Federal Indian law is the body of law that defines the rights, responsibilities, and relationships between three sovereigns, Tribes, states, and the federal government.Reference Fletcher1 This area of law has defined, oftentimes poorly, the contours of treaty rights,2 criminalReference Newton3 and civil4 jurisdiction, economic development,5 among other issues. Much has been documented in terms of the implications of social, legal, political, and economic systems that perpetuate inequities amongst American Indian and Alaska Native populations.Reference Dreveskracht, Hilleary and Clarren6 There has also been substantial research on health inequalities.7 American Indians and Alaska Natives experience lower life expectancy, higher rates of unintentional injuries, heart disease, suicide and other conditions.8 Yet, there has been less discussion on the role of law in perpetuating these adverse health outcomes in these populations.Reference Hoss9

The social and structural determinants of health are the factors and conditions, such as housing, education, and politics, that create health disparities.10 For years, law has been described as a tool to promote healthReference Moulton, Goodman, Parmet and Goodman11 and even a determinant of health.Reference Burris, Regenstein, Trott, Williamson, Theiss and Dingake12 And while research has explored Tribal health laws and federal Indian health policies,Reference Hoss13 more needs to be analyzed in terms of the role of foundational principles of federal Indian law in perpetuating health disparities.

This article argues that federal Indian law is a structural determinant of health by linking health disparities to the constructs of this body of law. First, this article briefly discusses the literature on the legal determinants of health. Second, it outlines foundational principles of federal Indian law and then links these principles to health disparities in the third section. This article concludes by advocating for an analysis of the principles of federal Indian law in the study of Tribal public health. Because the “Indian” is the term utilized under federal law to describe American Indians and Alaska Natives, I use this term to describe federal Indian laws and policies.

Law as a Social and Structural Determinant of Health

The social determinants of health refer to employment, income, housing, education and other conditions that determine inequitable health outcomes.14 These socioeconomic factors are the leading drivers of health disparities, even when compared to clinical interventions and health communications.Reference Frieden15 For example, life expectancy is lower amongst people with lower incomeReference Chetty16 and less education.Reference Hummer and Hernandez17 Structural determinants of health are social systems that create these inequities such as political, economic, and legal.18 As an example here, government investment in education leads to improved high school graduation rates.Reference Johnson and Tanner19

Much public health law scholarship has focused on how law can be used as a tool to promote positive health outcomes.20 Leveraging on this body of literature, researchers have also framed law as a determinant of health or as a tool to address the social and structural determinants of health.Reference Gostin and Burris21 Just this year, the Lancet Commission on Law and Global Health published a report entitled “The Legal Determinants of Health: Harnessing the Power of Law for Global Health and Sustainable Development.”22 The report reaffirms the role of law has in promoting health but highlights how underutilized it is.23 Importantly, it also acknowledges how ineffective, stigmatizing, and discriminatory laws can perpetuate the social determinants of health.24 Professor Burris argues that public health law research can be used as a to study, promote, or mitigate the role of law in addressing the social determinants of health.25 By acknowledging that law can be ineffective, discriminatory and whose effects should be mitigated, this literature recognizes that law can have both positive and negative impacts on health.

This scholarship largely discusses laws related to health or the social determinants on their face, such as vaccination, injury prevention, education,26 or legal systems to be used for health promotion.27 The foundations of federal Indian law, however, deal with a variety of issues including criminal and civil jurisdiction, rights to practice cultural practices, and hunting and fishing rights.28 Although these laws do not contemplate health, such unjust laws can still create adverse health outcomes.

This article argues that federal Indian law is a structural determinant of health by linking health disparities to the constructs of this body of law.

