The aftermath of battle

A great battle has rarely been fought with such disastrous short-sightedness, improvisation and negligence. The incompetence of the leaders has rarely led to such a bloodbath.

When, on the evening of 22 June 1859, the Austrian Emperor ordered his army, which had assembled on the previous evening to the east of the River Mincio, which flows out of Lake Garda and marks the border between Lombardy and Venetia, to conduct a countermarch so as to occupy the hills around the little town of Solferino on the other side of the river, he was in no doubt that the line of the Pieve would hold up the progress of his enemies for several days, since the Austrians had destroyed all the bridges across that river as they withdrew. Having neglected to give orders for reconnaissance, the Emperor was unaware that the Franco-Piedmontese were already crossing the Pieve on bridges built by the engineers corps.

As for the Franco-Piedmontese, they were convinced that the decisive battle would be fought – as in 1848 – to the east of the Mincio, in the area delimited by the four fortresses of Peschiera, Mantua, Verona, and Legnago, Austrian strongholds that commanded access to Venetia. Even worse, the general staff officers were so sure of themselves that they refused to give credence to the report sent by Commander Morand of the first Zouave battalion. Having ventured as far as Solferino, as day dawned on 23 June, Morand looked down from the imposing mediaeval tower, which rose high above the entire area, to see long columns of Austrian soldiers, easily identified in their white uniforms, who had crossed the Mincio and were moving westward. The French and the Piedmontese armies were in marching formation and did not even have liaison officers. Therefore, throughout 23 June, two huge armies, with a total of over 300,000 men, were in the same part of the territory, just a few kilometres from each other, without either of them suspecting the presence of the enemy.

The two armies clashed at daybreak on 24 June – without a plan of operations, without artillery preparation, and … without medical services. In such circumstances, disaster was inevitable. The commanders of both armies committed ever-greater resources to seizing the tower on the heights above Solferino. They hoped that – once captured – it would enable them to see what was going on and to regain control of the operations. The artillery fire and shelling wreaked havoc among the regiments who were mounting the attack in serial ranks.

When the fighting was over, the French army was in no state to make the most of its victory. The exhausted troops were trapped by an exceptionally fierce rain-and-hail storm. Appalled by the extent of the disaster and terrified at the thought that prolonged sieges and a third major battle – following Magenta and Solferino – would be needed to liberate Venetia, Napoleon III wanted nothing more than to put an end to the campaign, even if it meant betraying his Piedmontese ally. The very next day he sent an emissary to Emperor Francis Joseph. An armistice was signed a few days later.Footnote 1

A costly victory for the Franco-Piedmontese after long hours of intense fighting, the battle of Solferino paved the way for the independence and unification of Italy but it was also the bloodiest massacre that Europe had known since Waterloo. Fifteen hours of fighting left 6,000 dead and nearly 40,000 wounded.Footnote 2 The medical services of the Franco-Sardinian armies, which had to deal with the consequences of the battle, were completely overwhelmed and the negligence of the supply corps was exposed. The French army had four veterinary surgeons for 1,000 horses, but only one medical doctor for every 1,000 men; the medical service's means of transport were requisitioned to convey munitions and crates of dressings were left behind in the rear, only to be sent back to France, still sealed, at the end of the campaign.Footnote 3 According to the report submitted by General Paris de la Bollardière, the French army's quartermaster-general, it took six days – yes, six days – to remove 10,212 wounded soldiers from the field.Footnote 4

When the first shots rang out, the French army had only one field hospital in the vicinity of Solferino, the one attached to the General Headquarters that had been set up at Castiglione delle Stiviere, a few kilometres from the centre of the battle. It had three doctors and six auxiliaries – almost as good as none. Most of the medical corps – some 180 doctors – had been left behind because of insufficient transport.

Helped along by their fellow soldiers or transported on local peasants' carts, the wounded soldiers were taken to the nearby villages in the hope of obtaining a little water, food, first aid, and shelter. More than 9,000 wounded soldiers thus arrived in Castiglione,Footnote 5 where the wounded soon outnumbered the able-bodied. There were wounded soldiers everywhere – the more fortunate among them being sheltered in houses or schools, while others lay in courtyards and churches, on the town squares, and in the narrow streets. More than 500 wounded soldiers were packed into the town's main church, the Chiesa Maggiore. One can only imagine what it was like.

That same day, 24 June, a businessman from Geneva, Henry Dunant, arrived in Castiglione. He was not a doctor and had urgent business to attend to. He hoped to meet Napoleon III, who was the only one able to take the decisions that could save his debt-ridden enterprise in Algeria.Footnote 6

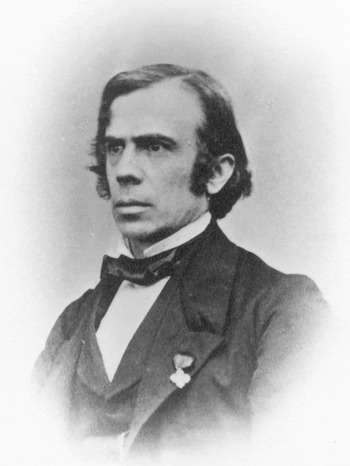

Henry Dunant (1828–1910 AD) in 1863, at the time of the foundation of the Red Cross. © Photo Library ICRC (DR)/BOISSONNAS, Frédéric.

However, Dunant was not the kind of man to harden his heart to the distress that he witnessed. He spent three days and three nights tending the wounded and the dying. He bathed their wounds, changed their dressings, gave the thirsty something to drink, took note of the last words of dying soldiers, and sent his coachman to Brescia to buy cloth, material for dressings, herbal teas, fruit, cigars, pipes, and tobacco. He mobilized volunteers – mostly women and girls – in an attempt to stem the flood of suffering and urged them to follow his example and take care of those in need regardless of which side they belonged to. Tutti fratelli, they repeated after Dunant, who encouraged them to show the same concern for wounded Austrian soldiers as for those from France or Piedmont. He wrote to the Countess Valérie de Gasparin to ask her to launch a fundraising subscription in Geneva and to purchase relief supplies.Footnote 7

Having spent three days and three nights at the bedside of the wounded, Dunant, utterly exhausted, went to Cavriana, the French army headquarters. He pleaded – unsuccessfully – the cause of the company that he headed in Algeria, but he also took the opportunity to ask for the release of the imprisoned Austrian doctors so that they could tend the wounded, a request that was granted.Footnote 8

On his way back to Geneva, he stopped in Brescia and in Milan to visit the military hospitals, where he found some of the wounded of whom he had taken care in Castiglione, and witnessed virtually the same distress, suffering, and death. He finally arrived in Geneva on 11 July 1859, the day on which Napoleon III and Francis Joseph met in Villafranca and, in just two hours, laid the foundation for peace.Footnote 9 After a few days of rest, Dunant again focused on his business affairs in Algeria.

