Introduction

On April 17, 2013, president Barack Obama called it a “shameful day for Washington” 1 after the Senate, debating gun control in response to the Sandy Hook school shooting in Newtown, Connecticut, failed to pass any new gun control legislation. In the years since Sandy Hook resurrected a politically dormant gun control debate, its focus has revolved around mass shooting events—Sandy Hook, Orlando, Las Vegas, and Parkland coming to dominate and shape the political and policy discourse involving gun control. But despite growing public support and the Democratic Party’s renewed commitment to the issue, Congress has failed to pass any new federal gun control legislation since Sandy Hook. Yet before the mass shooting lens took center stage, the gun control debate had an altogether different focus in the context of which saw the passage of landmark federal gun control legislation (the Brady Bill and the Assault Weapons Ban) during the 103rd Congress (1993–1994).

This paper traces the political development of Congressional 2 gun control issue framing (with a specific focus from the early 1990s to the present), demonstrating that there have been two primary contexts in which gun control policy has been debated over this time frame: as a component of general crime control and as a specific response to mass shooting events. It identifies the primary historical, political, and electoral forces shaping the gun control debate in a given period while distinguishing the critical changes that drove the evolution from a crime control to a mass shooting focus. It assesses the degree of policy coherence and electoral salience 3 specific to each context, illuminating why “gun control as crime control” had bipartisan Congressional support in the early 1990s and identifying what comparative disadvantages hinder the mass shooting focus of the present while also recognizing that the latter unfolded against a backdrop of heighted partisan polarization.

The paper concludes that although one cannot compare the crime control and mass shooting framing contexts in a political vacuum, the electoral implications particular to each are relevant for understanding legislative action or inaction in Congress over the past thirty years, if more so in some periods than others. For political scientists, the paper provides insight into how gun control issue frames have shaped gun policy debates and helped or hindered the legislative process. For historians, it details the political development of the Congressional gun control debate over the last three decades and makes a case for the greater relevance of issue framing in a historical over contemporary context.

Agenda Setting and the Policy Process

Agenda setting, or what issues make it into the legislative arena, is an essential component of the policy process—if not on the agenda, debates over the content or merit of specific policies are often relegated to the political backburner or not held at all. As an area of regulatory policy 4 that seeks to place restrictions on individual conduct, gun control is one of the more controversial and fiercely contested policy issues in the American political context, so when it makes it onto the legislative agenda, it is no small feat for gun control advocates. According to Kingdon’s multiple streams theory, 5 when different variables or “streams” intersect, they produce a window of opportunity for agenda setting on a particular issue. There are three main streams: first, an issue is viewed by the public as a major problem requiring government action (the problem stream), second, possibilities for policy action are proposed and reviewed and specific solutions emerge as the most feasible (the policy stream), and third, political factors such as swings in the national mood or the changing composition of legislative bodies converge (the political stream). This paper will demonstrate that all three streams were present in the “gun control as crime control” context of the early 1990s that saw legislative action, whereas only the “problem” stream has been present in the contemporary mass shooting context, where there has not been legislative movement.

Part I: Gun Control as Crime Control

Expressing her support for the federal Assault Weapons Ban during the gun control debates of the 103rd Congress (1993–1994), Republican representative Marge Roukema (NJ-5th) told her colleagues in the House, “This debate isn’t about hunting or the Second Amendment…This is about crime control and controlling the national epidemic of gun violence.” 6 In the era before mass shooting events came to dominate the political discourse, Roukema’s words typified how gun control policy was framed and debated. To comprehend why necessitates understanding the wider historical, political, and electoral context within which Congress operated. During this period, an issue frequently occupied national attention and influenced policy debate, an issue that would become entwined with (and would come to elevate the electoral significance of) gun control. This issue was crime.

The “Tough-on-Crime” Political Era

Beginning in the mid-1960s and continuing throughout the 1990s, concerns about crime dominated the political landscape in the United States. 7 The crime issue first came to national prominence during the 1964 presidential campaign, when Republican candidate Barry Goldwater called for the need to enforce “law and order” to address “violence in the streets” during his speech at the Republican national convention. 8 In the following decades, an abundance of crime policy (including capital punishment laws after its reinstatement by the Supreme Court in 1976, drug offense sentencing laws in 1986, and three-strikes sentencing laws in the early 1990s) would be adopted at the federal, state, and local levels, with punitive legislation predominating.

By the late 1980s, supporting a punitive crime policy agenda had become a prominent stance on the national stage. This was particularly evident during the presidential campaigns of the time, where the candidates battled to prove to the public that they were tougher on crime than their opponent was. Willie Horton and his infamous furlough (in which he committed assault, armed robbery, and rape while taking advantage of a weekend furlough program from his Massachusetts prison) took center stage during the 1988 presidential campaign, with Republican candidate George H. W. Bush using the incident to accuse his Democratic opponent Michael Dukakis, who was governor of Massachusetts during the incident, of being “soft on crime.” 9 Defending his lack of political experience during the 1992 presidential debates, Independent candidate Ross Perot stated, “Well, they’ve got a point… . I don’t have any experience in creating the most violent crime-ridden society in the industrialized world,” and Democrat Bill Clinton proclaimed that passing a tough omnibus crime bill “is going to be one of my highest priorities next January if I become president.” 10

Taking a hard line on crime was not merely a presidential campaign tactic; the issue was mentioned in nearly every State of the Union Address given from the late 1980s through the final year of the Clinton presidency. George H. W. Bush stated in 1991 “we need tough crime control legislation and we need it now,” 11 and Bill Clinton urged Congress to “pass a strong, smart, tough crime bill” 12 during his 1994 speech. And Clinton was not merely a rogue “tough-on-crime” Democrat amidst a sea of Republicans (Republicans historically having been viewed by the public as the party that was tougher on crime). 13 Numerous Congressional Democrats during this period followed his lead, advocating for punitive anticrime policies and running on tough-on-crime campaign platforms. For example, Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman and future president Joe Biden was one of the chief drafters of the 1994 omnibus crime bill, proudly referring to it throughout his career as the “1994 Biden Crime Bill,” 14 while House Speaker Tom Foley (WA-5th) touted his support for this same “tough crime bill” in radio ads during his 1994 reelection campaign. 15 Illinois Senator Paul Simon (D) summed up the tough-on-crime sentiment during this era astutely: “We all want to try to outdo each other looking tough on crime… . Nobody wants to have a 30-second commercial running against you that you’re soft on crime.” 16

Rising Crime Rates

The preoccupation with crime that epitomized this political era was not bred in a vacuum; concerns about crime, and particularly violent crime, were not unfounded. Since the mid-1960s, the national violent crime rate 17 had steadily increased, ultimately reaching a peak of 758.2 per 100,000 persons in 1991 (compared with a rate of 160.9 in 1960 and 366.7 in 2019). 18

Public Perceptions of Crime

Beyond crime statistics, public perceptions of crime were arguably the most influential in positioning crime as a top political issue. Crime would come to be viewed by many Americans as “a routine part of modern consciousness” 19 and “a major social problem in contemporary American society.” 20 The most compelling polling evidence addressing the electoral salience of the crime issue comes from the “Most Important Problem” question posed by the Gallup Organization. Throughout the 1990s, crime was frequently listed among the top issues concerning the public, often retaining the top spot. For example in August of 1994, more than half of respondents (52 percent) identified crime as the most important problem facing the country; this was greater than the 29 percent who named health care and the 27 percent who named the economy in general (refer to Table 1 and Figure 2). 21

Table 1. What do you think is the most important problem facing the country today? (August 1994)

Source: Gallup Poll, August 1994

Figure 1. Violent Crime in the United States (1960–2019)

Source: FBI Uniform Crime Reports (1960–2019).

