Introduction

People who have been exposed to a terrorist attack, their relatives, and the bereaved are at risk of developing mental health disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, depression, and suicide risk.Reference Whalley and Brewin1,Reference De Cauwer and Somville2 Five weeks and 12 weeks after the terrorist attacks in Madrid, Spain on March 11, 2004, 44.1% of respondents presented PTSD, 31.5% major depression, and 13.4% generalized anxiety disorder.Reference Gabriel, Ferrando and Cortón3 In addition to the symptoms experienced, a mental health disorder can also lead to difficulties at work,Reference Hansen, Berthelsen, Nissen and Heir4 changes in social and family relationshipsReference Neria, Olfson and Gameroff5 or in quality of life,Reference Jordan, Osahan and Li6 and poor physical health.Reference Jordan, Osahan and Li6

Following a terrorist attack, responses to a psychosocial disaster range from “low-intensity initiatives,” such as social support, psychological first aid, assessment, and psycho-education, to “high-intensity treatment,” such as trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy, or pharmacotherapy.Reference Reifels, Pietrantoni and Prati7 Some studies described post-disaster psychosocial services and planning across EuropeReference Witteveen, Bisson and Ajdukovic8,Reference Stene, Vuillermoz and Overmeire9 and developed guidelines for evidence-informed, post-disaster psychosocial management;Reference Bisson, Tavakoly and Witteveen10 however, little is known about the psychosocial support (PS) actually delivered after terrorist attacks.

In 2015-2016, France was faced with several terrorist attacks, with a first attack in January 2015, in several locations in the Paris region over a three-day period. Response from the French health care system was organized in three stages: immediate (first 48 hours), post-immediate (48 hours-one month), and after one month.Reference Auxéméry11 Since the 1995 terrorist attacks in France, the intervention of the medico-psychological emergency units (CUMP), constituted by permanent and volunteer health professionals (psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses), has provided psychological care in the immediate (defusing) and post-immediate (psychotherapeutic intervention) periods for people who have been exposed (survivors, witnesses, or close relatives [CRs]).Reference Prieto, Cheucle and Faure12,Reference Pirard, Baubet and Motreff13 After the post-immediate period (after one month), psychological care (deferred debriefing and psychotherapy) is provided by psychologists or psychiatrists in various private or public institutions, but without any specific organization.Reference Pirard, Baubet and Motreff13

The objectives of this study were: (1) to describe the prevalence or absence of PS in the aftermath of the January 2015 attacks among terror-exposed people; and (2) to describe factors associated with not receiving short-term PS among those with mental health disorders six months after the attacks.

Methods and Materials

Survey Design and Population

This study used data from a longitudinal survey known as IMPACTS (the French acronym for Investigation of Trauma Consequences in People Exposed to the January 2015 Terrorist Attacks and their Support and Mental Care), led by the French national public health agency (Santé Publique France) and the regional health agency (ARS Île-de-France), in order to assess the mental health, the psycho-somatic impact of the attacks, and PS among both civilians and first responders exposed to the January 2015 terrorist attacks. This survey was launched in two waves: six-to-ten months (Wave 1) and 18-22 months (Wave 2) after the attacks (from June to October 2015 and in 2016, respectively).

The design of the IMPACTS survey has been described elsewhere.Reference Vandentorren, Pirard and Sanna14,Reference Vuillermoz, Stene and Aubert15 The present paper only concerns the civilians. Civilians were persons listed either by the authorities or by CUMP volunteers as: (1) injured, a hostage, or a witness who had to flee the scene because their lives were threatened; 2) members of the editorial staff of the Charlie Hebdo magazine; (3) residents and workers within a 100m radius of the sites of the attacks; and (4) civilians identified by other victims through snowball sampling.Reference Heckathorn16

The inclusion criteria were: being aged 16 years or over and meeting one of the “A Criteria” for PTSD as set out in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (exposure to death, serious injury, directly or as a witness, or by learning that the traumatic event was experienced by a close family member or friend).17

The participants were interviewed face-to-face by trained trauma psychologists. Of the 489 people who responded to the inclusion questionnaire, 99 did not meet the inclusion criteria (20%). Of the remaining eligible 390, 105 declined to participate (27%) while 285 agreed they would participate in the longitudinal study (global agreement rate to participate in IMPACTS: 73%). Of the 285 who initially agreed to participate, 190 participated in Wave 1 (66.7%).

