Introduction

Does becoming a “terrorist” involve a major biographical rupture?

Total or extreme commitment is often seen as undergirding terrorist movements. It has typically been approached in terms of the risks taken by agents [McAdam, Reference McAdam1986] and the consequences of their actions for their life trajectories. The idea is that “the social identity of the players who form a social movement is transformed by their activism” [Fillieule, Agrikoliansky and Sommier Reference Fillieule, Agrikoliansky and Sommier2010: 215], and particularly by their integration into a so-called terrorist group. Contemporary understandings of radicalization cast it as a specific political bifurcation, wherein the new identity becomes difficult to reverse and challenge [see Tarragoni, Reference Tarragoni2012: 116] given the “complete” embrace of group beliefs and the identity reconfiguration.

This paradigm dominates the literature because of the acceptance of “a logic specific to clandestine life in radical institutions. This life is circumscribed, because commitment to this type of group requires a major biographical rupture that involves jettisoning previous identities in order to be literally reborn, in particular by adopting a nom de guerre, internalizing meticulously codified rules of conduct, and sometimes even resorting to mortification techniques, etc.” [Sommier, Reference Sommier2008: 92]Footnote 1. The question of identity transformation in the course of integration into armed groups is a constant, to the point that engagement has been conceived as “identification” [Hardin, Reference Hardin1995: 7]. Russell Hardin sees identification with a group as a condition for engagement in collective action, with the former presumably based on convergent interests between the individual and the group [Ibid.: 10]. Participation in the latter would benefit individual members materially (by securing a better situation if the group succeeds), symbolically, or in terms of satisfaction from participation [Ibid.: 53-54]. This logic, however, does not address how group identification occurs. It is to this question that we will devote our analysis. Our study will focus primarily on the micro-sociological level because we have explored the contexts of involvement in these groups in depth elsewhere [Guibet Lafaye, Reference Guibet Lafaye2019, Reference Guibet Lafaye2020a], as have others [see Della Porta, Reference Della Porta1995, Reference Della Porta2013; Della Porta and Rucht, Reference Della Porta, Rucht, Jenkins and Klandermans1995; Sommier, Reference Sommier2008].

In contrast to biographical-rupture and tip-over theories, we will show, from a critical perspective, that political involvement in clandestine organizations involves reconfiguring a player’s social identity, in the sense that “collective action enables the foundation, or re-foundation, of identity that will give meaning to choices and calculations” [Pizzorno, Reference Pizzorno, Crouch and Pizzorno1978; Reference Pizzorno1990: 80]. What “identity work” [Snow and McAdam, Reference Snow, McAdam and Stryker2000] underlies this reconfiguration? What are the terms of operating in violent political groups? Tackling these questions will take us away from the hypothesis that the search for material or symbolic “retribution” is the driving force of extreme political commitment, and from its interpretation as a tip-over into radicalization. We will propose a more detailed interpretation of the identity development and redefinition implied by this type of involvement. Our analysis will draw on the work of Snow and McAdam [Reference Snow, McAdam and Stryker2000] on identity transformation. This model is particularly relevant to efforts to comprehensively understand the evolution of identities within the so-called terrorist organizations of the Basque far left and national liberation, such as Iparretarrak (IK) and Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA). We will consider these identity reconfigurations from a normative rather than a utilitarian perspective; that is, we will not consider the players’ search for interests, retribution, and benefits. We will compare the interpretation of radicalism as a conversion [Strauss, Reference Strauss1959; Della Porta, Reference Della Porta1995] with the one put forth by clandestine players, who most often perceive their trajectory as a “continuation of the self”, and as a “logical” and “natural” phenomenon [Guibet Lafaye, Reference Guibet Lafaye2018].

To this end, we will start with brief overviews of the survey and of Snow and McAdam’s [Reference Snow, McAdam and Stryker2000] model. We will then consider the two major types of identity work that characterize entry into so-called terrorist far-left and national liberation organizations: “identity convergence” and “identity amplification”. We will then discuss the heuristic relevance of the notions of identity radicalization and tip over in light of these results. Finally, we will analyse the role of cognitive and affective group identification within the identity redefinition process for the individuals involved.

