INTRODUCTION

In a letter written before 1399 to the sisters of Corpus Domini in Venice, Giovanni Dominici (d. 1419) encouraged them to undertake the spiritual combat between body and soul:

One does not tame such flesh by fasting, nor mortify it by prayer, nor extinguish it by concern, but one only conquers [the flesh] through mental resistance until death, resisting vigorously with Jerome: let Jerome be a mirror of my words for you, where writing to the holy virgin Eustochium he speaks of himself, having under his banner all the sensual appetites that are incited by the infernal trumpets; the righteous soul is captain over the subordinate, leading with him every holy desire, spurred by angelic nature, armed by holy virtue.Footnote 1

Dominici, writing to a group of elite urban and penitent women, called on the nuns to reflect on a similar correspondence from a thousand years earlier between the ascetic maestro Saint Jerome of Stridon (d. 420) and the religious women of Rome and Bethlehem, of which Jerome's letter 22 to Eustochium was the most famous. A few years later Dominici would again reference the church father in a letter to the Venetian nuns. In the second letter that Dominici cited, Jerome, among other things, describes the proper relations and interactions priests are to have with women, and it was those specific passages to which Dominici referred when writing to the nuns.Footnote 2 For Dominici, Jerome served as an important model and authority, due both to his ascetic practice and to Jerome's spiritual relationship with a group of pious women and the literary medium by which he had communicated with them.

It was not only Dominici who expressed this identification with Jerome when writing his letters. In this paper, I examine the manuscripts into which compilers bound Dominican letters of spiritual direction in the fifteenth century and argue that manuscript compilers sought to model Observant Dominican sanctity after Jerome's late fourth- and early fifth-century practice of writing letters of spiritual direction to women. Critical to my discussion is Roger Chartier's notion that the meanings of texts “are dependent upon the forms through which they are received and appropriated by their readers (or hearers),”Footnote 3 and Stephen Nichols's concept of “material philology . . . which sees the manuscript not as a passive record, but as an historical document . . . whose very materiality makes it a medieval event . . . [as] each manuscript represented exactly how a text, or part of a text, or a rewritten or truncated text, would have reached a particular and quite specialized audience, often in forms quite dissimilar to how another public might receive the ‘same’ work.”Footnote 4 In recent years, numerous scholars have devoted themselves to investigating miscellaneous, or multi-text, manuscripts, which were ubiquitous throughout the Middle Ages.Footnote 5 By considering both the manuscript's textual and material components, much of this work has aimed to elucidate the organizing principles (or lack thereof) of a given codex as well as a particular book's historical development, as specific sections or texts were added to or subtracted from the manuscript over time. In doing so, scholars have sought to understand better not only the tastes of manuscript compilers or their readers, but also how particular texts were interpreted and received, and to what purposes audiences may have put a specific codex.Footnote 6 In this article, then, I analyze the choices of manuscript compilers who bound Dominican letters of spiritual direction into books, and did so in ways to construct the Dominicans’ saintly personas. Compilers chose to bind the letters with certain texts in order to shape the context in which audiences encountered them, thereby influencing how readers conceptualized the letters’ place, and that of their authors, within the Christian tradition. I argue that the Dominican letters that fifteenth-century manuscript compilers most frequently chose to preserve were those written to women, and that they often bound them with the late antique letters Jerome had written to his female disciples.Footnote 7

Scholars have demonstrated how important the production and reading of manuscript miscellanies were to the spiritual, social, and economic lives of the new religious groups that emerged across fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Europe.Footnote 8 Beginning in the later decades of the fourteenth century, the Observant reform movement within the monastic and mendicant orders was part of a larger trend that also included communities of pious laymen and women like the devotio moderna north of the Alps, or penitents loosely affiliated with the orders such as Catherine of Siena's (d. 1380) mantellate in Italy.Footnote 9 These groups held in common a desire to imitate the apostles, especially through poverty, and a deeply interiorized spirituality centered on contemplation of the Passion. In the 1380s the Dominican Master General, Raymond of Capua (d. 1399), responded to calls for the order's reform by permitting the friar Conrad of Prussia (d. 1426) to establish reformed houses in Germany. Then, in 1393, Raymond tasked Giovanni Dominici with overseeing the reform of Dominican institutions in Italy.Footnote 10 Similar reforms were taking place in the Augustinian, Benedictine, and Franciscan orders. The reformers called themselves Observants due to their stated desire to more strictly observe the rules and customs of the orders; chief among these were the religious vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. Because adopting the reform agenda often required quite significant changes to a community's way of life, only a minority of religious houses instituted Observant reforms in the fifteenth century. Yet, despite their relatively small numbers, the Observants were responsible for producing much of the extant spiritual and historical literature of the period.

Observant men in each of the religious orders also actively engaged themselves in ministering to lay and religious women. Perhaps due to their stated intention of reviving the regular life, over the course of the century many of them sought to draw the disparate communities of quasi-religious laywomen, such as beguines or mantellate, under their control and spiritual guidance. Numerous communities of nuns—such as the Dominican women of San Domenico in Pisa or those at Corpus Domini in Venice—pursued the reform themselves, strictly enclosing their establishments so as to tightly regulate those who came and went, and seeking spiritual direction from the men of their orders.Footnote 11 Yet the Observant male engagement in the lives of religious and laywomen was itself fraught with controversy. Certain of the women resisted male oversight, and the Observant men attracted criticism—or were themselves anxious—due to the perceived danger of sexual impropriety. Perhaps more pertinent, however, was the increasing association of female claims to spiritual authority with demonic possession. I suggest that the manuscripts examined in this article are a product of the Dominican Observant friars’ engagement with lay and religious women during this period. The codices binding Dominican letters to women with those Jerome had written to women served to legitimize their efforts by linking them with the church father's ancient practice. Further, the audiences for these manuscripts were primarily female, and as such, the codices served to ground female devotional practice and Observant identity within the patristic tradition.

Recent examinations of how reformed institutions cultivated an Observant culture and identity, especially within Dominican contexts, have been particularly rich. Sylvie Duval's work on the history of the Observance in fifteenth-century female Dominican contexts is noteworthy on account of its holistic approach, examining the reform from its institutional, social, economic, and cultural angles as well as the networks of individuals and communities that made its spread possible.Footnote 12 Clare Taylor Jones's study of female Dominican Observant houses in fifteenth-century Germany, meanwhile, examines how liturgical and other corporate practices instilled a specifically Dominican and Observant identity within those communities.Footnote 13 Anne Huijbers has written about how Observant Dominican chroniclers worked to create an idealized identity for the reformed institutions of the order.Footnote 14 This article seeks to contribute to the growing conversation around the development and spread of an Observant Dominican identity in the fifteenth century by demonstrating that manuscript compilers modeled Observant leaders and beati after Jerome's well-established and authoritative saintly persona to argue for the ancient precedent of the reformers’ often controversial agendas, chief among them their active ministry to women. Manuscript compilers, therefore, hoped to bolster the fifteenth-century Observant reform by binding Dominican letters of spiritual direction to women with Jerome's ancient epistolary corpus.

