that Lee and Mitchell, Mitchell and Powell, and Hensel, et al. respectively report.Footnote 116 Control variables for our models derive directly from these earlier studies and offer guidance about how our control variables should behave—an important consideration, since we wish to study unexplored shadow effects. Table B1 (online appendix) identifies each control variable, the form it takes, a brief description of its coding, and the source(s) from which it derives. Inclusion of these variables accounts for other factors that might influence the dependent variables of interest, such as military and economic power, relative capabilities, regime type (e.g., democracy), economic/security ties (e.g., alliances), and past conflicts/negotiations, Variation in temporal domain across our models derives from differences in the earlier studies.

V. Empirical Results

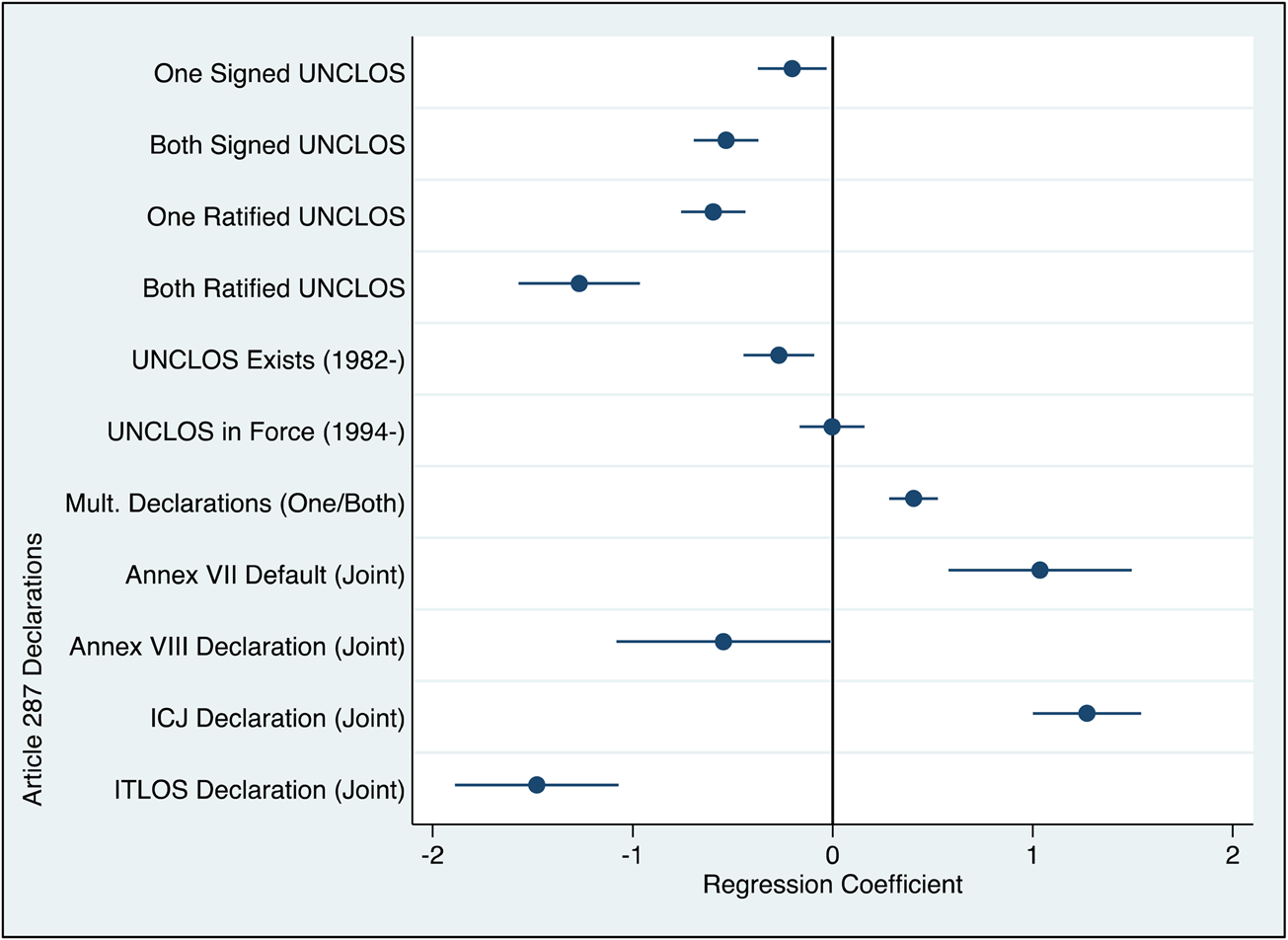

Does legalization through UNCLOS improve interstate cooperation over maritime issues? If so, we would expect—first and foremost—that UNCLOS reduces the likelihood that a dyad has maritime claims (see Figure 2 for the maritime claim process). Figures 4–5 consider this possibility and reveal strong evidence consistent with Hypothesis 1. Dyads containing at least one UNCLOS signatory or ratifying state are significantly less likely to have a maritime claim—compared to dyads where neither state belongs to UNCLOS (see the top four rows of Figure 4; both the plotted regression coefficient and its confidence interval lie fully to the left of the zero line in Figure 4, indicating a statistically significant, negative effect). Substantively, the probability of a maritime claim decreases from 0.081 to 0.067 when one state in a politically relevant dyad has signed UNCLOS (-21 percent), from 0.093 to 0.060 when both states have signed (-55 percent), from 0.085 to 0.051 when one state has ratified UNCLOS (-67 percent), and from 0.083 to 0.027 when both states have ratified the treaty (-207 percent; see the four upper-most row clusters in Figure 5). This is consistent with our argument that UNCLOS reduces new diplomatic conflicts by clarifying legal standards for maritime claims; in general, legalization improves interstate cooperation over maritime issues.

