I spoke that night with a PJ [Justicialista Party] official of the Buenos Aires province. By refusing to join the government, I asked, were the Peronists not flirting openly with behavior that could destabilise the whole system? … My interlocutor calmly replied that when De la Rúa made his offer [to form a government of national unity], the PJ congressional leaders took it to their Radical peers for discussion, only to hear the stunning news that the congressional wing of the president's own party was withdrawing its support for him, and would not take part in any government he might head. (Schamis Reference Schamis2002: 85)

Democracy and political parties go hand in hand, or as Elmer Eric Schattschneider (Reference Schattschneider2009: 1) famously put it, ‘modern democracy is unthinkable save in terms of parties’. Strong parties are fundamental to advancing and stabilizing democracy (Dix Reference Dix1992; Linz and Stepan Reference Linz and Stepan1996), improving governance (Jones Reference Jones2011; Levitsky Reference Levitsky2003), filtering out and isolating extremist and demagogic candidates who might harbour anti-democratic tendencies (Helmke Reference Helmke2017) and taming powerful presidents who might otherwise not resist the temptation to steamroll political adversaries or break democratic rules (Mainwaring and Scully Reference Mainwaring and Scully1995).

Pedro P. Kuczynski (Peru) in March 2018 and Evo Morales (Bolivia 2019) are the most recent cases in a long list of Latin American presidents who have been forced out of office (see online Appendix). The question remains as to whether parties contribute to more stable presidencies or not. Strong parties, such as those that exist in Mexico, El Salvador, Chile and Uruguay, have been around for decades and have historically taken turns in office in both the executive and legislative branches. These countries have some of the most stable governments in Latin America. The opposite is true for Ecuador, Guatemala and Peru, countries with repeated cases of presidential failures and well-known, less-institutionalized parties.

Parties seldom attempt to remove their own presidents since ‘dragging their own leader through the mud’ would render no benefit to the party and its members (Samuels and Shugart Reference Samuels and Shugart2010: 110). Nevertheless, parties may support the ouster of one of its members even if they do not openly and officially acknowledge it, as illustrated by Hector Schamis's (Reference Schamis2002: 85) quote about Fernando de la Rúa's presidential crisis in Argentina in 2001. In this article, we theorize and empirically demonstrate that, whether presidents like it or not, ‘survival’ in office also depends on parties.

Using an updated data set of political events, we are able to test the effects of parties as well as of other politico-institutional, economic and social factors on government duration of all presidents in Latin America between 1979 and 2018. Specifically, we seek to contribute to the studies on presidential instability by examining the role of parties, an actor mostly overlooked by the extant literature on presidential failures. We hypothesize that this is a non-linear relationship: presidents would face the lowest risk when parties are well institutionalized, a moderate risk when parties are weak, and the highest risk when party institutionalization is moderately low.

Current explanations of presidential survival

Previous research has shown executive–legislative relations to be pivotal and that a president's legislative ‘shield’, in the words of Aníbal Pérez-Liñán (Reference Pérez-Liñán2007), plays a central role when it comes to holding onto power or leaving office early (Baumgartner and Kada Reference Baumgartner and Kada2003; Edwards Reference Edwards2015; Hochstetler Reference Hochstetler2006; Kim Reference Kim2014; Kim and Bahry Reference Kim and Bahry2008; Llanos and Marsteintredet Reference Llanos and Marsteintredet2010; Martínez Reference Martínez2017; Mustapic Reference Mustapic, Llanos and Marsteintredet2010; Pérez-Liñán Reference Pérez-Liñán2014; Pérez-Liñán and Polga-Hecimovich Reference Pérez-Liñán and Polga-Hecimovich2017). Furthermore, some studies have focused on whether party system fragmentation and the number of parties in the government have any effect on government survival (Álvarez and Marsteintredet Reference Álvarez, Marsteintredet, Llanos and Marsteintredet2010; Kim and Bahry Reference Kim and Bahry2008; Martínez Reference Martínez2017), but their results are mixed.

The occurrence of different types of events (e.g. presidential scandals, street protests and economic crises) may also be detrimental for a standing chief executive. When cases of corruption, bribery, influence trading and so on directly involving the president or close collaborators go public, the president may struggle to keep allies loyal and thus be more vulnerable to attempts at unseating him or her (Edwards Reference Edwards2015; Hochstetler Reference Hochstetler2006; Kim Reference Kim2014; Pérez-Liñán Reference Pérez-Liñán2007). However, in previous work we do not find enough statistical evidence to link the occurrence of presidential scandals with higher risks of early government termination (Martínez Reference Martínez2017).

Massive protests create scenarios that have proven to be difficult to handle for sitting presidents and may get even more threatening when violent showdowns between protesters and security forces take place (Edwards Reference Edwards2015; Hochstetler and Edwards Reference Hochstetler and Edwards2009; Kim and Bahry Reference Kim and Bahry2008; Martínez Reference Martínez2017). Yet, the effects of anti-government demonstrations are not entirely consistent, as others have failed to find a significant relationship at all (Llanos and Marsteintredet Reference Llanos and Marsteintredet2010).

Economic factors, especially recessions, also create threatening scenarios for presidential survival (Álvarez and Marsteintredet Reference Álvarez, Marsteintredet, Llanos and Marsteintredet2010; Edwards Reference Edwards2015; Llanos and Marsteintredet Reference Llanos and Marsteintredet2010). When it comes to inflation, with the exception of Margaret Edwards’ (Reference Edwards2015) analysis of South America, most studies have failed to uncover a significant association with presidential survival (Álvarez and Marsteintredet Reference Álvarez, Marsteintredet, Llanos and Marsteintredet2010; Hochstetler Reference Hochstetler2006; Hochstetler and Edwards Reference Hochstetler and Edwards2009; Llanos and Marsteintredet Reference Llanos and Marsteintredet2010; Martínez Reference Martínez2017).

After reviewing the literature, we find that the relation between parties and presidential failures has only been addressed indirectly. With the exception of a few case studies (Malamud Reference Malamud2015; Schamis Reference Schamis2002), the literature on presidential failure has not asked whether party institutionalization may influence the risk of failure on its own, beyond the walls of congress. Lastly, we also must ask how the risk of presidential failure is affected by party institutionalization and the occurrence of events such as economic crises, presidential scandals or anti-government demonstrations.