Psychological Support

In this study, 189 civilian participants were considered in Wave 1 of the IMPACTS survey who answered the question “Do you remember having received psychological support (psychological first aid or interview) by a professional or a volunteer? (yes/no).” This question from the IMPACTS survey was asked for the three periods: (1) 48 hours; (2) 48 hours to one week; and (3) more than one week after the event. The period “48 hours” corresponds to the immediate period, “48 hours-one week” corresponds to the early post-immediate period, and “more than one week” corresponds to the medium-term. The absence of short-term PS was explored for each period.

Independent Factors

In order to describe the factors associated with not receiving PS, first, variables that are classic factors reported in the literature to be associated with absence of PS - not necessarily following an attack or trauma - were selected: history of psychological disorders and care,Reference Stuber, Galea, Boscarino and Schlesinger18 history of traumatic or life-impacting situations, socio-economic conditions,Reference Stuber, Galea, Boscarino and Schlesinger18 and social support.Reference Ghuman, Brackbill, Stellman, Farfel and Cone19 Second, factors known in the literature to be specifically related to a “traumatic” situation such as the level of exposure (geographical, type, feelings) and the presence of peri-traumatic symptoms were studied.Reference Dyb, Jensen, Glad, Nygaard and Thoresen20,Reference Boscarino, Adams and Figley21

It also hypothesized that the factors associated with absence of PS varied with the time period. Initially, absence of support could be more related to the level of exposure to the attacks and peri-traumatic reactions (individuals who were less exposed and without peri-traumatic symptoms could receive less support than others), and over time, the characteristics related to background and social support could be linked to the absence of PS measures.

Sociodemographic Characteristics

The socio-demographic data included in the analysis concerned: gender, age, French origin (yes/no), educational level (higher or lower than high-school diploma), occupational status (employed/unemployed), and living with someone (yes/no).

Social Support and Isolation—The participants were asked about their current perceived social isolation (yes/no) and about current social support (the question was “If you were in need, would you be able to count on someone, either members of your household, other family members, friends or neighbors, colleagues, or the community, for: (1) moral or emotional support? (yes/no), (2) financial and material support? (yes/no), and (3) support in daily life? (yes/no)”).

Terror Exposure—Terror exposure during the terrorist attacks was measured using several indicators:

Physical Proximity with the Perpetrators: under 10 meters from terrorist(s), or more distant;

Type of Exposure: (1) directly threatened (DT) sustaining physical injuries, taken hostage, or present at the scene of the event and exposed to eye contact with/heard the voice of/talked with the terrorists, or saw a weapon pointed directly at them; (2) direct witness (DW) directly present at the scene during the attacks and saw/heard someone else being threatened/being injured/dying, saw blood or inert/dead bodies, touched injured/inert/dead bodies, smelled gunpowder; (3) indirect witness (IW) at home or working within a 100m radius of the events and not in the “directly/indirectly threatened” categories; or (4) close relatives (CRs) of those who were murdered, injured, or taken hostage; and

Perceived Terror Exposure: measured with the question “If you were close to a victim or present at or near the scene at the time of the event, on a scale of 0 to 10, how would you rate your feeling of exposure to the event?” The response scale ranged from zero (“I was not really exposed”) to ten (“I was one of the people who were the most exposed”).

History of Psychological Care and Traumatic Situations—The participants were asked if, before the event, they had been “followed by a general practitioner, a psychiatrist, a psychologist, or a psychotherapist for more than six months for a psychological problem” (yes/no).

For other potentially traumatic events, the participants were asked if they had experienced a “difficult situation” in the previous year (yes/no) and if they had experienced other “traumatic events in their life” (where they felt suddenly threatened or their life was in danger).

