Introduction

Our aim in this article was to evaluate and provide an overview of characteristics that are specific to the presidentialization of party politics. To do so, we use the countries of Central Europe, and show that the trend towards presidentialization has been gaining momentum, with an impact on both long-established, traditional parties and those more recently established. The article is structured to correspond to this objective. First, the concept of presidentialization is outlined. This is followed by a discussion of other concepts related to the centralization of power and decision-making systems within political parties in Central and Eastern Europe. The sections to follow provide a step-wise analysis of presidentialization, with a primary focus on party leadership. In addition, attention is given to electoral politics and, in the final discussion, to governmental politics as well.

Presidentialization as a trend in European politics

Presidentialization as a concept is a significant analytical tool for use in describing a trend that has seen the importance and power of leaders grow in contemporary party politics. Presidentialization sees this trend not as an outgrowth of changes to the constitutional and legal framework, nor to the electoral system, but rather as the result of informal re-inforcement of the role played by leaders under the existing set of rules. The classic definition, put forth by Poguntke and Webb (Reference Rybář2007: 1), places the emphasis on the fact that ‘presidentialization denominates a process by which regimes are becoming more presidential in their actual practice without, in most cases, changing their formal structure, that is, their regime type’. Empirically, under the presidentialization process, the role of the leader, the head of the executive – in most European countries, the prime minister – is re-inforced in three areas: power resources, leadership autonomy,Footnote 1 and the electoral process (Poguntke and Webb, Reference Rybář2007: 5).

Our chief interest is in party politics, and here presidentialization involves a focus on re-inforcing leader autonomy (the party politics sphere). Also of interest is the role played by leaders in election campaigns and in devising political party strategies (the electoral sphere), as well as on re-inforcing the role played by party leaders in the governmental sphere under Sartori’s model of parliamentarism, in which the prime minister plays an important role (Sartori, 1994).Footnote 2

In the presidentialization process, party leaders concentrate power, media attention, and decision making in their own person, at the expense of parties as collective actors, which aggregate the interests of the membership base. This dampens the party’s influence, in an environment in which the importance of political marketing is growing, as is the professionalization and personalization (i.e. the ‘Americanization’) of election campaigns.Footnote 3 The result is that party politics must, thus, be seen in a context in which cartel-type political party organizations prevail (Katz and Mair, Reference Kopeček1995; Kopecký, Reference Krašovec and Deželan1995; Detterbeck, Reference Enyedi and Linek2005), along with emerging ‘entrepreneurial issue parties’ (Harmel and Svåsand, Reference Haughton, Novotná and Deegan-Krause1993). In both cases, there is pressure to push the role played by the membership base into the background and concentrate party decision making in the hands of a restricted group around the leader.

The concept of presidentialization of political parties and the characteristics of Central Europe

This concept originally grew out of a combination of theory and the empirical observation of party development in Western Europe, but it can, in our opinion, be used to analyse the parties and party systems of Central and Eastern Europe with great effect. A number of factors that have played a leading role in the presidentialization of politics in Western Europe are having an even stronger impact in Central and Eastern Europe; they include influences traceable directly to party functioning of party competition, such as the weak anchoring of cleavages and the relatively low stability of party competition paradigms, along with the low levels of party institutionalization and resulting greater electoral volatility, the predominance of cartel parties, and the origin and evolution of parties whose structures model commercial enterprises (business firm parties).

In addition, influences that are external to the party politics environment in Central and Eastern Europe must be taken into account. These include the re-inforcement of political elites as the result of Europeanization and internationalization (see footnote 3) and the fact that the environment within which party politics operates is undergoing change in the form of new styles of political communication being used, the professionalization and centralization of campaign management, the increased application of political marketing, and public demand for strong leadership.

Let us begin with the issue of the stability of party competition and the stability of the alignment between the electorate and parties. Owing to the Communist regimes in place, no marked social cleavages in the countries of Central Europe similar to those that were formative for Western European party politics in the late 19th and early 20th centuries ever developed. The tradition of democratic politics in these countries was already weak before the Communists took power (see Cabada et al., Reference Detterbek2014: 11–42). During the post-communist transition to democracy, new cleavages were formed, but they were fairly political in nature, not a reflection of social cleavages, but the outcome of long-term exposure to the principal themes of political parties to which segments of the electorate only gradually formed ties (see Hloušek and Kopeček, Reference Katz and Mair2008: 519–526; Rohrschneider and Whitefield, 2009: 281–287). Political cleavages, however, do not create particularly strong alignments between the electorate and parties, and ultimately heighten not only volatility but also the potential for politics to be personalized, thus re-inforcing the role of strong leaders.

