Introduction

Older Australians constitute 15 per cent of the country's total population and this proportion is set to grow disproportionately by 2025 (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), 2018). As people age, they generally need some practical support to maintain their health, wellbeing and social roles, which can be provided by family members, friends, neighbours and formal service providers (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016). Approximately 80 per cent of older Australians with poor health and reduced levels of physical, psycho-social and cognitive function require additional support from formal services (AIHW, 2015). Of this group, 23 per cent will likely require high-level support within the residential aged care sector (AIHW, 2019a).

People requiring this higher level of support are vulnerable to the quality of the services provided (Department of Social Services, 2014). Recent reviews of the Australian aged care sector found that Australian Residential Aged Care Standards (hereafter Standards) have tended to focus more on service provider systems and evaluation of clinical practices, and less so on resident outcomes and their satisfaction with service provision (House of Representatives Standing Committee on Health, Aged Care and Sport, 2018). Internationally, there have been concerns that the voice of the aged care resident is lost in promoting and appraising service quality (Edvardsson et al., Reference Edvardsson, Fetherstonhaugh and Nay2010; Prince et al., Reference Prince, Prina and Guerchet2013; Kalaitzidis and Harrington, Reference Kalaitzidis and Harrington2018). For more than two decades, aged care advocates have recommended that service standards place more emphasis on the person's unique needs and their quality of life (Kane, Reference Kane2003; Coughlan and Ward, Reference Coughlan and Ward2007; Edvardsson et al., Reference Edvardsson, Fetherstonhaugh and Nay2010; Prince et al., Reference Prince, Prina and Guerchet2013). Older people themselves strongly support this notion, requesting more opportunities to exercise control over their lives, maintain social connectedness, be respected for their uniqueness and to be emotionally supported (Boelsma et al., Reference Boelsma, Baur, Woelders and Abma2014; Jaye et al., Reference Jaye, Tordoff, Butler, Hale, McKechnie, Robertson and Simpson2016; Bangerter et al., Reference Bangerter, Heid, Abbott and Van Haitsma2017; Abbott et al., Reference Abbott, Klumpp, Leser, Straker, Gannod and Van Haitsma2018; Milte et al., Reference Milte, Ratcliffe, Chen and Crotty2018). When these fundamental human needs are met within an enriched care environment (Brooker, Reference Brooker2007), the older person's physical, social and emotional function and sense of wellbeing can be achieved (Chenoweth et al., Reference Chenoweth, Stein-Parbury, Lapkin, Wang, Liu and Williams2019). These aspects of a person-centred service can achieve positive outcomes even in people with significant cognitive decline (Brownie and Nancarrow, Reference Brownie and Nancarrow2013; Chenoweth et al., Reference Chenoweth, Forbes, Fleming, King, Stein-Parbury, Luscombe, Kenny, Jeon, Haas and Brodaty2014; Edvardsson et al., Reference Edvardsson, Petersson, Sjogren, Lindkvist and Sandman2014; Bird et al., Reference Bird, Anderson, MacPherson and Blair2016).

Emphasising a person-centred aged care service represents a significant change from the traditional task-focused clinically driven model of the past (Brooker, Reference Brooker2007; Dewing, Reference Dewing2008). The person-centred approach was pioneered in the United Kingdom (UK) by Kitwood (Reference Kitwood1997; Kitwood and Bredin, Reference Kitwood and Bredin1992), where it has guided aged (social) care service development and quality improvement for more than a decade (Dewing, Reference Dewing2004; Brooker, Reference Brooker2007). The person-centred model has subsequently been embedded in aged care guidelines in several countries. In Australia, the Minister for Senior Australians and Aged Care authorised changes to the Standards for residential aged care services in 2018 (Department of Health, 2018) through the Quality of Care Amendment (Single Quality Framework) Principles 2018 (Wyatt, Reference Wyatt2018). The revised set of Standards, called the Aged Care Quality Standards (Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission, 2019), refers to person-centred service principles in reviewing service quality. The eight Australian Standards (Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission, 2019) are now more reflective of the person-centred model's focus on what the experience is like for the resident, as well as on service delivery and staff work satisfaction (van den Pol-Grevelink et al., Reference van den Pol-Grevelink, Jukema and Smits2012; Brownie and Nancarrow, Reference Brownie and Nancarrow2013; Sjögren et al., Reference Sjögren, Lindkvist, Sandman, Zingmark and Edvardsson2015; Røen et al., Reference Røen, Kirkevold, Testad, Selbæk, Engedal and Bergh2018). The new Standards are: (1) Consumer dignity and choice; (2) Ongoing assessment and planning with consumers; (3) Personal care and clinical care; (4) Services and supports for daily living; (5) Organisation's service environment; (6) Feedback and complaints; (7) Human resources; and (8) Organisational governance.

