1 Introduction

The intention of this study is to elucidate the recent history of low vowels in English, specifically supraregional southern British English (henceforth SSBE), to show what key developments took place and how these affected the constellation of low vowels. The data for the study stem from a series of eighteenth-century prescriptivist works and from the recently available resource Eighteenth-Century English Phonology Database (2015; henceforth ECEP), which provides essential information on vowel realisations in specific phonetic contexts for a large number of authors (Beal & Sen Reference Beal, Sen, Vandelanotte, Davidse, Gentens and Kimps2014; Yáñez-Bouza, Beal, Sen & Wallis Reference Yáñez-Bouza, Beal, Sen and Wallis2018).

The point of departure for this study is SSBE in the late eighteenth century. Determining the sound system of SSBE in the second half of this century is a task for which one must have recourse to several sources. All of these are prescriptivist writers extolling a standard form of English as used in England at the time (and to be adopted in Scotland, Wales and Ireland, if not already the case).

Among these writers are three whose statements on vowel realisations have been subject to particular scrutiny for this study, Thomas Sheridan (1719–88), John Walker (1732–1807) and Robert Nares (1753–1829). The ECEP was consulted for comparative purposes, i.e. to determine what values for certain key vowels were given by other prescriptivists of the age, apart from the three just listed. In their works on pronunciation, all authors strongly advocate the adoption of what they regard as standard pronunciation. There is not full agreement between the authors on what constitutes the standard and much of the discussion in their works is concerned with justifying the pronunciations favoured by certain authors and not by others. In addition, authors like Sheridan and Walker are liberal in their censure of Scottish, Welsh and Irish pronunciations, their works often containing sections in which these varieties are strongly criticised; Walker's criticism also extends to local London English. This established a practice which continued well into the nineteenth century; such criticism of regional varieties in Britain and Ireland is found in Smart (Reference Smart1836), for instance.

For the discussion below use is made of the lexical sets devised by Wells and set out in his seminal work on accents of English (Wells Reference Wells1982). In the latter work the sets are used to compare present-day varieties worldwide and there is little discussion of historical developments. Nonetheless, given the widespread employment of Wells’ lexical sets in studies of English phonetics, they will also be adhered to here. There are four lexical sets which historically involve low vowels, trap, bath, palm and start (see table 1), with cloth a related and significant set in the present context (see discussion in section 3.3 below).

Table 1. Low vowels at the outset of the Late Modern Period (c. 1800)

Two facts concerning lexical sets must be borne in mind for the current study. The first is the realisation of lexical sets. Given that the trap vowel showed noticeable raising, the prescriptivists cite values for realisations which are within the range of the dress vowel today, e.g. ketch for catch. This does not mean that such words migrated to the dress set, i.e. merged with it,Footnote 1 but rather that all short front vowels were raised in SSBE in the late eighteenth and nineteenth century. The evidence of early audio recordings (Hickey Reference Hickey2017) suggests that the raised trap variants did not belong to the dress class as this in turn also showed raised realisations compared to today. With the later lowering of short front vowels words like catch were pronounced with a lowered trap vowel.

The second fact concerns the lexical incidence for sets.Footnote 2 The trap set comprised many more tokens in the late eighteenth century, given that many words which later migrated to the bath set were still in the trap set; indeed the bath set only came into existence with the first lengthenings of items in the trap set. The occurrence of long or short vowels within a lexical set could have been different compared to present-day SSBE as with the cloth lexical set, which contains words such as soft, sausage, with long vowels, which now have short vowels. A precise chronology of these developments is, of course, not possible, but the statements of eighteenth-century writers on pronunciation allow one to draw a partial picture, into which this study attempts to fill as much detail as is forthcoming from an analysis of the prescriptivist works examined.

This article begins with an overview of low vowels in early English and with a discussion of the lexical sets palm and start, leading to the outset of the Late Modern English period. Section 2 considers the use of prescriptivist works as evidence for sound change, specifically of the variation in the trap and bath lexical sets in the late eighteenth century. Section 3 considers low vowels from a generalised typological point of view, while section 4 looks at low vowel realisations outside Britain with a view to possibly determining the chronology of low vowel lengthening.

1.1 Low vowels in the early history of English

Throughout its history, the English language has consistently had vowels at the bottom of its vowel space. Such vowels were orthographically represented using Latin <a> and are clearly recognisable in Old English texts. However, the number and nature of low vowels has altered during the history of the language. For Old English (OE), scholars generally recognise two low front and two low back vowels, usually transcribed as /æ, æː/Footnote 3 and /ɑ, ɑː/ respectively (Lass Reference Lass1994: 64–5; Stenbrenden Reference Stenbrenden2016: 78–102). For Middle English (ME) – from the eleventh century onwards – it is assumed that there was a simplification of the vowel system with a single low central vowel existing, in both a short and a long form, i.e. /a, aː/ (Lass Reference Lass1976; Smith Reference Smith2003, Reference Smith, Kay and Smith2004). Movement on a vertical axis is, and has been, common in English. Already after OE the inherited long back vowel, as in OE ham /hɑːm/, began an upward movement along a back trajectory (in Southern English), leading to Late Modern English (LModE) /oː/, as in home /hoːm/ (Received Pronunciation (RP) /həʊm/). The present-day long low back vowel, as in RP pass /pɑːs/, is unconnected with the phonetically identical OE vowel and stems from a lengthening and retraction process, which is a central topic of this study (see section 3 below).

The upward movement of low vowels along a front trajectory is also attested for English, albeit at a much later stage of the language. The vowel that was written <æ> in Old English came to be represented as <a> after the ash grapheme <æ> fell into disuse in the Anglo-Norman period, i.e. after the mid eleventh century. The exact phonetic realisation of both OE and ME short low vowels is unknown so the working assumption is that this vowel was [a] in Middle English (Lass Reference Lass1976).

