Introduction

From the beginning of the twenty-first century, many European countries have witnessed an increase in hostility towards gender equality, which is a fundamental aspect of contemporary social citizenship. In countries such as Italy, France, Spain, Bulgaria, Poland, Croatia, Slovakia, Slovenia and Austria, public debate on gender-related issues has been dominated by a trend of anti-genderism, i.e., a ‘resentful mobilization against pluralism and “political correctness”, which are perceived as instituted by “gender ideologues”’ (von Redecker Reference von Redecker2016, 2). This mobilisation has extensively used terms like gender theory and ideology of gender.

While nowadays the term ideology of gender has become well known across Europe, its actual meaning remains quite obscure, especially to people who are not familiar with gender studies. It can be defined as a rhetorical device employed to contest the concept of gender itself, as well as any gender-positive intervention aimed at denaturalising the traditional sexual order. Since its inception, the anti-gender crusade has increasingly opposed what Diane Richardson (Reference Richardson2017, 219) defines as the ‘struggles over sexual citizenship in different geo-political contexts’ (e.g., women's reproductive rights, gender equality, sexual education, same-sex marriage). The goal is to delegitimise feminist and LGBTQ+ stances and to oppose the implementation of anti-discrimination policies and gender mainstreaming approaches.Footnote 1 Anti-gender positions are common also among right-wing populist parties that are gaining more and more power in many European countries. As a result, in several countries this ideological backlash has already put a brake on the implementation of the gender mainstreaming approach that has informed European policies and recommendations for the last two decades.

As mentioned above, Italy is one of the countries that has recently experienced such an anti-gender backlash. Indeed, it has been a particularly fertile ground for anti-gender actors who have fiercely opposed the introduction and expansion of gender sensitivity in contemporary Italy. This trend puts Italy in the broader European context of antagonism and hostility towards women's and LGBTQ+ people's rights. While in recent years the birth and development of anti-gender movements have already been the focus of national and international research (Garbagnoli and Prearo Reference Garbagnoli and Prearo2018; Kováts and Põim Reference Kováts and Põim2015; Kuhar and Paternotte Reference Kuhar and Paternotte2017), the present contribution attempts to read this phenomenon through the notion of transculturality, drawn from the work of Wolfgang Welsch (Reference Welsch, Featherstone and Lash1999). Here the concept of transculturality is applied to anti-genderism with a twofold aim: on the one hand, to understand the success of the anti-gender movement; on the other to show the fallacy of its ideological assumptions and its inadequateness in interpreting modern complex societies. To do so, this article begins by providing an historical overview of how the anti-gender movement has developed transnationally across Europe, in order to set Italian anti-genderism in its broader international context.

The anti-gender movement: a transnational phenomenon

In the last two decades anti-gender sentiments have flourished throughout Europe, generating ‘national manifestations of a trans-nationally circulating movement against “gender ideology”’ (Paternotte and Kuhar Reference Paternotte, Kuhar, Kuhar and Paternotte2017, 2). The anti-gender movement can be interpreted first as a transnational phenomenon, in the three layers of meaning of the term trans-national identified by Emma Bond (Reference Bond2014). As she writes, firstly

the trans-national suggests a stretching or going beyond the confines of national boundaries (be that in cultural, spatial or temporal terms). Secondly, it privileges a sense of flexibility … thus identifying a fundamental sense of exchange that is inherent in the term. And thirdly, speaking of cultural production, the trans-national is usually associated with a fluidity of constructed styles and practices. (Bond Reference Bond2014, 416)

This definition of the trans-national seems particularly suitable to studying the development of the anti-gender movement and narrative across Europe, starting from its invention within the Vatican, which itself has a transnational influence.

From the Vatican to Europe

As several scholars point out (e.g. Garbagnoli Reference Garbagnoli2016, Reference Garbagnoli, Kuhar and Paternotte2017; Garbagnoli and Prearo Reference Garbagnoli and Prearo2018; Kuhar and Paternotte Reference Kuhar and Paternotte2017), the notion of gender ideology was initially created by the Vatican during the mid-1990s as a counter-strategy when international institutions such as the United Nations and the European Union first began to implement a gender mainstreaming approach, following the 1994 UN International Conference on Population and Development held in Cairo, and the Fourth World Conference on Women held in Beijing in 1995. The Vatican read this as a first step towards the legitimation of abortion and homosexuality and expressed its concern by condemning the very use of the term gender ‘as a strategic means to attack and destabilise the natural family’ (Paternotte and Kuhar Reference Paternotte, Kuhar, Kuhar and Paternotte2017, 9). As Judith Butler notes, the Vatican denounced gender ‘as a code for homosexuality’ and also ‘insisted that the [Beijing] platform language return to the notion of sex, in an apparent effort to secure a link between femininity and maternity as a naturally and divinely ordained necessity’ (Reference Butler2004, 182). As this request was considered anachronistic and thus rejected, the Holy See started an ideological war against gender-mainstreaming policies. Since then, this opposition has employed a discourse based on a strategic reconfiguration of gender itself, which conflates both feminist and LGBTQ+ issues, to attack progressive policies and to renew conservative views on sexual and reproductive rights. As underlined by Sarah Bracke and David Paternotte,

