Over the last 15 years, several excavations have uncovered evidence of the Roman army in northeast Hispania during the 2nd and 1st c. BCE. New data from castra, frequently set near the coast, and from strategic outposts connected to the main roads reveal the army's interest in controlling the territory and its indigenous communities.Footnote 1 This network included praesidia, garrisons stationed at indigenous oppida, in a system that is well known from the sources (e.g., Liv. 21.61, 28.34, 28.42.3; Plut. Vit. Sert. 6–7). From them, the army was deployed during conflicts, especially the Sertorian and Civil Wars.Footnote 2 I will suggest that a significant part of the army in northeast Hispania was settled as garrisons inside key indigenous sites, some of them oppida, others road stations, to control the most important roads, territories, and resources. In peacetime, these garrisons must have been limited in size and their troops would mostly have overseen trade, taxation, and the exploitation of the main resources: metals, salt, grain, and livestock. The sites often display material culture and structures similar to traditional Late Iberian examples, but in some cases Roman outposts have been confidently identified. They first appear in the middle of the 2nd c. and remain occupied until the second quarter of the 1st c. BCE. Roman militaria and the use of Roman systems of measurement, architectural practices, materials, and techniques (tegulae, opus signinum, or a high level of metallurgy) signal the presence of the army and local auxilia, despite the fact that many of these sites lacked walls or defensive structures.

Other than that conducted by J. Alonso and E. Ble,Footnote 3 little research has been devoted to objects from such sites that are connected to writing, making inventories or registries, and seal use: wax tablets, styli in bronze or bone, spatulae for working the wax, seal-boxes, and seal-rings, whether the sites were occupied by the Roman army, Iberian communities, or both. Such objects indicate that the diffusion of writing and the use of seals occurred very early on, possibly in connection with an official mail service and with a system of registering and inventorying resources of the provincial administration, but also because of the diffusion of new commercial and economic management customs. The wide distribution of these instrumenta scriptoria in civilian and military contexts challenges the traditional view of a limited diffusion of literacy and writing among the indigenous communities and the local population. I intend to analyze the presence of such writing materials as a reflection of the process of integration into the Roman world, and to assess its historical, cultural, and economic aspects.

The objects

Recent typologies have focused mostly on objects from the early Empire onwards, there being few published parallels from the mid-2nd to mid-1st c. BCE. I will therefore use those typologies for my framework.Footnote 4

Instrumenta scriptoria are not always easily identified in the archaeological record and often not properly published: bone styli are frequently confused with hair needles or spindles,Footnote 5 bone seal-boxes are sometimes broken and fragmented,Footnote 6 wax-smoothing spatulae are rare (and therefore often unidentified), and tabulae (wood tablets) are usually not preserved in Mediterranean lands,Footnote 7 while seal-rings, especially the actual gemstones, are not considered part of the writing apparatus.Footnote 8 At the same time, not all bone-needle fragments are styli and not all rings are signet rings. Nonetheless, a large number of writing instruments have been found at Late Republican sites, often not only within the same area but also in close association. This is especially true of seal-rings, usually considered an object of luxury and personal adornment, but which in a military context should be considered a means of identification and authentication.Footnote 9 The case of seal-boxes is particularly complex. Seal-boxes were used to protect single seals from damage. They were containers for wax imprints used to seal a range of items, especially written documents. Seal-boxes were small (they range in size from 2 to 5 cm) and hinged, with two main parts: a lid and a base. The base always has between three and five circular perforations, and the lid is usually decorated. The basic shapes are circular, piriform, square, and lozenge-shaped, but it is difficult to identify them if they are not complete.

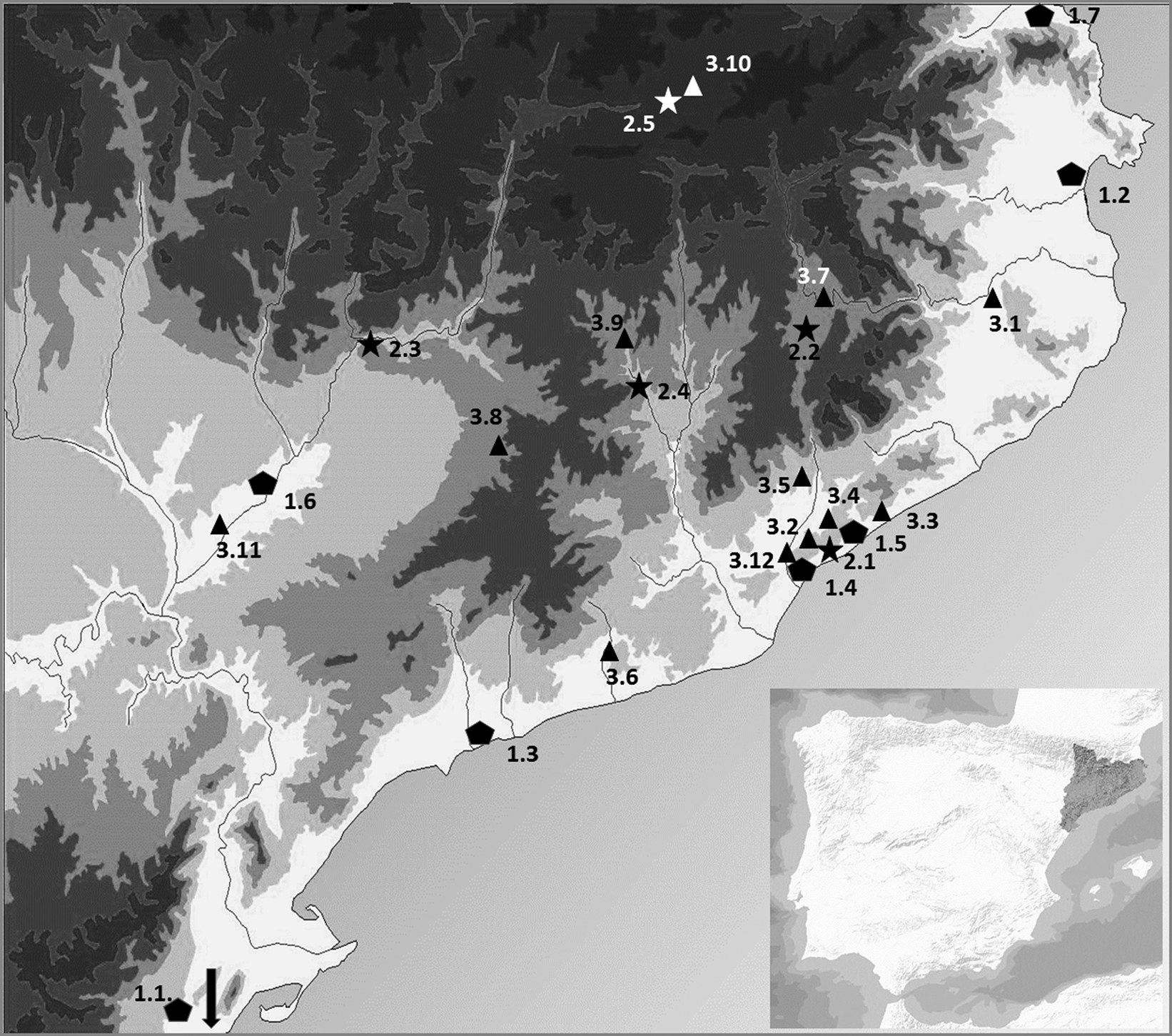

The objects discussed in this article are arranged according to their findspots in Roman cities, military outposts, and Iberian oppida (Fig. 1). The inventory (see Supplementary Table 1) provides references to drawings or published images, archaeological context, chronology, and typological classification.

Fig. 1. Map of sites mentioned: ![]() cities

cities ![]() Roman outposts

Roman outposts ![]() Iberian hill forts. (Map by O. Olesti.)

Iberian hill forts. (Map by O. Olesti.)

1.1 Valentia (off the map to the south). 1.2 Emporion. 1.3. Tarraco. 1.4 Baetulo. 1.5 Iluro. 1.6 Ilerda. 1.7 Ruscino. 2.1 Cabrera de Mar. 2.2 Camp de les Lloses. 2.3 Monteró. 2.4 Cardona. 2.5 Tossal de Baltarga. 3.1 St. Julià de Ramis. 3.2 Burriac. 3.3 Torre dels Encantats. 3.4 Turó del Vent. 3.5 Torre Roja. 3.6 Olèrdola. 3.7 L'Esquerda. 3.8 Prats del Rei (Sikarra). 3.9 St. Miquel de Sorba. 3.10 Castellot de Bolvir. 3.11 Gebut (Soses). 3.12 Puig Castellar de Sta. Coloma. 3.13 Torre de la Sal (Cabanes, Castelló) (off the map to the south).

