Introduction

Patients referred with two-week wait or urgent suspicion of cancer to head and neck cancer services are put through an urgent, fast-track system. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) advises that urgent suspicion of cancer referrals should be seen within two weeks of initial referral from their general practitioner.1–3 The Scottish Government recommends that all patients referred via the urgent suspicion of cancer pathway should receive initial treatment within 62 days of receipt of referral, with a maximum of 31 days between initial diagnosis and start of treatment.4

With a growing incidence of head and neck cancer,5 there has been increasing pressure on the urgent suspicion of cancer pathway and difficulty achieving Scottish Government targets. Guidelines suggest 95 per cent of urgent suspicion of cancer patients should be achieving the recommended targets, but in 2019, 84.4 per cent of urgent suspicion of cancer referrals received treatment within 62 days of referral.6 In 2020, this increased to 92.8 per cent, but this improvement may be falsely reassuring because there was a 55 per cent decrease in the number of urgent suspicion of cancer head and neck referrals following the coronavirus 2019 (Covid-19) pandemic.Reference Taylor, Omakobia, Sood and Glore7

The traditional assessment pathway for an urgent suspicion of cancer patient involves an out-patient clinic appointment with flexible transnasal endoscopy, followed by imaging and panendoscopy in the operating theatre under general anaesthetic or an operating room biopsy. Any areas that are suspicious for malignancy are biopsied intra-operatively to gain histopathological diagnosis. After imaging and biopsy are completed, the patient is referred to the multidisciplinary team (MDT), where the patient is staged using the tumour–node–metastasis classification, and the team discusses management options and treatment intent.

In-office biopsy of suspicious lesions is an alternative technique used to take histopathological samples. In-office biopsy can be carried out during the initial out-patient clinic consultation, without requiring operating room resources. In-office biopsy is effective in detecting head and neck cancer, with a sensitivity rate of 77.8 per cent and specificity rate of 95.1 per cent.Reference Cohen, Bishara, TRushin and Benyamini8 Patients with diagnosis at in-office biopsy can be referred directly to the MDT without waiting for an operating theatre space, and this may have a subsequent impact on cancer pathway times.9

The aim of this systematic review was to assess the current evidence on the safety and impact of in-office biopsy on cancer waiting times. We will also review evidence about cost-efficacy and patient satisfaction for in-office biopsy.

Materials and methods

A literature search was conducted in December 2020 by the authors and the National Health Service (NHS) Library Service. The databases included were: Cinahl, Cochrane Library, EmBase, Medline, Prospero, PubMed and Web of Science. The search was filtered to only include articles published from 2010 to 2020 and in the English language. The search strategy (Appendix 1) was used and adjusted for each database. The results were exported to EndNoteTM reference management software and duplicates were removed. Ethical permission was not required as no original research was conducted.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were created and used in the review of the results. The authors included articles about adult patients (over 16 years old) and patients who had undergone endoscopic biopsy for a malignancy of the head and neck. Articles were excluded if the biopsies were conducted for benign conditions or oral malignancies and if the article did not contain original data (e.g. commentaries, correspondence, single case reports). Two authors carried out independent title and abstract reviews of the search results following Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (guidance, flow diagram shown in Appendix 2).Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman10