The Observant interest in Jerome's letters speaks to the larger context of Renaissance engagement with antiquity. As Alison Frazier has shown, fifteenth-century humanists did not commit themselves solely to the discovery and imitation of pagan literature but also the texts of early Christianity, including vitae, passiones, and patristic literature such as that by Jerome.Footnote 15 One of the most significant venues for the humanist imitation of antiquity during the Quattrocento involved the writing, collecting, and disseminating of letters.Footnote 16 Humanist epistolary production is most well known for its classicizing Latin, yet numerous fifteenth-century manuscripts also bind vernacular translations of the letters by humanists like Petrarch and Bruno with the letters and treatises of classical authors such as Cicero and Seneca. The manuscript miscellany itself is a book form often associated with the fifteenth-century humanists.Footnote 17 The Observant Dominicans’ invocation of ancient authors like Jerome by means of writing, copying, and binding letters into manuscript miscellanies points to their participation in a shared cultural appreciation for the ancient past. The codices that bind Observant Dominican letters with the letters of Jerome therefore stand at the intersection of manuscript culture, religious reform, and the Renaissance “cult of antiquity” in fifteenth-century Italy.Footnote 18

This article unfolds in three sections. In the first I provide the contextual background for my argument by illustrating both the Dominican tradition of identifying with the desert fathers, among whom they considered Jerome a member, and that the fifteenth-century Dominican Observants doubled down on this identification. In the second section I provide the manuscript evidence, demonstrating that compilers often bound Observant Dominican letters of spiritual direction to women with the letters of Jerome, and that the audiences for these manuscripts were typically female. The final section of the paper contextualizes this practice within the controversies and activities of the fifteenth-century Observance and argues that through the process of manuscript compilation, the Observants strategically linked their charismatic contemporaries to Jerome's ancient and venerable legacy.

DOMINICANS, THE DESERT, AND WOMEN: THE APPEAL OF THE HIERONYMITE MODEL

Examining the earliest Dominican vitae, Alain Boureau found that the order's hagiographers consistently modeled the friars after the desert fathers.Footnote 19 As numerous scholars have noted, Dominic never possessed the same charismatic attraction as the founders of other religious orders, like Francis of Assisi; and therefore, rather than using Dominic as the primary model for the friars to imitate, they often wrote collective hagiographies presenting the lives of many Dominican brothers and saints for imitation.Footnote 20 While Boureau demonstrates that the early vitae of Jordan of Saxony, Constantino da Orvieto, and Humbert de Romans had drawn parallels between Dominic and the desert fathers like Saint Anthony, around 1260 two authors, Gérard de Frachet and Jacobus de Voragine, more emphatically grounded Dominican identity on that of the desert fathers. Boureau notes that Jacobus included fifteen stories of the desert fathers in his Legenda aurea (Golden legend) and closely centered his entries for Jerome and Mary Magdalene around their lives in the desert.Footnote 21 Gérard's history of the order is even more explicit in referring to the tradition of the fathers. For example, he titled the work Vitas fratrum (Lives of the brothers), taking “the bizarre morphology Vitas” directly from the ancient Vitas patrum (Lives of the fathers).Footnote 22 The Dominicans then, as an urban phenomenon, presented the city as a new desert full of vice and temptation against which they had to struggle, harkening back to the fathers’ struggles in the desert.Footnote 23 Indeed, more so than in the vitae of other contemporary religious orders, the thirteenth-century Dominicans presented themselves as battling demons, much as the fathers had done a millennium earlier.Footnote 24

Enshrined in some of their most popular literature, Dominican identification with the desert fathers did not disappear after the thirteenth century. Fourteenth-century Dominicans like Domenico Cavalca (d. 1342) and his circle in Pisa, for example, were responsible for the immensely popular translation of the Vitas patrum into the Italian vernacular.Footnote 25 Laura Ackerman Smoller has shown how Observant Dominicans of the mid-fifteenth century, in their hagiographies of Vincent Ferrer, represented the saint battling demons, tying Ferrer and the Observant movement to that older Dominican tradition of identifying with the desert fathers who fought demons in the desert.Footnote 26 Dominican identification with the desert fathers, I suggest, is one important context for interpreting their appropriation of Jerome as a model in the fifteenth century.

In 1985, Eugene Rice showed that it was not until the turn of the fourteenth century that the veneration of Jerome as an intercessor and model of penitential life became truly widespread.Footnote 27 One of the first images of the church father that gained popularity in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries was of Jerome as a desert penitent who later became a monk outside Bethlehem.Footnote 28 By 1400, artists were depicting Jerome either as a scholar in his study or as a penitent in the desert.Footnote 29 There is some evidence suggesting that from an early date the Dominicans took a special interest in Jerome's burgeoning cult. Rice, for instance, has suggested that it was an anonymous Dominican who authored the three pseudonymous letters of the 1290s that claim to be by Eusebius of Cremona, Augustine of Hippo, and Cyril of Jerusalem and describe Jerome's life, death, and miracles.Footnote 30 Furthermore, at least one of the first three churches dedicated to Saint Jerome in Italy was a Dominican institution.Footnote 31 In the mid-fifteenth century the Dominican and archbishop of Florence, Antoninus Pierozzi (d. 1459), included a short vita of Jerome in his Chronicon.Footnote 32

Simultaneous to the growing popularity of Jerome's cult during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries in Italy, was another much broader phenomenon involving the composition and translation of a vast array of religious texts into the vernacular. Growing demand from laymen and women as well as women in religious life spurred this translation process; yet it was often Dominican friars, like Domenico Cavalca in Pisa and later Tommaso Caffarini (d. ca. 1434) in Venice,Footnote 33 who took the lead as translators.Footnote 34 Katherine Gill has shown how the female audiences for these texts were instrumental not only in dictating what texts were translated into Italian, but also in shaping the composition of new vernacular literature.Footnote 35 She links Jerome's growing popularity to this process of increased female involvement, arguing that the translations of his works and the appearance of new apocryphal texts “[point] us immediately to the practice of spiritual direction, which, like preaching, was closely bound up with the production of religious literature in the vernacular. . . . Jerome the penitent, the desert pilgrim, the translator and correspondent was just the kind of authority for a new vernacular age, with its emphasis on preaching, translating, and spiritual direction.” Gill adds that “these letters functioned as small charters for women whose diverse endeavors, talents, interests, and religious experiences did not match the limited ad status sermon format or formal ecclesiastical legislation. They also authorized, even glamorized, male involvement with and sponsorship of women's religious interests.”Footnote 36

Jerome's ministry to a group of aristocratic female ascetics, and that he conducted much of it through letters, was an important aspect of his biography in the Middle Ages. Although commentators had largely ignored Jerome's relationships with religious women in the centuries immediately after his death, in the ninth century his writings to women began to be of interest to men who were trying to make sense of their own spiritual relationships with women.Footnote 37 In a widely circulated sermon for a pair of nuns, for example, the abbot of Corbie, Paschasius Radbertus, referred to himself as Jerome and the two women as Paula and Eustochium.Footnote 38 The late eleventh and twelfth centuries witnessed an even greater interest among some men and women in Jerome's writings for women. As Fiona Griffiths has recently argued, for twelfth-century men who cultivated spiritual relationships with women, Jerome's model allowed them to “defend their involvement with women, linking themselves to a tradition of innocent, and even saintly, relations between religious men and women.”Footnote 39

In the thirteenth century, Jacobus de Voragine further perpetuated interest in and knowledge of Jerome's letters to women when, toward the beginning of his entry for Jerome in the Legenda aurea, Jacobus cited the saint's letter 22 to Eustochium, in which Jerome describes a vision of being chastised at a celestial tribunal for preferring the writings of Cicero over scripture.Footnote 40 And shortly after, Jacobus recounts a legendary story explaining Jerome's exile from Rome to the desert (heremus).Footnote 41 In order to provide a description of the austerities Jerome endured there, Jacobus again cites his letter to Eustochium.Footnote 42 And Jerome's letters to women, translated into the vernacular, as well as letters falsely attributed to him, were immensely popular in the fifteenth century. Between 1497 and 1510, vernacular translations of his letters to his female disciples as well as the pseudonymous early fourteenth-century Regula monacharum (The rule of nuns) were printed seven times.Footnote 43 For the period prior to the printing press, I have counted in Florence's Biblioteca Riccardiana alone nine manuscripts that bind together only (or almost only) his letters in Italian translation.Footnote 44 This interest in Jerome's letters to women extended across both sides of the Alps during the fifteenth century, as Observant institutions in German-speaking lands, such as the Benedictine houses in Admont and Melk, also compiled manuscripts containing texts Jerome had written to women in Latin or vernacular translation.Footnote 45

