In early January 2020, when Chinese theatre director Wang Chong (b. 1982) arrived in New York to remount his production of Nick Payne's Constellations for the Public Theater's Under the Radar Festival, he couldn't have predicted that this would be the last time for months that he would watch his actors from the middle of a full house. By the time his work-in-progress solo show, Made in China 2.0, opened at the Asia TOPA Festival in Melbourne, Australia, at the end of that February, it was clear that there would be no live theatre in Wang's hometown of Beijing for some time. All of China was on lockdown as the disease now tragically familiar as COVID-19 swept the country. Then, as Wang returned to Beijing in early March, businesses around the globe were shuttering, theatres were going dark, and theatre artists were confronting an unprecedented challenge to their personal safety, livelihoods, and ability to make meaningful art. In short order, some well-resourced theatre institutions began to stream performance recordings and reconfigure their seasons for online platforms. Only a month after returning home, Wang Chong joined this mass online movement with his production of Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot, streamed live on 5–6 April 2020 as Dengdai Geduo.

The production was, in many ways, characteristic of Wang's directorial approach: a radical reworking of a canonical play that transposed it across cultures and mediums, with the politically provocative twist of visual references to China's pandemic response. The artistic director of the Beijing-based theatre company Théâtre du Rêve Expérimental (Xinchaun shiyan jutuan), Wang has established himself as one of the leading figures of the millennial “New Generation” of Chinese experimental theatre makers.Footnote 1 His past productions have included a wide range of work, from the first licensed Chinese-language production of The Vagina Monologues in 2009 (which Wang translated himself), to an intermedial reimagining of Chinese playwright Cao Yu's (1910–96) modern classic Thunderstorm (Leiyu, 1934) as Thunderstorm 2.0 (Leiyu 2.0) in 2012, to Constellations in 2015. Wang often uses cameras onstage and live-feed video projection, and the titling of many pieces as versions “2.0” speaks to his engagement with our contemporary culture of iteration and update. At the other end of the spectrum, however, he also experiments with paring theatre down to its bare essentials, as in a production of Lao She's (1899–1966) play Teahouse (Chaguan, 1957), as Teahouse 2.0 (Chaguan 2.0) in 2017, that took place in a high-school classroom with an audience of only eleven. And while he has certainly made a name for himself in China, Wang frequently tours his productions and collaborates with prominent theatre artists worldwide, which places his work in conversation with global trends in postcolonial dramaturgy and intermedial aesthetics.

As an unplanned shift in his spring 2020 plans, Wang's Godot was a pivot and stopgap measure in the same vein as most online theatre activity in the early weeks of the pandemic. However, it also was produced by the Guangzhou Opera House (Guangzhou da juyuan), China Performing Arts Agency (CPAA) Theatres (Zhong yan yuan xian), and Tencent Arts (Tengxun yishu)—all important players in the Chinese arts and entertainment industry—and streamed via Tencent's popular video platform. This made it one of the first examples, worldwide, of a major venue and theatre company embracing live streaming for work that directly responded to the coronavirus crisis and that adapted its production process to take place online, distanced and dispersed. Equally significantly, the production opportunity spurred Wang to adapt a set of techniques and themes with which he has been experimenting for the past decade, through different productions, into a new medium. Formally, Wang's previous, in-person productions have largely fallen squarely in the realm of the “intermedial” as it has been defined in recent theatre and performance studies scholarship: he uses a range of material media onstage, engages multiple sensory modalities, and thematically addresses interrelations between theatre and other media.Footnote 2 In particular, his use of cameras and screens in the service of self-reflexively deconstructing the classics accords with Chiel Kattenbelt's arguments that intermediality entails relations between media that result in their redefinition and that “intermediality is very much about the staging (in the sense of conscious self-presentation to another) of media.”Footnote 3 In this version of Waiting for Godot, in contrast, the screen became the stage and challenged Wang to find new ways to convey the same sense of self-presentation and self-reflexivity. Combined with the specific moment in time when Wang's Godot premiered, his first foray into fully virtual theatre enabled him to achieve an even more successful interrelation of intermedial elements than in his earlier work.

Waiting for Godot also crystallized and clarified the fact that the main thread connecting Wang's work is not media itself, but rather the use of media toward an ongoing exploration of intimacy and what this concept means in specific contexts: in contemporary world theatre, in the state of political exception that characterizes China today, in a digital age defined by its technologies, and, now, amid a global pandemic. Wang engages with multiple, intersecting genealogies of intimacy, beginning with the fundamental actor–audience relationship in theatre and the way that media onstage can both foster and fragment that intimate relationship. In this, he is in dialogue not only with theorists and practitioners of intermedial theatre, but also with the well-rehearsed late twentieth century debates over liveness in performance and the wide range of modern and contemporary theatre artists who have explored intimacy through less technology-focused forms. At the same time, his exploration of theatrical and dramatic intimacies is also connected to a broader questioning of what human connection means for modern and contemporary societies, on both local and global levels. This line of inquiry relates to the ways in which intimacy is colloquially defined as person-to-person interaction and studied in relation to kinship, friendship, and romantic or sexual relationships in the fields of psychology, sociology, anthropology, and cultural studies. In modern Western societies, the context of these intimate relationships then provides the grounds for processes of self-construction and self-narration, as argued in the seminal work of Anthony Giddens and others, and the “intimate public” that is a necessary precondition for political community, as discussed by Lauren Berlant.Footnote 4

Although this latter genealogy is rooted in Western liberalism and cannot be broadly applied to the Chinese context, the particular facets of intimacy that Wang's work explores—such as romantic relationships, interiority, and construction of the self—resonate simultaneously with the foreign and the local. Moreover, his primary focus is on the way in which media and technology affect these multiple dimensions of intimacy, both in the theatre and in real life. On a formal level, his work creates intimate relationships between performers and material technologies onstage, while also experimenting with how mediation can provide access to new levels of interiority. Thematically, however, his stance is more critical: he highlights the difficulties inherent in attempting to form intimate connections or construct self-narratives in a world suffused with technology and social media. He directly implicates these forces in the splintering of the “intimate public” as individuals may feel increasingly disconnected from a coherent political community (as in the United States) or alienated from a unified national narrative that does not correspond to the complexities of reality (as in the People's Republic of China). What his work identifies is nothing short of a crisis of intimacy in which human connection is paradoxically both potentially enhanced and forestalled by media and technology. Although far from new, this crisis of intimacy was exposed in new and more immediate ways by the COVID-19 pandemic: the survival of live theatre was threatened by fears of contagion and large gatherings, nearly all communal life moved into the virtual realm, and a genuine existential threat increased the use of technology for public (health) monitoring and control.

In responding to these issues, Godot was thus eerily prescient of the questions that the global theatre community would be forced to confront as the initial pandemic lockdown transformed into more than a year of waiting for theatres to reopen. As Wang articulated in an “Online Theater Manifesto,” published on 20 April 2020, the speed with which all in-person theatre ceased at the outset of the pandemic made shockingly clear that the art form had become “non-essential.”Footnote 5 Godot was his first step in reckoning with this realization and, as his subsequent manifesto makes clear, forced him to turn his characteristic radical, deconstructive approach inward and toward his own work. The result is a theatre of immediacy that embraces responsiveness, political community, and ethical engagement as its essential elements. Its specific components—intermedial technique, theatrical intimacy, and the concept of “immediate theatre”—are also not themselves new, but their reconsideration and reconfiguration under the pressures of pandemic temporality offer broader lessons for how all theatre might grapple with the contemporary moment.

