Background

Medications accounted for 16 percent of all healthcare spending in Canada, a total of $39 billion in 2017 (1), and close to half (43 percent) of all drug-spending is paid for by public-payers (1). Formularies are a tool used to optimize access to, and ensure the appropriate use of, medications. As medications enter the market, they are evaluated at a national and provincial level. However, these reviews are generally focused on the new drug, and do not usually include a re-evaluation of drugs within the same class. Furthermore, drug reviews are typically only conducted at the time of formulary entry, and there are often no routine processes to revisit past decisions to determine whether emerging evidence should influence listing status. This lack of re-evaluation can lead to outdated formularies that are not reflective of current evidence.

Formulary modernization, an approach to align formularies with current evidence has proven successful in various jurisdictions (Reference Morgan, McMahon and Mitton2;Reference Pharmacopeia3). The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health's (CADTH) Therapeutic Review Framework, and the Drug Effectiveness Review Project (DERP) in the United States (US) are examples of such initiatives (Reference Tierney and Manns4;Reference McDonagh, Jonas and Gartlehner5). These frameworks focus on systematic reviews of the available evidence for a specific indication, providing summaries regarding the quality and scope of evidence. These reviews are used to update formularies. However, they may not account for jurisdiction-specific factors such as utilization, accessibility, and current listing, and may not incorporate values and experiences of patients and citizens.

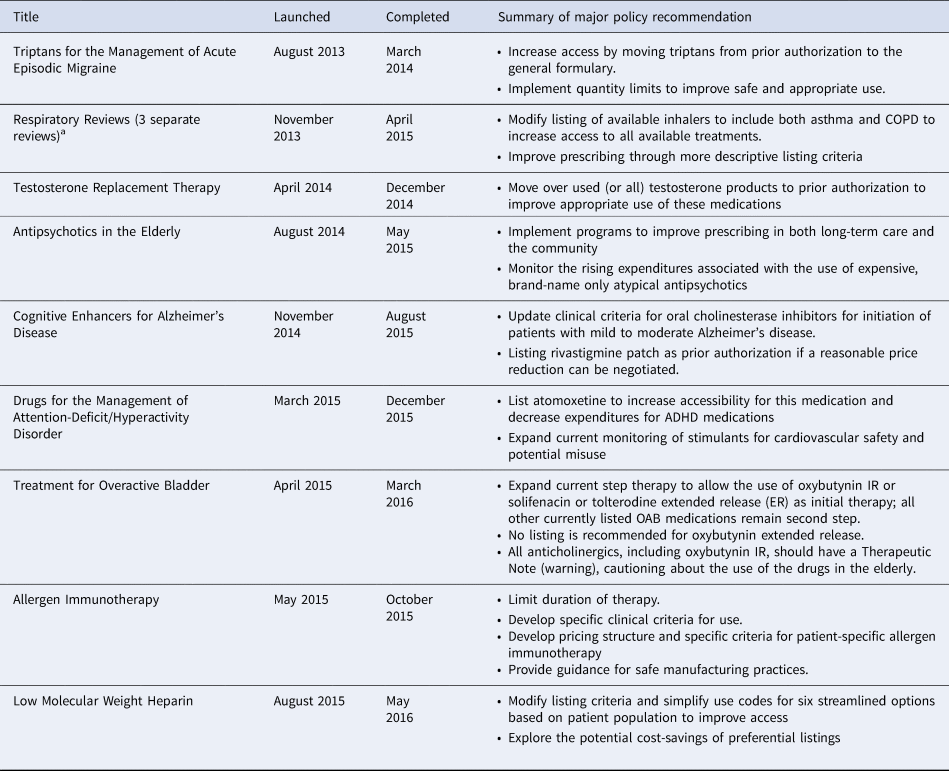

In 2012, the Ontario Drug Policy Research Network (ODPRN) launched a framework for conducting comprehensive drug-class reviews for the Ontario Public Drug Programs (OPDP) within the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC) (Reference Khan, Moore and Gomes6). This framework combines knowledge syntheses of evidence of efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness with the current realities of utilization and access. The results are contextualized within the perspectives of patients and citizens in Ontario. In this paper, we describe the individual components of this framework and lessons learned through the completion of 12 reviews between 2013 and 2016 (Table 1). We also present the ODPRN drug-class review of treatments for chronic hepatitis B (CHB) as a case example to illustrate the impact of this framework (7). We share this description in the hope that others may learn from this example and these lessons may be applied within other systems desirous of implementing a process of formulary modernization.

Table 1. Summary of other completed drug-class reviews

Comprehensive Drug-Class Review Framework

Objective and Process

The aim of the ODPRN drug-class reviews is to conduct comprehensive pragmatic reviews of drug-classes of interest to policymakers, and to provide policy recommendations to modernize the formulary. This process was launched in August 2013. Potential drug-classes for review were selected through consultation with the OPDP. All topics are prioritized for review based on: (i) timeliness, (ii) feasibility, (iii) relevance, and (iv) potential impact. In general, drug-classes are selected based on an outstanding need for review due to recent changes in utilization patterns, new product additions, concerns of misuse, and shifts in evidence.

