In the first movement of Brahms’s autumnal masterpiece from 1891, the Clarinet Trio in A minor, op. 114, occurs a seemingly anomalous passage peculiar for its brevity, distinctive harmonic contours, spacing, and modal implications – a series of compact parallel 6/3 chords eerily ushered in by the piano a little way into the development. Brahms has begun that section in the dominant E minor with the opening theme of the trio, before asserting through a rising chromatic sequence a dramatic, forceful statement of the same theme a whole step above, in F-sharp minor. Within seven bars, the music subsides, and here we encounter these spectral first-inversion chords, repeated a few bars later a fifth lower (Ex. 1a; bars 97ff.). To be precise, undergirding the chords are bass notes in the cello, first a C![]() acting as dominant of F

acting as dominant of F![]() , and then an F

, and then an F![]() , initially as dominant of B minor. The 6/3 chords seem to float above the static bass line, so that the listener hears them not as freestanding or self-sufficient, but rather as hanging above a bass line that directs the harmonic narrative. But shortly after the key signature reverts to A minor (bar 119), Brahms deploys the same kind of harmonies, this time stated forte in the piano (Ex. 1b, bars 121–123), and transposed to reinforce the return of the tonic and its elision with the recapitulation, which, technically speaking, begins not with the opening theme of bar 1 but rather the triplet figure of bar 13, now affirmed with fortissimo double stops in the cello and forte triplets in the piano. In this second incarnation of the 6/3 chords they appear explicitly as unambiguous first-inversion harmonies, even if splayed across a span of several octaves, and are now extended to encompass fully twelve chords, as a reduction of the passage readily demonstrates (Ex. 1c, bars 121–125).

, initially as dominant of B minor. The 6/3 chords seem to float above the static bass line, so that the listener hears them not as freestanding or self-sufficient, but rather as hanging above a bass line that directs the harmonic narrative. But shortly after the key signature reverts to A minor (bar 119), Brahms deploys the same kind of harmonies, this time stated forte in the piano (Ex. 1b, bars 121–123), and transposed to reinforce the return of the tonic and its elision with the recapitulation, which, technically speaking, begins not with the opening theme of bar 1 but rather the triplet figure of bar 13, now affirmed with fortissimo double stops in the cello and forte triplets in the piano. In this second incarnation of the 6/3 chords they appear explicitly as unambiguous first-inversion harmonies, even if splayed across a span of several octaves, and are now extended to encompass fully twelve chords, as a reduction of the passage readily demonstrates (Ex. 1c, bars 121–125).

Ex. 1a Brahms, Clarinet Trio, op. 114, I, 97–105

Ex. 1b Brahms, Clarinet Trio, op. 114, I, 121–125

Ex. 1c Brahms, Clarinet Trio, op. 114, I, 121–125 (Reduction)

Late in the movement, in the coda marked Poco meno Allegro, Brahms revives for a last time the 6/3 chords, but now they emerge freely in a purely modal configuration of four chords without accidentals, heard in closed position in the piano (Ex. 1d, bars 213–214), as if he has deliberately slipped into the pure Aeolian mode. Nevertheless, the magical closing bars offer an unexpected modification: here the composer gently insinuates the pitch C![]() , so that the movement indeed ends with calming A-major chords, even though the ‘final’ cadence is anything but tonal. Rather, Brahms progresses from a G-seventh chord to A major, as the outer voices move in contrary motion from the seventh, G–F, to the fifth, A–E, like some distant, unfamiliar modal cadence. With the lowered seventh degree G ascending to the ‘finalis’ A, one might imagine an Aeolian cadence, but the insertion of the C

, so that the movement indeed ends with calming A-major chords, even though the ‘final’ cadence is anything but tonal. Rather, Brahms progresses from a G-seventh chord to A major, as the outer voices move in contrary motion from the seventh, G–F, to the fifth, A–E, like some distant, unfamiliar modal cadence. With the lowered seventh degree G ascending to the ‘finalis’ A, one might imagine an Aeolian cadence, but the insertion of the C![]() brings briefly into play the augmented fourth, G–C

brings briefly into play the augmented fourth, G–C![]() , as if to activate momentarily in the ear a new-fangled Lydian association. And the voice-leading of the outer voices, which contract from a seventh to a fifth, perhaps suggests an uncanny reconfiguring of a cadence in the Phrygian mode: instead of a sixth expanding by contrary motion to an octave, the seventh collapses by contrary motion to a fifth.

, as if to activate momentarily in the ear a new-fangled Lydian association. And the voice-leading of the outer voices, which contract from a seventh to a fifth, perhaps suggests an uncanny reconfiguring of a cadence in the Phrygian mode: instead of a sixth expanding by contrary motion to an octave, the seventh collapses by contrary motion to a fifth.

Ex. 1d Brahms, Clarinet Trio, op. 114, I, 213–214

The unanticipated conclusion of the movement in the major mode is a familiar conceit that Brahms applied in a number of late works, including the first movement of the Violin Sonata in D minor op. 108 (1886), second movement of the second String Quintet op. 111 (1890), and first movement of the Viola Sonata in F minor op. 120 no. 1 (1894), for example. It could perhaps be understood as a historicist gesture, the use of the Baroque tierce de Picardie to provide a stronger, more stable (and tonal) sense of closure and resolution than that afforded in op. 110 by A minor, used in swaths of the movement in its natural minor or Aeolian modal version. It could be understood as a chromatic adjustment to bring the movement, finally, back into the chromatic tonality of Brahms’s time. Or, to use a Riemannian approach, it could be understood as evidence of the composer’s fascination with so-called ‘minor-major’ and ‘major-minor’ scales – here, more precisely, a scale that uses a major tetrachord (A–B–C![]() –D) and Phrygian tetrachord (E–F–G–A).Footnote

1

But what about the 6/3 chords? They sound suspiciously, and sometimes are described in the literature,Footnote

2

as if Brahms momentarily found himself transported into the archaic world of fauxbourdon. It is as if this late effort of the composer was meant to revisit, if only fleetingly, music from centuries well removed from him – music, say, of the fifteenth or early sixteenth centuries, a historical era at best only vaguely perceived and understood in the 1890s by Brahms’s contemporaries – even while the composer was contending with the critical late stage of nineteenth-century tonality, ineluctably dissolving as it was at the century’s close.

