Introduction

Saudi Arabia has been undergoing rapid population growth for several decades, along with intense economic and industrial development. This development resulted in the country becoming the fastest growing electricity consumer in the Middle East (Baradieh Reference Baradieh2015). To meet this increasing demand, numerous new power generation projects are being developed throughout Saudi Arabia. In 2016, the electrical grid in the country consisted of 70,347 km of power lines (Global Transmission Report 2017), but Saudi Arabia’s 2030 vision to produce 9.5 GW of renewable energy by 2023, will likely double the number of power lines in the next decade (Baradieh Reference Baradieh2015, Chite and Ahmad Reference Chite and Ahmad2017).

Infrastructure for the transmission and distribution of electric power can cause bird mortality due to collision and electrocution (Bevanger Reference Bevanger1998, Lehman et al. Reference Lehman, Kennedy and Savidge2007, Bernardino et al. Reference Bernardino, Bevanger, Barrientos, Dwyer, Marques, Martins, Shaw, Silva and Moreira2018), and this mortality can have population-level impacts on threatened species (Schaub et al. Reference Schaub, Aebischer, Gimenez, Berger and Arlettaz2010, Angelov et al. Reference Angelov, Hashim and Oppel2013, Loss et al. Reference Loss, Will and Marra2014). Because Saudi Arabia is centrally located along one of the most important migratory bird flyways of the world (Shobrak Reference Shobrak2011, Meyburg et al. Reference Meyburg, Meyburg and Paillat2012, Buechley et al. Reference Buechley, Oppel, Beatty, Nikolov, Dobrev, Arkumarev, Saravia, Bougain, Bounas, Kret, Skartsi, Aktay, Aghababyan, Frehner and Şekercioğlu2018), the design of the power infrastructure at important congregation sites for migratory birds is of special concern, and warrants investigation to assess the potential impacts (AEWA 2012, Eccleston and Harness Reference Eccleston, Harness, Sarasola, Grande and Negro2018).

Avian mortality due to collision and electrocution with powerlines occurs in Saudi Arabia (Shobrak et al. Reference Shobrak, Al Husaini and Suhaibani2009, Shobrak Reference Shobrak2012), but so far little evidence exists for the mortality of raptors, despite Saudi Arabia hosting considerable populations of raptor species (Shobrak Reference Shobrak2011, Meyburg et al. Reference Meyburg, Meyburg and Paillat2012, Phipps et al. Reference Phipps, López-López, Buechley, Oppel, Álvarez, Arkumarev, Bekmansurov, Berger-Tal, Bermejo, Bounas, Alanís, de la Puente, Dobrev, Duriez, Efrat, Fréchet, García, Galán, García-Ripollés, Gil, Iglesias-Lebrija, Jambas, Karyakin, Kobierzycki, Kret, Loercher, Monteiro, Morant Etxebarria, Nikolov, Pereira, Peške, Ponchon, Realinho, Saravia, Sekercioğlu, Skartsi, Tavares, Teodósio, Urios and Vallverdú2019). In November 2019, the world’s largest known wintering congregation of Steppe Eagles Aquila nipalensis was discovered near a rubbish dump at Ushaiqer in central Saudi Arabia (Keijmel et al. Reference Keijmel, Babbington, Roberts, McGrady and Meyburg2020). The Steppe Eagle is extremely vulnerable to electrocution at powerlines (Levin and Kurkin Reference Levin and Kurkin2013, Meyburg and Boesman Reference Meyburg, Boesman, Hoyo, Elliott, Sargatal, Christiea and Juana2016), and is now classified as globally ‘Endangered’ (BirdLife International 2020) partly due to mortality at electricity infrastructure leading to population declines (Karyakin and Novikova Reference Karyakin and Novikova2006, Lasch et al. Reference Lasch, Zerbe and Lenk2010, Kamp et al. Reference Kamp, Koshkin, Bragina, Katzner, Milner-Gulland, Schreiber, Sheldon, Shmalenko, Smelansky and Terraube2016). Given the importance of Saudi Arabia for Steppe Eagles, their inherent vulnerability to electrical infrastructure, and the rapidly expanding electricity network, more information on the actual and potential impacts of electricity infrastructure on the species in Saudi Arabia is needed.

