For better or worse, Idi Amin is among Africa’s most recognizable heads of state.Footnote 1 Four decades after his removal from power and exit from public life, it is difficult to name another Ugandan who has captured global attention and remained such a divisive figure on the sustained scale that Amin has. As scholars have long noted, the caricatures of Amin that circulated abroad in the 1970s were shaped by many external factors: the activism of Ugandan exiles, Cold War geopolitics, and Western racist stereotypes, among others.Footnote 2 At the same time, Amin’s prominence in the public imagination in Uganda and abroad is also the enduring result of the image-making work in which his government was deeply engaged.Footnote 3 To an extent that exceeded other African governments, the architects of the Amin regime diligently archived images, sound recordings, and documents, creating a historical record that was meant to shape both scholarly and popular interpretations of Amin’s presidency. The Amin regime sought to make history.

The recent cataloguing and ongoing digitization of more than 60,000 photographic negatives taken by cameramen – they were all men – working under Amin’s Ministry of Information offers scholars an unparalleled resource for studying the Amin government’s practices of self-presentation. The 60,000 negatives from Amin’s tenure are part of a larger archive at Uganda’s public broadcaster, the Uganda Broadcasting Corporation (UBC), which now houses the television, radio, and photographic units where Amin’s photographers once worked. The larger archive consists of roughly 85,000 negatives spanning from the early 1950s until 1997. In 2018, the UBC’s managing director Winston Agaba launched a partnership between the UBC, the University of Michigan (UofM), and the University of Western Australia (UWA) that has thus far digitized nearly 50,000 negatives, several video reels, and dozens of audio recordings from the 1950s through the 1990s, with the majority coming from Amin’s rule from January 1971 to April 1979. The digitization of the photographic negatives, which are under the UBC’s copyright control, was carried out by graduate students from Makerere University’s School of Library and Information Science, Edmond Mulindwa and Jimmy Kikwata, working under UBC archivists Malachi Kabaale, Jacob Noowe, and Dean Kibirige. This newly available photographic archive joins a larger ensemble of newly catalogued paper archives – held at the Uganda National Archives (UNA) and at several district government centers around Uganda – which together enable research into the Ugandan state under Amin through the lens of its own documentarians. Meanwhile, public institutions, including the UBC, the UNA, the Uganda Museum, and Makerere University, continue to preserve and make accessible important historical materials. This work promises to generate new forms of public history that have long been impeded, blocked, or actively foreclosed.Footnote 4

Aggressive Populism

Following the coup of 25 January 1971, Idi Amin declared his new military regime to be a “government of action,” a mantra that reflected an aggressive populism that guided his regime until its overthrow in April 1979. Amin attempted to reorient how Ugandans understood and acted in public life through a combination of persecution and exhortation. Addressing social issues from trade to public cleanliness as military campaigns, his regime produced a proliferation of purge categories – domestic and foreign enemies subject to violence of various forms. Categories as diverse as Asians, smugglers, and rebels were all targeted by public campaigns that subjected thousands of people to expulsion, imprisonment, torture, and in some cases execution.Footnote 5 Others were encouraged to position themselves as productive citizens by self-identifying according to categories laid out by the state. Capacious groupings including “elders,” “women,” “youth,” and “Muslims” were all summoned in public announcements demanding representatives avail themselves to government authorities. In an effort to compensate for crumbling public infrastructures and to encourage production to provide government with valuable foreign exchange, Amin’s regime attempted to reorganize Ugandans’ relationship with the state.

