Introduction

Haemangiomata are found in 4–10 per cent of infants and have natural phases of proliferation and involution.Reference Chang, Haggstrom and Drolet1 Subglottic haemangioma is a potentially life-threatening condition for which various treatment modalities are available. It typically presents within the first few weeks or months of life,Reference Wiatrak, Reilly, Seid, Pransky and Castillo2 usually with biphasic stridor and a normal cry.Reference McGill, Wetmore, Muntz and McGill3 The male to female ratio has been reported as 1:2.Reference Brodsky, Yoshpen and Ruben4, Reference Sie, McGill and Healy5 The diagnosis is based on the clinical history and the laryngoscopic findings. The classical appearance at laryngoscopy is an asymmetrical, smooth, submucosal, compressible, pink or bluish, subglottic mass (Figure 1). The endoscopic findings are diagnostic and biopsy is not necessary.

Fig. 1 Endoscopic view showing a unilateral, smooth swelling in the subglottis, the classical appearance of a subglottic haemangioma.

The treatment options for large subglottic haemangiomata include steroids (systemic or intralesional), laser ablation, open excision, tracheostomy and, more recently, propranolol.Reference Wiatrak, Reilly, Seid, Pransky and Castillo2, Reference Bajaj, Hartley, Albert and Bailey6 These lesions almost always eventually involute spontaneously; however, the time course for involution is unpredictable, and a tracheostomy may be required for several years.Reference Brodsky, Yoshpen and Ruben4, Reference Pierce7 Steroids have been used as the mainstay of medical treatment for many years, but are associated with side effects from prolonged use.Reference George, Sharma, Jacobson, Simon and Nopper8 Propranolol has been used more recently as a medical treatment for infantile haemangiomata,Reference Buckmiller, Munson, Dyamenahalli, Dai and Richter9 including subglottic haemangiomata.Reference Messner, Perkins, Messner and Chang10

This article aims to present the guidelines used at Great Ormond Street Hospital by ENT surgeons administering propranolol for treatment of infantile isolated subglottic haemangiomata.

Patients and methods

The use of propranolol for the treatment of complicated haemangiomata has been approved by the Great Ormond Street Hospital Drugs and Therapeutics Committee.

Propranolol (administered orally) has been used in the paediatric ENT department at Great Ormond Street Hospital, London, to treat eight cases of subglottic haemangioma (H. Ismail-Koch, unpublished data). Propranolol has also been used in the dermatology department to treat haemangiomata elsewhere on the body (more than 100 cases), using this same treatment protocol.

The diagnosis of subglottic haemangioma is confirmed by laryngotracheobronchoscopy, and photographs are taken for documentation and to assess treatment response. Propranolol treatment may require the support of a cardiologist if the child has any cardiac history or if there are any concerns on the electrocardiogram or echocardiogram.

The child's parents or carers need to be made aware of the potential side effects of propranolol. These include hypotension, bradycardia, bronchospasm, weakness and fatigue, sleep disturbance and nightmares, heart failure, cardiac conduction disorder, hypoglycaemia, and peripheral vasoconstriction. Propranolol should not be given with salbutamol or any other selective β2 agonist. If bronchodilation is required, ipratropium bromide should be used.

Results

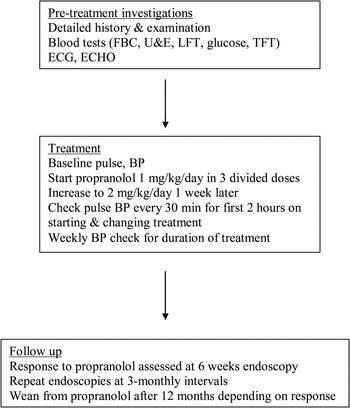

The Great Ormond Street Hospital guidelines for propranolol treatment for subglottic haemangioma (Figure 2) are divided into pre-treatment investigation, treatment and follow up.

Fig. 2 Flow chart for propranolol treatment for infantile subglottic haemangioma. FBC = full blood cell count; U&E = urea and electrolyte analysis; LFT = liver function tests; TFT = thyroid function tests; ECG = electrocardiography; ECHO = echocardiography; BP = blood pressure

Pre-treatment investigation

Prior to treatment, it is essential to take a detailed history and perform a thorough clinical examination, specifically including inspection of the whole body for haemangiomata, as well as cardiovascular and respiratory assessment. Pre-treatment blood tests should include a full blood count, urea and electrolytes (including creatinine), liver function, blood glucose and thyroid function tests. Urine examination for glucose is also done at this stage. Electrocardiography and echocardiography are mandatory before starting treatment.

