Introduction

This article aims to investigate the socio-ecological relationships between the plains of northern Italy and Argentina through the migration of Italian rural workers. Notably, we focus on cultural practices and various ecologies that constituted the landscape of the padani, the people of the Po Plain, and specifically those who came to Argentina from Emilia-Romagna between 1870 and 1955 (Devoto Reference Devoto2007). Oral history and memory studies have broadly informed works on Italian migration to South America (Franzina Reference Franzina2014; Canovi Reference Canovi2009). Despite this, the relationship between migrants, memory, and the environment has been largely overlooked. By focusing on the memories of Emiliano-Romagnoli Footnote 1 lowland peasants we want to emphasise how cognate socio-ecological imaginaries and practices signified the relationships between northern Italian migrants and the two plain landscapes that they inhabited: the Po Plain and the Pampa Gringa.

We argue that there exists a lively connection between the migrating landscapes of Emiliano-Romagnoli people and the process that led to the transformation of Pampa Húmeda into a Pampa Gringa in Argentina. While the former term indicates a geographical region, the latter refers to a cultural landscape which resulted from the intensive agricultural colonisation that transformed the Argentinian plains between the late nineteenth and the mid-twentieth centuries. Until the 1870s, the pampa region was still native grassland subject to seasonal flooding, mostly used by natives and nomadic cowboys, gauchos, for cattle production under dryland conditions (Gallo Reference Gallo1984; Viglizzo et al. Reference Viglizzo, Lértora, Pordomingo, Bernardos, Roberto and Del Valle2001). Whilst profoundly different to Argentinian economic, social and racial contexts, the Po Plain also went through a similar ecological transformation based on water control and land reclamation for agricultural purposes (Bevilacqua Reference Bevilacqua1996, 33–9). Padani peasants were the protagonists of both these transformations. The spread of specific plants such as alfalfa, as well as the introduction of large livestock farms and massive land use changes, all contributed to such a transformation. The first and most transformative practice introduced in the pampa in the last two centuries has been intensive agriculture.

Agricultural colonisation and European immigration have been at the centre of Argentinian national development since the end of Juan Manuel de Rosas era in 1852. The future president Domingo Faustino Sarmiento (Reference Sarmiento1999, 18) believed that agricultural colonisation was the instrument for transforming ‘the desert of the pampa’ into a modern nation. His most influential text, Facundo: Civilization and Barbarism, was inspired by United States frontier narrative. ‘Civilisation’ was coupled with agricultural and settler colonialism, in opposition to the ‘barbaric’ land use of nomadic cattle-drives which dominated in Argentina under Rosas’ rule. On the same lines, the main theorist of the Argentinian constitution, Juan Bautista Alberdi, synthesised the pampas colonisation plan through the famous motto: ‘to rule is to populate’Footnote 2 (Reference Alberdi2007, 18). The joint action of European capital and Italian labour would constitute the material basis to enact such a transformation, entailing a radical change in the material and cultural landscapes of the pampas as well as in the forms of land ownership and land use that defined such an environment.

Whose landscapes? Micro-histories of migration

As geographer Don Mitchell (Reference Mitchell1996, 20) wrote, landscapes might very well erase the history of the people that materially produced them through their work. In fact, the process of making a landscape concretely unfolds as an inscription of a certain kind of landscape inasmuch as it is an erasure of other landscapes. In Argentina, three landscape visions and experiences overlapped, conflicted and finally mixed to form a hybrid: the pastoral-nomadic landscape of native people and gauchos; the agricultural landscape of modern white colonisers, prefigured by Sarmiento and Alberdi; and the itinerant landscapes of European immigrants, in particular the landscape of northern Italian migrants. This ever-changing juxtaposition, contradictory and transformative at once, ended up by defining and reorganising Argentinian nature as well as the place-making and identity processes played out in the pampas.

Landscape is a key category to study the relationships between identity and the environment. With the end of exploratory geography and the reduction of the planet to a geographical representation, the notion of landscape began to indicate the complex interplay between the physical environment and the perception, affection, representation, aesthetics and practices that signify the forms of belonging to a place (Farinelli Reference Farinelli, Farinelli and Cavazza2006). As with familiar places, transnational forms of belonging are all embedded and signified within specific landscapes. In other words, landscapes are the socio-cultural, memorial, and material lenses through which individuals or communities recognise themselves – or not – as belonging to a place. From this standpoint, ‘migrants are those who change landscapes’ (Canovi Reference Canovi2009) and who daily experience and reproduce a complex dialectic process of appaesamento and spaesamento, to quote Italian anthropologists Ernesto De Martino (Reference De Martino1977). The Italian term spaesamento refers to the feeling of being out of place while insisting on a missing link with a given landscape. In this perspective, the identity-making process that characterises the migrant condition is played around this process of recognition (appaesamento) and nonrecognition (spaesamento) of a specific form of belonging between one or more subjects and a given landscape. Migrants are active subjects in this transnational situatedness within landscapes. As Armiero and Tucker (Reference Armiero and Tucker2017) wrote, ‘migrants are nature on the move’, and along with their mobile trajectories between places, natures move too.

Migration histories are always ubiquitous. All migration stories encompass the relationships of at least two distinct places and two trajectories of belonging which are constantly re-elaborated in relation to an elsewhere and a form of otherness (Sayad Reference Sayad1999). We maintain that there exists a geohistorical knot that weaves together the two-millennia-long struggle against intruding and running water in the Italian Po Plain and the transformation of the Argentinian Pampa Húmeda into a livestock and agricultural farming plain. We use the term geohistories, for those histories are at once geographically itinerant (Braudel Reference Braudel1995) and geologically grounded (Valisena Reference Valisena2020), and they bring together distant places, practices, and memories. Discrete socio-ecologies and practices form layers in landscapes, and it is through processes of appaesamento that those layered landscapes unfold to create hybrid environments. In this study, we utilise this geohistorical approach to underline the continuous relationship between distant emigration and immigration landscapes. With this article, we want to offer a micro-historical perspective on the environmental history of migration, showing how place-based socio-ecologies informed the migration chains that characterised the two waves of the Great Italian Migration to Argentina between 1870 and 1930 and 1945 and 1955 (Devoto Reference Devoto2007).