To this end, this article examines intimacy, intermediality, and immediacy in the work of Wang Chong and Théâtre du Rêve Expérimental from both before and during the coronavirus pandemic. I first discuss how Wang Chong and Théâtre du Rêve experimented with intermediality and intimacy in several representative prepandemic productions, achieving a more sophisticated balance between the two over time. Then, I examine Wang's most recent projects in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and explore the ways in which he interweaves the live and the mediated in order to accentuate political critique and create a more intimate experience for his audiences. Finally, I conclude with a brief discussion of Wang's “Online Theater Manifesto” and his evolving vision for the future of Chinese and world theatre. Ultimately, Wang's new vision may cure neither the crisis of intimacy facing contemporary society nor its root causes, but his work makes a strong case for a theatre of immediacy as a necessary therapeutic for our troubled times.

Establishing Intermediality and Exploring Intimacy, 2006–2014

Wang Chong has been invested in exploring the meaning of theatre in a digital age and the relationship between the human and the technological since his artistic career began, when he worked with renowned director Lin Zhaohua after graduating from college. Although Wang's undergraduate education at Peking University had focused on law, he went on to pursue an M.A. in Theatre Studies at the University of Hawai‘i and enrolled in a Ph.D. program in theatre at the University of California at Irvine. He left his doctoral program in 2008 to found Théâtre du Rêve Expérimental, but continued to participate in international training and development programs including at the Watermill Center, with Robert Wilson, and the Lincoln Center Theater Directors’ Lab. Wang's early work, produced while he was still a student and shortly thereafter, combined the influences of Lin and Wilson, in particular, with his training in Euro-American theatre and his interest in technology and mediatization. For example, e-Station (Dian zhi yizhan, 2008), the first piece produced by Théâtre du Rêve Expérimental, was a piece of physical theatre inspired by Japanese director Ōta Shōgo that featured interactions in slow motion amid a stageful of technological detritus—computer and Ethernet cords, old cell phones, keyboards, monitors—and a camera feeding live footage onto a screen upstage.Footnote 6 As Mari Boyd has noted, the play both addressed the theme of “alienation in today's technologically dominated society” and revealed the “machinery of the stage” itself, by exposing bare walls and scaffolding.Footnote 7 The actors physically entangled in cords and the presence of cinematic apparatus onstage marked the performance as both materially and philosophically intermedial—mediating between humans and technology, theatre and film, connection and alienation.

Hamletism, which Wang directed at the University of Hawai‘i in 2006, also signaled another characteristic feature of his work: a critical and deconstructive approach to classics, both Chinese and foreign. In his director's note for the production, Wang expresses frustration with the repeated staging of the same classic plays, like Hamlet, and describes his own approach of extracting lines from Shakespeare's script in order to make the play's themes—namely, gender politics, war, and the essence of theatre—relevant to a contemporary world characterized by globalization and a surfeit of new technologies.Footnote 8 Along with the use of live-feed video and large screens onstage, Wang would go on to develop this cut-and-paste approach to dramaturgy through a number of productions based on well-known plays and novels, such as Thunderstorm 2.0 (Leiyu 2.0, 2012), The Chairs 2.0 (Yizi 2.0, 2012), The Flowers on the Sea 2.0 (Haishang hua 2.0, 2012), Ibsen in One Take (Yijing yisheng Yibusheng, 2012), and Ghosts 2.0 (Qungui 2.0, 2014). He also published a manifesto on “New Wave Theatre” (Xinlangchao xiju) in 2012, which uses maritime metaphor to describe the washing away of the “old theatre” as well as the ephemerality of the new that rides in to replace it.Footnote 9 As Yizhou Huang has recently discussed, the tenets of New Wave Theatre and Wang Chong's signature deconstructive, intermedial style align his work with the postdramatic theatre theorized by Hans-Thies Lehmann.Footnote 10

Wang's early work in this vein is well-represented by Thunderstorm 2.0, one of his first pieces after publication of the New Wave manifesto. After premiering at the Trojan Horse Theatre (Muma juchang) in Beijing in July 2012, the production toured to Taipei (2013), Jerusalem (2016), and New York (2018).Footnote 11 Wang's Thunderstorm 2.0 transformed the family melodrama of Cao Yu's modern classic Thunderstorm into a nonlinear examination of gender and class politics set in early 1990s Beijing.Footnote 12 Lines from the original play were fragmented and divided up among actors, and a single large central screen played images from several onstage live-feed cameras. The adaptation focused on three characters—a man and his two female lovers—and their relationships, with the cameras both providing access to their interiority and invoking contemporary concerns over the ways in which cameras and screens structure perception and sensorial experience in the theatre and beyond.

