1. Introduction

At the gift shop just inside the entrance to the John Rylands Library, you can purchase a postcard featuring a handsome colour photograph of P.Ryl. iii.457 (better known to most as P52), probably the most famous single manuscript in the Rylands collection. The card actually features two photographs, one showing the front of this papyrus scrap and one showing the back, both at a degree of magnification (the actual remains of papyrus are quite small, just 8.9 cm high and 5.8 cm wide). The caption on the reverse of the card is succinct: ‘Papyri [sic] fragment of St John's Gospel, written in Greek and dated to 125 ad. This is the earliest surviving piece of the New Testament.’ One finds similar descriptions of the manuscript in more scholarly literature as well. In a catalogue of the biblical manuscripts in the Rylands Library, J. K. Elliott has described P52 as dating ‘from about 125 ad’, making it ‘the oldest copy of a New Testament writing’ and ‘the oldest Christian writing extant’.Footnote 1 The curious recipient of our postcard or reader of this catalogue might wonder how, exactly, this date in or about the year 125 came to be established. Turning to the original publication of the gospel fragment, we find that its editor, Colin H. Roberts, assigned a date to the fragment by means of palaeography, the analysis of handwriting.Footnote 2 Yet, could palaeographic analysis yield such a precise result? In fact, Roberts himself did not assign the fragment a date in or around any specific year. Instead he regularly described the Rylands gospel fragment as dating from ‘the first half of the second century’. The year 125 seems to serve for many as a shorthand for Roberts’ somewhat more sensible half-century range. But is even fifty years too narrow of a range for such a small sample of writing? Might styles of handwriting like that of P52 have persisted even longer? How compelling were the similarities with the comparative manuscripts used by Roberts to establish this range of dates?

Evaluating Roberts’ assessment can be somewhat challenging. Although photographs of the manuscripts he used for comparison exist, they are scattered in different publications, some of which are quite difficult to find. In a 2005 article, I attempted to improve this situation by gathering and presenting images of all the manuscripts that had figured in the palaeographic discussion of P52 and introducing further comparanda that broadened the spectrum of possible palaeographic dates for P52 beyond the middle of the second century.Footnote 3 The main goal of that earlier article was to encourage more caution about the use of papyrological evidence in arguments concerning the date of the composition of John's gospel. The article was fairly exhaustive in dealing with published scholarship on the dating of the fragment, but fifteen years later there is perhaps a bit more to say. The present contribution introduces new details about the acquisition and publication of P52, engages post-2005 scholarship on the date of the fragment and reaffirms that the range of possible palaeographic dates for P52 extends into the third century.

2. New Information about the Acquisition of P52

It is well known that the source of P52 was the antiquities market. At the time of its publication, P52 was said to be part of a lot of papyri acquired for the Rylands collection in Egypt by Bernard P. Grenfell in 1920.Footnote 4 Access to archival materials in the Rylands Library and the British Library now permits me to say more about this purchase than I was able to in 2005. The core of the Rylands papyrus collection had been established in 1901 with a purchase of a pre-existing collection by Enriqueta Rylands.Footnote 5 Subsequent purchases over the next two decades augmented the collection.Footnote 6 Grenfell's purchases in 1920 on behalf of the Rylands Library are reasonably well documented thanks to a series of letters by Grenfell himself and the diary of Francis Kelsey, who had joined Grenfell on this purchasing expedition.Footnote 7 These sources indicate that Grenfell selected two separate lots of papyri for the Rylands Library in 1920, one prior to 24 February consisting of forty papyri and costing £55 and one between late February and 26 March consisting of twenty-seven papyri at a cost of £50.Footnote 8 In a letter of 1 May 1920 to Henry Guppy (the long-time Rylands librarian), Grenfell outlined the contents of both of these purchases. The first purchase is described as follows:

The lot which you have bought for £55 comprises 3 literary fragments of the Ptolemaic period (two of these, both historical, are of exceptional interest), 10 literary fragments of the Roman or Byzantine periods, 3 Latin literary papyri (Virgil with a Greek translation and Cicero, De divinatione), 19 Ptolemaic documents, 2 of Augustus’ reign, 1 Latin doc. and 1 important early Christian letter. They were certainly very cheap at the price, being selected from a very large collection, of which they were the cream.