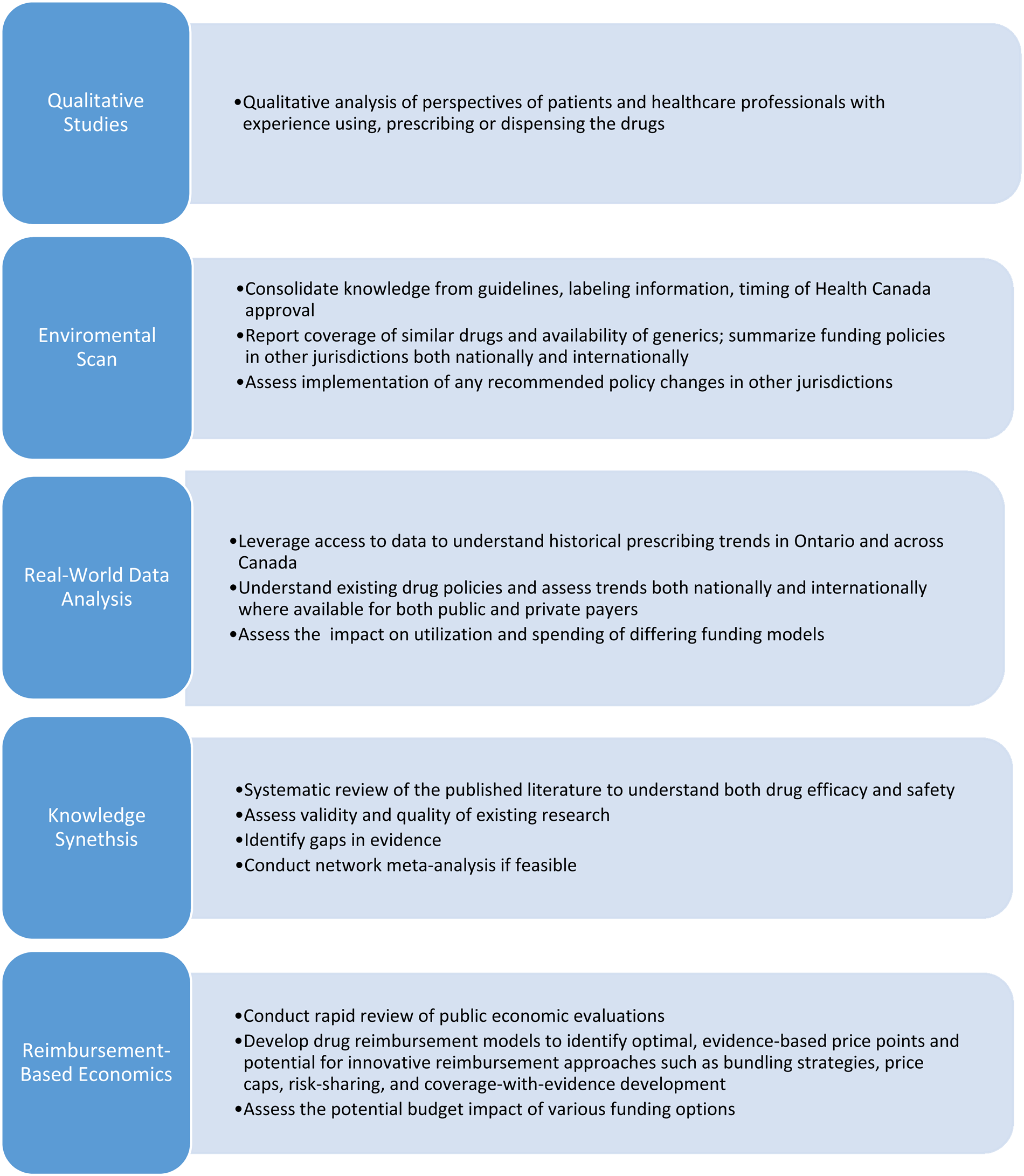

Full reviews are comprised of five components (Figure 1) that include environmental scans, qualitative studies, knowledge synthesis, real-world data analysis, and economic evaluations. The Formulary Modernization Unit acts as the core coordinating body, with each component being led by an independent team.

Fig. 1. Drug-class review components.

Drug-Class Review Process

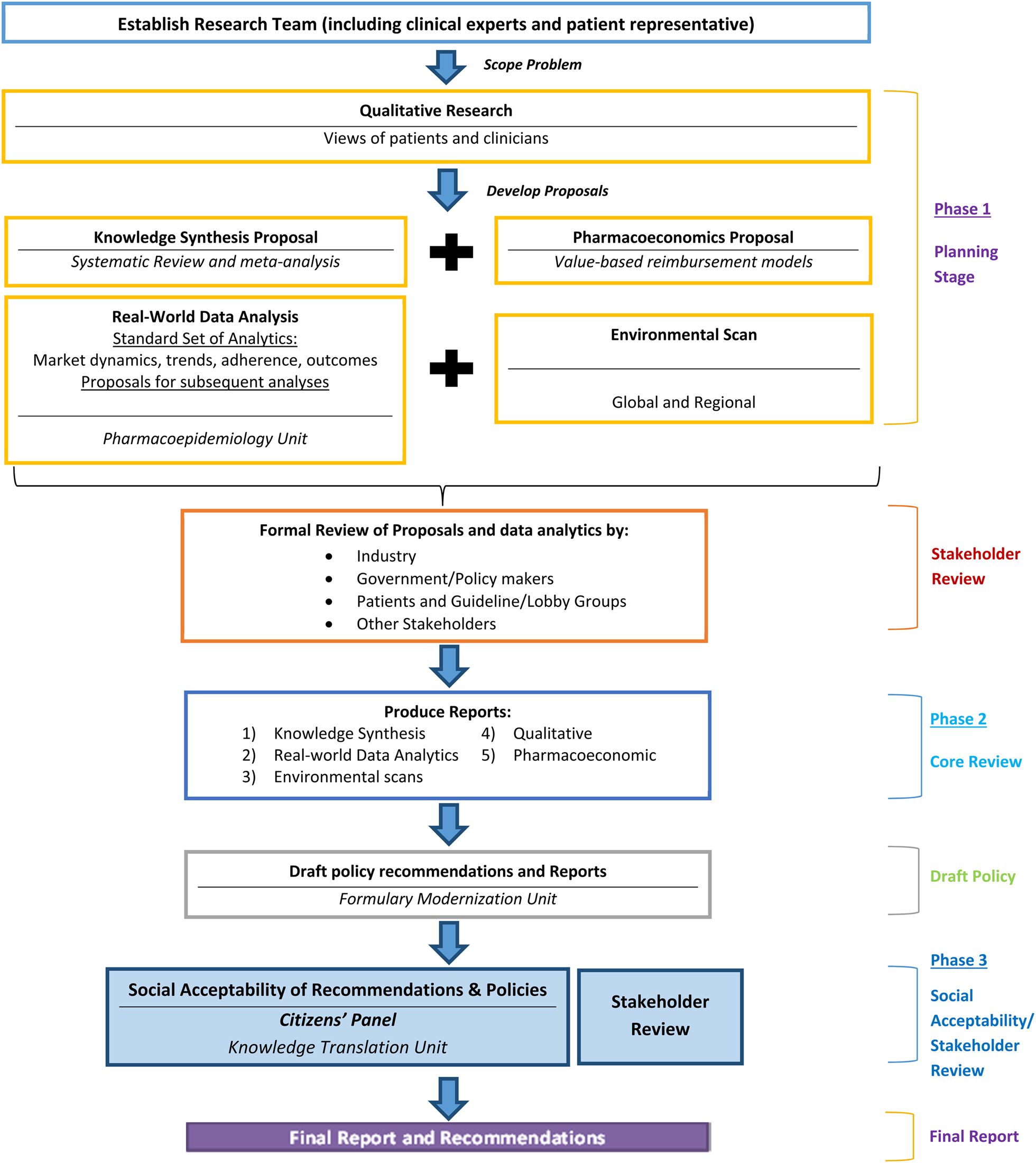

All reviews involve a step-based process to ensure timeliness, integration of components, stakeholder engagement in the planning and development phases, and citizen and patient involvement throughout the process. Regular communication occurs between all teams prior to milestones and at monthly meetings. The reviews are completed in three phases over an 8-month period (Figure 2). The first phase is launched immediately upon selection of the topic and involves the development of proposals. Proposals are posted publicly for feedback, and research plans are updated based on feedback received. Phase 2 is the execution of the components; processes are staggered, so results from some components inform others. For example, qualitative studies and environmental scans are launched first to allow results to help contextualize the work of the other components. Additionally, economic evaluations are completed last, which allows the use of the real-world data analyses and systematic review results. Upon completion of all studies, the final reports are shared between teams, and the Formulary Modernization Unit develops a consolidated report containing potential policy recommendations. All draft reports and potential policy recommendations are publically posted for feedback. The third phase is an active engagement phase and societal acceptability analysis through the engagement of the Citizens' Panel. Upon completion of the third phase, all feedback is compiled, and final recommendations are developed and publicly posted.

