Acceleration of high-quality, well-collimated return beam of relativistic electrons by intense laser pulse in a low-density plasma

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 July 2004

Abstract

The mechanism of electron acceleration by intense laser pulse interacting with an underdense plasma layer is examined by one-dimensional particle-in-cell (1D-PIC) simulations. The standard dephasing limit and the electron acceleration process are discussed briefly. A new phenomenon, of short high-quality, well-collimated return relativistic electron beam with thermal energy spread, is observed in the direction opposite to laser propagation. The process of the electron beam formation, its characteristics, and the time-history in x and px space for test electrons in the beam, are analyzed and exposed clearly. Finally, an estimate for the maximum electron energy appears in a good agreement with simulation results.

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- © 2004 Cambridge University Press

1. INTRODUCTION

Particle acceleration by intense laser fields propagating in plasmas has recently become a very attractive research topic due to the advent of short-pulse, high intensity lasers, and their many potential applications. Various concepts of laser accelerators in a plasma, such as, beat-wave accelerator (Clayton et al., 1993; Tajima & Dawson, 1979), laser wakefield accelerator (Antonsen & Mora, 1992; Sprangle et al., 1992; Esarey et al., 1993), electron beam wakefield accelerator (Chen et al., 1985; Miller et al., 1991) and plasma accelerator of photon beams (Wilks et al., 1988, 1989), are presently under discussion and investigation as possible approaches to acceleration to ultra-high energies. High-quality and high-energy particle beams have wide potential applications, for example, in the concept of fast ignition of inertial confinement fusion (ICF) (Tabak et al., 1994), laser induced nuclear reactions (Shkolnikov et al., 1997), radiography (Lasinski et al., 1999), etc. Stochastic heating and acceleration of electrons by two counter-propagating laser pulses were studied by some authors (Mendonca & Doveil, 1982; Mendonca, 1983; Shvets et al., 1998; Sheng et al., 2002). In recent years, much attention on particle acceleration have been made by theoretical analysis, particle simulations, and experiments.

When an intense laser pulse propagates in underdense plasma, by backward and forward stimulated Raman scattering (BRS/FRS), and other nonlinear processes, for example, the ponderomotive force of an intense laser pulse, a large amplitude electron plasma wave can be excited behind the front of the laser pulse (Mima et al., 2001). Relativistic electron plasma waves are also generated by a beat-wave scheme which requires two laser beams and a plasma frequency precisely tuned to their frequency difference. This large amplitude plasma wave has a very high phase velocity close to the group velocity of a laser pulse, and can be used to accelerate electrons, protons or ions to high energies. In underdense plasma, fast electron distributions peaked in the direction of laser propagation with the thermal energy spectra are observed. Often one finds two populations with two distinct temperatures. At present, there exists no clear understanding of above phenomenon in the literature.

In this paper, a short ultra-relativistic electron beam acceleration by an intense laser pulse in a finite plasma is examined by 1D-PIC simulations. The mechanism is the combined effect of the electron acceleration by longitudinal fields: synchrotron radiation source (SRS) driven oscillatory relativistic electron plasma wave and the electrostatic (ES) Debye sheath field at the plasma-vacuum interface. The standard dephasing limit and the electron acceleration process are briefly discussed. The novel point is that, at relativistic laser intensities, a phenomenon of pulsed high-quality well-collimated return relativistic electron beam with thermal energy spread in the direction opposite to laser propagation, is observed. The mechanism of the beam formation, its characteristics and the time-history in x and px space for selected test electrons in a beam, are analyzed and clearly exposed. Finally, an estimate for the maximum energy of ultra-relativistic electrons which agrees with particle simulations is given.