Grenfell described the second purchase in a similar level of detail:

[A]part from the group of 40 papyri for which you sent me £55, I have selected for you a group of 27 papyri which I offer you for £50. These comprise 7 Ptolemaic papyri (one large), 6 papyri of Augustus’ reign (rare), 4 theological pieces, 7 Latin papyri, 2 Roman documents (non-literary), and 1 literary fragment.Footnote 9

From these descriptions, it is clear that Grenfell knew what pieces he was buying. He was not acquiring batches of unsorted papyri, but rather he ‘cherry-picked’ pieces out of larger groups of papyri that were for sale.Footnote 10 It is somewhat curious, then, that Grenfell makes no mention of a fragment of John's Gospel, much less a second-century fragment of the Gospel, despite having chosen these pieces individually.Footnote 11 It seems difficult to escape the conclusion that Grenfell recognised P52 as a fragmentary leaf of John's Gospel, but did not think it especially ancient or otherwise significant enough to warrant special mention. It is likely that he simply classified it as one of the four ‘theological pieces’ of the second purchase (further evidence pointing in this direction will be discussed below).Footnote 12 In subsequent months, Grenfell continued to write to Guppy about the papyri, which Grenfell had kept with him at Oxford. The final letters from Grenfell in the John Rylands archive date to July 1920.Footnote 13 At roughly that time, Grenfell was forced to retire permanently from academic work due to his failing health.Footnote 14 After Grenfell's death in May 1926, the collection of papyri Grenfell had designated for the Rylands collection was transferred to the custody of Grenfell's long-time co-worker, Arthur S. Hunt, who had edited the first two volumes of the Rylands Greek papyri in 1911 and 1915.Footnote 15 It seems that Hunt, too, had examined at least a portion of Grenfell's 1920 purchases for the Rylands Library in preparation for the third volume of the Rylands Greek papyri in 1933.Footnote 16 Hunt, however, was unable to produce this third volume, and before his death in June of 1934, he passed responsibility for the publication of the remainder of the Rylands collection to a 25-year-old Colin H. Roberts.Footnote 17

3. Roberts’ Publication of P52

The fragment of John seems to have first come to Roberts’ attention in the summer of 1935. In a letter to Guppy dated 19 July 1935, Roberts wrote as follows:

You may remember that not long before his death Prof. Hunt asked me if I would take over, with your consent, the publication of the remaining Rylands papyri. I agreed at the time, but had to withdraw last year as his death made my future plans rather uncertain. This summer, however, I have had some slow time on my hands and the last two months I have been engaged in making first transcripts of all the unpublished Rylands papyri – this is now practically finished. Hunt remarked to me once that the collection was small and not of great importance: but I think he must have forgotten the last group acquired for the Library by Grenfell … there are a large number of literary fragments, both Greek and Latin – these include Callimachus, Virgil, Menander (probably), some unknown historical writings and several medical texts: there is also a very interesting Christian letter attacking the Manichees. Probably the gem of the collection is a very small fragment which I have identified as being part of St. John's gospel: in all probability it was written early in the 2nd century (Dr. Bell of the British Museum is of the same opinion) and is thus by about 100 years the earliest fragment of the N.T.Footnote 18

Roberts was apparently unaware that Grenfell had already made rough identifications of the pieces and informed Guppy of the contents of the papyri fifteen years earlier. Nevertheless, Guppy was highly impressed with Roberts’ dating of the fragment, and he and Roberts quickly made plans for an expedited publication of the papyrus. A short time later, Roberts mailed the papyrus from Oxford to Manchester to be photographed.Footnote 19 Pictures of the papyrus were duly sent to a number of papyrologists to solicit opinions, and Guppy arranged for a pamphlet to be published by Manchester University Press in November 1935. The publication received a great deal of media attention throughout Europe and North America.Footnote 20 The excitement, of course, had to do with the date assigned to it by Roberts. With no archaeological context to help, Roberts had to rely on palaeography to arrive at a date. After discussing similarities and differences between the Rylands fragment and seven other papyri and taking into consideration the opinions of other papyrologists, Roberts arrived at a date in the ‘first half of the second century’.Footnote 21

