Introduction

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is a common and chronic mental health condition (APA, DSM-V, 2013). Sufferers report significant associated disability due to loss of income and decreased quality of life (Bobes et al., Reference Bobes, Gonzalez, Bascaran, Arango, Siaz and Bousono2001). Historically, the most common psychological treatment for OCD has been behaviour therapy in the form of exposure with response prevention (ERP), which is effective for a large proportion of patients (e.g. Foa et al., Reference Foa, Liebowitz, Kozak, Davies, Campeas and Franklin2005). However, up to 30% of patients report no benefit from ERP, with a 15–20% attrition rate during the early stages of treatment (de Haan et al., Reference de Haan, van Oppen, van Balkom, Spinhoven, Hoogduin and Van Dyck1997). Attempts to improve treatment outcomes have focused on the addition of cognitive techniques (Zivor, Salkovskis and Oldfield, Reference Zivor, Salkovskis and Oldfield2011). Evidence for the added benefit of a cognitive element to treatment is mixed (McManus, Grey and Shafran, Reference McManus, Grey and Shafran2008), but nevertheless CBT is now the recommended treatment for patients with mild to moderate OCD (NICE, 2005). Maximizing the effectiveness of CBT treatment for OCD therefore represents a major and on-going challenge.

Case formulation (CF) is a core component of CBT (Eells, Reference Eells2007). It aims to synthesize patient experience with theory and research in a patient-centred manner (Kuyken, Padesky and Dudley, Reference Kuyken, Padesky and Dudley2009). CF should be collaboratively co-created by the patient and therapist, evolve over the course of therapy, and emphasize patient strengths (Kuyken et al., Reference Kuyken, Padesky and Dudley2009). It is claimed that a good CF enhances the process and outcome of therapy by guiding the selection and sequence of appropriate intervention, enriching the therapeutic alliance and relieving patient distress (Bieling and Kuyken, Reference Bieling and Kuyken2003; Kuyken, Padesky and Dudley, Reference Kuyken, Padesky and Dudley2008). Whilst strongly advocated in CBT theory, few studies have investigated the claimed benefits of CF and little is known about how CF is used in routine practice (Beiling and Kuyken, Reference Bieling and Kuyken2003; Eells, Reference Eells2007; Kuyken, Reference Kuyken and Tarrier2006).

Zivor, Salkovskis and Kushnir (Reference Zivor, Salkovskis and Kushnir2013) investigated the quality of OCD CFs developed by CBT clinicians and found the average CF to be “poor”, increasing to “adequate” following a CF training workshop. Kuyken, Fothergill, Musa and Chadwick (Reference Kuyken, Fothergill, Musa and Chadwick2003) rated clinicians’ CBT CFs for depressed patients and found fewer than half (44%) to be “good enough”. CF quality has also been found to vary according to depth of clinical expertise (Eells, Lombart, Kendjelic, Turner and Lucas, Reference Eells, Lombart, Kendjelic, Turner and Lucas2005b; Kuyken et al., Reference Kuyken, Fothergill, Musa and Chadwick2003; Zivor, Salkovskis and Oldfield, Reference Zivor, Salkovskis and Oldfield2013). A limitation of these studies however is that they evaluated CFs generated from case vignettes, which fails to replicate the process of developing a CF with a patient in real time (Beiling and Kuyken, Reference Bieling and Kuyken2003).

Research investigating the effectiveness of CF has largely relied upon randomized control trials (RCTs) comparing outcomes of CBT with and without patient-centred CF; and has found CBT with patient-centred CF is no different or only marginally better (Emmelkamp, Bouman and Blaauw, Reference Emmelkamp, Bouman and Blaauw1994; Schulte, Kunzel, Pepping and Schulte-Bahrenberg, Reference Schulte, Kunzel, Pepping and Schulte-Bahrenberg1992). The reliability of RCTs in detecting difference has however been questioned due to the many factors that blur the distinction between standardized and individualized CBT (Wilson, Reference Wilson1997) and the failure to systematically evaluate CF quality (Schulte et al., Reference Schulte, Kunzel, Pepping and Schulte-Bahrenberg1992). Gower and Kuyken (Reference Gower and Kuyken2011) found therapists’ competence in CF was associated with better treatment outcomes among depressed patients, suggesting that CF may improve treatment outcome, but CF quality needs to be considered.