Presidential survival and party institutionalization

In the following paragraphs, we theorize how parties affect chief executives’ survival in four dimensions: long time horizons, close links with society, constraints and in serving as a forum. Finally, we explain why the risk of failure is higher when party institutionalization (PI) is moderately low than when it is high or extremely low.

Long time horizons: the ‘shadow of the future’

As organizations, parties possess longer-term goals than politicians (Alesina and Spear Reference Alesina and Spear1988; Levitsky Reference Levitsky2018; Mainwaring Reference Mainwaring and Mainwaring2018; Stokes Reference Stokes2001). Especially after prolonged periods of time (Mainwaring et al. Reference Mainwaring, Bizzarro, Petrova and Mainwaring2018), institutionalized parties cast a long ‘shadow of the future’ that incentivizes cooperation in forthcoming iterations (Axelrod Reference Axelrod1984), which reduces the breadth and scope of conflicts and thus promotes cooperation. In countries with less institutionalized parties, on the other hand, since there are fewer expectations that the party will exist in the future, actors are more prone to pursue radical goals; thus, conflicts might arise and escalate more easily. Furthermore, parties can reward ‘good’ presidents by sponsoring future nominations and by offering them a political career path after they have stepped down, making presidents less likely to pursue radical courses of action (Alesina and Spear Reference Alesina and Spear1988; Stokes Reference Stokes2001: 113).

Close links with society

Parties develop different types of linkage with civil society (Kitschelt and Wilkinson Reference Kitschelt and Wilkinson2007), some of which are of great importance for government stability. For instance, ruling parties’ linkage with student organizations (Disi Pavlic Reference Disi Pavlic2018: 451) and labour unions (Corrales Reference Corrales2002: 34) have been found to reduce the likelihood of street demonstrations against the government. Furthermore, after long periods of time, parties tend also to be ‘reified’ in the electorate's mind – insofar as people come to regard them as an integral part of the established political system (Janda Reference Janda1980; Randall and Svåsand Reference Randall and Svåsand2002) – as well as having developed ‘stable roots in society’ (Casal Bértoa Reference Casal and értoa2017). This dimension emphasizes how parties may help to reduce the risk of social uprisings and discontent.

Constraints and the balance of power

Well-organized parties may indirectly constrain the influence of chief executives by filtering out those leaders – usually amateur politicians – who do not comply with their goals and principles (Levitsky Reference Levitsky2018: 353), or by curbing the power of their own presidents (Kouba Reference Kouba2016: 438). For instance, political neophytes and outsiders have fewer chances to win the presidency when parties are strong and well-institutionalized than when they are weak (Corrales Reference Corrales2009; Flores-Macías Reference Flores-Macías2010; Samuels and Shugart Reference Samuels and Shugart2010). Gretchen Helmke's analysis, in fact, shows that presidents who belong to immature political parties seem to be prone to launching attacks on the legislature and the courts (Helmke Reference Helmke2017: 112–113, 147). Less institutionalized parties are also associated with the rise of amateur politicians, who are more likely to ‘respond poorly to crises’, and who tend to ‘lack skills in bargaining and negotiation, coalition building, dealing with opponents, handling media, and other areas that are critical to governing and legislating’ (Levitsky Reference Levitsky2018: 352). Furthermore, since strong parties, unlike weak ones, are more likely to withstand a presidential assault, the president may anticipate that well-organized parties may punish her if she behaves opportunistically. As institutionalized parties are more capable of monitoring rulers, parties may act pre-emptively and address potential conflicts with the president even before they happen. All of this disincentivizes confrontation between the president and parties, even her own. That is, the balance of power between the president and (ruling and opposition) parties promotes cooperation and stability; whereas imbalances of power favouring the chief executive reduce incentives for presidents to compromise and bargain, thus heightening political tensions that could threaten presidential survival (Cox and Morgenstern Reference Cox, Morgenstern, Morgenstern and Nacif2002; Kim Reference Kim2014; Shugart and Carey Reference Shugart and Carey1992; Valenzuela Reference Valenzuela2004).

Serving as a forum

Parties serve as forums in which preferences and goals are revealed. As such, parties reduce transaction costs for presidents and party leadership engaging in political negotiations. Furthermore, institutionalized decision-making in which parties play a pivotal role provides better flow of information between the ruler and her or his allies, thus preventing disruptive conflicts within the ruling elite (Boix and Svolik Reference Boix and Svolik2013) and helping smooth executive–legislative relations. As a space for discussion, parties reconcile different and often competing interests (Brownlee Reference Brownlee2007), in turn discouraging intra-party struggles and fostering stability. More importantly, parties contribute to holding the government elite factions together by encouraging accommodation among them and expanding the time horizon, all of which help rulers to ‘survive’ in power longer (Brownlee Reference Brownlee2007).

Our hypothesis: PI's non-linear effects on presidential failures

Our main hypothesis suggests that there is a non-linear relationship between party institutionalization and the risk of presidential failure. That is, at either end, party institutionalization poses lower risks of presidential failure than when party institutionalization is moderately low. We postulate that these outcomes are the result of the combination of two dynamics: parties’ organizational capabilities and time horizons. The former captures whether parties, as constraints and forums, can curb the president's power. Time horizons, on the other hand, refer to how the ‘shadow of the future’ is shorter or longer (prospective), and how the passage of time facilitates the development of linkages with civil society (retrospective). Table 1 depicts how parties’ organizational capabilities and time horizons are associated with different levels of party institutionalization and the risk of presidential failure.

Table 1. Party Institutionalization and the Risk of Presidential Failure

Table 1's upper-left quadrant represents a country with low levels of party institutionalization. In spite of the opposition's willingness to oust the chief executive, a consequence of short-term politics, presidents may remain in office because the opposition is unable to organize and coordinate their removal. It is worth mentioning that there is an inherent degree of instability linked to presidential aggrandizement, as suggested by Pérez-Liñán et al. (Reference Pérez-Liñán, Schmidt and Vairo2019). In the lower-right quadrant, we expect the lowest risk of failure. The large ‘shadow of the future’ makes all players less prone to pursue radical, short-term objectives, and it also discourages opposition parties, notwithstanding their organizational strength, from seriously considering the removal of an incumbent president.