Results

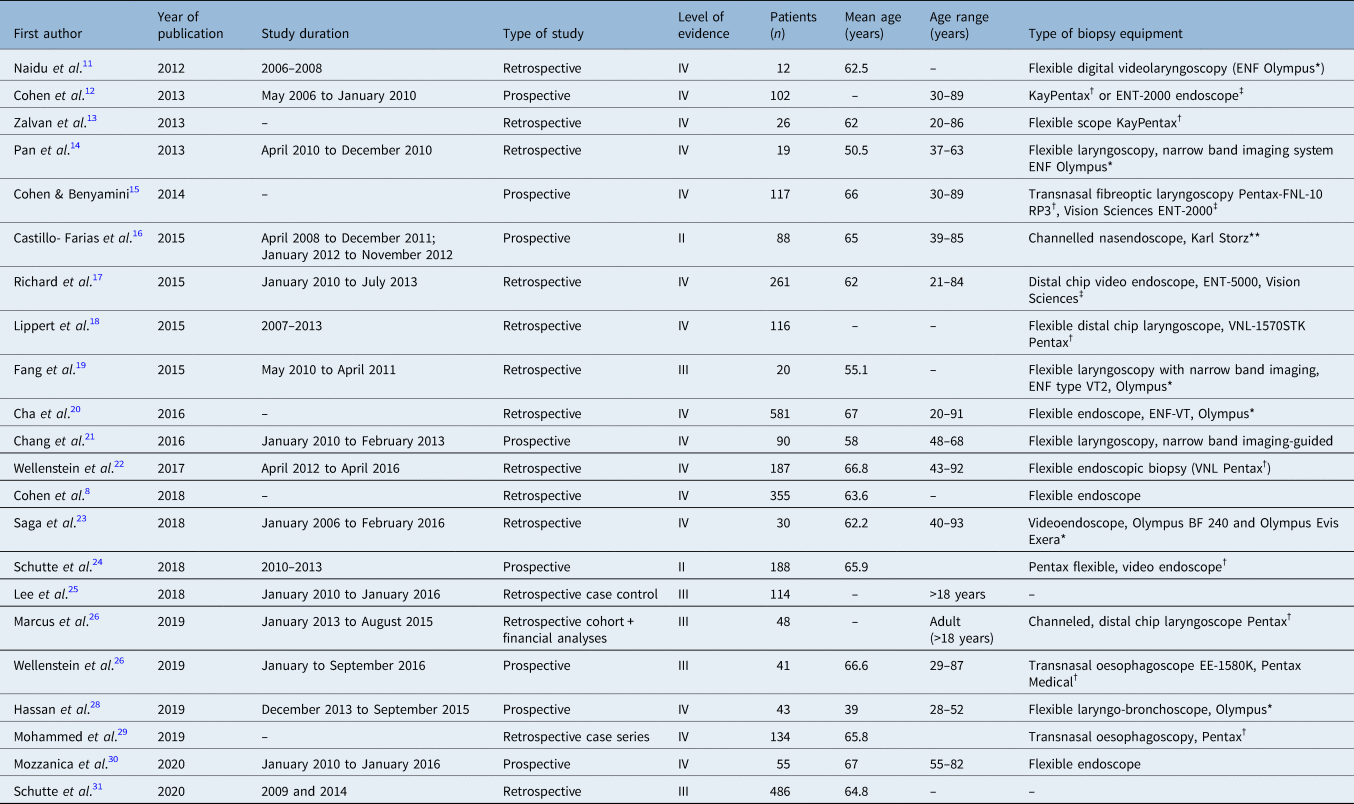

There were 19 741 search results from the literature search. Two additional papers that were not identified from our literature search were found from reading around the literature and added to the list of titles. Search results were uploaded to EndNote and duplicates were removed, leaving a total of 16 535 papers for title review. Two authors independently carried out title screening and excluded 16 437 papers. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion and consensus. A total of 98 abstracts were independently screened, and from this 27 full articles were reviewed. A total of 22 articles were included in the final systematic review; these are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of the papers included in the systematic review

*Olympus, Tokyo, Japan; †Pentax, Tokyo, Japan; ‡Vision Sciences, Orangeburg, New York; **Karl Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany

Discussion

Safety

Tolerability

Tolerability is a key outcome measure for in-office biopsy. It has implications for adequate tissue acquisition and patient satisfaction. As defined by Lippert et al., tolerability is ‘the ability to obtain a piece of tissue for pathological analysis’.Reference Lippert, Hoffman, Dang, McCulloch, Hartig and Dailey18 Cohen and Benyamini demonstrated an association between poorly tolerated procedure and insufficient tissue sample for diagnosis.Reference Cohen and Benyamini15 Tolerability may be subject to individual operator skill and successful application of local anaesthesia. Other factors such as patient selection and biopsy subsite have been linked to tolerability. For example, Mohammed et al. highlighted that most procedures that were abandoned because of patient intolerance were biopsies for glottic lesions.Reference Mohammed, Del Pero, Coates, Masterson, Tassone and Burrows29 Lippert et al. also specify difficulty obtaining biopsies of the true vocal folds as well as the laryngeal surface of the epiglottis.Reference Lippert, Hoffman, Dang, McCulloch, Hartig and Dailey18

Across the studies, only a very small proportion of patients did not tolerate the procedure as shown in Table 2. There were 23 cases of procedure abandonment because of poor tolerability in the 2272 patients considered (less than 1 per cent). More research may be beneficial to objectively assess tolerability, including standardisation of reporting. However, all studies were aligned, and demonstrated an overall high degree of tolerability associated with in-office biopsy.

Table 2. Summary of papers discussing tolerability

Complications

Complications of in-office biopsy are of significant interest because patient safety is paramount. Any concern regarding risk of airway-threatening events is likely to limit where in-office biopsy can be safely performed and therefore limit its utility. Table 3 summarises the papers that included comment on complications. Thirteen studies report none. Most complications reported were minor, self-limiting and required no intervention. Only Wellenstein et al.Reference Wellenstein, deWitt, Schutte, Honings, van den Hoogen and Marres22 reported serious complications requiring intervention. Most significantly, there was one case of laryngeal oedema, in the context of a large, bilateral, glottic mass, which required intervention in the form of urgent tracheostomy scheduled the following day.