Chadwick, Williams and Mackenzie (Reference Chadwick, Williams and Mackenzie2003) used a mixed methodology to investigate the immediate impact of a two-session CF phase on symptoms and therapeutic alliance, for patients with psychosis. Patients reported feeling reassured and optimistic following the CF, but also worried due to perceiving problems to be complex and longstanding. Therapists (but not patients) reported a positive impact on the alliance, but no symptomatic gains were reported. Findings cannot, however, be generalized to OCD patients, due to the nature of the sample. Limited research to date suggests CF may have an impact on therapy process, but the impact on treatment outcome is unclear.

In summary, it is claimed that CF enhances the process and outcome of CBT. However, few studies have explored the quality and clinical impact of CF in routine practice and there is little disorder-specific evidence. Evidence concerning the manner in which CFs are developed in routine practice and how this relates to treatment process and outcome in a disorder-specific sample is therefore at a premium. This is significant for OCD patients, where there is high attrition rate and non response to standard CBT treatment. The aims of the current study were: (1) to define the timing, content and quality of CF in routine practice; (2) to use a single diagnosis group of OCD; and (3) to assess the immediate and overall impact of CF.

Method

Design and sample

The study used archived data of CBT for OCD offered in a psychotherapy service within the NHS, UK (N = 37; Houghton, Saxon, Bradburn, Ricketts and Hardy, Reference Houghton, Saxon, Bradburn, Ricketts and Hardy2010). The current study received ethical approval from a local research ethics committee. Data comprised session-by-session outcome measurement and audiotapes of each therapy session. Twenty-nine patients (13 males, 16 females) were included in the current study (78% of the original 37). All patients met the International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition criteria for OCD (ICD-10, F42; World Health Organization, 1992).

All therapists (N=8) met British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy (BABCP) accreditation criteria for registration with the UK Council for Psychotherapy and had between 2–10 years of post-qualification CBT experience. Each therapist treated between 2–6 clients. Prior to commencement of the original study, therapists received two refresher workshops on CBT for OCD. During the study, therapists attended a 1-hour supervision group on a fortnightly basis.

Measures

Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (YBOCS; Goodman et al., Reference Goodman, Price, Rasmussen, Mazure, Fleischmann and Hill1989). The self-completed version of the Y-BOCS consists of 10 items corresponding to the personally relevant OCD symptoms identified in the clinician administered YBOCS interview (Steketee, Frost and Bogart, Reference Steketee, Frost and Bogart1996). This measure was completed prior to each CBT session.

The Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation-Short Form (CORE-SF; Evans et al., Reference Evans, Connell, Barkham, Margison, McGrath and Mellor-Clark2002). This is an abbreviated version of the full 34-item version (Barkham et al., Reference Barkham, Margison, Leach, Lucock, Mellor-Clark and Evans2001) and measures generic psychological distress. This measure was completed prior to each CBT session.

The Agnew-Davies Relationship Measure (ARM-12; Cahill et al., Reference Cahill, Stiles, Barkham, Hardy, Stone and Agnew-Davies2012). This is an abbreviated version of the ARM-28 (Cahill et al., Reference Cahill, Stiles, Barkham, Hardy, Stone and Agnew-Davies2012) and was used to measure the therapeutic alliance. The client version was used for the present study, completed following each CBT session.

Intervention

Therapists provided CBT for OCD and treatment duration was not predetermined. Treatment was not manualized, but supervision and training ensured that all treatments included cognitive and behavioural approaches. Session content was recorded (by the therapist) at the end of each session on a Therapy Process Record (TPR).

Procedure

Step 1: Identifying CF sessions. The TPR identified CF sessions. Some therapists (n = 9) reported the development and presentation of the CF early and again later in treatment (indicating re-formulation). Only initial CF sessions were included.