Most reports concerning the papyrus in both scholarly and popular publications simply repeated Roberts’ statement of the date word for word.Footnote 22 Almost immediately, however, some New Testament scholars pushed backwards the date suggested by Roberts and made it more specific. Consider the headline of a popular article by Adolf Deissmann, then professor of theology in Berlin: ‘Ein Evangelienblatt aus den Tagen Hadrians’.Footnote 23 Deissmann offered no actual evidence to justify this revised date, but it nevertheless slipped into some scholarly discussions.Footnote 24 On the other hand, there were occasional voices of caution, such as the New Testament textual critic Ernest Colwell at the University of Chicago. After describing Roberts’ assignment of the papyrus to the first half of the second century, Colwell responded that

it is exactly in regard to date that a study of literary papyrus hands encounters difficulties. The scarcity of dated material for comparison and the stereotyped nature of the script make anything more than approximate dating very difficult. The wise reader will, therefore, hesitate to base any important argument on the exact decade in which this papyrus was written; he will even hesitate to close the door on the possibility that it may be later than ad 150.Footnote 25

But Colwell was in the minority. The trend of pushing Roberts’ date earlier and making it narrower persisted through the twentieth century.Footnote 26 By the beginning of the present century, some handbooks were describing the Rylands fragment as dating to ‘ad 100, plus or minus a few years’ or even, incredibly, ‘around the year 80’.Footnote 27

Such opinions are generally (correctly) dismissed as fringe voices, but even Kurt and Barbara Aland of the Institut für neutestamentliche Textforschung, the epicentre of mainstream New Testament textual criticism, have written that

the critical significance of P52… lies in the date of ‘about 125’ assigned to it by the leading papyrologists. Although ‘about 125’ allows for a leeway of about twenty-five years on either side, the consensus has come in recent years to regard 125 as representing the later limit, so that P52 must have been copied very soon after the Gospel of John was itself written in the early 90s ad.Footnote 28

I understand this desire to give more precise dates to manuscripts. Phrases like ‘around the year 80’ or ‘about ad 125’ are easily digestible. Yet such precision masks the difficulty and uncertain nature of the process of palaeographic dating.Footnote 29 The proposals for earlier and more narrow dating of the Rylands gospel have almost never been accompanied by actual palaeographic evidence to justify the proposals. The one such study that did introduce new comparanda prior to 2005 appealed only to another small papyrus fragment that had itself been dated solely by means of palaeography.Footnote 30

My 2005 article attempted to review all the evidence, and to collect and print together images of all the manuscripts that had been featured in the discussions about palaeography of the Rylands fragment.Footnote 31 I stressed the importance of using only more objectively datable manuscripts for comparison and pointed out that in 1977, Eric G. Turner had suggested that a document as late as 184 ce provided an illuminating parallel for the hand of the Rylands fragment (I will come back to Turner's evidence in due course).Footnote 32 I also stressed that when it comes to literary Greek writing of the Roman era, palaeographic date ranges limited to only twenty-five or fifty years were not realistic, which is a fairly obvious point when one actually pauses to ponder some basic questions about handwriting. How quickly do styles of handwriting change? Do they always change at a uniform pace? Are some styles more persistent than others? What is the normal productive working life of a copyist? Are styles passed from teachers to students across multiple generations? Does every graphic change in a given style of writing necessarily correlate to a temporal change? What about the competency or personal inclinations of individual copyists? What about the tastes of those who commission copyists? These questions should be enough to cast doubt on overly precise dates assigned only on the basis of palaeography. In any event, the result of my study was a broadening of the spectrum of possible dates of P52 on the basis of palaeography to include dates as late as the early third century.