The survey

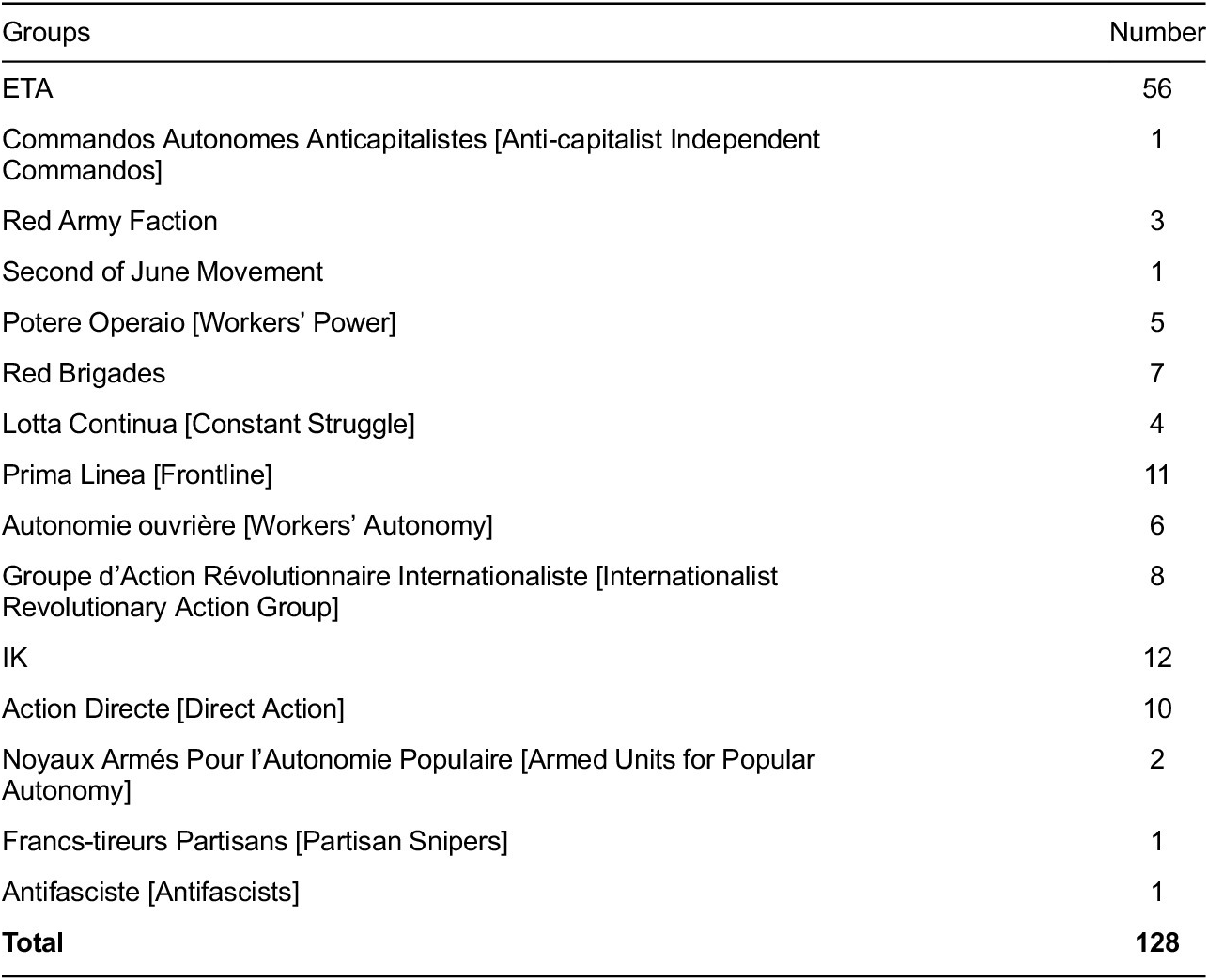

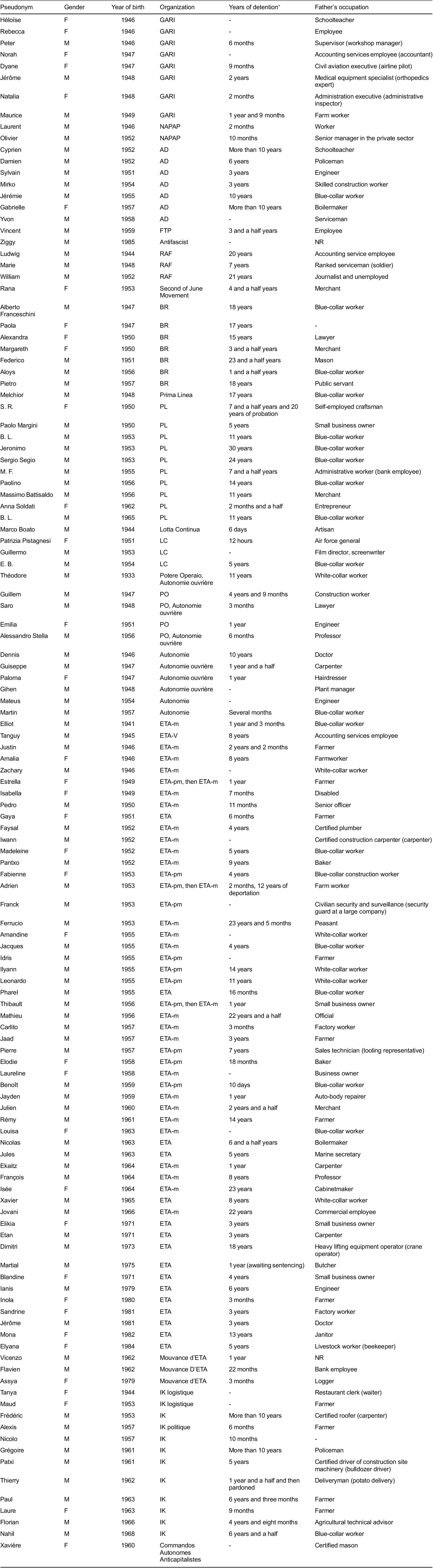

In order to understand the identity transformation related to joining a clandestine group, we conducted a series of in-depth interviews between March 2016 and July 2020, which led usFootnote 2 to meet 128 people who were active between the end of the 1960s and today. The people were contacted either directly or via the “snowball” method [Laperrière, Reference Laperrière, Poupart, Deslauriers, Groulx, Laperrière, Mayer and Pires1997]Footnote 3. Respondents included 38 women, ranging from ages 34 to 86 at the time of the interview. The interviews were recorded and fully transcribed. They lasted between 32 minutes and 4.5 hours. Appendix 1 (Table 4) presents the list of respondents and their socio-demographic characteristics, and Appendix 2 provides a brief summary of the history of illegal groups.

Table 1 Distribution of respondents by political groupFootnote 4

With the exception of the ETA, these groups were barely active beyond the late 1980s. ETA disbanded on May 3, 2018Footnote 5. Although the organizations operated in different contexts and at different times, they were all ideologically rooted in the far left or national liberation movements with strong Marxist leanings and socialist goals. They also shared the belief that reaching their respective objectives required political violence.

A brief historical overview

Beginning in 1967–1968 a revolutionary spirit swept over part of Western Europe. At the end of the 1960s, Germany was in the midst of democratic reconstruction and experiencing an identity crisis. Confronted with the silence of older generations about the Nazi past, some of young people came to question the inherited order and executive power at a time when the Vietnam War was crystallizing political opposition. The perpetuation of national socialist elites was at the heart of the protest. In France and Italy, students challenged traditional social relations, power, and political parties. As in Germany, the new generation rejected elites suspected of fascist collusion. A general strike hit France in May 1968. The Fifth Republic faltered. In Italy, strikes, demonstrations, and clashes with the police flared between 1968 and 1979. More than 50 organizations engaged in armed violence in Italy between the mid-1960s and the 1980s, including 40 far-left organizations. In these three European countries, many young people who had participated in the events of May 1968 turned to extra-parliamentary activism, or even went underground with a political objective they intended to pursue through violent means. These commitments led to identity transformations that the individuals discussed during our interviews.

“Identity work” and group adaptation methods

Retrospective research, regardless of the method of investigation used [Auriat, Reference Auriat1996], depends on the effects of memory, which are particularly pervasive and difficult to control in the case of semi-structured interviews. This method may introduce distortions, misrepresentations, and slips that are exacerbated by the fact that the interviewer has little control over the principles of episode selection [Demazière, Reference Demazière2007: 88-89]. The narrator’s account emerges from a selection of fragments – reflecting what is important to them – inserted into a story that makes sense. The semi-structured interview also runs up against the phenomenon of biographical illusion, because individuals are retracing their life story a posteriori and in a linear way [Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu1986: 69]. These forms of rationalization, and of making sense of practices, opinions, and political orientations after the fact, raise notable methodological problems [see Collovald and Gaïti, Reference Collovald, Gaïti, Collovald and Gaïti2006: 45]. The reorganized narrative, underpinned by ideological work, does not just produce a realistic description of how the individual became involved in a given organization. It also often aims to provide a rationale. Without endorsing the premise of a linear biographical development, we can nonetheless retain the notion of a “biographical arc”, that is, a set of events that can be linked to one of the forms of individual engagement [Ogien, (1989) Reference Ogien1995: 81; see also Demazière, Reference Demazière2008].

These efforts to provide meaning and perspective specific to semi-structured interviews reveal the “identity work” at play in the self-narrative. This work consists of all the discourse and practices through which individuals shape themselves [Alvesson and Willmott, Reference Alvesson and Willmott2002]. The identity appears then as the alignment of two forms of identity – personal and social – for the activist in this case. It occurs as the product of a complex “process of becoming” whereby individuals are constantly constructing, deconstructing, and reconstructing their subjectivity. The identity work thus results from a constant effort to align what individuals must be socially (social identity) and what they are privately (personal identity) [Watson, Reference Watson2008].

