Throughout human history, pandemics have shaped how work is understood, carried out, and organized. For example, historians have suggested that following the Black Plague in 1350, laws and attitudes regarding labor and compensation changed across Western Europe (Cohn, Reference Cohn2007). Similarly, in the midst of the 1918 flu pandemic, which disproportionately affected working-age adults, labor uprisings in the United States resulted in hundreds of thousands of workers walking off their jobs in protest of working conditions (Clay, Reference Clay2020; Freeman, Reference Freeman2020). Following the 1918 pandemic, workers saw improvements in health and safety protections, including the advent of employer-sponsored health insurance schemes (Spinney, Reference Spinney2020). More recently, the SARS pandemic of 2003 had demonstrable effects on the health and well-being of essential workers in “systems-relevant” occupations, with between 18% and 57% of frontline healthcare workers reporting experiencing high levels of emotional distress while managing this crisis (Maunder etal., Reference Maunder, Lancee, Balderson, Bennett, Borgundvaag, Evans, Fernandes, Goodman, Gupta, Hunter, Hall, Nagle, Payne, Peczeniuk, Raymond, Read, Rourke, Steinberg, Stewart and Wasylenki2006).

Since the World Health Organization (WHO, 2020) declared the novel coronavirus COVID-19 as a global pandemic crisis on March 11, 2020, there have been over 4.2 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 in 177 countries (approximately one third or 33% of confirmed cases have occurred in the United States alone) and over 289,000 associated deaths, worldwide (n.b., statistics as of May 12, 2020; see Wu etal., 2020). Apart from immediate health consequences and mortality, it is still too soon to know the scope of the psychological, social, economic, and cultural impact of COVID-19. However, as in the historical examples offered above, there are already tangible global effects of COVID-19 on work-related processes. In the United States, jobless rates have skyrocketed to levels never before seen, with 3.3 million new unemployment claims posted in the week of March 23, 2020 alone, which doubled to 6.6 million the following week, up to a total of 16.78 million total claims in the week of April 6 (n.b., the highest rate of new claims ever previously recorded was 695,000 in October 1982; Cox, Reference Cox2020a, Reference Cox2020b). As of May 7, one in five American workers had filed for unemployment benefits (totaling approximately 33.5 million claims over 7 weeks; Tappe, Reference Tappe2020).

Similar patterns have been observed globally; however, they are buffered to some extent by more proactive and progressive state-supported social and economic policies. For example, as of March 3, one million job losses were reported across European Union member states (Zsiros, Reference Zsiros2020). Economic projections suggest that unemployment across the European Union is expected to rise to 9% in 2020. Among member states, Greece and Spain are expected to experience the highest unemployment rates (19.90% and 18.90%, respectively), whereas Germany is expected to experience the lowest unemployment rate (4%). To address such concerns, the European Central Bank announced over €870 billion in economic stimulus programs, an amount equivalent to 7.3% of the Eurozone GDP (Lagarde, Reference Lagarde2020). In Germany, economic projections suggest that as many as three million people’s employment could be displaced as a result of this crisis (Escrit, Reference Escrit2020), while nearly 500 thousand employers have applied for government subsidized Kurzarbeit or “short-time work” funds to cover losses of income that are associated with reduced working hours (Schmitz, Reference Schmitz2020). Asia has been particularly affected as well; for example, China’s exports have dropped drastically since the virus’s inception (Wong, Reference Wong2020). Moreover, a United Nations report suggests that as many as 400 million workers in India, an economy that is highly dependent on informal work arrangements, will be displaced by the pandemic crisis (Thomas, Reference Thomas2020). Broader but related system challenges have also been noted (e.g., lack of medical resources and supplies; Jacobs etal., Reference Jacobs, Richtel and Baker2020) and considered (e.g., hindrances to food supply chains; Splitter, Reference Splitter2020).

Clearly, the COVID-19 pandemic crisis presents a number of tangible challenges, including imposing various psychological consequences on individuals (see Van Bavel etal., Reference Van Bavel, Baicker, Boggio, Capraro, Cichocka, Cikara, Crockett, Crum, Douglas, Druckman, Drury, Dube, Ellemers, Finkel, Fowler, Gelfand, Han, Haslam, Jetten and Willer2020). Such challenges have particular bearing on our understanding of various work-related processes. For example, people are experiencing increased work and family demands, especially as they navigate the need to rebalance multiple roles across work with personal lives. For many, mass work-from-home policies have already blurred this distinction. Various external demands are likewise increasing, for example, experiencing increased uncertainty, particularly around job security and financial difficulties. Consistently, a recent study conducted in New Zealand found that a nationwide lockdown resulted in higher rates of mental distress (Sibley etal., Reference Sibley, Greaves, Satherley, Wilson, Overall, Lee, Milojev, Bulbulia, Osborne, Milfont, Houkamau, Duck, Vickers-Jones and Barlow2020). Workers may likewise face paradoxes in how their work is organized, such as experiencing increased workloads in some respects while simultaneously managing the experience of boredom and idle time, and perhaps low workloads, in others. At the same time that such demands and challenges are emerging, this crisis also presents a number of opportunities, especially considering various resources that can be afforded by work organizations to support employees now and possibly into the future. For example, these opportunities may include potential for increased social and organizational support from leadership, digitization of work processes, implementation of more effective teamwork, and changes to policies around health management.

Industrial and organizational (I-O) psychology is uniquely positioned to provide guidance with respect to how COVID-19 and potential future pandemics will likely influence work and people in organizations by providing evidence-based advice for navigating the challenges and opportunities that are presented by such crises. Such guidance comes in the form of both research and practical implications. In this focal article, we discuss 10 of the most relevant areas of research and practice that are likely to be influenced by COVID-19 and potential future pandemics: These 10 topics include (a) occupational health and safety, (b) work–family issues, (c) telecommuting, (d) virtual teamwork, (e) job insecurity, (f) precarious work, (g) leadership, (h) human resources policy, (i) the aging workforce, and (j) careers.

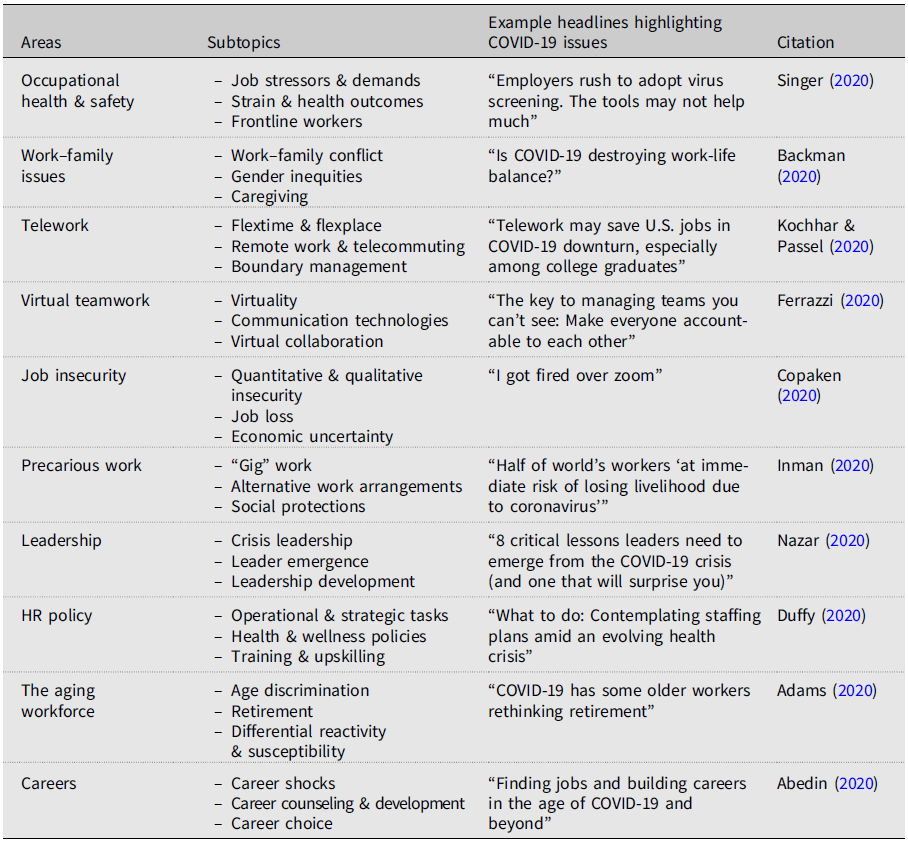

We chose to focus on these 10 areas for two reasons: First, over the past 2 months, each of these areas has been variously implicated as “central” to the effects that the COVID-19 pandemic has had and will continue to have on work-related processes. For example, we have already seen evidence for each of these areas discussed in the media surrounding the influence of this pandemic crisis on work. To give a sense of this, Table 1 provides a summary of these 10 areas, with examples of the various “subtopics” that are subsumed within each. The table also highlights prototypical media headlines that embody how the COVID-19 pandemic has been affected by or is affecting work-related processes in each area.