A length distinction for both front and back low vowels of OE (postulated for the West Saxon variety), i.e. /æ, æː/ and /ɑ, ɑː/, is assumed on the basis of orthography and later sound developments. The word æt, for example, yields ModE /iːt/. The front high vowel is known to be an outcome of the Great Vowel Shift (cf. meat ME /mɛːt/ > EModE /meːt/ > ModE /miːt/), so ME <æ> in this word must have stood for a long vowel as this was a precondition for the Great Vowel Shift. This in turn means that OE æt had a long low front vowel, i.e. /æː/ (the macron, sometimes written over this vowel, is a later editorial device). Similar arguments can be given for a length distinction among low back vowels in OE (Stenbrenden Reference Stenbrenden2016: 37–42).Footnote 4 The long vowels in this area were also subject to raising, this time on a back trajectory, e.g. ald, cald (Anglian) in which [ɑː] began to shift to [ɔː] (later to [oː] / [əʊ], e.g. ModE old, cold).

A consequence of pronunciation shifts in the history of English is an altered lexical incidence for low vowels. Apart from the raising of low vowels, which in effect depleted the number of such vowels, other changes actually increased the incidence of words showing low long vowels. Key here is the early ME process known as Open Syllable Lengthening (Minkova Reference Minkova1982). It led to words like make, take acquiring a long /aː/, i.e. /ma.kə/, /ta.kə/ > maː.kə/, /taː.kə/, whereas those with a short low vowel in a closed syllable, e.g. black, sack, retained this vowel unchanged through the ME period.Footnote 5 Those words which underwent vowel lengthening contributed to the numbers of those which satisfied the structural input to the subsequent Great Vowel Shift, which shifted ME /aː/ upwards on a front trajectory, and depleted the lexical incidence of long low vowels leaving the majority of low vowels short, the situation which still pertains in the north of England to this day (Hickey Reference Hickey and Hickey2015: 8–13).

Lass (Reference Lass, Hogg and Denison2006: 83–6) gives a sole example of long /aː/ from John Hart's An Englishe Orthographie (Reference Hart1569), which he regards as representative of sixteenth-century Southern English. This /aː/ was in the word name, which had a long vowel as a result of Open Syllable Lengthening. This vowel was probably already in the process of being raised through /æː/ to /ɛː/ and so is evidence of the reduced number of instances of /aː/ in Early Modern English.

1.2 The palm lexical set

Among the long vowels in Early Modern English were those in the word father Footnote 6 and in words where a vocalised back [ɫ] had triggered vowel lengthening by mora transfer from the lost liquid to the preceding vowel, e.g. half, calf, palm.Footnote 7 These vowels can be treated together in any consideration of their diachronic development within English in England. However, in his group of lexical sets, Wells divides these, regarding palm as a separate set from bath with half, calf and father belonging to the latter. His justification for palm and bath as separate sets has to do with the realisation of their vowels in General American English: ‘[t]he standard lexical set palm is defined as comprising those words whose citation form has the stressed vowel /ɑː/ in RP, /ɑ/ in GenAm, excluding cases where this vowel is followed by /r/ in GenAm’ (Wells Reference Wells1982: 142). For the current study the position in American English is not relevant. Conversely, there is evidence for treating Wells’ palm lexical set and words like calf and half together as all have a long vowel due to mora absorption on the vocalisation of the velarised [ɫ]. Such words are mostly transcribed with a long low vowel by the authors represented in the ECEP, such as Walker, although the latter consistently uses a short /æ/ to transcribe the vowel in words like path, grass, last, answer.

A further, small group of words with a long low vowel are the result of a loss of /x/ (<gh> in spelling), in some cases with a shift of the velar to a labio-dental fricative, e.g. laugh, draught. These words are consistently transcribed with long vowels by the prescriptivist writers, such as John Walker, who uses the ‘long Italian a’ as in far, father, i.e. [a:], for such words.

1.3 The start lexical set

The loss of non-prevocalic /r/ was underway during the second half of the eighteenth century when the prescriptivist writers were at their zenith. Attitudes to the loss of /r/ in this position varied, with writers like Walker recommending the pronunciation of this /r/ and others registering its loss. The majority of writers, whose pronunciations are listed in the ECEP, have a long vowel for the start lexical set, i.e. /aːr/, with /ær/ found mostly in words of two syllables, e.g. hearken, with authors like Stephen Jones (1763–1827). William Kenrick (1729/30–79), one of the older authors represented in the ECEP, has a long vowel in the start lexical set, i.e. /a:r/.

1.4 Situation at the outset of Late Modern English

Dobson (Reference Dobson1968: 545) postulates that Middle English /a/ was a front vowel, as it was distinguished only in length from /aː/. He regards both /a/ and /aː/ as front in articulation and distinguished from /ɑ/. Dobson emphatically rejects the interpretation of ME /a/ as [æ] and sees it as [a], a value which it has retained in northern dialects of English (Dobson Reference Dobson1968: 546; Beal Reference Beal, Kortmann and Upton2008).Footnote 8 On /aː/ Dobson (Reference Dobson1968: 594) states that ‘it must have been a front vowel, namely front [aː]’. There is a difficulty here concerning transcription. The transcription of Cardinal Vowel 4 is /a/ in Daniel Jones’ original vowel quadrangle (low front corner) with /ɑ/ representing Cardinal Vowel 5 (low back corner). The ash symbol is used for vowel values intermediary between Cardinal 4 and the next highest front vowel, the open mid vowel Cardinal Vowel 3 /ɛ/.Footnote 9

Dobson (Reference Dobson1968: 595) maintains, going on orthoepic evidence, that ME ā had been raised to [ɛː] by the sixteenth, into the seventeenth century. This fact and the lack of generalised lengthening in the bath lexical set meant that by the outset of the Late Modern English period, the beginning of the eighteenth century, low vowel space did not show many tokens of long vowels. The original long vowels of Old and Middle English had been raised on either a back or front trajectory due to a number of phonological processes. However, long low vowels did exist mostly for /a/ before /r/ and for /a/ before vocalised velarised [ɫ] and before former [x], even where this had been shifted to [f] and retained.

