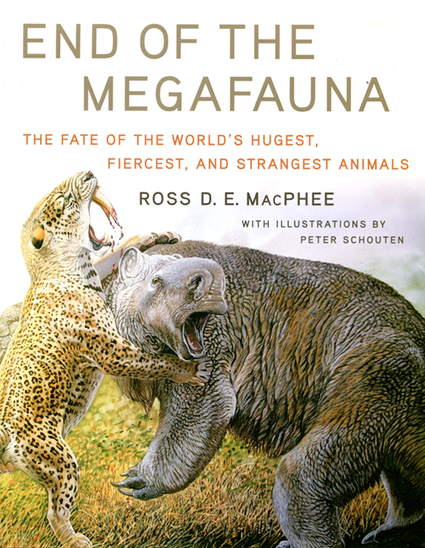

This volume is the combination of a scholarly source (for a broad audience, including high-school pupils, undergraduate and graduate students, people with a college degree, and the general public) and a coffee-table book, rich with illustrations. Because of this, it is impossible to judge it as a purely academic publication; nevertheless, its importance in terms of publicizing Quaternary studies for a wide readership is beyond doubt. In this overview, I would like to concentrate on the scholarly aspects of this book; another review has recently been published (Yule and McGarren Flack Reference Yule and McGarren Flack2019).

This book is a useful addition to edited volumes published in the last 35 years (Martin and Klein Reference Martin and Klein1984; MacPhee Reference MacPhee1999; Haynes Reference Haynes2009). The main subject of MacPhee’s (Reference MacPhee2019) book is the assessment of different concepts related to the Late Quaternary extinctions in the last 50,000 years or so, with particular focus on Paul S. Martin’s “overkill” hypothesis put forward in the 1960s–1970s (e.g. Martin Reference Martin1973). Most of Martin’s ideas finally published in Reference Martin2005 (see Martin Reference Martin2005) have been reviewed previously (Kuzmin and Tikhonov Reference Kuzmin and Tikhonov2007).

Ross D.E. MacPhee stated that “Accurate and plentiful dating is an essential for understanding any extinction event …” (p. 128). This is completely true, and during the last 25+ years significant progress has been achieved in this field (e.g. Stuart Reference Stuart1991, Reference Stuart2015; Kuzmin Reference Kuzmin2010). The radiocarbon (14C) method is most commonly employed for dating the remains of megafauna, with an age limit of ca. 50,000–55,000 years (Taylor and Bar-Yosef Reference Taylor and Bar-Yosef2014). As for the range of luminescent dating beging ca. 1,000,000 years (p. 192), MacPhee seems to be too optimistic. According to the most acceptable sources (e.g. Walker Reference Walker2005), any luminescent technique can give reliable ages up to ca. 300,000–500,000 years.

There are two major kinds of hypotheses on Late Quaternary extinctions: a) driven by global climate changes; and b) related to human impact on ecosystems (“overkill” sensu Martin Reference Martin1973). Regardless of what caused the disappearance of the animals, the losses were quite large, estimated to be 750 to 1000 vertebrate species heavier than ca. 45 kg (p. 24). MacPhee does not support the “overkill” hypothesis, and he pointed out to several facts which do not fit with it. For example, he stated: “… there were no identifiable periods of concentrated megafaunal extinctions in the Old World during the expansion of premodern or non-sapiens humans” (p. 48). From the north Eurasian (mainly Siberian) perspective, “overkill” as a main cause of extinction is unlikely (e.g. Kuzmin Reference Kuzmin2011; see also MacPhee Reference MacPhee2019: 182). For example, mammoths and humans coexisted in the Yenisei River basin for several millennia, without disappearance of the former. All large accumulations of mammoth bones and tusks (so-called “mammoth cemeteries”) in Siberia don’t have any traces of active participation of humans in the creation of them (e.g. Nikolskiy et al. Reference Nikolskiy, Sulerzhitsky and Pitulko2011). Even for North America, the primary ground of “overkill” sensu Martin (Reference Martin1973), there is no unequivocal data on the devastating effect of human hunting on mammal communities (e.g. Alroy Reference Alroy2001, but see Fiedel Reference Fiedel and Haynes2009). According to the latest analysis, both climate and humans contributed to the megafaunal extinction on this continent (Broughton and Wietzel Reference Broughton and Wietzel2018).

MacPhee correctly points out doubtful sites in the Americas which have pre-Clovis age (pp. 52–53): Monte Verde (South America) dated to ca. 14,500–18,500 years ago (i.e. cal BP), and Cerutti (North America) with even greater age of ca. 130,000 years ago. On the other hand, some data from South America may testify about the contribution of Paleoindian hunters to the extinction of large mammals but their impact was not devastating. For example, the dung of ground sloth (Mylodon darwini) in the Mylodon Cave (Patagonia) was directly 14C-dated to 12,240 ± 80 BP (AA-59601). This can testify that ground sloths in this region went extinct prior to the Holocene, contra to some scholars (e.g. Saxon Reference Saxon1979), with no or very little human participation in this process.