In contrast to a micro-sociological perspective, a meso-sociological one emphasizes five factors in individual identity development: symbols (constitutive of the activist’s identity), situational definition (through the attribution or reattribution of meaning to the social environment), roles (derived from specific values, norms, codes, and obligations), socialization (which adapts action to circumstances), and emergence of the self (influenced by context) [Arena and Arrigo, Reference Arena and Arrigo2005]. While principles, norms, values, and their evolution remain underexplored, the effects of socialization on activist choices and individual trajectories have been studied extensively [Snow, Zurcher and Ekland-Olson, Reference Snow, Zurcher and Ekland-Olson1980; Gould, Reference Gould1991; Passy, Reference Passy1998; Diani and McAdam, Reference Mario and McAdam2003; Duriez and Sawicki, Reference Duriez and Sawicki2003]. With regard to roles and socialization in armed organizations, the literature has attempted to understand group identification processes, that is, “identification with” or “subjective identification, which entails motivation” [Hardin, Reference Hardin1995]. For example, R. Hardin considers group identification to be a condition for commitment to actions with shared objectives, but he does not explore the terms or processes involved in this identification.

Secondary literature has explored identity work from a meso-sociological approach focused on the dynamics of clandestine life in small radical institutions. Commitment to these collectives is presumed necessarily to imply “a major biographical rupture that involves renouncing a previous identity” [Sommier, Reference Sommier2008: 92]. In the case of guerrilla-type armed organizations, this rupture is accompanied by a “reconstruction of the identity of the organization’s members (men and women) in line with the combatant model” [see Felices-Luna, Reference Felices-Luna2007]. Indeed, political bifurcation processes have identity implications that also raise identity dilemmas for individuals [Tarragoni, Reference Tarragoni2012: 116; Guibet Lafaye, Reference Guibet Lafaye2019]Footnote 6. Commitment to illegal and “terrorist” movements transforms agents’ social identity, as does commitment to activism in a social movement [see Fillieule, Agrikoliansky and Sommier, Reference Fillieule, Agrikoliansky and Sommier2010: 215]. The commitment correlates with a reconfiguration of the individual’s social identity, indicating that “the collective action context enables a foundation, or re-foundation, of identity that gives meaning to an individual’s choices and calculations” [Pizzorno, Reference Pizzorno, Crouch and Pizzorno1978; Reference Pizzorno1990: 80].

Identity convergence and amplification

Several models can help shed light on the identity changes experienced by the individuals we met and the terms of their involvement. D. A. Snow and D. McAdam [2000] have highlighted two forms of “identity work” that can be broken down into several subsets. These models are useful for understanding the ways in which individuals adapt to groups and the adjustments involved.

The first form, called “identity convergence” refers to the meeting between individuals with an isomorphic social identity and the collective identity of a movement [Voëgtli, Reference Voëgtli and Fillieule2010: 216]. This convergence occurs through either “identity seeking” or “identity appropriation”. In the first case, individuals seek to engage in movements with a collective identity that is congruent with their social identity, as is the case in some religious movements. Meanwhile, “identity appropriation” results from social movement entrepreneurs’ conquest of pre-existing solidarity networks, making them amenable to sharing a common identity.

Identity work can also involve identity development. In this second case, aligning social identity and collective identity requires more substantial work, ranging from a process that marginally transforms an actor’s self-conception to a radical change. In Snow and McAdam’s model [2000], identity development can result from several processes: “identity amplification”, “identity consolidation”, “identity extension”, or “identity transformation”.

The “identity amplification” process strengthens a preexisting identity that is congruent with a movement’s group identity, the former having been insufficiently strong to result in participation and activism in the past. The “identity consolidation” process refers to the coalescence of two prior personal identities previously considered incompatible. This is the case, for example, of Christian homosexual movementsFootnote 7. “Identity extension” refers to the deployment of a spiritual identity that is congruent with the identity of a movement and that encompasses practically all aspects of an individual’s life. This phenomenon is possible in religious or political groups, such as the French Communist Party [see Pudal, Reference Pudal1989; Leclercq, Reference Leclercq2008]. Finally, “identity transformation” evokes “biographical reconstruction” [Snow and Machalek, Reference Snow and Machalek1984] or “alternation” [Berger and Luckmann, (1966) Reference Berger and Luckmann1986; see 2.2 below], causing a clear break between the previous identity and that of the “convert” who has joined the movement.

