On a hopeful September day in 1912, Gim Pon, a twenty-five year old Chinese man from Canton, boarded the steamship Siberia in Hong Kong harbor to sail west across the Pacific.Footnote 1 The Siberia docked briefly in San Francisco, but Gim Pon's destination, and that of seven fellow Chinese travelers, was not California but the northern Mexican state of Sonora.Footnote 2 In the early twentieth century, thousands of men like Gim Pon immigrated to Mexico, boosting the Chinese population there from slightly over 1,000 in 1895 to more than 24,000 in the mid-1920s.Footnote 3 Sonora, which hugs Arizona at the United States/Mexico border, was a popular destination, and hosted the largest Chinese population of any Mexican state through the 1920s.Footnote 4 Once in Sonora, Gim Pon adapted to life in Mexico: he changed his name to Francisco Gim, learned Spanish, and became naturalized as a Mexican citizen on February 27, 1920.Footnote 5 Most importantly, he formed a family with Julia Delgado.

Julia Delgado was a young girl of nine, born near the sea in Mazatlán, Sinaloa, when her future partner left China in 1912.Footnote 6 In 1920, eight years after Gim's arrival in Mexico and the same year he became naturalized as a citizen, seventeen-year old Julia and he began their family life together in the mining town of Cananea, Sonora.Footnote 7 In Cananea, Julia gave birth to three children: Francisco in 1921, Guillermo in 1923, and another child who died in infancy.Footnote 8 By 1930, the Gim Delgado family lived and worked as the proprietors of a hotel in the small border town of Naco, forty miles northeast of Cananea.Footnote 9 Each member of the family could both read and write in Spanish, which was no small triumph.Footnote 10 In 1932, another son, Jesús, joined the family.Footnote 11 Even with significant indicators of integration for Gim and middle-class status for the family as a whole – Mexican nationality, Spanish literacy, and property ownership – the Gim Delgado family lacked formal legal recognition. Julia and Francisco were not civilly married, but lived together in a free union (unión libre).Footnote 12

Free union may have been the initial choice Julia and Francisco made in 1920, but it was not their last; they preferred marriage. Julia and Francisco repeatedly sought to marry, approaching the civil registrar and doggedly petitioning Sonora's governor, to no avail.Footnote 13 Law 31, a pointed anti-miscegenation law passed by the Sonoran congress in December 1923, stood in their way: “Marriage between Mexican women and individuals of the Chinese race are prohibited, even if the Chinese man has naturalized as Mexican.”Footnote 14 Violators were subject to steep fines: “Marital life or illicit union between Chinese men and Mexican women, when proven, will be punished by law with a fine of $100 to $500 applied by the municipal authorities . . . ” Footnote 15 In practice, municipal authorities incarcerated violators who could not or would not pay the fines.

Law 31 also impeded the marriage plans of Carlos Wong Sun and Juana Ramírez. On January 21, 1929, “accompanied by the witnesses the law requires,” Carlos approached the civil registrar in the village of Cucurpé.Footnote 16 On behalf of himself and Juana, Carlos presented a written request that the registrar “take account of our desire to unite ourselves in marriage” and issue the appropriate license.Footnote 17 The registrar refused, citing Law 31 as justification. Like Francisco Gim, Carlos Wong Sun had emigrated from Canton, China. He entered Mexico in 1904, through the Pacific port of Salina Cruz in the southern state of Oaxaca, then made his way north to Sonora where he established himself as a merchant and, in his own estimation, as a generous taxpayer.Footnote 18 He spoke Spanish, but remained a citizen of China.Footnote 19 Juana was born in Cucurpé in 1910.Footnote 20

Although prejudice against Chinese in Sonora was long-standing, Law 31 and a companion law creating Chinese ghettos marked a decided uptick in the use of law and legislation to discriminate against them. Julia and Francisco, Juana and Carlos, and many other Mexican-Chinese couples, responded in kind: they challenged Law 31 in federal court, seeking amparo – judicial relief – against its enforcement.Footnote 21 Through amparo petitions, Mexican women and Chinese men used federal court to resist the discrimination that the state of Sonora legally sanctioned. Despite the hostile political and social climate in Sonora, that strategy was surprisingly successful, if only for a short while. At the same time, Mexican-Chinese couples resisted Law 31 outside federal court as well. Mexican-Chinese couples, the women in particular, defied Law 31 when confronting the bureaucracy of government and the effects of Law 31 in their daily lives.

The amparo petitions brought by Mexican women and Chinese men in Sonora against Law 31, and public reaction to those petitions, tell a complex and fluid story about constitutional interpretation, judicial process, federalism, and national racial formation. At the same time, the story is intensely personal as petitioners sought to navigate race and citizenship, marriage and family, in a hostile environment.

With respect to constitutional interpretation and judicial process, Chinese amparo petitions in Sonora began in earnest as the judiciary in Mexico regrouped following the trauma and disruption of the Revolution. The 1917 Constitution itself was less than a decade old and judicial application of its principles was nascent as well. The early success of amparo petitions against Law 31 suggests a bright moment, albeit brief, in the history of constitutional interpretation and the rule of law in Mexico. Federal judges in Sonora, Judge Arsenio Espinosa in particular, grasped hold of the Constitution and federal law to protect a disfavored minority against an increasingly rabid majority and its political power.

In the end, however, Judge Espinosa's liberal constitutional interpretation did not prevail. First, federal amparo failed to protect Chinese from state-sponsored, violent expulsion from Sonora in 1931–1932, allegedly under secret instructions from Governor Rodolfo Calles.Footnote 22 Second, the Supreme Court heard two Law 31 appeals, one brought by Francisco Gim and the other by Carlos Wong Sun, but decided each differently. The Court granted Francisco Gim amparo in 1930 on technical grounds, but in 1932 denied Carlos Wong Sun the same relief on the merits. The Law 31 amparo petitions in federal district court, nonetheless, demonstrate both the possibilities and the challenges law provided to the disenfranchised in early twentieth-century Mexico. The Law 31 petitions provide context for resistance to Law 31 outside of court as well.

With respect to federalism, Sonora acted as a fulcrum between the competing values of national integration and regional power in Mexico's postrevolutionary development. Most dramatically, the Plan of Agua Prieta – signed in northern Sonora in 1920, three years after the new Constitution was in place – withdrew support for Venustiano Carranza's federal government and rejected elections in numerous states, actions ostensibly justified by a dispute between the federal government and Sonora over water rights.Footnote 23 Through the Plan, and its enforcement in a last violent revolutionary spasm, Adolfo de la Huerta, governor of Sonora and leader of the Liberal Constitutional Army, became interim president of the country.Footnote 24 The next two presidents, Alvaro Obregón and Plutarco Elías Calles, were likewise political and military leaders from Sonora.Footnote 25 These three presidents, and the enormous influence they exerted, became known as the “Sonoran dynasty” or “Sonoran hegemony” in Mexican politics.Footnote 26

Although in less dramatic fashion than the Plan de Agua Prieta, the state of Sonora continued to assert itself against federal law and the federal judiciary through its treatment of Chinese, even during the Sonoran dynasty.Footnote 27 Sonora, as a state, legislated against Chinese in direct contravention of Mexico's 1899 Treaty of Friendship, Commerce, and Navigation (FCN Treaty) with China, at least until Mexico cancelled the treaty in 1927.Footnote 28 At the same time, through discriminatory legislation including Law 31's anti-miscegenation principles, Sonora denied the power of the Constitution and of federal legislation to transform foreigners into Mexicans through naturalization. In contrast to Sonora's defiance of federal law, Mexican women and Chinese men who brought amparo petitions in federal court, relied explicitly on provisions of the 1917 Constitution. They thus asserted the legitimacy of federal law and its power to protect them from the discrimination that the Sonoran state legislature sought to impose.

As set forth in more detail below, Chinese men and their Mexican partners brought the bulk of amparo cases against discrimination in Sonora between 1924—shortly after passage of Law 31—and the end of 1932, when Chinese were violently expelled from the state. To highlight the intensity of Chinese litigation between 1924 and 1932, this study extends the years under consideration to 1921 and 1935.

