Introduction

The global expansion of the use of English throughout the last decade has had significant implications for its instruction around the world. Among the issues that have arisen as a result of this expansion has been the selection of appropriate phonological models in the English language classroom. Specifically this particular issue has hinged on the question of whether it is more appropriate to encourage English language learners to strive towards the goal of a particular native variety of English pronunciation, or to promote an alternative target. This question has provoked much discussion, and has been the subject of occasionally heated debate (e.g. Jenkins, Reference Jenkins1998, Reference Jenkins2000; Scheuer, Reference Scheuer2005, Reference Scheuer, Dziubalska-Kołaczyk and Przedlacka2008; Seidlhofer & Jenkins, Reference Seidlhofer, Jenkins and Mair2003).

Despite the relatively high profile occupied by pronunciation in the research as a result of such controversies, pedagogical investigation has been somewhat more elusive; there remains in the field a distinct shortage of empirical studies which investigate the practice of English pronunciation teaching. However, over the past four years, a growing body of research has been fostered by a number of recently-established conferences in Europe dedicated specifically to the study and practice of English pronunciation, among them the Accents and EPIP (English Pronunciation: Issues and Practices) gatherings. One study arising out of these conferences and the research that they have generated aims to address the shortcomings mentioned above. The study is titled EPTiES (English Pronunciation Teaching in Europe Survey), and it is discussed in further detail below.

While much recent research into the worldwide spread of English has focused on its development in so-called expanding circle locations (Kachru, Reference Kachru and Smith1983), this phenomenon has also had a profound impact in Anglophone countries, among them the Republic of Ireland. Ireland represents an intriguing context in which to investigate the study of English as a foreign language. In the early years of the 21st century, the country witnessed unprecedented levels of immigration, and became a popular destination for learners intending to learn English (Citizens Information Board, 2010). More recently, anecdotal evidence has suggested that the number of incoming learners has decreased as a result of the global economic downturn, a reality perhaps reflected in the reduction of English language support resources at secondary level by the Irish Department of Education and Skills. In spite of this, there exists little research to examine the impact that such fluctuations have had on EFL pedagogy in the Irish classroom.

This paper draws together the need for further research both on the practice of ELT in Ireland, and the practice of teaching English pronunciation, by exploring the process of how English pronunciation is taught in EFL environments in Ireland. It reports the findings of a preliminary investigation into the views of EFL teachers in Ireland on the practice of English pronunciation teaching.

ELT in Ireland

The teaching of English as a foreign language in Ireland takes place mainly within two distinct environments: mainstream and private education. Within the first system, ELT takes the form of language support provided for young people from non-English-speaking countries at primary (4–12 years) and post-primary (12–18 years) level. In mainstream education, apart from scheduled extra-curricular English language support classes, learners receiving English language support are fully integrated into the standard curriculum. Within the second environment, the private sector, English is taught to adults as an independent subject, or in conjunction with other subjects as part of a more general qualification (in e.g. business or childcare), in private schools and colleges. A third, less commonplace scenario is one in which English for Specific Purposes (ESP) is taught to groups with very particular language requirements, e.g. pre-sessional and in-sessional courses in English for Academic Purposes taught in higher education institutions to supplement learners' further studies, or courses in Business English provided within corporations to facilitate the communicative skills of international employees.

As previously mentioned, at present there is a dearth of extensive research into existing practices of English language teaching in Irish contexts, though some progress has been made more recently with a report on English instruction in post-primary schools, published by the Trinity Immigration Initiative (TII) (Lyons & Little, 2009). The report was critical of the system, particularly of the fact that most English language support in this environment was provided not by language specialists, but by mainstream subject teachers who took on the role of language support in addition to the teaching of their own specialised subject. The language support system has since been drastically reduced as part of a government initiative to lessen public spending (e.g. The Irish Times, 2010, 2011; Radió Teilifís Éireann, 2011).

However, the study outlined in this paper was carried out not in a mainstream education environment, but in the private sector, across a number of private schools that provide EFL tuition to adult learners. Private sector EFL schools are regulated by the Advisory Council for English Language Schools (ACELS), an independent body charged by the Irish Department of Education with monitoring the EFL sector (Citizens Information Board, 2010). Teachers of English in these institutions must have obtained a primary university degree followed by a TEFL qualification from an ACELS-recognised training programme.

The study described in this paper deals with the specific context of teaching pronunciation to adult EFL learners in the private sector in Ireland. The findings show that while some of the major concerns expressed by EFL teachers are context-specific, others may also apply more broadly to the case of English language teaching in other contexts in Ireland or elsewhere.

