To the memory of Gerhard Koeppel and Ronald Syme

The best-known monument of Augustan Rome is the Ara Pacis. It has been known in ‘modern’ times, in part at least, since 1568. The two reliefs on the long sides have traditionally been known as the ‘imperial frieze’ (south) and the ‘senatorial frieze’ (north), although this distinction has now been completely overthrown. It is the former which concerns us here.

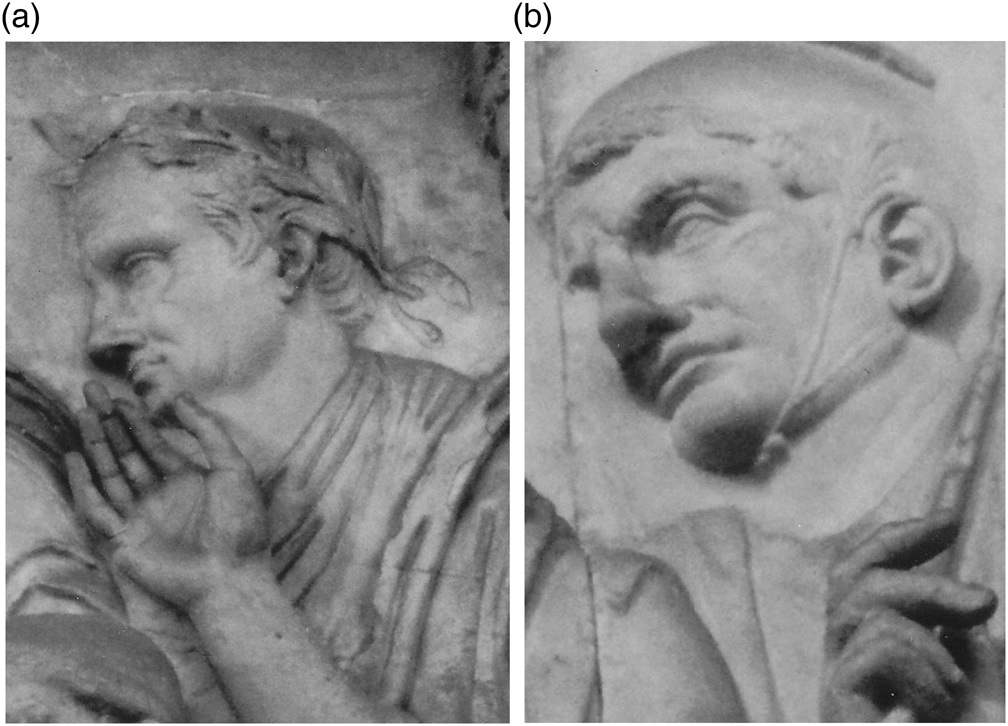

The southern procession comprises, as preserved, eighteen figures in the foreground and no fewer than sixteen in the background.Footnote 1 The foreground features three family groups: Agrippa and Julia (alternatively, Livia), Antonia Minor with husband and children, and Antonia Maior with the same. The figures of the two family groups are increasingly seen as idealized, although details such as dress and the children make identification next to certain. In the background of the last family group is the striking profile of a mature man (for ease of reference known technically as S44: fig. 1a). This is obviously the portrait of a real person, along with, as increasingly agreed, a few other veristic portraits.Footnote 2 Its identification is therefore crucial. Our investigation will take us from gem collections all over Europe, to the building of palaces in sixteenth-century Rome, to antiquarian scholarship from that century to the present, and to some of the most political archaeology in modern times.

Fig. 1. The portraits of (a) ‘Maecenas’ and of (b) the flamen Iulialis (Ara Pacis, southern frieze).

At this point it is important to include a disclaimer. The bibliography on the Ara Pacis is enormous,Footnote 3 but not by any means all of the discussions pay attention to the background figures, and specifically S44. Suffice to say that the following analysis includes all the best-known discussions, and many others, and every effort has been made to ensure that there is no proposed identification of this profile which has been omitted.

The purpose of the present study is to survey the history of the attempts to identify S44, the figure commonly thought to be Maecenas on the Ara Pacis. That history is centuries old and very complex, but most discussions have simply proposed an identity, much less frequently mounted a case for it.Footnote 4 The only hope for a convincing solution to this centuries-old problem is by understanding that complex history and carefully collecting both any evidence offered and the insights offered fitfully for understanding the nature of the historical friezes on the altar. There are, furthermore, basic historical tests that have not been applied to the many identifications. It is time to undertake these tasks; for they are the only way forward. The analysis is not without interest, finally, because so many leading antiquarians and art historians have been involved, and it is important to recover the true names of the scholars responsible for the major new turns in the discussion, who are so often unrecognized, and because of the number of serious misunderstandings of the evidence. Most extraordinary of all, however, will be the discovery that the most long-standing and persistent identification of S44 on the Ara Pacis as Maecenas relies on totally mistaken, in fact, non-existent ‘evidence’.

Why should Maecenas be of such perpetual interest? He is the most mysterious figure of the Augustan regime, indeed, persistently present, but in the background, so to speak.Footnote 5 Any reader of Horace, his closest friend, will be familiar with him, and so also will any reader of the main historical source on the regime, the third-century Dio Cassius, who of course relies on earlier sources, not to mention any reader of modern classics such as Ronald Syme's Roman Revolution. Maecenas was, along with Agrippa, one of Augustus’ closest supporters in his early years, vital not only as a diplomat, but also some kind of prefect of Italy in the late 30s, but then he retired from politics to become the leading literary patron of the time. It is, however, perhaps his personality which is the great fascination: of Etruscan princely descent, a man of great wealth, and exotic habits. We obviously would be very grateful to have a sculptured or relief portrait of him.