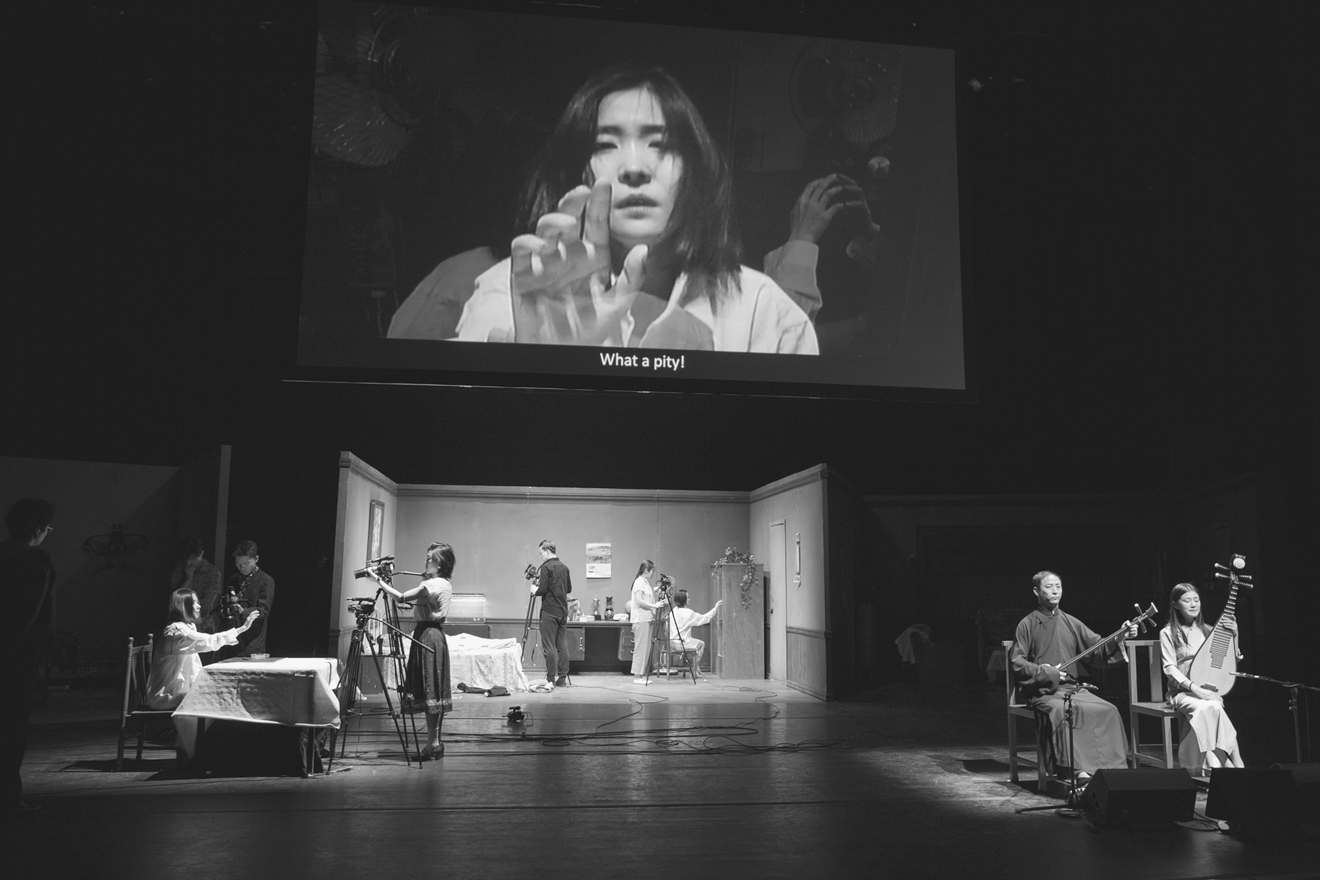

Whereas previous performance reviews and scholarship, including my own, have largely focused on Wang's deconstruction of the classics and critique of mediation, Thunderstorm 2.0 also offers an example of how, even in his early work, Wang was beginning to explore intimacy and the potential of media onstage to give access to interiority in ways beyond those available in traditional theatre (both Chinese and Western).Footnote 13 At one point midway through the play, for example, one of the female actors (Wang Xiaohuan) lies in bed with her lover, following a seduction scene. The audience watches as she gets out of bed and seats herself in front of a camera tripod downstage, and a body double takes her place in front of a mirror on set. Voice-over narration begins to relay the character's internal monologue, and the live footage cuts between perspectives of the actor's face (as though the audience were watching her through the mirror) and the profile of the body double. Mediated image and amplified sound enable the audience direct access to her self-reflection, while the disjunction between the bodies onstage and projected images conveys the disconnectedness that the character herself feels between her body and her emotions (Fig. 1). Later, she returns to bed, and the scene shifts into a dream sequence in which she fantasizes about marrying her lover. Under full lights and in full view of the audience, the actors change costume and transition into the new scene, with a dark backdrop and camera angles giving the projected sequence a haunting effect and a pingtan folk song adding a layer of whimsy.Footnote 14 A marked contrast between the reality of the female character's situation, her subjective experience of it, and the filmic fantasy of her dream simultaneously evoke feelings of distance and sympathy for the character.

Fig 1. The character played by Wang Xiaohuan seated (downstage right) and doubled onscreen in Thunderstorm 2.0. Skirball Center for the Performing Arts (New York), 6 January 2018. Photo: Edward Morris.

Wang Chong's subsequent productions, Ibsen in One Take, by Norwegian playwright Oda Fiskum, and Ghosts 2.0, based on Henrik Ibsen's Ghosts, continued both the formal and thematic explorations of Thunderstorm 2.0. Footnote 15 Ibsen in One Take, for instance, told the life story of a melancholy Chinese man and comprised plot points and dialogue fragments from various Ibsen plays. The “one take” uses cinematic vocabulary to refer both to the metaphorical single shot of the playwright's entire oeuvre and to the material use of a single, continuous live feed onstage.Footnote 16 As Yizhou Huang has argued, the piece “questions the long take's claim of the real” in film theory and “further complicates the dichotomy of virtuality versus reality” established by Wang's intermedial experimentation.Footnote 17 Also, although the camera operators remained silent and in all black throughout the play, their camera's point of view dominated the simply furnished stage as it projected close-ups on the large screen hanging above the playing space.Footnote 18 This omnipresent outside perspective can be read as an awareness of the ways in which anyone's life story is perceived and projected by forces external to oneself. As Wang Chong has noted to the press, in this piece, “Live media on stage reflects our media-filled lives, and how we constantly perform for and are watched by lenses that are everywhere.”Footnote 19 By seeing this process enacted onstage, audiences could also become more aware of their own situation and begin to question the lines between “real” and “fake” in everyday life.

This idea of performative self-awareness, in the face of ever-present lenses, connects the camerawork in Ibsen in One Take to Wang Chong's next piece, Ghosts 2.0, as well as to Kattenbelt's contention that there is a close relationship between intermediality and the broader “performative turn” of contemporary culture and society.Footnote 20 As the title signaled, this Ghosts returned to the basic conceit of Thunderstorm 2.0: deconstruction of a single classic play through the intervention of new technologies. The original text was again truncated and fragmented, but in this case retained more of its original narrative arc than in Thunderstorm 2.0. Likewise, the director returned to multiple cameras onstage, but they were largely stationary, and actors approached them to speak directly into the cameras. This form of mediated direct address gave the actors more agency over how their faces were framed, and the resulting projected large-scale close-ups worked to highlight individual characters’ expressions and reactions (Fig. 2).

Fig 2. The ensemble of Ghosts 2.0 with cameras onstage and live-feed projection. Beehive Theatre (Beijing), 6 September 2014. Photo: Screenshot from performance recording, courtesy of Wang Chong and Théâtre du Rêve Expérimental.

The constant presence of cameras in Ghosts 2.0 also called attention to the theme of public scrutiny of private acts that underlies Ibsen's original. In Ghosts, reputation and shame are motivating factors; the plot revolves around the construction of an orphanage in memory of Captain Alving, which his wife hopes will preserve his honorable image in the eyes of the community and permanently mask the scandals of his infidelity and their unhappy private life. Wang's adaptation retained this central narrative, as well as the plot points involving Mrs. Alving's son, Oswald, who has congenital syphilis due to his father's dalliances and unknowingly falls in love with his half-sister by another mother. Wang's ghosts, however, took a different form from Ibsen's: rather than the revenant manifest in hereditary disease and personality traits, these specters were the mediated doubles of the onstage live actors and seemed to comment on the way in which our lives today always already haunt us, via the doubles created through social media and involuntary surveillance.Footnote 21 Actors speaking directly into the onstage cameras referenced video messaging, YouTube, and other vlogging platforms, while the connection to surveillance was further heightened by use of a switcher, which made the projected feed look like the multipaned video of a closed-circuit television system.Footnote 22

Despite Wang's formal innovations and refreshingly irreverent attitude toward seemingly unassailable classics, however, response to his early 2010s work has been mixed. Scholarship and reviews, for instance, have grappled with Wang's treatment of gender politics: on the one hand, he is overtly critical of the patriarchal structures that persist in contemporary Chinese society, and pieces such as Thunderstorm 2.0 center female subjectivity. On the other hand, some of his most seemingly progressive moves—specifically, translating and directing The Vagina Monologues—also raise questions about his own position and privilege as a male theatre maker.Footnote 23 Viewers have also sometimes been confused or felt alienated by the copresence of live performance and media onstage. For instance, in one discussion following the original performances of Thunderstorm 2.0 in 2012, an audience member commented:

The stage looks like a film studio, with workers running around, and live-shot images appear on the screen. While watching I found it hard to focus my attention. I didn't know where to look, so I couldn't get immersed in the play. Where do you want the audience to look?Footnote 24