Cities

Valentia

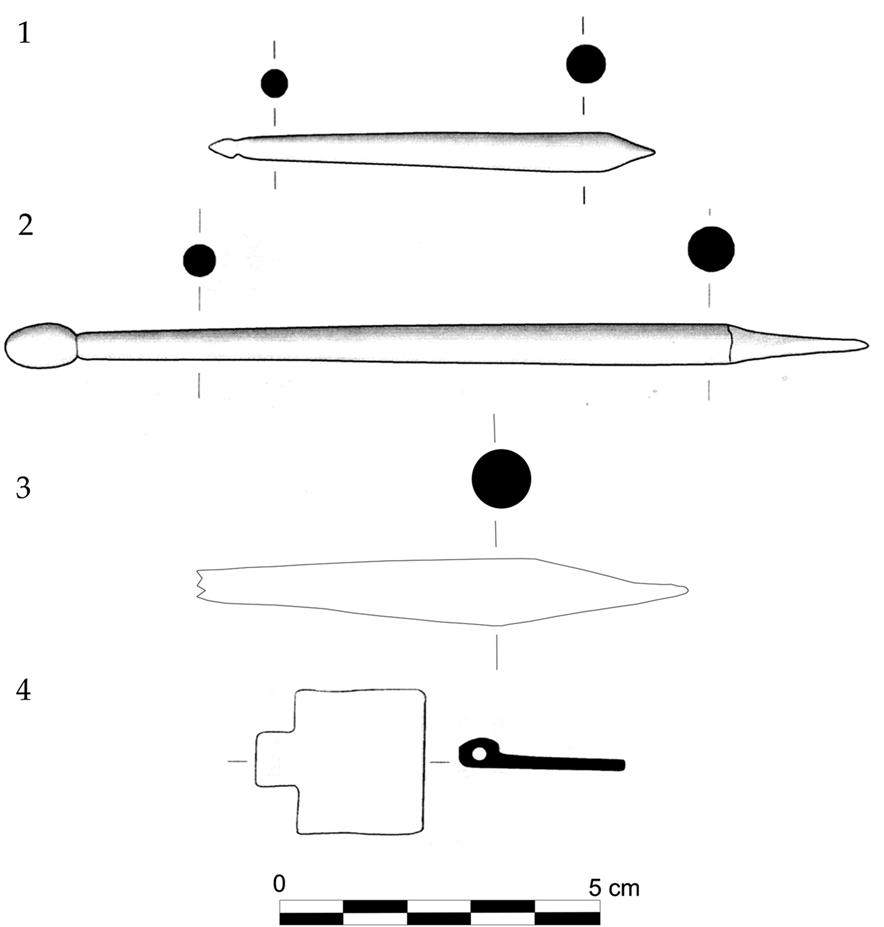

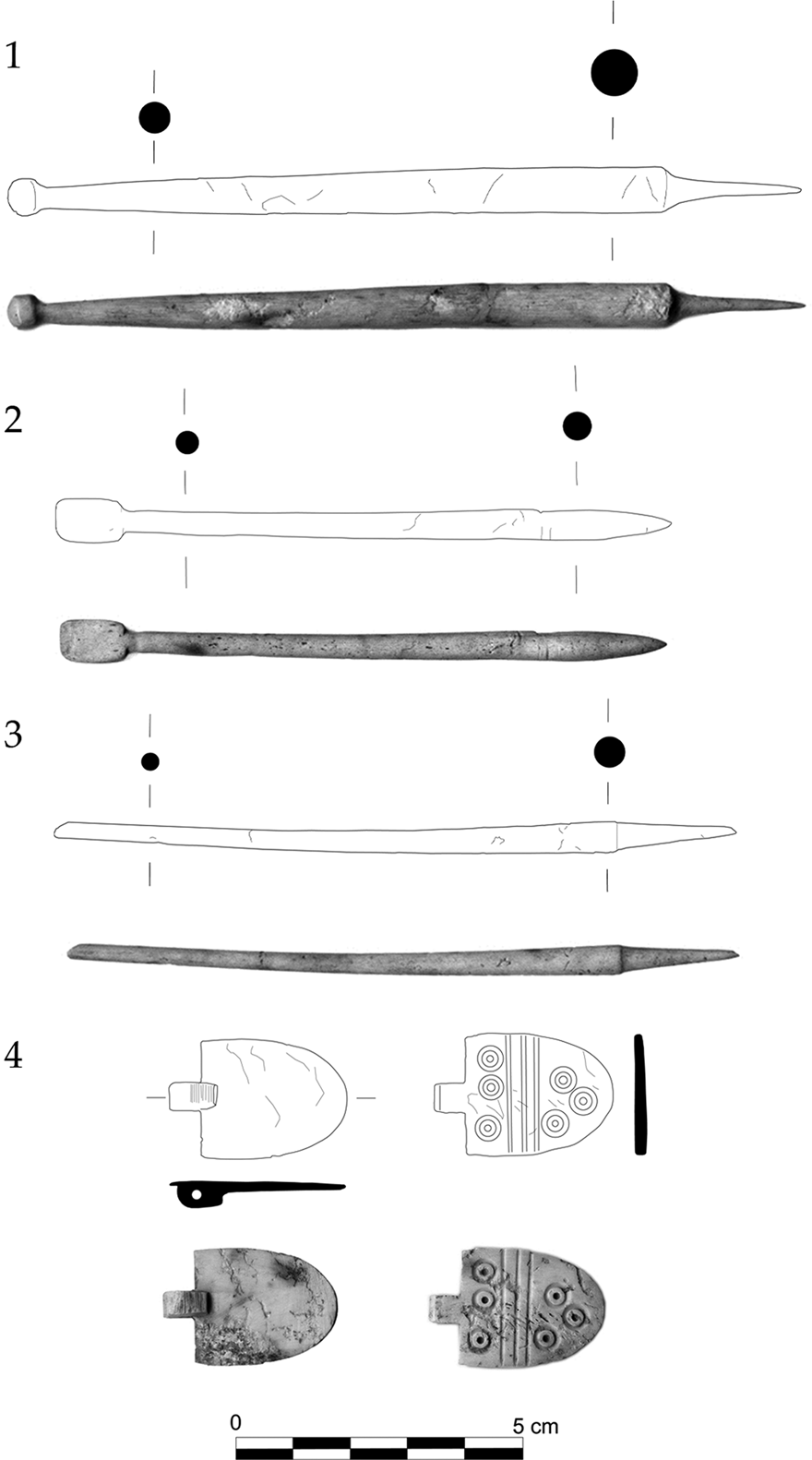

Although Valentia (which was perhaps a Latin colony) falls outside our study area, it is of interest. Near the tabernae at the forum were found the remains of 14 skeletons who have been interpreted as executed members of the Sertorian garrison that protected the city when Pompey's army attacked in 75 BCE. Three were found together, separate from the rest, on the pavement of the porticus: two males of ca. 20 years and one of ca. 40 years, are thought to have been the commander with two officers.Footnote 10 The destruction levels of the forum yielded three iron signet rings, one bronze ring, five styli (Fig. 2.1–3), one cover of a bone seal-box, and one possible inkwell.Footnote 11 Two styli were found in the horreum nearby; the bronze ring and one stylus were found near the three skeletons; two signet rings (one with a glass cameo) were found on their amputated left hands, while the other signet ring and seal-box cover (Fig. 2.4) were found on the floor of the porticus.Footnote 12 It might be significant that the equipment of military scribae was present during the final moments of the city when the last of the garrison were being executed.

Fig. 2. Writing utensils from Valentia. (Drawings by O. Olesti.)

Emporion

The Greek city of Emporion (1.2 on Fig. 1) was controlled by Rome from 218 BCE. In the first half of the 2nd c. BCE a castrum or castra hiberna was set up. Several bone styli from the 2nd/1st c. BCE were found,Footnote 13 as well as nine seal-boxes,Footnote 14 but their exact findspots were not recorded. Our research has further identified the bronze cover of a seal-box bearing the name Sepullius and an image of Mercury and the caduceus,Footnote 15 as well as two Late Republican lead seals with the names of Philo() M(arci) s(ervus) and Sus(as) Sex(ti) s(ervus), probably acting on behalf of their owner (IRC V, 152–53). Their presence is probably related to either the military occupation or to the fact that Emporion had an important harbor and was the regional capital.

Grave 23 in the indigenous ‘Bonjoan’ necropolis, a cremation from the Augustan period, yielded a seal-ring, showing its use by the Iberian population.Footnote 16 In grave 24 of the ‘Les Corts’ necropolis, also considered indigenous but, as attested by the presence of weapons, probably linked to auxilia, a token or sigillum similar to an unpublished one from Son Espases (Mallorca), was found bearing the inscription COR, probably for Cor(nelius).