Figure 2. “What do you think is the most important problem facing this country today?” (Gallup*)

Note: * These trends reflect the high response for each category in a given year.

Gun Control and the Politics of Crime

Faced with rising crime rates and growing public concerns about crime, politicians during this period promoted anticrime policy agendas for the purpose of thwarting criminal activity and reducing crime rates. Over time, an intertwined relationship between the crime and gun control issues emerged, with many coming to view gun control as a necessary anticrime measure. The first appearance of crime in the context of federal gun control occurred during Congressional debates over what would become the Gun Control Act of 1968. 22 Supporters such as Roman Pucinski (D: IL-11th) argued that gun control was a primary component of a broader agenda to tackle rising crime, telling the House, “Last week we passed a juvenile delinquency bill here in this Chamber. Several months ago we passed the Safe Streets Act. Now we are trying to strengthen gun control legislation. When you take all of these legislative efforts and put them into one package, then you can begin to hope that we will finally make some meaningful contribution toward reducing crime in this country.” 23 Yet despite the growing crime focus, the main impetus for the Act’s passage was pressure driven by the high-profile assassinations of the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. and Senator Robert F. Kennedy in 1968, as evidenced by swift Congressional movement on gun control following both assassinations. 24

Although the conservative-leaning national temperament of the 1980s under Republican president Ronald Reagan saw the enactment of legislation rolling back some provisions of the Gun Control Act, 25 by the early 1990s the pursuit of gun control as crime control was at the forefront of national attention with the help of Democratic president Bill Clinton, who made gun control a primary component of his anticrime agenda. On the campaign trail in 1992, Clinton told a crowd at a campaign stop in Houston, Texas that “I want to be tough on crime… . That’s why I believe you ought to be for the Brady Bill.” 26 Having won the 1992 presidential contest, in August of 1993 the now president Clinton publicly outlined plans for an omnibus anticrime package that included two main gun control policies—the Brady Bill (which mandated federal background checks on firearms purchasers and implemented a five-day waiting period for handgun purchases) and the Assault Weapons Ban (which prohibited the manufacture and sale of certain types of semiautomatic firearms and large capacity ammunition magazines for civilian use). But why during this period did Clinton and others view gun control as a critical component of a crime control policy agenda?

Policy Coherence: Gun Control as Crime Control

Although not every member of Congress embraced this position, the potential efficacy of gun control to reduce crime rates was plausible given that a connection between firearm use and violent crime rates during this period was difficult to dismiss. A 1995 Federal Bureau of Investigation report determined that between 1985 and 1994, “firearms related offenses were chiefly responsible for the 42 percent increase in murders, robberies, and aggravated assaults that were reported.” 27 The FBI ultimately concluded that the 1990s had become “The decade most prone to firearm use for violent crime.” 28

And more specifically, in terms of policy coherence (the clarity and strength of the causal link between policy and desired outcome), making a case for how the specific gun control policies being proposed could help to reduce violent crime was relatively straightforward. During floor debates, several Brady Bill supporters cited the success of similar legislation in their own states; this included representative Michael Castle (R:DE-at large), who lauded Delaware’s computerized instant background check system, which he reported had prevented 1,150 illegal handgun purchases from individuals with criminal records since its implementation in January 1991. 29 As Senator Bill Bradley (D:NJ) argued in reference to another state background checks law, “How can anyone say that stopping 10,000 handgun purchases by convicted felons has not made a difference?” 30 When it came to the proposed ban on assault weapons, many supporters like Rosa DeLauro (D:CT-3rd) cited FBI statistics indicating that although assault weapons accounted for less than one percent of privately owned guns in the nation, they were used in a disproportionate amount of all violent crimes (8.4 percent) in 1993 and were 18 times more likely to kill police officers than conventional firearms. 31

This policy clarity appeared to translate for the public, as a majority reported believing that gun availability and crime rates were linked, that gun control was a crucial component of crime control. For example, an April 1993 Harvard School of Public Health poll asked respondents “How much do you feel that the availability of guns and the increase in the number of guns that are sold and bought have contributed to the violence that exists now?” with 61 percent answering that the availability of guns contributed “a great deal” to existing violence. 32 In terms of gun control as a policy response, an August 1993 Time Magazine/CNN poll asked respondents “Do you think that legislation designed to reduce the amount of violent crime in this country can do so without imposing stricter gun control laws, or do you think stricter gun control laws are a necessary part of any anti-crime bill?” Overall, 65 percent responded that gun control laws were “necessary to any anti-crime bill” compared with 28 percent who said an anticrime bill “could reduce crime without gun control.” 33

The Debate Rhetoric: Gun Control as Crime Control

Although mass shootings were not unheard of during this period (and in fact the Assault Weapons Ban had initially been introduced in response to a mass shooting at an elementary school in Stockton, California, where five were killed and 32 wounded in 1989), given the broader context of peaking crime rates and public concerns about crime, during the early 1990s gun control policy was primarily being considered in terms of its efficacy as a general crime reduction tool.

During floor debates in the House and Senate, much of the rhetoric referred to gun violence and crime in general terms (and typically with an urban/inner city implication), focusing on both as nationwide epidemics rather than referring to localized or specific tragedies of gun violence. For example, representative James Traficant (D:OH-17th) opined that “We have drive-through, drive-by, and drive-in shootings. Americans are not safe in their own homes” 34 while Butler Derrick (D:SC-3rd) told the House, “It is time to take back our streets from the criminals and to end the carnage that has made us all prisoners of our own fear.” 35

While pro-controllers justified their support by explaining how the specific policies being debated had the potential to reduce crime, those on the opposite side of the issue also framed their arguments in crime terms but offered alternative policy solutions to gun control. Although some contended that more guns would reduce crime, the more popular approach was to argue that the criminals themselves, not access to guns, was the fundamental issue at hand, Senator Bob Smith (R:NH) stating, “We need to control crime by cracking down on criminals, not guns.” 36 To crack down on the criminals themselves, individuals such as Senator Slade Gorton (R:WA) argued for stiffer sentencing penalties for those caught using a firearm in the commission of a crime in order to “put violent offenders away for life and make gang members think twice before picking up a firearm.” 37 For anticontrollers, addressing gun violence and being tough on crime could be done effectively without passing stricter gun controls.