Some scholars consider law and policies as social determinants of health, rather than structural, because of laws are socially constructed.29 For the purposes of this article, law will be referred to as a structural determinant of health. This is done so in order to distinguish between social indicators, such as housing and income, and the structural systems, such as law and policy, that create these indicators. Referring to law as a structural determinant also allows for a bridge between the health determinants literature and that of structural violence, the harm created by normalized social structures created by law, politics, and economics that disadvantage certain populations, discussed below.Reference Winter, Leighton, Christie, Wagner and Winter30

Principles of Federal Indian Law

Tribal nations have existed throughout what is now the continental United States and Alaska since time immemorial.Reference Pevar31 Colonization and genocide diminished both the number of Tribes in existence and the total indigenous population.Reference Dunbar-Ortiz32 Upon its creation, the United States utilized unique policies to manage the federal-Tribal government relationships, sometimes to assimilate the Tribes, sometimes to terminate them, and, more recently increased efforts to support their sovereign rights.Reference Miller33 Throughout this history, law was often the tool used to perpetuate these policies.34

The foundational legal principles developed throughout this history still apply today.35 Although not exhaustive, this section describes some of these principles of federal Indian law. It is essential to note that these principles originate under federal law and may not necessarily reflect an indigenous or Tribal framework. Tribal law, the laws of individual Tribes whether codes, case law, constitutions, or customary law,36 is outside the scope of this paper but is discussed in other writing.37 Similarly, state law can have a role on Tribal health but is also outside the scope of this paper. This is because federal law provides the authority and framework for state laws related to Tribes.

Tribal Sovereignty and Recognition

Tribal sovereignty refers to the right of Tribes “to make their own laws and be ruled by them.”38 It is “plenary and exclusive power over their members and their territory.”Reference Cohen39 Because Tribes existed long before the colonial or federal governments, this sovereignty is not based on any federal law but instead is an inherent authority of a sovereign government.40 As sovereigns, Tribes operate distinct governments with their own agencies and laws based on their unique histories and cultures.41 Exercising political sovereignty allows Tribes to protect their cultural sovereignty.Reference Coffey and Tsosie42

Although federal law is not the source of Tribal sovereignty, it does recognize this sovereignty.43 And it is federal law that dictates which Tribal nations are federally recognized and thus have a government-to-government relationship with the United States.44 Today, Tribes receive varied legal recognition from the US. Federally recognized Indian tribes are those that have been officially recognized by the federal government through treaties, executive order, legislation or administrative action.45 There are, however, Tribes that have not received federal recognition. Some of these Tribes have received state recognition,46 such as the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina.47 Some Tribes have not received any recognition or have had their recognition terminated.48 There are 573 federally-recognized Tribes.49

The federal recognition process, in choosing to recognize some Tribes but not all, has health consequences. Without recognition, these Tribes are unable to access a variety of services and programming including health care and education. Without recognition, Tribes can lack the jurisdiction to effectively protect their people, lands, and cultures from encroachment from other governments.

Indian Identity and Citizenship

Generally, there are three ways in which a person can be identified as an Indian, the legal term used to refer to indigenous people of what is now the United States: personal, Tribal, and federal. First, one can be an Indian through self-identification. The United States Census, for example, measures the Indian population through self-identification.50 Second, an individual can be an Indian if she is a member of a Tribe. Each tribe has the authority to establish membership rules.51

Federal law also defines who are considered “Indians” based on various statutory structures, case law, and regulations. For example, under the Indian Child Welfare Act, an “Indian child” is any unmarried child under age eighteen who is a member of a federally recognized Indian tribe or is the biological child of a current tribal member and is eligible for membership.52 The Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act defines “Indian” as any member of an Indian tribe.53 In other statutes, such as the Indian Trade and Intercourse Act or the Major Crimes Act, Congress did not define “Indian,” leaving federal courts or administrative agencies to establish the definition based on a variety of factors including Tribal membership and ties to a Tribe.54 These classifications have great impact on the health of American Indians and Alaska Natives. Federal laws defining Indians can limit access to health services and other programming as well as protections outlined under the law.