Peri-Traumatic Reactions—Peri-traumatic reactions were measured using the Shortness of Breath, Tremulousness, Racing Heart, and Sweating scale (STRS), which is a 13-item scale (scores ranging from zero to four) which provides a retrospective score for somatic manifestations of fear,Reference Bracha, Williams, Haynes, Kubany, Ralston and Yamashita22 and the Peritraumatic Dissociative Experience Questionnaire (PDEQ), which is a 10-item questionnaire (scores ranging from zero to four) which measures peri-traumatic dissociative symptoms.Reference Birmes, Brunet, Benoit, Defer, Hatton, Sztulman and Schmitt23 A score of 15 or more indicates a significant experience of dissociation.

Mental Health Disorders—Modules from the Mini-International Neuro-Psychiatric Interview V6 (MINI) questionnaire were used to assess PTSD in the last month, major depressive episode (current and past), and certain anxiety disorders (agoraphobia, social phobia, panic disorder, or general anxiety).Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier and Sheehan24

Statistical Analysis

Prevalence or absence of PS was studied in each of the three periods after the January 2015 terrorist attacks among participants with PTSD, depression, or anxiety. Given the hypothesis that early manifestations of PTSD could be more visible and detectable, and therefore better managed, statistical comparisons of the patterns of presence and absence of PS among people with depression and anxiety disorders, according to whether or not the participants also had PTSD, were conducted. Performed Chi-square tests (or Fisher’s exact tests when frequencies were low) were conducted to test this effect.

Factors associated with the absence of PS were explored among those with mental health disorders. Given the dynamics of the response from the French health care system (described above), three separate regression models were used for the different periods (the dependent variables were absence of support in the immediate, early post-immediate, and medium-term [yes/no]). A robust Poisson regression model was used to produce prevalence ratios.Reference Zou25 All the variables previously selected at P <.05 were included in final models for each of the three model.

All analyses were carried out using R statistical software Version 4.1.1 (R Core Team; R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria).

Ethics

The IMPACTS survey received approval from the Committee of Ethics and Deontology (CED) of Santé Publique France in 2015, from the French national data protection authority, (CNIL, No.915262), the French ethics committee for research (CPP, No.3283), and the French advisory committee on information processing of research material in the field of health (CCTIRS, No 150522B-31). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Among the participants in the IMPACTS survey (N = 189), the median age was 41 years (Table 1). There were 60.8% women, 6.9% were of non-French origin, and 69.7% had high school diplomas. At the time of the survey (six months after the attacks), 18.0% of the participants were unemployed and 24.3% were living alone. Concerning exposure to the terrorist attacks, 44.4% of the participants were under 10 meters from the site of the attacks, or very close, or in the next room. Consequently, 30.7% were directly exposed to the events, 42.9% indirectly threatened, 19.0% were witnesses, and 7.4% were CRs of somebody who had been DT.

Table 1. Description of the Socio-Demographics, Terror Exposure, Mental Health, and Psychological Support among the Participants in the IMPACTS Survey, France 2015 (n=189)

Abbreviations: PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; IMPACTS, French acronym for Investigation of Trauma Consequences in People Exposed to the January 2015 Terrorist Attacks and their Support and Mental Care.

Among the 189 participants, 88 (46.6%) did not receive PS immediately after the attacks, 86 (45.5%) did not receive PS in the early post-immediate period after the attacks, and 102 (54.5%) did not receive PS in the medium-term. In all, 46 (24.3%) did not receive PS at any time (Table 1).

Absence of Short-Term Psychological Support and Mental Health

Among the participants presenting PTSD (n = 34), depression (n = 74), or anxiety (n = 59) six to nine months after the terrorist attacks, 9%, 18%, and 12%, respectively, had not received PS (data not shown).

Among the participants with depression at six to nine months (n = 74), the absence of PS in the medium-term was higher among those who did not present PTSD (54%) than among those who did (19%; P = .007; Figure 1). Among the participants with anxiety disorders at six to nine months (n = 59), the absence of PS in the medium-term was higher among those who did not have PTSD (63%) than among those who did (13%; P <.001). There was no significant difference between the immediate and early post-immediate periods.