Engraved Gems and a Bust

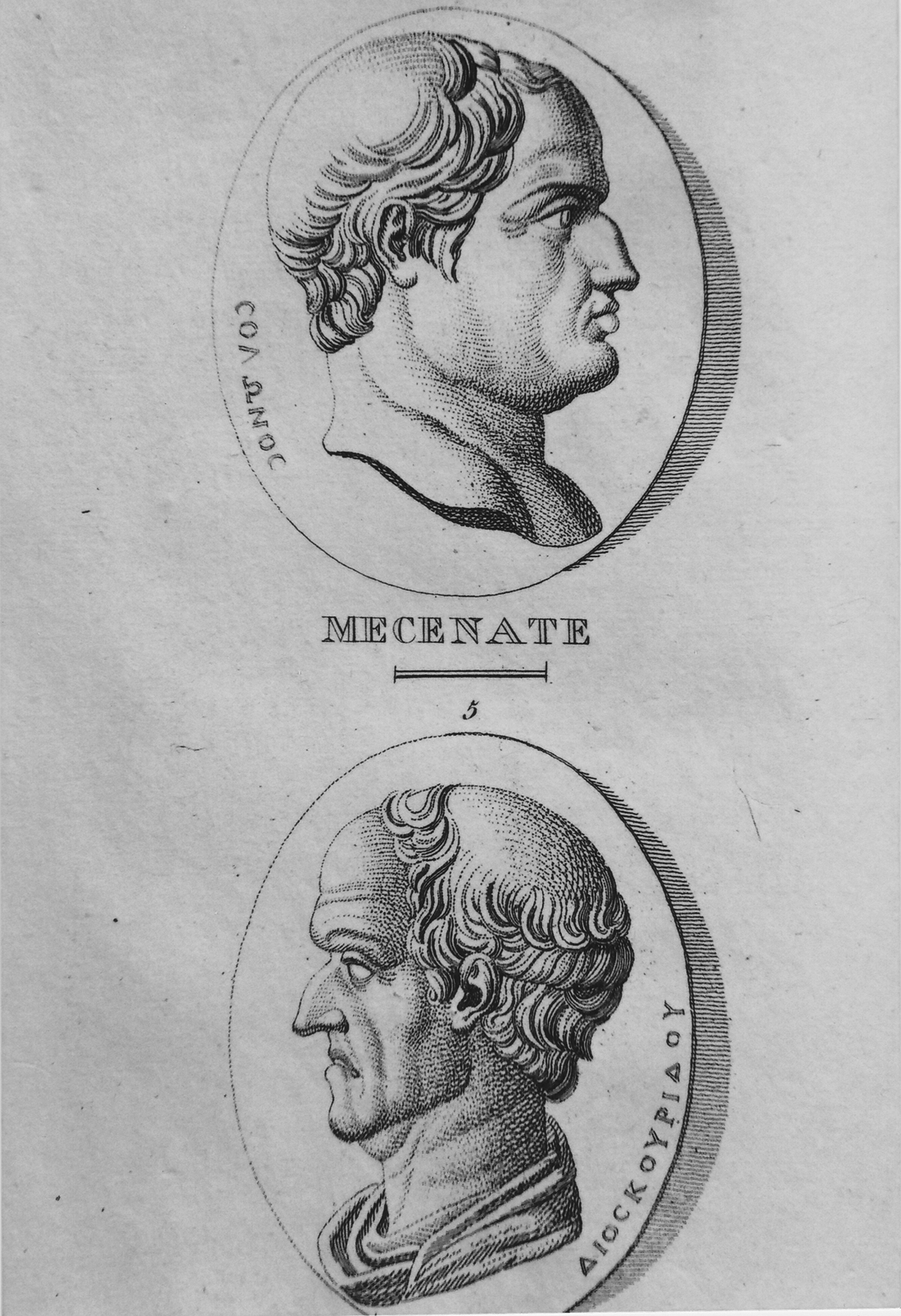

The search for Maecenas’ portrait begins in the sixteenth century with a famous pair of engraved gems (fig. 2).Footnote 6 One of them is an amethyst in the Cabinet des Medailles in Paris with the legend in Greek Διοσκουρίδου (‘of Dioskourides’);Footnote 7 the other a sardonyx then in the collection of Prince Piombino in Rome, this time with the Greek legend Σόλωνος (‘of Solon’).Footnote 8 The great sixteenth-century antiquarian Fulvio OrsiniFootnote 9 used the latter in his epoch-making Imagines et elogia virorum illustrium (Reference Orsini1570) to illustrate none other than the short biography of the Athenian legislator Solon: in other words, he mistook the artist's signature for the subject!Footnote 10

Fig. 2. The gems of Solon and Dioskourides from Visconti (Reference Visconti1818) pl.12.4–5.

Pierre Jean Mariette in his study of engraved gems in 1750 already identified some problems. He regarded both gems as portraits of Maecenas; the artists were working from nature: this was a living person. There were, however, differences in the hair, and considerable differences in ‘the accessory parts’, and they face in different directions.Footnote 11 The undisputed master antiquarian of his age, a veritable oracle, Johannes Winckelmann, in the first edition (1764) of his history of ancient art, identified the Dioskourides gem as ‘said to be Maecenas’.Footnote 12 Winckelmann also, at great pains to himself, catalogued one of the most famous gem collections of the time, that of Baron Philip von Stosch, which included paste copies of the two gems in question.Footnote 13 Winckelmann noted of the Dioskourides gem, that Stosch originally thought it represented Maecenas, but then changed his mind, and preferred to identify it as Cicero, as did Anton Gori, the great antiquarian in Florence.Footnote 14 The original of the Solon gem was at this time in the collection of Prince Ludovisi, with a similar one in the Ricciardi collection in Florence. In his study of gems and cameos engraved with the artists’ names, with bilingual commentary (Latin and Italian), Domenico Bracci analysed Maecenas’ work as a minister of Augustus, but gave no clue as to his authority for the identity of the portrait on the gem, which he accepted as Maecenas. He also discussed the gem in Rome which possibly showed the same profile. A different collection of sources was offered to explain the importance of Maecenas, but again no evidence for the identity of the engraved portrait.Footnote 15

Winckelmann's successor as the oracle, Ennio Quirino Visconti, in his Iconografia romana (1818) revealed something of the highest importance: that the identification of the portrait in Paris as Maecenas was, in fact, the result of ‘a happy conjecture by the Duc d'Orléans’. Visconti thus finally provided the documentation—a century late. The duke's conjecture had been conveyed to the Académie des Inscriptions by Baudelot de Dairval. After some uncharacteristic uncertainty whether the portrait might be Agrippa or even Pollio, Visconti returned to Maecenas. His supporting evidence was surprisingly thin, but at least he attempted to offer it: Maecenas attained the age shown in these portraits, gems were very important to him, and he was bald (Sen. Ep. 114)!Footnote 16

The crucial name had at last appeared: Philippe, Duc d'Orléans (1674–1723), regent for Louis XV, 1715–1723. This revelation pushes us back a century: a not unparalleled example of concealed documentation on this subject. As Louis XIV's nephew, he enjoyed a first-class, wide-ranging education, and was among other things, a composer, artist, and brilliant soldier. Such was the all-round expertise of a leading aristocrat at this time. Baudelot de Dairval, in fact, as long ago as Reference Baudelot de Dairval1717 in an essay on the Solon gems, had published an account of his discussions with the duke.Footnote 17 It seems indeed the latter who had already overturned earlier views by his impeccable logic. He first noted that a portrait of Solon would be ‘standard’, not at different ages, as shown by the gems bearing this name. Second, conversely, the same head is shown with different names: Solon and Dioskourides. He also knew, thirdly, of a Medusa and a gladiator accompanied by the name Solon. The engraved name on the gems was therefore that of the artist. Solon and Dioskourides were two Augustan stone-cutters. And the subject in question was, he suggested, Maecenas. All Baudelot could do was half-heartedly suggest Agrippa as an alternative, but then he had to admit that his coin-portraits were very different.

Heinrich von Köhler then initiated (unwittingly?) a new line of enquiry. He was mainly interested in showing that the Paris amethyst was a fake and to be distinguished from gems by Solon which depicted Maecenas.Footnote 18

One of the most scholarly analyses was given by Johann Jacob Bernoulli in 1882 in his study of Roman iconography.Footnote 19 Characteristic of his systematic approach, he was able to list six examples of gems of this type signed by Solon, all but one carnelians: in Naples; in the Ricciardi, then Poniatowski collection; in the Piombini-Ludovisi collection in Rome; in Vienna from the Barberini collection, and another carnelian and an amethyst in St Petersberg. Bernoulli agreed with Köhler that there were important differences between the men portrayed by the two artists: Solon's was younger, and most features as depicted were different. D'Orléans and Baudelot's argument was declared ‘insufficient’. Maecenas’ taste for gems was hardly any argument for his being shown on them! Bernoulli favoured rather Cicero or Lepidus.

A little later Salomon Reinach's treatise on engraved gems identified national divisions in this debate concerning the history of art. Both gems were described as ‘claimed to be Maecenas’ (‘le prétendu Mécène’). He supplied the history of the Paris amethyst: it first appeared c.1600 in the collection of Fulvio Orsini, then passed from Ragas de Bagarris, to Toussaint Lauthier, and finally to Louis XIV. German attempts to sort out four versions of the portrait were declared not to have eliminated confusion, and ‘nothing was less certain’ than German attempts to prove they were portraits of Cicero.Footnote 20

By 1900, in his classic study of ancient gems, Adolf Furtwängler could count four examples of the gem signed by Solon—but they were, he declared, all copies made in the sixteenth or seventeenth centuries. He focussed on the carnelian in Naples—and the new identity was again supported: ‘probably’ Cicero. The amethyst showed the same person as depicted on the carnelian, and was another fake of the same date, even if a copy of an antique original.Footnote 21 Furtwängler had, in fact, twelve years earlier dated the gems to the sixteenth or seventeenth centuries.Footnote 22 Gisela Richter, in her study of engraved gems, simply noted Furtwängler's judgement on the Dioskourides gem.Footnote 23

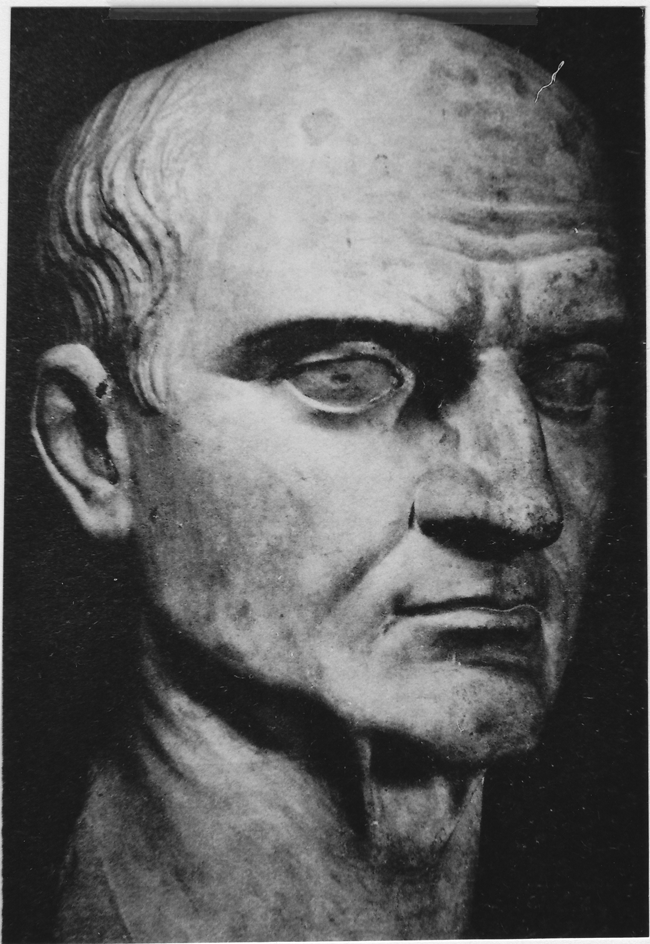

Adduced alongside the gems as a portrait of Maecenas, one must briefly note, was a colossal bust in the Capitoline Museum (Palazzo dei Conservatori), found or acquired by Pietro Manni on the via Flaminia between Narni and Todi (fig. 3).Footnote 24 This was therefore thought to have Etruscan connections, and Bernoulli linked it to Solon's gems. He admitted that it ‘accorded little, however, on the whole with our conception (Vorstellung) of Maecenas’. His first thought was of Galba, but if it were Republican, then perhaps it was a portrait of Sulla.Footnote 25 Henry Stuart Jones, on the other hand, described this head in the room of the Orti Mecenaziani, as ‘probably modern’. Its provenance was given as Carsulae. All of this did not, however, prevent Jean-Marie André, in his biography of Maecenas, from using this portrait as his frontispiece.Footnote 26 The fascination over centuries with the gems and the bust in the Capitoline ended, therefore, with their complete abandonment as fakes! The irony is that the virus had already affected studies of the Ara Pacis and would continue to do so well into the twentieth century.Footnote 27

Fig. 3. The large bust (Capitoline Museum) from Jones (Reference Jones1926) pl. 57.

The Frieze of the Ara Pacis

Two years before Fulvio Orsini's Imagines appeared, in 1568, a famous palace in the very centre of Rome was undergoing renovations: the Palazzo Peretti-Fiano. An early building on the site had been the home of the titular cardinals of the nearby church, S. Lorenzo in Lucina, one of whom, Cardinal Giorgio de Costa (1406–1508), was Portuguese; this name for the palace was then also attached to the nearby arch which then spanned the Corso. The palace was bought by Prince Michele Peretti in 1624, and by the Ottoboni, dukes of Fiano, in 1690. The building was most famous, however, for being built on top of the Ara Pacis Augustae. In 1568 excavation revealed for the first time the remains of the altar, including the panel at the end of the southern (‘imperial’) procession showing Antonia Maior and her husband, and the striking profile between them in the background. This was among nine pieces of the altar bought by Cardinal Giovanni Ricci di Montepulciano (1498–1574) from Camillo Bolognino for 125 scudi, and sold to the Medici in 1576, whereupon they passed to the villa on the Pincian, whence in 1782 they were exported to the Grand Ducal collection in Florence.Footnote 28 Their perpetual interest to art historians, however, was occasioned by the twentieth-century excavations undertaken from 1903 in order to extract the other pieces of the altar and reconstruct it, as far as possible, in its entirety.