The upper-right (i) and lower-left (ii) quadrants, although similar, represent different challenges for presidential survival when party institutionalization is moderately low. In scenario (i), radical moves such as attempting to oust a sitting president are not expected due to long time horizons, let alone the fact that the opposition does not have the strength to do so. The major potential source of instability is presidents’ risky behaviour and aggrandizement. The lower-left quadrant shows several factors with potentially destabilizing effects. Both parties and the president are prone (and willing) to seek short-term, conflict-triggering goals. But, more importantly, the opposition might be strong enough to actually succeed in unseating the chief executive, which is why the risk of failure is the highest in this scenario.

We also need to address the role PI plays in government stability and political crises (see online Appendix). We theorize that government stability relies on different sources at different levels of PI. In countries with low PI, a stable presidency might be the result of the president's strength vis-à-vis other players. When PI is moderately low, presidents can ‘survive’ in office by establishing ad hoc alliances with key political players, which produces fragile stability. By contrast, in countries with high levels of PI, stability is the result of long-term informal and formal institutions built upon a sufficiently large ‘shadow of the future’. Expecting to play a game against the same players every time also implies that the opposition, even if it could, would be reluctant to take down a rival president, since in the future the tables might be turned and the ousted president might belong to its party.

Party institutionalization changes slowly over time, and not all presidents fail in countries with low or moderately low levels of PI. That is why we argue that party institutionalization is not a direct cause (trigger) of presidential failures, but rather a structural, contextual force that affects the risk of failure more distantly. Triggers for crises may include economic downturns, presidential scandals, massive protests, recalcitrant congressional opposition, presidential attacks on other branches, and other events. But, how does PI indirectly affect the occurrence of a crisis? When party institutionalization is low and moderately low, parties allow outsiders and political neophytes, who lack negotiation skills and experience, to rise. Parties are also unable to constrain presidents who pursue radical goals, thus making constitutional (or interbranch) crises more likely. On the other hand, in countries with high levels of PI, parties are able to curb the presidential authority and force her to negotiate, reconcile divergent interests within parties and coalitions, and provide politicians with political experience and negotiation skills, all of which reduce the likelihood of a crisis.

When crises do occur, we also expect different behaviour from the main political players in different levels of PI. For example, when PI is low, parties either barely exist or are too weak; in any case, they would have a limited (or no) impact throughout the crisis. In countries with moderately low levels of PI, parties either do nothing or, more likely, seek short-term gains from it, which might fuel the crisis even further. By contrast, when PI is high, since parties tend to be risk averse, they are more likely to attempt to contain the crisis or stop it from escalating. Finally, it is also important to answer with whom presidents may negotiate to seek an exit from the crisis when they are in the middle of it. In countries with low levels of PI, since parties are too weak or might not even exist, the president is virtually on her own. When PI is moderately low, because parties lack long-term horizons, they are unwilling to negotiate. Or, in the case of opposition parties, they may want to take advantage of the crisis and, since they are relatively strong, try to force the president out. When PI is high, the president may negotiate an exit with congress or with major parties: thus, we expect a more institutional exit from the crisis.

Survival analysis

We use survival analysis to test the effects of party institutionalization on the risk of presidential failure. This technique estimates the risk of occurrence (or non-occurrence) of specific events during certain periods of times across different units or subjects (Cleves et al. Reference Cleves, Gould and Gutierrez2010; Mills Reference Mills2011; Warwick Reference Warwick1995). The event of interest is the occurrence of a presidential failure, which is when a president is forced to leave office early and is replaced by a civilian government. The ‘risk period’ begins at inauguration day and ends when the president steps down. We use Weibull regressions (proportional hazard parameterization) to estimate which covariates affect the risk of a presidential failure, considering that the president has not experienced the event in previous years. Unlike the study of early government termination in parliamentary systems, few works have employed survival analysis to examine this phenomenon in presidential systems (Edwards Reference Edwards2015; Martínez Reference Martínez2017).Footnote 1

Our sample is drawn from all 18 presidential systems in Latin America between 1979 (which is when the third wave of democratization started) and 30 June 2018. Specifically, we quantitatively analyse 157 administrations: 20 failed presidencies (see online Appendix) and 137 right-censored presidencies, which represents a total of 597 administration-year observations. We must bear in mind that statistical analyses are sensitive to the low number of events per variable (EPV) ratio (Lanser Reference Lanser2015; Vittinghoff and McCulloch Reference Vittinghoff and McCulloch2007). In this case, there are 20 cases of failed presidencies in Latin America. We thus use five predictors per model to avoid seriously compromising our results.

Dependent variable: time to a presidential failure

Our dependent variable represents the time until the event of interest occurs. In this case, we code ‘1’ for the year when a president is forced out of office and is not replaced by a military government, and ‘0’ when the president manages to hold on to power. Presidents who completed their constitutional terms in office, stepped down because of health issues or were still in power by 30 June 2018 are considered right-censored subjects at time t. We can only assume that their survival in office continues beyond time t.

Covariates

Party institutionalization as a novel predictor of presidential failure

The concept of institutionalization has been applied to parties from different perspectives. Even though several works focus on party system-level features (Mainwaring Reference Mainwaring and Mainwaring2018; Mainwaring and Scully Reference Mainwaring and Scully1995; Mainwaring and Torcal Reference Mainwaring, Torcal, Katz and Cotty2006; Panebianco Reference Panebianco1988), which may well apply to individual parties, some scholars have warned about the inadvisability of using the terms ‘party system institutionalization’ and ‘party institutionalization’ interchangeably (Meleshevich Reference Meleshevich2007; Randall and Svåsand Reference Randall and Svåsand2002). Bearing this cautionary note in mind, along with our argument theorized earlier that hinges on parties, we focus explicitly on party institutionalization rather than on party system institutionalization. Specifically, to test our main theoretical argument, we build a new index of party institutionalization based on five indicators of party attributes (party organization, party branches, party linkage with society, party legislative cohesion and distinct party platforms) recorded by the Varieties of Democracies (V-Dem) data set. These five indicators are constructed by V-Dem with a focus on ‘all parties with an emphasis on larger parties, i.e., those that may be said to dominate and define the party system’ (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring and Knutsen2018: 240).

