Introduction

Suicide is a major cause of death and health impairment. According to a report of the United Nations, more people die by suicide every year than by both homicide and war (UN, 2009). The World Health Organization announces that worldwide around 800 000 people commit suicide each year, highlighting the reduction in suicide-related mortality as a ‘global imperative’ (WHO, 2019). The number of individuals who attempt suicide every year is a multiple of suicides.

Unfortunately, prediction and prevention of future suicide attempts (SAs) or suicides are complicated notably due to a lack of valid diagnostic instruments and insufficient knowledge regarding their complex pathophysiological mechanisms (Sobanski, Bär, & Wagner, Reference Sobanski, Bär and Wagner2015; Woodford et al., Reference Woodford, Spittal, Milner, McGill, Kapur, Pirkis and Carter2019). Nevertheless, one of the strongest clinical predictors of an SA or suicide is a history of prior SAs (Franklin et al., Reference Franklin, Ribeiro, Fox, Bentley, Kleiman, Huang and Nock2017). A recent meta-analysis of 100 studies has clearly shown that in the first 3 months after discharge from psychiatric facilities, the suicide rate was approximately 100 times higher than the global suicide rate (Chung et al., Reference Chung, Ryan, Hadzi-Pavlovic, Singh, Stanton and Large2017). Also, many years after discharge, the suicide rates are still 30 times higher than typical global rates. Furthermore, there is a substantial risk of dying by a subsequent attempt for individuals surviving an index attempt (Bostwick, Pabbati, Geske, & McKean, Reference Bostwick, Pabbati, Geske and McKean2016; Nordentoft, Mortensen, & Pedersen, Reference Nordentoft, Mortensen and Pedersen2011). Thus, these studies underscore the urgent need for implementing treatment strategies specifically tailored for suicide attempters to reduce the risk of a re-attempt or suicide.

An important issue in suicidology is the inconsistency of terms used to describe suicidal behaviour. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5 (DSM-5) proposed criteria for ‘suicidal behaviour disorder’ (SBD) to establish a common language for researchers and clinicians as well as to set the basis for improved identification and definition (Oquendo & Baca-Garcia, Reference Oquendo and Baca-Garcia2014). SBD has been defined as a ‘Condition for Further Study’, thus considering it as a possible category of its own and not solely as a symptom of a mental disorder. In this way, the DSM-5 may forward the development of approaches for better integration of SBD into clinical routine and for the development of more specific and effective psychotherapeutic as well as pharmacological treatments.

In DSM-5, SBD is characterized by attempted suicide within the past 2 years. A key feature of this definition is an expectation that the SA is lethal, from which the ‘intention to die’ could be inferred. Suicidal ideations (SIs) as well as the preparations for SA are not included in the diagnostic criteria. Furthermore, by explicitly differentiating SBD from the non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), the authors of the DSM-5 have put a strong emphasis on the intention of the individual at the time when the behaviours occur. This differentiation is crucial since affective/cognitive processes such as, e.g. the relief of negative feelings associated with NSSI are typically quite different from those related to SBD (Klonsky, Victor, & Saffer, Reference Klonsky, Victor and Saffer2014). Furthermore, Klonsky (Reference Klonsky2011) showed that NSSI is most often performed in the absence of SI. Therefore, this distinction has clinical relevance for designing interventions, specifically targeting subjects with SBD and on the other side subjects with NSSI (Turner, Austin, & Chapman, Reference Turner, Austin and Chapman2014), due to different psychological functions underlying both behaviours. Moreover, co-occurring mental illnesses could make the differentiation between SBD and NSSI difficult because it might be challenging to clearly assess the intent to die. Especially, borderline personality disorder (BPD), substance use and eating disorders are exhibiting greater rates of NSSIs, thus potentially confounding the diagnosis of SBD (Cipriano, Cella, & Cotrufo, Reference Cipriano, Cella and Cotrufo2017; Ose, Tveit, & Mehlum, Reference Ose, Tveit and Mehlum2021).

Beyond this, it is important to note that in the UK and other countries of the Commonwealth of Nations, the term regularly used in the guidelines is ‘self-harm’ (Excellence, 2020), which is usually defined as ‘self-poisoning or injury, irrespective of the apparent purpose of the act’. This definition confounds SBD with NSSI and thus obviously lacks the differentiation of self-injury with an intent to die or without. This is indeed a problematic issue when reviewing studies focusing on psychotherapeutic treatments of individuals with SBD.

A further critical issue, when comparing psychotherapeutic studies on SBD, is related to the outcome variables and to the differentiation between SI and SA. Although SIs are the first step on the pathway to SA, most individuals with SI do never attempt suicide (Klonsky, May, & Saffer, Reference Klonsky, May and Saffer2016). Clinical risk factors of SI and SA include many common but also some distinct features (Franklin et al., Reference Franklin, Ribeiro, Fox, Bentley, Kleiman, Huang and Nock2017; May & Klonsky, Reference May and Klonsky2016; Nock, Hwang, Sampson, & Kessler, Reference Nock, Hwang, Sampson and Kessler2010). In other words, it is relevant to consider suicidal ideas and suicidal acts as linked but different phenotypes and therefore to focus on treatment studies using suicide re-attempts/suicides as a primary outcome criterion.

Previous systematic reviews on the efficacy of prevention strategies combined psychosocial and psychotherapeutic treatments and reported divergent findings. Whereas the results of Gotzsche and Gotzsche (Reference Gotzsche and Gotzsche2017) suggest that such strategies reduced the number of subsequent SAs in the observation period, there was no evidence for such a conclusion in two other studies (Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Witt, Salisbury, Arensman, Gunnell, Hazell and van Heeringen2016; Riblet, Shiner, Young-Xu, & Watts, Reference Riblet, Shiner, Young-Xu and Watts2017). Another concern is that several studies included in these reviews investigated subjects with self-harm without clearly assessing the intent to die or including subjects with deliberate self-harm (DSH) without intent to die. Both issues may have contributed to the inconsistency of prior results.