3. Recent Scholarship on P52

Since 2005, there has been some further discussion about the date of the Rylands fragment. In his 2009 book, Roger Bagnall questioned the early dates assigned to several Christian papyri on the basis of palaeography and argued that, statistically, we should expect that hardly any second-century Christian material should be among the surviving papyri. With specific regard to P52, Bagnall suggested that my argument had ‘undermine[d] confidence in an early date, even if [it did] not fully establish one in the late second or early third century’.Footnote 33

At the 2010 papyrology congress in Geneva, Stanley Porter gave a paper that was critical of both Bagnall's work and my own.Footnote 34 Porter's goal was to use Christian literary papyri to reconstruct the history of early Christianity in the second century. Because Bagnall contended that there may be precious few such papyri actually datable to the second century, Porter attempted to reaffirm the second-century dating of certain Christian literary papyri. The bulk of Porter's discussion focused on two manuscripts, the Rylands papyrus of John and the fragmentary leaves of an unknown gospel, the so-called Egerton papyrus, which were published just a few months before P52, and which featured prominently in Roberts’ palaeographic discussion.Footnote 35 In fact, almost the exact same cluster of manuscripts was used to palaeographically date both of these papyri.Footnote 36 For that reason, I had argued in 2005 that the Egerton papyrus had no independent value for establishing a date for the Rylands fragment and that our focus should instead be on securely dated manuscripts as comparanda. Porter, however, objected to the use of dated documents written in book-like hands for the purpose of assigning dates to undated literary papyri, claiming that ‘there are characteristics of documentary hands, such as ligature and cursive forms, that distract from comparison’. Porter's alternative proposal was ‘to expand the analytical perspective for using undated manuscripts’ to establish dates for other undated manuscripts.Footnote 37

Porter proceeded to compare the Egerton gospel and P52 to each other, then to a series of other (undated) Christian papyri, and finally to the tables of alphabets from the 1912 handbook of E. M. Thompson and the 1987 handbook of Turner and Parsons, alphabets that are mostly drawn from undated manuscripts.Footnote 38 From these exercises, Porter concluded not only that P52 and the Egerton gospel were ‘firmly placed within the second century’, but that they were to be dated ‘somewhere in the middle second century, perhaps toward the early part of it’.Footnote 39 And this conclusion is said to establish a framework for dating other papyri.

It is difficult to know how to engage productively with an argument like this, since none of the manuscripts in the discussion has a secure date. In the past, I have referred to a statement of Peter Parsons, and it seems worth repeating here: assigning a palaeographic date to a literary papyrus of unknown date by using another palaeographically dated papyrus results in ‘only jelly propped up with jelly’.Footnote 40 It seems to me that Porter's attempt to use two undated pieces simultaneously to date each other may be regarded as exceedingly gelatinous.

Nevertheless, Porter's piece does raise a useful point for reflection. It serves as an excellent illustration of how misinformation can easily creep into palaeographic discussions that are not grounded in reference to securely datable comparanda. Because he has minimised the importance of dated documents written in book-like hands, Porter's argument revolves less around appeals to evidence and more around appeals to the authorities who have assigned dates to undated literary manuscripts. Especially instructive in this case are his appeals to the authority of Wilhelm Schubart regarding the Egerton gospel. On multiple occasions, Porter asserts that although the original editors of the Egerton gospel placed it in the middle of the second century, the great German papyrologist believed it was earlier. So, for example, Porter writes, ‘Whereas Bell and Skeat proposed [a date of] around ad 150 for P.Egerton 2, Schubart thought it dated to before ad 150.’Footnote 41 Interestingly, Porter provides neither specific quotations nor bibliographic references to substantiate these claims. Let us try to see what Schubart actually said.

When Harold Bell (together with Theodore Skeat) produced the official publication of the fragments in March 1935, the editors used a variety of expressions for the date of the papyrus. Most concisely, the date is described at the outset simply as ‘Middle of second century’.