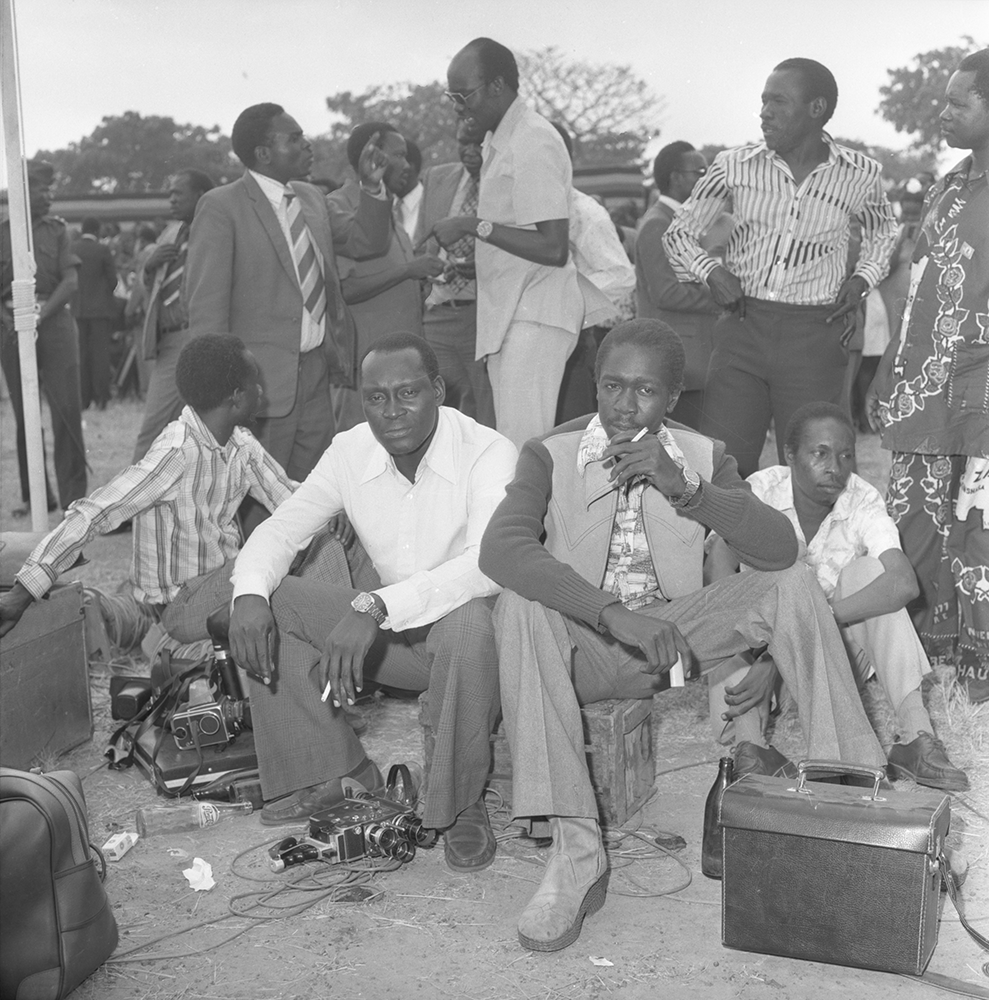

It was through media – with cameras, microphones, transmitters, and newspapers – that Amin’s officials worked to transform Ugandans’ connection with their government. Milton Obote, whom Amin served and subsequently overthrew, had inherited state media from the British Protectorate that were designed to be used as a tool for promoting the (supposedly) apolitical project of development and technocracy.Footnote 6 Under Amin, Uganda’s official media infrastructure afforded novel uses in the service of populism. Within this wider media apparatus, photography offered the most potent means of staging the punishment or encouragement of particular groups. Images from the UBC’s archive show alleged smugglers assembled for the camera beside jerrycans of oil and sacks of flour. Other packets show Asian men beside stacks of cash. The staging of such occasions for the camera made the evils of magendo (smuggling) and usury visible. The contexts of economic collapse that led people to such activities were erased. These scenes cast government functionaries as dispensers of justice expunging any trace of their own complicity in illicit trade, raiding state coffers, or otherwise sustaining ordinary Ugandans’ economic deprivation. Many images deflect Uganda’s economic and political dependency on Cold War alliances by situating Amin’s regime as a vanguard of global anti-colonial and pan-African solidarity during visits by dignitaries ranging from Yasser Arafat to Louis Farrakhan and Queen Mother Moore, among many others (see Figure 1). Photography helped produce the appearance of strength and moral clarity in the service of Amin’s government. The staged appearance of militaristic strength (see Figure 2) deliberately obscured how most ordinary Ugandans experienced military rule.Footnote 7

