In the course of the nineteenth century, the once global Portuguese and Spanish empires became third-rate colonial powers. And in the twentieth century, when other imperial nations facing anti-colonial resistance were pushed towards decolonisation, the Spanish and especially the Portuguese fought ferocious, protracted guerrilla wars in order to defend the remains of their empires in Angola, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, and Western Sahara. This narrative of the Portuguese and Spanish dictatorships stubbornly adhering to their last colonies as if they could retain past glories has informed several generations of scholars. Although Portuguese and Spanish “imperial exceptionalisms” have been questioned time and again, accounts of “backwardness” and “irrationality” are long lasting.Footnote 1

What is more, although scholars agree on considering the global course of decolonisation after 1945 to be “one of the most important historical processes of the twentieth century,”Footnote 2 Portuguese and Spanish decolonisation in Africa is still a neglected field in international and comparative scholarly literature.Footnote 3 There is a lack of research on the ends of empires from an “Iberian” perspective that goes beyond traditional political and diplomatic histories. Even though there are obvious differences in scale and scope of the Portuguese and Spanish imperial projects, a shared chronology and entangled imperial rhetorics would suggest the usefulness of a thorough joint analysis.

Yet, scholars often emphasise the differences in scope and objectives between the two Iberian powers and their possessions overseas, neglecting significant overlaps. There are good reasons to focus on the differences, as the mere geographical and economic dimensions of the Portuguese colonies exceeded Spain's entire possessions in Africa.Footnote 4 Furthermore, “Portugal's colonial dimension played an ever-greater role in the country's life and politics” throughout the twentieth century, which finds no comparison in Spain.Footnote 5 Although Francisco Franco and his ideologues were profoundly committed to Spain's alleged calling for Africa (vocación africanista), reaffirmed during and after the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), the small Spanish empire in Africa never attained the political and conceptual weight that it had for the Portuguese dictatorship under António Salazar and Marcelo Caetano. For the Portuguese regime, in contrast, the empire was a significant ideological pillar for its self-conception. As Filipe Ribeiro de Meneses writes, “Empire, ultimately, was a myth through which Portugal's political, economic, and cultural elites could find both common ground and a justification for their role and privileges.”Footnote 6

Having said that, the essays in this issue aim to broaden our perspective by elucidating both the common ground and the dissimilarities of the two Iberian late colonial states in Africa and beyond. Bringing together specialists on Portuguese and Spanish Africa as well as scholars focusing on the domestic impacts of decolonisation to this day, the articles in this issue focus on social change broadly understood, analysed through a historical and anthropological lens.Footnote 7

For the first time, this endeavour brings together questions related to violence and gender, forced migration and administrative internment, as well as current (European) migration regimes in an Iberian perspective. The essays address in different but innovative ways social questions such as how Portuguese and Spanish repressive developmental colonialism triggered migration both within their colonies and beyond. What were the modalities and dynamics of the migration flows? How can we assess the social and cultural impact of forced resettlement and administrative internment on African and migrant societies? How were these policies and processes gendered, and how are they related to migration towards the former metropoles after formal decolonisation? How were the social practices of the Iberian colonial states and their rhetoric of migration and internment linked to other European empires? These and similar questions inform the different essays. The following sections connect these findings with recent research on European imperial nations and the “echoes of empire” in the post-independence nation states.Footnote 8 This brief comparative effort beyond the “Iberian empires” aims to contribute to a better understanding of both the Portuguese and Spanish late colonial states within the realm of European imperialism.