Table 1. Summary of 10 Areas, “Subtopics,” and Prototypical Headlines

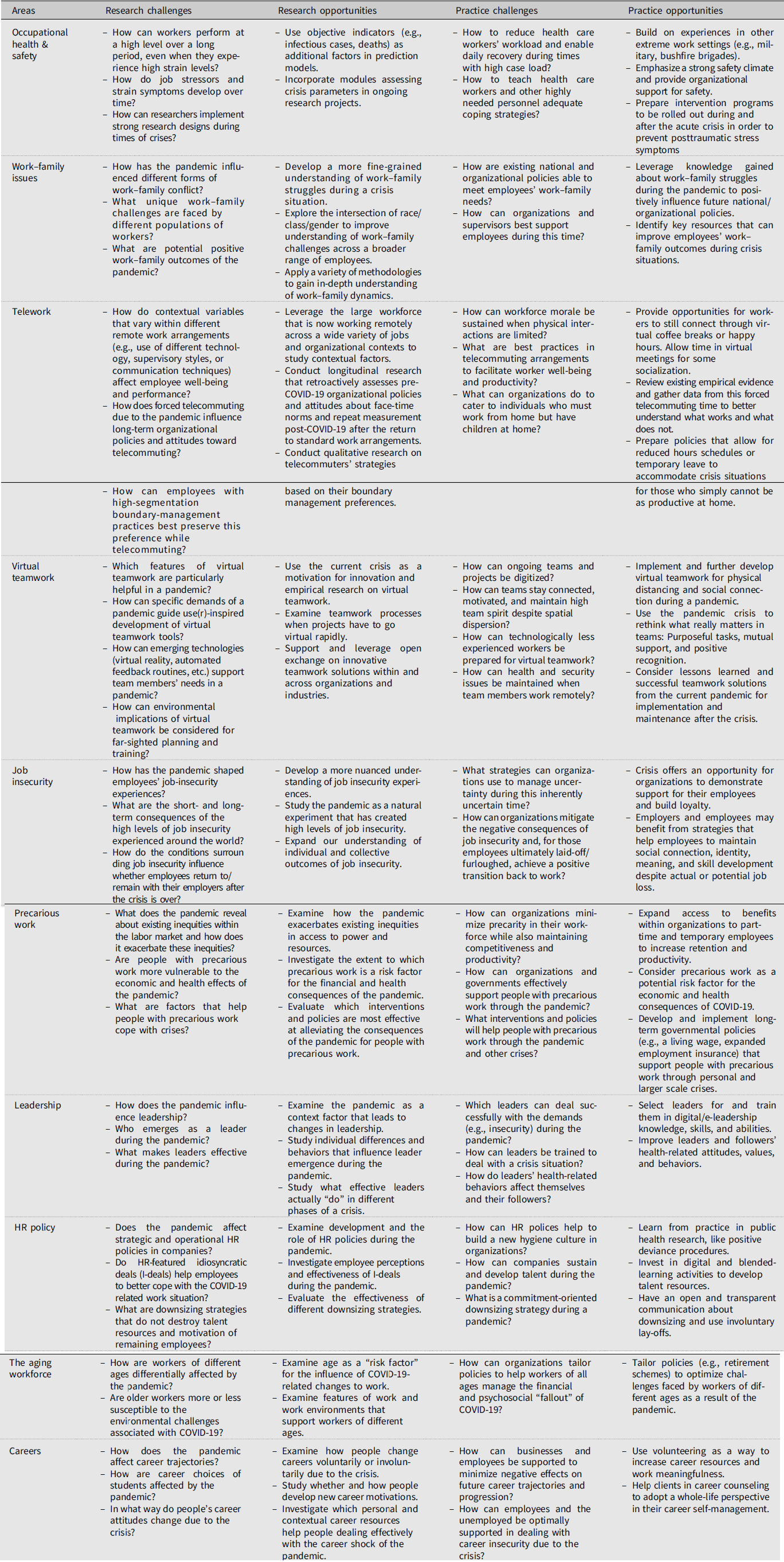

Second, both challenges and opportunities surrounding these 10 areas are likely to have long-term effects on how work is understood, carried out, and organized. Given their centrality to a wide variety of work-related processes, these are also the areas that are likely to be prominent in the case of future pandemic crises and that have a specific bearing on both research and practice in I-O psychology. To this end, Table 2 summarizes examples of research and practice challenges and opportunities that COVID-19 presents for each area. To be clear, we by no means consider these 10 areas to be inclusive of all of the various ways in which work has been or will be affected by COVID-19 or any future pandemic crisis. However, we see these areas as those that would be most generally applicable to the study of any pandemic’s influence on work behavior, broadly defined. We hope that the commentaries on this focal article will offer additional ideas for how work will change and be variously affected by this and future pandemic crises.

Table 2. Summary of Research and Practice Challenges and Opportunities Associated With COVID-19

With a clearer sense of the motivation of this article, our attention now turns to a discussion of these 10 topics. We then conclude with a high-level summary of this discussion and a challenge to I-O psychologists to address these issues in their research and practice.

1. Occupational health and safety

The COVID-19 pandemic crisis is highly relevant for occupational health and safety. In general, research and practice activities within this field address topics related to the prevention of health risks at work and to the promotion of employee health, safety, and well-being. The psychological perspective on occupational health and safety focuses on factors in the work environment that may limit employee strain reactions, as well as those that may harm (versus protect) the quality of working life. Harmful factors are usually called “job stressors” or “job demands,” and protective factors are often summarized under the umbrella term of “job resources.”

The ongoing pandemic crisis affects occupational health and safety in many respects, although to a largely different degree between occupational groups. For instance, it is important to differentiate between healthcare workers, people working in other jobs that are highly needed during the crisis, and persons starting to work from home. In addition, persons who are laid-off or are facing furloughs or reduced working hours are strongly affected by the pandemic crisis because they are threatened by unemployment and increased job insecurity (see also Blustein etal., Reference Blustein, Duffy, Ferreira, Cohen-Scali, Cinamon and Allan2020).

Healthcare workers, particularly those who are working with (possibly infected) patients in frontline jobs, face very high levels of job stress and associated strain symptoms during the crisis (see Adams & Walls, Reference Adams and Walls2020). Although empirical evidence on the occupational health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis is still limited (Lai etal., Reference Lai, Ma, Wang, Cai, Hu, Wei, Wu, Du, Che, Li, Tan, Kang, Yao, Huang, Wang, Wang, Liu and Hu2020; Zhu etal., Reference Zhu, Xu, Wang, Liu, Wu, Li, Miao, Zhang, Yang, Sun, Zhu, Fan, Hu, Liu and Wang2020), research on earlier infectious disease outbreaks (e.g., the SARS outbreak in 2002/2003 and the MERS outbreak in 2015) suggests that healthcare workers’ strain experiences are greatly increased by crises, with nurses and employees working in high-risk environments being particularly affected (Brooks etal., Reference Brooks, Dunn, Amlôt, Rubin and Greenberg2018; Lee at al., 2018).

Working in health care during a pandemic crisis must be seen as a “critical incident” that has a strong emotional effect on employees that may exceed their abilities to cope with the ongoing demands (De Boer etal., Reference De Boer, Lok, van’t Verlaat, Duivenvoorden, Bakker and Smit2011; Restubog etal., Reference Restubog, Ocampo and Wang2020). Typical job stressors that are present during such a crisis include high workloads, hazardous work environments, unclear job instructions, and ambiguous infection control policies, as well as being blamed for mistakes and having to handle coworkers’ negative emotions (Tam etal., Reference Tam, Pang, Lam and Chiu2004). Not surprisingly, fears of being infected are widespread and positively associated with feelings of distress (Wong etal., Reference Wong, Yau, Chan, Kwong, Ho, Lau, Lau and Lit2005; Zhu etal., Reference Zhu, Xu, Wang, Liu, Wu, Li, Miao, Zhang, Yang, Sun, Zhu, Fan, Hu, Liu and Wang2020). Lack of adequate protection and low perceived organizational support are associated with strain symptoms and with concerns for one’s personal and family health (Maunder etal., Reference Maunder, Lancee, Balderson, Bennett, Borgundvaag, Evans, Fernandes, Goodman, Gupta, Hunter, Hall, Nagle, Payne, Peczeniuk, Raymond, Read, Rourke, Steinberg, Stewart and Wasylenki2006; Nickell etal., Reference Nickell, Crighton, Tracy, Al-Enazy, Bolaji, Hanjrah, Hussain, Makhlouf and Upshur2004). Moreover, daily work becomes particularly tense when the allocation of treatment resources becomes constrained because not enough resources are available for the number of patients who would need them (Wright etal., Reference Wright, Meyer, Reay and Staggs2020).