Figure 1. 4848-008, “H.E. Meets Queen Mother Moore at Imperial Hotel,” 28 July 1975. Digital scan of 35mm black and white negative. Reproduced courtesy of the Uganda Broadcasting Corporation.

Figure 2. 5464-012, “Katwe Salt Project Foundation Laid by H.E.,” 19 January 1977. Digital scan of 2×3 cm black and white negative. Reproduced courtesy of the Uganda Broadcasting Corporation.

Photography was ever-present in state functions (see Figure 3), but the photographs taken by Amin’s cameramen were rarely seen, even by those who took them. Very few photographs were ever printed, and the archive itself remained out of public view, making the UBC collection a largely unseen archive. The photographers brought in their film to an office at the UBC, where it was developed and the negatives were placed in envelopes, carefully numbered and labeled, usually with a date and the name of the event where they were taken. A few photographs did achieve iconic status abroad and within Uganda. For example, Amin and Ministry of Information officials sported t-shirts emblazoned with an image of a staged event during which European businessmen carried Amin aloft in the mode of a colonial explorer (see Figure 4). However, the UBC collection was not a propaganda archive in the narrow sense, as it was not for public consumption. It was the creation of a media apparatus geared primarily toward the memorialization of momentous events in public life. This apparatus enabled constant editing and reframing of the regime’s legacy. The photographers routinely weeded out images that were out of focus or that showed Amin in an awkward pose. There were also more systematic purges, sometimes of hundreds of envelopes, such as in the aftermath of the 1976 Israeli raid on Entebbe airport, where security officers spent weeks purging images of sensitive events, including those of public executions. The only images of death that remain – showing the execution of Sergeant Arukanjeru Baru in 1973 – were evidently missed because the number on the envelope was inexplicably six months out of sequence.Footnote 8 The archive’s creators and editors were primarily documentarians: it was their task to make a lasting record of the great events of the age glorifying Amin’s government, all housed securely within the photographic unit’s offices.

Figure 3. 5980c-2-037, “Military Take Over Celebrations at Koboko,” 25 January 1978. Digital scan of 2×2 cm black and white negative. Reproduced courtesy of the Uganda Broadcasting Corporation.

Figure 4. 6344-3-023, “Victory Rally,” 17 September 1978. Digital scan of 2×2 cm black and white negative. Reproduced courtesy of the Uganda Broadcasting Corporation.

There were other reasons, beyond their professional responsibilities, for government photographers’ reluctance to bring their work to publication. Photography was a dangerous endeavor in 1970s Uganda. Relying on fear and exhortation rather than democratic consensus, Amin’s government was dependent on its capacity to direct what they wanted Ugandans to see. Rumor and uncertainty over the fate of disappeared individuals could serve to intimidate fearful Ugandans.Footnote 9 However, knowledge about the backstage intrigues of statecraft was also fraught with danger, as Amin’s soldiers murdered investigative journalists, exerted stricter editorial control over the press, and declared war on those they deemed “confusing agents” who did not sufficiently exalt Amin’s achievements.Footnote 10 For those assigned to photograph the state’s public face, missteps could prove fatal or lead to involuntary exile. After one of the unit’s photographers Jimmy Parma sold a colleague’s photos of the aftermath of the Israeli raid on Entebbe airport to the South African Drum magazine, both he and the messenger who had delivered the negatives were picked up and murdered. Soon afterwards, security operatives occupied the photo unit and destroyed negatives of which they disapproved. The risks of official photography were both institutional and personal.Footnote 11