The aim of the present systematic review and meta-analysis is therefore to identify and evaluate psychotherapeutic treatments for SBD which were explicitly designed to reduce the risk of a suicide re-attempt or suicide. In contrast to psychosocial interventions, only studies were included which explicitly used psychotherapeutic interventions to prevent future SA or suicide, according to the following definition of psychotherapy (Meltzoff & Kornreich, Reference Meltzoff and Kornreich1970): (1) psychological treatments stem from psychological theories about pathological processes causing specific mental impairments in individuals, (2) most of the applied psychotherapeutic methods are developed from the laboratories of psychological science based on those theories and (3) the purpose of psychotherapy is assisting people to modify their behaviours, cognitions, emotions in the functional direction.

Based on these above-mentioned issues, only randomized controlled trials (RCT) were included in this systematic review, which clearly differentiated suicidal self-harm from NSSI in terms of intent to die, applied psychotherapeutic interventions focusing on suicidal behaviour and finally used the suicide re-attempts as an outcome variable. The searching algorithm was also restricted to adults only (i.e. patients aged 18 years and older). Previous reviews focusing on suicidal behaviour in adolescents (e.g. Ougrin, Tranah, Stahl, Moran, & Asarnow, Reference Ougrin, Tranah, Stahl, Moran and Asarnow2015) have pointed out significant clinical distinctions between adolescent and adult patients.

Methods

Search strategy

A systematic search from 1980 to June 2020 was performed via the PubMed database. The following search terms were used: Psychotherapy OR acceptance-and-commitment-therapy OR cognitive-behavioral-therapy OR cognitive-behavioural-therapy OR cognitive-therapy OR dialectical-behavior-therapy OR dialectical-behaviour-therapy OR interpersonal-psychotherapy OR mentalization-based-treatment OR mindfulness-based-cognitive-therapy OR problem-solving-therapy OR schema-focused-therapy OR transference-focused-psychotherapy AND suicid*. By using the asterisk (*) as a wildcard, we were able to find all the terms that were relevant for our search, e.g. ‘suicidal behavio(u)r’, ‘suicidal ideation’ and ‘suicide attempts’. In addition to our search algorithm, reference lists of previous relevant systematic reviews (e.g. Gotzsche and Gotzsche, Reference Gotzsche and Gotzsche2017; Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Witt, Salisbury, Arensman, Gunnell, Hazell and van Heeringen2016; Riblet et al., Reference Riblet, Shiner, Young-Xu and Watts2017) were examined to identify further eligible studies that may have remained undetected by the employed search algorithm. However, we did not find any further eligible studies by this procedure.

Study inclusion

Studies were eligible for inclusion when they met the following criteria: (1) random allocation was used to assign participants to the intervention and control groups; (2) participants fulfilled the criteria of SBD as defined by DSM-5, (3) participants with self-harm were only included, if the intent to die or an expectation of the lethality of a SA was identifiable in the study definition of self-harm, (4) the trial evaluated the efficacy of a psychotherapeutic intervention, as defined above, relative to a control treatment, (5) SAs were used as an outcome measure, and (6) participants were 18 years or older at the point of randomization.

Additionally, eligible studies had to be published in a peer-reviewed journal indexed by PubMed database and/or Google Scholar. Case studies were excluded. The same applied to reviews and meta-analyses because a comprehensive presentation and discussion of these publications would have gone beyond the scope of this systematic review.

By this procedure, 6044 studies were identified. Fifteen additional publications were identified through other sources (reference lists of prior review articles). The further selection process is illustrated in Fig. 1 according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) checklist (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & Group, Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman and Group2009). After evaluation of these articles based on abstracts by two independent reviewers, the full-text articles of eligible studies were independently selected and reviewed by two investigators (TS and GW).

Fig. 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

Using the predefined inclusion criteria, 33 eligible RCTs were finally assessed. Eleven studies (Blum et al., Reference Blum, St John, Pfohl, Stuart, McCormick, Allen and Black2008; Davidson, Brown, James, Kirk, & Richardson, Reference Davidson, Brown, James, Kirk and Richardson2014; Gregory et al., Reference Gregory, Chlebowski, Kang, Remen, Soderberg, Stepkovitch and Virk2008; Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, McKeown, Day, Martin, O'Connor and Yule1987; Linehan, Armstrong, Suarez, Allmon, & Heard, Reference Linehan, Armstrong, Suarez, Allmon and Heard1991; Raj, Kumaraiah, & Bhide, Reference Raj, Kumaraiah and Bhide2001; Rudd et al., Reference Rudd, Rajab, Orman, Joiner, Stulman and Dixon1996; Slee, Garnefski, van der Leeden, Arensman, & Spinhoven, Reference Slee, Garnefski, van der Leeden, Arensman and Spinhoven2008; Tarrier et al., Reference Tarrier, Haddock, Lewis, Drake, Gregg and So2006; van Spijker, van Straten, & Kerkhof, Reference van Spijker, van Straten and Kerkhof2014; Weinberg, Gunderson, Hennen, & Cutter, Reference Weinberg, Gunderson, Hennen and Cutter2006) were excluded because the authors did not distinguish self-harm regarding the intent to die or included subjects with ‘intentional self-inflicted injury without intent to die’ or did not apply psychotherapeutic interventions. The study of Wei et al. (Reference Wei, Liu, Bi, Li, Hou, Tan and Liu2013) was excluded because only five patients out of 82 randomly assigned patients to psychotherapeutic intervention actually received psychotherapy in that study. Other patients refused psychotherapy (PT), so that no reliable conclusions can be drawn for the effect of psychotherapy on the risk for a suicide re-attempt. Furthermore, the study of Morley, Sitharthan, Haber, Tucker, and Sitharthan (Reference Morley, Sitharthan, Haber, Tucker and Sitharthan2014) was excluded, because it was not stated in the publication in which of the two conditions [cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) or treatment as usual (TAU)] the two reported SAs occurred. Unfortunately, the authors did not clarify this issue upon request. When the results of one study were published in more than one article (i.e. Davidson, Tyrer, Norrie, Palmer, & Tyrer, Reference Davidson, Tyrer, Norrie, Palmer and Tyrer2010; Davidson et al., Reference Davidson, Norrie, Tyrer, Gumley, Tata, Murray and Palmer2006), the results are presented here only once.

