IntroductionFootnote 1

Popular music curricula and programs are increasingly offered across a range of higher music education (HME)Footnote 2 contexts, existing alongside, emerging out of or designed independently of western art music programs (Carfoot et al., Reference CARFOOT, MILLARD, BENNETT, ALLAN, Dylan Smith, Moir, Brennan, Rambarran and Kirkman2017). Informal learning within small groups is central to the pedagogies of popular music practice (Green, Reference GREEN2001; Folkestad, Reference FOLKESTAD2006; Lebler, Reference LEBLER2007; Gaunt, Reference GAUNT, Rink, Gaunt and Williamon2017; Smart & Green, Reference SMART, GREEN, Rink, Gaunt and Williamon2017). Using Wenger, Trayner and de Laat’s (Reference WENGER, TRAYNER and DE LAAT2011) framework for Promoting and assessing value creation in communities and networks, this article explores the value of collaborative learning within first year heterogeneous student groups in a popular music program. Within this framework, ‘value’ means ‘the value of the learning enabled by community involvement’ (Wenger et al., Reference WENGER, TRAYNER and DE LAAT2011, p. 7).

Collaborative learning for popular music practice and performance draws on informal learning processes ranging from the garage band (Westerlund, Reference WESTERLUND2006) through to the practices of professional popular musicians (e.g. Virkkula, Reference VIRKKULA2016a). When collaborative learning is used for music practice and performance, masters and apprentices become co-constructors of learning (Lave & Wenger, Reference LAVE and WENGER1991; Lebler, Reference LEBLER2007; Hanley, Baker, & Pavlidis, Reference HANLEY, BAKER and PAVLIDIS2018). These informal group practices contrast with those of the conservatoire, where one-to-one tuition is the predominant educational model for music practice and performance (Bjøntegaard, Reference BJØNTEGAARD2015; Carey & Grant, Reference CAREY and GRANT2015; Virkkula, Reference VIRKKULA2016b; Gaunt, Reference GAUNT, Rink, Gaunt and Williamon2017). Informal pedagogies within communities of practice have much to recommend themselves in arts education (Virkkula, Reference VIRKKULA2016a), and more specifically, it is argued in this paper, within HME (see also Westerlund & Partti, Reference WESTERLUND, PARTTI and Brown2012). This article explores some of the ways in which collaborative learning might broadly inform pedagogies of music practice within HME (see also Hanken, Reference HANKEN2016).

Despite the prominence of social learning theories within education, HME has been slow to adopt sociocultural learning models like collaborative learning (Gaunt & Westerlund, Reference GAUNT, WESTERLUND, Gaunt and Westerlund2013b). This is perhaps due to the predominance of the one-to-one model (see Hanken, Reference HANKEN2016) and the relatively recent emergence of popular music practice in HME. However, the publication of Collaborative Learning in Higher Music Education (Reference CHRISTOPHERSEN, Gaunt and Westerlund2013) edited by Gaunt and Westerlund demonstrates that momentum in this area is gaining pace, with numerous recent studies in HME exploring sociocultural learning approaches (e.g. Ilomaki, Reference ILOMAKI, Gaunt and Westerlund2013; Kenny, Reference KENNY2014; Rikandi, Reference RIKANDI, Gaunt and Westerlund2013; Latukefu & Verenikina, Reference LATUKEFU, VERENIKINA, Gaunt and Westerlund2013; Hanken, Reference HANKEN2016). A number of these studies investigate the masterclass environment, or instrumentally homogenous student groups such as singers and pianists. Virkkula (Reference VIRKKULA2016a, Reference VIRKKULA2016b) examined communities of practice for jazz and popular music workshops within Finnish conservatories, which cater to the upper secondary, vocational level of music education (Music in Finland, 2017). Creech and Hallam (Reference CREECH, HALLAM, Rink, Gaunt and Williamon2017) discussed the facilitation of musical learning in small groups but noted that there is little research on ‘promoting creativity and collaborative approaches’ in small music groups (p. 72). Within HME, there is a paucity of research which explores sociocultural learning models for instrumentally heterogeneous small student groups.