Figure 1. Absence of Psychological Support in the Immediate, Early Post-Immediate, and Medium-Term Periods after the January 2015 Terrorist Attacks among Individuals Presenting at least One Disorder (PTSD, Depression, Anxiety Disorders), n = 105, IMPACTS Survey, France 2015.

Abbreviations: PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; IMPACTS, French acronym for Investigation of Trauma Consequences in People Exposed to the January 2015 Terrorist Attacks and their Support and Mental Care.

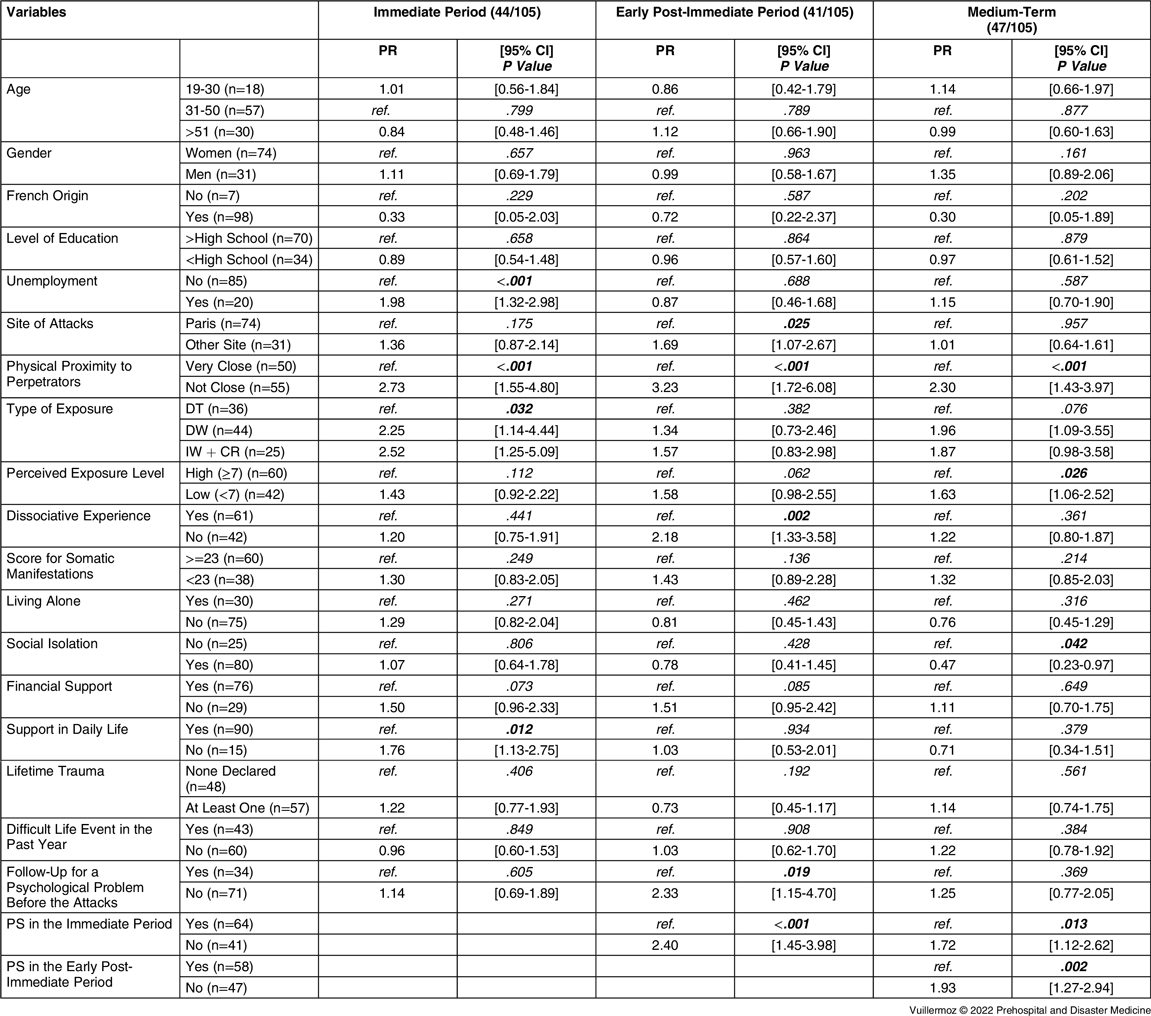

Univariate Analysis of Factors Associated with Absence of Short-Term Psychological Support