The identity of the striking figure of the old man towards the end of the southern procession (fig. 1a) henceforth assumed great importance.Footnote 29 The field started very wide. A permanent feature was to be the failure, almost universally, to offer any supporting evidence for the identification proposed. Hans von Dütschke in 1880 suggested that ‘the figure of a doctor or other friend of the imperial house would not be inappropriate in this place’.Footnote 30 Luigi Milani next, in 1891, in a discussion of portraits of Drusus, plumped for none other than Ti. Claudius Nero, father of Tiberius and Drusus.Footnote 31 Walter Amelung, expert in Greek sculpture, in his guide to the Florentine museums, was interested only in the main figures.Footnote 32 Fritz Wickhoff, the Viennese art historian, in his study of Roman art, suggested that the background figures were treated as ‘cameos’,Footnote 33 presumably meaning small individual portraits—but that hardly seems to take us further. Why would the background figures be more realistic than the much larger foreground ones? Anton Domaszewski, the Austrian Roman historian, was naturally interested mainly in the family groups, but in 1903 identified the profile in the background as simply ‘a man’.Footnote 34 In the same year, Henry Stuart Jones, another historian, offered nothing on any of the background figures.Footnote 35

The first modern excavation of the altar was in 1903. The dominant figure in these excavations was Eugen Petersen.Footnote 36 He defined the man's characteristics: the deep furrows on forehead and neck, and sparse hair; he seemed stooped. He was obviously an old man—but Petersen went much further: this was a family group, consisting of grandfather, father, mother and daughter: was he Ahenobarbus’ father?Footnote 37 The merest acquaintance with the history of the Ahenobarbi, however, would rule this out: Ahenobarbus, husband of Antonia Maior, was the son of the consul of 32 BC, an old Republican, who had made his peace with Octavian, but who died about 31.

Tucked away in a very long footnote in Petersen's monograph were comments by Otto Benndorf, who is often credited with the identification with Maecenas. This is not so: he simply quoted, without reference, Robert von Schneider's view that it was Maecenas—by comparison with the Dioskourides gem!Footnote 38

Here, therefore, is the man who offered the identification which was to hold sway for a century. Robert von Schneider (1854–1909) was an Austrian archaeologist, director of antiquities in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna from 1899 (when he had to deal with the enormous influx of finds from the excavations at Ephesos), and successor of his teacher Otto Benndorf as director of the Österreichisches Archäologisches Institut from 1907.

A mere four years later, however, for Petersen our figure had become ‘probably Maecenas’.Footnote 39 Eugenie Strong, English art historian, and student of Furtwängler, noted ‘a number of figures in the background—probably dependents or attendants—all wearing festal wreaths.’ She offered no identity for our man, but admitted that one scholar thought him Maecenas, ‘as known from his portrait on the gem engraved by Dioscorides’ [sic]: this scholar is obviously von Schneider.Footnote 40 The leading biographer of Augustus at this time, Viktor Gardthausen, in his magnum opus gave only a general description of the processional friezes, but in a more specialist study of the altar (Reference Gardthausen1907) averred, without discussion, that the profile was certainly not Maecenas.Footnote 41

In a substantial discussion in 1909, Franz Studniczka, the Austrian art historian, dismissed the identification with Maecenas as ‘an unfounded assumption’. He referred for the first time to the artistic evidence, the analysis of which we have followed for four centuries: there was no evidence from the Dioskourides gem, and the colossal head in the Conservatori has been reworked. Studniczka's candidate was the uncle of Julia Maior's husband, Domitius Ahenobarbus, without further amplification—indeed, without even naming him!Footnote 42 The idea of an uncle would, however, bear fruit in another three-quarters of a century. In the same year, Salomon Reinach wrote of ‘very doubtful identifications’, but he offered nothing on the old man.Footnote 43 The last edition in Walter Helbig's lifetime of his classic guide to Roman museums, the third, concentrated mainly on the mythological end panels.Footnote 44 A leading Italian art historian, Pericle Ducati, in a general history of classical art, was mainly interested in the figures around Agrippa, and more so in the floral section below.Footnote 45 The Austrian art historian Emanuel Löwy in Reference Löwy1926, in a brief article full of interesting observations on the figures in the friezes, strangely paid no attention to S44.Footnote 46

The small guidebook to the altar (1932) of Roberto Paribeni (Director-General of Antiquities and Fine Arts 1928–1932, and who was to play a leading role in attempting—vainly—to obtain the return of the Louvre fragments of the altar for the Fascist reconstruction) was too brief for such details.Footnote 47 Giuseppe Lugli, famed Roman topographer, ‘waiting for the new excavations’, would venture only that this portrait was, ‘according to some’, Maecenas.Footnote 48 Ermanno Ponti, writer in the 1930s on Roman topography, however, in his monograph on the altar (1938), plumped for Maecenas, returning to comparisons with the amethyst in Paris and the colossal head in the Conservatori!Footnote 49

The spectacular excavations under the Palazzo Fiano conducted in 1936 by Giuseppe Moretti finally retrieved all the fragments and the reconstruction provided a Fascist triumph for the Augustan bi-millenary. His beautiful monograph did not appear, however, for another twelve years. He initially stated simply that the head was Maecenas, but later offered special and unusual analysis. He noted the ‘evident realism’ and suggested that this was the oldest figure in the procession: he was even a little bent. The figure was marked by ‘a conscious but not emotional participation’, ‘not caring about the others’. As for the identity, however, he simply listed others who agreed that it was Maecenas: Benndorf, Petersen, Strong, and Paribeni.Footnote 50 At the very same time Jean Charbonneaux, professor of classical archaeology at the Louvre, in a specialist study of Augustan art, gave no details in his description of the procession.Footnote 51 Inez Scott Ryberg, American archaeologist and historian of art and architecture, although concentrating on the procession, was interested in only the first major figures: Augustus, Agrippa, and Livia.Footnote 52 Ian Richmond, director of the BSR 1930–1932, responded directly to Moretti's discussion. His identification was ‘on the whole unlikely’, because Maecenas was ‘in eclipse’ by 13 BC: ‘If he was accorded a place on the relief at all, he might rather be expected on the north side.’Footnote 53 This all made good sense. Another English art historian, Jocelyn Toynbee, four years later, however, considered that Maecenas was ‘just possible’.Footnote 54 In a monograph on the altar (1957), Ludwig Budde, a German archaeologist who excavated mainly in Turkey, offered no identification.Footnote 55 Hans Riemann, another German archaeologist, provided a classic reference point in his article on the altar in Pauly-Wissowa. He stated simply that there was no evidence for the identification with Maecenas.Footnote 56 The Swedish historian Krister Hanell, in a lengthy discussion of the frieze, did not go beyond identifying Livia, Tiberius, Drusus, and Antonia.Footnote 57