Thus, finally 18 studies were included in the present systematic review. The quality of studies was assessed independently by two authors (SJ and GW) according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Intervention. The primary outcome measure in this systematic review is the occurrence of suicide re-attempts and suicides.

Statistical analysis

The meta-analysis was conducted with Review Manager V5.3 combining results from the eligible studies, which reported our predefined primary outcome. To be comparable with other reviews, the pooled risk ratio (RR) using random-effects model and its accompanying 95% confidence interval as well as the odds ratio were calculated. The I 2 statistic was used to assess the between-study heterogeneity which indicates the percentage of variance between-study attributable to genuine differences between studies rather than the play of chance. The Cochrane Handbook (Higgins & Green, Reference Higgins and Green2008) suggested the following interpretation of I 2 values regarding the relevance of heterogeneity: 0–40% (unimportant), 30–60% (moderate), 50–90% (substantial) and 75–100% (considerable), which was followed in the present review.

Results

Eighteen eligible studies were identified according to our criteria, a detailed description is presented in Table 1. In total 1990 patients were included in the present analysis. The greater part of the studies (n = 10) used a cognitive-behavioural approach, whereas two studies employed psychodynamic approaches [mentalization-based treatment (MBT), brief psychodynamic interpersonal therapy] and three studies were based on dialectic-behavioural therapy (DBT). Three studies investigated problem-solving therapy (PST; a form of psychotherapy that relies on basic CBT strategies). The study of Stewart, Quinn, Plever, and Emmerson (Reference Stewart, Quinn, Plever and Emmerson2009) had two research arms (CBT and PST) and therefore was put in both categories (see above). The study of Celano et al. (Reference Celano, Beale, Mastromauro, Stewart, Millstein, Auerbach and Huffman2017) used a telephone-based psychotherapeutic intervention based on positive psychology (PP). Because this method was not comparable to the other psychotherapeutic approaches, this study was included in the pooled analysis from all studies together, but excluded from separate analyses.

Table 1. Characteristics of the included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) reporting the effects of psychotherapeutic interventions v. control conditions on suicide attempts (SA)

ASD, acute stress disorder; ASSIP, attempted suicide short intervention program; BD, bipolar disorder; BPD, borderline personality disorder; CBSP, cognitive-behavioural suicide prevention – therapy for suicidal behaviour; CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; CF, cognition focused intervention; C-MAP, culturally adapted manual-assisted problem-solving training; CTG, cognitive therapy group program; CT-SP, cognitive therapy for suicide prevention; DBT, dialectical behaviour therapy; DBT-I, individual dialectical behaviour therapy; DBT-S, dialectical behaviour therapy, skills training; DBTSTG, dialectical behaviour therapy, skills training group program; DD, depressive disorder; ED, eating disorder; EUC, enhanced usual care; h, hour; MDD, major depressive disorder; NSSI, non-suicidal self-injurys; PACT, post-admission cognitive therapy; PDIPT, psychodynamic interpersonal therapy; PP, positive psychology; PST, problem-solving therapy; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; SA, suicide attempt; SB, suicidal behaviour; SCM, standard case management; SFD, somatoform disorder; SI, suicidal ideation; SUD, substance use disorder; TAU, treatment as usual.

As depicted in Table 1, psychiatric diagnoses differed substantially across the included studies. In the CBT studies as well as in the studies using the psychodynamic approaches, the following disorders were reported: major depressive disorder (MDD), bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, eating disorders (ED), posttraumatic stress disorder, acute stress disorder, BPD and substance use disorders (SUD). In the DBT studies, patients mainly suffered from BPD that was partly combined with MDD, anxiety disorders, SUD and ED. In the PST studies, no psychiatric diagnoses were reported (please see Table 1). Sample sizes ranged from eight (Salkovskis, Atha, & Storer, Reference Salkovskis, Atha and Storer1990) up to 222 (McAuliffe et al., Reference McAuliffe, McLeavey, Fitzgerald, Corcoran, Carroll, Ryan and Arensman2014). In all included studies, non-parametric statistics were used for analysing differences in the number of re-attempts in the defined follow-up period, i.e. survival analyses, Fisher's exact test or logistic regression.

The mean age of the patients in the psychotherapy as well as in the control groups ranged from 20.40 (s.d. 0.76) years (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Ko, Wu, Oei, Lane and Chen2019) to 44.8 (s.d. 16.4) years (Celano et al., Reference Celano, Beale, Mastromauro, Stewart, Millstein, Auerbach and Huffman2017). In most studies, more females than males have been enrolled (see Table 1) and participants were diagnosed with one or more psychiatric diseases. Husain et al. (Reference Husain, Afsar, Ara, Fayyaz, Rahman, Tomenson and Chaudhry2014) and Pratt et al. (Reference Pratt, Tarrier, Dunn, Awenat, Shaw, Ulph and Gooding2015) did not provide information about the psychiatric diagnoses. Also, McAuliffe et al. (Reference McAuliffe, McLeavey, Fitzgerald, Corcoran, Carroll, Ryan and Arensman2014) included subjects with previous history of self-harm without reporting a potentially co-occurring psychiatric disease. The length of the follow-up periods ranged from zero up to 24 months (please see Table 1). Unfortunately, we were not able to perform specific subgroup analyses based on demographic or clinical characteristics due to the lack of this information for the suicide re-attempters in the follow-up period in the included studies.