Pampas as a colonial frontier and the role of Italian immigrants

‘El pais del porvenir’ – the land of the future. This is the motto used by Argentina's rulers to depict the Republic as a modern progressive nation at the end of Rosas’ dictatorship in 1852. Argentinian intellectuals and political élites relished distinguishing their home country from other Latin American states. In this narrative, elaborated as a political programme by Rosas’ opponents, Argentinian exceptionalism was built on a peculiar assemblage of a unique natural environment, the pampas, and on ethnic and racial discrimination. This narrative, of white settler colonisation, is well summarised by the popular saying ‘Argentinians were born on ships’,Footnote 3 a belief which is hegemonic even today in large sectors of Argentinian society. Eventually, this discourse led to the invisibilisation of indigenous landscapes and the systematic discrimination of non-white and non-European people – in Sarmiento's words, ‘the barbarians’ – while, on the other hand, it exalted white immigrant labour as a means to colonise Argentina's inner frontier: the pampas.

Significantly, pampa is a Quichuan word now incorporated into Spanish. Originally pampa indicated the native grasslands lying between the Atlantic Ocean and the Andes, but the Spanish colonisers used the name to refer to all indigenous people living in the plains regardless of their distinctive cultures and languages. Now, the term indicates the vast agricultural and livestock farming plain – 52 million ha, almost double the size of Italy (Viglizzo et al. Reference Viglizzo, Lértora, Pordomingo, Bernardos, Roberto and Del Valle2001) – between the Rio de la Plata river basin (including Uruguay and the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul) to the north, the Andes to the west, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, and Rio Colorado to the south. The humid grassland is called Pampa Húmeda, while the semi-arid area is called Pampa Seca. During the 240 years of Spanish dominion intensive agriculture faced several challenges: the extension of the area; the strong presence of combative native communities who controlled most of the land; and difficulties draining water from the meadows. Despite these, the introduction of livestock farming was achieved. From the sixteenth century onwards, Spanish colonisers imported cows, sheep and horses, but the lack of settlers, roads and safe commercial routes kept the economy at a quasi-subsistence level for centuries (Gallo Reference Gallo1984, 22–29). It was not until 1860 that maize and wheat cultivation became extensive around the provinces of Santa Fe and Buenos Aires, but the transformation was so effective that in three decades Argentina ceased being a net importer of cereals and become the third net exporter worldwide (Gallo Reference Gallo1984, 209). Such a rapid and intense change in the land led to the extinction of many native species, rendering the pampas a very fragile environment in which soil erosion, pollution, the proliferation of endemic alien species and high loss in biome diversity were massive (Viglizzo et al. Reference Viglizzo, Lértora, Pordomingo, Bernardos, Roberto and Del Valle2001). Furthermore, anthropic concentration steeply rose in the twentieth century, with the province of Buenos Aires now hosting more than one-third of the entire Argentinian population.Footnote 4

Numerous indigenous communities – 35 of which are still present in the country according to INDEC (2010) – inhabited those immense flatlands and they fought fiercely against the European colonisers who settled around Rio de la Plata. From the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries, a series of colonial wars were waged by the Spanish army, with modest success given that most of the pampas were under indigenous control until Rosas began the infamous campaña al desierto in 1833. The people of the pampas were the Querandíes and Charrúas in the north-east and all the way west to the Tandilia and Ventania sierras and towards Santa Fe to the north; the Mamulche-Rankel inhabiting the central area around Rio de la Plata and the provinces of Pampa and Córdoba; and the Tehuelche in the south (De Jong, Reference De Jong2016).

Despite being considered uncivilised, the indigenous people's livelihoods constituted the foundation of gaucho culture and imaginaries, based on nomadic cattle farming carried out by mixed heritage wranglers. Under Rosas’ rule, gaucho culture was exalted as a symbol of Argentinian values and lifestyle as opposed to Europeanising tendencies. The national poem of Argentina, Martín Fierro, by José Hernández (Reference Hernández1953), celebrated this world-view in its dying days.

This vision of Argentina was strongly combatted by the so-called Generación del ’37. This group of intellectuals included among others Sarmiento and Alberdi, and they fiercely opposed Rosas’ federalist politics. The Generación del ’37 despised Spanish culture, which they perceived as retrograde, while at the same time they rejected any connection with the indigenous people of Argentina, their culture, economy, and the kind of environment they inhabited. After Rosas’ fall, Generación del ’37's vision heavily shaped the 1853 constitution and the politics of future governments. In the eyes of the white Argentinian elite of European ascendence who took control of national politics after Rosas, the immense grasslands of Argentina were a desert, in the same way as the United States’ inner frontier was ‘empty’. The presence of indigenous people and their use of the natural environment was a major obstacle towards the progress of the Republic: natives despised private property and enclosures, they conducted a semi-nomadic life, and threatened white colonisers with their continuous incursions.Footnote 5 It was against native people and their environment that the young general – and future president – Julio Argentino Roca conducted the last campaign to secure the control of the pampas, between 1878 and 1885: the ‘Conquest of the Desert’. Roca's war was the final act of a series of military campaigns which from the 1870s onwards transformed the pampas into a tabula rasa, freeing it almost entirely from indigenous presence (Magrassi Reference Magrassi2005). As President Avellaneda said in 1875: ‘peopling the desert means to suppress the indios and to occupy the frontier’ (Bartolomé Reference Bartolomé, Medina and Ochoa2008, 5). According to the Argentinian statistical office, more than 11,500 natives were killed in Patagonia and Chaco provinces, while many more were imprisoned and displaced to peripheral areas (Trinchero Reference Trinchero2006, 131). Those figures do not include the number of people who died in the following years from famine, illnesses, and other war-related calamities, but the 1895 census estimates the indigenous population to be 180,000 compared to the pre-war figure of 300,000 (Bartolomé Reference Bartolomé, Medina and Ochoa2008).