The chaotic scene described above has been present in all productions of Thunderstorm 2.0, but was especially true in its 2012 iteration, which was performed in a smaller space than subsequent revivals. To this audience member, Wang responded:

All of the busyness onstage is part of the content that I'm providing for the audience. This technique reflects our contemporary life—the 2.0 era is an information age. When I've seen plays in the past, like you said there's been a “feeling of immersion,” but Thunderstorm 2.0 wants to destroy that kind of “immersive” expression.Footnote 25

The immersion to which Wang refers here is not that of the recent trend in immersive theatre defined by Josephine Machon and others as experiential performance “placing the audience at the heart of the work.”Footnote 26 Instead, he refers to the notion that the theatrical experience is fundamentally one of escapism, wherein audience members suspend their critical faculties and lose themselves in the narrative world onstage. This particular form of immersion has, of course, been a familiar target of critique via the work of modernist, postmodern, and political theatre, perhaps most famously in Brecht's epic theatre. Wang's critique carries the added layer of what theatrical immersion means in the Chinese context, where concepts of realism and the fourth wall simultaneously signify the colonizing history of the Euro-American theatrical tradition and more than a century of spoken drama (huaju) development in China.

The exchange quoted above reveals an important tension in Wang's use of intermediality onstage. On the one hand, Wang's statement on immersion suggests that he aims for something similar to the effect achieved in British director Katie Mitchell's work, wherein performers create “an intimate momentum with their respective viewers by actively immersing them into the process of interpreting (where to look, how to make sense of the plot) and thus integrating them into the performance apparatus,” as Janis Jefferies and Elena Papadaki have described.Footnote 27 Mitchell's work has been one of many inspirations for Théâtre du Rêve Expérimental, and Wang Chong's direction shares much with hers, both technically and in his frequent references to classics of literature and drama.Footnote 28 As “intimate technologies,” then (to borrow another term from Jefferies and Papadaki), Wang's cameras and screens have the potential to create a closer relationship between the audience and the characters onstage, by using techniques such as extreme close-up, voice-over narration, and direct address to highlight interiority, subjectivity, and empathy. On the other hand, the above audience member's response demonstrates that for some this intervention instead evoked what Bruce Barton has termed “intermedial anxiety”—a feeling of deep unease, even betrayal, that is generated by the indeterminacies and uncertainties of intermediality in live performance. For Barton, this anxiety is most clearly visible in the concerns raised by theatre artists and scholars over the potential degradation of liveness or the live actor in mediatized theatre; for Wang's audience member, it was rooted in an expectation of uncritical immersion as the primary experience of the performance.Footnote 29 Barton has claimed that such intermedial anxiety is in fact a key component of “intermedial intimacy,” in that it can heighten “vulnerability, immersion, interactivity, and investment” and thereby “pinpoint and activate vital possibilities of/for/in theatrical intimacy.”Footnote 30 However, this does not seem to have been the case for this particular production or viewer. Within Wang's “New Wave” productions, therefore, the potential for intermediality to radically reconfigure the operations of theatrical intimacy perhaps was not fully realized.

Reconsidering Wang's work from the perspective of challenges in fully realizing intermedial intimacy, however, calls attention to an interesting parallel: many of his rewritten classics also address the failure of intimacy on a narrative level. The versions 2.0 discussed above, for example, emphasize inner monologue and stage the most intimate of experiences—nightmares, sex, pregnancy—all of which are linked to Wang's characters’ inabilities to connect with one another. In Thunderstorm 2.0, the main characters’ intimacy is forestalled by toxic masculinity, and sexual intimacy leads to nightmares, betrayal, and an abortion (performed onstage, in full view of the audience).Footnote 31 The main character of Ibsen in One Take, in reviewing his own life, ruminates primarily on the problematic relationships he had with his father and intimate partners. Likewise, in Ghosts 2.0, the betrayal of an intimate relationship is passed on to the next generation in the form of venereal disease, while the characters’ anxieties over public image nod to the potential danger of revealing the self when there is a moral disconnect between the individual and the collective. In so frequently selecting recognizable “living room dramas” as his interlocutors, Wang also draws out the strong connection between ideas of intimacy, private life, and domestic space that are inherent to these texts and the political, philosophical systems that they represent.

In other words, Wang's work uses a complex interplay between content and form to articulate a crisis of intimacy—a fundamental failure of human connection—both within theatre and in society at large. This crisis involves ideas about interiority, vulnerability, and the self that are rooted in the worldviews espoused by classic modern drama (both Western and Chinese), as well as the way in which the suffusion of media and technology in twenty-first century culture has complicated those concepts. As Barton has noted, “intermedia is the logical site of artistic practice to bring our questions about performance and intimacy in mediatized culture, as it is the matrix in which all these concerns are directly and most thoroughly interconnected.”Footnote 32 Certainly, as recent scholarship on intimacy in psychology, sociology, and cultural studies has noted, the “intimate” involves different practices and connotations across cultures, and past work that has grounded the study of intimacy in European and US experiences of modernization cannot be uniformly applied to Wang's Chinese context.Footnote 33 Likewise, mediatized culture is not monolithic—new technologies are both deeply intertwined with the uniformities of globalized, neoliberal capitalism and mobilized in a multitude of ways by individuals and societies. What Wang's intermedial practice does is further the line of inquiry that Barton describes, with the added layer of an awareness of the complex transnational histories and circulations of performance, intimacy, and mediatized culture.Footnote 34 Overall, Wang's work from the early 2010s grappled with, but did not yet fully define, which aspects of intimacy and performance might best serve as points of connection and shared critique across his diverse and transnational texts, techniques, and audiences.

Theatre, Intimacy, and Pandemic Temporalities

As the above discussion of Wang Chong's early 2010s work shows, a concern with intimacy has long been brewing across his various experiments with intermediality and what he calls “stage movies (wutai dianying).”Footnote 35 Over time, he has honed the precision with which he addresses intimacy through content and the deftness with which he uses media and technology to do so. One recent example can be found in Théâtre du Rêve Expérimental's Chinese-language production of Constellations by British playwright Nick Payne, which premiered in Beijing in 2015 and toured domestically before being presented at festivals in Groningen (Netherlands) in 2019 and New York in 2020.Footnote 36 With a cast of only two performers, Constellations explores multiple possible iterations of a romantic relationship, pairing a dramaturgical application of the many-worlds interpretation (or multiverse theory) of quantum mechanics with the love story of a cosmologist and a beekeeper. The text alternates between dialogues, which each restart a number of times in quick succession and develop in different directions, and repetitive scenes in which the cosmologist describes the progression of a terminal illness in terrified terms. As Liliane Campos has noted, the play “creates a space for the spectator's active gaze, inviting us to group [Payne's] fragments together and to find new meanings in the constellations they produce and the transformations they effect upon each other”—a dramatic structure well-suited to Wang's intervention against immersion.Footnote 37 Wang's production and its set design (by Ji Linlin and Di Tianyi) accentuated this aspect of the dramatic text by relegating its two actors to a low, circular white platform at the center of a ring of twelve cameras on tripods of different heights, arranged to resemble the numbers on a clockfaceFootnote 38 (Fig. 3). Each dialogue was videoed, live, and projected onto a large screen suspended center stage. A seemingly random alternation among cameras and projected perspectives heightened the sense of fragmentation in the text, while also bringing the audience close-up in a way that bridged those gaps with empathy. The result was both a secular, scientific meditation on how the tiniest details—a smile instead of a frown, a single word choice—matter in the search for human connection, and a window onto an individual's confrontation with the largest of existential questions—to live, in pain and diminished, or to die.

