Introduction

The sternocleidomastoid regional pedicled flap can be used as a myocutaneous, myofascial, myoperiosteal or osteomuscular flap.Reference Kierner, Zelenka and Gstoettner1,Reference Alvi and Stegnjajic2 The first sternocleidomastoid flap operation was reported in 1908. Surgical outcomes have been variable, largely a result of the variable blood supply to the muscle.Reference Kierner, Zelenka and Gstoettner1,Reference Ellabban3–Reference Kierner, Aigner, Zelenka, Riedl and Burian5 The main advantages are that it requires a shorter operating time compared to free flaps,Reference Laccourreye, Ménard, Behm, Garcia, Cauchois and Holsinger6 it has reduced muscle bulk, it is associated with reduced morbidity, and it is a convenient, versatile and hairless tissue.Reference Marx and Mcdonald4,Reference Noland, Ingraham and Lee7

Free flaps are increasingly used, as a result of advances in microvascular surgery. However, they are unsuitable when prolonged general anaesthetic cannot be tolerated or when no microvascular team is available.Reference Chen and Chang8,Reference Kumar, Gaud, Shukla and Pandey9 It also exposes an additional donor site to the risk of post-operative complications.Reference Chen and Chang8

Regional pedicled flaps avoid the need for microvascular anastomosis. The pectoralis major is a commonly used reconstructive flap, but often requires incisions outside of the primary operating field.Reference Tanaka, Yamaguchi, Ogi and Kohama10,Reference Liu, Chan and Wei11 It can be too voluminous for some reconstructions, and there can be excessive adipose tissue, especially in females.Reference Chen and Chang8,Reference Jena, Patnayak, Sharan, Reddy, Manilal and Rao12 Therefore, a sternocleidomastoid flap may be preferable for some patients.

There is great variety in usage of the sternocleidomastoid flap in the literature, and there have been many new reports since the most recent general review in 2001.Reference Kierner, Zelenka and Gstoettner1 As the use of free flaps is not without flaws, and a pectoralis major flap is not always an option,Reference Chen and Chang8 a reliable alternative for reconstruction needs to be explored. Use of the sternocleidomastoid reconstructive flap should therefore be reviewed, taking into account the literature from the past 15 years.

Methods

A literature search of the Medline and Web of Science databases was conducted to identify all articles, published from 1946 to 2016, that reported the use of sternocleidomastoid flaps. The keywords used were as follows: ‘sterno*mastoid’, ‘flap’, ‘limitation*’, ‘blood supply’, ‘vascula*’, ‘vessel*’, ‘repair’ and ‘reconstruct*’ (where the asterisk represented a wildcard symbol). The search was conducted in March 2016 and updated in August 2018. Exclusion criteria included case series with a small number of flaps used (less than 12) and studies that were not performed on humans.

The articles were split into case series, anatomical or radiological studies, and surgical methodology studies. Articles were then sorted by date to ensure the latest surgical techniques were well represented in the literature review.

The analysis of success and complication rates only included studies published from 1980 onwards. Complications were split into five categories based on the complications reported in the literature, and rates were analysed for each study. The trend in success rates was analysed by date of the study.

Arterial supply of sternocleidomastoid

Superior pedicle

The superior pedicle is the sternocleidomastoid branch of the occipital artery (Figure 1a and b). This is the major blood supply to the superior third of the sternocleidomastoid, if not the entire muscle,Reference Tanaka, Yamaguchi, Ogi and Kohama10,Reference Yugueros and Woods13 and is the pedicle on which the flap has been based most frequently.Reference Kierner, Zelenka and Gstoettner1 Fróes et al.Reference Fróes, Castro De Tolosa, Camargo, Pompeu and Liberti14 studied 30 cadaveric specimens, and found that the thin sternocleidomastoid branch of the occipital artery entered at the base of the muscle's superior third, along with the accessory nerve. From here it supplies the superior third consistently, and can branch longitudinally below this level or form one main branch.Reference Kierner, Aigner, Zelenka, Riedl and Burian5,Reference Fróes, Castro De Tolosa, Camargo, Pompeu and Liberti14–Reference Leclère, Vacher and Benchaa16