The questionnaire

The findings presented in this paper come from a short survey carried out in 2009 amongst a sample of EFL teachers in Ireland to get their feedback on the practice of English pronunciation teaching (Murphy, Reference Murphy2009). This study had three broad aims:

1. To establish a preliminary overview of the practice of EFL pronunciation teaching in an Irish context;

2. To highlight potentially problematic issues in English pronunciation teaching, both unique to the specific case of the Irish private sector, and in ELT more generally;

3. To serve as a foundation for later contribution to a wider, more in-depth investigation of English pronunciation instruction around Europe.

The third of these aims relates to the EPTiES project mentioned in the introduction. EPTiES is short for English Pronunciation Teaching in Europe Survey. It is a collaborative project, led by Alice Henderson of the Université de Savoie, Chambéry and featuring contributions from ten English language teachers and researchers from around Europe. EPTiES was established to obtain information on the status quo of English pronunciation teaching in Europe. It is currently in the data gathering stage, and data analysis is due to commence in September 2011 (Henderson, in progress).

The study presented in this paper was a preliminary investigation that was carried out with the intention of establishing an overview of English pronunciation teaching in Ireland. It consisted of a 10-point questionnaire, distributed to the teachers in four different private sector EFL schools in the Dublin area (this questionnaire may be viewed in the attached appendix). The questions aimed to establish a general overview of the challenges posed and the opportunities provided by the practice of teaching pronunciation in the EFL classroom in Ireland. The responses of 36 teachers were received and analysed using both quantitative and qualitative methods. The results of the survey described in this paper were originally presented at the EPIP conference (English Pronunciation: Issues and Practices) in Chambéry in 2009.

Results and discussion

The first two questions aimed to establish the relative importance placed by teachers on pronunciation relative to other skills in English. 97.2% of all teachers claimed to teach pronunciation at least once per month, with 75.0% claiming to teach it more than once a week. When asked to rate on a four-point scale how important they felt it was to teach pronunciation, 72.2% of respondents selected the most positive response of ‘Very important’, while a further 19.4% selected ‘Important’. These responses suggest that, at least among this particular sample of EFL teachers, pronunciation was still held in some regard – or perhaps to be more precise, pronunciation was still considered as a topic which ought to be held in some regard.

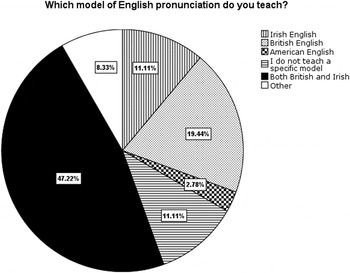

Subsequent questions moved on to the issue of pronunciation teaching practice. Question 3 asked teachers which model of English pronunciation they presented as the target for their learners to approximate. Given the choice between Irish, British and American English, an option stating ‘I do not teach a specific model of pronunciation’, and ‘Other (please specify)’, 19.4% chose British English alone, 11.1% chose Irish English alone, and a further 11.1% claimed not to choose a particular model. However, respondents were not instructed to choose one answer only, with the result that by far the most popular response was a selection of both British and Irish models, which was returned by almost half (47.2%) of all respondents. A summary of the responses to this question can be seen in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Model of English pronunciation taught

This response may be partially explained by the results of the next question, which pertained to the use of specific pronunciation materials. Teachers were asked in Question 4 on which model of pronunciation the majority of their pronunciation learning materials were based. Again, respondents were given a choice between Irish, British or American English, or ‘Other’. This time, the response was overwhelmingly in favour of British English only, with 88.9% of respondents opting for materials based on British English, and 2.8% – only one respondent out of 36 – claiming to use Irish English materials.

Despite the apparent discrepancy between the target pronunciation model and that on which their materials were based, however, teachers were reluctant to be overtly critical of the resources available to them when asked to rate their appropriateness. In Question 5, given a four-point scale with 1 equalling ‘Very appropriate’ and 4 equalling ‘Inappropriate’, the overall mean rating of pronunciation materials was 2.5, with the most frequently-cited response being ‘Appropriate’ (2).

Perhaps a more telling insight, however, came from the individual responses from each teacher, who were asked to follow up their answer with a response to the open-ended question, ‘Please explain why you think these materials are appropriate or not.’ The 23 elaborated responses were overwhelmingly critical in nature, with only two unreservedly positive comments about the pronunciation materials available. Comments included references to the prevalence of British English in the materials, e.g. ‘A major problem is Irish pronunciation often differs from British and American so it can cause confusion. It can be difficult to teach pronunciation that you don't use yourself (being a native Irish speaker).’ Another teacher wrote, ‘The materials are very good but unfortunately are all British.’ A number of other teachers commented on the shortage of useful pronunciation materials for learners at higher levels of proficiency. One teacher, who evaluated her pronunciation materials as ‘Inappropriate’, wrote, ‘There aren't many good materials on pronunciation for higher level learners. The course book doesn't focus on this aspect of English either.’ Another teacher – who also rated his or her pronunciation materials as ‘Inappropriate’ – wrote, ‘They are appropriate for lower levels but not good enough for building learners’ consciousness of pronunciation.'

