1. INTRODUCTION

More than two decades ago Alan Peacock acknowledged that «the search for some all-embracing economic theory of public expenditure growth is now generally recognized as a quimera» (Peacock Reference Peacock1992, p. 54). In effect, we still lack a definitive solution to the problems of fiscal political economy and the limits of fiscal capacity faced by modern democracies, but, although an all-embracing explanation remains elusive, advances in our knowledge of the intellectual roots of fiscal thought will enhance our understanding of collective preferences at the time of income redistribution through government intervention, and will surely ease the way towards a reasonable solution of the current fiscal crisis that blocks our economic growth. Continuous reference to Alexis de Tocqueville's predictions about the future of democracy, equality, redistribution and his background as a social scientist have established his work—especially Democracy in America—as a reference point for the study of fiscal political economy. As a privileged witness of the revolutionary change from aristocracy to egalitarian democracy, and as a forerunner of fiscal sociology, Tocqueville's ideas on the extension of the franchise could serve as guidance to the equally revolutionary expansion of the present-day social rights and entitlements, public expenditure and progressive taxes. Despite controversy, a consensus exists that, in the Ricardian tradition, Alexis de Tocqueville viewed the future of democracy as protected against the advances of excessive tax increases and income redistribution by the moderating effects of the extension of private property and the increase of general prosperity. In the words of L. L. Wade, «Tocqueville's central thesis—that the fisc in democracy will be managed responsibly only when the franchise is dominated by a property-owning […] middle class—remains an important and secure postulate» (Wade Reference Wade1985, p. 505). In effect, the literature has often portrayed Tocqueville as an unabated optimist regarding the effects of democracy on the aggregate preferences for higher taxes and fiscal redistribution.

Nevertheless, as is the case with many other aspects of Tocqueville's opinions on political economy, his views on the relationship between democracy's progress and the tax burden were more complex and sophisticated than a cursory view may suggest. In the much more philosophical second volume of his Democracy in America, his reflections on individual behaviour and cultural traits lend themselves to a modern analysis of voters' preference changes and apparent irrationality. Specifically, Tocqueville's reflections on the influence of moers on aggregate political behaviour cast doubt on the alleged Tocquevillian optimism about the future of taxes and government growth as democracy—the franchise in his times, social rights in ours—advances. The second part of this essay deals with Alan Peacock's interpretation of Tocquevillian optimism about the future of democratic fiscal policy, which Peacock termed as «Tocquevillés Cross». The third part of the paper describes the critiques of the Ricardian tradition of fiscal optimism under a democratic regime with extended franchise. In the next section, decision making is analysed as a semi-rational process based on cultural values. There follows an analysis of the changes in voters' preferences and their influence on economic growth and income redistribution through taxes and government expenditure. In particular, this section focuses on the behaviour of the rationally irrational voter, that is, cultural changes, such as those analysed by Alexis de Tocqueville in the second volume of his Democracy in America and the new developments in the theory of «preference falsification». Section 6 addresses the final thoughts before a brief section concludes.

2. TOCQUEVILLE'S APPARENTLY RICARDIAN VIEW OF TAXATION UNDER DEMOCRACY

The purpose of this essay is to point out Tocqueville's pessimism on fiscal matters under political democracy. Yet, his views on politics need to be examined in the context of the classical Ricardian tradition. Classical economic thinking had seldom implied political liberalism. Free and open markets implied economic enfranchisement, but political enfranchisement was entirely another matter: «the psychology of the classical economists dictated the exclusion of the poor from the franchise, because the natural covetousness of the poor would bring social disorder if allowed to express itself politically» (Grampp Reference Grampp1948; Hutchison Reference Hutchison1966). The main reason for excluding the poor from voting—the lack of possession of property—had been explained by James Mill in his «Essay on Government» (1820) and the classical economists seldom questioned this principle. However, their hope in the possibility of progress for all led them to believe that the moral improvement associated with material prosperity would tame the desire for high taxes and redistribution. From David Hume, to Adam Smith, John Ramsey McCulloch and John Stuart Mill, all believed that perhaps the extension of voting rights could be compatible with an economic system based on private property in the near future (Grampp Reference Grampp1948; Winch Reference Winch1979, pp. 84-85). David Ricardo's assertion that the extension of the franchise «would be the means of so rapidly increasing the knowledge and intelligence of the public» (Peacock Reference Peacock1992, p. 43) suggested that enfranchising ever larger segments of the population would be a secure way towards social stability without greatly jeopardising the property of those who paid taxes. Alexis de Tocqueville apparently shared this optimism and deepened the analysis of possible future fiscal harmony under democracy. In addition to the educational effects of democracy, he found another argument for the extension of enfranchisement without jeopardising the economy's fiscal capacity in the trend towards income equality. His optimism regarding the beneficial effects of the extension of property included a profound change in the attitude and hopes of the poor. In his Second Report on Pauperism, he posed these questions: «as soon as they own a small patch of land, even a very small one, don't you notice how their ideas change and their customs are modified? Is it not obvious that together with property they acquire the hope in the future?»Footnote 1

Alan S. Kahan also points out Tocqueville's initial optimism:

Tocqueville adopts the more optimistic perspective found in Montesquieu, Smith and Say. For Rousseau, inequality inevitably grows ever greater. Tocqueville modified Rousseau's account with a depiction of equality at the end of the story (Kahan and De Tocqueville Reference Kahan and De Tocqueville2010, p. 92).

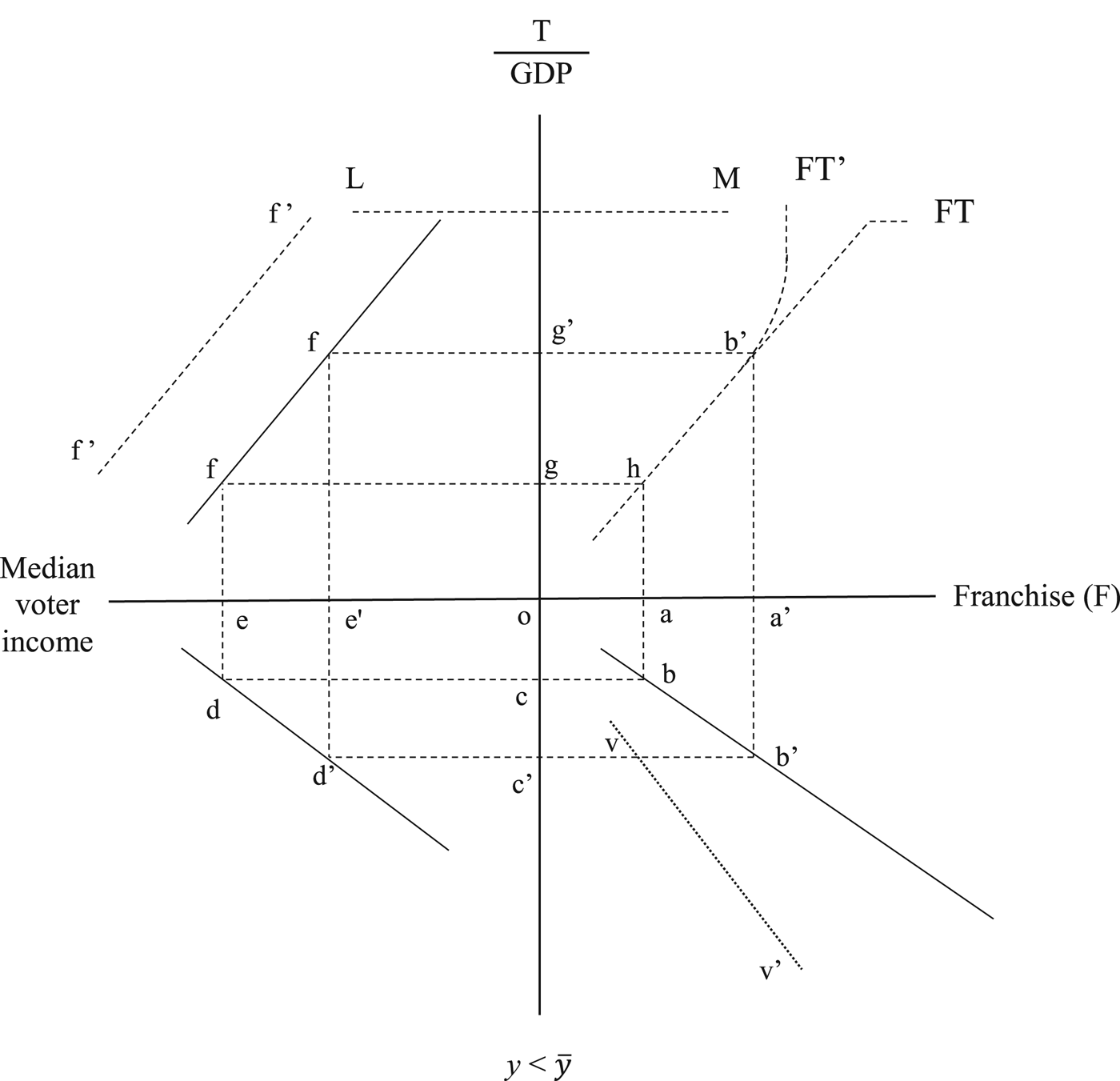

This is exactly what Alan Peacock described in his «Tocqueville's Cross» almost four decades ago (Peacock Reference Peacock and Giersch1983) (see Appendix). In Peacock's model, the level of taxation (as a percentage of gross national product (GNP)) is made to depend on the percentage of the enfranchised population. With a given extension of suffrage and a given distribution of income, we can identify the median-voter income that, in turn, determines the amount of taxes over total product. An extension of suffrage would increase the number of voters below median income, and consequently, the levels of taxes over GNP as well. However, Peacock's interpretation of the Tocquevillian view includes a limit (such as LM in the Appendix) to the growth of taxes and public expenditure. As suffrage extends, taxes and expenditure would rise. Redistribution would increase as poorer voters are enfranchised, but Peacock seems to imply that sooner or later they will come to realise that further demands will jeopardise the economy's fiscal capacity, and consequently, its growth and stability. New voters' moderation could stem from the extension of property and their realisation that as taxes increase, they will also be included within the taxable population. It is also possible that the drop in total output associated with higher taxation would discourage redistribution as public revenues decrease (the possibility of an increase in public indebtedness is not considered here), or that a fall in productivity or in labour force participation (which tend to decrease mean income relative to the income of the median voter) could reduce further pressure to increase taxes.

The historical experience with the extension of the franchise, however, seems rather to point in the opposite direction. Four decades ago, Meltzer and Richard (Reference Meltzer and Richard1978, pp. 111, 116) concluded that «We can be confident […] that the average growth rate of government tax collections has been larger than that of real output for nearly two centuries» and they explained these two different trends because «Government grows when the franchise is extended to include more voters below the median income or when the growth of income provides revenues for increased redistribution». Nevertheless, there is no firm consensus on the matter. The extension of the franchise as a cause of increased public expenditure has been questioned on the basis that not all government expenses are redistributive. Husted and Kenny (Reference Husted and Kenny1997, pp. 54-82), for example, argue that if the income effect of the newly enriched—to avoid higher taxation—overrides the substitution effect of new public services at lower prices for the poor, extending the vote could have an effect different from that predicted by Meltzer and Richard (Reference Meltzer and Richard1978). Nevertheless, the study of Husted and Kenny refers to an extremely specific political environment—the Civil Rights movement of the USA and the fight to remove racial impediments to voter participation as a result of the Voting Rights Act of 1964—and, in any case, it does confirm the tendency of the extending vote to increase redistributive public expenditure in most cases. In a more general sense, tax rates in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries today, as a share of gross domestic product (GDP), are between 20 and 40 per cent. By contrast, preindustrial societies rarely succeeded in taxing more than 5 per cent of GDP (Meltzer and Richard Reference Meltzer and Richard1983; Aidt et al. Reference Aidt, Dutta and Loukoianova2006; Aidt and Jensen Reference Aidt and Jensen2009; Kivanc and Pamuk Reference Kivanc and Pamuk2013). The extension of the vote has translated into increases of T/GNP for long periods of time and the current pressure for social rights and entitlements has led policy makers to even higher taxes, public expenditure and debt over long periods of time. Economic growth, for example, could induce a change in income distribution a la Kuznets with a drop in median income; voters could discover the «magic» of translating the tax burden to future generations through government indebtedness, or they could choose to increase spending on health, retirement and other social security programs as an insurance against future income changes. Alternatively, growth in income and equality could propitiate the formation of pressure groups that push for income redistribution in their favour with the aggregate result of higher taxation and government expenditure. As Sam Peltzman (Reference Peltzman1980, p. 285) pointed out, contrary to intuition, «the leveling of income differences across a large part of the population—the growth of the ‹middle class›—has in fact been a major source of the growth of government in the developed world over the last fifty years». In sum, as suggested by Tocqueville's Democracy (Vol. II), the relationship between democracy and redistribution could resemble the function FT′ shown in Figure 1. Instead of the more optimistic FT suggested by Peacock (see Appendix), median income and the pressure to redistribute increase with taxes as a percentage of total product beyond a certain level of enfranchisement.

FIGURE 1 Two paths of fiscal expansion under democracy.

3. A MORE REALISTIC VIEW OF FISCAL DEMANDS UNDER DEMOCRACY: THE ROLE OF CULTURE and PREFERENCES

Tocqueville's initial optimism on fiscal matters under democracy seems, at best, to need a second view. His background as a social scientist made him look at the complexity of taxation as a key element in political analysis. In his Old Regime and the Revolution, he stated that «there is almost no issue of public interest which does not derive from taxes or end up in taxes» (cited in Swedberg Reference Swedberg2009, p. 254). The inquiry into taxation—especially «the destructive effects of the taille»—played a central role in his explanation of the Revolution (Gannet Reference Gannet2003, pp. 54-55). But Tocqueville's concerns about political economy went beyond taxation. He had studied Jean-Baptiste Say's Cours complet d’économie politique in depth and had read Malthus—especially the Essay on the Principle of Population—in detail. He was familiar with the views of Ricardo, Malthus, Senior, J.S. Mill and McCulloch. According to Michael Drolet (Reference Drolet2003, p. 67), the main influence of the classical economists on Tocqueville was both Say's stress on the importance of self-interest rightly understood and the principle that «Say's political economy served to reveal the most basic questions surrounding national character». Tocqueville was also influenced by Christian views of political economy—especially those of Villeneuve-Bargemont and his Économie politique chrétienne—that appeared in France and elsewhere at the time in opposition to the principle of the supposedly unqualified self-interest of the British classical school: «Tocqueville also understood that there were limits to self-interest…He shared this conviction with Smith» (Drolet Reference Drolet2003, pp. 78-79).

Despite his Ricardian confidence in the «knowledge and intelligence» of the newly enfranchised, Tocqueville was familiar with the complexity of fiscal policies and, consequently, his view of the growth of taxation under democracy was not as optimistic as many think. He certainly believed in the extension of property's civilising effects,Footnote 2 but he immediately recognised that the demand for redistribution by the new voters could be fuelled by the fact that under democracy «they notice a mass of hitherto unfelt wants which cannot be satisfied without recourse to the resources of the state. For that reason, public expenditure increases with civilization, as enlightenment spreads, taxes rise» (De Tocqueville Reference De Tocqueville1965a, p. 109). Anticipating Adolf Wagner's law, Tocqueville predicted that growing political influence by lower income voters would increase the demand for public goods and services, and additionally would make rulers more inclined to redistribute: «In democracies, where the sovereign power belongs to the needy, only an increase in their prosperity will win that master's good will; almost never can that be done without money» (De Tocqueville Reference De Tocqueville1965a, p. 109)Footnote 3. This, however, is not all. He also foresaw the dynamics of tax increases implied in progressive taxation «because taxes cannot touch those who vote for them or because they are assessed in a way to prevent that. In other words, a democratic government is the only one in which those who vote for a tax can escape the obligation to pay it» (De Tocqueville Reference De Tocqueville1965a, p. 108). In addition, the reputation of democracies for fiscal frugality frequently hides a biased distribution of income:

«The parsimony of democracy toward its chief functionaries has caused it to be credited with very economical inclinations, which it does not possess. It is true that democracy hardly provides its rulers with a decent living, but it spends huge sums to succor the needs or facilitate the pleasures of the people. That is a better use of taxes, not an economy. In general, democracy gives little to the rulers and much to the ruled. The opposite occurs in aristocracies, where the state's money especially benefits the class in control of affairs» (De Tocqueville Reference De Tocqueville1965a, p. 110).

And, finally, democracies may fail in their attempts to be frugal because they simply do not know how to do it: «There is one other, final reason which makes democratic government more expensive than others. Sometimes a democracy wishes to economize its outlay, but does not succeed in doing so, because it has not learned the art of being economical» (De Tocqueville Reference De Tocqueville1965a, p. 110).

It seems, therefore, that Tocqueville's general fiscal optimism was tempered when he reflected more carefully on the complexity of democracy. Tocqueville's apparently opposing views, however, are not so contradictory. He identified micro and macroeconomic tendencies pushing simultaneously for and against fiscal moderation as democracy and suffrage expanded: the «opulence» and proprietorship stimulated by a liberal political system would be an obstacle to fiscal expansion, but changes in preferences and the growing political complexity would accelerate redistributionFootnote 4.

It is true that «one area that has not found many commentators is Tocqueville's views on economics» (Swedberg Reference Swedberg2009, p. 1), yet he developed a systematic analysis of preference formation that impinges directly on the economics of political markets and fiscal attitudes. Tocqueville's background in economics was not that of a specialist. His formal training was limited—the new discipline of political economy was not yet in the curriculum when he studied law in Paris in the 1820s—but his readings of the classics were extensive. Swedberg (Reference Swedberg2009, p. 82) notes Tocqueville's hostility to the extreme formality and abstraction of the Ricardian arguments, but he was able to mix intuition with a thorough knowledge of the literature. This was especially true in Volume II of his Democracy, which appeared in 1840. Volume I had been published 5 years earlier. It addressed the more general problems related to the emergence of democracy, and when Tocqueville finished it, he concluded: «The details of this huge picture are in shadow, but I can now see the whole and form a clear idea of it» (De Tocqueville Reference De Tocqueville1965a, p. 216). The details of his analysis were dealt with in Volume II. In the second volume, he focused on customs, mores, feelings, mentality, behaviour and institutions (Jardin Reference Jardin1984, pp. 202-222)Footnote 5. Eduardo Nolla (Reference Nolla and de Tocqueville2012, pp. xlvii-cxlix) describes Tocqueville's analysis in the second part of his Democracy in America as a «philosopher in action». Tocqueville's system of ideas appears here as framed by the inevitability of democracy's progress, the extension of rights (Furet Reference Furet1985, p. 119) and the cultural revolution created by equality (Nef Reference Nef1985; Kaledin Reference Kaledin and Guellec2005). In his own words, he «should be understood as a cultural philosopher who looked to culture and institutions shaped by culture as the key to understanding political and social worlds» (Elazar Reference Elazar1999, p. 207). In effect, when Volume II appeared in 1840, John Stuart Mill (Reference Mill1859, p. 60) concluded «that nothing on the whole comparable in profundity had yet been written on Democracy».Footnote 6 Cultural patterns and sentiments—such as the desire for equality, for example—conditioned economic behaviour.Footnote 7 This is especially relevant for his analysis of betterments in political democracy—such as the extension of the franchise—and whether they translate into more economic liberties, such as reductions in taxes. Evaluation of fiscal freedom, however, has always been subject to cultural influences (De Jassay Reference De Jasay1985) that could bias most voters' decisions concerning fiscal options, not necessarily in favour of lower taxation; in addition, socially held values in favour of low taxes must rely on a general social acceptance of the liberal market economy with a reduced public sector. However, even assuming that most free voters clearly identify material prosperity and growth as linked to lower taxation, and that freedom from excessive taxes is an essential component of their cultural heritage, it remains to be seen under what circumstances the politically free voter would favour moderate fiscal policies instead of more intense state intervention, higher taxes and more public restrictions to free markets. A «rational» voter may want to restrict his own economic liberty through higher taxes even at the cost of giving up a certain degree of material prosperity and economic growth.

In summary, for a more politically free and participatory democracy with universal suffrage to become a less redistributive economic system, in addition to some immunity to special interests, firstly, a cultural framework within which liberty is generally preferred over equality, and secondly, well-informed voter behaviour that does not purposely restrict voters' own economic liberty, are required.Footnote 8

4. DECISION-MAKING AS A SEMI-RATIONAL PROCESS BASED ON CULTURAL VALUES

Although the interest in the role that culture plays in understanding the political and social worlds was pioneered by Tocqueville, there is nowadays a renewed emphasis on institutions as the rules of the game (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2012; Algan and Cahuc (Reference Algan and Cahuc2010); Tabellini Reference Tabellini2008, Reference Tabellini2010); that is, the external framework that shapes individual behaviour, preference and culture. As discussed below, culture, values and preferences were decisive as the framework for Tocqueville's pessimism regarding the future of taxation growth under democracy. The view of decision making as a semi-rational process based on cultural values has recently taken central stage in economic analysis. Denzau and North (Reference Denzau and North1994) explained the analytical challenge:

«The rational choice framework assumes that individuals know what is in their self interest and make choices accordingly. Do they? … the diverse performance of economies and polities both historically and contemporaneously argues against individuals really knowing their self interest and acting accordingly. Instead people act in part upon the basis of myths, dogmas, ideologies and ‹half-baked› theories…In order to understand decision making under such conditions of uncertainty we must understand the relationships of the mental models that individuals construct to make sense out of the world around them, the ideologies that evolve from such constructions, and the institutions that develop in a society to order interpersonal relationships».

The concepts mentioned by Denzau and North (Reference Denzau and North1994)—ideologies, myths, dogmas, «half-baked» theories, mental models or social customs—overlap with one another and are slippery enough as to make them difficult to handle in economic analysis. Yet, they are crucial to understand the generation of collective preferences. All have in common that they are based on beliefs and values, that is, generalised ethical valuations and non-rational explanations that individuals prefer to hold in a culture, and can apply to natural phenomena—such as the rhythm of the tides or the celestial orbits—or to the internal organisation of the community, such as for example, the optimum way to tax voters' income.Footnote 9 This «subjective» view of values is not new; Alexis de Tocqueville also pointed to the unquestioned role in collective action and political life of dogmatic beliefs—«opinions which men take on trust without discussion» (De Tocqueville Reference De Tocqueville1965b, pp. 229-230)—that glue together a community. His analysis implies that institutions inculcate cultural norms:Footnote 10 Dogmatic beliefs stemmed from the new democratic institutional order—that Tocqueville had addressed in Volume I of his Democracy—and constitute the general framework of the state of mind, culture and moeurs, that explain general behaviour, which he analysed in Volume II of Democracy (Harrison Reference Harrison1985; Harrison and Samuel Reference Harrison, Samuel, Harrison and Huntington2000). Tocqueville also showed how social behaviour that springs from individualism evolves from being one of calculus into being one of custom: «At first it is of necessity that men attend to the public interest, afterward by choice. What had been calculation becomes instinct. By dint of working for the good of his fellow citizens, he in the end acquires a habit and taste for serving them» (De Tocqueville Reference De Tocqueville1965b, pp. 274−275). What is important for our purpose, however, is that the values embodied in an economic culture may or may not favour liberty, including economic liberty, as a basic trait of their «habits of the heart». That is to say, economic liberty—and low taxation/low government expenditure—may very well not be a highly valued moeur of many cultures.

5. THE «PASSION FOR EQUALITY» AS A CASE OF RATIONAL IRRATIONALITY

Even in the absence of cultural biases against economic liberalism—economofobia, as this attitude is referred to by Hayek (Reference Hayek1944, p. 222)—another element is required for political freedom and democracy to transform themselves into less economic coercion and taxes, and that is that the average well-informed voter decides in favour of free market-oriented politicians and moderate taxation when casting his vote. This was another aspect of democracy—the drift towards unconditional equality—that became the basic factor in Tocqueville's shift to fiscal pessimism. If the cultural environment and the prevailing values are in favour of freedom, and the spread of economic knowledge is such that most electors—at least the well-informed minority—are aware of the close connection between increases in material prosperity and advances in democracy, why would a voter decide against free market politics and in favour of equality, redistribution and higher taxes? Alexis de Tocqueville advanced an answer to this question in the second volume of his Democracy in America.

The underlying problem, then and now, is to ascertain whether there is a systematically biased error in public opinion in favour of redistribution. This is exactly the problem Alexis de Tocqueville addressed in chapter 1 (part II) of Democracy's second volume entitled «Why Democratic Nations Show a More Ardent and Enduring Love for Equality than for Liberty». He wrote: «Do not ask what singular charm the men of democratic ages find in living as equals or what special reason they may have for clinging so tenaciously to equality rather than the other advantages society offers» (De Tocqueville Reference De Tocqueville1965b, p. 170). He clearly foresaw the biased preference for redistribution and the loss of liberty that democracy would bring:

«Democratic people always like equality, but there are times when their passion for it turn to delirium… [it] seeps into every corner of the human heart, expands and fills the whole. It is not use telling them that by this blind surrender to an exclusive passion they are compromising their dearest interest; they are deaf. It is no use pointing out that freedom is slipping from their grasp while they look the other way; they are blind, or rather they can see but one thing to covet in the whole world» (De Tocqueville Reference De Tocqueville1965b, p. 170).

In Tocqueville's opinion, the passion for equality, and consequently for redistribution, is «ardent, insatiable, eternal and invincible» (De Tocqueville Reference De Tocqueville1965b, p. 171), but besides fiscal blindness, there could be another reason for the preference for equality over economic freedom. In addition to Tullock's rational ignorance (Tullock Reference Tullock1967, pp. 102-102), and the lack of economic knowledge on the part of the voter, there are also economic anomalies, that is, individual irrationalities, cognitive errors, committed by voters even if they understand the discipline and have sufficient information.Footnote 11 The anomalies approach, however, does not take into account preferences for or against redistribution on the part of the voter; it simply focuses on mistakes made when choosing.Footnote 12 For a deeper insight into voters' preference with respect to government expenditure and taxes, a further step in the analysis is necessary: the introduction of a utility function with parameters representing preferences for equality and for freedom. «What is at issue is the empirical importance of the altruistic, publicly interested goals of rational actors determining legislative and regulatory outcomes» (Kalt and Zupan Reference Kalt and Zupan1984, p. 279). Following Tocqueville's intuition regarding the changes in preferences under democracy, modern scholars are now opening the black box of preferences towards ideology, redistribution, economic freedom and communality that allow for a more complete view of voters' behaviour in democratic systems. That view, as Tocqueville pointed out, also included psychic (Ashenfelter and Kelley Reference Ashenfelter and Kelley1975, p. 698) or sociological (Tollison and Willet Reference Tollison and Willet1973, p. 61) benefits in the analysis. In Paul Rubin's words: «It may be that in addition to tastes for policies individuals also have tastes for feeling that they themselves have influenced those policies» (Rubin Reference Rubin2001, p. 331)Footnote 13. Phillip Nelson (Reference Nelson1994, p. 92) found an explanation for this behaviour in the herd effect; the tendency of each voter «to fit in with desired friends and associates», and Kalt and Zupan (Reference Kalt and Zupan1984, p. 281) added two further motives to the ideological preferences of voters:

«First, the successful promotion of an ideology may give individuals the satisfaction of knowing that they have concretely improved the lot of others. Second, even if the pursuit of ideology has no effect on others, individuals may derive satisfaction from ‹having done the right thing›».