During surveys aimed at identifying threats within a flyway-scale conservation project (Shobrak et al. Reference Shobrak, Alasmari, Alqthami, Alqthami, Al-Otaibi, Zoubi, Moghrabi, Jbour, Arkumarev, Oppel, Asswad and Nikolov2020), we surveyed powerlines in two regions of Saudi Arabia that are important for migratory raptors. Here we report the mortality observed near two winter congregation areas of Steppe Eagles and highlight that the dangerous design of Saudi Arabia’s typical electricity infrastructure may pose a mortality risk that could have population-level consequences for this globally endangered species.

Methods

Study area

We report observations from two rubbish dumps where large numbers of raptors congregate: (1) a rubbish dump 10 km south of Al Qunfudhah city (25.303472°N, 45.125593°E) that was discovered opportunistically in November 2019; and (2) a rubbish dump 3.5 km south-west of Ushaiqer town (19.072893°N, 41.189493°E), also discovered in November 2019 following the investigation of GPS-tracked birds (Keijmel et al. Reference Keijmel, Babbington, Roberts, McGrady and Meyburg2020). The Ushaiqer rubbish dump hosted 5,320 Steppe Eagles during our survey, making it the largest known congregation area for the species in the world (Keijmel et al. Reference Keijmel, Babbington, Roberts, McGrady and Meyburg2020). At Al Qunfudhah, we observed 153 Steppe Eagles and 2,275 Black Kites Milvus migrans on 14 Nov 2019, but because birds roosting on the ground were not visible, and because the migration peak of Steppe Eagles occurs in October (Meyburg et al. Reference Meyburg, Meyburg and Paillat2012, Meyburg and Boesman Reference Meyburg, Boesman, Hoyo, Elliott, Sargatal, Christiea and Juana2016), the site is likely to be used by more eagles than we observed.

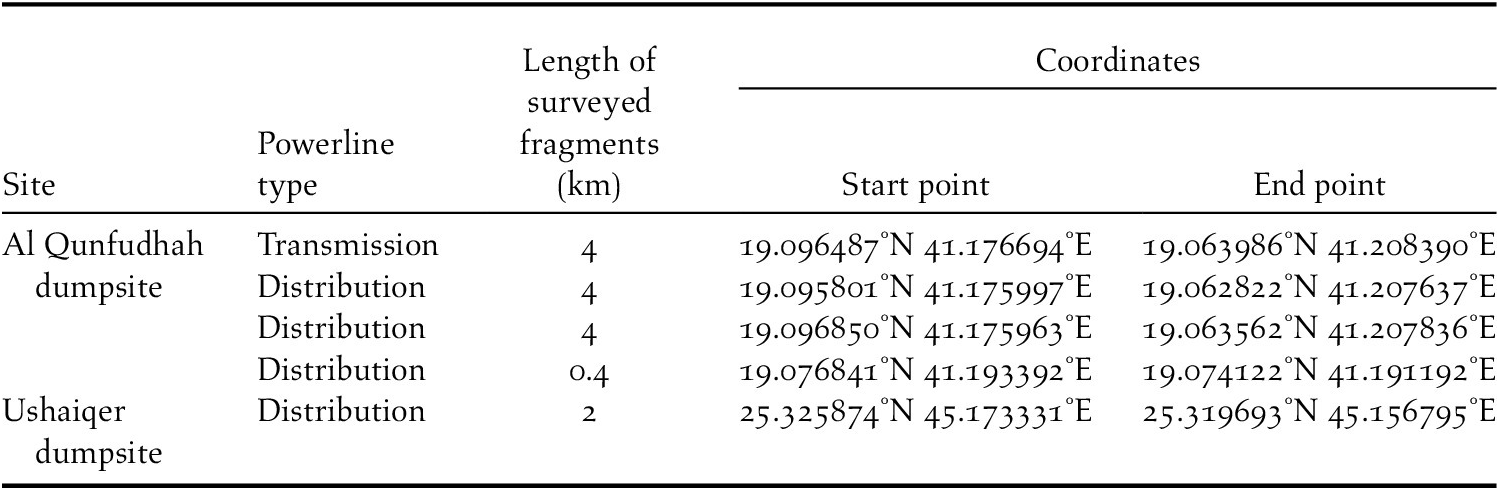

Around each congregation site we assessed all powerlines within a 6-km radius (Table 1), as those would be frequently used by roosting Steppe Eagles (Keijmel et al. Reference Keijmel, Babbington, Roberts, McGrady and Meyburg2020). In addition, we also report surveys of powerlines in the wider region away from these congregation areas to provide a comparison with the mortality at other powerlines along (1) the south-west coast of Saudi Arabia between Jeddah and Al Qunfudhah, Mecca Provence; and (2) the area around Shakra and Ushaiqer, Riyadh Provence (Figure 1).