In Question 6, teachers were asked to describe the effectiveness of techniques used to teach pronunciation. Six teaching approaches and activities, drawn from the author's experiences as a teacher and researcher, were listed as possibilities, along with one simply titled ‘Other’, giving respondents the option of describing any other activities that did not fit into one of the preceding six categories. The responses to this question were interesting in that those activities selected as the most frequently used conflicted with those rated as the most effective. The most frequently-selected activity was ‘You speak and learners repeat what you say’, with 97.2% of respondents claiming to have used this technique within the past three months. (This activity was originally labelled ‘Audiolingualism’, and changed prior to distribution of the survey, bearing in mind that the term ‘Audiolingualism’ may not be a term recognised by those teachers who do not have a research background in Linguistics.) The second most popular activity was ‘You correct learners’ pronunciation as they read out loud', chosen by 91.7% of the sample.

However, the most effective teaching methods and approaches, as rated by the teachers, were those that involved practising intonation (79.3%) and encouraging learners to think of their pronunciation goals (76.2%). Additionally, only 8 of the 36 respondents listed alternative teaching techniques in the ‘Other’ column. Alternative approaches varied widely, and included the use of rhymes, minimal pairs, homophones and drama, focusing on specific recurring pronunciation errors and connected speech, and introducing the IPA chart. The responses to this question were particularly insightful; they suggested a noticeable lack of innovation and diversity in pronunciation teaching, and yet indicated that it may well be those methods that are less frequently used that bring about the greatest success.

The next question, Question 7, was asked with the sole purpose of establishing whether teachers felt they understood their learners' motivation to learn English pronunciation. This question asked teachers what level of pronunciation the majority of their learners would like to achieve. Respondents were presented with seven options: to approximate the standard Irish, British or American model of English; ‘To sound like a native speaker of any variety of English’; or simply ‘To sound clear enough to be understood’ by other non-native speakers or by native speakers. The two most frequently-chosen responses by teachers were ‘To sound clear enough to be understood by native speakers’ and ‘To sound like a native speaker of any variety of English’. As the learners being taught by the participating teachers at the time the survey was taken were not asked to state their goals, the accuracy of teachers' responses could not be precisely ascertained.

However, in a separate survey carried out over the previous four months by the researcher (Murphy, submitted), 147 learners of English as a foreign language were asked the same question that was put to the teachers completing this survey in Question 7. In the learner survey, the top two responses were the same as those given by the teachers: ‘To sound clear enough to be understood by native speakers’ and ‘To sound like a native speaker of any variety of English’. While this is far from conclusive evidence that EFL teachers have a clear insight into what motivates English learners in their study of pronunciation, it does suggest that these teachers may at least have some awareness of what their learners were hoping to achieve.

The next section of the teachers' survey aimed to establish some of the difficulties facing them in their regular English pronunciation teaching tasks. In Question 8, teachers were presented with six groups of learners, and asked to rate how challenging they found each group on a four-point scale of ‘Not challenging’ to ‘Very challenging’. One of the realities of teaching EFL in a native English-speaking country is that English language teaching must take place with groups of learners from a variety of L1 backgrounds, a potentially problematic situation for the instruction of a range of English pronunciation issues. However, no particular group of learners appeared to be highlighted by teachers as more challenging than any other. ‘Group of learners from a particular language background’, ‘Group of young learners’, ‘Group of learners from a variety of language backgrounds’ and ‘Group of learners who work full-time’ were each rated as ‘Somewhat challenging’, ‘Challenging’ or ‘Very challenging’ by over 80% of the teachers who selected them. The least challenging groups were ‘Group of adult learners’ and ‘Group of learners who wish to stay in Ireland long-term’, which were cited as posing some level of challenge by only 69.23% and 59.09% of participating teachers respectively. This suggests that learner motivation may have a role to play in the level of difficulty presented to the teacher, with more motivated learners posing less of a challenge.