As shown in the forest plot in Fig. 2, pooled analysis from 18 studies altogether yielded a significant difference in terms of numbers of suicide re-attempts between psychotherapeutic interventions in total and TAU or other control conditions, RR = 0.66; 95% CI 0.48–0.90; Z = 2.63, p = 0.008; OR 0.56, CI 0.36–0.84; p = 0.006. The between-study heterogeneity was moderate (I 2 = 51%).

Fig. 2. Forest plot and risk of bias evaluation of trials comparing the effect of psychotherapeutic treatments and control treatments [TAU (treatment as usual)] on suicide attempts and suicides.

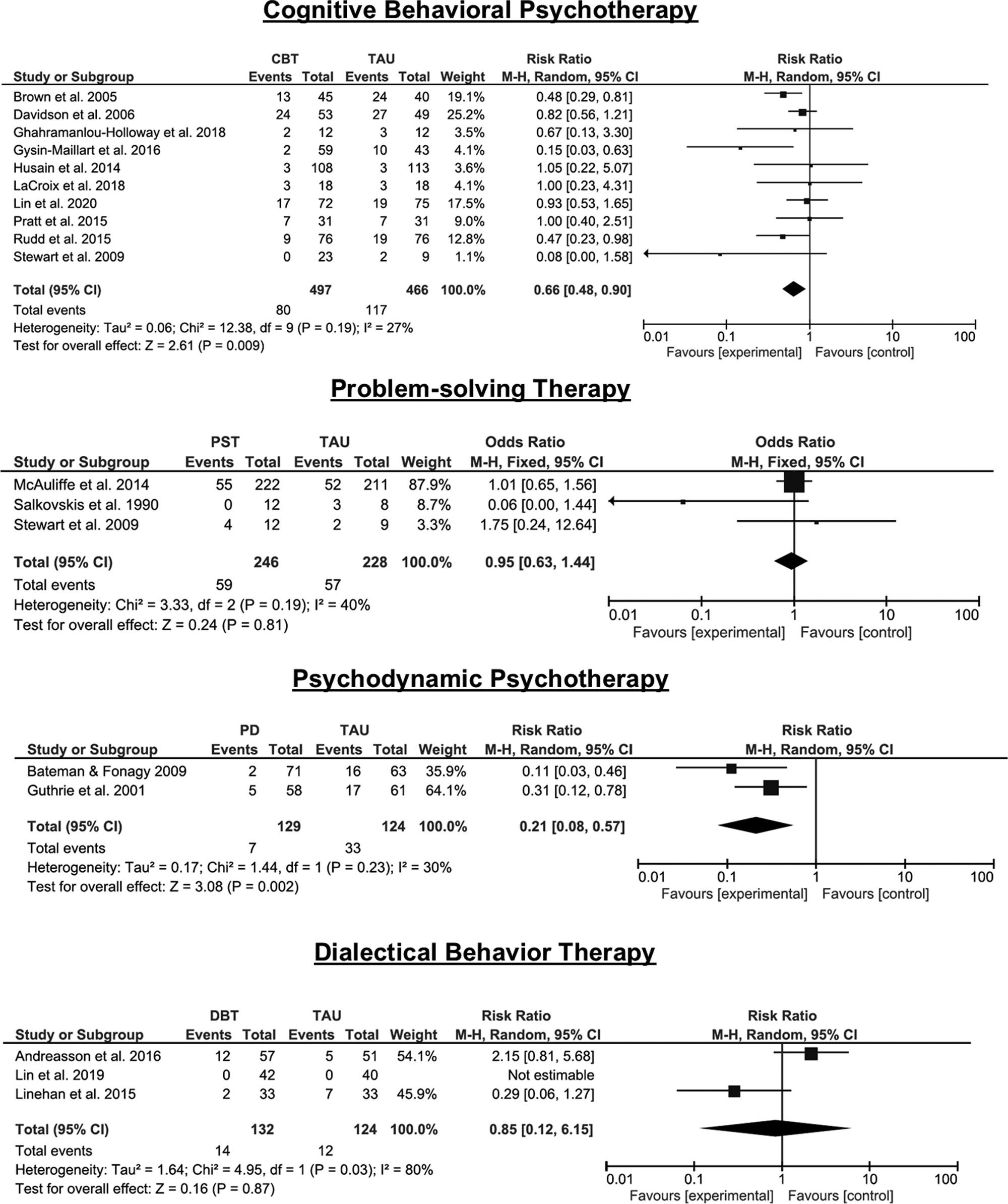

In addition, separate analyses were performed for studies using different psychotherapeutic approaches. As shown in the forest plot in Fig. 3, pooled analysis from 10 CBT studies yielded a significant difference in terms of numbers of suicide re-attempts between PT and TAU, RR = 0.66; 95% CI 0.48–0.90; Z = 2.61, p = 0.009; OR 0.53, CI 0.34–0.83; p = 0.005. The between-study heterogeneity was low and unimportant (I 2 = 28%). The two psychodynamic interventions (MBT, brief psychodynamic interpersonal therapy) also showed a significant impact on the number of suicide re-attempts, RR = 0.21; 95% CI 0.08–0.57; Z = 3.08, p = 0.002; OR 0.17, CI 0.06–0.45; p = 0.0004. The between-study heterogeneity was unimportant (I 2 = 30%). Studies using DBT and PST were not significantly more efficacious in reducing the number of suicide re-attempts than the control conditions.

Fig. 3. Forest plot of trials comparing the effect of specific psychotherapeutic treatments and control treatments [TAU (treatment as usual)] on suicide attempts and suicides.

A symmetric funnel plot as depicted in Fig. S1 (please see online Supplementary material) indicated that a publication bias is unlikely.