Table 1. Location, type, and length of powerlines surveyed within 6 km of Steppe Eagle congregation sites in Saudi Arabia in November 2019.

Figure 1. Location of the two Steppe Eagle congregation sites in Saudi Arabia: (1) Al Qunfudhah, Mecca Province; and (2) Ushaiqer, Riyadh Province. Grey areas indicate the region in which other powerlines were surveyed outside the immediate congregation areas.

Powerline surveys

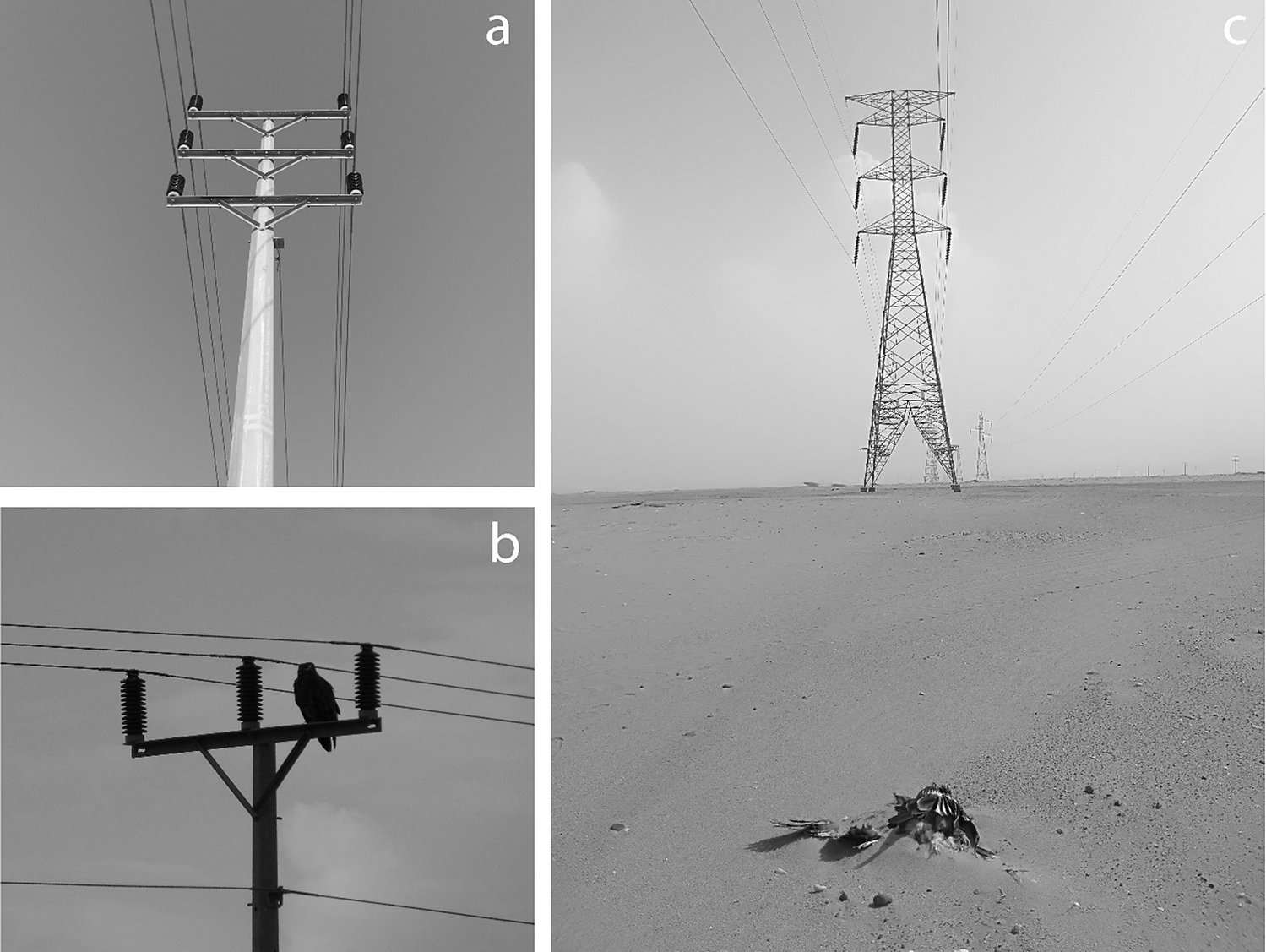

Three simultaneously operating teams conducted surveys to search different powerlines between 10 and 16 November 2019 (five days between Jeddah and Al Qunfudhah, two days around Ushaiqer). We focused on powerlines that were expected to pose a high mortality risk due to their design (Table 1, Figure 2); we surveyed all low- to medium-voltage distribution lines that were supported by single poles with a cross-bar and conducting wires propped up above the support structure with insulator pins (Bevanger Reference Bevanger1998, AEWA 2012, Bernardino et al. Reference Bernardino, Bevanger, Barrientos, Dwyer, Marques, Martins, Shaw, Silva and Moreira2018). We also searched high-voltage transmission lines within 6 km of the rubbish dump at Al Qunfudhah, where many Steppe Eagles were observed to roost on pylons (no transmission lines existed within 6 km of Ushaiqer; Table 1). The length of surveys ranged from 300 m to 20 km, depending on the length and accessibility of powerline sections that met our criteria of high bird mortality risk. The start and end points of each survey were recorded with GPS, and the length of each surveyed line was recorded.

Figure 2. Hazardous powerline support poles (a, b) and transmission pylons (c) around Al Qunfudhah and Ushaiqer dumpsites in Saudi Arabia.

Surveys were conducted by two or more observers walking or driving slowly under each powerline and searching the ground and any adjacent vegetation where scavengers may have dragged collision or electrocution victims (Demerdzhiev Reference Demerdzhiev2014, Costantini et al. Reference Costantini, Gustin, Ferrarini and Dell’Omo2017). Any carcasses or remnants of carcasses were identified to a species, and the stage of each carcass was recorded in three coarse categories: fresh (<1 week old), between 1 week and 1 month old (complete birds), or scattered parts and remains of birds older than 1 month.

Data analysis