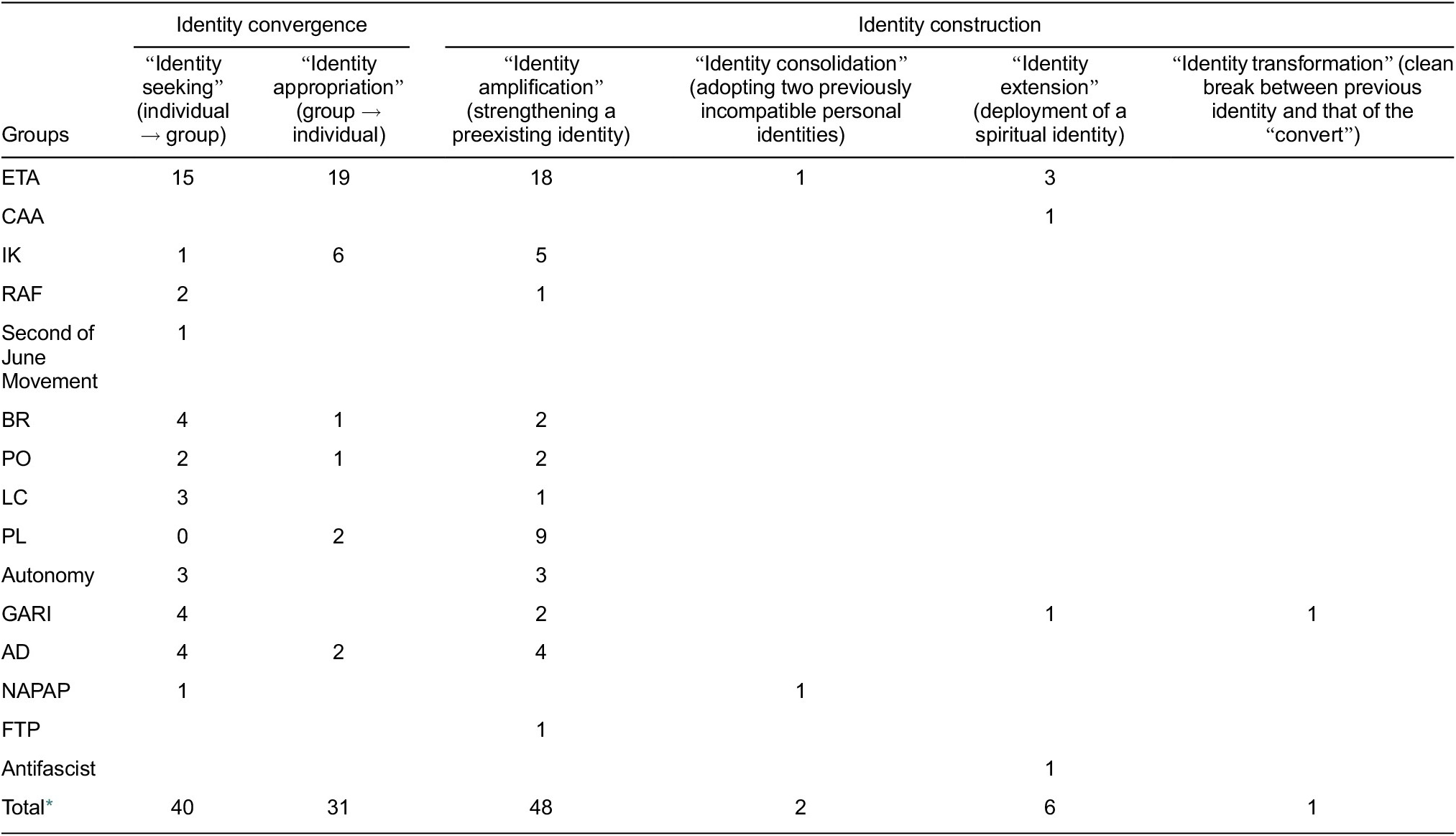

In the trajectories analysed, the most salient phenomena fall under identity convergence, broken down into identity seeking (40 cases out of 128) and identity appropriation (31 cases), on one hand, and identity amplification (48 cases) on the other (see Table 2). Identity consolidation and transformation account for 3 cases, and identity extension, for 6.

Table 2 Typology of the identity work involved in illegal trajectories

* This correction takes into account the difficulty of assigning a single category to four of the respondents.

According to the survey, identity amplification and, to a lesser extent, identity seeking, are the main categories structuring the “identity work” of activists in illegal organizations. Identity appropriation also stands out, as collectives, especially the Basque ones, sought recruits. The structure and forms of organization specific to each group (meso level) shaped their enrolment methods.

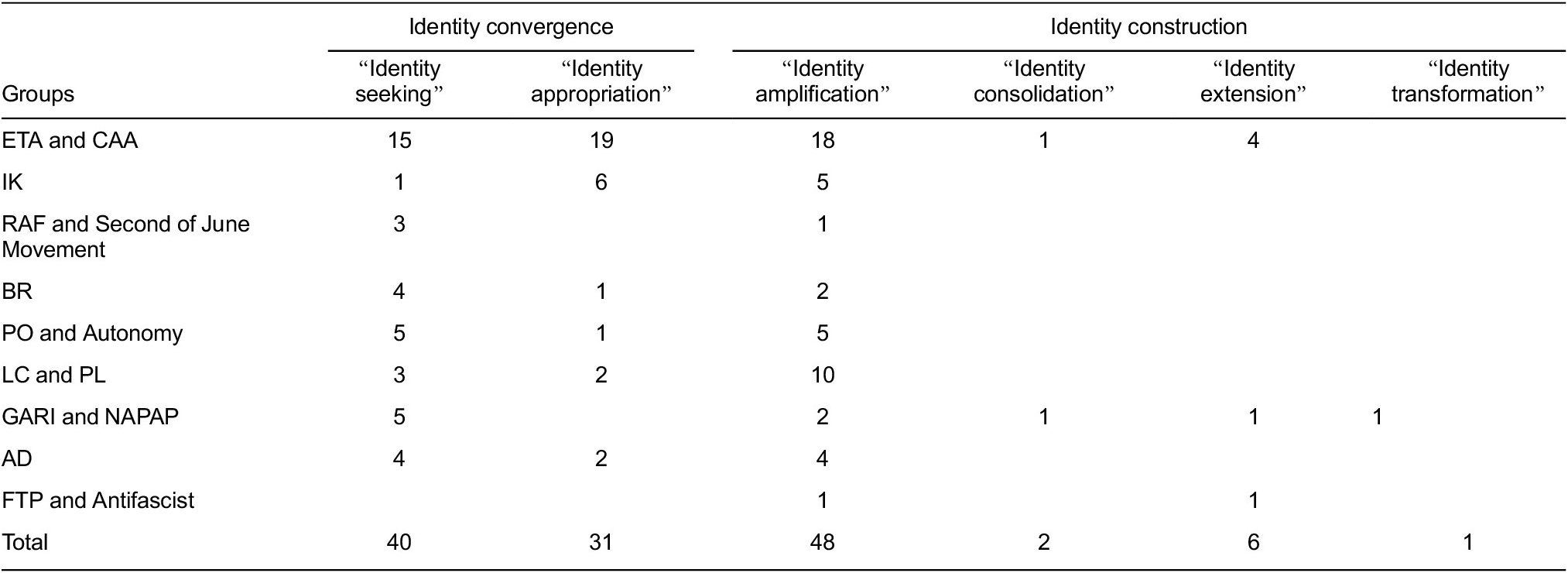

Several points are worth considering with regard to the results presented in Table 3. When individuals claimed to have intentionally sought contact with illegal groups, we placed them in the “identity-seeking” subcategory. While the number of individuals in the “identity appropriation” field is not insignificant, we did not systematically track organizations’ recruitment strategies. We took a methodologically individualistic approach that applied to a period after the individual commitments. The 31 cases were identified on the basis of personal statements, in which individuals acknowledged they were contacted by their organization. Even if this contact took place, individuals may have made the decision to engage on their own for a number of rational reasons (lack of political opportunities, desire to strengthen their commitment, possibility of benefiting from infrastructure that would allow them to achieve their goals more easily, and so on). Finally, some respondents may have omitted to mention this “identity appropriation” workFootnote 8. Admitting to having been contacted does not imply that people were forced. However, it is because the organization knew their background and anticipated they would be willing to plunge into illegality that it turned to them and offered an opportunity to join the group. In addition, groups’ recruitment patterns changed over time, especially in organizations such as ETA, which were around for half a century.

Table 3 Synthesis of identity work in the studied groups

We placed individuals under the “identity amplification” umbrella when they contextualized their political journey in terms of family background. Many respondents started their political journey when they were teenagers or very young adults. Participation in activist groups provided an opportunity to develop and fulfil a pre-existing identity that was congruent with the movement’s collective identity. The former may not have been able to develop fully beforehand because of age or lack of access to the means to authorize illegal action and so-called violent activism. This was especially the case for ETA militants who become involved through the end of the 1980s [see Guibet Lafaye, Reference Guibet Lafaye2020a].