2 Prescriptivism and evidence for sound change

The rise of prescriptivism in the eighteenth century (Beal Reference Beal2004a: 89–104; Reference Beal, Lass and Dossena2004b), while triggering a development which is seen by linguists as regrettable, is in one way a boon for historical linguistics: when laying out various strictures in their works (Hickey Reference Hickey, van Ostade and van der Wurff2009), prescriptivists provide valuable information about the development of English phonology in the key eighteenth century, the bridge between the Early Modern and Modern English periods (Jones Reference Jones2005).

In terms of change, vowels 1 and 2 in table 1 are of particular interest. Vowel 1, trap, was subject to raising and vowel 2, bath, to lengthening in the eighteenth and into the nineteenth century with words from the former trap set migrating to the bath set. Hence prescriptivists’ statements on the low vowels of English, which are nowadays referred to using the lexical set shorthand of trap and bath (Wells Reference Wells1982: 129–30, 133–6), should be especially revealing. The cases of transcriptional disagreement among eighteenth-century authors are also interesting in that they point to instances of variation in a period of change. The preferences of some authors for certain realisations also give clues to what were incoming and what were outgoing variants.

The information for the current section has been gleaned from the ECEP along with an additional work, Nares (Reference Nares1784).Footnote 10 In these sources phonetic interpretations of late eighteenth-century realisations are given, thus allowing linguists to trace the probable development of low vowels in the past two hundred years or so, first in SSBE and, by extension, in different varieties of English.

2.1 The history of the trap–bath split

What is now known as the trap–bath split applies above all to SSBE. Wells (Reference Wells1982: 129) states that ‘[t]he standard lexical set trap is defined as comprising those words whose citation form in RP and GenAm has the stressed vowel /æ/’. On the bath vowel Wells (Reference Wells1982: 133–5) remarks that ‘[t]he standard lexical set bath is defined as comprising those words whose citation form contains the stressed vowel /æ/ in GenAm, but /ɑː/ in RP. That is to say, bath words belong phonetically with trap in GenAm, but with palm and start in RP.’ In addition, for SSBE, there is not just a length distinction between trap and bath but also a qualitative one given that bath has a retracted vowel compared to that in trap. For Wells, the bath class is historically characterised by a lengthening of a short low vowel before voiceless stops, either alone or in clusters, yielding a long vowel in words like staff, path, glass; after, grasp, cast, basket (see Cruttenden Reference Cruttenden2014: 123–6).Footnote 11 The dating of this lengthening is an issue which can only be properly approached by considering the situation in the late eighteenth century.

2.1.1 The outset in the late eighteenth century

The phonetic discussions found in eighteenth-century prescriptivist works are based on the one hand on orthographic vowels and on the other on their systems of vowel transcription using superscript numerals. The latter, if used consistently, can be interpreted phonetically and so the sound values being indicated can be ascertained with a high degree of certainty. Table 2 shows a typical system, that used by Thomas Sheridan (taken from his Rhetorical Grammar of the English Language, Reference Sheridan and Alston1781).Footnote 12 A similar system of classification was adopted by other prescriptivists after Sheridan, notably by Walker (Reference Walker1791), however with certain differences (contrast table 2 and table 3), the main one being the lack of a symbol in Sheridan's system for the long ‘Italian a’ as in father. Vowels may also be referred to using an adjective to qualify the letter. For instance, Robert Nares (Reference Nares1784) has three descriptions for his different kinds of A (table 4) which Walker also adheres to when offering in-text descriptions of a-sounds. This method is the least precise and the phonetic values intended are often difficult to determine (see section 2.1.4).

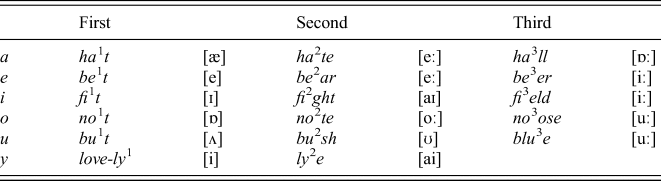

Table 2. Scheme of the Vowels (Sheridan Reference Sheridan and Alston1781: 151). IPA symbols are indicated in square brackets

Table 3. A Table of the Simple and Diphthongal Vowels referred to by the Figure over the Letters in this Dictionary (Walker Reference Walker1791: xvi)

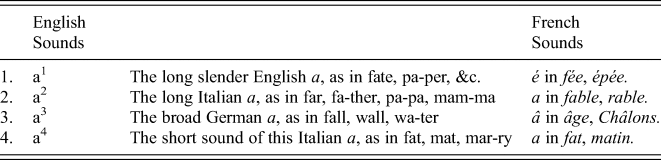

Table 4. Nares’ terminology for low vowels

Walker treated sounds on the basis of the letters used to represent them. This meant that he dealt with both low vowels and the long mid front vowel under the letter A (‘An Enquiry into the Alphabetical Pronunciation of the Letter A’, Walker Reference Walker1791: 7–13). He was aware of four possible vowel values for orthographic <a>: face, father, water and fat, which, going on his transcription system, can be rendered in IPA as [eː], [aː], [ɒː] and [æ] respectively. Walker furthermore claims that there are three pronunciations of the letter <a>: [eː]Footnote 13 in England, [aː] in Ireland and [ɒː] in Scotland, which he writes as Aye, Ah and Aw respectively (Walker Reference Walker1791: 8). In paragraph 78 of his section on A, Walker (Reference Walker1791: 10) deals with what he calls ‘The long sound of the middle or Italian a’, which he claims occurs in (i) monosyllables ending in r, e.g. car, far (ii) ‘before the liquids lm’ as in psalm, (iii) ‘sometimes before lf, and lve as calf, half, calve, halve, salve, &c’ and (iv) ‘before the sharp aspirated dental th in bath, path, lath, &c. and in the word father’.