Fig. 2. Phases of ODPRN drug-class reviews.

Research Components

Environmental Scans

Environmental scans at the outset of each review summarize background information related to the clinical use, regulatory information, and current reimbursement of all drugs within a drug-class. The goal of the environmental scan is to contextualize the review within Ontario, while also providing comparisons to other jurisdictions. The scan summarizes current guidelines, labeling information, timing of regulatory approval, existing alternatives, and availability of generics. The scan also includes policies and funding decisions in other jurisdictions (nationally and internationally). Importantly, the scan also includes additional information that is relevant to the review but is not captured in other components. For example, in a review of antipsychotics in the elderly, a scan of current initiatives to improve prescribing was included. This topic is an important consideration related to antipsychotic use in the elderly but was not included in other components.

Qualitative Research

Qualitative studies are a distinctive component of the ODPRN framework, and inform the scope of the review and assess the implications of proposed funding recommendations. As part of this component, empirical Ontario-specific qualitative studies are conducted. The qualitative research component aims to capture the opinions and attitudes of patients and/or caregivers and healthcare providers. Qualitative studies are conducted through one-on-one interviews, but in some cases where populations are particularly difficult to reach, surveys are used. The qualitative studies evaluate how existing policies in Ontario impact access, and identify opportunities to enhance the equity of drug policies by addressing variations in the availability of drugs geographically, by gender, and within vulnerable populations. The qualitative studies are conducted prior to other components to allow results to inform other components. For example, results can help inform outcome selection for knowledge synthesis and real-world data analytics.

Knowledge Synthesis

A cornerstone of reviews is the synthesis of clinical evidence. This evidence can include experimental studies, quasi-experimental studies, and observational research. The ODPRN applies a rapid-review methodology to complete searches within a 6- to 8-week timeframe. Rapid-reviews are a knowledge synthesis process that has been simplified to produce information in a timely manner (Reference Tricco, Antony and Zarin8). Searches are similar to traditional literature reviews and include systematic searches of electronic databases (e.g., MEDLINE) and gray literature. To streamline the process, the ODPRN reviews utilize a few efficiencies, including leveraging and updating published systematic reviews, not conducting risk of bias assessments if they were already completed, limiting the breadth of the review, and limiting the number of outcomes extracted. Because the number of outcomes studied must sometimes be restricted, relevant outcomes are selected with input from policymakers, clinicians, and patients. Network meta-analyses are conducted where appropriate to select the best treatment option using indirect comparisons when head-to-head trials did not exist.

Real-World Data Analytics

A component of the ODPRN framework is the implementation of pharmacoepidemiologic studies to incorporate real-world evidence into reviews. Incorporating real-world data provides insights into costs to both public and private payers in Ontario and nationally. Cross-provincial analyses allow comparisons of utilization and spending according to different listing strategies. This requires using both local and national data to allow for appropriate contextualization and regional comparisons. This is accomplished using a variety of data sources available in Canada including ICES' data repository (contains public drug data, hospitalizations/ED visits, and physicians visits for all Ontario residents), IQVIA Health data (contains national prescription rates and drug-costs by province for all payers), and the Canadian Institute for Health Information National Prescription Drug Utilization Information System (contains prescription rates and drug-costs by province for all public payers). By accessing these various data platforms, the pharmacoepidemiology team produces estimates of drug utilization trends over time and between jurisdictions, patient (i.e., demographics, healthcare utilization, and comorbidities) and prescriber (i.e., specialty) profiles, and comparative medication persistence approximations between different drugs available within a class. Lastly, in some cases, rapid-reviews of published observational evidence are conducted to allow insight into particular questions that may not be answered in other components of the review or to allow comparison to results of the analysis. For example, in one review of adult ADHD treatment, a rapid review of observational evidence of misuse of stimulants was conducted to compare with the ODPRN's analysis of the prevalence of inappropriate prescriptions.

Reimbursement-Based Economics

The last component of the review is the economic evaluation, which applies a pragmatic approach to pharmacoeconomic research focusing on assessing the economic impact of different drug reimbursement models (Reference Coyle, Lee and Mamdani9). Analyses are conducted by identifying appropriate modeling frameworks for each drug-class, with a strong focus on identifying the optimal reimbursement model considering both budget impact and cost-effectiveness. Economic evaluations are staggered in the review process and conducted later than other components to allow for: (i) data input from other review components, and (ii) the development of potential policy options based on the findings of other components that can then be modeled in a budget impact analysis. All economic reviews begin with a review of the literature to determine whether previous models have been published that can be leveraged. Based on the results of the review and potential policy recommendations, the decision is made on which type of economic evaluation is necessary. The team also incorporates traditional pharmacoeconomic models (e.g., cost-utility analyses) where relevant to best understand how to optimize access and outcomes while minimizing costs. Comprehensive budget impact analyses leverage data on current utilization and spending in Ontario and other provinces (obtained from the real-world data analysis) to forecast the budget impact of the status quo, as well as a variety of potential policy modifications. De novo models are developed if no previous relevant and robust models were located during the initial literature review. This work is conducted in collaboration with the knowledge synthesis and real-world data analysis team whenever data are needed to populate models.

Stakeholder Engagement

An important component of the ODPRN review framework is the integration of stakeholder feedback, including policymakers, manufacturers, patient groups, and healthcare providers. At the beginning of each review, the research team identifies stakeholder groups relevant to the clinical area being studied, and contacts these groups to inform them of the review process. Details on opportunities for review are also posted broadly on the ODPRN website and through social media. Broad stakeholder engagement is incorporated into the process at two distinct time points: (i) at the completion of draft research plans, and (ii) at the completion of draft reports. Importantly, in the first phase, all stakeholders are asked to submit any evidence believed to be relevant to any component of the review. The ODPRN also hosts two web-conferences open to all stakeholders at each phase of engagement to allow for open discussion, questions, and clarification. After both stakeholder reviews, comments and suggestions can be submitted in writing. Both the queries from the stakeholders and the responses from ODPRN are made public on the ODPRN website to allow for complete transparency. Dissemination at all points is completed using social media and mailing lists.