For each of the two congregation areas around rubbish dumps, we first calculated the number of victims encountered per km of powerlines surveyed. We also calculated this observed encounter rate of victims for additional powerlines away from the two congregation sites to provide a baseline for bird mortality away from congregation sites. We caution that actual bird mortality is likely to be underestimated by our method, because it does not account for carcass removal by terrestrial predators (Ponce et al. Reference Ponce, Alonso, Argandoña, García Fernández and and Carrasco2010, Shobrak Reference Shobrak2012, Costantini et al. Reference Costantini, Gustin, Ferrarini and Dell’Omo2017), and for sandstorms covering carcasses within a short period of time.

Despite the crude nature of our observational data, it is useful to coarsely extrapolate the minimum annual mortality of Steppe Eagles around the two congregation sites that can be inferred from our data. We used the information on carcass age to define a time interval over which the observed number of carcasses had accumulated. We first used only the carcasses found in a ‘fresh’ state (assumed to be <1 week old) to calculate how many birds were killed by the surveyed powerlines within one week. We then used all carcasses found in a ‘fresh’ or intermediate state (assumed to be <1 month old) to calculate how many birds were killed by the surveyed powerlines within one month. Due to the temporary presence of migratory birds during certain months, mortality rates will be unevenly distributed throughout the year. We therefore assumed that Steppe Eagles spend only four months per year in Saudi Arabia (Meyburg et al. Reference Meyburg, Meyburg and Paillat2012, Meyburg and Boesman Reference Meyburg, Boesman, Hoyo, Elliott, Sargatal, Christiea and Juana2016, Keijmel et al. Reference Keijmel, Babbington, Roberts, McGrady and Meyburg2020), and extrapolated their annual mortality by multiplying the weekly rate by 16 and the monthly rate by four. Extrapolations based on the weekly rate are likely to function as maximum estimates, because they assume that mortality will be equally high every week for all four months. Extrapolations based on the monthly rate are likely to function as minimum estimates, due to the much greater potential for carcasses to be removed or buried by sand within a month. We calculated the proportion of the global population that our extrapolations represented, assuming that the global population numbered 80,000–160 000 birds of all age classes (Karyakin et al. Reference Karyakin, Nikolenko and Shnayder2018).