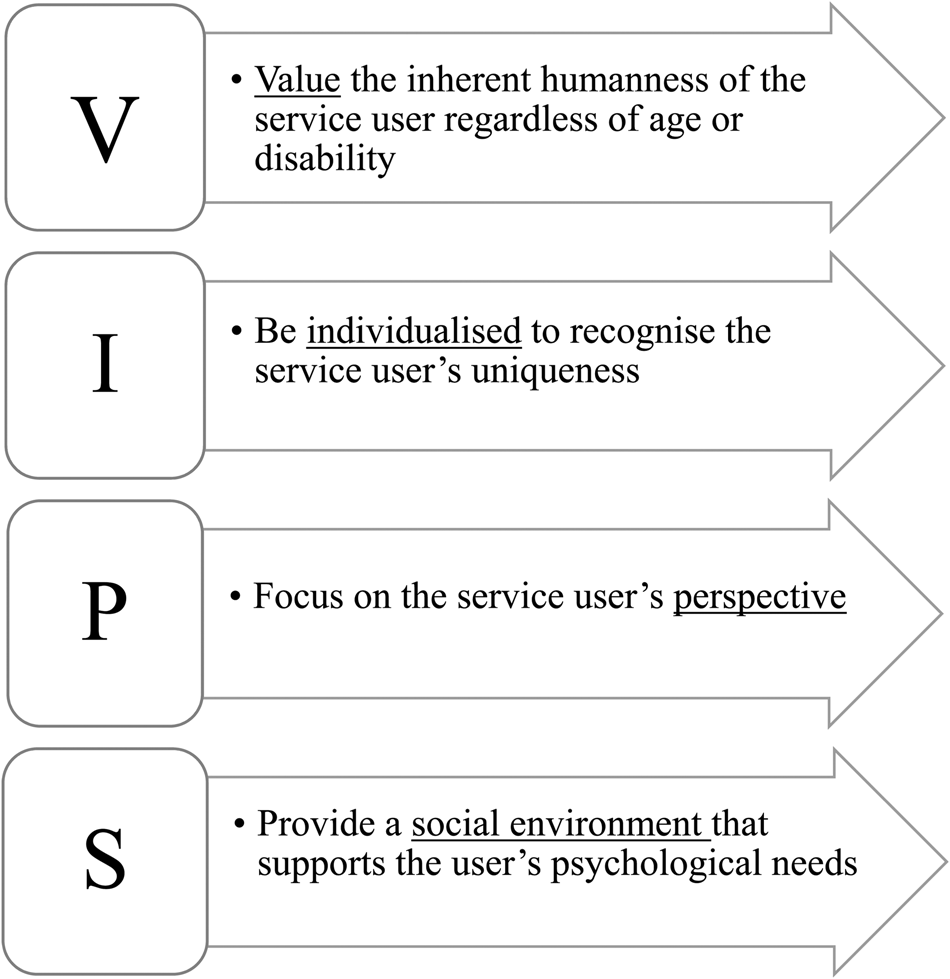

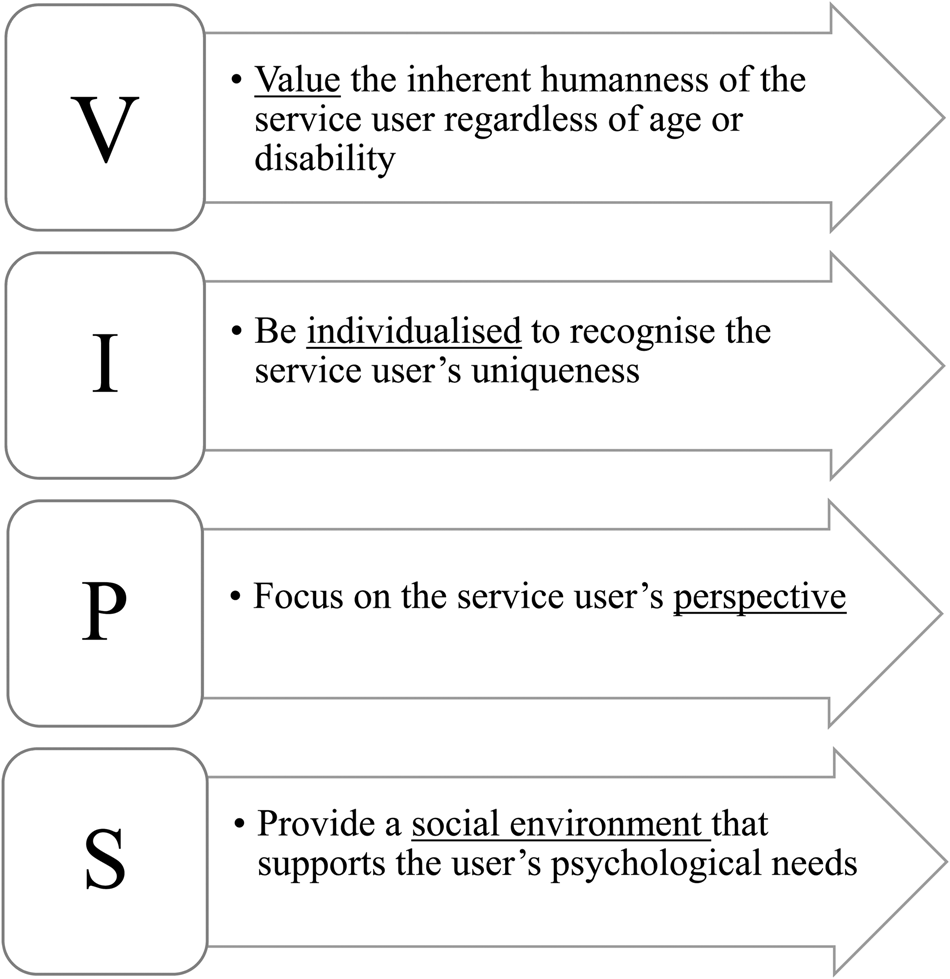

A concerted organisational effort is required to incorporate person-centred principles across the revised Standards (Chenoweth et al., Reference Chenoweth, Stein-Parbury, Lapkin, Wang, Liu and Williams2019). This requires managerial leadership and commitment to the principles (Brownie and Nancarrow, Reference Brownie and Nancarrow2013), a knowledgeable and skilled workforce (Stein-Parbury et al., Reference Stein-Parbury, Chenoweth and Jeon2012; Li and Porock, Reference Li and Porock2014; Chenoweth et al., Reference Chenoweth, Jeon, Stein-Parbury, Forbes, Fleming, Cook, Cheah, Fletcher and Tinslay2015, Reference Chenoweth, Jessop, Harrison, Cations, Cook and Brodaty2018) and clear guidance on process (Rokstad et al., Reference Rokstad, Vatne, Engedal and Selbæk2015; Brodaty et al., Reference Brodaty, Aerts, Harrison, Jessop, Cations, Chenoweth, Shell, Popovic, Heffernan, Hilmer and Sachdev2018). Importantly, adoption of person-centred principles requires a culture of collaboration between managers, staff, residents and families/advocates in decision-making regarding service delivery and evaluation (Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Fossey, Ballard, Moniz-Cook and Murray2012; Morgan and Yoder, Reference Morgan and Yoder2012; Kitson et al., Reference Kitson, Marshall, Bassett and Zeitz2013; Røsvik et al., Reference Røsvik, Engedal and Kirkevold2014, Reference Røsvik, Brooker, Mjorud and Kirkevold2013; Chenoweth et al., Reference Chenoweth, Jeon, Stein-Parbury, Forbes, Fleming, Cook, Cheah, Fletcher and Tinslay2015, Reference Chenoweth, Jessop, Harrison, Cations, Cook and Brodaty2018). Guidelines for organisation-wide adoption of person-centred principles are encapsulated in the ‘Valuing, Individualised Care, Personal Perspective, Social Environment’ (VIPS) framework (Figure 1), which was developed by Dawn Brooker in 2007 to assist aged (social) care services in the UK adhere to the requirements of a person-centred service ‘for persons with cognitive disabilities’ (Brooker, Reference Brooker2007: 123; Røsvik et al., Reference Røsvik, Brooker, Mjorud and Kirkevold2013).

Figure 1. The ‘Valuing, Individualised Care, Personal Perspective, Social Environment’ (VIPS) framework for person-centred services.

Source: Brooker (Reference Brooker2007).

A review of the VIPS framework statements by 50 aged (social) care providers and service user organisations worldwide (Røsvik et al., Reference Røsvik, Brooker, Mjorud and Kirkevold2013) identified 24 indicators within the four elements of the VIPS framework (Table 1). People living with dementia, their family members and care staff acknowledge that the VIPS framework indicators, as described by Brooker (Reference Brooker2007: 123–150), reflected their perceptions of a person-centred aged care service (Edvardsson et al., Reference Edvardsson, Fetherstonhaugh and Nay2010).

Table 1. The ‘Valuing, Individualised Care, Personal Perspective, Social Environment’ (VIPS) framework indicators for person-centred services (Brooker, Reference Brooker2007)

While many Australian residential aged care homes claim to provide person-centred services, there has hitherto been no investigation which confirms this. With reference to the four VIPS elements and 24 indicators, the study aimed to investigate whether services were person-centred from the perspective of a convenience sample of older residents, their family members and staff of aged care homes that claimed to be person-centred. Our research question was:

• In what respects are aged care homes person-centred, as claimed?

Study methods

Design

This prospective study was conducted over six months from April to September 2019 using qualitative methods.

Setting

The study was conducted in a convenience sample of seven Australian government-accredited aged care homes across metropolitan Sydney that claimed to offer a person-centred service on the home's website, in the home's prospectus, and in family/resident and staff handbooks.

Participants