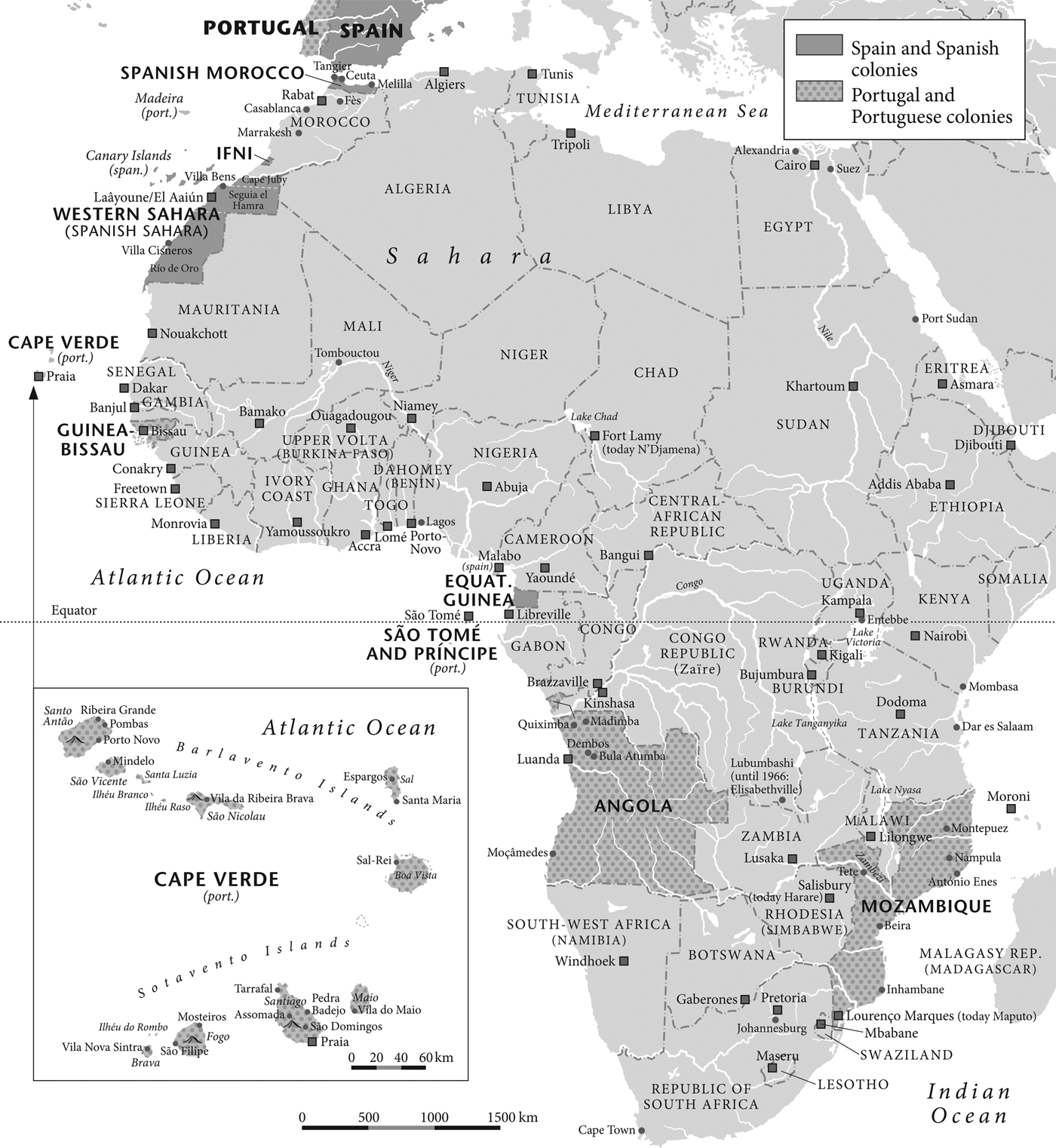

Figure 1. Africa's Iberian colonies, 1950s to 1970s. Map by Peter Palm, Berlin 2019.

Resettlements: “Uplifting” Indigenous Societies

The outbreak of the colonial wars in the Portuguese colony of Angola in early 1961 was also the prelude to a set of legal and social reforms for the empire. Repealing the Estatuto dos Indígenas in 1961, which had institutionalised the legal distinction between “indigenous” and “assimilated” inhabitants of the territories, was among the most important legal changes. Furthermore, Portuguese investment in social, economic, and cultural “development” soared in comparison to earlier years, following the example of other imperial powers since 1945. However, in the Portuguese case these “investments” were an integral part of the counterinsurgency effort, as Miguel Bandeira Jerónimo emphasises in his article. The Portuguese planners’ rural extension and community development concepts, aiming at socio-economical change in both rural and urban areas and (forced) resettlement schemes in war-torn African regions, reflected international discussions and the practices of other European colonial powers.Footnote 9

Indeed, the fundamental character of community development, particularly in rural areas, and related subjects were discussed far beyond the Portuguese colonies. Such programmes allegedly aimed at facilitating access to the state's offer of development (education, health care, loans, economic expertise) in remote regions with scattered populations. In 1964, Alfredo Jorge de Passos Guerra, a Portuguese “specialist” in rural extension and later a participant at a notorious counterinsurgency symposium held in Angola in 1968–69, emphasised corresponding debates in international organisations such as the Food and Agriculture Organisation, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, and the United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, to name only a few of the international bodies concerned with the socioeconomic advancement of developing countries.Footnote 10

