On September 22, 2019, just like the former leader of the New Democratic Party (NDP) Jack Layton had done 8 years before, Jagmeet Singh appeared on the stage of Quebec'sFootnote 1 most-watched talk show “Tout le monde en parle.” After Layton appeared, his popularity in the province skyrocketed. For Singh, the situation was different—he had to face the elephant in the room right away. As a Sikh,Footnote 2 Singh wears a turban. He was first asked by the host how he reacted to the fact that “a lot of Quebecers, and Canadians, are opposed to a politician wearing a religious sign.” Singh said: “What I want to say to Quebecers is that I share the same values (…) I want to be an ally for Quebec and I can be an ally for Quebec.”Footnote 3 A few days later, at the Atwater market in Montreal, Singh encountered a man who told him to “cut (his) turban off” to “look like a Canadian.” “I think Canadians look like all sorts of people. That's the beauty of Canada,” Singh replied. Then, on October 21, the results of the election came in. The NDP suffered significant losses in Quebec. In 2011, with Jack Layton as the leader, the NDP had won 59 seats in that province. In 2019, the party managed to keep only one of them.

Of course, Singh is not only a new face in Quebec. His presence in the political arena greatly contrasts with normality, as Canadian party leaders, like in many other Western countries, are typically portrayed as white (Tolley, Reference Tolley2016), middle-aged men (Goodyear-Grant, Reference Goodyear-Grant2013). When Singh was elected leader of the NDP in 2017, he became the first person of color to lead a federal party in Canada. However, he may have faced a particular challenge in Quebec, as the provincial government is the only one in the country that adopted a law banning public servants from wearing religious garments. The fact that Singh wears a turban did not fail to attract local media attention. In fact, the question of secularism and the place religious garments should take in public spaces has been debated in that province for over a decade (Brodeur, Reference Brodeur2008; Leroux, Reference Leroux2010; Dalpé and Koussens, Reference Dalpé and Koussens2016; Tessier and Montigny, Reference Tessier and Montigny2016).

While research has previously looked at political behavior when there have been local candidates of color (e.g. Tossutti and Najem, Reference Tossutti and Najem2002; Black and Erickson, Reference Black and Erickson2006), evidence regarding the behavior toward individuals in leadership positions remains sparse in the Canadian case owing to the sheer rarity of these candidacies. As Besco (Reference Besco2019) explains, most of the research on affinity-voting comes from the United States and considers specifically Afro-American and Latino voters. Most notably, several authors analyzed support for Barack Obama (e.g. Walters, Reference Walters2007; Frasure, Reference Frasure and Gillespie2010; Piston, Reference Piston2010; Redlawsk et al., Reference Redlawsk, Tolbert and Franko2010). Evidence from countries that have adopted the Westminster system is not as prolific and seldom focused on leadership. Fisher et al. (Reference Fisher, Heath, Sanders and Sobolewska2014), for example, report that Pakistani candidates were favored by Pakistani voters in 2010 in Britain. In Canada, it has been shown that provincial party leaders or candidates running for mayor can be subjected to positive co-ethnic political behaviors (that is when voters support candidates who identify with the same ethnicity; e.g. Bird et al., Reference Bird, Jackson, Michael McGregor, Moore and Stephenson2016), but also to negative cross-ethnic attitudes (e.g. Bouchard, Reference Bouchard2020). Regarding local candidates, while evidence of positive co-ethnic voting has been reported (Landa et al., Reference Landa, Copeland and Grofman1995; Cutler, Reference Cutler2002; Berdahl et al., Reference Berdahl, Adams and Poelzer2011; Tolley and Goodyear-Grant, Reference Tolley and Goodyear-Grant2014; Besco, Reference Besco2015), there is little proof of a penalty suffered by candidates of color (Tossutti and Najem, Reference Tossutti and Najem2002; Black and Erickson, Reference Black and Erickson2006; Black and Hicks Reference Black and Hicks2006; Murakami, Reference Murakami2014; but see Besco, Reference Besco2018). One of the main problems faced by these authors is that voters are expected to pay particularly little attention to local candidates under plurality voting (Blais et al., Reference Blais, Gidengil, Dobrzynska, Nevitte and Nadeau2003; Stevens et al., Reference Stevens, Islam, de Geus, Goldberg, McAndrews, Mierke-Zatwarnicki, Loewen and Rubenson2019). In Canada, research has shown that leaders' images are far more important to voters (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Jenson, LeDuc and Pammett2019) and can influence their electoral behavior (Gidengil et al., Reference Gidengil, Blais, Everitt, Fournier and Nevitte2006).

Even though the case of Singh may seem parochial to a global audience, it offers an opportunity to analyze how voters first react to the presence of a non-prototypical candidate, or in other words, to a leader who appears, in many ways, outside of the norm. This article offers a first look at the attitudes toward Singh and his party, the NDP, before and during the campaign. For this purpose, we use data from the 2019 Democracy Checkup (DC) surveys (Stephenson et al., Reference Stephenson, Harell, Rubenson and Loewen2019a). Data were gathered online in the summer of 2019, before the electoral campaign began. Not only do these data allow us to evaluate first impressions of Singh, but it is likely that partisanship, which has been identified as an important mitigating factor of affinity-based or discriminatory political behavior (Hayes, Reference Hayes2011; Murakami, Reference Murakami2014; Street, Reference Street2014), was not as salient to voters at that time compared to during the campaign. Scholarship in social psychology shows that appearance-based cues are particularly influential at the beginning of social interactions (Fiske and Taylor, Reference Fiske and Taylor2017). The second survey used is the campaign period questionnaire of the Canadian Election Study (CES) (Stephenson et al., Reference Stephenson, Harell, Rubenson and Loewen2020), which gathered over 37,000 respondents. Our goal, this time, is to assess the impact of ethnicity in a high-information context while taking advantage of the larger number of respondents to assess the political behavior of Sikh Canadians. We focus on the evaluation of the NDP and the evaluation of Singh's traits as well as shifts in voting intentions for the NDP between 2015 and 2019.Footnote 4 We pay attention, in particular, to the attitudes and intended political behaviors of Sikh Canadians, Indian Canadians, Canadians of color, as well as citizens from different provinces and regions in Canada.