Altogether, Dunant had only spent about two weeks attending the wounded of the battle of Solferino but he had established – without being aware of it – two of the pillars of what was to become the Red Cross and international humanitarian law: impartiality in the provision of medical care and the principle of the neutrality of medical action.

The power of testimony

It is, however, not because Dunant cared for the wounded in Solferino that he is remembered today.Footnote 10 The names of other willing helpers who demonstrated just as much commitment – at Solferino and elsewhere – have long been forgotten. If Henry Dunant is remembered today, it is first and foremost because he reported on what he had seen and done in northern Italy.

In fact, Dunant was unable to forget the wounded of Solferino. As soon as his business dealings in Algeria permitted, he went into retreat in Geneva, studied the campaign in Italy, and committed his testimony to a book that became a historical milestone, A Memory of Solferino.Footnote 11

The first pages of the book give a vivid account of the battle, in an epic style that is typical of military writing of that period – flags wave in the wind, bugles call, drums beat, uniforms shine brightly, and intrepid battalions mount an attack under enemy fire. Then suddenly the tone changes:

When the sun came up on the twenty-fifth [of June], it disclosed the most dreadful sights imaginable. Bodies of men and horses covered the battlefield; corpses were strewn over roads, ditches, ravines, thickets and fields; the approaches to Solferino were literally thick with dead.Footnote 12

The hidden face of war was exposed: the protracted anguish of the wounded, who were removed from the battlefield one at a time, of the mutilated, of those dying of thirst, of those whose wounds had had time to become infected and who had become delirious with pain and fever; the Chiesa Maggiore packed full with wounded and dying soldiers; the screams of the wretched men undergoing hasty amputations without anaesthetic or hygiene; the smell of decay; the clouds of flies, thirst, hunger, neglect, despair, and death.

Dunant used his description to denounce the terrible injustice to which the soldiers were subjected. During the battle, their country expected them to accept every kind of trial and sacrifice. Once they had been wounded, they were deserted. ‘“Oh, Sir, I'm in such pain!” several of these poor fellows said to me, “they desert us, leave us to die miserably, and yet we fought so hard!”’Footnote 13

However, Dunant was not satisfied by merely testifying to the horrors of war. He concluded with two questions, which were, at the same time, two appeals:

But why have I told of all these scenes of pain and distress, and perhaps aroused painful emotions in my readers? Why have I lingered with seeming complacency over lamentable pictures, tracing their details with what may appear desperate fidelity?

It is a natural question. Perhaps I might answer it by another: Would it not be possible, in time of peace and quiet, to form relief societies for the purpose of having care given to the wounded in wartime by zealous, devoted and thoroughly qualified volunteers?Footnote 14

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement was born of this first question, this first appeal. But there was more. For those ‘zealous volunteers’ to be able to carry out a mercy mission on the battlefield, they would have to be recognized and respected. Hence the second appeal:

On certain special occasions, as, for example, when princes of the military art belonging to different nationalities meet at Cologne or Châlons, would it not be desirable that they should take advantage of this sort of congress to formulate some international principle, sanctioned by a Convention inviolate in character, which, once agreed upon and ratified, might constitute the basis for societies for the relief of the wounded in the different European countries?Footnote 15

That second question marks the starting point of contemporary international humanitarian law.

The book came off the press in early November 1862, and 1,600 copies were printed, 400 of which were marked ‘Not for sale’. It was an ‘open letter to world leaders’, a manifesto that Dunant sent to his friends and relatives, as well as to sovereigns, government ministers, army generals, writers, and well-known philanthropists.Footnote 16

Helped by the author's unparalleled gifs as a communicator and a style which earned the recognition of eminent writers of his time, the book immediately resonated with Dunant's contemporaries. In the following months two further editions were printed. The book was translated into Dutch, Italian, and German (three times), and Charles Dickens published substantial excerpts in his journal All the Year Round. Footnote 17 Like Uncle Tom's Cabin, which had been published ten years earlier,Footnote 18 and like Les Misérables, which was published the same year, 1862, A Memory of Solferino has stirred people's emotions and changed something in the course of history. Congratulatory letters and messages of support flooded in from all quarters, particularly from sovereigns, government ministers, and other influential people.Footnote 19

Nonetheless, presenting an ingenious new idea and stirring up emotions by means of a cleverly orchestrated promotion campaign would be doomed if the idea was not converted into action. One of Dunant's fellow citizens, Gustave Moynier, two years his senior, proposed the strategies that would transform the dream into reality and the idea into action.

Gustave Moynier

The many public figures to whom Dunant sent a copy of his book included, naturally enough, Gustave Moynier, who was the chairman of a local charity in his native city, the Geneva Public Welfare Society.Footnote 20 The two men knew each other. As teenagers, they had met at a ball in Céligny, in the countryside near Geneva. Both of them were members of the Geneva Geographical Society.Footnote 21

Gustave Moynier (1826–1910), one of the founders of the Red Cross, member of the Geneva Committee. © Photo Library ICRC (DR)/BOISSONNAS, Frédéric.

A lawyer by training, with a mind that was as positivist and pragmatic as Dunant's was idealistic and visionary, Gustave Moynier was not a man to be carried away by his emotions.Footnote 22 However, remembering, forty years later, his first reading of A Memory of Solferino, he admitted that his heart ‘had been profoundly stirred as he read those moving pages’.Footnote 23

Hardly had he closed the book than he contacted the author, to discover that, while Dunant had presented two ideas that were to have a remarkable impact on the course of history and was actively promoting his book in a public relations campaign that was far ahead of its time, he did not seem to have a strategy in mind for the implementation of those ideas. Moynier recounted that first meeting:

I thought that he must have reflected on how to realize his dream and that he could perhaps give me some helpful suggestions with regard to establishing that institution that, until then, he was the only one to have thought of. In the latter regard, I have to admit that I was mistaken, as I caught him off guard, before, he assured me, he had conceived the slightest plan for the implementation of his invention.Footnote 24

Whereas Dunant did not have a strategy, Moynier was able to make use of his position as the chairman of the Geneva Public Welfare Society and his experience of the international welfare congresses that he had attended in Brussels (1856), Frankfurt (1857), and London (1862).Footnote 25 He therefore proposed to refer Dunant's proposals to the Society.

The founding of the International Committee of the Red Cross

On 15 December 1862, Moynier presented Dunant's proposals to the Society's General Commission, which was, in effect, its executive body. The proposals received a cool reception. While everyone acknowledged the generosity of Dunant's intentions, they were keen to point out, in particular, the obstacles to their implementation. ‘It was decided that it was not our Society that could deal with that’ was the conclusion recorded in the minutes of the meeting.Footnote 26 It is easy to understand why the Commission members retreated in the face of the challenge presented to them. As Moynier wrote many years later:

How could it be presumed that an association modestly devoted to the consideration of local interests, placed in a small country, and having at its disposal no means of action beyond its own limited sphere, should dream of launching into an adventure of such gigantic magnitude as the subject on which it had been consulted?Footnote 27

Moynier, however, was not the kind of man to admit defeat. He renewed his efforts at the next meeting of the General Commission on 28 January 1863. Having learned from his defeat on 15 December 1862, he set his sights on a clearly defined target: as an international welfare congress was to be held in Berlin in September 1863, Moynier suggested that the Society submit Dunant's proposals to the congress and that it appoint a small drafting committee for that purpose. As that suggestion did not – at least in appearance – commit the Society to a great deal, it was accepted.

Bolstered by this support, Moynier convened a general assembly of the Society on 9 February 1863. Taking up his proposal, the general assembly appointed five members to the drafting committee: Dunant, Moynier, Dr Louis Appia, Dr Théodore Maunoir, and General Dufour, who conferred his authority and tremendous prestige on the project.Footnote 28 What was drafted on that occasion was the birth certificate of the International Committee of the Red Cross.Footnote 29

Dr Louis Appia (1818–1898), one of the co-founders of the Red Cross, member of the Geneva Committee. © Photo Library ICRC (DR)/BOISSONNAS, Frédéric.

Mr Théodore Maunoir (1806–1869), one of the co-founders of the Red Cross, member of the Geneva Committee. © Photo Library ICRC (DR)/BOISSONNAS, Frédéric.

General Guillaume-Henri Dufour (1787–1875), one of the co-founders of the Red Cross, member of the Geneva Committee, signatory of the Geneva Convention of 22 August 1864, ICRC President (1863–1864) © Photo Library ICRC (DR)/BOISSONNAS, Frédéric.

From the founding of the ICRC to that of the Red Cross

The drafting committee held its first meeting on 17 February 1863. Its five members immediately decided to set it up as the Permanent International Committee for the Relief of Wounded Soldiers. That decision was surprising as it obviously exceeded the limits of the mandate that the Geneva Public Welfare Society conferred on the Committee. However, it can be explained by the objectives that its five members had set themselves and that emerged with an astounding clarity at their first meeting.Footnote 30 To understand these objectives, it is appropriate to recall the situation of the military medical services in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Despite medical progress at that time, those services were in a state of utter decay. The French Revolution was largely to blame. Conscription had relegated the medical services to the bottom of the quartermaster-generals' list of concerns, whereas the increased size of armies led to greater numbers of soldiers being killed and wounded. Under the Ancien Régime, armies were expensive to maintain because the men were mercenaries who had to be recruited, kitted out, trained, and paid. A first-class medical corps was seen as the best way to maintain the royal armies' limited strength. With conscription, the quartermaster-generals ceased to rely on surgery, and instead counted on new levies to make up for the losses. Moreover, from 1815 to 1854, Europe enjoyed a long period of peace and stability. The size of the medical corps was reduced to peacetime needs. However, there is no similarity between the needs of an army in barracks and those of an army in the field.Footnote 31 The results were plain to see: wound for wound, the chances of survival for soldiers serving under Napoleon III were far less than for their counterparts in the army of Napoleon I and probably worse under Napoleon I than under Louis XV.Footnote 32

But that was not all. Before going into battle, it was customary practice among Ancien Régime generals to agree on the location of their medical posts, which had to be respected. That wise precaution meant that medical posts could be set up in the immediate vicinity of the battlefield. That custom – the existence of which was unknown to the five members of the Committee – was abandoned at the time of the Revolution.Footnote 33 Without a distinctive emblem recognized by all countries, the stretcher-bearers could not collect the wounded until the fighting was over as they otherwise risked finding themselves caught in the enemy's firing line.Footnote 34 To protect them from enemy fire, first-aid posts and field hospitals were established well away from the battlefield. This meant, however, that the wounded had to endure lengthy transport times, during which fractures were displaced and wounds festered.Footnote 35 During a retreat, doctors and nurses had no choice but to abandon the wounded if they were to avoid being taken captive and sharing the fate of the vast numbers of prisoners of war. During the Italian campaign the Austrian doctors who fell into the hands of the coalition forces were locked away in the Milan fortress.Footnote 36 They would have been more useful if they had been able to assist their French colleagues. That was the disastrous situation that Dunant had witnessed in Solferino and described in his book. That was the starting point.

To respond to this state of affairs, Dunant's idea was to establish volunteer relief societies that would rely on private support. So that they would be ready to act when needed, the societies would be set up on a permanent basis during peacetime. They would not wait for hostilities to start before establishing relations with the military authorities because the authorities would then be too busy fighting the war to discuss other matters. Governments had therefore to be associated with efforts to help the wounded from the outset. The main tasks of the societies would be to recruit and to instruct volunteer nurses, who would be available in times of conflict to provide support for their country's army medical corps and, if the situation arose, for the medical personnel of a belligerent country if the nurses' country of origin remained uninvolved in the conflict. If war broke out, the societies would send their volunteer nursing staff to follow the armies. This staff would place themselves at the disposal of the military commanders whenever they were needed. They would care for the wounded of all sides without distinction.Footnote 37 To be able to work safely and effectively, the volunteers had to be recognizable. They therefore had to be given a distinctive sign:

a badge, uniform or armlet might usefully be adopted, so that the bearers of such distinctive and universally adopted insignia would be given due recognition.Footnote 38

But that was not enough. What point was there in sending volunteer nurses after the armies if medical personnel were exposed to enemy fire and if supplies could be seized and diverted? Medical personnel and the volunteer nurses had to be shielded from the fighting.