Working under highly stressful and unsafe conditions during a pandemic crisis may not only have immediate negative effects on healthcare workers’ mental health and well-being but may develop into longer-term impairments as well, including posttraumatic stress symptoms (Maunder etal., Reference Maunder, Lancee, Balderson, Bennett, Borgundvaag, Evans, Fernandes, Goodman, Gupta, Hunter, Hall, Nagle, Payne, Peczeniuk, Raymond, Read, Rourke, Steinberg, Stewart and Wasylenki2006; McAlonan etal., Reference McAlonan, Lee, Cheung, Cheung, Tsang, Sham, Chua and Wong2007).

Although a pandemic crisis puts a particularly heavy burden on the healthcare sector, health and safety issues are affected in many other jobs as well. Jobs in businesses that continue to provide service to the public (e.g., grocery clerks, drivers, distribution center employees, and employees working in the food-delivery business), as well as managerial and administrative staff in public and private organizations that need to adjust their operations to the ongoing crisis are also facing highly stressful times. Although employees working in these types of jobs during the crisis have not yet received much research attention, one can assume that they are experiencing a high workload, increased infection risk, and high job ambiguity.

Overall, employees who are working from home during a pandemic crisis seem to be better off because often they do not face increased infection risks and because they have a high discretion about how and when to do their work. Employees who do not usually work from home, however, may lack the adequate space, equipment, and materials to do their work in this unusual setting. Moreover, they may find it difficult to structure their workdays. Because working from home often implies a higher level of autonomy, strain symptoms such as exhaustion may be lower, but social isolation may increase, and coworker relationship quality may suffer (Allen etal., Reference Allen, Golden and Shockley2015; see also the section on telecommuting).

Although there is some knowledge regarding how a pandemic crisis may affect occupational health and safety (Brooks etal., Reference Brooks, Dunn, Amlôt, Rubin and Greenberg2018), more research in this area is needed. It will be important to examine job stress as well as health and safety issues in not only the healthcare sector but also in other businesses and industries that face particularly stressful conditions during the pandemic crisis (e.g., grocery stores, transportation, and logistics firms).

First, research on employee health and safety during a pandemic crisis should not examine only the factors that make work stressful; it should also address resources that may help to alleviate the negative effects of the high-stress situation. For instance, researchers may build on a general model such as the job-demands-resources model (Bakker etal., Reference Bakker, Demerouti and Sanz-Vergel2014) and may want to examine both organizational factors such as safety climate and good organizational communication strategies (Moore etal., Reference Moore, Gamage, Bryce, Copes, Yassi and Group2005) and individual prerequisites such as adequate levels of training and the availability of specific coping strategies (Maunder etal., Reference Maunder, Lancee, Balderson, Bennett, Borgundvaag, Evans, Fernandes, Goodman, Gupta, Hunter, Hall, Nagle, Payne, Peczeniuk, Raymond, Read, Rourke, Steinberg, Stewart and Wasylenki2006; Wong etal., Reference Wong, Yau, Chan, Kwong, Ho, Lau, Lau and Lit2005). Research that is done in extreme work environments such as the military or bushfire brigades might contribute to a better understanding of the strategies that are important for coping with extremely stressful situations (Nassif etal., Reference Nassif, Start, Toblin and Adler2019). Moreover, from a practical perspective, it is highly important to examine which interventions can be used to reduce posttraumatic symptoms in employees who have been exposed to traumatic situations during the pandemic crisis. Again, approaches that are used in other extreme environments could provide useful insights (Adler etal., Reference Adler, Bliese, McGurk, Hoge and Castro2011).

Second, working during a pandemic crisis is associated with high strain levels, particularly in employees in the healthcare sector and other frontline workers. These high strain levels are not just unfortunate; they may impair daily functioning at work (Bakker & Costa, Reference Bakker and Costa2014), which might lead to inefficiencies and risky behaviors. For instance, research has shown that hand hygiene in hospitals is neglected during long shifts and when the time between shifts is short (Dai etal., Reference Dai, Milkman, Hofmann and Staats2015). Therefore, it is important that research identifies factors that help employees function well—even when they are experiencing high strain levels.

Third, when studying occupational health and safety, the dynamic nature of the pandemic crisis has to be taken into account. Most probably, stress experiences differ largely between preparatory and high-crisis states. Accordingly, reductions of stressors (e.g., high workload) might not be feasible during high-crisis states and the effectiveness of resources might change as the severity of the situation increases. From a research perspective, the timing of measurements needs a lot of attention. At the same time, the dynamic characteristics of a pandemic crisis offers the opportunity to study temporal aspects of job stress at a more detailed level than can be done in most other settings (Sonnentag etal., Reference Sonnentag, Pundt, Albrecht, Shipp and Fried2014). Empirical studies additionally could take into account objective crisis indicators in specific regions at specific points (e.g., number of infectious cases, administrative regulations at the country or regional level) and relate these objective crisis indicators to strain indicators (e.g., anxiety, fatigue).

Fourth, researchers should strive to implement strong research designs, such as longitudinal data collection and approaches that help to overcome the endogeneity problem (Bliese etal., Reference Bliese, Schepker, Essman and Ployhart2020). Until now, most occupational-health research on infectious disease outbreaks is cross-sectional in nature and uses exclusively self-report measures. On one hand, such a research strategy is understandable because data collection has to be started quickly—often with very limited financial resources; on the other hand, such designs allow only very limited insight into causal processes. Accordingly, researchers should try to implement more powerful research designs. One possibility would be to use ongoing longitudinal data-collection efforts that have been started before the disease outbreak and to incorporate additional measurement waves that address the emerging crisis situation. Moreover, it has to be taken into account that research participation might be difficult for people working in a crisis mode. Here, innovative approaches are needed; for example, one might think of collecting extremely short yet validated measures or of integrating data collection into intervention approaches that seek to improve coping support.

In terms of practical recommendations, Brooks etal. (Reference Brooks, Dunn, Amlôt, Rubin and Greenberg2018) summarized important implications of research evidence that was gathered during the SARS crisis. These implications include the provision of adequate training about infection control, building team cohesion and social support, enhancing communication strategies, preparation for negative experiences, and the development of adequate coping strategies. Thus, self-care, team care, and increased awareness about the need to be resilient are particularly important (Adler etal., Reference Adler, Adrian, Hemphill, Scaro, Sipos and Thomas2017; Cleary etal., Reference Cleary, Kornhaber, Thapa, West and Visentin2018).

2. Work–family issues

The COVID-19 pandemic crisis has affected the work–family interface in a variety of ways, as many recent popular press articles have highlighted (e.g., Friedman & Westring, Reference Friedman and Westring2020; Petersen, Reference Petersen2020). The majority of attention has focused on the topic of work–family conflict, defined as interrole conflict in which the demands of work and family are incompatible in some way (Greenhaus & Beutell, Reference Greenhaus and Beutell1985). Unfortunately, little is known about work and family dynamics specifically during crisis situations (Eby etal., Reference Eby, Mitchell, Zimmerman, Allen and Eby2016).

Despite the lack of research in this area, there are several reasons to expect elevated levels of work–family conflict during this pandemic crisis, particularly time-based conflict—when time spent in one domain hinders performance in another—and strain-based conflict—when strains (e.g., tension, anxiety) experienced in one domain negatively affect performance in another domain (Carlson etal., Reference Carlson, Kacmar and Williams2000). With many schools and childcare facilities closed, parents are faced with additional responsibilities in caring for and/or homeschooling their children during the workday. Time-based conflict is therefore likely to increase because many individuals are spending their traditional “work hours” on paid work while simultaneously caring for children. Strain-based conflict is also likely to be elevated during COVID-19 because individuals are experiencing heightened psychological distress and anxiety in general, coupled with increased anxiety and stress about meeting the unique demands that are posed by work and family.