The music major at the study site is a series model of popular music education which replaced the conservatoire model – the series model emerged out of changing institutional processes and priorities, and social and cultural shifts, as well as new faculty with expertise in popular musics (Carfoot et al., Reference CARFOOT, MILLARD, BENNETT, ALLAN, Dylan Smith, Moir, Brennan, Rambarran and Kirkman2017). As Carfoot et al. note, the series model ‘is especially applicable in smaller or younger tertiary institutions where faculty have been forced or have chosen to implement changes in response to sustainability issues such as the need to attract students’ (p. 141). At the study site, the one-to-one model for western art music practice was replaced with a collaborative, small group model for first year popular music practice. This change was a response to a complex set of factors including the regional location of the institution, student presage, the need to cater to multi-disciplinary pathways within the degree program (Forbes, Reference VIRKKULA2016b) and a distinct shift within the student population towards a more participatory culture (see Westerlund & Partti, Reference WESTERLUND, PARTTI and Brown2012; Partti, Reference PARTTI2014).

This article responds to the research question, ‘In what ways did participation in collaborative learning for music practice and performance create value for student participants?’ The author was the teacher/researcher for the study, which sat within a practitioner inquiry framework (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, Reference COCHRAN-SMITH and LYTLE2009).

Wenger’s social theory of learning and collaborative learning

Building upon Deweyan educational psychology and philosophy, Vygotsky (Reference VYGOTSKY1978) and Lave and Wenger (Reference LAVE and WENGER1991) argue that learning is social and situated. Wenger’s (Reference WENGER1998) seminal theory of communities of practice further argued that learning is inherently social and is a result of social participation. Social participation involves both community practices and constructing identities within communities (Wenger, Reference WENGER1998). ‘Communities of practice’ exist as actual entities but the phrase is also an analytical tool which views learning through social participation constituted by belonging, doing, experiencing and becoming (Wenger, Reference WENGER1998).

Collaborative learning is an example of Wenger’s social theory of learning in practice – learning is viewed as a cultivation of communal goals and problem solving. Learning results from social participation, as distinct from occurring within individuals in isolation (Bruffee, Reference BRUFFEE1999; Wenger, Reference WENGER1998; Gaunt & Westerlund, Reference GAUNT, WESTERLUND, Gaunt and Westerlund2013b). Despite the many definitions of collaborative learning, one common view is that collaborative learning is more than merely learning in a group setting (Luce, Reference LUCE2001). Collaborative learning challenges the idea that the teacher holds exclusive authority over knowledge (Bruffee, Reference BRUFFEE1999). As distinct from transmission learning models – the transfer of knowledge from master to apprentice or expert to novice – collaborative learning requires a community of learners and teachers to construct knowledge together. Students vest trust and authority first in their own groups, and gradually (with increasing confidence and interdependence) in the class community, and ultimately, in themselves (Bruffee, Reference BRUFFEE1999). Valuing student contributions to learning and teaching is a central characteristic of collaborative learning (see e.g. Bjøntegaard, Reference BJØNTEGAARD2015). Both group responsibility and individual accountability are important aspects of collaborative learning (Adams & Hamm, Reference ADAMS and HAMM2019). Individual accountability arises when group members’ contributions are assessed against a standard and feedback provided (Johnson & Johnson, Reference JOHNSON and JOHNSON2017). At the study site, in addition to ongoing informal feedback from peers and teachers, students’ individual accountability was formally peer and self-assessed twice during the academic year.

Students in this study were taught by a teaching team of two. The team possessed complimentary practical skills: the teacher/researcher was a contemporary vocalist and pianist, and the other team member was a multi-instrumentalist, songwriter and producer. The teaching team placed students strategically into groups of usually three to five students. These groups changed throughout the academic year to provide students with opportunities to learn from different peers in different instrumental settings. Groups were formed with heterogeneity in mind to optimise learning opportunities (Johnson & Johnson, Reference JOHNSON and JOHNSON2017). Factors taken into consideration (in addition to instrumentation) included age, gender, levels of ‘life experience’, personality traits (e.g. leader/follower, introverted/extroverted – these became more discernable to the teaching team as the year progressed).