Like government paper archives, the infrastructure surrounding the UBC collection’s preservation did not facilitate easy public circulation.Footnote 12 The collection was meticulously labeled and preserved in a secure room accessible only to a select number of people. From this secure base, it was largely absent from public life. Just two dozen photos made their way into the government newspaper Voice of Uganda. Prior to 1976, a few photographers engaged in the risky but profitable trade of selling negatives to foreign agencies. But while a few individual images made their way into public view, the archive itself remained physically closed to public access, guarded by its producers against circulating in ways displeasing to Amin and his associates. The mere existence of the archive as a record of government activity exerted more power under Amin’s regime than the images it contained, which were uniquely well-curated but visible to almost no one.

Archives and Public History

Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, archivists in Uganda have been pursuing a number of projects that make previously inaccessible archives available for research. The Church of Uganda worked with Yale Divinity School to organize and digitize its archive. The UNA was catalogued in its entirety by a team of government archivists and post-graduate students from UoM and Makerere University. District archives in Kabale and Jinja have been catalogued by students from Busoga University, Kabale University, and UoM. And in western Uganda, Mountains of the Moon University has been working with UoM and the Center for Research Libraries to digitize local government archives in Kabarole and Hoima. At the time of writing, the digital archive at Mountains of the Moon University consists of 500,000 scans, the largest collection of digitized government documents in Africa.Footnote 13 Separately, Ugandan public and private institutions have been pursuing projects to digitize their photographic collections. For example, the Ham Mukasa Foundation worked with the University of Adelaide and Makerere University to digitize its collection of many hundreds of historic photographs.

As with Uganda’s paper archives, the photographic archive of the UBC has been preserved through decades of political disruption and institutional decay. This is a tribute both to the work of civil servants on the margins of Uganda’s public institutions and to the relative neglect that political interests have exhibited toward archives of all sorts in Uganda since the 1970s.Footnote 14 Until the spread of digital cameras in the late 1990s, government photographers continued to use the same numbering and labeling system begun in the 1950s. As the photo unit transitioned to born-digital images, the physical negatives from decades past were stored away in a filing cabinet and largely forgotten.

In 2015, UBC archivist Mr. Malachi Kabaale reopened the cabinet, and three weeks later Dr. Vokes and UBC Managing Director Mr. Winston Agaba identified that its contents were the product of Amin’s official photographers. The UBC subsequently launched a digitization project in 2018 with UofM, which was joined later that year by UWA. Mr. Agaba and Mr. Kabaale, in particular, recognized that these materials were both historically significant and a valuable resource for the UBC’s programming. In addition to the 60,000 negatives from the 1970s, there are over 10,000 negatives and prints from the 1950s and 1960s and over 10,000 more from the 1980s and 1990s. During this work, the research team has also uncovered several hundred audio reels and around 100 film reels, mostly from the 1970s.

The transformation of the neglected cabinet into a catalogued and digitizable archive required a combination of expertise from archivists, historians, and technicians. After securing a climate-controlled room, Mr. Kabaale, Mr. Noowe, Mr. Mulindwa, Mr. Kikwata, and Dr. Taylor renovated the cabinet for safer storage, created new envelopes for loose negatives, and produced a catalogue based on the existing numbering system with metadata from the original envelopes. Tom Bray, a converging technologies consultant from UofM, assisted with setting up the scanner and establishing protocols for its use. Prior to scanning, all of the negatives were counted, cleaned, and their condition evaluated. The humid storage space had caused some negatives to fuse together, though most separated after several months in the air-conditioned work room. Given the volume of images, Kabaale and Noowe identified specific envelopes and topics of particular value to the UBC, while Taylor, Peterson, and Vokes, in conversation with Abiti, identified additional subjects of historical significance in anticipation of an exhibition at the Uganda National Museum in 2019.