The Observant Dominican friars were among those at the forefront of the drive to provide spiritual direction for women in both lay and religious life. Although there is a long Dominican tradition of ministering to religious and quasi-religious women since the thirteenth century,Footnote 46 the early history of the order consisted largely of the friars’ resistance to papal efforts to impose on them the responsibility over nuns and female penitents.Footnote 47 This changed in the early fifteenth century, however, when the Observants sought to institutionalize and regularize such relationships with non-cloistered penitent women by creating the Order of Penance of Saint Dominic.Footnote 48 Their ministry to women, moreover, often took the form of providing them with vernacular devotional literature. An example of this work is found in a short anonymous letter bound in an early sixteenth-century manuscript from an Observant Dominican convent.Footnote 49 The anonymous author was most likely an Observant Dominican writing to his confreres at Florence's Santa Maria Novella. He composed the letter, a brief account of the life and virtues of Giovanni Dominici, in the second half of the fifteenth century.Footnote 50 Of interest is that the author refers to one of Dominici's works, a text he says “parla della Sancta Carita” (“discusses Holy Charity”) and was therefore probably his famous Libro d'amore di carita (Book of the love of charity).Footnote 51 The anonymous friar then describes his own activities providing devotional materials for women by noting that he had copied the book for “our very own dearest and revered sister in religion, Suora Cherubina at Santa Maria della Pace.”Footnote 52 Dominici's own role in assisting the production of devotional texts for the Observant Dominican nuns at Corpus Domini in Venice and San Domenico in Pisa, as well as the laywoman Bartolomea degli Alberti, is well attested.Footnote 53 Meanwhile, recent scholarship has examined female participation in producing devotional texts by studying the practices of reading and bookmaking in fifteenth-century Dominican convents.Footnote 54 The first printing press in Florence was at the Dominican convent of San Iacopo di Ripoli, and four manuscripts containing the letters of Antoninus, or Dominici, or both came from the female Observant Dominican convent of Santa Lucia between 1470 and 1517.Footnote 55

Dominican letter-writers of this period often cited Jerome as an authority for ministering to women. I began with a passage Dominici had written to the nuns of Corpus Domini, in which he advises them to find inspiration in a letter the saint had sent to Eustochium. Years later Dominici's student, Antoninus of Florence, cited yet another letter by Jerome when consoling the aristocratic laywoman Dada degli Adimari after her husband's death. Referring to Jerome's letter 108, which he had written to Eustochium comforting her after her mother Paula's death, Antoninus told Dada, “One holy young woman hearing, as Saint Jerome says, of her husband having died, lifted her eyes to heaven without shedding tears, saying: ‘Lord, I thank you for having freed me to be able to serve you entirely!’”Footnote 56 At the end of the century, another Observant Dominican, Girolamo Savonarola (d. 1498), would also cite Jerome when writing a letter of spiritual direction to the aristocratic laywoman Maddalena Pico.Footnote 57 And long before even Dominici had written to the nuns of Corpus Domini, Catherine of Siena wrote to a widow in Lucca urging that she must “keep in mind what the glorious Jerome said about this . . . forbidding widows to indulge themselves in pleasure or to make up their faces or wear fine and fancy clothes. . . . Their converse was rather to be in their own rooms, and they were to be like the turtledove, who mourns forever after her mate is dead, living in solitude and wanting no other companion.”Footnote 58 Like Dominici, when providing spiritual direction to women these authors turned to Jerome as an authority on proper female comportment.

Yet, as I argue in this paper, Jerome became not just an authority for fifteenth-century Dominicans to cite when providing spiritual direction to women, but also a model for Observant Dominican sanctity. As a biblical scholar and desert ascetic, Jerome was already well suited to serve as a model to the scholarly and penitential Dominican friars. His role as spiritual director to pious women living in the urban context of late antique Rome, however, meant that he also exemplified for Observant Dominicans how to minister to the growing cohort of penitent and laywomen requesting their direction in the cities of Renaissance Italy. Indeed, reading copies of Jerome's late antique letters to women may have helped to authorize fifteenth-century women themselves to seek spiritual direction from men.Footnote 59 Distinct from Dominican efforts to identify themselves with the tradition of the desert fathers in hagiographic writing, which others have illustrated, I suggest that Observant Dominicans also sought to justify their work of ministering to religious and laywomen by modeling it after Jerome's practice of writing letters to his spiritual daughters. In doing so, Observants also were able to use Jerome's letters and those by recent Dominican authors to provide a framework for contemporary female devotional praxis. Thus, preserving, copying, and binding letters of spiritual direction to women with Jerome's letters to women had now become a manner by which proponents of a cult could mold it into an especially Observant version of sanctity, and cultivate an Observant identity that traced its lineage to Jerome's ancient precedent.

MODELING SANCTITY IN MANUSCRIPT MISCELLANIES

When binding different texts together into a single manuscript, medieval and early modern people did not choose them randomly. In a letter praising a manuscript Boccaccio had given him that contained texts by Cicero and Varro, Petrarch noted: “You showed, moreover, keen discrimination in gathering within the covers of one book two authors who, in their lifetime, were brought into such intimate relationship by their love of country, their period, their natural inclinations, and their thirst for knowledge.”Footnote 60 Thus, by analyzing which texts compilers commonly brought together, scholars can begin to unravel both their tastes and the ideological inclinations of various textual communities, whether they be humanists like Petrarch and Boccaccio or Observant Dominicans.Footnote 61 Yet before examining the manuscripts of Dominican letters of spiritual direction, I will turn to those codices that bind primarily or solely the letters of Jerome so as to demonstrate the similar readership contexts that link those collections to the ones that also included the letters of fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Dominicans.

Collections of Jerome's letters comprised a popular genre in this period; nine such manuscripts are extant in Florence's Biblioteca Riccardiana alone. Of these manuscripts, all but one are of the fifteenth century, and are alike in that they bring together in the vernacular one or more of Jerome's actual letters usually with the late thirteenth-century letters about Jerome and falsely attributed to Eusebius of Cremona, Augustine of Hippo, and Cyril of Jerusalem.Footnote 62 In each case the letters by and about Jerome embrace all or the vast bulk of the codex, although sometimes other texts (such as the Pauline epistles) are included. The scribe of one of these codices, Biblioteca Riccardiana, Florence (BRF), MS 1679, applied an apt name to the genre: he called it a “Book of Saint Jerome.”Footnote 63

Another codex, BRF, MS 1361, is representative of this genre. The Florentine Giovanni di Zanobi Amadory Chalzaiuolo compiled it in 1444 using 290 x 205 mm paper and a clear humanist script.Footnote 64 Most of the text is in black ink; however, the headings are in red, and Giovanni drew the initial capital to each section in blue and red, often adding decorative patterns along the margins. The book begins with the three apocryphal epistles referenced above and concludes with Jerome's actual or falsely ascribed letters to the widow Sigismonda,Footnote 65 and the female penitents Demetriades (letter 130) and Eustochium (letter 22). The book is typical in that it includes the apocryphal texts as well as letters that Jerome wrote to women, especially letter 22 to Eustochium, which in this codex, like many others, begins with its own rubric in red ink and is divided into chapters. The manuscript is also typical in that it is made of paper, yet written in a fine humanist hand with colored capitals and headings but lacking illuminations. The manuscript is not carelessly transcribed, as are so many of the fifteenth-century zibaldoni (miscellanies) commonly found in Italian libraries.Footnote 66 The neatness of its design suggests that Giovanni intended it to be used by a public that went beyond himself. He even included a note at the end of his colophon: “Whoever borrows this, please return it.”Footnote 67 Many of the folios have dirt smudges along their edges, suggesting that the manuscript was used with some frequency.