We operationalize party institutionalization as the average of the five party indicators, which were previously normalized and then weighted by a principal-component factor (Acock Reference Acock2013).Footnote 2 The index, which is multiplied by 100 for easier interpretation, varies from low (0) to high (100) levels of party institutionalization.

Presidential scandals and anti-government demonstrations

In addition, based on the Latin American Weekly Report (LAWR 2018), we constructed a new and up-to-date data set that records corruption scandals and anti-government demonstrations at annual intervals (available online). Presidential scandals registers the number of wrongdoings (corruption, bribery, etc.) per year that directly involve the president or her/his inner circle and close collaborators. Likewise, anti-government demonstrations represents the number of public demonstrations per year against the president, the government or her/his policies.

Legislative support

We rely on the variable ‘margin of majority’ of the Database on Political Institutions 2017 (DPI2017), which denotes the number of seats controlled by the ruling coalition divided by the total number of legislative seats (Cruz et al. Reference Cruz, Keefer and Scartascini2018: 13). We multiply this variable by 100 for easier interpretation.

Economic factors

We control for two variables that capture the short-term effects of the shape of the economy. Economic growth is measured as the annual growth rate (%) of a country's GDP ‘at market prices based on constant local currency’ (World Bank 2018). Hyperinflation is coded ‘1’ if the inflation rate is equal or greater than 25% in a given year, and ‘0’ otherwise, based on ‘inflation, consumer prices’ by the World Bank (2018).

Statistical results

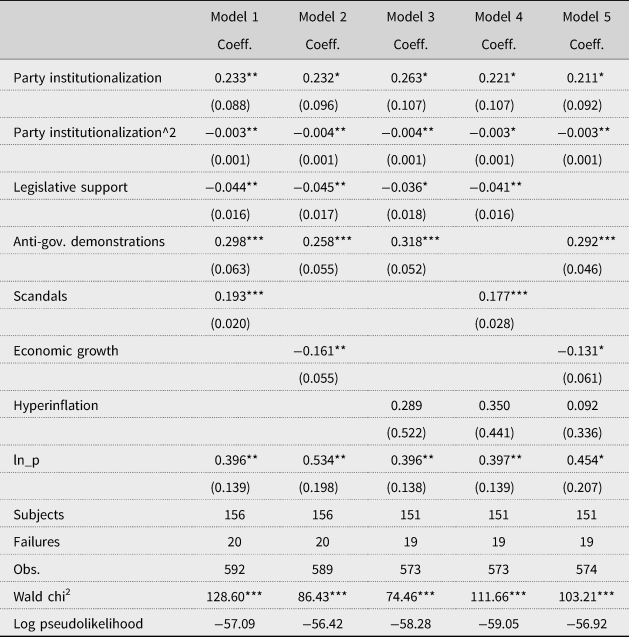

Due to the EPV requirement, we include a maximum of five covariates per regression model. In each of them, we included party institutionalization's linear and quadratic terms as well as other determinants of presidential failures identified in the literature: legislative support, scandals, anti-government demonstrations, economic growth and hyperinflation. Table 2 presents the results of the multivariate regression models. Our findings show that, as hypothesized, party institutionalization is statistically significant and has a non-linear effect on the risk of an interrupted presidency. Since party institutionalization's linear term is positive and its quadratic term is negative in all models, we know that it initially heightens the risk of failure, and then it slowly reduces it. Following the quadratic function, ax2 + bx, we can determine that party institutionalization produces the highest risk at x = −b/2a, after which point the risk starts to decrease (Cleves et al. Reference Cleves, Gould and Gutierrez2010: 180). In model 1, for example, x equals 34.25 (b = 0.233 and a = −0.003), whereas its average across the five models is 34.18. This finding suggests that presidents would face a higher threat to their survival when party institutionalization is moderately low than when their level of institutionalization is low or high, supporting our main hypothesis.

Table 2. Weibull (PH) Regressions

Notes: Robust SE clustered by country in parentheses.

e (Coeff.) = Hazard ratio (HR).

*p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001.

In order to observe the non-linear effect more clearly, we plot the Weibull survival distribution, at mean value of all covariates for different levels of party institutionalization (Figure 1). As expected, when party institutionalization equals 35, presidential survival is (almost) at its lowest. By contrast, when it comes to either strongly (60) or weakly (15) institutionalized parties, presidents face low risks of being thrown out of office. Also supporting our hypotheses, survival is higher at high levels of party institutionalization rather than at low levels.

Figure 1. Survivor Functions for Weibull (PH) Models

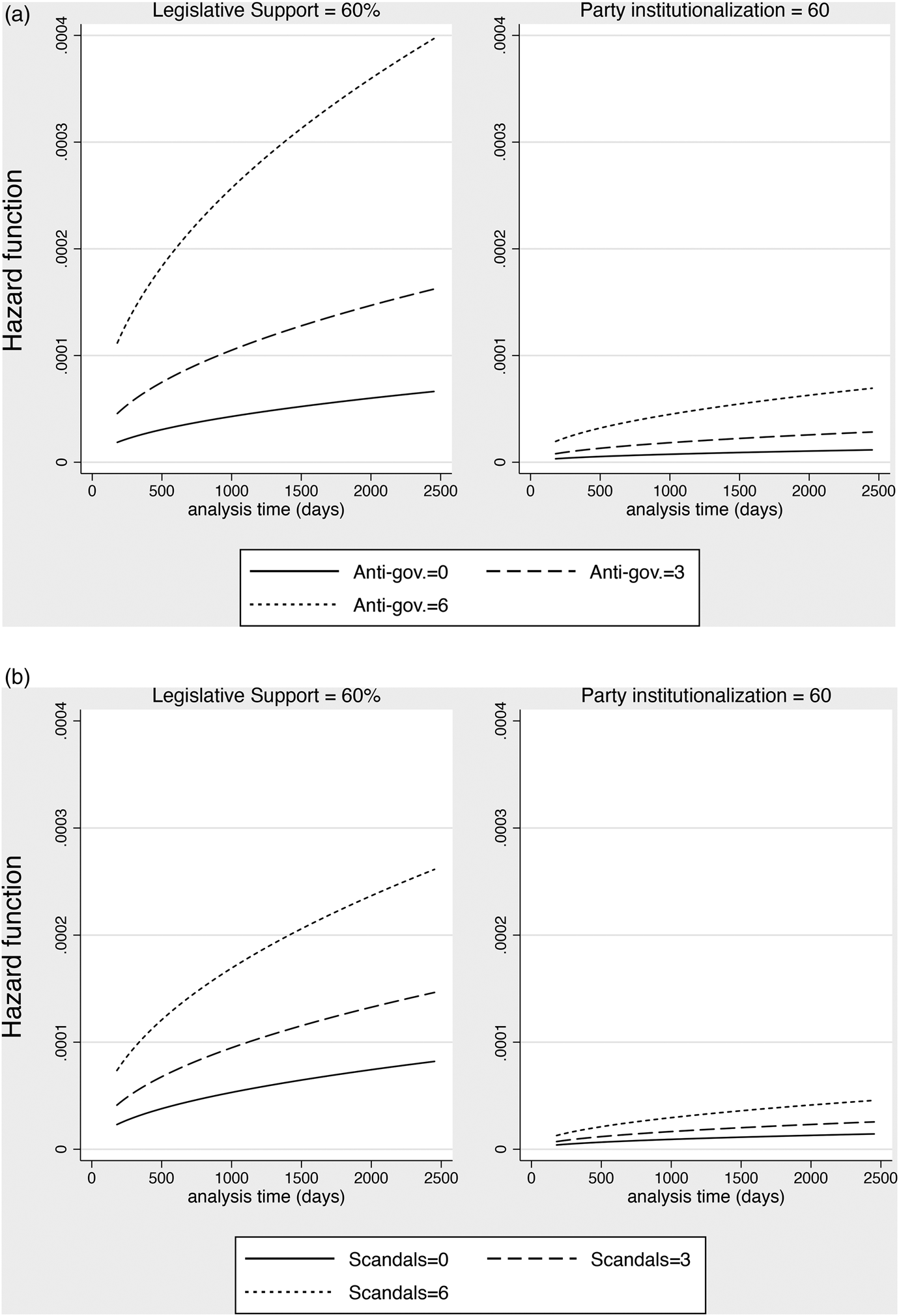

We also want to explore whether the impact of party institutionalization is substantial vis-à-vis other covariates. Since the president's ‘legislative shield’ (Pérez-Liñán Reference Pérez-Liñán2007) is the most consistent predictor of presidential failures found in the literature, we use the variable legislative support as a benchmark to compare the impact of party institutionalization. Figure 2 illustrates this point. We present the hazard functions when legislative support equals 60% of the seats in congress and when party institutionalization is relatively high, that is, 60 points. We compare their effects when also accounting for the occurrence of anti-government demonstrations and presidential scandals. Commanding a significant share of the legislature (60%) may be great news for presidents; nevertheless, Figure 2 shows that ruling a country with strong parties is associated with a dramatically lower hazard of presidential failure, even when facing the same number of street protests targeting the chief executive or presidential scandals.

Figure 2. Weibull (PH) Regression, Legislative Support and Party Institutionalization: Anti-Government Demonstrations (top) and Presidential Scandals (bottom)

Note: Plots based on model 1.

Our results show that the risk of presidential failure also revolves around legislative support. Consistent with prior research, minority presidents are significantly vulnerable to attempts to overthrow them. Furthermore, we also find that the occurrence of both presidential scandals and anti-government demonstrations heightens the risk of failure. On average, every street protest aimed at the executive and scandal raises the hazard of failure by approximately 35% and 21%, respectively (model 1).Footnote 3 On the other hand, when it comes to poor economic performance, results are mixed. Interestingly, even though hyperinflation is associated with a higher hazard, it failed to reach statistical significance in the three models in which it was included. Models 2 and 5 show that economic growth significantly reduces the risk of early government termination.

We performed two robustness checks on our results (not reported here). First, we ran a total of 11 models with five covariates each that included every possible combination of the six independent variables. Party institutionalization was present in 10 models: Its quadratic term was statistically significant in every one of them, whereas the linear term was significant in eight.Footnote 4 Similarly, legislative support, presidential scandals, anti-government demonstrations and economic growth were statistically significant in all seven models in which they were included, whereas hyperinflation was statistically significant in none of them.

Second, we use three other statistical analyses that are appropriate to address time-to-event phenomena: Cox's proportional hazard models, flexible parametric models for survival analysis and mixed-effects parametric survival-time with random effects models. It is worth noting that the mixed-effect parametric model, which is equivalent to controlling for shared frailties, allowed us to account for heterogeneity and unobservable effects at higher levels: presidents who headed several administrations at different points in time (level 2), and countries (level 3). Still, the results did not change. Party institutionalization's non-linear effects on presidential failure still held, and so did the impact of the remaining covariates. Again, hyperinflation was not statistically significant in any single model.

Case studies

In this section, we complement our statistical results with case study evidence in order to explore how the occurrence (or non-occurrence) of certain events – such as economic recessions, presidential scandals or anti-government demonstrations – affects the occurrence of presidential crises and the risk of presidential failure in countries with different levels of party institutionalization: Guatemala (low PI), Ecuador (moderately low PI) and Chile (high PI).

Guatemala

To complement the two South American cases, we examine Guatemala as a case of low party institutionalization (it averages 24.8, our sample's lowest). Guatemala has never witnessed institutionalized parties throughout its history (Jones Reference Jones2011: 19). Party institutionalization in Guatemala fails all across the board: ephemeral organizations, fragile and sporadic linkage with society (Brolo Reference Brolo and Sanabria Arias2012; Dabroy Reference Dabroy2018), party structures dominated by caudillismo and personalism (Azpuru and Blanco Reference Azpuru and Blanco2007), undue influence of money in party organization (Novales Contreras Reference Novales Contreras2014), weak party labels and programmatic attachments (Jones Reference Jones2011: 20), and transfuguismo (defection, Lautaro Rosal Reference Lautaro Rosal2013). High cabinet rotation, fragile and ephemeral legislative alliances and fraught executive–legislative relations have also been common features of Guatemalan politics (Azpuru and Blanco Reference Azpuru and Blanco2007; Lautaro Rosal Reference Lautaro Rosal2013; Lautaro Rosal and Solares Reference Lautaro Rosal and Solares2009).