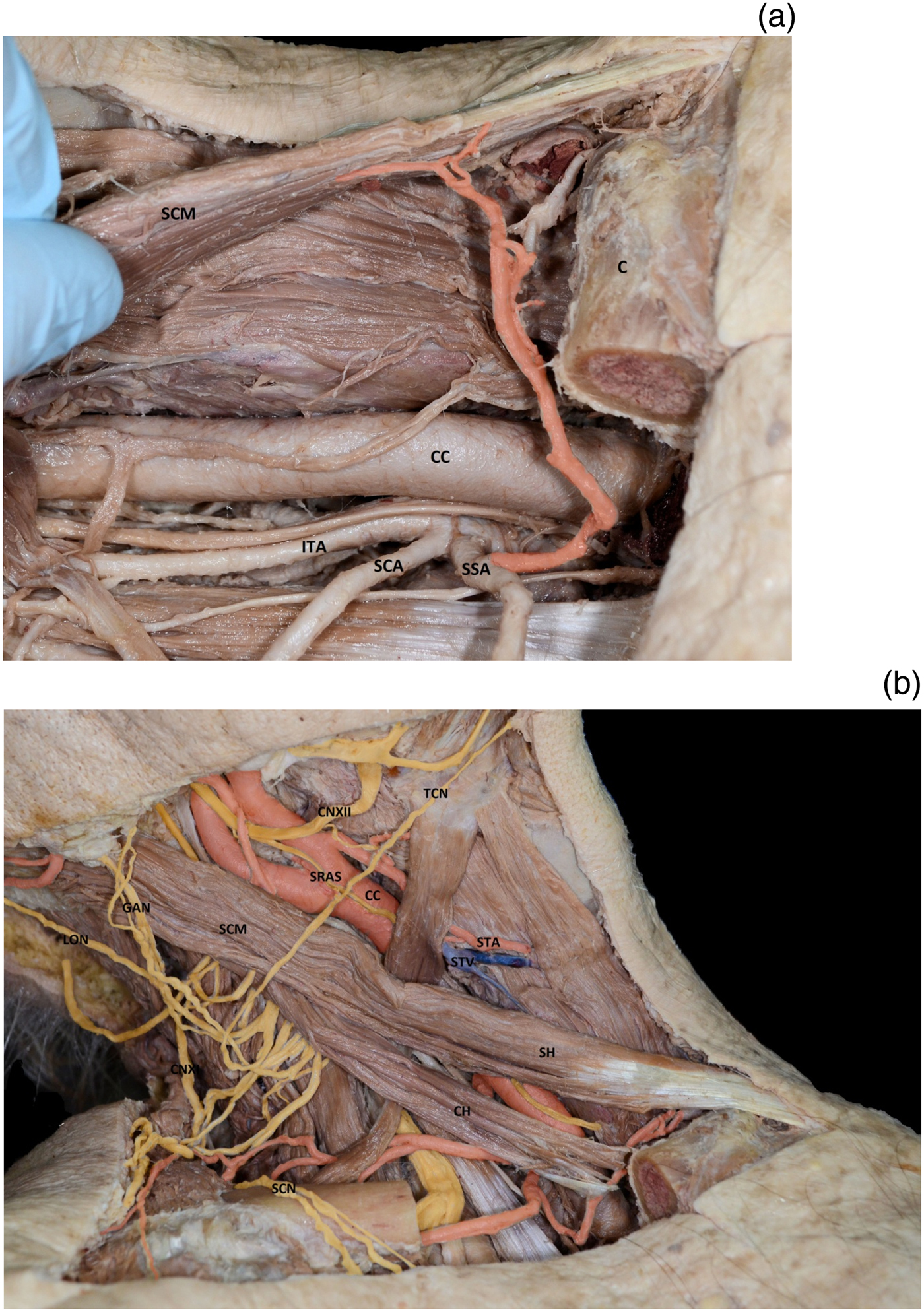

Fig. 1. (a & b) Cadaveric dissection images demonstrating the blood supply to the superior pedicle of the sternocleidomastoid (the red coloured branch is the sternocleidomastoid branch of the occipital artery). OA = occipital artery; ECA = external carotid artery; CNXII = 12th cranial (hypoglossal) nerve; OMH = omohyoid; SCM = sternocleidomastoid; CC = common carotid

