Introduction

Foley urinary catheters are commonly used to control posterior epistaxis in most ENT departments. However, there are very few studies of the ideal substance for Foley catheter balloon inflation in this clinical setting; indeed, this catheter has not been designed or licensed for this purpose.Reference Emanuel, Cummings, Fredrickson, Harker, Krause, Richardson and Schuller1 The most common substances used for catheter balloon inflation are air, water and saline. To our knowledge, there is no standard set in the literature regarding evidence for the ideal fluid for catheter inflation, and certainly research in this area is limited.

One study compared water with air, and concluded that water was a better choice than air due to its longer inflation time.Reference McFerran and Edmonds2 Some authors recommend air as the best option, as this avoids the risk of aspiration and, more rarely, the possibility of rupture of the balloon in situ.Reference Hartley and Axon3 Water is preferred to saline by some clinicians, as it has been reported that saline crystallises in the balloon, making deflation difficult.Reference Kirkham and Ho4

We present a study comparing the effects of water, saline and air in maintaining Foley catheter inflation.

Aims

The study aimed to determine the difference in Foley catheter inflation and deflation (active and passive, respectively) when inflated with water, saline or air.

Materials and methods

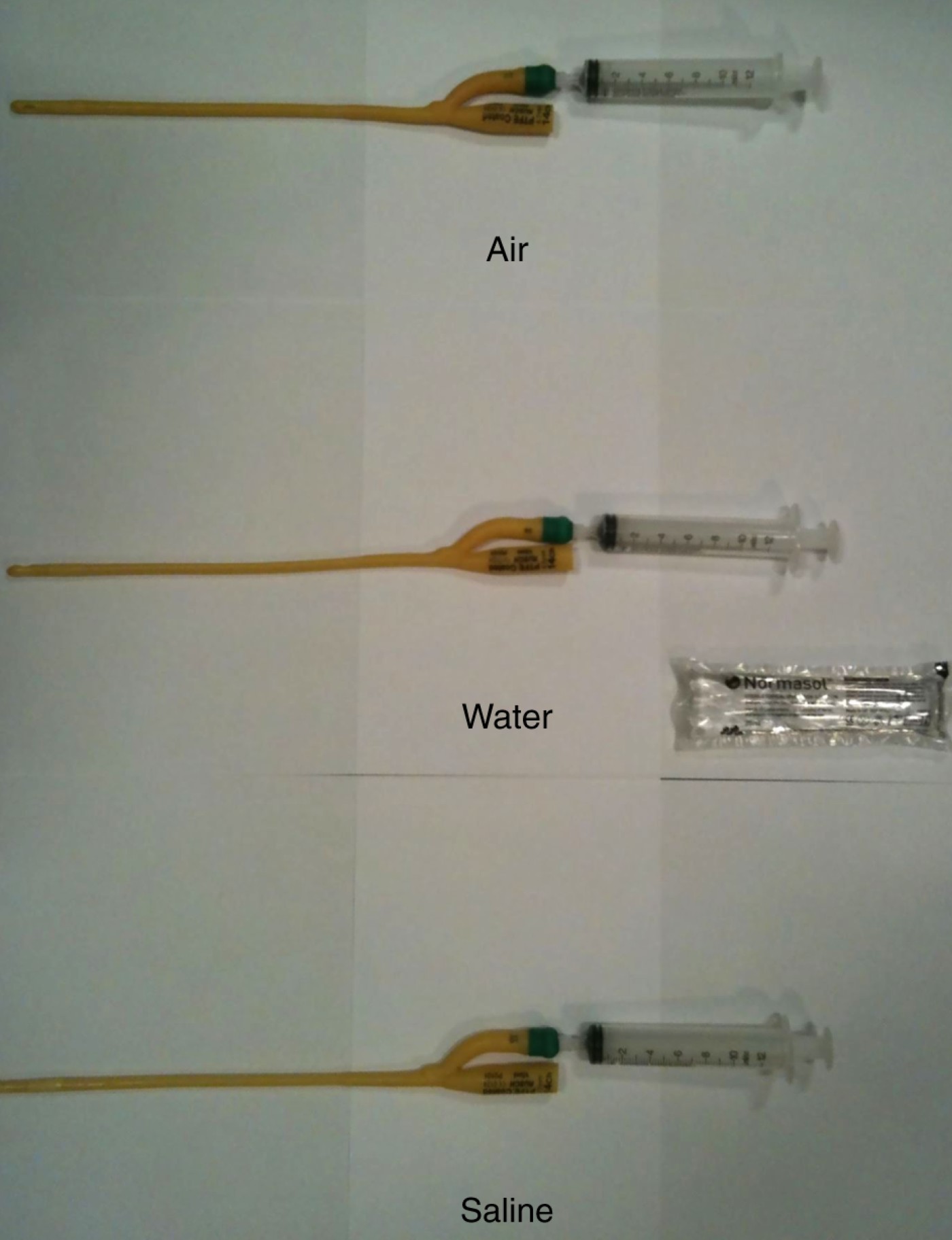

We conducted a prospective, in vitro study of Foley catheters at a district general hospital. Fifteen Foley catheters (size 14 Fr female) were divided into three groups, labelled as water, saline or air, and then filled with 10 ml of the respective substance (Figure 1). The inflated catheters were placed in separate, identical containers. After 48 hours, the balloons were deflated and their contents aspirated and measured (Figure 2).

Fig. 1 Catheters at 0 hours, each inflated with 10 ml of the different filling substances.

Fig. 2 Catheters at 48 hours, showing the amount aspirated for each of the different filling substance.

Results

After 48 hours, the Foley catheters initially inflated with air were found to have completely deflated spontaneously. The mean amount of water and saline aspirated after 48 hours was 8.7 and 8.5 ml, respectively (Table I).

Table I Volume of individual Foley catheters at 0 and 48 hours, for different filling substances

Discussion

Our study shows that air is not suitable for inflating Foley catheter balloons, as all catheters thus filled had spontaneously deflated 48 hours after inflation. In the clinical setting, this may be quite detrimental, as spontaneous deflation may lead to continued bleeding and loosening and extrusion of nasal packing. We detected no difference in the ease with which water or saline could be aspirated from the Foley catheter; however, on average slightly more water was aspirated at 48 hours, compared with saline.

We hypothesise that water is preferable to saline for inflating Foley catheter balloons. However, we recommend a larger, in vivo study to ascertain the benefits of air, water and saline for filling Foley catheters used to curtail epistaxis in the clinical setting.