In the last category of long a, (iv), Walker remarks that ‘this sound of the a was formerly more than at present found before the nasal liquid n, especially when succeeded by t Footnote 14 or c, as grant, dance, glance, lance, France, chance, prance, &c.’ This would imply that there was a shortening of the vowel in grant, chance, which is unexpected given that the trend at the time was for a lengthening of the low vowel in this position. But Walker confirms, without mentioning any social or regional group, a tendency towards shortening in the following paragraph:

79. The hissing consonant s was likewise a sign of this sound of the a [a long vowel, RH], whether doubled, as in glass, grass, &c or accompanied by t, as in last, fast, &c. but this pronunciation of a seems to have been for some years advancing to the short sound of this letter, as heard in hand, land, grand, &c. (Walker Reference Walker1791: 10)

This perceived shortening would seem to justify Walker's stigmatisation of a long vowel in words like after, answer, plant, mast, etc. (Reference Walker1791: 11). He continues to remark on former spellings of and as aund in words like maun for man, haund for hand which he sees as an older ‘Saxon’ sound and states that ‘since the u has vanished, the a has been gradually pronounced slenderer and shorter, till now almost every vestige of the ancient orthography seems lost; though the termination mand in command, demand, &c. formerly written commaund, demaund, still retains the long sound inviolably’ (Reference Walker1791: 11).

Walker also notes the length of the low vowel before /r/ in monosyllables, but its short articulation when it occurs in disyllables: mar, marry; tar, tarry; car, carry. He rightly notes that morphology wins out in this situation, though: when the disyllable results from adding a word-formational ending, e.g. adjectival -y, then the length of the monosyllable is retained as in star ~ starry.

The third sound in table 3 is that in a word like water which Walker calls the ‘broad German a’ (see also table 4). In present-day RP this is a fairly close mid back vowel, [ɔ˔ː]. However, this value is fairly recent as can be seen from audio recordings of RP speakers from the early twentieth century which show a more open vowel in the thought lexical set (Wells Reference Wells1982: 144–6), i.e. [ɔː].

83. The third long sound of a is that which we more immediately derive from our maternal language, the Saxon, but which at present we use less than any other: this is the a in fall, ball, gall . . .: we find a correspondent sound to this a in the diphthongs au and aw; as laud, law, saw, &c. (Walker Reference Walker1791: 11)

84. The long sound of the deep broad German a is produced by ll after it, as in all, wall, call; or indeed by one l, and any other consonant besides the mute labials p, b, f, and v, and the sharp and flat gutturals c and g; as salt, bald, false, &c. (Walker Reference Walker1791: 11)

Lastly, we can note that Walker is aware of the retraction of short a after w:

85. The w has a peculiar quality of broadening this letter, even when prepositive: this is always the effect, except when the vowel is closed by the sharp or flat guttural. (Walker Reference Walker1791: 11)

His labels ‘the sharp or flat guttural’ refer to /k/ and /g/ respectively, so he is excluding post-w retraction before these sounds, e.g. in quack and swag. In his discussion of this retraction Walker acknowledges variation; he writes: ‘thus quantity ought to be pronounced as if written kwontity, and quality should rhyme with jollity; instead of which we frequently hear the w robbed of its rights in its proxy; and quality so pronounced as to rhyme with legality’.

2.1.2 Variation in trap and bath in late eighteenth-century English

Walker remarks in his dictionary on changes occurring during his lifetime. The lengthening of vowels in the bath lexical set is one prominent example, the loss of rhoticity is another. Regarding the latter it is obvious that Walker favoured the pronunciation of /r/ in every position in which it occurred orthographically, given his principle of analogy whereby letters should always stand for sounds. However, he was sensitive to contemporary variation and ongoing change and comments at length on the issue of rhoticity:

In England, and particularly in London, the r in lard, bard, card, regard, &c. is pronounced so much in the throat as to be little more than the middle or Italian a, lengthened into laad, baad, caad, regaad; while in Ireland the r, in these words, is pronounced with so strong a jar of the tongue against the forepart of the palate, and accompanied with such an aspiration or strong breathing at the beginning of the letter, as to produce that harshness we call the Irish accent. But if this letter is too forcibly pronounced in Ireland, it is often too feebly sounded in England, and particularly in London, where it is sometimes entirely sunk; (Walker Reference Walker1791: 50)

He then recommends: ‘Thus Rome, river, rage, may have the r as forcible as in Ireland; but bar, bard, card, hard, &c. must have it nearly as soft as in London.’ Hence Walker had come to accept weak rhoticity but not the full deletion of non-prevocalic /r/. Comments like these betray Walker's ambivalent attitude to ongoing change, something which is also apparent in his treatment of low vowels.

A strategy to be seen in pronouncing dictionaries is to accept change for certain words, but not across the board. For instance, Walker accepts bath with a long vowel but not path, staff or glass, for instance. What is unclear is whether the lengthening did not exist in the latter items (and others not listed), i.e. whether vowel lengthening in the bath lexical set proceeded by a process of lexical diffusion, or whether approving of length in some individual words was a strategy of authors to partially accept change in progress during their lifetime. This issue is treated in detail in Trapateau (Reference Trapateau2020), who rejects the view that word frequency was instrumental in the spread of low vowel lengthening but who recognises the role of certain ‘lead words’, like draught or master, in this process. He supports the view of lexical diffusion, put forward by Phillips (Reference Phillips2006, Reference Phillips, Honeybone and Salmons2015), and offers a relative chronology of the spread of long low vowels through the lexicon of English.