–D) and Phrygian tetrachord (E–F–G–A).Footnote

1

But what about the 6/3 chords? They sound suspiciously, and sometimes are described in the literature,Footnote

2

as if Brahms momentarily found himself transported into the archaic world of fauxbourdon. It is as if this late effort of the composer was meant to revisit, if only fleetingly, music from centuries well removed from him – music, say, of the fifteenth or early sixteenth centuries, a historical era at best only vaguely perceived and understood in the 1890s by Brahms’s contemporaries – even while the composer was contending with the critical late stage of nineteenth-century tonality, ineluctably dissolving as it was at the century’s close.

The Clarinet Trio offers several passages that chromatically stretch the tonality of Brahms’s ‘present’, the 1890s, and that can be analysed in tonal terms, but the senescent composer places those passages in tension with haunting applications of modality that seek to converse with music of a distant past, an allusive, musical alternative ‘other’ to that present. And the way in which Brahms introduces the 6/3 chords – first as chromatic sonorities hovering above sustained pitches in the cello, then spread across several octaves in the piano against figurations in the clarinet and cello, and finally (and only then) in the piano alone in the most simple, archaic, diatonic modal form – suggests that the composer designed them to be apprehended by the listener in a gradual way. That is to say, by the third iteration of the chords, the allusion to fauxbourdon has come into increasingly stronger focus; what begins as a series of 6/3 chords above a bass line increasingly approaches the archaic quality of fauxbourdon.

To relate Brahms’s compositions to early music is a familiar enough pastime of scholars, though generally those efforts have centred on the later Renaissance and baroque.Footnote 3 To search for earlier models did inspire at least one notable, if provocative, attempt. In 1983, during the sesquicentennial of Brahms’s birth, the theorist David Lewin published an analysis of the Intermezzo in E minor, op. 116 no. 5 (1891), in which he argued that Brahms’s metrical adjustments could be likened to Franconian mensural manipulations. Lewin suggested that the first ten bars, shaped by persistent iterations of an eighth-note anacrusis, eighth note, and eighth-note rest, invoked the characteristic pattern of mode 2 (short–long, Ex. 2), while the measures following the second ending in bar 12 accomplished in effect a metrical modulation to mode 1 (long–short). In addition, this shift from the second to first rhythmic mode aligned neatly with Brahms’s shift from the tonic E minor to dominant B major. Lewin was careful to admit that he could not adduce any hard evidence of Brahms’s interest in Franconian notation, though in an appendix the theorist did amass some intriguing circumstantial evidence: for example, Brahms would have had access to Wilhelm Ambros’s Geschichte der Musik which discusses mensural theory (a new edition appeared in 1891, the year of the Intermezzo), and Brahms was certainly familiar with the writings of Heinrich Bellermann, who had published in the 1868 and 1870 volumes of the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung several articles about Franco’s Ars cantus mensurabilis, mensural notation, and fourteenth-century consonance treatment.Footnote 4

Ex. 2 Brahms, Intermezzo, op. 116 no. 5, 1–2

Be that as it may, the first movement of the Clarinet Trio is arguably a work that invokes time – historical time – and reminds us, as Lewin observed, that Brahms’s ‘musical past has a special kind of immanence for us’.Footnote 5 The composer’s strategy seems to have been to place in paradoxical juxtapositions different ‘historical modes of thought’, and then to explore a ‘dialectical synthesis of musical contradictions’Footnote 6 while he navigated between the musical present and past – or, more precisely, in the case of the trio, the distant past. Brahms had, of course, strong historical musical interests – the composer’s friend and Bach scholar Philipp Spitta observed in 1892 that no musician was more well-read (belesener) than BrahmsFootnote 7 – though his historical memory, like that of most of his contemporaries, generally extended only as far as across the eighteenth and seventeenth centuries to the sixteenth. Still, he subscribed to an early musicological journal founded by Guido Adler, Friedrich Chrysander, and Philipp Spitta, the Vierteljahrsschrift für Musikwissenschaft,Footnote 8 which ran from 1885 to 1894. There he could have availed himself of various recondite contributions such as Franz Xaver Haberl’s extended monograph on Guillaume Dufay, or, indeed, to supplement Lewin’s circumstantial evidence, Oswald Koller’s study of the eleventh chapter of Franco’s Ars cantus mensurabilis, though whether Brahms did so is unknown.Footnote 9 Among the treatises in his library was Bellermann’s Der Contrapunkt (1862), which contained an extensive discussion of the church modes, including their transposed versions, and a table that summarized from various (though unidentified) sixteenth-century writers the melodic character of each mode.Footnote 10 Here Brahms would have noted, for example, that the Aeolian (modus nonus) was somehow suavis (sweet), but the Hypoaeolian (modus decimus) tristis (sad), while the Phrygian (modus tertius) was austera (pungent).

Brahms’s library also included a copy of Carl von Winterfeld’s substantial three-volume monograph Johannes Gabrieli und sein Zeitalter (Berlin, 1834), of which the first volume contained a rich chapter devoted to the church modes. Brahms clearly read this material, as his occasional annotations and markings show. In the view of Hartmut Krones, Winterfeld went well beyond a mere description of the church modes, to develop ‘an almost functioning modal system that linked the individual modes in an overarching polymodal structure’.Footnote 11 Winterfeld viewed individual modes as forming relationships with others – thus the Mixolydian, with its lowered seventh, was related to the minor third of the Dorian, allowing shifts from one mode to another, a process that would not have been lost on Brahms, who, as we shall see, was not at all reluctant to experiment with modal mixtures in his own music.

Brahms’s library of ‘early’ music was extensive, as the pioneering research of Virginia Hancock and others has shown,Footnote 12 and he collected first editions and autographs of composers ranging from Domenico Scarlatti to Wagner. Brahms owned Gesamtausgaben of composers such as Schütz and Handel; and he followed closely the progress of the Gesamtausgabe begun by the Bach-Gesellschaft in 1850, and, in the case of the Schubert Werke issued between 1884 and 1897, directly participated by editing the symphonies. His circle included several scholars with musicological interests, not just Philipp Spitta (Brahms dedicated to him the historicist, modally tinged Motets op. 74 of 1879), but also Otto Jahn, author of a three-volume biography of Mozart; Eusebius Mandyczewski, editor of Schubert’s Lieder and later instrumental in launching the first attempt at a complete Haydn edition; Gustav Nottebohm, best known for his pioneering work on compositional process in Beethoven, but also the compiler of six volumes of Abschriften alter Musik possessed by Brahms – primarily instrumental works from the sixteenth through eighteenth centuries, though containing also a Kyrie of Palestrina and psalm setting of Clemens non Papa;Footnote 13 and Guido Adler, whose doctoral students in musicology at the University of Vienna later included Anton von Webern.