In terms of their internal structure and the extent to which they have become established within the political system, in general, political parties have been institutionalized to a weaker degree in Central Europe compared with their counterparts in the West. As Bielasiak (Reference Bielasiak2002) reminds us, the relatively low degree of institutionalization is related to the transition towards democracy as such and the gradual establishment of political systems and, particularly, electoral systems. As a result, there is high volatility (for empirical data, see Cabada et al., Reference Detterbek2014: 115–120) and a greater probability of electoral ‘earthquakes’ (Czech Republic 2010 and 2013, Poland 2001, Hungary 2010, Slovenia 2011 and 2014). Older parties, more established as collective actors, have had to make way for newer political actors, a process that has usually entailed voters punishing the parties in power and clearing the way for new, very frequently populist protest parties, as well as parties with a high degree of personalization (Haughton and Deegan-Krause, Reference Havlík2015: 74–75).Footnote 4

Another factor indispensable for the re-inforcement of presidentialized party politics lies in the tendency of established Central European parties to organize as cartel parties. In our area of research, one factor in the cartelization of political party functioning is the practically exclusive dependence parties have on state funding, at least those that are not entrepreneurial parties (Kopecký, Reference Krašovec and Haughton2006: 260–263). Another factor is the traditionally weak member base of political parties (van Biezen et al., 2012: 32), which has dwindled further over time, and the professionalization and ‘oligarchization’ of party functioning, now in the hands of a narrow elite. As van Biezen (Reference Cabada2003: 167) has noted ‘the overlap between the parliamentary group and the party executive is so considerable that it sometimes becomes difficult, if not impossible, to distinguish between the different faces of the party organization’. To that, we may add that the differentiation of party elites from the executive elite is similarly difficult within Central European Parliamentary democracies. The inter-connection of the party elite and public office holders increases their role in the functioning of the party (van Biezen and Kopecký, Reference Cabada, Hloušek and Jurek2014: 176–179). In what follows, we assess the extent to which plurality persists within this narrow elite, and whether there are observable elements of presidentialization in internal party politics.

There has recently been an increase in the number of entrepreneurial issue parties in Central European countries (Harmel and Svåsand, Reference Haughton, Novotná and Deegan-Krause1993). Arter (Reference Arter2013: 3) described such a party as being ‘formed by one person who does not hold a position in government. It must have external origins, represent the work of a single entrepreneur and will be closely associated with an issue prioritized by the founder of the “party enterprise”’.Footnote 5 Logically, in a party thus created, the role played by the leader is of enormous importance and its success, particularly if it involves success in the elections or participation in a coalition government, heightens the degree of presidentialization in that particular party.

Contemporary political communication trends also support the concentration of political power in the hands of leaders. This is chiefly due to the centralization and professionalization of election campaigns, which in this current era of television and the internet may be conducted in an ‘Americanized’ style that utilizes hired consultants, focussed on mobilizing voters nationwide and personalizing the election contest.Footnote 6 This style of campaigning took root quickly in Central and Eastern Europe after the fall of communism (Plasser and Plasser, Reference Poguntke and Webb2002), re-inforcing the communication role of party leaders. In some Central European countries, the ownership structure of national and/or regional media must be taken into account. So called media moguls, who combine ownership of important media outlets with direct or indirect engagement in politics, are characteristic of Bulgaria, Romania, and Latvia (Örnebring, Reference Poguntke2012: 505), but they are also present in Central Europe. Discounting Pavol Rusko and ANO in Slovakia in 2002–06 (Kopeček, Reference Kopecký2006), most significant concentration of media and political power is in the hands of Andrej Babiš in the Czech Republic and the focussed effort to influence state media by Orbán in Hungary. Another significant element is the personalization of campaigns. However, as Webb and Poguntke (Reference Webb and Poguntke2013: 650–651) note, this only involves personalization to the extent that the campaign is built around the party leaders.

Two paths to presidentialization: operationalization of the concept to researching Central European parties

The analysis below dissects the statutes and secondary literature to empirically follow presidentialization in five Central European countries, and attempts to demonstrate that presidentialization is a growing contemporary trend, but one with historical roots.

Our focus is on the role played by re-inforcing party leaders within political parties. A look at parties in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia shows that, in terms of origin and development, there are two types of political parties: (1) those that came into being in the early phase of the democratic transformation and whose organizational structure has undergone a rather long period of consolidation, and (2) new parties that have come into being in reaction to political crises involving the established parties, and which may and in fact logically experiment with their organizational setups. Table 1 provides an overview of these types of parties after 2010.

Table 1 Relevant ‘traditional’ and ‘new’ parties in Central Europe since 2010

Compiled by the author (date of foundation or renewal of the party in the brackets).

Presidentialization of the organizational structure is a highly attractive option, particularly for the newly originated parties. However, a tendency to re-inforce the party leader is also found in some parties that might be designated as ‘traditional’ in Central Europe, and in some cases such re-inforcement took place even before the period on which this analysis focusses. The explanation that follows will, therefore, focus on two subtypes of presidentialization, the first being presidentialization as an innovation strategy in traditional parties undergoing the process in a gradual manner, and the second being presidentialization as the basis of an organization, something that is seen in parties whose organization is structured in a presidentialized manner from the outset.