2.1.3 Height variation with trap

Indications that the /æ/ vowel in the trap lexical set had a raised realisation, more like /ɛ/, go back at least to the eighteenth century. Walker remarks on the pronunciation of this vowel; under the heading Irregular and unaccented Sounds he notes:

89. There is a corrupt, but a received pronunciation of this letter in the words any, many, Thames, where the a sounds like short e, as if written enny, menny, Tems. (Walker Reference Walker1791: 12)Footnote 15

The earliest recordings of speakers of Received Pronunciation also point towards a general raised pronunciation of the trap vowel, at least compared to the realisations found in the later twentieth century (Henton Reference Henton1983; Docherty Reference Docherty and Kirkpatrick2010). It is not until the mid twentieth century that this raising of [æ] is reversed, yielding the present-day tendency to have a lowered vowel in the trap lexical set (Bauer Reference Bauer1994: 120–1; Upton Reference Upton, Kortmann and Upton2008).

2.1.4 Length and quality variation with bath

Mugglestone (Reference Mugglestone2003: 79) points out that Walker was especially conservative with regard to lengthening of /a/ before voiceless fricatives which he considered inaccurate and vulgar. Other writers, notably William Smith, Steven Jones and Robert Nares, all noted vowel lengthening in this position, citing the vowels in words like fast, ask, pass, staff as long.

Walker – in a second edition of his dictionary in 1797 – is highly critical of William Smith's recommendation of /aː/ (Smith Reference Smith1795) in the bath lexical set:Footnote 16

79. . . . and pronouncing the a in after, answer, basket, plant, mast, &c. as long as in half, calf, &c. borders very closely on vulgarity: it must be observed, however, that the a before n in monosyllables, and at the end of words, was anciently written with u after it, and so probably pronounced as broad as the German a. (Walker Reference Walker1797: 10–11)

Nonetheless, Walker was aware of this lengthening as an item of change. Here, as elsewhere, he is prepared to countenance some lexicalised instances embodying ongoing change. Thus he accepted low vowel lengthening in the word master (Walker Reference Walker1791: 8), but remarked repeatedly that this is an exception (see Beal Reference Beal, Eaton, Fischer, Koopman and van der Leek1985 on its occurrence with a long vowel in Northern English).

There are also contradictions within Walker's dictionary. For instance, in the comprehensive introduction he mentions that a long ‘Italian a’ can be found in the words bath, path, lath; however, under the entries for these words in the body of the dictionary he gives a short a (his ‘a4’).

Italian and German a in Walker. There is an issue of interpretation here which is of relevance to the later development of the bath vowel. Walker appears to use the term ‘Italian a’ and ‘German a’ to refer to two different sounds. His description of the ‘Italian a’ is as a long version of the short a in the trap set. Consider the following remarks which boost this interpretation:

80. . . . Thus when, by impatience, that grand corrupter of manners, as well as language, the no is cut out of the word cannot, and the two syllables reduced to one, we find the a reduced to the Italian or middle a, as cannot, can't; have not, han't; shall not, shan't, &c. (Walker Reference Walker1791: 11)

When these letters are followed by n and another consonant, they change to the second sound of a, heard in far, father, &c. Thus aunt, haunt, daunt, askaunce, askaunt, flaunt, haunt [sic!], gauntlet, jaunt, haunch, launch, craunch, jaundice, laundry, have the Italian sound the a in the last syllable of papa and mamma.Footnote 17

This would exclude Walker's ‘Italian a’ from anything like the retracted bath vowel of present-day RP. What is termed by Walker, and others, such as Nares, the ‘broad a’ or ‘broad German a’ (Walker) is another matter. Walker refers to the vowel as ‘[t]he long sound of the deep broad German a is produced by ll after it, as in all, wall, call’ (Reference Walker1791: 11). In IPA terms, this vowel would have been either [ɒː], or perhaps a somewhat higher [ɔː]; if the vowel was not rounded it would have been [ɑː] as in bath today. The statements by the later eighteenth-century prescriptivists are unfortunately not precise enough to determine the quality of the vowel conclusively but there are some indications of what was meant. For instance, when talking about the pronunciation of words such as want, was, what, Walker (Reference Walker1791: 11) notes that ‘[t]he w has a peculiar quality of broadening this letter’. Here he is clearly referring to the retraction (with later slight rounding) of /a/ [æ] after /w/ as in squad [skwɑd] (later [skwɒd]). For Walker (and Nares) the term ‘broad [German] a’ referred to a vowel in the low back area, perhaps with some rounding; this vowel does not occur in the bath lexical set which has the ‘Italian a’, either [æ] or [aː], depending on what Walker was prepared to recognise. Hence the vowel nomenclature used by Walker and Nares is similar; the main difference is in Walker's attitude to the use of a long ‘Italian a’ in the bath set. It is striking that Walker acknowledged the long vowel in the word bath but not necessarily in all words which nowadays comprise the bath lexical set.

2.1.5 Vowel quantity in Walker's dictionary entries

The discussion so far has been concerned with the statements regarding vowels found in the long introduction to Walker's dictionary. There he was able to discuss variation, and vent his displeasure at many pronunciations. However, in most of the entries in the body of the dictionary Walker commits himself to a single recommendation for pronunciation. With regard to the ongoing process of low vowel lengthening before voiceless fricatives, Walker is largely conservative, but does allow for a long vowel in bath. For those words which have their pronunciation due to Open Syllable Lengthening in Middle English, he recommends /eː/, e.g. paste, raven, etc. with a1 /eː/. For classical loanwords he sometimes offers two pronunciations: in the entry for drama, which contains a long discussion of variant pronunciations, neither of those given corresponds to the modern RP realisation ([drɑːmə]): dra4mˈma4 [dræmə], or dra1ˈma4 [dreːmə].

2.2 Robert Nares (Reference Nares1784) Elements of Orthoepy

It would seem that Walker favours somewhat conservative pronunciations across the board, not only for low vowels. The more progressive author Robert Nares, whose work Elements of Orthoepy (Reference Nares1784)Footnote 18 actually precedes Walker's dictionary by seven years, offers realisations which are closer to modern RP, as Beal (Reference Beal2004a: 138–42) demonstrates quite clearly.