Indians can be citizens of three sovereigns. Indians with Tribal membership are citizens of their Tribe. Indians are also citizens of the United State by birth.55 Finally, Indians are often citizens of the state in which they reside.56 As citizens of each government, Indians can access health services afforded by each government. Urban Indians is a term that describes those Indians who live off reservations in urban areas. For many urban Indians, the impetus to move to the cities included World War II and the relocation programs promoted by the federal government between 1953-1972.Reference Trombino57 While federal law does provide health services to Urban Indians through health centers, Urban Indian facilities are also underfunded with great variability in terms of the services provided across the programs.58

Doctrine of Discovery and Indian Title

The doctrine of discovery is the legal principle relied upon justifying the colonization of indigenous land.59 Supreme Court case law states that “[i]t is supposed to be a principle of universal law, that, if an uninhabited country be discovered by a number of individuals, who acknowledge no connection with, and owe no allegiance to, any government whatever, the country becomes the property of the discoverers.”60 Further, according to federal law, if the land was not already “discovered” by a Christian government then the European colonizers discovered it regardless if it was already inhabited by Tribes.61 Because of this, Tribes do not have fee title to the lands in which they have occupied since time immemorial.62 Rather, since European discovery, “Indian Title” consists of the right to use and occupy the land, but not the ability to convey the land.63

Based on these doctrines, Tribal lands64 are held in trust by the federal government.65 And, it is the federal government's responsibility to ensure that this land is protected for the benefit of Tribes and American Indians.66

Domestic Dependent Nations and Plenary Power

Federal Indian law distinguishes Tribes from foreign states and instead categorizes them as “domestic dependent nations.”67 The Supreme Court describes the relationship between domestic dependent nations and the federal government as one between a guardian and a ward.68 Part of the federal government's guardian role involves protecting Tribal sovereignty from state infringement by asserting state authority on Tribal lands.69

In addition to its role as a “guardian” of Tribal sovereignty against state infringement, the Supreme Court held that Congress has plenary power to legislate regarding all matters concerning Indians.70 This principle establishes the federal government's authority over Tribes.71 Federal plenary power can preempt nearly all Tribal authority or right, even those guaranteed by treaty.72 However, federal legislation must be specifically authorized by Congress.73 Until Congressional authorization, Tribal law remains governing law.

Plenary power was challenged to the Supreme Court in Lone Wolf.74 The Court ruled that it did not have the authority to challenge Congress's authority over Tribes; it is a political question in which the judiciary cannot inquire.75 Congress's plenary power cannot be reviewed within the court system, foreclosing the opportunity to challenge federal legislation under this basis.76

Trust Responsibility

Under federal law, the United States maintains a trust responsibility towards Tribes because of its role in “the destruction of Indian civilization.”77 This trust responsibility is based on history, treaties, agreements, and legislation.78 The trust responsibility is a “fiduciary obligation … to protect tribal treaty rights, lands, assets, and resources, as well as a duty to carry out the mandates of federal Indian law.”79 One component of the trust responsibility is Tribal consultation, a requirement for federal agencies to consult with Tribes prior to taking action that would impact Tribal communities.80 Many have argued that tribal consultation has not been an effective means of communicating81 and that “many Indians today are reluctant to place faith in, and rely on, the doctrine of trust responsibility.”82 In the health context, the trust responsibility has been violated in the consistent underfunding of Indian health care servicesReference Piland and Berger83 and the failure to consult with Tribes on federal Indian health policies such as Medicaid work requirements.Reference Diamond84

Jurisdiction

Tribes have authority over their lands and their people. In practice, despite relatively straightforward principles — that states do not have authority on Tribal lands and federal preemption of Tribal authority must be done through explicit Congressional authorization, the application of these principles across federal courts have been more complex. Federal Indian law establishes to main categories of jurisdiction: criminal and civil. Criminal jurisdiction can rest with Tribes, the federal government, or with states when authorized by federal law.85 Factors in determining which government has criminal jurisdiction include the crime, the identity of the accused, the identity of the victim, the location of the crime, and the federal statutory and case law.86

Civil jurisdiction is largely based on the Montana test, which outlines instances in which Tribes can extend jurisdictional authority over non-members.87 This test maintains that Tribes retain their inherent civil regulatory authority over non-members on fee lands within reservations over individuals who enter consensual relationships with the Tribe or its members, through commercial dealing, contracts, leases, or other arrangements.88 Tribes also retain this authority if the conduct in questions threatens or has some direct effect on the political integrity, the economic security, or the health or welfare of the Tribe.89 State authority on Tribal lands includes an inquiry regarding state, Tribal and federal interests and an analysis on federal and Tribal laws that might preempt state jurisdiction. Failures of the jurisdictional scheme outlined under federal Indian law that lead to adverse health outcomes are plentiful. Federal law has limited Tribal criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians that has led to an epidemic of violence against Native women.Reference Deer and Deer90 Federal law has also limited Tribal authority over non-Indians in instances of land use and environmental protection91 — tools that can be used to promote public health.