1. Jagmeet Singh and diversity in Canada

The demographic landscape in Canada is becoming increasingly diverse. Overall, 22.3% of Canadians self-identified in the 2016 census as a person of color, and 21.9% as immigrants. While Jagmeet Singh became the first federal party leader of color, other Sikh-Canadians have been elected as Members of Parliament (MPs). When Justin Trudeau first became Prime Minister in 2015, he named four Sikh MPs to his cabinet of ministers. In 2011, 1.4% of the population claimed Sikhism as their religious affiliation. While MPs can wear religious symbols and garments, such as a Sikh turban, in parliament, a strict separation of religion and government is observed.

Although Singh wears ostentatious religious symbols, he does not publicly make the promotion of Sikhism or Sikh values. Singh's political career has instead been focused on a social-democratic agenda including the promotion of women and LGBTQ+ rights in Canada. His party, the NDP, founded in 1961, is progressive, secular, and most commonly associated with labor unions rather than religious organizations (NDP, 2016).

2. Voters and politicians of color

2.1 The Canadian case

Despite increasing diversity in the West, political leaders, in particular, seldom defy norms. In Canada, few women have led federal parties. From a high of two female party leaders in 1993, only one remained in 1997. In 2004, there were none left. In 2006, however, Elizabeth May became the leader of the (marginal) Green Party of Canada. She became an MP in 2011 and remained, in 2019, the only woman in charge of a federal political party. The candidacies of Kim Campbell (Progressive Conservative) and Audrey McLaughlin (NDP) in 1993, in particular, attracted important academic attention, from the way they were treated by the media (e.g. Gidengil and Everitt, Reference Gidengil and Everitt2003) to how different groups of voters reacted to them (e.g. O'Neill, Reference O'Neill1998; Cutler, Reference Cutler2002). Cutler (Reference Cutler2002) notably presents leaders' sociodemographic characteristics as the “simplest shortcut of all” and claims that an increase in social distance between leaders and voters is met with a political penalty. However, as all leaders running in the 1993 and 1997 federal elections were Caucasians, Cutler could not consider the influence of leaders' ethnicity on voters' behavior.

As there was no federal party leader of color in Canada before 2017, authors have instead paid attention to the treatment of local candidates associated with ethno-cultural minorities at the federal level. Given that Canada has adopted a Westminster parliamentary system and that elections follow the first-past-the-post model or plurality voting, there is a limited number of successful political parties at the federal level. While Canada is a known exception to Duverger's law—which states that plurality voting in single-member districts leads to bipartism—the number of parties that successfully manage to elect at least one MP is rather limited in comparison to countries that have adopted a form of proportional representation. Before the 2019 election, five parties were represented in the House of Commons: the Liberal Party, the Conservative Party, the NDP,Footnote 5 and, to a lesser extent, the Green Party as well as the Bloc Québécois (BQ).Footnote 6 The relatively low number of parties leads to fewer opportunities for unconventional candidates, such as people of color or women, to become a federal party leader. Provincial political parties have nonetheless historically displayed more diversity. For example, in 2013, six out of the 13 provincial and territorial premiers were women. However, the number of the party led by a person of color has also remained more limited.

2.2 Co-ethnic and cross-ethnic voting

The most important body of literature regarding the influence of candidates' race on elections comes from the United States. Authors have notably sought to understand when and why white voters would be willing or not to support candidates of color. Expected behaviors from white voters range from aversive racism (Terkildsen, Reference Terkildsen1993) to extreme positive or negative reactions when faced with a “transgression” of race-based assumptions (Sigelman et al., Reference Sigelman, Sigelman, Walkosz and Nitz1995; Leslie et al., Reference Leslie, Stout and Tolbert2019). However, the authors report mixed evidence of discrimination at the polls based on the association with an out-group. For example, in an experiment, Sigelman et al. (Reference Sigelman, Sigelman, Walkosz and Nitz1995) found no negative effect of candidates' ethnicity on voting intentions. Meanwhile, Piston (Reference Piston2010) claims that white voters with higher levels of racial prejudice were more reluctant to support Obama in 2008.

It is claimed that voters are more inclined to support political leaders who resemble them (Cutler, Reference Cutler2002), although this increase in the likelihood of support is not automatic and unconditional. Notably, one's location on the left-right spectrum as well as the nature of the political offer at a given election are suspected of influencing the extent of the expression of affinity-related behaviors (Griffin and Keane, Reference Griffin and Keane2006; Bouchard, Reference Bouchard2020). We know that the cognitive process that leads to the social categorization of individuals one encounters is unavoidable (Allport, Reference Allport1954). However, in the case of candidates of color, while race-based stereotypes are automatically triggered, an individual may consciously choose to control them given their deeply held values or their awareness of social expectations and acceptability (Terkildsen, Reference Terkildsen1993).

The empirical evidence regarding positive co-ethnic voting, meaning when voters favor a candidate associated with their in-group, is relatively strong. As McConnaughy et al. (Reference McConnaughy, White, Leal and Casellas2010) explain, the presence of a politician of color in the political arena generates an “explicit ethnic cue” which can prime “ethnic considerations” in the in-group, especially if individuals report a high level of what is known as linked fate, the impression that one's fate is “dependent upon the fate of the larger ethnic group” (p. 3). Individuals who identify with a minority ethnic group would therefore be more likely to be interested in politics “under racialized contexts” (Barreto, Reference Barreto2007, 426). For example, Filindra and Orr (Reference Filindra and Orr2013) report that Latinos were significantly more optimistic about the future of their city, Providence, once led by a Latino mayor. Authors found evidence of heightened support for candidates of color among several groups in the United States, including Afro-Americans (Griffin and Keane, Reference Griffin and Keane2006), Latinos (Barreto, Reference Barreto2007), and Asians (Collet, Reference Collet2005).

Other factors could encourage co-ethnic voting. Scholars have shown that a political context deemed hostile to a specific group can encourage people who identify with that group to devote more attention to politics (Pantoja and Segura, Reference Pantoja and Segura2003a, Reference Pantoja and Segura2003b). Moreover, the literature on the descriptive representation of marginalized groups highlights how the presence of diverse politicians can have positive impacts. For example, Pantoja and Segura (Reference Pantoja and Segura2003b) show that Latino representatives slightly lower the reported political alienation felt by constituents who identify as Latinos, while Gay (Reference Gay2002) claims that Black voters are more likely to reach for their representative if they are also Black. The improvement of communication between citizens of color and their representatives can be particularly perceptible in a context of mistrust toward political institutions (Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge1999). There is, however, no clear consensus as to what exactly explains this affinity logic. Answers offered range from the impression that one's fate is bound to what happens to one's social group as a whole (Oliver, Reference Oliver2010) to an interest-based heuristic which places a candidate of color as representing a group's interests (Besco, Reference Besco2015).