Some further insight into why these particular groups might have been cited as more or less challenging was provided with teachers' answers to the follow-up open-ended question; for example:

• ‘One of the examples could be Chinese or Japanese speakers whose mother tongues are completely different from any Indo-European language’;

• ‘Those who work full-time are quite exhausted and I find them to be less responsive’;

• ‘Adults find it harder to speak without an accent. Young learners pick up pronunciation more naturally. It is easier to help learners from a particular language background on a particular pronunciation area. With a group from different L1s, having them mix and work together forces them to pronounce more clearly’;

• ‘Challenges are very local, often individual and do not concern the group’;

• ‘It depends on the individuals.’

These results indicate a wide array of opinions on what constitutes a challenge for an EFL pronunciation teacher, suggesting that there may be some validity in the final two comments listed above – that pronunciation difficulties may be more idiosyncratic in nature, and may be more directly attributable to the individual learner than to entire groups.

The following question was the final closed-ended one on the survey. It asked teachers if they were familiar with two commonly-used terms from EFL pronunciation research, in an effort to explore the degree to which teachers in the EFL private sector were familiar with research currently taking place into EFL pronunciation. The terms cited were ‘English as an International Language’ and ‘English as a Lingua Franca’. The responses were roughly divided between those who said they recognised the terms (44%) and those who said they did not (56%), failing to give a clear indication as to whether teachers were familiar with EFL research terminology or not. A more detailed question or set of questions would be required to establish teachers' understanding of related research content, and more specifically, whether a barrier exists between EFL research and practice.

Conclusions

Let us reconsider this paper in terms of the three goals outlined in the introduction.

Goal #1: To establish a preliminary overview of the practice of EFL pronunciation teaching in an Irish context

This tentative, preliminary investigation of pronunciation teaching practice in the Irish EFL classroom established that pronunciation was still viewed by teachers as having considerable importance for learners, and was taught on a regular basis by the vast majority of participating teachers. In terms of the quality of the teaching provided, the most popular teaching methods were the more traditional ones: correcting learners as they read out loud, and inviting them to mimic their teacher's pronunciation.

However, this contrasted sharply with the activities that were identified by teachers as the most effective, with practising intonation and encouraging learners to think about their pronunciation goals leading that list. The conflict between the most frequently taught pronunciation teaching methods and the most effective ones suggests that teachers may benefit from additional training in a wider variety of more innovative pronunciation teaching methods. It is unclear from these results whether teachers in an alternative Irish EFL context in Ireland would have answered differently; though, given the tendency to appoint mainstream primary and post-primary teachers to the post of English language resource teacher in mainstream education, it seems plausible that further teacher training in this environment could only be of benefit to both teachers and learners.

Goal #2: To highlight potentially problematic issues in English pronunciation teaching, both unique to the specific case of the Irish private sector, and in ELT more generally

When asked to rate a series of six groups according to how challenging they were to teach pronunciation to, four of the six were identified by teachers as presenting some level of challenge, but no one group was rated notably more challenging than the others. This sample of teachers roughly equated the level of difficulty before them in teaching a group of learners from a variety of language backgrounds with teaching a group from specific L1s, or young learners, or learners who work full-time. The only two groups which were identified by notably fewer teachers as challenging were groups of adult learners, and groups of learners who wished to stay in Ireland long-term. It is plausible that these two groups of learners might have a particular vested interest in advancing their English pronunciation; there is an argument to be made that learners who are more motivated to learn pose fewer challenges to their teacher.

When asked about the materials and resources available to them in their English pronunciation teaching, teachers were ostensibly positive about the suitability of their teaching materials. However, the survey showed that while only 19% of teachers base their pronunciation teaching exclusively on a model of British English pronunciation, almost 90% of all teachers claimed that their pronunciation teaching materials were based solely on British English. This also accounted for the fact that so many teachers – nearly half the sample, or 47.2% – were teaching pronunciation based on both British and Irish models. While teachers generally responded favourably when asked about the appropriateness of their pronunciation teaching materials, their comments indicated that they were far from satisfied with them. The discrepancy between pronunciation models and materials suggests that there is a niche in the EFL market for a range of pronunciation instruction resources that either refer to a Hiberno-English phonological model, or that provide the learner with access to a wide range of accents. Given the extraordinary variety of English phonology, there is a strong case to be made for adopting this approach to teaching English pronunciation, particularly in an Anglophone country which does not indigenously feature either British or American English, such as Ireland.

One last end-of-survey comment also highlighted an issue that did not arise in any previous questions. This teacher wrote, ‘The problem is knowing/choosing what to focus on in a class which is time-limited and constantly changing in terms of its make-up.’ This comment alluded to the fact that in the private EFL sector, it is not uncommon for the composition of a class to change on a weekly basis, with students leaving the class or being moved up or down to a new level every week, and new students arriving in – either from outside the school or from another level within the school – just as frequently. This particular problem is not unique to pronunciation teaching, but of course may affect teaching across all skills. At the very least, it is an issue deserving of attention, and one which could be addressed in the form of professional development workshops or seminars within the context of classroom management.

