Introduction

When we think about twentieth-century dance and the return to Ancient Greece, the images that most readily come to mind are likely to be of Isadora Duncan standing in Greek costume with arms held beseechingly upward or striking a pose reminiscent of classical friezes. One might also recall a tableau from Vaslav Nijinsky's Ballets Russes production of L'Après-midi d'un faune (1912), with its nymphs in tunics gliding across the stage in friezelike formations. Or one might remember Michel Fokine's ancient Greece–inspired Narcisse (1911) and Daphnis et Chloé (1912) or George Balanchine's Apollo (1928), all created for Diaghilev's Ballets Russes. Duncan and the choreographers of the Ballets Russes have long been credited with having revitalized ballet in France through explorations of movement and gesture that evoked ancient Greek dance. In the early 1900s, however, the person most often cited in the theatrical press as ushering in a new era for French ballet through dances inspired by ancient Greek imagery was the renowned French choreographer Madame Mariquita (ca. 1838–1922).

This article calls into question established narratives of ballet modernism by shedding light on Madame Mariquita's Greek ballets. When Mariquita died in 1922, critics paid homage in droves, publishing dozens of obituaries and eulogies in the daily and theatrical press that celebrated her remarkable creativity. Critics hailed her as a great artist who, with her “extraordinary imagination,” “incomparable science,” and “perfect taste,” had “brought new life to the ballet,” and “revitalized” the art form. She had “allied the grace of classical ballet with the plastique of modern ballet,” “renovated gesture and costume,” and brought “truth to dance.” All thought “she would be remembered forever,” and that “her name would remain attached to the history of dance, which she renewed.”Footnote 1 Although the eulogies mentioned several types of dances that Mariquita had created throughout her lifetime, recalling the many highlights of her boulevard-theater or music-hall career and reminiscing over favorite divertissements in Opéra-Comique operas, the theater critics lavished disproportionate praise on a series of ballets created for the Opéra-Comique between 1899 and 1912 that derived their costumes, steps, poses, and movement aesthetic from ancient Greek artifacts and imagery.

Mariquita's obituaries point to a significant story—one that has been lost to dance history. The French theatrical world in the early twentieth century recognized that Mariquita's Greek ballets had been a catalyst for French ballet modernism. Now overshadowed by the legacy of Duncan and the Ballets Russes, Mariquita was instrumental in fostering a vogue for Greek dance before Duncan, Fokine, and Nijinsky appeared on the French stage. Her ballets are central to understanding dance in Paris at a pivotal moment in dance history, and to understanding early modernism.

Nascent Modernism

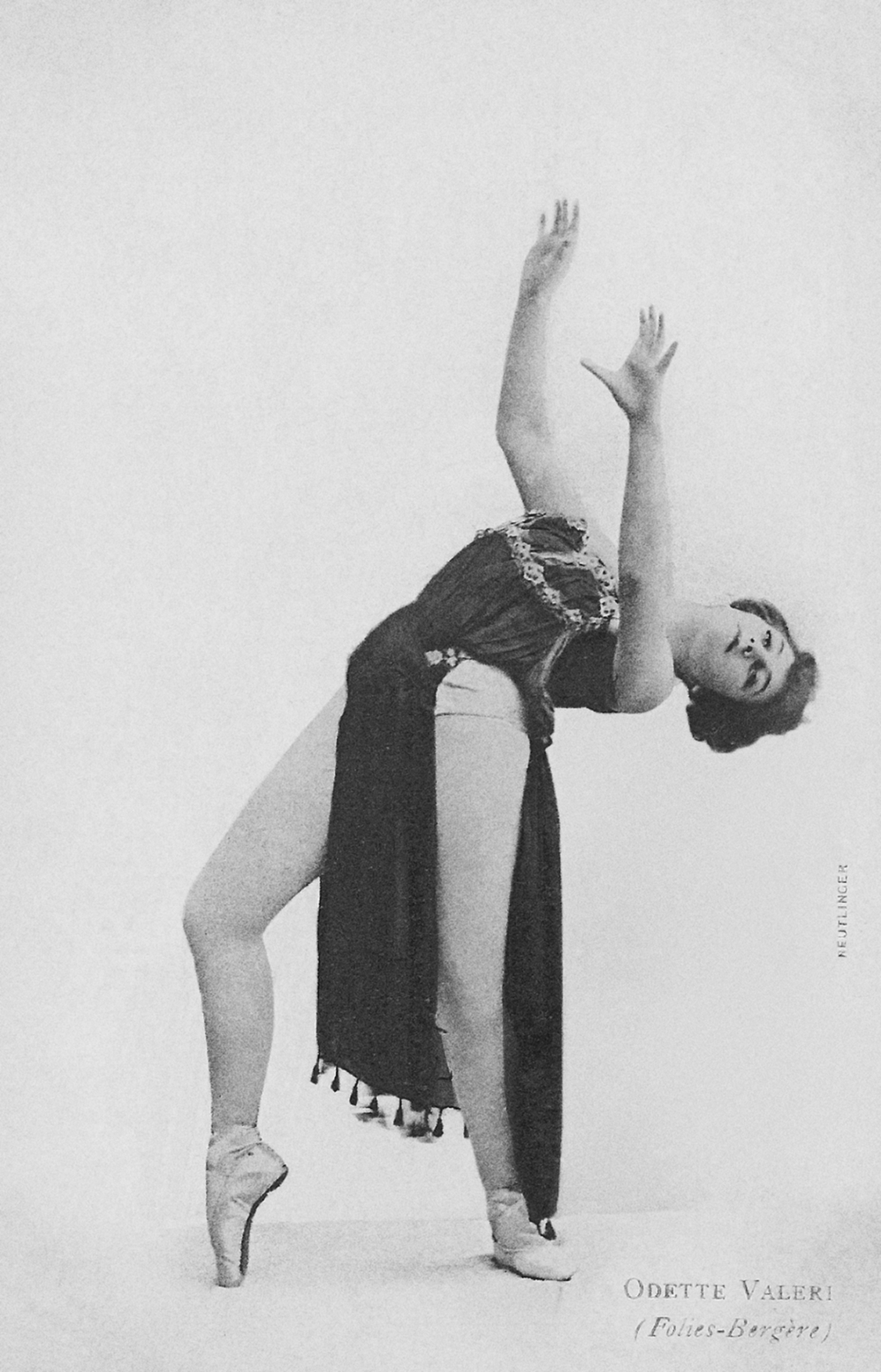

Mariquita's Greek ballets for the Opéra-Comique represent the pinnacle of an astonishing corpus of innovative choreography. Her career as a choreographer had already spanned thirty years when she began exploring Greek dance. She had created ballets in an impressively wide variety of genres and styles for more than a dozen different theaters, including the Théâtre du Châtelet and the Théâtre de la Gaîté in the 1880s and 1890s, and the Folies-Bergère in the 1890s and 1900s (Gutsche-Miller Reference Gutsche-Miller2015). Her years as the ballet mistress of the Folies-Bergère music hall had been especially creative and had marked her first departures from the conventions of post-Romantic pantomime ballet: her choreographies for productions of Une répétition aux Folies-Bergère (1890), Fleur de Lotus (1893), and Chez le couturier (1896), for instance, mixed ballet with circus-style slapstick, striptease, or other trendy forms of visual entertainment; Les demoiselles du XXe Siècle (1894) and Sports (1897) presented characters in contemporary dress performing everyday activities; and Émilienne aux Quat'z’arts (1893) and Lorenza (1901) parodied current affairs and cultural mores. Mariquita had a keen eye for new approaches to movement and a gift for incorporating these novel modes of dancing into ballet, and her music-hall productions required a range of movements and gestures that went beyond the traditional ballet vocabulary (Photo 1).Footnote 2 Although Mariquita's music-hall ballets were never avant-garde, in their parodic elements, contemporary dress, and mix of academic and popular dance forms these ballets contained many of the incipient characteristics of what later bloomed into a full-fledged ballet modernism.

Photo 1. Reutlinger, Odette Valéry in La Princesse au Sabbat (1899), possibly drawing on music-hall performances of belly dancing, in Les Feux de la Rampe, Revue des Théâtres 5, no. 84. Bibliothèque nationale de France, GD-48073.

In these same years, Mariquita began publicly voicing concerns about the stagnation of French dance, which she attributed to the Paris Opéra's reliance on the stilted and acrobatic technique of academic ballet.Footnote 3 Her pronouncements were understated, recorded by critics trying to elicit a few comments from a woman they all described as reluctant to speak to the press. However, Mariquita's frustration with current training, technique, and performance practices grew increasingly urgent. In 1901, she affirmed that the decline of ballet in Paris was real and of great concern, declaring that “ballet lacked art, good teachers, and great dancers …” and that it “had given way to so-called virtuosity, the prosaic technique of dancing.”Footnote 4 Spectacle, too, was “killing” ballet, with its overreliance on decorations and costumes.Footnote 5 In 1905, Mariquita again bemoaned the decline of ballet in an article published simultaneously in Le Pays, La Petite Presse, and La France, and once again she blamed the Opéra and its empty “acrobatic” virtuosity. She later described wanting to free the body to express or embody thoughts and feelings without physical constraints, and spoke of going her own way, of having “an irresistible penchant for independence.”Footnote 6 She also credited Loie Fuller's Folies-Bergère performances of serpentine dances with opening her eyes to new possibilities of movement.Footnote 7