Students participated in team-taught 2-h weekly workshops for all instrumentalists and vocalists (the workshops). Part of the workshop time was dedicated to groups presenting work in progress and receiving feedback from peers and teachers, and the remainder was dedicated to rehearsals for groups. The teaching team would float between rehearsing groups providing assistance as necessary. Due to the number of groups rehearsing at any one time, and because these groups regularly rehearsed outside official class time, some of this rehearsal time was conducted without a teacher present. Groups worked on focused, open-ended tasks (e.g. arranging songs for their particular instrumentation, chart writing, rehearsal and performance) which required negotiation, problem-solving and learning from each other (Bruffee, Reference BRUFFEE1999; Gaunt & Westerlund, Reference GAUNT, WESTERLUND, Gaunt and Westerlund2013b). Teachers created a learning environment conducive to collaboration (Gerlach, Reference GERLACH, Bosworth and Hamilton1994; Folkestad, Reference FOLKESTAD2006) by balancing teaching interventions with allowing students to find their own solutions to problems. Direct teacher intervention was used as a last resort. Group conflicts sometimes required such intervention when disagreements about rehearsals, schedules or artistic decisions could not be resolved peer to peer. Practically speaking, students who were experiencing difficulties with their instrument/voice sometimes required teacher assistance where the level of expertise required was beyond group members. For a detailed discussion of practical strategies for facilitating small music groups, see Creech and Hallam (Reference CREECH, HALLAM, Rink, Gaunt and Williamon2017).

Value creation framework

Wenger, Trayner, and de Laat’s (Reference WENGER, TRAYNER and DE LAAT2011) framework for Promoting and assessing value creation in communities and networks (the VCF) is both a conceptual frame for understanding learning as social participation within communities and a research tool to collect and analyse data to evidence the learning which takes place in these communities. The VCF has been used in numerous contexts unrelated to music education (e.g. online teachers’ networks (Booth & Kellogg, Reference BOOTH and KELLOGG2014) and digital storytelling in a museum (Hanley, Baker, & Pavlidis, Reference HANLEY, BAKER and PAVLIDIS2016)). Whilst referred to in music education research as a conceptual frame (e.g. Rikandi, Reference RIKANDI2012; Gaunt & Westerlund, Reference GAUNT and WESTERLUND2013a; Partti & Westerlund, Reference PARTTI and WESTERLUND2013; Partti, Westerlund, & Lebler, Reference PARTTI, WESTERLUND and LEBLER2015), the VCF has not previously been applied as a research tool in the HME context. The aim of applying the VCF to a learning community is to create a compelling, evidence-based picture of the learning which takes place (the ‘value’) and to promote this value to a wide range of stakeholders (Wenger et al., Reference WENGER, TRAYNER and DE LAAT2011).

The term ‘community’ in the VCF is shorthand for ‘community of practice’ which is defined as ‘a learning partnership among people who find it useful to learn from and with each other about a particular domain’ (Wenger et al., Reference WENGER, TRAYNER and DE LAAT2011, p. 9). The definition of ‘value’ as ‘the value of the learning enabled by community involvement’ (Wenger et al., Reference WENGER, TRAYNER and DE LAAT2011, p. 7) includes learners’ perceptions of value (Cajander et al., Reference CAJANDER, DANIELS and McDERMOTT2012). This paper focuses on students’ experiences of collaborative learning (Westerlund, Reference WESTERLUND2008; Karlsen, Reference KARLSEN2011) and does not assess the effectiveness of collaborative learning in relation to the acquisition of musical skills (cf King, Reference KING2008; Brandler & Peynircioglu, Reference BRANDLER and PEYNIRCIOGLU2015), except to the extent students’ perceptions revealed learning in this area.

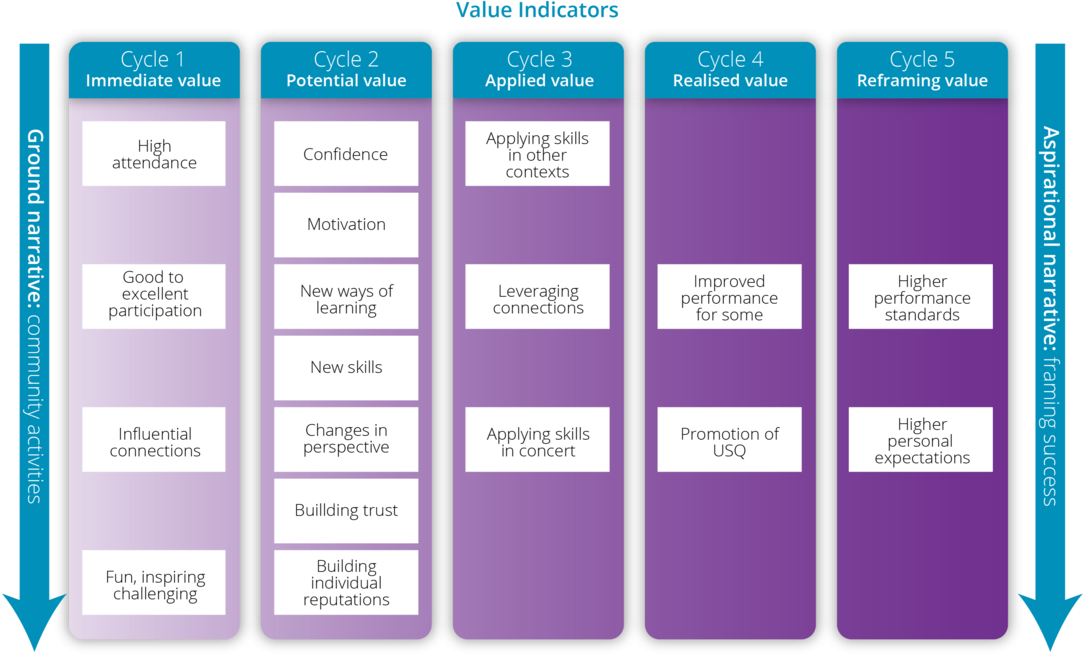

To understand the complexity of learning through social participation, the VCF identifies five value creation cycles: immediate, potential, applied, realised and reframing value (each cycle is discussed in more detail below in ‘Findings and discussion’). No cycle is more important than another, and there are complex relationships between cycles but not necessarily any ‘causal chain’ (Wenger et al., Reference WENGER, TRAYNER and DE LAAT2011, p. 21). Establishing value creation through cycles enables researchers to create a rich and detailed account of learning within communities.

Within the VCF, value indicators and value creation stories comprise two types of complementary data. Combining both types of data corroborates the evidence for value (Wenger et al., Reference WENGER, TRAYNER and DE LAAT2011). Value creation stories, which can be collective or individual, draw together and support value indicators by narratively tracing value creation through each cycle. The final assessment and promotion of the value of social learning are found in the relationship between value indicators, collective and individual stories and ground and aspirational narratives, resulting in a robust picture of value creation called a ‘value creation matrix’ (Wenger et al., Reference WENGER, TRAYNER and DE LAAT2011). This paper presents the evidence for value indicators at the study site. For an account which shows the interplay of indicators and collective and individual value creation stories, see Forbes (Reference FORBES2016a).

Method

Participants

Human ethics approval was obtained for this study. Proper management of the unequal relationship between the teacher/researcher and the student participant pool was fundamental to approval. This relationship was managed through critical reflection by the teacher/researcher, a non-exploitative and compassionate approach to the research (Berger, Reference BERGER2015) and strict adherence to the ethical principles of informed consent, respect, beneficence and justice.

The participant pool included students who completed two semesters (one academic year) in first year music practice. The participant pool for the study was N = 10. Gender was almost evenly balanced, and students were mostly in the 17–20 age bracket (n = 7) with some students aged 30+ (n = 3). Half the students were singers, with the remaining students on piano (n = 2), guitar (n = 1), drums (n = 1) and saxophone (n = 1). Pseudonyms for student participants are used in the reporting and discussion of results. Due to the small number of participants and the risk of identification, students will not be listed here alongside their principal instrument. It is important to note that students who cancelled their enrolment during the academic year were not included in the study. It is therefore not possible to know whether collaborative learning itself played a role in these students’ decisions to discontinue. This may be a question for future research (see also Christopherson, 2013).

Data collection and analysis

Data were gathered from student participants in accordance with the VCF in the form of short answer questionnaires administered three times throughout the academic year and via attendance and assessment records. The VCF (see Wenger et al., Reference WENGER, TRAYNER and DE LAAT2011, pp. 22–23) provided the basis for the questions in the short answer questionnaires (see Appendix). Questions suggested in the VCF were modified slightly to be ‘open’ questions which invited student reflection. These were administered at strategic points throughout the academic year during class to ensure students were in attendance. The use of class time was considered appropriate for completion of questionnaires as they required students to reflect on their learning. A decision was made to conflate questions for cycles 3, 4 and 5 into one questionnaire, to avoid student ‘questionnaire fatigue’ and to limit class time spent on answering questionnaires. All students in the study returned all questionnaires (although some students left some questions unanswered). Relevant sections from Preparing For Success: A Practical Guide for Young Musicians (Hallam & Gaunt, Reference HALLAM and GAUNT2012) were used as a guide for students to ensure responses were based on an informed understanding of the nature of working in small groups in music practice.

Student answers were handwritten and later transcribed by the teacher/researcher into Word and imported into NVIVO, a qualitative data analysis software program. Data relating to each cycle were collated so that an overall response for each cycle could be viewed and analysed. Value indicators from the VCF were used as an a priori coding scheme (see also Booth & Kellogg, Reference BOOTH and KELLOGG2014). Data were crafted into chronological narratives through a process of ‘restorying’ (a simple form of narrative analysis) (Creswell, Reference CRESWELL2013; Booth & Kellogg, Reference BOOTH and KELLOGG2014). Thematic analysis (a paradigmatic narrative approach – Polkinghorne, Reference POLKINGHORNE1995) then established the value indicators present within the questionnaire data. The co-teacher from both semesters was used as a credibility checker of the data analysis (Creswell, Reference CRESWELL2013).

Findings and discussion

As the VCF provides for value to be tracked across cycles (Wenger et al., Reference WENGER, TRAYNER and DE LAAT2011), results are reported for each cycle: immediate, potential, applied, realised and reframing value.

Cycle 1: Immediate value – participating, connecting and being challenged

Cycle 1 value indicators are community activities and interactions which have value ‘in and of themselves’ (Wenger et al., Reference WENGER, TRAYNER and DE LAAT2011, p. 19), such as excellent attendance and high levels of participation both in class and beyond (e.g. unsupervised rehearsals). Class attendance levels were high (improving from 75% in semester 1 to 100% in most weeks in semester 2). Students’ comments described the level of class participation as good (Jack, Shane, Mark), very good (John), excellent (Tamika, Maddie), great (Hope) and fantastic (Gemma):

Overall I felt the whole group participated well and mostly sorted through logistical and personality issues. (Cate)

The participation in the group classes was really good, everyone was engaged with the activity and perhaps only when the activity lulled people started to get distracted. (Jane)

Students also rated participation in rehearsals outside of class time mostly positively – ‘Some of our practice times went for 4–6 h!’ (Gemma) – despite numerous scheduling issues. These extra-curricular rehearsals were not mandated and, together with high class attendance and strong participation levels, indicate that students found group membership and participation inherently valuable (Wenger et al., Reference WENGER, TRAYNER and DE LAAT2011).

Social connections also have inherent value (Wenger et al., Reference WENGER, TRAYNER and DE LAAT2011) and all students reported connecting with peers as influential on their learning, for example:

Maddie helped me harmonise…She has really opened up my eyes about music and has helped me a lot! (Gemma)

Cate’s experience as a practicing musician has showed in our rehearsal and it’s taught me to look at music differently. She’s inspired me with her talent and feel for it…(Jane)

Students experienced community participation as fun, inspiring and enjoyable due to the interaction with peers:

It was fun being able to be around nice and musically talented people and we can all have a laugh at each other without feeling judged. It’s inspired me to just become a better person and musician so I can collaborate with more people. (Hope)

I just love sharing my passion with so many other people that feel the same way, which is also inspiring. I think that seeing the talent in other groups inspired me to become as good as them also. (Maddie).

These examples demonstrate that leveraging each other’s strengths was particularly valuable and enjoyable.

All students except Tamika felt challenged by their participation. Specific challenges included:

1. lack of experience in group work: ‘It was maybe slightly hard at first to adjust since I hadn’t worked with many people before in this way’. (John)

2. negotiating different levels of ability and knowledge: ‘[I found it challenging] that the musicianship was high and others could recall ideas very well’. (Mark)

3. scheduling difficulties: ‘Time availability was also quite challenging but we tried our best!’ (Maddie)

4. students dropping out of the courses: ‘In the end it was a challenge to overcome losing an ensemble member and having to rework our songs’. (Jane)

5. unfamiliarity with repertoire/musical styles: ‘It was challenging for me as I played mainly classical music and had no idea really how to work with other musicians playing contemporary music’. (Hope)

6. applying theory to practice: ‘I’ve never had to talk in music terms. It’s one thing to read a book and know some theory. Another is to know it well enough to converse with others’. (Shane)

Challenges have been included in cycle 1 despite not being noted within the VCF. Students identified challenges as an important learning opportunity, and their inclusion presents a more balanced view of value.