Results

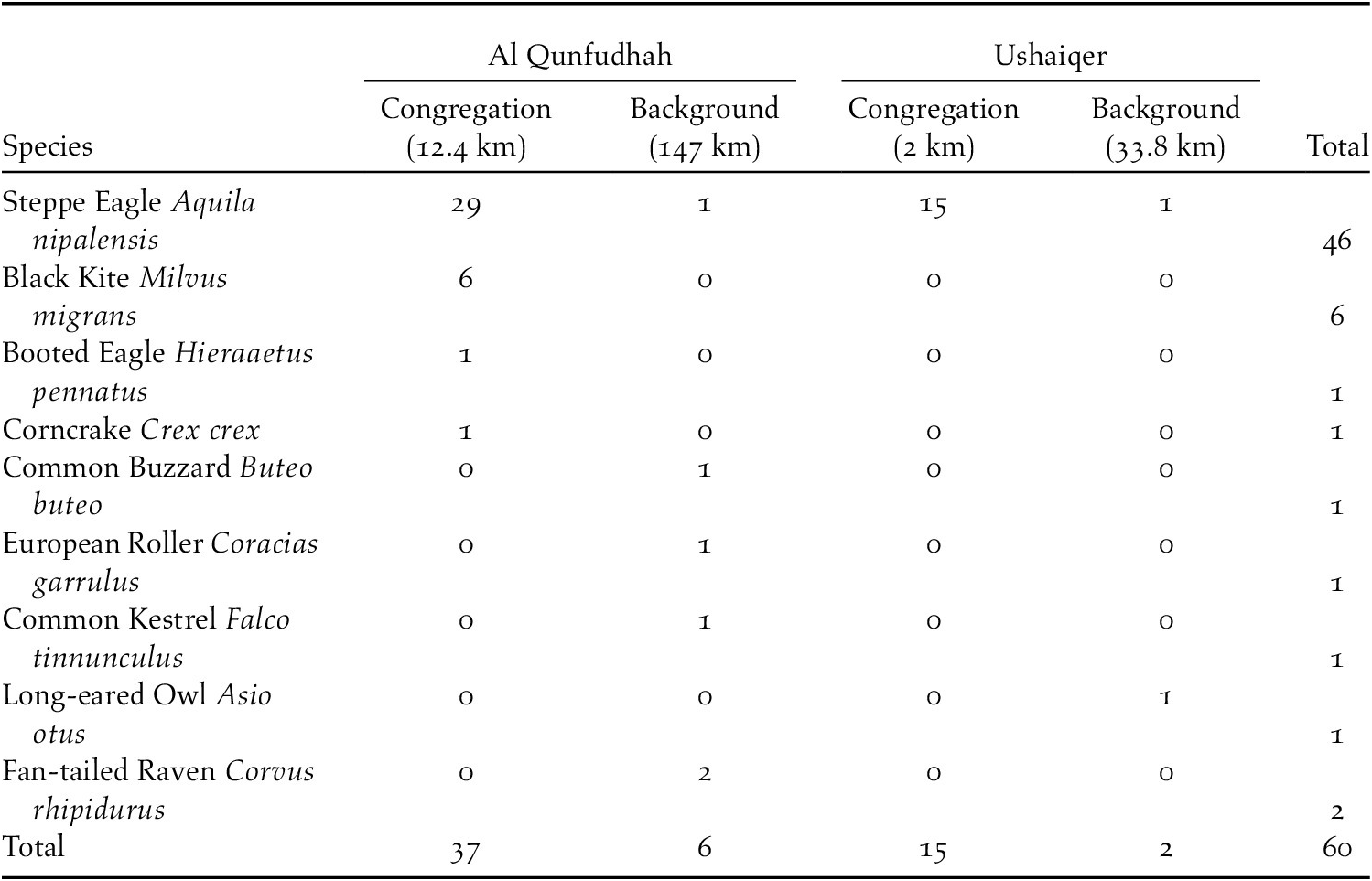

We found high levels of bird mortality due to electrocution and collision with powerlines, with a total of 52 carcasses found along the 14.4 km of powerlines within 6 km of the two congregation sites, of which 85% were Steppe Eagles (Table 2). The carcass encounter rate for Steppe Eagles was 2.3 ind./km around Al Qunfudhah (3.0 ind./km for all birds), and 7.5 ind./km at Ushaiqer (Table 2), where 15 electrocuted Steppe Eagles were found under a single medium-voltage powerline consisting of 20 hazardous poles (Fig. 2). Compared to the high mortality near congregation sites, surveys of powerlines with a similar design in the wider region surrounding congregation areas revealed a lower carcass encounter rate of only 0.007 Steppe Eagles/km (0.04 birds/km) around Al Qunfudhah, and 0.03 Steppe Eagles/km (0.06 birds/km) around Ushaiqer (Table 2).

Table 2. Number of bird carcasses found during 52 powerline searches in two regions of Saudi Arabia in November 2019, separated by those within 6 km of congregation sites of Steppe Eagles (Table 1) and other lines farther away from the congregation sites (background). The total distance of surveyed power lines is indicated for each group.

At Al Qunfudhah, 22 of the Steppe Eagle carcasses were considered <1 month old. At Ushaiqer, only four carcasses were considered fresh while the others appeared to be older than 1 month (Table 3). If these mortality rates are extrapolated over the four-month wintering period of Steppe Eagles, we would expect an annual loss of 88–176 Steppe Eagles at Al Qunfudhah, and 16–64 Steppe Eagles at Ushaiqer (Table 3). Thus, dangerous electricity infrastructure around these two locations alone may potentially kill 0.15–0.30% of the global Steppe Eagle population every winter.

Table 3. Extrapolated annual mortality of Steppe Eagles along dangerous powerlines within 6 km of congregation sites in two regions of Saudi Arabia, based on the age of discovered carcasses in November 2019. Minimum annual mortality is extrapolated by assuming that the number of <1-month old carcasses occurs four times per year, maximum annual mortality assumes that the number of <1-week old carcasses occurs 16 times per year. Note that even our ‘maximum’ extrapolation may underestimate annual mortality due to the imperfect detection of carcasses.

Discussion

We provide substantive evidence about disconcerting bird mortality due to electrocution and collision with powerlines in Saudi Arabia; and we highlight that globally important congregations of Steppe Eagles are exposed to dangerous electricity infrastructure that may kill hundreds of individuals of this threatened species every year at just two locations. Because electricity infrastructure with a similar dangerous design is ubiquitous in Saudi Arabia, urgent action is needed to safeguard the existing infrastructure, and ensure any new infrastructure uses a safer design to avoid the continued mortality of migratory birds.