Bell and Skeat immediately qualified that evaluation by stating that ‘the date assigned to it above is highly probable and is likely to err, if at all, on the side of caution, for there are features in the hand which might suggest a period yet earlier in the century’.Footnote 42 Finally, the editors claimed that it was ‘extremely improbable’ that the papyrus ‘can be dated later than the middle of the second century’.Footnote 43 Schubart's authority was invoked at the conclusion of the discussion of the date: ‘It may be added in conclusion that Professor Schubart, to whom a photograph was sent and whose authority on such a matter none will question, pronounced the date here assigned “as good as certain”, that is in the degree to which palaeographical datings can ever be certain; and he remarked that some features of the hand might suggest an even earlier date.’Footnote 44 So, we can see here the probable basis of Porter's claim (though, the point of Bell's citation seems to be that Schubart agreed rather than disagreed with the editors’ proposed date). Yet, in the preface to Bell and Skeat's edition, outside the discussion of the date, Bell had this to say about Schubart: ‘Prof. Schubart has examined photographs … and given us an opinion as to dating which his reputation as a palaeographer makes specially valuable. It should be added that he emphasizes the uncertainty of the palaeographical factor, which in the present case is the sole evidence of date.’Footnote 45 Thus, instead of being ‘as good as certain’, here Schubart is said to have stressed the uncertainty of palaeographical dating. That is to say, even in these citations from Bell, there is some ambivalence attributed to Schubart. One wonders what Schubart actually communicated to Bell.

Among Bell's papers in the British Library, there is a letter from Schubart dated 11 February 1935, after Bell's initial announcement of the Egerton gospel in the Times but before his official publication of the manuscript with Skeat in March of 1935.Footnote 46 In the letter, Schubart mentioned that he had read the Times article and received a photograph of the manuscript from Roberts. Schubart responded to Bell's proposed date with the following:

The manuscript is without question old, only I do not know whether one may place it with certainty before ad 150. I have found similar style in dated documents and letters (only these can further assist) both in the time of Hadrian and in that of Marcus and Commodus. I would therefore set the time span somewhat wider. To date such a literary hand is simply one of the most difficult tasks.Footnote 47

It is fascinating that the overall thrust of Schubart's message is the issue of the uncertainty of palaeographic dating and the encouragement to allow for a wider range of dates.Footnote 48 Bell seems to have latched on to Schubart's reference to similar hands in dated documents of the period of Hadrian, without seeing a need to mention that Schubart also allowed for later dates as well.Footnote 49 But the points that Schubart emphasises are the uncertainty of palaeographic dating, the need for a wider range of possible dates, and securely dated documents as the most ideal comparanda for the purposes of trying to establish a date. These emphases stand in considerable tension with Porter's approach.

I have made this digression on Schubart and the Egerton papyrus because it illustrates an important point. While I have come to believe that it is unhelpful even to refer to non-securely dated manuscripts when trying to assign a palaeographic date to an undated manuscript, I understand that others might be loath to give up this practice due to the relative paucity of dated or datable examples of literary Greek writing of the Roman era. But if we are going to continue to have these appeals to undated manuscripts, which are essentially appeals to the judgements and authority of earlier scholars, let us at least appeal to authorities as correctly as we can. The whisper-down-the-lane effect from Schubart to Bell and Skeat to Porter twists Schubart's original point 180 degrees. Far from advancing the discussion, these kinds of arguments simply muddy the waters.Footnote 50

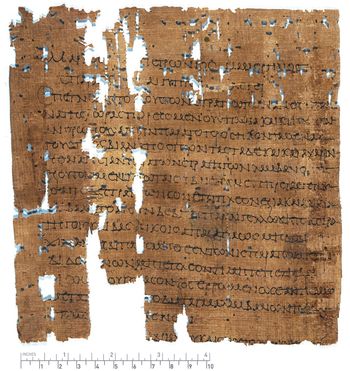

Fortunately, there have also been more fruitful treatments of the Rylands gospel fragment. In a 2008 study, Edoardo Crisci argued that the handwriting of P52 could be usefully compared to a particular type of bureaucratic or chancery writing found in some documents.Footnote 51 As examples of this type of writing, Crisci cited PSI v.446, a decree of Marcus Petronius Mamertinus, who was prefect over Egypt during the years 133–7 ce, and P.Flor. i.1, a record of a loan written in 153 ce, Figures 1–3 illustrate these pieces along with P52.Footnote 52

Figure 1. P.Ryl. iii.457, recto and verso. Reproduced by courtesy of the Librarian and Director, The John Rylands University Library, The University of Manchester. Copyright of the University of Manchester Library.