The absence of immediate PS (<48 hours) was associated with unemployment (prevalence ratio [PR] = 1.98; 95% [confidence interval] CI, 1.32-2.98); being not very close to the attack sites (PR = 2.73; 95% CI, 1.55-4.80); being a DW (PR = 2.25; 95% CI, 1.14-4.44); being an IW or a CR (PR = 2.52; 95% CI, 1.25-5.09) rather than DT; and not having support in daily life (PR = 1.76; 95% CI, 1.13-2.75; Table 2).

Table 2. Univariate Analysis of Factors Associated with Absence of Psychological Support in the Immediate, Early Post-Immediate, and Medium-Term Periods after the January 2015 Terrorist Attacks among Individuals Presenting at least One Disorder (PTSD, Depression, Anxiety Disorders), n = 105, IMPACTS Survey, France 2015

Abbreviations: DT, directly threatened; DW, direct witness; IW, indirect witness; CR, close relatives, PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; IMPACTS, French acronym for Investigation of Trauma Consequences in People Exposed to the January 2015 Terrorist Attacks and their Support and Mental Care; PR, prevalence ratio; CI, confidence interval.

The absence of early post-immediate PS (48 hours – one week) was associated with having been in a site other than the one in Paris (PR = 1.69; 95% CI, 1.07-2.67); not being very close to the attack sites (PR = 3.23; 95% CI, 1.72-6.08); not having a significant dissociative experience (PR = 2.18; 95% CI, 1.33-3.58); having medical follow-up for a psychological problem before the attacks (PR = 2.33; 95% CI, 1.15-4.70); and the absence of immediate PS (PR = 2.40; 95% CI, 1.45-3.98).

The absence of PS in the medium-term was associated with not being very close to the attack sites (PR = 2.30; 95% CI, 1.43-3.97); a low level of perceived exposure (PR = 1.63; 95% CI, 1.06-2.52); absence of immediate PS (PR = 1.72; 95% CI, 1.12-2.62); and absence of early post-immediate PS (PR = 1.93; 95% CI, 1.27-2.94). It was also inversely associated with perceived social isolation (PR = 0.47; 95% CI, 0.23-0.97).

Multivariate Analysis of Factors Associated with Absence of Short-Term Psychological Support

All the variables reaching P <.05 in univariate analysis were included in the multivariate models.

The absence of immediate PS (48 hours) remained associated with not being very close to the attack sites (PR = 2.50; 95% CI, 1.41-4.43); being a DW (PR = 2.07; 95% CI, 1.13-3.78) rather than being DT; and not having support in daily life (PR = 1.72; 95% CI, 1.18-2.52; Table 3). The association with unemployment was no longer significant (P = .069).

Table 3. Multivariate Analysis of Factors Associated with Absence of Psychological Support in the Immediate, Early Post-Immediate, and Medium-Term Periods after the Terrorist Attacks among Individuals Presenting at least One Disorder (PTSD, Depression, Anxiety Disorders), n = 105, IMPACTS Survey, France 2015

Note: Empty cells indicate that the variable was not included in the final model.

Abbreviations: DT, directly threatened; DW, direct witness; IW, indirect witness; CR, close relatives, PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; IMPACTS, French acronym for Investigation of Trauma Consequences in People Exposed to the January 2015 Terrorist Attacks and their Support and Mental Care; PR, prevalence ratio; CI, confidence interval.