Authors have also shown that this expected solidarity can even extend to members of other racial and ethnic minority groups, leading to what is known as a “rainbow coalition” (Besco, Reference Besco2015). It means that candidates who do not identify with a given group can nonetheless appeal to that group's “sense of shared identity” (Collingwood et al., Reference Collingwood, Barreto and Garcia-Rios2014; see also Alamillo and Collingwood, Reference Alamillo and Collingwood2017, 3). In the case of members of different marginalized groups, a shared experience of discrimination can lead to heightened intergroup solidarity (Craig and Richeson, Reference Craig and Richeson2014; Cortland et al., Reference Cortland, Craig, Shapiro, Richeson, Neel and Goldstein2017). One of the most notorious examples of a coalition is the increased support of Latinos for Barack Obama in 2008 (Piston, Reference Piston2010).

Given the prevalence of co-ethnic voting, as well as positive cross-ethnic voting among members of different marginalized social groups, we formulate the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1a: Sikh voters are more likely to evaluate Jagmeet Singh and the NDP positively.

Hypothesis 1b: Indian voters are more likely to evaluate Jagmeet Singh and the NDP positively.

Hypothesis 1c: Voters of color are more likely to evaluate Jagmeet Singh and the NDP positively.

Considering voting behavior, we expect voters of color to be more likely to choose the NDP:

Hypothesis 2a: Sikh voters are more likely to migrate to the NDP in 2019, and less likely to desert the NDP in 2019.

Hypothesis 2b: Indian voters are more likely to migrate to the NDP in 2019, and less likely to desert the NDP in 2019.

Hypothesis 2c: Voters of color are more likely to migrate to the NDP in 2019, and less likely to desert the NDP in 2019.

2.3 Comparing the Canadian case

There are nonetheless important differences between the Canadian and the American case, not only in terms of political institutions but also of the composition of their population and the historical relationships that have unfolded between various social groups. Events such as the American Civil War have undoubtedly had a complicated and lasting impact on interactions between Afro-Americans and white Americans. For example, Ehrlinger et al. (Reference Ehrlinger, Ashby Plant, Eibach, Columb, Goplen, Kunstman and Butz2011) report that exposure to a Confederate flag has a negative effect on one's willingness to support a black candidate.

Moreover, political dynamics in Quebec bring forward the issue of sub-national units with different majority populations. This interesting aspect of the Canadian case finds an echo in several other countries, such as Belgium, the United Kingdom, and Spain.

The literature on the impact of candidates' ethnicity on voters remains sparse in Canada. Considering candidates of color, Besco (Reference Besco2019) reports that Canadians of color are more likely to support a candidate associated with their in-group as well as other racialized candidates. Meanwhile, Tossutti and Najem (Reference Tossutti and Najem2002) report no quantitative evidence of race-based discrimination at the polls in Canada during federal elections, meaning that candidates of color were not penalized by white voters. Nevertheless, the candidates they met in their study expressed worries regarding the negative impact the color of their skin could have on the way they are perceived by white voters. Black and Erickson (Reference Black and Erickson2006) reach similar conclusions by finding no evidence of race-based discrimination. However, Besco (Reference Besco2018) claims that this apparent absence of discrimination could be explained by the fact that candidates of color more frequently run for left-wing political parties, while voters who are the most prejudiced against them would typically support right-wing parties (Archer and Ellis, Reference Archer and Ellis1994). He found that Conservative voters in Canada were more likely to discriminate against Conservative candidates of color, while this effect was not found in other parties. An observational report of discrimination toward a party leader of color comes from Bouchard (Reference Bouchard2020), who shows that claiming Canadian ancestry had a negative effect on the evaluation of Raj Sherman, leader of Indian descent of the Liberal Party in Alberta in 2012.

The literature proves that candidates of color in Canada can gain support from voters who identify as part of a minority ethno-cultural group, especially if it is the same as the candidates' (Besco, Reference Besco2015, Reference Besco2019; Bird et al., Reference Bird, Jackson, Michael McGregor, Moore and Stephenson2016). These candidates are, in fact, more likely to be nominated in the first place in districts with significant non-white populations (Black and Hicks, Reference Black and Hicks2006; Tolley, Reference Tolley2019), a phenomenon not unique to Canada (e.g. Highton, Reference Highton2004).

Parliamentary systems have not been subjected to much academic scrutiny (Goodyear-Grant and Croskill, Reference Goodyear-Grant and Croskill2011), which is why the case of Jagmeet Singh provides an important opportunity to assess how different groups of Canadians evaluated a leader of color. By considering specifically Sikh Canadians as well as Canadians of Indian descent, we focus on a distinctive characteristic of Jagmeet Singh, which is that he can be identified as a Sikh at first sight. Religion brings, in this case, another level of complexity. Banducci et al. (Reference Banducci, Karp, Trasher and Rallings2008) report that while they do not necessarily have an impact on voting behavior, headwear nonetheless influences candidate evaluations negatively. Like skin tone, ostentatious religious symbols act as a visual cue used by the human brain to associate a person with a particular social group. In other words, religious symbols carry social meaning (Mancini, Reference Mancini2008).