Presidentialization as an innovation strategy: from collective leadership to strong leaders

Strong leaders may be expected for extreme right-wing parties, and Central European extreme-right entities successful in the first decade after the fall of communism were indeed led by strong men (Miroslav Sládek in SPR-RSČ, István Csurka in MIÉP,Footnote 7 Ján Slota in the Slovak SNS, and Zmago Jelinčič in the Slovenian SNS). These parties were formed during the first phase of the democratic transition process, and sometimes emerged from historical predecessors. The influence of their chairmen was felt not only in election campaigns, or in the parties’ depiction in the media, but also in the chairmen’s influence on party operations and the formulation of party ideology. These parties’ success in elections often rose and fell with that of their leaders.Footnote 8

The mainstream parties of the Central European moderate right and the moderate left were characterized by a rather more collective manner of leadership in which the party chairman was balanced by other significant political personalities at the helm of the party. Despite the significant role played by the ‘party faces’, these mostly highly professionalized, rather pragmatic, leaders did not usually follow a strategy of strongly re-inforcing their power within their parties and their informal position within the party elite. Attempts made by Jiří Paroubek (ČSSD), Leszek Miller (SLD), and Ferenc Gyurcsányi (MSzP) to centralize, streamline, and Americanize party operations encountered resistance from the member base and national and regional party elites (Tavits, 2013: 167–171 and 177–188). In their effort to convert the rapid professionalization of election campaigns into practical politics, the parties both encountered financial restrictions and grappled with insufficient numbers of party members to do the work. The strong personalization of election campaigns that took place in the Czech Republic and Hungary in 2006 due to massive political marketing was characterized by elections being conceived as contests between the two strongest parties (ČSSD vs. ODS and MSzP vs. Fidesz), personified by their leaders and by a combination of unachievable promises and negative campaigning (Čaloud et al., Reference Enyedi2006: 42–88; Dieringer, 2009: 135–140). The sobering-up period after the election was difficult, as testified to by the following statement from Gyurcsány: ‘I almost perished because I had to pretend for 18 months that we were governing. Instead, we lied morning, noon and night’ (BBC, 2006). In these cases, the tendency for presidentialization was evident only on a temporary basis, conditioned by an ambitious leader with whose electoral failure it terminated.

However, even with mainstream parties to the right of the political centre, we must differentiate the situation of a visible leader who continues to be limited by the power distribution within the broader party elite from that of a real attempt at presidentialization in the party leadership. This tendency to a visible but not ‘omnipotent’ leader was demonstrated over the long term by parties in Hungary, Poland, and the Czech Republic (e.g. ODS at the time of Václav Klaus and partially of Mirek Topolánek or KDU-ČSL under Josef Lux and Miroslav Kalousek).Footnote 9 As we show in what follows, the shift towards a truly presidentialized leadership model took place only in the case of Orbán’s Fidesz, the Polish PiS and Slovenian SDS lead by Janez Janša. With PO, led by Donald Tusk, this tendency was weaker, limited by the period of time from when Tusk was selected as party head (2003), and when he left to become President of the European Council (2014). Tusk’s formal and informal positions were weaker vs. PiS (Sobolewska-Myślik et al., Reference Szczerbiak2010: 143–144), and the presidentialization of PO, thus, took place rather in the electoral sphere and that of governmental politics.

Orbán assumed the position of de facto party leader when Fidesz was founded by a group of friends and student activists as an alternative political movement (Tavits, 2013: 178). In spite of this, from the outset, Fidesz’s leadership functioned like a collective body. The transformation to a significantly centralized, personalized power distribution occurred only when Fidesz was converted from a youth movement into a political party in the mid 1990s. Orbán’s personal leadership gained significance during that era (Enyedy and Linek, Reference Gałązka and Waszak2008: 468), even in areas to do with the selection of candidates for parliamentary elections. The fact that Orbán has had no rival for the position of party chairman since 1994 is one sign that leadership is more centralized in Fidesz than in other traditional Hungarian parties (Enyedy, Reference Flacco2006: 1111; Dieringer, 2009: 88). Orbán’s strong position as party head was naturally reflected in the election campaigns of 2010 (Batory, Reference Batory2010: 4–5) and 2014 (Mudde, Reference Örnebring2014). However, the stunning result for the party in the 2014 elections in terms of seats obtained in the parliament must be seen as the product of an artificially created majority, one that arose from a new electoral system that ensured Orbán would gain two-thirds of those seats for a mere 44.5% of votes cast.

In Slovenia, SDS underwent a somewhat different transformation process between 1993 and 1995. Janez Janša, a charismatic politician, was elected head of the party, and transformed it from a social-democratic orientation towards one of conservatism with strong populist features. He re-inforced his informal power within the party structure and gradually presidentialized the party’s management style (Cabada, Reference Carter, Luther and Poguntke2000: 80). For Slovenia, the tendency to manage parties via a small circle of elites and a liking for the cartel party model is characteristic (Krašovec and Haughton, Reference Ladrech2011: 202), but only with SDS may we speak of a trend towards an informally presidentialized party structure established over a long period. Janša’s personality has also figured significantly in the party’s election campaigns, particularly in 2011, when he showed himself to be a figure with a highly personalized style of party management that polarized the Slovenian public, with the result that issues related to his own political and economic actions overshadowed the party’s platform message (Haughton and Krašovec, Reference Havlík2013: 202).

In Slovakia, there has been a strong tendency towards personalization, particularly involving the presidentialization of HZDS, led by the charismatic Vladimir Mečiar. Mečiar built a successful party with a mass membership base that functions with a combination of charismatic leadership and patron–client practices. The party was formally organized as a movement based upon Public Against Violence, a Slovak umbrella movement, but the power was effectively concentrated in the hands of its chairman. Despite the numerous challengers who regularly ran against him, in 1993, 1994, 1996–97, 2002, 2003, and 2008, citing his autocratic decision making, Mečiar held onto the post of party chairman, and these repeated victories in party elections confirmed and re-inforced his position (Rybář, 2011: 57). Formal confirmation of the leader’s dominance came with a change in the party statutes in 2000 (Kopeček, Reference Kopecký2006: 254–255). By the late 1990s, other political party projects in Slovakia were signalling a trend, which was to spread to Central Europe, in which parties were started from scratch by strong political figures with a presidentialized concentration of power within the party ordained genetically. Among these was SOP, founded by Rudolf Schuster, mayor of Košice, and ANO, founded by Pavol Rusko, the first entrepreneurial issue party in Central Europe.Footnote 10 Both of these parties, however, managed to stay in the parliament only for a single election period (Kopeček, Reference Kopecký2006: 261 and 265–267).