Figure 1. The Pampa Húmeda today. Photo: Antonio Canovi, 2007.

With the indigenous people gone or pushed to the extreme periphery of the Republic, a new modern landscape could be created. As soon as the state gained control of the pampas, around 30,000,000 ha of land were sold to a small group of landowners (Bartolomé Reference Bartolomé, Medina and Ochoa2008). The barbaridad, despised by Sarmiento and eradicated by Roca, was as much a matter of socio-ecological and economic structures as it was a matter of race, property, and class. Following Sarmiento's and Alberdi's vision, in order for the Republic to become a modern state, hundreds of thousands of white European colonisers were to replace the gauchos and the natives in the plains. The land of the future was not for everybody.

The economic historians Pablo Gerchunoff and Lucas Llach (Reference Gerchunoff and Llach2007) identified three prerequisite conditions for the modernisation of Argentina between 1870 and 1895: the existence of a vast agricultural land – Pampa Húmeda; two key economic activities – agriculture and livestock farming; the incorporation of foreign capital – mostly English; and a labour force – mostly Italian. To those elements, one should add technological development that allowed the implementation of a wide transportation network of railways and steamships, linking Argentina to the global market.Footnote 6

As Claudio De Majo and Samira Peruchi Moretto (Reference De Majo and Peruchi Moretto2021) describe in their essay for this special issue, an enduring connection existed between Italy and South America. Genoese traders had built businesses in the Plata area since Spanish colonial times and a political link connected Italian exiles such as mazziniani and garibaldini with the uprisings in South American republics during the first half of the nineteenth century (Rial Reference Rial2014). Male and female seasonal migration (Audenino and Tirabassi Reference Audenino and Tirabassi2008), within or outside the Italian peninsula, had always been a key component of many dispossessed families or village-based economies (Bevilacqua, De Clementi and Franzina Reference Bevilacqua, De Clementi and Franzina2001; Rosental Reference Rosental1990). From 1880, these were severely affected by the European agrarian crisis. Cheap American wheat suddenly inundated European markets, destroying centuries-long socio-ecologies and hitting hard in peripheral and depressed areas such as the Bassa Padana (Fincardi Reference Fincardi2008). It was in this context of major agrarian and social crises that the phenomenon of golondrinas emerged, affirming the prosecution of Italian seasonal migration in capitalist world economy. Literally meaning ‘swallows’, golondrinas were day labourers who seasonally moved from the northern hemisphere to Southern American croplands following the two harvesting seasons (Franzina Reference Franzina2008). Given this economic, social, and historical background, it is evident that a culture of migration existed which fed the socio-ecologies and economy of the Po Plain as well as linking Italy to the Argentinian pampas. Parallel to this, the myth of America powerfully entered into the imaginaries of common people who, thanks to the technological improvements in marine transportation, could now afford the cost of the steamer voyage across the Atlantic.

Nevertheless, these political and economic linkages did not suffice to persuade Argentinian governors and colonial boosters to favour the Italian influx into the pampas. The elective immigrant group envisioned by Argentinian political elites and sanctioned by the 1876 Ley de Inmigración was the northern European one. For Sarmiento in fact, the perfect modern coloniser was the Briton, followed by German, French, and Scandinavian people. In his vision, Argentina was to become a better version of the United States (Sarmiento Reference Sarmiento1999). Italians, as the debate in the US about their whiteness would show a few decades later (Guglielmo and Salerno Reference Guglielmo and Salerno2003), were somehow on a lower level of the modern white pyramid in Western societies. However, the failure of most of the Argentinian recruiting campaigns in northern Europe and the obstinacy of the Italian emigrants opened the pampas to their arrival.

In the 1880s, Italians became the most numerous immigrant group in Argentina. Between 1876 – when Italy began to register migration records in the Bollettino mensile di statistica – and 1955, when the second wave of Italian emigration in South America ended, more than three million Italians moved to Argentina, while 800,000 people returned to Italy (Rosoli Reference Rosoli1978, 353–5; 372–4). The first to arrive were traders and ship businessmen from Genoa, followed by Po Plain farmers from Piedmont and Lombardy (Devoto Reference Devoto2007). Italians settled in the fluvial port of Rosario, the narrow streets of La Boca and the conventillos of Buenos Aires; but especially before the First World War, they also settled in the pampas, notably in the provinces of Santa Fe, Córdoba, and Buenos Aires. Starting from the 1880s, Pampa Húmeda quickly turned into Pampa Gringa (Gallo Reference Gallo1984). Italian presence in the plains became so preponderant – especially in the province of Santa Fe – that eventually the piemontese dialect would turn into the lingua franca of the pampas (Blengino Reference Blengino2005). As Italian journalist Luigi Barzini (Reference Barzini1902) wrote in a report published in the conservative newspaper Corriere della Sera: ‘We Italians are the worker bees of the big Argentinian hive. In fact, Argentina exists because of Italian labour. Without us Italians, Argentina would not have any production, nor agriculture, nor industry, nor theatres, palaces, ports, or railways. Our fellow Italians are making Argentina …’. What Barzini did not know was that well before Italian rural workers begun transforming the landscape of Pampa Húmeda, a crucial encounter between an Argentinian son of the pampa and a very similar modern landscape had occurred on the other side of the Atlantic.