However, reference to international debates did not guarantee consistent application or adaptation of international programmes to the conditions in situ. This was especially true for Portuguese notions of community development, as the German agronomist Hermann Pössinger, an “expert” in rural extension, explained in 1968. According to Pössinger, in the 1960s Portugal still pursued programmes in its colonies that had already been considered “unfeasible” in other contexts, mostly due to their “insufficient impact on productivity” in local societies. Overall, outside of Portugal the country was perceived—as was Spain—as a “developing country” in Europe that lacked the resources for modernising its own economy, let alone its African “provinces,” as the colonies were labelled after the constitutional reform in 1951. And yet, international advisers still recognised the Portuguese effort and acknowledged that the development policies pursued in Angola and Mozambique throughout the 1960s and 1970s were at least in part up to date.Footnote 11

Particularly in Angola, the Portuguese government relied on several national and international “experts” with broad experience in implementing rural extension schemes in different parts of the globe.Footnote 12 Nonetheless, some local administrators still claimed that they did not need foreign advisers: from their own “studies and experience” the Portuguese knew best “what ha[d] to be done in [their] ‘house,’” one district official asserted.Footnote 13 It is safe to say that in the Portuguese case there was no lack of conceptual planning linking rural development and integration with security concerns. However, with the ongoing wars in Angola (1961), Guinea-Bissau (1963), and Mozambique (1964), different and clear-cut theoretical concepts for “managing” rural populations were mixed to form an often improvised and hastily implemented repressive developmentalism.Footnote 14

With his focus on the Portuguese army's Operação Robusta in Angola (1969–74), Miguel Bandeira Jerónimo examines these historical processes as if under a magnifying glass. Overlaps between what was called security with socially and economically driven concerns about “development” come to the fore, revealing a high degree of disdain for African populations; the separation of members of forcibly resettled families was only one aspect of the disruptive impact of Portuguese so-called anti-subversive policies.

Forced resettlement in the context of anti-colonial warfare was nothing new. As a repressive practice, it had long figured in the imperial toolbox of colonial powers, from the Spanish in Cuba to the US in the Philippines and the French and the British in Algeria and Kenya respectively. Deployed as a repressive resource since the mid-nineteenth century and explicitly linked to social engineering after 1900, it had time and again led to humanitarian disasters. Mozambique and Angola, where about 15 to 20 percent of the total population, or one million people in each of the two colonies, had been resettled during the wars of the 1960s and 1970s, were no exception in this regard.Footnote 15

And yet, the belief that resettlement was a strategy that would ultimately be successful persisted, not only among members of the military. As the London Daily Mail explained to its readers in the early 1970s, in Mozambique population transfers to new villages “could be the key to breaking the back of the Frelimo [Mozambique Liberation Front] insurgency.” It was argued that concentrating civilians “deprives the guerrillas of food, shelter, porters, recruits, and communications that they can now get from the tribal villages.”Footnote 16 Besides this military objective, the “new villages” were intended to transform indigenous societies allegedly “in one jump from stagnant tribalism into the modern world of education, communication, [and] cash economy.” The mere scope of the endeavour seemed impressive. As one journalist stated in 1973, “It must be the biggest organised shift of population that Africa has ever seen.” Despite the humanitarian disaster that forced removals in a large scale had brought to the colonial world and beyond since the late nineteenth century, the confidence in big planning was the normal course of things among most modernising societies and particularly European (colonial) powers, at least since the early 1950s.Footnote 17

However, research on strategic resettlement in the Portuguese and Spanish empire has been limited to date and would no doubt benefit from new perspectives, for example including in the picture the exodus of rural populations towards urban centres triggered by accelerated social change and especially by the wars. The rural populations in the war-torn districts of Mozambique and Angola had to deal with the dangers posed by combat in the countryside and the impacts of Portuguese scorched-earth policies, which involved the destruction of livestock and other property that could be used by the guerrillas. This compounded the effects of the fundamental socioeconomic changes of the 1960s and 1970s, which had already in their own right resulted in continuously rising levels of migration to urban centres, challenging people to adapt to a new lifestyle in the cities.