In a spirit similar to that of the ANO and SOP projects, Smer came into being in 1999. It was founded by Robert Fico, a former SDL politician who reacted to the fall of his party by founding a new left-wing entity. The combination of protest rhetoric directed against Mečiar’s HZDS and against the right-wing government of the time, along with the party’s anti-establishment appeal and strong leadership both outside and inside the party, resulted in its swift establishment in the Slovak party spectrum. Later, for pragmatic reasons, Fico – with some complications – re-targeted the party towards social democracy, although maintaining its remarkable organizational form concentrated in the hands of the party chairman. Initially, only the chairman, the general manager, and the party bureau created the structure of the highest party bodies. There was no vice chairman to endanger Fico’s power. From 1999 until 2001, the entire organizational structure of the party was built upon the managerial principle. Only after 2001 did a more or less classic organizational structure arise in an attempt to look more like a ‘standard’ social-democratic party, one that was centralized, even at the level of regional structures. However, it is important that the actual reorganization did not endanger Fico’s dominance, nor did it impact his intensively hierarchical style of party management (Rybář, 2011: 51).

The gap between the organizational structure and the actual dominance of the party chairman actually increased somewhat. Smer’s operation was not de-presidentialized even once its membership base had been increased in a 2004 merger with small left-wing parties Kopeček, Reference Kopecký2006: 261–264; Rybář, 2011: 65–69). During the first decade of the new millennium, Fico’s personality became a dominant element, polarizing Slovak public opinion, and reflected in the strong personalization of electoral campaigns that took place (Haughton et al., Reference Havlík and Hloušek2011: 396–398). Nor did Fico hesitate to leverage his position as Prime Minister in the 2010 election campaign. Fico’s campaign highlighted the role he played in managing the consequences of the floods suffered in eastern Slovakia at that time, as well as extraordinary sessions of parliament he called (Henderson, Reference Hopkin and Paolucci2010: 6). Fico played up this heritage of a strong, proactive government in the 2012 elections, as well, contrasted to the fragmented cabinet of Iveta Radičová (Spáč, 2014: 344).

This personalization of election campaigns has generally been present in all five countries of Central Europe, very frequently taking the form of ‘Americanization’, with a strong media component and the professionalization of campaigns and greater emphasis on the debate over which a strong leader of the large political parties will assume the Prime Minister’s post after the election. However, this presidentialization in election campaigns does not always transfer to internal party operations or into the presidentialization of governmental politics.

Poland’s PiS has also possessed strong tendencies towards presidentialization from the beginning of its existence. Under the leadership of Lech (2001–03) and Jaroslaw Kaczyński (since 2003), the party has focussed primarily on forming its ideological attitudes as opposed to creating a party organization that would ‘dilute’ the power of the party elite headed by its chairman (Tavits, 2013: 237). Initially, PiS built upon the strong popularity of Kaczyński and a vaguely described project targeting transformation of the Polish political system (the ‘Fourth Polish Republic’), personified in the long-term political work of both brothers (Hloušek and Kopeček, Reference Kopecký and Wirnitzer2010: 175).

The 2005 presidential election campaign represented a significant example of the increased level of presidentialization in Polish elections. In the second round, the battle was between two strong party leaders – Tusk and Kaczyński. Each man was responsible for the strategy of his party, and in each case that same strategy was used in both the presidential elections and in the parliamentary elections that had taken place 2 weeks earlier (Millard, 2010: 135–138). This trend towards the presidentialization of PiS was re-inforced from 2005 to 2010, when Lech Kaczyński served as president.Footnote 11 This was apparent in the intense media debate that surrounded the leaders of the strongest parties in the 2007 Polish parliamentary elections. In addition to Tusk and the Kaczyński brothers there was Aleksander Kwaśniewski, a left-wing candidate who had been president from 1995 to 2005 (Millard, 2010: 150–154). According to Polish political experts, a television debate in which Tusk clearly outdid Kaczyński was one of the key moments in PO’s victory.Footnote 12 Both the 2010 presidential elections and the 2011 parliamentary elections, which took place following the tragic death of Lech Kaczyński, were used by his brother Jaroslaw to re-inforce the party leadership’s charisma, this time bolstered by the cult of the deceased president. This was not only an election strategy but was also used by Kaczyński to further a highly authoritarian style of party management (Tworzecki, Reference van Biezen2013: 618–619).