As the superior pedicle almost never reaches the inferior pole of sternocleidomastoid, a flap based on this alone is unlikely to be well vascularised at its distal end, which could lead to ischaemic complications.Reference Leclère, Vacher and Benchaa16 This may have caused necrosis and flap failure in previous studies that utilised the superior pedicle only.Reference Yugueros and Woods13,Reference Gołcabek and Kondratowicz17

Middle pedicle

The middle pedicle of the sternocleidomastoid is either a branch of the superior thyroid artery (80 per cent), a branch directly from the external carotid artery (20 per cent)Reference Avery18,Reference Ozgur, Govsa, Celik and Ozgur19 or it branches from both.Reference Kierner, Aigner, Zelenka, Riedl and Burian5 These branches can display variety in origin, and travel superficially to the carotid sheath en route to the sternocleidomastoid.Reference Ozgur, Govsa, Celik and Ozgur19

Yugueros and WoodsReference Yugueros and Woods13 suggested that the superior thyroid artery most likely supplies the entire muscle, though they based their flaps on only the superior pedicle. Wei et al.Reference Wei, Liu, Zhao, Zhu, Li and Wang20 proposed that the branch from the superior thyroid artery is the main blood supply to the sternocleidomastoid. Their view was supported by Khazaeni and colleagues’ successful results,Reference Khazaeni, Rajati, Shahabi and Mashhadi21 basing their flaps on only the middle pedicle. Other reports suggest that the branch from the superior thyroid artery splits to supply the sternal and clavicular heads separately, thus allowing the muscle to be divided and one head to be taken as a flap.Reference Alagoz, Uysal, Tuccar and Sensoz22 The area supplied by the superior thyroid artery branch remains controversial, and there is a need for robust anatomical studies to confirm the area this vessel supplies.

Inferior pedicle

The inferior pedicle is the most disputed.Reference Kierner, Aigner, Zelenka, Riedl and Burian5 It is now thought to originate from a branch of the suprascapular artery (Figure 2).Reference Kierner, Aigner, Zelenka, Riedl and Burian5,Reference Leclère, Vacher and Benchaa16 More rarely, the inferior pedicle is a branch of the superior thyroid artery or transverse cervical artery.Reference Kierner, Aigner, Zelenka, Riedl and Burian5 These variations are important in surgery, as branches from the transverse cervical artery will appear more cranially than the usual inferior pedicle.Reference Kierner, Aigner, Zelenka, Riedl and Burian5 The inferior pedicle cannot be relied on to perfuse the entire muscle, as demonstrated with the injection of neoprene-latex, which only reached the superior third in 13 per cent of 15 specimens.Reference Leclère, Vacher and Benchaa16

Fig. 2. Cadaveric dissection images demonstrating (a) the blood supply to the inferior pedicle of the sternocleidomastoid (the red coloured branch is the sternocleidomastoid branch of the suprascapular artery), and (b) the anatomical relationship of the sternocleidomastoid to the nerves and vessels of the neck. Yellow = nerves, red = arteries and blue = veins. SCM = sternocleidomastoid; C = clavicle; CC = common carotid; ITA = inferior thyroid artery; SCA = superficial cervical artery; SSA = suprascapular artery; LON = lesser occipital nerve; GAN = great auricular nerve; CNXII = 12th cranial (hypoglossal) nerve; TCN = transverse cervical nerve; SRAS = superior root ansa cervicalis; STA = superior thyroid artery; STV = superior thyroid vein; CNXI = 11th cranial (accessory) nerve; SH = sternal head; CH = clavicular head; SCN = supraclavicular nerves

Venous drainage

Venous drainage usually reflects the arterial supply.Reference Yugueros and Woods13 In the published literature, it is mentioned considerably less than arterial supply, although its importance is well-recognised.Reference Marx and Mcdonald4,Reference Chen and Chang8,Reference Gołcabek and Kondratowicz17,Reference Cho, Mignogna, Garay and Blitzer23 Chen and ChangReference Chen and Chang8 quantified veins left to drain each flap, which other studies invariably failed to do. They concluded that the maximum number of veins should be left, to aid venous drainage. They also suggested conserving the superior part of the external jugular vein for another channel of venous flow.