Figure 4. The Effects of UNCLOS on ICOW Maritime Claims, 1970–2001

Notes: (a) See Table B2 (online appendix) for full regression results. (b) See Figure B1 (online appendix) for a coefficient plot of control variables’ behavior. (c) Sample uses directed, politically relevant dyads, as defined by the Correlates of War Project's State System Membership data, supra note 13. (d) Time period ends in 2001 due to data availability. (e) Baseline model: Lee & Mitchell, note 91 infra.

Figure 5. The Substantive Effects of UNCLOS on ICOW Maritime Claims

Notes: (a) See Table B2, Models 1-4 (online appendix) for the underlying regression results (see also Figure 4). (b) The exact calculations underlying the plot appear in Table B6 (online appendix). These calculations alter the value of one variable of interest at a time, with the remaining variables held at their mean values.

The mere existence of UNCLOS (1983 onward) also brings a wider, systemic effect (row five, Figure 4); the likelihood of maritime claims is 25 percent lower when the UNCLOS regime exists (fifth row cluster, Figure 5).Footnote 117 These legalization effects—which admittedly vary in strength from weak (i.e., one state signing UNCLOS) to strong (i.e., two states ratifying UNCLOS)—result from UNCLOS decreasing uncertainty about distributive bargaining options (e.g., clarifying definitions and principles). If that argument has merit, then any systemic effects derive largely from the existence of UNCLOS, not necessarily whether it is in force (i.e., the number of states parties). Although the latter admittedly tracks the strength of consensus about UNCLOS provisions, the clarity that UNCLOS brings will reside largely with the document itself. Our results confirm this supposition. Once UNCLOS exists, the probability of maritime claims declines, but whether it is in force (1995 onward) carries no discernible effect (row six, Figure 4; sixth row cluster, Figure 5). Nevertheless, the results suggest that interstate behavior changes because of the legalization that accompanies UNCLOS; states experience fewer diplomatic maritime conflicts with neighboring states and major powers (i.e., politically relevant “others”), especially if both states are parties to UNCLOS.