Marriage and Mestizaje

Living together in a free union hardly made Mexican Chinese couples like Julia Delgado and Francisco Gim noteworthy. In 1870, Mexico instituted civil code reforms that gave legal recognition only to civil marriages; neither religious marriages nor free unions had legal effect. Despite these limitations, Carmen Ramos Escandón and others have demonstrated that formal legal marriages were not the norm in Mexico during the latter half of the nineteenth century.Footnote 29 This limited diffusion of civil marriage remained true in the early twentieth century as well. Data from the 1930 population census show that twenty-three percent of the adult population with a partner lived in free union.Footnote 30 Another twenty-eight percent of couples solemnized their unions religiously but not legally.Footnote 31 Therefore, in 1930, over half of the adult population living with a partner did so without the benefit of civil marriage, although a legal marriage could provide significant advantages, including registration of children as legitimate rather than illegitimate.Footnote 32 Whatever the advantages associated with civil marriage, less than half of the adult population living with a partner formalized their relationships legally.

Many couples in Mexico lived together without social opprobrium. Nonetheless, the intimate relationships between Julia and Francisco and between Juana and Carlos, as Mexican women and Chinese men, cast aspersion on them. Mexican-Chinese couples suffered even in a country defined by a mestizo ideal where interracial relationships were commonplace.Footnote 33 At the political level, mestizaje operated as “the unofficial ideology of the Mexican state in the 1920s and early 1930s.”Footnote 34 At the same time, the mestizo ideal focused heavily on mixing among indigenous peoples, Spanish, and, nominally, blacks, to the virtual exclusion of Chinese and other Asian groups.Footnote 35 By 1930, mestizaje in Mexico—at least Spanish and indigenous mixing— was ostensibly so complete that the National Statistics Department eliminated any explicit question regarding race from the population census.Footnote 36 The rhetoric of mestizaje in Mexico idealized Spanish/indigenous miscegenation, acknowledged blacks, and ignored Chinese.

Despite exclusion of Chinese from the professed ideal and official rhetoric of mestizaje, the actual reality of race-mixing in Mexico differed. First, Chinese and other Asians were present in Mexico and intermarried with the local population from the mid-1600s forward, albeit in relatively small numbers.Footnote 37 Second, by the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Chinese population in Mexico was overwhelmingly male. The 1930 population census put the Chinese population in Sonora at eighty-eight percent male.Footnote 38 Once in Mexico, Chinese men had extremely limited opportunities to form intimate relationships with Chinese women, given their scarcity. Intimate heterosexual relationships, of necessity, occurred with local Mexican women.

In Sonora and elsewhere, that interracial reality for couples like Julia and Francisco or Juana and Carlos posed significant challenges. Mexican-Chinese relationships received intense, negative scrutiny, both privately and publicly. Manuel Lee, born to a Mexican mother and Chinese father in 1921, recalled that his mother's desire to marry his father “generated a big fight between my mother and my grandfather . . . . Who would want a Chinese son-in-law?”Footnote 39 In 1922, El Intruso, a newspaper in Cananea where Julia and Francisco lived, mocked a Mexican woman for living with “a damned vulgar Chinese” supposedly because his numerous chickens made him well-off; the paper implied that prostitution would be a better solution to her economic needs.Footnote 40 Walterio Pesqueira, municipal president of Nogales, urged that segregated Chinese ghettos be created and then “strictly guarded” to keep Mexican women out.Footnote 41 Popular culture —songs, poetry, cartoons and comedies—likewise ridiculed relationships between Mexican women and Chinese men.Footnote 42

In his virulent anti-Chinese book El ejemplo de Sonora, José Angel Espinoza presented Sonora, its anti-Chinese legislation, and violent expulsion of Chinese from the state, as a model for the rest of Mexico.Footnote 43 In addition to his racially charged rhetoric, Espinoza visually demonized relationships between Chinese men and Mexican women in numerous cartoons.

Figure 1 “La noche de bodas” (Wedding Night), José Ángel Espinosa, El ejemplo de Sonora (México, D.F.; n.p. 1932), 36.

First, a vibrant, robust woman in high heels and fashionable underclothing prepares for her wedding night (la noche de bodas . . . . ) with a Chinese man.Footnote 44 In the second image, represented as five years later, (y cinco años después), her Chinese husband remains well-dressed, but the woman is gaunt, dressed in rags and sandals, three unhealthy children clinging to her skeletal arms and at her feet. The message is clear. Life with a Chinese husband would destroy a Mexican woman.

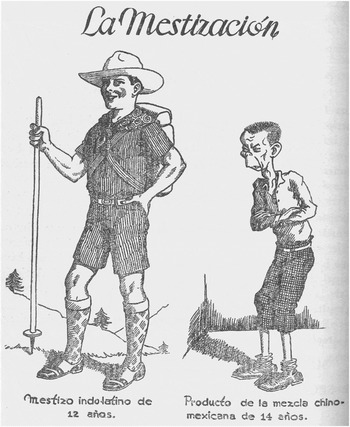

Figure 2 “La mestización” (Race Mixing), José Ángel Espinosa, El ejemplo de Sonora (México, D.F.; n.p. 1932), 56.

A second cartoon vilifies Mexican-Chinese relationships indirectly through the children they might produce.Footnote 45 The twelve-year old mestizo of Indian Latino parentage is a strapping young man with bright cheeks and a smile, confidently facing the world with his backpack and walking stick in hand. In contrast, the fourteen-year old child of Chinese Mexican parentage is scrawny, hunched over, and badly formed, eyes cast down. A Mexican woman should fear for the health and welfare of her children, if their father were Chinese.

Beyond vitriolic portrayals of Mexican Chinese relationships and children, Espinoza cautioned Mexican men against causing Mexican women's racial infidelity with Chinese and thus threatening the nation as a whole.Footnote 46

Figure 3 “Quienes no oyeron mis palabras” (Those who don't hear my words), José Ángel Espinosa, El ejemplo de Sonora (México, D.F.; n.p. 1932), 33.

A Mexican worker wearing a typical Sonoran outfit of sombrero, white shirt, and bandana, grips a Mexican flag while a more formally dressed gentleman in a three-piece suit and tie leans on a podium and gestures towards the flag before a crowd of laborers and campesinos. The handbill on the podium reads: “Mexican: Of every dollar you spend with the Chinese, fifty cents goes to Shanghai and the other fifty chain and prostitute women of your race.” In other words, when supporting Chinese businesses, Mexican men prostituted Mexican women. The underlying caption quotes José María Arana, a prominent leader of anti-Chinese groups in Sonora until his death in 1921: “Those who don't hear my words will wail tomorrow in agony for the Country that we were incapable of defending.” The cartoon thus explicitly linked Mexico's well-being as a nation with Mexican women's racial and sexual fidelity; to remain whole and pure, Mexico had to defend itself and its women from the perceived onslaught of Chinese commerce and sexual immorality.

As Gerardo Réñique's careful analysis has demonstrated, anti-Chinese campaigns in Sonora played a central role in mediating and producing Mexican national identity in the postrevolutionary era: “the national/racial appeal of anti-Chinese rhetoric provided a language of consensus within the highly conflictive projects of state and nation building, the contentious relationship between the central state and the regions and, more important, between frustrated popular demands and the postrevolutionary capitalist strategy of development.”Footnote 47 Mexican-Chinese couples and their children stood at the epicenter of Sonoran racism and therefore, the project of national racial formation in Mexico. Relationships between Mexican women and Chinese men both occasioned anti-Chinese rhetoric and, through their mere existence and the children they produced, defied it. By deploying amparo petitions in federal court and by asserting constitutional rights, Mexican-Chinese couples further complicated the “language of consensus” that anti-Chinese rhetoric provided. They asserted a place for themselves in an evolving Mexican racial identity that excluded Chinese, while at the same time creating a forum for federal judicial participation in that national project.

Law 31

When the Sonoran state congress passed Law 31 in December 1923, it legally reified the societal discrimination Mexican-Chinese couples faced. As state law, it posed for Julia and Francisco as well as for Juana and Carlos an impediment to marriage that Mexican-Chinese couples in the rest of Mexico did not encounter, despite intense criticism of their relationships.

Alejandro C. Villaseñor—a businessman, Chamber of Commerce leader, and municipal president in Nogales—sponsored the anti-miscegenation statute in the Sonoran congress.Footnote 48 Villaseñor boasted a considerable reputation for “longstanding anti-Chinese convictions,” which he backed up with action.Footnote 49 Like the other prominent anti-Chinese Sonorans already mentioned—José Angel Espinoza, Walterio Pesqueira, and José María Arana—Villaseñor argued that segregation of Chinese, both spatially and sexually, would promote a stronger, healthier Mexico.Footnote 50 With his business interests, civic leadership, and acute awareness of Mexican-Chinese relationships, Villaseñor epitomized the interplay among economic concerns, gender expectations, and plain racism that characterized the anti-Chinese campaigns in Sonora.