There is, however, an additional element to be taken into account. This is when individuals make economic decisions—such as the pursuit of equality at the cost of freedom and economic growth described by Tocqueville in democracies—that go against the voter's own interest. This was the contribution of the rational irrationality view. By incorporating purposeful mistakes into the analysis of irrational decisions, voter outcomes can be viewed as the result of a market; a market for redistribution, as developed by Bryan Caplan (Reference Caplan2007). The utility function behind the demand for redistribution implies a preference for economic freedom—and consequently, for material wellbeing and economic growth as well. It also embodies, however, an alternative preference for higher taxation (i.e. a loss of material wealth) under the assumption that higher taxes, income redistribution and tighter governmental control of the economy satisfy the ideological loyalty of a substantial minority that, although aware of the material cost of coercion, is willing to give up a certain amount of wealth and growth in exchange for ideological satisfaction and expression of loyalty. Given the small impact of each individual's vote on the total electoral outcome, «letting emotions or ideology corrupt our thinking is an easy [and inexpensive] way to satisfy such preferences» (Caplan Reference Caplan2007, p. 14).

Individual voters will not give up economic liberty if the price of renouncing low taxation is high, that is, if the number of voters is small and the chance of influencing final aggregate outcome in terms of material prosperity forgone is high. The price of redistribution (paying higher taxes), however, will go down as the franchise is extended and more decision makers (voters) will decide on the final collective outcome. In this case, coercion and redistribution demanded (forgone economic freedom) will increase. Since the choice between irrationality and material wellbeing (growth) is governed by preference (feel-good ideology) and prices, Bryan Caplan's model represents a market for irrationality, that is, a process of choosing rational irrationality: «in real world political settings the price of ideological loyalty is close to zero. So, we should expect people to satiate their demand for political delusion, to believe whatever makes them feel best» (Caplan Reference Caplan2007, pp. 132−133). An individual voter could reach a satiation point equilibrium without practical consequences for himself. This model, then, predicts that as the price of ideological loyalty approaches zero, the demand for taxes and public expenditure will move towards whatever equilibrium makes a voter feel best in ideological terms. Almost two centuries ago, however, Tocqueville foresaw such habits of the heart, moers and passion as the feel-good preferences described by Caplan (Reference Caplan2007). They were passions associated with the democratic psyche and the cultural frame of mind that placed equality above liberty as democracy's supreme value. Democracy's drive to equality was unavoidable for the democratic man. Even if he were aware of its cost, he was not able and willing to escape:

«Nobody is so limited and superficial as not to realize that political liberty can, if carried to excess, endanger the peace, property, and lives of individuals. But only perceptive and clearsighted men see the dangers with which equality threatens us, and they generally avoid pointing them out. They see that the troubles they fear are distant and console themselves that they will only fall on future generations, for which the present generation hardly cares» (De Tocqueville Reference De Tocqueville1965b, p. 270).

6. TOCQUEVILLE'S FISCAL VIEWS RECONSIDERED

Tocqueville distrusted the inevitable drift of history towards democracy because democracy would bring about a passionate search for equality and, as Nolla (Reference Nolla and de Tocqueville2012, p. cxxvi) points out, «the principle of equality (which is the principle par excellence since it comes down to the principle of identity) ends up by imposing a structure in which reason and confrontation are lacking» and this, in turn, would transform the struggle for equality into an endless drift without a final stable settlement; «the more equal men are, the more insatiable their longing for equality» (De Tocqueville Reference De Tocqueville1965b, p. 289). In the end, Tocqueville concluded that the «undisciplined passions of democracy, and especially the unintentional cultural revolution created by the advance of equality, would not strengthen but rather undermine freedom» (Kaledin Reference Kaledin and Guellec2005, p. 47). This had, at least, two fearsome consequences for the future of modern democratic societies. One was political, the other one was strictly fiscal. At the end of his Democracy—in a chapter entitled «What Sort of Despotism Democratic Nations Have to Fear»—Tocqueville accurately described the drive towards state despotism associated with the invasion of the individual's realm in modern society:

«I am trying to imagine under what novel features despotism, may appear in the world. In the first place, I see an innumerable multitude of men, alike and equal, constantly circling around in pursuit of the petty and banal pleasures with which they glut their souls. Each one of them, withdrawn into himself, is almost unaware of the fate of the rest [] Over this kind of men stands and immense, protective power which is alone responsible for securing their enjoyment and watching over their fate. That power is absolute, thoughtful of detail, orderly, provident and gentle. It would resemble parental authority if, fatherlike, it tried to prepare its charges for a man's life, but on the contrary, it only tries to keep them in perpetual childhood. [] It provides for their security, foresees and supplies their necessities, facilitates their pleasures, manages their principal concerns, direct their industry, makes rules for their testaments, and divides their inheritances. Why should it not entirely relieve them from the trouble of thinking and all the cares of living?» (De Tocqueville Reference De Tocqueville1965b, p. 375).

Under egalitarian democracy we face the risk that «governments extend its embrace to include the whole of society» (De Tocqueville Reference De Tocqueville1965b, p. 375), but this also implies an expansion of taxes and public expenditure. The experience of the following two centuries after Democracy in America was published confirms Tocqueville's pessimism. Writing more than half a century later, Joseph Schumpeter (Reference Schumpeter and Swedberg1991, p. 116) predicted that the continuous increase in taxation and government expenditure could finally put an end to redistributive market economies:

«If the will of the people demands higher and higher public expenditures, if more and more means are used for purposes for which private individuals have not produce them, if more and more power stands behind this will, and if finally all parts of the people are gripped by entirely new ideas about private property and the forms of life—then the tax state will have run its course and society will have to depend on another motive forces for its economy than self-interest. This limit, and with it the crisis which the tax state could not survive, can certainly be reached. Without doubt, the tax state can collapse».

7. CONCLUSIONS

In the face of our current debt crisis and the continuous pressures to extend government expenditure based on social rights and entitlements, the insights of Alexis de Tocqueville on the drive towards equality, even at the cost of economic growth, are illuminating. In Tocqueville's times it was the extension of suffrage that was under consideration. What is at stake today is whether universal social rights and the level of taxation and public expenditure they bring about are compatible with sustained productivity gains, economic growth and expanding fiscal capacity.

The optimistic view of the future of taxation under democracy frequently assigned to Tocqueville needs to be reconsidered. It is true that his Democracy in America includes an implicit limit to fiscal growth as the franchise spreads. This, however, is no more than a hope for the beneficial effects of prosperity and the extension of proprietorship. In reality, Tocqueville foresaw a much more realistic and pessimist future under democracy.

Schumpeter's premonition may sound excessive today. The tax state did not collapse. This, however, was only due to the fact that technical advances and the improvements in the quality of capital (both physical and human) have, during long periods of time, translated into substantial gains in productivity that have allowed for greater fiscal capacity and income redistribution. Yet nothing guarantees that in the race of productivity against taxes the former will end up as the winner. Productivity gains depend on a complex and uncertain set of causes, while the drive for equality—as Tocqueville predicted—continues unabated.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Professor Leandro Prados de la Escosura and Professor Carlos Rodriguez Braun for their support and encouragement in this project.

APPENDIX

The function T/GNP represents the total amount of taxes as a percentage of national product, and is made to depend on the percentage of the enfranchised population (Figure 2). For a percentage of, say, 30 per cent (point a on the F axis) the given income distribution identifies a given percentage of voters (oc on the y < ÿ axis) with incomes below average. The extent of suffrage and the distribution of income identifies median voter income (oe) and this, in turn, determines the amount of taxes over total product (such as og on the T/GNP axis).

The resulting abdfh equilibrium implies that if the franchise were extended, say, to oa', the percentage of voters with income below average would increase to oc' and the median voter's would decrease to c' with an increase in taxes to g'. In summary, Peacock derived a function such as FT explaining the level of taxes and public expenditure (as a percentage of GNP) as a result of the extension of suffrage rights among the adult population. As the percentage of the enfranchised population goes up, a given income distribution determines the percentage of voters below the median level of income (y < ÿ), and this, in turn (dd′) establishes the median voter income. As the franchise spreads, so does the number of poor voters and, consequently, median income (e to e′) and the pressure to redistribute (f to f′) both increasing with them taxation as a percentage of total product (g to g′). A similar result would be achieved with a shift from bb′ to vv′, for example, that lowers the concentration of income and increases the number of poor voters, or with a shift of ff to f′f′ that increases the pressure to redistribute for a given drop in median voter income.