The Electoral Significance of Gun Control as Crime Control

The Brady Bill and the Assault Weapons Ban each passed in both chambers of Congress and were signed into federal law; this represented a watershed moment for federal gun control policy, 38 as these bills were considered the strictest and most comprehensive gun control legislation to be passed by Congress. But why was the broader crime context so critical for achieving the passage of the Brady Bill and the Assault Weapons Ban during the 103rd Congress (1993–1994)? In other words, why did gun control as crime control work?

Technically, there had long been majority public support for gun control irrespective of crime rates or public concerns about crime. According to the Gallup Organization, no less than 59 percent (and on average roughly two-thirds) of Americans consistently reported favoring the passage of stricter gun controls from the mid-1970s up to the time frame of the 103rd Congress; Erskine (1983) summed up her analysis of gun control polling with the following statement: “The vast majority of Americans have favored some kind of action for the control of civilian firearms at least as long as modern polling has been in existence.” 39 And in terms of the specific policies being considered during this period, there was also majority public support. 40

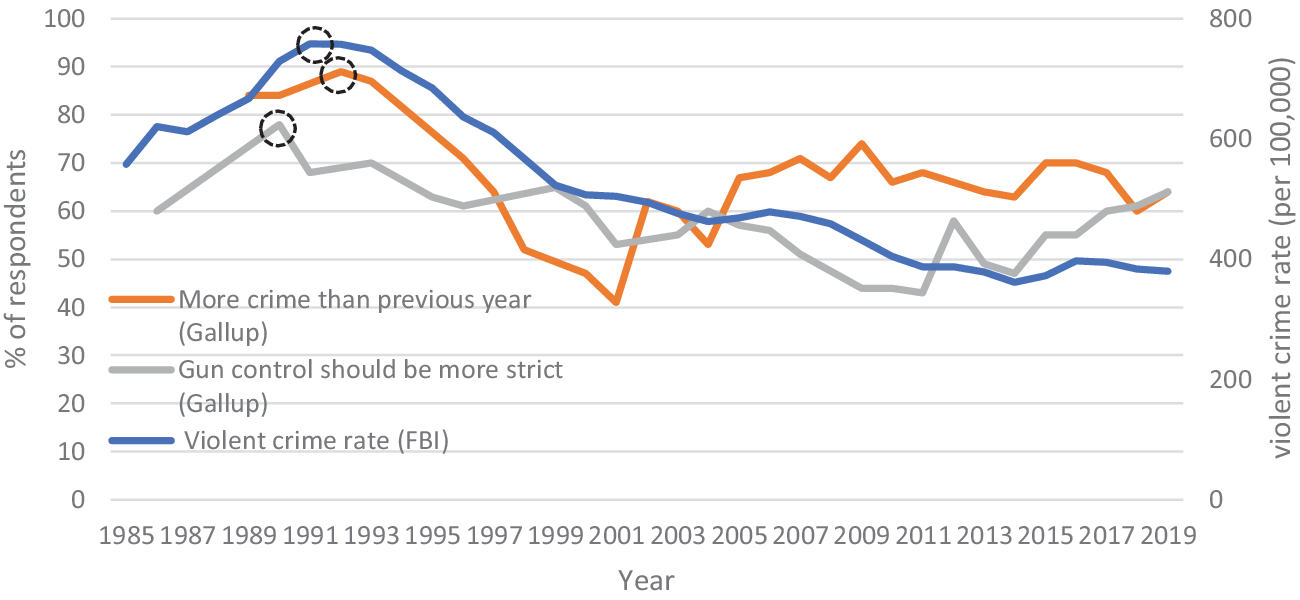

Yet what is critical to understand is that although there had long been majority public support for gun control, it had never achieved the status of priority political issue in its own right—for example never featuring prominently in presidential election campaigns or having been top or near the top of the Gallup organization’s list of “Most Important Problem”(s) facing the country. Crime on the other hand, had—and as the crime and gun control issues became entwined politically (an outcome that gun control advocates encouraged) and with a majority of the public viewing gun control as a necessary component of crime control, the salience of crime elevated the electoral significance of the gun control issue. That public support for stricter gun control generally reached peak levels within two years of when the national violent crime rate and public concerns about rising crime also peaked (peak levels for each are circled in Figure 3 below) indicates a compelling link between crime concerns and support for gun control among the public during this period.

Figure 3. Violent Crime Rates and Public Opinion on Crime, Gun Control (FBI, Gallup)

Sources: FBI Uniform Crime Reports; “Guns” and “Crime” (Gallup historical trends).

For many members of Congress, this translated into significant pressure to support gun control to appear tough on crime. In particular this affected those representing states or districts containing or in close proximity to urban areas, where crime rates were higher than the national average and where both public fear of crime and public support for gun control was highest. 41

Although by this point the parties had long since established divergent platform positions on gun control (The Democratic Party advocating for restrictions on gun ownership and the Republican Party for gun ownership free from government regulation), 42 during this era there were variables influencing Congressional gun control voting that cut across partisanship and political ideology, such as regional location and district/area type. 43 Thus, despite the Democratic Party having a majority in both chambers, because there was a sizable group of Democrats opposed to president Clinton’s gun control agenda (a group heavily comprised of Southern and rural representatives), the passage of the Brady Bill and the Assault Weapons Ban necessitated (and would receive) Republican support, most of which came from the aforementioned types of representatives facing heightened pressure because of the crime issue.

One such example was Steven Horn (CA:38th), a political moderate representing California’s 38th Congressional district—an ethnically and economically diverse urban district covering portions of southeastern Los Angeles county. According to the Los Angeles Times, it was a place where “rising crime had become an obsession” and a district whose constituents (80 percent according to a poll conducted by Horn’s staffers) expressed support for the Assault Weapons Ban. 44 On the opposite side of the country was Susan Molinari of New York’s Staten Island-based 13th Congressional district. Prior to entering Congress, Molinari had served on the City Council and had opposed a resolution urging Congress to ban assault weapons, earning her the endorsement of the NRA during her 1990 House campaign. But when Molinari later voiced her support for the Brady Bill (legislation that her crime-concerned constituents in one of the nation’s highest crime cities overwhelmingly supported) the organization publicly attacked her, calling her a turncoat. In response, Molinari stated of the NRA, “They put a lot of legislators in very untenable positions” 45 and went on to vote for both the Brady Bill and the Assault Weapons Ban during the 103rd Congress.