One of the weak points in the Martin’s “overkill” hypothesis is this: when people supposedly wiped out the megafauna in North America, why didn’t human population size drop because the food resources significantly decreased? The simulations of population size for Paleoindian cultural complexes—Clovis and Folsom—show that the number of humans was steadily increasing or quickly recovering (see Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Goodyear, Kennett and West2011) despite the disappearance of megafauna. The concept of Late Paleolithic mammoth hunters originated at least 100 years ago, and it still exists despite the fact that direct evidence of hunting the woolly mammoths is extremely scanty. For the entire northern Eurasia, there are a few cases when remains of throwing weapons were found embedded in mammoth bones—at Kostenki in the central Russian Plain (Eastern Europe) (Sinitsyn et al. Reference Sinitsyn, Stepanova and Petrova2019), Lugovskoe in Western Siberia (Zenin et al. Reference Zenin, Leshchinsky, Zolotarev, Grootes and Nadeau2006), and Yana RHS in Northeastern Siberia (Nikolskiy and Pitulko Reference Nikolskiy and Pitulko2013). Numerous finds of mammoth bones with traces of human modification (see review: Agam and Barkai Reference Agam and Barkai2018) are not convincing because the scavenging and use of mammoth bones and tusks is well known (e.g. Kuzmin Reference Kuzmin2019: 1064).

Climate impact also cannot explain the extinction phenomenon, mainly because of the heterochronous nature of mammal disappearance in different parts of the world. Some other extinction hypotheses—hyperdisease and impact of a comet or asteroid—are also considered (pp. 168–175) but none of them was found convincing.

There are some disputable and/or controversial issues in MacPhee’s (Reference MacPhee2019) book which need to be discussed. As for the landscapes existing during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), ca. 27,300–22,900 years ago, MacPhee believes that “virtually all of northern Eurasia was occupied by either extreme polar desert or treeless steppe” (p. 32). This does not correspond to the latest reconstructions of the LGM vegetation in Siberia (e.g. Kuzmin Reference Kuzmin2008; Kuzmin and Keates Reference Kuzmin and Keates2018) where the existence of trees is noted.

The presence of “advanced hominins” (mainly anatomically modern humans, Homo sapiens sapiens) in insular Southeast Asia at ca. 120,000 years ago (p. 48) is an overestimate; the latest data (Westaway et al. Reference Westaway, Louys, Due Awe, Morwood, Price, Zhao, Aubert, Joannes-Boyau, Smith, Skinner, Compton, Bailey, van den Bergh, de Vos, Pike, Stringer, Saptomo, Rizal, Zaim, Santoso, Trihascaryo, Kinsley and Sulistyanto2017) give us an age of ca. 68,000 years. As for the presence of humans in “northernmost Siberia by at least 45,000 years ago” (p. 50), this is based on indirect data taken from the find of mammoth with traces of butchering (Pitulko et al. Reference Pitulko, Tikhonov, Pavlova, Nikolskiy, Kuper and Polozov2016). More reliable information exists for the Yana RHS site (71°N) which is dated to ca. 32,000 years ago (e.g. Pitulko and Pavlova Reference Pitul’ko and Pavlova2016).

One of the hottest subjects in this book is the megafaunal extinction in Australia and possible role of humans in it (see discussion: Wroe et al Reference Wroe, Field, Archer, Grayson, Price, Louys, Faith, Webb, Davidson and Mooney2013; Brook et al. Reference Brook, Bradshaw, Cooper, Johnson, Worthy, Bird, Gillespie and Roberts2013). The proposed age for the initial peopling of Australia, ca. 65,000 years ago (p. 49), in my opinion is too old. The recent critical analysis of evidence (O’Connell et al. Reference O’Connell, Allen, Williams, Williams, Turney, Spooner, Kamminga, Brown and Cooper2018) shows that today the most reliable and conservative date for the arrival of modern humans to greater Australia is ca. 45,000–50,000 years.

Overall, the book by MacPhee (Reference MacPhee2019) is a valuable source of new (and sometimes not so new) information about one of the most intriguing subjects in modern Quaternary studies, and it would be useful to a wide audience. The author should be praised for putting it together, and also for supplementing it with fascinating illustrations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful to my colleagues at the Radiocarbon—Editor A.J. Timothy Jull and Managing Editor Kimberley T. Elliott—for the opportunity to prepare this review. Preparation of this review was also supported by the Tomsk State University Competitiveness Improvement Program.