No longer interested in what she felt were outdated forms of ballet, Mariquita set out to find a new vocabulary of movement with which to bring dramatic narratives to life. She found the solution to her impasse in ancient Greek dance. Perhaps something in the gestures and poses of figures on ancient museum artifacts sparked Mariquita's imagination and inspired her to use the body in new ways: Greek dance may have offered both the physical emancipation and artistic significance she craved. It also allowed her to break with ballet's traditional male-scripted narratives and highly gendered movements and gestures. Her first forays into choreographing Greek dance were nevertheless tentative, often incorporated into larger works. She created what critics termed “archaic” dances for an 1897 revival of Rameau's Castor et Pollux at the Bruxelles Grande-Place in 1897; some “charmingly archaic” dances in her restaging of Phryné at the Folies-Bergère in 1897; an “Ionian” dance to music by Vincent d'Indy for Sarah Bernhardt's performances of Médée at the Théâtre de la Renaissance in 1898; and a ballet titled Le Modèle with music by George Pfeiffer for the Cercle Volney in 1899, described as “Greek in costume and Parisian in inspiration.”Footnote 8 She also choreographed some ancient Greece–inspired dances in her inaugural ballet for the Opéra-Comique, a mythological parody titled Le Cygne staged in 1899.Footnote 9 Although these dances were fleeting, they caught the attention of critics, who noted with delight that the nymphs “looked like living Tanagra-statuettes” and that the faun “reproduced with a precision—perhaps desired, perhaps unconscious, but to the loveliest effect—some well-known attitudes of fauns dancing on antique vases or bas-reliefs.”Footnote 10

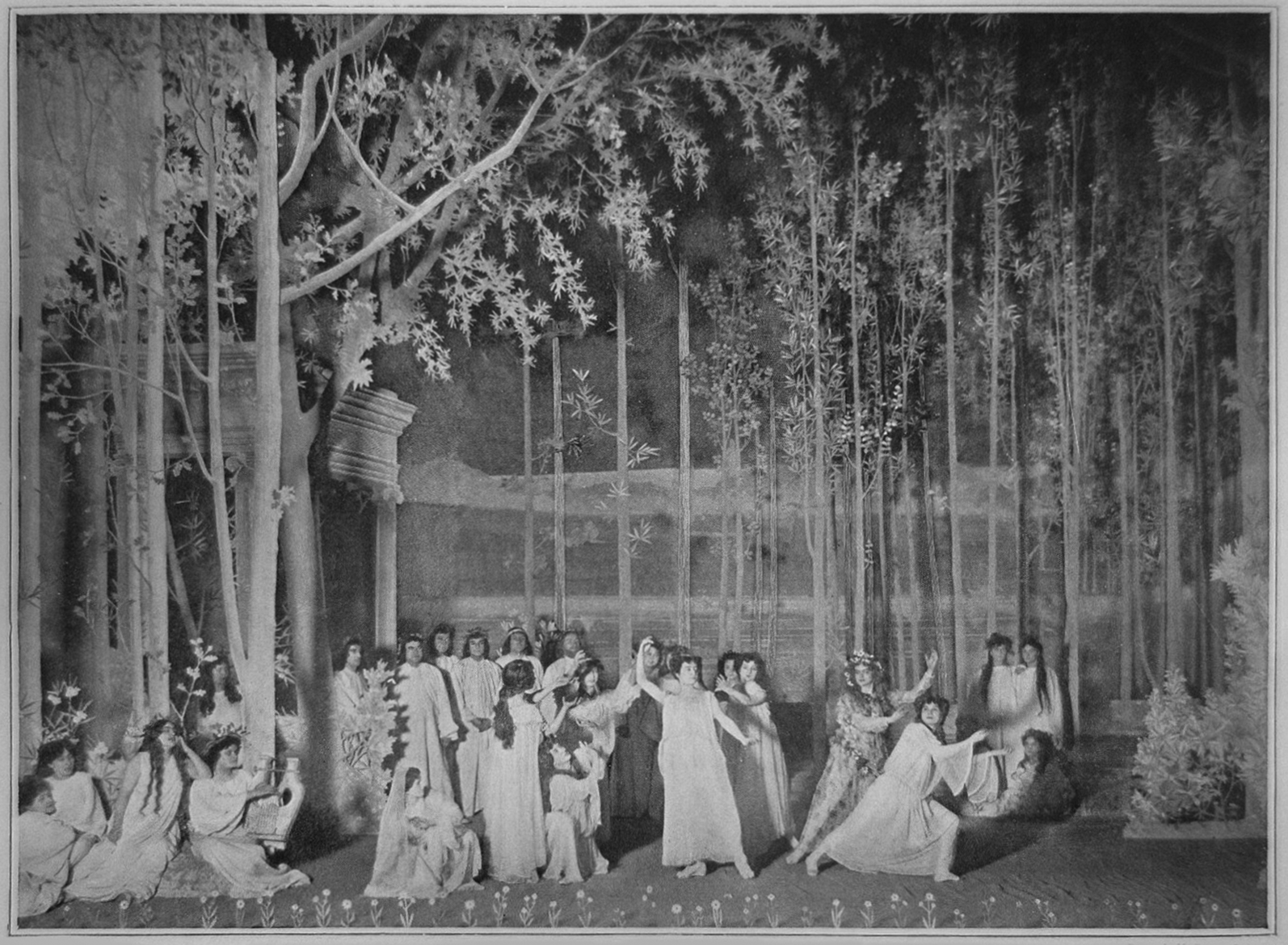

Mariquita's appointment to the position of ballet mistress for the Opéra-Comique marked an important turning point in her engagement with ancient sources: it was for the state theater that she would create her most significant Greek dances, and many of these would become crowd favorites as well as critical successes. The first were her divertissements for the Opéra-Comique's acclaimed revivals of C. W. Gluck's operas: Orphée in 1899, Iphigénie en Tauride in 1900, Alceste in 1904, and Iphigénie en Aulide in 1907. Where Gluck's Greek-themed operas had originally called for eighteenth-century dances, Mariquita choreographed tableaux that referenced images on ancient Greek pottery and bas-reliefs. Performed dozens of times by the Opéra-Comique and often reprised, the Gluck divertissements garnered unprecedented praise and captured the popular imagination.Footnote 11 Following these successes, Mariquita was invited to collaborate on several new Opéra-Comique works inspired by ancient stories and imagery. In 1906 she choreographed Greek dances for Camille Erlanger's opera Aphrodite and for Francis Thomé's ballet Endymion et Phoébé, and in 1912 she created ancient, although not specifically Greek, dances for Jean Nouguès's opéra-ballet La Danseuse de Pompei. Much in demand, Mariquita was also invited to stage a highly publicized “lyrical pantomime” Tanagra at the Théâtre des Mathurins in 1904, and she arranged solo Greek dances for her protégé, Régina Badet, to perform in private salons.Footnote 12

Mariquita's Greek ballets may have arisen out of an artistic drive to free the body from the strictures of ballet and bring “truth” back to dance; however, her interest in Greek dance and the timing of her experiments speak to a shrewd understanding of her role within the Paris Opéra-Comique and of her awareness of France's cultural insecurities in the years following the country's humiliating defeat in the Franco-Prussian War (Gutsche-Miller Reference Gutsche-Miller2021). When Mariquita became the ballet mistress of the Opéra-Comique in 1898, she joined a theater in a state of flux. Known as the second national theater after the Paris Opéra, the Opéra-Comique had recently engaged a new director, Albert Carré, and it had a new mandate. It had also recently become the subject of public discussions. Carré had been selected by the Ministry of Fine Arts after lengthy and much publicized deliberations about the direction the theater should take, at the same time that the Opéra-Comique had become the focus of debates in the press about what role it should play in French culture (Blay Reference Blay2001). As a national theater with a state subsidy, the Opéra-Comique, like the Opéra, was responsible for promoting a nationalist narrative of French music and dance, which included establishing which French works of the past were “great” and how the theater should project future French greatness (Gibbons Reference Gibbons2013, 8–15). Carré had a complex task. He was to cast his opera house as an identifiably “French” high-art theater that was at once a museum of established works and a space for modern innovation, all while attracting a broad audience.Footnote 13

The idea of “Frenchness” resurfaced frequently in all publications about the Opéra-Comique and mirrored broader cultural debates of the period (Gutsche-Miller Reference Gutsche-Miller2021; Blay Reference Blay2001). Haunted by fears of decay or decline, and keen to establish cultural preeminence, political and cultural leaders were obsessed with figuring out what “French” culture should look and sound like. One trend to emerge from these debates was the appropriation of ancient Greek culture as French. Although Greek art and artifacts had served as inspiration for French artists for the last two centuries, the end of the nineteenth century saw a noticeable increase in allusions to ancient Greek culture, with scholars, artists, and musicians making concerted and often politically motivated efforts to create connections or “lineages” between the revered ancient Greeks and the French (Olin Reference Olin1991, 76).Footnote 14 The tangible results of these attempts to invoke the cultural cachet of classical antiquity was a flourishing of Greek culture in France, from translations and reconstructions of ancient Greek theater to new French plays inspired by Greek models performed in plein-air amphitheaters, and from scholarly research into Greek philosophy, art, and music to new music, dance, and art based on Greek subjects.Footnote 15

Greek dance turned out to provide the ideal vehicle for realizing Carré's goals. Mariquita's ballets needed to appear serious, to project an aura of cultural authority, and to seem distinct from mass-market entertainment—which ironically included Mariquita's own repertoire for music halls and boulevard theaters—and they needed to be entertaining. Greek dances did all of this. Inspired by museum art and artifacts, they had unassailable academic credentials and projected gravitas; they provided an alternative to the stilted conventions and empty acrobatics of academic ballet as seen at the Opéra without losing ballet's high-art connotations; and they both harkened back to a glorious past and heralded an auspicious future. Even when integrated into the conventional narrative structure of a pantomime ballet, Greek dances were obviously modern.Footnote 16 In keeping with Carré's and French musicians’ aspirations of making the national theater worthy of its name, Mariquita's Greek ballets could also be cast as French, thus serving as the key to solving the Opéra-Comique's mission of projecting “greatness” and “Frenchness” while seeming both classical and progressive.