In the United States, state anti-miscegenation laws like Sonora's Law 31 proliferated from the colonial period through the mid-twentieth century when the Supreme Court declared them unconstitutional in Loving v. Virginia.Footnote 51 Particularly in the western United States, numerous state anti-miscegenation laws targeted relationships between Chinese and whites. For example, in the 1860s, Nevada, Idaho, Arizona, and Oregon all prohibited the marriage of whites and Chinese or “Mongolians.”Footnote 52 In the 1880s, California and Utah revised their anti-miscegenation laws to add “Mongolians” to the category of legally prohibited marital partners for whites.Footnote 53 In contrast to the proliferation of anti-miscegenation laws in the United States, Sonora's anti-miscegenation law was unique in Mexico.

Amparo Petitions against Law 31

In January 1924, less than a month after Law 31's passage, Manuel Yee filed the first federal amparo petition against its enforcement.Footnote 54 Yee was Chinese born, but, like Francisco Gim, was naturalized as a Mexican citizen.Footnote 55 Yee alleged that the municipal president of Nogales—the same Walterio Pesqueira who advocated creating Chinese ghettos and guarding them to keep Mexican women out—had imprisoned him and fined him 100 peso for living with Rosario Hernández, although Yee maintained that he and Hernández had separated “at the beginning of December” before Law 31 was passed.Footnote 56

Other petitions making similar allegations followed in rapid succession. Luís G. Flores complained that he was jailed and fined, “for living with my wife, Mrs. Otila Morales” whom he said he had married in the United States.Footnote 57 Pablo Wong and Filomena Valdez challenged the fine they paid to get out of jail in Cananea, noting that they had “lived together as a couple for more than eight years, without public scandal and without the least offense to morality.”Footnote 58 Wong Guio sought amparo against civil registrars who refused his request for a license to marry Mercedes Salcido.Footnote 59 Julia Delgado and Francisco Gim did the same in 1926 when the civil registrar in Cananea refused them a marriage license.Footnote 60 In 1929, after the civil registrar in Cucurpé forbade his marriage with Juana Ramírez, Carlos Wong Sun followed suit.Footnote 61

Amparo petitions against enforcement of Law 31 were part of a larger legal strategy Chinese employed against discrimination in Sonora. This strategy of petitioning federal courts was the same means that Chinese in the United States used when they too encountered discriminatory legislation, both state and federal, in the late 1880s. As in Sonora, the legal strategy in the United States provided mixed results, sometimes succeeding, sometimes failing to provide relief.Footnote 62 By bringing amparo petitions against Law 31, Mexican Chinese couples forced the legal system to acknowledge the reality of their existence and allowed the federal judiciary to participate in formation of the postrevolutionary Mexican national identity. Thus, the amparo petitions challenged both Law 31 and the petitioners’ exclusion from the emerging national identity.

To provide context for the Law 31 challenges, Table 1 sets forth by year: i) the total number of amparo petitions brought in federal court in Sonora; ii) the number of amparo petitions brought by Chinese; and iii) the number of Law 31 petitions. Table 2 sets forth Law 31 amparo petitions by year, judge, and outcome.

Table 1. Chinese Amparo Petitions in Federal Court, Sonora, 1921–1935.

aLaw 31 amparo petitions include cases brought by Mexican women in conjunction with their Chinese partners as well as two cases brought by Mexican women without their partners.

Table 2. Law 31 Amparo Petitions by Judge and Outcome, Sonora, 1921–1935.

Plaintiffs brought twenty of the thirty-one petitions (65%) in 1924 alone, the first year Law 31 was in effect and the year that Chinese claims constituted more than half of the federal amparo docket in Sonora. Judge Arsenio Espinosa heard the Chinese amparo petitions filed in 1924, including the twenty challenges to Law 31. He granted all the Law 31 amparo petitions brought before him, except for one, which he dismissed when the petitioners were released from jail and failed to pursue their claim.Footnote 63 In 1925, two different judges, Cayetano Masse and Luís Bazdresch, heard three petitions against enforcement of Law 31 and granted all three.Footnote 64

In 1926, Judge Joaquín Ruíz broke the informal precedent set by Espinosa, Masse, and Bazdresch. He denied two of the three petitions he heard, including an action filed by Julia Delgado and Francisco Gim, and dismissed the third on procedural grounds when the petitioner failed to formally verify a complaint initially made by telegram.Footnote 65 Also in 1926, Judge Rito Chacón heard one petition, which he suspended when the petitioner apparently abandoned the claim.Footnote 66 The few challenges to Law 31 after 1926 all failed in the court of first instance. These failures included the two petitions brought in 1929, one by Francisco Gim and one by Carlos Wong Sun, both of whom appealed to the Mexican Supreme Court.

Amparo petitions brought by Chinese against other discriminatory actions and legislation in Sonora reflect a similar pattern over time. Challenges brought in 1924 and 1925 before Judges Espinosa, Masse, and Bazdresch largely succeeded, whether petitioners sought amparo against a 1923 companion to Law 31 that created Chinese ghettos or against police actions singling out Chinese for violating morals legislation.Footnote 67 Challenges brought after 1925 almost invariably failed, either on the merits or for technical reasons. Amparo petitions in 1931 focused on a new law that reinforced an earlier requirement that businesses employ eighty-percent Mexican nationals.Footnote 68 The 1931 law prohibited businesses from counting naturalized Mexicans toward the required eighty percent.Footnote 69 In 1932, a few desperate Chinese men challenged their expulsion from the state, requesting amparo from hiding or by proxy through their Mexican partners.Footnote 70 Their requests also failed.

The thirty-one amparo petitions challenging Law 31 are largely formulaic.Footnote 71 With minimal variation, the petitions allege violations of various articles of the 1917 Constitution, although the petitions usually simply name the article without stating the specific right at issue: Article 1, guaranteeing constitutional rights to all individuals; Article 14, prohibiting deprivations of “life, liberty, properties, possessions or rights,” without appropriate judicial process; Article 16, guaranteeing rights to person, family, home, papers, and possessions; Article 21, recognizing a right to judicial process; and Article 30(II)(b), providing for naturalization as a Mexican national. In addition to their constitutional arguments, many of the petitioners cited the 1899 Friendship, Commerce, and Navigation Treaty between Mexico and China for relief. The amparo petitions vary primarily, although not exclusively, in the factual details of when and where and how government officials sought to enforce Law 31 against the petitioners.

The Nature of Amparo

Amparo, as a judicial remedy for governmental violation of rights, has a complex, contested history in Mexican law.Footnote 72 In the pre- and postrevolutionary years, many legal scholars debated the rights amparo should protect – natural rights, constitutional rights, other positive rights – and the mechanism by which that protection should occur.Footnote 73 In its most basic procedural form, however, a judge's decision in an amparo petition applied only to the actual litigants in the case;Footnote 74 hence, the need for individual after individual, and couple after couple, to seek particularized judicial relief against legally sanctioned discrimination including the imprisonment and fines that Law 31 allowed government officials to impose on Mexican- Chinese couples. When a judge granted amparo to a petitioner, the effect was to disallow application of the law in the specific instance at issue, not to declare the law itself invalid.Footnote 75 The form of judicial review that Marbury v. Madison Footnote 76 spawned in the United States and that allowed a court to declare legislation unconstitutional, did not gain traction in the Mexican legal system, although the idea existed.Footnote 77 Ignacio Luís Vallarta, president of the Mexican Supreme Court from 1878 to 1882 and prominent legal scholar, argued strenuously for judicial review of the Marbury v. Madison type.Footnote 78 He also published detailed judicial opinions in a form akin to those found in the common-law tradition, a form that would have facilitated their use as precedent.Footnote 79 Vallarta's commitment to judicial review and form of judicial opinion writing, however, did not prevail. Rather, Mexican jurisprudence and legal discourse rejected judicial review and, particularly after the 1910 Revolution, retrenched firmly in the civil law tradition where a judge's role was quite circumscribed.Footnote 80 That retrenchment involved significant debate about the appropriate criteria for judicial decision making when Francisco Gim appealed his case to the Supreme Court in 1929.

