Introduction

The Avesta, the holy book of the Zoroastrians, is a compilation of sacred ancient texts, which has been fractionally transmitted to us. The extant texts demonstrate only part of the Great Avesta, which was described in the Pahlavi literature.

The Avestan texts were probably handed down in oral form over a long period of time. They were composed at some time in the late Sasanian era (ca. 224‒651 CE).Footnote 1 The oldest manuscripts of the Avesta are from the thirteenth‒fourteenth centuries (Visperad (Vr) ms. K7a: 1278?; Yasna mss. 12 and K5: 1323; Videvdād (V) mss. K l: 1324, L4: 1323; Xorde Avesta ms. Jm4: 1352),Footnote 2 but the majority of the Avestan manuscripts that have been discovered so far originate from much later times, mostly from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries.

About 150 years ago, after Avestan researchers such as A. V. Williams Jackson, E. G. Browne, and Niels Ludvig Westergaard had unsuccessfully attempted to discover new manuscripts, it was assumed that there were few or no Avestan manuscripts remaining in Iran. But our research and fieldwork in Iran resulted in important findings countering this assumption. Since 2011, through collaboration with Iranian scholars, the University of Salamanca, and the Avestan Digital Archive, we have discovered more than ninety Avestan manuscripts with both long liturgies (Yasnā, Visperad, Videvdād, Vištāsp Yašt) and short liturgies (the collection of the Yašts and Xorde Avesta). During my research trip in February 2016 to Yazd, I found nine Avestan manuscripts (Pouladi Collection) dating from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries. One of them appears to be the oldest Iranian Videvdād Sāde that has been discovered so far,Footnote 3 while another is the sole illuminated manuscript from the Marzbān family, a famous scribe family of Avestan manuscripts. Three months later, I discovered another collection of eight Avestan manuscripts in Yazd. These discoveries have resulted in changes to many aspects of Geldner's edition of the Avesta and older theories in the field of Avestan and Zoroastrian studies.

Different kinds of information in Avestan manuscripts can clarify many aspects of Zoroastrian culture and history.Footnote 4 One of the most relevant types of information is genealogical, which can be used to reconstruct the family trees of Zoroastrian families and which can then help us follow the story of transmission of Avestan manuscripts.

The Avestan manuscripts are not only a collection of sacred and ritual texts in the Avestan language, but they also form a treasury of cultural and historical information.

Different parts of Avestan manuscripts seem to represent the influence of an Iranian language other than Persian and Pahlavi. This language might be Zoroastrian Dari (ZD), the language of the Zoroastrian minority in Iran.

Zoroastrian Dari and Differences between the Dialects of Yazd (ZDY) and Kerman (ZDK)

Zoroastrian Dari has been generally considered to be closely related to central dialects.Footnote 5 However, it also shares features with languages of the northwestern group (NW) group, especially Zazaki and Sorani, and with languages of the southwestern group (SW) group, such as Persian.Footnote 6 The sharing of both NW and SW features draws our attention to the fact that the Zoroastrian immigrants to Yazd and Kerman came from different regions of Iran and different language groups. There are two main dialects of Dari: Kermani and Yazdi. The dialect of Yazdi has many subdialects,Footnote 7 while there appears to be only one dialect of Kermani. There were probably various dialects of Kermani in earlier periods of time, but today we find only one. These possible former Kermani dialects outside of Kerman would be Jupāri, Qanātqestāni, and Esmāʿilābādi.