During the 1850s the young Brahms diligently exchanged with Joseph Joachim counterpoint exercisesFootnote 14 rigorous enough to encompass mirror canons and double counterpoint at various intervals – pastimes certainly viewed by others as recherché and remotely separated from the tastes of the musical present. For Brahms these pursuits were not pedantic curiosities destined for museums, but rather part of a living historical tradition. And so in the fourth variation of the Haydn Variations (1873), he crafted a consummate example of double counterpoint at the twelfth, perfectly realized to observe the rules of eighteenth-century theorists such as Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg, who had bothered to explicate the technique, and yet musically satisfying and convincing to a later nineteenth-century audience, whose musical preferences generally did not extend to intricate contrapuntal gambits.

In a category unto itself among Brahms’s historical interests was his collection of Octaven und Quinten, a sort of historical review of peccadillos (or worse) in voice leading committed by major European composers.Footnote 15 Here Brahms must have sensed the broad historical purview of the prohibition against fifths and octaves, and have understood that it originated not in the common practice period of recent centuries, but reached back to the early history of polyphony. Paul Mast has surmised that Brahms worked on this collection at various times in his career, beginning probably in 1863 or 1864, but continuing in particular during the 1890s, when he gleaned several examples, some of them actually culled from his readings in the Vierteljahrsschrift für Musikwissenschaft. The composer collected more than 100 specimens, ranging from Clemens non Papa, Palestrina and Marenzio in the sixteenth century to Bizet’s Carmen (1875), a work that so piqued Brahms’s curiosity that he saw it more than 20 times, its voice leading notwithstanding. But his primary reason for collecting fifths and octaves probably had to do with a debate that had erupted in the 1850s and 60s challenging the centuries-old rule prohibiting such parallelisms. Those arguing for a relaxation of the proscription, including August Wilhelm Ambros and especially Carl Friedrich Weitzmann,Footnote 16 tended to align with the movement loosely known as Zukunftsmusik, the ‘progressively’ minded circle of figures associated with the Lisztian-Wagnerian camp. Though situated on the other side of the great aesthetic divide in Austro-German music, Brahms seems to have been concerned not so much with strictly upholding the traditional prohibition as with understanding why in some musical contexts a composer such as Mozart or Beethoven could produce passable fifths that were indeed pleasing or beautiful, while others could not. In short, Brahms understood ‘the usefulness of rules, while recognizing that the pursuit of style requires the liberty to break them’.Footnote 17 And that distinction brings us back, however circuitous the route, to the Clarinet Trio.

One set of questionable fifths the composer notated in his collection was from a nondescript piano trio by A. W. Ambros, which the theorist had introduced in his essay of 1859 with this explanation:

To be sure, according to that school, fifths reside in an even deeper region of hell than cross-relations or octaves – the latter can at least be shown to be ‘doubling’ – fifths never! But then what if, for example, one were to allow a progression of sixth chords to storm downwards in two registers?

In fact, successive fifths do of course result, but the ear does not let itself be deceived; it hears only fourths with underlying sixths. Thus I too (et ego in Arcadia!Footnote 18 ) have written the following beginning for the Minuet of my D-major Trio, op. 6, without particular pangs of conscience:Footnote 19

But here Brahms was unimpressed with Ambros’s voice leading, and added the dismissive comment, ‘When and where one finds consecutive fifths that are actually bad, usually everything else is equally bad, so that the one fault is beyond consideration’.Footnote 20 And, revealingly, when it came to Brahms’s own successive, doubled sixth chords in bars 121ff. of the first movement of the Clarinet Trio (see Ex. 1b), he took care to adjust the voice leading (through contrary motion in the inner voices) in order to avoid Ambros’s Arcadian, but for Brahms offending, fifths. To Brahms’s ears the sixth chords were thus freighted with historical modes of musical discourse – with the archaic sound world of fauxbourdon, but also, in the case of the chords doubled in different registers, with the centuries-old issue of fifths.

These fauxbourdon-like passages occupy only a few, fleeting moments of the 224 bars of this movement, and one would err in attaching undue significance to them, were it not for Brahms’s introduction of other modal features in the Allegro. A quick review of the opening thematic complex demonstrates how skilfully he interwove modally inflected themes and materials into a composition with which audiences in 1891 would still have grappled to understand as tonal. Part of what gives the movement its special, archaic aura is Brahms’s calculated decision to minimize strong assertions of the dominant-to-tonic function and raised leading tones familiar in tonal contexts. Instead, he tends to highlight a pull to the minor subdominant (the Riemannian Unterdominant),Footnote 21 effectively at times connecting, as Margaret Notley has observed, ‘the plagal subsystem with the scale of a church mode’,Footnote 22 in this case the Aeolian.

The very opening of the Trio (Ex. 3a, bars 1–12), in which the cello subject ascends from the tonic A and is then answered a few bars later by the clarinet entering a fifth above on E, is sometimes likened to a fugal opening, with a subject and tonal answer pairing. But there is no third entrance in the piano that might reinforce or confirm a fugal opening – rather we hear low, somnolent bass notes and octaves. The imitation between the cello and clarinet does suggest a dux-comes instance of paired imitation, but most likely Brahms was thinking here not of fugal counterpoint but of modal Renaissance polyphony or some semblance thereof. True, the cello theme begins with a seemingly clear enough tonal gesture, an ascending A-minor arpeggiation, but it then introduces on the downbeat of bar 2 a G![]() as the lowered seventh scale degree, before proceeding through a measured scale-like descent that, punctuated by pauses on E and A, articulates the two tetrachords of the Aeolian mode, A–B–C–D and E–F–G–A (see the reduction of bars 1–4 in Ex. 3b).

as the lowered seventh scale degree, before proceeding through a measured scale-like descent that, punctuated by pauses on E and A, articulates the two tetrachords of the Aeolian mode, A–B–C–D and E–F–G–A (see the reduction of bars 1–4 in Ex. 3b).