Giovanni's choice to emphasize letters of spiritual direction Jerome had written to women suggests, as Gill has stressed, a female audience and probably a monastic one. Although in most cases when the Riccardiana's “Book[s] of Saint Jerome” have a colophon they only mention the scribe, who like Giovanni is always a man,Footnote 68 on the first folio of the fifteenth-century codex BRF, MS 1634 a sixteenth-century hand proclaims that the book was “di Suor Pelegrina,” thereby proving its female monastic readership.Footnote 69 A note Giovanni made in red ink at the end of Jerome's letter to Demetriades provides further clarity. He writes: “The venerable Master Zanobi of the Order of Preaching Brothers vulgarized this letter for the use of the unlearned; that is, those people who cannot read Latin [non sanno gramaticha].”Footnote 70 The very next letter in Giovanni's collection, Jerome's letter 22 to Eustochium, opens similarly: “Desiring to put into the vernacular, for the use of so many religious women and other virgins and chaste people who cannot read Latin [non sanno gramaticha], the beautiful letter Saint Jerome sent to Eustochium which induces her to closely guard her holy virginity and fully renounce the world and its pomp.”Footnote 71 In both cases the notes say that the letters have been translated for the benefit of the “indocti” (“unlearned”) or those who “non sanno gramaticha,” referring to individuals who could not read Latin and were therefore labeled illiterati throughout the Middle Ages.Footnote 72 And like Giovanni's manuscript, other codices that include the Italian translation of Jerome's letter to Eustochium also explicitly state in the letter's prologue that the translation is intended to render the text useful to “religious women and other virgins and chaste people.”Footnote 73 The individuals to whom Giovanni lent the book were therefore most likely women. Or perhaps, when reading his statement “Whoever borrows this, please return it,” one can posit that he was taking himself out of the equation and making his request that the book be returned on behalf of its future owner, for whom he had made it.

Giovanni also specified that it was the previously mentioned Dominican friar, Master Zanobi, who translated the letter to Demetriades into Italian. And at least one other manuscript states that the translation of Jerome's letter to Eustochium was that of the famed fourteenth-century Dominican translator, Domenico Cavalca.Footnote 74 These notes then point to the involvement of certain friars from the Order of Preachers in propagating Jerome's cult at the end of the medieval period. BRF, MS 1313 provides an example in which a letter by a Dominican author, Catherine of Siena, is bound with the Hieronymite texts in question. This is a mid-fifteenth-century paper codex with 294 x 214 mm dimensions. Much of it, like Giovanni's collection of Jerome's letters, is written in a humanist italic hand with red and blue initials. The first texts in the book are sermons by Saint Augustine. Augustine's sermons are followed by Jerome's letter to Eustochium, which, as in Giovanni's collection, begins with a statement that it has been translated into Italian for religious women and other chaste people.Footnote 75 Similar to the other “Book[s] of Saint Jerome,” the letter to Eustochium is followed by the letters about Jerome by Pseudo-Eusebius and Pseudo-Augustine.Footnote 76 After the Pseudo-Augustine letter, a new hand picks up, but still in a clear humanist script, and adds two letters of spiritual direction attributed to the fifteenth-century Florentine noblewoman Brigitta Baldinotti.Footnote 77 Following the letters of Baldinotti, the second scribe includes a letter that Catherine of Siena wrote to Suora Bartolomea, a sister of Saint Stefano in Pisa.Footnote 78 Finally, a third hand in scrittura mercantesca—a documentary cursive of the thirteenth through fifteenth centuries, chiefly associated with the merchants and notaries of Central and Northern Italy—includes additional sermons by Augustine and some homilies by Origen.

Luongo has written persuasively that the manuscript contexts into which Catherine's letters were copied and bound throughout the fifteenth century significantly elevated her status as an author.Footnote 79 This process began with Raymond of Capua's Legenda maior (The longer legend), in which he compared her authorship to luminaries such as Paul and Augustine. Yet it continued when her early disciples, the Dominican Tommaso Caffarini and the Carthusian Stefano Maconi (d. 1424), each collected her letters to be copied into desk books in littera textualis (a formal Gothic bookhand), often with expensive illuminations, and organized the letters according to the hierarchical status of their recipients.Footnote 80 Later, in the mid-fifteenth century, manuscripts like BRF, MS 1313 would bring Catherine's letters together with those of classical Latin authors such as (in some cases) Cicero, but also “Jerome, Augustine, Origen, and Eusebius. In practice, Catherine was being read as one of these male Christian classics.”Footnote 81 Luongo is convincing on each point; however, I would argue further that manuscript compilers associated Catherine and other Observant Dominican beati most often with Jerome because his letters to women provided an authoritative model for their own ministry to women. It is interesting to note that Catherine's letter to Suora Bartolomea was not originally included in BRF, MS 1313's collection. The first scribe had produced a book entirely of patristic texts, starting with the sermons of Augustine, but devoting most of its space to the Hieronymite letters. It was the later scribe who chose to include the letters of Brigitta Baldinotti and Catherine of Siena. These are the first and only non-patristic additions to the codex. Furthermore, like Jerome's letter to Eustochium, the two epistles by Brigitta Baldinotti and the one by Catherine are letters of spiritual direction addressed to women. I posit, then, that the second scribe, coming across this book containing the Hieronymite letters, sought to link Brigitta and Catherine to the authoritative figure of Jerome, thus framing them as spiritual guides to women.

Other manuscripts also link Catherine's spiritual direction to women with Jerome's earlier practice. One is BNCF, II VIII, MS 5, which was compiled in 1474 for the Benedictine nuns of S. Niccolò Maggiore in Cafaggio. The convent was located along Florence's Via degli Alfani, only a brief walk from major religious institutions like the Camaldolese Santa Maria degli Angeli and the Dominican San Marco, which were famous centers of humanist learning and Observant reform. The manuscript is somewhat smaller than the others (220 x 150 mm), but is written on parchment in a humanist script with red headings, large blue initials, and red designs running up the margins. The codex almost entirely compiles letters that Catherine wrote to women—the only exception is the first text, Jerome's letter to Eustochium. Beginning with this text and ending with Catherine's letters to women, the manuscript is designed as if it were a diptych,Footnote 82 presenting Jerome and Catherine as the two saints to be venerated.

This codex bears further similarities, however, to BRF, MS 1313. Catherine's first letter included in the manuscript, immediately following Jerome's letter to Eustochium, is also that which is preserved in BRF, MS 1313, her letter to Suora Bartolomea. Like Jerome's letter to Eustochium, a major theme of Catherine's letter to Suora Bartolomea is perseverance in religious life. Catherine argues that temptations and a mind steeped in “darkness” and “perverse thoughts” are gifts sent by God, for God wills that his spouses desiring perfection follow the “way of the cross.”Footnote 83 Indeed, one ought to rejoice in such temptations for they provide opportunities to overcome them through spiritual combat and thereby victoriously mold one's own will in closer alignment to that of God.Footnote 84 Jerome, likewise, describes in his letter to Eustochium how while he was in the desert he would often be tempted by thoughts of women or the comforts of Rome. Eustochium, he advises, would have to remain vigilant against similar temptations in her community of ascetics.Footnote 85

Yet the similarities between the two letters go beyond what are fairly common themes of perseverance and spiritual combat in medieval religious literature. In both texts the authors claim to have direct experiences of God. In his letter to Eustochium, Jerome famously describes a dream vision in which he is brought before a “judge” surrounded by a court of angels.Footnote 86 The judge asks what he believes, to which Jerome replies that he is a Christian. The judge denies this and declares that Jerome is in fact a “Ciceronian” on account of his love for pagan literature. The celestial judge then has him flogged, a punishment that Jerome can still feel on his back and shoulders after waking up.Footnote 87 Catherine, on the other hand, in her letter to Suora Bartolomea describes an experience she had in which Christ came to her and reassured her that having temptations does not mean that one has fallen into mortal sin, so long as one strives to overcome them. Indeed, he finds pleasing the “battles” (“battaglie”) one wages against those temptations in order to mold her will to God's.Footnote 88 Both stories not only recount each author's direct experiences with the divine but, in the tradition of medieval exempla, Jerome and Catherine marshal their accounts to reinforce and provide evidence for their own arguments. Jerome wrote of his embarrassing chastisement to make the point that Eustochium should not critique others for their shortcomings, but pay attention to her own. Catherine, meanwhile, uses her story to reassure Bartolomea that, despite her temptations, she will remain in God's good standing should she continue to persevere in her religious vocation.

