Introduction

Method of Levels (MOL; Powers, Reference Powers and Powers1972; Carey, Reference Carey2006) is a therapeutic technique based on a theory called Perceptual Control Theory (PCT; Powers et al. Reference Powers, Clark and McFarland1960; Powers, Reference Powers1973, Reference Powers2005). In line with the way that cognitive therapies are developing as a family of related approaches (Mansell, Reference Mansell, House and Loewenthal2008), MOL identifies itself as a form of cognitive therapy, yet has a theoretical grounding that makes it distinct. This article will cover a range of advantages and disadvantages of building MOL into current clinical practice, both from the perspective of the underlying theory and the therapy itself.

PCT

PCT is a theory that was developed in the 1950s and 1960s to explain human behaviour. William T. Powers, who developed the theory, is a medical physicist and engineer, rather than a psychologist or health professional. He utilized a knowledge of engineering, mathematics and biology to explain his observations of behaviour, rather than basing it on any pre-existing theory or evidence base. PCT can be separated into its core principle, and its detailed architecture. The core principle is essentially fixed, whereas the architecture is essentially a detailed ‘work in progress’, and potentially open to reasoned modification. The core principle can be summed in one phrase: ‘behaviour is the control of perception’. PCT proposes that living things, including humans, control their input, whereas their output is merely a means to an end and modifiable across contexts. While this premise can be traced back to William James's (Reference James1890) early conceptualization of the essence of ‘mentality’, and is implicit in certain other accounts, it is the essence of PCT.

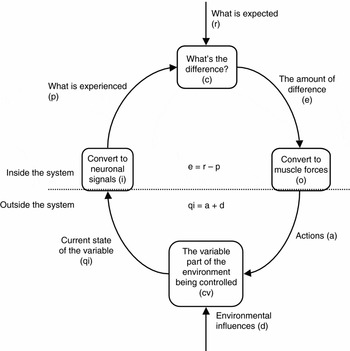

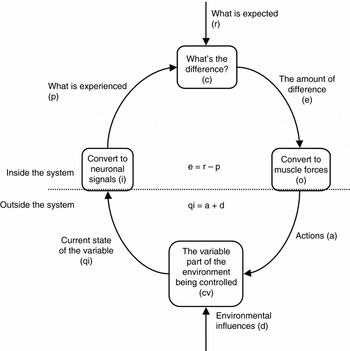

Following on from the basic premise, the theory specifies the mechanism through which control of input can be achieved, i.e. the negative feedback loop (see Fig. 1). Within this system, a comparator system computes the discrepancy between incoming perception and a reference value or standard. The discrepancy, or error, is proportional to the degree output of the system that acts on the environment, in the face of disturbances, to maintain input around the reference state. As an example, a child who has a reference of a certain level of proximity to his/her parent when distressed would cry more when the parent moves further away, and less when the parent moves nearer, to try to maintain the parent at the reference distance. This example is not coincidental – attachment theory is based on an early control systems approach (Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1969).

Fig. 1. The negative feedback loop is a fundamental component of Perceptual Control Theory. Figure reproduced with permission from Timothy A. Carey.

The richness of PCT comes into play when further questions are asked. How are complex perceptions controlled? How does learning occur? Where do these reference values come from? The full theory explains these processes in detail (Powers, Reference Powers1973, Reference Powers2005). In essence, the theory proposes that what is seen as complex, coordinated behaviour is the action of multiple, hierarchically organized negative feedback loops that form during development to organize ascending perceptions from intensity, sensations and configurations, through sequences and programmes of action, up to overarching principles and systems, such as the ‘self’.