We next consider whether UNCLOS influences general, dyadic conflict behavior to determine if states parties heed the calls for peaceful settlement found within the convention. Figures 6–7 investigate whether dyads with UNCLOS states parties engage in fewer militarized disputes than their non-state-party counterparts (Hypothesis 2). Consistent with our theory, the probability that a MID occurs is significantly lower in a politically relevant dyad if at least one dyad member has signed or ratified UNCLOS (see the top four rows of Figure 6). The probability of MID onset drops by 20 percent (0.024 to 0.020) if one state has ratified UNCLOS and by 50 percent (0.024 to 0.016) if both states have ratified UNCLOS (see the four upper-most row clusters in Figure 7). A broader, systemic effect exists here as well (see the fifth and sixth rows of Figure 6). The likelihood of MID onset significantly declines after UNCLOS both emerges (-9 percent) and enters into force (-14 percent; see the fifth and sixth row clusters of Figure 7). One might propose that these latter findings result from the waning of interstate conflict over time, Our statistical models, however, control for such a possibility, and we still observe this effect.Footnote 118 We therefore conclude that the observed effect attributes more to UNCLOS than any general, underlying temporal conflict trends.

Figure 6. The Effects of UNCLOS on Militarized Dispute Onset, 1920–2001

Notes: (a) See Table B3 (online appendix) for full regression results. (b) See Figure B2 (online appendix) for a coefficient plot of control variables’ behavior. (c) Sample uses politically relevant dyads, as defined by the Correlates of War Project's State System Membership data, supra note 13. (d) Time period ends in 2001 due to data availability. (e) Baseline model: Mitchell & Powell, supra note 29. (f) Because ITLOS joint declarations perfectly predict no militarized disputes, this characteristic does not appear in the model or the presented results.

Figure 7. The Substantive Effects of UNCLOS on Militarized Dispute Onset

Notes: (a) See Table B3, Models 1–4 (online appendix) for the underlying regression results (see also Figure 5). (b) The exact calculations underlying the plot appear in Table B7 (online appendix). These calculations alter the value of one variable of interest at a time, with the remaining variables held at their mean values.

Our next analysis investigates whether UNCLOS changes how states manage their maritime claims. In particular, we test whether UNCLOS encourages the use of peaceful conflict management in maritime claims, such as bilateral negotiations, mediation, or adjudication (Hypothesis 3). Figures 8–9 suggest that it does.Footnote 119 Dyads with an ongoing diplomatic maritime claim are 37 percent more likely to use peaceful conflict management in a given claim-year if at least one dyad member has signed UNCLOS, and 23 percent more likely to use peaceful settlement attempts if both dyad members have signed the convention (see the two upper-most row clusters in Figure 9; see also the top two rows of Figure 8). Whether dyad members ratify UNCLOS, in contrast, does not affect their maritime claim management (see rows three and four of Figure 8, in which the confidence interval crosses the zero line; see also the third and fourth row clusters of Figure 9). And, as elsewhere, systemic effects appear too. Peaceful conflict management increases 31 percent after UNCLOS opens for signature in 1982 and 62 percent after it enters into force in 1994 (see the fifth and sixth row clusters of Figure 9; see also the fifth and sixth rows of Figure 8). This suggests, once again, that UNCLOS casts a wide shadow over bargaining between states parties and not parties alike—a shadow that discourages maritime claims and militarized behavior, while encouraging peaceful conflict management.Footnote 120

Figure 8. The Effects of UNCLOS on Peaceful Attempts to Settle ICOW Maritime Claims, 1900–2001

Notes: (a) See Table B4 (online appendix) for full regression results. (b) See Figure B3 (online appendix) for a coefficient plot of control variables’ behavior. (c) Sample uses maritime claim dyad-years, as defined by the Issue Correlates of War Project. These analyses include the Americas and Europe. (d) Time period ends in 2001 due to data availability. (e) Baseline model: Hensel, et al., supra note 16.

Figure 9. The Substantive Effects of UNCLOS on Peaceful Attempts to Settle ICOW Maritime Claims

Notes: (a) See Table B4, Models 1–4 (online appendix) for the underlying regression results (see also Figure 6). (b) The exact calculations underlying the plot appear in Table B8 (online appendix). These calculations alter the value of one variable of interest at a time, with the remaining variables held at their mean values.