Other studies proposed venous insufficiency as a major reason for flap failure.Reference Gołcabek and Kondratowicz17,Reference Cho, Mignogna, Garay and Blitzer23 Veins are particularly susceptible to intra-operative injury, so care must be taken not to exert excessive tension.Reference Gołcabek and Kondratowicz17

Summary of reported complications

Necrosis of the sternocleidomastoid flap is relatively high, although this is mainly accounted for by partial epithelial necrosis of the myocutaneous flap (Table 1).Reference Ellabban3,Reference Laccourreye, Ménard, Behm, Garcia, Cauchois and Holsinger6,Reference Chen and Chang8–Reference Tanaka, Yamaguchi, Ogi and Kohama10,Reference Wei, Liu, Zhao, Zhu, Li and Wang20,Reference Ariyan24–Reference Zhao, Yu, Xie, Zhang, Xu and Chen26 Partial epithelial necrosis is difficult to prevent, with no conclusive evidence that preserving two or more pedicles to the flap prevents this.Reference Marx and Mcdonald4,Reference Kumar, Gaud, Shukla and Pandey9,Reference Gołcabek and Kondratowicz17 Nor does the technique of suturing the skin to underlying muscle, to decrease the shearing of skin perforators, seem to prevent partial epithelial necrosis.Reference Noland, Ingraham and Lee7,Reference Yugueros and Woods13,Reference Wei, Liu, Zhao, Zhu, Li and Wang20 However, as partial epithelial necrosis can nearly always be relied upon to heal with conservative management alone, many authors discount the importance of partial epithelial necrosis.Reference Kierner, Zelenka and Gstoettner1,Reference Chen and Chang8,Reference Tanaka, Yamaguchi, Ogi and Kohama10 Disregarding partial epithelial necrosis would decrease the complication rate of the sternocleidomastoid flap to a more acceptable figure.

Table 1. Complications of sternocleidomastoid flap since 2001*

* Table based on the design of Ariyan (1997; page 69).Reference Ariyan24

Interestingly, all of the studies that reported fistula development have based the sternocleidomastoid flap upon one pedicle.Reference Alvi and Stegnjajic2,Reference Ellabban3,Reference Laccourreye, Ménard, Behm, Garcia, Cauchois and Holsinger6,Reference Yugueros and Woods13,Reference Ariyan24 Authors who have preserved two vascular pedicles have not reported fistulae. Basing the sternocleidomastoid on only one vascular pedicle may lead to greater risk of fistulae.

Muscle necrosis has been reported, although very rarely.Reference Kierner, Zelenka and Gstoettner1 Cho et al.,Reference Cho, Mignogna, Garay and Blitzer23 Gołcabek and Kondratowicz,Reference Gołcabek and Kondratowicz17 and Marx and Mcdonald,Reference Marx and Mcdonald4 all experienced muscle necrosis in their studies. The number of pedicles does not seem to impact muscle necrosis, as Marx and McdonaldReference Marx and Mcdonald4 preserved two, whilst Gołcabek and Kondratowicz,Reference Gołcabek and Kondratowicz17 and Cho et al.,Reference Cho, Mignogna, Garay and Blitzer23 only preserved one pedicle.

Overall failure rate, comparison of techniques and other flaps

The overall complication rate of the sternocleidomastoid flap varies significantly between studies (Table 1). The majority of studies, especially more recent ones, have complication rates between 10 and 30 per cent. As shown in Figure 3, there is a general trend of decreasing complication rates with the more recent studies.Reference Alvi and Stegnjajic2–Reference Marx and Mcdonald4,Reference Laccourreye, Ménard, Behm, Garcia, Cauchois and Holsinger6,Reference Chen and Chang8–Reference Tanaka, Yamaguchi, Ogi and Kohama10,Reference Yugueros and Woods13,Reference Gołcabek and Kondratowicz17,Reference Wei, Liu, Zhao, Zhu, Li and Wang20,Reference Cho, Mignogna, Garay and Blitzer23–Reference Ross and Klenzner29 The complication rates reported in Table 1 were calculated per complication reported, and so may differ from studies that calculated it per flap (there were multiple complications per flap).Reference Kumar, Gaud, Shukla and Pandey9,Reference Cho, Mignogna, Garay and Blitzer23