2.3.1 Regionalism in Canada

This issue of religious symbols is particularly relevant in the case of Quebec, a Canadian province with a long history of public debate surrounding secularism. Secularism is also a highly debated topic in other countries like France. Vox Pop Labs' (2018) post-electoral provincial study shows that 66% of respondents in Quebec believe public officials in a position of authority should be forbidden from wearing a turban. Fifty-five percent of them had similar views concerning school teachers. Meanwhile, 12% believed turbans should be banned from all public spaces. Opposition toward the kirpanFootnote 7 is greater, reaching 80% of disapproval when public servants in a position of authority are concerned. Even though Singh also wears this ceremonial knife underneath his clothing, it is not nearly as salient, nor as frequently discussed, as his turban, around which most of the debate and press coverage was centered. During the campaign, from September 11 to October 21, 536 news articles published in French in CanadaFootnote 8 mentioned Singh and the word “turban,”Footnote 9 while only 23 mentioned both Singh and the word “kirpan.”Footnote 10

Secularism has been part of the political debate in Quebec for over a decade. In 2007, Gérard Bouchard and Charles Taylor became co-chairs of a commission tasked with assessing the extent of cultural accommodation practices and ensuring that they “conform to Quebec's core values” (Bouchard and Taylor, Reference Bouchard and Taylor2008). One of their recommendations was to limit religious signs worn by a “restricted range” of officials. The issue was discussed once more when the secessionist Parti Québécois introduced Bill 60, known as the “Charter of Values,” in 2013. It included provisions forbidding all public servants from wearing ostentatious religious signs or symbols. Bill 60 led to social unrest, including several demonstrations by citizens who opposed it.Footnote 11 While the Parti Québécois government was defeated in 2014, before the bill could become law, in 2018 the newly elected Coalition Avenir Québec government adopted what became known as Bill 21. As a result, public servants in a position of authority, including teachers, are now banned from wearing religious symbols. No other province has adopted similar legislation.

Certain disparities in terms of electoral behavior are expected from Canadians who live in different places in the country, owing notably to variations in local political culture and institutions (Henderson, Reference Henderson2004). The electoral behavior literature in Canada recognizes regionalism as an important factor influencing voting (Henderson, Reference Henderson2004; Anderson and Stephenson, Reference Anderson and Stephenson2010; Stephenson et al., Reference Stephenson, Lawlor, Cross and Blais2019b). For example, living in the prairiesFootnote 12 is associated with a higher probability of supporting a Conservative Party while, by comparison, Ontarians are more likely to favor the Liberals (Gidengil et al., Reference Gidengil, Blais, Nadeau and Nevitte1999, Reference Gidengil, Blais, Everitt, Fournier and Nevitte2006).

Therefore, this article also focuses on differences in behavior among Canadians from different provinces toward Singh and the NDP. Owing to the intense political debates surrounding the issue of religious garments in that province, we consider how Quebecers reacted to Singh, and if their political behavior is similar to that of other Canadians'. Given Quebecers' apprehensions regarding religious garments, we expect the following:

Hypothesis 1d: Quebec voters are more likely to evaluate Jagmeet Singh and the NDP negatively.

Hypothesis 2d: Quebec voters are more likely to desert the NDP in 2019, and less likely to migrate to the NDP in 2019.

3. Research design and hypotheses

This study of Canadians' reaction to Singh uses two databases (see Table 1). First, pre-electoral data are analyzed through the DC (Stephenson et al., Reference Stephenson, Harell, Rubenson and Loewen2019a), a survey conducted in Canada outside of electoral periods. We use data from the summer of 2019 which include 5,074 online respondents (a non-probability sample). The data were collected from May to August, before the beginning of the 2019 election campaign. The second survey used is the 2019 CES—Online Survey (Stephenson et al., Reference Stephenson, Harell, Rubenson and Loewen2020). More precisely, we rely on the campaign period survey (CPS) (N = 37,822) to assert Canadians' view of Singh during the 2019 electoral campaign (September 11 to October 21). The team in charge of the CES gathered data representative of gender, language, as well as regional distribution in Canada. Both the DC and the CES are weighted to reflect the national demographic distribution in terms of gender, age, and education as per the 2016 Canadian census.

Table 1. Description of the samples

To determine the attitudes of voters toward Jagmeet Singh and the NDP at that time, we rely on four tests. In each case, several independent variables are included: voters' age, gender, education,Footnote 13 partisan affiliations, and level of racial prejudice. We also consider the evaluation of Jagmeet Singh as a control variable in Tables 3–5.

Partisans are divided into two groups, strong and weak partisans, using non-partisans as a baseline. Strong partisanship is a binary variable coding as 1 those who felt very strongly or fairly strongly associated with their party of choice. Meanwhile, weak partisans were coded 1 if they did not feel strongly associated with their party but nonetheless claimed a party affiliation. This distinction is made as weak partisans may be more flexible and, ultimately, more likely to adopt certain behaviors, such as migrating to a different party. The explanatory variables under scrutiny are voters' province of residence, religion, and ethnicity. As is often the case, Ontario is used as the baseline (see e.g. Merolla and Stephenson, Reference Merolla and Stephenson2007). We look specifically at the behaviors of Sikh Canadians (only in the CES), Indian Canadians, as well as Canadians of colorFootnote 14 (only in the DC). These choices were made according to the data availability as well as the number of respondents. For example, as there are 28 Sikh Canadians in the DC sample, we consider only Indian respondents in that survey. We assess Sikh Canadians' behavior with more scrutiny by using CES data. The base categories for these variables are respectively non-Sikh Canadians, non-Indian Canadians, and Canadians who do not identify as a person of color.Footnote 15

Regarding the dependent variables, we first consider the evaluation of the NDP on a thermometer scale from 0 to 100. To do so, we used the following question in both surveys: “How do you feel about the federal political parties below? Set the slider to a number from 0 to 100, where 0 means you really dislike the party and 100 means you really like the party.”

For the evaluation of Singh specifically, there was no thermometer question in the DC. We, therefore, built an additive scaleFootnote 16 for that survey using the following questions:

• Which party leader(s) below do you think is/are intelligent? (Select all that apply)

• Which party leader(s) below do you think provide(s) strong leadership? (Select all that apply)

• Which party leader(s) below do you think is/are trustworthy? (Select all that apply)

• Which party leader(s) below do you think really care(s) about people like me? (Select all that apply)

Each time, selecting Jagmeet Singh as one of the chosen leaders is coded 1. The maximum score one could obtain was therefore 4. We do not consider other leaders that may also have been selected by the respondents.Footnote 17 Questions related to the attribution of positive traits are not as straightforward and blatant as a direct evaluation of Singh (Whitley and Kite, Reference Whitley and Kite2010). The variable used in the CES is a thermometer scale ranging from 0 to 100 with the following question: “How do you feel about the federal party leaders below (Jagmeet Singh)? Set the slider to a number from 0 to 100, where 0 means you really dislike the leader and 100 means you really like the leader.”