Federal Indian Law as a Structural Determinant of Health

The application of the principles of federal Indian law described above has resulted in the undermining of Tribal political and cultural sovereignty. This has included terminating Tribal recognition,92 denying Tribal rights to ancestral lands,93 denying rights to engaging in cultural practices,Reference Fletcher94 preventing access to sacred lands and waters,95 prohibiting Tribal authority over non-members in land use situations,96 prohibiting Tribal resolutions to criminal violations committed by Indians on Indian land,97 and prohibiting Tribal governments from prosecuting non-Indians who commit crimes on Indian land.98 Additionally, “Indians, more than any other ethnic group, are subject to extensive legal regulation of their rights.”Reference Getches99 This is only a snapshot of the adverse impacts of federal Indian law on Tribes and American Indian and Alaska Native. Figure 1 outlines both the principle of federal Indian law and the adverse outcomes related to the doctrine.

The application of the principles of federal Indian law has resulted in the undermining of Tribal political and cultural sovereignty. This has included terminating Tribal recognition, denying Tribal rights to ancestral lands, denying rights to engaging in cultural practices, preventing access to sacred lands and waters, prohibiting Tribal authority over non-members in land use situations, prohibiting Tribal resolutions to criminal violations committed by Indians on Indian land, and prohibiting Tribal governments from prosecuting non-Indians who commit crimes on Indian land.

Figure 1 Adverse Outcomes of Federal Indian Law

As argued previously, the adverse outcomes stemming from federal Indian law perpetuate structural violence.100 Structural violence is “invisible, embedded in ubiquitous social structures, normalized by stable institutions and regular experience” and “occurs whenever people are disadvantaged by political, legal, economic or cultural traditions.”101 Federal Indian law has normalized a Tribe's inability to assert jurisdiction over crimes committed against its members by a non-Indian. It has normalized a Tribe's inability to assert utilize land use mechanisms over non-member land within the boundaries of the reservation.

Federal Indian law has also resulted in historical trauma, “the collective emotional and psychological injury both over the life span and across generations resulting from the history of difficulties that Indians as a group have experienced in America.”Reference Halpern, Heart and DeBruyn102 Contributors of historical trauma include assimilation policies and programs that separated American Indians and Alaska Natives from their families and Tribes and denying access to sacred lands and cultural practices.103 All of these were facilitated by federal Indian law.

Historical trauma has been linked to a variety of health disparities including depression, suicide, anxiety, disordered eating, commercial tobacco use, lack of contraception use,Reference Gone, Hartmann, Pomerville, Wendt, Klem and Burrage104 and substance use disorder.Reference Braveheart, Skewes and Blume105 The American Psychological Association has explored the intersection of historical trauma and Adverse Childhood Experiences, arguing that the former contributes to the later.Reference BigFoot, Lamb and Delmar106 Historical trauma manifests in the form of intimate partner violence and incarceration, both of which are studied under the ACEs framework.107 As Mehrsa Baradaran put eloquently in the context of the historical treatment of blacks in the United States: “Past injustices breed present suffering.”Reference Baradaran108 This also rings true in the context of American Indians and Alaska Natives.