Study participants comprised a convenience sample of participating aged care home residents, their family members and staff working in a variety of roles. All participants needed to provide written informed consent to join the study and have the capacity to participate in a one-on-one interview in English. Residents were included if they were permanently residing in the aged care home, and were excluded if they presented with cognitive limitations and health issues that, according to family and staff opinion, would affect their ability to participate meaningfully in an interview to answer questions about care service quality. Thus, exclusion criteria were severe cognitive impairment, pre-existing anxiety or psychotic diagnoses, a debilitating illness or significant hearing impairment. The residents’ family members were recruited if they were regular visitors to the aged care home. Staff members were included if they were permanent employees in the aged care home, as these staff were more likely to have a broader appreciation of all service operations than casual or agency staff and, thus, have greater insights when answering the interview questions.

Recruitment: aged care homes

One member of the research team accessed the ‘MyAgedCare’ website (the public website providing information on aged care services across Australia) and utilised its ‘Find an aged care home provider’ service to identify aged care service providers across metropolitan Sydney. Additional internet searches were conducted to identify service providers that were not serviced through MyAgedCare. The available websites of these service providers were then reviewed, searching for the keywords ‘person-centred’ or ‘resident-centred’ and ‘individualised care’ or ‘personalised care’ in service statements, to identify service providers that claimed to offer a person-centred service.

For the 52 service providers identified as offering a person-centred service, one research team member obtained their generic contact details, and sent an email or made a phone call to request the contact details of a representative with whom to discuss the study. An email with the study details and researchers’ contact details was provided to the representative, seeking an expression of interest to join the study. Eleven of the 52 service providers expressed interest and were willing to discuss the study further at a face-to-face meeting between service executives and two of the research team members.

During the meeting, the research team members provided relevant study documents, discussed the study with the representative(s) and answered any questions they had before seeking written institutional consent. Institutional consent included agreement to post the recruitment posters in the aged care home(s), make the recruitment flyers available to all residents, family members and staff members, and allow access to their aged care home(s) to conduct interviews. Upon receiving written institutional consent, aged care homes belonging to the aged care provider were nominated by that provider's service executives. The recruitment posters and flyers were then provided for distribution in the nominated home(s). The service executives were advised that participant recruitment and data collection were limited to the following six months because of the study time-frame mandated by the requirements of the first team member's medical degree.

Of the 14 aged care homes nominated by the 11 service providers, seven agreed to participate in the study; one withdrew due to internal commitments, five produced no interested participants and interviews for one home could not be arranged before the study's end-date.

Recruitment: participants

Volunteer participants were recruited via an arms-length approach through the posting of recruitment posters in the aged care homes and making recruitment flyers available at the reception and staff rooms. The aged care home managers extended invitations to all residents, family members and staff members, and let them decide whether they wanted to participate. Residents, family members and staff members who wished to participate in the study indicated their interest either directly to the researchers via the contact details provided in the recruitment materials or through the aged care home manager. One member of the research team then contacted them to provide more information about the study and the consent procedures, and arranged a suitable interview date, time and venue with those who expressed interest.