Step 2: Identifying formulation narrative. For over half the cases (n = 17) development and presentation of CF were reported as occurring within the same sessions. When this was not the case, development of CF always preceded presentation of CF. Sessions during which CF was presented were selected for analysis (n = 70).

Audiotapes of the selected CF sessions were listened to by the first author and passages relating to CF were identified and transcribed. Exclusion and inclusion criteria were developed using the Eells, Lombart, Kendjelic, Turner and Lucas (Reference Eells, Lombart, Kendjelic, Turner and Lucas2005a) guidelines in their Case Formulation Content Coding Manual (CFCCM v2). Table 1 lists exclusion and inclusion criteria for the study. For cases where the start of the CF presentation was not clear (n = 12), the audiotape from the previous session was also listened to and passages meeting the inclusion criteria included. An additional researcher independently analyzed three cases, using the same criteria. There was full agreement on the CF passages corresponding to these patients.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for CF content and quality coding

Step 3: Preparation of the transcripts. Transcripts were segmented into “idea units” (IUs) using the Stinson, Milbrath, Reidbord and Bucci (Reference Stinson, Milbrath, Reidbord and Bucci1994) method, which divides text into small portions (usually a sentence or less) to represent an IU. Stinson et al. (Reference Stinson, Milbrath, Reidbord and Bucci1994) reported mean reliability estimates of 0.87 using this method. The number of IUs per CF ranged from 27 to 207 (mean = 108).Footnote 1

Step 4: Identifying formulation sessions. A maximum of two sessions per patient were selected for content and quality coding, as two was the modal number of CF sessions across the sample. For those patients where the therapist reported CF across more than two sessions (n = 13), sessions were ranked according to the number of IUs pertaining to CF. The two highest-ranked sessions were included in the analysis.

Step 5: Content and quality analysis of formulations. CF content and quality was assessed via the CFCCM v2 (Eells et al., Reference Eells, Lombart, Kendjelic, Turner and Lucas2005a), which has excellent interrater reliability (Eells et al., Reference Eells, Lombart, Kendjelic, Turner and Lucas2005b). The CFCCM v2 categorizes CF content according to three main categories: (1) descriptive; (2) diagnostic; and (3) inferential - with each category containing several specific CF elements. For the purpose of this disorder-specific research, coding categories remained static, with additional OCD descriptors added. Specifically, the dysfunctional thoughts category was elaborated to include unhelpful beliefs about symptoms (e.g. negative appraisals); the safety behaviours category was elaborated to include behaviours to prevent symptoms from occurring (e.g. avoidance) and the affect regulation category was elaborated to include behaviours adopted in response to OCD symptoms (e.g. checking). Therapy interfering events referred to possible obstacles to treatment; and positive treatment indicators referred to patient's strengths.

The CFCCM quality coding system has six indices and includes: (1) formulation elaboration; (2) precision of language; (3) complexity; (4) coherence; (5) systematic process; and (6) comprehensiveness. The first five criteria are measured on a 5-point scale (0 = not present; 1 = rudimentary; 2 = adequate; 3 = good; and 4 = excellent) whilst the sixth criterion (comprehensiveness) was measured on a 9-point scale. For the purpose of analysis, this was transformed into a 0–4 scale. A global quality rating was achieved by summing each individual quality rating, resulting in a score between 0 (no quality) to 24 (maximum quality). This was transformed into a scale of 0 – 4 and assigned the same category labels as the independent criteria.Footnote 2 Evidence of written CFs was available for only four cases, so not included in the study.