A comparison of the position of chairman in current mainstream presidentialized parties based upon their party statutes (SDS, 2013; Smer, Reference Spáč2010; Fidesz, Reference Harmel and Svåsand2013; PiS, 2013) shows that presidentialization is a rather informal process of re-inforcing the leader’s power. Formally, the definition of the function and powers of the chairmen of Smer and SDS reveals no extraordinary powers; the chairman is part of the collective party leadership. In PiS, most of his actions must be confirmed by other collective leadership bodies. However, the chairman also plays a role in the formal nomination process – for example, in preparing the ballots for presidential and parliamentary elections, as well as elections to the European Parliament. With a strong political personality at the helm of the party, this does not effectively prevent the party leader’s influence from being strengthened. In the case of Fidesz, powers that formally re-inforce the chairman’s power include the option to appoint the party’s regional directors and to bind party members right down to the level of the local party organization to rules that benefit the successful implementation of election campaigns. Fidesz, then, is, among traditional parties, the organization that has seen the greatest formalization of the presidentialization process.

Presidentialization as the basis of an organization: the preferred organizational model in contemporary Central European politics

As noted above, a number of newly created parties show a tendency towards the presidentialization of leadership. These are parties that are frequently formed by strong political figures as personal projects. Current examples include the Czech parties VV, ANO, and Úsvit Přímé Demokracie, the Polish TR, the Slovak SaS, and Slovenian projects DL, PS, SMC, and ZaAB.

VV, a party that took part in Czech parliamentary and governmental politics from 2010 to 2013, is a peculiar case among entrepreneurial issue parties. Starting in 2005, when it was still a small, non-parliamentary party active in Prague city politics, it began to be taken over by a group led by Vít Bárta, the owner of a security agency. He became the party’s formal chairman only during a several-month period after its de facto disappearance in 2013, but it was Bárta who was completely responsible for the party’s direction, and he made both the strategic and the organization decisions. The combination of populism, political marketing, and massive centralization of the party decision-making process made VV a presidentialized party on a level unprecedented in the Czech Republic, one which in many respects was more reminiscent of a private firm with a management hierarchy than of a democratic political party (see Havlík and Hloušek, Reference Henderson2014: 561–564).

Tomio Okamura’s Úsvit Přímé Demokracie was a highly presidentialized entrepreneurial issue party from its beginnings. Its formal foundation came as a political movement in June 2013. Okamura was a businessman and senator in the Czech parliament whose goal was to get a slate elected to the Parliament in the early elections of autumn 2013. From the outset, Okamura formed the movement as a highly hierarchical, small, professional structure. Its members never exceeded nine in number, less than the 14 MPs elected to the Chamber of Deputies on its behalf. Under its statutes, (Úsvit, Reference van Biezen, Mair and Poguntke2014), the chairman has the right to veto the acceptance of any new member, giving the movement an organizational structure more similar to that of a joint stock company than a political party. The actual level of centralization of the movement’s operation both internally and externally and the lack of transparent accounting led to growing dissatisfaction by some MPs elected on behalf of Úsvit. In January 2012, they ousted the head of the Parliamentary Club, who was loyal to Okamura, and shortly thereafter announced they were attempting to build a new party inspired by the French Front National. Úsvit’s fate was sealed. During his short time in the parliament, Okamura represented a model of extreme presidentialization.

SaS was established in the early months of 2009 by Richard Sulík, an entrepreneur and economist who had prepared the reform of the Slovak tax system in 2003. In terms of its ideology, the party is characterized as a right-wing party focussed primarily on economic liberalism, combined with soft euroscepticism. Especially in its beginnings, the party protested the actions of existing parties, emphasizing that it was not building upon any previous political grouping. The party’s possession of a dominant leader, a ‘spiritual father’, at the helm since its founding, has meant that the party has explicitly given up attracting a mass membership. It is not a closed club like its Czech counterpart Úsvit, but the procedure for the enrolment of new members is complex, and the party has never made any effort to increase the size of its member base (Mesežnikov, Reference O’Brennan and Raunio2013: 63). The informal dominance of Sulík, the chairman, is indicated by the party statutes (SaS, n.d.) fairly ambiguously. He is present by virtue of the fact that the powers of each national body are given in detail, exhaustively, but anything not explicitly laid out may be decided by the chairman.Footnote 13

TR served from the beginning as a tool to further the political career of its founder – Janusz Palikot. Palikot had been very successful as a Polish businessman for some time, and entered politics only in 2005, becoming one of the most stringent critics of PiS and the Kaczyński brothers. Palikot’s gradual radicalization and his iconoclastic, deliberately provocative style of political communication resulted in him leaving the PO to found his own movement in late 2010 and early 2011. This new party, called the Palikot Movement, came into being in summer of 2011 and, thanks to a successful campaign built around the leader (Gałązka and Waszak, Reference Haughton and Deegan-Krause2013: 210) that re-branded him as a serious politician instead of a rebel (Szczerbiak, Reference Tworzecki2012: 9), it defied pre-election surveys to win seats in the parliament. In autumn of 2013, the party merged with several small groups to become the formation now called TR. Palikot’s domination was in no way lessened. TR’s statutes (TR, Reference van Biezen and Kopecký2013) show that, in conjunction with research done by Polish scholars (Gałązka and Waszak, Reference Haughton and Deegan-Krause2013: 212–216), the degree of presidentialization in the party’s organizational structure is somewhat lower than that present in the Czech entrepreneurial issue parties. Internal disagreements have taken place within the movement, and the mechanisms for creating the candidate slate tend towards participation of collective bodies. However, TR does not encourage a mass membership base, and Palikot remains the sole political figure to represent the party to the world at large.