The five founding members seemed to agree on everything: on the fact that the small drafting committee set up by the Geneva Public Welfare Society was to be established as the Permanent International Committee for the Relief of Wounded Soldiers, without – of course – consulting those who had given it its brief; on the appointment of General Dufour as its president, of Moynier as the vice-president, and of Dunant as the new organization's secretary; on the organizational structure of the future relief societies; on their dealings with the military authorities; on a uniform distinctive emblem – the same in every country – to designate the volunteer nurses, etc. However, a careful reading of the minutes of the meeting shows that there was at least one point on which agreement had not been reached. The last paragraph of the minutes states:

Finally, Mr Dunant particularly underlined the hope he expressed in his book A Memory of Solferino: that the civilized Powers would subscribe to an inviolable, international principle that would be guaranteed and consecrated in a kind of concordat between Governments, thus serving as a safeguard for all official or unofficial persons devoting themselves to the relief of victims of war.Footnote 39

What was at stake was the principle of legal protection for the members of the medical corps and the volunteer nurses on the battlefield. Although the minutes of the meeting do not say so, the impression is that, on that point, Dunant was on his own. Had he obtained the support of his colleagues on that crucial matter, it was unlikely that Dunant, who was keeping the minutes, would have failed to note it. Here was the first source of friction, the first blemish – barely perceptible at the time but with consequences that would not fail to become apparent later on.

As Dunant went back to Paris to attend to his Algerian business affairs, nothing of significance happened for the next five months. The Committee held its third meeting on 25 August 1863. It started with a thunderbolt: Moynier announced that the international welfare congress that was to be held in Berlin in September would not take place. However, he immediately suggested, with Dunant's backing, that the Committee convene its own congress in Geneva.Footnote 40

The Committee agreed and instructed Moynier and Dunant to write letters of invitation and to finalize the ‘draft concordat’ which had been prepared by Dunant and which laid the foundations of the future relief societies. On 1 September, the letters of invitation, accompanied by the draft concordat finalized by Moynier and Dunant, were dispatched.Footnote 41 It was expected that the draft concordat would form the basis for the deliberations of the planned international conference.Footnote 42

Was agreement easily reached on the content of the draft concordat? Probably, but at what price? The idea – dear to Dunant – of ensuring the neutrality of the volunteer nurses and of the military medical personnel was not included in the circular of 1 September or in the draft concordat.

As there were eight weeks before the start of the congress, Dunant took advantage of the time to travel to Berlin, at the invitation of his friend Dr Johan-Christian Basting, the chief medical officer in the Dutch army. An impenitent Calvinist and Pietist like Dunant himself, Basting had translated A Memory of Solferino into Dutch. Berlin was hosting a meeting of the International Statistical Congress – with the participation of the leading military physicians of the time.Footnote 43

Thanks to Dr Basting's support, Dunant was able to attend the International Statistical Congress. The two men wrote a speech that Basting gave to the fourth section of the congress, which was attended by military doctors.Footnote 44 Was Dunant given the support of those military doctors as he claimed? That is not certain.Footnote 45

In any event, Dunant took advantage of the occasion to have a new circular printed in Berlin on behalf of the Geneva Committee – but without having consulted his colleagues. In it he broadened the scope of the October conference and suggested that the matter of granting neutral status to the army medical corps be also discussed: ‘The Geneva Committee proposes … The Geneva Committee requests …’. The approach was admittedly somewhat cavalier. The circular was dispatched from Berlin on 15 September.Footnote 46

On the return journey, Dunant stopped in Dresden, Vienna, Munich, Stuttgart, Darmstadt, and Karlsruhe. In each city he was given a princely welcome. His book opened every door. He took advantage of the situation to plead the cause of the wounded and that of granting neutrality to the medical services, and to make sure that the various German states were going to accept the Committee's invitation.Footnote 47

He arrived back in Geneva on 19 October, probably feeling very pleased with the results of his trip. His colleagues gathered to hear what he had to say. No doubt, they would congratulate him. That is where he was mistaken. The Committee members had first learned of the Berlin circular on opening their correspondence and the news had obviously stuck in their throats.Footnote 48 The minutes of the meeting held on 20 October note:

After the Statistical Congress, Mr Dunant had thought it wise to print, at his own expense, a new circular dated September 15, in which neutral status was requested for the wounded, ambulances, hospitals, medical corps and officially recognized voluntary relief services.Footnote 49

Had one of his colleagues voiced a word of approval, Dunant, who wrote the minutes, would not have failed to record it. ‘We thought you were asking the impossible’, Moynier told him drily.Footnote 50 As it was too late to withdraw that unfortunate circular, the Committee decided to ignore it. In any case, the delegates were already on their way to Geneva.

The Geneva International Conference to Study Ways of Overcoming the Inadequacy of Army Medical Services in the Field was opened by General Dufour on 26 October 1863 at the Palais de l'Athénée. It was attended by thirty-six people, eighteen of whom had been sent as delegates ad audiendum et ad referendum by fourteen governments; six delegates represented various charitable organizations; seven people were there in a private capacity; and of course the five members of the Geneva Committee were also present.Footnote 51

The hybrid nature of the group should not be considered odd. In fact, it was inherent in the nature of the Geneva Committee's undertaking, since the objective was not to create a new branch of the bureaucracy in each country but to establish relief societies that would mobilize private resources. Nonetheless, the societies could not send volunteer nursing staff to the front without the protection of their respective governments. As the support of those governments had to be requested in advance in peacetime, they had to be associated with the undertaking from the start. That explains the mixture of public and private participation at the 1863 Conference. Indeed, all International Red Cross and Red Crescent Conferences since 1863 have been attended by delegations from the National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, as well as by representatives of the states party to the Geneva Conventions.Footnote 52

After making a welcome speech, General Dufour handed the chair to Moynier, who elaborated on the draft prepared by the Geneva Committee. Dunant was appointed secretary of the meeting. The Conference adopted the draft concordat prepared by the Geneva Committee as the basis for its discussion. The general debate centred on the organization of the national committees and, in particular, on the feasibility of sending volunteer nurses to follow the armies. Very divergent opinions emerged during the debate: some participants, especially Dr Basting, the delegate from the Netherlands, and Dr Löffler, the Prussian delegate, were enthusiastic.Footnote 53 Dr Rutherford, the United Kingdom delegate, had reservations. In his view, it was the responsibility of the states, and of them alone, to take care of those wounded in war; what was needed was a reform of the military medical corps, rather than the creation of relief societies which would let governments off lightly.Footnote 54 At the time, England was the only nation to have a medical corps worthy of that name. The lessons of the Crimean War (1854–1856) and the example set by Florence Nightingale had borne fruit. As for the French delegates – the deputy quartermaster-general de Préval and Dr Boudier – they were resolutely hostile: there should be no civilians on the battlefield. As they saw it, the volunteer nurses would not be able to withstand the rigours of military campaigns and they would never be at the right place when they were needed. Mules were all that was required. They would be far more useful than volunteer nurses to collect the wounded when the fighting was over. ‘Mules, mules, that is the Gordian knot in this matter!’ Dr Boudier exclaimed in a flight of eloquence deserving of a better aim.Footnote 55 After those observations, the Geneva Committee's undertaking looked as if it were doomed. Two doctors were to save the situation: Dr Maunoir, who skilfully demolished the objections raised by the French delegates by recalling the stark denial which the quartermaster-general's claims received at Solferino, and Dr Basting, who contrasted Dunant's experience with the French delegates' gloomy predictions:

Mr Dunant also has some experience of the things we are discussing, as he himself tried to provide relief for the wounded members of the French army after the Battle of Solferino … He is not presenting us with a desk-based theory but with facts.Footnote 56

The Conference then proceeded to scrutinize, one article at a time, the draft concordat prepared by the Geneva Committee and adopted it with some slight editorial adjustments that had no impact on its content. The Conference was thus drawing to a close without any discussion of the Berlin proposals. However, that was to reckon without the vigilant Dr Basting, who laid bare a serious misunderstanding. When Basting asked Moynier when he planned to open the discussion on the Berlin proposals, Moynier replied that the Geneva Committee had not envisaged debating those points. To which Basting replied that ‘he feared that the honourable Geneva Committee had not really understood why the delegates had taken up its invitation’. He recalled the support of the Berlin congress and stressed that granting neutrality to the medical services was the very matter in which the governments were most interested.Footnote 57

As the secretary to the conference, Dunant could not take part in the debates. Did he use Dr Basting to launch a discussion of an idea that was very dear to his heart but which his colleagues on the Geneva Committee would have preferred not to raise because they thought it a pipe dream? We will probably never know. But is it possible that his colleagues thought nothing of the kind?

Whatever the case may be, the misunderstanding was clear. The Geneva Committee wanted to avoid discussing the Berlin proposals because it feared that they would be unacceptable to the government delegates, whereas it was those very proposals that most interested those delegates – especially, the military doctors. Indeed, those doctors knew better than the members of the Geneva Committee how many doctors, nurses and stretcher-bearers were killed during battle, which did not benefit anyone as they were not combatants.

To be fair to Moynier, as soon as his mistake became clear, he became, like Dunant, a fervent advocate of the principle of granting neutrality to the medical services.Footnote 58 He chaired the Conference with great skill. After four days of deliberations, the Conference adopted ten resolutions that laid the foundations of the future Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies.

Resolutions of the Geneva International Conference of 1863

Article 1. Each country shall have a Committee whose duty it shall be, in time of war and if the need arises, to assist the Army Medical Services by every means in its power. …

Article 2. An unlimited number of Sections may be formed to assist the Committee, which shall be the central directing body.

Article 3. Each Committee shall get in touch with the Government of its country, so that its services may be accepted should the occasion arise.

Article 4. In peacetime, the Committees and Sections shall take steps to ensure their real usefulness in time of war, especially by preparing material relief of all sorts and by seeking to train and instruct voluntary medical personnel.

Article 5. In time of war, the Committees of belligerent nations shall supply relief to their respective armies as far as their means permit; in particular, they shall organize voluntary personnel and place them on an active footing and, in agreement with the military authorities, shall have premises made for the care of the wounded.

They may call for assistance upon the Committees of neutral countries.

Article 6. On the request or with the consent of the military authorities, Committees may send voluntary medical personnel to the battlefield where they shall be placed under military command.

Article 7. Voluntary medical personnel attached to armies shall be supplied by the respective Committees with everything necessary for their upkeep.

Article 8. They shall wear in all countries, as a uniform distinctive sign, a white armlet with a red cross.

Article 9. The Committees and Sections of different countries may meet in international assemblies to communicate the results of their experience and to agree on measures to be taken in the interests of the work.

Article 10. The exchange of communications between the Committees of the various countries shall be made for the time being through the intermediary of the Geneva Committee.

Thanks to Dr Basting's insistence, the Conference also debated the neutrality of medical services. However, considering that it was not qualified to adopt resolutions in that regard, it confined itself to adopting three recommendations directed at governments:

A. that Governments should extend their patronage to Relief Committees which may be formed, and facilitate as far as possible the accomplishment of their tasks;

B. that in time of war the belligerent nations should proclaim the neutrality of ambulances and military hospitals, and that neutrality should likewise be recognized, fully and absolutely, in respect of official medical personnel, voluntary medical personnel, inhabitants of the country who go to the relief of the wounded, and the wounded themselves;

C. that a uniform distinctive sign be recognized for the Medical Corps of all armies, or at least for all persons of the same army belonging to this Service; and that a uniform flag also be adopted in all countries for ambulances and hospitals. Footnote 59

The resolutions of the Constitutive Conference of October 1863 laid for more than sixty years the statutory foundations of the International Red Cross. In fact, it was not until the end of the First World War and the creation of the League of Red Cross SocietiesFootnote 60 that it was decided to give the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement a more complete statutory framework. Several years of negotiations resulted in the Statutes of the International Red Cross, which were adopted by the Thirteenth International Conference of the Red Cross meeting in The Hague in October 1928.Footnote 61 Until then, the resolutions of the October 1863 Conference were the Movement's fundamental charter. The resolutions and recommendations of the October 1863 Conference thus constituted, as it were, the birth certificate of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. As ICRC historian Pierre Boissier wrote:

The resolutions and recommendations adopted at the conference of October 1863 constitute the fundamental charter for the relief of persons wounded in war. They are among the few fundamental texts which have positively influenced the destiny of man. They have not eliminated war but they have diminished its hold over man and have deprived it of innumerable victims. In the great book of humanity, it pleads in favour of the human being.Footnote 62

At the closing meeting of the Conference, the delegates, conscious of the importance of the resolutions that they had just adopted and convinced of the ‘immense resonance that the measures planned by the conference [would] have in all countries’, adopted by acclamation a motion presented by Dr Basting, which paid tribute to the initiatives of Dunant and Moynier:

Mr Henry Dunant, by bringing about through his persevering efforts the international study of the means to be applied for the effective assistance of the wounded on the battlefield, and the Public Welfare Society of Geneva, by its support for the generous impulse of which Mr Henry Dunant has been the spokesman, have done mankind a great service and have fully merited universal gratitude.Footnote 63

From the founding of the Red Cross to the original Geneva Convention

‘The Committee has every reason to be pleased with the favourable achievements of the conference’ is the sober statement in the minutes of the meeting of the International Committee held on 9 November 1863.Footnote 64 In fact, it was a complete success as the conclusions of the conference far exceeded the expectations of the Committee members.

However, the good intentions still had to be translated into deeds. In response to a proposal by Moynier, the Committee decided to send a letter to the delegates who had taken part in the conference to encourage them to set up national committees in their respective countries and to ask them to inform the Geneva Committee of the extent to which their governments were willing to adhere to the resolutions and to the recommendations of the conference. The letter was sent on 15 November 1863.Footnote 65 In the following months, the first National Societies were established in Württemberg, in the Grand Duchy of Oldenburg, in Belgium, and in Prussia. In the following year, a National Society was established in Italy.Footnote 66 Having returned to Paris, Dunant was the primary founder of the French Red Cross.Footnote 67

At the same time, the Recommendations of the Constitutive Conference of October 1863 had to be codified into a rule of law that would be binding on the states that accepted it. A diplomatic conference therefore had to be convened. The Geneva Committee, a simple association established on the basis of a private initiative, did not consider that it was qualified to convene a conference of plenipotentiaries. A government that was willing to take on the task was needed, and that issue seems to have been a new source of friction between Dunant and his colleagues. Dunant, an impenitent Bonapartist, was convinced that the patronage of France, the dominant continental power since her victories in the Crimea and in Italy, was indispensable to the success of the diplomatic conference. His colleagues – Dufour and Moynier, in particular – considered that it would be preferable for the conference to be held under the auspices of Switzerland and wanted the Federal Council to send the invitations.Footnote 68

In the end, as the Committee wanted the diplomatic conference to take place in Geneva, the French Foreign Ministry tossed the ball back into the court of the Federal Council, but promised its support:

As the meeting will take place within the Swiss Confederation, diplomatic usage dictates that the official invitations to the various governments should be addressed by the Federal Council.Footnote 69

In the meantime, however, an obscure dynastic dispute over Schleswig triggered a war that pitted Denmark against Prussia and Austria. On 1 February 1864 the Austro-Prussian armies crossed the Eider and began their invasion of Denmark. Prima facie, that situation did not directly affect the Geneva Committee as, in accordance with the terms of the Resolutions adopted by the October 1863 Conference, it was the remit of the National Committees – and not of the International Committee – to provide relief for the wounded on the battlefield. Nonetheless, the opportunity to demonstrate on the field of battle the feasibility of the Geneva Committee's proposals was too good to miss.

At its meeting on 13 March 1864, the Committee decided – ‘if we [are] to preserve our character as an impartial and international body’ – to send two delegates to Schleswig, one to the Danish side, and another to the side of the Austro-Prussian allies. It appointed to that task Captain van de Velde, a delegate sent by the Netherlands to the October 1863 Conference, and Dr Appia, a member of the Geneva Committee.Footnote 70 Concerned not to encroach on the competencies of others, the Committee thought it wise to instigate the establishment of a Geneva Red Cross Section that would take responsibility for sending those delegates – thus sowing the seed of a future Swiss Red Cross Society.Footnote 71 Their mandate required them ‘to give whatever help they could to the wounded and, by so doing, to show the Committee's keen interest in the fate of victims of war’ and, in particular, ‘to examine, on the spot, how the decisions of the Geneva Conference were being, or might be, implemented’.Footnote 72 In fact, the two delegates harvested a significant number of observations. On the delegates' return, the Geneva Committee hastened to publish their reports in a volume entitled Secours aux blessés (Relief for the Wounded). That volume also included a study by Dr Brière, a divisional doctor in the Swiss army and a Swiss delegate at the October 1863 Conference, who had just unearthed four treaties concluded under the Ancien Régime for the protection of hospitals and medical services on the battlefield; it also included a study by Dr Maunoir on the remarkable work carried out by the Sanitary Commission – a voluntary relief organization – on behalf of the victims of the American Civil War.Footnote 73

Why assemble those four documents, at first glance so dissimilar, in one volume? The link between them is sufficiently clear: what they have in common is an apologetic objective; to use specific examples from the past and the present to show that voluntary assistance and legal protection of the military medical services on the battlefield was not just wishful thinking.

The Geneva Committee was preparing to play a difficult game. Following up on the request of the Geneva Committee and bolstered by the diplomatic support of France, the Federal Council sent an invitation on 6 June 1864 to all the governments of Europe (including the Ottoman Empire), as well as to the United States of America, Brazil, and Mexico.Footnote 74 It enclosed a draft convention prepared by the Geneva Committee – in reality, by Moynier and General Dufour. At the forthcoming conference, the Committee would not be dealing with a heterogeneous assembly, composed in part, as in 1863, of philanthropists who could be expected to be well intentioned, but with a gathering of diplomats concerned for the interests of their own governments.

The Diplomatic Conference took place from 8 to 22 August 1864 at Geneva Town Hall and was attended by delegates from sixteen states.Footnote 75

Signature of the Geneva Convention of 22 August 1864 (painting by Armand Dumaresq, displayed at Geneva Town Hall) © Photo Library ICRC (DR).

General Dufour and Gustave Moynier took part as Swiss delegates.Footnote 76 As the senior representative of the state hosting the conference, Dufour was appointed as chairman, but he called on the support of Gustave Moynier who, as the main writer of the draft treaty, was in a better position than anyone else to advise him and to explain the content of the different articles to the delegates. The other members of the International Committee were authorized to follow the work of the Conference ‘but merely as observers, without the right to speak or vote’.Footnote 77

That Diplomatic Conference was unlike any other: its purpose was not to reach a post-conflict settlement or to mediate between opposing interests, but to lay down general rules for the future so as to protect the medical services and those wounded in wartime. The report sent by the Swiss plenipotentiaries to the Federal Council clearly shows the nature of the conference:

As is rarely the case at diplomatic congresses, there was no question of a confrontation over contradictory interests, nor was it necessary to reconcile opposing requests. Everyone was in agreement. The sole aim was to reach formal agreement on a humanitarian principle which would mark a step forward in the law of nations, namely the neutrality of wounded soldiers and of all those looking after them. This was the wish expressed by the Conference of October 1863 and the starting point for the 1864 Conference.Footnote 78

The Diplomatic Conference adopted as the basis for discussion the draft convention prepared by the International Committee.Footnote 79 The only bone of contention concerned the granting of neutral status to volunteer nursing staff sent to follow the armies by the Societies for Relief to Wounded Soldiers, the future National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. The French delegates said that they had no authority to sign a convention mentioning volunteer nurses, while other delegates wanted to ensure the neutrality of those nurses. In the end, the Conference adopted a compromise solution: since volunteer nurses called to follow armies during military campaigns would be subject to military discipline, they would be considered part of the military medical corps; this would ensure their neutrality, although they were not specifically mentioned in the Convention.Footnote 80

The Geneva Convention was signed on 22 August 1864. No treaty has ever had such an impact on relations between belligerents. It is as follows:

Convention for the amelioration of the condition of the wounded in armies in the field

Article 1. Ambulances and military hospitals shall be recognized as neutral and, as such, protected and respected by the belligerents as long as they accommodate wounded and sick. …

Article 2. Hospital and ambulance personnel, including the quarter-master's staff, the medical, administrative and transport services, and the chaplains, shall have the benefit of the same neutrality when on duty, and while there remain any wounded to be brought in or assisted.