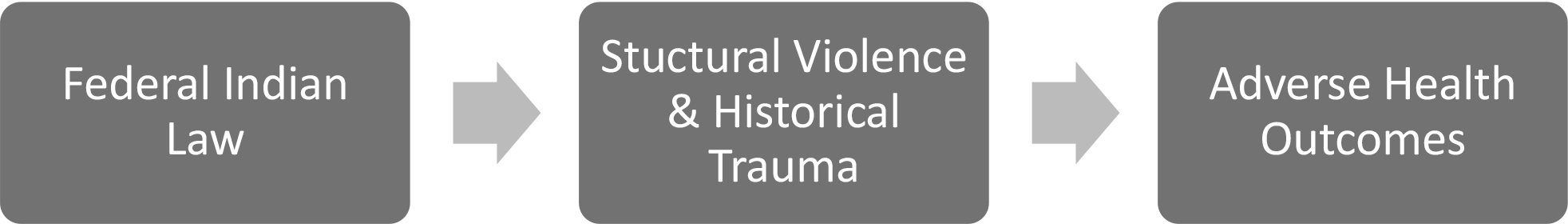

And so, there is a link between the principles of federal Indian law, the structural violence and historical trauma it creates, and the subsequent adverse health outcomes. Figure 2 maps this relationship in a logic model. Federal Indian law, both in its principles and application, has limited Tribal authority and sovereignty. This has led to historical trauma as is also a form of structural violence, created when unjust systems have been normalized under the law. Numerous studies have found relationships between the outcomes of federal Indian law and the historical trauma created by federal Indian law to lead to adverse health outcomes.

Figure 2 Logic Model Linking Federal Indian Law to Adverse Health Outcomes

Certainly, not every federal law has had an adverse impact on Tribal sovereignty. Since the start of the Self-Determination policy era, many federal laws have sought to promote Tribal self-government. In fact, these laws would never have passed without the advocacy of Tribes, Tribal-serving organizations, and Indian activists.

For example, the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 allowed the direct funding of Tribes to administer their own health services as an alternative to accessing chronically under-funded services through the federal Indian Health Service.109 These Tribally administered health programs have been remarkably successful. The following year, Congress passed the Indian Health Care Improvement Act which sought to improve current health services offered by the federal government, increase services available to urban Indians, and to promote the education and retention of health professionals to work in Indian communities.110

As another example, the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 was passed in order to curb the intentional and systematic removal of Indian children away from their parents, families, and Tribes in state family law proceedings.111 ICWA provides Tribes a right to intervene in custody and adoption proceedings involving Indian children and establishes requirements for state child service agencies to consider placement of Indian children with Tribal families.112 ICWA as stemmed some of the removal of Indian children away from Tribal communities.113

The legal authority for these impactful and effective laws is based on the faulty constructs of federal Indian law. As visualized by Figure 3, without plenary power, Congress would not have the authority to pass these laws in the first place. And, it was federal Indian law, through the underfunding of Tribal health services and Tribal governments, that created the crises in Tribal health and Indian children that led to the necessity of passing these laws. All of federal Indian law is a product of federal law, undermining Tribal authority to make their own laws.

Figure 3 Foundations of Effective Federal Indian Policies

This brings us to our determinants of health framework. Responding to health inequalities experiences by American Indians and Alaska Natives requires more that addressing the social determinants of health. It also necessitates responding to the structural determinants of health. Namely, federal Indian law. effective public health responses must study, analyze, and incorporate mechanisms in which to erode the principles of federal Indian law and its adverse health impacts.

Conclusion

Professor Maggie Blackhawk recently stated in a New York Times op-ed that that the United States has “not yet fully dismantled the legal infrastructure that permitted abuse of Native Americans.”Reference Blackhawk114 The infrastructure she refers to is the plenary power doctrine, and she eloquently argues that the Supreme Court should overturn it as it has no place within current federal law and government.115 In this article, I argue that federal Indian law is the cause of a variety of adverse health outcomes due to its perpetuating structural violence and historical trauma and is thus a structural determinants of health.

Professor Blackhawk's proposal would be a leap towards mitigating the harmful impacts of federal Indian law in the context of structural violence and adverse health outcomes. Until this point, it is imperative that within the faulty constructs of federal Indian law, Tribal sovereignty is protected and promoted as the primary mechanism to promote the health and welfare of Tribes and American Indians and Alaska Native people.116 Public health advocates and researchers must also include foundational principles of federal Indian law in their study of health disparities so that effective legal tools are developed to promote Tribal public health.