Some recently published studies included both, suicide attempters as well as ideators without a history of SA (Celano et al., Reference Celano, Beale, Mastromauro, Stewart, Millstein, Auerbach and Huffman2017; Davidson et al., Reference Davidson, Norrie, Tyrer, Gumley, Tata, Murray and Palmer2006; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Liu, Chen, Sun, Huang, Huang and Chiu2020; Pratt et al., Reference Pratt, Tarrier, Dunn, Awenat, Shaw, Ulph and Gooding2015; Rudd et al., Reference Rudd, Bryan, Wertenberger, Peterson, Young-McCaughan, Mintz and Bruce2015). However, most of the included subjects fulfilled the criteria of SBD. Thus, due to the high methodological quality of these studies, we decided to keep these studies in the main analysis of the present review.

To evaluate a potential bias due to the inclusion of patients with SI only, we performed an additional statistical analysis with studies only including patients with SBD. As shown in the forest plot in the online Supplementary Fig. S2, this analysis based on 13 selected studies with n = 1462 patients still showed a significant difference between PT and TAU or other control conditions favouring PT (RR 0.55; 95% CI 0.34–0.90; Z = 2.39, p = 0.02; OR 0.46, CI 0.25–0.85; p = 0.01). However, the between-study heterogeneity was substantial (I 2 = 62%).

Moreover, we conducted the same statistical analysis on CBT studies only. As depicted in online Supplementary Fig. S3, pooled analysis from six studies on CBT (n = 500 patients) showed a significant difference in the number of suicide re-attempts between PT interventions and TAU (RR 0.48; 95% CI 0.28–0.85; Z = 2.54, p = 0.01; OR 0.36, CI 0.17–0.77; p = 0.009). The between-study heterogeneity was unimportant (I 2 = 18%).

Based on these six studies, CBT decreased the risk of a suicide re-attempt nearly by a half.

Additionally, we performed a subgroup analysis regarding the duration of the follow-up period. In order not to confound the results by the type of PT, we performed this analysis for the CBT studies only. Short follow-up period was defined as ⩽6 months and long follow-up as ⩾12 months. As presented in Fig. 4, there was a non-significant effect of CBT (RR 0.85, Z = 0.52, p = 0.52) compared to TAU focusing on five studies with a short follow-up period (Ghahramanlou-Holloway et al., Reference Ghahramanlou-Holloway, LaCroix, Perera, Neely, Grammer, Weaver and Lee-Tauler2020; Husain et al., Reference Husain, Afsar, Ara, Fayyaz, Rahman, Tomenson and Chaudhry2014; LaCroix et al., Reference LaCroix, Perera, Neely, Grammer, Weaver and Ghahramanlou-Holloway2018; Pratt et al., Reference Pratt, Tarrier, Dunn, Awenat, Shaw, Ulph and Gooding2015; Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Quinn, Plever and Emmerson2009). But, there was a significant effect (RR 0.60, Z = 2.38, p = 0.02) in favour of CBT, when the studies with a long follow-up period (between 1 and 2 years) were compared to TAU (see Fig. 4; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Ten Have, Henriques, Xie, Hollander and Beck2005; Davidson et al., Reference Davidson, Norrie, Tyrer, Gumley, Tata, Murray and Palmer2006; Gysin-Maillart, Schwab, Soravia, Megert, & Michel, Reference Gysin-Maillart, Schwab, Soravia, Megert and Michel2016; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Liu, Chen, Sun, Huang, Huang and Chiu2020; Rudd et al., Reference Rudd, Bryan, Wertenberger, Peterson, Young-McCaughan, Mintz and Bruce2015). The RR was comparable to that when including all studies.

Fig. 4. Forest plot of trials comparing the effect of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and control treatments [TAU (treatment as usual)] focusing on five studies with a short-term follow-up (⩾6 months; see upper diagram) and with a long-term follow-up (⩽12 months; see lower diagram).

Discussion

The best predictor for a suicide re-attempt or suicide is a past history of an SA (Beghi, Rosenbaum, Cerri, & Cornaggia, Reference Beghi, Rosenbaum, Cerri and Cornaggia2013). For this reason, the present systematic review has focused on psychotherapy studies specifically tailored for patients with SA. Only studies were eligible, which used the number of suicide re-attempts and suicides in a defined period as an outcome measure. Thus, 18 studies with close to 2000 patients were included.

The main result of our study was that psychotherapeutic interventions were significantly more efficacious than TAU or other control conditions in reducing the risk for a suicide re-attempt nearly by a third.

Modest heterogeneity was observed potentially reflecting some differences between the types of applied psychotherapeutic interventions. Therefore, in a second analysis, the efficacy of different psychotherapeutic interventions was separately investigated. CBT interventions as well as psychodynamic therapies were found to be significantly more efficacious than the applied control conditions in reducing the number of suicide re-attempts. Trials employing DBT or solely problem-solving strategies did not significantly impact the probability for suicide re-attempts.

Comparison with previous systematic reviews

Thus, the present systematic review confers and extends the results of previous studies of D'Anci, Uhl, Giradi, and Martin (Reference D'Anci, Uhl, Giradi and Martin2019); Gotzsche and Gotzsche (Reference Gotzsche and Gotzsche2017) as well as of Calati and Courtet (Reference Calati and Courtet2016) showing that psychotherapeutic interventions and specifically the CBT are efficacious to reduce the risk for suicide a re-attempt. The prior reviews of Hawton et al. (Reference Hawton, Witt, Salisbury, Arensman, Gunnell, Hazell and van Heeringen2016) and Riblet et al. (Reference Riblet, Shiner, Young-Xu and Watts2017) on studies treating individuals with self-harm reported lower, but not significant odds for the probability of a suicide re-attempt after psychotherapeutic interventions compared to TAU.