Another pro-control Republican was conservative Henry Hyde, whose district (Illinois’s 6th) comprised the suburbs of Chicago, a city that in 1992 had the fourth highest violent crime rate (30.3 per 1,000) in the nation. 46 Suburban representatives often faced pressure similar to that of their urban colleagues, as the public belief (often perpetuated by the media) that urban crime was bleeding into the suburbs was widespread during this period. 47 Hyde established himself as one of the most vocal pro-controllers of the 103rd Congress, his support for gun control following both a 1991 Chicago Tribune report that violent crime had risen by ten percent in suburban Cook county 48 (parts of which fell within Hyde’s Congressional district) and the results of district polling conducted by his staffers that revealed that 74 percent of his constituents supported stronger gun control measures. Hyde cited this polling in justification of his vote in favor of the Assault Weapons Ban, stating, “It bolstered my opinion that I wasn’t off the wall in voting to support this.” 49 And Republican gun control support was not limited to the House; 10 Senators supported the assault weapons ban and 16 the Brady Bill, the latter group including conservatives Strom Thurmond (SC) and Kay Hutchison (TX).

Gun Control as Crime Control: Conclusions

Ultimately, debating gun control as a component of an anticrime policy agenda worked during this period because the salience of crime elevated the electoral significance of gun control to the extent needed to engender bipartisan support to pass the legislation. Although achieving this did not occur overnight (both bills had been introduced in previous Congresses and had either failed to pass or had stalled at the conference committee stage; it was also a time when Republican presidents Reagan and Bush held veto power), in time a convergence of factors coalesced to provide the political momentum necessary to tip the scales. During this period, all three streams of Kingdon’s multiple streams theory were present. Against a backdrop of peaking crime rates, crime was viewed by the public as a major problem requiring government action (the problem stream), gun control was identified as a plausible policy solution to help reduce crime rates (the policy stream), and there was significant public support and a president (Clinton) dedicated to galvanizing his party 50 in pursuit of a gun-control-as-crime-control agenda (the political stream).

It was also a time when, although polarized, the issue was not yet hyperpartisan, which allowed space for flexibility in support and for shifts in voting patterns. The Reagan-era brand of conservatism allowed for a degree of flexibility when it came to the gun control issue (with Reagan himself supporting the Brady Bill and the Assault Weapons Ban after he left office), and in Congress there was a vocal contingent of “common sense” conservatives supporting gun control. 51 There was also relative freedom (compared with later decades) to change one’s position and recalibrate with the shifting political winds, as was the case for 30 Democrats and 9 Republicans who changed their votes to support the Assault Weapons Ban between 1991 and 1994. 52

Part II: The Mass Shooting Era

Although the focus on gun control as crime control dominated the debates of the early 1990s, over time this framing lens would shift, replaced by the mass-shooting focus of the present. This change did not occur overnight.

The issue of mass shootings first came to national prominence in April of 1999, after a school shooting at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, left twelve students and one teacher dead. Columbine was by no means the first school shooting to occur in the United States, nor was it the highest casualty mass shooting event up to that point. 53 However, it was the first to unfold on live television, as CNN and other television networks broadcast footage of SWAT police running alongside terrified teenagers exiting the school, their arms raised above their heads. 54 With Columbine generating more media attention and a higher public profile than other mass shootings, Congress acted quickly—with floor debate beginning in the Senate a month after the event.

Given that they were debating gun control policy in response to a specific event, the rhetoric used from those on both sides of the issue was adapted to better fit the circumstances of the case. Gun control proponents emphasized a need for stricter gun controls to protect America’s children, representatives such as Nancy Johnson (R:CT-6th) and Senator Herb Kohl (D:WI) expressing support because “It is children’s lives at stake,” and Congress’s responsibility to “help make children safer.” 55 And with media reports emerging of the school shooters as angry youths in black trench coats who enjoyed gory Hollywood films and played violent video games, 56 gun control opponents emphasized the negative influence of violent media and entertainment depictions on youth culture, representatives such as Ralph Hall (D:TX-4th) laying the blame for what happened at Columbine on “the amount of sex and violence in our children’s music, movies and games.” 57

Yet despite a burgeoning focus on mass shootings, the gun control debates of 1999 were part of a wider post Columbine debate being held about juvenile crime and violence in the United States. The main bills being considered in each chamber were omnibus juvenile crime bills that contained numerous provisions, including grants of 1.5 billion to the states for “fighting crime,” funding for more drug testing in schools, a provision providing prosecutorial discretion to U.S attorneys to try violent juvenile offenders as adults, and the creation of mandatory minimum sentences for youths convicted of violent crimes. 58 Although no new gun controls would be passed during these debates (due to a conglomeration of factors too complex to analyze in this paper), the crime and gun control issues remained intertwined.

The Decline of Crime

The eventual decline of the gun-control-as-crime-control focus was precipitated by the fading of crime as a priority political issue in the early 2000s, which occurred as crime rates continued to decline after peaking in 1991 (refer to Figure 1) and the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 shifted national attention toward concerns about terrorism, national security, and foreign policy. In May of 2002, the Gallup organization would report that the most important problem concerning Americans was terrorism (with 48 percent of respondents citing it as the most important issue compared with 29 percent who cited the economy and only 4 percent who cited crime/violence; refer to Figure 4).59 For the crime issue, this was a significant drop from the previous decade, when crime had consistently ranked top or among the top issues—a decade when terrorism did not register as a concern for the public.

Figure 4. Most Important Problem (Crime versus Terrorism)

Note: These trends reflect the high response for each category in a given year.

Due to their intertwined relationship, when the political salience of the crime issue faded that of gun control faded with it; although not explicitly abandoning support for it (public opinion remained relatively stable during this period), the public was focused on other issues. Seeing the political opportunity this afforded, Republican leaders (having majority control of Congress and the presidency and being the party of gun rights) began pursuing legislation to strengthen gun rights, putting forth bills such as landmark legislation to protect gun manufacturers from civil liability lawsuits. 60 For their part, Democratic leaders, told by party strategists (despite little empirical evidence to support the claim) that the gun issue had contributed to Al Gore’s 2000 presidential election loss, determined that gun control was no longer an electorally valuable, “winning” issue for the party and abandoned it as a legislative priority. 61 Thus the 2000s would see neither a crime control nor mass shooting debate focus, as the gun control issue descended into political dormancy.