Ex. 3a Brahms, Clarinet Trio, op. 114, I, 1–12

Ex. 3b Brahms, Clarinet Trio, op. 114, I, 1–4 (Reduction)

A tonal beginning thus quickly metamorphoses into a modal gesture, establishing at the outset a tonal/modal ambivalence – the musically familiar confronts the unfamiliar and archaic – and this ambivalence in turn influences in many ways the course of the movement. If the cello’s lowered seventh degree, its ambitus extending from a to a′, and its lack of chromatic inflection are markers of the Aeolian mode, the clarinet’s answering material, with its ambitus spanning e to e′, suggests momentarily a change of mode to the Hypoaeolian. The only chromatic pitch that disturbs this hauntingly bland opening is the C![]() in the piano in bar 10, reiterated by the clarinet in bar 12. In the absence of clearly tonal harmonic progressions, the C

in the piano in bar 10, reiterated by the clarinet in bar 12. In the absence of clearly tonal harmonic progressions, the C![]() might impress as an interloper from modernity, for it does not belong to the Aeolian realm. But if we consider Brahms’s modal opening at the tetrachordal level, the purpose of the C

might impress as an interloper from modernity, for it does not belong to the Aeolian realm. But if we consider Brahms’s modal opening at the tetrachordal level, the purpose of the C![]() perhaps becomes clear. What Brahms effectively does here is to manipulate a series of shifting tetrachords: the C

perhaps becomes clear. What Brahms effectively does here is to manipulate a series of shifting tetrachords: the C![]() redefines the Aeolian tetrachord A–B–C–D as A–B–C

redefines the Aeolian tetrachord A–B–C–D as A–B–C![]() –D, establishing a modal ambivalence (Aeolian versus, say, transposed Mixolydian) on which the composer plays in the piano triplets of bars 13–18, before transforming the Hypoaeolian E–F–G–A into E–F

–D, establishing a modal ambivalence (Aeolian versus, say, transposed Mixolydian) on which the composer plays in the piano triplets of bars 13–18, before transforming the Hypoaeolian E–F–G–A into E–F![]() –G

–G![]() –A in bars 17–18 (Ex. 4, bars 13–18). In turn, these tetrachords likely factored into Brahms’s decision to downplay tonal progressions with root movements by fifth in favour of plagal progressions with root movements by fourth (D minor to A major in bars 10–11 and 18, or, at the end of the exposition, A minor to E minor in bars 79–82). So the deeper harmonic substructure of the music reinforces the more localized parsing of motivic and thematic materials into tetrachords, and, in turn, intensifies the modal coloration of the music.

–A in bars 17–18 (Ex. 4, bars 13–18). In turn, these tetrachords likely factored into Brahms’s decision to downplay tonal progressions with root movements by fifth in favour of plagal progressions with root movements by fourth (D minor to A major in bars 10–11 and 18, or, at the end of the exposition, A minor to E minor in bars 79–82). So the deeper harmonic substructure of the music reinforces the more localized parsing of motivic and thematic materials into tetrachords, and, in turn, intensifies the modal coloration of the music.

Ex. 4 Brahms, Clarinet Trio, op. 114, I, 13–18

For nineteenth-century composers seeking to instil in their music a modal character, the Aeolian mode was a tempting choice, owing to its practical theoretical recognition as the natural form of the modern minor scale. To slip from a minor key in a tonal context into a modal orientation admitting an Aeolian (or transposed Aeolian) reading required, compositionally speaking, relatively few adjustments. And so, when in 1846 Mendelssohn composed his setting of the sequence Lauda Sion for the six-hundredth anniversary of the feast of Corpus Christi, he first retouched and reworked the original Mixolydian plainchant so that it could assume an Aeolian guise (Ex. 5a and 5b), but then placed the transformed Aeolian chant in the tonal context of A minor. The ancient cantus firmus appears twice, in the fifth and sixth movements of Mendelssohn’s composition, centred textually on the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation: first the melody emerges in a homophonic setting (‘Docti sacris institutis’), and then in a chorale fugue (‘Sub diversis speciebus’). In the latter the choral parts enter in a point of imitation patently meant to suggest the stile antico of Palestrina. Brahms would not have known Mendelssohn’s chorale fugue, for it was included neither in 1849 as op. 73, the first of Mendelssohn’s posthumous compositions to appear, nor in the collected edition of his works issued by Breitkopf & Härtel between 1874 and 1877, to which Brahms did have access.Footnote

23

But had Brahms studied the fifth movement, he would have noticed that Mendelssohn worked into the accompaniment to the chant several chromatically raised leading tones, and, indeed, at the close of the chant raised the seventh scale degree to G![]() , effectively neutralizing the Aeolian flavour of the melody, so that the movement could be perceived and understood to be in the key of A minor. In short, if the Aeolian markers of the revised chant challenged, they nevertheless did not subvert the overriding key of A minor.

, effectively neutralizing the Aeolian flavour of the melody, so that the movement could be perceived and understood to be in the key of A minor. In short, if the Aeolian markers of the revised chant challenged, they nevertheless did not subvert the overriding key of A minor.

Ex. 5a Lauda Sion (Mixolydian chant)

Ex. 5b Lauda Sion (Aeolian revision), as used in Mendelssohn, Lauda Sion, op. 73

Mendelssohn was after the effect, the allure of an ‘ancient’ mode – in order to pose a musical alternative that might conjure up the ancient mysteries of transubstantiation conveyed in the verses of Thomas Aquinas. But the composer was unwilling to loosen completely the tonal moorings of his music. As a whole, the end movements of Lauda Sion begin and end in a warm C major. The use of modality, or rather tempered modality, impresses as an excursion placed parenthetically within the tonal parameters of the entire work. This process of ‘thus far, but no further’ betrays an attitude that seems to have been shared by Robert Schumann, who on occasion also explored modal enigmas of his own devising. The locus classicus of his experiments in this direction would probably be ‘Auf einer Burg’, the seventh Lied from the Eichendorff Liederkreis, op. 39 (1840), a work with which Brahms certainly would have been quite familiar.

Scholars have puzzled over how to analyse this remarkable strophic setting.Footnote

24

The lack of key signature might argue for A minor as the tonic, were it not for the distinctive opening in a deliberately archaic style, with falling fifths (B–E and E–A) shared by the voice and piano, like a point of imitation in stile antico (Ex. 6, bars 1–3). The orientation of the opening bars toward E, supported by the raised F![]() progressing to G, could argue for E minor, but Schumann subsequently lowers the raised second degree to an F

progressing to G, could argue for E minor, but Schumann subsequently lowers the raised second degree to an F![]() just a few bars later, suggesting instead that he envisioned here a Phrygian hue. Whatever the case, the antiquated, obsolescent style is clearly driven by the text. Eichendorff’s poem describes an ancient, petrified knight, who has slumbered for centuries in his castle on a peak overlooking a valley. To convey the vast stretch of time, Schumann obliges with hints of modality, and a static type of music that neither pursues nor reaches a tonal goal. And yet the music is not quite Phrygian, not quite Aeolian, and not quite in the key of A minor or E minor – rather, it occupies an ambiguous ‘no man’s land’ somewhere between modality and tonality, shifting aimlessly between past and present. When the song closes inconclusively on an E-major chord, Schumann almost seems to be inviting us to complete an authentic cadence by imagining a final A-minor sonority, thereby satisfying our ‘need’ to be anchored in a tonal ‘present’.

just a few bars later, suggesting instead that he envisioned here a Phrygian hue. Whatever the case, the antiquated, obsolescent style is clearly driven by the text. Eichendorff’s poem describes an ancient, petrified knight, who has slumbered for centuries in his castle on a peak overlooking a valley. To convey the vast stretch of time, Schumann obliges with hints of modality, and a static type of music that neither pursues nor reaches a tonal goal. And yet the music is not quite Phrygian, not quite Aeolian, and not quite in the key of A minor or E minor – rather, it occupies an ambiguous ‘no man’s land’ somewhere between modality and tonality, shifting aimlessly between past and present. When the song closes inconclusively on an E-major chord, Schumann almost seems to be inviting us to complete an authentic cadence by imagining a final A-minor sonority, thereby satisfying our ‘need’ to be anchored in a tonal ‘present’.