The usefulness of ‘gender’ in ‘gender ideology’ is precisely that it brings together a number of concerns high on the agenda for conservative Catholic activists: rejection of a wide range of reproductive rights for women (notably abortion), rejection of same-sex marriage and homosexual parenting, attachment to particular roles for men and women and rejection of the transgression of these roles, sex education, and the endorsement of particular – heteronormative – norms about sexuality. Gender as an analytical concept provides the analytical and political connections between these different topics: it renders ‘issues’ into a coherent vision. (Reference Bracke and Paternotte2016, 148)

Thus, since the mid-1990s the Vatican's counter-strategy has adopted a rhetoric that successfully turned gender – both as a term and as a concept – into a contested site, and has gradually worked to demonise all stances against patriarchy and heteronormativity that have been brought about by second- and third-wave feminism as well as by LGBTQ+ activists. Although the anti-gender discourse has largely depicted gender as a code for homosexuality, this rhetoric has been used extensively in many European countries to undermine women's rights along with the rights of LGBTQ+ people.

Although developed within Vatican boundaries, since its origins this attack against the ‘gender agenda’ (O'Leary Reference O'Leary1997, 11) has drawn on transnational literature published by overtly pro-life and ultra-Catholic foreign authors. Notable examples include the American journalist Dale O'Leary, the Belgian priest and emeritus professor Michel Schooyans, the German critic Gabriele Kuby, the Belgian-American essayist Marguerite Peeters, and the French psychoanalyst and priest Tony Anatrella, all of whom have published books warning about the hidden agenda of the ideology of gender which circulated transnationally after being translated into different languages.Footnote 2 Some of the above-mentioned authors also actively contributed to writing the fundamental text of the war against gender, namely the Lexicon: Ambiguous and Debatable Terms Regarding Family Life and Ethical Questions.

Published in Italian in 2006 by the Pontifical Council for the Family and later translated into several languages, the Lexicon is an encyclopaedic dictionary made up of 90 entries on gender-related issues, such as sexuality, bioethics, and homosexuality. Published under John Paul II's tenure, the Lexicon reaffirms Wojtyla's notorious struggle against the ‘culture of death’ allegedly created by the legitimisation of abortion, and stigmatises non-heterosexual relationships in a section written by Anatrella.Footnote 3 In spite of its strong ideological discourse, the Lexicon was promoted as a document that ‘informs about the true content of words, about the true reality which must inform their usage and seeks to shed light on the sense of some terms or expressions which are hardly understandable’ (Lopez Trujillo Reference Lopez Trujillo2002). Overall, this text set the groundwork for a narrative which went beyond Vatican borders and transformed gender into a ‘symbolic glue’ (Kováts and Põim Reference Kováts and Põim2015) which unified local manifestations of gender antagonism into a well-organised transnational movement. Its discourse crossed borders throughout Europe, fostering a mutual influence among reactionary forces using a language based on shared discursive strategies to manipulate perceptions of gender.

Due to space constraints, it is not possible to give a full historical account of the development of the anti-gender movement and discourse transnationally. However, it must be stressed that academic literature has attested to its presence in many European countries, including Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Slovenia, Spain, as well as Russia (Kováts and Põim Reference Kováts and Põim2015; Kuhar and Paternotte Reference Kuhar and Paternotte2017). It is worth noting that the notion of an ‘ideology of gender’ did not find immediate international success during the first decade of the twenty-first century. The situation drastically changed in 2012–2013, when Pope Benedict XVI used this term in one of his public speeches while France was debating the so-called Mariage pour Tous (Marriage for All) bill, promoted by then Minister of Justice Christiane Taubira to legalise same-sex marriage. In those years, France saw the emergence of groups which strenuously opposed, first, gender-sensitive education in schools and public universities, and later, Mariage pour Tous. Since then, the French anti-gender movement has grown exponentially and it has been led by La Manif Pour Tous (Protest for All, hereafter LMPT), composed of more than 40 associations which organised several rallies against the bill.Footnote 4 As Michael Strambolis-Ruhstorfer and Josselin Tricou highlight (Reference Strambolis-Ruhstorfer, Tricou, Kuhar and Paternotte2017, 80), although LMPT did not succeed in stopping the legal recognition of same-sex marriage in France, ‘these activists have successfully stalled, thwarted or diminished a number of reforms, including granting lesbian couples access to assisted reproductive techniques, teaching gender equality in schools and reducing the administrative and medical burdens on transgender people’.