The absence of early post-immediate PS (48 hours – one week) was associated with not being very close to the attack sites (PR = 2.46; 95% CI, 1.13-5.33); not having a dissociative experience (PR = 1.73; 95% CI, 1.11-2.72); and having follow-up for a psychological problem before the attacks (PR = 2.34; 95% CI, 1.15-4.38). The absence of early post-immediate PS was no longer associated with having been in a site other than the one in Paris (P = .191) and with the absence of immediate PS (P = .107).

The absence of PS in the medium-term was associated with not being very close to the attack sites (PR = 2.30; 95% CI, 1.43-3.97) and inversely associated with perceived social isolation (PR = 0.47; 95% CI, 0.23-0.97). The associations with perceived exposure, the absence of immediate PS, and the absence of early post-immediate PS were not significant (respectively, P = .216; P = .275; and P = .331).

Discussion

This study describes the prevalence or the absence of PS provided in the short-/medium-term after the Paris terrorist attacks among exposed people, and the factors associated with the absence of PS among those presenting mental health disorders six months after the attacks.

The absence of PS was more marked in the longer-term than immediately after the events (46.6% to 54.5%). This study indicates that the absence of PS was more frequent for people who did not have a disorder (at the time of the survey) than for people who did. This finding is expected: people presenting symptoms received PS. In addition, the study indicates that the absence of support the in long-term was significantly more frequent among people with depression or anxiety disorder without PTSD than among people with depression or anxiety disorder with PTSD. This result could be explained by a greater “visibility” of PTSD symptoms than those of depression or anxiety, and also by the fact that, after a traumatic event, PTSD symptoms tend to occur before symptoms of depression or anxiety disorders. Thus, these initial descriptive results suggest that PS should be provided in a “proactive” way, in the long-term, with tools enabling better early detection of depressive symptoms or anxiety disorders. In the public health/ESPA survey among civilians exposed to the November 13th attacks in France, the prevalence of PS within six months was higher among people with PTSD (89%) than among those with anxiety symptoms (57%) or depressive symptoms (79%) but no PTSD.Reference Pirard, Baubet and Motreff13

In order to improve knowledge on mental health care for people who are exposed to a terrorist attack and who have a mental health disorder, this study also investigated the factors associated with the absence of PS in the three critical periods with at least one mental health disorder.

First of all, in each period studied, the absence of PS was significantly more frequent among people who were close to the perpetrators. Similarly, in the immediate period, the type of exposure was significantly associated with provision of PS: witnesses received less support than those who were DT since the first responders probably provided more support to those who were DT. These “dose-response” effects of exposure in relation to provision of PS are well-known observations in the literature.Reference Boscarino, Adams and Figley26–Reference Boscarino, Adams, Stuber and Galea28 Although there is also a dose-effect of exposure on the development of symptoms, it is nonetheless true that people who are considered less exposed can also develop disorders and should therefore also receive PS.Reference Holman and Silver29,Reference MacGeorge, Samter, Feng, Gillihan and Graves30

The site of the attacks and individually perceived exposure did not remain significantly associated with absence of PS in the multivariate model (in the early post-immediate period and in the medium-term). This could be due to the sample size, or to the fact that absence of PS in the early post-immediate period may have been significantly more marked among people exposed to attacks at sites other than Paris, which could be explained by greater availability of care in Paris than outside (given that post-immediate PS is provided in particular by hospitals).

In the literature, it is well-known that people who have social support are more willing to access health care.Reference Ghuman, Brackbill, Stellman, Farfel and Cone19,Reference Van Overmeire, Muysewinkel, Van Keer, Vesentini and Bilsen31 Along these lines, this study indicates that the absence of PS in the immediate period was more likely among those who reported not being able to count on someone to help with daily life. Conversely, the absence of PS in the medium-term was significantly more marked among those who did not feel socially isolated. Since the participants in the survey were more likely to be in a socially advantaged situation, it is plausible that, in the medium-term, people who felt supported by their family of friendly networks would resort to PS less than those who did not.

