Biographies, whether of persons or of commodities, tend to focus on cases deemed successful, or at least important, in the long run. Hence fruitful attention has been paid to sugar, shoes, cotton, chocolate, tobacco, the lure of the emerald, and the protein-rich ‘beauty’ of cod, to cite a number of influential commodity biographies.Footnote 1 With respect to the Caribbean, in particular, sugar has been the primary focus, and has overshadowed the early modern travel companion considered in the following pages. Like other, better-studied products, ginger defied proto-national categories and imperial designs in its movements across frontiers. Unlike ginger exported from Asia, which was packed in boxes and covered with clay, Caribbean ginger from the Antilles reached Europe mainly in cattle hides, which were coveted in their own right. From the mid sixteenth century until the mid seventeenth, ginger and hides produced in abundance on Hispaniola and Puerto Rico reached Europe through legal channels as well as contraband trade, stimulating a taste for Caribbean goods in England and the Low Countries before the large-scale exploitation of sugar plantations. Ginger defied early mercantilist policies and aspirations: produced in the Spanish Antilles, it found more of a demand in England and the Low Countries than in Castile.

As early as 1956, Pierre and Huguette Chaunu called attention to a boom in ginger exports to Europe from the Caribbean, even exceeding those of sugar in terms of value during certain years from 1581 to 1615.Footnote 2 Using the returns of the customs office at Seville, they documented a rise, followed by an apparent eclipse, of registered exports in Caribbean ginger.Footnote 3 Moreover, the Chaunus recorded huge fluctuations in the amount of ginger registered in Seville from one year to another, undoubtedly due to the incomplete and erratic nature of the data preserved. An even more significant gap emerged between the official figures reported to Seville’s House of Trade (from a high of 9,580 quintalsFootnote 4 in 1584 to a low of 947.65 quintals in 1594) and those recorded by the Venetian ambassadors (as high as 22,000 quintals in 1587 and 17,261 quintal in 1607), who were likely to account for some contraband, as Michel Morineau subsequently demonstrated in his analysis of silver remittances including contraband reported in Dutch Gazettes.Footnote 5 Much ginger, like silver, clearly went undeclared and hence unmeasured.

As ginger production boomed on Hispaniola and Puerto Rico, large variations in the amount of the spice recorded as entering Seville suggest that unknown quantities of Caribbean ginger may have reached Europe, including areas outside Spain, without being registered in Seville. In this sense, ginger defied the Spanish ‘monopoly’ or mercantile system in which colonies were supposed to produce goods consumed in the metropole. Instead the spice linked competing political economies. Its production and consumption, moreover, entwined with those of other Caribbean commodities including hides, sugar, and slaves.

While derived from incomplete and irregular sources, the Chaunus’ numbers called attention to the production and export of ginger, and enabled the Dominican historian Robert Cassá to place records of ginger that reached Seville in perspective by calculating its proportionate value in terms of Hispaniola’s annual recorded exports in the 1580s, as seen in Figure 1. The data presented by Cassá and the Chaunus, complemented by my own from the General Archive of the Indies, calls attention to the important, yet seemingly erratic and relatively short-lived, exports of ginger from Hispaniola to Seville and reveals the high value of ginger per pound with respect to that of sugar and hides, as well as the greater volatility in ginger’s price in Seville, which Figure 2 illustrates.

Figure 1 Percentage value of exports from Hispaniola to Seville in the 1580s: sugar, ginger, and hides (in maravedíes). Source: Cassá, Historia social, vol. 1, p. 102.

Figure 2 Price (in maravedíes) of American ginger, sugar and hides in Seville, 1580–1640. Note that the prices of goods have not been adjusted for inflation, since they were destined mainly for re-exportation rather than local consumption, and the purpose here is to compare them to each other. Sources: Chaunu and Chaunu, Seville, vol. 6, pp. 1042–51; Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Contratación 396ª, no. 4, r. 7, f. 13.

Confronting such evidence, these authors speculated, and subsequent historians have affirmed, that ginger proved especially susceptible to contraband.Footnote 6 This was exacerbated by the impact of the Dutch Revolts (1568–1609, 1621–48) and the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604), when the onset of hostilities encouraged ginger to bypass official controls in Seville. Foreign merchants found themselves increasingly subject to the embargoes on shipping and seizures of their goods in 1585–90, 1595–96, 1598–1608, and 1621–48, which proved especially devastating for perishable commodities such as ginger.Footnote 7 Nevertheless, by the end of the sixteenth century, Indian ginger cost European consumers five times more than that grown in the Caribbean, according to Halikowski-Smith, and had therefore lost the price competition.Footnote 8

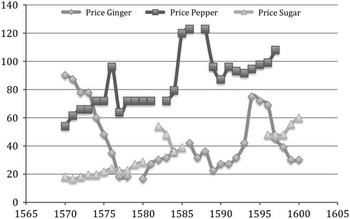

The price of ginger in Seville can also be compared to variations in the cost of the same commodity in Antwerp and London. For sixteenth-century Antwerp, the data published by Hermann van der Wee suggests that prices responded to Atlantic ginger in the 1570s, when they plummeted, even before records of shipments of ginger have been preserved in Seville. In comparison to the prices of sugar and pepper, those of ginger clearly reflect the impact of the entry of the product from São Tomé (an island in the Gulf of Guinea) in 1570, augmented by an influx of the same commodity from Hispaniola, as illustrated in Figure 3. This shows that the price of ginger plunged in the 1570s, just as the Dutch revolt against the Spanish monarchy got underway. Before records attest to ginger reaching Seville, the onset of the conflict coincided with a drop in the price of the spice in Antwerp. Had the embargoes on foreigners in Seville cut off the supply of ginger or led it to spoil, its price would have gone up. Moreover, a rough correlation of lower prices for ginger and higher prices for pepper in Antwerp suggests that ginger, while increasingly available, did not replace pepper, which remained exclusive.