Fig 3. Du Lei (Li Jialong, center stage) and Liu Mei (Wang Xiaohuan, stage right) encircled by cameras in Constellations, November 2015. Photo: Yang Yang, courtesy of Wang Chong and Théâtre du Rêve Expérimental.

In Wang's Constellations, actors Wang Xiaohuan and Li Jialong played Liu Mei and Du Lei (localized names for Payne's Marianne and Roland) and acted as their own cinematographers, moving seamlessly between cameras and scenes. At times they embraced, upstage and with their backs to the audience, but the camera trained on their faces fed minute shifts in their facial expressions onto the large screen suspended above them, center stage. In other scenes, the dialogue became more panicked and the video overlain with a pixelated, colored filter, as the female character related the compounding symptoms of her brain tumor: aphasia, pain, terror. The cameras placed the two actors/characters “under constant surveillance, experiencing the brute forces of what we conjecture is an omniscient sense of Time controlling them, paired also with the traditional spectatorship of the live theater, yet doubled by the presence of the filming,” as one reviewer remarked.Footnote 39 At the same time, the filtered scenes signaled not surveillance, but rather the stylized self-presentation of social media or perhaps a video diary. These were moments both viscerally intimate and alienating, with the cameras simultaneously inviting the audience into closer-than-usual proximity with the actors and distancing viewers. In productions outside of China, the constant presence of surtitles at the bottom of the screen only added to the feeling of estrangement. Commenting on the experience of watching the live actors, video projections, and surtitles simultaneously in the New York production, for example, one critic remarked: “The result is an intimacy that draws one in cinematically, but simultaneously makes us feel somewhat removed from the real life drama playing out below the screen.”Footnote 40 By adding cameras and screen to the stage, Wang's intermedial production thus achieved two effects that pulled in opposite directions: mediation created a layer of distance that reminded its audience of gaps and differences in understanding, yet it also provided a point of confluence in its sustained reference to the shared experience of trying to connect with others in an age of screens and social media.

The two core elements of the play—the establishment of a romantic relationship and the sharing of highly subjective experience—also focused Constellations on the issue of intimacy, even more precisely than in Wang's earlier productions. On the one hand, the play quite literally stages a series of intimate encounters between two characters, and gestures toward the idea that intimacy involves “an aspiration for a narrative about something shared, a story about both oneself and others that will turn out a particular way,” as Lauren Berlant has argued.Footnote 41 One the other hand, in this case the intimate moments do not always lead to an intimate relationship, and the selves and narratives constructed by each character are in fact multitudes of selves and stories. Constellations is thus more a question about the nature of intimacy under conditions of great uncertainty than it is an affirmation of the intimate. Vicky Angelaki has interpreted the play in a similar light, arguing that Constellations can be read as reflecting a general inability to “attach to relationships and contexts” that stems from the precarity of neoliberalism in our current age and responds to a “crisis” that “concerns the individual's relationship to their fellow humans, and to the planet that has been so violently transgressed upon for financial profit.”Footnote 42 In this sense, then, the layered definition of intimacy advanced through the play also resonates with the more theoretically capacious concept that Berlant has articulated, especially in their claim that intimacy “poses a question of scale that links the instability of individual lives to the trajectories of the collective.”Footnote 43 In Constellations, this question of scale is stretched to the extreme, linking the instability of human lives to the trajectories of entire universes.

Moreover, although Berlant's work has generally focused on intimacy and politics in the US context, these connections between intimacy and crisis, individual and collective, seem equally appropriate when filtered through a Chinese translation of Payne's text and voiced by Chinese actors. An urban beekeeper would be just as charmingly idiosyncratic in Beijing as in London, and the laws of physics are one of the few sets of principles that remain constant across cultural contexts. Yet, if the primary crisis of intimacy addressed in Payne's play relates to and remains clearly rooted in the British experience of neoliberalism, Wang Chong's production and heavy use of media onstage shift its locus to the effects of technology on human connection. In Wang's decision to produce the play and in the changes he made to it through intermedial staging, there lies both a general agreement with the intimacy in crisis articulated in the original, and a search for more specific aspects of intimacy that are held in common and similarly endangered across contexts. This is not to say that Wang's Constellations aimed for the universal, but rather that, as an artist whose work often premieres in the PRC and then tours abroad, his directing highlights elements that can resonate for multiple audiences.

The recent remount of Wang's Constellations as part of Under the Radar in January 2020 also turned out to be uncannily prescient in its evocation of globally shared experiences of mediated intimacy and alienation.Footnote 44 The very day that Constellations opened at La Mama in New York—9 January 2020—the World Health Organization announced that the cause of a “viral pneumonia” outbreak in Wuhan, PRC, was a “novel coronavirus” and began widely publicizing information on the new disease.Footnote 45 At this point, little was known about the nature of COVID-19, and life continued as usual. As Wang developed his next production, Made in China 2.0 (codirected with Emma Valente), in Melbourne, Australia, over the next month, however, the outbreak turned into an epidemic, severe travel restrictions were implemented throughout China, and suspicions of information suppression began to fester.Footnote 46 These developments influenced Made in China 2.0, which was performed as a “work-in-progress” on 27 February 2020 and was, pointedly, a show that could not actually be “made in China.” It was nothing less than a critique of contemporary restrictions on theatre artists and free speech in China, in which Wang, as the piece's sole actor, shifted into yet another mode of theatrical intimacy by sharing his personal experiences and struggles onstage. At the same time, he also turned his intermedial techniques on himself, again using cameras and screen to amplify interiority and multiply perspectives.

Made in China 2.0 wove together a discussion of the coded visual language in Wang's productions, his run-ins with the censors, and the Wuhan COVID-19 outbreak in a way that interrogated the process and politics of personal exposure. The format was a long-form monologue, which was intercut with live-feed and prerecorded video projected onto a single large screen, suspended stage center (Fig. 4).Footnote 47 Wang spoke in English and related real-life experiences, such as using toy tanks to stand in for a reference to the 1989 Tiananmen Square Incident in one production, and how his highest-profile project—a play entitled Lu Xun (Da xiansheng) performed at the National Theatre of China (Zhongguo guojia huajuyuan) in Beijing in March–April 2016—was forced to cancel its national tour, because of being “too critical” and including a potentially negative visual reference to Mao Zedong.Footnote 48 This sharing of the personal in order to forge positive affect and mutual understanding made Made in China 2.0 fit almost a textbook definition of the “intimate interaction.”Footnote 49 Putting himself and his experiences center stage was a new experience for Wang, and in one interview about the performance, he confessed his discomfiture in taking on the role of solo performer.Footnote 50 However, he ultimately embraced the awkwardness of artistic intimacy, even taking off his shirt and performing half-clothed, as if to make it clear that he was using his international platform both to bare his soul and lay bare the hard truths of trying to work as a theatre artist in the PRC.

Fig 4. Publicity image for Made in China 2.0 (February 2020), featuring Wang Chong. Photo: Mark Pritchard.