Fig. 3. Reported complication rates of the sternocleidomastoid flap by year of study, based on data from: Sasaki (1980),Reference Sasaki27 Cho et al. (1983),Reference Cho, Mignogna, Garay and Blitzer23 Marx and Mcdonald (1985),Reference Marx and Mcdonald4 Charles et al. (1987),Reference Charles, Hamaker and Singer28 Gołcabek and Kondratowicz (1990),Reference Gołcabek and Kondratowicz17 Alvi and Stegnjajic (1994),Reference Alvi and Stegnjajic2 Yugueros and Woods (1996),Reference Yugueros and Woods13 Ariyan (1997),Reference Ariyan24 Ross and Klenzner (1998),Reference Ross and Klenzner29 Zhao et al. (2001),Reference Zhao, Zhang and Zhao25 Tanaka et al. (2003),Reference Tanaka, Yamaguchi, Ogi and Kohama10 Laccourreye et al. (2006),Reference Laccourreye, Ménard, Behm, Garcia, Cauchois and Holsinger6 Zhao et al. (2009),Reference Zhao, Yu, Xie, Zhang, Xu and Chen26 Kumar et al. (2009),Reference Kumar, Gaud, Shukla and Pandey9 Wei et al. (2013),Reference Wei, Liu, Zhao, Zhu, Li and Wang20 Chen and Chang (2015),Reference Chen and Chang8 and Ellabban (2016).Reference Ellabban3

The flap failure rate concerns those flaps that did not recover with conservative management.Reference Kierner, Zelenka and Gstoettner1 The overall failure rate of the myocutaneous sternocleidomastoid flap, as reported in Kierner and colleagues’ 2001 meta-analysis,Reference Kierner, Zelenka and Gstoettner1 was 7 per cent, whereas the overall complication rate was 21 per cent. This indicates that many complications were minor and healed without surgical intervention, as supported by the literature.Reference Tanaka, Yamaguchi, Ogi and Kohama10,Reference Ariyan30 Of the post-2001 studies, only 4 total myocutaneous flap losses were reported out of 215 in total, giving a failure rate of 1.9 per cent (Table 1).

This decrease in failure rate may be a result of improvements in the technique of raising the sternocleidomastoid flap. Many recent studies described preventing excessive tension on the sternocleidomastoid flap by suturing the skin to the muscle before rotation of the flap, to prevent the loss of the delicate perforators to the skin.Reference Kumar, Gaud, Shukla and Pandey9,Reference Tanaka, Yamaguchi, Ogi and Kohama10,Reference Wei, Liu, Zhao, Zhu, Li and Wang20,Reference Zhao, Zhang and Zhao25 Wei et al.Reference Wei, Liu, Zhao, Zhu, Li and Wang20 implemented checking for a good blood supply to the skin by rubbing the skin to see the refill rate. Preservation of the sternocleidomastoid branch of the superior thyroid artery may also play a role in the decreased failure rates. More recent studies have documented this alterationReference Chen and Chang8,Reference Kumar, Gaud, Shukla and Pandey9,Reference Wei, Liu, Zhao, Zhu, Li and Wang20 since the anatomical investigations by Kierner et al.Reference Kierner, Aigner, Zelenka, Riedl and Burian5 It is difficult to identify which of these techniques, if any, are useful given the differences between the study and flap designs.

Free flaps have a much greater success rate than sternocleidomastoid flaps, cited in the literature as over 95 per cent.Reference Yang, Li, Wu, Hu, Liu and Ji31 Compared to other regional flaps, the sternocleidomastoid flap also has a lower success rate. Cho et al.Reference Cho, Mignogna, Garay and Blitzer23 experienced a 60 per cent failure rate of sternocleidomastoid flaps, whereas pectoralis flaps had a lower rate of 21 per cent. However, a higher number of pectoralis flaps were tested. Zhao et al.Reference Zhao, Zhang and Zhao25 also found that the sternocleidomastoid flap had a lower success rate (around 90 per cent) compared to other regional flaps. The difference was much smaller between the different types, at about 2 per cent. Nevertheless, many authors still advocate the use of the sternocleidomastoid flap, especially in circumstances where the use of other flaps is not practicable.Reference Kierner, Zelenka and Gstoettner1,Reference Alvi and Stegnjajic2,Reference Chen and Chang8