Researchers could also explore additional types of work–family conflict that may be particularly relevant during this time. Energy-based conflict, defined as that point at which physical exhaustion that is experienced in one role reduces performance in another role (Greenhaus etal., Reference Greenhaus, Allen, Spector, Perrewé and Ganster2006), may be much higher than usual for healthcare workers who are working in overflowing emergency rooms or for overextended working parents who are caring for young children. Cognitive-based conflict involves reduced performance due to preoccupation with another role (Ezzedeen & Swiercz, Reference Ezzedeen and Swiercz2007) and may be elevated during this time because individuals worry about how the pandemic crisis will affect their families. Experience sampling and qualitative studies could be implemented to examine specific episodes of work–family conflict (Shockley & Allen, Reference Shockley and Allen2015), which can provide a more complete picture of how the pandemic crisis is affecting individuals’ day-to-day lives.

Individuals’ work–family challenges will depend on their unique situation (Agars & French, Reference Agars, French, Allen and Eby2016). During the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, scholars are encouraged to recruit nontraditional samples to better understand the struggles of underrepresented populations in work–family research. For instance, low-income workers are more likely to hold jobs where working from home is not an option (as well as other frontline workers, such as healthcare workers). As a result, these workers face additional stressors such as how to ensure their own and family members’ health and well-being given their increased exposure to the virus. Single parents, who already report higher levels of work–family conflict than do married parents in general (Byron, Reference Byron2005), now face even more daunting challenges managing work and family responsibilities during a pandemic crisis. Social capital—support from friends, family, or neighbors—has been identified as a critical resource for single parents (Freistadt & Strohschein, Reference Freistadt and Strohschein2013). Unfortunately, this resource may no longer be available to single parents because of physical distancing guidelines. These are just a few of the unique challenges facing underrepresented populations that deserve further study.

The COVID-19 pandemic crisis is a significant life event that has the potential to fundamentally shift a couple’s work–family dynamics. In what Lewis (Reference Lewis2020) calls “a disaster for feminism,” some scholars predict that couples will shift toward more traditional gender roles as a result of the pandemic crisis. Indeed, time-use data that have been collected from dual-earner couples has revealed such a shift, with gender disparities in men’s and women’s total workload emerging only after couples transitioned to parenthood (Yavorsky etal., Reference Yavorsky, Kamp Dush and Schoppe-Sullivan2015). Importantly, self-reported time spent on these activities did not reveal any significant differences, suggesting gender inequalities in shifting workloads may not even be apparent to the individuals. In light of these findings, organizational scholars should consider alternative methodologies such as time-use data to complement self-reports of work–family dynamics during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis.

There are several practical implications of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis for the work–family interface. At a national level, the COVID-19 pandemic crisis has exposed stark cross-cultural differences in paid family leave policies (see also Guan etal., Reference Guan, Deng and Zhou2020). For example, the United States is the only industrialized nation with no federal paid family leave policy. During this pandemic crisis, many workers (and, disproportionately, low-income workers) are completely reliant on their employer to offer paid leave in the event that they or a family member fall ill due to the virus (n.b., even with the passage of the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, millions of workers in the United States are still not eligible for paid leave). Cross-cultural analyses of the effectiveness of paid leave in facilitating family adaptation through the pandemic crisis can be used to advocate for additional policies to protect workers. Organizations can help reduce employees’ work–family conflict through fostering family-friendly culture norms and attitudes that are broad in scope (French etal., Reference French, Dumani, Allen and Shockley2018). Supervisors can advocate for additional tangible resources that can be used by employees to directly to mitigate stressors and strains (i.e., instrumental support). Both informal and formal forms of support may be particularly beneficial during this pandemic crisis, as research indicates that supports are most beneficial when employees’ needs are high. Finally, organizational and supervisor support interact with each other in that supervisor support is most effective when employees perceive their organization fosters a family-friendly culture (French & Shockley, Reference French and Shockley2020).

The COVID-19 outbreak may also provide the opportunity to examine how the crisis situation may result in positive work–family outcomes. The resilience literature has shown that it is possible for individuals to return to and sometimes exceed baseline levels of functioning after a crisis (Masten, Reference Masten2001). Individuals may learn new strategies for managing their work and family stressors, which they can maintain after the pandemic crisis is over. Couples may have a newfound understanding of each other’s work and family demands, and they may have learned new ways of effectively communicating with each other. If the couple is able to successfully navigate this pandemic crisis together, their marriage may come out stronger on the other end. For example, research on military families has shown that when families are able to “make meaning” of a deployment, they demonstrate improved capacity to deal with future challenges and greater family cohesion (MacDermid Wadsworth, Reference MacDermid Wadsworth2010; Riggs & Riggs, Reference Riggs and Riggs2011). Supervisors and key organizational decision makers may now have a more comprehensive understanding of the challenges of working parents, which can hopefully result in improved family-friendly policies. Finally, the increased time spent with children provides unique opportunities for greater involvement of children in family activities and fosters improved emotional connections between parents and children that may improve long-term family functioning.

3. Telecommuting

Telecommuting (also known as telework, flexplace, and remote work) is an alternative work arrangement where workers substitute at least some portion of their typical work hours to work away from a central workplace—often from home—using technology to interact with others and to complete work tasks (Allen etal., Reference Allen, Golden and Shockley2015; Gajendran & Harrison, Reference Gajendran and Harrison2007). Telecommuting began gaining traction in the United States in the 1970s (Avery & Zabel, Reference Avery and Zabel2001), and about 16% of the workforce in the US worked remotely in 2018 (BLS, 2019). If 2020 statistics were compared with those from previous years, we would see yet another COVID-19-related exponential curve. Exact figures are difficult to estimate at this point, but it seems that telecommuting is now almost ubiquitously being used as a means of physical distancing for jobs that are amenable to remote work. Thus, understanding evidence-based best practices for telecommuting has never been more relevant as it is during this pandemic crisis (see also Cho, Reference Cho2020; Kramer & Kramer, Reference Kramer and Kramer2020).

There is a substantial body of existing, interdisciplinary literature that is directed at understanding the link between telecommuting and individual and organizational outcomes. The bulk of this work is cross-sectional and compares remote workers with standard-arrangement workers, generally highlighting the basic association between type of work arrangement and outcomes such as productivity or job satisfaction (e.g., Allen etal., Reference Allen, Golden and Shockley2015; Gajendran & Harrison, Reference Gajendran and Harrison2007; Shockley, Reference Shockley2014). Meta-analytic findings generally suggest null or small differences between telecommuters and standard workers. The differences are typically favorable for the telecommuters, as they show slightly higher job satisfaction, supervisor- or objectively rated performance, and lower turnover intentions and role stress.

Despite this knowledge, the literature still lacks a more fine-grained view of how contextual factors that vary within different remote work arrangements relate to key outcomes. Examples of contextual factors include variables such as task interdependence, frequency and nature of communication, team cohesion, supervisor behaviors, knowledge sharing, and trust perceptions. Given that so many employees are working remotely during COVID-19 under such different working conditions in a variety of industries, the time is ripe to study these issues. Doing so will allow us to offer more evidence-based best practices to telecommuters and organizational stakeholders. However, it may be difficult for researchers to design and implement studies during this (hopefully) short period, but retrospective reports could also be quite useful, especially if drawing from objective organizational data (e.g., productivity records; communication records, etc.). Moreover, any attempts to draw conclusions about productivity at this time should certainly take into account family structure variables, given the closings of schools and daycares.

Beyond studying telecommuting arrangements during this pandemic crisis, researchers should consider the longer term effect that a compulsory large remote work force will have on future organizational perceptions regarding telecommuting. Employees cite that one of the main barriers to working remotely is an organizational culture that does not support it (e.g., Batt & Valcour, Reference Batt and Valcour2003; Brewer, Reference Brewer2000). This is especially true when organizations have a high face-time versus results-oriented culture and reward people for physical presence at work (Shockley & Allen, Reference Shockley and Allen2010). Speculatively, being forced into remote work arrangements may change the way executives view remote work and can serve as the “culture shock” that is needed to facilitate long-term cultural changes related to remote work. Researchers should examine the influence of these cultural changes on post-COVID telecommuter effectiveness and well-being.