There are a number of differences between ZDK and ZDY in terms of phonology, morphology, and syntax. Phonological differences are of particular importance for the topic of this article and are therefore discussed first. One difference is the sound change of historical ā to ů in Yazdi, while Kermani appears to be closer to Persian here (ZDY důr-, dår-, present stem of důrtvun/důštvun “to have”; ZDK dār).Footnote 8 This change is considered to be extremely trivial and has taken place in many Iranian languages, perhaps very recently. Kermani ā in an initial position can be compared to a bilabial spirant w or to the vowel å in Yazdi (Kermani ārt “flour,” Yazdi vurt; Yazdi vudem “man, human,” Kermani ādem). In some Yazdi subdialects ϵ is found, while this vowel has changed to e in Kermani (Yazdi čϵm “eye,” Kermani čem; Yazdi ϵ “to, with, from,” Kermani e). As for enclitic pronouns, a final n in Kermani is attested, while there is no final n following the long vowel in Yazdi. The infinitive ending in Yazdi is vun, while in Kermani mun is attested (Yazdi kartvun “do, make,” Kermani kartmun). Initial h- is lost in Kermani, while it has been preserved in Yazdi. This rule can be found in both Iranian words and Arabic loanwords (Yazdi ham- “together,” Kermani em-; Yazdi hϵmum “bath,”Footnote 9 Kermani emum; Yazdi heč, hečči “nothing,”Footnote 10 Kermani eči).

Yazdi and Kermani Scribes of the Avestan Manuscripts

Let us come back to the main question of this research: is Zoroastrian Dari attested in the Avestan manuscripts? And if this is the case, would it be possible to recognize two different dialects of Yazdi and Kermani in them?

The reason for presenting this question would be the fact that the scribes of Iranian Avestan manuscripts mostly originated from Yazd and Kerman, and it is thus probable that their manuscripts would also reflect the dialects of the scribes. If we find one of the above-mentioned differences between ZDY and ZDK in a part of the Avestan manuscripts, that would serve as evidence for the existence of two different dialects.

The scribes of the Marzbān family all came from Kerman. The names of these scribes were Marzbān (died in 970 AY (Anno Yazdgerdi), scribe of IM 1575, *Jp1, BK, or K35?, DH), Frēdōn (died in 1004 AY, scribe of Vr 2005, V 4000, Vr 2010, V 1638 (Jp1), Vyt (Vištāsp Yašt) 5010 and TD 2), Bahrām (died in 1021 AY, scribe of YR 300, V 4010, V 4025, V 4030, Vyt *5020 (K4)), and his two sons Marzbān (died in 1055, scribe of V 1022Footnote 11 and V 1044), and Šahmardān (died in 1046 AY, scribe of V 4063).Footnote 12 It should be kept in mind that a number of their manuscripts were scribed in Yazd and not in Kerman. For example, we know that Frēdōn Marzbān was invited from Kerman to Šarifābād, a village near Yazd, for the copying of V 4000. He wrote this manuscript in memory of Jamšid, a young bridegroom who had died there. The fact is, if the place of the copy is in Yazd, it does not mean that the scribe necessarily comes from Yazd or speaks Dari with a Yazdi dialect.

There are also a number of manuscripts that were written in Yazd probably by Yazdi scribes, for example, Y 10 (Mf1), which was scribed by Rōstam Guštāsp Irdešir, then V 4020, scribed by Xōsrō Anōšagruwān, and 4055 and 4060, scribed by Mehrabān Anōšagruwān, all in Turkābād (Yazd). Two further manuscripts, V 4045 and V 4050, were also written by Mehrabān Anōšagruwān, but the place of copy is not mentioned in the manuscript.

Here it is useful to look at the various components of the Avestan manuscripts and try to find out if and in which parts Zoroastrian Dari is attested. The components of Iranian Avestan manuscripts include (1) Avestan text; (2) Nērangs and instructions (in Pahlavi, Persian, Pāzand); (3) colophons (in Pahlavi, Persian, Pāzand); (4) Sālmargs (only in Persian); and (5) verses and additional comments (in Persian).

The language of the verses, non-Pahlavi colophons, and Sālmargs, is Persian, containing many Arabic loanwords. In all of the material, there are no remnants of Zoroastrian Dari. The only traces of Zoroastrian Dari are found in the Pahlavi and Pāzand colophons as well as in Sālmargs, and there, only in personal names. I would hypothesize that, in the Nērangs, we can also find traces of Zoroastrian Dari, to be examined in further study.