As mentioned, these data are used to test the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1a: Sikh voters are more likely to evaluate Jagmeet Singh and the NDP positively.

Hypothesis 1b: Indian voters are more likely to evaluate Jagmeet Singh and the NDP positively.

Hypothesis 1c: Voters of color are more likely to evaluate Jagmeet Singh and the NDP positively.

Hypothesis 1d: Quebec voters are more likely to evaluate Jagmeet Singh and the NDP negatively.

Finally, voters were given the opportunity to indicate which party they voted for in 2015, as well as which party they intended to vote for in 2019. In both surveys, by using these two questions, “desertion” and “migration” variables were created. A “deserter” is a person who voted for the NDP in 2015 but who does not intend to vote for them again in 2019. A “migrant” is a person who did not vote for the NDP in 2015 but who intends to support them in 2019.Footnote 18 We look at the influence of the chosen explanatory variables on these two behaviors to evaluate the last set of hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2a: Sikh voters are more likely to migrate to the NDP in 2019, and less likely to desert the NDP in 2019.

Hypothesis 2b: Indian voters are more likely to migrate to the NDP in 2019, and less likely to desert the NDP in 2019.

Hypothesis 2c: Voters of color are more likely to migrate to the NDP in 2019, and less likely to desert the NDP in 2019.

Hypothesis 2d: Quebec voters are more likely to desert the NDP in 2019, and less likely to migrate to the NDP in 2019.

3.1 Measuring prejudice

As mentioned, we control for voters' attitudes toward minority groups through a prejudice scale in all models. This additive scale includes voters' reaction to the following statements/questions in the DC:

• Too many recent immigrants just don't want to fit into Canadian society.

• Immigrants take jobs away from other Canadians.

• We should look after Canadians born in this country first and others second.

• Do you think Canada should admit: more immigrants, fewer immigrants, or about the same number of immigrants as now?Footnote 19

Thermometer questions are also included in these scales. Using the question, “How do you feel about the following groups?” we focus on DC respondents' feelings toward racial minorities, immigrants, and Muslims living in Canada. CES questions used to build the second racial prejudice scale were the following:

• How much should the federal government spend on immigrants and minorities?

• Do you think Canada should admit: (more immigrants, fewer immigrants, about the same number of immigrants as now)?

Feelings toward racial minorities and immigrants were also included using the following question: “How do you feel about the following groups? Set the slider to any number from 0 to 100, where 0 means you really dislike the group and 100 means you really like the group.”

Prejudice—the attitude one has toward a given group (Dovidio et al., Reference Dovidio, Hewstone, Glick and Esses2013)—is complex to measure. The utility to consider voters' feelings toward immigrants and Muslims in Canada could be questioned in this case, given the fact that Singh is not Muslim and that he was born in Canada. However, instead of specifically targeting one's attitude toward “racial minorities,” we look at one's general disposition toward a wider ensemble of marginalized groups which may also be associated with racialized individuals. In other words, the extent of the respondents' overall expression of racial prejudice is considered. In social psychology, scales grouping attitudes toward an ensemble of out-groups are frequently used to assess “generalized prejudice” (e.g. Ekehammar and Akrami, Reference Ekehammar and Akrami2003). As Akrami et al. (Reference Akrami, Ekehammar and Bergh2010) explain, “research has found prejudice toward various targets to be significantly correlated.” Following a factor analysis, we find that the DC scale presented in this article has a Cronbach's α of .88 and a first eigenvalue of 4.05. As for the CES, the racial prejudice variable has a Cronbach's α of .83 and a first eigenvalue of 2.66. Both are well above conventionally accepted thresholds for internal consistency and validity. In other words, these scales appear to capture a latent variable, namely racial prejudice. This concept is relevant to the analysis of the perception Canadians had of Singh.

4. Results

4.1 Evaluating Singh and the NDP

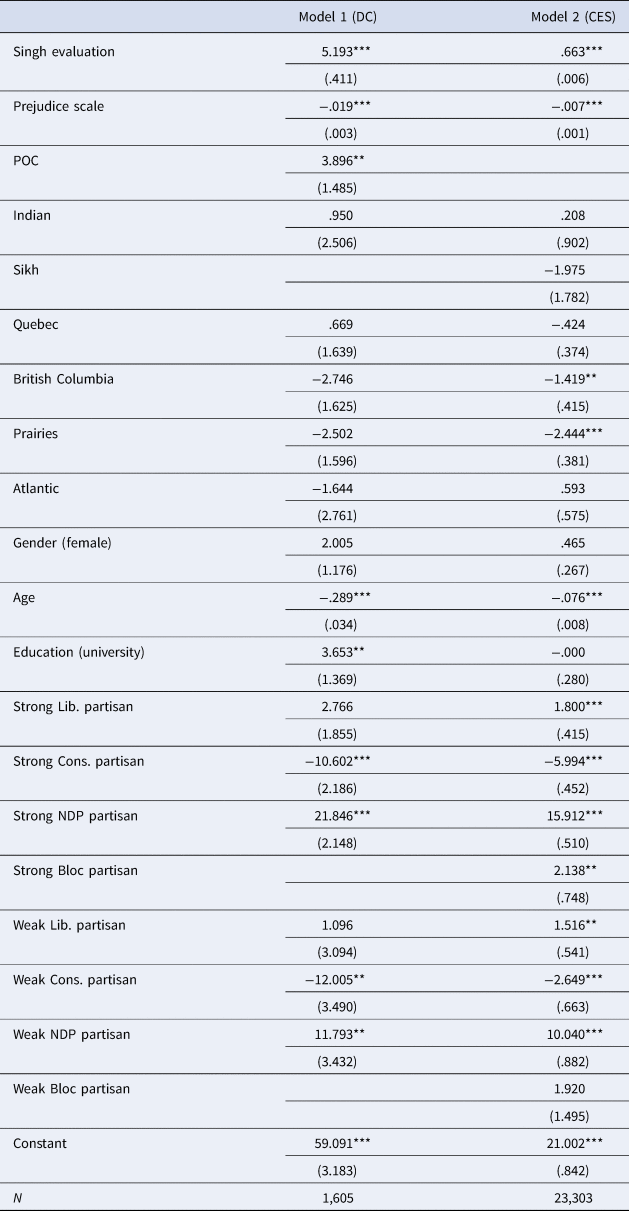

To answer the first set of hypotheses, we consider, in Tables 2 and 3, the impact of voters' characteristics on their evaluations of Singh and the NDP, respectively. Both tables use linear regressions. In Table 2, model 1 uses DC data and controls for voters' age, gender, partisan affiliation, education, and racial prejudice.