Table 3. Summary of papers discussing complications

*Intervention required

Other complications requiring management included anterior epistaxis requiring topical 0.1 per cent xylometazoline to arrest, and laryngeal bleeding following injection of topical anaesthesia through the cricothyroid membrane. This was managed by subcutaneous injection of adrenaline around the cricothyroid membrane. One patient suffered post-procedure dizziness and hypotension which improved following administration of intravenous fluids.

The issue regarding whether in-office biopsy can be undertaken safely in patients on anticoagulation medicine is raised by three studies. Castillo-Farias et al.Reference Castillo-Farias, Cobeta, Souviron, Barbera, Mora and Benito16 discuss the disadvantage of in-office biopsy in terms of potential delayed time to diagnosis by the need to defer the procedure. In contrast, Wellenstein et al.Reference Wellenstein, deWitt, Schutte, Honings, van den Hoogen and Marres22 and Schutte et al.Reference Schutte, Takes, Slootweg, Arts, Honings and van den Hoogen24 did not require anticoagulation to be withheld prior to in-office biopsy. They report that no bleeding complications occurred. They conclude that anticoagulation medication is not a contraindication to in-office biopsy, which can still be safely performed. The authors do not provide details such as total numbers of anticoagulated patients undergoing in-office biopsy or information regarding specific subtypes of anticoagulation medication. Therefore, this would be an area of interest for further research.

The studies in these papers do not comment on complications associated with operating room biopsy, which, while being the current ‘gold standard’ for tissue diagnosis, is neither risk nor morbidity-free. In particular, patients with overt, advanced, airway-threatening head and neck malignancy may undergo a high-risk general anaesthetic for the purpose of tissue diagnosis. At least 1.6 per cent of patients undergoing panendoscopy require unplanned tracheostomy, and another proportion undergo planned local anaesthetic tracheostomy to secure the airway, potentially resulting in a lengthy hospital stay.Reference Eissner, Haymerle and Brunner33 In many cases, after confirmation of the initial clinical diagnosis, the histopathology does not influence further management, which is best supportive care for 21 per cent of patients.Reference Timon and Reilly34

The Lancet recently published an international consensus on the management of head and neck cancer in the setting of ‘acute resource constraint’, for example, as a consequence of the Covid-19 pandemic. In a situation whereby a healthcare institution is suffering severely reduced staffing and operating room and in-patient capacity, the consensus recommends that if a biopsy can be performed under local anaesthesia, no panendoscopy is required.Reference Schimberg, Wellenstein, van den Broek, Honings, van den Hoogen and Marres35 Given that in-office biopsy is sufficient to make a diagnosis in the context of potential harms because of resource constraint, one might also consider the potential avoidable harms, and ethics, of general anaesthesia in high-risk patients where in-office biopsy could provide the same diagnosis.

Cost analysis

Cost analysis of in-office biopsy versus operating room biopsy has been studied in a number of papers (see Table 4) seeking to calculate the potential savings associated with avoiding the operating room. There were eight studies that explored the cost efficacy of out-patient biopsy. Four of these studies were based in the USA or Taiwan and thus are limited in their transferability or relevance to the UK healthcare system. In particular, there is some variability in what costs were reported. Much of the financial analysis from the USA and Taiwan studies is centred on ‘billable costs’, ‘opportunity costs’ and ‘reimbursement rates’ by insurance companies. There is less discussion regarding the actual cost of the resources involved. Reimbursement rates tend to be based on the outcome of price negotiations between insurers and healthcare providers, taking into account the clinical and economical value of the treatment.Reference Mehanna, Hardman, Shenson, Abou-Foul, Topf and AlFalasi36 Therefore, they are not as reliable a surrogate of cost efficacy than an analysis based on actual hospital costs. Despite this, all studies evaluating cost agreed that in-office biopsy required fewer resources and was cheaper than operating room biopsy.