Citizens' Panel

An important component of the ODPRN process is the integration of public opinion into the development of recommendations. Public opinion is an important consideration for policymakers who are funding drugs in a publicly funded system. The Citizens' Panel, comprised of members of the public, was formed to incorporate public perspectives into an analysis of the broad societal acceptability of potential recommendations. The panel is comprised of twenty-two citizens who reside in Ontario, with varied education, professional experience, and geographical location with a goal to ensure a diversity of knowledge and opinions. Panel members are asked to give input as taxpayers and to take a system-level view (vs. a personal view) of the impact of each recommendation to the health system.

The panel is engaged at the end of each review during the final review period. A survey is conducted prior to, and following each meeting, to gather perceptions on the policy options. The survey captures opinions on the acceptability of each policy option generated in the review by asking participants to rate their agreement with a series of statements on a five-point Likert scale. The Citizens' Panel members are also asked to rank the policy options relative to one another from most to least acceptable from their perspective.

Case Example: Treatment for CHB

Here we summarize the results of the ODPRN drug-class review for CHB to illustrate how the components of the review were applied (7). Hepatitis B is an infectious illness that is estimated to have a prevalence of 1 percent in Canada (Reference Kwong, Crowcroft and Campitelli10–Reference Zhang, Zou and Giulivi13). Poor disease control can lead to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. At the time of the review, there were seven treatments approved by Health Canada: standard interferon, pegylated interferon, lamivudine, adefovir, entecavir, telbivudine, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) (7;Reference Kwong, Crowcroft and Campitelli10;Reference Sherman, Bain and Villeneuve14). In Ontario, treatments for CHB (with the exception of telbivudine and pegylated interferon) were available through prior authorization. Concern had been raised regarding the alignment of reimbursement criteria and guideline recommendations, specifically concerning first-line treatment options and criteria for treatment initiation (Reference Sherman, Bain and Villeneuve14–Reference Terrault, Bzowej and Chang17).

Summary of Findings

Environmental Scan

At the time of the review, the prior authorization criteria were not aligned with Canadian or international clinical guidelines, specifically concerning first-line treatment options and criteria for treatment initiation. Importantly, none of the guidelines took cost-effectiveness, which was an important consideration in the development of reimbursement criteria in Ontario, into account. CHB guidelines recommend TDF or entecavir as the first-line treatment for treatment-naïve patients due to low rates of resistance with these agents. In most jurisdictions across Canada, treatments were more restricted than in Ontario, with preferred listings for older products that are available generically. Five public drug programs had lamivudine listed as a general benefit and newer agents were often highly restricted or not listed.

Qualitative Analysis

Based on the results of the qualitative study, there was a concern that patients in need of treatment in acute situations, such as initiating chemotherapy, would not be able to access medications in a timely fashion due to the potential lag-time between application submission and approval. Additionally, since immigrants comprise a large proportion of the CHB population in Canada (approximately 50 percent), it was felt that steps should be taken to ensure that the process of gaining access to necessary treatments is equitable (Reference Minuk and Uhanova11;Reference Leber and Sherman18). It was also suggested that delayed access may lead to treatment interruptions for patients already initiated on therapy prior to immigrating or among those who had previously paid for their treatment out of pocket. Notably, no health equity issues were specifically identified for Ontario.

Real-World Data Analytics

The real-world data analysis found that the rate of hepatitis B treatment has grown rapidly over the last 10 years with a large increase in spending that is projected to continue to grow (Reference Tadrous, Brahmania and Martins19). Utilization of drugs used in the treatment of CHB in Ontario increased by 34 percent between 2009 and 2014 (from 22,608 to 30,426 prescriptions dispensed) and related costs increased by 59 percent (from $11.9 to $18.8 million). This growth appeared to be largely driven by the introduction of TDF. As expected, comparisons to other provinces found that Ontario had higher utilization than provinces with a stricter listing. In 2013, Ontario had the second highest (behind Alberta) rate of publicly funded CHB medication use (113 users per 100,000 eligible population). TDF had the highest rate of publicly funded use across all provinces, except in British Columbia where lamivudine had the highest rate of use due to its preferential listing.

Safety and Efficacy

The systematic review of sixty-two clinical trials and network meta-analysis found that TDF was the most effective treatment for hepatitis B, followed by entecavir, for the majority of clinical outcomes for both antigen-positive and -negative populations. Outcomes included virologic response, serum alanine aminotransferase normalization, and seroconversion. These outcomes were selected based on feedback from clinicians and patients and the needs of the economic evaluation team to complete their model. The network meta-analysis found that there were few differences in the safety of the various oral agents, other than lamivudine which led to significantly more withdrawals due to adverse events compared with entecavir.

Economic Evaluation

To evaluate the optimal listing, a de novo cost-effectiveness model was developed with inputs from the systematic review and real-world utilization data. It was found that at prices in effect under the prior authorization program, initiating therapy with lamivudine would be optimal for patients without cirrhosis, while initiating therapy with TDF would be optimal for patients with compensated cirrhosis. Neither lamivudine, TDF, nor entecavir was found to be cost-effective at full price. However, if generic entecavir were available at 25 percent of the brand cost and generic substitution were required (per Ontario framework for formulary products where at least three generics exist), it would be optimal to initiate therapy with entecavir. Based on indication, price reductions ranging from 7 to 64 percent would be required to achieve cost-effectiveness with TDF therapy. In the budget impact analysis, leveraging generic substitution for all agents would result in reduced expenditure and allow increased access to entecavir and/or TDF.

Final Recommendations and Policy Outcome

Based on the results of the review and feedback from the ODPRN Citizens' Panel and stakeholders, the recommendation to the OPDP was to move lamivudine and entecavir to the formulary with specific criteria, and update the clinical criteria for all other funded medications. We also suggested that adefovir no longer be reimbursed, due to minimal evidence and utilization.

Several factors were considered in the development of this final recommendation. Firstly, entecavir was found to be the most cost-effective treatment, assuming generic costs at 25 percent of brand costs and enforcement of generic substitution. Moving lamivudine and entecavir to the general formulary would increase access to treatment for treatment-naïve patients, patients already treated successfully, and those in urgent situations. This move would also allow the government to realize cost-savings through generic pricing rules that can only be applied if a medication is listed on the formulary. Importantly, entecavir would only be considered a cost-effective first-line choice if the generic price savings were realized. At the time of the review, TDF did not have a generic version but it was suggested that if generics became available then TDF access also be listed in a similar fashion. Secondly, the Citizens' Panel was presented with multiple potential reimbursement options ranging from listing all agents as general benefits on the formulary to maintaining their funding status. Citizens' Panel members were asked to rank all options. The option that was selected as the final recommendation was selected as the most-acceptable by the Citizens' Panel as it was felt that it achieved a balance between improved access for patients and cost impact.