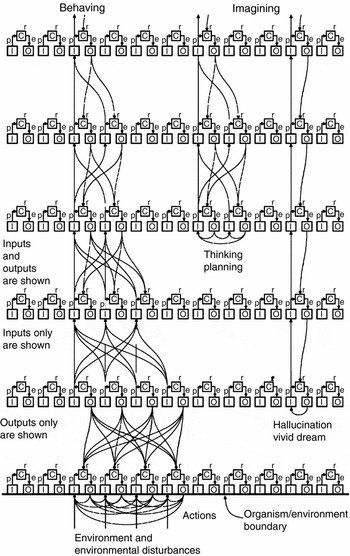

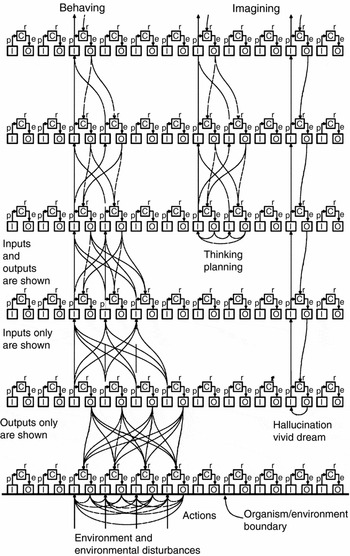

A control system hierarchy is displayed in Fig. 2. Higher-order systems send output signals to the next level in the hierarchy which provide their reference levels for control – thus, higher systems control their perception, not observable behaviour. In other words, PCT understands people as goal-directed agents all the way down from their personal higher-order goals to the ideal intensities of their sensory receptors; behaviour only has a role in controlling perception at the interface between these visceral lowest-order goals and the physical environment. There is no unchecked ‘behavioural output’ that is ‘triggered’; all behaviour is action-guided at maintaining perception within certain parameters.

Fig. 2. A hierarchy of control systems and the modes in which they can function according to Perceptual Control Theory. [Reproduced with permission from People as Living Things by Philip Runkel (www.livingcontrolsystems.com).] Figure reproduced with permission from Timothy A. Carey.

A concrete example of hierarchical organization follows. A control system to maintain a perception of ‘safety’ at a high level would send out signals to lower-order systems involved in perceiving safety within various contexts – for example perceiving oneself as far away from the edge of a tall building, and perceiving oneself as ‘competent’ during a meeting with one's line manager. Each of these systems achieves its ends through the signals it sends to lower systems. For example the system trying to maintain a sense of ‘competence’ might set references for ‘upright body posture while walking’ or the perception of how intelligent one's comments are. In turn each of these systems achieves its ends through its own subsystems – for example the outputs of the body posture system would form the references for specific configurations of the person's limbs. These systems in turn would need to maintain their configuration in the face of environmental disturbances – such as when walking down stairs. At each stage, no behaviours are specified at the higher levels – only the perceptual references; it is the multitude of control systems involved in muscle forces at the lowest level of the hierarchy that act on the world to try to ensure that their references (which are determined from the signals from the levels above) are reached in an ongoing fashion.

Figure 2 illustrates one key advantage of this hierarchical organization – higher levels can cycle round independently from the systems controlling immediate action so that goals can be manipulated within imagination and implemented on later occasions. This mode is particularly important during therapy where the therapist and client explore the client's control of perception within their ‘mind's eye’.

The negative feedback loops at succeeding levels of the hierarchies are connected by different ‘weightings’, and it is these weightings (among other properties) that change during learning in a trial-and-error fashion, in order to reduce the amount of error in the system. This process is called reorganization, and is required when there is conflict in the system – essentially when two systems are striving to control the same perceptual variable at different values. For example, a person who wants to ‘earn lots of money’ through the subgoal of ‘working 7 days a week’ would experience conflict when a system for ‘maintaining a pleasurable life’ entails the subgoal of ‘working 6 days a week or less’. As can be seen from this simplified example, the zone where conflict is manifested is often at low levels, such as the programmes of action involved in ‘working’ in this example. However, to properly understand the source of the conflict it is important to go ‘up levels’, in this example to the perceptions of ‘earn lots of money’ and a ‘pleasurable life’, and beyond here to the system that is setting these incompatible standards. In this example, the client could be setting both standards in order to achieve the higher-level perception of ‘feeling like a worthwhile person’. The process of MOL will be described later, but its goal is to reach the highest levels, because it is the higher levels that set the subgoals for the lower-order systems that are in conflict. Thus, in this example one would expect the client to reorganize his/her goals of financial success versus a pleasurable life in a way that reduces the conflict (e.g. he may prioritize one goal over the other; he may find a way to combine both; he may introduce other subgoals that make him feel worthwhile).

Five cons of PCT

Hopefully the explanatory power of PCT is now self-evident. However, realistically, there are several reasons why a CBT therapist would not want to adopt a PCT approach:

(1) PCT is little known. At least at present, PCT is little known among CBT clinicians and researchers, and within psychology and psychotherapy as a whole. With the recent advent of so many ‘third-wave’ theories and therapies within CBT, why find out about yet another one? It would be easy to let PCT drop below the radar just to manage the influx of new ideas that seem to be introduced into CBT.

(2) PCT is an old theory. Related to the above point is the fact that PCT is a relatively ‘old’ theory. How could an approach that was first published in 1960 still not have achieved recognition or acceptance? Again, that seems like a good reason for ignoring the approach, because surely if it was an effective theory for psychological therapy, then people would have adopted it decades ago? Three further concerns about PCT may help explain its relative obscurity over time.