In Slovenia, the 2011 and 2014 parliamentary elections brought an influx of new presidential political formations. DL, led by Gregor Virant, a university professor, won seats in the parliament (Virant had been the most popular minister under Janša’s government, heading the Ministry of Public Administration). Gregor Virant starting the party particularly surprised SDS, because Virant, even though not an official member of Janša’s party, had taken part in preparing SDS’s platform (Krašovec and Haughton, Reference Kriesi2012: 7–8). However, this strongly personalized party dropped sharply in the 2014 elections, even though Alenka Bratušek was in the government.

The parties noted above fulfil or have fulfilled the characteristics of a presidentialized party in the party politics sphere and those of an organization in the sphere of electoral politics. Owing to their fairly restricted voter support, and because their ideological profiles (Úsvit) or strategic choices (Palikot, VV, and SaS) have placed them outside the political mainstream, they have not ordinarily aspired to the status of presidentialized parties at the level of governmental politics, even if their participation in the government has in some cases witnessed a specific type of presidentialized style (VV). However, some of these new parties (ANO, PS, SMC), thanks to support from the voters and because they have assumed (co-)responsibility for the government, have or could have practised the presidentialized political style in this sphere.

ANO was founded as a political movementFootnote 14 in 2011 by Andrej Babiš, owner of Agrofert, a leading Czech and Central European economic group, particularly active in the food and petrochemical industries. The movement originated in autumn of 2011, a product of Babiš’s populist criticism in the media of the Czech political, and especially the governmental, elite as feckless and corrupt. The movement was formally registered in May 2012, and in October 2013 it came second in the early parliamentary elections, entering the governing coalition. From the outset, top management at Agrofert took part in organizing the movement.Footnote 15 Behind the façade of well-known faces, frequently recruited from outside traditional party politics to lure voters, stood a substantially hierarchical, centralized structure more reminiscent of a company than a party. The infrequent attempts made by the movement or at conventions of regional organizations for political emancipation have always come up against the strong resistance of Babiš, who exercises his leadership in a highly personalized manner (Kopeček, Reference Kopecky2015). The clearest expression of the movement’s centralization and pacification of its member base came at the convention of spring 2015, where there was no discussion whatsoever, in spite of statutes being modified and the party leadership being elected. The symbolic apex was the unanimous re-election of Babiš as party head without rival.Footnote 16 Babiš took a similarly radical tack during the early parliamentary elections in 2013, when he used the slogan ‘We’re not politicians, we work!’ to present himself as a successful entrepreneur and the only person capable of changing Czech politics. Babiš dominated the election campaign – ANO invested heavily in campaign advertising – and media coverage of the elections. In addition to buying MAFRA, which publishes the most-read Czech non-tabloid print outlet, in summer 2013, he also became a central figure in media coverage when allegations arose that, before 1989, he had collaborated with the Communist Secret Police (Havlík, Reference Hloušek and Kopeček2014: 75–83).

However, even these cosmetic changes ultimately end up formalizing the presidentialization of the party’s internal activity. Under the amended statutes (ANO, 2015), the chairman has effectively become essential during political negotiations, whereas the Bureau has gotten the right to appoint candidates for all types of elections. Article 13 is also important in that it defines the positions of the chairman and vice chairman of the movement, and grants the chairman the right to appoint or revoke the movement’s key manager, as well as regional managers. The role of managers, meantime, is not defined under the statutes in any way; instead it is governed by ANO’s internal regulations. Owing to the two-track political and ‘managerial’ management structure, the chairman thus gets hold of a very significant lever in determining key issues related to the financial and administrative functioning of the party.

In Slovenia, PS was also founded shortly before the parliamentary elections, specifically in October 2011 by Zoran Janković, a Slovenian entrepreneur and mayor of Ljubljana from 2006 to 2011 (re-elected in 2012). Owing to the growing importance of the media in campaigns, and particularly because of the television debates focussed on the search for the new prime minister, Janković was able to transform the campaign into a personal battle between the chairmen of PS and SDS (Janez Janša) for the post (Krašovec and Haughton, Reference Kriesi2012: 8). The party won the greatest number of seats in the parliament, but was still locked out of the governing coalition. The original promise brought by the presidentialized style of leadership in PS was inverted in January 2013, when Janković resigned after allegations were made against him by the Commission for the Prevention of Corruption of the Republic of Slovenia. His position at the helm of the party was taken by Alenka Bratušek, who put together a coalition government in the interim period. However, Janković soon sought to return to the head of the party, and his success in getting re-elected as chairman in April 2014 not only drove Bratušek and her supporters out of the party and forced the fall of the PS coalition government (Krašovec and Deželan 2014: 81), but also re-installed a charismatic leader with presidential tendencies in party organization and management at the helm of the party. Further development of this tendency was blocked by the party’s freefall in both the European and parliamentary elections in 2014. However, the faction led by Bratušek continued to build a party structure around a strong political figure. ZaAB became a political party in May 2014. A comparative analysis of organizational documents from both parties is enlightening (PS, Reference Sartori2013; ZaAB, n.d.). They resemble each other to a great extent in those sections devoted to the party chairman, including the fact that the party chairman is to be elected by a general vote of all members. With regard to the formal definition of the party leader, the statutes in both parties bring no extraordinary competencies, and thus in this case, as well, we must instead explore the informal presidentialization of the party’s functioning.