In the civil law tradition, individual amparo decisions had no formal precedential value.Footnote 81 Article 107(1) of the 1917 Constitution, known as the Otero Formula, stated simply that a grant of amparo benefited the petitioner “without making any general declaration regarding the law or legislation that motivated the complaint,”Footnote 82 and echoed similar language in Articles 101 and 102 of the 1857 Constitution. Although the constitutional Otero Formula limited their formal precedential value, individual amparo decisions carried significant informal weight.Footnote 83 Where a single judge received in close succession numerous amparo petitions challenging application of the same law and based on largely similar facts, a relative uniformity of decision was likely.Footnote 84 Chinese amparo petitions in Sonora bear out that likelihood.

Judge Arsenio Espinosa's Decisions

As noted earlier, Manuel Yee brought the very first federal amparo petition against Law 31 when it was enforced against him in January 1924, less than a month after the law was passed. Arsenio Espinosa, the federal district judge for the state of Sonora, adjudicated Yee's plea, the first of the twenty Law 31 petitions he heard.Footnote 85 In what would become a template for his subsequent decisions, Judge Espinosa granted amparo against the fine and incarceration that Nogales Municipal President Walter Pesquiera imposed on Yee. Relying on the district attorney's (Agente del Ministerio Público) support for amparo in the case, Judge Espinosa held that Law 31 was obviously unconstitutional. It contradicted Article 1's guarantee of equal rights to all natural persons; Article 13's requirement for general laws; and Article 14's prohibition against deprivations of “life, liberty, properties, possessions, or rights,” without appropriate judicial process.

In Judge Espinosa's constitutional analysis, singling out Chinese for punishment, as Law 31 did, meant the law denied equal rights as it was not applied to the population generally. Judge Espinosa noted that free union or concubinage (mancebía o concubinato) was not a crime, as long as the relationship was discreet and did not incite public scandal. If free unions or concubinage were criminal, Judge Espinosa reasoned, then they would have to be criminal for all, not just for Chinese men and Mexican women. Likewise, in Judge Espinosa's analysis, Law 31's focus on Chinese men and Mexican women deprived Yee of “life, liberty, properties, possessions, or rights,” without appropriate judicial process.Footnote 86

Judge Espinosa ended his decision on federalism grounds. In his view, the application of Law 31 to Manuel Yee clearly violated federal constitutional rights and guarantees. Citing the supremacy provisions of Article 133 of the Constitution, Judge Espinosa concluded that Law 31, a state law, “could not serve as the basis nor as adequate legal cause” for a municipal president such as Pesquiera to fine and incarcerate Yee. Without adequate authority based in positive law—state or federal—President Pesquiera's actions were unconstitutional at the federal level and violated Article 16's requirement that only competent legal authority could properly restrict rights or interfere with an individual and his family.

Given the uniformity of the petitions and the quick succession in which Judge Espinosa heard them, it is not surprising that he used the first decision as a template. Espinosa appears to have drafted a single decision in Manuel Yee's case, and then, in an age before computers, had it retyped with the new petitioners’ names inserted. Despite the Otero Formula, the first individual amparo decision in a Law 31 case had more than informal precedential value: It actually became the decision in subsequent cases.

Julia Delgado and Francisco Gim: The 1926 Petition

In 1926, when Julia Delgado and Francisco Gim first sought amparo against enforcement of Law 31, the basic facts and constitutional arguments their attorney, Zeferino Quintero, made before Judge Joaquín Ruíz were no different than those made by other lawyers before Judge Espinosa.Footnote 87 In their case, however, and in contrast with Yee's, the district attorney representing the government's interest opposed the petition. Judge Ruíz denied amparo to Julia and Francisco, breaking with the informal precedent set by the cases decided previously.

Julia and Francisco both signed the amparo petition they presented to Judge Ruíz, claiming that the civil registrar in Cananea had denied them a marriage license in early January 1926. Upon the registrar's refusal, they sent a telegram to the governor of Sonora—presumably Alejo Bay, although they identify him only as the governor—requesting that he authorize their marriage despite Law 31. When the governor refused, Julia and Francisco turned to federal court, and with Quintero's legal guidance, alleged violations of Articles 1 and 14 of the 1917 Constitution, as successful petitioners had done in 1924 and 1925. The complaint asserted the supremacy of the Constitution and federal courts against a state's discriminatory actions.

In addition to arguing that Law 31 violated Article 1's guarantee of equal rights to all natural persons and Article 14's prohibition against deprivations of “life, liberty, properties, possessions, or rights” without appropriate judicial process, Quintero added an express natural rights claim, asserting Julia and Francisco's right to marry, a right that a person carried with him or her “from birth”; “No law could take away this fundamental right,” although Law 31 tried to do so.

The district attorney opposing their amparo claim countered with a threefold argument that students of United States constitutional law, and particularly the Fourteenth Amendment, will immediately recognize: enumerated versus unenumerated rights, natural rights versus government power, and federalism. First, Francisco and Julia had failed to precisely state the individual guarantees that the actions of the civil registrar and state executive had violated in denying them marriage. As the district attorney framed it, the rights enumerated in Article 14 of the 1917 Mexican Constitution—life, liberty, properties, possessions—did not specifically include marriage nor did Francisco and Julia competently argue that they did. Second, the district attorney speculated that even if marriage were to be considered a natural right, the government could still limit and protect that right through legislation and regulation. In his view, the benefits of Law 31's discrimination against Chinese were so obvious as to require no explication and he offered none. Third, regulation of marriage belonged to the states. Because the Constitution did not explicitly grant to the federal government power to regulate marriage, the states retained that power. Sonora, therefore, could deny marriage to Chinese men and Mexican women, if it chose to do so.Footnote 88

In a brief aside, the district attorney also suggested that if Francisco and Julia were, as they alleged, motivated by concern for the future and legitimacy of their children, they could travel to the neighboring states of Sinaloa or Chihuahua to effectuate their marriage.Footnote 89 As a solution to the difficulties faced by Francisco and Julia, this latter argument either failed to take account of Law 31's prohibition on cohabitation as well as marriage or assumed that the family would leave Sonora permanently. At the time, neither Francisco nor Julia could have known that many Mexican-Chinese families would be torn asunder or would leave Sonora altogether when Chinese were violently expelled from the state five years later.

The quandary of reconciling natural rights, nationality, and racial classifications, ran throughout arguments made by both sides, and through Judge Ruíz's reasoning in the case. On the one hand, Francisco and Julia's attorney emphasized that Francisco had been naturalized as a Mexican citizen; but even if he had not, Article 1 of the Constitution granted rights to “all individuals.”Footnote 90 In contrast, the district attorney contended that Francisco's status as a foreigner—as he incorrectly referred to Francisco at first—or a naturalized Mexican, was not particularly relevant. Whatever Francisco's status, or even Julia's, the Constitution did not protect their right to marry. In the district attorney's view, whether marriage was a natural right was immaterial, because it was not mentioned explicitly in the Constitution. In his decision, Judge Ruíz referred to Francisco as “of Chinese race,” but ignored both Francisco's former Chinese nationality and his existing Mexican nationality by naturalization.Footnote 91 The judge, in contrast, referred to Julia Delgado as “of Mexican nationality.”Footnote 92 Although Judge Ruíz's denial of amparo did not explicitly rest on race, nationality, or natural rights, his racial references to Francisco and failure to acknowledge Francisco's Mexican nationality suggest that racial prejudice may have influenced his reasoning. In any case, Judge Ruiz did not identify Francisco as Mexican. Rather, in Judge Ruiz's analysis, Francisco stood outside the racialized ideal that informed the postrevolutionary Mexican national identity.

Ultimately, and in contrast to earlier amparo cases resting on the same arguments, Judge Ruíz found to be lacking the constitutional basis for the right to marry that Julia and Francisco asserted. Judge Ruíz considered that Sonora had validly enacted Law 31 within Mexico's “representative, democratic, and federal regime”; regulation of marriage belonged to state governments rather than to the federal government.Footnote 93 Moreover, he weighed heavily the public interest, Sonora's interest, in regulating marriage as “the legal means for family formation, the base of social organization.”Footnote 94 Clenching the negative judgment, Judge Ruíz agreed with the district attorney that Articles 1 and 14 of the 1917 Constitution did not guarantee civil marriage as a natural right. Julia and Francisco received no amparo.