This is not to say that Catherine composed her letter with Jerome's correspondence to Eustochium as a model. However, the compiler of BNCF, II VIII, MS 5 likely placed the letters beside each other to invoke the teachings of the two saints together. For the manuscript's compiler, Catherine was a new Jerome to whom the Benedictine nuns could look as a spiritual guide, just as Eustochium and her pious community of women had turned to Jerome a millennium earlier. That the second scribe of BRF, MS 1313 added Catherine's letter to a collection of patristic texts, the majority of which were Hieronymite, further shows that some fifteenth-century bookmakers and readers sought to link Catherine's letters with Jerome's letters of spiritual direction. And a pair of letters Stefano Maconi sent to Neri Pagliaresi in the 1390s confirms that some of Catherine's direct disciples had a keen interest in Jerome and his writings to women. In the first letter Maconi states that he would have liked Pagliaresi to produce a text of “that rule of Blessed Jerome in the vernacular.”Footnote 89 This certainly refers to the pseudonymous Regula monacharum, an early fourteenth-century text claiming to be written by Jerome to Eustochium and her companions.Footnote 90 Maconi may be referring to the same text again when he later refers to sending Pagliaresi “quella scrittura di santo Ieronimo” (“that text by Saint Jerome”).Footnote 91

A third manuscript continues this pattern, bringing Catherine's letters together with those of Jerome, especially letter 22 to Eustochium.Footnote 92 This book, however, unlike the other manuscripts discussed thus far, is entirely copied in a single mercantesca hand, lending it a slightly less elevated appearance as the other more clearly humanist codices. Yet at three hundred paper folios and 280 x 210 mm dimensions it is a large book, and the mercantesca script is made clearly and in two columns, with red ink used for the headings. The book opens with a life of Saint Jerome, followed by his letter to Eustochium, a series of sermons by Augustine, a pair of short devotional texts,Footnote 93 an Italian translation of the Legenda aurea's entry for the apostle Paul, a brief prayer purported to be by Jerome, a sermon on Paul's letter to Galatians, and, finally, fifty-seven of Catherine's letters, which comprise the final one hundred folios of the manuscript. Again, Catherine's letters of spiritual direction are placed alongside Jerome's, and this time also a letter of the apostle Paul, to whom Raymond of Capua had explicitly compared Catherine in his Legenda maior.Footnote 94 As Luongo has noted, in the fifteenth century people repeatedly bound Catherine's letters with patristic texts in codices whose formal layout and appearance lent the included texts a certain degree of authority. But the texts most frequently bound with Catherine's letters were other epistolary documents, especially those of Jerome but not excluding the Pauline epistles, linking Catherine to the ancient traditions of the fathers and apostles.

This is not a pattern reserved only for the letters of Catherine. Another manuscript from a female monastic context binds the letters to women by two other fifteenth-century Dominican beati with a letter of Jerome. In 1517 at Santa Lucia, a convent of Observant Dominican nuns in Florence, one of the sisters compiled a book in a striking humanist cursive. It brings together Jerome's letter to a Roman laywoman named Laeta, two of Antoninus of Florence's letters to Dada degli Adimari, the Regula del governo di cura familiare (Rule for the administration of family care) of Antoninus's mentor Giovanni Dominici, and six letters Dominici had written to women.Footnote 95 Jerome's letter to Laeta instructs her how to raise her daughter Paula as a pious Christian. Jerome advises Laeta how she ought to educate Paula, what kinds of games Paula should play, and how Laeta must dress her. Dominici's Regula does much the same for Bartolomea degli Alberti. Though the three letters of Antoninus included in the collection do not advise on how to raise a Christian child, they do provide answers to particular theological and devotional questions Dada had posed.Footnote 96 At least this one nun of Santa Lucia, who refers to herself in another codex as “Sister N.,”Footnote 97 bound Jerome's letter to Laeta with those of the Dominican and Florentine beati, not only because they served as useful reading, but also because in this way she could link Dominici and Antoninus to an ancient Christian tradition of writing letters to women. She could therefore supply didactic reading materials for women as well as build upon the fama of two Dominican, Observant, and Florentine men, de-historicizing their legacies and placing their teachings within an eternal Christian truth.

By bringing the letters of Jerome together with those of contemporary Dominican writers, the compilers of these miscellaneous letter collections were building on the charismatic reputation of Jerome, the teacher of ascetic practice. A pair of manuscripts binding the letters of Catherine and Antoninus with the Dominican Jacopo Passavanti's mid-fourteenth-century treatise Lo specchio della vera penitenzia (The mirror of true penance) helps to support this point further. Turning first to BRF, MS 1303, which bound Catherine's letters with Passavanti's text shortly after her canonization in 1461,Footnote 98 one finds another paper desk book (285 x 200 mm) written in two columns with a humanist script.Footnote 99 Passavanti's Lo specchio is the first text in the collection. He composed it in 1354 after having preached a version of it during Lent of that same year in Florence.Footnote 100 Modeled after his Lenten sermons, the text opens with a thema of sorts in the fashion of the sermo modernus, which the mendicant friars had made popular since the thirteenth century.Footnote 101 But rather than beginning with a biblical verse, as was typical in late medieval sermons, Passavanti opens by citing that model of true penance, Jerome. Penance, Jerome says, is like a ship at sea. Its crews must always be diligent in steering it through tempests and waves to ensure its safe arrival at port.Footnote 102 Following this, Passavanti explains what he is setting out to do and why, but returns to Jerome at the conclusion of the prologue. He declares that he looks to Saint Dominic, “the sovereign preacher of penance,” for guidance on this topic; yet he also turns to “Saint Jerome, whose life and doctrine are the example and mirror [specchio] of true penance [vera penitenzia].”Footnote 103 Immediately after Passavanti's Lo specchio, the scribe added seventeen of Catherine's letters.Footnote 104 After some lauds and a text called La regholetta della confessione ad laude di Iesu Cristo (The little rule of confession in praise of Jesus Christ),Footnote 105 the codex concludes with another fifteen of Catherine's letters, all in the same hand.

The second manuscript, similar in design yet with an even more elegant humanist script and more elaborate initial capitals, brings Passavanti's Lo specchio together with the letters by a different Observant Dominican: Antoninus. The fifteen letters of Antoninus that BRF, MS 1335 binds with Passavanti's Lo specchio are all letters of spiritual direction he wrote to Dada degli Adimari.Footnote 106 Many of them, furthermore, deal directly with the topic of penance, while the others advise on living as a pious Christian. These two codices, from the second half of the fifteenth century, bring the letters of Catherine and Antoninus together with Passavanti's Lo specchio because, just as Passavanti viewed Jerome as a special authority on his chosen topic, so too were these two Dominican holy people and letter-writers.