The enormous appeal of LMPT not only caused a serious backlash against gender-oriented policies in France, but also generated an international echo which has deeply influenced the transnational development of the anti-gender movement. It comes as no surprise, then, that LMPT's discourse and methods have easily permeated Italian society, strongly affecting the country's debate over legislative and educational measures on gender-related issues.

From Europe to Italy

Sara Garbagnoli (Reference Garbagnoli, Kuhar and Paternotte2017, 154–160) identifies three sorts of actors who have been crucial to the spread of anti-gender sentiments throughout Italy: the Vatican, new anti-gender groups such as Sentinelle in piedi and LMPT Italia; and radical fringes of Catholic associations and far-right political parties.Footnote 5 Relying on the above-mentioned international texts and on the experience of their French counterparts, these heterogeneous groups of actors contributed to the reconfiguration of gender as an artificial conceptual category which has shaped postmodernity.

Several scholars highlight that gender detractors adapted an already existing discourse to the local Italian context (Bernini Reference Bernini2014; Garbagnoli Reference Garbagnoli, Kuhar and Paternotte2017; Lalli Reference Lalli2016). This narrative is grounded in a distortion of the very essence of gender studies, the field's claims and theoretical frameworks. This discursive reconfiguration presents gender as ‘the Trojan horse of “ideological colonisation” denying a biological truth and produced by a powerful lobby’ (Garbagnoli Reference Garbagnoli2016, 192), and gender mainstreaming as a political conspiracy, a totalitarian project supported by institutions like the European Union. In Italy, this narrative has mainly used terms like ideologia del gender, teoria del gender, genderismo, or simply gender. It has been employed strenuously to stop the bill on same-sex unions (the so-called Cirinnà bill) and the draft law on homo-transphobia, and to interfere with the implementation of the 2015 reform of the education system, also known as La Buona Scuola (The Good School).Footnote 6 Although this reform merely follows the directives of the Istanbul Convention in seeking to prevent gender-based violence through a gender-inclusive education, it has been defined by its detractors as the ultimate means for the ideologia del gender to teach homosexuality in schools. This led to a counterattack developed through a variety of actions ranging from email-bombing the Minister of Education to the creation of anti-gender websites. Among other material, these online platforms have provided lists of children's books that allegedly promote gender. The attack on gender-sensitive literature caused the ban of many of the listed books in areas governed by right-wing parties and inspired acts of intimidation directed against gender activists.Footnote 7 The astonishing success of the anti-gender movement in Italy resides both in the country's strong Catholic tradition, as well as in the discourse used to spread moral panic about the policies mentioned above. For this reason, the following section presents the main features found in the Italian anti-gender narrative through an analysis of online material found on one of the most popular anti-gender websites, osservatoriogender.it (hereafter Osservatorio, i.e., Observatory).

Main elements of the anti-gender narrative

Created in 2015 by one of the most active Italian anti-gender groups, Famiglia Domani, Osservatorio aims to provide parents with supposedly trustworthy information on how to protect their children from the ideologia del gender. To explicate the key elements of its discourse, my analysis focuses on the website's subsection Capire il ‘Gender’ (Understanding ‘Gender’), which attempts to explain what gender ideology is.Footnote 8 In my study, I use the methodological approach of feminist Critical Discourse Analysis, which brings together the tenets of gender studies and Critical Discourse Analysis (hereafter CDA). Feminist CDA is a particularly suitable theoretical framework for analysing how anti-genderism is manifested discursively, because it investigates the reproduction of gender-based asymmetries and inequalities in discourse (Lazar Reference Lazar2007, 142). Following the discourse-historical approach developed by Ruth Wodak and Martin Reisigl (Reference Wodak, Reisigl, Schiffrin, Tannen and Hamilton2001), I analyse the anti-gender narrative through four types of discursive strategies: (1) nomination strategies, (2) predicational strategies, (3) argumentation strategies, and (4) perspectivation, framing, or discourse representation.

‘Gender’ and ‘ideology’

Osservatorio reproposes a conceptualisation of ideologia del gender that is common to anti-gender discourses across Europe. First and most crucially, it creates a new discursive category (ideologia del gender) which is vilified through specific strategies that convey longstanding gender-based prejudice. The first strategy employed to demonise gender is a perspectivation which pivots on the strategic use of the term ideologia del gender. Perspectivation can be defined as a strategy through which ‘speakers express their involvement in discourse and position their point of view in the report, description, narration, or quotation of discriminatory events’ (Wodak and Reisigl Reference Wodak, Reisigl, Schiffrin, Tannen and Hamilton2001, 386). In this case, concepts like gender studies, queer movement, and gender mainstreaming undergo a process of ideological distortion and are discursively reframed within the newly invented category of gender theory. Both nouns used in the expression ideologia del gender have a strategic role in this narrative. First, the term ideologia is chosen to indicate the rigid and programmatic agenda that this theory supposedly conceals, and to identify it as a systematic set of ideas which aims at controlling social conduct. Second, the term gender is maintained in English. This word is neither easily understandable nor immediately recognisable in a country where gender studies have not become a mainstream part of the education system. Thus, the use of a foreign and exotic term helps to conceptualise gender theory as a discipline imposed from the outside on Italian culture and its Catholic tradition.Footnote 9 Moreover, when Osservatorio attempts to clarify what gender means, it misleadingly reduces the concept to a misappropriated foreign grammatical category in order to validate heteronormativity and negate any distinction between sex and gender. In fact, the website states that

Those who promote gender theory replaced the word ‘sex’ with ‘gender,’ an ambiguous ideological term which serves the implementation of their subversive programme. The term gender has been adopted in the English language which also has a neutral gender, unlike the Italian language where we find only 2 grammatical categories, male and female. Hence the use of this term, which perfectly suits an ideology that postulates the infinite variability of the individual's sexual orientation.Footnote 10

This passage shows how gender studies are reframed through a fallacious discursive strategy which alters their meaning. In fact, this academic field of enquiry does not substitute sex with gender but analyses gender and sex as two distinct concepts which are in relation with each other, and which intertwine in the development of identities. Moreover, by referring to grammar norms, the discourse used establishes an equivalence between gender and neutrality which plays on the trope of gender ideologues denying sexual differences between women and men. It is also worth noting that this website suggests that Marx and Engels are the founding fathers of gender, and that gender theory is ideologically grounded in Marxism and socialism (e.g. ‘The theoretical background to what would later be called “gender theory” goes back to socialist ideology and, in particular, the ideas expressed by Friedrich Engels’).Footnote 11 This interpretation has been used especially in countries such as Poland which experienced the Communist regime (Graff and Korolczuk Reference Graff, Korolczuk, Kuhar and Paternotte2017), but it also recurs in anti-gender narratives at transnational level, because it allows the establishment of a similarity between genderism and socialism as two totalitarian ideologies.

Nature and freedom

On the website, gender is also demonised through several argumentation strategies, i.e., strategies which are used in discourse to justify positive or negative attributions (Wodak and Reisig l Reference Wodak, Reisigl, Schiffrin, Tannen and Hamilton2001, 386). In the text under analysis, these strategies are based on a linguistic ambiguity that plays on two main concepts: nature and freedom. An example of this can be found in the following passage:

Often we commit the error of thinking that what is natural is the same as what a person instinctively feels they want to do. But, in reality, instincts and impulses are what people and animals have in common. But while animals lack intelligence and freedom, and thus follow the law of instinct, man is intelligent and free, and thus is guided by the law of reason. … Man … has his own rational nature, that is, he is an intelligent and free being, able to fulfil the purpose that he uncovers in nature. In this sense, there is a purpose that requires a child born male to grow and become a man and feel attracted to women. … Individual freedom consists not of doing what one feels, in an instinctive way, but of achieving one's own specific purpose. … Gender ideology refutes the existence of an inborn ‘human nature,’ rejecting heterosexuality as the authentic destiny of humankind.Footnote 12

In this quote, nature and freedom are presented as the two main arguments which demonstrate the supposed falseness and duplicity of genderism. On the one hand, the website equates nature with heterosexuality, presenting it as the only valid destiny of humankind. Here the concept of nature is used to reaffirm the longstanding dichotomous and hierarchical relationship between heterosexuality and homosexuality. As the former is depicted as the only authentic, inborn, and harmonious sexuality, the latter is implicitly represented as deviant and abhorrent. Such an abnormal sexuality is indirectly linked to the semantic spheres of bestial instinct, error, sin, disease, lack of intellect and morality. In this regard, detractors state that gender ideologues erroneously interpret nature as a person's right to follow all their instincts. In this vision, humans should not surrender to ‘the law of instinct’, which dominates animal behaviour. Conversely, being intelligent and free, people should be guided by ‘the law of reason’.

The second argumentation strategy against gender is based on freedom, which is interpreted not only as the ability to dominate one's bestial impulse, but also as an individual's right to express their opinion. In fact, Osservatorio also states that

Like all theories that go against nature … gender ideology uses an aggressive method, aimed at imposing its vision in a totalitarian way. In this sense, in our country, too, we have witnessed a worrying escalation of intolerance towards those who vindicate the uniqueness and beauty of the natural family [i.e. the traditional family]. Thus, a bizarre paradox arises: the relativistic ideology par excellence, which … demands the recognition of its stances in the name of the principle of non-discrimination, claims to impose its own unquestionable principles with no further debate.Footnote 13

Here ideologia del gender is discursively constructed as a theory that pretends to fight for a non-discriminatory society and to defend freedom, but that actually supports a distorted and personal vision, through an aggressive method aimed at imposing its monolithic principles in a totalitarian way. According to the website, this method has allegedly caused an alarming escalation of intolerance towards supporters of the traditional family. Such expressions show how anti-gender discourse has borrowed a terminology that is typical of liberation movements and progressive stances to sustain homo-transphobic and heterosexist beliefs, and thus to provide a deceitful representation of social power asymmetries in terms of gender. This is particularly visible in the strategies used to portray the actors involved in – and affected by – gender propaganda.

Victims and persecutors

A section of the website identifies the promoters of ideologia del gender through two main strategies, i.e., nomination, which involves the construction and representation of social actors, and predication, which consists in the attribution of ‘negative and positive traits in the linguistic form of implicit or explicit predicates’ (Wodak and Reisigl Reference Wodak, Reisigl, Schiffrin, Tannen and Hamilton2001, 386). Osservatorio defines the actors who allegedly spread this theory as ‘powerful LGBT lobbies’ and ‘equally influential non-governmental organisations’. The site claims that these organisations are more powerful than national governments, because they have succeeded in attracting consensus towards the new ethical paradigm promoted by the gender ideology, and have converted organisations like the United Nations, the European Council, the European Parliament, UNESCO, UNICEF, and the World Health Organisation which nowadays actively promote the gender diktat. Allegedly, the ultimate aim of these forces is to destroy the most important form of microsociety, that is, the heterosexual family. Thus, the allocation of negative traits to gender actors is conducted not only through predication (i.e., powerful and influential), but also through perspectivation. Here perspectivation is used to reframe the actors’ roles, by discursively overturning the victim/persecutor status through a self-victimisation strategy. While as a matter of fact LGBTQ+ people have long endured homophobic and transphobic prejudice, in the anti-gender narrative they become the persecutors of the traditional heterosexual family. Thus, perspectivation is employed to alter and subvert not only the statuses of victim and perpetrator, but also hegemony in terms of material resources and discursive power. As Paternotte and Kuhar note, the victim-perpetrator reversal, along with scapegoating, is strategically used in anti-gender narrative to construct a conspiracy theory (Reference Paternotte, Kuhar, Kuhar and Paternotte2017, 14). These strategies aim not only at weakening the social legitimacy of LGBTQ+ activism and identities, but also at spreading moral panic. To that end, this narrative presents children as the ultimate innocent victims of ideologia del gender, which compromises their childhood and adolescence irremediably, and undermines the fulfilment of their normal heterosexual identity, especially through the education system.Footnote 14 As studied by Kerry Robinson (Reference Robinson2008), childhood innocence is often used as a political mechanism to trigger moral panic which is instrumental to the maintenance of a certain status quo.

As mentioned above, this anti-gender narrative leaked into the Italian socio-cultural context through a repetition of the same tropes which, according to academic literature, have characterised anti-gender discourse at a broader international level. To provide a practical example of the similarities of anti-gender narrative across borders, in the following section I refer to a personal professional experience which took place within the international project G-BOOK – Gender Identity: Child Readers and Library Collections (hereafter G-BOOK).

Anti-genderism across borders: the G-BOOK case

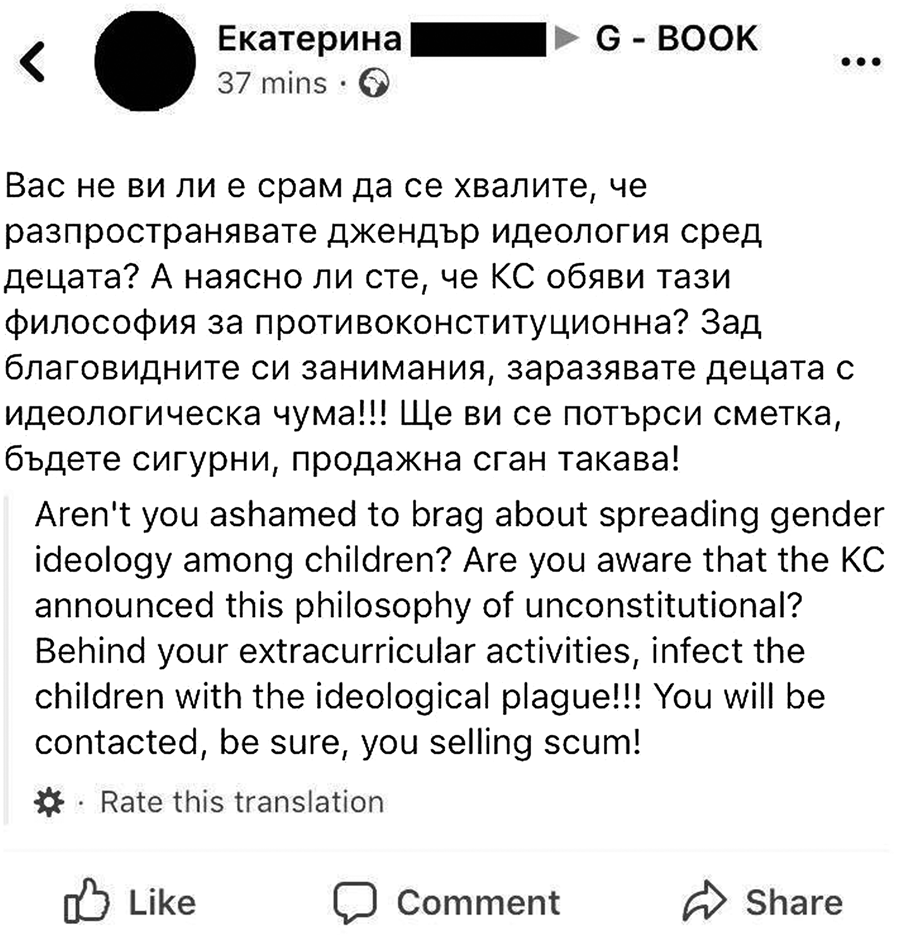

G-BOOK is a project financed in 2017–2019 by the European Union with the aim of promoting gender positive children's literature among six EU member countries.Footnote 15 Among its objectives, there has been the creation of several dissemination activities addressed to children, teachers, and parents to raise their awareness of gender-related issues and stereotypes. These activities took place locally in all the six partner countries of the project, which include Bulgaria and Italy. Although the final phase of the project is still ongoing and thus its reception is still to be fully discussed and analysed, it has been noticed that G-BOOK has met with a certain degree of antagonism both in Italy and Bulgaria. Dissemination activities took place in Bulgaria right after its Constitutional Court declared the Istanbul Convention unconstitutional, and this caused strong opposition to our project. Here gender detractors attacked the G-BOOK Facebook page, posting hateful comments whose narrative recalls the discursive strategies analysed above. Figure 1 serves as an example of this hostile online content.Footnote 16

Figure 1. Bulgarian anti-gender post on G-BOOK Facebook page.

Although no similar content was posted by Italian users, instances of anti-gender sentiment also occurred during the dissemination activities held in Italy. In fact, our events were looked at with suspicion and resistance by some parents who declared themselves against the ideologia del gender, and left the events, especially when LGBTQ+ issues were debated. Moreover, when the project was presented publicly in Forlì, the press conference was guarded by DIGOS officersFootnote 17 sent there to prevent any potential anti-gender turmoil. When asked to comment on these issues, Professor Raffaella Baccolini, the project leader, said that the moral panic spread by anti-genderism undeniably had a negative impact on some G-BOOK events. She also pointed out that, overall, in the last few years MeTRa Centre (see note 15) has often faced reluctance and resistance from several teachers and schools, not only during this project but also in other similar activities aimed at training education staff or at sensitising children on gender-related issues (Baccolini Reference Baccolini2018).

The discursive similarities highlighted in this section confirm the transnational dimension of the anti-gender backlash. The multilayered definition of trans-national developed by Bond (Reference Bond2014) is useful for conceptualising this backlash in terms of scope and consequences. In fact, anti-genderism has sprouted as a reaction to local debates over gender equality policies, but its discourse and methods have travelled across countries, adapting their styles and practices to national socio-political contexts, thus showing what Bond calls ‘a sense of flexibility’ (Reference Bond2014, 416). This sense of flexibility not only characterises the transnational aspect of anti-genderism, but also seems to be embedded in the concept of gender ideology itself. As noted by Stefanie Mayer and Birgit Sauer (Reference Mayer, Sauer, Kuhar and Paternotte2017, 24), anti-gender narrative uses the term gender ideology in a flexible way to indicate a broad subject area, which is composed of feminist and queer theories, women's movements and LGBTQ+ activism, as well as policies which promote a gender-sensitive approach. As analysed above, these concepts are reframed into a new discursive category (i.e., the so-called gender ideology) which is presented as the dangerous Other and as a common enemy. Otherness is therefore redefined in negative terms through a discourse which relies on the ‘politics of fear’ and the ‘arrogance of ignorance’, showing discursive similarities with far-right populist rhetoric (Paternotte and Kuhar Reference Paternotte, Kuhar, Kuhar and Paternotte2017, 14). Like populism, anti-genderism plays on the politics of fear and the arrogance of ignorance to reaffirm what Welsch calls ‘the classical model of culture’ (Reference Welsch, Featherstone and Lash1999, 195). In the next section I discuss this model of culture in relation to the success of the anti-gender movement.

A transcultural phenomenon?

In Welsch's transcultural theory (Reference Welsch, Featherstone and Lash1999, 194–196), the traditional concept of single cultures is a model which juxtaposes an idea of ownness and inner homogenisation with an idea of foreignness and outer separation. It is ‘unificatory’, ‘folk-bound’, and ‘separatory’, and it produces ‘cultural racism’, which is – put in broader terms – aversion to the Other. In the anti-gender narrative, ownness and inner homogenisation pertain to the sexist, heterosexual – and heteronormative – model of culture, while foreignness and outer separation belong to the feminist and LGBTQ+ one. As discussed above, anti-genderism unifies its followers in the war against the representatives of a culture which is discursively designed as outer and foreign. The separatist and exclusive narrative employed in anti-gender discourse may seem in striking opposition to its transnational and transcultural success. In fact, as discussed above, anti-genderism has shown a strong ability to overcome cultural boundaries across European countries. However, the interpretation of this movement through the concept of transculturality raises some theoretical issues. To explain the notion of transculturality, Welsch writes:

The prefix ‘trans-’ in ‘transculturality’ has a double meaning. First, it denotes the fact that the determinants of culture are becoming more and more cross-cultural. So, in the first place, ‘trans-’ has the sense ‘across’. In the long run, however, the cross-cultural development will increasingly engender a cultural constitution which is beyond the traditional, supposedly monocultural design of cultures. So, while having the meaning ‘across’ with respect to the mixed design of cultural determinants, ‘trans-’ has the sense of ‘beyond’ with respect to the future and compared to the earlier form of cultures. (Welsch Reference Welsch, Featherstone and Lash1999, 206)

In this sense, one can affirm that anti-genderism is transcultural because it has travelled across single cultures (i.e., across cultures that are based on different religious beliefs and languages, that defend different nationalistic identities, and which have been shaped by different historical and political events), and because its discourse results from the hybridisation of different cultural traditions, e.g., mixing discursive elements borrowed from Catholicism, secularism, anti-capitalism, and fear of communism. However, anti-genderism cannot be interpreted as transcultural in the second sense of moving temporally beyond single cultures. On the contrary, the spread of anti-gender sentiments across many European areas has caused a cultural backlash in terms of gender equality and inclusivity. In some countries, it has even caused legal backsliding which has reversed the achievements brought by feminist and LGBTQ+ activism.Footnote 18 And yet the transcultural scope of anti-genderism is undeniable. My case here is that the reasons for its success can only be understood by defining anti-genderism for what it essentially is, i.e., an ideology based on patriarchal and heteronormative prejudice. Being a hegemonic superstructure, this patriarchal ideology privileges a discourse of sexism and heteronormativity, which is structural in all societies, with no regard for national and cultural boundaries. Therefore, the systemic ideology on which anti-genderism is based is what enabled its discourse to travel across cultures.

As I have shown throughout this article, the success of anti-genderism resides precisely in its ability to reframe the terms gender and ideology in its own language. In the anti-gender narrative, hence, gender becomes an open site where roles of domination and subordination are discursively revised and reversed. So far, this discursive reversal has already translated into a serious threat to women's and LGBTQ+ people's rights in some European countries, including Italy. Although Italy has not witnessed any legal backsliding yet, the prominent presence in the outgoing Italian government of anti-gender actors from the right-wing, populist party Lega Nord has increased the cultural backlash on issues like LGBTQ+ social citizenship and women's reproductive rights. In fact, when he was Italian Deputy Prime Minister, the Lega secretary Matteo Salvini attacked gender ideology on several occasions. Stances against gender, abortion, and LGBTQ+ rights have also come from Lorenzo Fontana, at that time Minister for the Family and Disability. Moreover, the Italian parliament is still debating a draft law which undermines women's right to abortion, the so-called Pillon draft law (promoted by Lega senator Simone Pillon), and the former Minister of Education Marco Bussetti signed a document which was hailed by many as a way to thwart alleged gender propaganda in schools. Although since late August 2019 Lega has not been part of the current government, the anti-genderism promoted by its spokespersons has had a strong and long-lasting impact on Italian society. The most recent example of support for anti-gender sentiments from the Italian political establishment is the active participation of Salvini, Fontana, Bussetti, and Pillon in the 13th World Congress of Families (WCF), which took place in Verona in March 2019. The Congress gathered many reactionary figures who have long opposed sexual and reproductive rights internationally, like the Russian archpriest Dimitry Smirnov, the Hungarian Minister for the Family Katalin Novák, the Moldovan President Igor Dodon, and the Ugandan Shadow Minister for Social Development Lucy Akello.Footnote 19

The international scope of the WCF also confirms that anti-genderism has a strong sense of flexibility that is reminiscent of Steven Vertovec's definition of the trans-national as the ‘multiple ties and interactions linking people or institutions across the borders of nation-states’ (Vertovec in Bond Reference Bond2014, 416). In the case here at issue, flexibility denotes the striking ability of anti-gender actors to overcome a traditional fixed notion of national space, to push back against progressive stances and policies which strive to promote openness and inclusivity, but which have been rebranded as the attempt to corrupt the morals of contemporary societies. As demonstrated above, anti-genderism has successfully become a transnational phenomenon thanks to the fluidity of the styles, practices, and rhetoric of its promoters, who have mutually influenced one another and effectively adapted a shared discourse to their local contexts, as the Italian case shows.