The “identity amplification” subset also includes individuals whom the structure enabled to carry out illegal activities and deepen illegal political participation, regardless of their family background. Individuals went from being purposeful activists and determined militants to seeing their identity amplified to that of a “professional revolutionary” [Rapin, Reference Rapin, Gotovitch and Morelli2000] or even a terrorist. Finally, many of the people we met were founding members of the groups under study (GARI, AD, PO, PL, Workers’ Autonomy, FTP, IKFootnote 9). Their recruitment can therefore not be considered to have occurred via a preformed organization. The clandestine group allowed them to amplify their actions in accordance with their ideology and political ambitions. In general, entry into a clandestine group would make available superior military and logistical means. The recurrence of identity-based amplification is also attributable to the fact that most of the actors were pursuing conventional political careers before embracing armed struggle.

The collected narratives thus suggest that “identity transformation” occurred relatively infrequently in the lives of the members of clandestine far-left and national liberation organizations (see Table 2 and Table 3). This rarity is attributable to the continuity between their childhood experiences and involvement in an organization or its creation. Jacques dismissed the “identity transformation” hypothesis when he explained his objective in joining ETA:

I see an individual identity issue, that is, I think I know who I am. I recognize myself in the values of the society that I want to change, that I don’t like. And therefore I recognize myself in the somewhat humanistic or at least altruistic values of the organization, even if it is armed. When I was a teenager already—a teenager, not an adult—I used to say to myself, maybe one day I will be a militant. Maybe…

Jacques’ journey illustrates an identity convergence process giving rise to identity amplification. The recurrence of this identity work within ETA was apparent over generations. It underlies the trajectory of Jacques, born in 1955, as well as that of Ianis, born in 1979. Before joining ETA, Ianis, from a “family of militants […] involved in nationalist politics” and then in cultural movements, participated in a group promoting the Basque language. He later became a left-wing nationalist youth activistFootnote 10. When repression of young people was launched in the Southern Basque Country in the 1990s, sabotage operations were carried out around his high school. In this context, his entry into ETA is categorized as identity amplificationFootnote 11. In the case of ETA, covering 56 respondents, identity seeking, identity appropriation, and identity amplification processes all manifest themselves, in 15, 19 and 18 cases, respectively, underscoring the diversity of paths to armed activism in this group.

The most common paradigms characterizing the commitment of the actors we met are identity convergence and identity amplificationFootnote 12. Isomorphism (with regard to identity convergence) is especially applicable to the Basque case, given the strong influence of primary socialization and of the sociocultural environment [Crettiez, Reference Crettiez1997; Della Porta, Reference Della Porta2013; Guibet Lafaye, Reference Guibet Lafaye2020a]. This process notably shaped the trajectories of all the individuals involved in the logistics of organizations such as ETA (Amandine, Benoît, Elliot, Élodie, Nicolas, Vicenzo), as well as those who were in commandos, such as Ekaitz, Fabienne, and François. Thus, the Basque case is a paradigmatic example of quasi-isomorphism between the social identity of the actor and the collective identity of the movement, in this case abertzale (i.e. patriot), although not all ETA members were Basque. When asked how she became involved with the organization, Elodie explains the beginning of her support for ETA in these terms:

My father, he knew a lot of people here. In the family, all of them. One day, someone came to our house. He asked if it was my father’s house. I said yes. [He stayed.] I was still living with my parents.

Thus began Elodie’s direct support for ETA, as she gave shelter to militants in hiding.

The external perception of so-called terrorist organizations projects a normative and practicalFootnote 13 rupture onto them. Contrariwise, the organizations reject the dichotomy between conventional modes of political intervention and their own. This projection is conducive to describing entry into an armed organization as a “leap” or biographical rupture, whereas the actors’ accounts emphasize continuities. Approached comprehensively, or even immanently, this passage appears to be more akin to a linear path. Thus, Sylvain’s entry into AD occurred without any real rupture: a friend got him into it at a time when he was already “robbing banks with a moped” but “there, it was well organized, with everything that was needed: protection, drivers and everything”. Similarly, for Fabienne, who had always been an activist without being a member, the Burgos trial was the clincher: “From then on, I started to get more and more involved. There were steps”. In Paris, she encountered “other fighting nations and peoples: the Occitan and Breton”, and some Corsicans. She admits that following the executions of September 27, 1975 in the aftermath of the Burgos trial, she decided to “take up arms”. But she had already become politicized by the age of 12. Her father, of Basque-Catalan origin, anticipated her entry into ETA… Her journey, once again, reflects identity amplification.

The very small number of (N = 1) trajectories that show an “identity transformation” process involving a “biographical reconstruction” [Snow and Machalek, Reference Snow and Machalek1984], or a clear break between the previous identity and that of the “convert”, suggests the limited relevance of the tip-over thesis in elucidating the trajectories of the individuals involved in the groups under study.

Redefining identities vs alternation

As a counterpoint to these analyses based on first-hand empirical materials, the thesis of a clean break between the prior identity and that of the “convert” flourished in the 2010s [see Benslama, Reference Benslama2015; Boutih, Reference Boutih2015; Bouzar, Reference Bouzar2015]. This form of identity “redefinition” or “identity transformation” corresponds to the last column of Table 2 and Table 3, which show a very low number of occurrences (N = 1) for the political organizations studied. Given its weak heuristic relevance, the activist trajectories should not be interpreted through the prism of “identity transformation”, biographical rupture, or a tip over into radicalization, but rather by using the notion of alternation, in addition to identity convergence and amplification. Alternation refers to a set of subjective transformation(s) [Berger and Luckmann, Reference Berger and Luckmann1966; Guibet Lafaye and Rapin, Reference Guibet Lafaye and Rapin2017] occurring over the respondents’ “moral careers”. It describes a process of “near-total” transformation of subjective reality that leads individuals to “become other” as they embrace a subjective “new world” [Berger and Luckmann, (1966) Reference Berger and Luckmann1986]. Margareth’s testimony (BR) is explicit on this point. When we talk about what might have held her back or made her hesitate to commit, she admits:

There are many inner blockages, but we identify our needs as obstacles to be overcome—as counter-revolutionary elements—and we therefore think it is necessary to break these inner chains that hold us back to our previous condition. I would say that it is rather the opposite process […]. I think that all the necessary inhibitions are there to stop me. But I proceed in the exact opposite way.

This subjective transformation can go as far as redefining an identity that can be considered constitutive of total [Yon, Reference Yon2005] or radical commitment. The study of individual trajectories, based on the actors’ narratives, thus brings to light the analytical relevance of the concept of alternation, rather than radicalization or tip-over, to exploring the paths of individuals in the revolutionary left and Basque national liberation movementsFootnote 14. In the case of identity transformation, the key is not so much to observe biographical reconstruction as to uncover the mechanisms and “plausibility structure” [Berger and Luckmann, (1966) Reference Berger and Luckmann1986], in other words the representation of the world and the objective conditions that the actor faces and that enable a lasting conversion [Renou, Reference Renou, Voutat, Surdez and Voegtli2010]. The effects of Jacques’ (ETA) confrontation with repression underscore the mechanisms of this evolution:

I think that mentally I was already committed. I was not yet a member of the organization but… If I had been tortured, it would have accelerated things, but it did not lead me to question my beliefs – quite the contrary. When I saw the attitude of the Civil Guard, they could have crushed us with their feet. That humiliation you feel and all that! Of course, it made me feel better about my choice. That is to say: “Wow, this is it”. And I didn’t experience any torture at that time. But I said to myself: “Boom! It’s obvious, it’s obvious”. Franco, he was still alive.