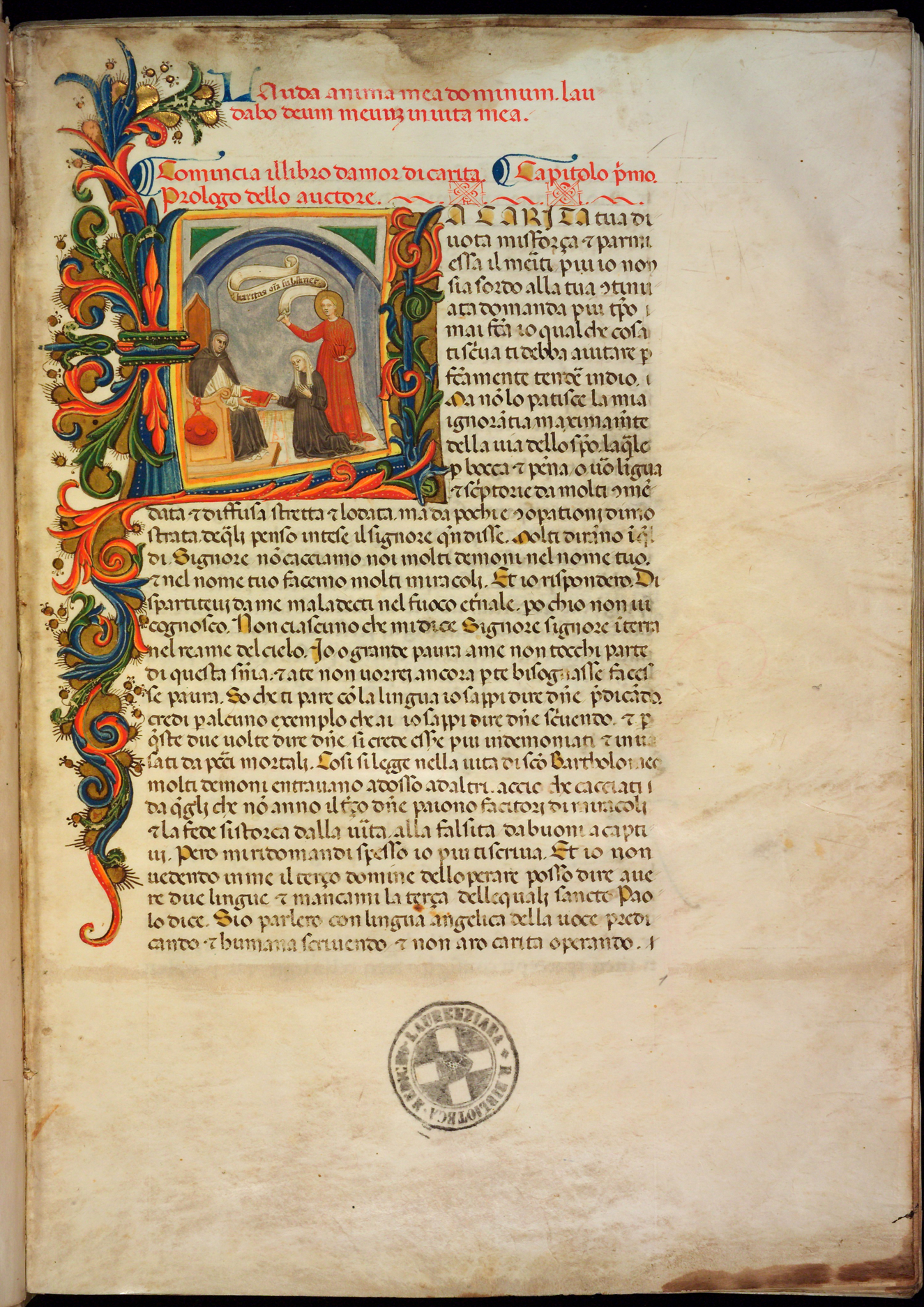

Even in cases in which manuscripts compiling the letters of Observant Dominican beati did not reference Jerome explicitly, their layout could at times induce one to think of the church father and his relationship with his disciples. Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence, Acquisti e Doni, MS 8 is a parchment desk book (285 x 200 mm) completed in 1452, written in a few Italian Gothic hands, and entirely comprised of documents Giovanni Dominici had addressed to women.Footnote 107 The first text is Dominici's Libro d'amore di carita, a treatise he had written for Bartolomea degli Alberti; this is followed by his Trattato delle dieci questioni (Treatise on the ten questions), which he had also addressed to the Florentine laywoman. These two treatises are then followed by five letters he had written to Bartolomea, a letter of his to a “spiritual daughter,”Footnote 108 eleven of the letters he had addressed to the nuns of Corpus Domini in Venice, and, finally, a sixth letter he addressed to Bartolomea. Notably, on the first folio there is an illumination depicting Dominici sitting on a throne and dressed in his Dominican habit, presenting a red book to a kneeling Benedictine nun (fig. 1). Behind the nun stands the haloed personification of Charity, wearing red and holding up a banner that reads “karitas omnia substinet.” Dominici's cardinal's hat hangs from his throne, signifying the station he achieved in April 1408. Aside from the dynamic of the male master providing texts to his female disciple, the iconographic reference to Dominici's status as cardinal further ties him to the fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Hieronymite tradition. The first references to Jerome as a cardinal appear soon after the position's invention in the eleventh century.Footnote 109 By the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the cardinal's hat and the lion that the Legenda aurea describes Jerome as befriending in the desert were the two most common motifs painters used to represent him.

Figure 1. Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence, Acquisti e Doni, MS 8, fol. 1r. With permission of the Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali e per il turismo. Further reproduction by any other means is prohibited.

Another fifteenth-century parchment manuscript that brings together only texts Dominici wrote to women, British Library, Additional MS 18169, makes an even more striking comparison to the Hieronymite iconography.Footnote 110 On the first folio, God the Father is depicted within the letter A, from which position he blows golden rays down onto Dominici, painted below within the letter D. Dominici writes at his desk wearing his Dominican habit and cardinal's hat, as the dove of the Holy Spirit sits on his shoulder. The illumination clearly argues that Dominici's words, inscribed in the book, are divinely inspired. However, in addition to wearing his cardinal's hat, Dominici is seated at his desk and writing. In the fifteenth century there were generally two scenes in which painters chose to depict Jerome: either as a penitent in the desert or as a scholar at work in his study.Footnote 111 The Observant Dominican convent of San Domenico in Pisa kept an image of Jerome from around 1430 depicting him on its left panel as a penitent in the desert kneeling before a crucifix and on the right as a scholar writing in his study with a miniature Dominican nun kneeling and praying beside him.Footnote 112 The Hieronymite iconography was familiar to female Observant Dominicans, and especially within the context of manuscripts compiling letters of spiritual direction that a man wrote to women, it is possible that the illuminations of Dominici within these two codices would have reminded their readers of the patristic saint, and encouraged them to think of Dominici as a present-day Jerome.

COMPILERS AND THEIR AUDIENCES: MANUSCRIPT COMPILATION IN THE SERVICE OF OBSERVANT REFORM

Sylvie Duval has underlined the critical role correspondences, and especially letters of spiritual direction, played in the Observant reform's diffusion through the female branch of the Dominican order.Footnote 113 Gill, Serventi, Polizzotto, and others, meanwhile, have suggested that the preponderance of letters addressed to women may be because women were leaders in requesting such guidance.Footnote 114 Taking the woman's role in requesting these typically male-authored letters as a methodological starting point, Judith Bryce has examined the letters Antoninus wrote to understand the concerns of their recipient, Dada.Footnote 115 Yet Duval has also noted, when mentioning that only fourteen of Chiara Gambacorta's (d. 1420) letters survive, that they are “without doubt a small part of the letters written by the founder of San Domenico.”Footnote 116 And indeed, the letters Gambacorta wrote to Francesco Datini and his wife Margherita survive only as recipient copies among Datini's trove of correspondences.Footnote 117 The letters Dominici and Antoninus wrote to women, however, survive in multiple manuscript copies like those examined above, thereby demonstrating that fifteenth-century compilers and readers had a particular interest in preserving them.