(3) PCT has been developed by an engineer. Bill Powers is an engineer by trade, not a psychologist. Not only does this raise concerns as to whether an engineer would be qualified to develop a theory of human behaviour, but it also leads to further complications. Powers was not bound by the custom to review, critique and integrate existing psychological theory and use their terms; instead he adopted terms from engineering to try to explain what he observed in human behaviour.

(4) PCT implies that existing theories are inaccurate. The theory does not use psychological terms such as ‘conditioning’, ‘beliefs’ and ‘personality’, as they are difficult to define and may have imprecise meanings in mechanistic control terms. While there is a clear rationale for such a pure approach, its disconnection from the existing psychological literature can make the approach seem deliberately isolationist, reactionary, and even arrogant. It would be difficult to expect any theory to be readily adopted by academics, practitioners and the general public if it implied that the multiple existing theories within a discipline are inaccurate or incomplete.

(5) PCT takes a mechanistic view of the person. The theory aims to provide the principles for a mental architecture that can be modelled mathematically. The idea that a person could be reduced to this level of explanation is particularly challenging. Many people, even scientists and therapists, would feel that some features of the human mind are too complex and therefore beyond explanation, such as consciousness, spirituality and self-identity. The idea that these mental processes might be modelled also raises fears that humans can create machines with their own selfish goals – a dreaded vision often capitalized upon by literature and Hollywood movies.

Five pros of PCT

Taking together the above concerns about PCT would make any CBT therapist hesitant. Nevertheless, to some degree these concerns are addressed by five important qualities of the theory:

(1) PCT explains how ‘control’ works. The concept of ‘control’ pervades psychological theory (Carey, Reference Carey2008). Moreover, within CBT there is particular importance placed on the control of emotions, thoughts and behaviour. To take one example, beliefs about the need to control thoughts and beliefs about the perceived uncontrollability of thoughts form the two subscales of the Thought Control Questionnaire that correlate highest with measures of worry, obsessive–compulsive symptoms, and trait anxiety (Wells & Cartwright-Hatton, Reference Wells and Cartwright-Hatton2004). The importance of interpersonal control in cognitive therapy is also critical. The collaborative relationship reflects a balance of power where neither the therapist nor client is ‘in control’ of the session. How can this arrangement that seems to facilitate cognitive therapy be explained? Finally, and importantly, a range of studies support the role of loss of control during stress and trauma, and the process of regaining perceived control associated with recovery (e.g. Frazier, Reference Frazier2003; Compton et al. Reference Compton, Robinson, Ode, Quandt, Fineman and Carp2008; Higginson & Mansell, Reference Higginson and Mansell2008). Taken together, a theory that explains how people exert control and manage to regulate what matters to them clearly provides an important contribution to the explanation of how CBT has its effects.

(2) PCT takes a first-person, phenomenological perspective. Cognitive therapy is based around the conscious experience of the client. Beck (Reference Beck1976) first contrasted cognitive therapy with psychoanalysis which emphasizes the therapist's interpretations of the client's unconscious motivations, with early behaviour therapy which takes the measurement of observable behaviour as the only source of valid data, and with neuropsychiatry which locates the source of the client's problems within a disordered neurochemical process. According to Beck (Reference Beck1976), all three approaches ignore the validity of the client's own reports whereas in cognitive therapy, the client's own conscious experience is used to guide the session. Equally, PCT attempts to explain the purpose of behaviour from the person's own perspective – what is important to the individual is their immediate perception rather than their outward behaviour, and PCT provides a framework for explaining how this process of goal-directed action occurs.

(3) PCT is grounded in biology and physics. There is no escaping the fact that people live in a physical world and are biological creatures. However, many theories either neglect these facts, or introduce them in a piecemeal fashion. PCT is a theory that explains how the biology of the brain and body can regulate its perception. The regulation of perception in PCT operates using a negative feedback system that is conceptually identical to the regulation of core biological variables such as blood sugar and body temperature. Moreover, the control systems within PCT operate in a parallel, continuous manner, akin to brain functioning and unlike the functioning of serial, digital computers that have been used within cognitive psychology as metaphors of the mind. Within PCT, the physical world represents the controlled variables that are manipulated through action driven by the lowest level of the control hierarchy (see Fig. 2).

