The ‘respect, protect, and fulfill’ framework of responsibility for human rights structures a significant amount of theory and practice, and it is time for it to change. The framework was developed by the United Nations (UN), in the context of work in the 1980s by the Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights on the right to food. This paper provides a critique and a new interpretation of the idea of a responsibility to ‘respect’ human rights that emerged from that framework. The responsibility to respect human rights is currently understood as grounded in a universal duty to do no harm.Footnote 1 This is problematic as an exclusive focus or foundation. This paper proposes to re-define the responsibility to respect human rights to include a duty not to dehumanize. This involves the need to take seriously that others have human rights; that others' equal humanity constitutes an important basis for decision-making and action; and that no one is less than human for these purposes. This change can help to re-equip the respect–protect–fulfill framework to deal better with the human rights challenges of today, as compared to sticking rigidly with a set of conceptions that was developed within and for the 1980s context. This argument will be developed in three parts. The first part argues that the current interpretation can change. The second part shows why it needs to change. The third part provides an account of what that change can look like.

The first section of the paper identifies the origin of the current definition of the responsibility to respect human rights (this will be abbreviated to ‘responsibility to respect’) within the UN system in the 1980s. There was a perceived need at that time to move beyond a false Cold War binary dichotomy between civil–political and socio-economic rights. Respect, protect, and fulfill were introduced as a spectrum, that – between the three elements – captures the full spectrum of responsibility that exists for all human rights. The framework grounds ‘respect’ in a ‘do no harm’ principle. This is not purely a matter of logical or normative analysis; it had a political purpose. It helped to convince Western liberals in a late Cold War context that socio-economic rights are just as important to pursue as civil–political rights, because obligations for the former could also be met – in some circumstances – simply by getting out of peoples' way. The specific definitions of the framework's elements (respect, protect, and fulfill) that were developed in the 1980s and consolidated in the 1990s are not best understood as set in stone in positive law or in analytical philosophy: as the best or only way to collapse a false dichotomy between ‘negative’ and ‘positive’ rights. Rather, they are better understood as subject to reinterpretation and change. This can ensure that the framework can continue to do its work of capturing the full spectrum of responsibility for all human rights, in our current context.

The second section introduces an example from contemporary human rights practice: respect for the human rights of unauthorized migrants who have crossed the US–Mexico border. This is done in order to animate the argument, to ground the paper's practical significance, and especially in order to identify and discuss two problems with basing the responsibility to respect human rights exclusively in the notion of harm. First, harm is a politically and ethically contested concept. One response to this, which others have already adopted, is to engage in the contestation: to defend one's definition of harm as going beyond a libertarian minimum. Without rejecting that strategy completely, this paper nevertheless offers a different insight. It should be possible to engage in a discussion about what counts as failure to respect human rights separately from (and irrespective of) the question of what counts as harm. Second, the notion of harm is intended by the current version of the respect–protect–fulfill framework to constitute the responsibility to respect human rights as justiciable. However, this has a double-edged effect. On the one hand, this provides a potential, albeit not always effective, route to remedy for abuses. On the other hand, however, it seems to cast failures to respect human rights in a language better suited to torts and/or crimes, rather than capturing anything that distinguishes human rights abuses from these other ways of harming others. A focus on justiciability ‘converts’ human rights problems into a fungible language of how these can (or could) be best dealt with in the realm of normal politics and law: by attributing guilt to individual agents and institutions, and then by dealing with the guilty through an institutionalized process. As sensible as this may sound in the abstract, it is precisely the uncontested outcomes of ‘normal’ politics and law that so often gives rise to human rights problems: especially in authoritarian contexts, but also, as this paper particularly highlights, in modern democracies.

The third section offers a reinterpretation of the responsibility to respect human rights, grounded in the duty not to dehumanize, as a new way forward. This can help the idea of the responsibility to respect human rights to become better fit for purpose in contemporary global politics than an exclusive ‘do on harm’ foundation. This is based on: the need for all moral agents to see human rights as an important and available basis for decision and action in today's world; an understanding that human rights practice constitutes a form of embeddedness for the sake of defining political equals; and ultimately on the interconnectedness (rather than sharp separateness) of moral, political, and legal responsibility. This reinterpretation seems to weaken the perfect-duty (non-discretionary and directed toward specific rights-holders) nature of the responsibility to respect human rights, in favor of something more imperfect and interpretable (Schneewind Reference Schneewind1990). However, the entire human rights enterprise ultimately amounts to very little without agents and institutions who endorse, believe in, and are willing to act in line with the ideas and values behind it. This is the gap that the responsibility to respect human rights can fill, as one part of a broader three-part framework.

There is a burgeoning literature in International Relations on the topic of responsibility, but within this, the respect–protect–fulfill framework has barely been discussed.Footnote 2 The few critiques of the framework that do exist come from the field of international law, and they tend to argue either that the original three elements are fine but that more should be added, for example, the state duty to ‘facilitate’ or to ‘promote’ human rights in addition to ‘respect,’ ‘protect,’ and ‘fulfill’; or that the framework has not succeeded at fulfilling a presumed problem-solving (Cox Reference Cox1981) objective of making violations of socio-economic rights justiciable (Koch Reference Koch2005; Alston and Goodman Reference Alston and Goodman2013, 181–85; Bódig Reference Bódig, Mills and Karp2015). This paper's reinterpretation of the framework is at a more fundamental level, because it starts with a new account of the scope of each of the three elements: the questions to which the current definitions of ‘respect,’ ‘protect,’ and ‘fulfill’ are supposed to provide answers. For these reasons, at the same time as providing its reinterpretation, this paper also serves as a new reference point for International Relations scholars on a set of concepts in international theory and practice – responsibilities to respect, protect, and fulfill – that has already become widely adopted in other related disciplines, as well as in the interdisciplinary field of human rights studies. Ultimately, this paper's argument is intended to de-center ‘do no harm’ rather than to remove it from the concept entirely. Harm can be and often is bound up with dehumanization. However, the argument does involve rejecting that the sole normative basis of the responsibility to respect human rights consists of the idea that one can do whatever one wants as long as it does not demonstrably harm others.

Respect, protect, and fulfill

The ‘respect, protect, and fulfill’ framework conceptual framework provides the currently dominant answer to the question ‘what is the responsibility to respect human rights?’ This section first explains what the framework is and where it comes from. Second, it compares the political context of the framework's emergence to the present, in order to highlight that it is contingent on that context and history – rather than logically or normatively necessary – for the framework to distinguish between negative and positive duties in order to attempt to dissolve a false binary between negative and positive rights. Third, it subjects the framework's core concepts to an adapted version of the neo-Aristotelian method suggested by Chris Brown's (Reference Brown and Brown1999) work on the early Martha Nussbaum (Reference Nussbaum1988), in order to illustrate how the framework could be reinterpreted in a way that avoids a negative/positive dichotomy in terms of both duties and rights.