Table 2. Influence of Voters' Characteristics on the Evaluation of Jagmeet Singh

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Table 3. Influence of Voters' Characteristics on the Evaluation of the NDP

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Table 4. Influence of Voters' Characteristics on Intended Desertion from the NDP

Note: Binomial logistic regressions.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Table 5. Influence of Voters' Characteristics on Intended Migration to the NDP

Note: Binomial logistic regressions.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Table 3 uses similar models but adds the evaluation of Singh as a control variable.

We begin by considering the effect of the control variables on the evaluation of Jagmeet Singh. While no variable has a significant impact on the evaluation of Singh in model 1, in model 2, gender and age are both statistically significant. Conforming with theoretical expectations regarding the gender gap in support for left-wing political parties (Inglehart and Norris, Reference Inglehart and Norris2000) as well as the traditional behavior of NDP supporters in Canada since 1993 (Bouchard, Reference Bouchard2020), women are more likely to approve of Singh (2.3 in model 2). In model 2, Liberal partisanship is also associated with a more positive evaluation of Singh (5 for strong partisans and 4.87 for weak partisans), while Conservative partisanship has a negative impact on this variable. Lastly, as expected, NDP partisanship has a significant positive effect on the evaluation of Jagmeet Singh in both models.

Both models also show a statistically significant negative impact of living in Quebec on the approval for Jagmeet Singh, even when we control for racial prejudice. Racial prejudice itself also has, in both cases, a statistically significant negative impact on the evaluation of Singh.

Regarding hypotheses 1b and 1c, Table 2 shows that Indians report a more positive evaluation of Singh, but the effect is only statistically significant in model 1, which entails that this effect could be driven by Sikh Canadians (as model 1 does not control for Sikhism). Model 2 shows, as expected, that Sikh Canadians grant a significantly better rating to Singh by 7.55 points.

As for hypothesis 1d, both models in Table 2 show that living in Quebec has a significant negative statistical impact on the evaluation of Singh's traits. Even when we control for prejudice, the effect remains robust, which leads us to believe that animosity toward Singh cannot be explained solely by racial prejudice.

Table 3 focuses on the evaluation of the NDP. Once more, we first consider the control variables. As previously, strong Conservative partisanship has a statistically significant negative impact on the dependent variable in both models (−10.6 and −5.99, respectively), while strong NDP partisanship has an even greater positive influence (21.84 in model 1 and 15.91 in model 2). Weak NDP partisanship has a slightly more modest effect at 11.79 and 10.04, respectively.

It is relevant to notice that only Canadians of color show significant positive support for the NDP (3.89). In both models, the impact of Indian ancestry is insignificant, as is the Sikh religion in model 2. These results contrast with those obtained in Table 2: overall, it appears that Sikh Canadians displayed personal support for Singh, but that it did not extend to his party, the NDP. Meanwhile, the situation appears reversed for people of color, which raises questions regarding the existence of a “rainbow coalition” in this case and undermines hypothesis 1c. For an assessment of the interaction between ethnicity, the evaluation of Singh and prejudice, see the Appendix (Table A.1).

Table 3 also brings an important nuance to hypothesis 1d by showing that even though living in Quebec has a significant negative impact on the evaluation of Singh, the same cannot be claimed about the NDP. In both models, the relationship between living in Quebec and the evaluation of the NDP is not statistically significant. It, therefore, appears that animosity in Quebec was mostly directed at Singh rather than at his party. However, Quebec is not the only province critical of either Singh or the NDP: living in the prairies (model 2) has a negative impact on the evaluation of Singh and the NDP while British Columbia (model 2) appears only critical of the NDP.

Overall, these results are only partially consistent with hypotheses 1a, Sikh voters are more likely to evaluate Jagmeet Singh and the NDP positively, and 1d, Quebec voters are more likely to evaluate Jagmeet Singh and the NDP negatively.

4.2 Voting for the NDP

We now turn to consider a different dependent variable, vote choice. To assess it, we rely this time on logistic regressions. Since 1988, the NDP has consistently received more support from women. In general, the NDP has also been supported by younger voters. Before 2011, most NDP voters were also anglophones. However, both in 2011 and 2015, francophones, mainly from Quebec, began to vote for the NDP in large numbers (Bouchard, Reference Bouchard2020).

Looking at vote intentions for 2019, we investigate behaviors associated with desertion (a person who voted for the NDP in 2015 but does not intend to do so in 2019) or migration (a person who did not vote for the NDP in 2015 but intends to do so in 2019). We proceed this way to circumvent issues related to the study of leaders' images in a partisan context. Most importantly, it is argued that parties on the left of the political spectrum, such as the NDP, are more likely to select leaders associated with an ethnocultural minority, and that their partisans are less likely to penalize them for it. The literature offers more support for ethnicity-based discrimination in politics at the right of the spectrum (Street, Reference Street2014; Besco, Reference Besco2018). By considering migration as well as desertion behaviors, we only scrutinize the actions of individuals who could support this party, as they either voted for the NDP in the past or intended to do so in the future.

Tables 4 and 5 present the same sociodemographic controls as we previously used. To begin this analysis, Table 4 considers desertion from the NDP. Unsurprisingly, weak NDP partisanship has a statistically significant impact on desertion in all models. Living in Quebec has a significant, positive impact during the campaign (model 2), while the effect is positive and significant in both models in the case of British Columbia.

Lastly, considering migration to the NDP from another party, Table 5 shows the statistically significant influence of both strong and weak NDP partisanship in the two models. That table also shows that neither Sikhs nor Indian Canadians are significantly more likely to migrate to the NDP than other Canadians. These results shed doubts on hypotheses 2a. The effect is also not statistically significant in the case of Canadians of color, therefore disproving hypotheses 2b and 2c.