The final reports were posted in October 2015 and the final findings of the review were presented to the OPDP in January 2016. Subsequently, the OPDP engaged in internal discussions and consulted external experts to help determine their course of action. In February 2018, the OPDP implemented the recommendation of the ODPRN review and moved entecavir, lamivudine, and TDF to the formulary, no longer require prior authorization (20). The ODPRN review was cited as a central component of implementing the policy change (21). At the time of this decision, all products had been genericized allowing the policy change to align with the review recommendations. As part of these changes, the OPDP also stopped funding adefovir for new patients.

Lessons Learned

The completion of twelve reviews allowed for re-assessment of public drug funding across a wide swath of indications that required differing policy mechanisms. From the completion of these reviews, there were some important lessons learned to highlight:

(i) Need for a variety of policy mechanisms

In contrast to the CHB case example, not all reviews were associated with a recommendation of formulary listing changes. Instead, nine of the twelve reviews had major recommendations to improve prescribing either through updated clinical criteria or educational programs. Therefore, despite being aimed for formulary decision makers, sometimes the best evidence points to the non-formulary policy change, which required engagement, investment, and buy-in from other stakeholders. Furthermore, a large component of many of these recommendations related to ensuring optimal use and potential de-prescribing of unnecessary treatments. One policy mechanism that was suggested in five of the twelve reviews was a disinvestment. Often this was associated with products that offered no added benefits to available treatments or formulations but were associated with increased costs. Importantly, although disinvestment recommendations are appealing due to the potential cost-savings, they have been more challenging to implement due to the potential impact on patients already on treatment. Lastly, no single review had only one type of recommendation, with all requiring a combination of policies to address the differing issues that were uncovered during the review process. This complexity supports the importance of conducting a multifaceted approach with differing methods and designs such as the one applied.

(ii) Understanding Jurisdictional Differences

Often when developing policy recommendations, potential solutions are found in other jurisdictions. In some scenarios these solutions were not feasible in the province of Ontario due to considerations such as staff resources and policy requirements. For example, a challenge in more populous provinces like Ontario relates to the ability to easily transfer products to prior authorization programs due to potential capacity issues associated with very high request volumes. In addition, reimbursement criteria for medications on the formulary generally need to align with Health Canada approved indications. This is often challenging for older drugs when manufacturers do not submit requests for expanded indications despite established off-label use.

(iii) Change can take time

As is illustrated in the hepatitis B case example, changes often take time. There may be a lag from review completion to policy change. A variety of factors may impact implementation timelines, ranging from necessary stakeholder engagement to prioritization of funding changes based on anticipated patient benefits and value for money. Unfortunately, delays can lead to a scenario where some information, such as drug utilization trends, may become outdated. It is important to keep stakeholders engaged after review completion to understand what potential roadblocks exist for the implementation of changes. Often simple updates of work may inform policy consideration when the area becomes a priority and ODPRN and OPDP have collaborated to move forward with such updates where appropriate.

(iv) Project Management is essential

The presented framework incorporates a number of components, which requires a large team with diverse research expertise. This required the integration of smaller established teams that operate differently and are geographically distributed. Therefore, resources for project management are required to operate this multidisciplinary team, ensure communication, enforce timelines, and navigate disagreements. The investment of resources and time should not be underestimated.

(v) Leverage established clinical expertise

The completed reviews spanned a variety of clinical areas. In order to complete these reviews to the highest quality, it required the engagement of clinicians in the respective fields. We accomplished this by collecting their perspectives through qualitative research and engaging clinical leaders as team members. Both mechanisms helped ensure recommendations are contextualized within clinical practice.

Conclusions

The ODPRN framework for comprehensive drug-class reviews is a feasible approach to inform formulary modernization. These experiences are drawn from the work in a single jurisdiction and should be contextualized if adopted in other jurisdictions. By incorporating foundational health technology assessment components such as economic evaluations and knowledge synthesis with contextualizing evidence such as patient and clinician perspectives (through qualitative studies), real-world evidence (through data analytics), and cross-jurisdictional comparisons (through environmental scans and data analytics), the ODPRN has been able to develop jurisdictionally specific patient-oriented policy recommendations grounded in evidence. This contextualizing of evidence allows for more actionable policies that are more likely to be pragmatic and useful to decision makers. Adoption of similar frameworks in other jurisdictions may improve uptake of evidence-informed policy recommendations.

Background

Medications accounted for 16 percent of all healthcare spending in Canada, a total of $39 billion in 2017 (1), and close to half (43 percent) of all drug-spending is paid for by public-payers (1). Formularies are a tool used to optimize access to, and ensure the appropriate use of, medications. As medications enter the market, they are evaluated at a national and provincial level. However, these reviews are generally focused on the new drug, and do not usually include a re-evaluation of drugs within the same class. Furthermore, drug reviews are typically only conducted at the time of formulary entry, and there are often no routine processes to revisit past decisions to determine whether emerging evidence should influence listing status. This lack of re-evaluation can lead to outdated formularies that are not reflective of current evidence.

Formulary modernization, an approach to align formularies with current evidence has proven successful in various jurisdictions (Reference Morgan, McMahon and Mitton2;Reference Pharmacopeia3). The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health's (CADTH) Therapeutic Review Framework, and the Drug Effectiveness Review Project (DERP) in the United States (US) are examples of such initiatives (Reference Tierney and Manns4;Reference McDonagh, Jonas and Gartlehner5). These frameworks focus on systematic reviews of the available evidence for a specific indication, providing summaries regarding the quality and scope of evidence. These reviews are used to update formularies. However, they may not account for jurisdiction-specific factors such as utilization, accessibility, and current listing, and may not incorporate values and experiences of patients and citizens.

In 2012, the Ontario Drug Policy Research Network (ODPRN) launched a framework for conducting comprehensive drug-class reviews for the Ontario Public Drug Programs (OPDP) within the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC) (Reference Khan, Moore and Gomes6). This framework combines knowledge syntheses of evidence of efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness with the current realities of utilization and access. The results are contextualized within the perspectives of patients and citizens in Ontario. In this paper, we describe the individual components of this framework and lessons learned through the completion of 12 reviews between 2013 and 2016 (Table 1). We also present the ODPRN drug-class review of treatments for chronic hepatitis B (CHB) as a case example to illustrate the impact of this framework (7). We share this description in the hope that others may learn from this example and these lessons may be applied within other systems desirous of implementing a process of formulary modernization.