Cycle 2: Potential value – changes in perspective, new skills, social relationships as a learning resource and access to new learning experiences

Not all value creation is immediate – the community can create knowledge capital which has the potential for future realisation (Wenger et al., Reference WENGER, TRAYNER and DE LAAT2011). Knowledge capital has various forms: human capital, social capital, tangible capital, reputational capital and learning capital (Wenger et al., Reference WENGER, TRAYNER and DE LAAT2011). The data did not reveal any evidence that tangible capital was created (in the form of access to new, tangible resources), nor did it reveal that students experienced the collective reputational capital of the learning community. However, the following discussion presents the evidence for the creation of knowledge capital in the form of human, social and learning capital.

Potential value was created in the form of human capital or personal assets, namely, the ways in which participation in collaborative learning changed students. For example, increased confidence and motivation are personal assets which have both immediate and potential future value for participants. Students experienced increased confidence, for example:

I am more open because of this class…I honestly think with this class I will just keep improving as a performer, singer and a person. (Gemma)

My confidence has massively grown in my performance as the feedback I received was consistent and the frequent performances have helped me to put that feedback to use. (Jane).

The fun, inspiring experiences created in cycle 1 also have potential value, in that they can serve as motivators for future action. Students commented that working with others motivated them to work harder generally, or to focus on improving specific skills such as ear training or chart writing (putting theory into practice). Students explored new ways of learning and acquired new skills:

Working with musicians with good ears in and out of the group inspires and motivates me to train my ears daily. (Shane)

I am inspired by other students who are musical as well as technically confident. They inspire me to work towards theoretical and technical literacy. (Cate).

The acquisition of new skills grows students’ personal assets. These skills can be used both immediately and into the future, either within or beyond the learning community. Some examples of new skills identified by students include compromising with group members and playing by ear (Tamika); listening to and following the group (Hope); musical versatility (Mark, Jack); [group] mediation skills, general musical knowledge and performance confidence (Shane); how to receive constructive criticism (Gemma); creating a lead sheet (Cate) and communicating musical ideas (Jane).

A change in perspective further builds the personal assets of participants. All students experienced a change in perspective. For example, where Cate had previously shied away from music theory, she reflected that ‘I really love the way theory is helping my music practice’. Shane observed that

…not everyone is committed as I am. Which is okay. I’ve always thought commitment = good person. But I think I’m wiser in that regard.

Some students realised that to succeed, they needed to make a deeper commitment to learning:

[I] got a reality check on how much I have to apply myself to be successful in music. (Maddie)

Music is hard. Real hard! (Shane)

Changes in perspective build students’ personal assets and hold current and future value within and beyond the learning community.

Knowledge capital is created in the form of social capital where participation changes social relationships (Wenger et al., Reference WENGER, TRAYNER and DE LAAT2011). As social relationships formed and consolidated, students felt less isolated, trust increased and they knew who to turn to in the learning community for help and advice, be that peers or teachers:

Because of this class, I now have a huge group of musicians to come to and learn from and I’m surprised how tight the friendships are…I trust them and it gives me confidence knowing I have people to help me and that are in the same position as me. (Maddie)

Working with the lecturers has shown me the extent of their skills and knowledge and having gone through a few difficulties they’ve proven they’re there to support us/me. (Jane)

Individual reputations are another form of social capital with the potential to be leveraged in the future. Students demonstrated an awareness of the double-edged sword of reputation, which may affect opportunities for future collaborations. Whilst Jane felt she was gaining a positive reputation –

I seem to be becoming characterized by the fact I’ve had to fill in a lot of gaps when I’ve lost some members of my ensemble (Jane)

– others were aware that they were gaining a reputation as being somewhat unreliable (Tamika) or troublesome (Mark) which may limit future opportunities. Reputation as a form of social capital was therefore understood by students as being of their own making, which fostered individual accountability.

Learning capital is formed when participants experience new ways of learning. For example, students from formal learning backgrounds (Hope and Jane) experienced collaborative learning as very different. Jane found working with peers to create a performance from a lead sheet (compiled by students) very different to being given a notated part to play by a teacher. Most students experienced this style of learning as ‘a lot more personal’ (Mark) than their previous experiences. It is interesting to observe that students experienced collaborative learning in groups as personal learning given one-to-one learning and teaching is perhaps seen as the ultimate personalised pedagogical environment. Students found there were new opportunities for learning which they had not previously experienced or recognised, such as ‘collaborating with others’ and ‘creating music without a set score’ (Jane) and ‘watching people play their instruments or sing’ (Gemma).