Moreover, the intersection of work–family issues and telecommuting has been highlighted during the pandemic crisis. One particularly salient area concerns boundary-management preferences, which refer to people’s preferences regarding how they manage multiple life roles. Some people like to keep roles very segmented, not thinking about one role while in the other, whereas others do better when roles blend together and are integrated throughout the day (Ashforth etal., Reference Ashforth, Kreiner and Fugate2000). One known challenge of telecommuting is that it makes segmentation of work and family roles difficult, as both are taking place in the same location (Kossek etal., Reference Kossek, Lautsch and Eaton2006). For those with strong segmentation preferences, forced telecommuting is likely to create challenges in terms of increased role blurring and likewise perceptions of work–family conflict and difficulty detaching from work. As such, research that focuses on practical strategies to help remote workers preserve role segmentation would be quite useful. Some suggestions that have emerged from the literature and popular press include having a separate office with a door, coming up with an alternative “commute strategy” such as walking around the block to mentally separate the day, and getting fully ready for the day as you would if going into work. However, the extent to which these have actually been empirically tested varies, and it would be useful to have empirical information on the efficacy of these ideas.

Last, from a practical standpoint, one of the first best-practice recommendations given to new telecommuters is to make sure that telecommuting is not used as a form of childcare. Indeed, some organizations require telecommuters with children to sign a formal contract stating that they have alternative childcare arrangements. Clearly, COVID-19 has turned this idea on its head, with the closing of schools and other childcare facilities. There is no research, to our knowledge, on how employees can manage this situation. Although clearly pandemic crises are unusual circumstances, occasional working from home with childcare needs happens to most parents at some point due to frequent child illness. Research, perhaps starting with qualitative reports of parent’s “triumph” and “tribulation” stories during this time, could pave the way for a better understanding of the best practices for short-term handling of family responsibilities while working remotely in the future. Additionally, tying in with ideas in the work–life balance section, research that is directed at helping employees cope with this struggle would be useful. Specifically, many parents are not going to live up to their ideal performance in their parent and/or work roles during this trying period. Strategies such as practicing self-compassion toward work and family roles on a daily basis are beginning to gain research traction (e.g., Nicklin etal., Reference Nicklin, Seguin and Flaherty2019), and COVID-19 has made individual coping strategies even more relevant.

4. Virtual teamwork

The term “virtual teamwork,” a concept that is closely related to telecommuting, describes collaboration in (usually occupational) teams that is mediated by electronic tools and communication technologies (e.g., Hertel etal., Reference Hertel, Geister and Konradt2005; Maynard etal., Reference Maynard, Gilson, Jones Young, Vartiainen, Hertel, Stone, Johnson and Passmore2017). Although initially introduced as categorical concepts, virtuality is better considered as a dimension on which teams can vary, from face to face (low virtuality) to fully mediated (high virtuality, e.g., procurement teams with members working from different countries and time zones using online project management tools exclusively, such as web conferencing, cloud platforms for file sharing, and documentation of work progress). Given the widespread use of electronic communication media today, most occupational teams are working with some degree of virtuality (e.g., Landers, Reference Landers2019; Raghuram etal., Reference Raghuram, Hill, Gibbs and Maruping2019). Nevertheless, the level of virtuality has been shown to matter for team effectiveness and related processes, such as leadership, trust, well-being, and social exchange (e.g., Breuer etal., Reference Breuer, Hüffmeier and Hertel2016; Hoch & Kozlowski, Reference Hoch and Kozlowski2014; Maynard etal., Reference Maynard, Gilson, Jones Young, Vartiainen, Hertel, Stone, Johnson and Passmore2017). Notably, the construct of “virtuality” is complex and covers different dimensions, such as the degree of electronic mediation, synchronicity of communication, or geographic dispersion (e.g., Kirkman & Mathieu, Reference Kirkman and Mathieu2005). To understand virtuality effects, one has to consider these facets because they refer to partly different (psychological) processes in teams (see Hertel etal., Reference Hertel, Stone, Johnson, Passmore, Hertel, Stone, Johnson and Passmore2017 for a theoretical framework).

In general, virtual teamwork provides a number of benefits, including (but not confined to) an expanded expertise when team staffing is based on competencies instead of spatial copresence, high flexibility and empowerment of team members, rapid work processes due to the use of different time zones (i.e., “work around the clock”), close connections to suppliers or customers, and reduced expenses for traveling and office space, as well as support for regions with low infrastructure, integration of persons with low mobility, and reduction of commuting traffic and air pollution. At the same time, however, virtual teamwork also comes with certain risks, such as (perceived) social isolation, higher need for trust and more conflict potential, less control for team leaders, or slow feedback about team processes. Moreover, virtual teamwork is often associated with technological difficulties, causing extra time and daily hassles, higher self-organizing demands, and additional interference with private life (e.g., unplanned phone calls in the evening hours). As a consequence, virtual teamwork is not always attractive for workers, and companies have been hesitant to introduce virtual collaboration and likewise reticent to train team leaders and members in using technology appropriately.

The COVID-19 pandemic crisis is changing this situation. Virtual teamwork is receiving increased attention because it provides excellent solutions for physical (not social) distancing at work, the dominant strategy in most countries to flatten the infection curve and avoid breakdowns of public health systems. Indeed, whereas virtual teamwork has been blamed for leading to feelings of isolation and a lack of “team spirit” in the past, virtual collaboration in times of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis provides multiple ways to continue collaboration in a safe environment and offers additional opportunities to stay socially connected and to maintain a high team spirit despite spatial dispersion. This is facilitated by using regular video conferences with the whole team (e.g., morning briefings, virtual coffee breaks), continuous communication between individual team members (e.g., online chats), and constant updates on work progress (e.g., as part of advanced groupware tools). Interestingly, such additional tools might lead to even better processes in virtual than in face-to-face teams, for instance, because team meetings are better structured and team members receive more reliable information about the feeling states of the other members by using online feedback tools (e.g., Geister etal., Reference Geister, Konradt and Hertel2006).

Moreover, with the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, requests for (rapid) introduction and training of virtual teamwork has increased not only in “classic” work fields, such as research, sales, or procurement teams in larger organizations, but also in fields where computer-mediated collaboration is less established, for instance among school teachers, medical teams, mechanics, or in public administration. As a consequence, hands-on and easy-to use guidelines and support are urgently needed to manage these rapid shifts. Furthermore, being forced to switch to virtual teamwork—hopefully—also leads to some positive experiences and improved work processes (e.g., better prepared team meetings) that workers and organizations might want to maintain after the COVID-19 pandemic crisis (e.g., if only to be better prepared for a potential future pandemic crisis). Therefore, organizations and team leaders might want to prepare to collect lessons learned from the current changes for later implementation and maintenance.

In order to support these activities, more research is warranted to address the specific demands of virtual teamwork in a pandemic crisis. Particularly, there is a need more use(r)-inspired research, considering specific demands and difficulties in the current situation, for instance by using a critical-incidents approach (see Breuer etal., Reference Breuer, Hüffmeier, Hibben and Hertel2019) rather than merely reacting to the technological development of new “tools.” This research should specifically consider demands and needs when teams have to switch to virtual collaboration rapidly. Moreover, more differentiated approaches are needed that consider the dimensions of virtuality (synchronicity, geographical dispersion, mediated communication, etc.) separately to connect them with psychological processes (Hertel etal., Reference Hertel, Stone, Johnson, Passmore, Hertel, Stone, Johnson and Passmore2017). In the context of a pandemic crisis, virtuality aspects that allow physical distance but simultaneously increase feelings of social connectedness are particularly relevant, such as synchronous communication with visual information that also transmits nonverbal cues for trust maintenance and mutual support.

In addition to advanced video-conferencing tools, virtual-reality techniques might provide interesting opportunities to further increase the experience of connection, as well as that of perceived environmental control (e.g., Bailenson, Reference Bailenson2018; Guegan etal., Reference Guegan, Nelson and Lubart2017). In general, more research is desirable on social bonding in teams and on coping with fatigue and self-motivation problems, considering the higher needs for social support and feelings of security, as well as for structure and leadership in a pandemic crisis. Examples in this respect are gamification techniques (e.g., Suh etal., Reference Suh, Cheung, Ahuja and Wagner2017) or stressing the indispensability of the individual member for the team (e.g., Hertel etal., Reference Hertel, Konradt and Orlikowski2004; Hertel etal., Reference Hertel, Nohe, Wessolowski, Meltz, Pape, Fink and Hüffmeier2018). Moreover, information systems (e.g., automated documentation of task progress, simulations of different outcome opportunities) might further support virtual teams. In addition to the technical development, however, user experience and trust in such information systems are critical for a successful and rapid integration (e.g., Glikson & Woolley, Reference Glikson and Woolley2020; Thielsch etal., Reference Thielsch, Meeßen and Hertel2018), with concrete implications for a user-centric design. Finally, although virtual teamwork decreases infection risks in a pandemic crisis, it does increase the demands of specific resources such as the availability and support of suitable technologies, but also bandwidth and electricity demands, which might be scarce in a pandemic crisis. Therefore, we also need a better understanding of the efficient use of electronic collaboration media in a crisis situation for far-sighted planning and education programs.