Table 1. Summary of other completed drug-class reviews

a Note: The respiratory reviews were a combination of three overlapping but unique reviews of ICS/LABA for COPD, ICS/LABA for Asthma, and LAMAs for COPD.

Comprehensive Drug-Class Review Framework

Objective and Process

The aim of the ODPRN drug-class reviews is to conduct comprehensive pragmatic reviews of drug-classes of interest to policymakers, and to provide policy recommendations to modernize the formulary. This process was launched in August 2013. Potential drug-classes for review were selected through consultation with the OPDP. All topics are prioritized for review based on: (i) timeliness, (ii) feasibility, (iii) relevance, and (iv) potential impact. In general, drug-classes are selected based on an outstanding need for review due to recent changes in utilization patterns, new product additions, concerns of misuse, and shifts in evidence.

Full reviews are comprised of five components (Figure 1) that include environmental scans, qualitative studies, knowledge synthesis, real-world data analysis, and economic evaluations. The Formulary Modernization Unit acts as the core coordinating body, with each component being led by an independent team.

Fig. 1. Drug-class review components.

Drug-Class Review Process

All reviews involve a step-based process to ensure timeliness, integration of components, stakeholder engagement in the planning and development phases, and citizen and patient involvement throughout the process. Regular communication occurs between all teams prior to milestones and at monthly meetings. The reviews are completed in three phases over an 8-month period (Figure 2). The first phase is launched immediately upon selection of the topic and involves the development of proposals. Proposals are posted publicly for feedback, and research plans are updated based on feedback received. Phase 2 is the execution of the components; processes are staggered, so results from some components inform others. For example, qualitative studies and environmental scans are launched first to allow results to help contextualize the work of the other components. Additionally, economic evaluations are completed last, which allows the use of the real-world data analyses and systematic review results. Upon completion of all studies, the final reports are shared between teams, and the Formulary Modernization Unit develops a consolidated report containing potential policy recommendations. All draft reports and potential policy recommendations are publically posted for feedback. The third phase is an active engagement phase and societal acceptability analysis through the engagement of the Citizens' Panel. Upon completion of the third phase, all feedback is compiled, and final recommendations are developed and publicly posted.

Fig. 2. Phases of ODPRN drug-class reviews.

Research Components

Environmental Scans

Environmental scans at the outset of each review summarize background information related to the clinical use, regulatory information, and current reimbursement of all drugs within a drug-class. The goal of the environmental scan is to contextualize the review within Ontario, while also providing comparisons to other jurisdictions. The scan summarizes current guidelines, labeling information, timing of regulatory approval, existing alternatives, and availability of generics. The scan also includes policies and funding decisions in other jurisdictions (nationally and internationally). Importantly, the scan also includes additional information that is relevant to the review but is not captured in other components. For example, in a review of antipsychotics in the elderly, a scan of current initiatives to improve prescribing was included. This topic is an important consideration related to antipsychotic use in the elderly but was not included in other components.

Qualitative Research

Qualitative studies are a distinctive component of the ODPRN framework, and inform the scope of the review and assess the implications of proposed funding recommendations. As part of this component, empirical Ontario-specific qualitative studies are conducted. The qualitative research component aims to capture the opinions and attitudes of patients and/or caregivers and healthcare providers. Qualitative studies are conducted through one-on-one interviews, but in some cases where populations are particularly difficult to reach, surveys are used. The qualitative studies evaluate how existing policies in Ontario impact access, and identify opportunities to enhance the equity of drug policies by addressing variations in the availability of drugs geographically, by gender, and within vulnerable populations. The qualitative studies are conducted prior to other components to allow results to inform other components. For example, results can help inform outcome selection for knowledge synthesis and real-world data analytics.

Knowledge Synthesis

A cornerstone of reviews is the synthesis of clinical evidence. This evidence can include experimental studies, quasi-experimental studies, and observational research. The ODPRN applies a rapid-review methodology to complete searches within a 6- to 8-week timeframe. Rapid-reviews are a knowledge synthesis process that has been simplified to produce information in a timely manner (Reference Tricco, Antony and Zarin8). Searches are similar to traditional literature reviews and include systematic searches of electronic databases (e.g., MEDLINE) and gray literature. To streamline the process, the ODPRN reviews utilize a few efficiencies, including leveraging and updating published systematic reviews, not conducting risk of bias assessments if they were already completed, limiting the breadth of the review, and limiting the number of outcomes extracted. Because the number of outcomes studied must sometimes be restricted, relevant outcomes are selected with input from policymakers, clinicians, and patients. Network meta-analyses are conducted where appropriate to select the best treatment option using indirect comparisons when head-to-head trials did not exist.

Real-World Data Analytics

A component of the ODPRN framework is the implementation of pharmacoepidemiologic studies to incorporate real-world evidence into reviews. Incorporating real-world data provides insights into costs to both public and private payers in Ontario and nationally. Cross-provincial analyses allow comparisons of utilization and spending according to different listing strategies. This requires using both local and national data to allow for appropriate contextualization and regional comparisons. This is accomplished using a variety of data sources available in Canada including ICES' data repository (contains public drug data, hospitalizations/ED visits, and physicians visits for all Ontario residents), IQVIA Health data (contains national prescription rates and drug-costs by province for all payers), and the Canadian Institute for Health Information National Prescription Drug Utilization Information System (contains prescription rates and drug-costs by province for all public payers). By accessing these various data platforms, the pharmacoepidemiology team produces estimates of drug utilization trends over time and between jurisdictions, patient (i.e., demographics, healthcare utilization, and comorbidities) and prescriber (i.e., specialty) profiles, and comparative medication persistence approximations between different drugs available within a class. Lastly, in some cases, rapid-reviews of published observational evidence are conducted to allow insight into particular questions that may not be answered in other components of the review or to allow comparison to results of the analysis. For example, in one review of adult ADHD treatment, a rapid review of observational evidence of misuse of stimulants was conducted to compare with the ODPRN's analysis of the prevalence of inappropriate prescriptions.