Table 4. Summary of papers discussing cost analysis

Four studies were of European provenance (Netherlands and Spain) and therefore of potentially increased applicability. The European studies suggested significant cost savings of between £658 and £1420 per patient undergoing in-office biopsy in lieu of operating room biopsy. One paper makes the point that even after accounting for negative biopsies requiring additional diagnostic procedures, including operating room biopsy, savings in this range were still possible.Reference Schutte, Takes, Slootweg, Arts, Honings and van den Hoogen24

The cost analyses of Castillo-Farias et al.,Reference Castillo-Farias, Cobeta, Souviron, Barbera, Mora and Benito16 Saga et al.Reference Saga, Olalde, Larruskain, Alvarez and Altuna23 and Schutte et al.Reference Schutte, Takes, Slootweg, Arts, Honings and van den Hoogen24 were limited by the absence of actual financial data collected. Instead, they provided projections of savings based on data generated from estimated resource costs. In comparison, Wellenstein et al.Reference Wellenstein, Honings, Schutte, Herruer, van den Hoogen and Marrers26 was a prospective cost analysis study with the aim of investigating the feasibility of office-based biopsy. It collected costs based on actual resources used in the assessment of 41 patients, accounting for any unexpected variation. The results of this higher quality study supported the findings of the earlier work performed in this area, highlighting savings of up to €831 (£720) per procedure.

Despite a relative lack of standardisation and robust methodology across the studies looking at cost, in-office biopsy is consistently found to be cheaper and less resource intense than operating room biopsy. This remains constant across a variety of healthcare systems in different parts of the world.

In 2018, The Scottish Health Technology Group published a budget impact analysis of in-office biopsy versus operating room biopsy from an NHS Scotland perspective. They assessed that the initial investment cost of flexible endoscopic equipment could be offset by the savings made through in-office biopsy within a 5-year time period, and savings of £420 000 every year thenceforth.37 Higher quality, prospective cost analyses based on the UK healthcare system would be of particular value to evaluate the precise business case for in-office biopsy, although the authors do not believe this would challenge the trend highlighted by previous studies.

Waiting times

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence and the Scottish Referral Guidelines for Suspected Cancer mandate that patients should expect a diagnosis of head and neck cancer within 31 days of referral and to commence treatment within 62 days.4 Diagnosis and decisions regarding treatment can only be made following tissue acquisition and subsequent histopathological confirmation of cancer. Delays to diagnosis and treatment in head and neck cancer have been strongly associated with poorer outcomes including increased mortality. One particular study demonstrated a tumour-volume doubling time in head and neck cancer of 30 days for a cohort of patients with the most aggressive disease. They also demonstrated that 34 per cent of patients showed radiological progression of disease within 28 days.Reference Timon and Reilly34 Therefore, minimising avoidable delays is essential to optimising patient outcomes as well as compliance with these targets.

Four studies in our review produced complete data comparing time to diagnosis and time to treatment. The results were concordant in demonstrating reduced time to diagnosis associated with in-office biopsy (2.0–7.5 days) versus operating room biopsy (9.0–23.0 days). Three studiesReference Richard, Sugumaran, Aviv, Woo and Altman17,Reference Schutte, Takes, Slootweg, Arts, Honings and van den Hoogen24,Reference Schutte, van den Broek, Steens, Hermens, Honings, Marres and Markx31 also demonstrated reduced time to treatment for in-office biopsy (21.0–27.0 days) with respect to operating room biopsy (34.0–48.8 days).

In contrast, as seen in Table 5, Lee et al.Reference Lee, Smith, Chandarana, Matthews, Bosch and Nakoneshny25 did not find any significant difference for time to treatment, despite observing a reduced time to diagnosis by 15.5 days with in-office biopsy. They account for the loss of this initial advantage of in-office biopsy by a combination of system factors and referral bias. In their practice, patients in the operating room biopsy arm can be discussed by the MDT if they have undergone fine needle aspiration positive biopsy without having had a confirmed primary tumour or having yet undergone panendoscopy. They also suggest delays associated with dental consultations and fitting for custom radiotherapy head and neck moulds as also potentially skewing the results.

Table 5. Summary of papers discussing patient waiting times

Furthermore, it is important to note that in addition to in-office biopsy, Schutte et al.Reference Schutte, van den Broek, Steens, Hermens, Honings, Marres and Markx31 also introduced combined MDT clinics at the initial consultation. These involved head and neck surgeons, oncology and other allied healthcare professionals. Although in-office biopsy was considered a main intervention for their ‘optimised work-up program’, their results should not be considered in a pure in-office biopsy versus operating room biopsy context.

Overall, in-office biopsy has been consistently shown to significantly reduce time to diagnosis. The majority of studies go further to demonstrate that this also leads to earlier initiation of treatment. With this evidence demonstrating that treatment can be initiated up to 26 days sooner and that disease progression and upstaging can occur in over a third of patients within 28 days, it is clear that in-office biopsy has great potential to expedite and improve oncological outcomes.Reference Jensen, Nellemann and Overgaard32 In fact, Schutte et al.Reference Schutte, van den Broek, Steens, Hermens, Honings, Marres and Markx31 found 3-year overall survival to be 12 per cent higher in the cohort of patients that underwent in-office biopsy and commenced treatment on average 13 days sooner.