Tarraco (Tarragona)

In the excavations (1926–29) of the 2nd-c. BCE levels of the city's forum (1.3 on Fig. 1), 13 bone styli and the bronze cover of a semi-oval seal-box were found in the area of the Late Republican basilica.Footnote 17

Baetulo (Badalona)

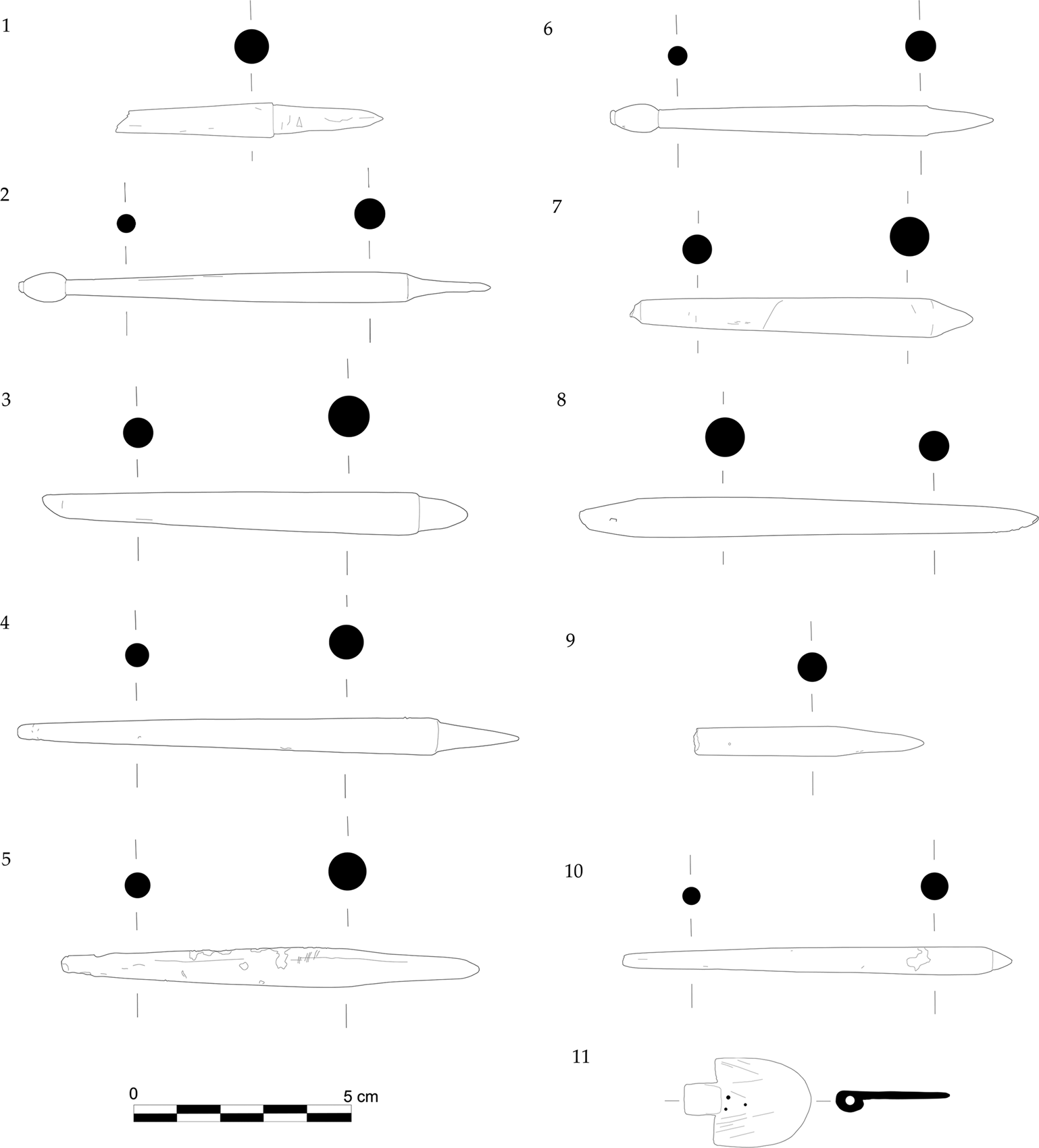

At this Late Republican foundation (c. 70 BCE; 1.4 on Fig. 1), 10 bone styli from the 1st c. BCE (Fig. 3.1–10), as well as the cover of a bone seal-box lacking holes, similar to the one from Valentia (Fig. 3.11), were found in excavations in different parts of the city.Footnote 18

Fig. 3. Writing utensils from Baetulo. (Drawings by O. Olesti.)

Iluro (Mataró)

At Iluro (1.5 on Fig. 1), another Late Republican foundation (c. 70 BCE) on the coast of Catalunya, a group of seven bronze seal-boxes was uncovered in 2002 in a domestic context at Carrer de Na Pau dating to ca. 50–25 BCE. Several undated bone styli were also found.Footnote 19

Ilerda (Lleida)

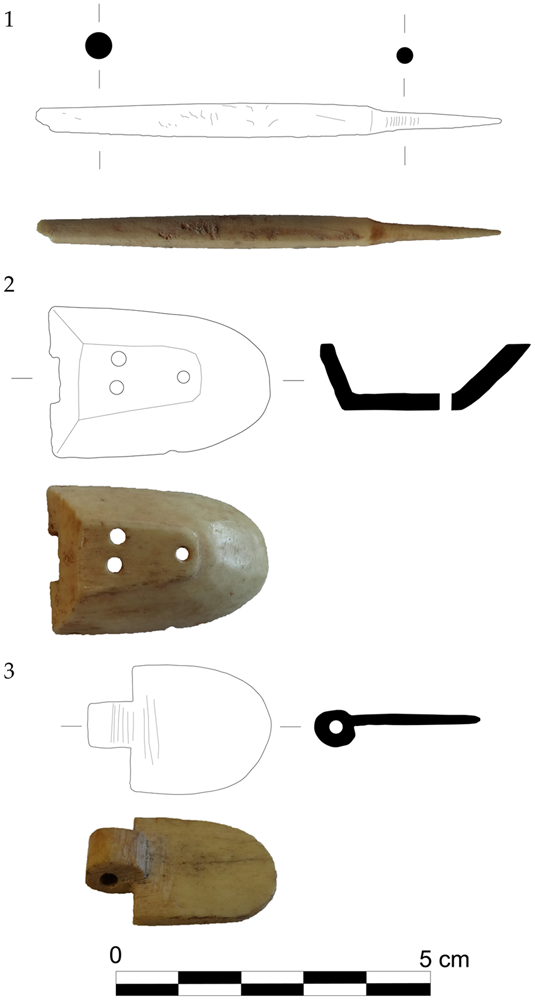

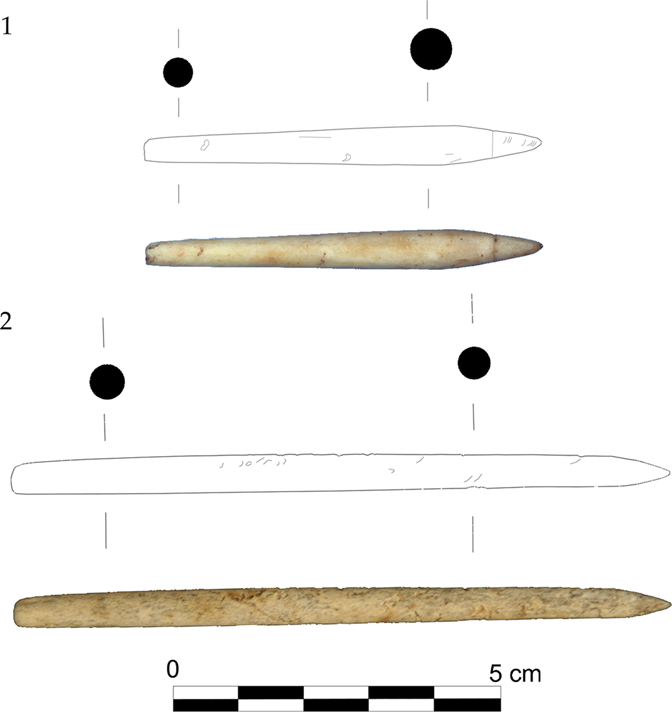

At the Iberian oppidum on the hill ‘Turó de la Seu’ (1.6 on Fig. 1), a series of rooms was built into the southeast slope in the first half of the 1st c. BCE. Here V. Sabaté recently found a bone stylus (Fig. 4.1) and two covers of bone seal-boxes (Fig. 4.2–3).Footnote 20 The hill fort was abandoned in the mid-1st c. BCE.

Fig. 4. Writing utensils from Ilerda. (Drawings by O. Olesti. Photos courtesy V. Sabater.)

Probably at the same time, a new urban center was founded further down the hillside. In this area (La Paeria), a magnificent intaglio seal made in the 2nd c. BCE, engraved with Hercules carrying a bow and arrows, was found in an Augustan context.Footnote 21 An unprovenanced bone stylus might date to the Late Republican period.

Ruscino (Perpignan)

Controlled by Rome from the beginning of the 2nd c. BCE, it is probable that at least before 125 BCE this Iberian oppidum (1.7 on Fig. 1) belonged to Hispania Citerior. It received Latin rights under Caesar in either 49 or 45 BCE, when it was probably promoted to a colony.Footnote 22 Three bone styli were found: one in a grain storage pit (silo) of the middle of the 2nd c. BCE and two in a silo dating to the end of that century. These grain storage pits were the traditional way of storing cereals in the Iberian world. Since I. Rebé has pointed out that all graffiti from 2nd-c. BCE Ruscino are in Iberian, we may suppose that these styli were used to write in the Iberian script.Footnote 23

It is not surprising to discover styli and seal-boxes in urban contexts where interactions between local and Italic populations must have been commonplace. Nearly all were harbor cities, places where the exchange of products occurred on a frequent basis, and places where Roman garrison troops were stationed. It is striking that styli are present in cities where the indigenous element was dominant, such as Ruscino or Ilerda, but many of these were key locations for the provincial administration.

Army Outposts

In recent years, scholars have identified more and more sites as “outposts of integration.”Footnote 24 They include different categories of settlements, such as castella and roadside centers, where the army was stationed but with many different functions (e.g., military logistics, territorial control, taxation, road supervision).