Step 6: Recruiting and training raters. Three independent raters were used, each with prior experience of treating OCD with CBT and were blind to treatment outcome. Raters attended a 3-hour training session on OCD-CBT CF and treatment and received 2 days of CFCCM training. Raters were required to achieve a level of reliability of >.75 against the content codes on the example CFs (developed by the research team). Raters’ understanding of the quality codes was assessed via discussion about the quality of the example CFs. The Kappa statistic was used to establish interrater agreement for content coding (Siegel and Castellan, Reference Siegel and Castellan1988) and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was used for interrater agreement for quality coding (ICC; Shrout and Fleiss, Reference Shrout and Fleiss1979). The goal of the content coding step was to achieve a set of reliable consensus codes for each IU in a CF. All three raters coded the same CF session independently, and then immediately held a consensus meeting. Consensus was defined as at least two raters assigning the same code. Interrater reliability for content and quality across every CF obtained a multi-rater kappa coefficient 0.64, suggesting good agreement across content coding categories (defined as .60 – .80; Cohen, Reference Cohen1968). The ICC yielded an overall reliability estimate of 0.75 across quality ratings. Independent quality ratings ranged from 0.92 (complexity), 0.88 (systematic process), 0.78 (elaboration), 0.76 (precision of language) and 0.73 (coherence), indicating excellent interrater reliability across quality coding categories (defined as >.74; Fleiss, Reference Fleiss1981).

Data analysis

Pre–post YBOCS and CORE-SF scores were analyzed to identify individual rates of both reliable and clinically significant change (Jacobson and Truax, Reference Jacobson and Truax1991) and associated group effect sizes (Cohen, Reference Cohen1988). To consider clinical impact of CF, contact with patients (and associated sessional outcomes) were divided into three phases: (1) an “assessment phase” defined as all sessions prior to the first selected CF session; (2) a “formulation phase” defined as the two selected CF sessions (where this was more than two, the two sessions with the highest number of IUs pertaining to CF were selected); (3) a “post-formulation phase” defined as the two sessions immediately following the two CF sessions. Whilst it is acknowledged that CF may have continued to be discussed and reviewed, phases were designed to capture any initial impact of CF introduction. CF impact was tested by comparing phase mean outcome scores and post hoc pairwise comparisons identified any significant phase differences. Relationship between CF quality and overall outcome was tested via correlational analysis at three different time points – the end of the formulation phase, the end of the post-formulation phase, and at the end of treatment.

Results

Pre–post outcomes showed a large effect size, d = .89 (Cohen, Reference Cohen1988) on the Y-BOCS, with 31% of the sample achieving both a reliable and clinically significant reduction in OCD symptoms. Sample mean score was in the moderate-severe range at assessment (M = 23.9; SD = 7.54), falling to within the mild-moderate at termination (M = 17.14, SD = 8.74). A medium to large effect size, d = .72 (Cohen, Reference Cohen1988) was found on the CORE-SF, with 20% experiencing both a reliable and clinically significant change. ANOVA found no effect of therapist on treatment outcome on YBOCS F(7, 21) = .47, p = .85; or on CORE-SF F(7, 21) = .69, p = .68.

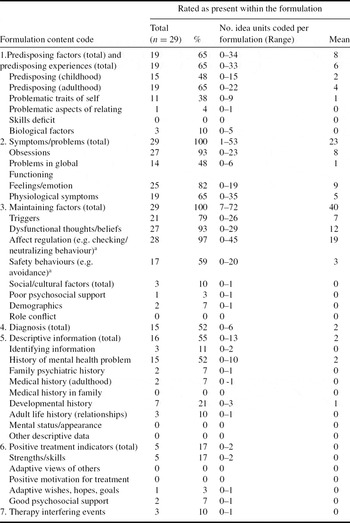

Every therapy contained a CF, with treatment duration ranging from 6 to 31 sessions (M = 13.52, SD = 6.02). CF development began between sessions 1 and 5 (M = 2.48, SD = 1.30) and took between 1 and 5 sessions (M = 2.34, SD = 1.11). CF presentation began between sessions 2 and 5 (M = 3.07, SD = 1.25) and typically lasted between 1 and 3 sessions (M = 2.41, SD = .71). Table 2 summarizes the content included in the CFs. Symptoms (mean 23 idea units per CF) and maintaining factors (mean 40 idea units per CF) were omnipresent. Affect regulation/compulsions (97 % of CFs), dysfunctional thoughts (93%) and triggers (79%) were the most frequently occurring maintaining factors. Predisposing factors were present within 65% of CFs, typically describing negative life events. Descriptive information was evident within 55% of CFs, with history of mental health problems included in 52% (although with a mean of only 2 idea units per CF). Positive treatment indicators (17%) and potential therapy interfering events (10%) were the least frequently occurring content in the CFs.