Another art historian, Antonio Frova, in his handbook of Roman art, raised for the first time the whole question of the nature of the ‘portraits’ on the frieze. His argument, however, was inherently illogical: that the artist did not aim at a minute reproduction of physical traits, because a ‘generic’ interpretation was enough for contemporaries, to whom all these people were well known! Women and children, he claimed, especially tended to be ‘classical stereotypes’.Footnote 58 The question raised, however, was important: how far did the figures on the frieze exhibit individual traits? It is hard to imagine a monument such as this, clearly parading the Augustan dynasty, without the portraits being meant to be identified.

The first of four modern biographies of Maecenas appeared in 1962, by Riccardo Avallone, who had been publishing on this figure for a decade. He seems totally uninterested in portraits.Footnote 59 Erika Simon, a broad-ranging German classical scholar, published the first edition of her handbook on the Ara Pacis in 1967, although it is notoriously undated within the covers. She rightly referred to the ‘striking old man's profile’ and stated that ‘it is most probably the portrait of a particular personality, but the suggestion that it is Maecenas is unfortunately without foundation.’ Having dismissed one view for lack of evidence, she then proposed an entirely new candidate: the poet Horace!Footnote 60 The next year, in one of the most attractive books on the Augustan age, the English classical historian Donald Earl returned to Maecenas: ‘Although only equestrian in rank, he had served Augustus and the pax Augusta well enough to be allowed to walk in the procession,’ and it ‘looks like a portrait from life’, he added.Footnote 61

The question of individuality was raised again by Adolf Barbein. The portraits were idealized rather than realistic, in his view. He thought that only Augustus and Agrippa were sure.Footnote 62 This approach was taken to even higher levels the very next year, when the Maltese archaeologist Anthony Bonanno, in a specialist study of Roman relief portraiture, went so far as to state that, apart from Augustus and Lepidus [sic: the pontifex maximus in disgrace and exile],Footnote 63 ‘the other heads are treated in such a generalized way that none of them can be reliably identified on the basis of the facial features or hairstyles alone or by comparison with other portraits. … It is almost impossible to distinguish one female figure from another’. This judgement then led to paradox: the figure in the background was highly individual: he was ‘an old man with very realistic marks of his age: wrinkles, flabby flesh with folds around the mouth and on the jaw, and balding hair. Incisions mark both eyebrow and iris.’ Bonanno's conclusion about the common identification with Maecenas was, however, irrefutable: ‘No one has yet provided solid evidence to prove it, since we do not have any reliable portraits of Maecenas.’Footnote 64 Two years later, Bernard Andreae, who would go on to be director of the German Archaeological Institute (1984–1995), took the problem of individual portraits to its extreme: ‘to judge by what one sees here, it must have been the aim of both patron and artist to provide an unmistakable likeness of only Agrippa’! This suggests that even Augustus was to have remained undetectable, but Andreae then contradicted himself by admitting that ‘the immediate family of the emperor…[was] spread throughout the last third of the frieze’, and that it was Maecenas, ‘whose diplomatic skills and proverbial patronage of the arts had an inestimable influence toward making the Augustan age what it was’.Footnote 65 Diana Kleiner, professor of Roman art and archaeology at Columbia, in her study of the frieze, was interested only in the parallel in the Parthenon frieze and Greek and Roman funerary scenes; in her handbook of Roman sculpture, she ventured only that it showed ‘Agrippa and the imperial family’.Footnote 66

The question of the lack of definitive portraits in the frieze continued to occupy art historians. Mario Torelli, specialist in Italian archaeology and Etruscology, in a study of Roman reliefs, quadrupled Andrea's estimate. Only four heads have ‘distinctive physiognomic traits’: Augustus, Agrippa, the flamen Iulialis (fig. 1b), and ‘Maecenas’ (one notes that half of these individuals are in the background). These figures were patres familias, sui iuris. The flamen he identified as Appuleius the Elder, and he suggested that the so-called Maecenas figure was his younger son, Sextus Appuleius the Younger (cos. 20 BC)—who was, of course, therefore, not sui iuris! Footnote 67 Paul Zanker, specialist in Roman historical reliefs and Augustan culture, merely identified Antonia Minor with Drusus and children (the preceding family group), and ‘behind, other members of the imperial house’.Footnote 68

Another monograph on the altar, by Eugenio La Rocca, a leading Italian archaeologist, appeared in 1983. He offered a new insight: the old man crowned with laurel was one of only two figures in the background distinguished by his physiognomy: the other was the flamen Sextus Appuleius. He was, however, unlikely to be Maecenas, because he had no blood ties with the family of Augustus. He was rather Sex. Appuleius (the Elder), the husband of Octavia.Footnote 69

After the uncertainties about virtually any identifications, Ross Holloway, the American archaeologist of ancient Italy, agreed that the identity of the family groups following Augustus ‘defies definitive solution’, but he saw rightly that the children were the key: they are literally attached to their parents. To this we must add that they are identifiable also by age and demeanour. Holloway suggested that the four men in the background might be the husbands of the Marcellae: he hesitantly agreed with La Rocca that our man might be Appuleius the Elder.Footnote 70