Mariquita most likely started exploring the movement possibilities suggested by ancient imagery after seeing other choreographers and performers experiment with Greek dance. Her models would have been numerous and diverse. Semipublic performances of what were then understood to be academically oriented revivals of ancient dances had been taking place since the early 1880s, and possibly before.Footnote 17 In 1881, Laure Fonta, for instance, attracted critical attention for salon performances of Greek dances “recovered” by musicologist Louis Bourgault-Ducoudray, and in the 1890s, scholar Maurice Emmanuel made several attempts at “reconstitutions” with the help of ballet masters Joseph Hansen and Louis Mérante, and dancers drawn from the Opéra's corps de ballet.Footnote 18 Performances quickly proliferated when the dancers went on to choreograph their own solos and gain names for themselves as experts in the art of Greek dance.Footnote 19 Greek dances grew even more plentiful in the late 1890s after the publication of Emmanuel's 1896 treatise La danse grecque antique d'après les monuments figurés.Footnote 20 As Samuel Dorf has noted, although Emmanuel's scholarship was far from rigorous, neither critics nor the public questioned his quirky methods and assumptions, and the book served as inspiration for numerous artists, musicians, and choreographers (Dorf Reference Dorf2019, 83). Emma Sandrini was especially successful in popularizing Greek dance.Footnote 21 In the late 1890s and early 1900s, Sandrini performed both her own and Hansen's Greek dances in a broad range of venues, from private salons and benefit concerts to government events with ten thousand invited guests, and from opera houses and music halls to outdoor arenas.Footnote 22

Perhaps Mariquita found these choreographed forms of ancient culture, already translated into movement on the modern body, deeply inspiring. However, she may also have recognized the commercial possibilities of Greek dance. The late 1890s not only saw a sudden increase in scholarly reconstitutions of ancient dances but also of erotic-exotic choreographic representations of ancient Greece in popular venues—performances that may have owed less to Emmanuel's treatise than to the popularity of erotic fantasies set in ancient Greece such as those dreamed up by Pierre Louÿs in Les Chansons de Bilitis (1894) and Aphrodite (1896).Footnote 23 Music halls in particular became a hotspot for sensuous evocations of ancient Greece. In 1896, Madame Stichel created one of the most popular music-hall ballets of all time, a production of Phryné in which the ancient tale of the sculptor Praxitèle and his muse and model Phryné provided a time-honored high-art cover for exhibitions of the female body.Footnote 24 The production included visions of scantily clad courtesans, beautiful female slaves, and young Greek boys in travesty, dances for Greek girls who loosen their belts and let their tunics fall, “lascivious” dances, and a dramatization of Phryné's trial for impiety, complete with her dropping her robes so that the jury (and audience) could see her perfect beauty.Footnote 25 The ballet was restaged the following year at the Folies-Bergère with choreography by Mariquita.Footnote 26 In 1897, the Olympia staged an erotic-exotic production loosely based on Louÿs's Aphrodite, and in 1898, a music-hall ballet dancer who performed under the name Odette Valéry drew thousands to the Casino de Paris by performing what were described in newspaper theatrical listings as lascivious Greek dances.Footnote 27 Choreographed antiquity quickly became synonymous with eroticism for a broad public.Footnote 28

Imagining Mariquita's Greek Ballets

Exactly what Mariquita's intentions were remains elusive. Reluctant to speak to journalists and disinclined to talk about her art, she rarely commented about her artistic aspirations.Footnote 29 At no point did she promote her choreographic vision with a theory of movement, declare that she was creating a new technique, or couch her dances in philosophy the way Isadora Duncan did; nor did she actively promote herself as the savior of French ballet. Unlike Duncan, Mariquita did not have to sell herself aggressively to make a living as a soloist. She also had to tread carefully between her creative interests and the needs of the institutions that employed her. Her comments in the press nevertheless offer a few tantalizing clues. In the early 1900s, Mariquita seems to have aligned her work with academic reconstructions. In an interview after the première of Alceste in 1904, she stated that she had found inspiration for her dances by examining statuary at the Louvre and had studied documents in libraries with the aim of accurately reconstituting archaic scenes.Footnote 30 Several critics attest to having seen Mariquita at the Louvre, alone, quietly absorbed in her study of ancient artifacts, and her first Greek ballets may well have followed in the footsteps of earlier reconstitutions.

A few years later, possibly in response to statements made by the up-and-coming Isadora Duncan, Mariquita somewhat revised her position. In a 1908 interview for Comœdia, she declared that she was not interested in attempting any kind of scientific or academic reconstructions of “authentic” Greek dances but was instead inspired by the music or by the dramatic context: “I imagine, I evoke, I reconstitute … my ideas hook on a gesture seen on old pottery, on an ancient vase, in a succession of poses on bas-reliefs. I supply what is missing, I unite the gestures, and thus bring life to the movement.”Footnote 31 Mariquita went on to reiterate her earlier scholarly conception of Greek dance, recounting that when Carré asked her to create a new divertissement for a reprise of Orphée she rushed to visit museums to study antique vases, friezes, and statues, and in them found the poses, attitudes, and gestures upon which she based her dance.Footnote 32 However, she went on: “What do you want, I am only an interpreter.… I have not invented or created Greek art.… I try only to express all of its beauty through dance by taking inspiration from masterpieces left to us, frozen in the splendor of the stones or marbles or in the magnificence of the frescos”Footnote 33

We know very little about what Mariquita's Greek dances actually looked like. Only a few studio photographs have survived, and although critics sometimes described the dances in reviews, these descriptions were as brief as they were vague. Reviews of French ballets staged at any venue in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century did not, as a rule, include commentary on steps, poses, gestures, choreographic patterns, or any other technical aspects of the dances; most only summarized scenarios and praised all of the creative and performing artists involved. Critics who offered additional insights wrote about Mariquita's dances in general terms, characterizing them as original, imaginative, and inventive, or as an “illusion of the renaissance of Attic grace.”Footnote 34 Others captured one specific moment. In his review of Orphée (1899), Adolphe Jullien, for instance, wrote that the dance of the blessed spirits, which for several other critics evoked Botticelli's Primavera, depicted “with undulating grace a dance of a nymph or a blessed spirit in the middle of the Elysian Fields while her companions wandered about her, intertwined, or silently grouped around her.”Footnote 35

Only one ballet, the divertissement in Iphigénie en Aulide (1907), elicited comparatively detailed accounts. Since these give a window into how Mariquita's Greek dances were perceived, I have translated the three most forthcoming descriptions in full.