Table 2. Content of OCD case formulation in routine practice

a behaviour also commonly labelled “compulsions”

b total no. of idea units per formulation ranged from 27–207 (mean = 108)

The distribution of global quality ratings ranged from 9 to 23 with a mean of 14.83. Formulation quality scores were distributed as follows: rudimentary (n = 4; 14%), adequate (n = 11; 38%), good (n = 9; 31%) and excellent (n = 5; 17%). Elaboration achieved the highest mean quality rating (M = 2.72, SD = .80), followed by complexity (M = 2.53, SD = 1.02), coherence (M = 2.41, SD = .87), precision of language (M = 2.31, SD = .76), systematic process (M = 2.21, SD = 1.05) and comprehensiveness (M = 1.90, SD = 3.55).

In terms of CF impact, Table 3 presents the outcome mean scores according to study phase. Whilst there was a significant decrease in OCD symptoms (YBOCS; F(2, 56) = 3.83, p < .05), post hoc comparisons indicated no significant difference between phase pairs following Bonferroni correction (Abdi, Reference Abdi and Salkind2007). There was a significant improvement in psychological distress (CORE-SF; F(2, 56) = 9.56, p = .001) and an increase in the alliance (ARM-12; F(2, 56) = 6.62, p < .001). Psychological distress during the post-formulation phase (M = 14.81, 95% CI [11.55, 18.08]) was significantly lower (p < .01) than during assessment (M = 18.23, 95% CI [15.48, 20.99]) and formulation phases (M = 17.20, 95% CI [13.61, 20.80]). The alliance at the end of the post formulation phase (M = 75.41, 95% CI [72.34, 78.49]) was significantly higher (p < .05) than the alliance during the assessment phase (M = 70.28, 95% CI [67.07, 73.48]. The relationship between CF quality and outcome was tested across the formulation phase, post-formulation phase and end of treatment, with partial correlations controlling for intake scores. Table 4 illustrates that CF quality did not correlate with outcome at any of the study phases.

Table 3. Mean scores on outcome measures during therapy phases

*p < .05; **Mean scores significantly differ (p < .05) on pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction applied

Table 4. Partial correlations between formulation quality and outcome during study phases

*None of the correlations were significant at a level of p < .05.

Discussion

This is the first attempt to assess the timing, content and quality of CF in an OCD specific sample during routine CBT practice and to simultaneously assess the relationship with outcome. Findings indicate that therapists formulate early in the course of OCD treatment, always include symptoms and maintaining factors, and that CF reduces patient distress and improves the alliance. The most frequently noted aspect of OCD CFs were affect regulation (which includes compulsions) followed by dysfunctional thoughts/beliefs. This suggests behavioural and cognitive balance to OCD CFs in routine practice. Over half of CFs (65%) included predisposing factors, indicating that therapists often paid attention to historical factors. Positive treatment indicators such as patient strengths were rarely included, despite the prominence given to strength/resilience factors in CF theory (Kuyken et al., Reference Kuyken, Padesky and Dudley2009).

There was a range in overall CF quality, with less than half (48%) falling within the good to excellent range, despite specific training and on-going supervision. Findings are consistent with the notion that CF is one of the most complex skills in CBT (Kuyken et al., Reference Kuyken, Padesky and Dudley2008), suggesting a need for specialist training (Zivor et al., Reference Zivor, Salkovskis and Kushnir2013). However, simple descriptive CFs may in fact be appropriate during early stages of treatment (Kuyken et al., Reference Kuyken, Padesky and Dudley2009), with therapists limiting content to prevent patient and therapist feeling overwhelmed (Chadwick et al., Reference Chadwick, Williams and Mackenzie2003). In the current study, the CFs received the lowest rating for comprehensiveness (the number of different CF categories included) and highest for elaboration (the extent to which one single element was explained), supporting the idea that OCD CFs are kept relatively simple early in treatment. A limitation of the current study was the failure to capture attempts at reformulation later in treatment, as CF quality may vary according to stage of treatment (Kuyken et al., Reference Kuyken, Padesky and Dudley2009; Zivor et al., Reference Zivor, Salkovskis and Kushnir2013).