Cycle 3: Applied value – impacts beyond the learning community

When students leveraged knowledge capital, they created applied value in the form of changes in practice. Applied value is indicated by leveraging community relationships to achieve something beyond the community or by applying skills acquired within the community in other contexts. The most obvious application of new skills (interpersonal and musical) came in the performance of two concerts during the academic year for the university community. All students experienced applied value through concert participation and some noted that they applied skills learned in the community in their workplaces (confidence, communication, voicing opinions, problem solving):

This class has boosted my confidence and affected my personality at uni, home, work and everywhere else I go. (Maddie)

[I’ve applied these skills in] everyday life. I used to maybe be a bit of a loner, but now I communicate better as a result of working with others. (John)

Half the students leveraged community relationships to achieve something beyond the community through new collaborations (Jack, Shane), studio teaching (Hope) and working in schools (Jane, Cate).

Cycle 4: Realised value – improved performance

Indicators of value within this cycle must demonstrate more than simply improved performance – they must show that the application of knowledge capital has impacted on achieving ‘what matters to stakeholders’ (Wenger et al., Reference WENGER, TRAYNER and DE LAAT2011, p. 21). Unfortunately, questions for this cycle did not elicit explicit reflection from students on what mattered to them. Data interpretation is therefore based on an assumption that improving music practice mattered to students, given they were enrolled in the courses. The student achievement data (based on assessment) showed improved performance for 60% of the class over two semesters. There is evidence in cycle 2 that students experienced a deeper understanding of what matters to them in their learning through changes in perspective and realisations of what aspects of practice are important. On this basis, value was realised through improved performance in areas which were important to students.

Whilst this paper focuses on value for student participants, the VCF also enables researchers to view improved performance from the perspective of non-participant stakeholders, such as the institution itself (Wenger et al., Reference WENGER, TRAYNER and DE LAAT2011). The data revealed that numerous students were actively and positively promoting the learning community and the university to others:

I promote the music program to people I come across in daily life because I really believe in the value of this program. (Cate)

I have provided positive feedback about the quality of this university and this course and have helped shape peoples’ decisions about their future with [the university] and helped them with their auditions. (Jack)

These activities created realised value for the university through building institutional reputational capital.

Cycle 5: Reframing value – increased performance standards and personal expectations

Reframing value is created when ‘social learning causes a reconsideration of the learning imperatives and the criteria by which success is defined’ (Wenger et al., Reference WENGER, TRAYNER and DE LAAT2011 p. 21). Importantly, this change can occur at the individual, community or institutional levels. Students redefined their criteria of a successful music performance. This was most evident in their comparison of the two end of semester concerts. Reflecting over the year, Shane said the first semester concert was not ‘of performance ready standard’ and Tamika recognised that ‘compared to how we are sounding now last semester’s [concert] will look weak’. Experiencing an improvement in performance standards meant students reframed the criteria for a successful performance both individually and collectively. As Mark noted, students were not previously able to ‘recognise…weaknesses and bad habits’.

Value indicators summary

Figure 1 (adapted from Wenger et al., Reference WENGER, TRAYNER and DE LAAT2011) displays value indicators across cycles. There was strong value indication for cycles 1 through 3, less so for cycles 4 and 5. Almost every value indicator is associated with the influence of peer-to-peer learning on value creation for students.

Figure 1. Value indicators for the learning community.

Limitations and conclusion

Given the subjective nature of experience, it is acknowledged that another student cohort may experience collaborative learning differently. This study was undertaken within a particular context (regional university, first-year students in a popular music program, small cohort of students). The results will not be generalisable; however, they may be relevant to similar educational contexts. It is also worth reiterating that students who discontinued their study may have had negative experiences of collaborative learning. Further, the learning community in this study was small, with a student to teacher ratio of 5:1 (once enrolments stablised). This intimate learning environment may have had a bearing on the largely positive results of students’ experiences of collaborative learning.

Students’ experiences across value creation cycles provide evidence of the ways in which they learned collaboratively. Peer-to-peer learning created a sense of collective belonging, doing and experiencing for students (Wenger, Reference WENGER1998). On an individual level, evidence of the final cycle of value creation (reframing value) meant students experienced ‘becoming’ (Wenger, Reference WENGER1998) in that they formulated new musical and personal expectations of themselves. Thus, value indicators evidenced individual accountability through a deepening understanding of the role individuals play in both individual and group success.