In addition to technical and academic expertise, the digitization of these historical negatives also required the institutional knowledge of UBC staff. As the scanning proceeded over eight months in 2018 and a further five months in 2020, members of staff from across the UBC informed archivists of boxes, envelopes, and drawers filled with negatives, prints, and other historical artifacts that had been housed away in other offices over the years. The preservation of this material, despite adverse infrastructural conditions, suggests how localized modes of storage and preservation on the margins of a large bureaucracy sustained sensitive materials throughout periods of political and institutional uncertainty. As Uganda’s national broadcaster, the UBC has taken particular interest in documenting and preserving national heritage, starting with its own archives. This combination of localized archival practice and institutional commitment works against stories of decay, neglect, and dysfunction that dominate Ugandan public discourse as much as academic assessments of public institutions in the Global South. Indeed, such stories have, in the past, attached to the UBC itself.

A similar story can be told of Uganda’s official paper archives, which have survived thanks to the largely unrecognized work of archivists and records officers across the country. The advent of structural adjustment programs in the midst of armed conflict in the 1980s left many government archives poorly funded and under-resourced. Nevertheless, archivists and records officers in upcountry districts continued to navigate the personal, professional, and political risks of maintaining records that document contentious and difficult pasts. It is largely thanks to the repair work of such dedicated civil servants that Uganda’s government archives have avoided the purges that have characterized collections elsewhere.Footnote 15 The UNA – which moved from Entebbe to a new building next to the Ministry of Health in Wandegeya, Kampala, in 2016 – contains thousands of catalogued files dating back to the early 1900s. Until the Covid-19 pandemic, the UNA had also been collecting archival material from government ministries and up-country districts. The collections at the UNA, which are accessible to anyone with research clearance from the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology (UNCST), are full of fascinating material on the workings of local government and national politics, as well as on the intersection of the state and public life in twentieth-century Uganda.Footnote 16

For scholars and those interested in public history, the audiovisual materials at the UBC and the archival collections at the UNA suggest possibilities for new forms of scholarly engagement with histories of the Ugandan state. The four authors of this article – whose professional expertise includes museum studies, history, and visual anthropology – worked to bring a small selection of the UBC’s photo collection to public view with an exhibition, The Unseen Archive of Idi Amin: Photographs from the Uganda Broadcasting Corporation, which ran from May to December 2019 at the Uganda National Museum before moving briefly to Idi Amin’s home district of Arua and then to a permanent gallery in Soroti in the east of the country in early 2020. A version of the exhibition, Picturing Idi Amin: Photographs from the Uganda Broadcasting Corporation, also ran from October to November 2020 at the Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery at the University of Western Australia in Perth. In 2022, a version of the exhibition will also be installed at Uganda’s largest private museum, the Igongo Cultural Centre near Mbarara. All of the exhibitions showcase a selection of images as well as a brief audiovisual display using selections of video and radio material in the UBC’s collections.

The UBC materials open exciting curatorial possibilities, even as they impose their own constraints. As curators of The Unseen Archive of Idi Amin, we have strived to deprive the photos of their “propagandistic” content by incorporating images that hint at the violence of the period, including portraits of individuals who were murdered by Amin’s soldiers. However, we have also attempted to keep visible the genuine enthusiasm with which many Ugandans embraced the Amin government’s populism at the time. Before installing the exhibition, we held participatory workshops at Makerere University and in rural southwestern Uganda where participants responded to images and offered ideas on how to exhibit them without reinforcing their proclamatory power. The exhibition’s opening week events also involved another workshop with scholars from Makerere and other institutions, which generated important critical analysis of the display and possibilities for future work with the photographs.Footnote 17 Moreover, the exhibitions offered occasions for public events in which Ugandans who had played significant roles in government and media – or as victims of state violence – could frame the images in the context of their own experiences. In Kampala, we organized three panel discussions over three days among the following panelists: former government ministers Henry Kyemba and Edward Rugamayo; former media practitioners in the 1970s, including former director of Uganda Television Aggrey Awori, former director of Political Programs at UTV Al Hajj Nzereko Abdul, former Kasese District Information Officer Dick Kasolo, and freelance photographer Elly Rwakoma; and a “victims panel” consisting of Phoebe Luwum, the daughter of murdered archbishop Janani Luwum, Sarah Bananuka, the daughter of former UPC Ankole district chairman Nekemiah Bananuka, and Rajni Tailor, who left Uganda following Amin’s expulsion of the Asian community. The panels were broadcast on UBC television.