Figure 3 Prices (in Brabant groots) of ginger, pepper, and sugar in Antwerp, 1570–1600. Absolute rather than relative (adjusted) prices serve the purpose of this comparison. Source: Hermann van der Wee, The growth of the Antwerp market and the European economy, The Hague: Nijhoff, 1963, pp. 307–29.

Thanks to the online Allen–Unger Global Commodity Prices Database, a comparison of the price of ginger in Seville, Antwerp, and London can also be attempted. Converting the different currencies and measures employed into equivalent units – namely grams of silver per litre (a measure of dry volume, not of weight) – reveals an unsurprising fact: the price of ginger in Antwerp soared above and sometimes even doubled that of Seville. On the one hand, this difference could have compensated planters who paid taxes on ginger redistributed through Seville to Antwerp, allowing various intermediaries a sufficient profit margin. On the other hand, it provided an additional incentive to direct trade between Hispaniola and the Low Countries. The biggest difference, however, and the biggest surprise, comes from the much higher price of ginger in London, well above that of either Seville or Antwerp (see Figure 4).

Figure 4 Price of ginger (g of silver/litre) in Seville, Antwerp, and London. Note that litres are a measure of dry volume, not of weight. Absolute rather than relative prices have been used for these comparisons. Years appearing on the x-axis are those for which prices are available. Sources: Chaunu and Chaunu, Seville; Allen–Unger Global Commodity Prices Database, http://www.gcpdb.info (consulted 26 June 2015), drawing upon van der Wee, Growth of the Antwerp market, and Gregory Clark, ‘The long march of history: farm wages, population, and economic growth, England 1209–1869’, Economic History Review, 60, 1, 2007, pp. 97–135.

The influx of Atlantic ginger, reflected in plummeting prices, reached London nearly one decade after Antwerp. Judging from these prices, moreover, the Anglo-Spanish War impeded the circulation of ginger no more than did the Dutch revolt, and probably even encouraged it. As in the case of Antwerp, the even greater value of ginger in London (which apparently offset taxes, spoilage, and the cost of various intermediaries involved in it passing through Seville, especially in peacetime) also provided an incentive to more direct trade, whether by barter or privateering – even if the corsairs initially and mainly sought bullion.Footnote 9 However incomplete, price registers indicate that a commodity whose production became important in the western Antilles was demanded in Antwerp and especially in London, whether or not it passed through Seville. They also indicate that war, rather than making perishable goods from the Spanish Caribbean less popular, catalysed the consumption of ginger in northern Europe.

The divergent demands of incipient European markets undermined the Spanish monarchy’s commercial control (and, evidently, its tax benefits) when products sought the most direct routes from producers to consumers, even – and perhaps, especially – in times of war. In Smuggling: contraband and corruption in world history, Alan Karras has called attention to the role of illicit trade as a means of negotiating the practical nature, implications, and limitations of state power.Footnote 10 Complementing the later case studies examined by Karras, the early seventeenth-century Antilles present a continuum between privateering, contraband, and other extra-legal activities with or without the threat of violence. Armed conflict, particularly the Anglo-Spanish War, encouraged rather than curtailed direct, illicit trade.

The following focus on ginger, produced in tropical regions yet consumed mainly in cold climates, highlights the role of inter-imperial collaboration, competition, and warfare in the spread of products.Footnote 11 It also reveals that commodities – rarely transported or consumed alone – complemented, concealed, and displaced one another, with ginger often hidden in American hides that were also demanded (for their size and quality) in Holland and England, and ginger farmers articulating demands for slave labour they needed to produce sugar. The rise and fall of Caribbean ginger production between 1580 and 1650 can be situated in the context of a global ginger diaspora, understood in terms of divergent European markets and connected to the spread of other commodities.

Why ginger?

Like sugar, a fellow traveller back and forth across the Atlantic, ginger had long been known to Europeans. In the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, as the Spanish began to explore the Caribbean, Portuguese merchants famously reached the fabled eastern sources of spices, including ginger. In a treatise on ‘The simples and drugs of India’ published in Goa in 1563, the Portuguese physician and naturalist Garcia de Orta listed the properties and uses of different products that he had studied. His twenty-sixth colloquy, on ginger, described it as well known and abundant throughout India, providing flavour in salads and for Catholics on ‘fish days’ (when they were supposed to abstain from meat). He reported the use of ginger against plague as well as against poison, and, particularly, as an aid to digestion, since, owing to its humidity, ginger heated more gradually than pepper. He had seen it preserved with sugar and, especially, covered with clay in order to increase its weight, maintain its humidity, and protect it from worms.Footnote 12 Orta nevertheless acknowledged the lack of an ideal solution for the crucial problem of preservation and transport, which would also arise for ginger grown in the West Indies.

According to the humoral framework for interpreting the world and the human body inherited from Galen,Footnote 13 northern Europeans needed ginger more than those who lived in the south. Within this framework, health entailed a balance between hot, dry, cold, and wet humours. Ginger’s simultaneously hot and moist nature made it an ideal sexual stimulant or a ‘common aphrodisiac’ – a taste of the tropics, potentially helpful for the cold yet harmful for the hot-blooded.Footnote 14

The Spanish literature mentions ginger without celebrating it. Sebastían de Covarrubias’ Tesoro de la lengua castellana (1611) simply recorded that ginger was ‘very hot’ and referred readers to the sixteenth-century Castilian translation of Dioscorides’ Materia medica by the Segovian-born physician Andrés de Laguna, who had practised in Italian and German states as well as the Low Countries.Footnote 15 Dioscorides/Laguna described ginger as having the same taste and properties as pepper, with its leaves used for ‘infinite things’ and added to soups and stews in Arabia.Footnote 16 Laguna’s contemporary in Seville, the doctor Nicolás Monardes, reported that ginger root enhanced salads’ ‘taste and smell’, was corrupted by humidity but preserved well in conserve, and was used as a ‘corrective and vehicle’ for many medicines.Footnote 17 A look at one medicine that Monardes mentioned, agárico, prescribed for everything from headaches to nerves to gout to muscular pain, clarifies matters. The only problem with this wonder drug was that it induced vomiting and could only be retained if combined with ginger and cloves.