Nares (Reference Nares1784: 3) in the section ‘Of the Letter A’ notes that face, make, age have /eː/ and confirms that ‘the short sound of a occurs in bad, back, &c and seems to be the same in other languages as with us’. The ‘other languages’ which Nares uses for comparison are French and Italian, so he would appear to be maintaining that the trap vowel was realised in the region of /a/. In his ‘A like E short’ Nares (Reference Nares1784: 11) notes that a short e sound [ɛ] is found in words like catch, gather, many, thank, and states that manifold also shows this [ɛ]. Of these words in Modern English (ModE) only any and many Footnote 19 have a lexicalised pronunciation with [ɛ], although the word ketch, for a double-masted sailing boat, apparently derives from the raised vowel pronunciation of catch.

Under ‘Irregular Sounds of A’ Nares discusses ‘Open A’ and confirms that a variety of words have a long vowel, similar to that in French and Italian, such as bravado or cantata. His list, which he claims is exhaustive, contains words belonging to both the bath and the palm lexical sets, e.g. bath, staff, ask, mast, dance, glance, plant, remand, slander; balm, psalm, calf, half. The list also contains the word father and Greek borrowings pronounced with long /aː/ such as drama (Nares Reference Nares1784: 4–6). Some words appear in the list with long /aː/ which today have a short low vowel, such as plastic and elastic, though for some speakers such words may have a long vowel in analogy to others like plaster, master, etc. Other words are listed as having a long vowel which today vary between long and short, e.g. transit. There are also words in his list which have a different stress pattern and hence a different pronunciation nowadays, e.g. gallant (Nares: /gəˈlaːnt/, ModE: /ˈgalənt/), complaisant (Nares: /kəmpleːˈsaːnt/, ModE: /kəmˈpleɪsənt/).

2.3 Relative chronology of low vowel changes

When using the statements of prescriptivists to construct a relative chronology of low vowel changes in the late eighteenth century some caveats must be borne in mind. There are degrees of prescriptivism in the works on pronunciation. Sheridan and Walker are especially censorious and generally voice their displeasure at ongoing change. Hence it is advisable to take an author like Nares, whose stance vis-à-vis change is neutral, to relativise the statements in the more comprehensive works of the first two authors. Another caveat concerns the interpretation of the vowel descriptions offered by authors. It is not possible to determine whether the long low vowels being described were retracted, as in present-day RP, nor is it possible to determine the degree of rounding with the vowel in what is now termed the thought lexical set. These are issues which concern quality. Eighteenth-century authors are easier to interpret when they are speaking of vowel quantity. Drawing together the statements by these authors and generalising over these one can venture a relative chronology for the quantitative changes which low vowels underwent. The earliest changes are those which involve /a/ followed by a liquid, first the lengthening on the loss of syllable-coda /l/ (1 and 2 in table 6), then the lengthening of /a/ before /r/ (3 in table 6). Both changes had been completed before the mid eighteenth century as all authors confirm long vowels in the words with this phonetic structure. The template /_and/ in polysyllables (4 in table 6) would also seem to have contained a long vowel before the prescriptivists began writing as all transcribe words matching this with a long vowel. In fact there are spellings in <au> which indicate that type 4 in table 6 was always a long vowel and maybe retracted as an equivalent of the sequence in French loanwords before nasals. This lengthening of the vowel indicated by <aun(d)> was also found in native words such as maund (man), haund (hand), something which is recorded by Walker (Reference Walker1791: 11); see the comments in section 2.1.1 above.

Table 5. Walker's recommendations for individual words

Table 6. Probable relative chronology of low vowel lengthening according to late eighteenth-century prescriptivists

Notes. (i) the first two types above involve the loss of syllable-coda velarised [ɫ] with mora compensation through vowel lengthening; (ii) the fourth type only applies to words of more than one syllable.

3 The quality and quantity of low vowels

In neither Walker nor Nares is there any conclusive evidence for the retraction of long /aː/ to /ɑː/ and this sound is not indicated in any of the exhaustive transcriptions given in the ECEP.Footnote 20 If this existed in the later eighteenth century one would expect that either one or the other or both authors would comment on this, if only to condemn it as a vulgarity. This implies that the short and long vowels of this period were /a/ [æ] and /aː/ [aː], the fronted realisation of /a/ being suggested by the fact that authors comment on the raised realisation of some words of the trap class, such as catch, gather, thank, etc.

The examination of low vowels in eighteenth-century prescriptive works can be supplemented by typological considerations of vowel systems. For those languages with a length distinction among low vowels, the long variant is either further back than the short one or it shows same place of articulation. A look at a selection of different low vowel systems supports this assumption (see table 7).

Table 7. Possible front–back configurations for short and long low vowels

The simplest configuration is that of Standard German where long and short vowels are distinguished solely by length, both being central in articulation. The Bavarian German pattern is also one in which length is the only distinguishing feature, but here both vowels are low back. The greatest articulatory distance is found in conservative RP where the short vowel is still fairly far forward and the long one is in the low back region. Due to the gradual lowering and centralisation of the trap vowel during the twentieth century, the vowels have come closer and now belong to a model (SSBE) shared by other languages such as Swedish.

The shift in articulation for the trap vowelFootnote 21 has been recognised by authors on ModE phonetics: Cruttenden (Reference Cruttenden2014: 119) uses the phonemic transcription /a/ for the trap vowel. Upton (Reference Upton, Kortmann and Upton2008: 242–3) discusses the shift from [æ] to [a] in ‘modern RP’, the former now being characteristic of ‘trad-RP’ (traditional Received Pronunciation). He also mentions that the former realisation as a low mid front vowel is the subject of comment by speakers, i.e. there is general awareness of the conservative and somewhat snobbish connotation of an [ɛ ~ æ˔] pronunciation.Footnote 22

The retraction of the bath vowel, typical of SSBE, is not shared by all varieties of English which have unconditional long vowels. In colloquial Dublin English (see type 4 in table 7) the bath vowel is low front and distinguished from the trap vowel only by length. In table 7, type 7 is typologically unusual in that the short vowel is further back in articulation than the equivalent long vowel, a situation also found in Hungarian (Benkő & Imre Reference Benkő and Imre1972).