A familiar landscape

Between 1845 and 1847, Sarmiento travelled in Europe, spending a few months in the Italian peninsula. The ‘Grand Tour’ was nothing memorable for him – quite the opposite. As Sarmiento wrote in his diary, the southern and central Italian cities, particularly, left him with a very negative impression: ‘… a semi-barbaric population … who stumble on travellers like a herd of buffalos and who are wilder than the bulls in the pampa’ (Sarmiento Reference Sarmiento1993, 254). Yet while traversing the Po Plain, Sarmiento caught a glimpse of the future of Argentina:

Italy, from Romagna to Lombardy, is a delightful garden. Little by little, the Apennines fade to make room for an immense countryside, a limitless plain seeded with civilisation and villages and covered by farmland and trees. It is an immense cultivated pampa crossed by waterways that end up in the Adriatic Sea, where they form the Venice Lagoon (Sarmiento Reference Sarmiento1993, 263).

Figure 2. The Po Plain around Reggio Emilia. Photo: Daniele Valisena, 2019.

A plain, dense with villages, cultivated fields, and waterways. Those are the three elements that rendered the Po Plain a familiar landscape to Sarmiento. Whilst in Argentina the canalisation of navigable rivers would set the pace for the transformation of the pampa, it was a road that defined the geo-historical coordinates of the Po Plain: the Via Emilia. The road was built by the Romans over 2,000 years ago, when they decided to leave Rimini, on the Adriatic Sea, to venture into the unknown geography of the plain towards the Alps. For 270 km the Via Emilia cuts the Po Plain diagonally, running parallel to the northern Apennine to the south, then crossing the Po River in Piacenza before ending up in Milan. The road was the first act of the Roman colonisation of Gallia Cisalpina: a trait which still marks the contemporary topography of Emilia-Romagna, with the Via Emilia working as the main geohistorical compass. Starting from the Via Emilia, the Romans began to trace square fields all around the road (centuriazione). By doing that, they progressively excavated ditches and remediated the swamplands. This long and patient action of reclaiming the land from water through land remediation work would become the most distinctive practice in the Po Plain's lowlands for two millennia. Agricultural historian Franco Cazzola defined this heritage as the hydraulic culture (Reference Cazzola1987, 44) of padani – a heritage that would be crucial in nurturing the rich tradition of agricultural associationism which grew in the Po Plain lowlands in the nineteenth century (Fincardi Reference Fincardi2008).

Travelling along the historic Roman road, Sarmiento understood the meaning of the anthropic transformation that had created the modern Po Plain: a laborious civilisation which coupled its own becoming with the progressive conquest of new remediated land (bonifica). Through the centuries, Po Plain swamps made way for rice paddies, woods were torn down and turned into cereal fields, fruit trees and vineyards curtained canal ridges to make the typical pre-industrial ecosystem of the region, la piantata (Bevilacqua Reference Bevilacqua1996; Sereni Reference Sereni and Zangheri1957). Alongside those changes in the natural environment, a very particular set of practices and knowledge came about to form the amphibious socio-ecology that characterised hundreds of thousands of Emiliano-Romagnoli. The Po Plain had its internal frontier too: a watery frontier made of lagoons, swamps, marshes, and fens, where malaria was endemic. The last great bonifica closed this watery frontier only in the first half of the twentieth century, right at the peak of the first Italian migration wave towards the Americas. In Sarmiento's mind, what had occurred in the Po Plain through land remediation was to happen in the pampas through the reclamation of land from indigenous people.

Entangling landscapes: Villa Cogruzzo-Pergamino-Cogruzzo

Emiliano-Argentinian scholar Aida Toscani de Churín wrote a detailed micro-historic research on the interplay between the two plains, using oral history and archival data. Focusing on the partido Footnote 7 of Pergamino in the province of Buenos Aires, one of the most important agricultural districts of the Pampa Húmeda, her research title is ‘enlazando llanuras’ – ‘entangling plains’ (Toscani de Churín Reference Toscani de Churín2009). By adopting a comparative perspective, Toscani argues that Emiliano-Romagnoli have an intimate and persistent relationship with the landscape they were born in. In Toscani's research, landscape is an interpretative category conceived as cultural entanglement, which is made up of an inextricable mélange of political, cultural, and social structures. Notably, she focuses on the chain migration that connected Pergamino with the village of Castelnovo Sotto, in the province of Reggio Emilia, Emilia-Romagna. Toscani identifies two main threads in this migrant micro-history: an agronomic thread and a political thread. The latter has been a recurrent argument in the migrant histories of Emiliano-Romagnoli around Europe and the Americas (Canovi Reference Canovi, Blanc-Chaléard, Bechelloni, Deschamps, Dreyfus and Vial2007; Reference Canovi and Bertucelli2012).

The peak of the first wave of Italian migration towards Argentina between the 1880s and 1890s coincided with the establishment of the socialist movement in the lowlands of Emilia-Romagna (Fincardi Reference Fincardi2008). Therefore, many Emiliano-Romagnoli who moved to Argentina carried in their cardboard suitcases a world made of socialist symbology, names, and imaginaries. This was the case for Bartoli and Martignoni families, who moved to the province of Buenos Aires from the villages of Castelnovo Sotto and Gualtieri respectively, both in the province of Reggio Emilia. Onomastics is a powerful means of demonstrating how imaginaries concretely shape world-visions, especially in a socialist de-Christianised context such as the Emilia-Romagna of the 1890s. Interviewed by Antonio Canovi in 2006, Vasco Cesare Martignoni, an Emiliano-Argentinian living in Tandil, revealed that two of his relatives born around 1900 as first-generation Argentinians were named Giuffrida and Bosco Barbato (Canovi Reference Canovi2009, 162). Strange names both to Argentinian and northern Italian ears, those names were nevertheless well-inscribed in the history of the pioneering Italian socialist movement: Giuffrida De Felice and Rosario Garibaldi Bosco were among the first socialist deputies to be elected to the Italian parliament in 1892. In 1893, they were arrested in the bloody state repression of the fasci siciliani (Sicilian Workers Leagues), among whose leaders was also Nicola Barbato. Nelly and Ruben Bartoli, in an interview with Toscani de Churín (Reference Toscani de Churín2009, 176) said that their firstborn in Pergamino was named Adelante (going forward) after the name of the Italian socialist journal Avanti.