While recording ginger’s medicinal and culinary consumption well into the seventeenth century, Spanish literature scarcely found it of interest. Cookery books printed in 1607 and 1623 simply listed it as one of many spices combined with cloves, saffron, pepper, and garlic, mainly to flavour meat and poultry.Footnote 18 The title of a manuscript attributed to a Madrid-born physician who settled in Mexico, Gregorio López, and copied in the seventeenth century, ‘Recetario o libro de medicina’, recalled the inextricable nature of medical and culinary uses, informed by a Galenic framework, with the word receta used for medical prescriptions as well as culinary recipes. López recorded ginger’s positive effects on the stomach and the eyes, as well as its ability to counteract poisonous bites, but with little fanfare.Footnote 19 In his manual, an increasingly familiar aphrodisiac such as ginger could hardly compete with substances as rare and exotic as unicorn horns or bezoar stones. Both of these objects, acquired and displayed whole, could also be grated as required for elite consumption.

In comparison with Spanish-language texts, early modern English literature had more to say about ginger. Gingerbread appeared in cookery books, the theatre, and even a songbook. The first known recipe for gingerbread, dating from c.1420, included pepper, powdered cinnamon, and sanders (powdered sandalwood), in order to obtain a reddish colour.Footnote 20 Manuals for elite housewives, while containing recipes for gingerbread, also instructed ladies in the use of ginger and sugar to prepare marmalade, such as that allegedly presented to Queen Mary as a New Year’s gift, as well as other varieties ‘very comfortable and restorative for any Lord or Lady whatsoever’.Footnote 21 Additionally, they indicated the use of ginger in recipes for medicinal waters or ‘aqua vitae’, including spiced wine that allegedly improved women’s complexions and the suggestively named ‘imperial water’, which ‘comforteth the vital spirits, and helpeth inward diseases that cometh of cold, as the palsy, the contraction of sinews, also it killeth worms, and comforts the stomach; it cureth the cold dropsy, helps the stone, the stinking breath, and maketh one seem young’.Footnote 22 Whether or not a consumer of ‘imperial water’, Elizabeth I has widely been credited with having ordered history’s first gingerbread men, fashioned in the likeness of her courtiers. The implications appear political as well as personal, honouring merchant-corsairs by circulating and consuming goods obtained from Spain’s ships and territories.

English literature also suggests that ginger retained aphrodisiac associations. A play about male desire performed before Elizabeth I on Christmas 1597 even mentions gingerbread as an antidote to cuckoldry. In this context, the humble clown in William Shakespeare’s Love’s labours lost informed an unfortunate friend: ‘had I but one penny in the world, thou shouldst have it to buy gingerbread’.Footnote 23 Playful references to the fruits of overseas ventures could popularize courtly fashions and broaden the English taste for ginger and its association with male virility.

In the seventeenth century, gingerbread recipes became more common and featured not only ginger but also sugar or honey, powdered cinnamon, cloves, saffron, liquorice, and aniseed in some cases; sanders, if a red colour were desired; and, optionally, pepper. While one recipe referred to ‘the powder of ginger’, another required ‘white ginger beaten and cerst [sieved]’, suggesting that ginger root may have been refined in the domestic kitchen.Footnote 24 A 1621 recipe directed the English gentlewomen to shape dough for ‘white gingerbread’ into a round cake and ‘print it with your moulds’, a technique that could have produced gingerbread men.Footnote 25 The sources consulted indicate that ginger was ground or pressed by apothecaries or cooks immediately before its use, and depict the sale and transport of ginger as a root rather than as a powder, presumably to preserve its properties.

From the court to the hearth, from privileged to more modest quarters, ginger treated timeless ailments. Incapable of withstanding low temperatures – ‘most impatient of the coldness’ – the plant resisted inclusion in the English garden.Footnote 26 It had to be obtained overseas and refined in the home. As overseas trade made the rhizome increasingly available, advice books and cookery books for English ladies taught them to employ it in the kitchen. In 1599, Henry Butts recommended the spice for comforting ‘cold stomachs’ and treating gases (‘winde’), while agreeing that it ‘sharpeneth the sight’ and ‘provoketh sluggish husbandes’.Footnote 27 Another manual, by William Vaughan, corroborated that the spice ‘sharpneth the sight, and prouoketh slothful husbands’.Footnote 28 Without overlooking ginger’s benefits for women, seventeenth-century manuals instructed British housewives to use ginger in order to motivate men.

The popularization of ginger in England and the languid male’s yearning for it are expressed in the lyrics of a song recorded in 1680:

A Poor Soul sate sighing near a Ginger-bread Stall,

Oh Ginger-bread, oh! Oh Ginger-bread, oh!

with his Hands in his Pockets, his Head on the Wall;

Oh Ginger-bread, oh! Oh Ginger-bread, oh!

You Pye-wives of Smithfield, what would you be at,

who talks of Plumb-pudding, here’s better than that;

for here’s Ginger-bread, oh! Oh Ginger-bread, oh!Footnote 29

To avoid such troubles, the English housewife could make gingerbread at home, thanks (in part) to privateers. Ingredients from overseas made the fruits of empire available in the home. In this way, English literature reflected and shaped a market for ginger.

The early modern English-language corpus, which discusses ginger and its potential benefits more frequently and more explicitly than printed Spanish texts, even mentions its production on Hispaniola. Richard Hakluyt’s translation of an account by René Goulaine de Laudonnière paid tribute to Spanish ‘improvement’ of the island:

The Spaniards at their first entrance into Hispaniola found neither sugar-canes nor ginger growing there, nor any kind of our cattle: ‘But finding the place fit for pasture they sent kine & bulls & sundry sorts of other profitable bestes thither, & transported the plants of sugar canes, & set the roots of ginger: the hides of which oxen, with sugar & ginger are now the chiefe marchandise of that land.’Footnote 30

Goulaine de Laudonnière and Hakluyt praised the Spanish initiative of successfully transplanting cattle, sugar, and ginger to Hispaniola. While the fruits of their efforts reached English consumers, privateers debated the possibility of transplanting ginger to English colonies (specifically Providence) in 1636, along with ‘indigo, cochineal, sarsaparilla, ginger, rice, any fruits, drugs or other useful commodities’, much as Spanish entrepreneurs had done in the 1540s.Footnote 31 For a number of years after 1643, significant quantities of ginger were exported from Barbados.Footnote 32 According to colonial documents in the UK National Archives, ginger as well as sugar grown on Barbados reached London in 1654, a year in which the French island of St Christopher produced ginger as well as tobacco, which were subsequently intercepted by English privateers.Footnote 33 Privateering did not, however, preclude efforts to emulate the Spanish strategy of transplanting ginger and other plants.

The Caribbean cradle

The production of ginger increased exponentially as it extended to new territories in the sixteenth century and then waned in the seventeenth, when a combination of factors made Caribbean sugar industries increasingly viable. Ginger and sugar production were incompatible and one expanded at the other’s expense owing to the fact that they required labour during the same months of the year (more intensively so in the case of sugar).

In the sixteenth century, the rulers of Castile encouraged attempts to smuggle pepper, cloves, cinnamon, and ginger out of territories encountered and claimed by the Portuguese, and to transplant them into Spanish dominions. Ginger seems to have been the only successful early modern case of the application of this strategy.Footnote 34 Although among the spices that had impelled Europeans down the coasts of Africa to India and to the Moluccas, it had played a secondary role to pepper, mace, and cloves. Its importance increased, however, in the sixteenth century, when it was transplanted and successfully cultivated on the islands of São Tomé, Hispaniola, and Puerto Rico, as well as in parts of Bahia (Brazil) and Mexico (then New Spain). The extension of ginger production to the Americas on the one hand entailed a deliberate, profit-minded, scientific endeavour, and on the other was a natural consequence of early globalization, as indicated by parallel paths for the rhizome’s extension to different regions.Footnote 35 In the words of a seventeenth-century observer: ‘Of all the Spices of the Levant that have been planted in America, only Ginger hath thriv’d, and come to perfection.’Footnote 36

Self-proclaimed heroes and aspiring beneficiaries of American ginger production included a future governor of the Philippines, Guido de Lavezaris, the heir of the Viceroy of Mexico and Peru, Antonio de Mendoza, and a Dominican planter, Rodrigo Peláez. The better-known contributions of Lavezaris and Mendoza have been recorded by sixteenth-century authors, including Nicolás Monardes, and noted by the historian Serge Gruzinski.Footnote 37 Lavezaris, who served as Spanish governor of the Philippines from 1572 to 1575, was credited with surreptitiously smuggling ginger from the Moluccas to Castile and then to New Spain, where he allegedly planted it in a garden in Quauhnahuac, during the viceroyalty of Antonio de Mendoza in the 1540s.Footnote 38 After the death of the viceroy, his son and heir, Francisco de Mendoza, extracted remarkable concessions from the crown of Castile to transplant and cultivate ‘oriental’ spices, including ginger, in Mexico. These royal concessions, signed in Valladolid on 5 November 1558, gave Mendoza exclusive rights to transport, transplant, cultivate, and export spices for one-third of the profits anticipated from pepper, cloves, and cinnamon and half of the projected benefits derived from ginger, ‘china’ (a root useful to treat syphilis or melancholy, according to MonardesFootnote 39) and sandalwood (used for perfume and incense yet almost impossible to cultivateFootnote 40) that might be grown in the Americas, with rights to the lands necessary for planting the crops as well as for maintaining the livestock needed for the enterprise (los ganados de labor y trato).Footnote 41

The Council of the Indies objected to the terms offered Mendoza, particularly provisions according him rights to use common lands and indigenous labour. It described, moreover, the prohibition of others cultivating and trading the same goods as ‘intolerable’, noting that pepper, cinnamon, and cloves could not be grown in New Spain or the West Indies for that matter, whereas ginger was already planted and thriving there.Footnote 42 In spite of these objections, Philip II confirmed the concessions to Mendoza in Brussels on 31 March 1559.Footnote 43 In any case, they had no more effect than similar provisions granted to another entrepreneur in 1538 to cultivate pepper, cloves, cinnamon, ginger, nutmeg/mace, and other spices in the West Indies.Footnote 44 Ginger cultivation spread and other spices refused to take root, regardless of the Spanish monarch’s incentives to promote them.

In comparison to Mexico, which ultimately produced little ginger, the root’s simultaneous diffusion from São Tomé to Bahia on the one hand (noted by Russell Wood), and to Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, and Cuba, on the other, has received less attention.Footnote 45 Details for the case of ginger on Hispaniola appear in a relation of ‘merits and services’ compiled for the Council of Indies and the crown by Rodrigo Peláez, who portrayed himself as an enterprising member of the island’s elite, one of its ‘most pacific and best-dressed men’ (de los mas pacíficos e mejor traje) in 1577.Footnote 46 According to Peláez and the witnesses he presented, some thirteen years earlier he received about 3 ounces of green ginger from São Tomé in the Gulf of Guinea.Footnote 47 Peláez, who served as secretary in the Royal Tribunal (Audiencia), recorded that he had planted pieces of the ginger root in his garden, probably instructed and assisted by West Africans carried on the same ship, until he accumulated enough to plant in the fields. Making use of a genre designed to seek rewards from the crown, the planter alleged that he had incurred great expenses and hardships, ‘doing many experiments over the course of eight years until I could achieve the form and order required and necessary to cultivate it, occupying my people and slaves with very great costs and losses … and being very careful to make records (memorias e relaciones) of how it should be planted, and harvested and prepared’.Footnote 48 If not the first planter to grow ginger on Hispaniola, Peláez had been the most persistent.Footnote 49 His testimony and that of his witnesses, including the Archbishop of Santo Domingo and the former president of the Royal Tribunal, recorded the seasonal nature of production of the island’s ginger, which was planted at the end of May, harvested from mid January onwards, and dried by April or May.

Unlike Francisco de Mendoza, who had planned to employ indigenous labourers, Peláez requested tax exemptions for fifty years and licences to convey 500 slaves of African origin to Hispaniola, which the crown refused him, probably reserving such concessions for its financiers. He owned eighty slaves in 1577 and declared that he had ‘rented’ additional slaves and free labourers the same year in order to produce some 2,500 arrobas (28,750 kg or 62,500 pounds) of ginger. According to other planters, more slaves would also increase the island’s production of manioc, bananas, and corn from June to December, when they were not occupied with the ginger.Footnote 50 While hardly surprising, the demand for slaves clashes with an emphasis in the literature on ginger as a crop requiring little investment and suitable for humble people without livestock or mills, especially in comparison to sugar, which required very intensive labour to harvest and refine it from January to May.Footnote 51 Ginger’s lower labour intensity lay behind the temporary success of its farming in the late sixteenth-century Caribbean. As planters there discovered and reported, ginger roots harvested in February or March could be preserved in sugar or ‘dried’ in the open air for several months in order to prevent rotting, then wrapped in hides for the Atlantic crossing. Yet ginger planters demanded slaves, who were required in greater numbers not necessarily to produce ginger but certainly to extend sugar production. The Spanish crown’s reluctance to issue slave licences left room for Dutch, English, and French interlopers with access to slaves from West Africa to develop their own interests and markets in the Antilles, trading in slaves as well as ginger, sugar, and hides.Footnote 52

Another remarkable feature of the testimony provided by the witnesses for Peláez consists in their apparent security about northern Europeans’ demands. Planters and officials unanimously declared that ginger was among the most popular and valuable spices in England, France, Germany, the Low Countries, Muscovy, and other ‘foreign lands and cold regions’. The doctor Juan Pérez, for example, had heard it said that ginger ‘was almost an ordinary staple in those provinces’, yet curiously, given his profession, refrained from any medical observation. On the other hand, a planter lobbying for slave licences, declared ginger ‘very healthy’ (muy medicinal). In contrast to such testimony, merchants based in Lisbon wrote of ginger from São Tomé as a ‘new drug’ that reached them in January 1575 and expressed concern about the potential impact of uprisings against the Spanish monarchy on its sale in Antwerp.Footnote 53

In December 1584, a merchant in Seville, Francisco Morovelli, advised Simón Ruíz, his well-known partner in Medina del Campo in central Spain that a large quantity of ginger had reached Seville from Santo Domingo, and that ‘Flemings and others’ had purchased most of it. Morovelli asked whether or not he should acquire some 400 quintals of the remaining ginger for re-export to London, Antwerp, and Holland, as another partner had requested.Footnote 54 Although letters were sent from Seville to Medina del Campo and back to Seville, there appeared no suggestion or possibility of selling American ginger in Medina del Campo or Madrid. These merchants, like their counterparts in Santo Domingo, had no doubt that the market for the spice lay in northern Europe. Of course, ginger also had uses in early modern Castile: the root had been and would continue to be employed in medicines and in cooking. It also appeared with other ‘Asian’ spices as an ingredient in chocolate recipes, which spread through courtly circles and subsequently among ecclesiastics and other elites in the seventeenth century.Footnote 55

Yet no one seemed to think that much ginger could be sold in Spain. Even the Spanish monarchy’s policies attempted to facilitate the exportation of ginger to northern Europe, within the framework of an easily eluded, revenue-generating mercantilist system. In the seventeenth century, the Dutch, French, and English sought their own islands in the Caribbean, and also continued receiving ginger from Hispaniola and Puerto Rico. The French and English even managed to cultivate the spice, if rather ephemerally, on St Christopher and Barbados, further undermining the revenues of the crown of Castile and the interests of merchants based in Seville.

Royal policies and the futility of monopoly

The eclipse of Caribbean ginger in the seventeenth century reflected more of a lack than an excess of Spanish imperial control. Some confusion stems from the use of ‘monopoly’ to refer to government control over the production and sale of specific products, as well as the early mercantilist idea of a ‘Seville monopoly’ theoretically designed to control and tax commerce between Europe and the New World. Regarding ginger, the literature has noted that the king of Spain initially encouraged its cultivation but subsequently prohibited Puerto Rican sugar-planters from growing ginger, to no effect.Footnote 56 While some authors have attributed the industry’s success in the late sixteenth century to a royal monopoly, the crown actually appears to have received petitions to establish one without acting upon them.Footnote 57 Far from enforcing monopolistic regulations or even the privileges of Seville, the crown made concessions to facilitate the circulation of American products. These measures were nevertheless undermined by defensive and fiscal needs.