The generalisation from the above considerations is that the retraction of the bath vowel to present-day [ɑː] is not in any way typologically unusual. Indeed for all varieties of English it holds that the long low vowel is never further forward in place of articulation than the equivalent short vowel.

3.1 Further phonetic considerations

The discussion above was concerned with place of articulation for long and short vowels. The phonetic environment of vowels also determines their realisations as long or short. Here quite a complicated picture emerges for a number of reasons, chiefly to do with the number of syllables in those words in which a low vowel occurs and the value for [voice] of the consonant immediately following it. While the alternation of vowels in word pairs like divine : divinity is now phonological in English, the phonetic preference for long vowels in monosyllables and the converse for polysyllabic words is still active. In addition, vowels before voiced consonants (see 3 in table 8) are also phonetically longer that those before the corresponding voiceless consonants (see 2 in table 8).

Table 8. Favouring environments for vowel length with phonologically short low vowels

Lengthening of short vowels is only possible with stressed syllables. This excludes lengthening is cases like appearance, entrance. Morphologically related forms may show a switch from long to short vowel with a shift in stress as with command : commandant. The lengthening of /a/ before a voiced obstruent in monosyllables is phonetically obvious and when discussing this lengthening Cruttenden (Reference Cruttenden2014: 120) mentions that the vowels in badge and barge, for instance, have only a slight difference in length.

3.2 The phonotactics of the trap–bath pair

Certain generalisations can be made about what low vowels in present-day SSBE belong to the trap or the bath lexical sets. In the following an attempt at a taxonomy of low vowels is undertaken. The following statements are generalisations and there are many lexicalised exceptions to vowel length in certain phonotactic environments.

In general, only /a/ occurs in monosyllables before codas consisting of a single stop, or nasal.

(1) /a/ cap, tap; cab, slab; pat, cat; mad, sad; back, tack, bag, sag

/a/ ham, lamp, ban, pan; hang, pang

Before liquids the situation is more complex. There are instances of short /a/ before a single liquid or a cluster of liquid and voiceless obstruent, e.g. shall, scalp (but scald with a long vowel). Long vowels before liquids can belong to either the bath or the thought lexical set (Wells Reference Wells1982: 146); cf. almond /ɑːmənd/ and alter /ɔːltə/ in SSBE.

The vowel before /m/ in words of more than one syllable can be long: (melo)drama, panorama, pyjamas (mostly foreign words, here Greek and Urdu); also in sample /sɑːmpəl/, but not in revamp /riːvamp/.

Before voiceless fricatives (this includes foreign words with a low vowel before /v/ as in lava /lɑːvə/) a long vowel is generally found.Footnote 23

(2) /ɑː/__f, θ, s staff, path, grass

Before /n/ followed by a voiceless obstruent in monosyllables.Footnote 24

(3) /ɑː/__ns, nt, nʧ dance,Footnote 25grant, branch

Before /nd/ usage varies: grand, bland, sand, mandate all have short [a], but command, remand, demand have a long vowel.

Before /st/, in both mono- and disyllables, a long vowel generally occurs, with some exceptions like plastic /plastɪk/ (analogously as /plɑːstɪk/).

(4) /ɑː/__st master, plaster; cast, past

Before a cluster consisting of a former /l/ and a further consonant a long vowel occurs. Some words, of considerable vintage, which have alC are realised with the thought vowel; cf. talk, walk with /ɔː/ in SSBE.

(5) /ɑː/__lm, lf, lv calm, calf, halve Footnote 26

The upshot of the above considerations is that there is considerable fluctuation in phonotactics for the tokens in the bath lexical set. The lengthening was chronologically staggered (see section 2.3 above) and the outcome still involves many lexicalised pronunciations for speakers today.

4 Length variation in English

The lengthening of low vowels before voiceless fricatives, discussed in the previous section, would appear to have originally extended to the low back vowel /ɒ/, in what Wells calls the cloth lexical set (Reference Wells1982: 136–7), but for the lengthening to have been later abandoned in SSBE (see the discussion of this issue in Beal & Condorelli Reference Beal and Condorelli2014). For the cloth lexical set the material in the ECEP presents a mixed picture. For example, the authors Walker, Sheridan and Kenrick all have a short vowel for a variety of words from the set. But there would appear to have been variation here: Stephen Jones in his 1797 edition of Sheridan Improved has [ɒ] but has [ɔː] in the Reference Jones1798 edition, just one year later.

Some authors would seem to suggest that the cloth set had a long vowel in the late eighteenth century. Robert Nares has a section ‘Of the improper Sounds of the Vowel O’ in which he states the following:

O sometimes has a sound resembling that of AU, or the broad A: this chiefly happens before the letters f, ʃp, ʃs, ft or th. Ex. off, doff, scoff, offer, and all words that begin with off-; aloft, coffee, proffer, profit, prophet, often, ʃoft, loʃt – hoʃpital, proʃpect, proʃper, – loʃs, croʃs, toʃs, – froʃt, loʃt, toʃt, coʃt, – broth, cloth, froth, moth: though this sound is very like that of the short o, it is yet distinguishable from it: moʃs and droʃs are not the same as croʃs and loʃs. (Nares Reference Nares1784: 30–1)

The last part of the above quotation is intriguing as it maintains that short o and the sound ‘resembling that of AU, or the broad A’ were not phonetically identical. Given the words which Nares transcribes with the ‘broad A’, the implication is that the vowel in the words of the above quotation were long. For this sound Nares gives examples such as ‘author, law, &c.’ to illustrate it (Reference Nares1784: 7). One would expect /ɒː/ or /ɔː/ in words such as author, law in the late eighteenth-century in southern England. But for the present study it is sufficient to note that Nares does not by any means imply that ‘The Broad A’ was pronounced similarly to long a or short o. As with Nares’ list of long a-words, he has some in ‘The Broad A’ set which are short in present-day English, such as want (Nares: /wɒːnt/, ModE: /wɒnt/), squadron (Nares: /skwɒːdrən/, ModE: /skwɒdrən/).Footnote 27