After decades of authoritarian politics, Guatemala's first democratic power handover occurred when Jorge Serrano took office in 1991. Serrano, a minority president, had little political experience, was known for his ‘autocratic leadership style’ and inability ‘to use negotiations and compromise’, and had troubled relations with a wide array of actors, including the media, trade unions and even the Catholic Church (Christensen Bjune and Petersen Reference Christensen Bjune, Petersen, Llanos and Marsteintredet2010: 169; Villagra de León Reference Villagra de León1993: 118). In May 1993, Serrano found himself isolated and facing a ‘prolonged deadlock in Congress’, where the opposition adamantly chose to battle against him (Christensen Bjune and Petersen Reference Christensen Bjune, Petersen, Llanos and Marsteintredet2010: 165–168). In this scenario, the president carried out an autogolpe (self-coup), also now known as serranazo. Guatemala's parties were unable to reconcile their differences, lacked the legitimacy and were too weak to stop Serrano (Christensen Bjune and Petersen Reference Christensen Bjune, Petersen, Llanos and Marsteintredet2010: 169–172; Villagra de León Reference Villagra de León1993: 123). However, the de facto powers of the Comité Coordinador de Asociaciones Agrícolas, Comerciales, Industriales y Financieras de Guatemala (CACIF, Coordinating Committee of Agricultural, Commercial, Industrial and Financial Associations) and factions of the army fiercely opposed the president (Christensen Bjune and Petersen Reference Christensen Bjune, Petersen, Llanos and Marsteintredet2010). A couple of weeks after the autogolpe, with neither popular nor elite support, and under pressure from CACIF and the army, and other civil society actors, Serrano was forced to resign on 1 June.

With the exceptions of presidents Álvaro Arzú (1996–2000) and Alfonso Portillo (2000–2004), the chief executive's party has never commanded a majority in Congress, yet five consecutive presidents after Serrano fulfilled their terms. Of them, it is worth examining Álvaro Colom's presidency (2008–12). Colom was personally accused – along with his wife and close collaborators – of the murder of lawyer Rodrigo Rosenberg in May 2009. After eight months, an investigation by the United Nations-backed Comisión Internacional contra la Impunidad en Guatemala's (CICIG, International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala) showed that Rosenberg had planned his own murder, exonerating Colom (Erbsen de Maldonado and Barahona Reference Erbsen de Maldonado and Barahona2010: 337). Still, it is rather surprising that no serious attempt to unseat Colom was made in 2009, considering that he did not have a legislative ‘shield’ to rely on, that he endured an economic slowdown in 2009 (0.5%, the lowest since 1986), that several corruption allegations hit his administration (Pallister Reference Pallister2017: 474), and the Rosenberg case. This might be explained by how divided the congressional opposition was during that time (see Lautaro Rosal and Solares Reference Lautaro Rosal and Solares2009: 444), and also by the fact that they were not strong enough to coordinate and organize such a move.

Colom's successor was Otto Pérez Molina (2012–15), a former military officer. His party, Partido Patriota (PP, Patriotic Party), controlled less than 40% of the legislative seats. Troubles for the president began in April 2015 when the CICIG and the attorney general launched a corruption probe called La Línea (The Line), whose main goal was to uncover a major custom fraud network. Six cabinet members and Vice President Roxana Baldetti were forced to step down for their involvement in the case. On 1 September, after months of street protests against Pérez Molina's government and upon the CICIG and attorney general's request, in a landslide vote (132–0–26) Congress stripped the president of immunity from prosecution (Fuenzalida Caris Reference Fuenzalida Caris2018: 99). All PP's legislators who were present voted against Pérez Molina, despite his being the founder of the party (Espina and García Reference Espina and García2015).Footnote 5 Two days after the vote, Pérez Molina resigned. Clearly, the president did not have a reliable and loyal legislative contingent to protect him.Footnote 6 But parties played a minor part and only at the end of this presidential crisis. It is hard to imagine that without the CICIG's involvement and hard work the corruption probe would have succeeded in forcing out Pérez Molina.

In 2015, Guatemala elected a comedian for president, Jimmy Morales, a political outsider who ran on an anti-corruption platform. Like most Guatemalan chief executives, he had a minority status in Congress (11 of 158 legislative seats; Pallister Reference Pallister2017: 475). After two years in office, Morales began to battle the CICIG as corruption investigations loomed over him, his brother, son and close political allies (Masek Reference Masek2019). From September 2018, Guatemala faced a constitutional crisis that pitted the president against the Constitutional Court over Morales’ attempts blatantly to obstruct the CICIG's work. In September 2018, Morales dismissed the Constitutional Court's rule that allowed Iván Velásquez, CICIG commissioner, to re-enter the country after Morales declared him ‘persona non-grata and a threat to public security’, whereas in January 2019 the Constitutional Court overruled Morales’ unilateral decision to terminate the CICIG mandate immediately (Brannum Reference Brannum2019: 274; Masek Reference Masek2019). The president ultimately won the tug of war: the CICIG mandate was not renewed and came to an end in September 2019, and Morales ‘survived’ in office and finished his tenure in January 2020.

The Guatemalan case illustrates four aspects we theorized about countries with low PI. First, presidents are tempted to abuse their power, as Serrano's and Morales’ presidencies show. Second, as we suggested, direct causes of a presidential crisis might be attack by the president on other branches or institutional actors (Serrano and Morales) or corruption scandals (Pérez Molina). Third, parties play, if any, a secondary role when crises come along, thus, ‘survival’ depends on presidential strength vis-à-vis players other than parties and, hence, congress. For Serrano, the real opposition to his attempt to amass power was the CACIF and the army; for Pérez Molina, street mobilizations, the CICIG and the attorney general; and for Morales, the Constitutional Court and again the CICIG. Fourth, parties fail to weed out political neophytes or politicians with no bargaining skills, such as Serrano and Morales.

Ecuador

Ecuador has historically lacked well-institutionalized parties (Coppedge Reference Coppedge1998). Clientelism, fragile bureaucratic structures, short time horizons, deficient internal discipline, feeble commitment to democratic principles, and leaders’ overbearing influence are some of the main features of Ecuadorean parties (Alcántara and Freidenberg Reference Alcántara and Freidenberg2001; Coppedge Reference Coppedge1998; Martínez Reference Martínez2018a; Mejía-Acosta and Polga-Hecimovich Reference Mejía-Acosta and Polga-Hecimovich2011; Pachano Reference Pachano2001). These characteristics, along with a 36.2 average in our PI index, make Ecuador a typical case of moderately low PI (ii).