(4) PCT integrates findings from various disciplines. An earlier review has explained how PCT can provide an integrative account of psychopathology (Mansell, Reference Mansell2005). To take one example, a range of psychological theories implicate ‘internal conflict’ as a cause of psychopathology. These include approach-avoidance conflicts in behavioural theories (Miller & Kraeling, Reference Miller and Kraeling1952), contradictory positive and negative beliefs in metacognitive therapy (Wells & Matthews, Reference Wells and Matthews1994), experiential avoidance whereby distressing internal experiences are suppressed or avoided (Hayes et al. Reference Hayes, Strosahl and Wilson1999), and direct attacks on the self within Paul Gilbert's social mentalities approach (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2005). PCT explains conflict in logical terms that are independent of content and therefore can apply across these, and other, existing theories – it is where two systems within the same individual attempt to shift the same experience in opposing directions. Yet the integrative capacity of PCT in published articles is much wider. It covers experimental/research methods, learning theory, psychophysiology, developmental psychology, social psychology, language and communication, work (business, economics, marketing and management), educational psychology, human factors, robotics, animal behaviour, evolutionary psychology, anthropology, political and philosophical psychology (Forssell, Reference Forssell2008). Figure 3 shows the rise in citations of Powers’ (Reference Powers1973) publication that reflects the diversification and increased utility of the theory. In particular, PCT forms the basis of contemporary models of self-regulation (e.g. Carver & Scheier, Reference Carver and Scheier1982; Karoly, Reference Karoly1993; Vancouver, Reference Vancouver2005), which are becoming increasingly influential within CBT (e.g. Wells & Matthews, Reference Wells and Matthews1994; Watkins, Reference Watkins2008).

Fig. 3. Citations of Powers (Reference Powers1973) since its publication (source: Google Scholar).

(5) PCT has its own evidence base. In addition to the application of PCT across disciplines, studies have been carried out to test its basic premises. For example, Bourbon (Reference Bourbon1996) devised a computer paradigm in which the participant's goal was to vertically move a horizontal line on the screen to line up pairs of lines that moved randomly up and down in the vertical plane. The computer measured the shift in the lines over time and created a negative feedback model to simulate the participant's later behaviour during the task. When the output of this model was correlated with the actual data at immediate follow-up, and during a follow-up 5 years later, the relationship was extremely high, at 0.997, indicating a highly accurate prediction. In another study, Marken (Reference Marken2001) created a PCT model to simulate the catching of a ball as a process of controlling its optical velocity relative to the horizon; this provided a close match with observed data from real baseball fielders. There are a large number of computer simulations that model different features of PCT (Powers, Reference Powers2008). For example, one simulation shows in detail how reorganization of multiple control systems governing different joints in the arm can gradually transform random, uncontrolled movements into a smooth, controlled action (Powers, Reference Powers2008).

Clearly, PCT is not without its controversy, which is explicable from its origins and its implications for our current assumptions about human behaviour. This article will now turn to the therapy that emerges as a consequence of this theoretical analysis.

MOL

MOL is a therapy derived from PCT that helps clients to regain control of the aspects of their lives that matter to them. A core principle of the therapy is that the therapist ‘should not get in the way’ – the therapist should do as little as possible in order to help facilitate as much client-driven change as possible. The therapist has two tasks – to get the client talking about the problem he/she wants to discuss, and to help the client ‘go up a level’.

It is presumed that it is the error resulting from conflict between control systems that attracts the client's awareness and provides a sense of struggling or trying to control a certain experience. The therapist therefore asks questions to help the client become further aware of this process of striving for control and what might be responsible for it being such a struggle (a conflicting control process). The therapist uses a limited range of methods to help the client to explore ‘up a level’ control – either by noticing disruptions in the stream of conversation (e.g. sudden changes in affect such as smiling; pauses in dialogue; notable eye movements) and enquiring about them, or by asking present-focused, reflective questions which guide awareness to the higher levels (e.g. ‘What do you make of the mixed feelings you are talking about?’; ‘What's going on for you right now as you say this?’).

According to PCT, once the client's awareness is at the level of control causing the conflict, reorganization can then work on promoting the change necessary to reduce the error and allow a more balanced pursuit of goals in future. The change is purely intrinsic, and occurs in a trial-and-error fashion.

There is no more to MOL; no tools or further techniques. It can be used immediately without any other forms of assessment, and applied to any presenting problem, whether psychopathological or otherwise. In line with PCT, it is hypothesized to work best when the client can control the number, frequency and duration of their sessions.

Five cons of MOL

Any new therapeutic approach can raise concerns, and MOL is no exception. This article will focus on five reasons why CBT therapists may be cautious of taking it up:

(1) Few people use MOL. It takes a small leap to try a therapeutic technique that is in its early stages of acceptance. Most clinicians will want to read more before considering it, but may be willing to do so when they understand what it can offer. Others may want to wait until the evidence base for the therapy is unequivocal, as is the case for traditional CBT.