Prior to the start of each interview, the volunteer participants were given a verbal explanation of the study, including the interview aims and procedures, a written copy of the interview questions, and details on how the interview data would be recorded, stored, analysed and reported. Participants were assured of participant confidentiality by the allocation of a unique identifier code, removal of identifying information and secure storage of their data. They were also reminded that their participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw their participation at any time without censure. The researchers gave additional time to the participants to read the participant information statement and consent form and discuss the study, before obtaining their written consent.

Data collection

An interview schedule was developed by the research team, informed by Brooker's (Reference Brooker2007) descriptors of the four elements and 24 indicators of the VIPS. Interviews included the following: greetings and introduction to the study aims and methods; clarification of the interview process, data security and participant confidentiality procedures; obtaining informed consent; experiences of living/working/visiting the home; perceived focus of services including care; understanding of person-centred services and how these services are provided in the home; opportunities for education, training and discussions about person-centred care, and how this is translated in day-to-day services; exploration of the workplace culture, team work and management support of person-centred services; discussion on care and leisure/lifestyle planning procedures, how individual psycho-social needs, resident and family perspectives, and family participation are incorporated in services; ways in which relationships and meaningful activities for residents are fostered and supported by staff; ways in which managers and senior staff could better support person-centred services, and suggestions on what areas of service could be improved to support this approach.

Two members of the research team (research student and principal supervisor) conducted the semi-structured interviews (N = 43) with consenting residents, family members and staff members between May and August 2019. The first 22 interviews were conducted jointly for training purposes, to enable more comprehensive probing of responses and to establish inter-rater reliability when analysing the interview data. The remaining 21 interviews were conducted by the research student unsupervised. Interviews were conducted at a venue and on a date and time that was convenient for the participants. Forty-two of the 43 interviews were conducted in a private, closed room within the aged care home, and one phone interview was conducted as the participant was unable to meet up physically for the interview. Two joint interviews were conducted (i.e. one with resident partners, and one with a resident and a family member) by resident preference. The other 41 interviews were conducted with individual participants. Interviews took between 40 and 90 minutes, to allow ample time for participants to feel comfortable with the interview process and elaborate on their answers. The interviews were audio-recorded with the participants’ permission, and recordings were stored on a password-protected server accessible only to the research team members.

Data analysis

Interview recordings were transcribed verbatim by the research student to ensure accuracy and consistency in the data. The participants were allocated unique identifier codes, e.g. CH01_R01 (care home 1, resident 1), and any identifying information was removed in the transcription process. The transcribed data were checked by the research student's principal supervisor who had assisted with the first 22 interviews and were stored on a password-protected server that was accessible only to the research team.

The interview data were deductively analysed with reference to the four VIPS elements and 24 VIPS indicators. To establish inter-rater reliability with data coding, two members of the research team independently analysed the data using the following process: text familiarisation, data categorisation according to the 24 VIPS indicators, interpretation of data and allocation of data codes, and identifying core concepts to derive key themes for each research question. The data were managed and organised using Microsoft Word and tabulated. The research team members held multiple meetings to discuss, compare and document their independent and shared findings through an iterative process. Any discrepancies in findings were discussed until consensus was achieved on the final codes that emerged from the data. This process continued until 90 per cent inter-rater reliability was achieved between team member ratings, which occurred by dividing the number of agreed codes by the number of agreements and disagreements (Miles and Huberman, Reference Miles and Huberman1994). The common themes arising from the agreed codes were identified and named by research team members through close inspection and discussion of the participant quotes associated with the agreed data codes (Gibbs, Reference Gibbs2018). Data saturation was reached when no new codes were identified in the data and when all codes fitted into existing themes.

Results

Of the seven participating aged care homes, there were three from Northern Sydney, two from Eastern Sydney, and one each from Southern and South Western Sydney. Other characteristics of the seven participating aged care homes are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Aged care home demographics

Notes: 1. Small: 1–9 homes; medium: 10–19 homes; large: ⩾20 homes. 2. Small: ⩽75 beds; medium; 76–149 beds; large: ⩾150 beds.

Participant demographics are listed in Table 3. The demographics of participating residents and staff members reflect nationally reported aged care home statistics (King et al., Reference King, Svenssen and Wei2017; Mavromaras et al., Reference Mavromaras, Genevieve, Isherwood, Crettenden, Flavel, Karmel, Moskos, Smith, Walton and Wei2017; AIHW, 2019a, 2019b).

Table 3. Participant demographics

The results from the interview data are presented in three sections: (a) themes common to all seven aged care homes, (b) themes common to the two more person-centred aged care homes, and (c) themes common to the five less person-centred aged care homes.

All seven aged care homes adhered to at least some aspects of the four VIPS elements in service provision; 13 themes emerged to support this finding, as described in Table 4.

Table 4. Themes common to all seven aged care homes

Our findings indicate that all seven aged care homes were making concerted efforts to adhere to important aspects of a person-centred service, as defined by the VIPS (Brooker, Reference Brooker2007). According to the study participants, however, none of the seven homes was fully person-centred across all service offerings. Only two of the seven homes were considered to adhere more fully to the four elements and 24 indicators of the VIPS framework across all service offerings, and that the managers and staff had gained a deep understanding of Kitwood's (Reference Kitwood1997) person-centred service philosophy. Four prominent themes signify their closer adherence to the VIPS framework, as follows.