During 1979–96, five presidents fulfilled their terms in spite of ruling under rather unfavourable economic conditions, such as high inflation and slow economic growth. Through the use of gastos reservados (discretionary spending), presidents allocated resources to specific legislators and even opposition parties in exchange for support, giving rise to what is known as ‘ghost coalitions’ (Mejía-Acosta and Polga-Hecimovich Reference Mejía-Acosta and Polga-Hecimovich2011). This brought important levels of government stability in spite of Ecuador's short-term oriented politics (Mejía-Acosta and Polga-Hecimovich Reference Mejía-Acosta and Polga-Hecimovich2011). The negative effects of moderately low PI and subpar economic conditions on presidential survival were somehow offset by the presence of a stability-inducing device such as ghost coalitions.

However, the 1996 constitutional reforms did away with such arrangements. With no political tools for coalition-building to counter the effects of Ecuador's party institutionalization, presidential tenures were short lived. Between 1996 and 2005, presidents, lacking negotiation or accommodation skills, resorted to fighting political adversaries rather than to cooperating with them. Moreover, Ecuador's parties’ lack of long-term horizons fostered unpredictable, unstable and short-term political dynamics. For instance, due to its minority status, Abdalá Bucaram (1996–97), a self-portrayed political outsider, initially governed with the support of the conservative Partido Social Cristiano (PSC, Social Christian Party), an alliance which crumbled after only three months. Bucaram was deemed by traditional parties to be ‘unwilling, or unable, to negotiate’ (Mejía-Acosta and Polga-Hecimovich Reference Mejía-Acosta and Polga-Hecimovich2011: 81–82). Ultimately, the opposition in Congress, including the PSC, removed him on account of ‘mental incapacity’ after seven months in office.

President Jamil Mahuad (1998–2000) faced many troubles during his short tenure. Conflicts between Mahuad and his factionalized party, Democracia Popular (DP, Popular Democracy), led to DP members resigning from the cabinet and to tense relations with DP legislators (Freidenberg Reference Freidenberg, Alcántara Sáez and Martínez Barahona2003: 416). In 1999, Mahuad's fragile alliance with the conservative PSC broke down over policy differences, which forced him to seek support even from the left (Mejjía-Acosta and Polga-Hecimovich Reference Mejía-Acosta and Polga-Hecimovich2011: 83). In January 2000, while the country faced dire economic conditions, Mahuad was overthrown by middle-ranking military officers during an indigenous uprising, after which Congress quickly appointed the vice president as his replacement.

Lucio Gutiérrez's administration also highlights Ecuador's lack of long-term horizons. Gutiérrez's ad hoc ruling coalition mostly hinged on his party, Partido Sociedad Patriótica (PSP, Patriotic Society Party) and the indigenist Pachakutik Party (PK). The PSP–PK alliance only lasted seven months, after which the PK joined the opposition (Peñafiel Reference Peñafiel2003). In April 2005, when the country faced a constitutional crisis generated by Gutiérrez having charges against former President Bucaram dropped, parties that at one point had sided with the president sought his removal (Martínez Reference Martínez2018a: 333). As a result, Gutiérrez was forced to leave his post and fled the country.

Finally, after 10 years of instability, the third period is represented by Rafael Correa's three consecutive terms in office (2005–17). He dealt with even weaker parties than before (Basabe-Serrano et al. Reference Basabe-Serrano, Pachano and Mejía-Acosta2010: 75; Machado Puertas Reference Machado Puertas2007: 132) and benefited from steady economic growth and the commodity boom (Machado Puertas Reference Machado Puertas2007: 130). Despite the 2010 police insurrection against him, his power was almost unconstrained. Not surprisingly, Correa had an overwhelming influence over the Supreme Electoral Tribunal and Congress (Basabe-Serrano et al. Reference Basabe-Serrano, Pachano and Mejía-Acosta2010; Basabe-Serrano and Polga-Hecimovich Reference Basabe-Serrano and Polga-Hecimovich2012) and even managed to enact a new constitution via a constitutional assembly.

Ecuadorean presidencies shed light on how presidents ‘survive’ or fail in countries with moderately low PI. First, according to our theory, government stability can be reached through ad hoc agreements such as ghost coalitions. However, in the absence of such stability-inducing arrangements, reconciling competing interests among party members and coalition partners (a feature of high PI) became unachievable, especially during 1996–2005. Second, an economic downturn (Mahuad), interbranch conflict (Gutiérrez) or an uncooperative opposition (Bucaram) may trigger a crisis. Once such a chain of events unravels, presidents find themselves beleaguered trying to ‘survive’. However, Correa's long-lasting presidency also shows how presidential aggrandizement, along with the lack of crisis-threatening events and a favourable economic situation, help offset the impact of party institutionalization on presidential ‘survival’. Third, major Ecuadorean actors (the president, parties and party leaders) are driven by short-term rewards, as seen in how parties continually moved from the ruling coalition to the congressional opposition, and vice versa. Fourth, parties were powerful enough to organize, coordinate and unseat a standing president. The presidency of Bucaram clearly exemplifies this attribute, with parties acting quickly against him.

Chile

Chile's institutionalized parties and their large ‘shadow of the future’ have promoted cooperative executive–party–legislative relations.Footnote 7 During the 1990s, presidents and parties from both the left and the right worked together to advance Chile's democracy (also known as ‘consensus politics’). In the 2000s, despite the opposition's wide and public criticism of the executive for its involvement in the MOP-Gate corruption scandal, President Ricardo Lagos (Partido Socialista, PS, Socialist Party) and conservative Pablo Longueira (Unión Demócrata Independiente, UDI, Independent Democratic Union), leader of the centre-right Alianza coalition, continued their negotiations to reform the 1980 Constitution.Footnote 8 As forums, Chilean parties have reconciled divergent interests within political alliances.Footnote 9 Parties have also successfully constrained executive authority through cuoteo and by limiting the president's temptation to overstep his boundaries when it comes to legislative politics (Siavelis Reference Siavelis, Morgenstern and Nacif2002: 95).Footnote 10 Nonetheless, Chilean parties are ‘uprooted’ because of their weak linkage with civil society (Luna and Altman Reference Luna and Altman2011) and have kept fairly close ties with big business (Huneeus Reference Huneeus2014).