Colophons of the Avestan Manuscripts

In an Avestan manuscript, a colophon is a statement giving information about the manuscript and its history. A colophon contains information about the background of the scribe and the copy of the manuscript, such as the name of the scribe, the name of the book, the place of copy, the sponsor of the manuscript, and the date of copy. Different kinds of information in colophons can help to clarify many aspects of Zoroastrian culture and history. One of the most relevant types of information is genealogical and historical, which can be used to reconstruct the family trees of Zoroastrian families and which can then help us follow the story of transmission of Avestan manuscripts. In the Videvdād manuscripts, colophons occur before the ninth Fragard and, in some cases, they are also found at the end of the book.

There are only a few works on the colophons of Avestan manuscripts. Various colophons of Pahlavi Videvdād manuscripts were edited and translated by Peshotan Sanjana.Footnote 13 The only book on this topic is Jamshedji Maneckji Unvala's Collection of Colophons of Manuscripts bearing on Zoroastrianism in some Libraries of Europe, which was published in 1940. The author was the late secretary of the Parsi Punchayat Funds and Properties. His book is the result of his work on the manuscripts of various libraries located in Europe, such as the Bibliothèque Nationale of Paris, the British Library, the India Office library, London, and the University Library in Munich, as well as libraries in St. Petersburg, Copenhagen, and others. The author provided a transcription and translation of colophons, and he also included genealogies of Indian and Persian scribes as well as synchronisms of the Zoroastrian, Hindu, Islamic, and Christian dates mentioned in some colophons. The other work is the article “Remarks on the Colophon of the Avestan Manuscripts Pt4 and Mf4.” In this article, Alberto Cantera provides a transcription, transliteration, and translation of the central part of the Pahlavi colophon to the Avestan manuscripts Pt4 and Mf4, in which the history of manuscripts is recounted. He acquires a different view of the predecessors of Pt4 and Mf4, discusses the date of the manuscript, and finally, he provides us with a filiation.Footnote 14 In another article, “Building Trees: Genealogical Relations between the Manuscripts of Wīdēwdād,” in the section “Colophons,” he reproduces the history of the extant manuscripts.Footnote 15

In Iran in recent years, several activities have begun which are related to the discovery of new manuscripts. Katayoun Mazdapour has published many articles about the Avestan manuscripts. She provides general information about characteristics of these manuscripts and their colophons in her publications.Footnote 16 Fatemeh Jahanpour has published The Videvdād of Astān e Ghods Library and translated its colophons.Footnote 17 Since 2012, Alberto Cantera and the present author have been finding, localizing, and digitizing a large number of Avestan manuscripts,Footnote 18 in addition to the manuscripts that were used and evaluated by Karl Geldner.Footnote 19 A large number of these manuscripts include a colophon and are of particular importance for this study.

As previously mentioned, the names of scribes occur in all colophons of the Avestan manuscripts. For this reason, a large number of personal names and their variations are attested in the colophons. The pronunciation of the attested personal names differs in many respects from typical Persian pronunciation of the names. A question arises here: where do these pronunciations originate? In what follows, we try to answer this question.

The Dialectology of the Language of the Colophons

The dialectology of the language of the colophons raises many questions which cannot yet be regarded as resolved. There is no doubt that this language occupies an intermediary position between Middle Persian and Persian. On the basis of certain features of its phonological development and syntactical particularities, it is clear that another language might also have influenced the language of the colophons.

A similar discussion regarding the nature of the form of the language “Pāzand” can be found in the article “Pehlevi, pazend et persan” by Gilbert Lazard. In this article, he discusses relations of Pāzand with, on the one hand, the Middle Persian literary language—that is, Pahlavi—and, on the other hand, the common language of Islamic Iran, Persian. According to his research, Pāzand, with its transcription in Avestan letters, was invented in the Islamic period by the Zoroastrians of India who had been having difficulty reading the Pahlavi script, which was indeed very ambiguous, and who were no longer able to master the script's subtleties.Footnote 20 As a conclusion, Lazard notes that the tradition of reading Pahlavi according to the pronunciation of the Persian language was naturally preserved by the Zoroastrians who emigrated to India and settled there. This tradition was influenced at a later stage by the phonetics of the language of the Indian people, but we can still recognize in Pāzand traces of the spoken language from centuries earlier in south Iran. We can thus glean valuable information on socio-linguistic developments taking place in Iran a thousand years ago.Footnote 21 Evidence from the Pāzand colophons of the Avestan manuscripts confirms the theory of Lazard. The language of the Pāzand colophons demonstrates, on the one hand, some archaic characteristics from Middle Persian and, on the other hand, influence from Gujarati.Footnote 22 But the language of the colophons also shows influence from at least one other language. This language might be a NW language, based on evidence from a selection of syntactical and phonological particularities. Let us discuss this topic in more detail.