Ex. 6 Robert Schumann, ‘Auf einer Burg’, Eichendorff Liederkreis, op. 39 no. 7, 1–3

Mendelssohn’s Lauda Sion and Schumann’s ‘Auf einer Burg’ illustrate how two of Brahms’s predecessors occasionally traversed the boundaries between modality and tonality. There is evidence that Brahms pursued a similar tactic before exploring further the frontiers of modal meanderings in his late works. Twelve years before the Clarinet Trio, he found another occasion to invoke the Aeolian mode in the Intermezzo in A minor op. 76 no. 7 (1879). Here, the opening theme of the piano miniature moves by ascending fourth, from E to A, before continuing scale-like, through the lowered seventh degree, to state the descending form of the mode in the opening eight bars (Ex. 7, 1–8). If we consider just the soprano theme, it would seem to impress almost as a Vorstudie for the opening bars of the Clarinet Trio; without the ascending A-minor arpeggiation of the trio. But there is a critical difference between the two examples. In op. 76 no. 7, Brahms challenges the modal flavour through persistent repetitions of the half step D![]() –E, with its raised leading tone, and also introduces the raised leading tone G

–E, with its raised leading tone, and also introduces the raised leading tone G![]() and its supporting dominant harmony. True enough, the authentic V–i cadence is magically distorted by the passing C octave in the bass, but several tonal prompts, all but minimized in the opening of the Clarinet Trio, are periodically activated in the Intermezzo. And the extended, conspicuously chromatic middle section of this ABA′ miniature leaves behind the Aeolian mood of the opening to advance a tonal reading of the piece for some thirty bars, until the composer re-invokes the mode in the closing eight bars of the composition. The ternary-form ABA thus encapsulates the tonally developed central section – the principal portion of the piece – within two short, epigram-like references to an ancient modality.

and its supporting dominant harmony. True enough, the authentic V–i cadence is magically distorted by the passing C octave in the bass, but several tonal prompts, all but minimized in the opening of the Clarinet Trio, are periodically activated in the Intermezzo. And the extended, conspicuously chromatic middle section of this ABA′ miniature leaves behind the Aeolian mood of the opening to advance a tonal reading of the piece for some thirty bars, until the composer re-invokes the mode in the closing eight bars of the composition. The ternary-form ABA thus encapsulates the tonally developed central section – the principal portion of the piece – within two short, epigram-like references to an ancient modality.

Ex. 7 Brahms, Intermezzo in A minor, op. 76 no. 7, 1–8

We do not know why Brahms chose to juxtapose modal and tonal readings in this particular Intermezzo, but in the case of the early Lied ‘Von ewiger Liebe’ op. 43 no. 1 (composed in 1864), the opening invocation of the Aeolian mode (here, transposed B-Aeolian, Ex. 8, bars 5–12) was triggered by the folk text, a German translation ‘nach dem Wendischen’, that is, after the Wends, Western Slavs living near German realms. Here the Aeolian mode rests in an uneasy alliance with B minor: the major form of the dominant does appear with its raised A![]() , challenging the potency of A

, challenging the potency of A![]() , the lowered seventh degree of the Aeolian; what is more, ultimately the song moves and concludes in the luminous key of B major with an authentic cadence. But, along with other examples that could be adduced,Footnote

25

‘Von ewiger Liebe’ returns us to the central issue relevant to our discussion of Brahms’s late modal experiments, namely, the purpose of his creative investment in modality.

, the lowered seventh degree of the Aeolian; what is more, ultimately the song moves and concludes in the luminous key of B major with an authentic cadence. But, along with other examples that could be adduced,Footnote

25

‘Von ewiger Liebe’ returns us to the central issue relevant to our discussion of Brahms’s late modal experiments, namely, the purpose of his creative investment in modality.

Ex. 8 Brahms, ‘Von ewiger Liebe’, op. 43 no. 1, 1–12

To trace the full course of Brahms’s modal applications, an endeavour far beyond the scope of the present essay, is to realize that modality was in fact a compositional tool that he used throughout his career, in various genres, texted and un-texted. But why did he resort to it? Most likely, several motivations stimulated his modal imagination. Drawing on music throughout Brahms’s oeuvre, Nicole Biamonte has attempted to place these stimuli into broad categories, while Joachim Thalmann has investigated historical contexts for Brahms’s modal experiments by focusing on the composer’s early music.Footnote 26 The aura of folk music, as in ‘Von ewiger Liebe’, was undoubtedly one significant source. Brahms was an avid collector of folksongs, and his interest in folk music, whether, say, of German or Scandinavian origin, of course would have exposed him to modal settings. One might imagine too that the style hongrois, to which the Hungarian violinists Eduard Reményi and Joseph Joachim introduced Brahms during the 1850s, could have been a factor in leading him to modes, but Biamonte rejects that possibility, since ‘Brahms’s style hongrois is fundamentally tonal; he makes no use of the gypsy minor scale – harmonic minor with raised 4 and/or lowered 2 – or other constructs with modal implications’.Footnote 27 On the other hand, turning to the north, Thalmann argues for the influence of Scandinavian folk music on the young Brahms. Thalmann rightly points out that during the 1840s the composer’s native city, Hamburg, was in ‘close cultural proximity to Scandinavia’,Footnote 28 especially to Denmark, since the neighbouring community of Altona was still under Danish control. Musicians such as Jenny Lind, who routinely offered Swedish folksongs as encores, and Ole Bull, whose specialty was playing the Hardanger folk fiddle (it later influenced the modal Norwegian nationalist idioms of Edvard Grieg), were well received in the Hanseatic port city.