Another candidate with imperial connections entered the field in 1984, proposed by none other than Ronald Syme: Paullus Aemilius Lepidus (cos. suff. 34), the censor (22 BC). ‘For either [Maecenas or Horace] to parade in an aristocratic gallery is exorbitant.’ One would expect rather a consular attached to the imperial house. Paullus was soon to marry the younger Marcella, and he would be near Ahenobarbus, whose mother, Aemilia Paulla, was his sister.Footnote 71 For Hans Goette, the special trait was the triple lock of hair in front of the ear, and the naturalness and realism, even in contrast to some of the people shown more completely. Although Maecenas had represented Octavian in Italy in the 30s, Goette preferred Horace, important because of his Carmen Saeculare.Footnote 72 Niels Hannestad, the Danish specialist in Roman art and architecture, would admit only that this figure ‘goes under the name of Maecenas’. He was notable for his ‘individual physiognomy, whereas the family proper appears as a homogeneous mass of ideal types’.Footnote 73 In a very detailed study of historical relief the next year, Gerhard Koeppel mentioned something so far unnoticed, that the nose and ear had been restored, but offered no identification.Footnote 74 Eminent art historian John Pollini favoured Appuleius the Elder, suggesting that his wife, Octavia Maior, Augustus’ half-sister, might be the ‘old woman looking backwards’ on the northern side (N42), which, according to his view that the northern and southern friezes are two sides of the same procession, would place her about opposite this intriguing profile. The flamen Iulialis near Augustus would be Appuleius’ son.Footnote 75 In the catalogue which accompanied the great Berlin exhibition of 1988, however, Salvatore Settis, an art historian who spanned from antiquity to the modern age, gave a brief list of the main figures and declared that the man in the background ‘remains unknown’. Footnote 76

Richard Billows, the American Hellenistic historian, focussed on the date of the altar: not its constitutio (13), or its dedicatio (9), but as a supplicatio, for successes (RG 12). He was therefore most interested in the priests.Footnote 77 Paul Rehak stressed the many changes in personal situations that occurred between 13 and 9 BC, and the possible connected development of the frieze. He focussed on the flamen Iulialis, who, he suggested, was originally a background togatus, but he only hinted that it was Augustus’ brother-in-law, and passed over the old man.Footnote 78 Diane Conlin, American specialist in Roman marble carving, in a most instructive study of the hands of the different artists detectable in the sculptures, paid much attention to the ‘elderly male’, ‘a realistic, individualized portrait of an elderly hunched man’ between the ‘generalized heads’ of the female and male figures in the foreground. ‘Similar to the figure of Agrippa, the head of S44 displays the wrinkles and sagging folds of age, particularly above the nasolabial furrow and along the line of the jaw, and the deep-set eye sockets.’ She further suggested that the profile was not aligned with the torso. Further she would not go.Footnote 79

The end of the century saw another clutch of monographs. Maria Laura Cafiero was little interested in identifications.Footnote 80 Emanuela Bianchi again noted that Maecenas had no blood-ties with the dynasty to justify his presence: some scholars therefore nominated Sextus Appuleius (the Elder), the husband of Octavia.Footnote 81 The German classical archaeologist Alexander Mlasowsky agreed that the flamen Iulialis (S22) was Appuleius the Younger, and went on to adduce a new argument: there is a resemblance between him and the old man (S44), who could therefore be Appuleius the Elder.Footnote 82 Orietta Rossini, in the handbook of the museum on the altar, similarly declared that the old man was ‘traditionally identified as Sextus Appuleius pater’, whom she goes on to identify as the consul for 29.Footnote 83 Two observations may be made: there is nothing ‘traditional’ in this identification, and the Elder was not consul in 29: that was his son, usually taken to be the flamen. Erika Simon, on the other hand, published the second edition of her study of the altar, and now declared that, although the portrait was ‘striking’, its identity was based only on suppositions; ‘so he here shall remain nameless’.Footnote 84

In the midst of these recent specialist studies on the altar, Bernard Andreae returned to the problem, publishing a very important article on Maecenas, based on his identification of the Arezzo portrait (known since 1958 and identified as Drusus) as Maecenas.Footnote 85 He then firmly identified this portrait with that on the Ara Pacis. The latter is a decade older, but they are different in almost every detail: the prominent bone structure of the inner eyebrows of the Arezzo portrait, its much lower forehead (the altar profile is not bald), the totally different hair styles, different ears, the different shape of the skulls, and the very distinctive hair style in front of the profile's ear. Andreae links Maecenas with Agrippa on the altar, ignoring the crucial difference that the latter was one of Augustus’ closest relatives. And given Andreae's fascination with the rift between Maecenas and Augustus by 16 BC, we would hardly expect him on the altar dated 13–9 BC.

Two biographies of Maecenas have recently appeared. Philippe Le Doze means by ‘portrait’ his character, while Peter Mountford still finds Maecenas on the Ara Pacis.Footnote 86

Putting the Jigsaw Together

What criteria may be said to have emerged in these debates since the beginning of last century? One can only remain amazed at the poverty of the results, and they have mostly been discovered in recent work. Much of the scholarship of the twentieth century, it is to be noted, refrained from identification. Most writers have been content to stress—with good reason—only the realism of this profile in the background. Torelli counted that it was one of only four portraits so marked in the southern frieze. The most significant of the other three was none other than that of the flamen Iulialis (and so La Rocca). Mlasowsky has made the further interesting suggestion of a family resemblance between the flamen and the old man. The second basic agreement to emerge has been that all figures should belong to the imperial family by blood or marriage.Footnote 87 This seems cogent as a generalisation but does not always work with some of the background figures, as we shall see. Earl and Andreae especially argued for Maecenas’ importance, despite the lack of blood-ties. He has been, in fact, the dominant identification until very recently. The lack of argumentation, however, suggests that this was more a matter of fashion than of analysis.

There are two ways in which the investigation may be focussed and tested—and they have not been undertaken. Who, first, were the families connected with the imperial family? In alphabetical order they are:

1. The Aemilii Lepidi

M. Paullus Lepidus (cos. suff. 34, censor 22: PIR A373) was nephew of the triumvir, and maternal uncle of Antonia Maior's husband Ahenobarbus, that is, brother of his mother, Aemilia Lepida.Footnote 88 He married first Cornelia, daughter of Scipio (cos. 39) and Scribonia, and therefore Augustus’ step-daughter; then a much closer relative, Augustus’ niece Marcella, after the death of her husband Messalla Appianus in 12 BC. Lepidus’ career had been turbulent: he had been proscribed in 43 but joined Octavian in 38: hence the consulship four years later. He was therefore important as an early convert to the Caesarian side, to be prized. His censorship, however, was a shambles (Suet. Aug. 64, Dio Cass. 54.2.2)—and presumably disappointed Augustus’ plans. Augustus, nevertheless, did him a remarkable favour: he completed the rebuilding of the Basilica Aemilia (Dio Cass. 54.24.2–3), taking it therefore into his own much vaunted building programme. He was Studniczka's and Syme's candidate for S44, although in the first case anonymously and, in the second, almost en passant.