In the domain of morphosyntax, the Pahlavi colophons of the Avestan manuscripts demonstrate alignment patterns that can be grouped into three language types: (1) split ergative; (2) accusative; and (3) post-ergative. A number of Iranian languages, such as Middle Persian, Bactrian, and Pashto, are described as having an ergative construction, specifically what is known as “split ergativity.”Footnote 23 This alignment contrasts with what is found in languages such as Persian, where the single argument of an intransitive verb and the agent of a transitive verb are treated alike and kept distinct from the object of a transitive verb. A number of Iranian languages, such as Sorani Kurdish,Footnote 24 can be characterized by a “loss” of the ergative construction and are now essentially accusative languages, lacking the main features of split ergativity. Nevertheless, such languages still show some remnants of ergativity. In these remnants, a tense-sensitive alignment is exhibited, in which the coding of core arguments differs according to the tense of the verb, similar to that which is found in several western Iranian languages. In this alignment, the personal pronoun clitics change their roles when they occur with transitive verbs in the past tense. The enclitics change to proclitics and function as markers of subject agreement. The function of pronominal clitics as some form of agreement is well attested in several Iranian languages. Zoroastrian Dari belongs to this group of languages, which I prefer to call post-ergative languages.Footnote 25

In the Middle Persian colophons of the Avestan manuscript, all three above-mentioned constructions are attested. That means that two further languages—i.e. Persian, an accusative alignment language, and Zoroastrian Dari, a post-ergative language— influenced the Middle Persian language of the colophons.

In the following example, we find typical split ergative constructions, which are common in Middle Persian:

The use of the pronominal proclitics as an agreement marker in the past tense is obligatory in some central dialects such as Zoroastrian Dari. Its use is required even when an overt subject pronoun occurs in the same clause:

man i dēnbandak ǰāmāsb hakim ērdēšir anōšagruwān u=m ēn daftar i wištāsp yašt u-m did u=m pasandid u u=m āfarin kard bar nipištār Footnote 27

“I, the servant of the religion, Jāmāsp Hakim, [son] of Ardašēr Nōširvān saw this book of the Vištāsp Yašt, I liked it and bestowed praise on the writer of the book.”

In a number of ergative constructions in the colophons, we observe that the u=clitic (i.e. u=m) vanishes and instead of that, only the independent pronoun man occurs:

man dēnbandag mānuščihr ērdēšir i vāhrom spandyār ērdēšir nibišt u frāz hišt Footnote 28

“I, the servant of the Religion, Mānuščihr Ērdēšir Vāhrom Sfandyār Ērdēšir, have written it and launched it.”

There are many examples (i.e. in Vr 2010, in V 4025, V 1022, V 1025, V 4030, YR 300, 4010) of the use of an accusative construction instead of typical ergative one in the Middle Persian colophons. These examples can be clearly traced to influence from Persian.

man dēnbandag marzbān vāhrom marzbān frēdōn vāhrom rustom bondār šahmardān dēn-ayār nibištom Footnote 29

“I, the servant of the religion, Marzbān Vāhrom Marzbān Frēdōn Vāhrom Rustom Bondār Šahmardān Dēnyār, have written and launched it.”