Beyond these legalization effects, does judicialization under UNCLOS influence interstate bargaining as well? We propose that such effects arise through (1) case law, (2) using courts later in the dispute management process (i.e., after some—but not necessarily all—other, peaceful conflict management strategies fail), and (3) Article 287 declarations. Prima facie evidence supports such a proposal. Case law in the maritime regime is rich and accelerates after UNCLOS. Appendices A1–A3 provide a complete listing of law of the sea court cases for the PCA, ICJ, and ITLOS; these judicial bodies have heard eighty-two (some pending) cases.Footnote 121 Moreover, the threat of binding settlement is real, particularly for states with Article 287 declarations. Since UNCLOS entered into force, six of the eight (or 75 percent of) PCA law of the sea cases arose through Annex VII; at least one state possessed an ex ante Article 287 declaration in six (75 percent) of these cases. Similarly, the ICJ heard nine law of the sea cases during this period, with another five pending. Eight of the cases it ruled on (89 percent) involved at least one party with an Article 287 declaration, while four of the five ongoing cases also do (80 percent). Finally, we note that states almost always comply with ICJ judgments in maritime cases.Footnote 122 All of this not only reflects the successful judicialization of the UNCLOS treaty, but also suggests the plausibility of the mechanisms we propose.

Our main interest lies with the third of these mechanisms, which signals a commitment to use specific judicial forums should a maritime claim arise. Theoretically, we expect pairs of countries with joint Article 287 declarations to have fewer maritime claims (Hypothesis 4), fewer militarized disputes (Hypothesis 5), and more frequent peaceful negotiations as they bargain in the shadow of the court (Hypothesis 6). Analysis of these expectations yields three broad conclusions. First, the prevalence of maritime claims varies by declaration type (see the final five rows of Figure 4). Maritime claims are 39 percent more likely when dyad members make multiple Article 287 declarations (0.072 to 0.100), 121 percent more likely when Annex VII applies (0.077 to 0.170), and 159 percent more likely when both state find the ICJ acceptable (0.076 to 0.197; see Figure 10). At first blush, this seems incongruous with our argument, which expects maritime claims to be rarer when Article 287 declarations exist (Hypothesis 4). Some Article 287 declarations correspond with that anticipated effect. Dyad members that both accept ITLOS see the likelihood of a new maritime claim fall 264 percent (0.080 to 0.22), while those accepting Annex VIII arbitration experience a 59 percent decline (0.078 to 0.049). These latter effects are heartening, since UNCLOS intended ITLOS to handle law of the sea disputes. But what then explains the positive effects? One potential answer involves uncertainty. As the default procedure, Annex VII sends a weak(er) signal, since states do not have to make an optional declaration to select it.Footnote 123 Multiple 287 declarations might likewise demonstrate a greater commitment to use judicial processes, but decrease certainty about which court will hear a (potential) case, thereby undermining the threat to go to court. Both, in other words, carry greater uncertainty than other declarations, and that uncertainty might theoretically erode any signaling mechanism—and therefore, any shadow effects that courts cast.

Figure 10. The Substantive Effects of UNCLOS Declarations on ICOW Maritime Claims

Notes: (a) See Table B2, Model 5 (online appendix) for the underlying regression results (see also Figure 4). (b) The exact calculations underlying the plot appear in Table B9 (online appendix). These calculations alter the value of one variable of interest at a time, with the remaining variables held at their mean values.

Our second finding is that Article 287 declarations often reduce dyadic conflict consistent with Hypothesis 5 (see the final five rows of Figure 6). Dyads with multiple declarations are 26 percent (0.024 to 0.019) less likely to begin militarized disputes (see Figure 11); those to which Annex VII applies are 380 percent (0.024 to 0.005) less likely to do so; and those whose members jointly accept ITLOS never experience a MID, which explains why the variable drops completely from the analysis. Recognition of ITLOS, in other words—a tribunal that UNCLOS established—impedes diplomatic maritime claims and reduces the odds that a militarized engagement erupts between states parties.

Figure 11. The Substantive Effects of UNCLOS Declarations on Militarized Dispute Onset

Notes: (a) See Table B3, Model 5 (online appendix) for the underlying regression results (see also Figure 5). (b) The exact calculations underlying the plot appear in Table B9 (online appendix). These calculations alter the value of one variable of interest at a time, with the remaining variables held at their mean values.