Ca l'Arnau (Cabrera de Mar)

On the coast beneath the Iberian hill fort of Burriac, this proto-urban center flourished between the 2nd c. and 80–70 BCE (2.1 on Fig. 1). It presents multiple signs of Roman military presence, such as militaria, imported goods, and a Campanian-style bath. Several domus show correlations with Roman and south Italian traditions.Footnote 25 The more than 50 graffiti from the site, however, are all in Iberian. They include a personal name inscribed post cocturam on one of the architectural terracottas in the dome of the baths.Footnote 26 Two bone styli were found in the abandonment layers of c. 80 BCE; two possible fragments of others are being studied (Fig. 5.1–2).Footnote 27

Fig. 5. Writing utensils from Cabrera de Mar. (Drawings by O. Olesti. Photos courtesy A. G. Sinner.)

As is common at logistics sites, there were signs of metallurgical activity, mostly iron-working, and several lead weights. Alongside its probable function as the winter quarters of a coastal garrison, there is evidence for the production and repair of weapons, purchase and storage of supplies, and minting of bronze coins.

Camp de les Lloses (Tona)

A cluster of three Italian-style atrium houses, dated between 125 and 75 BCE, lies at a natural crossroads between the interior and the central Catalunyan coast (2.2. on Fig. 1).Footnote 28 Militaria (including military tokensFootnote 29), a complete ludus latrunculorum (board game with tokens), a small altar, a simpulum, and a bronze chandelier confirm a military presence alongside the local population attested by Iberian graffiti, handmade pottery, spindle whorls, and, especially, infant burials inside the houses, a well-documented Iberian funerary practice but one that was rare among Italians.Footnote 30 A fragment of a Late Republican funerary monument, probably of a commander,Footnote 31 and an Iberian warrior's funerary stele,Footnote 32 probably for an auxiliary soldier, were discovered at a distance of 6 km from the site.

In ‘Building B’, which housed a lararium and a small altar, a bone stylus, a complete bone seal-box, and the hinges of a tabula were found in the same room.Footnote 33 Other finds from the house include an iron spatulaFootnote 34 and two iron seal-rings, one of which was gilded and engraved with a human figure.Footnote 35 A jar set on top of a large piece of iron slag in a ritual deposit in an adjacent buildingFootnote 36 should perhaps be interpreted as an inkwell, completing an array of writing utensils in a limited area.

Iron-, bronze- and lead-working are documented. Scales, weights in lead and bronze, and perhaps coin productionFootnote 37 point to this settlement being an economic and trade center on a main road used to supply the army.Footnote 38

Monteró (Camarassa)

This strategically located castellum on top of a hill (2.3 on Fig. 1) controls the River Segre, which descends from the Pyrenees. A first cluster of structures, to the west, consists of a set of rooms arranged in an L-shape, some with elaborate pavements in opus signinum and remains of wall-paintings. The second cluster contains one building and the remains of a perimeter wall which could have functioned as a rampart.Footnote 39 Weapons, imported pottery (e.g., Italian amphoras and cookware), weights, and gaming pieces imply a Roman military context, while three lead tablets with Iberian texts indicate the presence of auxilia. The documents have been dated to the 2nd c. BCE and interpreted as either a list or a request,Footnote 40 indicating some kind of registration activity. Several styli were also found.Footnote 41

Cardona, ‘El camp de futbol’

A group of storage and domestic spaces belonging to a rural settlement (2.4 on Fig. 1), thought to have been a statio that was active between c. 150 and 75 BCE and that controlled access to the rock-salt mines of Cardona, was excavated in 2015.Footnote 42 There are no indications of ramparts or a defensive system, but only about 1000 m2 of the site has been uncovered. There are at least four buildings, one of which covers an area of 100 m2 and has been identified as a warehouse. Most of the fineware and imported tableware was found in the warehouse, while amphoras and kitchenware were found in the three buildings of the east sector. A foundation deposit was discovered in a pit under the pavement of the warehouse, containing a ritual jar with talus bones, a marble token, three bone styli (Fig. 6.1–3), and the cover of a bone seal-box (Fig. 6.4). This is probably one of the best archaeological examples of finding seal-boxes and styli together. In other rooms, a glass intaglio from a seal-ring, engraved with a deity, and lead weights were found. Of two graffiti, one is in Latin, reading ]amios (possibly for Paramios, either a freedman or a slave, given the Greek name), and another is in Iberian, reading Ti.Footnote 43

Fig. 6. Writing utensils from Cardona. (Drawings by O. Olesti. Photos courtesy A. Pancorbo.)

It is significant that the offering of what could be described as a scriba's “desktop set” was made inside the warehouse, at a statio at the entrance of the rock-salt mines that managed their exploitation and trade, under the control of the provincial administration. The scriba was probably a stationarius.Footnote 44

Tossal de Baltarga (Bellver de Cerdanya)

On top of a hill overlooking one of the most important trans-Pyrenean routes (2.5 on Fig. 1), a propugnaculum or turris (6 m2) was erected during the 2nd half of the 2nd c. BCE, replacing an earlier Iberian site from the 4th/3rd c. This settlement contained several associated buildings, one of which was probably a storehouse.Footnote 45 Roman militaria, such as clavi caligae (hobnails from soldiers’ shoes) and six glandae (sling bullets), indicate that the site was used by the army, while the presence of a local population is documented through, e.g., the handmade pottery (80% of the total), querns, and spindle whorls. The most striking finds have been four signacula, of which three were discovered during the excavations (in different buildings) (Fig. 7.1–4): a gilded bronze ring with a glass gem engraved with probably a female goddess;Footnote 46 a silver ring engraved with an image of an advancing winged male, perhaps Mercury, holding a javelin or caduceus; a gilded iron ring (70% silver, 30% gold) very similar to the Roman rings found in the battlefield at Baecula (206 BCE); and an iron ring bearing a gemstone skillfully engraved with Achilles and Penthesileia. Gilded signacula imply the presence of Roman officers at the site;Footnote 47 to have four at a site of limited dimensions and another one at El Castellot, c. 7 km away, is striking. The evidence of an indigenous population might be linked to auxilia, given the site's defensive role.

Fig. 7. Seal-rings from Tossal de Baltarga. (Photos and drawings by O. Olesti.)

Iberian Hill Forts

This study has also identified writing instruments at indigenous sites, mostly oppida, of the 2nd/1st c. BCE.Footnote 48 These sites never attained the status of Roman city but remained peregrinae. In contrast to Emporion, Tarraco, and Ruscino, most of them were abandoned during the 1st c. BCE and new – Roman – foundations were established within their vicinity (between 4 and 10 km away). While it is possible that garrisons, praesidia, or hiberna were established at these sites, the presence of writing utensils could equally be explained by the diffusion of writing habits among indigenous communities.

Sant Julià DE Ramis (Girona)

This 3-ha oppidum of the Indigetes dating back to the 6th c. BCE was transformed during the second half of the 2nd c. BCE with a new street grid, city wall, and defenses (3.1 on Fig. 1). A camp with more than 100 silos was established close by at Bosc del Congost. At the top of the oppidum, a Roman-style monument was erected, possibly a temple. The new defensive system, which included a gate in polygonal masonry and a polygonal tower, was planned using Roman units of measurement (with multiples of 4 and 10 Roman feet).Footnote 49 The gate and several stretches of pavement have been excavated; a bone stylus was found inside the gate's guardhouse.Footnote 50

Burriac (Cabrera de Mar, Maresme)

This 4th-c. BCE fortified oppidum of 9 ha was the main city of the Laietani (3.2 on Fig. 1). During the 2nd half of the 2nd c. BCE, a new gate in opus quadratum was inserted in the city wall, and the urban plan was transformed with new buildings in Roman units of measurement, most of them houses with a silo inside, and sewers. Inside one of the biggest buildings – a warehouse measuring 40 × 13 Roman feet which contained the base of a wine press and 17 dolia – a (now lost) silver stylus with a zoomorphic figure-shaped end, perhaps a dolphin, was found together with the remains of a linden-wood tabula.Footnote 51 ‘Room III’ yielded a bronze cover of a seal-box near a group of six lead weights.Footnote 52 Two bronze styli were excavated by the Late Republican gate (1st half of the 1st c. BCE).Footnote 53 The oppidum was abandoned between 80 and 50 BCE.