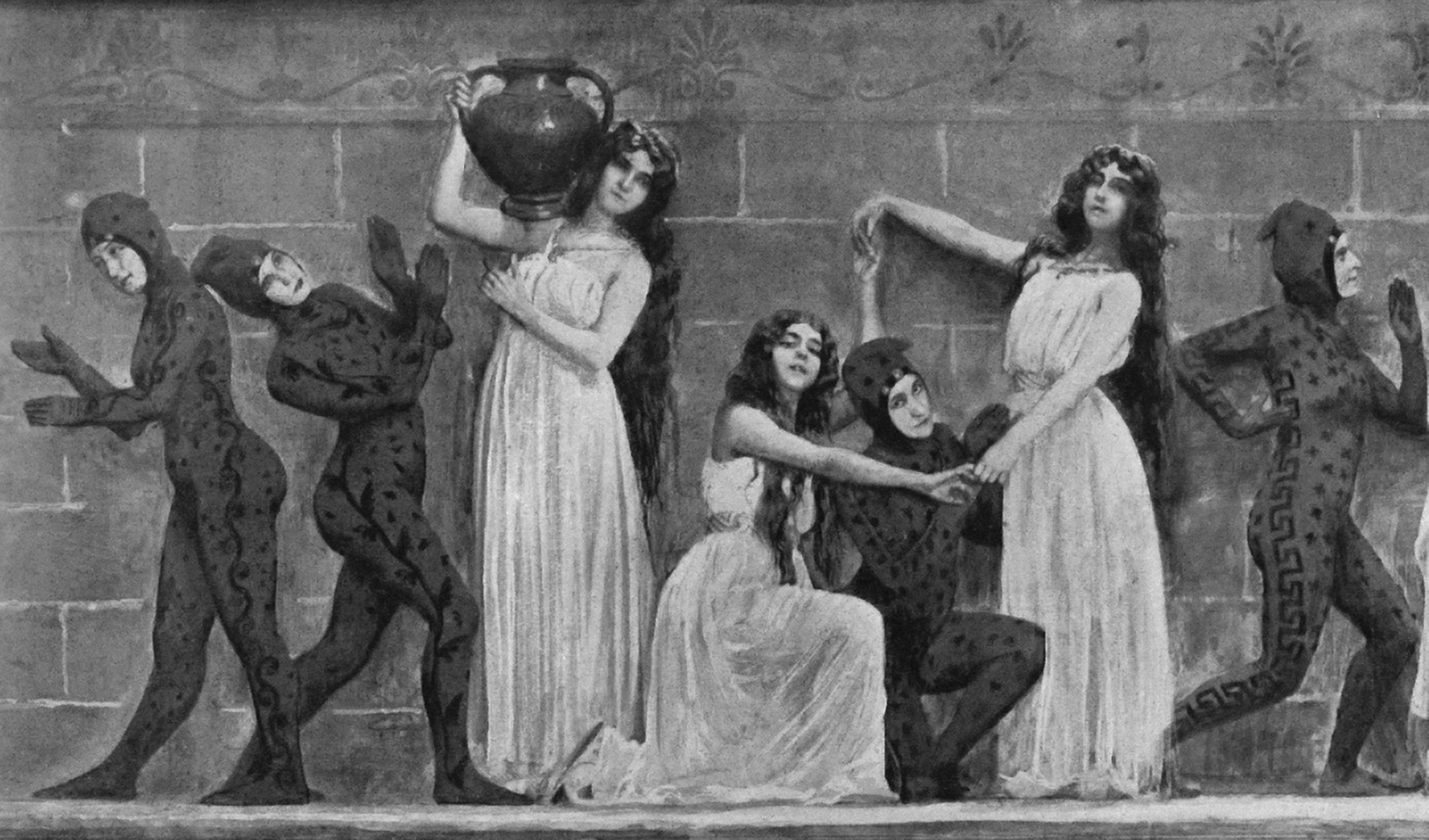

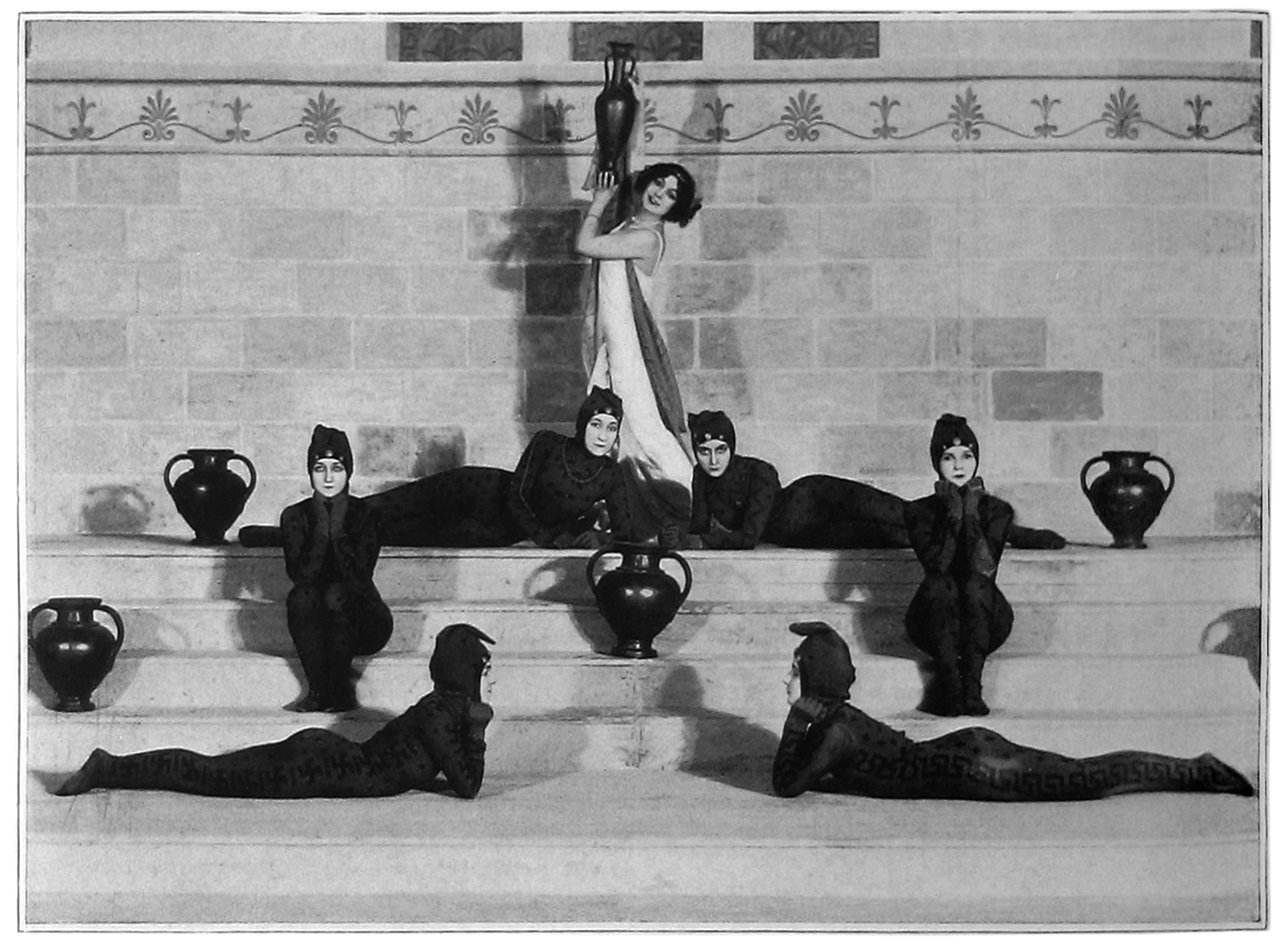

And before the fiancés, athletes battle and exchange violent blows. A bacchante, Mlle Régina Badet, dances voluptuously amid little characters copied from Etruscan vases who seem to be gods of wine or love. These enigmatic beings are as supple as felines. They wrap themselves around the ballerina; they stretch out on the stairs. Then, women with mysterious veils charm us with their blonde hair, with glimpses of their graceful bodies, and with their distant faces. All of a sudden, the dancers disperse, only to gather again at the back of the stage before a wall that they decorate with a living fresco.Footnote 36

The scene represents an atrium with low steps stretching across its width; at the back stands a low wall ornamented by Greek-style stonework. Groups [of dancers] move about in picturesque poses inspired by subjects reproduced from antique vases. When the dramatic action resumes, all of the groups return to the rear wall and form a living bas-relief of surprising effect; it is a vision of art of incomparable ingenuity.Footnote 37

A classical imagination, with a certain license, devised the forms and colors, attitudes and movements. She mixed among the dancers and captives half a dozen agile little creatures in tight head-to-toe brown and black leotards playing with ancient painted vases of the same color. They seemed like friendly little animals, strange, and a little lascivious, bronze lizards or tawny squirrels short cropped and without tails. They assume amusing airs and poses, elongated on the ground or crouched, elbows on knees, chin perched on the edge of their urn, laughing heartily. The “divertissement” completed, the dancers come to rest along the marble wall to form a living fresco.Footnote 38

Critics in the early 1900s had little context or vocabulary for writing about Mariquita's new form of gestural expression. The only language they knew to use was that of art history and archeology, and the result was an emphasis on, and repetition of, the term “reconstitution.” They frequently commented on how much Mariquita's ballets reminded them of ancient friezes, or they described the wonder they felt at seeing bas-reliefs come alive. Even when Mariquita's dances became increasingly driven by drama, fantasy, and exoticism, critics continued to interpret them as true “reconstitutions” of ancient Greek culture.Footnote 39 Writing about Alceste, for instance, Léon Kerst declared, “As for the Greek dances—admirable reconstitution—they give you the exact sensation of antique bas-reliefs all of a sudden coming to life”; Un Monsieur de l'Orchestre wrote, “One would genuinely believe we were seeing delightful antique frescos come to life and watching charming little figures detach themselves from amphorae”; and Charles Joly claimed that “it is thus that young Greeks must have danced.”Footnote 40 Even an explicitly exotic and erotic work such as Aphrodite elicited the comment by Intérim that “when watching the ballerinas dance, one would think we were seeing dancers escape from ancient bas-reliefs; the festive divertissement is a picturesque and curious reconstitution from a corner of antiquity.”Footnote 41 Serge Basset, who thought the work was rather racy, although staged with taste, tact, and art, ended his report with “the mise en scène was a monument of archeology; we regret some of the tableaux—astonishingly exact reconstitutions—could not be preserved in museums.”Footnote 42 Writing about the equally sensuous divertissement of Iphigénie en Aulide, Marsin likewise maintained that the reconstituted ancient dances gave the impression of seeing figurines come alive from potteries and frescos discovered in recent archeological excavations, while Louis Artus described the animated frescos as a marvelous lesson of living archeology.Footnote 43