2. SIMULATION MODEL

In our simulations, one-dimensional electromagnetic relativistic 1d3v PIC code (all quantities depend on x-coordinate and on time and the particle momenta have three components) is used. The length of a simulation system is 5000c/ω0, where c and ω0 is the speed and carrier frequency of laser pulse in vacuum, respectively. The plasma length is 1000c/ω0 (159 laser wavelengths), it begins at x = 2000c/ω0 and ends at x = 3000c/ω0. At the front and rear sides, there are two vacuum regions. The number of cells is 10 per 1 c/ω0, 100 electrons in one cell and ions are kept immobile as a neutralizing background. The plasma density is n = 0.01ncr, which means ω0 /ωp = 10, where ωp is the electron plasma frequency, here ncr = ω02meε0 /e2 is the critical density for laser propagation in a plasma. The electron temperature is Te = 1 keV. The laser pulse is linearly-polarized with the electric field E0 along y-direction and launched at x = 1500c/ω0. The normalized amplitude of the incident laser pulse is a = eE0 /meω0 c, here e and me is the electron charge and mass, respectively. The electrons which are blown-off into a vacuum, build a potential barrier that prevents more electrons from leaving the plasma. For fast escaping electrons, as well as for electromagnetic waves, two extra damping regions at system ends are used.

The time, electric field, and magnetic field are normalized to 2π/ω0, mω0 c/e and mω0 /e, respectively, and the time is zero, t = 0, when laser pulse arrives at the front (left) vacuum-plasma boundary.

3. SIMULATION RESULTS

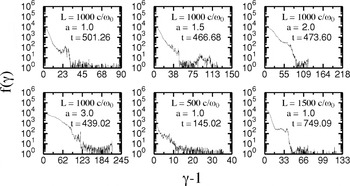

In order to study particle acceleration with an intense laser pulse, by varying the amplitude of laser pulse a = 1.0,1.5,2.0 and 3.0 (corresponding intensities I ≈ 1.37 × 1018, 3.09 × 1018, 5.49 × 1018, and 1.24 × 1019 W/cm2 for a 1 μm laser pulse, respectively) only, and keeping other simulation parameters fixed, different PIC runs are performed. As in Figure 1, the electron energy distributions, from our simulations show, the maximum obtained electron net momentum goes up to pmax/me c ≈ 91, 151, 219, and 246, corresponding to maximum electron energy: Emax ≈ 46, 77, 112, and 126 MeV, respectively. An electron interacting with a plane electromagnetic wave (laser field) acquires the energy equal to Ee = me c2a2/2, for example, a = 2.0, Ee ≈ 1.0 MeV. From this point, one cannot expect that energetic electrons found in laser-plasmas are directly accelerated by an ultra-intense laser field.

Snapshots of electron energy distributions from 1D-PIC simulations. The plasma density is n = 0.01ncr.

The self-modulated regime of laser plasma interaction is defined by a laser pulse with a normalized vector potential of the order of unity a = eE0 /meω0 c ≈ 1, pulse length of several plasma periods, and the laser frequency several times the plasma frequency. In the one-dimensional limit, the interaction between such intense laser pulses and a low-density plasma is dominated by the forward Raman scattering (FRS) instability (Esarey et al., 1994; Mori et al., 1994; Mori, 1997). FRS modulates intense laser pulse at the plasma frequency with a corresponding modulation of the plasma density. The resulting large electron plasma wave grows until it reaches the wave-breaking limit, after which, large number of background electrons are self-trapped and accelerated to high energies. The self-modulated laser wakefield accelerator (SM-LWFA) utilizes this mechanism to generate a beam of highly energetic electrons.