Francisco Gim: The 1929 Petition

In late 1929, Francisco again sought amparo against enforcement of Law 31, this time on his own without Julia's specific legal involvement as a petitioner.Footnote 95 Although Julia had joined Francisco in the earlier petition in 1926 when Cananea's civil registrar denied them permission to marry, Chinese men brought a majority of the Law 31 amparo petitions alone. Government officials directed the enforcing fines and imprisonment against Chinese men rather than against their Mexican partners. Similarly, amparo required some sort of demonstrable harm or application of the law to the petitioner rather than a facial challenge as such.Footnote 96 Therefore, Mexican women's legal standing to challenge the fines and imprisonment their Chinese partners faced was limited. The nature of amparo and the enforcement practices of government officials in Sonora limited a Mexican woman's ability to use federal court and the amparo process to assert a right to marry her Chinese partner.

Francisco himself signed the complaint presented to Judge Joaquín Silva on September 5, 1929, but designated Salvador López Alvarado as the attorney to “hear notices.”Footnote 97 López Alvarado drafted the complaint in the first person, as if Francisco were speaking directly to the court rather than through his attorney. The complaint stated that Francisco and Julia had repeatedly sought to marry civilly in order to “normalize our life within legal precepts,” and to afford her and their children legal protection.Footnote 98 In August 1929, as they had done repeatedly before, Francisco and Julia appealed to Sonora's governor—no longer Alejo Bay but now Francisco S. Elías—to authorize their marriage. Perhaps annoyed by that particular request or by Francisco and Julia's persistence, Governor Elías's office directed the police chief of Naco to impose Law 31's sanctions. On August 27, the police chief summoned Francisco to the station where he imposed a fine of 200 pesos “for living in the company of Mrs. Delgado.”Footnote 99 When the police chief gave him ten days to pay the fine, Francisco quickly sought amparo in federal court, despite his earlier loss in the same venue.

Under López Alvarado's guidance, Francisco's petition in 1929 revealed a much different strategy for arguing against enforcement of Law 31 than had his petition with Julia in 1926. Gone were the rights arguments based on Articles 1 and 14 of the Constitution, which had proven futile in 1926, although successful for earlier petitioners. Rather, López Alvarado took hold of the government's successful 1926 argument regarding the constitutional division of powers between the federal and state governments and expanded it to international law.

The petition argued that on the national level, Article 73(26) of the 1917 Constitution reserved to the federal congress all power to legislate regarding foreigners and foreign interests. Similarly, Article 32 of the federal 1886 Law of Alienage and Naturalization provided that only federal law could modify or restrict the civil rights enjoyed by foreigners. Therefore, federal law preempted Law 31 as a state effort to limit the rights of foreigners to marry. At the international level, the petition turned to the FCN Treaty between Mexico and China signed in 1899. This FCN Treaty, the petition argued, established reciprocity between Chinese citizens in Mexico and Mexican citizens themselves. In other words, “all Chinese citizens in Mexico enjoy the same rights and concessions which Mexicans or the subjects of the most favored nation enjoy.”Footnote 100 Francisco summarized the federalism and international law argument: “If [Law 31] against which I seek amparo is out of step with the various federal laws cited [including the FCN Treaty], and in fact contains provisions which directly conflict with them, this law violates individual rights, and, therefore, the state legislature has invaded the sphere of federal authority.”Footnote 101 These two arguments—that federal law preempted state efforts to limit the rights of foreigners and that the FCN treaty required reciprocity for Chinese citizens—depended upon the assumption that Francisco was a foreigner not a Mexican national.

The petition then made an alternative argument centered on constitutional provisions defining Mexican identity: Francisco was in fact a Mexican national, not a foreigner. He had complied with the procedures set forth in Article 30(II)(b) of the Constitution to be naturalized as a Mexican citizen; therefore, he was entitled to all the protections and rights that the Constitution set forth, particularly Article 16's guarantee that individuals not be “molested in their person, family, home, papers, or possessions” without proper legal procedures. He likewise argued that enforcement of Law 31 violated Article 29 of the 1886 Law of Alienage and Naturalization, which equipped naturalized citizens with all the rights and obligations of native-born Mexicans.

By presenting alternatives, first arguments that depended upon Francisco's status as a foreigner, and then arguments that depended upon his naturalization as Mexican, Francisco's attorney employed a standard litigation tool. In this case, however, alternative arguments reinforced the doubts, the near schizophrenia, about Francisco's identity that characterized the arguments and judicial reasoning in the failed petition in 1926: was Francisco Chinese or was he Mexican? Did he have a place in the emerging Mexican national identity?

The alternative arguments likewise undermined and challenged the fundamental nature of Mexican law and federalism. Did federal law, constitutional and statutory, make a foreigner into a citizen? The obvious answer seems to be yes: federal law governed national citizenship. Francisco presented the appropriate federal documents to prove his naturalization. But, the willingness to present arguments that depended upon Francisco's status as a foreigner, demonstrated uncertainty about federal power to make him Mexican. As a state, Sonora reinforced that uncertainty and asserted its own independence within the federal system through its treatment of Chinese. Sonora essentially refused to recognize the power of federal law to make Chinese into Mexican citizens. Law 31's prohibitions applied expressly to Chinese who had been naturalized as Mexican citizens.Footnote 102 The 1931 employment law likewise refused to count as Mexicans, those Chinese who had been naturalized.Footnote 103 Despite his formal naturalization, Francisco was not Mexican enough, in law or in fact, to escape discrimination in Sonora or enforcement of Law 31. Francisco's amparo petition challenged his exclusion from the Mexican national/racial ideal, but did so ambivalently.

Almost as an afterthought, Francisco's attorney López Alvarado made two final arguments with respect to procedure and authority in the 1929 amparo petition: i) the 200 peso fine that the police chief imposed clearly exceeded the 15 peso limit that the organic law of Sonora allowed municipal functionaries to apply; and ii) the 200 peso fine (multa) was in fact a punishment (pena) that could constitutionally be imposed only through the judicial process required by Article 21 of the federal Constitution.Footnote 104

In the end, Judge Silva ruled that Law 31 and the sanctions imposed by the Naco police chief simply did not violate any rights Francisco may have had, either through the Constitution, through Article 29 of the Law of Alienage and Naturalization, to judicial process, or otherwise. Judge Silva denied amparo, and the 200 peso fine stood. In an aggressive move that characterized only a few Chinese amparo petitioners, five days later, on October 9, 1929, Santiago López Alvarado appealed to the Mexican Supreme Court on Francisco's behalf.

The Supreme Court and the Federal Congress Weigh In

In the Supreme Court appeal, López Alvarado changed strategy. He put himself, rather than Francisco, front and center. He identified himself as the attorney of record in the first line of the appeal, wrote in the third person rather than Gim's voice, and signed the appeal rather than having Gim do so as in the initial complaint. Gim would not speak for himself before the Supreme Court.

López Alvarado challenged Judge Silva's decision point by point, proffering eleven errors (agravios). The alleged lower court errors ranged from holding that Francisco had “consented” to Law 31 to the position that Law 31 did not invade federal powers regarding foreigners. The appeal ended on the same note as had Francisco's original petition: technical arguments regarding the police chief's authority to fine him. López Alvarado expanded those arguments slightly to include the position that the Sonoran State Constitution made a firm distinction between municipal authorities and police officers: police officers were not municipal authorities. Not only did the 200 peso fine exceed that authorized by the Sonoran State Constitution, but state law did not authorize the police chief to impose any fine at all.

The federal attorney general supported Francisco's appeal. He argued most emphatically for amparo on grounds of federalism. First, Law 31 regulated the rights of foreigners, a right reserved by Article 73 of the Constitution to the federal government. Second, even if Law 31 could be reconciled with Article 73, it still violated Francisco's constitutional and natural rights as a Mexican national. The attorney general posited the transformative power of federal law vis-à-vis Sonora's defiance. Francisco's naturalization secured to him the fundamental right to “constitute a family, the base of Mexican society.”Footnote 105 The denial of the right to marry and, even worse, the imposition of the fine infringed his rights, “inalienable rights that could only be modified or restricted by a disposition of the federal Congress, and never by a state law, which in all instances is subordinate to federal law.”Footnote 106 Federal law was supreme; amparo was the appropriate result.

The Second Chamber of the Mexican Supreme Court agreed, but not for the reasons the attorney general suggested. In a decision drafted by Justice Luís Calderón, the Chamber granted amparo to Francisco on September 23, 1930.Footnote 107 The heart of the decision was the technical procedural argument that López Alvarado tacked on at the end of the initial petition. The Chamber held that, under Article 21 of the federal Constitution, the imposition of punishments (penas) belonged to the judicial branch. Because Law 31 allowed administrative authorities to impose punishment and because non-judicial government officials had in fact imposed the 200 peso fine on Francisco, the Second Chamber voted unanimously for amparo against the fine, and voted three to two in favor of amparo against Law 31 itself.