Although research is still needed, specific recommendations for practitioners are possible based on what is already known (e.g., Maynard etal., Reference Maynard, Gilson, Jones Young, Vartiainen, Hertel, Stone, Johnson and Passmore2017; O’Duinn, Reference O’Duinn2018). First of all, if virtual teamwork is perceived as a desirable solution, organizations need to increase efforts to digitize their work processes, not only investing in appropriate hardware and software solutions but also adapting their work routines and providing appropriate training and ongoing support for virtual teams. Digitization of work has been a permanent and quite visible topic in human resource outlets for a while now; however, many (particularly small and midsize) organizations have not yet reached the full potential, probably due to the anticipated implementation costs and hassles mentioned earlier.

The current pandemic crisis, although coming with many humanitarian and economic costs, might be used as an opportunity to mobilize management as well as human resource departments and general staff to develop new forms of virtual teamwork, not only during the crisis situation but also beyond it. Lessons learned from the current situation might be an excellent starting point for creating a general digitization strategy that might include developing successful leadership concepts for virtual teamwork, designing resources for groupware solutions, or building technological infrastructure. Moreover, team leaders and members need competency training for using various media and technologies—for example, how to conduct an efficient and positively experienced web conference with larger teams, how to provide online feedback constructively, how to detect and manage conflicts in time, or how to develop and maintain trust and feelings of connectedness across physical distance. In addition, open exchange and knowledge management within but—if possible—also across companies and even businesses (e.g., what can telemedicine learn from sales or procurement teams) might be a promising avenue for innovation and learning. Virtual collaboration might help sharing (and finding) best practices for specific issues (e.g., virtual meeting rules) but can also help to develop new ideas to support (purposeful) work, which in turn can help in maintaining a healthy sense of agency and control for employees. Finally, the current crisis is also an opportunity to rethink what “really matters” in existing teams and for ongoing projects. In addition to emphasizing mutual support and maintaining high levels of team spirit, the purpose and effectiveness of the teamwork for the organization and beyond should be stressed, evaluated, and perhaps revised (McGregor & Doshi, Reference McGregor and Doshi2020).

In addition to such opportunities, a few risks should be mentioned. Although organizations ought to be open minded for new technologies to support their teams, they should not try to adopt every new trend. Instead, organizations are well advised to concentrate on the specific demands and needs of their teams as main criteria. Indeed, these demands can be quite different for various teams and organizations, for instance, due to different tasks, training backgrounds, or collaboration cultures. Therefore, empirical analyses of demands would be most desirable. Moreover, security and data-protection issues have to be considered, particularly when people work from home with Internet connections that have lower security standards. Finally, environmental issues have to be considered. Whereas telecommuting and virtual teamwork help to reduce commuting and business travel costs (including air pollution), the higher electricity demands of communication media with high bandwidth (e.g., video conferencing, team meetings with virtual reality applications) require well-considered and responsible usage, particularly in times of rapid changes when the infrastructure (e.g., server parks) still has to be adapted. Thus, team leaders and members also need to be educated about the environmental consequences of media applications in addition to the social and health implications.

5. Job insecurity

With the COVID-19 crisis expected to go on for months, many employers have turned to furloughing or laying off employees to stay afloat. A recent poll found that 33% of Americans surveyed reported that they or a family member have lost a job as a result of the pandemic crisis, and 51% report that they or a family member have had work hours or pay cut (Langer, Reference Langer2020). An even greater percentage of workers indicated they are concerned about potential job loss or cuts in hours or pay (58% and 53%, respectively), and 92% indicated that they see a recession as at least somewhat likely.

Clearly, there is a tremendous amount of job insecurity among those who are still employed. Job insecurity is defined as “a perceived threat to the continuity and stability of employment as it is currently experienced” (Shoss, Reference Shoss2017, p. 1914). Quantitative job insecurity captures the potential loss of one’s job as a whole, whereas qualitative job insecurity concerns the potential loss of valued job features and deterioration in working conditions (Hellgren etal., Reference Hellgren, Sverke and Isaksson1999; Vander Elst etal., Reference Vander Elst, Richter, Sverke, Näswall, De Cuyper and De Witte2014). The rise in job insecurity is problematic given that it has been linked to a host of short- and long-term negative outcomes for individuals, organizations, and communities (De Witte, Reference De Witte2016; Jiang & Lavaysse, Reference Jiang and Lavaysse2018; Shoss, Reference Shoss2017).

The COVID-19 pandemic crisis and associated economic consequences have ushered in experiences of job insecurity that are, in several key respects, fundamentally different from those that have been described in past research. In particular, job insecurity (more specifically, quantitative job insecurity) has always implied a permanent separation from the organization. This has been the case through the recessions of the 1980s and the Great Recession, as well as the widespread corporate downsizings and restructurings of the 1990s. However, given the unique nature of the current crisis, employees may expect/hope to return to work for their employer after the crisis. Thus, job insecurity, in many cases, may not reflect an anticipation of a permanent separation from the organization. Rather, it may reflect insecurity about a short(er)-term separation. This is a critical shift from the experiences of job insecurity that have been examined in past research, so it raises questions about the applicability of past findings in the current context. Moreover, it suggests that research on job insecurity needs to be expanded to incorporate and compare different types of job insecurity experiences and to examine how events surrounding insecurity (e.g., organizational communication) shape employees’ willingness to return to the employer and their behaviors/attitudes/cognitions upon return.

The crisis has also led to inherently different experiences of qualitative job insecurity. Medical professionals and first responders are experiencing considerable uncertainty about the future intensification of their work experiences and the sacrifices that will be required of them and their families as this crisis unfolds. Researchers would do well to examine these cases of qualitative job insecurity (perhaps an appropriate term would be intensification qualitative insecurity), to compare intensification qualitative job insecurity with more deprivation-focused experiences of qualitative job insecurity, and to examine the influence of intensification qualitative job insecurity on individuals, families, and workplaces in the short and long terms.

At the same time as these changes in the meaning and experience of job insecurity suggest new research that needs to be conducted, they also suggest several new directions and recommendations for practice (which should also be researched). First, people may view long-term quantitative job security as an (not ideal, but) acceptable substitute for short-term quantitative or deprivation-based qualitative job insecurity. For example, in anecdotal discussions with employees in a healthcare company that reduced work hours and pay due to the crisis, employees indicated that they would be willing to accept some uncertainty surrounding their job conditions as long as they know that they will have a job to which to return. Organizations may benefit from bolstering perceptions of long-term job security, even if they are unable to address short-term concerns.

Second, it is important that organizations operate with transparent and frequent communication and handle layoff/furlough situations with justice and sincerity. These conditions have been linked to lowered job insecurity and more positive responses from layoff victims and survivors (Jiang & Lavaysse, Reference Jiang and Lavaysse2018; Richter etal., Reference Richter, König, Koppermann and Schilling2016; Skarlicki etal., Reference Skarlicki, Barclay and Pugh2008). Managing these situations with the goals of reducing uncertainty and supporting well-being may help ensure that employees return and do so with positive views of the organization. This crisis, although gravely unfortunate, may represent an opportunity for organizations to demonstrate support for their employees that may pay dividends when this crisis passes.

Third, it may be beneficial for organizations to provide employees with a means by which to feel that they will remain part of the organization’s social fabric regardless of temporary furlough/layoff status (e.g., an employee Facebook group to share resources and support or shared opportunities for training). One of the reasons that job insecurity is thought to be so important is that it frustrates basic psychological needs (Vander Elst etal., Reference Vander Elst, Van den Broeck, De Witte and De Cuyper2012). Jobs provide identity, esteem, social connection, meaning, skill development, and so forth (Hulin, Reference Hulin, Brett and Drasgow2002). To extent that employers can enable employees to maintain these psychologically enriching experiences regardless of temporary job loss, they may help employees to cope with potential or actual loss and enable a more positive transition back to work.

Finally, if it all possible, organizations and governments should help employees manage economic uncertainty. Research suggests that economic uncertainty exacerbates negative reactions to job insecurity (Shoss, Reference Shoss2017). Many employers (e.g., Darden restaurants, Starbucks) have adopted or expanded paid sick leave policies (Jiang, Reference Jiang2020). This could not only help mitigate workers’ angst that either they go to work sick or lose their jobs and income but also help mitigate virus spread (Bhattarai & Whoriskey, Reference Bhattarai and Whoriskey2020; Stockton etal., Reference Stockton, Kastner and Appelbaum2020). Several employers have chosen to continue to pay employees despite closures (e.g., Apple; Disney), and others have continued to pay furloughed/laid-off employees’ health insurance to help employees manage the transition and reduce stress during this turbulent time. For those dealing with uncertainty that is related to intensification, organizational efforts to protect workers, support their families, and accommodate special needs may help assuage some of the negative effects of this uncertainty. As billionaire Mark Cuban was recently credited with saying (Stankiewicz, Reference Stankiewicz2020), “how companies treat workers during [this] pandemic could define their brand ‘for decades.’”