Theme 1: Valuing – staff empower residents to maintain their cognitive and bio-psychosocial function

Residents and family members considered that residents had opportunities to contribute meaningfully to the home's operations and were encouraged by staff to maintain meaningful self-determined function:

In here they can still do things that they used to do, and they haven't been dragged away from that just because they can't communicate. (CH06_F01)

Theme 2: Valuing – staff are provided with clear expectations and guidelines on person-centred service delivery

Staff members demonstrated a clear understanding of the person-centred approach. This was facilitated by organisational policies and practice expectations that focused on the person-centred model. Staff were also empowered to deliver person-centred services across all service areas (i.e. including catering and housekeeping), facilitated through person-centred education and training:

…right from the moment you start with the company, it's (person-centred care) ingrained into your training. (CH01_S02)

Theme 3: Valuing – managers advocate for a person-centred service philosophy

Managers were acknowledged for providing clear leadership in promoting and enabling person-centred services. Staff, residents and family members identified the positive effects of managerial role-modelling of a person-centred approach in all their dealings.

…She [Manager] was a real driving force for that [person-centred care]. (CH01_S02)

Theme 4: Social environment – managers and staff celebrate human diversity

Residents considered that staff had made them feel welcome and had been interested in and valued their unique qualities, regardless of the diversity of their background and abilities:

The fact, I'm a big crazy person in many ways … I received a very, very good welcome from everybody. Not one person has said to me … Not you! (CH01_R01)

As previously stated, while the remaining five aged care homes adhered to some important aspects of the four VIPS elements, there were many service areas that were not person-centred. Ten themes arose from the data which indicated a failure of these five care homes to adhere fully to the four elements and 24 indicators of the VIPS framework, as follows.

Theme 1: Valuing – residents, families and staff are not empowered to influence change

Residents and family members considered that residents may be hesitant to voice their opinions out of fear of retaliation:

…we're always mindful of retaliation because you are here sit [sic] like a sitting duck. (CH02_F03)

Even if platforms for resident suggestions and complaints were available, residents were unwilling to voice their concerns. Residents and family members appeared to express a sense of resignation to the existing state of services and considered that they were ‘as good as it can be’ (CH07_F03). For the staff members, there were structural limitations to prompting managerial responses to individual requests.

Theme 2: Individualised care – services are standardised

Residents found themselves having to fit into given schedules. While some residents willingly accepted the necessity to comply with fixed schedules, others voiced despair at their exposure to an institutionalised service ethos:

I always had a good life … I did what I wanted to do … but I came here and, and you've got rules. (CH07_R01)

Some residents were aware that they could retain preferred daily routines because of their self-care ability. In some cases, socio-cultural assumptions had been applied to service offerings, which were not considered necessarily suitable for everyone belonging to that particular culture or social background.

Theme 3: Individualised care – service offerings are not individualised

Residents and family members considered that the recreational and spiritual activities offered generally catered to the interests and needs of the majority. There were few opportunities to engage in individual leisure activities that were more relevant to a resident's unique interests, or suitable for residents with higher care and cognitive support needs.

Theme 4: Individualised care – workforce limitations impede provision of individualised care

Residents and family members considered that there were inadequate numbers of staff to provide individualised care. Staff were seen to be overly busy and lacked the time to pay attention to individual needs:

Don't, don't expect to be looked after, because they haven't got time. (CH07_R01)

Families also considered that staff were not adequately trained to care for vulnerable older people. Both residents and family members identified how important staff education was, with respect to some cultural differences in staff's perceptions and priorities in aged care. Family members believed that they needed to advocate for the resident's care needs and lifestyle preferences, while residents reflected that they had to rely on their family and friends to support their preferred lifestyle activities.

Theme 5: Individualised care – acknowledgement of resident's life story is limited by staff interest

Residents and family members considered that not all staff members took an interest in getting to know the residents. Some residents identified that they needed to initiate the sharing of their life story with staff, while family members found it necessary to make staff aware of the resident's unique history, as they often did not seek out this information.

Theme 6: Personal perspective – staff's responses to residents’ emotional needs relates to staff characteristics

Residents and family members found that staff were so busy that they did not dedicate time to discuss the resident's emotional needs, and they also lacked the skills to explore the resident's emotional issues. Residents and family members considered that staff who were more empathetic to resident issues were from cultures that traditionally care for older family members in mixed-generation households. Some staff members identified that their empathy for resident's feelings was developed through personal experience, such as being a care recipient themselves and/or from caring for an older family member, rather than through care home orientation and training opportunities.

Theme 7: Social environment – staff–resident relationships are impacted by staff characteristics

Residents and family members considered that opportunities to foster meaningful staff–resident relationships were dependent on the staff member's personality and whether he or she was personally interested in getting to know the residents. Few education or training opportunities were available to staff which focused on forming meaningful relationships with residents and families.

Theme 8: Social environment – staff–resident relationships occur through the efforts of residents

In forging positive staff–resident relationships, residents and family members considered that residents themselves needed to make efforts to get to know the staff. These efforts included initiating conversations with staff members and showing them respect.

Theme 9: Social environment – meaningful resident–staff relationships depend on communication opportunities and abilities

Residents, family members and staff members considered that opportunities for staff to have conversations with residents occurred only during care tasks, or after they had completed their duties. They observed that staff were overworked and had little time for informal interactions with residents. Some residents and staff members found it difficult to communicate with each other because of the resident's limited communication ability and language barriers that existed between them.

Theme 10: Social environment – meaningful relationships between residents depend on resident characteristics

Residents and family members considered it difficult for residents to form meaningful relationships with each other, as many of them had limited capacity to do so. The main issues included having no common language for residents with limited/no English skills, and reduced communication skills in residents with cognitive and/or sensory impairment. Positive relationships occurred among residents who were able to build rapport with each other. This related to having ‘like-minded personalities’ (CH03_F01), having similar backgrounds and being able to communicate in a common language.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate from the perspective of residents, their families and the staff members in seven aged care homes that purported to be person-centred, the extent to which they were. It was evident that there were efforts being made by all seven aged care homes to make services more person-centred, as required by the revised Australian Standards (Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission, 2019), where services are expected to focus on resident outcomes and reflect the level of care and services that is expected of government-subsidised aged care services. However, it was equally evident that despite service statements referring to person-centred services, few homes fully appreciated the requirements of a system-wide person-centred aged care service. To our knowledge, this is the first Australian study to investigate the implementation of a system-wide person-centred service in aged care homes according to the VIPS framework, by giving voice to those most intimately involved in these services: the residents, families and staff members. Study participants provided valuable insight into the key structures that enable the delivery of person-centred services, many of which have also been identified in the literature (Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Fossey, Ballard, Moniz-Cook and Murray2012; Morgan and Yoder, Reference Morgan and Yoder2012; Kitson et al., Reference Kitson, Marshall, Bassett and Zeitz2013; Røsvik et al., Reference Røsvik, Brooker, Mjorud and Kirkevold2013, Reference Røsvik, Engedal and Kirkevold2014; Chenoweth et al., Reference Chenoweth, Jessop, Harrison, Cations, Cook and Brodaty2018).

A key indicator of a person-centred service was the existence of mutually positive feelings, respect and engagement between residents, families and staff members. In two of seven homes that made greater efforts to provide system-wide person-centred services, there was closer adherence to all 24 indicators within the four VIPS elements (Brooker, Reference Brooker2007) across service offerings. Notably, staff not only catered to individual needs and preferences, but also respected the humanness of each resident, as required by the Australian Standard 1 (Consumer dignity and choice) and Standard 2 (Ongoing assessment and planning with consumers). These standards require staff to support the resident's physical, psycho-social and spiritual needs in partnership with the person themselves, their families and friends, and the health-care team. Moreover, residents had more opportunities to live their life as they determined and to be engaged in the life of the home. Residents and families had a voice in making decisions about care and lifestyle requirements, despite residents’ cognitive and sensory limitations. This achievement aligned with Standard 3 (Personal care and clinical care) and Standard 4 (Services and supports for daily living). Staff helped residents to retain their rights and to take control of their own lives with the support of close families/carers. These outcomes also aligned with Standard 5 (Organisation's service environment) and Standard 8 (Organisational governance), whereby the service philosophy, policies and operations were focused on helping the resident, their family and staff to experience quality of life and wellbeing. This was evidenced by the high level of communication and empathy between staff members, as well as between the staff, residents and families. While person-centred homes have been distinguished by collegiality, support and teamwork among staff members (Røen et al., Reference Røen, Kirkevold, Testad, Selbæk, Engedal and Bergh2018), the positive feelings that residents and families had for the staff and vice versa has not been previously described.

In these person-centred homes, there was managerial leadership and a commitment in supporting person-centred services, as required by Standard 8 (Organisational governance), Standard 6 (Feedback and complaints) and Standard 7 (Human resources). Achievement of this requirement occurred in the way that the home operated to meet the needs of residents, their families and friends, and all members of staff who were involved in service delivery. Person-centred leadership was also evidenced by manager and staff willingness to adapt services to meet changing resident needs, and in response to resident, family and staff feedback. Managers play a vital role in leading a clear vision in providing such services (Rokstad et al., Reference Rokstad, Vatne, Engedal and Selbæk2015) for which managerial support is crucial in implementing a system-wide person-centred service (Chenoweth et al., Reference Chenoweth, Jeon, Stein-Parbury, Forbes, Fleming, Cook, Cheah, Fletcher and Tinslay2015).

Staff members of the two more person-centred homes also received supervision, mentoring and support from their managers, in compliance with Standard 7 (Human resources). This type of managerial support for staff is a necessary ingredient in a person-centred service (Røsvik et al., Reference Røsvik, Engedal and Kirkevold2014; Chenoweth et al., Reference Chenoweth, Jeon, Stein-Parbury, Forbes, Fleming, Cook, Cheah, Fletcher and Tinslay2015, Reference Chenoweth, Jessop, Harrison, Cations, Cook and Brodaty2018). Additionally, managers made themselves available to the staff and were responsive to the issues they raised. Responsive managers assist staff to deliver person-centred services, but this requires that managers devote more time and energy to dealing with dilemmas between priorities and risk (Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Fossey, Ballard, Moniz-Cook and Murray2012; Sjögren et al., Reference Sjögren, Lindkvist, Sandman, Zingmark and Edvardsson2015). In compliance with Standard 2 (Ongoing assessment and planning with consumers), the managers of more person-centred homes had established systems that enabled staff to be included along with residents and families in service planning. Study participants recognised this as ‘empowering leadership’, a managerial style that encourages those impacted by service offerings to take initiative and participate in decision-making processes (Røen et al., Reference Røen, Kirkevold, Testad, Selbæk, Engedal and Bergh2018). This concept on frontline staff empowerment had also been referred to as a democratised approach to decision-making (Brownie and Nancarrow, Reference Brownie and Nancarrow2013), a system of shared governance (Porter-O'Grady, Reference Porter-O'Grady2003) and decentralised decision-making (Brown and Miller, Reference Brown and Miller2003). An important part of delivering person-centred services includes opportunities for staff members to participate in decisions on care practices (Kitwood, Reference Kitwood1997). Decisions made solely from the managerial point of view may result in difficulties faced by care staff in translating service directives into actual practice (Brown and Miller, Reference Brown and Miller2003).

In these person-centred homes, staff were able to identify person-centred principles and how they implemented them in practice. Moreover, they indicated commitment to embracing this philosophy of care and applying the approaches in various care situations. Such homes had regular, focused education and skills training for staff, and regular guidance from senior staff members on person-centred services, the importance of which previous studies have emphasised (Chenoweth et al., Reference Chenoweth, King, Jeon, Brodaty, Stein-Parbury, Norman, Haas and Luscombe2009, Reference Chenoweth, Jeon, Stein-Parbury, Forbes, Fleming, Cook, Cheah, Fletcher and Tinslay2015, Reference Chenoweth, Jessop, Harrison, Cations, Cook and Brodaty2018; Jeon et al., 2015; Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Fossey, Ballard, Moniz-Cook and Murray2012; Doyle and Rubinstein, Reference Doyle and Rubinstein2013; Colomer and de Vries, Reference Colomer and de Vries2016; Hunter et al., Reference Hunter, Hadjistavropoulos and Kaasalainen2016; Brodaty et al., Reference Brodaty, Aerts, Harrison, Jessop, Cations, Chenoweth, Shell, Popovic, Heffernan, Hilmer and Sachdev2018). Crucially, these homes address gaps in knowledge and variation in personal beliefs on person-centredness (Colomer and de Vries, Reference Colomer and de Vries2016; Hunter et al., Reference Hunter, Hadjistavropoulos and Kaasalainen2016) and create more efficient care practices (Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Fossey, Ballard, Moniz-Cook and Murray2012).