The syntax and morphology of the colophons are a complicated topic because of the strong degree of equivalency, erroneous repetitions, and a mixture of Middle and New Persian languages. The above examples present some significant problems in understanding the dialectology of the language of the colophons. In contrast to morphology and syntax, it seems that the phonological characteristics demonstrate clearer results on the dialectal position of the language of the colophons. The personal names provide us with more details regarding the phonology of the language in the colophons and Sālmargs of the Avestan manuscripts.

Personal Names in the Colophons

As we study the personal names in the colophons, we observe that they occur in various languages. In Persian colophons, the personal names occur in a Persian form. In Pāzand colophons, the personal names appear in Persian, Pahlavi, as well as in Gujarati forms. In Middle Persian (Pahlavi) colophons, the personal names occur in various languages.

The personal names in the Pahlavi colophons can be divided into three main groups:

-

(1) Personal names written close to Pahlavi forms. This group is most common: e.g. dēnayār [dyn' ʾdybʾl] (in V 4000, V 4010, V 4030, V 4063, YiR (Yasnā i Rapiθvin) 300, V 1022;Footnote 30 šāhmardān/šahmardān [šʾhmltʾn (in K4, V 4000, V 4010, V 4030, V 4063, V 1022), and MLKA mltʾn (in YiR 300)].

-

(2) Personal names written close to Persian forms. These occur rarely. Examples of these forms are found above all in V 4158 (1288 AY, 1919 AD), e.g. Bahman, Xosro and in K4, e.g. Dēnyār [dyn' yʾr (?)] (Figures 1 and 2).Footnote 31

Personal names that do not belong to either groups (1) and (2) and instead are in forms of another language. These personal names are: Persian (Pers.) Bahrām; Pers. Rostam; Pers. Esfandiyār; Pers. Ardešir.

Figure 1. Bahman in V 4158 (1288 AY, 1919 AD).

Figure 2. Xosro in V 4158 (1288 AY, 1919 AD).

Persian Bahrām

Bahrām is one of the members of Marzbān family and the scribe of YR 300, V 4010, V 4025, V 4030, Vyt *5020 (K4). For this reason, his name occurs in all of these manuscripts as scribe. In different colophons, Bahrām mentions his filiation, and according to this information, we understand that he is the brother of Frēdōn and another son of Marzbān. In V 4010, he offers some information about his own life. For example, we learn that when he was thirteen years old, his father died. Thereafter he began to focus on religious instruction. He experienced the ceremony of Nozud when he was sixteen, with Nozud as the traditional ceremony of reaching priesthood. When he was twenty, he wrote V 4010.Footnote 32 Bahrām copied the first part of V 4025, and the Safavid part of V 4030 from the manuscript of his father and brother. We can also find his name in some of the letters which were sent to India around 1627 AD. His son Marzbān scribed Videvdād 1022 (1653 AD) and Videvdād 1044 (1675 AD), and he mentioned the name of his father in his affiliation in the colophons of these manuscripts (Figure 3). This name appears in the form of Vāhrōm in many manuscripts (for a list of these manuscripts see Table 1).

The name also occurs in the manuscripts of Mehrabān Anōšagruvān (V 4045, V 4050, V 4055, V 4060) in the form of Vāhrōm-šā (Figure 4).

Let us now look at the etymology and historical phonological development of this name. It occurs in various Iranian languages in the following forms: Avestan (Av.) Vǝrǝθraγna-, MP Vahrām, Bactrian (Bac.) Varahran, and Pers. Bahrām. In both Yazdi and Kermani Dari this name appears in the form of Vaa(h)rōm.

The form of this name in Pahlavi colophons is clearly a Zoroastrian Dari form and exhibits two developments: (1) a > aa—it seems that in this case, the scribe decided to write aa in the form of ā in the colophons; and (2) ā > ō, which is well attested in Zoroastrian Dari (Pers. tābe, ZD tůve “pan”, Pers. dāmād, ZDY zomůd, ZDK zumād “bridegroom”). The second change is considered to be extremely trivial and has taken place in many Iranian languages, probably very recently.

This name occurs in the Pahlavi colophons in the form of Zoroastrian Dari Vāhrōm. In Persian colophons, it occurs as Bahrām.Footnote 33 According to Table 1, it can be concluded that Pahlavi colophons exhibit a Zoroastrian Dari form of this name, that is, Vāhrōm [Vaahrōm].