What is the ‘respect, protect, and fulfill’ framework? There is an analytical answer as well as a historical answer, and ultimately the two should be addressed alongside one-another in order to arrive at a more complete picture. Through this combination, one can begin to interpret the framework's purpose (Karp Reference Karp2013). One key of aim the framework is its attempt to reject and to move beyond a false binary divide between so-called ‘negative’ and ‘positive’ rights. Instead, all human rights, whether civil–political or socio-economic, are associated with a full spectrum of duties. To this end, the framework defines the responsibility to ‘respect’ human rights as the responsibility of individuals and institutions not to harm the human rights of others through direct, detrimental action. It defines the responsibility to ‘protect’ human rights as the responsibility of a third party, usually the state, to prevent and to react to human rights harm committed by others. Finally, it defines the responsibility to ‘fulfill’ human rights as the responsibility to provide each person with access to the objects of his or her human rights. The right to be free from arbitrary detention, for example, requires not just restraint on the part of individuals (‘respect’). It also requires institutions that prevent, investigate, punish and deter abuses (‘protect’), which in turn may require the allocation of significant public resources (‘fulfill’). Similarly, the right to health can be violated by negligent doctors, pharmaceutical companies, or corrupt public health officials who harm individuals' health directly (‘respect’), but also requires an institutional framework that sets rules and investigates abuses (‘protect’), and that allocates resources to health provision (‘fulfill’). This is how the framework is usually understood. This paper calls this the ‘current’ or ‘orthodox’ interpretation.

The clearest moments of the framework's formal adoption in international law and policy can be found: in the Maastricht Guidelines on Violations of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which were produced following a meeting in January 1997 convened by the International Commission of Jurists, the Urban Morgan Institute of Human Rights, and the Centre for Human Rights of the Faculty of Law of Maastricht University (1998); and in the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1999a) General Comment 12 on the right to food. The language of responsibilities to ‘respect, protect, and fulfill’ then rapidly cascaded into further General Comments by the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1999b, 2000), for example, General Comments 13 and 14 on the rights to education and health – and from there, it had a significant and far-reaching subsequent effect on theory and practice.Footnote 3 In philosophy, it now structures thought about how to categorize and to analyze responsibility for human rights (Pogge Reference Pogge2011; Benhabib Reference Benhabib2014). In political science, it is used to operationalize and to measure responsibility for human rights (Green Reference Green2001; Neumayer Reference Neumayer2005; Landman and Carvalho Reference Landman and Carvalho2010; Fariss Reference Fariss2014; Landman Reference Landman, Spanakos and Panizza2016). In public international law, it now provides the standard textbook understanding of the doctrinal nature of states' human rights obligations (Bódig Reference Bódig, Mills and Karp2015; De Schutter Reference De Schutter2018). It features prominently in the research and advocacy of international non-governmental organizations (Rubenstein Reference Rubenstein2004; Amnesty International 2016). Perhaps most obviously – given the role played by the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in sparking its formal adoption – it directly structures everyday practices of human rights monitoring and state reporting within the UN system (for background, see Chapman Reference Chapman1996). It is so ever-present by now that it is easy for someone coming across it for the first time to assume that it dates all the way back to the creation of the contemporary human rights regime in the 1940s. But it has a more recent origin. All of this makes it particularly significant to understand the point of the framework, and to revisit the cogency of its current interpretation.

Those moments of the framework's formal adoption in the late 1990s can be understood as the consolidation and widespread uptake of practitioner efforts that began over a decade earlier – from the early-to-mid 1980s – on the human right to food. Shue's (Reference Shue1980) book Basic Rights was a direct intellectual influence: it contains a similar distinction between ‘duties to avoid depriving,’ ‘duties to protect from deprivation,’ ‘duties to aid the deprived,’ in the context of a discussion on the basic right to subsistence. However, the respect–protect–fulfill framework is distinct.Footnote 4 It is this work on the right to food, which one participant retrospectively described as ‘activism with an academic base’ (Eide Reference Eide2001) to which the framework's proximate origins in the world of practice can be traced. Following a UN-organized meeting in 1981 in Norway on the human right to food (Eide et al. Reference Eide, Eide, Goonatilake, Gossow and Omawale1984; Eide Reference Eide1987), and preceding a second significant conference organized by the Netherlands Institute of Human Rights in 1984 (Alston and Tomaševski Reference Alston and Tomaševski1984), the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations appointed Asbjørn Eide as Special Rapporteur in 1983 (United Nations Economic and Social Council 1985). This was in response to a widespread perception that institutions such as the Food and Agricultural Organization (created 1945), the World Food Programme (created 1961), and the World Food Conference (created 1974) had failed to get to grips with global food poverty (Eide et al. Reference Eide, Oshaug and Barth Eide1991, 437–47). These failures were attributed, most memorably by Sen (Reference Sen1981), to the institutions' focus on inter-state distribution of resources, to the exclusion of understanding the reasons for sub-optimal food distribution at the intra-state level. The right-to-food advocates aimed to use the idea of human rights as a way to re-orient these international efforts toward a tighter, less statist focus on obligations to and outcomes for individuals, so many of whom continued to live in dire food poverty.

This right-to-food work came up against three interrelated political challenges. The first challenge was how an artificially constructed binary between civil–political rights and socio-economic rights had taken normative hold over many parts of the global human rights system at both national and international levels. Shue (Reference Shue1980) understood his book as a response to a context in which civil–political rights, with security rights being their paradigm, were thought to be ‘negative’ because their advancement requires the state to get out of peoples' way; and in which socio-economic rights, with subsistence rights being their paradigm, were thought to be ‘positive’ because their advancement requires state intervention. ‘Negative’ in this context means that a right can only be violated by taking action, and ‘positive’ in this context means that a right can be violated simply by remaining passive (Nickel Reference Nickel1993; Koch Reference Koch2005, 83–84; Donnelly Reference Donnelly2008; Fredman Reference Fredman2008; Macklem Reference Macklem2015, 68–75). The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights had both just come into force in 1976, embodying this separation at an institutional level. When combined with the idea that it is more difficult to create judicial enforcement and accountability mechanisms for rights that can violated simply by remaining passive, this association of two supposedly-different kinds of rights with a negative/positive binary made progress on socio-economic rights more difficult (Roth Reference Roth2004; Koch Reference Koch2005). The second challenge was the cautious attitude of many recently decolonized states in the global South. Despite a general willingness to use the language of socio-economic rights to advance their objectives around development, international re-distribution of resources, and political non-intervention, there were also ‘fears of an absolute demand on the government’ to feed everyone, in a context of relative resource scarcity (Eide Reference Eide2001, 583). The third challenge was the resistance of the USA, at the same time as the Cold War was once again becoming a highly salient feature of international politics in the 1980s after a period of détente. For example, a review of the work that was published as a result of the above-mentioned 1984 conference in the Netherlands emphasizes as its context the existence of a Western ‘bias towards “negative” rights – i.e. those requiring government to refrain from particular intrusions upon individual autonomy – rather than “positive” rights, which require some affirmative governmental intervention for their implementation’ (Peltier Reference Peltier1987, 107–08). The same review subsequently adds for emphasis that ‘the assertion of an internationally enforceable right to food need not dictate the establishment of communist or socialist regimes’ (Peltier Reference Peltier1987, 109). This gives insight into a 1980s Western anxiety – and the need therefore to provide a political response to it – that the advancement of positive rights could be a back door through which communism or socialism would enter. The practitioners themselves explicitly identified ‘cultural resistance and ideological obstacles’ as an impediment to realizing the right to food, emphasizing particularly their belief that ‘social and economic rights meet resistance in the United States’ (Eide et al. Reference Eide, Oshaug and Barth Eide1991, 428). This normative resistance had concrete downstream effects on the work of intergovernmental organizations such as the World Food Committee, which operates on a consensus principle, meaning that – like so much of the rest of the UN system – it only works effectively if all or most states agree (Eide et al. Reference Eide, Oshaug and Barth Eide1991, 444).