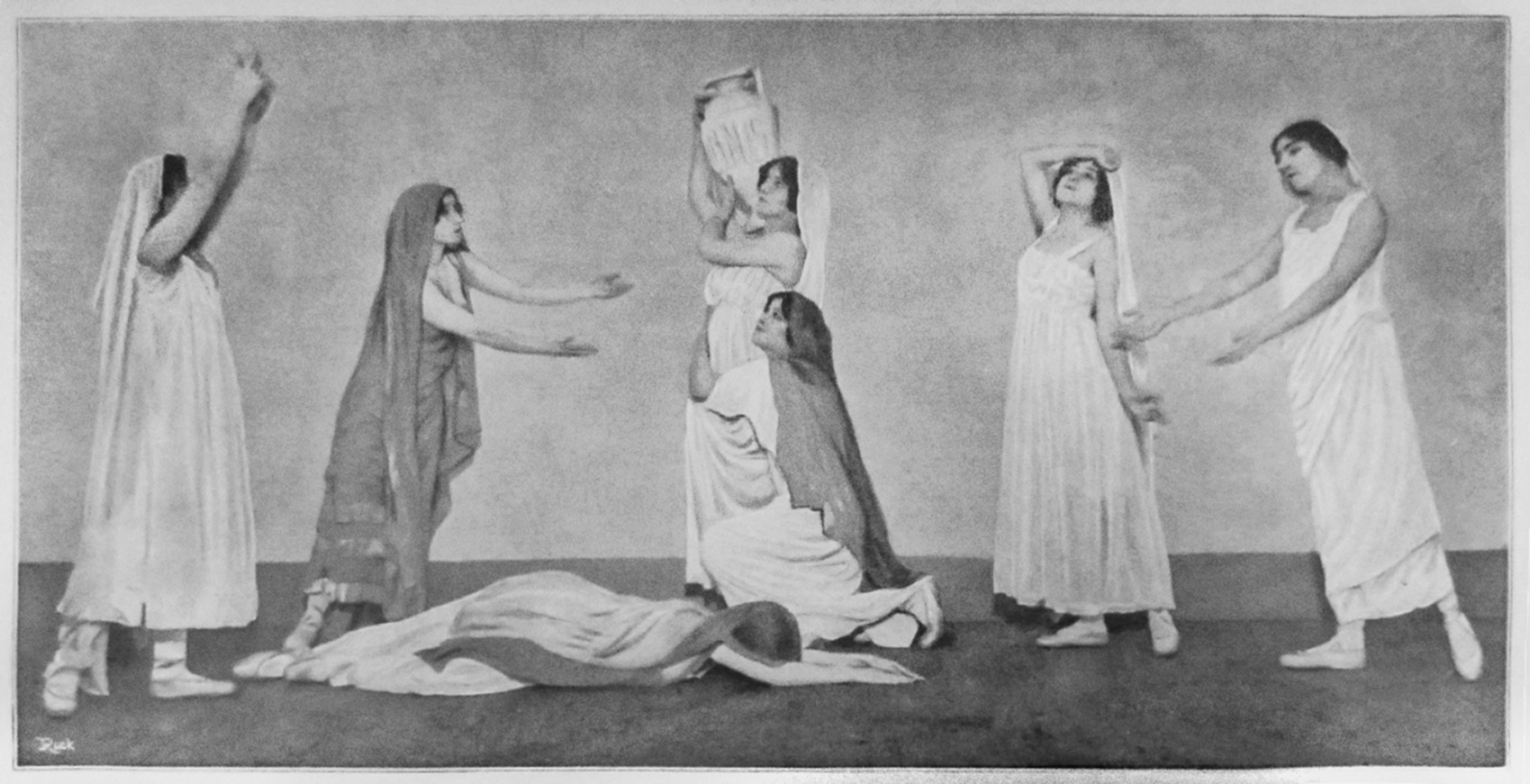

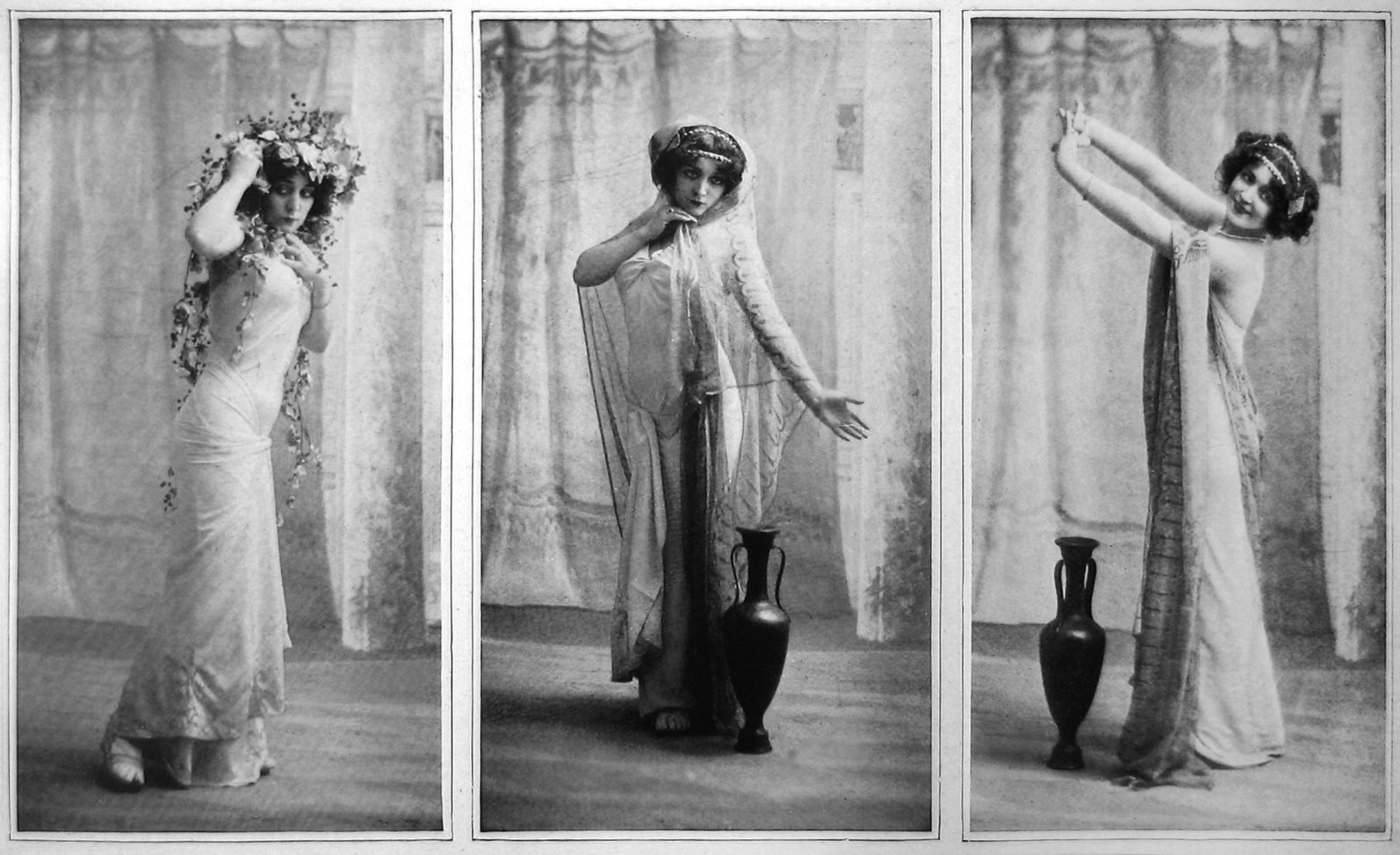

Studio photographs give a somewhat different perspective on the aesthetic of Mariquita's Greek dances. Several show scenes or poses that one might see on ancient Greek artifacts, but they depict a layering of ancient and modern aesthetics with poses embodied by trained twentieth-century French ballerinas. The dancers often stand in somewhat turned out positions, and in one photograph they are seen wearing pointe shoes, as they are in Emmanuel's academic treatise on Greek dance (Photo 2). Overall, evidence from photographs suggests dances with a modernized ballet vocabulary colored by the stance and arm positions of ancient Greeks as seen on friezes, kraters, and vases. Perhaps the most intriguing photograph is of the divertissement in Iphigénie en Aulide (1907) from L'Illustration in which dancers in full-body leotards are seen in profile (Photo 3).Footnote 44 The tableau of faun-like creatures holding friezelike poses and mingling with nymphs in flowing tunics seems to prefigure Nijinsky's L'Après-midi d'un faune (1912). Mariquita's ballet, which predated Nijinsky's famous example of early ballet modernism by five years, may explain the muted reaction of most Parisian critics to the Hellenic aspect of Nijinsky's production: it was something they had seen before.Footnote 45

Photo 2. “Reconstitution d'une fresque antique (Mme Mariquita),” Musica-Noël, no. 123 (December 1912).

Photo 3. Paul Boyer, “Iphigénie en Aulide,” L'Illustration, no. 3385 (January 11, 1908).