Figure 3. Vāhrōm in Videvdād 1022.

Figure 4. Vāhrōm-šā in V 4045.

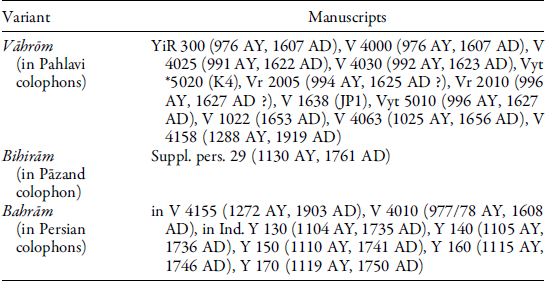

Table 1. The variants of the name Pers. Bahrām in Avestan manuscripts are shown here:

Persian Rostam

One of the other personal names that occurs very often in the colophons of the Avestan manuscripts is Rostam. This name occurs in different variations in the manuscripts, mainly in the genealogical information in the manuscripts of the Marzbān family scribes. Rostam is the grandfather of Frēdōn, and Frēdōn is the grandfather of Frēdōn and Bahrām, who were two main scribes of Avestan manuscripts. There are also other people named Rostam who have been mentioned in other manuscripts, for example, here in the colophon of V 1022:

The soul of good-name Rustom, that Rustom of the age, the great one of good speech, Rustom Dārāb, may participate. May god bless them. This manuscript was ordered by the wife of Rustom Husraw, for Rustom, the one of good speech, for his soul, so that their Dasturs, Dastur Ādur Anōšagruwān Ādur and the children of Dasturs and every Dastur and the children of Dasturs, and the religious people of good name, would perform the Yazišn ceremony with humility and good omens. May they use [it] with righteousness.Footnote 34

The second component of this name is Av. taoxman > MPM tōhm, MPZ tōm, Parthian (Prth.) tōxm, Pers. toxm. In this word, two different developments can be observed: (1) -xm> hm > m and (2) -ōh/uh > ō/u. According to these phonological developments, there are a number of variants, for example, as in Rōstōhm > Rōstōm/Rōstum in Avestan manuscripts. Rōstum/Rōstōm is the most common form. It has been used in YiR 300, V 4010, V 4025, V 4030, Vyt *5020 (K4), Vr 2005, Vr 2010, V 1638 (JP1), Vyt 5010, V 1022, V 4063.

The Pahlavi colophons of the Avestan manuscripts exhibit a large number of variants, which can be observed in Table 2. However, the Pāzand colophons show only two variants: Rustam and Rōstəm. The form Rōstəm could be a ZDY form, because the scribe used ə instead of e. In ZDK, the form Rōstem is attested.

Table 2. Variants of Rostam in the Avestan manuscripts

Persian Esfandiyār

This personal name occurs in the forms of Aspəŋdyār in the Pāzand colophon of Suppl. pers. 27,Footnote 35 Spəŋdyār in the Pāzand colophon of Suppl. pers. 47,Footnote 36 and Ispəŋdyār in the Pāzand colophon of Z. & P. 8.Footnote 37 The last form Ispəŋdyār demonstrates a ZD form. The name Aspəŋdyār in the Pāzand colophon of Suppl. pers. 27 is that of the grandfather of Rōstəm, and he is the father of the scribe of this manuscript, Dārāb. The second Spəŋdyār in the Pāzand colophon of Suppl. pers. 47 and Ispəŋdyār in the Pāzand colophon of Z. & P. 8 is the father of Giv, and Giv was the scribe of Z. & P. 8, which was sent to India.

Both Spəŋdyār and Ispəŋdyār demonstrate ZD forms.