The short, technical decision only hinted at the deep divisions the case prompted within the Chamber. In a single sentence, Justice Calderón explained that he voted for amparo because Law 31 was unconstitutional, not solely for the procedural reasons stated, but also because it contradicted federal law that provided to naturalized Mexicans all rights and obligations that native Mexicans enjoyed. In short, Justice Calderón understood federal law to be transformative and creative; despite Sonora's repeated efforts to the contrary, federal law could, and in this case actually did, make a foreigner into a Mexican.

Beyond the decision itself, El Universal, a major Mexico City newspaper, headlined the acrimonious oral debate among the Supreme Court justices, a debate centered as much around Mexican national identity as around the parameters of judicial decision making. Bold, block print letters marched across the top of the front page: “Before the Law, a Chinese Man and Justice of the Supreme Court are Equal” – Justice Calderón's position – and “We Must Save our Nationality” – that of Justice Urbina.Footnote 108 The article purported to be a virtual transcript of the oral debate in the Second Chamber.Footnote 109 Expanding on his single explanatory sentence in the decision itself, Justice Calderón argued that federal law provided the mechanism for naturalization and transformed foreigners into authentic Mexicans entitled to all the rights and obligations of the native-born.Footnote 110 He linked the unconstitutionality of Law 31 specifically to Sonora's invasion of the federal sphere, as Law 31 both restricted the rights of foreigners and more egregiously sought to restrict the rights of naturalized Mexicans.Footnote 111 Moreover, Justice Calderón saw Law 31 in unmitigated racial terms. It established “a hateful (odioso) distinction” based on race that was “truly repugnant” to the fundamental place, the fundamental value, of equality in ordering the Mexican state.Footnote 112 In oral debate, Justice Calderón urged the Chamber to grant amparo based upon Mr. Gim's Mexican nationality rather than denying amparo because of his race. He reminded his colleagues that “Mexico is a democratic country that is ordered by democratic institutions, before whose laws we are all equal: the Chinese Gi[m] and the Justices of this Chamber.”Footnote 113 For Justice Calderón, Mexican national identity centered around political principles of democracy and equality, not race.

Justice Urbina responded vigorously to the contrary, emphasizing the basic police powers of state government: Law 31 was not unconstitutional because States could freely legislate regarding the civil rights of their citizens, including prohibiting marriage for reasons of health or for what ever other reason the local legislature judged convenient.Footnote 114 Nonetheless, only a judicial authority, not an administrative one, was authorized to apply a punishment.Footnote 115 Justice Urbina voted for amparo on this technical ground.

More heatedly, Justice Urbina bristled at Justice Calderón's description of Law 31 as “hateful,” accusing Calderón of sentimentality and ignoring the national interest.Footnote 116 Reflecting his judicial philosophy, Justice Urbina went beyond both the facts of the case and legal principles, to discuss what he alleged was “a crisis of nationality” in Mexico.Footnote 117 He disclaimed any anti-Chinese bias, even while vigorously arguing that the federal government should exclude Chinese from Mexican territory because of the “great damage” Chinese caused in the states of Sonora, Sinaloa, and all along the Pacific Coast.Footnote 118 Chinese were “undesirable foreigners” who competed with authentic Mexicans for jobs, were willing to work for minimal pay, and brought racial diseases with them.Footnote 119 Excluding Chinese would be both “patriotic” and “just”; it was, moreover, “required” for the well-being of Mexico.Footnote 120 As a matter of judicial decision making, Justice Urbina believed a judge should take account of social concerns rather than limiting himself to strict application of the law. Mexican national identity did not include Chinese.

Justice Cisnero Canto, the president of the Second Chamber of the Supreme Court, sought to quell the fiery debate, noting that “the questions of social character and ethnology” Urbina and Calderón presented “were very interesting for their racial transcendence,” but unnecessary to the Chamber's decision.Footnote 121 The Chamber could resolve “the juridical constitutional problem” presented to it, but not engage in sociological study.Footnote 122 Justice Cisnero Canto brought the question squarely back to the law, to the legal issues at hand, rather than focusing on the contentious questions of nationality and national identity.

Justice Cisnero Canto thought the Chamber should grant amparo on legal grounds: a municipal authority was not constitutionally authorized to apply a punishment as had occurred in Mr. Gim's case.Footnote 123 Justice Cisnero Canto's view proved persuasive: the Second Chamber voted to provide amparo on this point.

The justices’ decision and its report in Mexico City newspapers prompted a pointed discussion in the federal Congress as well, a debate centered on the proper parameters of judicial decision making as well as Mexican nationality. The congressional deputies who spoke on the issue were all in favor of regulation of Chinese and limits on their immigration, but they differed as to the criteria judges should use to decide court cases. Walterio Pesquiera—now a representative from Sonora to the federal Congress rather than municipal president of Nogales—bemoaned the Supreme Court decision to grant Francisco amparo, calling Justice Calderón's opinion depressing, but Justice Urbina's hopeful.Footnote 124 A fellow deputy from Sonora, Juan de Dios Bátiz, challenged more directly the Second Chamber's decision and the process by which the Chamber arrived at its holding. As had Justice Urbina in the Supreme Court, Deputy Bátiz urged consideration of social consequences when judges decided cases, rather than the simple application of law: “I too, like my companion Citizen Pesquiera, call the justices to look beyond the legal question, to take into consideration the moral question and the question of nationalism, so that in future cases they have in mind that we as a people . . . are going to degenerate given the presence of the Oriental races; surely, we will go from bad to worse . . . .”Footnote 125 Deputy Julio Bustillos, from the state of Oaxaca, left no doubt about his enthusiastic support for the federal executive branch's efforts to regulate Chinese, but he defined the judicial role more narrowly, more legally.Footnote 126 In his view, a judge applied the law, no more and no less.Footnote 127 Therefore, the Second Chamber correctly decided the Gim case as the justices grounded their decision “strictly in the law, not judging it, but applying it, which is the correct role of a justice or judge.”Footnote 128 The decision followed “juridical criteria, the correct criteria, even though sociologically and even morally” the congressional deputies found the ruling distasteful.Footnote 129

With the Gim case in the media, lawyers in Mexico expressed different views on proper judicial decision making and national identity as well: “Some supported the thesis that Mr. Justice Calderon's position was juridically true and others that the ideas expressed by Mr. Justice Urbina were of such national transcendence and so great that they almost planted the problem from the point of view of the defense of the Hispanic-American race.”Footnote 130 When deciding a case, should a judge adhere strictly to positive law or take account of social conditions? The question divided Supreme Court justices, federal congressmen, and lawyers. The Gim case presented the question and a forum for discussion, but provided no firm resolution.

Beyond the appropriate criteria for judicial decision making, the newspaper reporter covering the Gim case lamented the technical resolution of the case and bluntly stated the fundamental question the Chamber left unanswered: “Can the states prohibit marriage based on race?”Footnote 131

Carlos Wong Sun: The 1929 Petition

When Santiago López Alvarado appealed to the Mexican Supreme Court on behalf of Francisco Gim in October 1929, the Court already had pending before it a Law 31 appeal, one brought in June 1929 on behalf of Carlos Wong Sun.Footnote 132 Despite its earlier arrival at the Court, Wong Sun's appeal was not decided until December 1932, more than two years after the Supreme Court granted amparo to Gim. Moreover, Wong Sun's case received none of the media attention that Gim's did, perhaps because it did not present the same challenge to the national racial consciousness and mestizo ideal.

As the only Law 31 challenges the Supreme Court heard, the Gim and Wong Sun cases were both similar and different. Gim and Wong Sun both sought amparo in 1929 against a civil registrar's refusal to grant them license to marry a Mexican partner. Federal district judge Joaquín Silva denied them both amparo, although the opinions themselves were different because the underlying facts were as well. Gim had been fined as well as denied a marriage license. Wong Sun had remained a Chinese citizen whereas Gim had been naturalized. And, Arsenio Espinosa—the former federal judge who had consistently granted amparo in Law 31 petitions in 1924 and 1925—was Wong Sun's attorney.