6. Precarious work

The COVID-19 crisis presents an opportunity to examine the quality and structure of work in the current labor market, particularly its implications for precarious work (see also Kantamneni, Reference Kantamneni2020). Precarious work broadly refers to work that is risky, uncertain, and unpredictable for workers (Kalleberg, Reference Kalleberg2009). Scholars have operationalized precarious work in different ways, mostly describing how the structure and quality of work is transforming in the modern labor market. For example, nonstandard, atypical, contingent, and alternative work arrangements all describe jobs that differ from full-time, permanent employment. Building from this work, scholars have defined precarious work more specifically as work that is unstable or short-term, lacks collective bargaining rights, provides low or unreliable wages, has few rights and protections, and does not grant workers power to exercise rights and freedoms (e.g., Benach etal., Reference Benach, Vives, Amable, Vanroelen, Tarafa and Muntaner2014). In this way, precarious work combines uncertainty in the amount and continuity of work with limited autonomy and access to power.

Across the globe, multiple forces are converging to make precarious work more prevalent (ILO, 2020). For example, since the 1980s, globalization and other factors have led to intense global competition and a subsequent reorganization of corporations to employ a smaller number of full-time, permanent workers and a greater number of part-time, temporary workers (Hall, Reference Hall2004; Katz & Krueger, Reference Katz and Krueger2019). In the United States, the percentage of workers in alternative work arrangements has increased 50% from 2000 to 2015, totaling 15% of the workforce (Katz & Krueger, Reference Katz and Krueger2019); these estimates are higher in other North American countries (i.e., Canada), in countries throughout Europe, and in Japan (see Cappelli & Keller Reference Cappelli and Keller2013). Estimates that include people in involuntary part-time work suggest that 20% of U.S. workers have alternative work arrangements (BLS, 2018) and millions of Americans earn poverty wages (Smith, Reference Smith2015). Moreover, precarious work is inequitably distributed, with marginalized populations being more likely to hold underpaid, insecure, and temporary positions (e.g., Kalleberg & Vallas, Reference Kalleberg, Vallas, Kalleberg and Vallas2017). This presents a significant concern for I-O psychologists given precarious work’s negative association with poorer job attitudes and mental health and its positive association with withdrawal intentions and turnover (e.g., Han etal., Reference Han, Chang, Won, Lee and Ham2017).

The COVID-19 pandemic crisis has exposed this precarity in the workforce and exacerbated existing issues with the contemporary structure of work. People in precarious work are particularly vulnerable to economic disruption and are less able to cope with unemployment and loss of working hours. For example, workers in precarious jobs, such as gig workers, temporary staffing agency workers, and hourly workers, are more likely to lose their jobs during the COVID-19 economic crisis (Blustein etal., Reference Blustein, Duffy, Ferreira, Cohen-Scali, Cinamon and Allan2020; JQI, 2020). Although many salaried workers are able to telecommute and continue their jobs, low-wage hourly workers and other precarious workers are not able to continue working during physical distancing and subsequently lose their employment. Decades of psychological research has established that unemployment has far reaching and deleterious results for individuals, including increasing depression and suicidality (Paul & Moser, Reference Paul and Moser2009). Moreover, the massive increase in unemployment after a short period of economic disruption highlights the underlying precarity of many workers’ job conditions, which existed before the current economic instability (Kalleberg, Reference Kalleberg2009). It also exposes inequity within the labor market whereby people with relative power and access to resources are more able to withstand crises.

Relatedly, many people with precarious work do not have access to governmental and organizational benefits, such as employment and health insurance. These benefits help people recover from crises as they struggle with finances and health problems. For example, precarious workers are at risk for chronic stress and dangerous working conditions, leading to higher rates of mental and physical health issues, such as cardiovascular disease (Benach etal., Reference Benach, Vives, Amable, Vanroelen, Tarafa and Muntaner2014; Schnall etal., Reference Schnall, Dobson and Landsbergis2016). These chronic health conditions in turn may increase vulnerability to COVID-19, as well as mental health concerns resulting from losses of resources and economic uncertainty (Zhou etal., Reference Zhou, Yu, Du, Fan, Liu, Liu, Xiang, Wang, Song, Gu, Guan, Wei, Li, Wu, Xu, Tu, Chen and Cao2020). In essence, the workers who are most vulnerable to the current crisis are those who are less able to cope with job loss and illness.

The COVID-19 crisis is an important opportunity to (re)focus I-O psychology’s efforts on addressing precarious work. The issue of precarious work is not new, but the current economic crisis highlights that large proportions of Americans are working in jobs that do not provide basic security or a living wage. Diverse fields including economics, sociology, and public health have studied precarious work and advanced theories in this area, but psychology has contributed less research to these efforts. However, psychologists have developed a literature base on aspects of precarious work, such as job insecurity and temporary workers, which can serve as a base for examining what the COVID-19 crisis reveals about the labor market and how psychologists can help. For example, the COVID-19 crisis raises important questions about who is vulnerable to economic crises, what factors exacerbate financial and mental distress, and what helps people cope with economic uncertainty and turmoil. For example, research suggests that precarious workers are particularly vulnerable to health and economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis (Benach etal., Reference Benach, Vives, Amable, Vanroelen, Tarafa and Muntaner2014; Schnall etal., Reference Schnall, Dobson and Landsbergis2016), and research is critically needed to understand the mechanisms involved and how to intervene effectively.

As people, organizations, and governments seek to endure and rebuild after the crisis, psychologists can play an important role in advocating for precarious workers and providing data that can inform interventions and relief efforts. Policies in the United States largely reflect the labor market of the 20th century, and employment insurance benefits are a key example. More than ever, Americans are working in alternative work arrangements and in the platform economy (Katz & Krueger, Reference Katz and Krueger2019), which cuts them off from traditional employment insurance and other benefits. Although the CARES act stimulus extends benefits to freelancers and independent contractors, this is a short-term solution to a long-term trend of people working outside the 20th-century model of employment (Hall, Reference Hall2004). As recovery occurs, psychologists can play a key role in advocating for governmental and organizational policies that reduce precarious work and increase social protections. These may include advocating for a living wage, increasing food and wage assistance, expanding Medicaid, eliminating work requirements, expanding unemployment benefits, improving the accessibility of job skills training, expanding the earned income and child tax credits, or prohibiting unemployment discrimination. Psychology has a wealth of data that can inform such policies (e.g., Smith, Reference Smith2015) and improve the lives of precarious workers during and after the COVID-19 crisis.

7. Leadership

According to Microsoft founder Bill Gates, “In any crisis, leaders have two equally important responsibilities: solve the immediate problem and keep it from happening again” (Gates, Reference Gates2020, p. 1677). Government attempts to simultaneously minimize deaths and economic decline due to the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as to mentally prepare people for the long and challenging aftermath of the current crisis and future pandemics, have led to increased feelings of uncertainty and psychological distress among many employees (Anderson etal., Reference Anderson, Heesterbeek, Klinkenberg and Hollingsworth2020; Sibley etal., Reference Sibley, Greaves, Satherley, Wilson, Overall, Lee, Milojev, Bulbulia, Osborne, Milfont, Houkamau, Duck, Vickers-Jones and Barlow2020). When perceived uncertainty is high, employees are more likely to turn toward their supervisors and leaders for guidance and support, and leader behavior has stronger effects on important employee and organizational outcomes (Waldman etal., Reference Waldman, Ramirez, House and Puranam2001). For instance, research conducted during a merger with high uncertainty has shown that follower-focused leader behavior is positively associated with follower organizational identification, psychological empowerment, and engagement (De Sousa & van Dierendonck, Reference De Sousa and van Dierendonck2014). Thus, the pandemic crisis may offer several opportunities for advancing leadership theory and research and for implementing evidence-based leadership practices.