Figure 2. PSI v.446, front (a decree of a prefect dating to 133–7 ce). Image appears courtesy of the the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence. By permission of the Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali e per il turismo. Reproduction prohibited.

Figure 3. P.Flor. i.1 (a record of a loan written in 153 ce). Image appears courtesy of the the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence. By permission of the Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali e per il turismo. Reproduction prohibited.

Having placed P52 within this general graphic type, Crisci then assigned the Rylands fragment to the first quarter of the second century.Footnote 53 I am more sympathetic to this kind of approach, grounded as it is with reference to actual datable manuscripts, but I strongly object to the implausibly narrow range of dates allowed by Crisci. And indeed, other studies provide reason to doubt the cogency of Crisci's conclusion in this case. In a 2012 study, Pasquale Orsini and Willy Clarysse applied the same methodology as Crisci. In fact, they used the exact same comparative manuscripts, PSI v.446 and P.Flor. i.1, to assign a different date to P52!Footnote 54 Orsini and Clarysse concluded that P52 should be assigned somewhere between 125 and 175, or as they put it at the conclusion of their article, P52 should probably be assigned to the second half of the second century.Footnote 55

The arguments of both Crisci and of Orsini and Clarysse rely on studies of Roman chancery writing by the noted Italian palaeographer, Guglielmo Cavallo. What one finds when one consults these studies is that the dated examples of this type or style of writing are said to extend from the early second century well into the first half of the third century.Footnote 56 Crisci did not provide specific arguments explaining why he placed P52 in very narrow limits at the earliest end of this broad spectrum. To make their case for placing the copying of P52 sometime between the years 125 and 175, Orsini and Clarysse did make specific reference to a piece with a secure date, P.Fay. 87, a receipt from the year 156 ce (see Figure 4). The writing of this piece is in rounded capitals with occasional ligatures. It employs prominent serifs or blobs at the ends of strokes, much more distinct than those of PSI v.446 and P.Flor. i.1. The hand is somewhat heavy (vertical strokes are sometimes over 0.2 cm wide). It is basically bilinear, although iota, rho and phi regularly descend below the lower notional line. Its lettering is generally upright although sometimes displaying an incline to the right (in contrast to P52, which inclines slightly to the left). Some letters have similar shapes to those found in P52 (alpha, epsilon and occasionally upsilon), while others are quite distinct (such as kappa, pi, rho and omega, see Figure 5).Footnote 57

Figure 4. P.Fay. 87 (a receipt of 156 ce). British Library, Papyrus 825. © British Library Board.

Figure 5. Individual letters of P.Fay. 87 (British Library, Papyrus 825) and those of P52 (P.Ryl. iii.457). British Library, Papyrus 825, © British Library Board, and P.Ryl. iii.457, copyright of the University of Manchester Library.

What is noteworthy about their choice of this particular comparandum is that the writing of P.Fay. 87 has been classified as somewhat atypical of the mid-second century. This is the description of the piece given by the original editors, Grenfell and Hunt: ‘The papyrus is written in a remarkable hand, which presents at first sight an almost Byzantine appearance, mainly due to the thickening of the extremities of the rather large and heavy semiuncial letters.’Footnote 58 If Orsini and Clarysse are correct in detecting an affinity between the script of P52 and that of P.Fay. 87, this might explain why Grenfell did not single out the Rylands gospel fragment in his letters to Guppy: Grenfell may well have judged the handwriting of P52 to have a similar ‘Byzantine appearance’ and thus to be worth buying insomuch as it was a ‘theological’ fragment, but not such a remarkable or early piece as to warrant special mention in his correspondence with Guppy. This is, of course, only speculation, but such a scenario would help to account for Grenfell's treatment of (or rather, his lack of interest in) the papyrus.