Goal #3: To serve as a foundation for later contribution to a wider, more in-depth investigation of English pronunciation instruction

Despite the small scale of the study, the survey presented in this paper proved insightful enough to form part of the foundation for a later, wider, more in-depth study, which is currently taking place in the form of the EPTiES project. To the best of this author's knowledge, there are currently no further plans to conduct any similar studies in Ireland alone, but should this type of project be carried out in the future, the questions asked in my study, and the tentative findings produced, would form a solid basis from which a more detailed instrument could be built.

What this paper has, I hope, achieved, is to clarify some of the issues and challenges facing the instruction of English pronunciation in the EFL sector in Ireland, a necessary first step towards addressing those issues.

Appendix

This survey is part of an academic study. It is completely anonymous and your results cannot be associated with your name or identity in any way. If you do not wish to answer a question, leave it blank. The results may appear as in academic publications or presentations and will not be published in any way that may identify you or any other person who completes this survey.

1. How often do you (explicitly) teach pronunciation in your English class? Select the option that is closest to your usual teaching routine.

○ More than once a week

○ Less than once a week but more than once a month

○ Approximately once a month or less

○ Never

____________________

2. How important do you think it is to teach pronunciation in an English class?

○ Very important

○ Important

○ Somewhat important

○ Not important

Please explain why.

____________________

3. Which model of English pronunciation do you teach your learners?

○ Irish English

○ British English

○ American English

○ I do not teach a specific model of pronunciation

○ Other (please specify)

____________________

4. On which model of English are most of your teaching materials based?

○ Irish English

○ British English

○ American English

○ Other (please specify)

____________________

5. In your opinion, how appropriate are the available pronunciation teaching materials for your class? Select the option you most agree with.

○ Very appropriate

○ Appropriate

○ Neither appropriate nor inappropriate

○ Inappropriate

Please explain why you think these materials are appropriate or not.

____________________

____________________

6. Which of the following pronunciation teaching methods have you used in your English class within the last three months? Select all that apply and indicate how effective you have found them to be at improving your learners' English pronunciation.

If you selected ‘Other’, please give details of other methods used:

____________________

____________________

7. What level of English pronunciation do you think the majority of your learners would like to achieve?

○ To sound like a native speaker of Irish English

○ To sound like a native speaker of British English

○ To sound like a native speaker of American English

○ To sound like a native speaker of any variety of English

○ To sound clear enough to be understood by other non-native speakers

○ To sound clear enough to be understood by native speakers

○ I don't know

____________________

8. In your opinion, are any of the following groups of learners more challenging than others to teach English pronunciation? Select all that apply.

Please give details.

____________________

____________________

9. Are you familiar with the terms English as an International Language/English as a Lingua Franca (as they are used in English pronunciation research)? Are you aware of any other issues in English pronunciation research? Please give details.

____________________

____________________

If you have any other observations about EFL pronunciation teaching, or any of the issues raised in this survey, please record them here.

____________________

____________________

____________________

Thank you for participating!

DEIRDRE MURPHY has been teaching English to adult learners in Ireland for five years and currently teaches English for Academic Purposes in Trinity College Dublin. She recently completed her PhD in Applied Linguistics in Trinity College on the interface between learner identity, motivation and autonomy in EFL pronunciation learning. She is a regular attendee at international conferences on pronunciation in English, and contributed to Issues in Accents of English 2, edited by Ewa Waniek-Klimczak (2010). More recently she has participated in EPTiES (English Pronunciation Teaching in Europe Survey), a collaborative European project led by Alice Henderson at the Université de Savoie aimed at establishing data on the teaching practices of English language teachers around Europe. Email: murphyd3@tcd.ie

DEIRDRE MURPHY has been teaching English to adult learners in Ireland for five years and currently teaches English for Academic Purposes in Trinity College Dublin. She recently completed her PhD in Applied Linguistics in Trinity College on the interface between learner identity, motivation and autonomy in EFL pronunciation learning. She is a regular attendee at international conferences on pronunciation in English, and contributed to Issues in Accents of English 2, edited by Ewa Waniek-Klimczak (2010). More recently she has participated in EPTiES (English Pronunciation Teaching in Europe Survey), a collaborative European project led by Alice Henderson at the Université de Savoie aimed at establishing data on the teaching practices of English language teachers around Europe. Email: murphyd3@tcd.ie