By contrast, Whelan and Donnelly (Reference Whelan and Donnelly2007) label the idea of Western opposition to socio-economic rights a ‘myth’ (see also Macklem Reference Macklem2015). For example, the thesis of the USA's supposed enmity to socio-economic rights glosses over how the 1930s Western welfare-state model and the 1940s idea of ‘freedom from want’ directly influenced the subsequent development of socio-economic rights within the UN system. Conversely, the USA was in fact ambivalent about the full-throated endorsement of universal, internationally recognized civil–political rights until the 1960s: after it had begun a reckoning with its own deeply problematic record in this regard of racial segregation (Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik and Ignatieff2005). However, these myths were solidified to such a great extent that one can say they became real within the global politics of the 1980s. They signpost the resistance at that time in the West, which practitioners felt the need to overcome, to the idea that food – thought to be socio-economic and therefore ‘positive’ – is an important human right. At that time, traditionally center-right parties such as those led by Reagan and Thatcher were winning elections, with ‘get the state out of the way’ representing the mantra that brought them to power (see also Nozick Reference Nozick1974). In short, the thesis of the USA's opposition to socio-economic rights is not true of the whole Cold War. Instead, it represents an important depiction of the Cold War's final decade. This was a real and significant challenge faced by practitioners in the 1980s, serving to highlight a political situation that was newly salient at that time.

Therefore, rather than being the strategy in and of itself, the respect–protect–fulfill framework formed a core component of the tactics. This is especially true of the role played by ‘respect’ within that framework. Looking again at the analytical definitions provided at the beginning of the current section: ‘Respect’ can be viewed as a negative duty; ‘fulfill’ can be viewed as a positive duty; and ‘protect’ can be thought of as sitting in the middle because it is a derivative positive duty (the duty of third parties to do ‘something’) but one that is ultimately grounded a more fundamental negative, universal responsibility to avoid causing harm. Alternatively, respect–protect–fulfill can be viewed as a spectrum that runs from negative to positive, with ‘respect’ at the negative end and ‘fulfill’ at the positive end. In this light, to ground ‘respect’ in the idea of ‘do no harm’ within a broader three-part human rights framework can be seen as a strategic attempt (Carpenter Reference Carpenter2007) to forge a consensus that gave the then-ascendant libertarians something they felt able to endorse, even when it comes to socio-economic rights such as the right to food. Since the right to food can be violated simply by failing to respect – for example, individuals' right to the property on which they grow their food, or their right to the earnings with which they purchase it – there is something in the framework to appeal to people who are ideologically predisposed to support the state's fundamental duty not to interfere.Footnote 5 This also lent itself to a ‘right to feed oneself’ terminology (Eide Reference Eide2001, 579) that appealed to those states in the global South that were concerned about the use of a human rights framing to impose and/or to enforce limitless obligations in the context of limited resources.

It is striking that the framework aims to dissolve a negative/positive dichotomy at the level of rights, but in doing so, it reintroduces that same dichotomy at the level of duties. At first glance, this reintroduction of the negative/dichotomy as part of a putative attempt to move beyond it is a puzzle. It raises at least two questions. First, why does the framework re-introduce a similar negative/positive dichotomy at the level of duties to the one it aims to dissolve at the level of rights? Second, is it necessary to do so in order to be comprehensive about the forms of action (by responsibility-bearers) that each and every human right may require? The answer to the latter question is ‘no.’ To define ‘respect’ in a negative way so that ‘get the state out of the way’ libertarians would have something to latch onto would not have worked in the same way, for example, in the 1930s and 1940s, when the USA's objective was first to consolidate its welfare-state model and then to promote internationally as a desirable development path. Nor would it have worked in the same way in the 1950s when a focus on ‘respect,’ defined in that way, would have shone an even brighter spotlight on the USA's system of racial inequality. As this section has already suggested (in response to the former question), the need to have a discrete and clear negative-duty component was, instead, a political response to the 1980s context. This historical contingency gives at least a prima facie reason to think that change is possible. If the most relevant features of the 1980s context have changed, then one should expect the framework to be able to change too, in order better to deal with the human rights challenges of today. These features have, indeed, changed.

With the end of the Cold War in the 1990s and into the 2000s, ‘respect’ came to be seen not merely as one co-equal element of a three-part schema that aimed to bring in do-no-harm libertarians alongside government interventionists (‘protect’) and redistributionists (‘fulfill’), such that there is ‘something in it’ to render the support of the framework politically viable for groups or blocs that are presumed to have each of these priorities. Rather, the end of the Cold War ended up privileging the respect element due precisely to its close association with the liberal market-capitalist ideology that was thought to have ‘won’ (Krauthammer Reference Krauthammer1990; Fukuyama Reference Fukuyama1992). The sometimes-implied and often-invisible flip side of ‘do no harm’ is ‘… and it's fine to do anything else.’ This enabled the framework's interpretation to be changed into something subtly different, which is still with us today. ‘Respect’ is now accorded a certain level of priority, and viewed by philosophers and lawyers as uniquely fundamental to the entire human rights enterprise due to its non-derivative and/or justiciable nature as compared to ‘protect’ and ‘fulfill,’ even for those who believe in a more expansive and positive definition of harm (Linklater Reference Linklater2006; Pogge Reference Pogge2011; Mills and Karp Reference Mills and Karp2015). It has been accorded a foundational rather than equal place within the three-part framework. It therefore should come as no surprise that what started off as an activist initiative in a relatively obscure corner of the UN system in the 1980s gained such a widespread formal uptake by the end of the 1990s. The forces that are presumed to have won the Cold War were precisely the ones to whom the framework's ‘respect’ element was designed to speak. However, to prioritize one element lacks the balance between three parts intended in the framework's original version. Moving forward to the present: with the renewed rise of national populism in the West, including in the political parties that brought both Reagan and Thatcher to power, the rhetorical force of pointing to a libertarian normative floor – minimizing harm to others and getting the state out of the way – as representing a baseline political consensus, is no longer as viable a starting-point as it once was (if indeed it ever was to begin with). Specifically, today's ascendant right-wing ideology envisages a much more muscular role for the state. Simultaneously, many others have noted the declining ability of the West to present its preferences to the rest of the world as though they are an apolitical consensus position, particularly in the area of human rights (Hopgood Reference Hopgood2013).