In Angola and Mozambique, colonial and urban planners called for a “Reordenamento suburbano” in order to guarantee hygiene and “integration” in the peripheries, though they also pointed to the lack of funding for measures to improve conditions in rapidly growing suburban slums. By providing new amenities, including cultural facilities, the Portuguese aimed to engineer a sense of belonging in both the new districts and the new villages. This was meant to ease the transition for the allegedly rapidly de-tribalised new urban and hamlet dwellers.Footnote 18

This brief outline of social questions like the dynamics of urbanisation and rural resettlement highlights the difficulties of drawing general conclusions about forced migration in a “colonial situation”Footnote 19. In this respect, micro-historical approaches to war-related migration are of crucial importance for a critical re-examination of the widespread perception of strategic resettlements and populations shifts and subsequent indigenous reactions. Generally, Portuguese aldeamentos in Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau were infamous for bad planning, as Bandeira Jerónimo's contribution highlights. “In construction”—indicating that a project had not been completed—is one of the most frequent phrases to be found in the colonial records on resettlements. A report from the Portuguese secret police in Montepuez (Cabo Delgado) in northern Mozambique on the early stage of resettling about two hundred thousand “natives” characterised the overall situation as “critical.” Overcrowding and poor sanitary conditions together with a lack of medical care and inadequate access to drinking water led to epidemics of diseases with high death rates, especially among children, such as measles, influenza, and whooping cough.Footnote 20

At the same time, Portuguese propaganda on the aldeamentos in Montepuez stressed the successes achieved with measures intended to improve the social and economic situation of different “tribes.” There were even lasting improvements in interethnic relations, as one propagandistic report emphasised. In short, resettlement in aldeamentos was widely advertised as a “miracle.”Footnote 21 Still more research in provincial archives and oral interviews is needed to enhance our understanding of the dynamics of living conditions in Portuguese new villages during the wars. Everyday life in the aldeamentos and the security situation changed over time and depended on the course of the war in each region as well as on other factors. Sometimes, people who had initially fled an area and even crossed the border returned later in the war to live in the designated (new) villages, often motivated by new job opportunities that emerged in and around Portuguese military bases. Economic opportunities were occasionally an important pull-factor.Footnote 22

“Concentration camps or free communities? For punishment or protection?” This simplistic and crude question about the nature of the aldeamentos was raised at the time, allegedly in search of a better understanding of the resettlement schemes in Mozambique and Angola. One journalist's answer was that “it depends on whom you listen to,” pointing to the (global) propaganda efforts of both the anti-colonial movements and the colonial power.Footnote 23 Although the sources can be assessed from a certain distance, developing a better understanding of the dynamics of (forced) imperial migrations is a task that still warrants further efforts by scholars.

Engendering (Forced) Migration and Administrative Internment

In his article, Alexander Keese explores the entangled histories of what was referred to as development, social protests, workers’ migration, and anti-colonial resistance within the social debates in Santo Antão, Cabo Verde. Keese enhances our understanding of social and anti-colonial protests on the archipelago, introducing different perceptions of a variety of colonial subjects—landowners, tenants, and sharecroppers—and the entanglements of their struggles over natural resources, most importantly water. Natural disasters such as droughts cast a long shadow on social debates on the islands.

Keese presents a wide array of causes of social unrest on the islands, with inequality under Portuguese colonialism one factor among others. The islanders’ hope for independence was closely connected to expectations that social reforms would be implemented. Particularly the poorer tenant farmers were looking forward to a fairer distribution of and access to natural resources after independence. The increasing level of repression in the Portuguese Empire due to the colonial wars in Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau also had repercussions in Santo Antão. A mix of “controlled repression” and colonial reform, as well as the elite's reluctance to support popular movements, is likely to have kept the islanders from engaging in armed rebellion.Footnote 24

Yet, with an outdated dictatorship at home and the wars in continental Africa, the Portuguese faced anti-authoritarian and anti-colonial criticism on a nearly global scale.Footnote 25 As early as the 1930s, soon after the Salazar dictatorship had been established, critics had denounced the notorious Tarrafal detention facilities on Cabo Verde as a concentration camp. This charge resurfaced during the imperial wars, when the Portuguese “new villages” in the colonies were denounced as “no better than concentration camps.”Footnote 26 Surprisingly, the Spanish—who only a few years earlier had openly referred to the internment camps for Sahrawi on the Canary Islands as “concentration camps” (campos de concentración)—were rarely the target of specific anti-colonial criticism in this regard.Footnote 27 Spain and its small empire in Africa were apparently only of minor importance.Footnote 28 What was known in the Spanish newspapers at the time as “the incident” or “the occurrence of Ifni and Sahara” was viewed in Spain as well as abroad as one of the usual “small wars” and hardly made it into the international news. Even today, the imperial war of Ifni-Sahara (1957–58) and anti-colonial protest in Western Sahara are at times “trivialised” in scholarly assessments.Footnote 29