The study findings confirm previous research findings on the important contributions of both management and staff in delivering person-centred services (Stein-Parbury et al., Reference Stein-Parbury, Chenoweth and Jeon2012; Brownie and Nancarrow, Reference Brownie and Nancarrow2013; Li and Porock, Reference Li and Porock2014; Chenoweth et al., Reference Chenoweth, Jeon, Stein-Parbury, Forbes, Fleming, Cook, Cheah, Fletcher and Tinslay2015, Reference Chenoweth, Jessop, Harrison, Cations, Cook and Brodaty2018; Brodaty et al., Reference Brodaty, Aerts, Harrison, Jessop, Cations, Chenoweth, Shell, Popovic, Heffernan, Hilmer and Sachdev2018). The study findings also indicate that leadership and support are required from managerial staff, while care and lifestyle staff must be equipped with person-centred service awareness, knowledge and skills. A key indicator of a less person-centred service in this study was the institutionalisation of stereotyped, standardised care and lifestyle programmes, which were largely imposed by senior decision-makers. In these homes, most of the residents and some of the family members expressed maladaptive acceptance of such non-personalised services. The reasons for the resident's tardy acceptance and/or lack of co-operation with service offerings were rationalised, or not acknowledged, by staff. Staff's misinterpretation of the reasons for the resident's reluctance and/or refusal to participate in particular activities indicated a lack of understanding of person-centred principles.

It was in the lifestyle/recreation programmes offered to residents that a stark contrast occurred between the two person-centred homes and the other five aged care homes. In the more person-centred homes, staff claimed that they actively engaged residents in programmes and activities that were suited to their interests and which were adapted to cater to their declining abilities. The staff of the other five care homes appeared to pay little more than lip-service to person-centred principles in these programmes. Staff stated that they often made singular attempts at supporting individual care, lifestyle and meal preferences, but few strategies existed to include residents and families as equal partners in service offerings. Family member and resident participants suggested that services were provided to residents as a ‘cohort’ of older people, rather than as unique individuals. Staff's misinterpretation of the reasons for the resident's reluctance and/or refusal to participate in group lifestyle/recreation activities indicated a lack of understanding of person-centred principles.

Within this ‘cohort’ model, residents were viewed as service consumers, reflected in the predominantly group-based lifestyle activities available to residents, undifferentiated by residents’ unique social and cultural backgrounds or preferences (Chenoweth et al., Reference Chenoweth, Jeon, Stein-Parbury, Forbes, Fleming, Cook, Cheah, Fletcher and Tinslay2015). Staff from these homes showed little awareness of the possibility that meaningless group activity could be experienced as dehumanising by residents (Brooker, Reference Brooker2007), and that it was essential to avoid stereotyping older people to maintain their dignity (Edvardsson et al., Reference Edvardsson, Fetherstonhaugh and Nay2010). The reasons behind the reluctance and/or refusal of residents to participate in meaningless group activities were generally not pursued and sometimes even misunderstood as being indicative of the resident's cognitive or physical decline. These findings, not previously reported in Australian research, corroborate those of studies in the United States of America (Harrison and Frampton, Reference Harrison and Frampton2017) and the UK (Talbot and Brewer, Reference Talbot and Brewer2016), where residents reflected how aspects of institutionalised life remained, despite an embedded person-centred philosophy of care.

In the homes that made piecemeal attempts at delivering person-centred services, there were expressions of uncritical tolerance of service failings by residents and families. They defended the lack of person-centred services by saying things such as ‘it is difficult to be perfect’ (CH07_F04) and citing workforce limitations as excuses for unacceptable failures in care. The family members believed that they had to be physically present in the home to compensate for staff inattention to their loved one's needs. This sentiment was expressed by residents through taking on the ‘good resident’ role, whereby they remained appreciative and considerate to the staff even though they considered that they were receiving a poorer level of care than desired. Such maladaptive behaviour could explain their reluctance to complain, contentment with the status quo and unwillingness to make personal requests. A UK study similarly reported residents’ experiences of poor-quality care, human indignities and violations of personal autonomy, but justified this with the staff's overwhelming workload. As occurred in the present study, the residents reported individual coping strategies to deal with and rationalise the less-than-desirable situation in which they found themselves (Donnelly and MacEntee, Reference Donnelly and MacEntee2016). Another UK study similarly reported how residents made compromises to fit in with the staff's schedules instead of exercising personal choice on their own bedtimes (Luff et al., Reference Luff, Ellmers, Eyers, Young and Arber2011).

It was telling that in homes making fewer attempts to be person-centred across systems, many members of staff did not understand the intentions of the person-centred approach and staff training in the model had been absent or minimal. Nevertheless, some staff members identified with a person-centred approach intuitively because of their personal background. Although innate staff qualities of empathy, kindness, patience and personal experience do contribute to a person-centred approach (McCormack and McCance, Reference McCormack and McCance2006; Hunter et al., Reference Hunter, Hadjistavropoulos and Kaasalainen2016), without focused education and training opportunities the intention of the person-centred model may be misunderstood as simply a function of kindness and compassion. This misunderstanding can lead to variable practices and a poor appreciation of what matters most to the resident (Colomer and de Vries, Reference Colomer and de Vries2016; Hunter et al., Reference Hunter, Hadjistavropoulos and Kaasalainen2016).