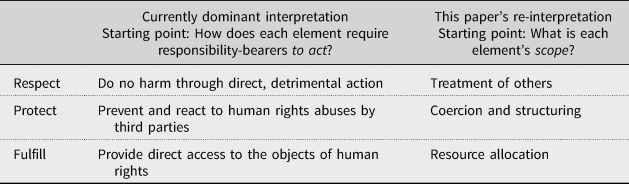

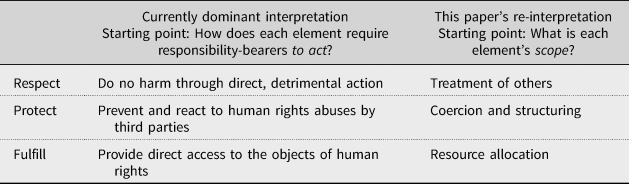

Moral philosophers and legal scholars tend to view categories such as ‘respect,’ ‘protect,’ and ‘fulfill’ as fixed and unchanging, once they have been established. This is not the best starting point. Instead, each of the three terms constitutes an area of responsibility for human rights for global actors. More so, or at least prior to, telling actors in global politics what they ought to do, the tripartite framework brings forms of action into being, by clarifying what counts as respecting, protecting, or fulfilling human rights (Searle Reference Searle1995; Frost Reference Frost1996).Footnote 6 Ideas of this kind are generally subject to a certain, though not unlimited, level of contestation and change (Karp Reference Karp2009; Wiener Reference Wiener2014). A better interpretation of each of the three terms – one that does not need to start with the tactic of drawing a negative/positive distinction at the level of duties – moves away from the answers that were provided in the 1980s and consolidated in the 1990s about what states need to do in order ‘respect,’ ‘protect,’ and ‘fulfill’ human rights, and toward an account of the questions to which those answers are aiming to respond. By adapting a method that Brown (Reference Brown and Brown1999) has called neo-Aristotelian, these three terms can be thought of as identifying specific areas or spheres of human rights action and decision-making. Start with a more general illustration to show how the method works. ‘Facing the risk of damage to oneself in order to pursue one's aims’ is a broad sphere of action and decision for human agents (Nussbaum Reference Nussbaum1988). ‘Courage’ is the name that has been given to what it means to do the right thing (whatever it is) within this sphere (Nussbaum Reference Nussbaum1988). Specific conceptions and definitions are of what it means to be courageous – how to act well or rightly within that sphere – are downstream from this, and may vary with time, place, circumstance, experience/standpoint, and context. This does not make all context-specific interpretations of what to do in order to be courageous equally good. It simply helps to understand the structure of the relationship between (1) an area of human action/decision, (2) a concept or label for what to do within that area, and (3) a specification of how to act and decide well in particular situations. When this approach to global ethics in general is applied to responsibility for human rights in particular, one already sees signs of the second step: names for three spheres of action and decision (respect, protect, and fulfill). One also sees signs of the third step: downstream prescriptions for action (do no harm; prevent and react; provide direct access), which are meant to capture what responsible agents should do within each of these spheres. However, it is striking that no one has yet explicitly specified the first step: the area/scope of action and decision-making for each of the three terms (Table 1).

Table 1. Starting-points for an interpretation of the ‘respect, protect, and fulfill’ framework

Following this approach, the scope of the responsibility to respect human rights can be defined as treatment of others needed to secure human rights. The scope of the responsibility to protect human rights can be defined as coercion of moral agents and structuring of social action needed to secure human rights. Finally, the scope of the responsibility to fulfill human rights can be defined as resource allocation needed to secure human rights. These are starting points (step 1), with attached concepts (step 2) from which thicker conceptions of what it means to respect, protect, and fulfill human rights can be further developed and debated (step 3). Re-cast in this way, three significant points about the respect–protect–fulfill framework are immediately apparent. First, it is a comprehensive account of responsibility for human rights. This means that between the three elements, everything that a responsibility-bearer might be morally and/or legally required to do in relation to others' human rights is meant to be covered. Second, each of the three elements is equally important. None of them is ‘primary’ or more ‘fundamental’ than any of the others, and none can be excluded from a sound overall account of responsibility for human rights. Third, each element is, at least a priori, neutral in terms of a distinction between negative and positive duties. In terms of ‘protect’: human rights practice needs to involve coercion in some cases (e.g. police work), but requires explicitly refraining from coercion in many others. In terms of ‘fulfill’: taking human rights seriously may involve choices about when and why not to redistribute, just as often as they involve choices about when and why to do so. In terms of ‘respect’: once the framework is re-interpreted according to each element's scope (in other words: area of human action/decision), the exclusively negative formulation of respect as ‘do no harm’ also becomes possible to call into question. It becomes a matter for further investigation, rather than something that can be taken for granted as the very meaning of the responsibility to respect. This insight leads directly to this paper's next section.

Harm and respect for human rights: the example of migration on the US–Mexico border

Consider the example of what it means for an individual or institution to have a responsibility to respect the human rights of unauthorized migrants, with reference to the case of the US–Mexico border. The number of deaths of border-crossing migrants in this area has sharply risen since the mid-1990s, with over-heating, freezing, or dehydration frequently being cited as official causes of death. These deaths are attributable to a set of policies and practices known as ‘Prevention through Deterrence,’ which began in the 1990s under the auspices of Operation Blockade/Hold the Line (El Paso, Texas, from 1993), Operation Gatekeeper (San Diego, California, from 1994) and Operation Safeguard (central Arizona, from 1995) (Ackleson Reference Ackleson2005; Doty Reference Doty2011; De Leon Reference De Leon2015). The purposes of these initiatives were to deter unauthorized migrants away from the previously most popular (usually urban, easier-to-access) crossing points, and to channel them into the most geographically inhospitable territories, where they are least likely to survive the crossing process (Doty Reference Doty2011, 603–04; De Leon Reference De Leon2015, 34). To this end, a combination of fencing, manned official patrols and high-tech surveillance were deployed in order to block access to physically easier crossing-points. For example, when traveling from Mexico to Tuscon through Arizona's dry Sonaran Desert – the Sonoran Desert is one of the areas into which migrants are channeled – it is impossible for a human to carry the weight of water needed to survive the journey (Doty Reference Doty2006). This has given rise to a variety of state and non-state activity along these newer migrant crossing routes, from border patrols, which despite being (intentionally) more sparsely spread than they were around the previously popular urban crossing points, still actively apprehend and deport any unauthorized migrants they find; to non-governmental self-styled militia groups such as the Minutemen, who aim to supplement the official patrols by catching and reporting migrants; to charities such as Humane Borders that set up water stations in the desert to increase migrants' chances of survival; to the ongoing governmental policy of deporting those found to have arrived illegally, even long after the crossing is successfully made (Doty Reference Doty2006; Doty Reference Doty2007; Cabrera Reference Cabrera2010; Patel Reference Patel2010; De Leon Reference De Leon2015).