The last party to be analysed, Slovenia’s SMC, also in some sense followed the footsteps of DL in 2014. Miro Cerar got into politics shortly before the 2014 parliamentary elections, before which he had been a professor of constitutional law at the University of Ljubljana and an advisor to the Slovenian parliament. A mere 6 weeks before the elections, he founded the eponymous Miro Cerar Party. Playing off his image as an expert (he was one of the drafters of the Slovenian constitution), non-politician, and corruption fighter, he won the elections, obtaining more than a third of the vote. In 2014, he became Prime Minister of Slovenia. In March 2015, the party congress changed its name to the Modern Centre Party, while retaining the designation SMC. The statutes currently in effect (SMC, Reference Spáč2015) were also adopted and do not formally exceed the limits designated for Slovenian party leaders. Owing to the way the party came into being and the rapidity with which its leader became Prime Minister of a government in which the party holds the majority of positions (10/17), one cannot rule out the hypothesis that a new, significantly presidentialized party has come into being.

Potential and limits of the party presidentialization concept as applied to Central Europe

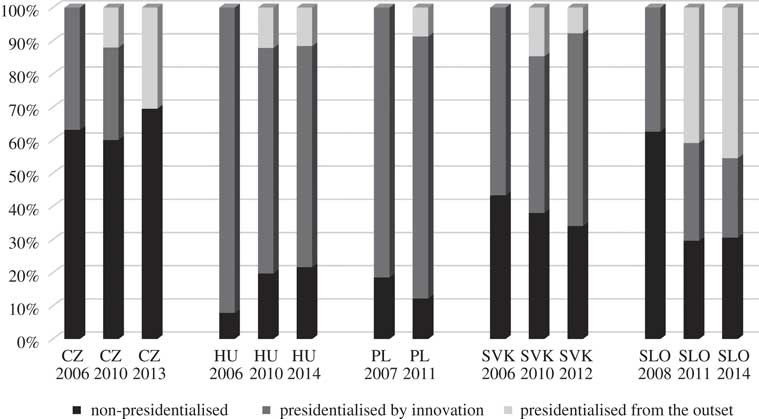

The presidentialization of the organization and distribution of power within parties is in a growth trend in Europe; the parties are also capable of achieving promising electoral gains, as is schematically shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Share of mandates in lower chambers in Central Europe according to the type of presidentialization. Author’s calculation based on www.volby.cz; www.valasztas.hu; pkw.gov.pl; www.statistics.sk; www.dvk-rs.si; accessed 7 April 2015. See Appendix I for details on particular elections and parties.

The figure shows that all Central European countries have been impacted by the incidence and success at the polls of presidentialized parties, but certain differences may be observed in the general trend. Parties in the Czech Republic are most resistant to presidentialization. In Hungary, the trend is declining, but only modestly. In Poland and Slovenia, there is a growing proportion of parties that have presidentialized the functioning of their party organizations. With the exception of Slovakia, the proportion of new parties opting for a presidentialized ‘party face’ from the outset is growing. In Poland and in Hungary, however, traditional parties that have only recently undergone significant presidentialization still prevail. In these cases, presidentialization is the result of strategic innovation aimed at mobilizing voters. It is certainly true that the presidentialization concept should be an integral part of the research arsenal of any scholar focussed on party politics and the functioning of political parties in the Central European region.

In attempting to summarize the overview of presidentialized parties given above, the presence of both formulae for the presidentialization of party organization is clear: (1) presidentialization as an innovation strategy, in which established parties that have traditionally opted for collective party leadership transfer power to a strong leader to aid their expansion and survival in a volatile election market, and (2) presidentialization as the basis of an organization, with a clear preference for a strongly centralized, personalized party that is built around a leader from the outset. The latter is an attractive choice for parties currently being created in the context of the changes that have shook Central European party systems in ‘electoral earthquakes’ that have brought new opportunities for anti-establishment and protest parties. However, as we have seen, this formula was present long before the post-2010 period that is our central focus. Observing the fate of stronger presidentialized parties allows us to see how the benefit of having a strong leader, one who need not ‘bother’ with internal party democracy and debate among various wings in a broader party elite, may turn sour when the charismatic leader falls out of voters’ favour or the party expends its protest capital by taking part in the governing coalition. Despite this, it is justifiable to presume that the trend towards presidentialization in party leadership will not easily be turned around in Europe, nor will the trend towards strongly centralized, highly personalized internal party politics with a dominant leader. The lack of interest shown by citizens in political participation via party membership has logically forced the elites to search for other organizational models than those offered by mass or catch-all parties. The centralization of decision making may bring with it certain comparative advantages in the electoral and party politics sphere.

Within Central Europe, however, total presidentialization in the governmental sphere comes up against a number of limits. Looming large among them is the long-term tradition of coalition governments, which logically restricts opportunities for strong party leaders to unconditionally dominate government policy and prevents them from shifting their roles towards that of the president in a presidential system. In particular, in the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Slovenia, coalition governments are brought in terms of the parties represented, and seats are frequently distributed in a way that intentionally blocks the dominance of the strongest member of the governing coalition. In all the Central European countries, except Hungary, minority governments are frequent, substantially limiting the role of the prime minister in the parliamentary sphere and, in a sense, pushing the need for compromise from the governmental sphere to the parliamentary sphere. However, even prime ministers in the journey, ideologically heterogeneous coalitions must also sometimes seek partners outside the ruling coalition in parliamentary voting (Jiří Paroubek 2005–06, Janez Drnovšek 1992–2000). To that may be added the fact that minority coalition governments are no rarity (Balík et al., Reference Balík, Havlík, Havlík, Kmeť and Svačinová2011: 227–251; Cabada et al., Reference Detterbek2014: 137–138).