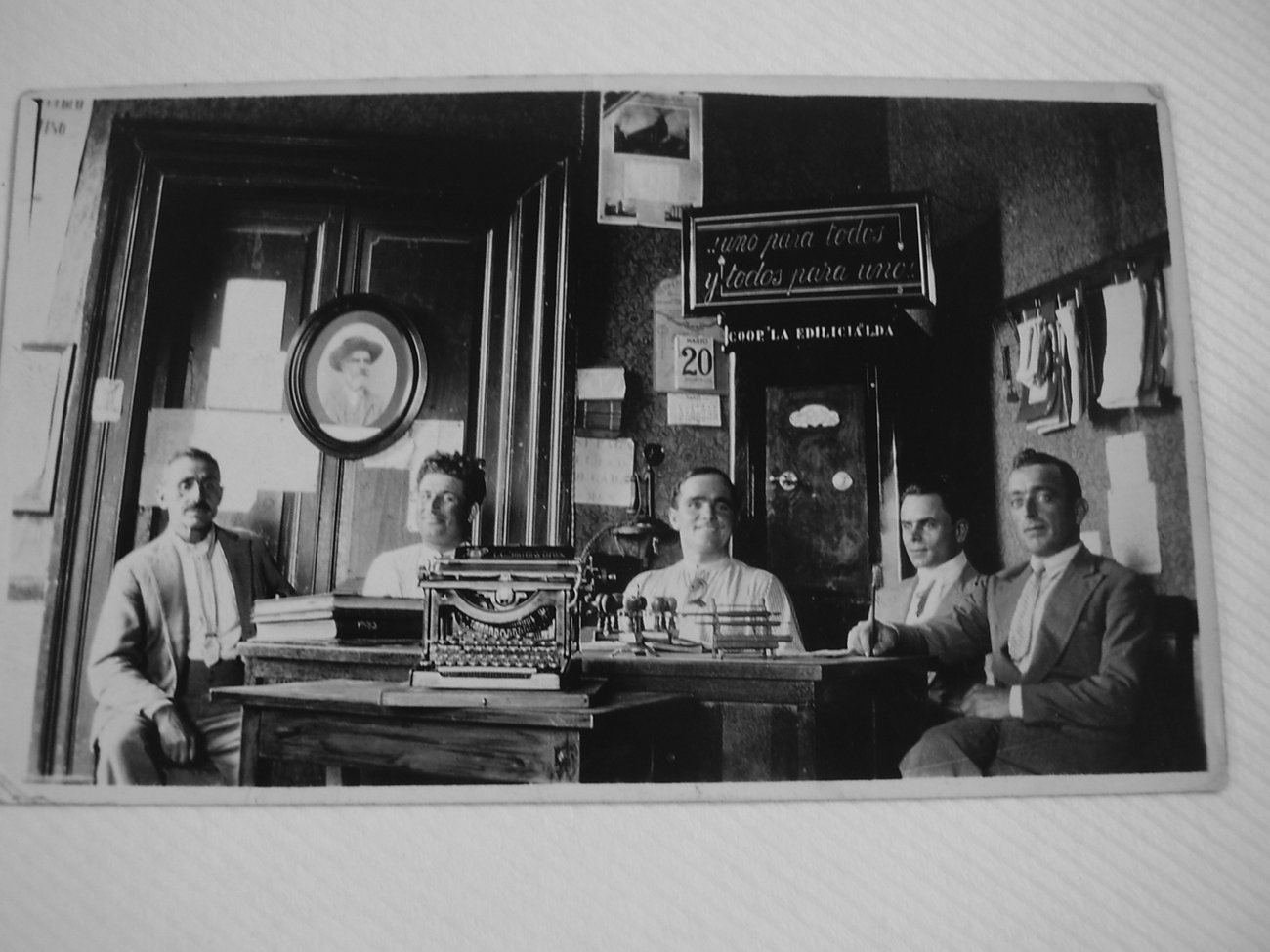

As political imaginaries shaped the familial and affective landscapes of Emiliano-Romagnoli, they also shaped economic activities. La Edilicia was the name of a construction cooperative which was founded in Pergamino by a group of Reggiani.Footnote 8 The socialist imprint of the company is proved by a photograph taken by the founding co-operators (Fig. 3). On the left of the office wall hangs an oval frame containing a picture of Italian parliament deputy Camillo Prampolini, who was known as the ‘prophet of socialism’ in his hometown of Reggio Emilia. On the right, there is a plaque with the motto: ‘¡Uno para todos y todos para uno!’, which can be understood as Alexandre Dumas’ literary quotation (‘All for one and one for all’), but also as a reminder of Prampolini's motto: ‘Uniti siamo tutto, discordi siamo nulla’,Footnote 9 which stood on the front wall of the first casa del popolo in Italy, in Massenzatico, Reggio Emilia. Additionally, the names of some of those co-operators belonged to the same socialist and futurist imaginary, such as Risveglio Melli: literally meaning ‘awakening’ or ‘awareness’, Risveglio in such a context assumed the value of a secular promise of a socialist future. In another interview with Antonio Canovi, Ovidio José Melli recounted that Risveglio had three siblings: Ribelle, Avvenire, and Frines. While the first brother's name ‘Rebel’ requires no explanation, the second brother's name translated into English would be ‘Future’. In Italian socialist tradition ‘il sol dell'Avvenire’ – the sun of the future – was a common reference to the rise of socialism. The sister's name, Frines, probably comes from Phrynes, the most famous of Athens’ hetairas, a group of wise, cultivated, and free women. These names exemplified the kind of political environment those Reggiani grew up in, an environment full of political militancy and secular culture (Canovi Reference Canovi2009, 258–9).