(2) The process of change must be inferred. According to PCT, long-lasting change is always intrinsic, whether it occurs during MOL, other forms of psychological therapy, or during natural recovery; change occurs through the reorganization of the properties of control systems (Carey et al. Reference Carey, Carey, Stalker, Mullan, Murray and Spratt2007). MOL helps to harness this process as efficiently as possible and direct it to the higher-level system that is most responsible for the problem. Therefore, in order to be a MOL therapist, one must accept that observable behaviour, and even self-reports of symptoms, are only clues as to whether long-lasting and adaptive change has occurred. This is not to say that these measures are worthless; it means that the therapist needs to be aware of making assumptions about what they mean and measures will vary in their relationship to intrinsic change, which is an empirical question for longitudinal studies of recovery to answer. One way that MOL manages this issue is that the client is allowed to judge when they no longer need the therapist, and they can return if problems recur. PCT suggests that the client has the most direct information on whether they have a current problem, and providing them with this combination of responsibility and immediate access to therapy enables their development of perceived control and effective self-regulation.

(3) The MOL therapist lets go of control to a large degree. PCT proposes that effective self-regulation can only occur from within the client's own internal systems. Attempts by another person to control what the client is experiencing are counter-productive and are typically forms of arbitrary control – attempts by one system to control a variable that is also under the control of another system. According to PCT, this is the principle cause of the internal conflict that maintains psychological distress. Therefore, the MOL therapist tries to do as little to disturb what matters to the client, whilst at the same time trying to help the client become aware of their goals, the conflict between them, and their awareness of the higher-order goals that are setting the conflicting standards. The MOL therapist cannot advise, educate, or even offer their own interpretations for the client to consider. Even the act of going back to something the client has said in a previous session can be seen as potential arbitrary control in relation to the client's goals in the present moment. Within workshops on MOL it can be a struggle for therapists to let go of their previous styles of working with patients (Mansell & Tai, Reference Mansell and Tai2008). However, as they take on board the theory, listen to client's feedback regularly, and put the time and energy into training, they soon experiment with increasing MOL within their practice.

(4) MOL takes a great deal of concentration. While the MOL therapist may drop their attempts to control what is going on for the client, they need to concentrate on their own goals throughout. They need to listen to everything that the client says to identify the ongoing control of perception that the client describes as going on right now, and observe the client closely for disruptions. As every therapist utterance is ‘accountable’ to the theory, the therapist is balancing their need to formulate a question that helps the client describe their thoughts and feelings relating to the current problem, with the need to make it as brief and open-ended as possible, whilst remaining vigilant for further signs from the client of disruptions that arise. When listening to or transcribing MOL sessions, they are often highly interactive and typify a collaborative and empathic attunement between the therapist and client that seems to arise from this process. Clearly the MOL therapist needs to concentrate and focus on the present to adhere to the technique, and this can be a challenge for beginners. One way to build up MOL is not to try to be perfectly adherent from the first session, but to gradually build it in to existing CBT practice.

(5) The outcomes of MOL are hard to evaluate in a controlled manner. While adherence to MOL can be assessed systematically, it is not easy to assess within an experimental design such as a controlled trial. First, there is not a fixed number of sessions to match between MOL and a comparison group. Second, the process of recovery is proposed to occur naturally. According to PCT, all psychological therapies provide the catalyst for change and merely differ in their efficiency (although some may have features that actually hamper recovery). Therefore, the real index of outcome according to PCT is the ratio of degree of client-defined progress to the amount of time spent in therapy. This should be music to the ears of CBT clinicians and researchers, whose aim is to innovate accessible, brief interventions. Yet, because it entails different assumptions about methodology, it may be difficult to accept in practice.

Five pros of MOL

The above issues help to illustrate the shift in mindset that may lead some clinicians to feel apprehensive about MOL. Nevertheless, they need to be pitched against the potential advantages:

(1) MOL involves adopting just two goals. While many CBT therapies involve a range of tools and techniques, MOL requires the therapist to hold just two goals in mind – to help the client notice experiences relating to their current problem and background thoughts about that problem. Because the client is required not to do more than is necessary to achieve these goals, there are no further strategies, tools, or behaviours to learn. The process of training and self-improvement involves assessing one's adherence to these goals across different clients. The simplicity of the therapy should make it easy to assess adherence. A MOL adherence scale is being developed (W. Mansell, S. J. Tai, T. A. Carey, R. J. Mullan, C. Spratt & T. Bird, unpublished material), based on the Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale (Blackburn et al. Reference Blackburn, James, Milne, Baker, Standart, Garland and Reichelt2001; J. E. Young & A. T. Beck, unpublished material) for this purpose (see Appendix 1). The scale assesses six characteristics: focusing on the problem at hand, focusing on the client's present perception; noticing disruptions; asking about process rather than content; maintaining curiosity, and treating the individual with respect as another sophisticated, controlling, living system. It remains to be tested whether the scale can be simplified further.