In terms of the immediate impact of CF, results indicate a reduction to distress and an increase in the alliance following CF. Sharing CFs may usefully “contain” patient distress by helping make sense of a potentially confusing array of symptoms (Eells, Reference Eells2007). It may take time for patients to effectively assimilate their CF (Stiles, Reference Stiles and Norcross2002) due to the mixed feelings CF can provoke (Chadwick et al., Reference Chadwick, Williams and Mackenzie2003). The alliance during the post-formulation phase significantly improved, suggesting that CF may be an important aspect of alliance formation. These findings would support claims made in theory that CF enhances the process of therapy (Bieling and Kuyken, Reference Bieling and Kuyken2003; Kuyken et al., Reference Kuyken, Padesky and Dudley2008). This is particularly important in OCD given the high rates of attrition early in treatment (de Haan et al., Reference de Haan, van Oppen, van Balkom, Spinhoven, Hoogduin and Van Dyck1997). Findings are, however, tentative given there was no control group to measure whether change would have occurred without CF. The study also lacked patient feedback, which would have helped establish the extent to which patients attributed change to CF.

Findings suggest that quality of the CF was not related to treatment outcome at any stage of treatment. It is possible that common factors within the CF process, such as the experience of being attentively listened to, are more important. Gower and Kuyken (Reference Gower and Kuyken2011) however did find a positive association between therapists’ competence in CF and treatment outcome. A major distinction between these studies was the measure of CF quality employed. The CFCCM focuses on the comprehensiveness and structure of the CF, whereas the Collaborative Case Conceptualization Rating Scale (CCC-RS; Padesky, Kuyken and Dudley, Reference Padesky, Kuyken and Dudley2011, as used in Gower and Kuyken, Reference Gower and Kuyken2011) places greater emphasis on collaboration and extent to which CF is matched to patient need, at different stages of treatment. It is possible that factors associated with the content and structure of CF are less important than the extent to which a “good enough” CF is co-created in a collaborative manner. Furthermore, the CFCCM assumes quality indicators are static and of equal weight (i.e. it is an additive scale), but the current findings suggest this might not be the case. Further research is needed to identify aspects of CF that are important in routine practice and how this may alter over the course treatment. Such research could be used to inform the development of simple, theoretically sound, disorder-specific measures of CF quality for research, audit and training purposes. Existing research offers examples of such measures that have been developed for use in specific studies e.g. Zivor et al. (Reference Zivor, Salkovskis and Kushnir2013) developed a brief, OCD-specific CF quality measure for their research. Further research could establish the applicability of these measures more widely.

For the purpose of this research, treatment was divided into distinct phases – assessment, formulation and post-formulation. Given the nature of this research, CF sessions could not be considered to have been concerned with CF exclusively, so the “impact” of CF may have been due to other factors. This criticism is especially cogent for the post-formulation phase, during which outcomes may have been related to other processes, such as application of evidence-based interventions. Such limitations reflect the complexity of conducting CF research with high internal validity in routine practice and may highlight the reason why practice-based CF research is so limited. The current study investigated the impact of CF on patient distress, symptoms and alliance. Given CF is thought to impact on these factors indirectly (Bieling and Kuyken, Reference Bieling and Kuyken2003), further research could explore the direct impact of CF, including its impact on patients’ understanding of their problems and the selection of interventions.

In conclusion, this research evidence suggests that CBT therapists are routinely using CF early in the treatment of OCD and this appears to have an immediate impact on reducing patient distress and on improving the therapeutic alliance. Such CF factors may therefore play an important role in reducing early attrition from OCD treatment. However, the mechanism by which these effects occur remains ill-defined and under researched. The relationship between CF quality and treatment outcome is less clear and this study has raised important questions about how CF quality is defined and measured and how this might vary depending on the presenting problem and stage of treatment. The prominent role that formulation plays in clinical practice has not yet been justified by the current evidence base.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.