In addition to the intimacy and vulnerability of telling his own story onstage, Wang added explicit references to the unfolding COVID-19 pandemic that brought a sense of immediacy to the production. At one point, for example, Wang showed footage clandestinely filmed inside a Wuhan hospital and a companion recording of the police attempting to enter the filmmaker's apartment after he posted the hospital video online. Onstage, Wang donned an N95 mask over his eyes and held his own hands over his mouth, first reciting sentences beginning with “I can . . . I do . . . ” and then exploding into “I cannot . . . I do not . . . I cannot repeat your lies, I do not repeat your lies!” The choice of words made clear reference to the case of Dr. Li Wenliang, the ophthalmologist who attempted to warn of a dangerous new virus in December 2019 and was forced by Chinese authorities to sign a statement admitting to making “false” statements and disrupting public order. Dr. Li died of COVID-19 on 7 February 2020.

Wang's scene was a powerful requiem that drew on Peter Brook's call for theatre to be an “immediate theatre,” that is, one that has a marked effect on its audience, wherein viewers leave the performance different from when they arrived. Brook has long been an important interlocutor for Wang, and in this production, Wang both invoked the idea of the immediate theatre as a “necessary theatre” in which “there is only a practical difference between actor and audience, not a fundamental one” and reworked the concept in a new way.Footnote 51 In Made in China 2.0, the distance between actor and audience was collapsed not through audience participation, but rather by turning the audience into political coconspirators. For example, at one point in the performance, when explicitly discussing the sensitive topic of censorship of the arts in the PRC, he made a direct plea to the audience not to report the details of Made in China 2.0 to the authorities back home. The idea that someone within the audience might betray the production made the topic of censorship and its repercussions more immediate, whereas the request for collaboration on deceiving the government drew the audience into an even more intimate—and potentially perilous—relationship with the performer.

Wang's reconfiguration of immediacy as politically engaged intimacy took on even greater importance in his online version of Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot, which premiered online a month and a half after Made in China 2.0, on 5–6 April 2020.Footnote 52 In Mandarin Chinese translation as Dengdai Geduo, the production transformed Beckett's conversation between two tramps at a crossroads into one of those late-night video chats among friends that never ends. Onscreen, the layout varied among single-frame “speaker view”; side-by-side layout of two frames, when only the two tramps (renamed Ganggang and Fufu) were present; and a matrix of three or four frames, in scenes with Pozzo (translated as Bozhuo, played by Cui Yongping) and Lucky (translated as Xingyun'er, played by Li Boyang). Ganggang (Estragon, played by Ma Zhuojun) and Fufu (Vladimir, played by Li Jialong) roamed their apartments, taking their devices with them as they lay on their beds, half-heartedly played with shoes on a treadmill, went to the bathroom. The production alternated the pathos of their dialogue with genuine humor. Xingyun'er, for example, repeatedly parodied online shopping ads, and a smart-home device stood in for the Boy who enters at the end of each act. The most timely gag in act 1 occurred when Bozhuo appeared on the scene, lines interrupted by a coughing fit. In response, both Ganggang and Fufu momentarily disappeared from their video frames, then returned wearing surgical masks and brandishing infrared thermometers (Fig. 5)—impossible to use through a webcam, of course, but offering a comedic reference to living conditions under the pandemic. In China, many cities mobilized community officials to enforce lockdown and monitor everyone entering or exiting residential complexes, making the thermometer-brandishing actors an all-too-familiar sight to the production's audience members.Footnote 53

Fig 5. Ganggang (Ma Zhuojun, lower right) and Fufu (Li Jialong, upper right) react to Bozhuo's (Cui Yongping, upper left) illness, while Xingyun'er (Li Boyang, lower left) looks on passively in Dengdai Geduo. Tencent Video, 5 April 2020. Photo: Screenshot from livestream performance, courtesy of Wang Chong and Théâtre du Rêve Expérimental.

In act 2, the pandemic references took a turn for the somber, with Bozhuo appearing in a hospital bed. In Beckett's text, Pozzo and Lucky's second-act entrance is preceded by a scene in which Vladimir and Estragon call upon God to have pity on them; God is silent, but Pozzo answers, calling for help. When he and Lucky do enter, Pozzo is blind and leads Lucky on a much shorter rope than in act 1.Footnote 54 Wang's online version, however, separated Bozhuo's and Xingyun'er's entrances. Initially, only Bozhuo appeared onscreen; Ganggang and Fufu celebrated and delivered their lines, not paying attention to their screens. This amplified the illusion that it takes a moment or two for them fully to realize that Bozhuo is not, in fact, Godot. Zoom also transformed Bozhuo's illness and blindness from a more general metaphor into a reference to the ongoing pandemic, and capitalized on the fact that the actor playing Xingyun'er was based in Wuhan. When Xingyun'er did finally enter—or rather, joined the call—he was driving over the Yangtze River Bridge and toward the iconic Yellow Crane Tower (Huanghe lou), one of the most recognizable urban landmarks in Wuhan (Fig. 6). Rather than appearing diminished and the target of abuse, as Lucky is in the text, here Xingyun'er became liberated and offered a moment of hope in anticipation of the imminent lifting of Wuhan's lockdown.Footnote 55

Fig 6. In act 2 of Dengdai Geduo, Ganggang (upper left) and Fufu (upper right) celebrate the possibility that Godot has arrived, while Bozhuo (lower left) lies in a hospital bed and a liberated Xingyun'er (lower right) drives across the Yangtze River Bridge toward the Yellow Crane Tower (top, left of center). Tencent Video, 6 April 2020. Photo: Screenshot from livestream performance, courtesy of Wang Chong and Théâtre du Rêve Expérimental.

Had Waiting for Godot been an in-person performance staged in mainland China, its direct references to the pandemic and Wuhan might well have attracted the attention of censors. In particular, the humorous depiction of temperature monitoring, Bozhuo's respiratory illness, and the night scenes of Wuhan landmarks might have been too timely and topical to pass the obligatory preperformance reviews. With the partnership of the powerful Tencent media conglomerate, however, the online production had to pass only an in-house screening and skirted the usual theatre censorship mechanism (which involves submission of a script and rehearsal recording, among other steps).Footnote 56 Ironically, by fully embracing virtual theatre, and collaborating with a company that has received criticism for its close connections to the ruling regime, Wang and his team were able to make a more pointed political critique than they could have done with one of their signature intermedial productions. Their critique resonated because of its immediacy, in terms of how nimbly it responded to the precise moment in which it was performed. At the same time, it also capitalized on immediacy, in the sense that the uncertainty of the moment and the speed with which the production was mounted may have been what enabled it to circumvent censorship.Footnote 57