The impact of royal intervention, like that of royal inaction, can be overestimated. With respect to ginger, the Spanish crown acted mainly in response to petitions from Hispaniola, guided by economic interest and, ultimately, defensive concerns. A Spanish ginger monopoly never existed, and would have been impractical for three reasons: the presence of English, French, and Dutch interlopers in the region, who left no doubt about the demand for ginger and hides in northern Europe; the timing of the annual fleet system that Philip II instituted for protection against corsairs; and the perishable nature of a product that lacked an important market in Castile.

Aware of the foreign menace in the Caribbean, Philip II had encouraged the cultivation of ginger on Hispaniola with the goal of transplanting it to Castile.Footnote 58 In 1574 he requested a sample of the island’s very best ginger, as well as an account of the steps followed in its production, explicitly for the purpose of attempting to cultivate it in Castile.Footnote 59 When confronted with evidence of trade with foreigners on the northern coast of Hispaniola, in an interesting precedent for measures decreed along the Spanish coasts after 1596, the king declared the need to relocate the offending population to the island’s interior and asked local officials for their views on the matter.Footnote 60 Yet the officials themselves, often benefitting from the illicit trade, impeded efforts to curtail it.Footnote 61

The crown’s consultations with Spanish officials in the Caribbean indicate that ginger had displaced sugar and become the leading export crop on both Hispaniola and Puerto Rico by the end of the sixteenth century. Although alleging other motives, Hispaniola’s original and unsuccessful pleas for a ginger monopoly in 1584 and 1588 appear to have been intended to curtail competition from Puerto Rico, which gained fame for producing the best rhizomes.Footnote 62 Requests for a ginger monopoly for Hispaniola continued, adding new arguments to those originally proposed: in addition to ‘saving’ the island and increasing royal revenues, proponents of the ginger monopoly argued that a ‘single buyer’ could limit the quantity of ginger available in order to keep prices high and stable.Footnote 63 In 1599, the royal accountant on Hispaniola, Diego de Ibarra, recommended that Philip III limit the cultivation of ginger to that island, where it had become the main export (principal granjería), in order to restrict the supply of ginger that reached Seville and Flanders and thereby to keep the price from falling.Footnote 64 In fact, the data indicate a more significant drop in the price of ginger in Antwerp and London from 1594 to 1599 than in Seville, where records registered no fall in its price (see Figure 4).

Yet the Spanish monarchy proved more concerned about defence than prices. The threat of corsairs led to Castile’s increased reliance on a convoy system ill-suited to Hispaniola and especially to ginger. While royal officials at Santo Domingo accepted the fleet system, other settlers on Hispaniola did not.Footnote 65 Caribbean ginger, they explained again and again, was harvested, dried, and prepared for shipping from late January to early June. More precisely, planters explained that ginger root should be unearthed during the waning of the moon after the leaves of its plant had fallen, which might take place in January or even as late as March.Footnote 66 The annual fleet’s departure in March or the first half of April forced planters to load green ginger, much of which spoiled. In 1581 Rodrigo Peláez and his associates requested permission to send one or two ships of up to 400 tons laden with ginger and hides from Santo Domingo to Cádiz in May or June each year.Footnote 67 Instead of enforcing the monopoly associated with the fleet system, after a lengthy process of consultation, including the Royal Council of the Indies, the House of Trade, and the merchant’s guild of Seville, Philip II resolved to allow two ships laden with ginger, hides, and ‘other fruits of the land’ to sail on their own, heavily armed, from Santo Domingo to Seville. Only the outbreak of war with England kept ships from receiving this authorization.Footnote 68

War with the English and the Dutch gave traders and privateers an excuse, if they had ever needed one, to send ginger and hides directly to their markets without passing through Seville. As a further incentive to direct transport from the Caribbean to northern Europe, foreign merchants in Seville were subject to the confiscation of their property and records during wartime. Seizures of foreign goods have been documented in 1574, 1585, 1587, 1595, 1596, 1598, 1601, and 1602, in addition to the effects of more general embargoes in 1598 and 1601.Footnote 69 Although some of the property impounded was ultimately returned, such measures would have curtailed the already limited possibilities for the timely re-export of perishable commodities such as ginger.

Far from enforcing a monopoly, the Spanish monarchy could barely cope with privateers. English pirates commonly seized cargoes including ginger and hides.Footnote 70 Reporting on Hispaniola’s situation in late 1595, Antonio de Zamora Carreño, the master of the ship Our Lady of the Incarnation, depicted the corsairs’ continual activity on the island, whether sacking sugar mills or selling the island’s residents cloth at unbeatable prices.Footnote 71 Another privateer, the Count of Cumberland, occupied Puerto Rico in September 1598, and English ships entered Hispaniola’s Puerto de Plata, seizing 100 men, artillery, and two ships loaded with hides and probably ginger, on 7 March 1600.Footnote 72 These attacks sent shock waves throughout the Spanish empire, while despatching hides, ginger, and other commodities directly to London.Footnote 73 Visiting Puerto Rico and Hispaniola at the end of the sixteenth century, Samuel Champlain recorded evidence of the thriving contraband trade in slaves, ginger, and sugar.Footnote 74

In 1595 the Governor of Santo Domingo labelled corsairs an authentic plague that preyed upon all of the ships that dared to call at that port.Footnote 75 In February 1601, the Duke of Medina Sidonia advised the Spanish king and royal council that a captain had reached San Lúcar from Santo Domingo with troubling news: he reported eleven Flemish ships at Hispaniola, ‘trading with the locals as securely as if in their own land, and even dispersed in the [island’s] rivers, awaiting their cargoes of hides and ginger’.Footnote 76 Through piracy and contraband, the trade in Caribbean ginger packaged in hides eluded the Spanish monarch’s control. In 1604, the Governor of Havana, Don Pedro de Valdés, informed the king of four French and Dutch ships trading along the coast of his island, ‘with as much publicity and security as if they were in their own ports’. In the governor’s estimation, the merchants were ‘great heretics’ intent upon disseminating their goods and their faith.Footnote 77