His son, L. Aemilius Paullus (cos. AD 1: PIR A391), married Augustus’ grand-daughter Julia, who was banished in AD 8. Nothing is known about his career apart from his consulship. He is usually thought to have perished around the time of his wife's disgrace, but Syme has argued that he survived until 13/14, when he was replaced as augur.Footnote 89

2. The Appulei

Two members are in play, both with the same name: Sextus Appuleius (the Elder) (PIR A960), husband of Octavia the Elder (she was daughter of C. Octavius and Ancharia, and therefore Augustus’ half-sister), but about whose career nothing is known, if he is not the flamen. He has been a popular choice: La Rocca, Holloway, Pollini, and Mlasowsky, amongst others.

His son, Augustus’ nephew, was very prominent under the regime: Sextus Appuleius (the Younger) (PIR A961), consul in 29, augur, proconsul in Spain and Asia, and later Illyricum. He was associated with Maecenas, it is intriguing to note, as defence counsel in an adultery trial (Dio Cass. 54.30.4). He was the choice of Torelli.

One of these two is the flamen Iulialis (S22): the question is, which one? The famous inscription (CIL 8.24583) mentions an Appuleius as flamen and his burial in the dynastic mausoleum. Most modern scholars favour the Elder, but he would seem by the time of the altar (whether it is 13 or 9 BC or thereabouts) to be far too old for the man shown as flamen. Footnote 90

3. The Claudii Marcelli

C. Claudius Marcellus (cos. 50), who married Octavia the Younger, Augustus’ sister; he died in 40.

M. Claudius Marcellus, their son, and Augustus’ favourite nephew, died in 23. Neither is therefore in contention here. Their daughter, Marcella the Elder (PIR C1102), married (1) Agrippa (28–21), (2) Iullus Antonius (executed 2 BC). Marcella the Younger (PIR C1103) married (1) M. Valerius Appianus (cos. 12 BC) and (2) M. Paullus Lepidus (cos. 34: already listed under the Aemilii Lepidi).

4. The Domitii Ahenobarbi

L. Domitius Ahenobarbus (cos. 16: PIR D129), who married Antonia the Elder. He is on the frieze (S45), with his wife and children. He was a leading commander in Illyricum (7–2) and Germany, and he died in AD 25 (Tac. Ann. 4.44). He was the son of the leading Antonian Cn. Domitius Ahenobarbus (cos. 32), who died the next year. For his maternal uncle, see the Aemilii Lepidi.

It is obvious that the Appulei are leading candidates for inclusion, both by propinquity to the imperial family and religious office. It looks most plausible that the Younger appears as flamen, while his father, despite his obscure career, is very closely related to Augustus by marriage.

The other test is to consider the background figures on the southern frieze, in order to seek patterns. As well as the ‘elderly male’ between Antonia Maior and her husband Ahenobarbus, there are two other famous figures:

1. The woman between Agrippa and Livia, who places her hand on the child's head in front of her (S29), and

2. The woman between Antonia the Younger and her husband Drusus, who places her finger on her lips (S36).

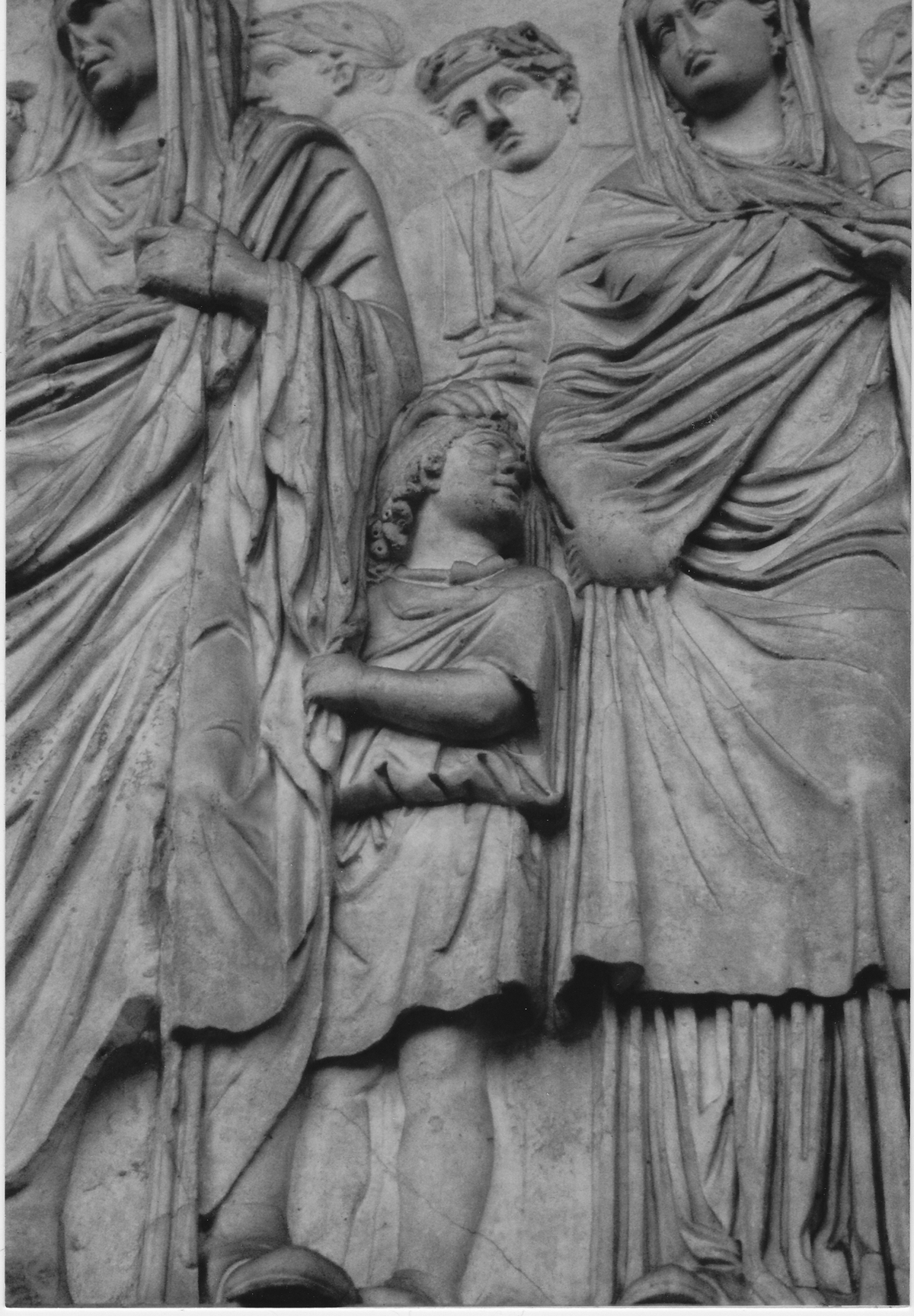

The former (fig. 4) has been endowed with a bewildering range of identities. She was a maid (Studniczka) or a nurse (Ducati).Footnote 91 If the most prominent woman is Julia, Agrippa's wife, rather than Livia, then she might be placing her hand on her son's head (Ducati, Moretti).Footnote 92 Since the 1960s, however, the most momentous change of all in interpreting the altar has taken place, namely regarding the two processional friezes. The child clutching Agrippa's cloak has been identified not as his son, but as a barbarian prince, and the woman as his mother (Simon, Rose), or an Oriental hostage, such as Antiochos III, and the woman as his mother, Iotape I or Dynamis (Mlasowsky).Footnote 93

Fig. 4. The woman with hand on a child's head following Agrippa (Ara Pacis: southern frieze).