Persian Ardešir

Another personal name that occurs in a ZD form in Avestan manuscripts is Pers. Ardešir. This name occurs in the form of ĒrdēširFootnote 38 in various manuscripts, particularly in the manuscripts of Mehrabān Anōšagruwān (V 4045, V 4050, V 4055, V 4060). Ērdēšir is the father of Vāhrōmšāh, and Vāhrōmšāh was the grandfather of Mihrbān Anōšagruwān. The sound change of ar- to ēr- is also attested in other examples such as Pers. Ardakān, a county in Yazd province, which occurs in the form Ērdekun in ZD. Figure 5 demonstrates the irregular use of initial y for ē in the orthography (as opposed to y-).

Figure 5. V 4045 (1004 AY, 1635 AD).

All of the above-mentioned personal names reflect ZD phonological characteristics. It appears that the scribes of the manuscripts wrote some of the personal names in their own dialect, which was completely different from the Persian or Pahlavi. These personal names have been pronounced in the same way in ZD up to the present time.

Remnants of Zoroastrian Dari in the Sālmargs of Avestan Manuscripts

There are many additional notes found in the Avestan manuscripts, such as verses, riddles, dates of birthdays, and examples of the Sālmarg, or “the date of death,” of the priest families. These dates, as pieces of additional information, are especially important for scholars in that they combine the observations of scribes with imagination and offer profound insights into the Zoroastrian culture and world view.

A Sālmarg contains information about the name of a deceased person who was a member of a priestly family. It also provides information about the year, the month, and the day on which that person died. The language of the examples of the Sālmarg is Persian.

An example of a Sālmarg in the manuscript V 1022 is the following, shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. The female personal name Šārbānu in a Sālmarg in V 1022.

Tārix-e vafāt-e mosammāt Šārbānu Dastur Bahrām Dastur Izadyār, dar ruz-e Anārām, Bahman māh-e qadim, sane-ye 10042Footnote 39

“The death date of the lady, Šārbānu Dastur Bahrām Dastur Izadyār, on the day Anārām, the old month Bahman, the year 1042 AY (1673 AD).”

This personal name occurs in another Sālmarg in the manuscript V 4010 (shown in Figure 7).

Figure 7. The female personal name Šārbānu in a Sālmarg in V 4010.

Tārix-e vafāt-e ašū ravān Šārbānū Dastūr Mehrabān Rostam dar rūz-e Māntresfand Bahman māh-e qadim sane-ye 1080Footnote 40

“The death date of holy soul, Šārbānū Dastūr Mehrabān Rostam, on the day Māntresfand, the old month Bahman, the year 1080 AY (1711 AD).”

The female personal name Šārbānu (in Persian Šahrbānu) occurs in a Sālmarg of V 1022 and V 4010. It is also a Zoroastrian Dari form. It should be said that šār- for šahr- is also attested in the New Persian form, šārestān for šahrestān, which represents an archaic form.

Results

It would be beyond the scope of this article to discuss all the topics that are relevant here, and in the future I hope to continue the discussion on the influence of local dialect on the language of Nērangs and on the Avestan parts of the manuscripts. For the time being, the crucial point is that the language of scribes strongly influenced the language of different parts of the Avestan manuscripts. From the discussion that follows, it will emerge that the language of the Middle Persian colophons exhibits a wide range of morphological, syntactic, and phonological influences from Persian and Zoroastrian Dari. A number of personal names occurring in the Pahlavi and Pāzand colophons, as well as in the Sālmargs, demonstrate phonological characteristics of Zoroastrian Dari. The forms of these personal names are Vāhrōm, Rōstəm and Ēspəŋdyār, and Ērdēšir. We know that the majority of scribes of Avestan manuscripts came from the regions of Yazd and Kerman. The members of the Marzbān family originally came from Kerman, and thus one expects that the personal names in the colophons of their manuscripts would demonstrate a Kermani dialect.