Defensive concerns, justified and heightened by religious fears, led the crown of Castile to adopt decisive yet counter-productive measures in an attempt to crush contraband. Trade with foreign merchant-corsairs along the northern coast of Hispaniola prospered during wartime, according to a 1598 memorial. Specifically, its author blamed commerce with ‘Lutheran’ pirates (meaning Protestants in general) for a lack of beef on the island, which it had once sustained.Footnote 78 In 1605 Philip III ordered Antonio Osorio, who had been the royal governor of Cadiz during its siege by the Dutch and English in 1596, to apply the measure that Philip II had considered for Hispaniola as early as 1573. Osorio’s forcible relocation of cattle and ginger farmers from the northern coast of Hispaniola has become known as the ‘devastations’ of 1605. Yet the measures, while often decried, stopped neither contraband nor ginger production.

The evidence points to a continuation of ginger cultivation after the ‘devastations’. The supply of the spice continued to increase and its price continued to drop, at least in Seville. In 1611, Seville’s House of Trade requested that fines no longer be paid in ginger, and, in 1613, apparently faced with a glut on the market after peace had been established with the United Provinces, reiterated that no more ginger should be sent to Spain.Footnote 79 At the request of the Royal Tribunal in 1629, however, the king sent special ships to Santo Domingo to load 30,000 quintals of ginger, 40,000 hides, sugar, and other merchandise, while simultaneously prohibiting royal judges on the island from trading in the same commodities.Footnote 80 Rather than requesting their opinion, the king reminded the officials that they received salaries and should not benefit from tax exemptions and trading privileges as well.Footnote 81 Given the glut in Spain, the continuation and even increase in ginger production can only be explained by demand for it in northern Europe.

Perhaps inevitably, foreign merchant-corsairs accommodated ginger better than did the Spanish fleet system. In addition to the danger of loading ginger before it had been dried, the spice’s perishable nature made bypassing Seville and Cadiz desirable to prevent spoilage. Disputes over ginger preserved in the General Archive of the Indies reinforce its image as highly perishable and easily hidden. One shipmaster, accused of concealing and selling the spice in 1597, insisted that he had hastened to sell the ginger in his cargo to a Flemish merchant in Seville, Juan de Landaverde, before it rotted.Footnote 82 Ginger’s perishable nature encouraged its expedient commercialization and, therefore, direct transportation to consumers. For this reason and because it was poorly adapted to the fleet system, the spice made ready contraband. The availability of hides in the Caribbean and demand for them in England and the Low Countries, as well as their ability to contain and conceal products such as ginger, further facilitated extra-legal exchange. The question, then, becomes how much ginger the hides could have hidden and for how long.

Paradoxically, the Spanish monarchy’s need to fortify its Caribbean defences made it even less viable for planters on Hispaniola and Puerto Rico to send the ginger that their ‘Lutheran’ neighbours wanted to Seville. In 1638 Luis Alemán, a merchant residing in Seville, recommended that the crown of Castile charge 2 ducats for every quintal of ginger re-exported, alleging that the measure would generate 4,000 ducats annually for the royal fisc. The crown – hoping to use the measure to pay for construction of the fortress of Saint Lawrence at Portobelo (one terminus of the Spanish fleet system) – requested advice from Seville’s House of Trade, as well as from Santo Domingo’s city council. The House of Trade provided figures about the quantity of ginger shipped from the Antilles to Seville in 1633, 1634, and 1635, two-thirds of which (11,381 out of 18,128 quintals) had been recorded as subsequently re-exported, mainly to Zeeland and Holland, ‘where it is needed, since the land is very cold’.Footnote 83 Given the rhizome’s perishable nature, however, the officials in Seville advised against applying the taxes, which could hurt sales. More emphatically, the council of Santo Domingo declared that additional taxes would entail ‘the complete ruin and destruction of the island as well as that of Puerto Rico due to the excessive impositions, and that, for the same reason, foreigners will no longer export ginger but seek it, rather, in Brazil, where the Dutch have it in abundance’.Footnote 84 The boom in Caribbean ginger was nearing its end, with the rise of competition from Bahia alongside a mounting demand for sugar in Europe and a growing supply of African slaves to produce it, which made sugar an increasingly viable and more profitable commodity than ginger for Caribbean planters. In this sense, the increased activity of European slavers and growing numbers of African slaves in the Antilles also facilitated a transition from ginger to sugar, which required more intensive labour. According to all reports, the production of Caribbean ginger had declined by the mid 1600s.Footnote 85

Although the influence of Galenic medicine also waned, the ginger root retained its aphrodisiac associations. At the end of the eighteenth century, the Abbé Raynal wrote a treatise on spices and colonial products that adjusted ginger’s history to elide inter-imperial smuggling. Raynal claimed that ginger was native to the Antilles, where Spaniards encountered it and began a ginger craze. According to the abbot, Spaniards in the Caribbean became impassioned by the spice – eating it in the morning to enhance their appetite, at the table in many different confections, and after meals to ease digestion. Beyond a Galenic humoral framework, Raynal noted that ginger could be used as an antidote to scurvy during sea voyages and had ‘commonly’ been combined ‘everywhere’ with pepper, when pepper was still very expensive; as the price of pepper lowered bit by bit, ginger had gone out of style. Passing in his writing from Jamaica to Malabar, Raynal claimed that ginger nevertheless remained popular in Asia, where native women allegedly left their European partners no choice but to consume it, since, ‘there, as here, it is easier for men to adopt the taste of women than to remedy it’.Footnote 86

Yet more than taste appears to have been involved in giving men ginger, which had also reached West Africa in the sixteenth century.Footnote 87 An early twentieth-century study of French colonial products recorded that women among the Wolofs and Fulanis in Senegal and Futa-Jalon, where ginger was consumed in couscous, also made belts from the root, allegedly in order to restore the vigour of their aged spouses.Footnote 88 Even without the humoral framework, which justified an increased reliance upon ‘hot’ substances in cool regions, ginger continued to interest European authors as a dietary and sexual stimulant. In this context, however, it never became popular in Spain.