Reasons for this discrepancy could be that the latter two reviews included studies, which used ‘self-harm’ as inclusion and outcome criteria defined according to the NICE criteria, thus irrespective of the intent to die. For example, Slee et al. (Reference Slee, Garnefski, van der Leeden, Arensman and Spinhoven2008) defined self-harm as self-initiated behaviour with the intent to harm the body regardless of intent to die. Weinberg et al. (Reference Weinberg, Gunderson, Hennen and Cutter2006) focused specifically on deliberate self-harm in patients with BPD, defining it as an intentional self-inflicted injury without intent to die. Furthermore, previous reviews included studies that applied both psychotherapeutic, but also psychosocial interventions (e.g. Gibbons, Butler, Urwin, & Gibbons, Reference Gibbons, Butler, Urwin and Gibbons1978; Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, McKeown, Day, Martin, O'Connor and Yule1987), which may also have an impact on the efficacy estimation. Thus, by focusing only on an SBD definition according to DSM-5 and on trials using specific psychotherapeutic approaches for preventing future suicidal behaviour in the present review, the heterogeneity between trials was reduced and putatively provided more specific results.

What are the common features between the psychotherapeutic interventions?

Most interventions were based on the principles of CBT, the efficacy of which has been proven in several psychiatric disorders by large RCTs (Butler, Chapman, Forman, & Beck, Reference Butler, Chapman, Forman and Beck2006). Due to an increased biopsychosocial vulnerability, patients' feelings of hopelessness and automatic negative thought, e.g. suicidal thoughts, can turn to a state that Beck labelled the ‘suicide mode’ (Beck, Reference Beck1976). In such ‘suicide mode’, the only option for solving life problems is to consider suicide. Thus, CBT for suicide prevention specifically aims at preventing the sliding into the ‘suicidal mode’. The core elements are therefore the reduction of the likelihood of subsequent SAs or suicide by (1) helping the individual detect and understand the triggering conditions for one's prior SA(s), e.g. in terms of a cognitive-behavioural case conceptualization; (2) training the individual specific strategies for preventing and managing a future suicidal crisis, for example, via safety planning; and (3) testing the individual to manage future suicidal crises by employing a relapse prevention task (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Ten Have, Henriques, Xie, Hollander and Beck2005; Ghahramanlou-Holloway et al., Reference Ghahramanlou-Holloway, LaCroix, Perera, Neely, Grammer, Weaver and Lee-Tauler2020; Rudd et al., Reference Rudd, Bryan, Wertenberger, Peterson, Young-McCaughan, Mintz and Bruce2015). Since the major focus of the attempted suicide short intervention program (ASSIP; Gysin-Maillart et al., Reference Gysin-Maillart, Schwab, Soravia, Megert and Michel2016) is similar regarding the above-mentioned treatment modules to CBT-based interventions, such as a cognitive case conceptualization, safety planning, relapse prevention, it was considered here as a CBT intervention.

Interestingly, by reanalysing the data from Rudd et al. (Reference Rudd, Bryan, Wertenberger, Peterson, Young-McCaughan, Mintz and Bruce2015), Bryan, Peterson, and Rudd (Reference Bryan, Peterson and Rudd2018) demonstrated that the benefit in favour of CBT was most pronounced in a group at high risk for suicide. Two studies (Davidson et al., Reference Davidson, Norrie, Tyrer, Gumley, Tata, Murray and Palmer2006; Davidson et al., Reference Davidson, Tyrer, Norrie, Palmer and Tyrer2010) demonstrated a significant long-term effect of a 12-month CBT intervention in the first year after treatment completion and a trend for a significant reduction of SAs relative to the TAU group over a period of 5 years after CBT, thus pointing towards sustainable effects of CBT.

In the present review, we additionally performed a subgroup analysis regarding the duration of the follow-up period and only observed a significant reduction in relative risk in studies using long follow-up period (12 months and more). This finding can be interpreted that a potential ‘sleeper effect’ (i.e. a delayed long-term effect of CBT) might have evolved (Tolin, Reference Tolin2010). However, the existence of the ‘sleeper effect’ is controversially discussed (Flückiger & Del Re, Reference Flückiger and Del Re2017) and the assumption of a delayed CBT effect cannot be justified based on the available data. A more plausible explanation is that a longer observation interval is necessary to obtain sufficient statistical power to detect significant differences between two interventions because suicide and SAs are relatively rare events.

Two studies used psychodynamic psychotherapy (Bateman & Fonagy, Reference Bateman and Fonagy2009; Guthrie et al., Reference Guthrie, Kapur, Mackway-Jones, Chew-Graham, Moorey, Mendel and Tomenson2001) and found a significant impact on suicide re-attempts in favour of the psychotherapeutic interventions. In contrast to other included studies, Bateman and Fonagy (Reference Bateman and Fonagy2009) used an exceptionally long treatment period of 18 months with weekly therapy sessions. The authors also did not report any follow-up results, only the results of the pre-post comparison were reported, whereby the comparability with other studies is limited. Furthermore, differences between MBT and structured clinical management regarding the number of SAs become evident solely during the last 6 months of treatment (used here as outcome). In the study of Guthrie et al. (Reference Guthrie, Kapur, Mackway-Jones, Chew-Graham, Moorey, Mendel and Tomenson2001), the complex and multifaceted brief psychodynamic interpersonal therapy was delivered by nurse therapists. This does not comply with professional standards. In our opinion, the studies performed by Bateman and Fonagy (Reference Bateman and Fonagy2009) and by Guthrie et al. (Reference Guthrie, Kapur, Mackway-Jones, Chew-Graham, Moorey, Mendel and Tomenson2001) do not allow for the final evaluation of the efficacy of psychodynamic treatments. The results, especially of Bateman and Fonagy (Reference Bateman and Fonagy2009), might however be promising for the development of future interventions.