We view these exhibitions as part of a wider conversation about the forms of public history that are possible within Uganda’s public institutions. For curators and staff at the Uganda National Museum, the exhibition and related events contributed to ongoing discussions about how to bring new narratives of critical heritage studies into the colonial museum space, whose permanent collections were mostly designed prior to independence. The museum has used the occasion to re-engage with the Ugandan public in order to enable future curatorial work on contested national histories in Uganda. The Soroti exhibition is housed in one of Uganda’s new regional government museums. There are plans for an exhibition on the 1960s at the National Museum. Curators are also discussing possibilities for reimagining and renovating permanent exhibitions despite the limited availability of resources. The exhibition in Perth offered an opportunity for members of the Ugandan diaspora in Australia to respond to the material. Meanwhile, the Amin exhibition and selections of the UBC images will be moving outside the museum, both to the Igongo Cultural Centre, and in a book of photography.Footnote 18

The UBC’s photo archive offers an important resource for scholars and all Ugandans to study and analyze the internal workings and self-imaging of Amin’s government. As we have argued, these images cannot be viewed uncritically as truthful representations of life as most people experienced it in the 1970s. They do not tell us much about the everyday lives of ordinary Ugandans. Nor do they exhibit the scale of violence and cruelty of Amin’s dictatorship.Footnote 19 Like written documents, they require critical analysis of the context of their creation and the motives of their producers. It is such critical focus that scholars across disciplines, particularly from Uganda’s public universities, can bring to this important collection.

Idi Amin’s rule remains a contested presence in Ugandan public life, invoked frequently as an object of nostalgia for racial economic nationalism, a source of social degradation, and a reservoir for conspiracy theories.Footnote 20 Official attitudes towards Amin have preferred to bypass such multivalent debate through an emphasis on violence and trauma. Some have proposed monetizing foreign interest in Amin through so-called dark tourism with museums or tourism trails that would cater to Westerners’ fascination with racist mythologies around the former president. Within Uganda, Amin’s rule is an increasingly visible reference point in debates over postcolonial sovereignty and state power. His charismatic populism has generated nostalgia among many younger Ugandans in a global context of populist authoritarianism. For others, the violence and trauma of life under military rule makes such longing unthinkable. The absence of any monument or public space devoted to Amin’s regime or its victims has tended to maintain the isolation of these various invocations of Amin’s memory.

As a national historical resource on a still-unsettled period of Uganda’s postcolonial history, the images and audiovisual material discussed here are controlled by the same government institution that produced them, or what is now named the UBC. The collection’s continuous institutional position within the UBC reflects the resilience of Uganda’s public institutions under challenging circumstances. Scholars or members of the public interested in using particular images may write to UBC Archivist Malachi Kabaale at kabaalem29@gmail.com indicating the file numbers to be consulted and the day on which the user intends to visit the UBC.Footnote 21 At present, there is a small fee for using images for personal or academic purposes and a higher rate for commercial uses.Footnote 22

Scholars, particularly those working from Ugandan universities and public institutions, have a unique role in informing conversation around the 1970s, which remains a deeply contested period of Ugandan, African, and global history. Studying Amin’s government by critically analyzing the artifacts of its own administration and self-imaging promises to help shape academic and popular knowledge on the Ugandan state and Ugandan public life for years to come.