A more specific example from within the same broad area of practice is the detention of Julian and Julio Mora in February 2009.Footnote 7 Nineteen-year-old Julio was in a car, accompanying his father Julian to the latter's workplace, Handyman Maintenance, Inc. The workplace was in the process of being raided by the Maricopa County Sherriff's Office, led by (former) Sheriff Joe Arpaio, who was pardoned in 2017 by US President Donald Trump for criminal contempt due to violating a judge's racial-profiling order. The Sherriff's Office was looking for people working in the country illegally. The Moras' car was stopped on its way, for no reason other than its apparent destination, and the two men were searched, handcuffed, and escorted the rest of the way to Handyman Maintenance. There, they both were detained for 3 hours, along with other workers. Julio was also detained despite the fact that he stated he was not an employee of the company, and despite his informing the officials that he was in fact an American citizen. While detained, they were subjected to treatment that included Julian (who is diabetic) being denied repeated requests to use the toilet facilities until he ‘told the deputies that he would have to relieve himself in front of everyone,’ at which point, rather than being taken to the toilet, he was taken to the parking lot to urinate behind a car; and Julio being escorted to a proper toilet facility (in response to his own subsequent request to relieve himself), where a deputy mocked him about his genitals as he struggled to urinate with his hands still restrained by the handcuffs that the deputy had refused to remove (Patel Reference Patel2010, 454–55). Both were released after the verification of Julio's American citizenship and Julian's status as a legal permanent resident, and they subsequently sued the Sheriff's office and won US $200,000.Footnote 8

The state often claims that it takes such actions in order to protect the broader population from the perceived harmful effects of unauthorized and uncontrolled migration (Husymans Reference Husymans2000; Bigo Reference Bigo2002; Doty Reference Doty2007). When it comes to human rights, this argument and the counter-arguments to it are fundamentally about coercion as well as the appropriate limits of coercion required by human rights. They therefore fall within the scope of the responsibility to ‘protect’ human rights within the tripartite framework, as this paper defines it. However, the examples also raise separable questions about the treatment of others required by human rights: the responsibility to respect. How does one know if state actors – as well, potentially, as any involved non-state actors (Alston Reference Alston2005; Karp Reference Karp2014) – in the above examples have violated their responsibility to respect human rights in this area of practice? The orthodox interpretation of the tripartite framework defines the responsibility to respect human rights in terms of do no harm. There have been several attempts, excellent recent examples of which have come from Linklater (Reference Linklater2006) and Brincat (Reference Brincat2013), to say that the negative duty to ‘do no harm’ requires taking demanding positive action, such as redistribution, repayment, rescue, or recognition, in order for that duty to be met (see also Singer Reference Singer1972; Pogge Reference Pogge and Pogge2007). This way forward would involve accepting a ‘do no harm’ foundation for the responsibility to respect, but contesting an exclusively negative definition of what can count as harm. It allows one to include failures to take positive action within one's definition of what is harmful: particularly when factors such as geographical or causal proximity make such action possible. However, one challenge that this approach comes up against is that many liberals, and especially libertarians – despite being portrayed as the intended audience for such an argument – simply reject this more expansive and positive definition of what counts as ‘do no harm.’ The strategy of linking a harm principle to positive obligations involves first accepting, as the major premise, that one can do whatever one wants as long as it is not harmful; and then introducing a second (minor) premise, namely, that failure to act can be harmful. This second premise is intended to ‘convert’ believers in the harm principle into accepting, as the conclusion, a role for positive obligations within their project. However, if the intended audience rejects this move, no matter how well the argument is made, then this suggests there is room to consider a deeper, parallel critique. Regardless of the argument's merits in the abstract, this paper argues that the approach is still missing something normatively important, and has a significant political blind spot, when it is converted by others into something more specific: a supposedly comprehensive account of the treatment of others required by human rights. This paper considers the possibility that the argument is not sound for this purpose – because its major premise does not need to be accepted – while remaining open to the possibility of its general validity (and to its use in other contexts).

To this end, there are two specific problems that this paper will highlight with the orthodox interpretation of the responsibility to respect. The first problem is that it underemphasizes what I shall call the ‘politics of harm.’ As Linklater (Reference Linklater2006) says, harm can be viewed as an ‘essentially contested concept’ (Gallie Reference Gallie1956; Connolly Reference Connolly1993). This means not only that people with different ethical and political views will define that concept in different ways, but moreover, that one's definition of harm is often inseparable from a political point or purpose that is best served by defining harm in one way rather than another. Libertarians will define it in terms of negative duties; Marxists will define it structurally; feminists will highlight its often-invisible nature; and so on. If harm were an exclusively descriptive and/or normative notion rather than a political notion, then it should be relatively straightforward to point to the significant investment of resources into getting into people's way – at border crossings, on their way to work, and so on – which seems entirely inconsistent with a belief in the fundamental duty of public authorities to get out of people's way in order not to trample on their rights. However, this is not the only interpretation of how to apply the harm principle to the example. Governmental officials have explicitly argued that by making it more difficult for migrants to cross the border in the previously popular urban areas, they are not responsible for forcing migrants to risk their lives by crossing elsewhere. The government simply ‘lets nature take its course,’ with a 2010 Congressional report even calling the fatalities an ‘unintended consequence’ of the policy: the ‘intention’ of which is presumably to make rationally calculating individuals decide not to cross at all (Doty Reference Doty2011, 608; De Leon Reference De Leon2015, 34). Consider this as well. On 18 June 2018, in response to widespread public outrage about a detention policy that resulted in separating children from their border-crossing parents, Kirstjen Nielsen, the Secretary of the USA's Department of Homeland Security, said at a White House press briefing: ‘Parents who entered illegally are, by definition, criminals. Illegal entry is a crime as determined by Congress. By entering our country illegally, often in dangerous circumstances, illegal immigrants have put their children at risk’ (ABC News 2018). Her implication is crystal clear: The government is not harming migrants; the migrants are harming themselves…and their children too.

Remember that the harshest crossing zones are characterized by the relative absence rather than the presence of state authorities and public services. This is exactly the authority vacuum that the various non-state actors named above seek to fill. With this context already set up, migrants take their own decision about whether to cross, with knowledge of the potential costs. Therefore, they can be portrayed – indeed, they are explicitly portrayed – as directly responsible for any harm that comes to themselves in the process. Principled objections about validity and consistency aside, as a matter of effective political rhetoric, it is hard to deny the affinity between this ‘let nature take its course’ justification; the creation of the vacuum of authority and public services in places like the Sonoran desert; the atomized, rationalistic conception of the individual; and the libertarian origins of the definition of ‘respect’ as standing back, getting out of the way, doing no harm. Moreover, as electronic surveillance and fencing/walling increasingly take the place of manned patrols along the urban, easier-to-cross and previously more popular border crossing areas – and as more and more governmental and private-sector actors become involved in the deployment and processing of these technologies – it becomes increasingly complex to track the causal chains of retrospective responsibility for harm that subsequently befalls someone, potentially many years and many hundreds of miles away from the cite of that technology's deployment. Consider also that a person who is caught and reported by one of the Minutemen, and subsequently deported, ends up in a less ‘harmed’ state than someone who is not found, and dies of dehydration in the desert. Does that mean the Minutemen have, in a curious way, respected the human rights of the migrants through outcomes of their actions, because a deported would-be migrant ends up less ‘harmed’ than a dead one? The point here is emphatically not that it is impossible to track responsibility, or that responsibility evaporates just because it is complex to grapple with, or that the justifications of state officials are just as good as the best arguments that one could marshal to refute them. The point, rather, is that casting the meaning of responsibility to respect human rights primarily in the language of harm – particularly given the genealogy of that idea within a liberal conception of the autonomous individual who can do whatever he wants as long as it does not harm others (Dripps Reference Dripps1998) – enables powerful actors who are inclined to treat migrants poorly to change the discussion into one about what counts as harm, and to justify their actions according to the notion that migrants are harming themselves. This paper's insight is that it should be possible to circumvent this, by identifying failures to respect human rights irrespective of what counts as harm.