In fact, as Enrique Bengochea and Francesco Correale show in their article, we should consider this struggle to be a full-scale imperial war, which included mass bombardments and forced removals, and had long-lasting impacts on the local societies—although on a smaller scale than the Portuguese colonial wars. The joint Spanish and French war effort in the Sahara early in 1958, especially the coordinated airstrikes, destroyed nomads’ livestock and led to an unprecedented refugee crisis. In the border areas of Spanish Sahara and Mauritania, the colonial powers employed the imperial tool of forced removals of civilians and created “free-fire zones.”Footnote 30 Furthermore, the Spanish referred to deportations of “suspicious” Saharawi to the concentration camps in Las Palmas and Fuerteventura on the Canary Islands, located only a few miles off the coast of Ifni and Western Sahara.Footnote 31

The war triggered a second phase of colonisation and “development” comparable to that pursued in French and British colonies after 1945, and in the Portuguese possessions in the 1960s.Footnote 32 After having completely destroyed the livelihood of the rural population, Spain embarked on a peculiar kind of “welfare colonialism,” co-opting traditional male elites with financial support and handouts.Footnote 33 Nevertheless, the “second conquest” aimed at the same time to exploit the territory economically. Pressuring the nomads to adopt a sedentary lifestyle became a central issue for the colonial government. This was meant both to guarantee better control of the population and to provide a stable workforce, for example for the fishing and tourist industries, and for (future) exploitation of the rich phosphate deposits at Bou Craa. Housing projects flourished, particularly in the capital of Laayoune. Still, the construction of new units could not keep up with the pace of urbanisation. Improvised huts in the suburbs of Laayoune mushroomed, and the Spanish colonial administration repeatedly tried to control these informal constructions, but with little success.Footnote 34

Time and again the local administration ordered the destruction of huts in the suburbs of Laayoune and transferred the new urban dwellers to prefabricated government houses, mostly citing poor hygiene to justify their actions.Footnote 35 Just as in Madrid or Barcelona and in Luanda or Benguela, where the authorities also faced the impacts of rapid socioeconomic change, the Spanish colonial government targeted the growing “slums” (chabolismo), complaining about a “lack of knowledge” and a “lack of culture” or of a lack of “morals and religion” in the suburbs.Footnote 36 Daily inspections and subsequent destruction of shacks involved a notable degree of violence and met with protest, especially by Sahrawi women. Reports pointed to the “determined opposition” of the female suburban dwellers, who refused to move and tried to defend their living space.Footnote 37

As Bengochea Tirado and Correale argue, the newly built apartment complexes required adequately “educated” women who would implement Spanish concepts of domesticity. Therefore it is no coincidence that Sección Femenina (SF), the dictatorship's official Spanish women's organisation, debated the path towards a sedentary lifestyle for Sahrawi women at its 1966 national assembly. As early as the mid-1960s, the SF developed plans to obtain furniture for the “new native houses.”Footnote 38 The Spanish women's organisation (similar to its Portuguese counterpart, the Mocidade Portuguesa Feminina) was part and parcel of the late effort to stabilise the empire or at least to smooth the transition from formal to informal control in the African territories. Women were seen as cultural mediators, and as a key to the domestic spaces of indigenous societies, whether in the Iberian, the British, or the French empire.Footnote 39 The intersection of women's organisations with education, development, and modernisation and the overlaps with counterinsurgency paradigms show that these organisations and their programmes have to be included in our analysis to gain a better understanding of the Iberian late colonial states.Footnote 40

Enduring the impacts of (forced) migration and administrative internment often resulted in different experiences for the two sexes, be it for children or for adults. This is true in cases of resettlements, as in the Aldeamento Messumba at Lake Malawi in Mozambique, where in 1967 the 3,124 internees included 1,054 women and 1,629 children (however, the absence of men due to migrant work was a characteristic of many villages long before the wars).Footnote 41 As Susana Trovão and Sandra Araújo show in their article, administrative internment behind the frontlines often targeted cultural minorities, as was the case in Mozambique in the wake of the Goa crises from 1961 until 1971. The colonial state ruthlessly interned, dispossessed, and expelled from Mozambique parts of its community of Indian nationals and people of Indian descent. What can be seen as a retaliatory measure against the republic of India in the wake of the occupation of Goa and the capture of more than three thousand Portuguese soldiers and civilians reveals upon closer examination a wide array of inner contradictions of Portuguese late colonialism.