The Steppe Eagle is known to be vulnerable to electrocution and collision with powerlines (Levin and Kurkin Reference Levin and Kurkin2013, Meyburg and Boesman Reference Meyburg, Boesman, Hoyo, Elliott, Sargatal, Christiea and Juana2016), and our surveys confirmed this vulnerability. We found far more carcasses of Steppe Eagles compared to those of Black Kites, despite the latter species being much more abundant at Al Qunfudhah. Our results demonstrate that Steppe Eagle mortality at winter congregation sites matches or exceeds mortality rates found for the species on breeding grounds, but we caution that existing estimates are not directly comparable due to differences in survey method and bird density (Table 4). Our estimates are based on opportunistic surveys, and much greater survey effort (i.e. daily inspections of the same power lines) would be necessary to quantify mortality rates more accurately. Spatially concentrated electrocution in eagles, clustered in areas associated with hazardous pole design and abundance of food sources, have also been found in the Mediterranean region (Guil et al. Reference Guil, Fernández-Olalla, Moreno-Opo, Mosqueda, Gómez, Aranda, Arredondo, Guzmán, Oria, González and Margalida2011, Reference Guil, Colomer, Moreno-Opo and Margalida2015). Although our surveys probably detected only a fraction of actually occurring mortality (Ponce et al. Reference Ponce, Alonso, Argandoña, García Fernández and and Carrasco2010, Shobrak Reference Shobrak2012, Costantini et al. Reference Costantini, Gustin, Ferrarini and Dell’Omo2017), even that level of mortality could negatively affect the global Steppe Eagle population if it persists for many years (Angelov et al. Reference Angelov, Hashim and Oppel2013). Given that the rubbish dump of Ushaiqer is the largest known congregation site for the species in the world (with c.6,000 ind., Keijmel et al. Reference Keijmel, Babbington, Roberts, McGrady and Meyburg2020), the presence of dangerous infrastructure that evidently causes mortality is of great concern. In addition, the extrapolated number at Al Qunfudhah suggested that >50% of the Steppe Eagles we observed at the site during our November surveys may be killed, although the exact number of victims cannot be quantified. Al Qunfudhah is located along an important flyway for Steppe Eagles (Meyburg et al. Reference Meyburg, Meyburg and Paillat2012, Meyburg and Boesman Reference Meyburg, Boesman, Hoyo, Elliott, Sargatal, Christiea and Juana2016) and may therefore be used by a large number of transient individuals throughout a migration or winter season. Thus, dangerous electricity infrastructure of limited extent may affect a relevant number of birds that could be substantially larger than that observed at any given time (Angelov et al. Reference Angelov, Hashim and Oppel2013).