Treatment

The child's baseline pulse and blood pressure should be recorded prior to treatment. Propranolol is started at 1 mg/kg/day divided into three doses. This dose is increased to 2 mg/kg/day one week after commencing treatment. The dose needs to be adjusted to take account of the child's weight gain over the following months. When starting propranolol and when increasing the dose, pulse rate and blood pressure must be checked every half hour; initially, this was done for four hours, but following an audit study the duration of monitoring was reduced to two hours. For the first two weeks after commencing treatment, the blood pressure needs to be checked twice a week, and thereafter weekly for the duration of treatment.

Follow up

The response of the subglottic haemangioma to propranolol is assessed on serial endoscopic examinations. The first laryngotracheobronchoscopy is performed six weeks after commencement of treatment to assess whether the haemangioma has responded. Follow-up endoscopies are performed at three-monthly intervals. Propranolol treatment usually needs to be continued for 12 months. After this, the child is weaned off propranolol, subject to their haemangioma's endoscopic response and their symptoms. The propranolol should be stopped by reducing the dosage over four weeks, by first halving the dose and then halving again after two weeks.

Using these treatment guidelines, eight patients with subglottic haemangioma have been treated and are still being monitored at our centre.

Discussion

Haemangiomata which present in inconspicuous sites can be left untreated and allowed to follow their natural course. Haemangiomata can cause problems if they undergo massive growth, ulcerate, impact on normal function or cause disfigurement. Haemangiomata on the face, ear, orbit and airway require prompt treatment to achieve good functional and cosmetic outcomes.Reference Haggstrom, Drolet and Baselga11

• Subglottic haemangioma is potentially life-threatening

• Treatment options include steroids, laser ablation, open excision or tracheostomy

• Propranolol is a new medical treatment for infantile haemangioma, including subglottic haemangioma

• The Great Ormond Street Hospital guidelines for this treatment are presented

All the treatment options for haemangiomata have limited therapeutic benefit and are subject to side effects and risks. Steroids, when used long term, induce Cushing syndrome, growth retardation, hirsutism, arterial hypertension, cardiomyopathy and immunosuppression.Reference George, Sharma, Jacobson, Simon and Nopper8 Tracheostomy in infants has significant mortality and morbidity.Reference Corbett, Mann, Mitra, Jesudason, Losty and Clarke12 Steroid injections plus intubation result in a prolonged stay in the intensive care unit. Laser ablation can lead to scarring and acquired stenosis.Reference Cotton and Tewfik13 Open surgical excision has its own associated risks.

Propranolol is a nonselective β-blocker used to treat infants with cardiac and pulmonary conditions. Leaute-Labreze et al. Reference Leaute-Labreze, Dumas de la Roque, Hubiche, Boralevi, Thambo and Taieb14 were the first to report rapid regression of haemangiomata in infants treated with propranolol. This finding has been corroborated by other authors who have used propranolol to treat subglottic haemangiomata.Reference Buckmiller, Dyamenahalli and Richter15–Reference Goswamy, Rothera and Bruce19 However, others have reported the failure of such treatment.Reference Goswamy, Rothera and Bruce19

It is not clearly established how propranolol causes haemangioma regression. Theories include vasoconstriction, down-regulation of growth factors, and cellular apoptosis.Reference Leaute-Labreze, Dumas de la Roque, Hubiche, Boralevi, Thambo and Taieb14, Reference Buckmiller, Dyamenahalli and Richter15

The reported side effects of propranolol treatment for haemangiomata tend to be minor. The more serious side effects are hypotension, bradycardia and hypoglycaemia, although these are usually seen in neonates in the first week of life and are less common in otherwise healthy infants.Reference Siegfried, Keenan and Al-Jureidini20

Propranolol treatment for haemangiomata should be carried out at specialist paediatric ENT centres only.

On reviewing the literature, we found no standardised guidelines for ENT surgeons using propranolol to treat subglottic haemangiomata. This article attempts to standardise and share the practice used in our paediatric tertiary referral centre.

Conclusion

Propranolol is a valuable treatment option for subglottic haemangioma. However, it should be borne in mind that there are concerns about the safety of propranolol and its potential side effects. Recent reports of dramatic responses to oral propranolol in children with acute airway obstruction due to subglottic haemangioma have lead to increasing use. We advocate a cautious approach, and have developed guidelines (including pre-treatment investigation and monitoring) to improve the safety of this treatment. Propranolol may in the future prove to be the best medical treatment for subglottic haemangiomata; however, at present it is considered to be still under evaluation.