Extrapolating this line of argument, Thalmann suggests that Brahms’s own initial forays into modality reflected his ready access to Scandinavian folk music and that, moreover, one may speak of a ‘Nordic tone’ in his earliest music.Footnote 29 Here Thalmann presents as a critical influence the Nachklänge von Ossian Overture op. 1 of the Danish composer Niels Gade (1840), a work well received in German realms after its premiere at the Leipzig Gewandhaus in 1842.Footnote 30 The young Brahms may well have regarded this overture as Nordic,Footnote 31 or perhaps drawing on or simulating folk music, but its title, of course, alluded to the supposedly ancient Celtic poems from the third century bce that had been ‘rediscovered’ by James Macpherson in the 1760s, setting off the European vogue of Ossian. Even though unmasked by Samuel Johnson early on as a literary forgery, Macpherson’s fictive creations of epic Celtic poetry somehow endured as ‘the most successful literary falsehood in modern history’.Footnote 32 By the 1840s Ossian still had enough allure to fire Gade’s imagination in Denmark, and he produced an orchestral composition that, indeed, began with block modal sonorities, before introducing a plaintive melody, almost all of it in an unaltered Aeolian mode (Ex. 9, principal theme).

Ex. 9 Gade, Nachklänge von Ossian, op. 1, Principal Theme

Was Gade invoking folk music, a Nordic tone, or what the late John Daverio and I have separately described in the music of Schumann and Mendelssohn as an Ossianic manner?Footnote 33 Possibly all. Anna Celenza has traced one source of the melody to the Danish folksong ‘Ramund var sig ne bedre mand’.Footnote 34 One other significant influence on Gade was neither unadulterated folk music nor a distinctly Nordic tone, but the Hebrides Overture of Mendelssohn,Footnote 35 known to Gade from its publication in score in 1835 as the Fingal’s Cave Overture, a title that had the effect of strengthening that work’s Ossianic pretensions. Be that as it may, Gade was certainly trying to invoke an ancient, bardic age well removed from the nineteenth century, and this quest to capture an exotic, alternative musical ‘other’ would not have escaped the young Brahms. Indeed, in 1861 he composed his own, lament-like Ossianic setting, the Gesang aus Fingal, published the following year as op. 17 no. 4, and based on a German translation of a passage from the first book of Fingal.Footnote 36 Enhancing the Ossianic qualities of Brahms’s work was its unusual scoring for female chorus, two natural horns and harp (here the latter instrument makes a rare but fitting appearance in Brahms’s music – like Homer, the bard Ossian supposedly sang his poetry accompanied by a harp). But equally conspicuous is the turn to modality: in the outer sections, C-transposed Aeolian (with the lowered seventh degree, B♭; Ex. 10, bars 1–8), and in the central section, with a key signature of four flats, A♭-transposed Mixolydian (with lowered seventh degree, G♭). Except for an occasional outburst from the dampened pianissimo horns, and the occasional raised leading tone that brings us into the tonal orbit of C minor, Brahms’s music impresses as disembodied and phantom-like, suspended in an ethereal world inhabited, perhaps, by the ghostly images of Ingres’s celebrated painting Dream of Ossian (1813), where the bard leans over his mute harp, as Fingal and other Celtic warriors congregate behind him.

Ex. 10 Brahms, Gesang aus Fingal, op. 17 no. 4, 1–8

Brahms’s Gesang aus Fingal is admittedly an outlier in the composer’s oeuvre – one would well expect to find here concessions to an ‘antiquarian’ musical style, in a way similar to what Margaret Notley has recently described as ‘the sense of estrangement from tonal norms’ that obtains in Brahms’s Gesang der Parzen, op. 89. Drawing its text from Goethe’s play Iphigenie auf Tauris, that work indulges in modal passages in A-Phrygian and D-Aeolian to create ‘the effect of an ancient processional’.Footnote 37 But how else might we account for similar modal incursions in Brahms’s other works? In addition to the category of folk music (or deliberate simulations of folk music), Biamonte identifies two further categories to help explain the composer’s modal indulgences. One was his association of modes with sixteenth-century sacred choral music, a not surprising linkage that was likely promoted by the later nineteenth-century Palestrina revival. Numerous examples from Brahms’s motets and other choral works resist conventional tonal analysis, such as ‘Aus dem 51. Psalm’, op. 29 no. 2 (1865), ‘O bone Jesu’, op. 37 no. 1 (by 1859), and ‘O Heiland, reiß die Himmel auf’, op. 74 no. 2 (1863–64), but seem concerned rather with reviving the modal sound world of the late Renaissance.Footnote 38 Then there is the extraordinary, though still relatively little-known, case of the Missa canonica, which Brahms conceived in 1856 as a setting of the Latin Ordinary of the Mass for five parts.Footnote 39 A Kyrie in G minor, composed concurrently in a baroque style with continuo, was meant as ‘simply an exercise’,Footnote 40 not as part of the envisioned Mass. But the other movements that Brahms finished, including a Credo, Sanctus, Benedictus, and Agnus Dei (only the last three have survived, in a copy prepared by Brahms’s friend Julius Otto Grimm), were designed in a neo-Renaissance style that employed modal passages, as well as techniques such as mirror inversion, and what Clara Schumann (in the case of the Credo) described as a ‘labyrinth of canons’.Footnote 41 It is significant, too, that in June 1856, around the time Brahms was engaged with the Ordinary, he began copying the six-part Pope Marcellus Mass of Palestrina, who had been viewed historically, of course, as the saviour of church polyphony, and the fons et origo of Fux’s summa of modal counterpoint, the Gradus ad Parnassum.