Table 4. Carcass encounter rate (‘mortality’, in number of individuals / km) of Steppe Eagles along powerlines in various parts of the world. Note that due to differences in search intensity and carcass detection probability in different environments geographic variation may be confounded by differences in survey methods and by Steppe Eagle density (likely higher on wintering grounds in Saudi Arabia).

Because all medium-voltage distribution lines observed during our surveys had a hazardous design, the risk of electrocution mortality is likely more widespread than our limited survey can demonstrate. Urgent action is required to phase out the hazardous power distribution design across all electricity networks in Saudi Arabia. Dangerous infrastructure near attractive congregation sites across the country will likely cause bird mortality that could be orders of magnitude larger than our localized study suggests. We therefore recommend that any power infrastructure within a 10–20 km radius of garbage and livestock disposal areas, attractive to scavenging birds, is revised to reduce the risk of electrocution and collision (AEWA 2012). The appropriate mitigation measures taken depend on whether mortality primarily occurs through electrocution or collision, which may require further investigation as our inspection of old carcasses did not permit an accurate assessment of the cause of mortality. To reduce electrocution in the short term, insulation caps with extensions - considering the large wingspan of eagles - can be installed on medium voltage power poles, or insulated cables can be installed on these lines. To reduce collisions at high voltage transmission pylons, diverters can be mounted following existing guidelines (Bayle Reference Bayle1999, AEWA 2012, Chevallier et al. Reference Chevallier, Hernández-Matías, Real, Vincent-Martin, Ravayrol and Besnard2015). However, the efficiency of short-term mitigation measures may be jeopardized by the degradation of insulation materials, thus structural changes in pole design are required (Guil et al. Reference Guil, Fernández-Olalla, Moreno-Opo, Mosqueda, Gómez, Aranda, Arredondo, Guzmán, Oria, González and Margalida2011). In the long term, the threat from electricity infrastructure can be minimized if bird-safe pylon designs are used for all future developments, and existing hazardous powerlines are replaced with safe designs. Structural changes should consider eliminating phases above the crossarm and increasing the distance between the perch sites and wires, e.g. the length of string insulators (Guil et al. Reference Guil, Fernández-Olalla, Moreno-Opo, Mosqueda, Gómez, Aranda, Arredondo, Guzmán, Oria, González and Margalida2011). We therefore urge funders and policy makers to revise the design requirements for infrastructure and develop infrastructural standards that guarantee safety for large birds and other biodiversity.

Acknowledgements

This survey was initiated and conducted within the framework of the LIFE project “Egyptian Vulture New LIFE” (LIFE16 NAT/BG/000874, www.LifeNeophron.eu) funded by the European Commission and co-funded by the “A. G. Leventis Foundation”. We are thankful to Dr. Hany Tatwany, the vice president of the Saudi Wildlife Authority, for the encouragement and provision of all logistical support and permissions. We are thankful to Taif University, Saudi Arabia, for support under Researcher Supporting project number TURSP-2020/06. Mike McGrady and Misha Keijmel provided telemetry data for Steppe Eagles and navigated us to the Steppe Eagle congregation site near Ushaiqer. We appreciate the constructive feedback of three reviewers and the associate editor Antoni Margalida, and the assistance of Caroline Mead to help with the English language.