The extant examples of personal names in the colophons are limited, and they do not clearly present a dialectal phonological difference. The same ZD forms have been used in manuscripts of both Kermani (Marzbān family) and Yazdi scribes. The reason could be that the Pahlavi script cannot distinguish special vowels such as ε, ϵ, ů, and å. The only exception can be found in a Pāzand colophon, where the form Rōstəm is attested. It is not clear whether or not this ə has any dialectal significance or if it demonstrates a ZDY form in comparison to ZDK Rōstem. This form occurs twice in the manuscript Z. & P. 8, a manuscript of the Rivāyat of Kāmdin Šāpur that was scribed by Giv Ispəŋdyār Giv. Remnants of the Zoroastrian Dari are also attested in the Sālmargs of the Avestan manuscripts and in a female personal name, Šārbānu.

By means of this article, I have intended to show the relevance of the study of different parts of Avestan manuscripts to clarify the dialectal position of the language found in them. There are many open questions regarding this subject, and in order to find clear answers further research on such topics as possible dialect forms in ritual instructions, a more thorough analysis of the dialect features of Pāzand, and an examination of colophons from other non-Avestan Zoroastrian manuscripts is necessary.

Appendix: Manuscripts

YiR 300: Dated 976 AY, 1607 AD, scribed by Wāhrōm Marzbān, held at Vaziri library Yazd.

Vr 2005: Dated 994 AY, 1625 AD (?), scribed by Frēdōn Marzbān, held at the library of Tehran University.

Vr 2010: Dated 996 AY, 1627 AD (?), scribed by Frēdōn Marzbān, held at the First Dastoor Meherjirana Library, Navsari.

V 4000: Dated 976 AY, 1607 AD, scribed by Frēdōn Marzbān, held at the library of Tehran University.

V 4010: Dated 978 AY, 1608 AD, scribed by Wāhrōm Marzbān, Zolfagharis collection, Yazd.

V 4025: Dated 991 AY, 1622 AD, scribed by Frēdōn Marzbān, held at the library of Parvarešgāh-e Mārkār, Yazd.

V 4030: Dated 992 AY, 1623 AD, scribed by Wāhrōm Marzbān, held at the library of Āstān-e Qods-e Razavi, Mašhad, published by Jahanpour 2014.

V 4040: Dated 1001‒2 AY, 1632‒33 AD, scribed by Frēdōn Gōpadšāh Rōstōm Frēdōn, Niknams collection, Tehran.

V 4045: Dated 1004 AY, 1635 AD, scribed by Mehrabān Anōšagruwān Vāhromšāh, held at the library of Tehran University (for the story of the finding of this manuscript see Gholami, “Dāstān-e Vandidād-e 1004,” 29‒31).

*V 1638 (JP1): Dated 1007 AY, 1638 AD, the original scribed by Marzbān Frēdōn (copy of Šahryār Erdašir Ēriz Rostam Ēriz Kawād).

V 4050: Dated 1009 AY, 1640 AD, scribed by Mehrabān Anōšagruwān Vāhromšāh, held at Ketābxāne-ye Majles [Library of Parliament], Tehran.

V 4055: Dated 1014 AY, 1645 AD, scribed by Mehrabān Anōšagruwān Vāhromšāh, Rašid Rostamis Collection at the Fire Temple in Kerman.

V 4060: Dated 1016 AY, 1647 AD, scribed by Mehrabān Anōšagruwān Vāhromšāh, British Library, London.

V 1022: Dated 1022 AY, 1653 AD, scribed by Marzbān Vāhrom, held in Pouladis private collection.

V 4063: Dated 1025 AY, 1656 AD, scribed by Šāhmardān Vāhrom, held in Hosseinis private collection.

V 1044: Dated 1044 AY, 1675 AD, scribed by Marzbān Vāhrom, held at an unspecified place.

V 4158: Dated 1288 AY, 1919 AD, scribed by Mehragān Syāvaxš Frēdōn, held at the library of Parvarešgāh-e Mārkār [Mārkār Orphanage], Yazd.

Vyt 5010: Dated 996 AY, 1627 AD, scribed by Frēdōn Marzbān Frēdōn, held at the First Dastoor Meherjirana Library, Navsari.

Vyt *5020 (K4): Dated 1092 AY, 1723 AD, scribed by Vehmard Frēdōn Vehmard Gōpadšāh, written in Kerman, held at Kongelige Bibliotek, Copenhagen.