Overall, Tables 4 and 5 shed light on the second set of hypotheses. Considering 2a, we predicted that Sikh voters are more likely to migrate to the NDP in 2019, and less likely to desert the NDP in 2019, which we do not see in Tables 4 and 5. We notice the same things regarding Indian Canadians. Meanwhile, hypothesis 2d, Quebec voters are more likely to desert the NDP in 2019, and less likely to migrate to the NDP in 2019, appears more credible. During the campaign, the effect of living in Quebec on the propensity to leave the NDP is positive and statistically significant. Quebecers are also significantly less likely to migrate to the NDP in 2019. Interestingly, we only observe this in model 2 (in campaign data). We hypothesize that this could be explained by extended exposure to Singh, as the opinion Quebecers had of the NDP did not worsen during the campaign (Table 3). Given the low-information pre-electoral context, it is possible that some DC respondents were not aware of who Singh was or which party he was associated with. However, Table 2 shows that Quebecers were more critical of Singh from the beginning.

5. Discussion

This paper looks at the effects of leader ethnicity in politics by focusing on the case of Jagmeet Singh, the first federal party leader of color in Canada. Like many countries of the commonwealth, Canada has adopted a Westminster-style system of government, which poses unique challenges to aspiring party leaders of color, notably given the low number of parties represented at parliament. There have been few cases of leaders of color in such systems, which make this analysis of interest. Moreover, given the very stark divergences in reaction toward religious symbols in the country, it seems particularly relevant to consider the case of Jagmeet Singh.

Although Singh became the leader of the NDP in 2017, he was only elected as an MP in a by-election at the beginning of 2019 in the British Columbia riding of Burnaby-South. Later that year, he would run to become the country's Prime Minister. This article thus considers both early opinions Canadians had of Singh before the campaign as well as campaign dynamics. It is suspected in the literature that first impressions, in particular, are particularly important as heuristics in a low-information context (Banducci et al., Reference Banducci, Karp, Trasher and Rallings2008). While Singh benefited from the notoriety of being a federal party leader, it appears reasonable to assume that voters knew far more about him at the end of the campaign than they did before it started.

The first set of hypotheses considered in this paper centered around Canadians' evaluation of Singh and the NDP. An important body of literature claims that individuals associated with minority ethnic groups may be more likely to support a candidate of color, from work in social psychology on in-group favoritism (Carlston, Reference Carlston2013; Dovidio et al., Reference Dovidio, Hewstone, Glick and Esses2013; Fiske and Taylor, Reference Fiske and Taylor2017) to analysis in political science of the political behavior of people of color (Lublin, Reference Lublin1997; Collet, Reference Collet2005; Herron and Sekhon, Reference Herron and Sekhon2005; Barreto, Reference Barreto2007, Reference Barreto2010; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Heath, Sanders and Sobolewska2014; Zingher and Farrer, Reference Zingher and Farrer2016), including in Canada (Besco, Reference Besco2015; Bird et al., Reference Bird, Jackson, Michael McGregor, Moore and Stephenson2016; Bouchard, Reference Bouchard2020). Our analysis in this paper shows some evidence of affinity-based political behavior. In particular, we find that Sikh Canadians were more favorable toward Singh. However, contrary to what could have been expected (Besco, Reference Besco2015), we do not find evidence of a “rainbow coalition,” as Canadians of color were notably not more likely than other Canadians to evaluate Singh positively.

Hypotheses 1d and 2d consider a negative evaluation of Singh and political desertion. On the overarching topic of discrimination, the literature reports mixed evidence at best (Highton, Reference Highton2004; Street, Reference Street2014), and results obtained in Canada are similar (Tossutti and Najem, Reference Tossutti and Najem2002; Black and Erickson, Reference Black and Erickson2006; Black and Hicks, Reference Black and Hicks2006; Murakami, Reference Murakami2014). Partisanship has notably been identified as an important mitigator of such behaviors (Murakami, Reference Murakami2014; Street, Reference Street2014; Hood and Mckee, Reference Hood and Mckee2015).

Our results show important provincial variations when the reception of Jagmeet Singh's candidacy is considered while controlling for partisanship. As predicted, voters in Quebec appeared singularly skeptical of Singh. A province that had voted in “bulk” for the NDP in 2011,Footnote 20 leading to what was called the “orange wave,”Footnote 21 appeared far more reluctant to do so in 2019, even before the election began. Even though voters in the Prairies also appear fairly critical of the NDP, it must be added that these provinces have not experienced recent strong levels of support for the federal NDP. Quebecers were also, overall, less likely to attribute positive traits to Singh. We do not claim, however, that Quebecers are particularly intolerant toward diversity in Canada as we control for racial prejudice, meaning that at equivalent levels of prejudice, Quebecers are still more critical of Singh than Ontarians, our baseline. Other factors could also help explain the fate of the NDP in Quebec in 2019. The main one is the rise of the secessionist party BQ. While the NDP is a pan-Canadian federalist party, meaning that it is opposed to the secession of Quebec from Canada, the BQ only runs in Quebec and promotes the province's independence. The BQ got nearly wiped off the electoral map in Quebec in 2011, mainly by the NDP's “orange wave,” losing 43 of its 47 seats. The recovery began slowly in 2015 as the BQ gained eight seats. In 2019, with at its head a new leader who was also a notorious former provincial politician, the party won another 22 seats notably at the NDP's expense. However, despite these party dynamics, our results clearly show that Quebecers were particularly critical of Singh himself (Table 2) rather than of the NDP (Table 3).

Additionally, Besco (Reference Besco2018) underlines that conservative voters in Canada are more likely to rate less highly candidates of color than other partisans. In fact, it is argued that one of the main explanations of mixed evidence regarding the prevalence of discrimination is the tendency of candidates of color to run for left-wing political parties (Street, Reference Street2014; Hood and Mckee, Reference Hood and Mckee2015). While Singh represented a left-wing political party, and Conservative partisanship had a strong negative impact on both evaluations and voting intentions, controlling for partisanship did not render provincial effects insignificant. In other words, these divergences cannot simply be explained by partisan affiliations or strengthFootnote 22 either.