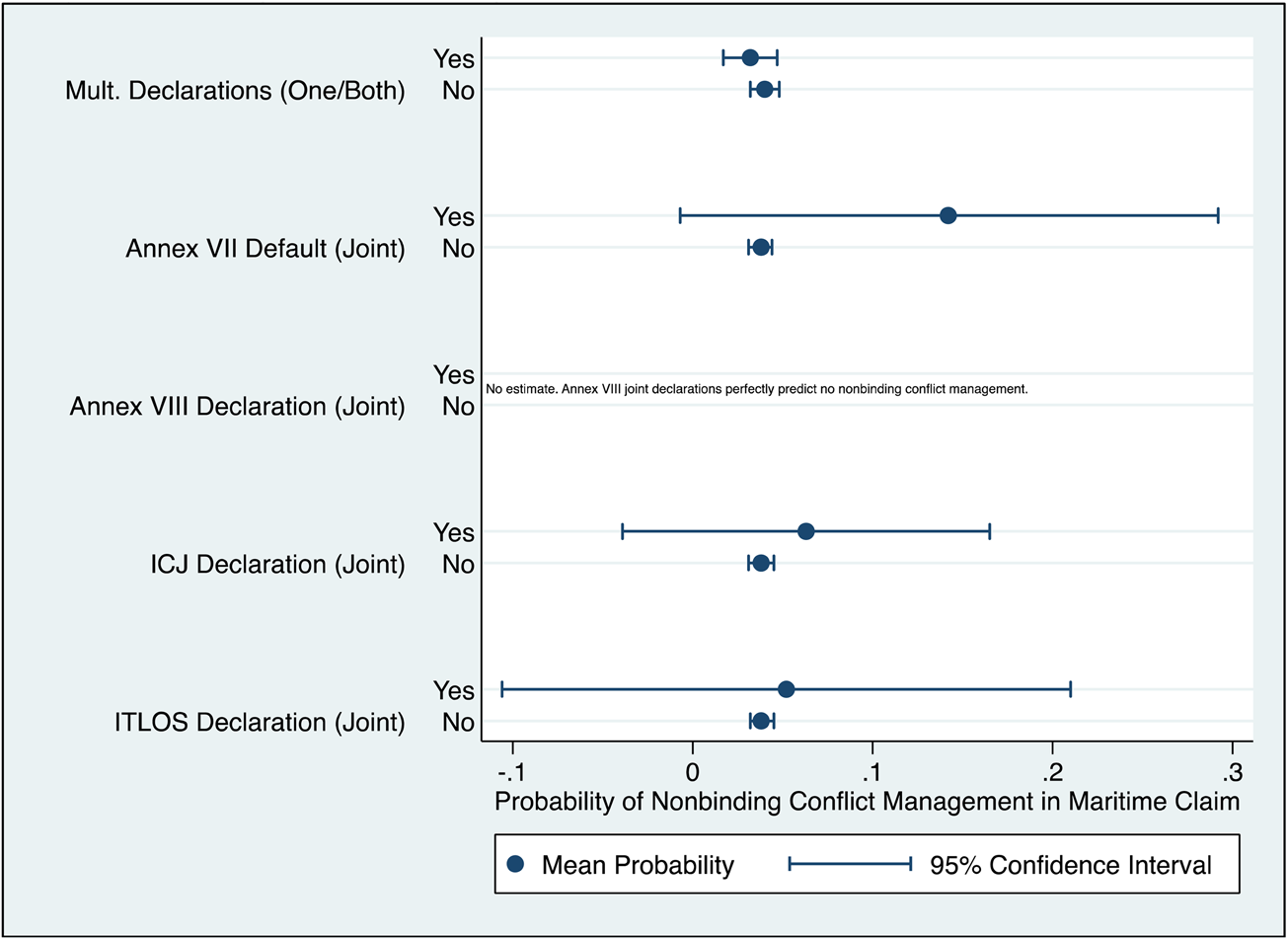

While these results support our hypothesis, we also see some surprising findings as well. Annex VIII declarations do not alter MID behavior, while joint acceptance of the ICJ significantly increases dyadic conflict by 163 percent (0.024 to 0.063). As with maritime claims, those making ICJ declarations behave uniquely—and contrary to our expectations.Footnote 124 Future research might investigate why this occurs in greater detail. Is it, for example, that variance around ICJ judgments—either in their terms or reasoning—is larger than that around ITLOS awards? If so, the shadow effects may be weaker around the ICJ (i.e., greater uncertainty exists) than around other bodies (e.g., ITLOS).