Two other interesting factors were associated with the absence of PS in the early post-immediate period. First, these results indicate that people with no reaction of peri-traumatic dissociation are less likely to have PS, which is an expected result.Reference Boscarino, Adams, Stuber and Galea28 Second, not having previous follow-up for a psychological disorder is associated with a greater prevalence of absence of PS. This result is also expected because it is known in the literature that people with previous experiences of psychological care are more willing to have a further experience of psychological care.Reference Stuber, Galea, Boscarino and Schlesinger18 This association was not retrieved in the other two periods. People who have psychological follow-up are more likely to be cared for by hospitals or in community practices rather than by terror victim associations.

In this study, certain classic associations were not found between social determinants and PS, such as age, gender, educational level, country of birth, or relationship status. This absence of effect of social inequalities could be due to the homogeneity of the social situation of the population studied.

Like Allsopp,Reference Allsopp, Brewin and Barrett32 this study recommends that efforts should be made to reach out to people who scatter after the event and be more proactive in identifying and accessing those who need support. Finally, given (1) the suggested role of PS in enhancing acceptance of psychological follow-up,Reference Motreff, Pirard and Vuillermoz33 and (2) the fact that absence of social support could have a negative impact,Reference Kelly, Jorm and Kitchener34,Reference Charuvastra and Cloitre35 future research needs to focus on the quality and the type of PS liable to increase the likelihood of remaining in a continuum of care for the populations in need.

Limitations/Strengths

This study presents some limitations. The major limitation was the cross-sectional design and the fact that only report data were available, and it could not exclude the possibility that some of the data were subject to recall or reporting bias concerning PS, specifically in the immediate and early post-immediate periods. Second, another limitation was that the small number of participants could compromise the significance of certain associations. Third, the data reflected the socioeconomic situation at the time the participants were interviewed and it hypothesized that the participants would have the same perception of their social support/isolation as at the time of the attacks. Fourth, the comparability of the results is limited: most studies have focused more on mental health care than on PS.Reference North and Pfefferbaum36

This study includes some strengths. The first strength of this study was that the participants in the survey included both people who were directly exposed and CRs. Second, validated scales were used to screen for the main mental disorders. Third, the data were collected for three different periods in order to better describe the reality of care received. Fourth, the IMPACTS survey contains extensive data on the types of exposure and on social support, which are rarely described in surveys on mental health care in the aftermath of terrorist attacks, enabling a refinement of the results.

Conclusion

Some people with mental health disorders at six months did not receive PS after the terrorist attacks, although this could have prevented the development of symptoms.Reference Prieto, Cheucle and Faure12 Among those who had a mental health disorder six months after the attacks, factors associated with the absence of PS were mainly linked to exposure to the event, particularly for physical proximity with the perpetrators, and to social support. These results suggest that the role of social support could change over time and also suggest that the rapid dispersion of the people present at the event could have prevented support for the individuals who were more distant from the site.

Conflicts of interest/funding

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The IMPACTS survey was financially funded by the “Foundation d’Aide aux Victimes” and was coordinated by Santé Publique France and the Greater Paris Regional Health Agency (ARS-IdF). The work of CV and LES was funded by the Research Council of Norway, grant number 288321. The funding bodies had no role in the design of the study, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data, and writing the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors are most grateful to all the study participants for their involvement, especially given the very difficult context for them, and to all the interviewers. The authors would like to acknowledge the support from the national French agency for public health as well as the regional agency for health of Paris area: Anne Gallay, Thierry Cardoso, Anne Laporte, Jean Claude Desenclos, Clothilde Hachin, Naine Isserlis, Michel Gentile, Laurent Kosorotoff, Martial Mettendorf, Claude Evin, and François Bourdillon for generously contributing their time and energy to the conduct of IMPACTS study. A special thanks to Laurent Bernard-Brunel, Alexandra Botero, Jean-Michel Coq, Nathalie Cholin, Nicolas Dantchev, Elise Neff, Marc Grohens, Aurelia Rochedreux, Toufik Selma, Laure Zeltner, and Julien Sonnesi for their field investigation. The authors wish to thank the members of the scientific committee of the study. They also wish to thank Sarah Verdier Leyshon and Angela Swaine Verdier for their careful reading of the final manuscript.