In any event, it is curious that neither Crisci nor Clarysse and Orsini mention any of the later proposed palaeographic comparanda for P52 (either to confirm or refute them). And this brings me back to Eric Turner. While working at the University of Western Australia in 2013, I came across Turner's annotated copy of Roberts’ original 1935 edition of P52.Footnote 59 Turner's marginal notes in the book seem to have been written in the 1970s.Footnote 60 These notes are sparse but telling. Next to some of Roberts’ suggested parallels, including the Egerton gospel, Turner has tersely written ‘Not dated.’ Elsewhere in the margins, he gives his own verdict on the dating: ‘I should tend to put it later, though still c. ii.’ At various other points in the margins, Turner adds dated manuscripts for comparison. These examples span the course of the second century. In chronological order, they are: P.Lond. iii.904, a collection of letters from 104 ce; P.Oxy. xlii.3016, judicial proceedings from the year 148 ce; P.Hamb. 39, a roll of receipts copied in 179 ce;Footnote 61 and P.Amh. ii.78, a petition from 184 ce. These pieces are illustrated in Figures 6–9.

Figure 6. P.Lond. iii.904 (a collection of letters from 104 ce). British Library, Papyrus 904, © British Library Board.

Figure 7. P.Oxy. xlii.3016 (judicial proceedings from the year 148 ce). Image courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society and the University of Oxford Imaging Papyri Project.

Figure 8. P.Hamb. 39, column 16 (receipts written in 179 ce). P.Hamb. graec. 184.H, Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek, Hamburg.

Figure 9. P.Amh. ii.78 (a petition from the year 184 ce). Image courtesy of The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Amh. Gr. Pap. 78. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1912.

It was P.Amh. ii.78, the latest of comparanda, that Turner chose to highlight in his discussion of P52 in The Typology of the Early Codex in 1977. It is not difficult to see why. The writing of P.Amh. ii.78 does contain some striking cursive features not present in the extant portions of P52 – such as the upsilon–sigma combination (line 12), and the epsilon–iota combination (line 8) – but it also displays a number of features very similar to what we find in the writing of P52. As Turner wrote in 1977, P.Amh. ii.78 ‘shows a hand with similarities in its overall uprightness (or even slight lean to the left), roundness and scale, and in the forms of particular letters (the two forms of α, the ε, π, ι in particular). But the letters are crushed more closely together and not so even in size, as would in any case be expected in a document.’Footnote 62 Indeed, when we compare sequences of identical letters, the similarities are evident (see Figure 10).

Figure 10. Individual letters of P.Amh. ii.78 compared with those of P52 (P.Ryl. iii.457). Amh. Gr. Pap. 78, courtesy of The Morgan Library & Museum, and P.Ryl. iii.457, copyright of The University of Manchester Library.

And in fact, such similarities continue to appear even in samples of handwriting securely dated to periods at least as late as the third century. P.Oxy. li.3614 contains extracts from a judgement of Septimius Severus issued at Alexandria in the year 200 (see Figure 11). The papyrus was thus copied some undetermined time after that.Footnote 63 I have singled out this papyrus before for its similarities to P52, but I do not think that these similarities have been fully appreciated. For this reason I provide further illustration here. P.Oxy. li.3614 was clearly not written with as much care as P52, but, again, when we look closely at individual letter forms and the relative positions of strings of letters, the similarities are readily apparent (see Figure 12). At the level of individual letters, quite similar forms of the alpha are present in both pieces (and the alpha occasionally rises above the upper notional line in both pieces). One finds in both pieces examples of the taller and shorter iota with comparable hook-like serifs. The omega is written in similar fashion with rounded tips. The pi and eta with a marked serif at the bottom of the right vertical stroke is common to both pieces. When strings of letters are examined side by side, we find comparable horizontal and vertical spacing. In Figure 12, the alpha–upsilon–tau sequence is illustrated. These parallels are as close as any comparandum in the current discussion of the palaeography of P52.

Figure 11: P.Oxy. li.3614 (extracts from a judgement copied after 200 ce). Image courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society and the University of Oxford Imaging Papyri Project.

Figure 12. Individual Letters of P.Oxy. li.3614 compared with those of P52 (P.Ryl. iii.457). P.Oxy. li.3614, courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society and the University of Oxford Imaging Papyri Project and P.Ryl. iii.457, copyright of The University of Manchester Library.