In October 2019, Chile's government was hit by estallido social (social unrest), which had not been seen since democracy was restored in 1990. Triggered by a 3.75% subway fare hike in Santiago and fuelled by a deep and generalized dissatisfaction with the political system, millions of people mobilized to protest. On 25 October over a million people marched in what became the largest social demonstration in Chile's history. Looting, riots, massive street protests across the country and showdowns between the police (and armed forces) and protesters left 23 dead in the first month (Deutsche Welle Reference Deutsche2019). President Sebastián Piñera was forced to declare a state of emergency and night-time curfews in several large cities.

Initially, demonstrations were not aimed at the president, but due to excessive government repression and police brutality, protesters began to zero in on Piñera. Piñera's popularity plummeted to 6% in December 2019 (Centro de Estudios Públicos 2019). This is, by far, the lowest presidential approval rating of a Chilean president in the post-Pinochet era.

After weeks of intense anti-government demonstrations, which left downtown Santiago almost destroyed, and as a way to assuage protesters, governing and opposition party leaders stepped in and on 29 November agreed to call for a referendum to replace the Constitution. Even though they did not stop, the frequency and intensity of anti-government demonstrations declined. Chile's major parties found a politico-institutional ‘exit’ from the crisis, one that prevented it from escalating even further. In fact, President Piñera was sidestepped by major parties when agreeing on the constitutional change. He was neither seen nor heard from after the agreement was made public.

To make matters worse, Piñera's ruling coalition did not hold a majority in either the Senate or the Chamber of Deputies. As a minority president, he was even the target of an impeachment accusation, the first in more than 60 years, although it was rejected in the lower house on 12 December 2019. It has been questioned whether the traditional left-of-centre parties’ support for the impeachment was based on a firm intention of unseating Piñera or was just an electoral gambit for their constituencies, knowing that the accusation would fail. Whereas some party members publicly supported the accusation, several party leaders from the centre left have made public statements rejecting the shortening of Piñera's tenure.

Even though the country was not going through an economic recession, Chile's long-lasting inequality paved the way for the social unrest. As Piñera failed to deliver on his campaign promises of tiempos mejores (better times), there was a lingering dissatisfaction with his administration since the economy was underperforming. As if this was not enough, for months President Piñera faced one of the most massive and violent rounds of anti-government demonstrations ever seen in Chile and Latin America; yet, he remained in office.

This case enables us to see how institutionalized parties behave when a crisis takes place. Although less likely, government crises can and do occur in countries with high party institutionalization. Piñera's presidency is an interesting negative case, a near ‘failure’, which gathered together several elements that increase the risk of a failed presidency: divided government, massive anti-government demonstrations and dead protestors. However, as we theorized, the exit from the crisis was funnelled through institutional means. Parties influenced by a large ‘shadow of the future’, from the left and right, reconciled their differences and decided to find a way out together, one that did not involve the chief executive's ouster. It would have been a different story for Piñera if Chile's institutionalized parties had not come to his rescue.

Conclusion

One of the novel contributions of our study is that, whether presidents like it or not, parties are central to them fulfilling their terms in office. We offer a theoretical explanation and empirical quantitative and qualitative evidence of party institutionalization's non-linear effects on the hazard of presidential failure. In all five models, the survival analysis shows that the risk of failure is the highest when PI is moderately low, that is, about 34 in our 0–100 scale. Statistical evidence also suggests that party institutionalization may cushion the impact of other destabilizing events on presidential survival, such as presidential scandals and anti-government demonstrations (Figure 2).

The three case studies help illustrate how government stability and the occurrence of crises vary in countries with different levels of party institutionalization. In Guatemala, government stability was somewhat based on relative presidential strength, but, on the other hand, crises were triggered by presidential aggrandizement. Both are signs of parties being too weak to constrain or balance the power of chief executives. However, other actors took on this role during the presidencies of Serrano, Pérez Molina and Morales: the CACIF, the army, the CICIG and the attorney general. The Ecuadorean case shows how the combination of politics driven by short-term horizons and parties with some degree of organizational capability contribute to government instability (the Bucaram, Mahuad and Gutiérrez administrations). This case also illustrates how stability can be reached through ad hoc agreements (ghost coalitions) and presidential aggrandizement (Correa's presidency). The Sebastián Piñera administration (2018–present) in Chile let us observe how ruling and opposition parties ‘shielded’ a troubled president during the most severe sociopolitical crisis ever seen in the country in the post-Pinochet era. This is a clear illustration of how the expectation of indefinite iterations between the same players – long-term horizons – may contribute to avoid a conflict, such as forcing out a sitting president, which might open the door for retaliation in the future.

Following previous findings, our analyses also show that Latin American presidents must groom a loyal legislative majority if they want to stay in power. Presidents who secure enough partisan support in congress are better equipped to withstand threats to their survival than those who command small, fragile majorities. Furthermore, with an updated data set covering 18 Latin American countries over almost 40 years, we offer new evidence that tilts the scale towards the conclusion that events such as anti-government demonstrations, economic woes and presidential scandals significantly affect the risk that the president will leave office early.

Finally, considering the limitation of the statistical analysis due to the number of events (20 failed presidencies), we acknowledge the need for additional qualitative work to examine more closely the relation between party institutionalization and presidential crises and failures. We propose three avenues of research. First, to explore whether the mechanisms through which institutionalized parties affect presidential failure work as we theorized (see online Appendix). Second, to further clarify the risks faced by presidents in countries with moderately low party institutionalization. And, third, how and under what conditions asymmetrical party institutionalization – especially, between parties in government and opposition – affects presidential survival.

Supplementary material

Replication data are online. To view the online Appendix for this paper, please go to https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2020.18.

Acknowledgements

I thank Juan Carlos Arellano, Raymond Tatalovich, Mariana Llanos and Rodrigo Cuevas for their insightful suggestions. I am also grateful to the editor and the three anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and constructive criticism, and to John Polga-Hecimovich, Carla Alberti and Sergio Toro for their feedback on earlier versions of this work. This research has been funded by FONDECYT Iniciación, Grant No. 11160438.