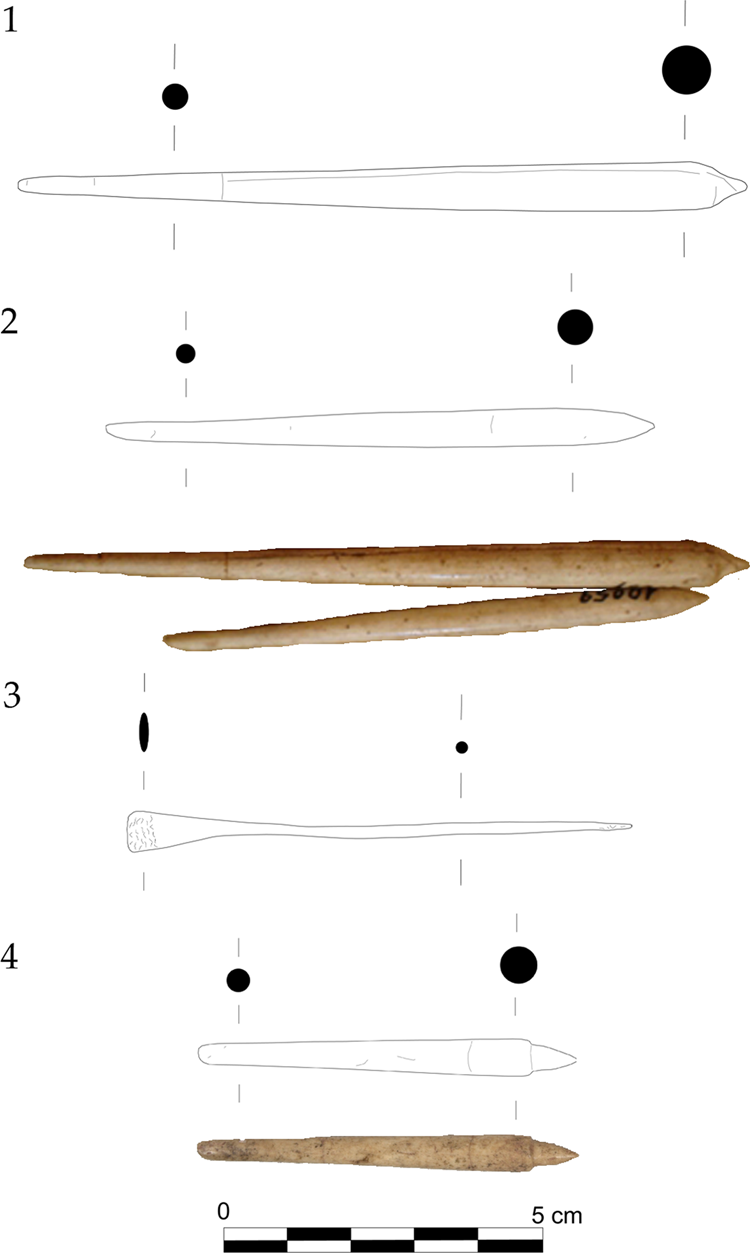

Torre dels Encantats (Arenys, Maresme)

This coastal oppidum 15 km north of Burriac was founded in the 4th c. BCE and occupied until the mid-1st c. BCE (3.3 on Fig. 1). The main excavations date from the 1950s and 1960s.Footnote 54 In layers dated to the 2nd/1st c., two bone styli (Fig. 8.1–2), a possible bronze calamus,Footnote 55 and a pondus stamped with a seal-ring depicting a geometric drawing were found.Footnote 56 It is not usual to mark pondera in this way, but it has been documented at other Iberian sites under Roman controlFootnote 57 and could indicate the use of seals to mark and differentiate products and activities (in this case, pondera or textile production), implying a system of recording local output. Several Iberian graffiti were also found, as well as one in Latin (MAR) on a piece of Black Gloss pottery, probably an abbreviated name indicating ownership.Footnote 58

Fig. 8. Writing utensils from Torre dels Encantats, Turó del Vent and Torre Roja. (Drawings by O. Olesti. Photos courtesy Museu d'Arenys de Mar.)

Turó del Vent (Llinars, Vallès Oriental)

Located on top of a coastal mountain range, this minor Laietanian oppidum from the beginning of the 4th c. BCE was partially destroyed during the Second Punic War (3.4 on Fig. 1). It contained a large number of grain silos and a fortified horreum inside its walls. Excavations uncovered Roman, Iberian and Celtiberian weapons, as well as tegulae, imbrices, and a bronze stylus (Fig. 8.3) from the 2nd c. BCE.Footnote 59 Despite this Roman military presence, there are also traces of an indigenous population.Footnote 60

Torre Roja (Caldes de Montbui)

This Iron-Age oppidum (3.5 on Fig. 1), like many others, was nearly depopulated during the 2nd c. BCE with the Roman offensive, but was reoccupied and transformed at the beginning of the 1st c. BCE.Footnote 61 New buildings and houses were constructed in an indigenous tradition, but Roman techniques were also incorporated, e.g., the organization of the houses around an open courtyard and the use of tegulae and imbrices. Traces of iron production were found, including a reduction kiln.Footnote 62 Inside one of several large warehouses with dolia and a possible wine press, a bone stylus was found (Fig. 8.4)Footnote 63 in a clearly indigenous context dated to the 1st half of the 1st c. BCE, with handmade pottery, Iberian graffiti, and domestic inhumation of perinatals.

Olèrdola

Olèrdola (3.6 on Fig. 1) was initially a secondary hill fort, ca. 50 km north of Tarraco, controlling the road (the future Via Augusta) that crossed the east of the peninsula from north to south. At the end of the 2nd c. BCE, the oppidum was significantly restructured, with the construction of a 148-m-long wall using Roman units of measurement (decempeda), a watchtower, and a large cistern.Footnote 64 Its gate was fortified with two towers in polygonal masonry with bossage. The archaeologists believed the site to be a castellum, occupied by a Roman garrison, probably a cavalry unit (because of the presence of, e.g., spurs and horse harnesses),Footnote 65 although others have interpreted it as an example of hospitium militare.Footnote 66 The site was abandoned ca. 30 BCE. Two bone styli and two bone spatulae from early 1st-c. contexts were found close to the gate, in association with lead weights and plumb bobs.Footnote 67 A Late Republican silver Roman seal-ring, found in a medieval layer, carries the Latin inscription Atius / Fel(ix).Footnote 68 These names most probably refer to a freedman of the gens Atia, an important family in Hispania during Caesar's Civil War.Footnote 69

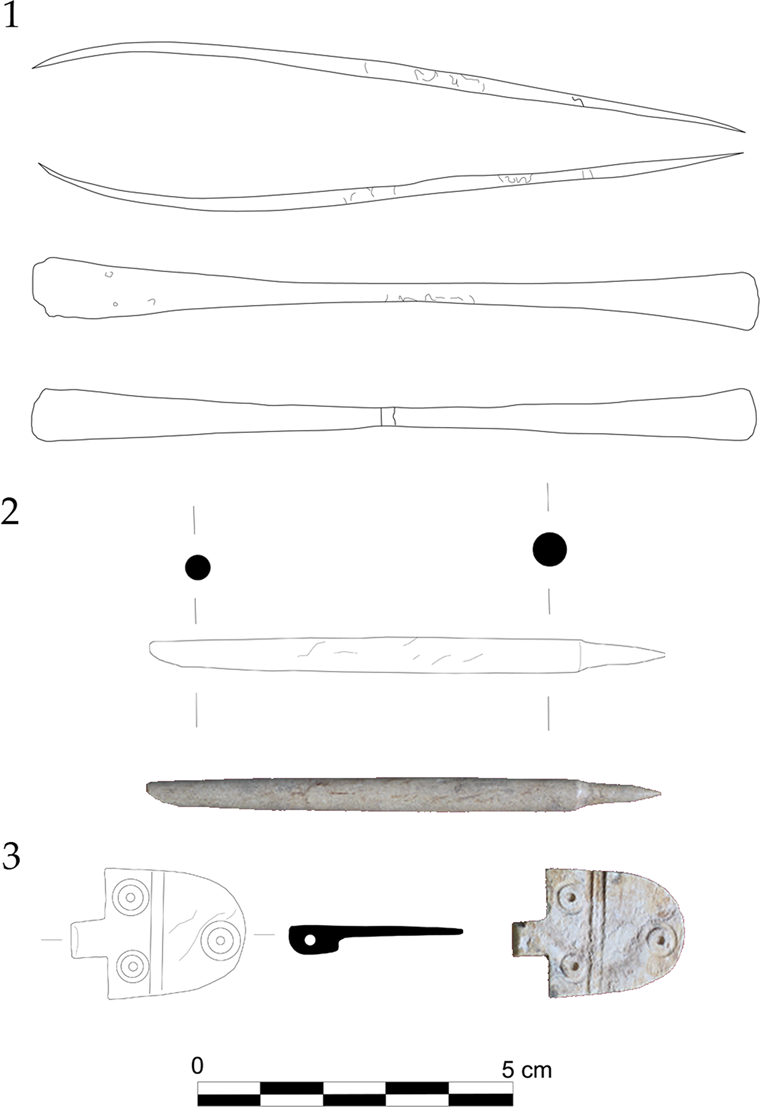

L'Esquerda (Roda de Ter, Osona)

Dating back to the 6th c. BCE, this was probably the capital of the Ausetani (3.7 on Fig. 1). It suffered heavy damages during the Punic Wars but was still occupied during the 2nd and 1st c. BCE. Its defensive system was dismantled during the Roman occupation and the site became a minor settlement with several houses and silos.Footnote 70 Inside “House 3” the cover of a bone seal-box (Fig. 9.1) was found.Footnote 71

Fig. 9. Writing utensils from L'Esquerda, Castellot and Torre de la Sal (Castelló). (Drawings by O. Olesti. Photos courtesy M. Rocafiguera and E. Flors.)

Prats del Rei (Sikarra, Anoia)

Located in an agrarian and pastoral area in central Catalunya (3.8 on Fig. 1), this oppidum from the 5th c. BCE was transformed into the Municipium Sigarrensis during the Roman occupation (1st c. CE). Close to the city wall an Italic temple was erected, probably during the 2nd half of the 2nd c. BCE, of which several columns and blocks survive.Footnote 72 Examples of both Roman material culture (e.g., metalware, Italic cooking ware, mortars, and amphoras) and Iberian script have been found.Footnote 73 A bone seal-box and a bone stylus have been dated to the 2nd/1st c. BCE.Footnote 74

Sant Miquel de Sorba (Solsonès)

This village in the foothills of the Pyrenees (3.9 on Fig. 1) within the territory of either the Lacetani or the Bergistani specialized in grain storage, as evidenced by a large number of silos intra muros. The settlement was transformed during the 2nd and 1st c. BCE, when a new wall and a cistern were built.Footnote 75 Weapons, a riding spur, fragments of a horse harness, a ludus latrunculorum, and several writing instruments imply a military presence. During the 1930s excavations, five bone styli and the cover of a bone seal-box were found, while more recently a bone stylus, a bronze stylus, and a double wax-spatula were unearthed.Footnote 76 This large number of writing instruments might be linked to the site's role as a horreum.

El Castellot (Bolvir, Cerdanya)

Founded during the 4th c. BCE, this minor, 0.6-ha oppidum of the Cerretani (3.10 on Fig. 1) underwent large restructuring from the mid-2nd c. BCE. A gate protected by two towers and several buildings were constructed using Roman units of measurement (decempeda) and patterns (i.e., larger buildings, symmetrical arrangements, and the use of corridors), as well as grain silos and a metal workshop with evidence of iron, copper, lead, cinnabar, silver, and gold production, the last possibly linked to the presence of alluvial gold in the region.Footnote 77 The fact that 75% of the pottery was handmade suggests an indigenous population, while the metallurgical technology and objects such as a ludus latrunculorum and an iron fire starter imply the presence of a Roman garrison. An iron seal-ring (Fig. 9.2) and an iron wax-spatula (Fig. 9.3) were found inside the same building, in a small room with no domestic use, perhaps a scriptorium.Footnote 78 At Tossal de Baltarga, 10 km away, another four seal-rings were found, probably in connection with one of the major roads to cross the Pyrenees.

Gebut/Soses (Lleida)

This oppidum of the Ilergetes (3.11 on Fig. 1) was believed to be active between the 6th and 2nd c. BCE, although, while Late Republican objects are known from old excavations, more recently its abandonment has been placed at the end of the 3rd c. BCE.Footnote 79 In 1844, at a necropolis at nearby Soses, an indigenous grave yielded Iberian coins dated to the 2nd and 1st c. BCEFootnote 80 and a silver ring with an onyx cameo depicting a bearded head. It is inscribed with the Iberian non-dual text sustartike,Footnote 81 probably a personal name, indicating the use of seal-rings in an unambiguously indigenous context.

Torre de la Sal (Castelló)

During the 2nd half of the 2nd c. BCE this coastal Iron-Age oppidum of ca. 10 ha (see Fig. 1) with its associated harbor, 75 km south of the Ebro, was substantially renovated with the construction of, among other buildings, a large horreum, a lime-kiln, a metallurgical workshop, and military barracks.Footnote 82 The settlement is located along the Via Herculea, a coastal road. In a Late Republican layer a complete bronze seal-box (Fig. 9.4) and an iron ring, possibly a seal-ring, were found.Footnote 83At the necropolis, in one of several indigenous cremation burials (dated to the 2nd to mid-1st c. BCE), a possible bone stylus, a box in bronze and wood, and a bronze spatula or spathomele were found.Footnote 84

Hispania Citerior

Also at numerous Roman outposts, oppida, and urban centers close to northeastern Hispania, writing instruments have been identified in layers of the 2nd and 1st c. BCE, where similar patterns can be observed.

Along the east Mediterranean coast, at Son Espases in Mallorca (Palma), a Roman military camp active between 123 and 50 BCE and linked to Quintus Caecilius Metellus’ activities (Strab. 3.5.1), three bone styli, a bronze double spatula (Fig. 10.1), a gold signet ring and an inscribed lead sigillum were found,Footnote 85 while Tossal de la Cala (Benidorm), where a garrison was established, yielded several styli (one of them in a biconical shape) and one seal-ring in bone.Footnote 86 At the oppidum at El Monastil (Elda), two bone styli and an iron seal-ring with a gemstone were documented in an indigenous context.Footnote 87

Fig. 10. Writing utensils from Son Espases (Mallorca) and Marinesque (Loupian). (Drawings by O. Olesti. Photos courtesy M. Feugère.)

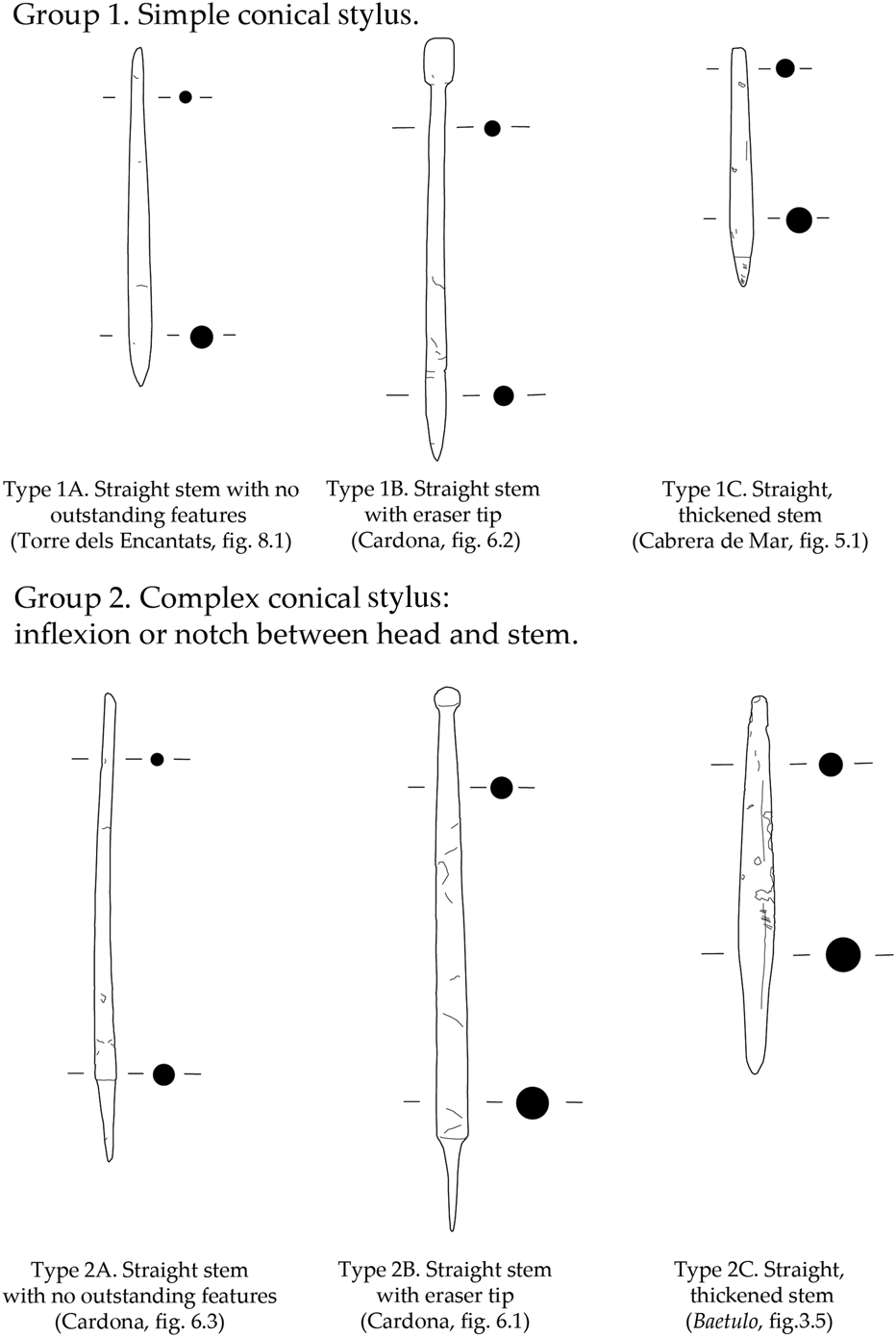

Fig. 11. Author's typology of styli from northeast Hispania. (Drawings by O. Olesti.)

In the Meseta and Castilla regions, several iron styli, a wax-spatula, and a seal-box have been found in the unambiguously military context of the castella surrounding Numantia (Renieblas), all dating to the 2nd/1st c. BCE.Footnote 88 At Cáceres el Viejo, most likely the castrum of Caecilius Metellus during the Sertorian War, four bone styli, one iron stylus, and a possible iron double wax-spatula have been documented.Footnote 89 At the Celtiberian hill fort of Valdeherras-Azafuera, which had a mixed Roman–indigenous population, a seal-ring with an intaglio engraving was found.Footnote 90

Among the indigenous sites in the Ebro river valley that were occupied by or submitted to the army, several show evidence of writing and of stamping pondera with seal-rings.Footnote 91 The Iberian 0.8-ha settlement at Palomar de Oliete (Teruel) that was destroyed during the Sertorian War contained a large number of Iberian inscriptions,Footnote 92 as well as two bone styliFootnote 93 and a pondus stamped with the Iberian sign bim in a regular cartouche.Footnote 94 At La Guardia de Alcorisa (Teruel), several pondera were stamped by a gem with a planta pedis; one of them was stamped three times by the same gem, representing a planta pedis surrounded by an Iberian inscription (the only known instance of a gem inscribed with Iberian writing), probably a personal name;Footnote 95 other pondera were stamped with a female figure, similar to the ones from Puig Castellar. Azaila, el Palao, and Alto Chacón also yielded pondera stamped with intaglios/gems.Footnote 96 At La Cabañeta (El Burgo de Ebro, Zaragoza), an urban foundation with a partially Italian population that was abandoned after the Sertorian War, 23 styli were found.Footnote 97

Gallia Transalpina

At Marinesque (Loupian), 140 km north of the border of Hispania Citerior, a mutatio from 100–50 BCE has been identified along the Via Domitia. Excavations have yielded an astonishing amount of glass and 382 coins (90% of which are bronze and 10% silver) inside the building, but no amphoras.Footnote 98 Identified originally as a taberna, I believe it was a statio because of the presence of several bone styli and the cover of a bone seal-box (Fig. 10.2–3),Footnote 99 but also because of its location on the province's main road. A foundation deposit containing only local silver coins has been seen as evidence for indigenous inhabitants.Footnote 100 Along the same road, 70 km south of Marinesque and 70 km north of Ruscino, a cover of a bone seal-boxFootnote 101 and several styliFootnote 102 were discovered at the Iberian oppidum at Enserune (Nissan-Lez-Enserune) belonging to the Elisyces, which underwent significant reform in the 2nd/1st c. BCE.