Three studies (Andreasson et al., Reference Andreasson, Krogh, Wenneberg, Jessen, Krakauer, Gluud and Nordentoft2016; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Ko, Wu, Oei, Lane and Chen2019; Linehan et al., Reference Linehan, Korslund, Harned, Gallop, Lungu, Neacsiu and Murray-Gregory2015) investigated the effect of DBT in reducing the risk for a suicide re-attempt. There was a non-significant treatment effect for DBT on the frequency of suicide re-attempts, which was also reported by Riblet et al. (Reference Riblet, Shiner, Young-Xu and Watts2017). However, whereas there was a significant effect of DBT on the number of suicide re-attempts in the study of Linehan et al. (Reference Linehan, Korslund, Harned, Gallop, Lungu, Neacsiu and Murray-Gregory2015), Lin et al. (Reference Lin, Ko, Wu, Oei, Lane and Chen2019) did not report any suicide re-attempts in the DBT condition as well as in the control condition. In the third study by Andreasson et al. (Reference Andreasson, Krogh, Wenneberg, Jessen, Krakauer, Gluud and Nordentoft2016), DBT was not superior to the control condition in the form of collaborative assessment and management of suicidality (CAMS) treatment in reducing the number of SAs. The modest performance of DBT was unexpected. Nevertheless, the available data on this issue are still sparse. Moreover, methodological reasons, in particular differences in the control conditions between CBT and DBT trials, varying from basic usual care to CAMS treatment (Andreasson et al., Reference Andreasson, Krogh, Wenneberg, Jessen, Krakauer, Gluud and Nordentoft2016) or to a CBT group program (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Ko, Wu, Oei, Lane and Chen2019), may explain to some extent the reported differences in efficacy between DBT and CBT.

Further three trials (McAuliffe et al., Reference McAuliffe, McLeavey, Fitzgerald, Corcoran, Carroll, Ryan and Arensman2014; Salkovskis et al., Reference Salkovskis, Atha and Storer1990; Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Quinn, Plever and Emmerson2009) investigated the effect of PST, which relies on basic CBT strategies and therefore is often considered as a partial CBT approach. However, these studies had a specific focus on the training of interpersonal problem-solving skills and thus PST was conceptualized as a form of self-control training. There was a non-significant treatment effect for PST on the frequency of suicide re-attempts compared to PST. This result is also consistent with Riblet et al. (Reference Riblet, Shiner, Young-Xu and Watts2017).

Finally, Celano et al. (Reference Celano, Beale, Mastromauro, Stewart, Millstein, Auerbach and Huffman2017) applied a telephone-based psychotherapeutic intervention built on PP and compared it against a cognition-focused (CF) control intervention. In the CF condition, participants had to think of neutral events and to avoid assigning emotions to the events. There were no differences regarding suicide re-attempts between conditions. Surprisingly, the CF intervention was associated with greater improvements in depression, SIs and hopelessness at follow-up investigations after 6 and 12 weeks compared to the PP intervention.

Due to heterogeneous psychotherapy settings and study designs in the included studies, it is difficult to deduce general recommendations in terms of therapy format, duration, etc. Nevertheless, the main finding of the present review is that CBT with a specific focus on the last SA produced the most favourable results in terms of the reduction of suicide re-attempts. As shown by Gysin-Maillart et al. (Reference Gysin-Maillart, Schwab, Soravia, Megert and Michel2016), already three sessions of 90 min each could be sufficient to significantly reduce the risk for suicidal behaviour on the long term. However, more homogeneous RCT studies are needed to be able to make specific recommendations for psychotherapeutic treatment of patients after SA.

Finally, there are several published studies showing promising results of psychosocial interventions on reducing the risk for suicide re-attempts (Hvid et al., Reference Hvid, Vangborg, Sorensen, Nielsen, Stenborg and Wang2011; Mousavi, Amini, Mahaki, & Bagherian-Sararoudi, Reference Mousavi, Amini, Mahaki and Bagherian-Sararoudi2016). Jardon et al. (Reference Jardon, Debien, Duhem, Morgieve, Ducrocq and Vaiva2019) presented the VigilanS program in north-eastern France with post-discharge monitoring after a SA including (1) delivering a crisis card for first attempters, (2) giving a phone call for re-attempters to reassess their situation after discharge, and (3) sending personalized postcards for 6 months. Plancke et al. (Reference Plancke, Amariei, Danel, Debien, Duhem, Notredame and Vaiva2020) reported in their retrospective multicentre study favourable results regarding the effects of the VigilanS program on reducing suicide re-attempts. Stanley et al. (Reference Stanley, Brown, Brenner, Galfalvy, Currier, Knox and Green2018) compared a safety planning intervention plus telephone follow-up (SPI+) with a TAU control condition in a large-scale cohort comparison study. The authors reported that patients receiving SPI+ had a lower risk for suicide re-attempts than the TAU group.

In sum, there is growing evidence for specific psychosocial interventions targeting a reduction of suicidal re-attempts to become valuable clinical tools in health care. We therefore expect that in the future, hybrid approaches may prove particularly effective that combine the most efficient strategies of psychotherapeutic and psychosocial interventions.

Limitations of the present review

Firstly, we would like to point out that the studies included in this systematic review mainly have been published in high-income countries and therefore one should be careful about drawing general inferences regarding the developing and emerging countries. A recent bibliographic analysis of publications in suicidology in the last 30 years has shown that three-quarters of all publications were produced by Western countries, clearly dominated by the USA and the EU (Astraud, Bridge, & Jollant, Reference Astraud, Bridge and Jollant2020). For example, the publications' proportion of India, Turkey, Brazil and China is only 6%, although these countries add significantly to worldwide suicide numbers. Thus, a significant gap exists between the countries publishing the most about suicide and the countries where suicides are more often found (Astraud et al., Reference Astraud, Bridge and Jollant2020).