The large amplitude plasma waves are generated by a self-modulation or forward Raman scattering instability with a phase velocity vp, near the group velocity vg of the laser pulse, vp ≈ vg, so γp = (1 − vp2/c2)−1/2 ≈ (1 − vg2/c2)−1/2 ≈ ω0 /ωp, where γp is the Lorentz factor corresponding to the phase velocity vp of the plasma wave. According to Tajima and Dawson (1979), in the two-dimensional cold plasma theory, the critical amplitude of the plasmon is determined by the wave-breaking limit (standard dephasing limit), the maximum energy of an electron, trapped by the potential of a relativistic plasma wave, having an amplitude eφmax ≈ γp me c2 is given by Emax = 2γp2me c2. By taking the parameter ω0 /ωp = 10 we used, the maximum energy of an electron obtained is Emax = 102 MeV. In two cases of a laser pulse, a = 1.0 and 1.5, the maximum relativistic factor and the electron energy obtained, are γmax ≈ 91,151 and Emax ≈ 46,77 MeV, respectively, which is less than 102 MeV. This means that the large amplitude plasma waves do not exceed the wave breaking limit (standard dephasing limit). However, as the amplitude of laser pulse increase to a = 2.0 and 3.0, the maximum relativistic factor and the electron energy obtained are γmax ≈ 219,246 and Emax ≈ 112,126 MeV, respectively, the maximum electron energy is exceeding the standard dephasing limit. It was reported in experiments (Ting et al., 1996; Wagner et al., 1997) and studied by PIC simulations (Tzeng et al., 1997; Gordon et al., 1998) that maximum relativistic electron energies observed are in an excess of the standard dephasing limit Emax = 2γp2me c2. In recent years, a large effort has been made to understand why the maximum electron energy can exceed the standard dephasing limit. Studing the thermal effects on relativistic wave breaking has become an important issue (Sheng & Mayer-ter-Vehn, 1997). For example, Esarey et al. (1998), by including the space-charge field due to self-channeling, it was shown that the maximum energy Emax = 4γp2me c2 gain is greater by a factor of ≥2. A new kind of mechanism that leads to efficient acceleration of electrons in underdense plasma by two counter-propagating laser pulses may help to explain how the maximum energy can possibly exceed the standard dephasing limit, for particle acceleration from the wave breaking, as suggested by some authors (Shvets et al., 1998; Sheng et al., 2002).

In addition to the above simulation runs, by changing the plasma length to L = 500, 1000, 1500c/ω0, and fixing the laser amplitude to a = 1.0 and other plasma parameters, we get the maximum relativistic factor γmax ≈ 41,91,134, with the corresponding maximum electron energy Emax ≈ 21,47,68 MeV, respectively. A fact is found, that is, the longer the plasma length, the larger the Lorentz factor γmax.

In the next part, we leave the dephasing limit problem; our goal is to focus on a generation of a pulsed high-quality, well-collimated return electron beam, and to study ultra-relativistic beam characteristics, the mechanism of the formation, and the time-history in x and px space of the beam electrons.

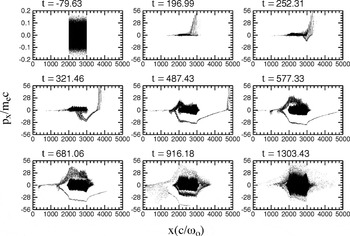

In Figure 2, for the electron longitudinal momentum snapshots in phase-space x − px, physics of electron acceleration can be seen more clearly and directly. At an early stage background, electrons start to interact with a forward propagating relativistic electron plasma wave generated by a laser pulse, and are accelerated to large positive momenta px. The accelerated electrons move forward to the right plasma-vacuum boundary, as shown in Figures 2 and 3, and escape plasma layer into vacuum region to build a potential barrier, a large electrostatic field that is quickly formed (Fig. 4). This sheath ES field structure gradually decreases in vacuum region. The accelerated electrons entering this region experience deceleration to be eventually stopped. Further, by reflection, electrons reverse their motion to be accelerated backward into the bulk plasma. However, some ultra-fast electrons overcome the potential barrier and eventually are lost in the numerical-damping region, that we introduced.

Total electron momentum snapshots, in x − px phase-space from PIC simulation, for laser pulse, a = 1.0.

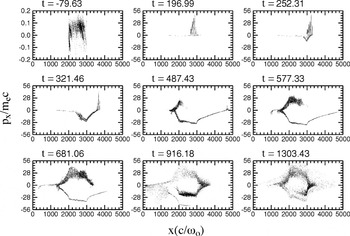

Test electron momentum snapshots, in x − px phase-space from PIC simulation, for laser pulse, a = 1.0.

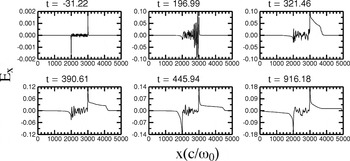

Snapshots of electrostatic field Ex (normalized to mω0 c/e), in the case of laser pulse, a = 1.0.