(2) MOL is directly related to the theory. Within CBT, emphasis is placed upon the importance of theory–practice links. However, there is often no direct correspondence between every aspect of the therapy and the theory. For example, there is little theoretical explanation for why the therapeutic relationship in CBT needs to be collaborative (Waddington, Reference Waddington2002). With MOL, the therapist can directly derive every element of the therapy from the theory – PCT. This level of correspondence allows reflective practice and supervision to be tightly focused and grounded around a shared model of the mind.

(3) MOL is like ‘ultra’ cognitive therapy. Cognitive therapy is designed to be present-focused, centred around the client's goals and facilitates the client's shift in perspective on his/her experience. Yet, traditional CBT therapists often find themselves talking about experiences in the past, typically they only check the client's goals at the start of the session (during agenda setting), and they may offer some of their own formulations or models for the client to consider. Arguably, MOL more tightly adheres to cognitive therapy principles – it is focused on present perception as it unfolds in the moment, explores the client's goals in an ongoing manner, and provides multiple opportunities for the client to provide higher level perspectives on their mental processes in an open-ended manner. Different forms of CBT adhere to the principles to different degrees. Table 1 provides a subjective analysis of how certain types of CBT adhere to the principles, along with further important features such as efficiency and applicability across disorders. It is difficult to make explicit comparisons between existing CBTs and MOL and to place its methods within CBT terms. Nevertheless, something can be said. Essentially, MOL seems to engage what is recognized as a ‘metacognitive’ or ‘mindful’ mode in CBT. Yet, it adopts this mode to the client's current perceptions involved within their own current choice of what to talk about, rather than to any specific class of experiences (such as their breath, or their traumatic intrusions). The detection of background thoughts in MOL is somewhat similar to ‘thought catching’ or spotting ‘hot cognitions’ in CBT, yet the rationale is explicitly to identify outputs of higher-level control systems. Again, these higher-level systems may map on to familiar terms in CBT – dysfunctional attitudes, core beliefs and values. Yet MOL is unconcerned with this terminology – it is merely the view that these systems set the potentially conflicting standards for lower systems that is important. From this point onwards, MOL is perhaps better understood by what it leaves out than what it includes – no use of diagrams, homework, thought records, etc. This is not to say that such techniques are not helpful – they may in themselves be good ways to promote reorganization of higher-level systems; the MOL claim is that they are not necessary for change. Arguably therefore, MOL provides a more efficient, accessible, easily trainable, and client-centred cognitive therapy than the alternatives available.

(4) MOL promotes service-user choice and empowerment. There is an increasing emphasis on promoting service-user involvement in clinical practice and facilitating the networks that aid people's self-driven recovery. PCT provides a theory for why this will be helpful to people – people function effectively through their own flexible regulation of their perception rather than by following specific rules or behaviours proposed to them by others. MOL is delivered according to these principles. In particular, clients are given as much choice as possible about how their therapy is delivered. Therefore, in line with recent advances in other forms of CBT (Giesen-Bloo et al. Reference Giesen-Bloo, van Dyck, Spinhoven, van Tilburg, Dirksen, van Asselt, Kremers, Nadort and Arntz2006), MOL allows clients to come to therapy for as long as they feel they need it. Interestingly, when people are given this level of control, they seem to use it efficiently. When this method of service delivery was used during the MOL therapy delivered in Fife, Scotland, the mean number of sessions attended per client was 3.9 (Carey, Reference Carey2005). Thus, MOL not only seems to facilitate client choice, but does so in a way that does not encumber services.

(5) MOL has an evidence base. In addition to the evidence supporting PCT, several practice-based studies indicate that clients improve in well-being during MOL and at follow-up (Carey & Mullan, Reference Carey and Mullan2008). An overview of this evidence is provided elsewhere (Carey, Reference Carey2008). There is a clear need for further research including comparisons with alternative treatments, exploration of whether the mechanisms of recovery are consistent with the theory, and an analysis of whether level of adherence to MOL moderates rates of improvement.