Figure 3. The main office of Cooperative La Edilicia in Pergamino. Courtesy of the Melli-Mastrandrea family.

The Mellis came from Villa Cogruzzo, a small hamlet in the municipality of Castelnovo Sotto. Cogruzzo was the scene of one of the most violent Fascist reprisals that beset the region in the 1920s (Zambonelli Reference Zambonelli1991; Canovi Reference Canovi2009, 177–83). As the 85-year-old Cogruzzo-born Ermes Saccani recounted to Canovi (Reference Canovi2009, 258), this event profoundly marked the memory of the people of Cogruzzo on both sides of the Atlantic, especially the ones that the Fascist blackshirts called the ‘socialists of Cornetole’. Eventually, the group decided to leave their plain for the pampa, following a migration network that had linked Cogruzzo with Pergamino since the 1890s. In this way, the advent of Fascism and the interruption of the establishment of progressive socialism was inscribed into a transnational migration landscape, which was informed by the local memory of Cogruzzo as well as by the new-future perspective offered by Argentina.

Even today, the imprint of the migration phenomenon is so strong that Cogruzzo resident Vittorio Bartoli enjoyed sharing the following anecdote with Canovi, subverting the usual home-place familial topography: ‘I know of 93 Bartolis and 35 of them are in Pergamino. All my relatives are there, I am the stranger!’ (Canovi Reference Canovi2009, 177). Vittorio inherited La Rosaura, a farmstead in Cogruzzo that bears the name of the farmhouse where his grandfather lived when he first moved to Pergamino. Even today, a wall painting on the front balcony of the country house commemorates that living transnational bond. Within the mural is a sundial that projects its long shadow over the two painted hemispheres of the Earth beneath it. The movement of the shadow replicates the migratory trajectory of the Bartolis, who left Europe in the East to find their fortune in America in the West. At the top of the painting is the date: 16.3.14 (16 March 1914), which refers to the date when the farmstead was established in Italy. Fascist repression would force this branch of the Bartolis to leave their newly-built home once again for Argentina, this time never to return.

La Rosaura sits in the hamlet of Cornetole in the heart of Reggio Emilia countryside. The abundance of space made it possible for the heirs to turn the ancient house into a museum of peasant society. The setting of the farmhouse is a sort of salvaged scrap of ancient Emilian lowland landscape at the time when the first emigrants left for America. It is an old centuriated country road built on a causeway with ditches all around. Alfalfa fields contoured by lines of fruit trees signpost the property's demarcation. Along the road are several semi-abandoned rural buildings. In Cornetole, most households were composed of sharecroppers (mezzadri), small farmers, and casanti – poor day labourers who moved from farmhouse to farmhouse, sharing the rent. Here, as in the nearby Via Badìa, every family has their own Argentinian migrants. Vittorio Bartoli is, body and soul, part of this translocal micro-world, which although structured as a place and family-based community, is split between two hemispheres. Without the Argentian part, Cornetole's Little Old Emilia would not exist.

During the 1890s and 1900s, Pergamino appears like a crossroads of migrant geohistories and translocal memories (Appaduraj Reference Appaduraj1996). What characterises such a migration phenomenon is that it is structured around a transnational form of belonging to the same community and the same trajectory towards modernity. By joining La Edilicia, its fellow workers could develop from immigrant farmers’ sons to men with a modern urban lifestyle, also thanks to the Ley 11388 de Cooperativas promulgated in 1926. From that time onwards, Risveglio Melli and his fellow co-operators would begin to work successfully for the Argentinian state all around the country, ending up in Resistencia, the capital of Chaco province. Likewise, in the timespan of one or two generations, most of the Reggiani in Pergamino would leave the fields to become professionals which, in their own terms, marked a migration success story. Territory-based migration routes such as the ones of Reggiani and other Emiliano-Romagnoli traditionally worked better than parental or family-based models (Bailey Reference Bailey1999). This was especially true when coupled with a strong system of rural associationism (Pizarro Reference Pizarro2008). This is important in relation to the much less successful migrant trajectories of fellow Italian migrants in the pampa region. Gaston Gori (Reference Gori1958) documented that between 1890 and 1909 the Argentinian government provided for 452,310 farmers and 274,145 day labourers. Those were the most fragile components of the agricultural labour force, constituting three quarters of Emiliano-Romagnoli immigrants in Argentina. As Gori reveals, while the amount of available land increased tremendously in those years, only 15 per cent of all immigrants were able to become landowners. On the contrary, in the partido of Pergamino, some two-thirds of all immigrants were able to buy their own piece of land (Toscani de Chiurín Reference Toscani de Churín2009, 67).

While in the rest of the provinces of Santa Fe, Cordoba, and Buenos Aires, most Italian immigrants failed to fulfil their dream of becoming landowners, in Pergamino, Emiliano-Romagnoli were able to successfully find their way to modernity. The appaesamento (adjustment) of the Emiliano-Romagnoli to the Argentinian landscape was made possible thanks as much to their hard work and agricultural familiarity with the plain, as it was through a co-operative and communitarian societal vision, which they fulfilled in Argentina after their future had been crushed by Fascism in Italy.