Electrons travelling backward through the bulk plasma will be additionally accelerated by the ES sheath at the front interface (Fig. 4). As the time progresses, a mono-energetic well-collimated relativistic electron beam bunch (energy about 12–17 MeV) is eventually formed. When these electrons get through the front interface into vacuum, they again experience deceleration and reverse acceleration by the ES sheath potential. Most of the electrons returning into the bulk plasma are moving forward to the rear boundary. However, in the meantime, the high-quality well-collimated relativistic electron beamlet will gradually separate from the rest of the beam. Since the ES field at the plasma-vacuum boundary still exists, electrons which arrive at the rear side experience the similar process as before. Moving back and forth energetic electrons recirculate through the bulk plasma. In time, due to beam interactions with the bulk, relativistic beam features will eventually be lost via thermalization with the rest of the heated bulk plasma.

To see this process more clearly, by taking the time interval between 239 ≤ t ≤ 955 (corresponds to start and the end of this high-quality, well-collimated return electron beam), we select test electrons having negative momenta between −20 ≤ px /me c ≤ −90 in this time interval 239 ≤ t ≤ 955. About 1.3% of the total number of electrons satisfy this condition in our simulation. This means that, at least 1.3% electrons are accelerated to γ ≥ 20 in the case of a laser pulse with a = 1.0. These test electrons cover the whole range of the accelerated electrons that we discussed above. By introducing test electrons, we can trace back their earlier time history easily and vice versa. Figure 3 gives the test electron longitudinal momentum snapshots in phase-space x − px; a picture for electron acceleration, deceleration, forward and backward motion and so on, is more clear.

For the plasma length of 1000c/ω0, laser pulse propagates in a plasma and arrives at the right plasma-vacuum interface at t ≈ 159; after that, although the laser pulse still propagates in a plasma, the electron acceleration by large plasma wave is almost finished by this time. Nearly all of the forward accelerated electrons are accelerated by the transient relativistic plasma wave before a laser pulse arrives at the right plasma boundary.

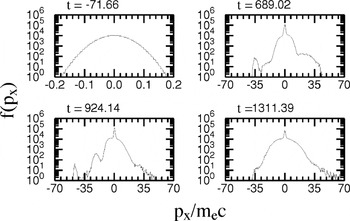

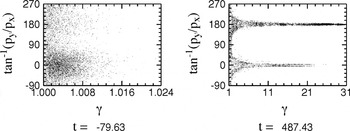

Figure 5 shows the snapshots of electron longitudinal momentum px distribution, for laser pulse a = 1.0. The peaked distributions can tell us about the formation of the highly-relativistic electron beam and its energy distribution in the opposite direction to the laser propagation. The beam is created as the accelerated electrons are reflected and pulled back into the bulk plasma at the rear plasma-vacuum interface. In the third snapshot (Fig. 5), apart from the highly-relativistic beam, also the thermalized, momentum peak (px ≈ 20) is observed; because some accelerated electrons have already returned (recirculate) to the bulk from the rear boundary after one cycle. As in Figure 6, the angular energy distribution θ ∼ tan−1(py /px) of test electrons shows, the initial number of electrons which will be accelerated, which has angular energy distribution −90°–90° (moving forward, initially) is greater than that of 90°–270° (moving backward, initially). When accelerated in time, the electron angular distribution is mostly concentrated around two angles 90° and −270°, that is, |px| >> |py|; it demonstrates that electrons are accelerated mainly by the longitudinal waves.

Snapshots of longitudinal momentum distribution for incident laser pulse, a = 1.0.

Angular Energy-distribution θ ∼ tan−1(py /px) snapshots in the case of laser pulse, a = 1.0.

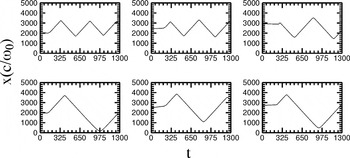

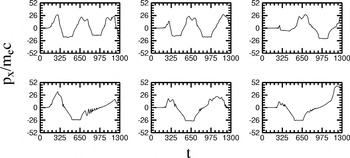

In order to better visualize, electron orbits in space are shown for six-test electrons chosen from all of the accelerated electrons. The time history of orbits x(t) and momentum px, is plotted in Figures 7 and 8, respectively. The scenarios shown in these two figures are consistent with our discussions above.

Time history of orbits x(t) for six representative test particles, in the case of laser pulse, a = 1.0.

Time history of longitudinal momentum px for six-test electrons, for laser pulse, a = 1.0.