On the one hand, the internment of more than two thousand Indian citizens, including men, women, and children, in ten camps throughout Mozambique and the dispossession of the property and assets of more than a thousand businesses and families clearly shows the limits of the alleged multiracial and pluri-continental nation that Portuguese colonial propaganda repeatedly emphasised.Footnote 42 On the other hand, Trovão and Araújo shed new light on the unequal and gendered power structures that characterised both Portuguese colonialism and family relations in the Indian community in Mozambique. Their article highlights how women of Indian descent made their voices heard by appropriating new spaces in religious life—frequently spaces that had previously been occupied by now absent men—rather than through overt revolutionary action.

Overall, dispossession and deportation from Mozambique affected, first and foremost, poorer Indian families. The Indian traders who owned large import-export companies were a vital element of the Mozambican economy; hence, the colonial state opened up new paths to citizenship for them. Others instead chose to again migrate, sometimes laying the foundation for further transnational business networks.

However, such success stories are presumably an exception among the many individuals and groups forced to migrate in colonial and post-independence times. As Yolanda Aixelà-Cabré argues in her article, female post-independence migrants from Equatorial Guinea to Spain, the former colonial power, had to deal with a particular set of cultural challenges that often resulted in social invisibility and precarious lives on the margins of the Spanish nation. Nevertheless, time and again, post-independence migration turned imperial notions of “centre” and “periphery” upside down. Or as Alice, an Afro-Mozambican migrant, put it upon arriving in Lisbon: “This is Lisbon? Gosh, Lourenço Marques is more magnificent” (Isto é Lisboa? Puxa, meu rico Lourenço Marques).Footnote 43

Perspectives: Towards Iberian Migration Regimes

As the essays collected here suggest, aside from all the peculiarities of each case explored, several strands not only connect the two Iberian late colonial states but also refer to shared imperial and post-independence trajectories of other (former) empires. Both dictatorships integrated their African colonies into the respective Iberian nation-state as provinces in the 1950s, as France had done with Algeria much earlier. On a cultural and discursive level, a pervasive rhetoric of inclusion that fostered the fiction of harmonious multiethnic and multicontinental nations characterised both Portuguese and Spanish colonial discourse. This so-called Portuguese Luso-tropicalism and its Spanish counterpart, Hispano-tropicalism, highlighted the allegedly mild form of Portuguese and Spanish colonialism that did not aim for (economic) exploitation and that attributed to the Iberian nations a unique genius with special skills for adapting to the tropics and a special ability to assimilate native peoples.Footnote 44 The belief that “the Portuguese always and anywhere knew how to create [a] bond that truly connects people” proved to be persistent.Footnote 45 Equally persistent was the conviction that Spain “pursued the inclusion” of its African colonial subjects “in a decent and modern life, according to the altruist principles of Christian morals.”Footnote 46 Again, tales of colonial exceptionalism were common currency in other empires, too, and the tenacity of these concepts—not only in Portugal and Spain—in part even to this day, can be understood as a remnant of the enduring imperial legacies that still shape our world. Iberia is not a case apart in this respect, as Elizabeth Buettner has shown in her comparative approach on European decolonisation and its aftermaths: Great Britain, France, the Netherlands, and Belgium all face different but nevertheless related challenges when dealing with their imperial pasts.Footnote 47

In her concluding essay for this issue, Buettner's focus is on the multiple Iberian migration systems since the era of decolonisation. In times of the financial and economic crisis that relentlessly affected the two Iberian countries after 2008, migration to both the former empires and other European countries became again conceivable alternatives for many Portuguese and Spaniards. Hence, Buettner calls for examining postcolonial and intra-European migrations together in a single analytical framework—a task awaiting further scholarly scrutiny.

Acknowledgements

The preparation of this special issue was possible thanks to generous funding from the Hamburg Foundation for the Advancement of Research and Culture. I am highly indebted to Paula Bradish (Hamburg) who did an outstanding job in preparing each of the essays for publication. Furthermore, I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for comments and suggestions and the authors for their commitment and patience throughout the publication process.