Secondly, the comparability of the studies included in this systematic review is affected by heterogeneous samples (see Table 1) with respect to psychiatric diagnoses, psychotropic medications and demographic characteristics (i.e. gender and age of participants).

Additional concerns are related to the treatment duration, the frequency of therapeutic sessions as well as to the therapeutic setting, i.e. individual v. group, which varies over the studies. For example, whereas Gysin-Maillart et al. (Reference Gysin-Maillart, Schwab, Soravia, Megert and Michel2016) or Salkovskis et al. (Reference Salkovskis, Atha and Storer1990) implemented in their trials three 60–90 min therapy sessions on a weekly basis or five sessions in 1 month, respectively, Davidson et al. (Reference Davidson, Norrie, Tyrer, Gumley, Tata, Murray and Palmer2006) conducted 16 sessions on the average across 1 year (Table 1) and Bateman and Fonagy (Reference Bateman and Fonagy2009) conducted weekly therapy sessions over 18 months. Finally, the TAU condition was often described insufficiently; it was considerably basic and differed across the studies, especially between CBT and DBT studies.

As presented in Table 1, there were also differences across studies regarding the qualification and the experience of the therapists. These ranged from mental health care nurses and licensed social workers to experienced master- or doctoral-levels clinicians, whereby part of the variability across studies may be explained. Systematic reviews consistently reported that across a range of therapies and diagnoses, a good alliance predicts positive treatment outcome (Horvath & Symonds, Reference Horvath and Symonds1991; Martin, Garske, & Davis, Reference Martin, Garske and Davis2000). Moreover, therapist variability seems to have a higher impact on treatment outcome in clinical trials than patient variability (Del Re, Flückiger, Horvath, Symonds, & Wampold, Reference Del Re, Flückiger, Horvath, Symonds and Wampold2012). In the study of Gysin-Maillart et al. (Reference Gysin-Maillart, Schwab, Soravia, Megert and Michel2016), the authors demonstrated a significant inverse relationship between the initial therapeutic alliance and the severity of SIs at 12 months follow-up. It is conceivable that the qualification and experience of the therapists have a major impact on both, the therapeutic alliance, and the efficacy of psychotherapeutic treatment. Thus, the significant effect of CBT studies observed in the present review could partly be explained by the higher number of studies but also possibly by the more homogeneous composition of therapists' qualification and experience.

Another related and important point is the low adherence of suicide attempters. In this regard, it is known that more than 50% of patients drop out after only one session (Lizardi & Stanley, Reference Lizardi and Stanley2010). For instance, in the study of Wei et al. (Reference Wei, Liu, Bi, Li, Hou, Tan and Liu2013), which was excluded from the present review due to the adherence issue, 94% of individuals with a preceding SA refused the CBT treatment. Therefore, improving the adherence of individuals after an SA by specifically focusing on the therapeutic alliance and thus empowering the motivation of individuals to work on past SAs may enhance the probability to stay in the psychotherapeutic treatment until its completion.

Finally, an important clinical question is whether single suicide attempters v. re-attempters might differ regarding their response to psychotherapeutic interventions. Previous studies showed significant differences between single and multiple suicide attempters in terms of sociodemographic and psychopathological profiles (Lopez-Castroman et al., Reference Lopez-Castroman, Perez-Rodriguez Mde, Jaussent, Alegria, Artes-Rodriguez and Freed2011; Mendez-Bustos, de Leon-Martinez, Miret, Baca-Garcia, & Lopez-Castroman, Reference Mendez-Bustos, de Leon-Martinez, Miret, Baca-Garcia and Lopez-Castroman2013) as well as poorer interpersonal functioning (Stoliker, Reference Stoliker2020). Thus, it is conceivable that the response to PT interventions might differ between single attempters and re-attempters. In this systematic review, 11 out of 18 included studies reported the number of multiple attempters among participants (see Table 1). The overall proportion of multiple attempters ranged from 25.8% (Gysin-Maillart et al., Reference Gysin-Maillart, Schwab, Soravia, Megert and Michel2016) to 85.7% (LaCroix et al., Reference LaCroix, Perera, Neely, Grammer, Weaver and Ghahramanlou-Holloway2018). In two of the studies, the multiple attempters were unequally distributed across intervention group and TAU group (ASSIP: 16.7%, TAU: 21%; Gysin-Maillart et al., Reference Gysin-Maillart, Schwab, Soravia, Megert and Michel2016; CT-SP: 46.1%, TAU: 30.3%; Rudd et al., Reference Rudd, Bryan, Wertenberger, Peterson, Young-McCaughan, Mintz and Bruce2015). Thus, given different clinical characteristics of single v. multiple attempters, a confounding effect of different group compositions might be expected on outcome measures. We therefore recommend for future studies the use of stratified randomization in order to avoid overrepresentation of patients with multiple SAs in treatment or control groups.

Conclusions

This systematic review has shown that psychotherapeutic interventions implementing CBT-related and potentially psychodynamic approaches and, moreover, specifically targeting previous suicidal behaviour are efficacious in the prevention of suicide re-attempts. Based on these encouraging results, it can be assumed that laying the focus on suicidal episodes might be the key intervention for preventing a suicide re-attempt. Considering the great significance of suicidal behaviour, there is unquestionably an urgent need for further development of psychotherapeutic techniques. It will be necessary to determine duration, frequency and intensity of specific psychotherapeutic interventions for optimal outcomes. Furthermore, there is a need for specific interventions targeting suicidal behaviour in elderly subjects, since the incidence of suicidal behaviour rises with increasing age (Nock et al., Reference Nock, Borges, Bromet, Alonso, Angermeyer, Beautrais and Williams2008). In comparison to that, most participants of the studies described in this review were in their 30s.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721003081.

Financial support

This work was supported by a research grant from the Bundesministerium für Gesundheit (BMG; Federal Ministry of Health, ZMVI1-2517FSB143).

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.