When intense laser propagates in the low-density plasma, a large amplitude plasma wave is generated mainly by stimulated Raman scattering (Mima et al., 2001). Rapid SRS heating in forward direction produces a massive electron (cloud) blow-off into the vacuum region. The large electrostatic field builds up to drive return currents and accelerate the background electrons to high energies. As shown in Figure 4, for the electrostatic field Ex plots, at time t = 196.99 (the laser pulse has passed through the right boundary) SRS driven large plasma wave is propagating. At later times, as SRS gradually saturates, an intense narrow ES field structure (Debye sheath) with a steep gradient forms at each plasma interface. The maximum electrostatic field goes up to Exmax ≈ 0.18mω0 c/e. The electrons get accelerated backward by this sheath electric field, which spreads over the hot-electron Debye length (Mackinnon et al., 2002). Assuming that the electron with maximum energy is accelerated by the gradient field beyond the right boundary; the acceleration distance (Fig. 4, t = 321.46) roughly equals the plasma length L = 1000c/ω0. Electron experiences a linearly-increasing electrostatic field Ex(x) ∼ 0.0001x; the maximum gained electron energy is approximately, Emax ≈ ∫0L eEx(x) dx ≈ 50 MeV which well agrees with the result Emax ≈ 46 MeV, measured above. This leads to impressive effective accelerating electric fields of the order of hundreds of GV/m.

In our simulations, plasma density is taken as n = 0.01ncr, that is, the ratio of the laser to the plasma frequency is ω0 /ωp = 10, that is, the plasma wave period Tp = 10T0, where T0 is laser pulse period. As known, due to large ion inertia Mi = 1836me, the ion plasma frequency is only about ωion = (me /Mi)1/2ωp ≈ ωp /43, the ion plasma wave period Tion ≈ 43Tp = 430T0, 430 times the laser period, the total simulation time is about t ≈ 1300T0 ≈ 3Tion. Therefore, it seems plausible to neglect the ion dynamics, especially in the formation of the short high-quality, well-collimated return beam of relativistic electrons. Our additional PIC runs have proved that above assertion is correct.

4. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, we presented the mechanism of electron acceleration by intense laser pulse interacting with a low density plasma layer, examined by 1D-PIC simulations. The standard dephasing limit and the electron acceleration process were discussed. A new phenomenon of pulsed high-quality, well-collimated return relativistic electron beam, with thermal energy distribution, in the opposite direction to the laser propagation, was detected. It operates like a two-stage accelerator. In the initial phase: rapid electron heating by the SRS driven relativistic plasma wave allows a massive initial electron blow-off into a vacuum. Large potential Debye sheath fields are created which further accelerate electrons (second stage) to ultra-relativistic beam energies. The mechanism of the beam formation, beam characteristics, and the time-history in x and px space for test electrons in the beam, were analyzed and discussed clearly. The estimate for the maximum electron energy agreed with our 1D-PIC simulations. The influence of ion dynamics was briefly discussed. Finally, our results are expected to be of particular relevance for an exploding foil type of intense laser-plasma experiments and simulations (Malka et al., 1997; Hatchett et al., 2000; Mackinnon et al., 2002; Rousseaux et al., 2002; Santos et al., 2002; Sentoku et al., 2002).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in parts by the Ministry of Science, Technologies of Republic of Serbia under Project No. 1964. Stimulated discussions with Lj. Hadževski are gratefully acknowledged.

References

REFERENCES

Snapshots of electron energy distributions from 1D-PIC simulations. The plasma density is n = 0.01ncr.

Total electron momentum snapshots, in x − px phase-space from PIC simulation, for laser pulse, a = 1.0.

Test electron momentum snapshots, in x − px phase-space from PIC simulation, for laser pulse, a = 1.0.

Snapshots of electrostatic field Ex (normalized to mω0 c/e), in the case of laser pulse, a = 1.0.

Snapshots of longitudinal momentum distribution for incident laser pulse, a = 1.0.

Angular Energy-distribution θ ∼ tan−1(py /px) snapshots in the case of laser pulse, a = 1.0.

Time history of orbits x(t) for six representative test particles, in the case of laser pulse, a = 1.0.

Time history of longitudinal momentum px for six-test electrons, for laser pulse, a = 1.0.

- 12

- Cited by