This leads to a second, deeper problem with defining respect for human rights according to an exclusive ‘do no harm’ foundation. The idea of harm, even the idea of ‘official’ harm (Pogge Reference Pogge2002, 59–63), does not fully capture what makes the circumstances and events mentioned above distinctively issues of human rights respect as opposed to ordinary torts and/or crimes (see also Meckled-Garcia Reference Meckled-Garcia2014). The treatment to which the Moras and their co-detainees were subjected seems to be relevant to the purpose of contemporary human rights practice in a way that slips under the radar of what can be fully captured by the idea of quantifiable and justiciable harm. On the one hand, the Moras themselves were clearly harmed in a way relevant to tort law, which is why they won a lawsuit, drawing from their constitutional right to be free from unreasonable search and seizure; and even in a way relevant to criminal law, which led a judge subsequently to refer the responsible sheriff for criminal prosecution (Santos Reference Santos2016). On the other hand, however, the idea of harm also can take attention away from any qualitative difference between (a) simply being unfairly detained for 4 hours, and (b) being unfairly detained for 4 hours during which time one is mocked in the toilet: in a background context in which the presence of unauthorized migrants in a community is racialized, seen as a ‘problem’ to be resolved, and used as an excuse for treating anyone presumed to be in this category as less than fully human (Doty Reference Doty2003). It puts the focus on the proximate action rather than on the enabling context. In a similar vein: to ask ‘which portion of the $200k was awarded for being forced to urinate behind a car, or would the award still have been exactly the same $200k even if that particular episode hadn't happened?’ is entirely intelligible within a paradigm of quantifying ‘harm.’ However, even to ask this question in this way gets one further away from – not closer to – what the idea of ‘respect’ needs to be able to capture, in order to constitute a sound, focused account of what kind of ‘treatment of others’ is required by human rights in this case.

Furthermore, the idea of harm is double-edged even when it comes to its enabling of judicial action. The law has some success stories in allowing victims to quantify their harm and to win cash payments, but for every success story, there are also failures. In the better-known case of Kiobel vs. Shell, victims' families used the Alien Tort Statute to sue a transnational oil company, for its alleged connection with the torture and extrajudicial execution of peaceful environmental and human rights activists in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria in the mid-1990s.Footnote 9 However, the plaintiffs lost in a unanimous decision at the Second Circuit Court in 2010 – before the case eventually ended up at the US Supreme Court, which focused on a different set of legal issues – exactly because the judges found insufficient evidence of intent on the part of that company to cause the specific kinds of harm that befell the victims (Karp Reference Karp2014, 153). It is important that there is access to remedy after human rights abuses, and the idea of harm does play a role in enabling this process. However, something seems to be missing when the main paradigm and purpose of human rights respect has become being responsible for paying a cash value to victims (among other potential consequences), as a form of deterrence and remedy, only after intentionally/negligently doing terrible things to people that can pass a politically contestable test about what clearly counts as harm. Ex-Sheriff Arpaio's eventual presidential pardon only serves to underscore what is missing when one filters out the political and social features that constitute these events as failures of human rights respect, rather than as obvious (to all observers) harms that count as torts or crimes.

The advantage of the current definition of respect, in the orthodox version of the tripartite framework, is meant to be exactly this kind of justiciability. It helped to make the case to 1980s Western sceptics that socio-economic rights are just as important as civil–political rights. However, the debate has moved on since then, with the indivisibility of human rights now better established and entrenched (Whelan Reference Whelan2010). Now that there are actual practices to evaluate, rather than simply a policy idea pending implementation, it turns out that the conflation of ‘respect’ with ‘harm’ causes problems that were not foreseen. This point leads to the next section, which presents a way to extend the foundation of the responsibility to respect human rights beyond the idea of do no harm.

The responsibility to respect human rights: a reinterpretation

So far, this paper argued that a reinterpretation of the responsibility to respect human rights is both possible and significant. The current section shows what that reinterpretation looks like. The responsibility to respect human rights is about more than just outward action. It is also about moral agents' beliefs, their inner ethical frameworks, and how these relate to and extend to others. In contrast to partisans on either side of a longstanding debate about whether human rights should be understood either as high-priority values (Gewirth Reference Gewirth1978; Griffin Reference Griffin2008) or as specific enforceable standards for action (Hart Reference Hart1955; Tasioulas Reference Tasioulas2010), this section illustrates that the responsibility to respect human rights encapsulates the interconnectedness of the two. There is already a basis for this from within human rights practice. In his highly useful archival research into the history of the 1940s drafting process of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Hoover (Reference Hoover2013, 228–31) uncovers two familiar ideas: the Lebanese representative's focus on ‘the protection of persons from the power of the state’; and the French representative's emphasis on the individual's international-legal standing. These ideas have since become dominant in human rights discourse. However, his research also uncovers a third, complementary and almost-forgotten view. P.C. Chang, the Chinese representative to the drafting committee, emphasized the importance to human rights of ‘extending our consciousness to others,’ meaning that ‘the individual must see from the perspective of others’ (Hoover Reference Hoover2013, 229–30). Chang's idea gets right to the core of what can and should be meant by human rights ‘respect.’ It is time to redevelop it, by defining the responsibility to respect human rights as a responsibility not to dehumanize.