Arsenio Espinosa drafted Wong Sun's initial amparo petition as Santiago López Alvarado had drafted Gim's: in the first person as if the petitioner were speaking directly to the court rather than through his attorney. Espinosa's role as Wong Sun's advocate in the initial petition, is, however, easier to trace because, as an attorney, he presented the same legal arguments that he had made as a judge five years earlier: Law 31, on its face and in its application, violated Articles 1, 13, 14, and 16 of the federal Constitution.Footnote 133

Article 1's provision that “all inhabitants of the Mexican Republic enjoy constitutional guarantees” meant that “those who are residents of Mexico,” like Wong Sun, “have the same civil rights” as Mexican citizens.Footnote 134 Moreover, the Civil Code of Sonora set forth conditions for and impediments to marriage, all without mentioning race. In doing so, the Code merely provided a formal legal recognition of “a natural right of all human beings.”Footnote 135 By restricting the rights of Chinese individuals to marry, Law 31 violated Article 1 and, by implication, Wong Sun's natural rights as well, although Espinosa did not emphasize that point. Likewise, on its face, Law 31 violated Article 13's requirement that laws be generally applicable rather than specific to a particular racial group such as Chinese.

When the civil registrar in the town of Cucurpé applied Law 31 and refused to permit Wong Sun to marry Ramírez, the registrar violated Article 14's prohibition on deprivations of “life, liberty, properties, possessions or rights,” absent appropriate judicial process.Footnote 136 His actions also ran counter to Article 16's requirement that only competent legal authority could restrict rights or interfere with an individual and his family. The only argument missing from Espinosa's analysis was the one regarding federalism that he had earlier articulated as a judge: the supremacy provisions of the federal Constitution meant that it prevailed over conflicting state laws, such as Law 31.

Even if Espinosa had included the argument regarding federalism in Wong Sun's petition, it seems unlikely that it would have persuaded Judge Silva. Although Silva granted that marriage was a natural right, as a legal matter he saw it as “nothing more than a contract of social legitimacy.”Footnote 137 Because the federal Constitution did not regulate marriage, that right and responsibility remained with the states, which could, “as an exercise of their sovereignty,” set the terms and conditions for civil contracts as they saw fit.Footnote 138 Application of Law 31 to Wong Sun did not violate Article 14 because “while it is true that [Wong Sun] has the right to contract a marriage, it is no less certain that he cannot exercise that right in the State of Sonora, except in compliance with the terms set forth by the state Congress which regulates that contract.”Footnote 139

In conclusory fashion, Silva ruled that Law 31 did not violate Articles 1, 13, and 16 of the federal Constitution. Article 1 did not provide any “concrete individual guarantee” let alone the right to marry a Mexican woman.Footnote 140 There was no judicial decision at issue, therefore Wong Sun could not claim to have been “judged by private laws” in contravention of Article 13.Footnote 141 Denial of the right to marry simply did not violate Article 16.Footnote 142

Unlike Gim's appeal to the Supreme Court, in which Santaigo López Alvarado immediately identified himself as the attorney of record, Wong Sun's appeal continued in the first person. Likewise, only Wong Sun signed the petition; Arsenio Espinosa, as the attorney, did not. Still, Espinosa's influence is clear in the legal arguments made, particularly regarding Judge Silva's acknowledgement of marriage as a natural right. The appeal conceded that states could regulate the contract of marriage, but argued vigorously that the power “to regulate,” “to give form,” “to fix terms,” did not include the power to prohibit the exercise of a natural right.Footnote 143 Law 31 forbade Chinese men and Mexican women from exercising the natural right to marry, in contravention of Article 14 of the federal Constitution. Wong Sun's appeal likewise rejected Judge Silva's conclusory judgment regarding Articles 1, 13, and 16, arguing specifically that natural rights formed part of the national patrimony; therefore, depriving Wong Sun of his right to marriage certainly interfered with his constitutional rights.

When the Second Chamber of the Supreme Court finally decided Wong Sun's appeal in December 1932, it was if Gim's case had never come before it. The Chamber did not answer or even acknowledge the question it had left pending more than two years earlier: could a state prohibit marriage based on race? Rather, in a decision drafted by Justice Daniel Valencia, the Second Chamber stated firmly that Article 130 of the 1917 Constitution made marriage a civil contract.Footnote 144 Because marriage was a civil contract rather than an individual right, Sonora had “full sovereignty” to legislate on the subject and could prohibit marriage between Mexican women and Chinese men, if it chose to do so.Footnote 145 The miscegenation restriction articulated in Law 31 was simply “one requirement more” in the framework regulating the contract of marriage in Sonora.Footnote 146 Justice Valencia reasoned that the law did not deprive Carlos Wong Sun of any right, because neither he nor anyone else had a right to marry in the first place.Footnote 147 Marriage legislation belonged to the states; anti-miscegenation laws did not violate federal constitutional rights. Carlos Wong Sun received no amparo, Arsenio Espinosa's arguments regarding natural rights and expertise as a former federal judge not withstanding.

The three justices of the Second Chamber – Arturo Cisneros Canto, Daniel Valencia, and Luís Calderón – who voted in 1930 to grant amparo to Francisco Gim on all issues, also formed the majority in the Wong Sun decision in 1932. In the later case, however, the three changed their positions, voting to deny Wong Sun amparo, as did a fourth justice, José López Lira. The justices did not explain what changed their minds between September 1930 and December 1932 or even mention the Gim case. Even given the Otero Formula's severe limits on the precedential value of prior decisions, the failure to cite the Gim case is surprising given the relative proximity of the cases in time and the fact that they were the only Law 31 appeals the Supreme Court heard.

Admittedly, as noted previously, the facts between the two cases were somewhat different: Carlos Wong Sun was not a naturalized Mexican and no government official, whether municipal or judicial, had fined him in 1929. As a naturalized Mexican, Gim challenged the mestizo ideal and Mexican national identity in a way Wong Sun did not. But, those differences hardly seem significant enough to justify completely ignoring the earlier case, particularly given the controversy the Gim case generated regarding the proper parameters for judicial decision making and the acrimonious debate in the Second Chamber itself. The Chamber, nonetheless, decided Wong Sun's case quietly. The media silence contrasted vividly with the detailed reporting and bold headlines in Gim's case.

Although the popular media ignored the Second Chamber's decision to deny Carlos Wong Sun amparo in 1932, the decision was reported in the official publication of the Supreme Court, Semanario Judicial de la Federación; included in a compilation of select, important cases of the court for the relevant years; and is now available in the online database of the Mexican Supreme Court.Footnote 148 In contrast, however noteworthy the Gim case was in 1930 when the Supreme Court granted Francisco amparo, it was not reported in the Semanario Judicial de la Federación,Footnote 149 was not included in the compilation of important cases, and is not listed in the online database of the Mexican Supreme Court.Footnote 150 Perhaps Gim's case disappeared from the official, public record because of the technical grounds on which it was decided. Perhaps Wong Sun's case appears in that same record because it was resolved on the merits or because its treatment of federalism makes it more broadly relevant. Perhaps Gim's case disappeared to hide that, in Mexico, a Chinese man was equal to a justice of the Supreme Court. Francisco Gim's win, even if only on technical grounds, challenged the language of consensus that anti-Chinese rhetoric provided in creating a postrevolutionary Mexican national identity.

Resistance to Law 31 Outside Federal Court

The grand questions of constitutional interpretation, judicial process, and federalism that the Law 31 amparo petitions represent, easily overshadow individual experiences with race, gender, and marriage in the lived experience of that law. The experiences of Mexican women in particular may recede against the background of law, given that the Sonoran government directed enforcement of Law 31 primarily against their Chinese partners rather than the women themselves. In addition to their formal participation in amparo petitions, however, Mexican-Chinese couples navigated race and citizenship, marriage and family in their daily lives, when confronting the bureaucracy of government and the effects of Law 31.

In early October 1930, a few weeks after the Mexican Supreme Court granted Francisco Gim amparo, the Sonoran government sent out Circular 278 to the civil registrars in the state.Footnote 151 Circular 278 noted that, “with some frequency,” Mexican women continued to present for official registration their children procreated with “Chinese fathers.”Footnote 152 The circular identified the children as “proof of violation of Law 31” and ordered civil registrars to inform municipal authorities of each such registration to allow enforcement of Law 31.Footnote 153 The Mexican-Chinese children's mere existence undercut the power of Sonora and the emerging national/racial identity of mestizaje.