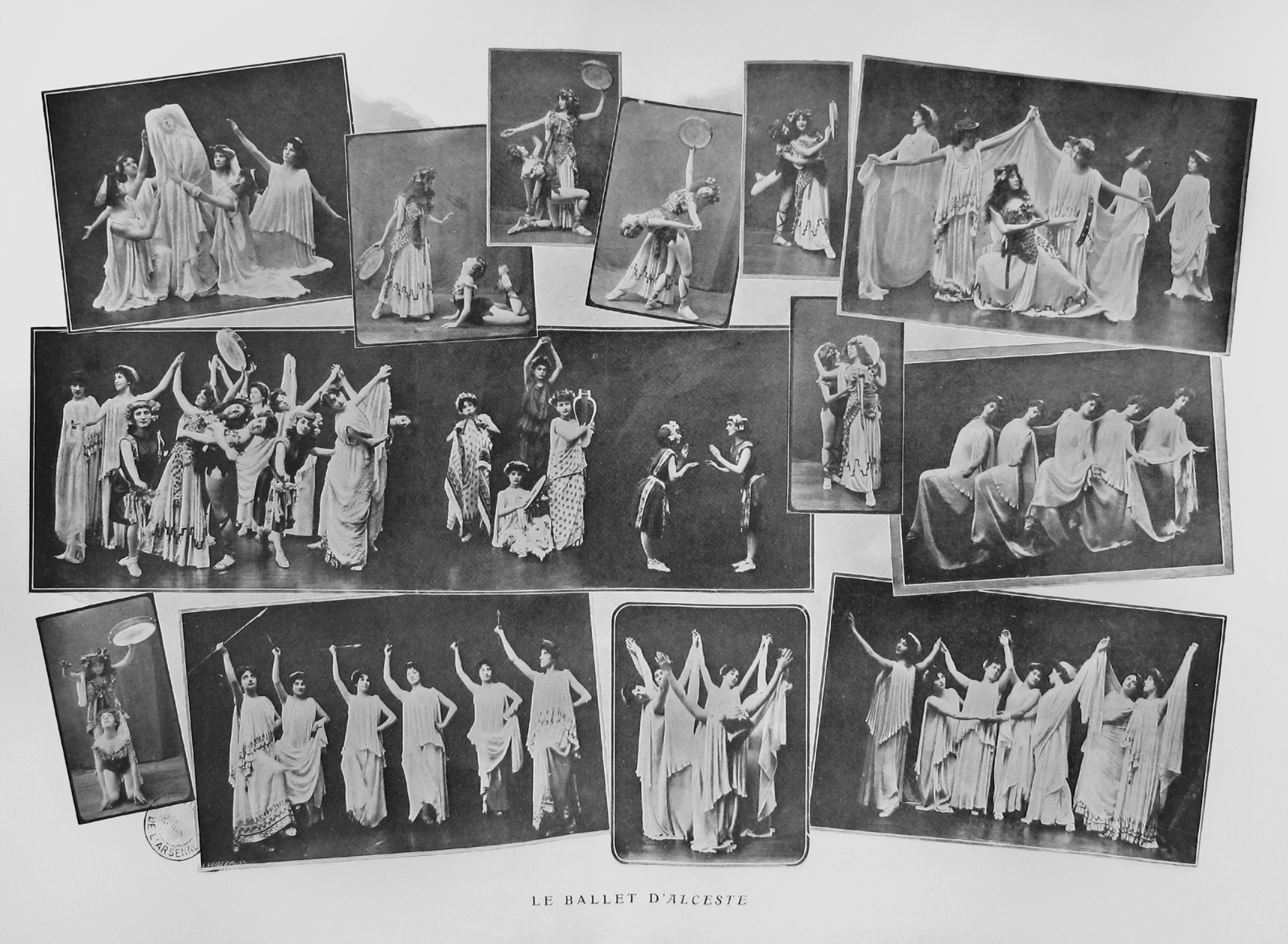

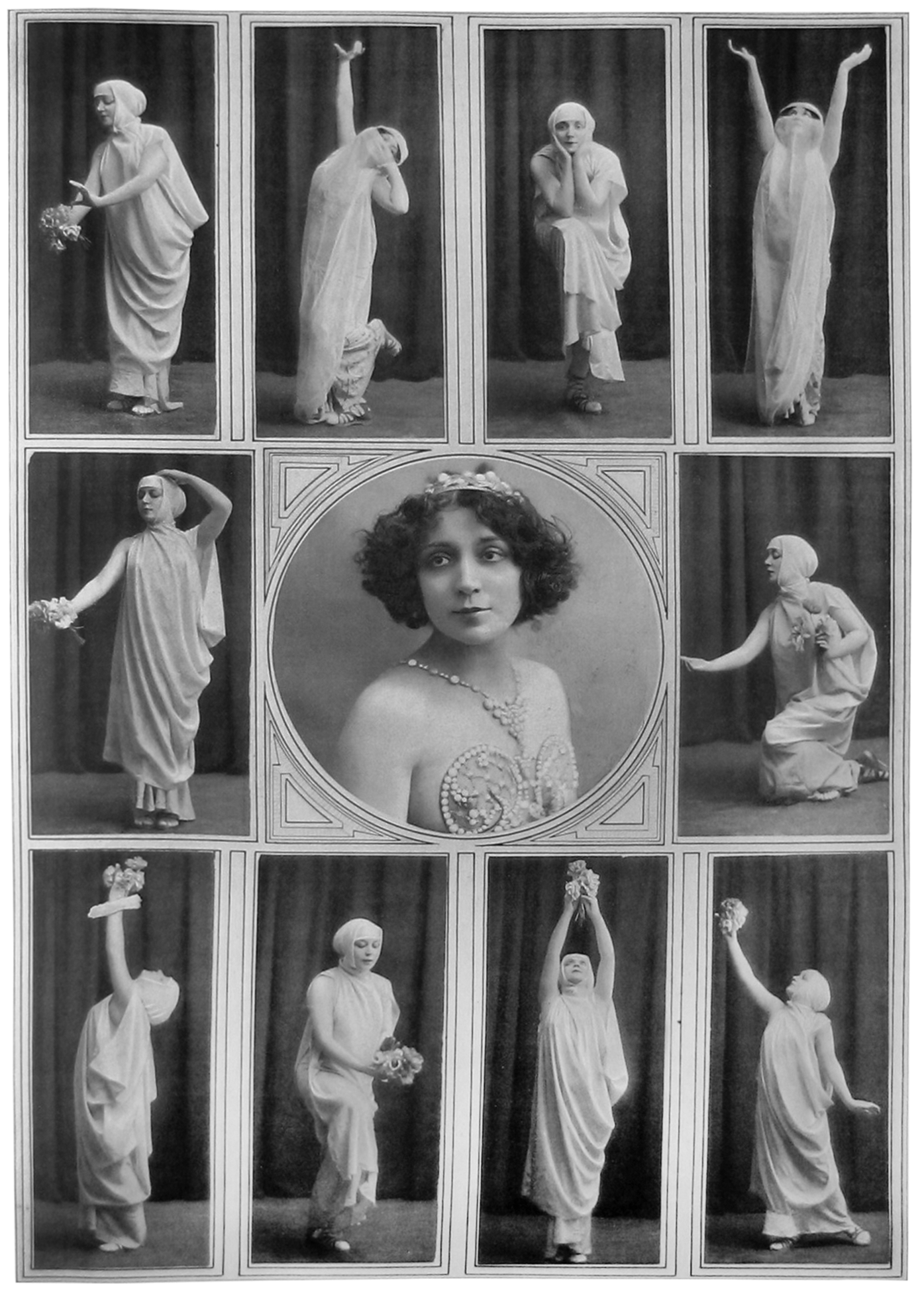

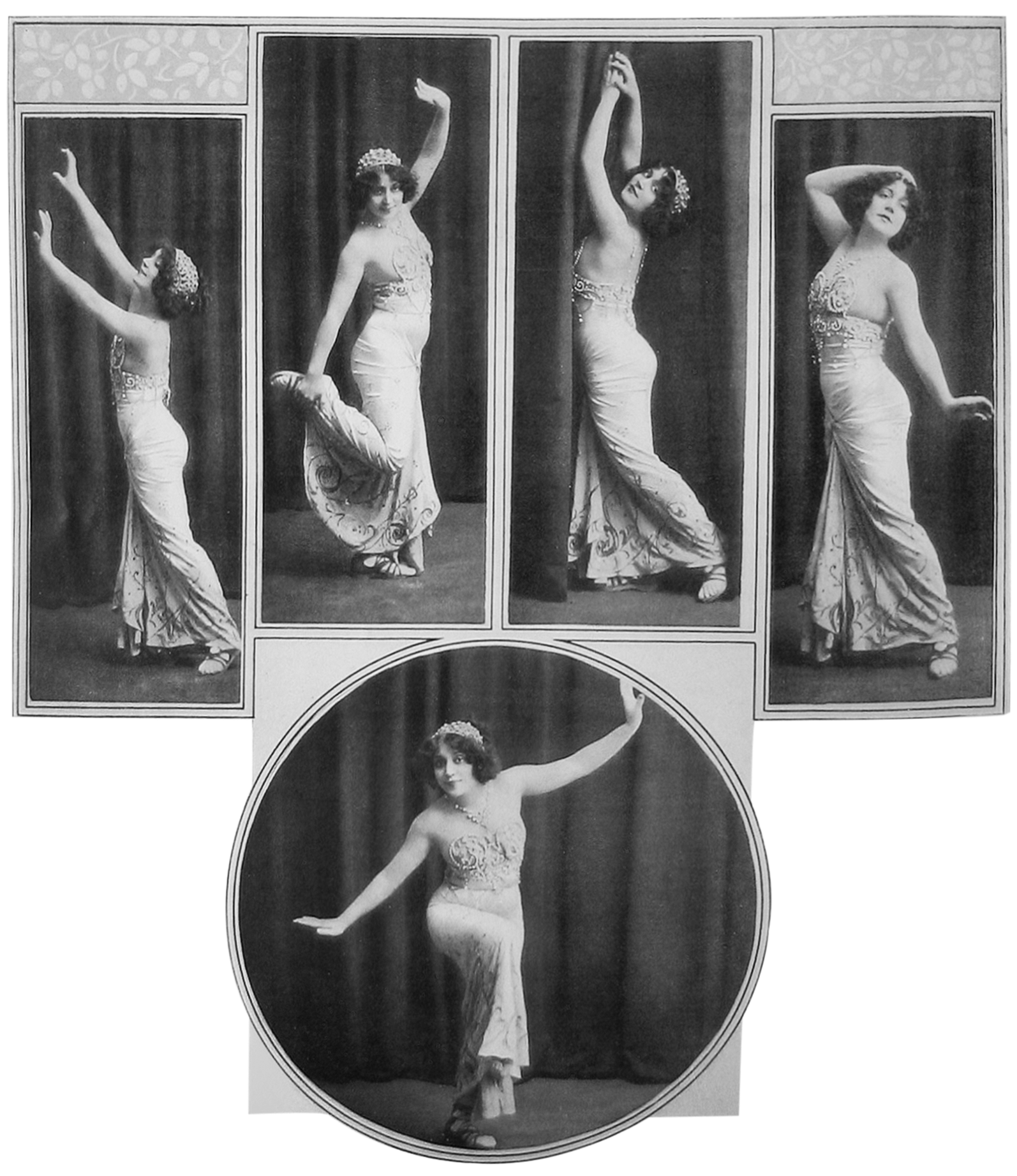

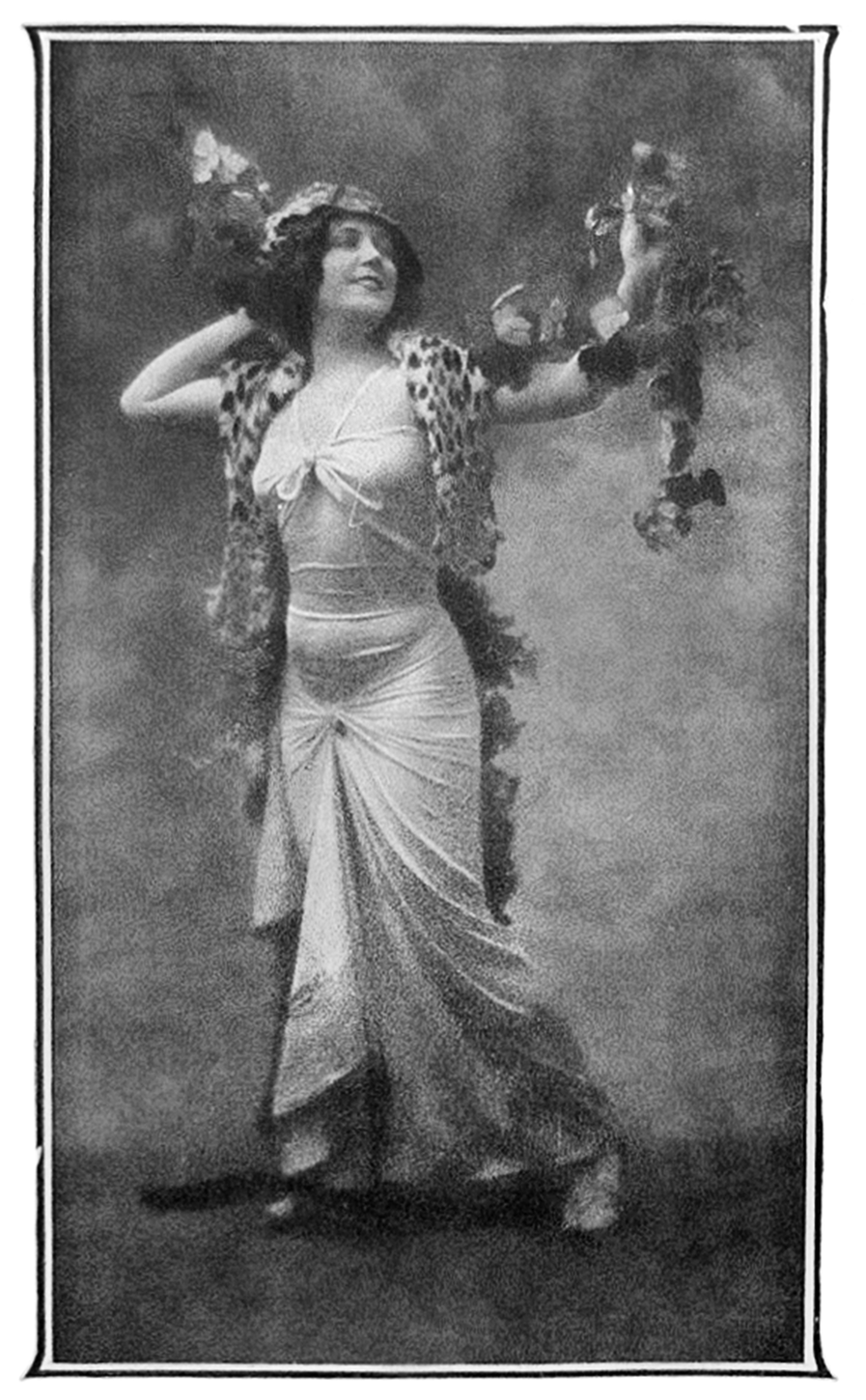

Photographs also provide evidence of an eclectic and evolving choreographic Hellenism. If staged photographs of Jeanne Chasles and the Blessed Spirits from Orphée published in Le Théâtre seem relatively austere and poetic (Photo 4), the collection of photographs taken of Alceste for La Revue Théâtrale depicts dances that appear to mix Grecian poses with pantomime, character dance, and tableaux vivants (Photo 5). Several photographs of Aphrodite, published in Le Théâtre, show Régina Badet in quasi-scholarly Grecian costumes performing gestures that echo images of Duncan with hands reaching to the heavens (Photo 6); however, as I discuss below, other photographs of the same work reveal a close affinity with popular exotic dance, echoing the costuming and flirtatious stance of performers such as Mata Hari (Photo 7).

Photo 4. Photograph by Mairet, “Ballet des Champs Élysées,” Le Théâtre, no. 28 (February 1900).

Photo 5. “Le ballet d’Alceste,” La Revue Théâtrale 3, no. 18 (September 1904).

Photo 6. “Régina Badet dans ses danses du 1er tableau—Opéra-Comique, Aphrodite,” Le Théâtre, no. 176 April (II) 1906.

Photo 7. “Régina Badet dans ses danses du 3e tableau—Opéra-Comique, Aphrodite,” Le Théâtre, no. 176 April (II) 1906.

Models and Influences

Mariquita's Hellenism probably was as eclectic as photographs suggest and very likely evolved over time. Although her Greek ballets were created within a relatively short period of time, an ongoing vogue for Greek dance provided Mariquita with a constant renewal of possible influences. Her earliest Greek ballets were most likely influenced by the combination of quasi-academic reconstructions of the 1880s and 1890s, popular “Greek” solo dances, and Rita Papurello's and Madame Stichel's music-hall ballets.Footnote 46 For instance, Iphigénie en Tauride, though perhaps inspired by museum artifacts, was described by one critic as a “savage ballet of Scythes” and by another as a “cancan of mujiks such as one saw at the Paris Exposition.”Footnote 47 Mariquita would also have been exposed to various experiments in Greek movement, including a performance at the Opéra-Comique in 1904 of the famous Magdeleine G., an amateur who, under hypnosis, improvised dances in Greek tunics accompanied by music from Gluck's Orphée.Footnote 48

One would assume Mariquita's greatest influence to have been Isadora Duncan, the independent young American who gained enduring fame by courting the most powerful cultural arbiters of the period, promoting her theories through the press, and charming audiences all over Europe.Footnote 49 Studio photographs of an enraptured Duncan performing in Greek costumes or surrounded by young girls were reproduced in the popular press beginning in 1903 in magazines such as Musica, La Vie Illustrée, and later Fémina, and her thoughts on the subject of dance were frequently published in the daily press. Mariquita must have been aware of Duncan's activities and philosophical pronouncements, whether or not she attended her salon recitals. She made a point of keeping abreast of theatrical trends and could not have ignored the many newspaper articles about the young performer, including the Gil Blas 1903 reprint of Duncan's manifesto, “The Dance of the Future.”Footnote 50

Mariquita claimed, however, that she had not seen Duncan's performances and that she was not interested in the American dancer, whom she characterized as unprofessional and poorly trained.Footnote 51 In 1903, Mariquita remarked that she thought dancing barefoot would be a passing fad, making the comparison to the wildly popular but fleeting cakewalk.Footnote 52 When interviewed in 1910, she again insisted that she had not seen Duncan dance and was not aware of her school (by then a very unlikely statement), and reiterated that she valued technique and hard work above all. She also repeated her earlier comment that one should not get too carried away by the latest fashions.Footnote 53 In her own article penned for Musica in 1912, Mariquita once again emphasized that dancers, above all, needed technique and a strict corporeal training to overcome any stiffness or awkwardness; once the body was rendered supple, it became a marvelous instrument ready to be molded in the purest of lines and most harmonious of rhythms.Footnote 54 Interestingly, her criticism often matched that of many Parisian journalists, who were at times openly derisive of Duncan's lack of technique.

Duncan's and Mariquita's performances probably only resembled each other in a generic way as a result of drawing on similar sources. A comparison of critics’ commentaries suggests that the two had contrasting approaches to and conceptions of Greek dance, which, along with disparities in training, led to appreciable differences in what their dances looked like. Most journalists understood Duncan's dances to be embodiments or evocations of music and art, and they described her dances as a series of beautiful poses or emotionally provocative attitudes that elicited poetic visions or recalled an ancient arcadia.Footnote 55 Many, however, criticized her choice of music or her use of silence, or they commented on her lack of technical training, which was apparent when moving between positions and, for some, marred the overall effect.Footnote 56 In contrast, Mariquita's Greek ballets, often choreographed for ensembles, usually had a dramatic motive or illustrative purpose, as was the convention for ballets and opera divertissements. Even her more abstract creations, such as the divertissement in Iphigénie en Aulide that elicited the accounts included above, had a rudimentary narrative and comprised elements that recalled tableaux vivants. Mariquita's dances were often described by critics in poetic terms but with far greater interest in their historical accuracy, connections with museum artifacts, or visual impact. Perhaps viewing her dances through the lens of a Gesamtkunstwerk aesthetic in the wake of French Wagnerism, critics also praised Mariquita's ability to create dances that matched the work's dramatic context. The more detailed accounts of Mariquita's ballets call to mind the orchestrated group formations of ballet pantomime scenes or ensemble dances, with a sense of balance and flow, grace and elegance, equilibrium and proportion.Footnote 57 Her Greek dances had a new quality of movement and gestural vocabulary, but they remained ballets created for ballet-trained bodies that formed visually pleasing tableaux from beginning to end.Footnote 58

Exotic Antiquity

Orientalist exotic dances were almost certainly the inspiration for Mariquita's most popular Greek ballets: divertissements choreographed for Erlanger's opera Aphrodite (1906) and Gluck's opera Iphigénie en Aulide (1907).Footnote 59 Although she did not reveal her sources, Mariquita might have drawn on performances of “belly dances”—a general term used by French journalists for a range of unrelated Middle Eastern and North African dances they perceived as erotic gyrations and contortions of bared midriffs—which she would have seen at the 1889 and 1900 Universal Expositions and in music halls.Footnote 60 Or, she might have been inspired by the success of Mata Hari, a courtesan of Dutch origins introduced to Parisians as a sacred dancer from a Hindu temple.Footnote 61 Mata Hari had first come to the attention of the French public in 1905 with seductive improvisations danced while wearing bejeweled breastplates and a midriff-bearing sarong. The performance that so enraptured Parisians took place at the Musée Guimet, a museum of Asian art, and featured a décor of Hindu carvings from the museum's collection along with a backdrop of creeping vines.Footnote 62 Mata Hari's captivating erotic performances, with their titillating orientalism framed by museum gravitas, were the perfect model for Mariquita's dances in Aphrodite.

There is a notable visual similarity between studio photographs of Mata Hari's performances and those of Régina Badet's dances from the third tableau of Aphrodite. Badet's costume in Aphrodite is a slightly more demure version of Mata Hari's, with jeweled breastplates, sarong, and ornamental headpiece. The photographs in Photo 7 of Badet in Aphrodite, published in Le Théâtre, show Badet smiling coyly at the camera, holding poses that come closer to pinups than Hellenic art. In one, Badet stands with chest thrust forward, her right arm framing her head in a gesture that recalls a widely disseminated photograph of Mata Hari from 1906 (Photo 8).Footnote 63 In another photograph published in Musica, Badet holds vines that similarly recall those framing Mata Hari at the Musée Guimet (Photo 9). One can only speculate on how closely Badet's choreography mimicked Mata Hari's stock movements: Gabriel Fauré was the only critic to remark that the dances of Aphrodite evoked the “Javanese” dances of Mata Hari.Footnote 64 Audiences, however, must have recognized these parallels, if only subconsciously, and would have placed the two in the same category of sensuous dance, reinforcing the ballet's erotic appeal and contributing to its box office success. Badet later capitalized on the sexual overtones of Aphrodite by posing in costume for postcards and cabinet cards.Footnote 65

Photo 8. Mata Hari in 1905. “Mata Hari,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, accessed June 5, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mata_Hari

Photo 9. “Mlle Régina Badet, Aphrodite,” Musica 5, no. 44 (May 1906).

To some extent, Mariquita was simply following the lead of her co-creators involved in the Opéra-Comique's production of Aphrodite. Erlanger's operatic recasting of Pierre Louÿs's story of lust and crime was unabashedly exotic and erotic, as was Carré's staging, which reproduced the novel's orientalist sapphic tropes and visual spectacle.Footnote 66 Described by Lesley Wright as contemporary Paris with a gloss of antiquity, the opera was very much of its time (Wright Reference Wright, Branger and Giroud2008).Footnote 67 Despite critics insisting that the work had an “authentic character” and that the ballets were “picturesque and curious reconstitutions of antiquity,”Footnote 68 as Samuel Dorf has written, the production mixed past and present, oriental and occidental “in an erotic fantasy on an imagined antiquity for a fashionably modern audience” (Dorf Reference Dorf, Lee and Segal2015, 73). Mariquita's ballets were, in turn, unabashedly erotic choreographies of Greek exotic fantasies. In one, Régina Badet, playing the role of the dancer Théano, accompanies two young lesbian handmaidens as they play their flutes and sing an erotic tune about Eros and Pan.Footnote 69 Elsewhere in the opera, Badet was described by critics as “dancing amorous steps, swooning, laughing and crying out in extasy [crie de volupté].”Footnote 70

Primed as they were on a rich history of erotic exoticism, patrons of the Opéra-Comique were enthralled by Mariquita's dances for Aphrodite. Hellenism provided Mariquita with a veil that allowed her to project a sense of artistry while fulfilling patrons’ desires to see scantily clad young women gyrating on the stage.Footnote 71 Audiences’ enthusiasm may account for the sensuousness of her next Greek ballet, a divertissement for the Opéra-Comique's last Gluck revival, Iphigénie en Aulide. In the 1907 staging of Iphigénie en Aulide, Mariquita seems to have moved from the relatively austere evocations of ancient statuary seen in Gluck's Alceste, performed only three years earlier, to the openly sensual exoticism of her recent dances for Aphrodite. Critics noticed the shift in aesthetic. Writing for Le Journal, Catulle Mendès described Régina Badet's dances in Iphigénie en Aulide as deliciously voluptuous and invoking Aspasia, a cultivated courtesan of antiquity, while Marsin, in l'Aurore, pronounced the ballet of the second act lovely but infinitely troubling.Footnote 72 Another critic used the dances as an excuse for describing Badet's curves.Footnote 73

Studio photographs likewise indicate that at least some of the dances in Iphigénie en Aulide were more highly sexualized than those of Mariquita's earlier Gluck ballets. In a series of photographs representing the act 2 ballet divertissement that illustrates a review of the opera in Le Théâtre, Badet is shown in a formfitting dress similar to the one she wore in Aphrodite: in one image she is seen peeking from beneath a chain of flowers, flirtatiously feigning innocence (Photo 10). In another, she has wrapped herself in a translucent veil, perhaps emulating the Dance of Seven Veils in Salomé, performed in Paris for the first time earlier that year with Natalia Trouhanova in the celebrated striptease. In a second series of photographs printed in the same article, Badet stands surrounded by dancers in skintight, full-body leotards decorated with the abstract patterns of amphoras (Photo 11). The dancers were perhaps meant to look like the painted figures on ancient terra-cotta vases such as those that decorate the set: as noted above, reviews describe them either as little Etruscan fauns, images from vases come to life, or bas-reliefs forming a living fresco.Footnote 74 However, the dancers’ bodies were also conspicuously on display. It is surely not a coincidence that the dances from Iphigénie en Aulide were the most photographed of Mariquita's ballets. Images of Régina Badet, surrounded by her lithe feline shadow figures, were splashed all over the popular theatrical press, which was always ready to capitalize on such fashionable and sanctioned erotic exoticism.Footnote 75

Photo 10. “Mlle Régina Badet dans Iphigénie en Aulide, acte II,” Le Théâtre, no. 223 (April 1, 1908).

Photo 11. “Iphigénie en Aulide, ballet du 2e acte,” Le Théâtre, no. 223 (April 1, 1908).

Conclusion

In her day, Mariquita was widely recognized for the role she played in the renewal of French ballet. However, by the end of the 1920s, her accomplishments had been overshadowed by more recent experiments in modern ballet, and her trailblazing career was all but forgotten. Many factors contributed to the erasure of her contributions to the history of French ballet.Footnote 76 Mariquita had made her name in popular theaters, and she continued to create ballets for commercial venues while she was the ballet mistress at the state-subsidized Opéra-Comique. Popular venues rarely reprised older repertoire, and few kept archival records of their productions. Added to this tangible lack of archival traces are longstanding disciplinary biases that favor studying state theaters over popular commercial venues. Even the Opéra-Comique remains underrepresented in cultural studies in comparison to the Opéra, and only a few scholars have returned to the archives to recover lost artists and repertoires.Footnote 77

Always reticent to attract attention to herself and content to create her art within established institutions, Mariquita did little to promote her ideas to the public and nothing to document her ballets for posterity. Duncan, in contrast, earned her fame through writing as much as through dance, and actively distanced her work from that of contemporary French choreographers. Although initially engaged in the same types of Greek dances seen on popular stages and appreciated as much for her seminudity as for her poetic visions, she pitted herself against ballet and its institutions and set herself apart from the erotic-exotic fantasies of the Parisian stage by constructing her own narrative that she disseminated through lectures and publications.Footnote 78 Diaghilev, too, marketed his company through a rhetoric of exclusion, appealing to high-society patrons in part by distancing his ballets from those staged in popular theaters, even though his first productions were not appreciably different in conception from popular ballets. He also marketed his choreographers as artists of independent mind and individual vision in contrast to ballet masters and mistresses, though their roles and responsibilities were essentially the same.Footnote 79 When she died in 1922, Mariquita was remembered by all as Paris's great ballet mistress, just as the term “ballet mistress” was becoming stigmatized.

Timing added another complication to Mariquita's legacy. She was most prolific in the 1880s and 1890s—a period of effervescent ballet extravaganzas, disparaged first by proponents of a more austere modernism and later by historians as one of decline and decadence—and she created her most profoundly original works at the end of her career in the early 1900s, shortly before the rise to stardom of the Ballets Russes. By the time she retired in 1920, both her most popular and her most innovative ballets had been sidelined by the more fashionable Russian dancers, by Duncan, and by recent, more modern French ballets staged by Jacques Rouché at the Théâtre des Arts and the Théâtre du Châtelet.Footnote 80 The divide has only widened since. Dance history as a discipline did not exist to document the many overlapping strands of choreographic exploration that characterized Parisian dance at the turn of the century, and the first accounts were penned many years later by nonspecialists who wrote about what they knew. Through repetition of secondary sources, labels have been carried forward, as have prejudices against commercial venues and small-scale genres such as opera divertissements.

Yet Mariquita was the leading choreographer of her generation, and the one who most profoundly reshaped audience expectations for ballet at the turn of the twentieth century. Her endlessly inventive music-hall ballets were central to a blossoming ballet craze in fin-de-siècle Paris, and their originality led to her being hired to rejuvenate dance at the Opéra-Comique. Her Opéra-Comique ballets, in turn, paralleled French cultural shifts in the 1890s and early 1900s in their exploration of new aesthetic paradigms, and they were part of the backdrop against which new forms of modern ballet would be understood in the 1910s and 1920s. They predated Duncan and the Ballets Russes, they predated Rouché's experimental dance works at the Théâtre des Arts and Châtelet, and they predated the Opéra's revival of its ballet tradition and transformation into a center for innovative French choreography under Rouché in the 1920s. By exploring new systems of movement, abandoning the traditional tutu, rejecting “empty” virtuosity and spectacle in favor of “natural” movement, and seeking dramatic coherence, Mariquita upended ballet traditions and set French ballet on the path toward modernism.