Reimbursement-Based Economics

The last component of the review is the economic evaluation, which applies a pragmatic approach to pharmacoeconomic research focusing on assessing the economic impact of different drug reimbursement models (Reference Coyle, Lee and Mamdani9). Analyses are conducted by identifying appropriate modeling frameworks for each drug-class, with a strong focus on identifying the optimal reimbursement model considering both budget impact and cost-effectiveness. Economic evaluations are staggered in the review process and conducted later than other components to allow for: (i) data input from other review components, and (ii) the development of potential policy options based on the findings of other components that can then be modeled in a budget impact analysis. All economic reviews begin with a review of the literature to determine whether previous models have been published that can be leveraged. Based on the results of the review and potential policy recommendations, the decision is made on which type of economic evaluation is necessary. The team also incorporates traditional pharmacoeconomic models (e.g., cost-utility analyses) where relevant to best understand how to optimize access and outcomes while minimizing costs. Comprehensive budget impact analyses leverage data on current utilization and spending in Ontario and other provinces (obtained from the real-world data analysis) to forecast the budget impact of the status quo, as well as a variety of potential policy modifications. De novo models are developed if no previous relevant and robust models were located during the initial literature review. This work is conducted in collaboration with the knowledge synthesis and real-world data analysis team whenever data are needed to populate models.

Stakeholder Engagement

An important component of the ODPRN review framework is the integration of stakeholder feedback, including policymakers, manufacturers, patient groups, and healthcare providers. At the beginning of each review, the research team identifies stakeholder groups relevant to the clinical area being studied, and contacts these groups to inform them of the review process. Details on opportunities for review are also posted broadly on the ODPRN website and through social media. Broad stakeholder engagement is incorporated into the process at two distinct time points: (i) at the completion of draft research plans, and (ii) at the completion of draft reports. Importantly, in the first phase, all stakeholders are asked to submit any evidence believed to be relevant to any component of the review. The ODPRN also hosts two web-conferences open to all stakeholders at each phase of engagement to allow for open discussion, questions, and clarification. After both stakeholder reviews, comments and suggestions can be submitted in writing. Both the queries from the stakeholders and the responses from ODPRN are made public on the ODPRN website to allow for complete transparency. Dissemination at all points is completed using social media and mailing lists.

Citizens' Panel

An important component of the ODPRN process is the integration of public opinion into the development of recommendations. Public opinion is an important consideration for policymakers who are funding drugs in a publicly funded system. The Citizens' Panel, comprised of members of the public, was formed to incorporate public perspectives into an analysis of the broad societal acceptability of potential recommendations. The panel is comprised of twenty-two citizens who reside in Ontario, with varied education, professional experience, and geographical location with a goal to ensure a diversity of knowledge and opinions. Panel members are asked to give input as taxpayers and to take a system-level view (vs. a personal view) of the impact of each recommendation to the health system.

The panel is engaged at the end of each review during the final review period. A survey is conducted prior to, and following each meeting, to gather perceptions on the policy options. The survey captures opinions on the acceptability of each policy option generated in the review by asking participants to rate their agreement with a series of statements on a five-point Likert scale. The Citizens' Panel members are also asked to rank the policy options relative to one another from most to least acceptable from their perspective.

Case Example: Treatment for CHB

Here we summarize the results of the ODPRN drug-class review for CHB to illustrate how the components of the review were applied (7). Hepatitis B is an infectious illness that is estimated to have a prevalence of 1 percent in Canada (Reference Kwong, Crowcroft and Campitelli10–Reference Zhang, Zou and Giulivi13). Poor disease control can lead to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. At the time of the review, there were seven treatments approved by Health Canada: standard interferon, pegylated interferon, lamivudine, adefovir, entecavir, telbivudine, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) (7;Reference Kwong, Crowcroft and Campitelli10;Reference Sherman, Bain and Villeneuve14). In Ontario, treatments for CHB (with the exception of telbivudine and pegylated interferon) were available through prior authorization. Concern had been raised regarding the alignment of reimbursement criteria and guideline recommendations, specifically concerning first-line treatment options and criteria for treatment initiation (Reference Sherman, Bain and Villeneuve14–Reference Terrault, Bzowej and Chang17).

Summary of Findings

Environmental Scan

At the time of the review, the prior authorization criteria were not aligned with Canadian or international clinical guidelines, specifically concerning first-line treatment options and criteria for treatment initiation. Importantly, none of the guidelines took cost-effectiveness, which was an important consideration in the development of reimbursement criteria in Ontario, into account. CHB guidelines recommend TDF or entecavir as the first-line treatment for treatment-naïve patients due to low rates of resistance with these agents. In most jurisdictions across Canada, treatments were more restricted than in Ontario, with preferred listings for older products that are available generically. Five public drug programs had lamivudine listed as a general benefit and newer agents were often highly restricted or not listed.

Qualitative Analysis

Based on the results of the qualitative study, there was a concern that patients in need of treatment in acute situations, such as initiating chemotherapy, would not be able to access medications in a timely fashion due to the potential lag-time between application submission and approval. Additionally, since immigrants comprise a large proportion of the CHB population in Canada (approximately 50 percent), it was felt that steps should be taken to ensure that the process of gaining access to necessary treatments is equitable (Reference Minuk and Uhanova11;Reference Leber and Sherman18). It was also suggested that delayed access may lead to treatment interruptions for patients already initiated on therapy prior to immigrating or among those who had previously paid for their treatment out of pocket. Notably, no health equity issues were specifically identified for Ontario.

Real-World Data Analytics

The real-world data analysis found that the rate of hepatitis B treatment has grown rapidly over the last 10 years with a large increase in spending that is projected to continue to grow (Reference Tadrous, Brahmania and Martins19). Utilization of drugs used in the treatment of CHB in Ontario increased by 34 percent between 2009 and 2014 (from 22,608 to 30,426 prescriptions dispensed) and related costs increased by 59 percent (from $11.9 to $18.8 million). This growth appeared to be largely driven by the introduction of TDF. As expected, comparisons to other provinces found that Ontario had higher utilization than provinces with a stricter listing. In 2013, Ontario had the second highest (behind Alberta) rate of publicly funded CHB medication use (113 users per 100,000 eligible population). TDF had the highest rate of publicly funded use across all provinces, except in British Columbia where lamivudine had the highest rate of use due to its preferential listing.

Safety and Efficacy

The systematic review of sixty-two clinical trials and network meta-analysis found that TDF was the most effective treatment for hepatitis B, followed by entecavir, for the majority of clinical outcomes for both antigen-positive and -negative populations. Outcomes included virologic response, serum alanine aminotransferase normalization, and seroconversion. These outcomes were selected based on feedback from clinicians and patients and the needs of the economic evaluation team to complete their model. The network meta-analysis found that there were few differences in the safety of the various oral agents, other than lamivudine which led to significantly more withdrawals due to adverse events compared with entecavir.