Clearly, this is a key area of interest and warrants further investigation and research. The argument linking in-office biopsy, reduced waiting times and improved survival would be strengthened by larger, more highly powered, prospective studies, with a narrow focus on in-office biopsy versus operating room biopsy while controlling for other variables.

Patient satisfaction

Standardised measurements of patient satisfaction have been infrequently published in the literature; it is more common for satisfaction to be informally reported. Mohammed et al.Reference Mohammed, Del Pero, Coates, Masterson, Tassone and Burrows29 studied 134 attempted transnasal oesophagoscopy biopsy procedures of the upper aerodigestive tract, most commonly of the glottis and tongue base. The authors commented that they were unable to carry out 19 of the attempted procedures and reported that 13 of these patients refused to have a further in-office biopsy and were subsequently referred for operating room biopsy. However, reasons for patient refusal or measurement of patient experience were not reported.

Table 6 shows the two papers from the systematic review that measured patient experience. Wellenstein et al.Reference Wellenstein, Honings, Schutte, Herruer, van den Hoogen and Marrers26 used the visual analogue scale (VAS) to measure patient experience for 35 patients following in-office biopsy. The VAS asked patients to rate their experience from 1 to 10, with 1 being the least unpleasant to 10 being the most unpleasant, and a mean score was calculated for each domain. Mean VAS score was 1.9 for nasal pain when inserting the endoscope and 1.7 for throat pain throughout the procedure. Patients were also asked to score on inconvenience because of gag reflex, nausea and burping, and mean scores were 1.5, 0.3 and 2.2, respectively. These results give an indication that patient experience of in-office biopsy is well tolerated.

Table 6. Papers discussing patient experience

Schutte et al.Reference Schutte, van den Broek, Steens, Hermens, Honings, Marres and Markx31 compared patient experience in the conventional pathway with operating room biopsy against optimised pathway with in-office biopsy. A total of 139 patients were given a questionnaire, the Consumer Quality Index for Oncological Care, to rate their experience of the conventional or optimised pathways. Scores were significantly higher in the patients in the optimised pathway group. The introduction of the in-office biopsy in the optimised pathway may have contributed to the higher Consumer Quality Index scores, but satisfaction regarding in-office biopsy was not independently measured.

• In-office biopsy is safe, with most articles reporting only minor and self-limiting complications

• Patient tolerability of in-office biopsy was good, with a procedure abandonment rate of less than 1 per cent

• In-office biopsy is cost-effective, with all papers demonstrating a cost saving

• In-office biopsy improves treatment pathway times, with faster time to diagnosis and initiation of treatment

• There is little evidence on patient satisfaction of in-office biopsy compared with operating room biopsy

• In-office biopsy is an effective alternative to operating room biopsy and has a number of advantages

The literature lacks evidence regarding patient experience of in-office biopsy. The small number of quantitative questionnaire studies give an insight that patient experience of in-office biopsy is positive. Anecdotal comments on patient satisfaction can provide interest to the reader, but the literature needs further evidence of patient experience using standardised measurement.

Limitations

The main limitation of this systematic review was concerning the quality of evidence, and the fact that most of the primary articles included were retrospective cohort studies. This category of evidence is at risk of bias, particularly in patient selection and would be classified as lower in quality compared with randomised controlled trials. Patients in the cohort studies were also poorly matched with regards to factors such as biopsy site, specific type of equipment used and skill-level of the clinician performing the procedure. Discrepancies in these variables could affect the complication rate of in-office biopsy procedures.

Conclusion

This review of the literature has found in-office biopsy to be reported as a safe procedure, with very few serious complications documented in the current evidence. Moreover, it is well tolerated, with procedure abandonment occurring in fewer than 1 per cent of cases. Utilisation of in-office biopsy can lead to significantly faster times to diagnosis and treatment. This may have important implications for oncological outcomes and warrants further investigation. There is a lack of evidence about patient satisfaction comparing in-office biopsy versus operating room biopsy, and although initial results are positive, it remains an area of interest for further study. In-office biopsy has been consistently shown to be a highly cost-effective alternative to operating room biopsy across a variety of healthcare systems throughout the world.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde Library Network and University of Glasgow Library Services for their support and advice.

Competing interests

None declared

Appendix 1. Search strategy for systematic review

Appendix 2. Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram