Indigenous scholars have done much to illuminate the ways in which power, politics, and colonialism irrevocably shape the data-generating process. While these interventions are diverse and wide-ranging, they broadly fall under one of two umbrella categories—“Indigenous statistics” (Walter and Andersen, Reference Walter and Andersen2016), and “Indigenous data sovereignty” (Kukutai and Taylor, Reference Kukutai and Taylor2016). Indigenous statistics primarily seek to reformulate and transform quantitative methods through Indigenous methodologies. It accomplishes this through centering Indigenous values, epistemologies, and ontologies to interrogate the colonial structures and relations that perpetuate Indigenous dispossession and sustain settler privilege. Meanwhile, the project of Indigenous data sovereignty primarily seeks to transform the broader terms within which quantitative data are used to govern and control Indigenous populations. It accomplishes this by interrogating the legal, political, and ethical relations that dictate the terms of ownership, storage, access, framing, analysis, and interpretation of data on Indigenous peoples. Of course, these projects are not mutually exclusive, and share a great deal of overlap.

Quantitative political scientists have much to learn from Indigenous scholars, not least in this respect. Quantitative scholarship on Indigenous politics is still a relatively nascent field in mainstream Political Science. While the field shows much promise, it can sometimes run into one or more of the following issues: (1) it insufficiently recognizes self-identification heterogeneities among Indigenous populations; (2) it adopts identity categories inherited from the ethnoracialFootnote 1 classification system of the settler-colonial state; and (3) it offers inadequate solutions to the methodological biases resulting from undersampling and lack of trust.

To address these issues more adequately, we offer the methodological framework for a decolonial quantitative political science, demonstrating how it was operationalized in the design and execution of the 2019 Native Hawaiian Survey. Building upon past “critical quantitative” projects and decolonial methods, we incorporate kanaka maoliFootnote 2 (Native Hawaiian) epistemology and participatory methods at all stages of the research process—including research design, data collection, analysis, and dissemination. The incorporation of participatory methods ensures that the research is designed and interpreted in ways which are responsive to how Indigenous communities think about themselves, and which are accountable to their needs and struggles. The grounding in Indigenous epistemology allows for a deeper theoretical understanding of the kinds of questions and concepts that are linked to the political project of decolonization, which can look very different among different Indigenous peoples.

Our methodological framework shares much with past Indigenous interventions into quantitative methods, but might be differentiated in several small ways. Like Indigenous statistics, we draw our theoretical frameworks and hypotheses from Indigenous epistemologies. And like Indigenous data sovereignty, we emphasize the importance of incorporating participatory methods and long-term accountability mechanisms at every stage of the research process. However, our framework differs from both in that it specifically emphasizes the importance of producing quantitative research that actively supports Indigenous (and specifically Kanaka ’Ōiwi here) calls for decolonization of lands and ocean, by uncovering the ongoing operations of settler-colonialism and colonialismFootnote 3 in the political lives of Indigenous peoples.

Aligned with the insights of kanaka scholars, we find empirical support for their long-standing theoretical claim that Native Hawaiian attitudes toward genealogy, Hawaiian sovereignty, and national identity are intertwined. Through a descriptive analysis of respondents' self-identification, we identify three self-identification clusters (what we term the “Hawaiian Sovereignty,” “American,” and “Hawaiian” clusters). Our empirical findings reveal that the standard data-generating process in quantitative studies on Native Hawaiians obfuscates heterogeneities in self-identification within the Native Hawaiian community, and that these identities are politically meaningful inasmuch as they share different, complex affinities with Hawaiian and American national identity.

This article offers two key contributions. First, it provides a methodological framework to guide quantitative social science research on Indigenous populations and demonstrates its utility through applying it in the study of Indigenous self-identification among Native Hawaiians. This methodological framework can be readily applied to quantitative research on other Indigenous populations (such as Native Americans, CHamorus,Footnote 4 Okinawans, etc.), but must incorporate the participation and epistemologies of the specific Indigenous population being studied. Second, this study provides empirical support for the intertwined political relationship between Native Hawaiian identity and national identity. Indigenous peoples are socially and culturally heterogeneous, and are also subject to heterogeneous modes of state recognition and governance. What they do share is an embeddedness within legacies of Indigenous dispossession under historical and ongoing settler-colonialism and colonialism (Komai, Reference Komai2021, this issue), which likely produces disjunctions between their Indigenous identity and national identity. This complex relationship may have enormous implications for how we understand and analyze Indigenous politics, but has hitherto been understudied by quantitative researchers.

Three issues in quantitative research on indigenous populations

Quantitative methods and Indigenous communities have a historically fraught relationship, not least because quantitative researchers have sometimes insufficiently contended with the role of power, politics, and colonialism in the data-generating process. We identify three broad issues facing quantitative research on Indigenous populations: (1) they insufficiently recognize self-identification heterogeneities among Indigenous populations; (2) they adopt identity categories inherited from the ethnoracial classification systems of settler-colonial states; and (3) they offer inadequate solutions to the methodological biases resulting from undersampling and lack of trust. These issues suggest the importance of amending the status quo of quantitative research on Indigenous populations.

Issue #1: recognizing heterogeneities in indigenous self-identification

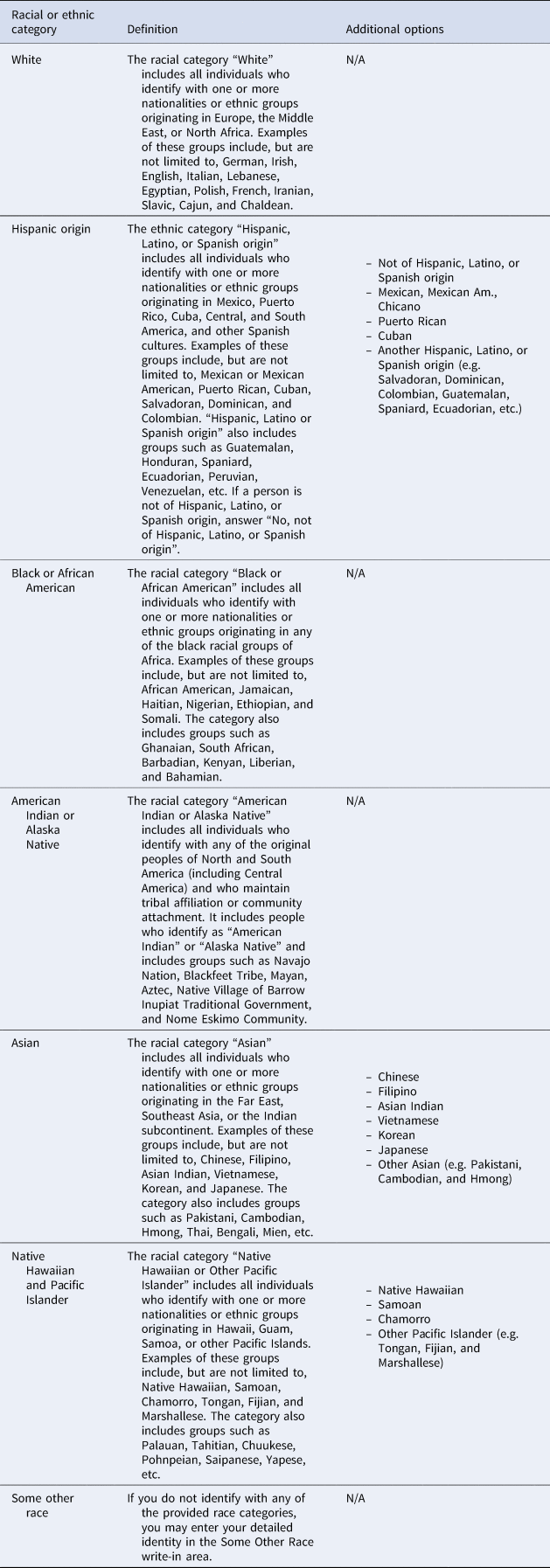

First, quantitative research on Indigenous populations across the United States—drawn from both administrative and survey data—typically deploy inherited categories of race and ethnicity from the U.S. Census. Per 62 Fed. Reg. 58,782 (October 30, 1997), the Census draws a hard distinction between race and ethnicity and includes fixed categories for both.Footnote 5 This distinction between race and ethnicity is one held by standard demographic studies, wherein “[r]ace denotes categorical distinctions based on physical features whereas ethnicity encapsulates cultural distinctions based on ancestry” (Moreno and Oropesa, Reference Moreno and Oropesa2012, 1221).

As with all socially constructed categories, there are inevitably mismatches between the ethnoracial categories ascribed to individuals, and how individuals perceive their own ethnoracial identity (Waters, Reference Waters1990; Landale and Oropesa, Reference Landale and Oropesa2002; Itzigsohn et al., Reference Itzigsohn, Giorguli and Vazquez2005; Golash-Boza and Darity, Reference Golash-Boza and Darity2008). Their ethnoracial self-identifications, in turn, may differ based on their social context and the ethnoracial classification systems of their national context (Okamura, Reference Okamura1981).

Yet, Indigeneity is categorically irreducible to ethnoracial identity. Wilkins and Stark (Reference Wilkins and Stark2007, 55) put it simply: “Indigenous Peoples are Nations, not [ethnoracial] minorities.” Indigenous peoples living within the United States and its territories form nations that have varying degrees of legal and political recognition from U.S. federal, state, local, and territorial governments. Indeed, understanding Indigenous nations involves the “unbraiding of closely examining…. issues of treble citizenship for Indigenous peoples, the nation or sovereign status of Indigenous polities, and the federal government's inconsistent understanding of its relationship to [Indigenous peoples]” (Wilkins and Stark, Reference Wilkins and Stark2007, 70). Unlike their Native American and Native Alaskan counterparts, Native Hawaiians do not constitute a federally recognized tribe. Indeed, they constitute “the largest Indigenous community with whom the United States has yet to formally establish a formal government-to-government relationship” (Wilkins and Stark, Reference Wilkins and Stark2007, 9), which has yielded complex, mixed, and evolving responses from Native Hawaiian communities (Kauanui, Reference Kauanui2008a).

While conceptualizations and practices of Indigeneity are heterogeneous both within and across Indigenous populations, a common refrain (at least among Native American and Indigenous Pacific Islander scholars) is that Indigeneity entails a political claim to land and/or ocean in ways that ethnoracial identity does not. The connections to the land and sea are key foundational elements of Indigenous identity and culture. For instance, Lumbee political scientist David E. Wilkins (Reference Wilkins and Stark2007, 51) affirms that all Indigenous communities have a natural political power because of tribal sovereignty—“the intangible and dynamic cultural force inherent in a given indigenous community, empowering that body toward the sustaining and enhancement of political, economic, and cultural integrity.” Similarly, kanaka scholar J. Kēhaulani Kauanui (Reference Kauanui2008a, Reference Kauanui2008b, 635) incisively differentiates between Indigenous politics as concerned with “territory, sovereignty and nationhood” and ethnoracial politics as concerned with civil rights—a distinction that Gordon and Lindsay (Reference Gordon and Lindsay2019) observe is necessary to recognize as a condition of meaningful Black-Indigenous solidarities, for instance.

In alignment with Indigenous scholarship, therefore, we categorically reject the reductionist treatment of Indigeneity as ethnoracial identity, which has been systematically used by the U. S. settler-colonial state as a tool of Indigenous dispossession (Kauanui, Reference Kauanui2008b). Instead, we draw on ethnoracial self-identification literature to understand how Indigenous peoples conceive of themselves as racialized subjects. Drawing from the limited evidence available, the self-identification of Indigenous peoples seems particularly complex and fraught, with scholars noting that multiracial Native American-Whites have the least stable self-identification over time (Doyle and Kao, Reference Doyle and Kao2007).

Scholars of race and ethnicity in Hawaiʻi have noted how the multiracial character of Native Hawaiians is deeply mismatched with the ethnoracial classification system of the United States. Through its monolithic treatment of Native Hawaiians in particular, the United States’ ethnoracial classification system obfuscates the importance of familial relationships and Indigenous ties to ancestral lands in the self-identification of Native Hawaiians (Kana'iaupuni and Liebler, Reference Kana'iaupuni and Liebler2005; Ledward, Reference Ledward2007).

Issue #2: inheriting ethnoracial categories from the settler-colonial state

Quantitative methods, driven by the noble imperatives of knowledge aggregation and statistical generalizability, often adopt standard ethnoracial categories for convenience and comparability. In doing so, they by default inadequately contend with the structures of power undergirding the formulation and adoption of inherited ethnoracial categories.

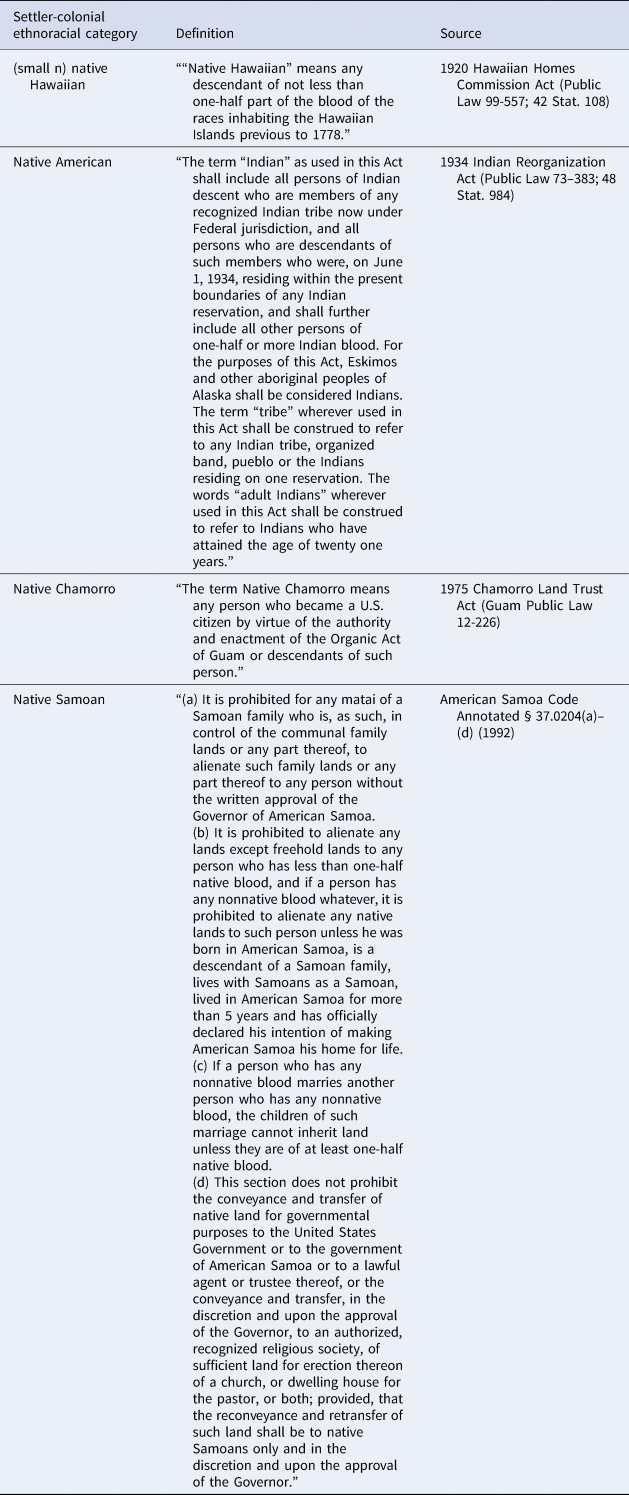

Within the United States, this issue is particularly critical for Indigenous populations—including but not limited to Native Americans, Native Hawaiians, CHamorus, and Native Samoans—for whom ethnoracial classification has been used as a tool for public resource allocation at the federal, state, and territory levels. Individuals meeting settler-colonial thresholds of Indigeneity (e.g. blood quantum laws) are designated as deserving recipients of resources such as scholarships, homestead leases, and small business incentives, etc. Despite the arbitrariness of such thresholds, and despite their disjunctions from how many Indigenous peoples understand and define their own Indigeneity, Indigenous peoples who fail to meet such thresholds are nonetheless deemed non-Indigenous and therefore undeserving of designated Indigenous rights and resources.Footnote 6

Under these settler-colonial laws, ethnoracial identification is narrowly defined, with important consequences for resource allocation and Indigenous rights. For Native Americans, blood quantum is critical for tribal citizenship. While different Native American tribal governments have established different thresholds for citizenship, many of them maintain blood quantum (and/or genealogical descent) as a key criterion for tribal citizenship (Rodriguez-Lonebear, Reference Rodriguez-Lonebear2021). While Native Hawaiians are not defined as Indigenous populations akin to Native Americans per federal law, the State of Hawai‘i defines “native Hawaiians” as those who have a blood quantum of 50% Hawaiian or more—and it is within these narrow, stringent terms that Native Hawaiians are granted (or not) access to resources such as homestead leases (Doyle and Kao, Reference Doyle and Kao2007) via the Department of Hawaiian Home Lands. For CHamorus, evidence of genealogical descent is also necessary for critical resources within the unincorporated territory of Guåhan (Guam)—most notably, homestead leases via the Chamorro Land Trust.

In a landmark critique of blood quantum laws in Hawaiʻi, Kauanui (Reference Kauanui2008b) compellingly argues that such settler-colonial laws erase and co-opt Indigenous land claims, and explicitly reject more inclusive Indigenous conceptions of their own Indigeneity. It is no wonder that Indigenous resistance to settler-colonialism has often meant an explicit rejection of the ethnoracial categories (blood quantum thresholds and all) sanctioned and enforced via settler-colonial laws, and an embrace of Indigenous identities predicated on genealogy and belonging. Hawaiian sovereignty activists reject “native Hawaiian” in favor of “kānaka maoli” and “kānaka ’Ōiwi,” just as CHamoru sovereignty proponents reject “Chamorro” in favor of “CHamoru” and “Chamoru.” Despite the ways in which these ethnoracial categories have been deployed in settler-colonial processes, and despite the heightened politics of ethnoracial identification among Indigenous populations, researchers continue to use these inherited categories.

Issue #3: addressing methodological biases in survey research

There are at least two salient potential sources of methodological biases in survey research on Indigenous populations, leading to skewed sample distributions and biased estimates: undersampling and lack of trust. While the effects of undersampling can be mitigated by advanced statistical techniques such as respondent-driven sampling (Heckathorn, Reference Heckathorn1997), political scientists typically address this problem through data aggregation. However, while this addresses the small n problem, it also comes with its own set of problems. Consider the treatment of the “Native Hawaiian” category: it is typically combined with other ethnoracial categories to form umbrella categories such as Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander (NHOPI) and Asian-American and/or Pacific Islander (AAPI). Yet, this solution inappropriately treats “Native Hawaiian” as just another ethnoracial category, when it is also deeply entangled with Indigenous kanaka relationships to land and ocean. Further, studies employing aggregated ethnoracial categories also provide limited insight on Native Hawaiians in particular. Large national representative surveys of Asian Americans often include Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders within their samples with the goal of being generalizable to the national Asian Pacific American demographics (Lien et al., Reference Lien, Margaret Conway, Lee and Wong2001; Ramakrishnan et al., Reference Ramakrishnan, Wong, Lee and Lee2016). While these large national surveys are valuable for understanding large AAPI subgroups, they are less useful for understanding smaller, geographically dispersed AAPI subgroups such as Pacific Islanders.

Beyond undersampling, a persistent lack of trust between Indigenous communities and non-Indigenous researchers (who disproportionately produce quantitative research on Indigenous communities) likely plays a key explanatory role here as well. Historically, non-Indigenous researchers were “often called upon to provide information and advice to the West in its efforts to manipulate and control the non-Western world” (Lewis, Reference Lewis1973, 582). This is generally true of social science research across the Pacific Islands (Wesley-Smith, Reference Wesley-Smith1995).

In a biting critique of haole (non-Indigenous outsider) scholarship, the legendary kanaka scholar-activist Haunani-Kay Trask powerfully summarizes some of the key sources of Indigenous distrust toward non-Indigenous researchers (Trask, Reference Trask1991). First, they reproduce inaccurate, racist portraits of Indigenous communities—what Foxworth and Boulding (Reference Foxworth and Boulding2021, this issue) begin to unpack in their work. Next, they reinforce the hegemony of non-Indigenous ways of knowing, while neglecting and delegitimizing Indigenous sources of knowledge. And finally, in imposing non-Indigenous ways of knowing upon Indigenous communities, they perpetuate colonial domination through defining the terms within which Indigenous communities define themselves and exercise power. In many ways, the strategies Trask observes are strikingly parallel to those studied by Dhamoon (Reference Dhamoon2016, this issue) in her analysis of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights.

These issues of trust might at least partly explain the staggering disparities that are often reported in studies of Indigenous public opinion. Consider the case of Native Hawaiian opposition to the construction of the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) on the traditional sacred site of Mauna Kea, the volcano with the highest peak in Hawaiʻi. In an influential 2019 poll in Civil Beat, an independent local news agency, it was widely reported that nearly six in 10 Native Hawaiians either “strongly support” or “somewhat support” the construction of TMT. At the same time, the 2019 Native Hawaiian Survey reported instead that almost nine in 10 Native Hawaiians oppose TMT (Phan, Reference Phan2020).

Admittedly, these disparities are not attributable solely to lack of trust, and are also attributable to other methodological challenges. On one hand, the Civil Beat poll was a representative sample of registered voters, yet Hawai‘i has famously low voter turnout (cf. the United States Elections Project), and data availability issues make it difficult to know more about how registered Native Hawaiian voters (who made up 12% of the sample) differ from unregistered Native Hawaiian voters, and how that might have skewed the results. On the other hand, the latter survey was an unrepresentative sample of the Native Hawaiian population, and thus suffers from similar issues.

Further, minimal research has been done to clarify the direction and extent of biases from undersampling and lack of trust in surveys of Indigenous populations. However, by briefly presenting discrepancies in Native Hawaiian attitudes among TMT surveys, and by invoking Indigenous critiques of settler academia, we hope to at least suggest that the lack of trust is certainly a cause for concern, and that it might be responsible for some of the stark disparities observed in quantitative studies of Indigenous public opinion.

The missing dimension of decoloniality in critical quantitative projects

Critical theory precisely seeks to interrogate the role of power and politics in our everyday lives, and there have been some notable attempts to blend critical theory with quantitative methods to forge “critical quantitative” projects. Such projects have proven productive and useful in addressing the role of power and politics in the data-generating process. However, they do not sufficiently attend to the challenges of colonialism, which requires centering Indigenous epistemologies and supporting Indigenous calls for decolonization.

Critical theory and quantitative methods

Critical theory boasts a storied genealogy: it might be historically traced back to late-18th century German thought (cf. Kant, Reference Kant1781; Hegel, Reference Hegel1807), which was invigorated by Marx, formalized by Adorno and Horkheimer, then made ubiquitous via the reception of 20th-century French thought (especially Foucault, Deleuze, Derrida). Brenner (Reference Brenner2009) helpfully distills four central propositions in critical theory that bear particular relevance for the social sciences: (1) it proposes a critique of instrumental reason; (2) it is reflexive; (3) it emphasizes the disjunction between the actual and the possible; and (4) it involves theoretical and conceptual abstractions from the empirical world. In short, critical theory starts from the premise that knowledge is socially constructed and produced through extant power relations. It then offers two central insights for contending with this relationship between power and knowledge. First, in exposing the contingencies of taken-for-granted forms of knowledge (i.e. ideology, in the Marxian parlance), we can begin to interrogate the influence that these forms of knowledge exercise over our everyday lives. And second, through this exercise of critical interrogation, we can begin to reject and/or transform the forms of knowledge used to constrict and oppress us (Boland, Reference Boland2014).

While critical theory has been readily integrated into qualitative methods, it has often had an uneasy relationship with quantitative methods. This holds true for several reasons: quantitative methods (especially the linear regression model, the quantitative social scientist's go-to method of choice) may oversimplify relationships between variables; often fail to recognize the role of structural oppression in constituting the formation of all variables; announce themselves as objective, and bias-free; and have historically been deployed for racist and/or colonial purposes (Sablan, Reference Sablan2019). Critical theory, however, precisely dismisses claims of objectivity as an ideological expression of power, and demands for us to interrogate, problematize, and uncover power asymmetries shaping the data-generating process.

Despite these challenges, multiple social science disciplines have made successful attempts to blend critical theory with quantitative methods—such as critical quantitative geography (Kwan, Reference Kwan2007; Kwan and Ding, Reference Kwan and Ding2008) and QuantCrit in educational research (Covarrubias et al., Reference Covarrubias, Nava, Lara, Burciaga, Vélez and Solorzano2018; Gillborn et al., Reference Gillborn, Warmington and Demack2018; López et al., Reference López, Erwin, Binder and Chavez2018). However, while these projects effectively interrogate the role of power and politics in shaping material inequalities along the social identities of race, class, and gender, they insufficiently tackle concerns of Indigeneity and the challenge of colonialism.

Decolonial methods

The social sciences are experiencing what might be identifiably called the “decolonial” turn (Grosfoguel, Reference Grosfoguel2007; Maldonado-Torres, Reference Maldonado-Torres2011). With long-standing critiques of the Anthropology's role in both sustaining colonialism and perpetuating racist stereotypes of Indigenous peoples (Asad, Reference Asad, Huizer and Mannheim1979), scholars since the 1990s have spoken of multi-sited and global ethnographies to draw attention to the circulation of geographically specific articulations of knowledge and power (Kearney, Reference Kearney1995; Marcus, Reference Marcus1995; Tsing, Reference Tsing2000). In Political Science, scholars speak of a comparative political theory (March, Reference March2009; von Vacano, Reference von Vacano2015), with the subfield's most innovative proponents offering new perspectives on the project of decolonization as such (Getachew, Reference Getachew2016).

The decolonial turn might be said to have four central premises: (1) Indigenous epistemologies, cultures, and values must form the basis of another way of knowing and understanding the world (Smith, Reference Smith1999); (2) colonialism is an ongoing process that perpetuates historical relations of domination and subordination—albeit in reconfigured, sometimes less explicit ways (Weiner, Reference Weiner2018); (3) universalisms must be replaced by a multiplicity of epistemologies, ontologies, ethics, and politics (Grosfoguel, Reference Grosfoguel2007; Maldonado-Torres, Reference Maldonado-Torres2011); (4) we must imagine and advance a just future beyond the strictures of Western imperialism, which mandates the global perpetuation of relations of domination and subordination (Mignolo, Reference Mignolo2009; Getachew, Reference Getachew2016). Thus, decolonial methods address questions of Indigeneity and decolonization, where past critical quantitative projects have not. Bringing its insights to bear on past critical quantitative projects, we propose a preliminary model of a decolonial quantitative political science, which interrogates the role of power, politics, and colonialism in the data-generating process.

Towards a decolonial quantitative political science

Our proposed methodological framework for a decolonial quantitative political science involves two primary elements. First, we center kanaka maoli epistemology in our interpretation of our findings, grounding our methodological framework in the four key principles animating the interdisciplinary field of Hawaiian Studies. Second, to align ourselves with these kanaka principles, we incorporated participatory methods at all stages of the research process through holding community forums and ongoing consultation with kupuna (elders) and Native Hawaiian undergraduate research assistants. Through these strategies, we co-developed appropriate survey questions, leveraged social networks to build trust with and gain access to Native Hawaiian communities, and maintained informal but ongoing processes of accountability to the Native Hawaiian research team members.

Centering kanaka maoli epistemology

Drawing from kanaka scholarship,Footnote 7 we engaged with kanaka maoli epistemology in two primary ways. First, we developed our hypotheses based on the theoretical claims offered in these writings. In kanaka epistemology, ʻmoʻokū‘auhau (genealogy) and ea (sovereignty) are deeply connected. In her monograph The Power of the Steel-Tipped Pen, Noenoe K. Silva (Reference Silva2017) provides a clear theory of why and how this is so: through mo'olelo (stories), kupuna transmit to their descendants an understanding of Hawai‘i's fraught history of colonialism and resistance, cultivating a clear moʻokū‘auhau (which Silva translates as genealogical consciousness), which grounds kānaka maoli in their own cultural and national identity, and resistance against U.S. settler-colonial domination. Similarly, Kauanui (Reference Kauanui2008b) emphasizes that ʻmoʻokū‘auhau is a form of world-enlargement—a practice that rejects the colonial boundaries of the Westphalian nation-state and the exclusionary formulations of race and ethnicity, and that instead affirms kānaka maoli in relation to their ancestral connection to their ʻāina (land).

In this study, we translated these theoretical insights into empirically testable hypotheses about Native Hawaiian identity. More specifically, we interpreted Silva and Kauanui as making a theoretical claim about the relationship between Native Hawaiian identity and national identity: different Native Hawaiian identities reflect different degrees of connectedness to moʻokū‘auhau (genealogical consciousness), and thus different degrees of connectedness to ea (Hawaiian sovereignty) and to national identity (i.e. Hawai‘i or the United States). This offers one clear example of how researchers might translate Indigenous epistemologies into formal hypotheses. That said, future research must also consider the complex politics of translation, to ensure that these acts are also ethically grounded in relational accountability to Indigenous populations.

Second, we took steps to ensure that our project was ethically guided by the “methodological ropes for research and resurgence” outlined by kanaka maoli scholar-activist Noelani Goodyear-Ka’ōpua (2016). In this framework, she outlines four principles that characterize contemporary research in the interdisciplinary field of Hawaiian Studies—including lāhui (collective identity), ea (sovereignty), kuleana (responsibility), and pono (harmony and balance).

Broadly, these four principles demand that researchers practice relational accountability to kānaka maoli, through centering kanaka worldviews and kanaka needs. The principle of lāhui invites researchers to ask themselves whether they are actively allowing kānaka maoli to define themselves and articulate their experiences on their own terms. Ea prompts researchers to center the lived experiences of kānaka maoli, and to actively support their self-determination. Kuleana probes for the political stakes of research, while pono emphasizes the importance of ensuring that research serves to benefit kānaka maoli and maintain balance with the ʻāina (land).

Participatory methods

Following Goodyear-Ka‘ōpua's call for relational accountability to kānaka maoli, we incorporated participatory methods at all stages of the research process—including research design, data collection, analysis, and dissemination. The Principal Investigator (PI) of the 2019 Native Hawaiian Survey began this project by exercising her kuleana to learn more about the people on whose lands she is a settler. To this end, she connected with kupuna through her home institution and consulted with them to discuss using her statistical skills to support Native Hawaiian sovereignty. This approach offered members of the lāhui opportunities to provide feedback on survey design, and to propose a broader range of ethnoracial self-identifications in the survey.

Participatory methods were also used in the data collection process. Given the long history of surveys used as tools of Indigenous dispossession, many Native Hawaiians are rightfully suspicious of surveys. With the vouching of kupuna and the labor of Native Hawaiian undergraduate research assistants distributing surveys in selected public spaces, the research team was able to build trust and legitimacy within Native Hawaiian communities, such that Native Hawaiians would be willing to participate in the survey at all. These research assistants were recognized as intellectual partners, with their labor valued through compensation, travel and lodging funding, co-authorship and mentorship opportunities.

Finally, participatory methods were incorporated into the data analysis and dissemination process. This involved continued transparency and open engagement with kupuna and undergraduate research assistants—ongoing opportunities to provide feedback on the study, and periodic updates on analysis and publications. The tight-knit, grassroots character of the project helped to cultivate a culture of openness and trust within the research team and to check that everything was pono (with harmony and balance) within the research team, thereby providing some accountability to the lāhui.

This decolonial quantitative political science methodological framework is very much aligned with the methodological framework outlined by kanaka public health scholars, who similarly center kanaka epistemology and incorporate participatory methods in their quantitative research (Mau et al., Reference Mau, Kaholokula, West, Leake, Efird, Rose, Palakiko, Yoshimura, Kekauoha and Gomes2010; Kaholokula et al., Reference Kaholokula, Look, Mabellos, Zhang, de Silva, Yoshimura, Solatorio, Wills, Seto and Sinclair2017; Reference Kaholokula, Ing, Look, Delafield and Sinclair2018; Ing et al., Reference Ing, Antonio, Ahn, Cassel, Dillard, Puni Kekauoha and Kaholokula2019; McElfish et al., Reference McElfish, Purvis, Esquivel, Sinclair, Townsend, Hawley, Haggard-Duff and Kaholokula2019; Antonio et al., Reference Antonio, Hishinuma, Ing, Hamagami, Dillard, Puni Kekauoha, Solatorio, Cassel, Braun and Kaholokula2020). For instance, Kaholokula et al. (Reference Kaholokula, Ing, Look, Delafield and Sinclair2018) empirically show how the PILI ‘Ohana Project and the KāHOLO project, respectively, reduced obesity and diabetes and systolic blood pressure among Native Hawaiians, precisely because these projects incorporated community participation and Indigenous cultural knowledge at every stage of the research process.

Ultimately, this methodological framework provides a preliminary model for how quantitative methods can interface productively with Indigenous epistemologies to produce research that actively supports Indigenous (and specifically Kanaka ‘Ōiwi) calls for decolonization of lands and ocean.

Sampling, variables, and hypotheses

The Native Hawaiian Survey was administered and disseminated online and in-person between August 1 and December 31, 2019. The survey team was comprised of the first author, a kupuna (Dr. Lynette Cruz), and undergraduate kanaka research assistants (La'akea Dedrick, Leilani DeLude, and Catherin Jara), who worked/studied full-time during the week and conducted recruitment activities during weekends. Respondents were primarily recruited through in-person outreach at Native Hawaiian events and spaces across the Hawaiian islands by the survey team, allowing respondents to participate in the survey if they were living in Hawai‘i and aged 18 or older. The survey team was based in O‘ahu but also traveled to the Island of Hawai‘i (commonly known as the Big Island) (7 days), Maui (4 days), and Kauai (3 days). Overall, the survey team used a combination of convenience and snowball sampling. On each island, the survey team recruited at public spaces, parks, beaches, shopping centers, schools, Hawaiian Homesteads, and invited research presentations. Survey participants were also encouraged to recruit their own contacts to complete the survey through social media (Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter). As part of the survey, respondents were also asked to provide contacts of other Native Hawaiians who might be interested in taking the survey; the survey team then contacted these respondents via phone.

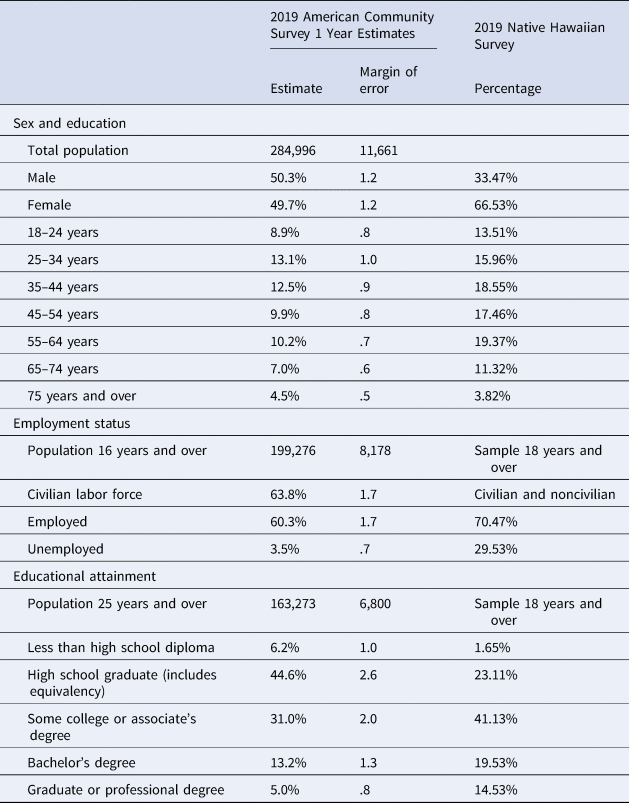

While the sample is not random or representative, it is—to our knowledge—the largest survey of Native Hawaiians to date focusing explicitly on identity and political attitudes toward decolonization. As Table 1 indicates below, the sample differed from 2019 ACS data in several ways: the sample skewed female, older, employed, and highly educated.

Table 1. Comparing demographic characteristics of 2019 Native Hawaiian Survey and 2019 ACS data

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2019 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates, Table S0201, released September 17, 2020.

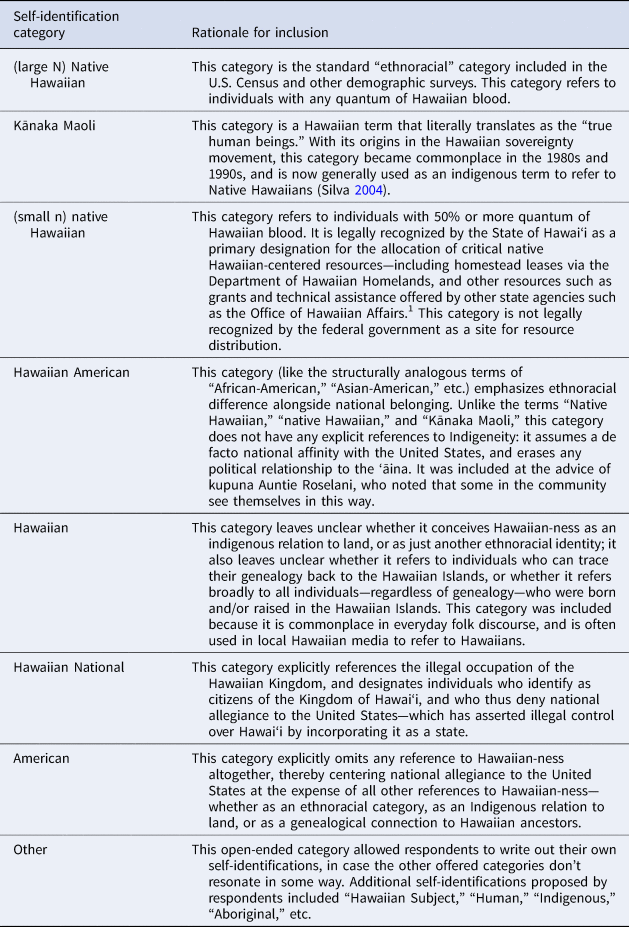

The main survey question analyzed in this study was worded as follows: “Do you self-identify with one or more of the following groups? Please check all that apply.” The paper survey presented options in two columns—the left column included “native Hawaiian,” “Kanaka Maoli,” “Native Hawaiian,” “Hawaiian American,” and “Other (Please specify),” while the right column included “Hawaiian,” “Hawaiian National,” and “American.” In the online survey, these options were randomized, with no differences found due to ordering effects. All these self-identification categories were included as binary variables in this descriptive study; “Yes” was coded as 1 and “No” was coded as 0.

The U.S. Census typically uses the self-identification category “Native Hawaiian,” while the State of Hawai'i uses the self-identification category “native Hawaiian” to denote those with 50% or more quantum of Hawaiian blood. For this survey, after consultation with kupuna and community members, the survey team incorporated a broader set of self-identification categories, as indicated above. The survey team's rationales for their inclusion are outlined below in Table 2.

Table 2. List of self-identification variables in 2019 Native Hawaiian Survey

Above and beyond the homestead leases, there are so many examples of resources that are limited to those with established 50% Hawaiian blood quantum—including grants and scholarships administered by the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. For more information, see https://www.oha.org.

Source: Authors' compilation.

Drawing from the aforementioned kanaka scholarship elaborating on the relationship between Native Hawaiian identity and national identity, we articulate three hypotheses about how Native Hawaiian identity might be analytically sorted into three identity clusters: (1) Hawaiian Sovereignty; (2) American; and (3) Hawaiian. These different clusters are useful in beginning to capture the different dimensions and overlapping identities that resonate among Native Hawaiians.

The first hypothesis (H1) pertains to the Hawaiian Sovereignty cluster, which includes “Hawaiian National” and “Kānaka”—the two self-identification categories most resonant with Hawaiian national identity. We expect to find a positive correlation between those that identify with these two categories. The second hypothesis (H2) pertains to the American cluster, which includes “American” and “Hawaiian American”—the two self-identification categories most resonant with American national identity. We expect to find a positive correlation between those that identify with these two categories. The third hypothesis (H3) pertains to the much more inclusive “Hawaiian” cluster, which includes “Hawaiian,” “native Hawaiian,” and “Native Hawaiian”—self-identification categories that are not explicitly resonant with American or Hawaiian national identity. We expect to find a positive correlation between those that identify with these three categories.

Findings

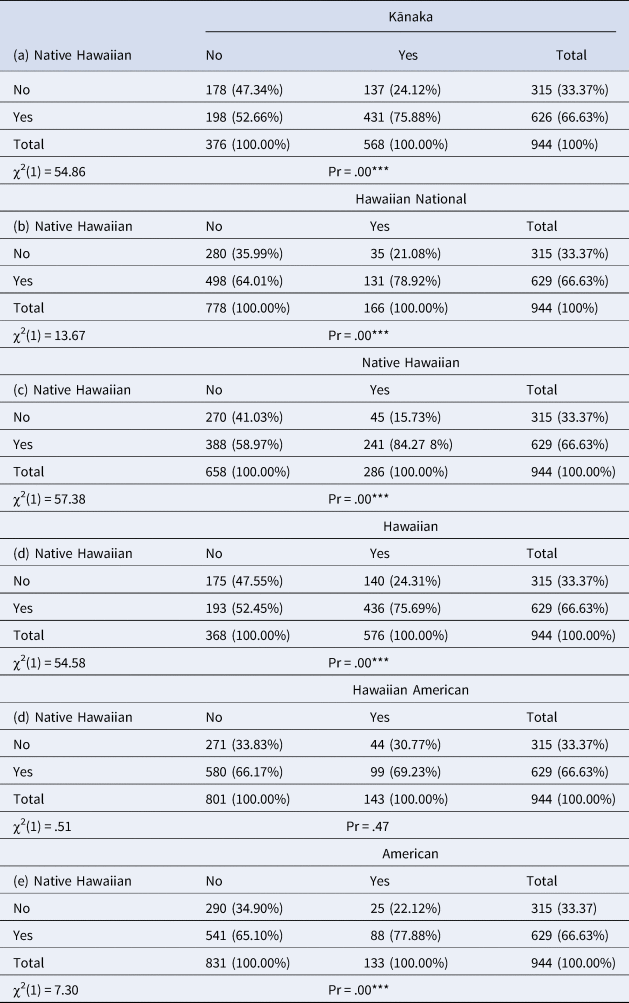

Through deploying our decolonial quantitative political science framework in the 2019 Native Hawaiian Survey, our descriptive analysis of respondents' self-identification yields three empirical contributions. Consistent with H1, respondents who self-identified as “Hawaiian National” were more likely to self-identify as “Kānaka” and less likely to self-identify as “American,” suggesting shared affinities with Hawaiian national identity and weaker affinities with American national identity. Consistent with H2, respondents who self-identified as “American” were more likely to self-identify as “Hawaiian American,” suggesting shared affinities with American national identity. However, we found mixed support for H3. While respondents who self-identified as “Native Hawaiian” were more likely to identify as “Hawaiian” and “native Hawaiian,” we also found that “Kānaka” (but not “Hawaiian National”) and “American” (but not “Hawaiian American”) are also statistically significant predictors of “Native Hawaiian.”

On heterogeneity of self-identification among Native Hawaiians

We found remarkable heterogeneities of self-identification within the broader Native Hawaiian community (defined as all respondents who indicated that they have Native Hawaiian ancestry). Table 3 below ranks, in descending order, the most common self-identifications of our respondents.

Table 3. Ranking of respondent self-identification

Q3a–3h. How do you self-identify with one or more of these groups? Please check all that apply.

Source: Authors' calculations, 2019 Native Hawaiian Survey, N = 944.

The category “Native Hawaiian”—the standard Census and demographic category—was the most popular self-identification category, with two-thirds of respondents checking “Yes.” A comparable share of respondents identified with “Hawaiian” (61.0%) and “Kānaka” (60.17%). A remarkably smaller share of respondents identified as “native Hawaiian”—the legal designation by which the State of Hawai‘i allocates resources to individuals with 50% or more Hawaiian blood quantum—suggesting that there might be a disconnection between how respondents self-identify (all of whom report having Hawaiian ancestry) and the identity ascribed to them by the settler-colonial ethnoracial classification system of the State of Hawai‘i.

As outlined in Table 1, the categories of “Hawaiian-American” and “American” are distinguishable from the aforementioned categories (“Native Hawaiian,” “native Hawaiian,” and “Kānaka”) in that “Hawaiian-American” and “American” both allude to some national allegiance to America, with “Hawaiian-American” mirroring the self-identification of other minority ethnoracial subgroups such as African-American and Asian-American. A sizable minority of respondents identified with these categories as well, with approximately 15% of respondents identifying as “Hawaiian-American” and more than one in 10 respondents identifying as “American.” Table 4 below summarizes the broad relationships between the different self-identification categories.

Table 4. Correlation matrix for respondent self-identification

Source: Authors' calculations, 2019 Native Hawaiian Survey, N = 944.

We identify three main self-identification clusters among survey respondents, including what we term the (1) Hawaiian sovereignty cluster—comprised of “Hawaiian National” and “Kānaka”; (2) American cluster—comprised of “American” and “Hawaiian-American”; and (3) Hawaiian cluster—comprised of “Hawaiian,” “native Hawaiian,” and “Native Hawaiian.” They are not necessarily mutually exclusive, and we do not provide in-depth analysis of their meaning and implications here. Our contribution is a narrowly defined one, only seeking to descriptively highlight how different self-identification clusters have different and complex affinities with American and Hawaiian national identities.

The Hawaiian sovereignty cluster

The Hawaiian sovereignty cluster comprises “Hawaiian National” and “Kānaka”—two self-identification categories that indicate the greatest shared affinities with Hawaiian national identity. Since respondents were allowed to select all that apply in their self-identification, many of them tended to select multiple identities. It is helpful to capture the extent to which there is overlap between identities in the various clusters. Among the 568 respondents identifying as “Kānaka,” more than a quarter of them (26.4%) also identified as “Hawaiian National.”

“Hawaiian National” is minimally correlated with “Native Hawaiian” (ρ = .12) and “Hawaiian American” (ρ = .11). “Kānaka” is negatively correlated with “American” (ρ = −.04), and strongly correlated with “native Hawaiian” (ρ = .28), “Native Hawaiian” (ρ = .24), and “Hawaiian” (ρ = .28). The tabular analysis in Table 4 also indicates that “Hawaiian National” is associated with “Kānaka” but not “American.” This connection between “Hawaiian National” and “Kānaka” is further supported by the logit regression below (in Table 5), which indicates that their relationship is statistically significant. When comparing two average respondents (i.e. with all other variables set at their means), the respondent identifying as Kanaka and not American is 26 percentage points more likely to identify as Hawaiian National, compared to the other respondent identifying as American and not Kanaka. Overall, we find support for H1, where respondents who self-identified as “Hawaiian National” were also more likely to self-identify as “Kānaka.”

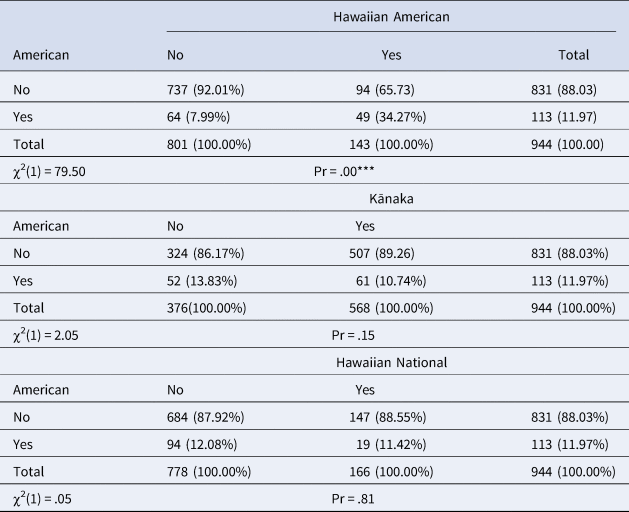

Table 5. Tabular analysis of “Hawaiian national” self-identification

Source: Authors' calculations, 2019 Native Hawaiian Survey. Note level of significance .05*, .01**, .00***.

The American cluster

The American cluster comprises “American” and “Hawaiian American”—two categories that suggest the greatest shared affinities with American national identity. Among the 113 respondents identifying as “American,” more than four in 10 (43.3%) of them also identified as “Hawaiian American.” The identities “American” and “Hawaiian American” are highly correlated (ρ = .29), a relationship found to be statistically significant by the logit regression in Table 6. Simple marginal effects indicate that respondents identifying as “Hawaiian American” are more likely to identify as “American,” and that this was particularly true for respondents who did not identify as “Hawaiian National.”

Table 6. Logistic regression models for Hawaiian clusters

Note level of significance .05*, .01**, .00***.

In the tabular analysis in Table 7, respondents who self-identified as “American” were also more likely to identify as “Hawaiian American,” but not “Kānaka” or “Hawaiian National”—findings echoed by the logit regression results presented above (in Table 6). Respondents who self-identified as “Hawaiian Americans” had a higher probability of also identifying as “American” (z = 8.16, p < .00). In contrast, respondents who self-identified as “Kānaka” or “Hawaiian National” are not more likely to identify as “American.” Overall, we find support for H2, where respondents who self-identified as “American” were also more likely to self-identify as “Hawaiian American.”

Table 7. Tabular analysis of “American” self-identification

Source: Authors' calculations, 2019 Native Hawaiian Survey.

Hawaiian cluster

The Hawaiian cluster comprises “Hawaiian,” “native Hawaiian,” and “Native Hawaiian”—three categories that are analytically positioned between the poles of the Hawaiian Sovereignty cluster on one end, and the American cluster on the other. As noted earlier, “Native Hawaiian”—the default category used in the Census and demography—proved the most popular self-identification category among survey respondents. Among the 629 respondents identifying as “Native Hawaiian,” three-quarters (75.9%) identified as “Kānaka,” four in 10 (78.9%) identified as “Hawaiian National,” two-fifths (38.3%) identified as “native Hawaiian,” and seven in 10 (69.3%) identified as “Hawaiian.” “Native Hawaiian” is generally correlated with all other self-identification categories in the broad Hawaiian cluster—“Hawaiian” (ρ = .24) and “native Hawaiian” (ρ = .24)—a finding echoed by the tabular analysis presented in Table 8.

Table 8. Tabular analysis of “Native Hawaiian” self-identification

Source: Authors' calculations, 2019 Native Hawaiian Survey. Note level of significance .05*, .01**, .00***.

However, additional analysis reveals that self-identification categories in the Hawaiian cluster have a complex and unexpected relationship with those in the other two clusters. Consistent with H3, tabular analysis in Table 8 indicates that “Native Hawaiian” is associated with “Hawaiian” and “native Hawaiian.” Unexpectedly, however, it also indicates that “Native Hawaiian” is associated with “Hawaiian National,” “Kānaka” (both of the Hawaiian Sovereignty cluster), and “American” (of the American cluster). These mixed results are further complicated by the logit regression results presented in Table 5.

We then calculated simple marginal effects. Setting all other variables at their means, we find that when an average respondent identifies as “Kānaka,” they are 75% more likely to also identify as “Native Hawaiian.” When an average respondent identifies as “Hawaiian,” they are 74% more likely to also identify as “Native Hawaiian.” And finally, those identifying as “American” are associated with an 80% increase in also identifying as “Native Hawaiian.” Consistent with H3, “native Hawaiian” and “Hawaiian” are both statistically significant predictors of “Native Hawaiian.” Inconsistent with H3, however, we additionally find that “Kānaka” (but not “Hawaiian National”) and “American” (but not “Hawaiian American”) are also statistically significant predictors of “Native Hawaiian.”

Discussion

During a 1993 event marking the centennial of the United States’ annexation of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Haunani-Kay Trask (Reference Trask, Carroll, McDougall and Nordstrom2015) stood overlooking a Native Hawaiian crowd with her fist in the air, declaring: “We are not American. We are not American. We are not American. Say it in your heart. Say it in your sleep. We are not American. We will die as Hawaiians.” Echoing the sentiments articulated in this well-known speech, kanaka scholars teach us that different degrees of connectedness to moʻokū‘auhau (genealogical consciousness) translate to different degrees of connectedness to ea (Hawaiian sovereignty) and national identity (i.e. Hawai‘i or the United States).

Our empirical findings are generally consistent with this theoretical claim. Indeed, respondents who self-identified as “Hawaiian National” were more likely to self-identify as “Kānaka” and less likely to self-identify as “American,” and respondents who self-identified as “American” were more likely to self-identify as “Hawaiian American.” Collectively, this suggests that identities in the Hawaiian Sovereignty cluster have shared affinities with Hawaiian national identity and weaker affinities with American national identity, and that identities in the American cluster have shared affinities with American national identity.

At the same time, the Hawaiian cluster—and specifically the self-identification of “Native Hawaiian”—yielded mixed results. It is analytically and substantively distinct from the Hawaiian Sovereignty cluster, in that the latter is avowedly not associated with “American,” while the former is. Likewise, the Hawaiian cluster is distinct from the American cluster, in that the latter is not more likely to be associated with both “Kānaka” and “Hawaiian National,” while the former is. While the Hawaiian cluster is distinct from the Hawaiian Sovereignty and American clusters, it may have a complex substantive relationship (and possibly some overlaps) with the other clusters. To peel back the social and political complexities of these clusters and their relationships, further study is needed.

To inform future quantitative research seeking to unpack the complex terrain of Indigenous politics, this study formally articulates minimum standards for how this could look like: grounding research in Indigenous epistemologies, elevating Indigenous voices and influence throughout the research process, and substantively investigating issues of Indigenous sovereignty, national identity, and self-determination. Importantly, the authors—who are both settlers (i.e. non-Indigenous) in relation to Hawai‘i—believe that it is also the responsibility of settlers in particular to ensure that their work attempts to center the voices and epistemologies of the Indigenous populations they work with.

Central to this project is incorporating a range of self-identification categories that are more congruent with how Indigenous populations perceive themselves, and which avoid some of the trappings that have historically affected quantitative research on Indigenous populations. Currently, Native Hawaiians are only legible to the state via two ethnoracial categories: national survey instruments such as the Census use “Native Hawaiian” (large N), while the State of Hawai‘i's uses “native Hawaiian” (small n).

However, this descriptive study shows that these default ethnoracial categories are sorely incomplete and problematic. Through presenting three self-identification clusters within the Native Hawaiian community, we show how Native Hawaiian identity is much more complex. In alignment with the long-standing theoretical insights of kanaka scholars, our findings suggest that Native Hawaiian attitudes toward genealogy, Hawaiian sovereignty, and national identity are profoundly intertwined, and are associated with different self-identifications. Our hope is that this contributes to Native Hawaiian sovereignty movements by empirically corroborating the ways in which “Native Hawaiian” as a monolithic ethnoracial category obscures the pluralistic character of Native Hawaiian identities, and more particularly, invisibilizes the ways in which Native Hawaiian identities are unevenly bound up with national identities. This indicates the continued vibrancy and strength of Native Hawaiian sovereignty movements, despite more than a century of ongoing U.S. colonialism.

Importantly, these empirical findings are not intended to cast normative judgments on the validity of different self-identifications among Native Hawaiians. We merely show that Native Hawaiians identify in heterogeneous ways, and that their self-identifications seem to be associated with different sets of political attitudes. Further, we show that these findings become available when researchers adopt a decolonial methodological framework—a framework that can be readily applied to quantitative research on other Indigenous populations. In practice, this means that quantitative researchers must (1) plant themselves in the scholarship and practice of the specific Indigenous populations they are working with; (2) center Indigenous epistemologies in the formulation of hypotheses and in the interpretation of results; and (3) develop research protocols that go well beyond the limited confines of consent per Institutional Review Boards, and that seek to develop ongoing relationships with and accountability to Indigenous communities.

Beyond its methodological contributions, this article's empirical study of the relationship between Native Hawaiian identity and national identity may have implications for our theoretical understanding of Indigenous identity and national identity writ large. Indigenous peoples are socially and culturally heterogeneous and are also subject to heterogeneous modes of state recognition and governance. What they share, however, is a shared context of Indigenous dispossession under settler-colonialism and colonialism, which likely produces disjunctions between their Indigenous identity and national identity. This complex relationship may have enormous implications for how we understand and analyze Indigenous politics but has hitherto been understudied by quantitative researchers.

To unpack this relationship, this article raises numerous empirical questions for further study. For instance, what are the factors shaping heterogeneities in self-identification among Native Hawaiians and among Indigenous populations more generally? What is the role of structure (especially settler-colonialism and historical legacies of colonialism more generally) and agency in shaping these self-identifications? What are the contents and implications of these different ethnoracial identities? Are these self-identifications predictive of certain Indigenous attitudes and behaviors pertaining to Indigenous sovereignty, national identity, and self-determination?

About the authors

Ngoc T. Phan (ntphan@hpu.edu) is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Hawai‘i Pacific University. Kevin Lujan Lee (kevinjl@mit.edu) is a doctoral candidate in urban planning and sociology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Appendix

Table A1. Racial and ethnic categories in the 2020 U.S. Census

Table A2. Selected definitions of Indigeneity via settler-colonial laws in the United States