In Vieille-Toulouse, the main oppidum of the Volcae Tectosages, 99 bone styli, mostly from the 2nd half of the 1st c. BCE, and the cover of a bone seal-box were discovered.Footnote 103 Recent excavations in ZAC Niel, a settlement founded in ca. 175 BCE in a plain 3 km from Vieille-Toulouse, also unearthed several writing instruments dated to the second half of the 2nd c. BCE.Footnote 104 The latter site showed evidence of metallurgical activity of bronze, lead, iron, and gold, as at El Castellot. Despite the fact that it is considered to have had only an indigenous population,Footnote 105 I believe the site still had contacts with the Roman army, possibly through the presence of a praesidium, a garrison, or Roman army suppliers. Such a hypothesis is supported by the metallurgical activity, the large imports of wine and oil,Footnote 106 an intaglio with a representation of Pegasus, clavi caligae, “sandwich gold-glass” bowls from Delos, a block of rough glass from the area of Judea and several bronze jars from Piatra Neamț, the latter usually a sign of the presence of Roman soldiers.Footnote 107 The discovery of three complete (Gostenènik Type 2) and two broken styli, the cover of a seal-box, the intaglio, three seal-rings (Guiraud type 1B), and a tabula with its wax preserved (found in a well from the end of the 2nd c. BCE),Footnote 108 could together be perceived as a scriba's desktop set from a mostly indigenous site with a small Roman presence.

The literary sources

It is impossible to give an exhaustive list of all ancient references to the use of tablets, seal-rings and writing by the Roman army in Hispania (2nd–1st c. BCE); highlighted here are the most significant ones.Footnote 109

Plutarch (Vit. Ti. Gracch. 6) mentions how Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus, quaestor of Mancinus’ army in Numantia (137 BCE), recovered his official written accounts that had been stolen by the Numantines:

However, all the property captured in the camp was retained by the Numantines and treated as plunder. Among this were also the ledgers of Tiberius, containing written accounts of his official expenses as quaestor. These he was very anxious to recover, and so, when the army was already well on its way, turned back toward the city, attended by three or four companions.Footnote 110

We also know of the praetor L. Piso, who broke his anulus aureus at Corduba during military exercises. When visiting an aurifex in the city's forum to replace it, the new ring, weighing a semiuncia, was produced in front of the people to avoid any suspicion of fraud (Cic. Verr. 2.4.56).

In the army, rings were a way to identify their owners, usually officials and commanders, e.g., when fallen in combat. Livy (23.12) recounts how in 216 BCE, during the Second Punic War, Hannibal Mago brought to the Carthaginian Senate a large number of gold rings (with a combined weight of three modii) that he had obtained on the battlefield. He claimed that such gold rings were worn only by Roman equites, and mainly by the primores.Footnote 111 During the Third Punic War, after Manilius’ defeat at Carthage in 148 BCE, Scipio asked Hasdrubal to bury the tribunes. They searched for them among the bodies, “recognizing them by their signet rings (for the military tribunes wore gold rings while common soldiers had only iron ones)” (App. Pun. 15.104).Footnote 112 Although Pliny (HN 33.5) writes that Late Republican commanders used iron rings and that widespread use of gold rings came only later, these examples indicate that they were used at least by the Second Punic War.

Many anuli also functioned as seals during military operations. Appian (Pun. 108) mentions a letter sent to Scipio in 148 BCE by Phameas, an allied commander in Africa, which the messenger

showed to the consul under seal. Breaking the seal, they read as follows: “On such a day I will occupy such a place. Come there with as many men as you please and tell your outposts to receive one who is coming by night.” Such was the content of the letter, which was without signature, but Scipio knew that it was from Phameas.Footnote 113

Despite the absence of a signature, Scipio's recognition shows that the seals, and thus the seal-rings, must have contained unique images, signs, or symbols that allowed identification of a sender.Footnote 114

Recently, F. Beltrán has pointed out the discrepancy between the small number of preserved Latin documents in Hispania, compared to what must have been producedFootnote 115 – especially, as E. Garcia Riaza has highlighted, given the importance of writing in the relationship between Romans and indigenous communities during the 2nd and 1st c. BCE. He mentions epigraphic sources such as the Contrebian Bronzes (three plaques in Celtiberian and one in Latin of ca. 100–75 BCE) as well as literary references, such as Cato's letters (Liv. 34.17.7) to the northeastern Iberian communities in 195 BCE and the exchange of letters between Scipio and the Numantines in 133 BCE (App. Hisp. 90).Footnote 116 Although very few epigraphic examples survive, I believe that the large number of writing utensils from the northeast Iberian peninsula confirms the importance of written documents in the daily life of the province.

While there is little data regarding tablets, letters, and seals in relation to civic and economic affairs from Hispania, examples from Gallia Narbonensis exist. All debts, loans, registers, and trade needed to be put into writing in account-books and using seals. Cicero (Font. 2.3) refers to the debts recorded in tabulae:

No one – no one, I say, O judges – will be found, to say that he gave Marcus Fonteius one sesterce during his praetorship, or that he appropriated any out of the money which was paid to him on account of the treasury. In no account-books (tabulis) is there any hint of such a robbery among all the items contained in them; there will not be found one trace of any loss or diminution of such monies,Footnote 117

and further that (Font. 10–11):

in the time of this praetor, Gaul was overwhelmed with debt. From whom do they say that loans of such sums were procured? From the Gauls? By no means. From whom then? From Roman citizens who are trading in Gaul. Why do we not hear what they have got to say? Why are no accounts (tabulae) of theirs produced? … All Gaul is filled with traders, full of Roman citizens. No Gaul does any business without the aid of a Roman citizen; not a single sesterce in Gaul ever changes hands without being entered into the account-books of Roman citizens.Footnote 118

These customs were, however, also employed in private life, as Cicero (Fam. 16.26) mentions in reference to his mother: “It was her custom to put a seal (obsignabat) on wine-jars even when empty to prevent any being labeled as empty that had been surreptitiously drained.”Footnote 119

Who was writing and using sealing instruments, and what were they writing about?

The writing utensils discussed in this research show only limited patterns in their deposition, probably due to the different types of sites (Roman cities, outposts, and oppida). For a third of them, no archaeological context is known and some were found ex situ, in abandonment levels or in silos (Tossal de Baltarga, Ruscino). In Valentia and Tarraco they were found in the fora, while in other cities (Ilerda, Iluro, and Baetulo) they emerged from private houses. At the outposts, some come from private houses (Camp de les Lloses), public buildings (the statio at Marinesque) or even ritual deposits (Cardona). At oppida, several appear at city gates (Olèrdola, St. Julià de Ramis, and Burriac), in a private house (l'Esquerda), and in warehouses (Torre Roja and Burriac). Two signet rings were found in tombs (Emporion and Gebut). While domestic contexts dominate, the locations relating to economic activities and access control are hardly surprising.

At Valentia, I believe that the writing instruments were part of the equipment of the Roman commander and two officers. Sallust's account (Hist. 3.83) of Sertorius’ murder, stabbed while reclining at the table with his two scribae,Footnote 120 seems to indicate that Roman commanders always had their scribae with them (so perhaps, at Valentia, the two younger men were scribae); they also always carried their anuli, as did Piso in Cordoba.

In other cities, too, the writing utensils were part of the economic and administrative tasks. Cicero's comments about the role of Roman citizens or Italici in business, trade, agriculture, and livestock in Gallia Narbonensis, and about the use of tablets and signet rings, are probably just as applicable to Hispania Citerior.Footnote 121 Most of the time, their business was conducted with Gauls.Footnote 122 The presence of an iron seal-ring at Emporion in an indigenous grave from the 2nd half of the 1st c. BCE shows that seals were not only used by the Italian and Greek populations and, just as with inscriptions, sealed documents in Iberian must have existed. The two Late Republican lead seals mentioning the slaves Philo() M(arci) s(ervus) and Sus(as) Sex(ti) s(ervus) are probably linked to families connected to Caesar, the deductor of the city.Footnote 123 At Tarraco, the writing instruments were found near the basilica in the forum. As it was the province's capital and a major harbor, the collection and control of the portoria, the taxes at provincial boundaries, took place here.Footnote 124 The presence of writing instruments at Iluro and Baetulo can similarly be linked to their function as coastal cities, open to maritime trade and supply chains. At Ilerda, the stylus and seal-box were found in the Late Republican structures on the hill, and not inside the lower, Ibero-Roman city. Similarly, at Ruscino the styli come from earlier contexts than the Augustan foundation. The usage of the writing instruments dates in both cases to a phase between the Romanized oppidum and the new Roman city, so indigenous inhabitants as well as new Roman settlers could have been the owners.