The Revitalization of the Gun Control Debate

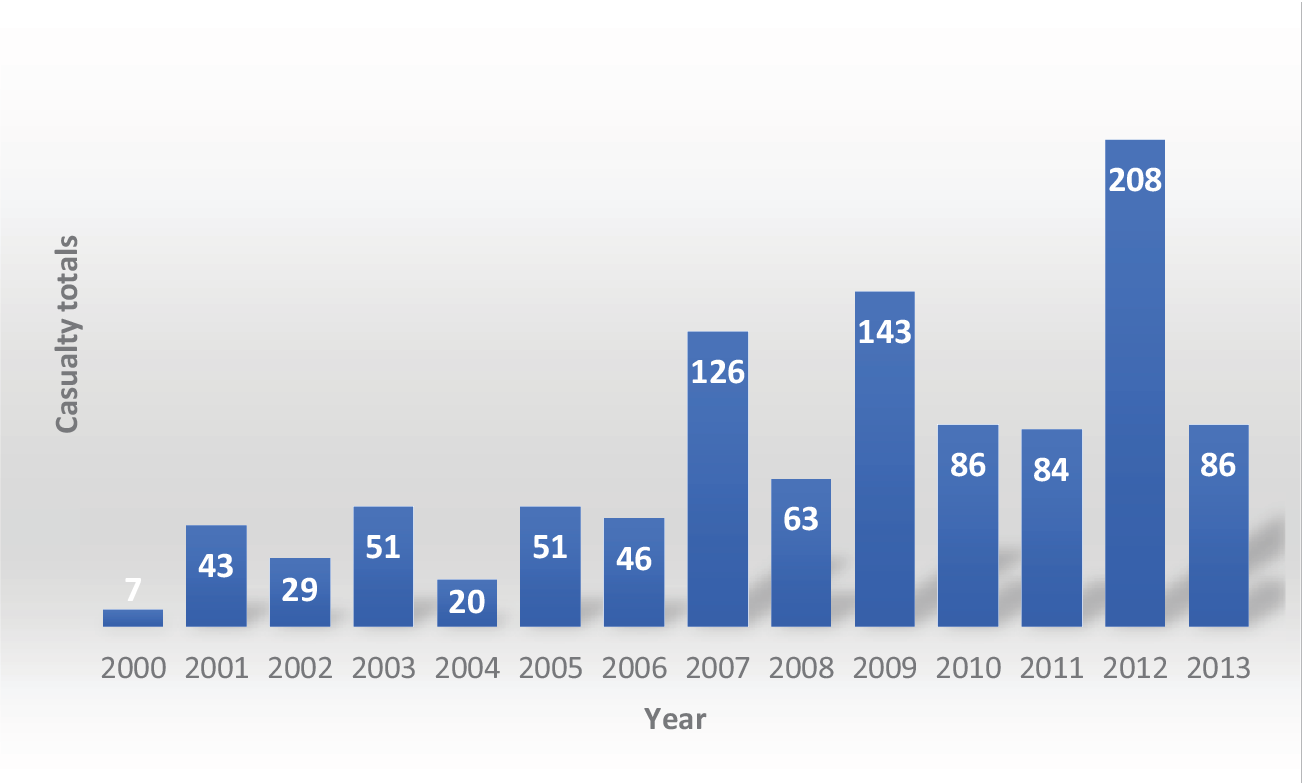

After a decade in which the issue was relegated to the political back burner, the Sandy Hook school shooting of December 2012 galvanized Democratic Party leaders to reclaim gun control as a legislative priority. Yet unlike during the previous era, their decision to pursue a gun control policy agenda was unrelated to concerns about crime broadly. Rather, the Democratic Party’s recommitment to the gun control cause after Sandy Hook can best be understood as a “tipping-point” response to the accumulation and increasing frequency of mass shooting events in the United States. According to a 2013 FBI report on 160 active shooter incidents in the United States between 2000 (the year after Columbine) and 2013, there was an increase in both annual frequency of incidents and annual casualty totals over the period of the study (refer to Figure 5).62

Figure 5. Annual Casualty Totals in Active Shooter Incidents 2000–2013 (FBI)

Source: A Study of Active Shooter Incidents in the United States between 2000 and 2013 (Federal Bureau of Investigation Report, September 16, 2013).

Additionally, a 2014 study by the Harvard School of Public Health on mass shootings similarly found an increase in annual casualty rates and frequency of mass shooting incidents over the period studied (1982 to 2014), with a notable increase in frequency after 2011, which they described as “part of a new, accelerated process.” 63

As Democratic Party leaders began speaking out in support of a renewed Congressional effort to enact gun controls, many emphasized that action was overdue to curtail the mass shooting epidemic that had become commonplace in the United States; president Obama proclaimed that “meaningful action” was needed because “We’ve endured too many of these tragedies in the past few years.” 64 Yet just five months earlier, in the aftermath of the Aurora movie theater shooting that killed twelve and injured 70, president Obama had evaded questions about gun control, instead telling the press at a campaign event, “There are going to be other days for politics. This, I think, is a day for prayer and reflection.” 65 Obama’s response was a continuation of the Democratic Party leadership’s tactical decision to distance the party from the issue that began after Al Gore’s presidential election loss in 2000; the party had avoided the issue for so long that when asked about gun control, pro-controllers such as Senator Dianne Feinstein (CA) lamented that “people haven’t rallied in years” and “it’s a bad time to embrace the subject.” 66

Mass Shootings: A Tipping Point

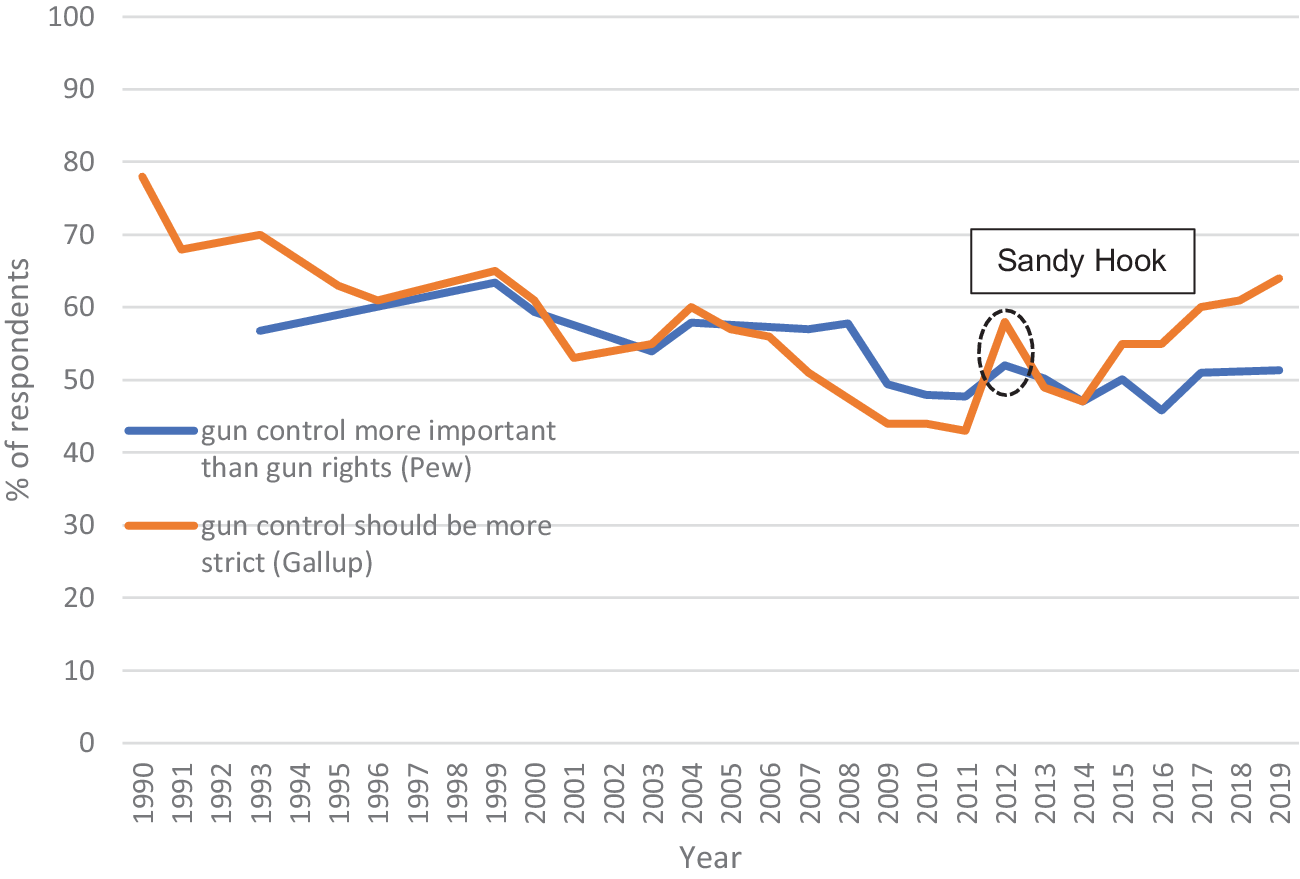

Given the Democratic Party’s notable recommitment, a question remains: Why was Sandy Hook specifically the tipping-point event that brought about the revitalization of the gun control debate? Why was this event considered “one too many” but not the Aurora shooting of July 2012, or the Virginia Tech shooting of 2007, or any other previous mass shooting incident? Similar to the convergence of factors that helped propel passage of the Brady Bill and the assault weapons ban during the 103rd Congress, a perfect storm of circumstances coalesced to provide the political momentum necessary to tip the scales in favor of resurrecting the gun control debate. With the 2012 presidential and Congressional elections over (removing the need for preelection political restraint) and against a backdrop of increasing casualty rates and frequency of mass shooting events (particularly in the prior year), Sandy Hook was the second deadliest mass shooting in U.S. history up to that point, surpassed only by the Virginia Tech shooting. And perhaps most significantly, it involved the deaths of twenty first graders, who were significantly younger than the age range typically affected by school shootings. Additionally, there was evidence to suggest that the American public had been similarly galvanized by the events at Sandy Hook, Gallup reporting a notable uptick in public support for stricter gun controls (refer to Figure 6).

Figure 6. Public Opinion on Gun Control (1990–2019)

Sources: “Gun Rights versus Gun Control” (Pew Research Center); “Guns” (Gallup historical trends).

The Debate Rhetoric: A Focus on Mass Shootings

As the Senate began to officially debate gun control in April 2013, it had been twenty years since the policy debates of the 103rd Congress. How had the debate rhetoric changed? As one example, regarding the perpetrators of gun violence, there has been a shift in focus from criminals broadly defined to individual mass shooters. Senator Dianne Feinstein (D:CA), sponsor of both the original Assault Weapons Ban and the 2013 renewal amendment, had during the debates of the 103rd Congress referred to assault weapons as the weapons of choice for every “terrorist, gang member, drug syndicate, drive-by shooter, and Mafioso.” 67 Yet during the 2013 debates, she focused on the need for such a ban to stop “grievance killers” such as Sandy Hook shooter Adam Lanza, stating, “Their goal is to kill indiscriminately… . These are the weapons of choice of this group of people.” 68 Although mass shootings were occurring in the United States throughout the 1990s, nameless, faceless criminals were the primary focus of the crime control debates of the 103rd Congress. In contrast, during and after the post-Sandy Hook debates, naming specific mass shooters has become commonplace—Adam Lanza, Omar Mateen, Dylan Roof, and Nikolas Cruz becoming household names for the American public.

Historically, a primary strategy of gun control opponents has been to propose an alternative policy solution to gun control. For example, during the 103rd Congress many argued that the best solution to reduce gun violence was not gun control but tougher sentencing penalties for those caught using firearms in the commission of a crime. Yet as the focus shifted from concerns about general crime to mass shootings, anticontrollers offered a different alternative policy solution to gun control: mental health legislation. As Senator John Cornyn (R:TX) explained, “I believe the most appropriate response to the recent mass shootings is to make sure that our current laws involving mental illness and mental health adjudications are enforced more aggressively and more efficiently.” 69

The myriad of ways in which gun control rhetoric has evolved in the decades since the 103rd Congress could comprise an entire paper in itself. In a broad sense, two quotes exemplify the change—one from Senator Nancy Kassebaum (R:KS) during the 103rd Congress and one from Senator Chris Murphy (D:CT) during the 113th. In the words of the former, gun control was primarily about “addressing a problem—escalating violent crime,” 70 whereas the latter contended, “We have an obligation to make sure it [a mass shooting like Sandy Hook] doesn’t happen again.” 71

Electoral Implications of the Mass Shooting Focus

Since the revitalization of the gun control debate in late 2012 with a mass-shooting-centered focus, no federal gun control legislation has been passed by Congress, despite multiple attempts. 72 There are numerous explanatory factors contributing to this, some specific to the mass shooting context itself. First, there is the issue of policy coherence. As discussed previously, when Congress debated gun control as a component of a crime control policy agenda, telling a causal story that linked the specific gun control policies being considered and reducing violent crime was relatively straightforward. In contrast, in the context of mass shootings, the causal link between policy and desired outcome is not as clear or persuasive, creating room to argue that the policies being debated (in fact the very same as in the crime era) won’t be effective at preventing them. 73 For example, despite consistently high levels of public support for background checks legislation, 74 gun control opponents in Congress, such as Senator John Cornyn (R:TX), have pointed out in floor debates that “no background bill would have prevented Adam Lanza (the Sandy Hook shooter) from acquiring these weapons which he effectively stole from his mother,” 75 a fact that gun control supporters conceded was true. Similarly, in terms of the Assault Weapons Ban, opponents such as Senator Chuck Grassley (R:IA) have argued that the previous ban (which expired due to a sunset provision in 2004) did not prevent mass shootings like Columbine in 1999, although they contend that the list of banned firearms is arbitrary, not covering more powerful assault weapons at the expense of popular ones. Grassley told the Senate, “It [the Assault Weapons Ban] did not stop Columbine. It would not stop Newtown… . A ban on guns based on their looks when more powerful guns are exempt would not satisfy any standard of review.” 76

Public opinion polling also suggests that the efficacy of gun control as a policy solution to prevent mass shootings is less clear or convincing than it was previously in the context of crime control. In November 1994, an ABC News poll asked respondents to what degree they believed making guns less available would reduce crime. Overall, 65 percent responded that making guns less available would be very or somewhat effective at reducing crime, far greater than the 35 percent responding that it would be very or somewhat ineffective. 77 In 2018, the Pew organization asked respondents whether they believed making it harder to obtain guns legally would lead to fewer mass shootings. The results were mixed, with 47 percent responding there would be fewer mass shootings and 46 percent that there would be no difference. 78 There also appears to be appetite for alternative policy solutions to gun control as a way to prevent mass shootings; in a poll on school shootings, the Gallup Organization asked respondents if they had to choose an approach to preventing them, would they rather Congress focus on making major changes to (1) laws on the sale of guns and ammunition or (2) laws on school security measures and the mental health system. More respondents reported they would rather see Congress focus on making major changes to the law regarding school security/the mental health system over changing laws on the sale of guns and ammunition (56 percent compared to 41 percent). 79

Electoral Salience and Mass Shootings

As a final point, another major difference between the crime control and mass shooting contexts involves issue salience. Although public support for stricter gun controls has increased in the years since the gun control debate was revitalized by Sandy Hook (enough to convince the Democratic Party that gun control is a winning issue nationally again), gun control support has not equaled peak levels, nor has the gun control issue achieved a comparable degree of electoral salience to what it had when it was linked to the crime issue during the height of crime concerns in the early 1990s. At the time when landmark federal gun control was passed during the 103rd Congress (1993–1994), crime was consistently top of the Gallup Organization’s “Most Important Problem”(s) concerning the public (see Figure 2) and a majority believed gun control was a crucial component of crime control. Crime rates, public concerns about crime, and public support for stricter gun control had all recently peaked within a two-year period—a compelling indication that crime concerns and support for gun control were linked.

In the mass shooting context, gun control has not benefitted from association with a priority political issue that heightens pressure on Congress to legislate. Although there has consistently been majority or near-majority public support, this support does not necessarily translate into the electoral salience needed to galvanize Congressional action. For example, in terms of Gallup’s polling, on its own, gun control historically has not ranked among the top issues concerning the public. There was a noteworthy spike after the Parkland school shooting; in polling conducted two weeks after the event, 13 percent identified guns/gun control as the most important problem, putting it in the number two position, below dissatisfaction with government and above immigration and race relations. 80 Although this was the highest gun control had ranked on this question in over twenty years, the momentum didn’t stick. Within a month, the percent identifying guns/gun control had declined to 6 percent and the issue had dropped to fourth; a month later it had resettled to its usual position. In late 2019 (before the COVID-19 pandemic came to dominate global attention, making 2020–2021 atypical years and thus not ideal for comparative purposes), 81 gun control remained at one percent, tied for the 14th position. Although electoral salience might fluctuate in the immediate aftermath of mass shooting events, unlike with the crime issue in the 1990s, the rises have not been sustained.

Scholars have cited the potential for unexpected, high-profile events (known in the literature as “focusing events”) to advance issues on the political agenda and in some instances, precipitate policy change. 82 Because of their high-profile nature, they draw immediate attention to problems needing policy solutions and they can lead to seismic shifts in public opinion in favor of policy change. Given these characteristics, one may expect mass shooting events like Sandy Hook or Parkland to fit this bill. Yet focusing events are most effective when there is a clear causal path for a policy agenda to address the problem and when there isn’t active advocacy opposition on the opposite side of the debate. Returning to Kingdon’s multiple streams theory, despite the potential of mass shootings as focusing events to generate change, the intersecting streams that combine to propel an agenda forward are not fully present in the mass shooting context. While mass shootings are viewed by the public as a major problem requiring government action (the problem stream), consensus that gun control is the necessary policy solution for preventing them is lacking, with mental health and school security emerging as competing options in the public mind (the policy stream). Meanwhile, partisan polarization, and specifically the decline in Republican support for gun control, is a major barrier to the pursuit of a federal gun control policy agenda (the political stream).

Gun Control and Partisan Polarization

Despite the differences in policy coherence and electoral salience between the crime control and mass shooting contexts, one cannot compare their efficacy in a political vacuum without considering the wider environment of political and electoral change that accompanied the framing shift. Beyond the electoral implications of issue framing, understanding legislative inaction on gun control in Congress today necessitates familiarity with a trend that has grown increasingly relevant for Congressional politics over time—partisan polarization.

Although there are differing interpretations as to its precise causes (disillusionment with the Democratic Party’s embrace of the civil rights and antiwar movements being one of the foremost theories), scholars are in general agreement that partisan polarization within the U.S. party system has its roots in the party realignment (particularly in the South) that occurred from roughly the mid-1960s onward as conservative southern Democrats began defecting to the Republican Party. 83 As this occurred it made the Democratic Party less ideologically conservative and the Republican Party more ideologically conservative; over time, party identification and political ideology became aligned due to sorting, as conservatives came to identify as Republicans and liberals as Democrats. 84 Ultimately, this realignment process precipitated partisan polarization by creating “for the first time in nearly sixty years, two sharply distinct political parties.” 85

But although party realignment initiated the process of partisan polarization, it did not complete it: as was evident through the votes of the 103rd Congress, during this period there was still bipartisan support for and opposition to gun control, with members of Congress crossing both partisan and ideological lines with their roll-call voting. Although by this point the parties had staked out divergent positions on gun control, there remained flexibility for deviating from the party line and for swings in voting patterns brought on by shifts in the political climate (like peaking concerns about crime). So what changed? One compelling explanation is that the shift from moderate levels of polarization in the 1990s to the hyperpolarization seen today was bolstered by the growth in political power of the Republican primary electorate. Beginning in the late 1990s, conservative ideological groups such as the Club for Growth, FreedomWorks, and Heritage Action began foraying into the congressional nomination process, funding primary challenges against incumbent Republicans they deemed to be insufficiently conservative. Over the past two decades, as these groups have gained political notoriety through the unseating of several prominent Republicans, congressional Republicans have come to face intense pressure to present themselves as “conservatives in good standing” in order to fend off/survive primary challenges—an electoral threat to which there is no real Democratic equivalent. 86

Given this pressure, it has become increasingly electorally risky for most Republicans to support gun control, for any vote for it would be considered a deviation from conservative principles, and primary voters tend to support the more conservative candidates. And with gun control not a priority political issue for the public (as is evident through the “Most Important Problem” poll), it is less likely that a vote against it will be a decisive factor for general election voters, even if there is majority bipartisan support for legislation such as background checks.