Leadership broadly refers to the processes by which a person (i.e., the leader) influences others (i.e., followers) to achieve common goals (Yukl, Reference Yukl2006). In future leadership research, the COVID-19 pandemic crisis could be addressed by examining (a) how this context influences leadership, (b) who emerges as a leader in this context, and (c) what makes leaders effective in this context. First, scholars could examine whether the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, as a context factor, leads to changes in leadership behavior in teams, organizations, industries, and countries over time. Such research could attempt to constructively replicate a recent study based on the threat-rigidity hypothesis, which showed that the 2008 financial crisis led to an increase in directive leadership, particularly in the manufacturing sector and in countries with high power distance (Stoker etal., Reference Stoker, Garretsen and Soudis2019). It would be interesting to compare and explain the engagement in, and preference for, different leadership behaviors before and after COVID-19.

Second, scholars could further investigate who emerges, why, and when as a leader during this organizational, economic, and political crisis (James etal., Reference James, Wooten and Dushek2011). Research could focus on the role of individual differences for leadership emergence during the pandemic crisis. For instance, theorizing on the “glass cliff,” which suggests that women are more likely to be appointed to leadership positions in crises than men because they signal “change” (Ryan etal., Reference Ryan, Haslam, Morgenroth, Rink, Stoker and Peters2016), could be tested in the context of COVID-19. Similarly, studies could investigate whether older, more experienced leaders (Spisak, Reference Spisak2012) and leaders that use more promotion-oriented communication (Stam etal., Reference Stam, van Knippenberg, Wisse and Nederveen Pieterse2018) are preferred not only during war and organizational crises but also during the current pandemic crisis. In addition, research could focus on the dynamic, interactive, and multilevel nature of leadership emergence during the pandemic crisis, including followers’ individual, relational, and collective cognitive and perceptual processes regarding leadership (Acton etal., Reference Acton, Foti, Lord and Gladfelter2019). Observational studies on leadership emergence during the pandemic crisis could further examine what individuals who emerge as leaders during the crisis actually “do” (and why and when they do it), including behaviors such as listening as well as task-, relationship-, and change-oriented communication (Gerpott etal., Reference Gerpott, Lehmann-Willenbrock, Voelpel and Van Vugt2019).

Third, scholars could examine the individual and contextual factors and processes that predict leadership effectiveness during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. Previous research in this area has identified various “leadership competencies” that are required in distinct crisis phases that could also be examined in the current crisis. For instance, leaders have been advised to engage in sense making and perspective taking in the “signal detection phase”; in issue selling and creativity in the “prevention and preparation phase”; and in decision making, communication, and risk taking during the “damage control and containment phase,” before entering the “recovery phase” and the “learning and reflection phase” (Wooten & James, Reference Wooten and James2008). Building on this research, it would be important to theorize on and examine specific leader behaviors that address the unique demands of the current pandemic crisis. Such research would have to start with a systematic analysis of the various new task, relational, and cognitive demands faced by leaders in this crisis. For instance, the COVID-19 pandemic crisis urgently calls for examining research questions on the notion of “digital leadership” (sometimes also called e-leadership or virtual leadership), as many leaders and their followers are now forced to work remotely from home (Larson & DeChurch, Reference Larson and DeChurch2020; see also the sections on virtual teams and telecommuting). In this context, follower perceptions of leader communication, trust, justice, and granted autonomy seem particularly relevant.

The COVID-19 pandemic crisis may also require leaders to manage a paradox between employee health and well-being on one hand and maintaining or restoring profitability on the other. Thus, researchers could test whether “paradoxical leadership” is particularly effective in the current crisis (Zhang etal., Reference Zhang, Waldman, Han and Li2015). In addition, social psychologists have recently offered “identity leadership” as a new and potentially effective form of leadership in the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, which involves leaders representing and promoting the shared interests of their followers as well as creating a sense of collective social identity among them (Haslam etal., Reference Haslam, Reicher and Platow2011; Van Bavel etal., Reference Van Bavel, Baicker, Boggio, Capraro, Cichocka, Cikara, Crockett, Crum, Douglas, Druckman, Drury, Dube, Ellemers, Finkel, Fowler, Gelfand, Han, Haslam, Jetten and Willer2020). Finally, research on the notion of “healthy leadership” could explore associations among leaders’ and followers’ health-related attitudes, values, behaviors, and outcomes during a stressful and uncertain time that places various novel demands and constraints upon them, both within and outside of the work context (e.g., job insecurity, work–family conflict; Rudolph etal., Reference Rudolph, Murphy and Zacher2019).

Importantly, scholars who study leadership with a particular focus on the COVID-19 pandemic crisis should theoretically justify why a leadership construct or process is assumed to have different (or the same) effects during a specific period or a country/region that is strongly influenced by the pandemic crisis, as compared with other (previous or future) periods or countries/regions. Moreover, when introducing any new leadership construct, it is important to demonstrate incremental effects beyond those of already established leadership constructs, such as task-, relational-, and change-oriented forms of leader behavior (DeRue etal., Reference DeRue, Nahrgang, Wellman and Humphrey2011). We particularly caution against the introduction of a novel “COVID-19 pandemic crisis leadership behavior” construct, as it is likely to have a great deal of conceptual and empirical overlap with existing, well-established leadership constructs (e.g., initiating structure, consideration, charismatic leadership style; Stam etal., Reference Stam, van Knippenberg, Wisse and Nederveen Pieterse2018). Thus, it would not explain a significant amount of additional variance in important follower and work outcomes (see also Rudolph etal., Reference Rudolph, Murphy and Zacher2019).

In addition to research opportunities, it is important to discuss evidence-based practical implications for leadership in the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. First, organizations should select leaders who possess the relevant knowledge, skills, and personality characteristics to successfully navigate the unique demands of a crisis, such as the current pandemic (e.g., recognition of and dealing with specific threats and opportunities for employees and the organization; Wooten & James, Reference Wooten and James2008). Second, as many leaders do not received formal training to manage crises, it is important to integrate crisis management knowledge and skills into future leadership development programs and learn from errors made during earlier crises (Day & Dragoni, Reference Day and Dragoni2015).

Third, leaders should be encouraged to take care of both their and their followers’ health while maintaining high performance. For instance, research suggests that high levels of leader presenteeism (i.e., working despite being ill) can spill over and increase employee presenteeism, which subsequently leads to higher employee sick leave (Dietz etal., Reference Dietz, Zacher, Scheel, Otto and Rigotti2020). Finally, due to several problematic issues with the notion of “generations” and “generational differences” (Rudolph, Rauvola, & Zacher, Reference Rudolph, Rauvola and Zacher2018), it is advisable that leaders do not attempt to manage an assumed “COVID-19 generation” (see Rudolph, & Zacher, Reference Rudolph and Zacher2020a) but rather adopt an individual-focused life-span perspective on their followers’ development, performance, and well-being (see also the section on the aging workforce).

8. Human resources policy

The evolving COVID-19 pandemic crisis has put pressure and demands on human resource (HR) departments and managers to quickly adjust their policies and practices. Human resources responsibilities in organizations consist of both traditional or operational and strategic tasks (Wright & Ulrich, Reference Wright and Ulrich2017). The current crisis requires actions on the operational side of HR practices but at the same time has potential for strategic HR initiatives that might help organizations get “back to business” as soon as possible after the crisis.

On the operational side of HR management, health and hygiene measures for all employees are the top priority for most employers right now. As COVID-19 is a virus that spreads between human beings, physical distancing is critical to lowering infection rates between employees and keeping operations running. Measures to achieve physical distancing differ between white-collar or office employees and blue-collar or production employees. White-collar employees can relatively easily move to home office settings and communicate virtually to complete their work tasks. Human resources departments, in cooperation with information technology (IT) divisions, have to ensure that employees have the right IT equipment and competencies to work remotely. Short video or blended-learning opportunities, for example, explaining how to host video conferences and keep up team-based collaborations in virtual settings, might be particularly helpful for employees who have limited experience with working remotely (see also the sections on telecommuting and virtual teamwork).

Furthermore, many employees are confronted with childcare obligations due to closed schools and kindergartens. As a consequence, HR departments have to tailor idiosyncratic deals (I-deals) for these employees, including negotiating specific time and work arrangements that fit their current situation (Rousseau etal., Reference Rousseau, Ho and Greenberg2006). For flexible and telecommuting arrangements, I-deals have been shown to lower work–family conflict and increase the work engagement of telecommuting employees (Hornung etal., Reference Hornung, Rousseau and Glaser2008), as well to improve contextual work performance (Gajendran etal., Reference Gajendran, Harrison and Delaney-Klinger2015). As a consequence, HR departments should allow as much leeway as possible in terms of work and time arrangements for white-collar employees in the current situation (see also Spurk & Straub, Reference Spurk and Straub2020).