For Roman outposts, the question is why so many writing instruments are found there. In line with the example of Tiberius Gracchus above, many scholars have highlighted the enormous number of written documents that the army produced for recording, e.g., supplies, role lists, payments, orders, duties, and appointments, especially between the 1st and 3rd c. CE.Footnote 125 Most of these would have been only for temporary use and written on perishable material. Therefore, the tablets, styli, seal-rings, and seal-boxes at these sites could be indicators of military presence. Some outposts, however, were further occupied by negotiatiores, mangones, traders, women, indigenous people, freedmen, and publicani, especially those connected to the control and management of local resources: rock salt at Cardona; gold, silver, and iron at Tossal de Baltarga; and iron at Camp de les Lloses. Some must therefore have been stationes where the provincial administration deployed their stationarii and tax collectors and where official communications were sent.Footnote 126 Civil administrative presence would not have opposed military presence at the same time, as they could combine their interests. Some scholars have pointed out the connection of these outposts with the logistical needs of the army in the northeast and their role in key events, such as the Cimbrian Wars. The number of supplies and auxilia that the Roman army required for wars at the end of the 2nd c. BCE, especially in Gaul, explains the exploitation of these sites in northeast Hispania.Footnote 127 Not all Roman outposts, however, can be linked to this theory, because many were founded around the middle of the 2nd c. BCE and because the needs of the Roman army formed only part of the total requirements: metals, cattle, cereals, and wood were also taxed and collected for provincial revenue, for the interests of publicani, and for Rome.Footnote 128

It is probably impossible to distinguish between military and fiscal stationes during the Late Republican period,Footnote 129 although the absence of military defenses could be an indication, as would be the presence of freedmen. Early imperial tributary stationes (linked to the portoria or the vectigalia) were occupied by freedmen or slaves under the control of the provincial or imperial procuratores, a role that in the 2nd and 1st c. BCE had to be performed by publicani or even their subordinates.

The presence of writing instruments in the oppida is, however, the most remarkable result of this research. Many indigenous settlements continued under Roman occupation,Footnote 130 and the landscape was transformed and adapted (with the appearance of new indigenous farms in the lowlands) but it was still based on indigenous productive patterns in agriculture, rearing of livestock, and trade. The Roman administration employed several systems to control and collect taxes,Footnote 131 e.g., by praefecti (in this context, military officials) in the oppida.Footnote 132 It is clear that the Roman taxation system was still at an early stage, based in part on ad hoc requisitions,Footnote 133 but this does not change the importance of local patterns of production. Oppida still controlled and exploited a large part of the land and its resources (especially agriculture and livestock), and the Roman administration drained off some of the surplus. Wheat was their main production, as evidenced by the silos at St. Miquel de Sorba, El Castellot, Burriac, Turó del Vent, Puig Castellar, and St. Julià de Ramis. The presence of writing instruments probably constitutes proof of recording systems, inventories, and the exchange of messages and documents, especially when found in combination with weights and balance scales. As C. Nicolet has pointed out, Rome undertook the inventory of the world, in this case at the oppida, and writing instruments were part of the procedure.Footnote 134 Of course, this inventory system was developed by the Roman army and the army's infrastructure was at the base of the taxation system, but the oppida were equally part of the network. In some cases, it is possible to determine the existence of a garrison (such as a praesidium or a hiberna) at an oppidum and this could explain the presence of writing instruments – Olèrdola is probably the best example.Footnote 135 But it is also possible to find Roman traders or dependants of the publicani, such as freedmen, interacting with the Iberian communities.

Lastly, Iberian people probably also used writing instruments for their own needs, such as trade and management. The expansion of Iberian writing during the 2nd/1st c. BCE implied an increase in the need for recordkeeping and communication,Footnote 136 brought on by the interaction between the indigenous people (especially the elites) and the Romans, the integration of the local economy into a Mediterranean framework, and the incorporation of new technologies in agriculture, pottery production, and metallurgy. As evidence for these processes, scholars have pointed to styli found inside wine-warehouses at Burriac and Torre Roja, the pondera in Puig Castellar marked by gems, and stamps in Iberian script and with Iberian anthroponyms on local amphoras imitating Dressel 1, mortars, dolia, and other types of pottery.Footnote 137 Iberian auxilia, whose cultural, linguistic, and writing traditions were adapted by participation in the Roman army,Footnote 138 played an important role in the diffusion of writing.

As to the question of who was writing, the military presence at most of the sites, including at stationes and oppida, implies that members of the Roman army were the main people writing.Footnote 139 Contributions and taxes were collected by the provincial administration with the support of the army through this network of outposts and oppida, and the system generated a large number of written documents. Auxilia and indigenous scribae also used these writing and sealing instruments, in this way spreading Latin among Iberians.Footnote 140

A second group of people would have been Italian traders (e.g., negotiatores and mangones), landowners, and publicani who accompanied the army and provincial administration. In this study, they are probably represented by the freedmen documented at Cardona, Olèrdola, and Emporion.Footnote 141 At Camp de les Lloses, Cardona, and Olèrdola, writing instruments were found in the same rooms as lead and bronze weights and sometimes steelyard balances, indicative of measuring and accounting.Footnote 142 This could mean that many writing instruments were not used for writing texts but for book-keeping related to the new commercial patterns, taxation, and a monetized economy.

Finally, the presence of these objects in unambiguously indigenous contexts allows us to reconsider the spread of literacy. Given the number of writing utensils, the lack of written documents cannot be considered indicative of a low level of literacy and Latinization among the local communities, both of which are higher and older than expected. The predominance of Iberian texts on pottery (mostly property marks) could be balanced if we accept that documents and writing by indigenous populations are implied by the presence of styli and seals in oppida and at logistical sites where the percentage of Iberian graffiti overshadows the Latin ones. We may never know which language they used on tabulae or papyri, but the rapid spread of Latin from the Augustan period onward and the quick disappearance of Iberian is easier to understand if we take into account these missing earlier texts.

Conclusions

The writing instruments in this research date to a turbulent period of occupation and exploitation in the northeastern Iberian peninsula. From the middle of the 2nd c. BCE the economic and social transformation after the conquest involved deep changes in settlement patterns. Many oppida were transformed using Roman techniques, and both oppida and new indigenous farms were controlled by Roman outposts. The mechanisms for land management, exploitation of local resources, and taxation partly survive in the archaeological record through the diffusion of writing instruments.

From the start of provincial organization, literary sources (Liv. 34.21.7; Gell. NA 2.22.28) mention that the first tax control systems were implemented on key resources.Footnote 143 Taxation and control imply evaluation and the keeping of records, both of which require the use of instrumenta scriptoria. The function of some sites that yielded writing instruments in this research was to control these resources: salt at Cardona; gold and silver at El Castellot de Bolvir; iron production at Cabrera de Mar, Camp de les Lloses, Torre dels Encantats, and El Castellot; and cereals at Torre Roja, St. Miquel de Sorba, and Torre de la Sal.Footnote 144 A first phase, which took place roughly during the first half of the 2nd c. BCE, was still based on a system of management of resources and populations inherited from the war period, sometimes defined as the “war economy.”Footnote 145 This system nevertheless further developed strategies that increased key resources, such as agriculture (especially grain and livestock), minerals, and humans (in the form of auxilia or even slaves). From the middle of the 2nd c. BCE, however, a more interventionist and dynamic period began, which involved the formation of a network of productive establishments, logistical sites, roadside centers, and garrisons. The sites presented above were part of this network, and most of the instrumenta scriptoria identified in this paper belonged to this period, which lasted until ca. 50 BCE. This network of stationes and garrisons had a double function. On the one hand, it was to guarantee the control and submission of the conquered areas, hence its proximity to the main indigenous oppida and its insertion into the existing road network. On the other, it was to serve as logistical centers for the collection of the natural, productive, and human resources of the territory. Directly or indirectly, the Roman army was present in these logistical centers and its infrastructure was the backbone through which provincial goods circulated, guaranteeing both its own supply and exports to Italy.

Although not always correctly identified by archaeologists, the styli, seal-boxes, wax-spatulae, and signet rings may be archaeological indicators of Roman involvement in the management of Spanish resources and peoples. In this way, the need for control and exploitation contributed to the spread of writing and inventorying among indigenous communities, as well as to the complex mechanisms of cultural integration and Romanization.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1 is an inventory of the writing instruments discussed in this article; organized by site, it provides references to images, archaeological context, chronology, and typological classification. To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047759420001191.

Acknowledgments

The research for this paper was funded by Project MINECO, Paisajes de la Hispania Romana (2. HAR2017-87488-R). This paper has been made possible thanks to the help of numerous researchers, as mentioned in the text. I would especially like to thank M. Feugère for his help and guidance and A. Ward for help with the English text. I also wish to thank the editors and the anonymous referees for their suggestions.