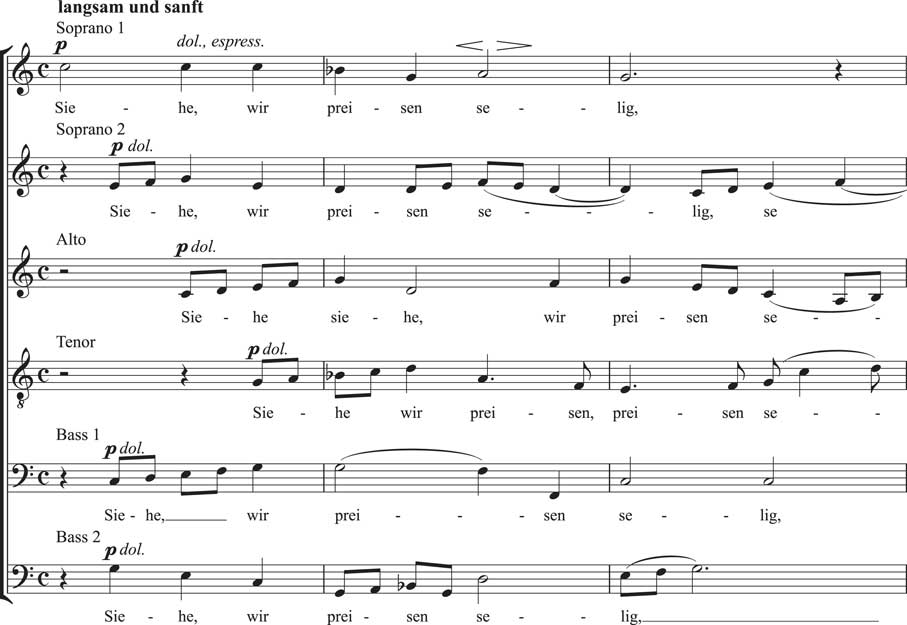

The extended conclusion of Brahms’s Agnus Dei, the Dona nobis pacem, unfolds initially in a luminous display of C-Mixolydian, with the ‘soft’, lowered seventh degree, B♭ tending to be privileged over the ‘hard’, raised leading-tone B![]() (Ex. 11a, bars 1–4). Brahms never finished his Missa canonica, but he later revived and revised two of its portions in his six-voiced motet from 1879, ‘Warum ist das Licht gegeben dem Mühseligen?’, op. 74 no. 1. Its second movement, ‘Lasset uns unser Herz’ (Jeremiah 3:41) is a reworking of strands in imitative counterpoint from the Benedictus, while the third movement, ‘Siehe, wir preisen selig’ (James 5:11), is adapted and extensively revised from the Dona nobis pacem. In this case, Brahms made the texture denser by accommodating a sixth voice. He modernized the archaic

(Ex. 11a, bars 1–4). Brahms never finished his Missa canonica, but he later revived and revised two of its portions in his six-voiced motet from 1879, ‘Warum ist das Licht gegeben dem Mühseligen?’, op. 74 no. 1. Its second movement, ‘Lasset uns unser Herz’ (Jeremiah 3:41) is a reworking of strands in imitative counterpoint from the Benedictus, while the third movement, ‘Siehe, wir preisen selig’ (James 5:11), is adapted and extensively revised from the Dona nobis pacem. In this case, Brahms made the texture denser by accommodating a sixth voice. He modernized the archaic ![]() metre of the original to Common time, but kept intact the Mixolydian references, as if to ally his music with an idealized vision of Palestrinian polyphony, and to recapture its scrupulous control of dissonance treatment (Ex. 11b, bars 1–3).

metre of the original to Common time, but kept intact the Mixolydian references, as if to ally his music with an idealized vision of Palestrinian polyphony, and to recapture its scrupulous control of dissonance treatment (Ex. 11b, bars 1–3).

Ex. 11a Brahms, Missa canonica, ‘Dona nobis pacem’, 1–4

Ex. 11b Brahms, Motet, op. 74 no. 1, 1–3

If not applying modes in sacred works hearkening back to the Renaissance or in other works inspired by folk music, Brahms also occasionally turned to modality in order to oblige his historicist interests – Biamonte’s third category, which brings us once again back to the Clarinet Trio. Thus, in the first movement, the brief appearances of fauxbourdon-like passages work in partnership with the austere treatments of the Aeolian mode. That is to say, the evocation of a distant musical past, as signalled by the prominence of the Aeolian mode, is supported by the emergence of periodic, fauxbourdon-like harmonies that seem to belong to the fifteenth rather than nineteenth century. The effect is not unlike Mahler’s solemn, unworldly imitation of medieval organum in ‘Das himmlische Leben’, the strophic song that concludes the Fourth Symphony (1900; the song actually dates back to 1892), where stark harmonies moving in parallel motion are interspersed throughout the narrative of the child’s vision of heaven. Mahler’s conceit impresses as if the twelfth century had somehow intruded into the early twentieth.

If we take a broader view, we can see that Brahms’s use of modality was part of a large-scale musical agendum – to relate his music in different ways to the past, whether it was the relatively recent romanticism of Robert Schumann or Mendelssohn, or the increasingly distant styles of eighteenth-century classicism, the Baroque or the Renaissance. The examples abound and are familiar enough – for instance, the spirit of the finale of Schumann’s Fantasy op. 16 hovers over the Poco sostenuto of the finale of the Piano Quintet, eighteenth-century classicism is celebrated in the Serenade in D major and Haydn Variations, and the Baroque is invoked in the Handel Variations, and in the use of ostinato bass figures in various works, such as in the slow movement of the Horn Trio, the finale of the Haydn Variations, and, of course, the chaconne finale of the Fourth Symphony. Brahms’s turn to modality, then, whether in the works we have discussed or in the ‘remote’ Phrygian openings of the slow movement of the Fourth Symphony and first movement of the late Clarinet Sonata in F minor op. 120 no. 1, is further evidence of his historically oriented compositional outlook, and, more specifically, of his curiosity about the more distant musical past.

There remains one further issue to broach, and that is to extent to which Brahms’s embrace of modality affected the deepest structural layers of his music. Most of the examples we have presented remained, despite their modal inflections, tonal compositions for the composer’s contemporaries, and, indeed, they have been received as such by us. Thus, the third Violin Sonata op. 108 was (and is) understood to be a work in D minor, notwithstanding its alluring opening in D-Aeolian, and despite Brahms’s fascination, especially in the first movement, with tetrachords that seem to exhibit more an affinity to ancient modes than to major and minor scales. But the question remains: do these modal markers operate primarily on the surface of the music, or do they penetrate in some way into structural substrata? Are they just so many ‘special cases’, as Arnold Schoenberg concluded in his Harmonielehre, in essence ‘merely antiquarian reminiscences of the church modes, through whose use certain singular effects are created, as in Brahms’s music’?Footnote 42 As a final example, we might turn briefly to the Adagio of the String Quintet in G major op. 111 (1890), surely one of Brahms’s most singular creations, especially following, as it does, the radiantly tonal G-major sonorities of the first movement.