In the late 1960s, political activists opted for the armed route. This type of “radical” commitment took root in a socio-political context of repression by the public authorities [Sommier, Reference Sommier2008]. This repression persisted in the Basque Country from the 1950s through the early 2010s [see Ianis, Elyana, and Dimitri for the ETA members), and in Italy from the late 1960s to the 1980sFootnote 15. Margareth (BR) testifies to this when reminiscing about the attack on the Agricultural Bank in Milan on December 12, 1969Footnote 16. Similarly, the words of François, who is very religious and part of the Liberation Theology movement, are unambiguous. While on a spiritual pilgrimage to El Salvador, where he met with Christian communities involved in the struggle of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) and visited the tomb of Monsignor Romero, Archbishop of San Salvador, who was assassinated by death squads during mass on March 24, 1980, he asked himself:

What do I do? Stay here and give my life to these martyred people? The answer is no: go home. Here there are thousands of people ready to die for freedom, but not at home. I decided this in 1986. I am going to take my revolutionary path to its end. I believe in Liberation Theology, so I did not experience any contradiction. Imperialism and capitalism must be fought wherever they are.

When he returned to the Basque Country, François informed ETA of the symbolic actions he had already performed. The organization later organized a meeting that would lead him to join the Nafarroa commando (Navarro). The subjective transformation and re-socialization implied by the alternation could be described as “radical”, insofar as the individual’s subjective reality was shaken. This subjective transformation nonetheless differs from the political radicalization process itself, which necessarily had to occur beforehand and at a different level in order to create an alternative “structure of plausibility” [Berger and Luckmann, (1966) Reference Berger and Luckmann1986], that is, a subjective reality different from the subject’s original one. In this case, the reality included international geopolitical developments of the 1980s and the activists in the Basque Country questioning the democratic character of the post-Franco transition in SpainFootnote 17. This new inter-subjective representation of the world, born of a political radicalization process, formed the framework within which individuals internalized the images surrounding national and social liberation, associated with the dashed hopes that the end of Francoism had elicited. This political radicalization process undoubtedly occurred in the Italian and Basque cases, although Third World and guerrilla struggles also informed the emerging organizations studied.

Group attachment and identity construction

Beyond the “plausibility structure” and the reference group, relationships with significant others must also be taken into account, on the meso- and micro-sociological levels, in the identity work that accompanies these commitments. What role does this otherness, i.e. interpersonal relations and the organizational structure, play in these actors’ identity construction? This work, like the evolution of self-conceptions, depends on acceptance by significant others. Interpersonal relationships and the networks they form are cardinal in group attachment and the development of group consciousness [Foote, Reference Foote Nelson1951]. Group identification has often been analysed using the concepts of “militant habitus” and “protest identity”. It must also be interpreted using the notion of attachment. This identification results from a process in which an individual cognitively and emotionally embraces the identity image associated with a particular role and thus wishes to practice and represent it [Goffman, Reference Goffman1961]Footnote 18. Many studies have explored cognitive and emotional investment in the development of a group identity. For example, in studying the trajectories of women in the Shining Path and the IRA, Felices-Luna notes that “interviewees who continue their involvement voluntarily describe a strong ideological conviction, envisioning their identity as a firm and reliable fighter, and feeling affection for their comrades and pride in their involvement. They thus demonstrate a strong attachment to their career and attendant identity” [Felices-Luna, Reference Felices-Luna2008: 173].

Attachment becomes a catalyst in the identity work. It contributes to the self-definition that actors achieve through the identity mobilized by activist careers (revolutionary, national liberation fighter). It translates the effects of high-risk activism at the personal and interpersonal levels. It also has moral implications stemming from moral obligation to one’s peers, and from the representation of one’s moral career in terms of the struggle to defend one’s country, language, or class struggle. Some IK activists, such as Laure, emphasize the decisive role of a sense of moral obligation:

In relation to these people who had fallen and who believed in the same thing as you, it would not honour them… to stop everything. On the contrary, they fell and they cannot have fallen for nothing – that’s not possible.

Attachment occurs through the internalization of both moral and collective norms that discourage breaking with the group [Ulmer, Reference Ulmer1994]. Indeed, entering a new peer group establishes new sociability. For example, Nicolas, who provided ETA with substantial logistical support, emphasized that, as a security measure for himself and his entourage, he had to distance himself from his friends. The relationship with other meaningful people contributes to a re-socialization of the individual, showing once again the heuristic relevance of the concept of alternation. This re-socialization assumes both an ideological and an affective adherence to a new reference group, wherein the individual’s identity experiences a reconfiguration [Melucci, Reference Melucci, Hank and Klandermans1995] and, over time, attachment. Collective identity and group identification provide emotional and cognitive stability, based on shared ideals and beliefs [Post, Reference Post M.2005]. Margareth recognizes this when she looks back on the early stages of her involvement:

In 1970, I was 20 years old, and I had attended a Catholic high school with a very closed, strict education. I arrived in Milan in 1969, and in 1970 I was already quite close to the BR. But a little by chance, I think, because of this history of friend networks. I didn’t have much political background, but I felt good with them (emphasis added).

When she talks about her decision to join the movement, Margareth mentions key encounters: “In my own birthplace, I met resistance fighters from the other side, the Reds, who welcomed me with a lot of love”. The separation from the family environment when going clandestine is sometimes experienced as a difficult moment [see GrégoireFootnote 19, FrédéricFootnote 20, Anna Soldati]. Women are more likely to mention the affective dimension, particularly in Italy and France. Group identification becomes an emotional and affective commitment, as opposed to a simple organizational partnership or membership. The notion of family is often used to describe this emotional dimension, as William suggests: “The prisoners and other RAF members […] were like a family and never were like one’s own family, which is a fortress, with which we were at odds, and which we never saw”. This interpretation is prevalent in organizations with a communal life, such as the PKK.

Roy Wallis, borrowing Weber’s term, calls holistic groups a gemeinde, that is, a community or camaraderie in which the leader and followers motivate and recognize each other through mutual love [Wallis, Reference Wallis1982: 35-36]. Affective relationships and even love become a force in groups formed around a charismatic figure, although such a figure is often absent from the collectives we studied. Group loyalties can draw on brotherly love and gain strength from the extraordinary sacrifices that terrorists are willing to make for their causes and/or the perpetuation of their groupFootnote 21.