Discussion

The controversy regarding the use of the sternocleidomastoid flap has centred on the high rate of ischaemic complications.Reference Kierner, Zelenka and Gstoettner1 Complication rates vary considerably, although they have apparently decreased in recent years (Figure 3). As it is difficult to compare studies, because of the differing techniques, flap types and defects described, the techniques that decrease complications are hard to elucidate. More studies that are similarly matched in terms of area and flap type need to be carried out, to examine the different techniques used and their success rates.

Preserving both the occipital artery and superior thyroid artery branches may ensure that blood supply reaches the entirety of the muscle.Reference Wei, Liu, Zhao, Zhu, Li and Wang20 Attempts to preserve the venous network of the sternocleidomastoid should also be made, so as to avoid excessive venous congestion.Reference Chen and Chang8

Knowledge of the blood supply is essential in flap planning.Reference Leclère, Vacher and Benchaa16 If pre-operative computed tomography angiograms were performed to identify arterial variations, the sternocleidomastoid flap could be based on the appropriate pedicle for each patient, as has been successful for free flaps.Reference Rozen, Ashton, Pan, Kiil, McClure and Grinsell32 Increased knowledge of the blood supply has led to technique alteration, most notably the preservation of two or more pedicles.Reference Kumar, Gaud, Shukla and Pandey9,Reference Wei, Liu, Zhao, Zhu, Li and Wang20 Although the sternocleidomastoid flap has a higher failure rate compared to other regional flaps,Reference Kumar, Gaud, Shukla and Pandey9 studies that preserved two or more pedicles to supply the sternocleidomastoid have reported greater success.Reference Marx and Mcdonald4,Reference Wei, Liu, Zhao, Zhu, Li and Wang20,Reference Sasaki27 Although two pedicles can limit flap rotation,Reference Avery18 Khazaeni et al.Reference Khazaeni, Rajati, Shahabi and Mashhadi21 overcame this by dissecting the middle pedicle to its maximal length. Noland et al.Reference Noland, Ingraham and Lee7 reported that the sternocleidomastoid can be strongly depended upon as a flap if two or more pedicles are preserved.

Conclusion

The studies analysed in this review demonstrate the great variety of reconstructive options provided by a sternocleidomastoid flap. These include: complex osteomuscular flaps taken with partial thickness clavicular bone for mandibular reconstruction; myocutaneous flaps for oral defects; split flaps that take only the sternal or clavicular head to avoid excess bulk; and conventional myofascial flaps to reinforce jejunal free flap anastomoses following laryngectomy, or cover the carotid in malnourished patients undergoing modified radical neck dissection.Reference Noland, Ingraham and Lee7,Reference Chen and Chang8,Reference Tanaka, Yamaguchi, Ogi and Kohama10,Reference Gołcabek and Kondratowicz17,Reference Wei, Liu, Zhao, Zhu, Li and Wang20,Reference Moody, Hunter, Nazerali and Lee33,Reference Gonzalez-Garcia, Moreno-Garcia, Moreno-Sanchez and Roman-Romero34

The sternocleidomastoid remains an easy-to-use flap, in a convenient location, with a shorter operating time required.Reference Ellabban3,Reference Kumar, Gaud, Shukla and Pandey9 The sternocleidomastoid should be considered as an alternative when: the patient cannot tolerate a long operating period, other flap sites are unsuitable or there is a lack of microvascular facilities.Reference Chen and Chang8,Reference Kumar, Gaud, Shukla and Pandey9 Under certain conditions, the sternocleidomastoid flap could provide an option for those patients with very few other options for reconstruction available to them.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks for the generosity of those that selflessly donated their bodies to medical science at the University of Leeds School of Medicine. The images included are of the cadaveric dissections conducted as part of an Anatomy Batchelor of Science dissertation by Larissa Jones at The University of Leeds.

Competing interests.

None declared