However, Italy is just one example of how anti-gender narrative has translated into a cultural backlash which reaffirms a separatist and exclusive understanding of culture. Below I conclude my study by discussing how the concept of transculturality can be a useful means to counter the threat posed by anti-genderism.

Conclusion

In Susan Faludi's words (Reference Faludi1993, 12), a backlash ‘is at once sophisticated and banal, deceptively “progressive” and proudly backward’. This article has shown how gender detractors have deceptively reframed their reactionary stances as a progressive fight in the name of freedom, against supposedly despotic policies which are actually informed by gender equality. This sophisticated strategic move has served a more clichéd aim, that is, to freeze European societies’ transition towards the recognition of gender inclusivity as a pillar of democracy and social citizenship. Despite its transcultural diffusion, anti-genderism is to be interpreted as a resurgence of particularism. As Welsch writes (Reference Welsch, Featherstone and Lash1999, 204), in today's complex societies particularisms cannot be ignored, because they create an explosive situation, often redefining themselves ‘through the appeal to cultural identity, to nationalisms, producing hatred, purification actions and war’. As demonstrated in my contribution, the fight against gender equality is played out on ideological ground, and its effects must be identified first in the legitimisation of homo-transphobic and misogynistic sentiments transnationally and transculturally. The anti-gender movement has reframed the European gender-mainstreaming approach as an example of uniformisation which erases heterosexual and cisgender identities. However, gender equality policies aim to question and overcome the effects produced by what Raewyn Connell calls the ‘patriarchal dividend’ (Reference Connell2005, 79), that is, the disadvantage experienced by women and LGBTQ+ people. Contrary to what is propagandised by anti-genderism, these policies do not intend to defeat and destroy more traditional forms of sexual and gender identities. Hence, it is on this ideological ground that the anti-gender movement must be countered through an approach informed by transculturality. As Welsch writes (Reference Welsch, Featherstone and Lash1999, 200), ‘the concept of transculturality aims for a multi-meshed and inclusive, not separatist and exclusive understanding of culture. It intends a culture and society whose pragmatic feats exist not in delimitation, but in the ability to link and undergo transition’. In transitioning to a democracy fully informed by the principle of gender equality, Europe as a whole cannot overlook such a backlash which reaffirms a classical separatist and exclusive model of culture. This means that it cannot ignore the serious influence that anti-genderism has had in the struggle over sexual citizenship in its different geo-political and cultural contexts. In countries like Italy, national NGOs and networks of scholars have lately attempted to develop narrative strategies to counter anti-gender discourse.Footnote 20 However, as this article has pointed out, the anti-gender movement has gained success also thanks to the complicity of national governments in countries like Bulgaria and Italy, although at different levels. Thus, the cultural counterattack against anti-genderism cannot rely only on the will and resources of local progressive actors. As Welsch once again notes (Reference Welsch, Featherstone and Lash1999, 200), when different models of culture collide, there is the need to suggest concepts ‘which are descriptively adequate and normatively accountable, and which – above all – pragmatically lead further’. Therefore, if Europe really wants to achieve gender equality, it must rethink its strategy by developing a cultural antidote which also aims to educate its citizens about the actual meaning of the terms used and the interests at stake in the war played out on the grounds of gender. In order to be effective and realistic, such a cultural antidote should take into account the work done in recent years by scholars and grassroots activists across Europe, and it must strengthen the collaboration among these actors by supporting awareness-raising campaigns and allocating specific funds that would make the study of anti-genderism sustainable both for academic researchers and NGOs. In conclusion, this cultural antidote will be effective only if it embraces the notion of transculturality, by actively promoting a model of culture which shows how different cultures, ways of life, and identities can co-exist without colliding. In an environment dominated by complexity, transculturality is a positive model that will help contemporary societies to transcend monocultural standpoints, and pragmatically move beyond the war against gender equality.

Acknowledgements

I thank Professor Raffaella Baccolini for her input on the cultural backlash produced in Italy by anti-gender discourse, and Professor Roberta Pederzoli for sharing with me her insights into French anti-genderism. Thanks also to Elizabeth Whitaker for discussing with me the similarities between European anti-gender movements and the backlash against women's and LGBTQ+ people's rights in the USA.

Note on contributor

Beatrice Spallaccia is currently Research Fellow and Adjunct Professor of Intercultural and Gender Studies and Diversity Management in the Department of Interpretation and Translation of the University of Bologna, Forlì Campus. In 2017, she completed a Dual Award International PhD (University of Bologna – Monash University) with the dissertation ‘Misogynistic Hate Speech on Social Networks: A Critical Discourse Analysis’. The current foci of her academic research are anti-gender discourses across Europe, narratives and counter-narratives in online gender-based hate speech, and the translation of LGBTQ+ identities in children's and young adult literature.