Economic Evaluation

To evaluate the optimal listing, a de novo cost-effectiveness model was developed with inputs from the systematic review and real-world utilization data. It was found that at prices in effect under the prior authorization program, initiating therapy with lamivudine would be optimal for patients without cirrhosis, while initiating therapy with TDF would be optimal for patients with compensated cirrhosis. Neither lamivudine, TDF, nor entecavir was found to be cost-effective at full price. However, if generic entecavir were available at 25 percent of the brand cost and generic substitution were required (per Ontario framework for formulary products where at least three generics exist), it would be optimal to initiate therapy with entecavir. Based on indication, price reductions ranging from 7 to 64 percent would be required to achieve cost-effectiveness with TDF therapy. In the budget impact analysis, leveraging generic substitution for all agents would result in reduced expenditure and allow increased access to entecavir and/or TDF.

Final Recommendations and Policy Outcome

Based on the results of the review and feedback from the ODPRN Citizens' Panel and stakeholders, the recommendation to the OPDP was to move lamivudine and entecavir to the formulary with specific criteria, and update the clinical criteria for all other funded medications. We also suggested that adefovir no longer be reimbursed, due to minimal evidence and utilization.

Several factors were considered in the development of this final recommendation. Firstly, entecavir was found to be the most cost-effective treatment, assuming generic costs at 25 percent of brand costs and enforcement of generic substitution. Moving lamivudine and entecavir to the general formulary would increase access to treatment for treatment-naïve patients, patients already treated successfully, and those in urgent situations. This move would also allow the government to realize cost-savings through generic pricing rules that can only be applied if a medication is listed on the formulary. Importantly, entecavir would only be considered a cost-effective first-line choice if the generic price savings were realized. At the time of the review, TDF did not have a generic version but it was suggested that if generics became available then TDF access also be listed in a similar fashion. Secondly, the Citizens' Panel was presented with multiple potential reimbursement options ranging from listing all agents as general benefits on the formulary to maintaining their funding status. Citizens' Panel members were asked to rank all options. The option that was selected as the final recommendation was selected as the most-acceptable by the Citizens' Panel as it was felt that it achieved a balance between improved access for patients and cost impact.

The final reports were posted in October 2015 and the final findings of the review were presented to the OPDP in January 2016. Subsequently, the OPDP engaged in internal discussions and consulted external experts to help determine their course of action. In February 2018, the OPDP implemented the recommendation of the ODPRN review and moved entecavir, lamivudine, and TDF to the formulary, no longer require prior authorization (20). The ODPRN review was cited as a central component of implementing the policy change (21). At the time of this decision, all products had been genericized allowing the policy change to align with the review recommendations. As part of these changes, the OPDP also stopped funding adefovir for new patients.

Lessons Learned

The completion of twelve reviews allowed for re-assessment of public drug funding across a wide swath of indications that required differing policy mechanisms. From the completion of these reviews, there were some important lessons learned to highlight:

(i) Need for a variety of policy mechanisms

In contrast to the CHB case example, not all reviews were associated with a recommendation of formulary listing changes. Instead, nine of the twelve reviews had major recommendations to improve prescribing either through updated clinical criteria or educational programs. Therefore, despite being aimed for formulary decision makers, sometimes the best evidence points to the non-formulary policy change, which required engagement, investment, and buy-in from other stakeholders. Furthermore, a large component of many of these recommendations related to ensuring optimal use and potential de-prescribing of unnecessary treatments. One policy mechanism that was suggested in five of the twelve reviews was a disinvestment. Often this was associated with products that offered no added benefits to available treatments or formulations but were associated with increased costs. Importantly, although disinvestment recommendations are appealing due to the potential cost-savings, they have been more challenging to implement due to the potential impact on patients already on treatment. Lastly, no single review had only one type of recommendation, with all requiring a combination of policies to address the differing issues that were uncovered during the review process. This complexity supports the importance of conducting a multifaceted approach with differing methods and designs such as the one applied.

(ii) Understanding Jurisdictional Differences

Often when developing policy recommendations, potential solutions are found in other jurisdictions. In some scenarios these solutions were not feasible in the province of Ontario due to considerations such as staff resources and policy requirements. For example, a challenge in more populous provinces like Ontario relates to the ability to easily transfer products to prior authorization programs due to potential capacity issues associated with very high request volumes. In addition, reimbursement criteria for medications on the formulary generally need to align with Health Canada approved indications. This is often challenging for older drugs when manufacturers do not submit requests for expanded indications despite established off-label use.

(iii) Change can take time

As is illustrated in the hepatitis B case example, changes often take time. There may be a lag from review completion to policy change. A variety of factors may impact implementation timelines, ranging from necessary stakeholder engagement to prioritization of funding changes based on anticipated patient benefits and value for money. Unfortunately, delays can lead to a scenario where some information, such as drug utilization trends, may become outdated. It is important to keep stakeholders engaged after review completion to understand what potential roadblocks exist for the implementation of changes. Often simple updates of work may inform policy consideration when the area becomes a priority and ODPRN and OPDP have collaborated to move forward with such updates where appropriate.

(iv) Project Management is essential

The presented framework incorporates a number of components, which requires a large team with diverse research expertise. This required the integration of smaller established teams that operate differently and are geographically distributed. Therefore, resources for project management are required to operate this multidisciplinary team, ensure communication, enforce timelines, and navigate disagreements. The investment of resources and time should not be underestimated.

(v) Leverage established clinical expertise

The completed reviews spanned a variety of clinical areas. In order to complete these reviews to the highest quality, it required the engagement of clinicians in the respective fields. We accomplished this by collecting their perspectives through qualitative research and engaging clinical leaders as team members. Both mechanisms helped ensure recommendations are contextualized within clinical practice.

Conclusions

The ODPRN framework for comprehensive drug-class reviews is a feasible approach to inform formulary modernization. These experiences are drawn from the work in a single jurisdiction and should be contextualized if adopted in other jurisdictions. By incorporating foundational health technology assessment components such as economic evaluations and knowledge synthesis with contextualizing evidence such as patient and clinician perspectives (through qualitative studies), real-world evidence (through data analytics), and cross-jurisdictional comparisons (through environmental scans and data analytics), the ODPRN has been able to develop jurisdictionally specific patient-oriented policy recommendations grounded in evidence. This contextualizing of evidence allows for more actionable policies that are more likely to be pragmatic and useful to decision makers. Adoption of similar frameworks in other jurisdictions may improve uptake of evidence-informed policy recommendations.

Funding Sources

Some of the work discussed in this manuscript was funded by a grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC) Health System Research Fund. The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent of the funding sources. No endorsement by the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred.

Disclosures

Dr. Mamdani reports personal fees from Novo Nordisk, personal fees from Amgen, personal fees from Allergan, outside the submitted work. Dr. Oh reports other from Amgen, other from Astra Zeneca, other from Roche, outside the submitted work. No other authors have any conflicts of interest to declare.