The only author in the ECEP who nearly always had a long vowel – [ɒː, ɔː]Footnote 28 – in all the words of the cloth lexical set examined (across, broth, cloth, froth, cough, cost, cross, croft, frost, gone, loft, loss, lost, off, often, soft, soften, toss, trough, etc.) was the little-known John Burn in his A Pronouncing Dictionary of the English Language, with Stephen Jones in the second edition of Sheridan Improved (Reference Jones1798) not far behind. Walker prefers a short vowel throughout the cloth lexical set and has soft with o4 [ɒ], but he added the comment ‘[w]hen this word is accompanied by emotion, it is sometimes lengthened into sawft, as Mr. Sheridan has marked it: but in other cases such a pronunciation borders on vulgarity’ (Walker Reference Walker1791: 546).

Present-day varieties of English do not show a long vowel in words such as frost, lost, across (though the actual word cloth does vary, Beal & Condorelli Reference Beal and Condorelli2014). Wells (Reference Wells1982: 136) maintains that a long vowel in such words is indicative of conservative RP and that General American also has the long vowel for cloth. But he confirms that the long vowel here was largely the result of pre-fricative lengthening (which he posits for the seventeenth century). This fact is important because it explains the situation in other, more conservative varieties, such as Dublin English where long vowels are found in words like off [ɒːf], cloth [klɒːt̪] as well as all words with a final /-st/, e.g. frost [frɒːst], lost [lɒːst], cost [kɒːst] (Hickey Reference Hickey2005: 28 + 32). The long vowel in the entire cloth set in Dublin is an example of persistent ‘colonial lag’: educated speakers in Dublin picked up the long vowels of the cloth set in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and have maintained them ever since.

The main insight of these considerations is that the pre-late eighteenth-century cloth lexical set contained more items with long vowels. The lexical incidence of long vowels in this set decreased in time. This in turn meant that the low back area of vowel space had fewer instances of long vowels, fewer tokens of this type, seen across the entire lexis of English. This could possibly have had an attraction effect on the retraction of long vowels from the bath lexical set during the nineteenth century.

4.1 Possible motivation for vowel lengthening

It is legitimate to ask why the variation in low vowels, well documented since the eighteenth century, should have occurred in the first place. In particular the lengthening of vowels is a phenomenon which is not determined by simple phonetic considerations, such as the earlier lengthening before voiced consonants, e.g. bath : bathe; grass : graze, or the very early voicing of intervocalic consonants, reflexes of which can be seen in word pairs like teeth : teethe; knife : knives; wife : wives (Lass Reference Lass1994: 71-3). The irregularity produced by vowel lengthening in the past two centuries would point to a mixture of phonotactic considerations and sociolinguistic factors providing the motivation for lengthening. For instance, before voiceless fricatives is not a phonetically natural environment for lengthening. The pre-nasal environment is different as liquids and nasals show a similar sonority value to vowels and hence can leak backwards into vowels inducing length, as is amply attested in the history of English; for liquids, see examples discussed above and for nasals, consider the late Old English vowel lengthening before /nd/ as is blind /blɪnd/ > /bliːnd/. It is not possible to reconstruct any sociolinguistic motivation for the Late Modern lengthening of /a/, but its progress in SSBE by lexical diffusion (Phillips Reference Phillips2006, Reference Phillips, Honeybone and Salmons2015),Footnote 29 rather than by an across-the-board Neogrammarian-style lengthening, would point to a mixture of internal and external motivation for the lengthening. This would also help to account for that fact that the lengthening before voiceless fricatives seemed to have occurred last (see discussion in section 2 above).

A factor favouring the lengthening and, in particular, the later retraction of the items in the bath lexical set might have been the reduction of tokens of long vowels in the cloth lexical set. However, it is not possible to demonstrate that space vacated in the phonological envelope of a language can trigger a movement, or even partial movement, into that space, here the low back region for long vowels.

5 Conclusion

The late eighteenth century was a period in which the low vowel system of English showed considerable variation. The sources, which can be consulted to describe and analyse this variation, are prescriptivist works designed to delineate a standard form of the language which was recommended to educated speakers across Britain and Ireland.

The linguistic analysis of this material involves certain issues which need to be considered when trying to reach conclusions about the English sound system of the time. One issue, which arises immediately, is the attitude of authors to gradual, non-binary change. An example of this is the loss of rhoticity. Here there is a clash between principles which authors have, such as analogy on the one hand, which demanded a maximum correspondence between spelling and pronunciation, and advancing change on the other. For example, Walker tried to keep to analogy while allowing low rhoticity for non-prevocalic /r/.Footnote 30

A further issue is whether the descriptions which authors offered actually reflect variation and change in later eighteenth-century English (Pouillon Reference Pouillon, Pillière, Andrieu, Kerfelec and Lewis2018). This is a methodological question for modern analysts who strive to draw as accurate a picture as possible of pronunciation at this time and perhaps glean some sociolinguistic information from incidental comments by authors. Here the material contained in the ECEP is particularly useful as it reflects the spectrum of feature representations in published works for the second half of the eighteenth century. The data of this resource also throw light on the changes which must have taken place between the late eighteenth century and the early twentieth century, when the first audio recordings of RP speakers became available (Hickey Reference Hickey2017), and later on in that century (Wells Reference Wells1982; Henton Reference Henton1983; Upton Reference Upton, Kortmann and Upton2008, Reference Upton and Hickey2012).

Finally, one can stress that the lexical incidence of short and long low vowels has changed since the late eighteenth century. The statements by prescriptivist authors are not always identical or in themselves unambiguous but they do serve to shed light on the state of flux characteristic of the system of low vowels in late eighteenth-century English.