Unlike hides and sugar, which were demanded throughout Europe, ginger had more specific markets. Considering the spice’s consumption as well as its production and transportation underlines the very incomplete nature of the registers in Seville. The American rhizome, although initially transported in barrels (pipas), apparently weathered the journey better wrapped in hides, which were also used for tobacco, indigo, and cacao, facilitating intra- and inter-imperial trade in a variety of genres.Footnote 89 Although contraband by definition went unregistered, the authorities occasionally intercepted and recorded ginger, usually in hides. In 1588, the House of Trade seized some 500 quintals of undeclared ginger before the royal judges ordered them restored to the shipmaster, Juan de la Parra, along with 600 hides.Footnote 90 On other occasions, when hides alone are recorded, ginger and other commodities may have been carried and concealed within them. In 1619, the frigate Nuestra Señora del Socorro, allegedly intimidated by corsairs on its way from Puerto Rico to Seville, took refuge in Pontevedra, where the king asked his general overseer of the Portuguese troops to secure its cargo. The cargo, hastily and haphazardly disembarked in a storm, included some 2800 quintals of ginger, ‘contained in 500 hides or a bit more’ (cosa de 500 cueros poco más) and 46 boxes of sugar. While such items appeared destined for commercial purposes, others, such as two to three little bottles of ginger in conserve, were described as being intended ‘to present’, probably to the authorities.Footnote 91 Bits of pickled or candied ginger appear to have been designed for strategic gifts so that greater quantities of ginger root could remain concealed.

The fact that much ginger, hidden in hides or otherwise, went unregistered cautions against reliance on the amounts of these products recorded in Seville from year to year. Complementing without completing such registers, the Calendar of State Papers for England records the seizure of one ship laden with ginger and hides in 1597 and four such ‘prizes’ in 1602.Footnote 92 However, the prices of ginger and hides registered may be somewhat more reliable and revelatory of the development of the commercial channels described above.

Conclusions

Fortunately for the Spanish monarchy, it never tried to establish or enforce a monopoly on the production, transport, or consumption of ginger. Any attempt to do so would have been a losing battle because cultivation of the spice became too successful in too many areas. Rather than adhering to a rigid monopoly system, the Spanish monarchy made considerable, if often counter-productive, concessions to facilitate the spread of ginger. Nevertheless, an increased availability of slave labour in the Caribbean and Brazil as the seventeenth century advanced allowed sugar to reclaim plantations previously lost to ginger. Asian ginger may also have made a comeback after the 1650s. Posthumus records ‘preserved Chinese ginger’ in Amsterdam from 1625 onwards, explicitly delivered by the Dutch East India Company from 1654, and joined by ‘dry ginger’ after 1666.Footnote 93

Just as new sources of hides emerged from beyond the Caribbean and Atlantic frameworks, Asian ginger continued to reach Europe and to capture shares of markets that Caribbean ginger had expanded. Posthumus records the sale of ‘white scraped (dry) ginger’ (witte geschraapte (droge) gember) in Amsterdam from 1750 to 1847. The records he cites could refer to powdered or ground ginger as early as 1666, and certainly appear to do so after 1750. A new technology of drying or scraping ginger may have been introduced to ameliorate the problems identified in its transportation and preservation. Any such innovation would have reduced the incentives for direct trade in ginger from the Caribbean, where sugar and tobacco had become the leading export crops.

Whether pickled in sugar, packed in clay, wrapped in hides, or dried and scraped, ginger (like pepper for the Dutch or, perhaps, cacao for the Spanish), seasoned emerging imperial identities. The English made a profit and a virtue out of cargoes from the ‘Spanish Caribbean’, especially when they managed to evade taxation. Contrabandists and privateers ensured that Caribbean ginger reached consumers in northern Europe, as reflected in the falling prices of the commodity in London from 1581 to 1633, which nevertheless remained well above those charged in Seville. A continuum of forms of illicit commerce, from privateering to smuggling, facilitated a growing northern European presence in the Antilles and fostered a taste for the region’s products in England and Holland.

Inter-imperial relations, especially the onset of hostilities, enabled products to be transported by more direct routes to their consumers. In retrospect, given the factors involved, the Spanish king’s willingness to adjust the law and Hispaniola planters’ attempts to comply with it appear more surprising than the prevalence of unregistered trade. The issues involved in ginger production, transport, and consumption, alongside the availability of hides for transport from Hispaniola, appear to have made bypassing Seville a foregone conclusion. Moreover, the profits derived from privateering as well as contraband encouraged and reinforced English, Dutch, and French interests in the Antilles. Thus the boom and recession of Caribbean ginger emerges from and informs the entangled histories of different empires, while illuminating those of connected commodities including sugar, hides, and slaves.

Bethany Aram is a Ramón y Cajal research scholar at the Universidad Pablo de Olavide, and the principal investigator of ‘An ARTery of EMPIRE: conquest, commerce, crisis, culture and the Panamanian Junction (1513–1671)’.