Article 3. The persons designated in the preceding Article may, even after enemy occupation, continue to discharge their functions in the hospital or ambulance with which they serve, or may withdraw to rejoin the units to which they belong. …

Article 5. Inhabitants of the country who bring help to the wounded shall be respected and shall remain free.

Generals of the belligerent Powers shall make it their duty to notify the inhabitants of the appeal made to their humanity, and of the neutrality which humane conduct will confer.

The presence of any wounded combatant receiving shelter and care in a house shall ensure its protection. An inhabitant who has given shelter to the wounded shall be exempted from billeting and from a portion of such war contributions as may be levied.

Article 6. Wounded or sick combatants, to whatever nation they may belong, shall be collected and cared for.

Commanders-in-Chief may hand over immediately to the enemy outposts enemy combatants wounded during an engagement, when circumstances allow and subject to the agreement of both parties.

Those who, after their recovery, are recognized as being unfit for further service shall be repatriated.

The others may likewise be sent back, on condition that they shall not again, for the duration of hostilities, take up arms.

Evacuation parties, and the personnel conducting them, shall be considered as being absolutely neutral.

Article 7. A distinctive and uniform flag shall be adopted for hospitals, ambulances and evacuation parties. …

An armlet may also be worn by personnel enjoying neutrality but its issue shall be left to the military authorities.

Both flag and armlet shall bear a red cross on a white ground.

Article 8. The implementing of the present Convention shall be arranged by the Commanders-in-Chief of the belligerent armies following the instruction of their respective Governments and in accordance with the general principles set forth in this Convention.

Article 9. The High Contracting Parties have agreed to communicate the present Convention with an invitation to accede thereto to Governments unable to appoint Plenipotentiaries to the International Conference at Geneva. …

Article 10. The present Convention shall be ratified and the ratifications exchanged at Berne, within the next four months, or sooner if possible.

In faith whereof, the respective Plenipotentiaries have signed the Convention and thereto affixed their seals.

Done at Geneva, this twenty-second day of August, in the year one thousand eight hundred and sixty-four.Footnote 81

The Convention of 22 August 1864 was revised in 1906, 1929, and 1949. It was supplemented by new treaties granting protection to hospital ships, prisoners of war, and civilians in wartime. As the first treaty that was adopted in peacetime to protect the victims of wars to come, it marked the starting point of international humanitarian law as it is known today.

At the time, the members of the Geneva Committee and the delegates who took part in the 1864 Diplomatic Conference were convinced that they had written ex nihilo a new chapter in the law of nations. In fact, as we know today, rules intended to limit wartime violence have existed throughout history and in every civilization. However, generally speaking, those rules were inspired by religion. That was both their strength and their weakness – they were respected because they were thought to have been dictated by the revered divinity and were thus respected by adversaries from the same culture and with the same convictions. But when faced with an adversary who did not belong to that cultural group, combatants would often ignore such rules. We are familiar with the behaviour of the ancient Greeks and the Romans in dealing with those whom they considered as ‘barbarians’ and with the excesses of the Crusades.

By anchoring the protection of those wounded in war and of the military medical services in positive law, that is, on the consent of states enshrined in a convention, the International Committee and the Diplomatic Conference of 1864 took a decisive step forwards for humanity as they drafted and adopted humanitarian rules that could be accepted universally.

Conclusion

Much ground was covered in just a few years after Solferino! Only five years separated the battle and the adoption of the initial Geneva Convention; barely two years passed between the publication of Dunant's book and the Diplomatic Conference. Dunant was able to turn the trauma of Solferino into a book – which took his era by storm – and two ideas with an exceptional future: the Red Cross and the Geneva Convention. Nonetheless, neither of those ideas would have come to anything if Dunant had not had the help of four of his fellow citizens, who, with him, formed the International Committee.

At its beginning, it was no more than an initiative committee, intended to promote those ideas, but set to be dissolved as soon as they had been given practical form: ‘We shall be content to have promoted an institution which will gradually expand, and whose charitable work will certainly elicit universal support’, Gustave Moynier stated when presenting the Committee's proposals at the first meeting of the October 1863 conference.Footnote 82 That was echoed in Article 10 of the Resolutions of that conference: ‘The exchange of communications between the Committees of the various countries shall be made for the time being through the intermediary of the Geneva Committee’. If there had been the least doubt about how to interpret the words ‘for the time being’, that was dispelled by the report on that conference: ‘The provisional position of the Geneva Committee will cease when the committees in other countries have been formed’, declared one of the participants.Footnote 83 Moreover, two documents dating from 1864 show that the members of the Committee planned to disperse – with a sense of having done their duty – once the treaty was adopted.Footnote 84

It was expected that once the national committees had been set up, they would start corresponding with each other directly rather than through the intermediary of the Geneva Committee. It was also believed that the states party to the future treaty would feel honour bound to comply with its provisions. Lastly, it was thought that war was too trivial an affair to compromise the fine harmony that seemed to prevail between the young relief societies. In a flush of optimism, the editor of the Bulletin international des Sociétés de secours aux militaires blessés wrote in July 1870:

The essentially international feature of the societies under the aegis of the Red Cross is the spirit that moves them, the spirit of charity that causes them to come to the rescue wherever blood is shed on a battlefield, and to feel as much concern for wounded foreigners as for their own wounded countrymen. The societies constitute a living protest against the savage patriotism that stifles any feeling of pity for a suffering enemy. They are working to pull down barriers condemned by the conscience of our times, barriers that fanaticism and barbarity have raised and still too often strive to maintain between the members of a single family, the human species.Footnote 85

That was to harbour a number of illusions. From the very first days of the Franco-Prussian war of 1870–1871 – the first conflict to which the Geneva Convention applied – the young National Societies could be seen at each other's throats. Furthermore, the war led to the breakdown of diplomatic and postal relations between the belligerent countries. The French Red Cross and the German Societies asked the Geneva Committee to take charge of forwarding their communications. Governments soon followed this stance.