Table 1. A subjective analysis of the features of Method of Levels in comparison to examples of other forms of CBT

Plus symbols represent the subjective degree of each property within each therapy (+++ very high, ++ high, + moderate).

This elaboration of five pros and five cons of MOL is designed to help the CBT therapist decide whether they would like to read more about the approach with a view to trying it out. It is worth noting that while an argument has been made for the benefits of MOL, it is not the only intervention that follows from PCT, nor is it necessarily fully refined and understood. Five of these issues are covered here: non-verbal therapist behaviour, down-level questioning, maintaining engagement, minimal self-report and social/environmental constraints.

Non-verbal therapist behaviour

MOL involves great attention to the client's non-verbal signs of ‘disruption’ but says little about the therapist's non-verbal behaviour. The main reason for this is that if the therapist is holding the two MOL goals in mind, his/her behaviour is merely a means to that end, and cannot be predicted or recommended. Nevertheless, clinical impressions suggest that, in addition to the regular questioning, the MOL therapist faces the client, tends to lean towards him/her, looks slightly quizzical, smiles occasionally and often make utterances that are not actually questions – sometimes modest expressions of curious surprise – ‘ahhh’ – ‘mmm’. Although the therapist presumably makes these actions in order to refocus attention on the client's internal perceptions, it remains to be tested whether these actions aid the therapy.

Down-level questioning

While the primary aim of MOL is to go ‘up levels’ to the systems setting conflicting goals for lower-order systems, it is not an easy task, and there may be long periods when questioning or commenting does not reveal a higher-order goal. In these instances, the therapist maintains their second goal – to help the client describe their current problem. Often client's replies reveal lower-order perceptions – mental imagery, bodily states and states of mind with which the client is struggling. The MOL therapist may then explore the process of control of these perceptions with the client, which is again in order to access higher-level control. For example, when clients have mental images the MOL therapist can ask: ‘How do you know you have this image?’; ‘Is the image staying the same or changing?’; ‘Is it moving or staying still?’; ‘Are you doing anything with the image?’ One possibility is that these questions promote reorganization, as they allow the client to experiment with setting different perceptual standards for the image – do they want to get closer to it or further away? The client may eventually become less conflicted about whether to access the image or suppress it as they develop a more coherent strategy for managing the experience. Further research could elucidate this process.

Maintaining engagement

Maintaining engagement is not the primary goal of MOL. It is proposed that clients will continue to come to therapy as long as they personally feel that they benefit from the sessions. Any attempts to try to maintain engagement against the client's choice (e.g. persuading them to come to more sessions) would involve having the therapist make the assumption that the therapy will be successful for this person, rather than allowing the client to exercise his/her own judgement, and at worst it would be an instance of arbitrary control that could exacerbate problems. Nevertheless, this does not prevent the therapist from making every attempt to make the therapy as accessible as possible and managing any obstacles that the client describes. For example, the process of engaging with the therapist is a controlled process that can be discussed using MOL itself. Taking a more practical example, it is possible for a version of MOL to be provided by telephone for clients whose problems prevent them from meeting with the therapist at the service. In addition, although outside MOL, the therapist can provide the client with access to a range of information, including other therapies that are provided by the service, with the option of returning to MOL at a later date.

Minimal self-report

As it stands, MOL relies on verbal communication. Yet, language does not necessarily provide a direct ‘read-out’ of perception. Some clients may be unwilling or unable to put their experiences into words. Typically, the MOL therapist will allow the client to talk about what they can – for example to describe the qualities of a traumatic image without revealing its content if they are concerned about revealing what has happened to other people. Furthermore, therapy appears to rely on the client being able to hold internal experiences within imagination – this is a specific mode of operation whereby the higher-order systems short-circuit lower-order levels, and control experience ‘as if’ the environment was providing perceptual feedback (see Fig. 2). This mode may be less accessible in certain individuals including some in-patients, very young children, or intellectually impaired clients. In these instances, it is possible that other forms of communication could be used (e.g. drawing pictures). Alternatively, there is a form of formulation based on PCT that creates hypotheses about a person's goals: testing the controlled variable (Marken, Reference Marken1997). Readers are referred to Rick Marken's work for further details; this is an avenue for future clinical development.

Environmental constraints

Within PCT, the external environment can place constraints on how perception can be controlled; while many individuals can identify environments that match their needs, certain environments may be so chaotic, controlling or inflexible that self-directed change is greatly hampered. Thus, making environmental changes at a social or public health level can still be consistent with PCT even though it is not MOL.