Yet, I must again emphasise that this kind of graphic proximity does not definitively rule out the possibility that P52 was copied sometime in the first half of the second century. Rather, it broadens the range of possible palaeographic dates. It is thus imprudent to restrict the date of P52 to the first half of the second century, as is commonly done in current scholarship.Footnote 64 As we have seen, reasonably close palaeographic parallels may be found among manuscripts dated to the second half of the second century, and even into the third century.Footnote 65 I have elsewhere argued that when we have more substantial remains of a manuscript and can more readily consider other factors in addition to palaeography, a more precise date may be possible, as in the case of P.Bodmer 2, the relatively well preserved multi-quire papyrus codex of John's gospel in Geneva.Footnote 66 But for so fragmentary a piece as the Rylands gospel of John, for which palaeography is our only recourse for dating, the most sensible approach is to learn to live with a wider range of possible dates.Footnote 67

4. Conclusion

It is difficult, as the old saying goes, to put the genie back in the bottle. For eighty-five years, P52 has been regarded as the most ancient extant fragment of the New Testament, with a date of ‘circa 125’, or the like. I doubt that I will be able to dislodge the pervasive habit of describing P52 as having been copied ‘circa 125 ce’ anytime soon. It is too deeply ingrained. Articles in academic journals like this one are a good start. Yet, such journals are not the only sites, or perhaps even the most important sites, for the production of knowledge about early Christian manuscripts. I will conclude, then, by noting some positive developments at another important site for the production of knowledge about a manuscript – the didactic materials at the holding institution. This was the beginning of the label on the display case containing P52 in the Rylands Library when I gave this paper in Manchester (2014): ‘The Rylands St John Fragment is one of the Library's most famous objects. It is the oldest dated New Testament writing to survive. It has been dated to about 125 ad. It has not been carbon datedFootnote 68 but dated from the style of handwriting.’Footnote 69 To describe the fragment as a ‘dated writing’ is both confusing and misleading, and the claim that a date of ‘about 125 ad’ could be established ‘from the style of the handwriting’ is equally deceptive.Footnote 70 The label has since been revised and dramatically improved to read as follows:

Fragment of the Gospel of John

Egypt

2nd or early 3rd century ad (uncertain)

This fragment of papyrus is considered by many to be the earliest portion of New Testament writing ever found. It contains incomplete lines from the Gospel of John written in ancient Greek, its original language. The fragment was bought for the Library in Egypt in 1920, but we don't know where it was found. Specialists have identified similar handwriting in documents dating from the early second century to the early third century ad. If our fragment was copied within this timeframe, it is one of the earliest surviving manuscripts of the New Testament and among the oldest archaeological remains of Christianity. It has not been carbon-dated as this would require partial destruction of the fragment.

This label is both more honest and more informative than its predecessor. But I think the label could do even more. We should use didactic materials such as this to raise questions. Why is it so tricky to assign a date to a given artefact? What kinds of debates create the knowledge printed on labels like this one? P52 is an ideal specimen for this type of exposition. The description could be adjusted to provide a more realistic and helpful sense of the state of scholarship on the fragment:

This small fragment contains part of chapter 18 of the Gospel according to John. It was one of several papyri in the collection purchased for the Library on the antiquities market in Egypt in 1920. It thus lacks a secure archaeological provenance. It has not yet been subjected radiocarbon analysis. Its date must therefore be determined only by comparative analysis of its handwriting. Specialists have identified similar handwriting in documents dating from the early second century to the early third century. If the Rylands fragment was copied within this timeframe, it ranks among the earliest surviving manuscripts of the New Testament, and indeed among the earliest extant artefacts of ancient Christians.

Such a label would more accurately reflect the state of scholarship. It would also foreground the important issues of the antiquities trade and the loss of archaeological context, which explains why we are forced to rely on the uncertain art of palaeography to assign a date to the fragment.Footnote 71 At the end of the day, that date (early second to early third century) is not as precise as we (both scholars and the general public) might like, but then again, neither is the art of palaeography of Greek literature of the Roman era.