Trans-migrant landscapes: Tandil and the Cuenca Lechera

The Argentinian dairy district is situated between the provinces of Santa Fe, Cordoba, and Buenos Aires. As late as the 1870s, most of the agricultural areas south of the city of Rosario were roamed by flocks of sheep driven by gauchos (Gallo Reference Gallo1984, 129). The few existing agricultural colonies followed the course of the Rio Paraná, the water highway of the time. In those days, Argentina still imported wheat and other crops, moving sheep and cattle seasonally from low grasslands to drier pastures to avoid regions subject to seasonal flooding. Starting from 1875, Argentina turned into a net exporter of cereal crops, and in 1895 the South American republic became the third net exporter of cereals worldwide (Scarzanella Reference Scarzanella1986, 94). Railways became the main game-changer in the Pampa Húmeda transformation, and with the trains, immigrant gringos arrived. Gringos settled in newly founded colonies which followed the expanding frontier on former indigenous land freshly acquired by English, Swiss, and German capitalists. In Santa Fe alone, the most gringa province of the Pampa Gringa, some 365 colonies were raised in 20 years (Gallo Reference Gallo1984). Many of those colonies are still there, and they bear evocative names such as Nuevo Torino, Colonia Cavour, Colonia San José, Progreso, Sarmiento, and Humboldt. Railways brought a change in the socio-ecology, as well as in the dwelling landscape of Pampa Húmeda. Padani carried with them the memory of the characteristic villages and ridged farmlands of their homeland – which turned into enclosures in Argentina. The entrance gate typical of medieval Italian towns was transferred to the pampa and adorned with emblems and coloured murals, while at the centre of their new villages Italians built a square, a church, and a theatre, where it was common to hear Verdi's operas.

As agricultural historian Emilio Sereni wrote (Reference Sereni1961), agrarian landscapes should be interpreted as cultural footprints. There are cultural and agricultural stratifications that need to be deciphered, and there are human and non-human stories that bind them together. The transnational agricultural landmark that linked the distant geographies of the Pampa Húmeda and the Po Plain was alfalfa, the most used legume for hay and forage. Alfalfa had travelled a long way from ancient Persia – where the Greeks first saw it and referred to it as the herb of the Medes – to the Mediterranean area, and from there to both sides of the Atlantic and all temperate areas around the world. Today, Argentina is the second largest producer of alfalfa in the world after the United States (Viglizzo et al. Reference Viglizzo, Lértora, Pordomingo, Bernardos, Roberto and Del Valle2001). Aside from the cereal farming boom, alfalfa paved the way for intensive beef cattle farming, and by doing that, allowed the development of a strong dairy business in both plains. Cheese production is big in Italy even today, with the Po Plain leading in production of world-renowned cheeses such as Grana Padano, Gorgonzola, and Parmigiano-Reggiano. It comes as no surprise that Italians exported their dairy skill to their new American homes.

In Tandil, the chief town of Argentinian dairy district in the province of Buenos Aires, we encounter Reggiani such as the Martignoni and the Cantarelli families, the latter originally from Gattatico, a village at the border between Parma and Reggio Emilia provinces. Dairy savoir-faire was a key part of Emiliano-Romagnoli identity, as well as their link with their own territory back in Italy. In Tandil lives Héctor Cantarelli, an Italian-Argentinian who, after a long bureaucratic battle, was able to win his Italian citizenship (Canovi Reference Canovi2009, 164–7). Cantarelli keeps in his family archive a medal dating to 1955 which bears an inscription honouring his grandfather Juan, the president of La Agricola Ganadera – a cattle farming company founded in 1910 in Tandil. The inscription reads that Giovanni ‘Juan’ Cantarelli was, together with his brother Renato, the first to produce ‘el queso parmesano’.Footnote 10 Only 12 years after having sailed to Argentina from Genoa on the steamer Provence, Giovanni-Juan was able to reformulate his own appaesamento in an agrarian landscape almost identical to the one he had left in Emilia-Romagna: an irrigated lowland dotted with farmsteads and dairy-farms specialising in the production of Parmesan cheese.

In 1924, a local newspaper celebrated Giovanni's brother – Don Renato Cantarelli – as ‘the initiator of progress in Tandil’, since ‘he introduced here the dairy industry, which is the primary source of income in the region’ (Canovi Reference Canovi2009, 163). Vasco Martignoni pointed out to Canovi another key figure in the dairy industry of the Tandil region: Atilio Magnasco. ‘Magnasco – recounted Martignoni – produced wheels of cheese varying from 32 to 16 or 8 kg. Then, he also made sardo [pecorino] cheese. All kinds of hard cheese for grating’ (Canovi Reference Canovi2009, 161). What is interesting to note here is that on the other side of the ocean from Italy, all kinds of Italianness and its related landscapes and products emerged in the American melting pot of Pampa Gringa.

The socio-economic invention of the dairy industry is another common thread between the Argentinian and Italian landscape. Throughout the late nineteenth and the early twentieth century, local community dairy farms (caselli) became the symbol of modern agriculture in Emilia-Romagna, as well as an elective site for rural sociability. Around caselli, intense political and ideological conflicts arose about their transformation – or not – into co-operatives. Co-operative caselli allowed small and medium-size producers to actively participate in socio-economic processes, and in that way, caselli became a symbol of the progressive democratisation of social and economic life in the northern Italian lowlands (Anafu Reference Anafu1980). In the Argentinian pampas, peopled with Italians, it is possible to find the same trajectory, although translated into the American context, in a larger area and with a characteristic translocal mixture.

In addition to these economic similarities, what is most striking when analysing oral migration micro-histories of Emiliano-Romagnoli in the Argentinian pampas is what Sereni (Reference Sereni and Zangheri1957) defined as the reproduction of the socio-ecologic order. As Vasco Martignoni recounted to Antonio Canovi and Monica Rizzo (Canovi Reference Canovi2009, 159–62), when in 1921 his uncle Giuffrida emigrated to Argentina he had never worked as a dairyman: he learnt his craft in Argentina. Nonetheless, on his passport he is registered as a dairyman. This incongruity might appear as a simple memory fault, but what is most interesting from a memory studies perspective is the significance of the detail in Vasco's story: to Vasco, Argentina elevates migrants, it is the land of modernity and socio-economic improvement. It is there that Italian emigrants such as his uncle Giuffrida found their future.