Although there are no comparable ideological groups or primary electorate driving a shift on the Democratic side, the party has also become increasingly united in support of gun control in the years since Sandy Hook. This has been aided by continued regional and district-type realignment (particularly a loss of southern and rural seats in Congress that has left behind a more solid pro-control majority) as well as a majority of Democratic swing voters coming to embrace the party position (and its contrast to the Republican one) as electorally valuable. Yet without full control of both chambers and the majorities needed to pass new gun controls without relying on Republican support, this newfound Democratic unity has not translated into legislative action.

A final point about polarization involves sorting among the general electorate. Sorting is a process in which partisans, reacting to cues from political elites, will bring their issue positions in line with their party identification. 87 Over time, as the partisan gap between political elites on gun control has widened, self-identified partisans in the general electorate (not to be confused with primary voters, who helped to drive [Republican] polarization while the other group sorted in response) have followed suit, as evidenced by a lagging electorate. 88 When voters sort, they tend to embrace the positions of the parties generally but not necessarily every policy stance, 89 which explains why, despite a widening gap on the issue broadly, there is still majority bipartisan support for specific policies such as background checks.

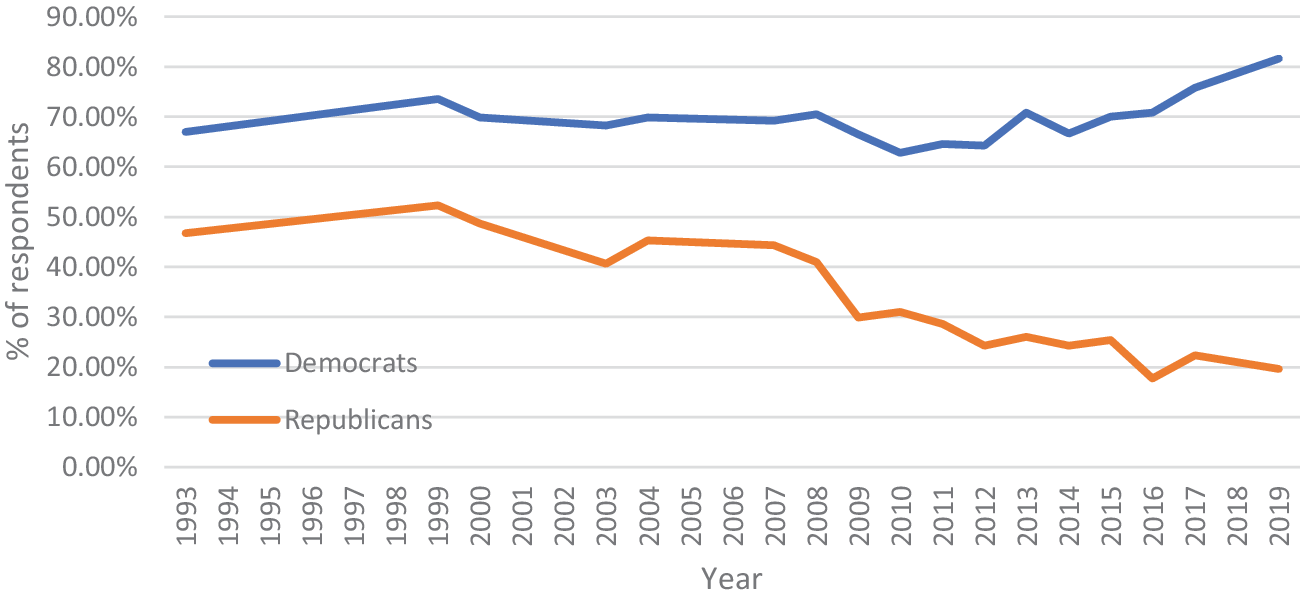

Over time, and particularly in the years since the gun control debate was revitalized by Sandy Hook in late 2012, Congress has become increasingly partisan polarized on the gun control issue and the general electorate has sorted in response (refer to Figure 7). For both parties, gun control positions have become part of their partisan identity—Democrats the protectors of America’s children from gun violence, Republicans the safe guarders of Second Amendment rights. There has been a significant decline in the existence of gun control moderates in Congress and in vote splitting (i.e., members voting for some, but not all or no gun control legislation), evidence to make a compelling case that the content of the specific policies being debated is no longer particularly relevant for understanding Congressional voting patterns—whether a background check bill, terrorist watch list gun purchasing ban, or concealed carry legislation (all very different policies), recent gun votes have all been nearly fully polarized along party lines.90 If the policies themselves have lost relevance in the context of hyperpolarization, it follows that the framing context has also lost relevance.

Figure 7. More Important to Control Gun Ownership (Pew)

Source: “Gun Rights versus Gun Control” (Pew Research Center).

Conclusion

Nonetheless, for both historical and contemporary analysis of the gun control debate, issue framing is an important variable, for it sheds critical light on the primary historical, political, and electoral factors influencing the debate in a specific period, and given the policy coherence and electoral implications specific to each framing context, it helps to illuminate why federal gun control agendas have been successful or unsuccessful, if more so in the past than in the present. One cannot compare the efficacy of the crime control and mass shooting framing lenses in a political vacuum, as they unfolded in starkly different historical, political, and electoral contexts. Would a return to a gun-control-as-crime-control focus break the spell of legislative stalemate in Congress today? It is unlikely. For despite the return of law-and-order rhetoric on the national stage in recent years, 91 polling suggests that compared with the 1990s, there is less public agreement over the relationship between guns and crime. According to a 2019 Pew poll, 37 percent of Americans responded that they believed there would be more crime if Americans owned more guns, compared with 55 percent responding to a similar question in 1994 (this same year, 65 percent of respondents reported in a separate poll that limiting gun availability would reduce crime). 92 And perhaps unsurprisingly, this weakening public agreement can largely be explained by partisan polarization. Although a partisan breakdown is not available for the 1994 poll, notably, in 2019 there is a wide partisan gap (41 percentage points) on the question—with 56 percent of Democrats and only 15 percent of Republicans responding that more guns would equal more crime—a gap even larger than that between gun and non-gun owners (36 points). Yet it would also be ineffectual to transplant this framing lens without replicating the historical context of peaking crime rates and public fear of crime that permeated that decade, a time when the public felt “such a terrible sense of crime.” 93

When considering each framing context in relation to Kingdon’s multiple streams agenda setting theory, each of the three criteria is present in the crime context, although only the problem stream is clearly present in the mass shooting era. Historically, gun control was at its most electorally salient as a political issue during the height of crime concerns in the 1990s, and debating gun control policy as an anticrime measure was successful in that particular context (with problem, policy, and political streams all coming together) to achieve the passage of landmark federal gun control legislation. Although debating gun control as a specific policy response to prevent mass shootings has been both less causally coherent and less electorally salient, the shift to a mass shooting focus also unfolded against a backdrop of heightened partisan polarization—the changing political calculus for Republicans in particular presenting a major obstacle for gun control enactment in the mass shooting context that was not present to the same degree in the crime era. Today, the policy and political streams aren’t working in a federal gun control agenda’s favor.