At first glance, the key signature of the Adagio suggests a movement in D minor that ultimately, by raising the minor third a semitone to F![]() , ends in D major. But a purely tonal reading is problematic, for the putative tonic is challenged from the outset, first by the use of half cadences that fail to assert the tonic convincingly (Ex. 12a, bars 1–8). In the first two bars, we do not know whether we are hearing a movement in D minor, or a movement in A major that dips into the minor form of its subdominant. Does the opening suggest i–V, with D minor as the tonic, or iv–I, with A major as the tonic? Then, in bar 3, Brahms further clouds our sense of tonal clarity by moving unexpectedly to C major, a gambit that seems to tip the music into a modal domain. C

, ends in D major. But a purely tonal reading is problematic, for the putative tonic is challenged from the outset, first by the use of half cadences that fail to assert the tonic convincingly (Ex. 12a, bars 1–8). In the first two bars, we do not know whether we are hearing a movement in D minor, or a movement in A major that dips into the minor form of its subdominant. Does the opening suggest i–V, with D minor as the tonic, or iv–I, with A major as the tonic? Then, in bar 3, Brahms further clouds our sense of tonal clarity by moving unexpectedly to C major, a gambit that seems to tip the music into a modal domain. C![]() impresses as the lowered seventh degree of D, and that, in turn, supports a modal perception of the opening as suggesting, perhaps, D-transposed Aeolian. If we take into account the preceding bass motion from D to A of bars 1–2, and the half cadence on a shimmering dominant tremolo in bar 8, there begins to emerge from a deeper layer of the voice leading an incomplete modal tetrachord, which we may sketch in the reduction of Ex. 12b as D–C–A, with the sixth scale degree, the B♭, omitted (it is briefly suggested, though, by the B-flat 6/3 harmony in bar 6; the B♭ is activated in the treble, following a 10–6 exchange between the outer voices).

impresses as the lowered seventh degree of D, and that, in turn, supports a modal perception of the opening as suggesting, perhaps, D-transposed Aeolian. If we take into account the preceding bass motion from D to A of bars 1–2, and the half cadence on a shimmering dominant tremolo in bar 8, there begins to emerge from a deeper layer of the voice leading an incomplete modal tetrachord, which we may sketch in the reduction of Ex. 12b as D–C–A, with the sixth scale degree, the B♭, omitted (it is briefly suggested, though, by the B-flat 6/3 harmony in bar 6; the B♭ is activated in the treble, following a 10–6 exchange between the outer voices).

Ex. 12a Brahms, String Quintet no. 2, op. 111, II, 1–8

Ex. 12b Brahms, String Quintet no. 2, op. 111, II, 1–8 (Reduction)

The descending fourth, D–A, which thus plays out over the course of several measures, suggests a prototypical tetrachord of an as yet undetermined mode, and, further, assumes a recurring role throughout the movement, in tension with a tonal analytical reading. First, in bars 15–24 Brahms repeats and slightly extends the opening period on the ‘tonic’, so that it now fills ten bars instead of eight. Once again the essential bass motion traces a descent from D to the lowered seventh C, before reaching another half cadence on the dominant A. Then, in bars 33–40, Brahms presents a statement of the opening period on the subdominant G minor – in this case, the implied tetrachord descends from G to F and D, with the missing sixth degree, E♭, hinted at in bar 38. Placing these tetrachords together yields a long-term, descending Phrygian mode on D (D–C–B♭–A–G–F–E♭–D), composed out over the span of 40 bars, reinforcing the impression that in this case, at least, Brahms’s modal strategy suggests more than a mere ‘antiquarian reminiscence’, and, indeed, affects the middleground structure of the movement. Be that as it may, there are two more iterations of the opening period to consider. First, beginning in bar 52, Brahms actually turns to a tonal reading of the passage in the ‘tonic’ D major, though this version is soon enough interrupted and summarily rejected by a tumultuous encroachment of D minor, leading to the dissonant climax of the movement. And finally, in the concluding coda of bars 67–80, Brahms comes full circle and returns to the opening measures, now retouched to set up the unexpected ending in D major. But as the F![]() is introduced into the harmonies of the concluding bars, we hear clearly for the first time the complete and stepwise descending tetrachord D–C–B♭–A in the first violin, validating, as it were, our modal reading of the movement. Set against a rising tetrachord in the second viola, D–E–F

is introduced into the harmonies of the concluding bars, we hear clearly for the first time the complete and stepwise descending tetrachord D–C–B♭–A in the first violin, validating, as it were, our modal reading of the movement. Set against a rising tetrachord in the second viola, D–E–F![]() –G, we end, in effect, with a hybrid major-minor scale, with tetrachords suggesting Mixolydian and Phrygian hues (Ex. 12c, bars 75–80). The movement is as modally ambiguous as it is tonally enervated, with plagal cadences supplanting the traditional function of the dominant, and, further, reinforcing the modal tetrachordal framework that supports the movement and enhances its appeal as it suggests a musical ‘other’.

–G, we end, in effect, with a hybrid major-minor scale, with tetrachords suggesting Mixolydian and Phrygian hues (Ex. 12c, bars 75–80). The movement is as modally ambiguous as it is tonally enervated, with plagal cadences supplanting the traditional function of the dominant, and, further, reinforcing the modal tetrachordal framework that supports the movement and enhances its appeal as it suggests a musical ‘other’.

Ex. 12c Brahms, String Quintet no. 2, op. 111, II, 75–80

This condensed sketch of the Adagio (for a summary of the essential bass line of the entire movement see Ex. 12d) in no way does full justice to its many subtleties, which effortlessly skirt the borders between tonality and modality. Still, our sketch does suggest that in the end modality, or rather a synthesis of modality and tonality, came to represent for the aging Brahms a viable alternative to an attenuated tonal system. Further, the sketch suggests that Brahms’s conflicting modes of historical thought offer a viable way forward toward understanding his later music, in which the present is filtered through a distant past. Within a few years, this process would resonate with one of Brahms’s great admirers, Anton von Webern, who on occasion also found his own paradoxical path to modernism by re-experiencing the past, including the distant past. And so it was that Webern, who produced a doctoral dissertation on the early sixteenth-century Choralis Constantinus of Heinrich Isaac,Footnote 43 composed in 1928 a historicist work par excellence, his Sinfonie op. 21. Employing four twelve-tone rows, in the first movement Webern unfolded a consummate double mirror canon vaguely but eerily reminiscent of Franco-Flemish polyphony, and yet simultaneously set within a compact binary sonata form recalling early classical models of the mid-eighteenth century, all the while exploring with unabashed modernist rigour a crystalline, pointillistic style of dodecaphony. As Webern’s musicological lectures, Der Weg zur neuen Musik, reveal,Footnote 44 he, like Brahms, was haunted by music history. Perhaps, then, Webern’s clashing modes of historical thought were the logical next step after those of Brahms, who clearly found meaning near the end of the nineteenth century in the ancient modes of the distant past.

Ex. 12d Brahms, String Quintet no. 2, op. 111, II, (Summary)