When the Magnasco brothers first arrived in Buenos Aires from Liguria in 1855, the big wave of Italian colonisation of the pampas was yet to happen. The global movement of people corresponded to the global movement of knowledge and the establishment of the agronomical revolution in America. The consequences of the cereal production boom in North and South America first hit Europe and especially the Po Plain as a socio-economic catastrophe that pushed hundreds of thousands of peasants away from their beloved plains and right into the transforming Argentinian pampas. The changing landscape of Pampa Húmeda became a translocal hub of physically discrete environments, which coalesced and hybridised in the colonisation process that transformed Pampa Húmeda into Pampa Gringa. In America, the culture and the landscape of each European national group – and each Italian form of local regional, province, or village belonging – could be translated into specific products and practices: something that characterised the group as belonging to a specific place, but at the same time, turned the very product and its identity value into something else – a Italian-Argentinian hybrid. This is the case for cheese and the dairy production that involved Emiliano-Romagnoli in the Argentinian cuenca lechera. This twofold process of Americanisation of Italian culture and Italianisation of Argentinian elements comprise the landscape of Pampa Gringa too.

Conclusion

Every year in Cologne the Anuga (Allgemeine Nahrungs- und Genussmittel- Ausstellung), arguably the most important food trade show in the world, takes place. Among the products exhibted there is Parmigiano-Reggiano. Parmesan cheese is produced in a specific area of Emilia-Romagna, and the producers – the heirs of the old caselli – are now reunited in a consortium. Once again, in 2019, the Consorzio del Parmigiano-Reggiano denounced the presence of what they consider a poor imitation of parmesan cheese: Reggianito. Reggianito is a Spanish translation of the Italian adjective Reggiano, meaning ‘from Reggio Emilia’, and it is the name of a type of cheese produced in Argentina since the early twentieth century.Footnote 11 But as oral histories of Reggiani in Argentina reveal, Reggianito is but another product of the encounter between the landscapes of Italian migrants and Argentina.

The know-how that allowed for Reggianito to be produced in Argentina comes from people who were born into an Italian dairy plain, well before cuenca lechera was established in Argentina: the casari of the Emilia lowlands. Yet their knowledge and practices have been transmitting between the two plains for at least five generations, in a lively circulation of memories, knowledge, and people that is still ‘on the move’ even today. In an interview with Canovi, Enrica Curti remembered her life as an emigrant in Argentina. Born in Poviglio, in the lowlands of Reggio Emilia – where she still lives – she spent more than a decade in San Eduardo, in the heart of the Pampa Gringa in Santa Fe province, where her husband worked as a dairyman (Canovi Reference Canovi2009, 165). Similarly, after the disaster of the Malvinas/Falklands war in the 1980s, Fernando Víctor Juan Manfredi decided to leave his home country and the military dictatorship that ruled it for the same village of Poviglio, where he worked as a dairyman in the local casello (Canovi Reference Canovi2009, 67–70). This continuous coming-and-going between two distant countries is not the product of chance, but proof of the living connection between the two plains. There is a familiar landscape that unites the Po Plain and the Pampa Gringa: a translocal landscape that is still part of the living memory of those migrants and their descendants, and in which both Italians and Argentinians are still able to find appaesamento.

A millennia-long hydraulic culture and a broadly-shared amphibious memory combined the Po Plain and the Pampa Gringa into a common geohistorical trajectory that led Emiliano-Romagnoli migrants to Argentina. The change in geography for the Italian lowlands peasants corresponded to a promise of a new future: colonisation and the possession of land. While in Italy first the agrarian crisis and then Fascism complicated immensely every form of social mobility, in Argentina there was a time when it seemed possible for everybody, even the poorest and the most dispossessed day labourers, to turn into landowners. In the end, the American dream was not for everybody, and many Italians decided to leave the pampas for Buenos Aires, to migrate once again, or to come back to their homeland. Yet the emancipatory perspective that links the two plains still works up to present day, although now the migratory trajectory has been reversed. What makes the difference here is the process through which such a migration chain has been shaped and how it still informs the sense of belonging and appaesamento to one or more places.

Throughout Latin America, Spanish speakers normally refer to Anglo-American people, the prototype of modern colonisers, as gringos. Conversely, in the Argentinian pampas, this term ended up becoming a synonym of tano – the Italian: together with southern Brazil, this is probably the only place in which Italian migrants are considered as the bearers of European modernity. This peculiar narrative is also the product of the socio-ecological relationship that the padani established between Italy and Argentina. In Argentina, starting with Pampa Gringa, Italians became the bringers of modernity – a modernity that was elaborated through the transformation and the migration of a landscape made of place-based knowledge, socio-ecological practices, and cultural forms which are eminently Emiliano-Romagnole and padane and that also belonged to the pampa – now turned into Pampa Gringa.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Division of History of Science, Technology, and Environment at KTH, and the director of KTH-EHL, Marco Armiero. Additionally, the authors thank the Consulta degli emiliano-romagnoli nel mondo and the Provincia di Reggio Emilia who supported the research, as well as the municipalities of Castelnovo Sotto, Boretto, Brescello, Gattatico, Gualtieri, Guastalla and Poviglio. Lastly, the authors wish to thank the anonymous peer reviewers for their remarks and comments.

Notes on contributors

Daniele Valisena is a PhD in History of Science, Technology and Environment. His doctoral fellowship was part of the EU-funded Marie Sklodowska-Curie ITN ENHANCE (grant agreement 642935) in environmental humanities. His research deals with the interplay among environmental history and migration, touching upon heritage and memory studies, oral history and environmental humanities. He is one of the co-editors of the present special issue of this journal.

Antonio Canovi is a Lecturer in History and Geography at the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Italy. He has worked extensively on Italian migration history, focusing on France, Argentina, and Belgium and writing widely on oral history and memory studies. He is the Principal Investigator at Laboratorio di storia delle migrazioni at the University of Modena and Reggio.