Both men, major figures in the spread of the Dominican Observance during the first half of the fifteenth century, certainly wrote many more than Antoninus's twenty and Dominici's fifty-three surviving letters of spiritual direction to women.Footnote 118 Although a small number of their letters to men do survive, it is those to women that are extant in multiple copies because compilers chose to copy them into manuscript codices. Compilers selected these letters over others, I suggest, largely because they were letters of spiritual direction that a man had written to one or more women. In this way, the manuscript compilers could fashion contemporary Dominican figures after the ancient and authoritative model of Jerome, as well as provide didactic and devotional reading for female audiences, now increasingly under the spiritual care of the Observant friars. Significant also is that the letters continued to circulate in manuscripts within female religious contexts well into the sixteenth century. After the printing press's arrival in Italy in the 1460s, authors and bookmakers made choices about whether to circulate a text in manuscript or print depending on the size and nature of the audiences they hoped to reach.Footnote 119 Codices binding Dominican letters to women, especially those also including letters by Jerome, were intended for female religious audiences that at least had links to the Dominican Observants. Surviving primarily in Tuscany, where communities of penitent women tied to the Dominicans had long had a presence,Footnote 120 such manuscript miscellanies could provide didactic religious materials for women as well as provide them with models of Dominican identity and spiritual authority.

Circulating letters of spiritual direction to women was not an activity confined in the fifteenth century to the correspondences of Dominici and Antoninus; however, it was a break from previous practice.Footnote 121 Bernard of Clairvaux wrote only a tiny fraction of his extant letters to women, and fewer than half of those were letters of spiritual direction.Footnote 122 While there are numerous extant thirteenth-century Franciscan letter collections, most are administrative or intended for the training of male novices.Footnote 123 Yet as demonstrated earlier, in the fifteenth century several manuscripts linked the legacy of Jerome not only with Dominici and Antoninus but also with Catherine of Siena. In her examination of the letters, primarily to women, of Catherine's contemporary and fellow Sienese, the Observant Augustinian Girolamo da Siena (d. 1420), Silvia Serventi has shown that in a number of cases fifteenth-century manuscript compilers also bound his letters with Jerome's.Footnote 124 In the early fifteenth century, an anonymous Tuscan, who may have been a Dominican, collected eighteen of his own letters of spiritual direction, most of which were written to women.Footnote 125 And Giovanni Colombini (d. 1367), who founded an order dedicated to Jerome, wrote dozens of letters of spiritual direction to women. In the final years of the fourteenth century, the nuns of Sant'Abbondio e Abundanzio bound them into a manuscript.Footnote 126

Fifteenth-century collections of letters of spiritual direction, then, were typically by Dominicans or those, like Girolamo da Siena, who had extensive connections to networks of Observant Dominicans. Circulating primarily in Venice and certain cities in Tuscany,Footnote 127 all of which enjoyed a significant Observant Dominican presence, the letter collections are a product of the particular interests and tastes of the fifteenth-century Dominican Observance. Tuscany and the Veneto were also two of the regions in which the humanist movement, with its revitalization of ancient epistolary forms,Footnote 128 was most established in the fifteenth century. Several scholars have noted humanist interest in Catherine's works,Footnote 129 and others have traced the connections linking humanists and Observants generally.Footnote 130 Indeed, the Observant efforts to reform contemporary society through an ad fontes approach to the foundational texts of the religious orders itself speaks to the cultural affinities that bound the Observant and humanist movements together. This cultural and regional overlapping perhaps helps to explain the Observant Dominicans’ concern in linking their movement to Jerome's ancient practice. As an early church father, and an ancient author who wrote in an eloquent Latin style, Jerome's legacy spoke to both humanist and Observant interests.

Focusing on German Augustinians, James Mixson has examined how Observant communities shaped their devotional lives through the production of manuscripts.Footnote 131 Although Mixson notes that the German Observants were interested in the patristic writers,Footnote 132 he emphasizes the attention they gave to copying and translating into the vernacular twelfth-century monastic treatises.Footnote 133 Silvia Mostaccio, on the other hand, has emphasized the importance of early Christian writers from the Eastern tradition to the intellectual and spiritual lives of fifteenth-century Observant Dominican women.Footnote 134 Two Florentine manuscripts, one compiled for a male community and the other female, demonstrate Mostaccio's thesis each by binding a letter of Catherine of Siena's with a treatise by the seventh-century desert hermit Isaac the Syrian.Footnote 135 Jerome, a patristic author who retreated to the desert, and spiritual director to women, was an attractive authority for this Observant form of spirituality.

The Observant friars themselves produced a great number of texts intended to provide religious instruction to the communities of religious women newly bound to the mendicant orders,Footnote 136 of which both the Dominican letters and the manuscripts in which they circulated must be considered a part. Nonetheless, despite the growing desire among many fifteenth-century Observant men to minister to women, as well as female fervor for the Observance,Footnote 137 the century also witnessed an increasing skepticism of female claims to spiritual authority, which often took the form of direct revelations from God.Footnote 138 As early as the fourteenth century, such skepticism was on the rise. Around 1340 Venturino of Bergamo, who maintained correspondences with several religious women, responded to a query from his fellow Dominican Egenolf of Ehenheim regarding the visions of a girl known to the German.Footnote 139 Venturino advised that he should assume the woman's experiences were the result of “diabolical illusion.” He then explained that he had had a similar encounter with a girl eight years previously. “It wholly seemed to me,” Venturino wrote, “that the Holy Spirit spoke through her mouth and seemed to predict much,” and that she had said the archangel Gabriel appeared to her. She apparently gained a widespread reputation for sanctity, since Venturino reports that people brought saints’ relics to her, and that her parents sold their wealth in order to build her an oratory.Footnote 140 However, Venturino cautions, returning to “that city” after two years: “I found that girl in a different condition and I realized with great certainty that everything about her had come forth from diabolic illusion.”Footnote 141 Egenolf, therefore, ought not readily put his trust in such matters.Footnote 142

Famously, in the 1390s, Raymond of Capua described many instances in his Legenda maior in which people criticized Catherine of Siena's ascetic practices and claims to divine revelation.Footnote 143 Catherine herself, in the 1370s, wrote at least one letter defending her fasting from a man in religion who warned that she may have been deceived by the devil.Footnote 144 After her death, influential theologians, like the chancellor of the University of Paris, Jean Gerson (d. 1429), argued that Catherine had been a lunatic and that Saint Bridget of Sweden “had not received her visions through the gift of the Spirit, because she had not expressed sufficient humility and obedience to her male superiors.”Footnote 145 The fifteenth century also witnessed the first accusations and trials of diabolic witchcraft, the suspects of which were overwhelmingly female. Meanwhile, those who wrote the earliest treatises and manuals on the subject were themselves Observant Dominicans.Footnote 146 Nevertheless, the female prophets who came to prominence as “living saints” in the princely courts of late fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century Italy were predominantly Dominican nuns and tertiaries.Footnote 147

The Observants’ ministry to women was then fraught with danger. Friars risked the perennial accusation from opponents that they were having illicit relations with their female charges and being led astray by the potentially insane or demonically possessed. The manuscript miscellanies examined in this article, then, are best understood within this context. By binding the letters to women of contemporary Dominican Observant beati with the letters Jerome had written to women one thousand years earlier, manuscript compilers sought to provide didactic materials for women under their pastoral care and simultaneously defend this aspect of Observant practice by linking it to early Christian precedent, particularly that of the desert fathers, with whom the Dominicans had long identified.