Immediacy, the relative novelty of the medium, and perhaps even the boredom of isolation may all have contributed to an unprecedented 290,000 viewers accessing the production at some point during its livestream, all from the comfort of their own homes. The production began two days before official lockdown was lifted in Wuhan and while most of China (as well as any international viewers) was also still in strict self-quarantine. The actors, too, were in their own homes, in three different cities (including Wuhan), and participated in the performance via MacBook or iPad video cameras. This relocation to the private, domestic sphere was clearly a practical and necessary condition of doing livestreamed theatre during lockdown, but it also became one of the most successful and significant elements of the production.Footnote 58 First, the mapping of theatrical space onto the domestic necessitated a simple but innovative approach to production design. Potted plants stood in for Beckett's tree at the opening of the first act. A collection of various dictionaries on a well-organized bookcase in act 1 fell sideways and askew in act 2. Stopped clocks and pixelated paper clock faces placed around the actors’ apartments (see Fig. 5) offered a tongue-in-cheek visualization of the feeling that time was standing still (and a self-reference to the clockwork set in Constellations). The production also made no attempt to mask the fact that the actors were in their homes; as they moved between rooms of their apartments, family members and pets made cameo appearances. These interruptions intermittently took viewers out of the nominal world of the play, but did so in a way that drew them into another kind of intimacy with the text and its relevance to their current situations. As one reviewer noted, the presence of background noise and interruptions, which would be disruptive in a traditional theatre, in fact enhanced the “feeling of participation” (canyu gan) for audience members.Footnote 59 Another essay, by London-based Chinese theatre maker Mengting Zhuo, reflected on the liveness or “feeling of presence” (xianchang gan) created by the production and ultimately related its effectiveness to the shared context of its audience members, most of whom were in isolation under quarantine.Footnote 60 The production was not participatory per se, as audience members did not directly interact with the actors, but rather it created a sense of copresence by drawing a close analogy between the situations in which the actors, characters, and audience members found themselves.

The result was a form of analogical intimacy that depended entirely on the unique nature of the moment at which Godot premiered and the specific intermediality of a single livestreamed performance. This analogical intimacy worked as an extension of the “intermedial intimacy” defined by Bruce Barton as generated “through the performance of shared perceptual frames and dynamics,” specifically “interaction that posits ambiguity and de/reorientation as the constants of contemporary existence.”Footnote 61 In Wang's Godot, however, intimacy operated by creating a series of parallels or analogies: the shared perceptual frame was simultaneously the frame of the computer monitor and a sense of shared experience of early pandemic lockdown, which in turn paralleled the situation faced by Beckett's tramps. More significantly, the “ambiguity” and disorientation experienced through this frame was not a general condition of contemporary existence, as was the case in much of Wang's earlier intermedial critique, but rather the unique uncertainties generated by the sudden outbreak of a global pandemic.

This is not to say that everyone watching the production experienced the pandemic in the same way; if anything, more than a year of COVID-19 has made clear the ways in which the pandemic has exacerbated existing differences and disparities. Yet, there was an early pandemic moment when global experience converged during worldwide lockdowns and initial shared feelings of shock, terror, and uncertainty. At precisely this moment, refracted through Beckett's text and Wang's directorial vision, the personal resonated with the general. Audience members could clearly recognize themselves in the characters and their situation, and could clearly recognize their experience of indefinite temporal suspension as belonging to a specific moment in history that would someday (hopefully soon) become past. To again invoke Lauren Berlant's work, the production's clear and direct reference to this “broadly common historical experience”—or rather, broadly common present—thereby created an “intimate public” via digital means.Footnote 62 Put another way, Wang's Godot invited its audiences to do nothing less than historicize the present and, in doing so, to form an affectively connected and politically critical community.Footnote 63 Furthermore, although most real-time viewers of Waiting for Godot were based in the PRC, the pandemic expanded the broadly shared experience of that historical moment far beyond China's borders. As Boston-based theatre artist Igor Golyak later commented, the brilliance of Wang's directorial concept lay in “taking . . . the epicenter of all of the pain of this world and bringing something to us. . . . All of us are waiting for Godot.”Footnote 64 By highlighting this sense of universal-but-specific waiting, Wang's Waiting for Godot (version 2.0) successfully captured a structure of feeling that was nearly globally shared, if only for a brief moment.

The Online Theatre Manifesto and a Theatre of Immediacy as Antidote

As Wang's pandemic-era productions have made clear, the crisis of intimacy in the theatre is one that has become all the more urgent as COVID-19 has continued, rendering theatre spaces dangerous and preventing allegedly nonessential in-person human interaction for more than a year. Is it even possible for theatre—let alone an intimate, immediate theatre—to survive through such an attenuated crisis? The answer offered by Waiting for Godot is an unequivocal “Yes,” and indeed, throughout the pandemic, a new flourishing of online theatre worldwide has responded to the limitations of pandemic conditions with innovations both playful and serious. This simultaneous crisis and response has in turn raised further questions about the essence of theatre and how theatre will emerge postpandemic. As one reviewer of Wang's online Waiting for Godot questioned: “With only the image left, is it still theatre?”Footnote 65 And thus changed, does theatre still have the power to mirror and interrogate parallel questions of intimacy that likewise challenge the world outside its proscenium, or rather, browser window?

These questions—of whether virtual theatre is indeed theatre and its relationship to intimacy—circle back to the fundamental debates that have surrounded intermedial and fully digital theatre since the late 1990s. Moreover, as Maria Chatzichristodoulou and Rachel Zerihan (among others) have noted, there has been since the turn of the millennium a trend of politically engaged theatre artists who respond explicitly to displacement and insecurity, who demonstrate a “desire to connect with the other,” and who “play with formal, temporal and technological interfaces of intimacy.”Footnote 66 The significance of Wang Chong's work in this context is twofold. First, he is participating in and contributing to a body of work and a conversation that, in the extant criticism and scholarship, has largely been framed in relation to European and American theatre and performance (with some noted exceptions, such as Stelarc and the Japanese collective Dumb Type). In contrast, the virtuality of pandemic theatre has heightened transborder accessibility in many ways, and it is worth retaining this expanded framework as we emerge from pandemic temporality to a “new normal.” Second, Wang's response to the specific crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic offers an invitation to us all—theatre makers, audience members, scholars, and critics—to do what he has done: turn his own theatrical techniques onto himself and rethink his practice in relation to the most immediate political and ethical considerations of our moment.

The results of Wang's own self-deconstruction and reconstruction can be seen from his “Online Theater Manifesto” (Xianshang xiju xuanyan), which he published online on 20 April 2020.Footnote 67 In it, Wang draws a multilevel analogy to ancient Greek theatre, writing:

The ancient Greeks probably could not have imagined that the public forum they called theater would still exist more than two thousand years in the future. They absolutely could not have imagined that, more than two thousand years later, a plague like the one in their play Oedipus Rex would suffocate theater.

Performances have stopped; venues have closed; theater has disappeared.Footnote 68

Referencing both the “Dionysian spirit” of ancient Greek theatre and Brook's immediate theatre, the manifesto goes on to issue an explicit call for theatre to embrace the online world:

Online theater is absolutely not a stop-gap measure during this plague. As in Oedipus Rex, the plague will pass at last, and the hero, through life-and-death experiences, awakens to the truth. Human society will soon be full of virtual reality, augmented reality, artificial intelligence, and artificial organisms. So will the arts. Humans will at last redefine “human,” and also “theater.” Theater artists, having experienced “the death of theater,” should[n]’t and can't stand by awaiting our doom. Online theater is no death knell for theater, but a prelude to our future.Footnote 69

In a later discussion with Igor Golyak and Annie Levy, streamed online in August 2020, Wang elaborated on the manifesto and enumerated several key characteristics of his vision for online theatre: that the production be live and created specifically for an online audience, in a shared virtual space, in a moment of shared experience. He also made a broader argument for the essence of theatre as the “here and now”—regardless of whether that “here” is or is not a shared physical space.Footnote 70 Liveness is still essential, but for Wang, the temporality of liveness now outweighs the physicality or spatiality.