In an exhaustive analysis, however, La Rocca concentrated on her distinctive headdress, a combination of mitra and laurel, recalling Dionysos and Apollo, to see her as a divine figure. The context is also crucial, next to the deceased Agrippa. She places her hand on the head of Gaius Caesar, blessing the imperial heir, now that his father is dead.Footnote 94 This would constitute a fundamental reorientation in our interpretation of the altar: the first divine figures in the ‘imperial’ procession. Otherwise divinities are restricted to the end panels.

The woman with her finger to her lips, remarkable for her full-face portrait (fig. 5), has also been taken to be any one of several very different persons: simply a matrona (Strudniczka),Footnote 95 Octavia the Younger, mother of Antonia the Younger nearby (Moretti),Footnote 96 a priestly woman imposing silence (favete linguis: Simon),Footnote 97 or a personification of death (La Rocca). More recently, the last scholar, again after providing a most impressive collection of similar gestures of hand to face, has suggested that this is not an invitation to silence but ‘a sign of veneration and prayer’ in connection with Drusus’ death.Footnote 98 There is only one problem with this: the altar was consecrated on 30 January 9 BC, but Drusus did not die until September.Footnote 99

Fig. 5. The woman with finger to lips between Antonia Minor and Drusus (Ara Pacis: southern frieze).

Most of these suggested identifications of the women in the background, it must be noted, destroy the rule that everyone on the frieze must be a connection of the imperial family. Equally important, they undermine any attempt to reveal any pattern connecting these three striking background figures.

One fundamental matter regarding the frieze has been seen and discussed since the 1960s: the question of individualism or realism in the portraits. It seems to have become accepted that few of the figures even in the ‘imperial’ frieze are shown as individuals: only Agrippa (Andreae Reference Andreae1978), only Augustus and Agrippa (Barbein Reference Barbein1975), these two and the flamen Iulialis and our man (Torelli 1975). An examination of the two Antoniae and their husbands bears out this lack of distinctive facial features. The procession did, however, depict the imperial family, and there was clearly a need for viewers to be able to recognize the participants in the events of a very important and specific historical and religious ceremony. Not to mention that the dynasty was on high show. The two Antoniae and their husbands were, in fact, easily recognisable: Drusus was wearing a military cloak, Ahenobarbus a toga. And, if that did not suffice, as Holloway (Reference Holloway and Bonacasa1984) stressed, their children were the key.

In striking contrast, S44 bears ‘very realistic marks of his age: wrinkles, flabby flesh with folds around the mouth and the jaw, and balding hair. Incisions mark both eyebrow and iris’ (Bonanno Reference Bonanno1976). Most striking of all, perhaps, Goette (Reference Goette1985) pointed to the triple lock of hair in front of the ear. To wrinkles and folds and arrangement of hair, Conlin (Reference Conlin1997) added deep-set eye sockets.

Conclusion

The search for a likeness of Maecenas first centred on gems, where at first—incredibly—there was a confusion between subject and artist, until none other than the regent of France suggested Maecenas, accepted by authorities as renowned as Winckelmann and Visconti, until the great Furtwängler showed the gems were modern fakes. The rediscovered end of the imperial frieze from the Ara Pacis came into play, in fact, from 1568, but questions of identity became pressing after the modern excavations of 1903 and 1936. For our figure, Schneider (d. 1909) suggested Maecenas, a Lepidus goes back to Strudniczka (1909), and an Appuleius to Torelli (Reference Torelli1982). Alongside Maecenas, however, there have been champions of Horace.

The above journey in scholarship should serve to alert us to how subject we are at all times to current understanding. The choice, then, as things stand, for the identification of our background profile, if we wish to keep connections with the Augustan family as our fundamental guide, should be between Sextus Appuleius the Elder (husband of Augustus’ half-sister) and M. Paullus Lepidus (husband of Augustus’ niece Marcella, and maternal uncle of Ahenobarbus, the husband of Augustus’ niece Antonia the Elder). Mlasowsky attempted to link this portrait with that of the flamen Iulialis—whichever Appuleius it is—both in physiognomy and in the fact that they are linked by being at once such striking portraits, yet both in the background. There are, however, fundamental differences. In terms of career, nothing is known of Appuleius, while Lepidus came from one of the most famous families, a prize acquisition by Augustus early in the civil wars, and a man he obviously connected closely with his domestic policies. On propinquity to Augustus in terms of family, Appuleius was husband to his half-sister, but Lepidus was granted two marriages into the family: the first to Augustus’ step-daughter Cornelia, the second, much closer, to his niece, Marcella the Younger, precisely at this time when the altar was being built. A neat clinching argument is the unity of the family group, as suggested by Petersen in 1902, of Antonia the Elder and Ahenobarbus, if the old man between them is his uncle. Why would anyone be placed between them precisely in this manner, if there were no connection? On the evidence we have the old man in the background is Lepidus, as suggested, without naming him, by Studniczka in 1909, and without close analysis by Syme in 1986.

The journey in scholarship which we have reconstructed remains, however, extraordinary in its paradoxes. A number of gems and sculptures were identified, entirely on grounds of guesswork, as Maecenas. This then infected the interpretation of the figures on the Ara Pacis. Precisely when this monument was being reconstructed at the beginning of the last century, these gems and sculptures were finally shown to be fakes, having nothing to do with Maecenas. The connection was, however, so tenacious that it has taken another half a century for alternative identities to be proposed! A second paradox is that, while there has been lively argument about whether the main figures were meant to be individual portraits, it is precisely two of the background figures which are agreed to be unmistakably individual, and yet they are among the most contested identities in the whole frieze.

Acknowledgments

I should like to thank the two readers for Antichthon, who, in very different ways, gave me much very useful guidance. A special thank you also to the eagle-eye of the editor, Robert Cowan.