I argue that an important reason the letters that Dominican reformers and beati wrote to women survive in greater numbers than those they sent to men is that fifteenth-century compilers specifically selected them to be copied, in part so they could defend the Observant project by tying it to Jerome's patristic precedent. Indeed, in some cases the letter-writers themselves may have been involved in this act of publicity. Girolamo Savonarola, for example, printed three of his letters to women while he was still alive.Footnote 148 Furthermore, it is possible that some of the first generation of male Observant Dominicans looked to letters for guidance in providing pastoral care to religious women. Although most of the letters Venturino of Bergamo had written in the 1330s and 1340s survive in only a single manuscript,Footnote 149 one letter he wrote to a nun named Margherita is also extant in a parchment manuscript produced around 1402.Footnote 150 Although the manuscript has no colophon, making any certain attribution of its production difficult, when Laurent examined it in 1940 he compellingly suggested that all or part of it was compiled at Tommaso Caffarini's Venetian scriptorium in SS. Giovanni e Paolo.Footnote 151 In addition to Venturino's letter to Margherita, this Latin manuscript binds the vitae and translationes of other Dominican saints, and brings together a number of documents pertinent to the first generation of Dominican Observants operating around Venice: a pair of letters exchanged between Raymond of Capua and Giovanni Dominici, and Caffarini's vita of Maria of Venice. Scholars have seen Caffarini's vita in particular as part of an early Observant effort to create a more imitable model of sainthood than that of Catherine of Siena for the women in the newly organized Order of Penance.Footnote 152 Venturino's letter to Margherita complements Caffarini's vita, as throughout much of the letter he admonishes her against excessive abstinence and asceticism, while also exhorting her to do good works and to meditate on the Passion. The manuscript itself seems to have remained in male Dominican contexts; the earliest reference to the codex, for instance, places it at the Dominican house at Cividale del Friuli in the mid-eighteenth century.Footnote 153 Thus, I would suggest that Caffarini's workshop included Venturino's letter in this manuscript to model for friars how they might better provide spiritual guidance to penitent women, especially those who may have had what some friars would have considered excessive tendencies in their devotional practices. Just as these texts served didactic purposes directly for a female readership, they could also provide this function in shaping the devotional practices of female communities more indirectly by modeling for male readers how they might best fulfill their roles as spiritual fathers.

At least one manuscript, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence, Strozzi, MS 19, suggests the success of the Hieronymite model of sanctity beyond Observant circles.Footnote 154 This codex binds a letter that Antoninus wrote to Dada with a number of Hieronymite texts including his vita; Pseudo-Augustine's letter on Jerome's death to Cyril of Jerusalem; Jerome's real and falsified letters to Eustochium, Celantia, and the virgin Principia; a letter on prayer by Augustine to a widow; and another of Jerome's letters to a monk concerning contemptus mundi. These patristic (and chiefly Hieronymite) works are then followed by the vita of the Florentine martyr-saint Miniatus, a largely mutilated devotional tract, Brigitta Baldinotti's two letters of spiritual direction, and the lives of the Florentine Saints Zanobius and Apollonia.Footnote 155 This is another large book (314 x 228 mm) copied in a single mercantesca hand. Aesthetically, more than the other codices thus far examined, this book resembles a zibaldone, a book form that Petrucci has described as “the manifestation of an essentially nonbook mentality, appropriate for those whose graphic culture consisted especially of writing for business and private documentation, in which the book form . . . figured essentially as the container of evidence of more or less diverse times and natures.”Footnote 156

I propose that some members of one of fifteenth-century Florence's lay confraternities made this manuscript for their own personal use.Footnote 157 The mercantesca hand points to a mercantile or notarial context, gesturing toward the professional membership of such groups. And the colophon toward the end of the book, naming a whole list of individuals, suggests that this was not the personal property of one of the city's middle-class families.Footnote 158 Instead, it was likely used by a group of confraternity members. Such companies often began their meetings with a reading from a spiritual text,Footnote 159 a role any text in this manuscript could provide. That the membership of this group may have changed periodically is suggested by a scratched-out colophon directly above another surviving one; on the final page, the original scribe had added two hymns, underneath which a second hand declares: “This is the book of Giacomo di Lione and Giacomo di Piglis.”Footnote 160 The individuals who claimed ownership over this book were therefore men, and likely members of a lay confraternity. Nonetheless, their manuscript bound letters of spiritual direction explicitly addressed to women. In her examination of fourteenth-century Middle English meditations on the Passion, McNamer has argued that some writers sought to elicit compassion for the suffering Christ in their male and female readers, and that as these writers understood it, “to perform compassion is to feel like a woman.”Footnote 161 A similar dynamic might be at play in this fifteenth-century Florentine manuscript, in which its male audience was led to identify with the penitential women to whom the authors originally had addressed their letters.

The same pattern can also be seen recurring in the other manuscripts examined: one or more letters of spiritual direction a contemporary Dominican had addressed to women is bound with letters Jerome had written to women. The contents of these manuscripts did more than assist their readers and listeners in pious devotion; they also modeled the more contemporary authors after Saint Jerome. They represented the act of writing letters to female disciples as investing individuals like Antoninus with a penitential authority akin to Jerome's. This zibaldone, compiled in the middle of the fifteenth century for a group of male confraternity members, points to the broader acceptance of this Hieronymite model of sanctity among those outside strictly Observant contexts. Observants were drawn to the Hieronymite model of sanctity because he was an erudite desert hermit who ministered to women by writing them letters. The Observant Dominicans sought to justify their own pastoral work to women and elevate their movement's most prominent leaders by identifying them with Jerome's saintly legacy.

CONCLUSION

In 1500, the humanist Aldo Manuzio printed Catherine of Siena's letters from his workshop in Venice. A few years later, in 1507, the Olivetan monk Girolamo Scolari printed forty-three of the letters that the Dominican tertiary and holy woman Osanna Andreasi of Mantua (d. 1505) had written to him as an appendix to the vita he wrote in her honor.Footnote 162 Two extant manuscripts bind dozens of letters to religious women that Domenico Benivieni, a disciple of Savonarola, had written in the 1490s.Footnote 163 And Zarri has recently edited the letters of spiritual direction that the priest Leone Bartolini, who was himself under the spiritual care of the Dominican Vincenzo Arnolfini, wrote to a group of Bolognese aristocratic women from the 1540s to the 1560s.Footnote 164 By the sixteenth century, then, not only did the composition and collection of letters of spiritual direction continue, but some old and new collections were now being printed for the purpose of reaching wide and diverse publics. Yet several continuities from the fifteenth century persisted: namely, the predominantly Dominican context of the letters, and their embodiment of the gender dynamics between spiritual directors and disciples.

In this paper I have examined Observant Dominican letters of spiritual direction within their manuscript contexts in fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century Italy. I demonstrated that in many cases compilers bound Dominican letters to women with those which Jerome had written to his female disciples. I contextualized this practice within the Dominican tradition of identifying with the desert fathers, among whom they considered Jerome a part, and the fifteenth-century Observant Dominican effort to reinforce this identification. Furthermore, the Dominicans took special interest in advancing Jerome's cult, translating his letters into Italian and penning new texts in his honor. I suggest that by binding the letters to women written by leaders of the Dominican Observance with Jerome's letters, compilers sought to model the sanctity of contemporary letter-writers after that of the fifth-century church father. This served two purposes: first, it helped compilers and readers cultivate an Observant identity that traced its lineage back to the earliest Christian centuries. The compilations provided a framework to help Observants and those within their orbit shape their spiritual and devotional practices, as well as model the relationships between typically male spiritual directors and female disciples. By drawing specifically on the ancient example of Jerome's relationship with Eustochium, Paula, and the other women of their community, the Observant men and women could imagine themselves as reviving the rigorous ascetic and devotional practices of past centuries. This was one way in which the Observants participated in the broader retrieval and imitation of the ancient past—an antiquity that was understood to be Christian, as well as pagan—that characterized much of fifteenth-century cultural activity. Second, by linking themselves to Jerome's practice of ministering to penitent women, Dominican Observants could justify and defend their pastoral work with women as steeped in the patristic tradition. This was all the more necessary as from the middle decades of the fourteenth century female claims to holiness had come under greater scrutiny as potentially demonic in origin. The compilers of these miscellaneous letter collections therefore sought to develop further an Observant identification with the church fathers and to defend their contemporary work with women.