At the meso-sociological level, socialization into the activist role and “organizational shaping” [Sawicki and Siméant, Reference Sawicki and Siméant2009: 115] use various mechanisms to promote attachment to the group and to the social movement over timeFootnote 22. These methods promote the celebration of member unity and solidarity [Fillieule, Agrikolianski and Sommier, Reference Fillieule, Agrikoliansky and Sommier2010: 217; see Lacroix, Reference Lacroix2013 for the Basque case]. At this level, networks also play an important role in individual identity work, attachment to the collective, and the development of group consciousness. The Italian, German and Basque examples attest to this. An “esprit de corps” [Blumer, Reference Blumer and Park1939] emerged, consisting of “the organizing of feelings on behalf of the movement” – in other words, in activists’ feeling “of belonging together and of being identified with one another in a common undertaking. In developing feelings of intimacy and closeness, people have the sense of sharing a common experience and of forming a select group” [Blumer, (1939) Reference Blumer and Lee1953: 205-206]. The esprit de corps unfolds across three levels: first, the development of in-group and out-group relationships; second, the existence of informal camaraderie [Turner and Killian, Reference Turner and Killian1957: 442; see Fillieule Agrikolianski and Sommier, Reference Fillieule, Agrikoliansky and Sommier2010, chap. 9]; and third, formalized ceremonial behaviours.

These ceremonial behaviours, particularly apparent in the Basque Country, constitute a means, alongside a shared ideology and common principles, of developing value adhesion and attachment to the social movement enterprise [Melucci, Reference Melucci1988]. They operate like “sensitization mechanisms” and “tools to adjust and shape the militant habitus”, and appropriate “militant memory”. They enable “experiencing, in the most personal way possible, an indignation and an anger that motivate a full commitment to action” [Traïni and Siméant, Reference Traïni, Siméant and Traïni2009: 24-25]. This is particularly observable in the prisoner release operations carried out by several of the organizations studied, such as IKFootnote 23 and RAFFootnote 24, or in retaliatory actions following the violence committed by government or paramilitary repression (such as the GALs) against organization members. More generally, these methods socialize members into the culture of the group [Fillieule, Agrikolianski and Sommier, Reference Fillieule, Agrikoliansky and Sommier2010: 218]. They contribute, at a meso-sociological level, to the construction of individual identity, in a way that is complementary to ideology, often considered as “the operator through which identification with the role of ‘professional revolutionary’ provides a total identity” [Yon, Reference Yon2005: 142].

The “esprit de corps”, nourished by these “sensitization mechanisms” and supported by a “shaping of the militant habitus”, also involves sharing and defending the same values. This axiological dimension contributes to the “identity work” and identity construction. It is especially reflected in solidarity, which constitutes the fundamental and cohesive axis of these groups, as JulienFootnote 25, MartialFootnote 26, Laureline, and Louisa underscore. For them, in “this struggle, the main thing is the solidarity we had amongst ourselves and with our people, and with other people, and the many citizens who helped us” (see also Julien)Footnote 27. This “esprit de corps” thus has ideological, affective, axiological, and normative dimensions that shape individual identity. It is a matter of embracing the same values and a common ideology, of collectively standing up to repression, of using the same interpretative schemes to think about social reality according to an “us vs them” dichotomy, and of uniting around a goal of liberation or emancipation. All of these meso-sociological factors contribute to the players’ transformation and identity work.

Conclusion

This analysis is based on retrospective life stories. “All this leads us to believe that the life history draws closer to the official presentation of the official model of the self (identity card, civil record, curriculum vitae, official biography) and to the philosophy of identity which underlies it, as one draws closer to official interrogations in official inquiries – the limit of which is the judicial inquiry or police investigation” [Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu1986: 71]. The subject and object of the biography (the investigator and the investigated) unquestionably have a common interest in accepting the premise of meaning in the life story. But to “consider life as a history, that is, as a coherent narrative of a significant and directed sequence of events, is perhaps to conform to a rhetorical illusion, to the common representation of existence that a whole literary tradition has always and still continues to reinforce” [Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu1986: 70]. These oral sources should therefore be used with caution, because they are often typical reconstructions. However, they are also the main sources we have on individual trajectories. These biographical reconstructions capture activists’ representations and perceptions of their environment (social world), their definitions of the costs and benefits of political participation, their political socialization, and the dynamics of producing and maintaining a collective identity [Della Porta Reference Della Porta2013: 28]. They also offer subjective explanations for the decision to join and remain in a radical organization. Discrediting the words of militants in the groups studied would represent a failure to appreciate the real value of the interview methodology [Horgan, Reference Horgan2011: 8].

While bearing in mind the illusion of the life story as a linear and coherent sequence, it is possible to account for the identity work involved in belonging to violent political organizations. In this regard, we highlighted the heuristic relevance of the notions of alternation and “bifurcation” – rather than “tip over” or radicalization. Alternation implies identity work, which draws mainly on forms of “identity seeking” and gives rise to “identity amplification”, which is most apparent in groups such as ETA and Prima Linea. Neither the “tip over” thesis nor the “commitment by default” paradigm [Becker Reference Becker2006] account for individual commitments in the groups studied. The trajectories of far left and Basque national liberation activists illustrate that “the capacity for existential decisions or radical choice of self always operates within the horizon of a life history, in whose traces the individual can discern who he is and who he would like to be” [Habermas (1991) Reference Habermas1992: 103].

The conscious highlighting of this continuityFootnote 28 by the actors themselves, and as attested by their trajectories, enables reconsideration of the “redefinition of identity” thesis as a transformation accompanying the alternation process. Although this continuity could be considered the product of an a posteriori reconstruction, some of the actors we met came from a communist or resistance background [see Guibet Lafaye Reference Guibet Lafaye2018, 2019]. Thus, using the “tipping point” theory and paradigm as a heuristic model to grasp the entry into radicalism or the acceleration of radicalization processes entails adopting an exclusively subjective and psychological perspective on a complex and multifactorial situation. It assumes that only the individual evolves without considering that the situation could escalate to a point where it might become intolerable not to act. In some cases, consideration of the socio-political or geopolitical context reveals that not just individuals were “tipping over” into radicalism (see Italy from the end of the 1960s through the 1980s or the Basque Country).

Our analysis diverges from the conclusions in the literature on terrorism insofar as it favours a micro-sociological rather than a meso-sociological approach. When describing these clandestine groups as holistic or “total” organizationsFootnote 29, authors are inclined to consider integration within them as a biographical rupture, and identity reconstruction as a renunciation of a previous identity. A micro-sociological perspective, however, posits continuity as the dominant dynamic. It can take the form of either “ identity seeking” which consolidates a pre-existing identity, or “identity amplification” wherein actors secure the means to achieve objectives that are congruent with those of a collective movement. Identity reconstruction inevitably occurs, but it does not involve the renunciation of a previous identity, nor necessarily a biographical rupture. Such processes reflect only “alternation”. These conclusions we established for clandestine far-left and national liberation groups are also plausible for the far rightFootnote 30, but would require empirical verification for violent political Islamic organizations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Table 4 List of respondents with their socio-demographic characteristics

Six of the respondents declined to remain anonymous, namely Marco Boato, Patrizia Pistagnesi, Paolo Margini, Sergio Segio, Alessandro Stella, and Anna Soldati. Two people agreed to have their identity revealed (Massimo Battisaldo and Alberto Franceschini). The eight therefore appear in the table under their true identity.