By presenting a child alone without the Chinese father on hand, a Mexican woman may have hoped to obtain a birth certificate without advertising her violation of Law 31. Circular 278 limited that strategy and suggested a stark choice for Mexican mothers: forego a birth certificate for a child or facilitate a partner's incarceration. However, the dilemma was not new. Mexican women who bore children with Chinese men had faced the same conundrum since Law 31 was passed seven years earlier and particularly in the five or so years since federal court judges ceased to grant amparo petitions against its enforcement. Faced with Law 31 and its enforcement, many Mexican women continued to bear children with Chinese fathers. Juana Ramírez, Carlos Wong Sun's partner, was one. She gave birth to a son, Carlos Wong Ramírez, in October 1932, more than three years after the civil registrar in Cucurpé refused them permission to marry and Judge Joaquín Silva denied amparo.Footnote 154 Juana and Carlos resisted Law 31 in other ways as well. Shortly after Judge Silva denied their request for amparo, Juana and Carlos slipped across the border to the United States. They were legally married in Nogales, Arizona on July 8, 1929.Footnote 155

When their son was born, Carlos's appeal against Judge Silva's first decision in 1929 was still pending before the Supreme Court, but the family had again suffered the repercussions of Law 31. In November 1931, Carlos sent a telegram to federal judge Manuel Gómez Lomelí seeking amparo against a fine of $1,000 pesos and an embargo on his property that the municipal authorities had imposed on him for living with Juana in violation of Law 31.Footnote 156 Carlos ratified the telegram in a more formal written petition the next day, representing himself without the aid of an attorney.

Carlos used his Arizona marriage with Juana to defend himself. He explained that they were not living in free union and presented the legal documents to prove it. Carlos said that he and Juana went to Arizona to marry because “the Laws that govern in the State of Arizona” did not prohibit marriage between “women of Mexican nationality and individuals of the Chinese race” as did Law 31 in Sonora.Footnote 157 And, like Francisco and Julia, Carlos and Juana wanted to marry for the benefit of their children: they had “procreated two children who of course need their father's attention and support as it would be inhuman to abandon them to their luck given their tender age and inability to sustain themselves.”Footnote 158 Carlos urged the court to recognize his marriage in Arizona, but Judge Gómez Lomelí refused.

On deciding the case, Judge Gómez Lomelí did not mention Carlos's earlier petition in 1929 nor its appeal pending before the Supreme Court. Likewise, no one – not Wong Sun as petitioner, the District Attorney as representative of the State's interests, or Judge Gómez Lomelí himself – cited the Supreme Court's decision in Francisco's case or the judicial relief Francisco had received on the technical grounds that a punishment (pena) imposed by non-judicial authorities created a constitutional violation. Judge Gómez Lomelí did not differentiate between punishments (penas) and fines (multas), as the Supreme Court did in Gim's case, but took a different tack. He categorized the $1000 which Carlos was supposed to pay for violating Law 31 as “ordinary income to the State.”Footnote 159 Because the money was “ordinary income to the State,” the new General Property Law of Sonora of December 17, 1931, required Carlos to first petition the “Court of Fiscal Infractions” for relief before he could seek amparo in federal court.Footnote 160 Because Carlos had not followed proper procedures, Judge Gómez Lomelí denied amparo.

Even with this second disappointment in federal court in 1931 and the rejection of their Arizona marriage, Juana and Carlos continued to resist Law 31 and the power of the state of Sonora. Juana gave birth to their son, Carlos Wong Ramírez, in October 1932. Similarly, in 1934 and 1936, when Carlos Wong Sun registered with the Mexican immigration service, as foreigners were required to do, he identified his formal civil status as “married” despite the fact that his Arizona marriage was not legally recognized in Sonora.Footnote 161 He also said that he had remained in Mexico since his arrival in 1904, although he had crossed the border into Arizona in 1929 to marry Juana and evade Law 31.Footnote 162

Like Juana and Carlos, Julia Delgado and Francisco Gim challenged Law 31 outside federal court as well as in it. Although they did not cross into the United States to legally marry, Julia in particular carefully navigated race and citizenship, marriage and family, when interacting with government bureaucracy. She claimed formal married status at times, but elided it when necessary.

Julia and Francisco lived together in Sonora in contravention of Law 31 during 1931 and through nearly all of 1932 even as thousands of Chinese left the state under duress or were violently expelled. Francisco finally left Sonora in September 1932, nearly a year after most of his compatriots were forced out.Footnote 163 The United States border agent at Naco, Arizona—where Francisco crossed into the United States in transit to Piedras Negras, Coahuila, Mexico—recognized Gim's middle class status and Mexican nationality, noting his occupation as a hotel keeper and the date of his naturalization.Footnote 164 At the same time, the agent underscored Francisco's Chinese race and lack of marriage: Francisco crossed the border as Gim Pon and signed his name in Chinese, almost as if the transformative experience of twenty years in Mexico had evaporated.Footnote 165 Julia was listed bluntly as “concubine.”Footnote 166 Aside from noting that his arrival contact was “a friend, Lt. Colonel Fortino Escobedo” in Piedras Negras, Francisco's border crossing card said nothing about what motivated his departure from Sonora, although it is easy to imagine that, despite the Supreme Court's grant of amparo, discrimination in Sonora simply became too much.Footnote 167

Nine months later, in June 1933, Julia and their children crossed into the United States briefly as well. On her border crossing card, Julia signed her name “Julia Delgado de Gim,” adding “of Gim” to her own last name in the form a married woman would use, and, on the back side of the card, listed her nearest relative as her “husband” Francisco Gim.Footnote 168 Through these small details, Julia named herself a married woman, married to a Chinese man in Sonora, claiming that status whether Law 31 allowed her to do so or not.

A small fuzzy picture attached to the border crossing card evidenced her further challenge to Law 31.Footnote 169 Her two older sons, Francisco and Guillermo, twelve and ten, stand by her side. The boys look strong and prosperous dressed in suits and ties, gazing directly at the camera, with a confidence more like the Latino-Indian mestizo that José Angel Espinoza celebrated in El ejemplo de Sonora than like the Mexican-Chinese child he denigrated. In her arms, Julia carries two-month old Jesús Régulo Gim, born nearly a decade after Law 31's passage and eighteen months after Circular 278, concrete evidence of her continued defiance of the law's prohibitions, despite her husband's absence from the picture and from Sonora.Footnote 170

Figure 4 Julia Delgado de Gim, Border entry card for arrival on December 5, 1946 at Naco, Arizona.

The same picture, only altered, appears on another border crossing document Julia obtained in December 1933.Footnote 171 The two older boys are cropped out and an x conceals Jesús's face, logical alterations given that the card was for Julia alone, but changes that also obscure her relationship with Francisco. The border crossing agent acknowledged the children, but challenged directly Julia's assertion that she was married to their father: “Alien has three children by a Chinese, one Gim Pon, who she says has departed to China . . . . It appears from the records of this office that this alien was not married to Gim Pon or Francisco Gi[m].”Footnote 172 She signed her name “Julia Delgado” without the “of Gim” that had asserted her married status less than six months earlier.Footnote 173 This acquiescence may simply have been a pragmatic move given the border agent's challenge. It may also have reflected an uncertainty about her relationship with Francisco. Had Francisco in fact “departed to China” or was he still in Piedras Negras, his stated destination just over a year earlier? This time, Julia listed her sister, Rita Delgado—who lived in Agua Prieta where Jesús was born—as her closest relative, rather than naming Francisco her husband as she had done in June.

It is not clear whether Francisco ever returned to live in Sonora after his 1932 departure. But, despite the uncertainty Julia's December 1933 border crossing document suggests and evidence that Francisco was living in Casas Grandes, Chihuahua, Mexico in 1944, Julia continued to hold herself out as married to him.Footnote 174 In 1946, fourteen years after Francisco left, Julia signed her name once again as “of Gim” and explicitly listed her civil status as “married” on a third border crossing card.Footnote 175 She still ran the hotel on Madero Avenue in Naco that she and Francisco had started decades before, the hotel that Francisco listed as his last permanent residence when crossing the border in 1932.Footnote 176 Similarly, over the years on their own border crossing documents, the couple's children Francisco, Guillermo, and Jesús consistently named themselves as children born in wedlock, providing first their father's last name and then their mother's— Gim Delgado—rather than using only their mother's last name as natural children would.Footnote 177 On their documents, the children also asserted their mother's marriage by naming her “Julia Delgado de Gim.”Footnote 178