That is how the Geneva Committee's role as a neutral intermediary came about – that is, not initially planned, but dictated by events. Paradoxically, that is probably what has enabled the International Committee to weather a century and a half of conflicts, including two world wars: its existence is not the outcome of a predetermined plan, but the result of a need.

More generally, a piece was missing from the clever mechanism put in place by the 1863 and 1864 conferences: a central body in charge of protecting the general interests of the work and of maintaining its fundamental principles. Whatever the proclaimed intentions, national bodies are inevitably absorbed by national tasks and guided by national interests, which dictate their priorities. A complex international movement with branches in all countries cannot survive without a central body mandated to support the work of the national branches while remaining independent from all of them. That is the role that the International Committee of the Red Cross has played from the start, 150 years ago.

Annex

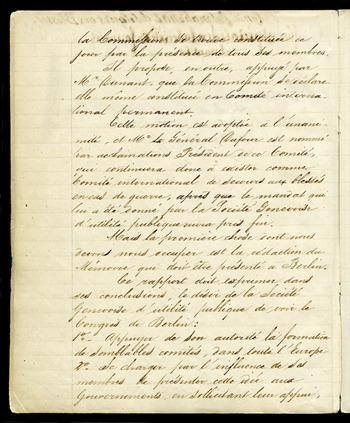

Minutes of the first meeting of the International Committee for the Relief of Wounded Soldiers (International Committee of the Red Cross), 17 February 1863.

Handwritten minutes taken by Dunant. © CICR/GASSMANN, Thierry. Page 1.

Handwritten minutes taken by Dunant. © CICR/GASSMANN, Thierry. Page 2.

Handwritten minutes taken by Dunant. © CICR/GASSMANN, Thierry. Page 3.

Handwritten minutes taken by Dunant. © CICR/GASSMANN, Thierry. Page 4.

Handwritten minutes taken by Dunant. © CICR/GASSMANN, Thierry. Page 5.

Handwritten minutes taken by Dunant. © CICR/GASSMANN, Thierry. Page 6.

Transcript of the Minutes of the first meeting of the International Committee for the Relief of Wounded Soldiers (today: International Committee of the Red Cross), 17 February 1863Footnote 86

International Committee for the Relief of the Wounded

Committee of the Society for the Relief of Combatants Wounded in Time of War

Meeting of the Committee held on February 17, 1863

Present: General Dufour, Doctor Théodore Maunoir, Mr Gustave Moynier, President of the ‘Public Welfare Society’, Doctor Louis Appia and Mr J. Henry Dunant.

Mr Moynier explained that the Geneva Public Welfare Society having decided, at its meeting of February 9, 1863, to give serious consideration to the suggestion made in the conclusions to the book entitled A Memory of Solferino, that Relief Societies for wounded soldiers should be set up in peacetime, that a corps of voluntary orderlies should be attached to belligerent armies, and having appointed General Dufour and Messrs Maunoir, Moynier, Appia and Dunant as members of the Committee charged with the preparation of a Memorandum on these matters for submission to the Welfare Congress to be held in Berlin in September 1863, the Committee was deemed to be duly constituted, all members being present.

He furthermore proposed, and Mr Dunant seconded, that the Committee should declare itself constituted as ‘Permanent International Committee’.

The proposal was adopted unanimously. On a show of hands General Dufour was elected President of the said Committee, which would thus continue to exist as an International Committee for the Relief of Wounded in the Event of War, after the mandate that it received from the Geneva Public Welfare Society had expired.

The first task before us was to draw up the Memorandum to be presented at Berlin.

In its conclusions, the said report should express the desire of the Geneva Public Welfare Society that the Berlin Congress should:

1. lend its authority to the creation of such Committees throughout Europe;

2. undertake to submit this project to Governments through the good offices of its members, and to request the support, opinions and advice of the said Governments.

Furthermore, the report should enlarge upon the concept of Relief Societies for wounded in time of war and present it to the public in such a way as to preclude all possible objections.

We should first lay down general principles and then state what action could be undertaken immediately in all European countries, whilst leaving each country, district, and indeed town, free to organize itself according to its own wishes and to pursue its work in the manner best suited to it.

General Dufour thought that the Memorandum should first state the need for the unanimous consent of the sovereigns and peoples of Europe, and should then determine the general line of action. Committees should be formed, rather than Societies, but such Committees should be organized throughout Europe, so that they might act simultaneously should war break out. Volunteer helpers were required who would place themselves at the disposal of the general staffs; we did not want to take the place of the Quartermaster's Department or of the medical orderlies. Finally, a badge, uniform or armlet might usefully be adopted, so that the bearers of such distinctive and universally adopted insignia would be given due recognition.

Dr Maunoir wished the question of international relief societies to be kept in the public mind as much as possible, since it always takes time to bring an idea home to the masses. It would be useful if the Committee ‘kept agitating’, if the expression might be allowed, for the adoption of our ideas by all, both high and low, by the rulers of Europe, no less than by the peoples.

Dr Appia thought that all documents likely to be of use should be procured, and that we should get into touch with the supreme military commands in the various countries.

Mr Moynier had already obtained documents from Paris which could be of service to us.

Mr Dunant thought the report should make it perfectly clear to the public that the present undertaking was not merely a matter of sending voluntary orderlies to a battlefield; he would like it to be carefully explained to the public that the question we had taken up was much wider in scope. It embraced the improvement of means of transport for the wounded; the amendment of the military hospital service; the general adoption of new methods of treating sick or wounded soldiers; the establishment of a veritable museum for these appliances (which would also be of benefit to civilian populations), and so on. In his opinion, the Committees should be permanent and should always be guided by a true spirit of international goodwill; they should facilitate the dispatch of relief supplies of various kinds, resolve customs difficulties, prevent any sort of waste and misappropriation, and so on. It was to be hoped that all European Sovereigns would take them under their patronage.

Finally, Mr Dunant particularly underlined the hope he expressed in his book A Memory of Solferino: that the civilized Powers would subscribe to an inviolable, international principle that would be guaranteed and consecrated in a kind of concordat between Governments, serving thus as a safeguard for all official or unofficial persons devoting themselves to the relief of victims of war.

The Committee requested Mr Dunant to draw up the Memorandum, and the latter asked members to supply him with written notes.

The Committee, under the chairmanship of General Dufour, appointed Mr Gustave Moynier vice-president and Mr Henry Dunant secretary.

The meeting then adjourned.

The present minutes approved.

J. Henry Dunant

Secretary