Appendix 2

Presentation of the organizations to which the aforementioned militants belong

Euskadi Ta Askatasuna

Basque Marxist-Leninist students founded ETA on July 31, 1959. The organization carried out its first – spectacular – attack against Luis Carrero Blanco, head of the Franco government, killed on December 20, 1973. It is also known for the explosion of a car bomb in the underground parking lot of the Hipercor shopping centre in Barcelona on June 19, 1987. ETA disbanded on May 3, 2018.

Commandos Autonomes Anticapitalistes

The Autonomous Anti-Capitalist Commandos (CAA) were created in the Basque Country in 1976. Their conception of struggle consists of providing support to worker and popular movements. On February 23, 1984, the CAA executed Enrique Casas Vila, a socialist senator, a candidate in the Guipuzcoa elections, and a key figure in the coordination of Antiterrorist Liberation Groups (GAL). The commando that carried out the attack took refuge in the Northern Basque Country and was ambushed on March 22, 1984 in Pasajes, where four of its members were killed. This liquidation marked the end of the Autonomous Commandos.

Iparretarrak

Iparretarrak (IK) includes activists from the Northern Basque Country who decided to pursue their struggle independently of the one that ETA conducted in the South. IK was founded on December 11, 1973, when it took action against a company that refused to allow its employees to unionize. Actions continued after the arrest of Philippe Bidart, a leading figure in the organization, on February 20, 1988. IK’s last claimed attack occurred in April 2000.

Red Army Faction

The birth of the RAF is usually linked to the “liberation” of Andreas Baader on May 14, 1970 by a commando led by Ulrike Meinhof. Several generations followed one another within the RAF before it dissolved by publishing a statement on April 20, 1998, entitled: “Why we are stopping”. The RAF notably attacked the German embassy in Stockholm via the Holger Meins commando on April 24, 1975, executed the prosecutor Buback on April 7, 1977 via the Ulrich Meinhof commando, and kidnapped and then murdered the “boss of bosses” Hanns-Martin Schleyer on September 5, 1977, via the Siegfried Hausner commando.

Second of June Movement

The somewhat anarchist “Second of June Movement” (Bewegung 2. Juni) was close to the RAF. The group’s main action was the kidnapping on February 27, 1975 of Peter Lorenz, a CDU candidate for Berlin mayor, in order to free comrades and political prisoners. The group dissolved in 1980.

Potere Operaio

Potere Operaio (Workers’ Power, PO) embodied Italy’s “operaist” elevation of the worker as fundamental to socio-political struggles. This movement started in the 1960s, via magazines such as Quaderni Rossi and Quaderni Piacentini. PO was created in 1969. Its most famous leaders were Antonio Negri, Oreste Scalzone, and Franco Piperno. The group dissolved in the spring of 1973.

Autonomie ouvrière

In the mid-1970s, a series of regional groups with various acronyms (Comitati Autonomi, Collettivi Politici, Comitati Comunisti, etc.) and changing names, banded together to form a movement called Autonomia Operaia. Its militants partly came from PO, and partly from Lotta Continua (LC) and were mostly new and often young activists.

Lotta Continua

The “operaist” LC emerged from the worker and student movement. It was active mainly between 1974 and 1976 and was responsible for the execution of the commissioner Luigi Calabresi by one of its commandos on May 17, 1972. In 1976, LC joined the “Proletarian Democracy” coalition to take part in the general elections, but did not achieve any real success. This result, among other things, led to the dissolution of LC.

Prima Linea

PL was founded in April 1977 as the result of a split within the Comitati Comunisti per il Potere Operaio (CCPO), after repression affected some of its members. PL’s first action was an intrusion on Fiat headquarters on November 29, 1976. The organization executed policemen, judges, judicial “collaborators”, factory managers, and university professors. At the end of the 1970s, PL experienced repression. Some militants sought to leave the organization, which dissolved in April 1981.

Red Brigades

The Red Brigades (BR) emerged in the context of the workers’ and students’ revolts in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The group’s first action was to set fire to a car belonging to a Siemens executive on September 17, 1970Footnote 31. The BR are best known for kidnapping the Christian Democracy (DC) leader Aldo Moro, who was executed on May 9, 1978, after 55 days of detention. The last action claimed by a BR group was the execution of Massimo D’Antona, advisor to the Minister of Labor, on May 20, 1999, by a BR-PCC commando.

Internationalist Revolutionary Action Group

The Internationalist Revolutionary Action Group(s) (GARI) formed in March 1974 after the Franco regime sentenced to death Puig Antich, a militant in the Iberian Liberation Movement (M.I.L.), and convicted four other M.I.L. members. In order to influence the fate of these prisoners, the group kidnapped the banker Angel Baltasar Suarez on May 3, 1974. More than a structured organization, GARI coordinates anarchist groups operating on an affinity basis.

Noyaux Armés Pour l’Autonomie Populaire

The Noyaux Armés Pour l’Autonomie Populaire (NAPAP) were formed at the end of 1976 from the International Brigades. They were joined by members of Vaincre et vivreFootnote 32, former militants from the Gauche Prolétarienne (GP), and people active within the independence movement. On March 23, 1977, they claimed responsibility for the assassination of Jean-Antoine Tramoni, who on February 25, 1972 had killed Pierre Overney, a worker at Renault. The group dissolved in the summer of 1977. Some former NAPAP members joined the Coordination Autonome and then Action Directe.

Action Directe

Action Directe (AD) claimed its first action on May 1, 1979, when it machine-gunned the façade of the Conseil National du Patronat Français (CNPF) in Paris. Two of the most striking actions carried out by the internationalist core of AD were the execution of General Audran, director of international affairs at the Ministry of Defence, on January 25, 1985, and of Georges Besse, CEO of Renault, on November 17, 1986. On February 21, 1987, Joëlle Aubron, Georges Cipriani, Nathalie Ménigon, and Jean-Marc Rouillan were arrested. The latter believes that AD ended with his release on parole on May 18, 2018 (La Dépêche, 26/02/2018).

Francs-tireurs Partisans

The Francs-tireurs Partisans (FTP) are a small clandestine organization that started on July 14, 1991 with a Molotov cocktail attack on the headquarters of the Front National (FN) in Marseille. All the group’s actions targeted structures and had antifascist objectives. Following the death of Ibrahim AliFootnote 33 in February 1995, FTP pursued two operations on FN buildings, on February 21, 1996, and on June 9, 1998.