Consistent staff assignment is considered essential to a person-centred service (Brooker, Reference Brooker2007), where staff are in situ long enough to form relationships with residents and gain familiarity that trust requires. This was often lacking in homes without a system-wide focus on person-centredness. However, even where consistent staff assignment had been implemented, it was difficult for staff to include relational approaches in care delivery with any regularity because of their workload. These findings are not unique to this study, as time pressures from routine tasks has been cited as a reason for the persistence of task-focused care (Talbot and Brewer, Reference Talbot and Brewer2016) and associated with resident disengagement (Donnelly and MacEntee, Reference Donnelly and MacEntee2016; Talbot and Brewer, Reference Talbot and Brewer2016). Often, short staffing was cited as a reason for staff overwork, reflecting the current challenges over low staff-to-resident ratios faced by the aged care system in Australia (Productivity Commission, 2019).

It was evident that the middle managers were usually well-liked by residents, families and staff, despite the level of person-centredness of these services. In homes making little attempt to provide a system-wide person-centred service, this view was justified by the perception that such managers were often constrained by conditions imposed by their own superiors (Love and Pinkowitz, Reference Love and Pinkowitz2013). In such cases, family members expressed resignation in the face of service limitations. This is consistent with publications on residents’ acceptance of the regulatory, structural and administrative constraints to implementing a person-centred service (e.g. Burack et al., Reference Burack, Reinhardt and Weiner2012). The study findings reinforce the idea that the type of leadership, rather than the presence of leadership, is key to service satisfaction.

Overall, while most staff members considered that their managers were attempting to provide a person-centred residential aged care service, the family and resident reports indicate there was little organisational vision and commitment to the fundamental system structures required for enabling staff to practise person-centred care. For many residents, the aged care home resembled little of the home they knew and loved, where their lives were rich with meaning. The two aged care homes that had made concerted efforts towards offering a person-centred service were outstanding in their attempts to achieve this for their residents.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include the use of the four elements and 24 indicators of the VIPS framework (Brooker, Reference Brooker2007) to frame and analyse the study data, the richness of these data and the frank accounts of the participants in describing their experiences in aged care homes that claim to be person-centred. Study limitations are the small number of purposefully selected Sydney-based aged care homes recruited to the study, the lack of regional representation and the small convenience sample of participants associated with these aged care homes. It is unknown whether the residents and their families who volunteered to participate were more or less likely to be dissatisfied with services or whether staff participants were more or less likely to be satisfied with service quality. Furthermore, the small sample which excluded residents with severe cognitive impairment may have failed to reflect the full scope of care needs and services operating within Australian aged care homes, other than those described by family members and staff. The data are also limited by the variable capacities of the participants to answer some questions, e.g. clarity on the person-centred philosophy care and approach. As well, in some cases it was not possible to extend the interviews to explore fully some of the questions posed, especially when residents felt fatigued after 30–45 minutes and staff interviews had to be limited to 60 minutes because of work commitments. The findings need to be interpreted cautiously, considering the study's selection bias, small sample size and data limitations.

Another limitation was the review of available aged care home handbooks and other materials describing service offerings. It would have been useful to have conducted an audit of policies and procedure documents that were not accessible to the research team, and to compare participant interview data with observations of service provision. These additional data would have allowed greater appreciation of the efforts being made by the aged care homes to incorporate the person-centred approach across services.

Study implications

This study has provided insights on the requirements and achievements of a person-centred residential aged care service, according to the VIPS framework (Brooker, Reference Brooker2007) and the revised Australian Aged Care Standards (Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission, 2019). It is possible to provide a person-centred approach across all services, as evidenced by two of the seven participating aged care homes. They were making strenuous efforts to provide system-wide person-centred services and to ensure that their staff were educated and supervised in this approach. In the other five aged care homes, the piecemeal efforts being made to offer person-centred services were limited by staff members’ general misunderstanding of what was required. Given the general misunderstanding of what a person-centred service entails and the workforce issues identified, urgent attention must be given to increasing staff numbers/capacity in meeting individual resident's needs and ensuring all staff have achieved the required levels of knowledge and competence for their role. These findings will inform service providers on how to refocus their efforts to provide a person-centred service and benchmark their service inputs, processes and outcomes against person-centred principles and assist them to meet the revised Australian Standards. In relation to policy making, practical guidelines on how Australian aged care providers can embed person-centred principles into day-to-day service delivery could be drawn up with reference to the 24 VIPS framework indicators, to help them meet the expectations of the revised Australian Standards (Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission, 2019).

Conclusion

Many of the issues that plagued the Australian aged care sector well over a decade ago are still evident, seemingly on a permanent loop, despite claiming a person-centred service ethos. Many issues need to be addressed in moving towards a truly person-centred aged care system. Since this study was limited in scale and relied on a purposeful sample of volunteer participant interviews, further research with a representative sample of Australian residential aged care services is required. The study provides insights for the Australian residential aged care sector on the lived experiences of those intimately involved in providing and receiving aged care services. This is particularly relevant now, given the mandate of the revised Aged Care Quality Standards to be person-centred and the ongoing Royal Commission investigation of Australian aged care services (Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety, 2019). This study also clarifies the requirements of person-centred aged (social) care services according to the VIPS framework, as part of a greater movement to improve the quality of care services for increasingly older and frailer populations.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the study's participants for the generosity of their time and insights, and the service providers and aged care homes that supported the study.

Author contributions

All authors helped with the conceptualisation of the study aims and methodology, and the writing and editing of the manuscript. SSLS and LC took responsibility for obtaining research ethics approval, for service provider, aged care home and participant recruitment, and for data collection and analysis of the data. All authors revised the final manuscript.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

Ethics approval was granted by the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee (UNSW HREC reference number HC180854).