In answering the question, ‘what kind of treatment of others is required by human rights in today's world?’ one does not need to arrive at anything derived from ‘harm’ as a first principle or core foundation. Instead, the most obvious starting-point is equality: the need to treat each person as equal in moral terms (Waldron Reference Waldron2007; Reus-Smit Reference Reus-Smit2013). Whereas others have aimed to substantiate this equality by drawing from an account of human needs or human capabilities that we all share (Galtung and Wirak Reference Galtung and Helge Wirak1977; Nussbaum Reference Nussbaum2000), or through a focus on brute economic outcomes (Moyn Reference Moyn2018), Phillips (Reference Phillips2015) has recently argued that empirical verification in this vein as a way to establish truth about the nature of ‘the human’ is not strictly necessary, and in many ways misses the point. The equality of each person is something that can be brought into existence politically – as opposed to being discovered metaphysically – by claiming it and being committed to it. She emphasizes that the kind of egalitarianism that has developed within the practice of human rights (as distinct from the kind developed within international humanitarianism): ‘see[s] the less fortunate as active participants rather than passive recipients, as people claiming what is owed to them rather than waiting on us to help them’ (Phillips Reference Phillips2015, 7). For this reason, in developing her thesis that equality is a ‘claim and a commitment’ (Phillips Reference Phillips2015, 78), the ‘commitment’ aspect tends to get underemphasized, in favor of exploring the political agency behind the ‘claim.’ The rest of this section deepens, and in some way inverts, Phillips' analysis of these themes. While it is sensible to focus on the ‘claim’ aspect when it comes to the protection and fulfillment of human rights, the commitment is highly important when it comes to defining a responsibility to respect. A commitment to human rights is not something either for the powerful (collapsing into charity, beneficence, or indeed a ‘do no harm’ principle) or for the weak (reducing questions of responsibility entirely to questions of claim rights). Rather, it is something that can constitute the powerful and the weak simultaneously. This is because it enables a language that can be used by the weak to resist, in particular through augmenting the power and resonance of claims that ‘I am’ or ‘we are’ equally human; and it also solidifies an ethical imperative for the less-vulnerable to respond in a way that is ultimately quite different from charity.

Consider the level of equality that is typically attributed to unauthorized migrants who cross from Mexico into the United States, across legal, political, and moral dimensions.Footnote 10 A certain level of equality in the legal dimension is already present. Upon entry, an unauthorized migrant becomes subject to the legal regime of the state in which she finds herself present. This has many implications, among which includes the formal protection (from harm) afforded to everyone inside the territory by the criminal, tort, and constitutional law of that state. Crimes are crimes, and negligence is negligence, regardless of whether they are perpetrated against an unauthorized migrant. The problem in this dimension is not the lack of legal equality per se, but rather: the lack of equal practical ability to access enforcement and remedy mechanisms, for fear of being discovered and deported; combined with the fact that being an equal subject of a liberal legal regime means being subjected to its enforcement oneself. Inequalities in the political and moral dimensions are ultimately more significant. In terms of inequality in the political dimension, it is clear that migrants are excluded from the political community of the state into which they aim to migrate. This exclusion has been diagnosed by Arendt (Reference Arendt1968, 296), in a different context, as the lack of the ‘right to have rights,’ and a similar dynamic has been described by Agamben (Reference Agamben1998/1942) as a status of ‘bare life’: a situation within which their political exclusion means that others' lives are perceived as expendable in the pursuit of perceived broader social/political goals (see also Butler Reference Butler2009; Doty Reference Doty2011). By contrast, the lack of attribution of an equal human status in the moral dimension arises when one focuses too much on the ‘bare’ or the ‘barely’ human. Hegel's (Reference Hegel1977) original account of the recognition of humanity in the other, for example, famously invokes the master-slave dialectic: The master can come to see aspects of himself in the slave, and vice versa, which can be taken to represent the humanity that we all share. However, this is unsatisfying as account of the nature of human equality in the moral sense, because it implies that humanization can happen alongside the continuation of practices of slavery.Footnote 11 Setting up water stations for migrants in the Sonoran desert – although laudable from various ethical perspectives – addresses the ‘bare’ human need for water, but does not (at least not in and of itself) equalize or humanize the migrants in the more robust sense required by human rights respect.Footnote 12 This is because it too easily renders them as passive and silent recipients of aid, rather than as active agents who need to have their decisions, purposes, reasons and social connections better understood and represented.

Therefore, as a form of moral responsibility, the responsibility to respect human rights involves treating other human beings as equal in the above sense. This is not exactly the same as recognizing oneself in the other and recognizing the other in oneself. Instead, it means incorporating the very idea that others have human rights into one's own identity. This needs to occur not only in individual, isolated encounters. It needs to occur also at the level of the intersubjective values and practices that help to guide moral action, decision, and judgment. Charles Taylor (Reference Taylor and Taylor1985) says that part of what it means to be a human moral agent is to act and decide on the basis of what he calls ‘strong evaluations.’ These are essentially intersubjective (rather than purely subjective or purely objective) reasons for action. For example, someone living in Nazi-occupied France who needs to decide whether to care for his gravely ill mother, or whether to leave his village and fight for the resistance, faces a moral dilemma. This is a dilemma not because there is no right answer beyond mere subjective choice, but rather, because both family love/care and political community – or, one might say today, a political commitment to fight fascists – both provide ethically valid and intersubjective reasons for making either choice (Taylor Reference Taylor and Taylor1985, 29–35). The contemporary idea of human rights is a strong evaluation of a similar kind (Karp Reference Karp2014, 79–82). A failure of responsibility to respect human rights, at the level of individual moral agents, is constituted by a failure to see, to consider, and to incorporate into one's decision-making self, the human rights of others as an available and important basis for action. Those who dehumanize migrants are not radical utilitarians, purporting to justify their actions according to what would be best for the greatest number of people. Instead, their justifications are based on what they see as significant values, such as community stability and cohesion (Cabrera Reference Cabrera2010, 124). However, history shows that such actions can quickly lead to the destabilization and disintegration of the very communities that these agents believe they are protecting (Arendt Reference Arendt1968). It destroys the ethical self at the same rate as it dehumanizes the other. The Minutemen fail to respect human rights because they do not see the importance of human rights as a strong evaluation, which co-exists with and competes as a reason for action with other evaluations. One can only make the argument that a migrant is ‘less harmed’ as a result of being caught and deported, as compared to dying of dehydration in the desert, by de-centering that migrant's equal autonomy. Crucially, this failure would apply even to an inept militia group that intended to cause harm to migrants, but failed to do so in practice. At a less extreme end of the spectrum, a failure of responsibility to respect is also constituted by a failure to align one's outward actions with the human-rights-based ethical beliefs that one claims to hold.

As a form of political responsibility, the responsibility to treat others as equally human is complex. One needs to start off by probing the view that all bearers of human rights are not, even as a normative matter, politically equal, in the sense of being members of one's own political community. The most important recent account of political responsibility in international theory has been provided by Young (Reference Young2011, 75–93), in her interpretation of Arendt (Reference Arendt1963, Reference Arendt and Bernauer1987, Reference Arendt and Kohn1994). The standard interpretation of Arendt (Reference Arendt and Bernauer1987) on political responsibility is that it reduces to collective responsibility: one is responsible for what is done in the name of one's political community, simply because one is a member. Young extends this by attributing political responsibility both to agents who take collective/public action aimed at ‘inciting others’ to join in (Reference Young2011, 90); and also to agents who fail to act collectively/publicly when circumstances demand it, calling this ‘a political responsibility not taken up’ (Reference Young2011, 88). These are valuable and applicable insights. However, contained within this notion of political responsibility is a notion of political equality from which non-members of the relevant group are still excluded. Political outsiders can be the objects of individual and/or institutional action, but, as non-members, they are not politically responsible for what is done to them. Arendt's solution, of course, was to insist on all humans' right to be part of a state, with the emphasis on the indefinite article. But this sits uneasily with the boundary-crossing example of migration that has animated this paper's empirical content – in which some people cross from their ‘own’ state's space into what is ostensibly the political community of others.