Conclusion

This article has provided an overview of both the controversies and potential benefits of adopting MOL. This article suggests there is a strong case to situate MOL as a paradigm example of a cognitive therapy that can enhance service efficiency and promote service-user choice and empowerment. However, considering the huge theoretical and cultural shift this might entail, the adoption of this new technology may be slow or sporadic. The reader is encouraged to take a wide perspective on PCT and MOL among the diverse range of CBT theories and therapies available, test them out for size, and vitally, to make their own regular use of client feedback to judge the utility and effectiveness of their therapeutic practice. This can be done a small step at a time, towards, or away, from MOL.

Summary points

(1) Perceptual Control Theory (PCT) proposes that behaviour is the control of perception.

(2) PCT has informed the development of Method of Levels (MOL), which is a cognitive therapy aimed at guiding awareness to help clients find their own solutions to their problems.

(3) Adopting PCT has a range of conceptual advantages over other psychological theories, but is a challenge considering its origins in engineering, mathematics and biology.

(4) Using MOL holds many benefits, but may not fit with many therapists’ preconceptions about the nature of psychological therapy.

(5) MOL can be incorporated into CBT practice in a graded manner, in a trial-and-error fashion, guided by client feedback.

Appendix 1. MOL Adherence Scale Version 1.3Footnote a

Therapist: _______________ Patient: __________ Date of session/session #: __________ Supervisor: _______________ Date of Rating: _______________

( ) Videotape ( ) Audiotape ( ) Live Observation

Directions: For each time, assess the therapist on a scale from 0 to 6, and record the rating on the line next to the item number. Descriptions are provided for even-numbered scale points.

If you believe the therapist falls between two of the descriptors, select the intervening odd number (1, 3, 5).

If the descriptions for a given item occasionally do not seem to apply to the session you are rating, feel free to disregard them and use the more general scale below:

Focusing on the problem at hand

0 – The problems are always those decided upon by the therapist rather than the client

1

2 – The problems are sometimes those suggested by the client

3

4 – The problems are generally those suggested by the client but the therapist tends not to follow how they change in an ongoing manner

5

6 – The problems are always those suggested by the client and the therapist allows the client to readjust and reprioritize their problems in an ongoing, sensitive manner

Focusing on the client's present perception

0 – All discussion is focused on the past or future

1

2 – Some of the content of the session is focused on the present experience

3

4 – Most of the content of the session is focused on the present experience

5

6 – The therapist takes every apparent opportunity to focus the content of the session on the present experience

Noticing disruptions and background (higher level) thoughts

0 – The therapist never attempts to access disruptions or background thoughts

1

2 – On occasions, the therapist asks about disruptions and background thoughts

3

4 – The therapist asks about disruptions and elicits background thoughts some of the time

5

6 – The therapist regularly and sensitively asks about disruptions and elicits background thoughts

Asking about process rather than content

0 – The therapist focuses entirely on content and never asks about the process of perception and control

1

2 – The therapist typically asks about content but occasionally asks about the process of perception and control

3

4 – The therapist often asks about the process of perception and control but sometimes focuses on the content

5

6 – The therapist takes every apparent opportunity to ask about the process of perception and control

Maintaining curiosity

0 – The therapist is not curious, regularly makes assumptions and offers advice within an expert role

1

2 – The therapist is sometimes curious, but often makes assumptions and offers advice

3

4 – The therapist maintains curiosity most of the time but occasionally makes assumptions and offers advice

5

6 – The therapist maintains empathic curiosity throughout, never offers advice and consistently attempts to clarify terms used by the client.

Treating the individual with respect, as another, highly sophisticated, controlling, living system

0 – The client is expected to be utterly compliant with the therapist's own goals and suggestions

1

2 – The client is sometimes treated as having personal goals and is sometimes seen to function through the control of experience

3

4 – The client is generally treated as having personal goals and to function through the control of experience

5

6 – The client is always treated with respect as another, highly sophisticated, controlling, living system with personal goals, who functions through the control of experience at multiple levels.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to Tim Carey, Richard Mullan, Sara Tai, Chris Spratt, David Goldstein, Tim Bird and of course, Bill Powers, for their support with the development of the ideas within this article.

Declaration of Interest

None.

Learning objectives

After reading this paper, the reader will be able to:

• Consider the benefits and drawbacks of adopting Perceptual Control Theory (PCT) as a framework for human psychology.

• Consider the benefits and drawbacks of incorporating Method of Levels (MOL) into CBT practice.

• Identify the characteristics of MOL that classify it as a paradigm example of a cognitive therapy.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.