Overall, this work shows the influence of social distance on the evaluation of a party leader of color and of their party. In the case studied, the increase in personal support for Singh was seen only in the social groups closest to him and did not extend, for example, to Canadians of color. The issue of secularism could also have contributed to an increase in social distance between Quebecers and Singh. It does not appear surprising that the NDP lost all but a single seat in Quebec following the 2019 election. However, the main limit of this research is that we cannot claim that there is a causal link between Singh's appearance and the evaluation of voters or their vote intentions. While we underline, for example, differences in terms of political support and leader evaluations between Quebecers and Ontarians (the baseline), and that the issue of religious garments is particularly salient in Quebec, multiple factors likely contributed to these behaviors. Nonetheless, the notions of ethnicity and difference are important factors to take into consideration while interpreting our results.Footnote 23

Several lessons can be learned from these results. First, we show that the sociodemographic characteristics of non-prototypical leaders could matter to voters in Westminster-style systems. More importantly, the effect of a leader appears to differ depending on the social group each voter identifies with. Social distance with a leader, therefore, seems to have an impact on political attitudes and intended behaviors, as demonstrated by the example of Sikh Canadians whose opinion toward Singh appears different than other Canadians of color. Additionally, this paper points to the distinctive attitude of Quebecers toward Singh which cannot be explained solely through racial prejudice. In this case, a particular stance toward secularism could lead to these results.

Appendix

A.1. Composition of the “POC” variable

The “POC” variable was obtained through the following question of the Democracy Checkup:

Please select all that apply.

Aboriginal/ First Nations, British, Chinese, Dutch, English, French, French Canadian, German, Hispanic, Indian, Inuk/ Inuit, Irish, Italian, Métis, Polish, Québécois, Scottish, Ukrainian, Other 1 (please specify), Other 2 (please specify), Don't know/ Prefer not to answer.

The following answers were coded as “1” in the “POC” variable:

Aboriginal/First Nations, Chinese, Hispanic, Indian, Inuk/Inuit, and Métis.

Were also coded as “1” any iterations of the following answers given in the free text:

Abénaquis, Afghan, African, African American, Algerian, Arab, Asian, Assyrian, Bangladeshi, Barbadian, Black, Brazilian, Cambodian, Caribbean Islander, Congolese, Cree, Egyptian, Filipin-a, Ghanaian, Haitian, Hongkonger, Indian, Indonesian, Iranian, Jamaican, Japanese, Korean, Laotian, Latino-a, Lebanese, Moroccan, Middle Eastern, Visible minority, Nigerian, Pakistani, Palestinian, Persian, Puerto Rican, Punjabi, Rwandan, Sri Lankan, Tagalog, Taiwanese, Thai, Trinidadian, Turkish, Vietnamese, Yoruba, Eritrean, Guyanese, and Gambian.

A.2. Composition of the scales

A.2.1 Composition of the Jagmeet Singh traits scale (DC)

The evaluation scale contains four variables. For each of them, respondents were scored either 0 if they did not select Singh, or 1 if they did. Results range from 0 to 4 with a mean score of 1.27.

A.2.2 Composition of the racial prejudice scale (DC)

The prejudice scale contains seven variables. Respondents are scored from 0 (no racial prejudice) to 100 (racial prejudice) for each of them. The scale is additive and reaches 700. The mean score reaches 333.79.

• Question 1: Too many recent immigrants just don't want to fit into Canadian society.

Average score: 59.20

• Question 2: Immigrants take jobs away from other Canadians.

Average score: 38.29

• Question 3: We should look after Canadians born in this country first and others second.

Average score: 57.17

• Question 4: Do you think Canada should admit: more immigrants, fewer immigrants, or about the same number of immigrants as now?

Average score: 65.37

• Question 5 to 7: “How do you feel about the following groups?”

As we measure prejudice, the answers here were inverted (0 became 100 and 100 became 0).

Average score for racial minorities: 33.48

Average score for immigrants: 35.3

Average score for Muslims living in Canada: 44.64

A.2.3 Composition of the racial prejudice scale (CES)

The prejudice scale contains four variables. Respondents are scored from 0 (no racial prejudice) to 100 (racial prejudice) for each of them. The scale is additive and reaches 400. The mean score is 191.33.

• Question 1: How much should the federal government spend on immigrants and minorities?

Average score: 63.53

• Question 2: Do you think Canada should admit: (more immigrants, fewer immigrants, about the same number of immigrants as now)?

Average score: 62.25

• Questions 3 and 4: How do you feel about the following groups? Set the slider to any number from 0 to 100, where 0 means you really dislike the group and 100 means you really like the group.

As we measure prejudice, the answers here were inverted (0 became 100 and 100 became 0).

Average score for racial minorities: 33.32

Average score for immigrants: 36.93

A.3. Interaction between POC, the evaluation of Jagmeet Singh, and prejudice

See Table A.1.

Table A.1. Impact on the evaluation of the NDP of the interaction between POC, the evaluation of Jagmeet Singh, and prejudice

A.4. Interaction between the strength of partisanship and prejudice

See Table A.2.

Table A.2. Influence of prejudice and partisanship on desertion from the NDP

A.5. Impact of religiosity on the evaluation of Singh and NDP desertion

Religiosity was assessed using the following question: In your life, you would say religion is (very important, somewhat important, not very important, not important at all). Table A.3 shows that controlling for religiosity does not render the effect of Quebec statistically insignificant.

See Table A.3

Table A.3. Impact of religiosity on the evaluation of Singh and NDP desertion

A.6. Detailing the POC, Indian, and Sikh variables

See Table A.4.

Table A.4. Influence of voters' characteristics on the evaluation of Jagmeet Singh

A.7. Composition of the “deserter” and “migrant” variables

To create these variables, we began by identifying individuals who claimed they had voted in the previous elections (2015). Therefore, non-voters that year were excluded. Those who voted for the NDP in 2015 were coded as 1, and those who voted for another party were coded as 0.

We then identified all the respondents who claimed they would vote in 2019. Those who did not plan to vote were therefore excluded. Among the possible voters, those who claimed they would vote for the NDP were coded 1, and others were coded 0.

Migrants were identified as individuals coded as 0 in 2015 (voted, but not for the NDP) and 1 in 2019 (intended to vote for the NDP). They were coded as 1, while other voters were coded as 0.

Deserters were identified as individuals coded as 1 in 2015 (voted for the NDP) and 0 in 2019 (intended to vote, but not for the NDP). They were coded as 1 and other voters were coded as 0.

Consequently, in both cases, we only considered individuals who had voted in 2015 and planned to vote in 2019. Non-voters were excluded.