The learning community discussed here leveraged the ‘storehouse of knowledge’ (Luce, Reference LUCE2001, p. 21) which students bring to any learning environment. This has not traditionally been a feature of HME (Hanken, Reference HANKEN2016). According to Willingham and Carruthers (Reference WILLINGHAM, CARRUTHERS, Higgins and Bartleet2018), HME has had to ‘rethink everything’ in recent years – issues of ‘relevance and inclusivity’ are now central to academe (p. 595). Certainly, Australian HME has undergone sweeping changes, with rolling government reforms over recent decades completely redesigning the higher education landscape more broadly (Forbes, Reference FORBES2016b). Collaborative learning at the study site – with peer learning at its core – was used to respond ‘creatively and constructively’ (Gaunt & Westerlund, Reference GAUNT, WESTERLUND, Gaunt and Westerlund2013b, p. 3) to some of the many institutional, systemic and cultural challenges facing HME (Daniel, Reference DANIEL2001; Caruthers, Reference CARRUTHERS2008; Gaunt, Reference GAUNT, Gaunt and Westerlund2013; Sloboda, Reference SLOBODA2011; Gaunt & Westerlund, Reference GAUNT, WESTERLUND, Gaunt and Westerlund2013b; Willingham & Carruthers, Reference WILLINGHAM, CARRUTHERS, Higgins and Bartleet2018). That students experienced collaborative learning as valuable in this context demonstrates that the change in HME does not always have to mean compromise. Students’ largely positive experiences of collaborative learning for music practice in this study are offered for consideration by higher music educators, including those in conservatoires and larger metropolitan institutions.

Appendix Questionnaires for students based on Wenger, Trayner and de Laat (Reference WENGER, TRAYNER and DE LAAT2011)

Cycle 1 Semester 1 (June)

The following questions relate to the group class time of 9–11 am on Wednesdays and your work within your ensemble group. The experiences you reflect on may be either positive or negative.

1. From your own observations, how would you describe the level of participation in the group workshops and ensemble rehearsals (during the time 9–11 am on Wednesday)?

2. Did your group rehearse outside class time? If so, how often or how many times?

3. With whom did you mainly interact and make connections (could be either staff or students or both)?

4. Which of the connections were most influential on your own development as a musician and why? Remember, you can learn from negative experiences as well as positive ones. Please name individuals.

5. Did you find it fun or inspiring to participate in this class? If so, what was fun or inspiring?

6. Did you find it challenging to participate in this class? If so, in what ways?

7. Did you feel that the expectations of your participation in the ensemble work were clearly set out in class? In what ways (if any) were you able to contribute to setting these expectations?

8. Was this class different to your previous learning experiences (e.g. at school, other university courses)? If so, in what ways was it different?

Cycle 2 Semester 2 (September)

Please answer the following questions in relation to your participation so far this year in the Wednesday 10–12 classes (i.e. group classes and ensemble rehearsals). The experiences you reflect on may be either positive or negative.

1. What new knowledge or skills have you acquired?

2. In what ways has your understanding or perspective been challenged or changed?

3. In what ways has your participation inspired or motivated you?

4. In what ways have you gained confidence as a result of your participation?

5. What access to new people have you gained? Do you trust them enough to turn to them for help?

6. Do you feel less isolated now than you did at the beginning of the year? In what ways?

7. Do you feel you are gaining a reputation as a result of your participation?

8. What was your evaluation of the quality of the end of semester concert?

9. Do you see opportunities for learning that you did not see before you participated in this class? What are they?

Cycles 3, 4 and 5 Semester 2 (October)

Please answer the following questions in relation to your participation this year in the Wednesday 10–12 classes (i.e. group classes and ensemble rehearsals). The experiences you reflect on may be either positive or negative.

1. What skills do you feel you have acquired through these classes? These skills might be musical or more general skills.

2. Where have you applied the skills you have acquired from these classes?

3. Have you been able to use a connection you’ve made in this class to accomplish something outside of class?

4. When and how did you use ePortfolio? Did this help you learn or acquire new skills?

5. Did you feel that you were able to contribute to the shape and direction of the classes in any way?

6. What aspects of your performance has your participation in the classes affected? Have you achieved something new? Are you more successful generally?

7. What has the university been able to achieve because of your participation in this class?

8. Has your participation in this class changed the way in which you view music or your participation in it? Can you see new possibilities as a result of your participation?

All responses are confidential and will be anonymised in reporting of results. Thank you for participating.