If we exclude the era of Vladimir Mečiar in Slovakia (1993–94 and 1994–98), it is the governmental sphere in Hungary that stands alone in this regard. Hungary, too, has seen many years of coalition governments, but these normally comprise two parties, with the stronger coalition member possessing a significant power edge. This is true for both most socialist governments (Gyula Horn 1994–98, Ferenc Gyurcsányi 2004–09) and for Orbán’s cabinets after 2010. In Poland, such dominance has occurred only in the governments led by PO under Donald Tusk (2007–14). Presidentialized leadership was a factor in the government of Robert Fico when he helmed a single-colour majority Smer cabinet after the 2012 elections, and to some extent also when Fico dominated a coalition government in which Smer had a clear advantage (2006–10).Footnote 17

It is, therefore, more common in Central Europe for strong political figures to be compelled to seek mutual balance within the government coalition. In some cases (the best examples are the Czech cabinets of Petr Nečas in 2010–13 and Bohuslav Sobotka from January 2014 until present), strong leaders may overshadow or effectively compete with the prime minister.Footnote 18 Further research into the style of governance of Viktor Orbán, Donald Tusk, and Robert Fico could bring valuable information on the presidentialization of the government arena in Central Europe.

Conclusion

The trend towards presidentialization is present in the party politics of Central Europe just as it is in the party politics of Western Europe. The number of parties in the parliaments of the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia that are presidentialized is rising. The trend is most evident when it comes to election politics. Here, the strategy of concentrating the campaign around a national party leader is employed even by parties that continue to favour collective leadership, and it is also clear that the number of parties that have presidentialized their internal structure and centralized power in the hands of a leader is on the upswing. Presidentialization takes place in one of two ways when it comes to internal party politics. It either results from an innovation strategy taken by established parties or is used by new parties established on the basis of a strong presidentialized structure and party management style. In the former case, presidentialization is built upon shifting the parties in the direction of cartel parties; in the latter, entrepreneurial issue parties are frequently the focus. The full presidentialization of Central European governmental politics is braked by frequent practice among coalition governments that leads in real terms to a fragmentation of power. In some instances, however, governments have a strong inclination to presidentialize the post of prime minister, if structural conditions allow. The presidentialization concept is, thus, a significant heuristic tool for researching Central European politics.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Katarína Deáková and Vratislav Havlík for their help in researching Hungarian primary sources and Lubomír Kopeček for consultation on the draft manuscript.

Financial Support

The research has been funded by the Masaryk University project ‘Europe in a Changing International Environment’ (MUNI/A/1316/2014).

Appendix II: List of abbreviations

ANO – Alliance of New Citizen (Slovakia)

ANO – Yes 2011 (Czech Republic)

ČSSD – Czech Social Democratic Party

DESUS – Democratic Party of Pensioners of Slovenia

DK – Democratic Coalition (Hungary)

DL – Civic List of Georg Virant (Slovenia)

E14 – Together 2014 (Hungary)

Fidesz – Union of Free Democrats–Hungarian Civic Alliance

HZDS – Movement for a Democratic Slovakia

JOBBIK – Movement for a Better Hungary

KDH – Christian-Democratic Movement (Slovakia)

KDNP – Christian Democratic People’s Party (Hungary)

KDU-ČSL – Christian and Democratic Union–Czechoslovak People’s Party

KSČM – Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia

LMP – Politics Can Be Different (Hungary)

LPR – League of Polish Families

MH – The Bridge (Slovakia)

MIÉP – Hungarian Justice and Life Party

MSZP – Hungarian Socialist Party

NSi – New Slovenia–Christian Democrats

ODS – Civic Democratic Party (Czech Republic)

OĽaNO – Ordinary People and Independent Personalities (Slovakia)

PiS – Law and Justice (Poland)

PO – Civic Platform (Poland)

PS – Positive Slovenia

PSL – Polish People’s Party

SaS – Freedom and Solidarity (Slovakia)

SD – Social Democrats (Slovenia)

SDKÚ-DS – Slovak Democratic and Christian Union–Democratic Party

SDĽ – Party of Democratic Left (Slovakia)

SDS – Slovenian Democratic Party

SLD – Union of Democratic Left (Poland)

SMC – Miro Cerar Party/Modern Centre Party (Slovenia)

Smer – Direction–Social Democracy (Slovakia)

SNS – Slovak National Party

SNS – Slovenian National Party

SOP – Party of Civic Understanding (Slovakia)

SPR-RSČ – Rally for the Republic–Republican Party of Czechoslovakia

TOP09 – Tradition, Responsibility, Prosperity (Czech Republic)

TR – Your Movement (Poland)

VV – Public Affairs (Czech Republic)

ZaAB – Alliance of Alenka Bratušek (Slovenia)

ZL – United Left (Slovenia)