At first glance, the call to move theatre online comes as somewhat of a surprise from Wang, who for all of his intermedial experimentation onstage has been resolutely critical of prerecorded performance and eschews nonessential use of technology and social media in his personal life.Footnote 71 However, Wang does not advocate the death of live theatre, but rather sees the cessation of in-person performance during the pandemic as a clarifying moment: the fact that theatre could so easily be deemed nonessential and shut down reveals that theatre in its prepandemic form was in fact nonessential.Footnote 72 This loss of essentiality, Wang believes, has resulted from theatre's departure from its own roots as a public forum and its failure on several fronts, including as a medium of connection and in addressing pressing social and political issues. As he writes, “Most theater has nothing to do with our times.”Footnote 73 A move online, in contrast, enables a nimble response to the current moment and employs virtual space for the rebuilding of human connection through a public forum defined by expressive and artistic freedom—in other words, a theatre of immediacy that is both immediate and intermedial. In contrast to the way in which Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin define immediacy in their study of remediation, Wang's immediacy makes no attempt to erase his mediums, but rather leans into the heightened awareness that (at least temporarily) hypermediacy is a shared condition of life and of art.Footnote 74

The “Online Theater Manifesto” also takes Wang's work in an explicitly political direction. As with his formal experimentation with intermediality and thematic exploration of intimacy, this is as much a crystallization and extension of mission as a new direction. In defining online theatre as a public forum, specifically, Wang seems to respond directly to his previous experiences with censorship, as well as the tight control of information by the Chinese government during the Wuhan COVID-19 outbreak. Much of the work produced under the banner of “New Wave Theatre” already had what Yizhou Huang has termed an “implicit politics” in its approach to spectatorship, and he has become bolder in his onstage statements over time, as seen in Made in China 2.0.Footnote 75 In his manifesto, Wang's invocation of the Greek agora via his reference to theatre as a public forum draws him dangerously close to an argument for democratization. However, he leaves open the possibility that this politics might not be targeted specifically at the Chinese regime, but rather open to global contexts and a global community of theatre makers and audiences. Indeed, his emphasis on the importance of immediacy and the “here and now” has been echoed by theatre makers around the world, who similarly have been struggling with questions of survival and how to make theatre under pandemic conditions.Footnote 76 In this broader context, the idea of online theatre as public forum might resonate, for instance, with artists and audiences who find themselves disillusioned by the ways in which social media and the supposed democratization of information via the Internet has in fact resulted in mass deception and political polarization.

Taken together, Waiting for Godot and the “Online Theater Manifesto” offer a vision of what postpandemic theatre might become: an intermedial forum that works to counteract the nonessential nature of contemporary theatre, the negative effects of recent technological developments, and the limitations imposed/exposed by the global pandemic. Wang's online theatre remains intermedial, rather than fully virtual, in that it establishes “co-relations between different media that result in a redefinition of the media that are influencing each other, which in turn leads to a refreshed perception.”Footnote 77 Both theatre itself and the world online are mutually reconfigured; when theatre returns to in-person venues, it will be indelibly altered by its passage through the in-betweens of virtual space and pandemic temporality. Moreover, if Godot is to be representative of this new theatre, Wang's online theatre also seems to retain one of the key facets of his previous experiments with in-person intermedial theatre: a constant reminder of the presence of mediation. Notably, what Waiting for Godot did not do was reach through the Zoom platform to interact with audience members. During the performance, viewers could and did leave comments alongside the livestream (similar to the live commenting on a YouTube or Facebook livestream), but, unlike in some other pandemic-era online theatre productions, there was no mechanism for audience members to participate directly in the production. The Tencent streaming platform functioned as a virtual fourth wall, holding audience members at arm's length even as it enabled the performance to enter their personal spaces and mirrored many of their personal experiences of quarantine and lockdown. This drawing-in-while-distancing also parallels the tension between intimacy and alienation found across much of Wang's work. However, rather than being a drawback, this refusal to immerse the audience fully insists upon critical distance as the foundation for Wang's online theatre-qua-public forum.

Conclusion

By summer 2020, the number of COVID-19 infections in the PRC had dropped enough for some normal activities to resume, and many theatres opened at reduced capacity, while the pandemic continued to rage elsewhere. In March 2021, as vaccine rollouts began to accelerate worldwide, Wang Chong mounted an online production of British playwright Neil Bartlett's dramatization of Albert Camus's The Plague, which streamed in English alongside an all-female Cantonese-language production directed by Chan Tai-yin as part of the Hong Kong Arts Festival.Footnote 78 And by the time this article is published in September 2021, Broadway theatres will (likely) be reopening at full capacity.Footnote 79 As the possibility of a pandemic endpoint hovers—perhaps closer, perhaps endlessly—on the horizon, the analogy between our contemporary experiences and Waiting for Godot seems all the more apropos. However, the precise ways in which each of us is waiting have also become more and more diverse, as the attenuation of pandemic time has heightened and emphasized disparities in pandemic experience. Those privileged enough to continue their jobs online have remained safe while frontline workers face burnout from months of personal exposure; the claustrophobia of working from home with a family has become differentiated from the mental health challenges of being single, isolated, and alone; and vaccination has become a polarizing political issue in the United States and created specters of a new apartheid between wealthy countries with access to production, distribution, and patents and poorer countries without.Footnote 80

In this moment, theatre artists, critics, and scholars have turned to the questions of how theatre might (perhaps soon) emerge from the crisis and what lasting impact the sudden shift to online experimentation will have going forward.Footnote 81 For Wang Chong, the experience of producing live theatre under lockdown simultaneously crystallized the core elements of his theatre practice and catalyzed a move in a new direction, toward a more explicitly political mission for his work. Wang's radical reconfiguration of his own theatre practice as a result of the pandemic does not provide a simple answer or single path forward for other theatre practitioners, but it is an open invitation to self-reflection and self-deconstruction—which first anticipated and later paralleled the moment of reckoning theatre around the world has faced due to the pandemic and the political movements that have happened in its midst. It is also an invitation for European and American theatre to become more capacious in our interlocutors, just as Wang has been engaged with transnational collaboration, cross-cultural citation, and shared intermedial technique throughout his career. The online theatre that Wang now envisions, represented by the livestreamed production of Waiting for Godot, offers intermediality and its fraught intimacies as the essential components of a vibrant public forum. With all of its ambivalences, this public forum ultimately may not fully cure the crisis of intimacy that Wang's work has identified, but it does offer a powerful antidote to counteract the forces that deem art nonessential.

Tarryn Li-Min Chun is an assistant professor in the Department of Film, Television, and Theatre at the University of Notre Dame, where she holds a concurrent appointment in East Asian Languages and Cultures and is a faculty fellow of the Liu Institute for Asia and Asian Studies. Her research explores the interrelation of technological modernization, artistic innovation, and politics in modern and contemporary Sinophone theatre. Her current book projects include Revolutionary Stagecraft: Theatre, Technology, and Politics in Modern China and new research on “Spectacle and Excess in Global Chinese Performance.” She is the coeditor of Rethinking Chinese Socialist Theaters of Reform: Performance Practice and Debate in the Mao Era (University of Michigan Press, 2021) and has published articles and reviews in Asian Theatre Journal, Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, TDR, Theatre Journal, Wenxue (Literature), and Xiju yishu (Theatre Arts), as well as several edited volumes.