What has changed since the time that Arendt first developed these ideas is the availability of contemporary human rights practice as a political context that we now all share. Each moral agent stands in some kind of relationship to it; for example: endorsing, accepting, seeing, acting, improving, undermining, ignoring, and so on. In contrast to those who focus on states as the sole location of the political communities that are relevant for political responsibility, this re-interpretation of the responsibility to respect human rights accounts better for the political equality of each person: including the vulnerable, the excluded, and the non-members, as well as their allies and antagonists alike. This is because they can all draw from (and be affected by) human rights discourse, within and across state boundaries. This can include seeking accountability for the dehumanization of others and its consequences. However, this paper's reinterpretation of the responsibility to respect human rights is also not impartialist. Erskine (Reference Erskine2012, 452) characterizes an impartialist moral starting-point – of the kind critiqued by Price (Reference Price2008) in his reflection on the ethical horizons of IR constructivism – as ‘one that abstracts from particular social, historical, cultural, and political contexts’ (see also Erskine Reference Erskine2008; Ralph Reference Ralph2018). Human rights, as constituting a reason for action/decision that is available today to all moral agents, is indeed deeply embedded within all of the domains mentioned by Erskine: social (liberal individualism), historical (post-1940s and/or post-1970s), cultural (at both global and local levels),Footnote 13 and political (a world in which negative sovereignty is an important institutional fact).Footnote 14 Taylor's philosophy of human agency is important because it bridges these forms of embeddedness – which otherwise risk resulting in a theory of unthinking behavior in response to socialization (March and Olsen Reference March and Olsen1998) – with the possibility of active commitment, and therefore with the possibility of both choice and responsibility for those choices. Moral agents can take the idea of human rights seriously, or not; they can act in line with these reasons, or not; they can act collectively in ways that widen and deepen this embeddedness of responsibility for human rights (beyond its original contexts), and seek to improve its quality, or not. All moral agents bear these as moral and political responsibilities, because they exist today in a world in which human rights are available as a strong evaluation. These responsibilities are ‘political’ in the sense that existence in such a world gives rise to the responsibility to respect, and ‘moral’ in the sense that agents can be held to account for their own commitments, decisions, and actions.

Conclusion

This paper provided the basis of a new way forward for the ‘respect, protect, and fulfill’ conceptual framework of responsibility for human rights. It illustrated this by reinterpreting that framework's ‘respect’ pillar in particular. This constitutes an original challenge to how these ideas have been understood by lawyers, philosophers, policy-makers, political scientists, and human rights practitioners for the last four decades. It also constitutes an opportunity for readers to take up the newly proposed meanings and to develop them within their scholarly and professional practice. Rather than responding to problems in the do-no-harm basis of ‘respect’ by throwing out the baby with the bathwater – jettisoning the entire framework and/or succumbing to the view that human rights are at their end – the article engaged in a form of immanent critique. It used concepts that are already available and re-worked them from the inside, so that they can have as much significance in the present context as they did when they were first introduced (in the 1980s) and diffused (in the 1990s). The responsibility to respect human rights relates to the requirements placed on agents by human rights practice when it comes to the area of ‘treatment of others.’ This can include but needs to go beyond ‘do no harm.’ It involves: the recognition of others' equal humanity; the incorporation of the worth of the idea and practice of human rights within agents' ethical selves; and the meaningful alignment of outward action with these inner beliefs. The responsibilities to respect, to protect, and to fulfill human rights are each important. Between them, they are comprehensive about the responsibilities that agents have in relation to others' human rights. The role of the responsibility to respect human rights within this framework is to foster both public and private cultures, within which people and institutions believe in, and take seriously, the worth of human rights as an idea and practice. This is more demanding than it seems. For example, it requires liberals to overcome their default unwillingness to make agents responsible for what they value. It also undermines the idea that the most significant human rights obligations are the ones that are possible to honor simply by doing nothing. The responsibility to respect is not all there is to human rights practice. Protect and fulfill are highly important and are also worthy of reconsideration. Equally, human rights practice would be radically incomplete without the responsibility to respect, as this paper re-defines it, as one of its core elements. Instead of an apolitical consensus position, the responsibility to respect human rights represents one side of a struggle: one which needs to be chosen and defended.

Aside from making its core argument, this paper opened up several significant avenues for future research. First, the paper suggested a research direction into the historiography of human rights politics in the 1980s, in order to extend or even to challenge the currently preferred emphasis on the importance of the 1970s. Second, the paper used examples of migration along the US–Mexico border in order to animate the argument and to highlight its contemporary significance. This opens up opportunities for more structured and comprehensive case studies, using a greater number of country contexts, on the meaning of the responsibility to respect migrants' human rights within the respect–protect–fulfill framework. Third, more work is needed on the contemporary meaning of ‘humanization’ and ‘de-humanization,’ and on ways that people can be re-humanized in situations where they are already de-humanized and/or vulnerable. Scholars can now better connect the contemporary respect–protect–fulfill framing of responsibility for human rights with both historical research on humanization/dehumanization in world politics (Weinert Reference Weinert2015) and with operationalization mechanisms for this such as empathy. Fourth, future research can fruitfully investigate the relationship between individual agents' and corporate agents' responsibility to respect human rights: both in terms of the responsibilities of individuals when they work on behalf of corporate entities, and in terms of corporate entities' responsibilities for the individuals who act on their behalf. This will create new connections between responsibility for human rights and the core International Relations topic of the institutional/corporate moral agency of states and other global actors (Erskine Reference Erskine2003; Wendt Reference Wendt2004). Fifth and finally, the responsibilities to ‘protect’ and to ‘fulfill’ human rights can now be re-interpreted according to the method and framework that this paper developed by using ‘respect’ as its central focus.

Acknowledgments

Earlier versions of this paper have been presented at the Sussex Rights and Justice Research Centre workshop series (February 2016, Brighton); the ISA Annual Convention (March 2016, Atlanta); the BISA Ethics and World Politics Working Group Seminar Series (January 2017, London); the University of Glasgow IR research paper series (January 2017, Glasgow); the University of Sussex IR Research in Progress series (February 2017, Brighton); the European Workshops in International Studies (June 2017, Cardiff); the BISA Annual Convention (June 2018, Bath); and the Academic Council for the United Nations System Annual Meeting (July 2018, Rome). Thanks to all the participants at these events for their very helpful comments. For written comments and/or extended conversations, thanks in particular to: Antonio Franceschet, Mervyn Frost, Joe Hoover, Beate Jahn, Zdenek Kavan, Christopher Long, Julio Montero, Louiza Odysseos, James Pattison, Elke Schwarz, and Antje Vetterlein; as well as to the editors and reviewers of International Theory.