Introduction

What does it mean to shape labour market and unemployment policies towards sustainability? How can social rights and social justice be secured for present and future generations in a way that respects the principle of environmental sustainability at the same time? This paper sheds light on the understudied linkage between the challenge of unemployment and environmental sustainability by examining grassroots, community-based organizations and their work and employment situation. In its conclusion remarks, it contributes to the growing debate on the emergence of new ecosocial policies (cf. Gough, Reference Gough2013, Reference Gough2017).

In this article, we use empirical data based on a cross-national case study on community based-organizations we label ecosocial innovations (ESI) in four European countries – Finland, Germany, Belgium and Italy (cf. Matthies et al., Reference Matthies, Stamm, Hirvilammi and Närhi2019; Stamm et al., Reference Stamm, Hirvilammi, Matthies and Närhi2017). We define ESIs as small-scale associations, cooperatives, projects or organizations that create new integrative practices combining both social and environmental goals in the field of social and solidarity economy (SSE) (see eg. Utting, Reference Utting2015; Wallimann, Reference Wallimann2014). The concept of ESI developed for this cross-national study draws on theories and concepts on social innovation (eg. Mehmood & Parra, Reference Mehmood, Parra, Moulaert, MacCallum, Mehmood and Hamdouch2013; Moulaert et al., Reference Moulaert, MacCallum, Mehmood and Hamdouch2013). As attributed to social innovations in general, ESIs are fulfilling individual and collective needs at the same time. However, they combine new social practices with environmental goals, both in their own activities (as in a repair café or vegan social kitchen) and in their outcomes, services or products (as in bike rental or by selling organic vegetables) (see also Johanisová & Fraňková, Reference Johanisová, Fraňková and Anastasiadis2013; Science Communication Unit, 2014). The ESIs all have in common that a vast amount of “man- or womanpower” is needed for initiating, establishing and strengthening the social practices of the innovative organizations. However, this does not necessarily mean paid or gainful employment. Their foundation is rather a creative and sometimes chaotic mix of work, employment and volunteering (Stamm et al., Reference Stamm, Hirvilammi, Matthies and Närhi2017, p. 209).

The vast majority of labour market and unemployment policies are still widely unaffected by any discussion of an integrative sustainability or ecosocial transformation in Europe. The field of labour market and unemployment policies encompasses financial allowances for unemployed people, but also other benefits such as services (eg. employment promotion and activation programmes). Sustainability in this context mainly refers to financial or fiscal sustainability, leaving the social and ecological dimension completely out. This tremendous gap applies to most social security branches so far and is further reflected in the absence of research in this field. Only rather slowly, and yet far from mainstream discussions, this situation is changing in social policy or social work research, which this study is based on (eg. Cook, Smith, & Utting, Reference Cook, Smith and Utting2012; Fitzpatrick, Reference Fitzpatrick2011, Reference Fitzpatrick2014a, Reference Fitzpatrick2014b; Gough et al., Reference Gough, Meadowcroft, Dryzek, Gerhards, Lengfeld, Markandya and Ortiz2008; Gough, Reference Gough2013, Reference Gough2017; Matthies & Närhi, Reference Matthies and Närhi2017; Wallimann, Reference Wallimann2013).

This is the gateway for the main research question of this article: How are labour market and unemployment policies connected to ecosocial innovations in various countries and what lessons for developing new ecosocial policies can be learned from this connection? The originality of the article is its foundation in empirical data on small-scale community-based ESIs that can inform and influence future labour market and unemployment policies from a bottom-up perspective. The article begins with an overview of the research discussions on ecosocial policies, in which the natural environment and unemployment are interlinked. It will be shown how scarcely the link is discussed, and that even in the slowly growing but still limited body of work on climate change, social policy and sustainability, social security and the specific realm of labour market and unemployment policies play a marginal role. In the second section, we focus on ESIs and how their work and employment situation is linked to unemployment policies. The underlying hypothesis was that the work and employment situation within ESIs could lead to the discovery of public programmes or instruments with an ecosocial approach. We conclude by discussing the policy implications and prospects of new ecosocial policies.

Combining labour market and unemployment policies with environmental sustainability

In social policy research or policy papers on the future of social security over the last 20 years, sustainability is mainly discussed as fiscal, financial or monetary sustainability (eg. Brugiavini & Galasso, Reference Brugiavini and Galasso2004; Cooley & Soares, Reference Cooley and Soares1999; Euzéby, Reference Euzéby2012). Cahill (Reference Cahill2002) and Fitzpatrick (Reference Fitzpatrick, Fitzpatrick and Cahill2002) were among the first to stipulate a social policy shift towards environmental sustainability. Later the issues were brought up by Gough et al. (Reference Gough, Meadowcroft, Dryzek, Gerhards, Lengfeld, Markandya and Ortiz2008), eg. when displaying the multiple consequences of climate change and other ecological problems. Climate change, as the most visible ecological challenge, was seen as a new all-encompassing social risk, which is of a global nature and threatens the human welfare of current and future generations (Gough, Reference Gough2013, pp. 186–187).

The alarming ecological threats have proposed to cause a whole series of “new social risks” for the welfare state (cf. Johansson, Khan, & Hildingsson, Reference Johansson, Khan, Hildingsson, Koch and Mont2016; Schaffrin, Reference Schaffrin and Fitzpatrick2014). In order to address these new risks, Gough (Reference Gough2013, p. 198) sees that “social policy would need to combine with environmentalism to forge a unified ecosocial policy that can achieve ecologically beneficial and socially just impacts.” As a strategy for integrating social policy with climate change policy, he describes three measures: compensation, co-benefits and integrated ecosocial policies (Gough, Reference Gough2013, p. 196; see also Gough & Meadowcroft, Reference Gough, Meadowcroft, Dryzek, Norgaard and Schlosberg2011). He defines the ecosocial policies at another point as “policies that simultaneously and explicitly pursue both equity/justice and sustainability/sufficiency goals” (Gough, Reference Gough2017, p. 161). These kinds of ecosocial policies would help to provide all human beings with “a safe and just space” as proposed by Raworth (Reference Raworth2017) in her “doughnut model.” Ecosocial policies would enhance and “combine sustainable livelihoods with human wellbeing” (Gough, Reference Gough2017, p. 2). Another quite close concept is the framework of new social settlements (Coote, Reference Coote2015). These settlements would have three goals: “social justice, environmental sustainability and a more equal distribution of power” (Coote, Reference Coote2015, p. 8). Similar to Gough (Reference Gough2017) and other authors, Coote identifies work time reduction as one of the key measures for building new social settlements and achieving a “greener” society. Further ecosocial policies, like alternative food production and sharing groups, play a significant role in this development.

In studies on the future of work and employment, the link to the natural environment is only examined from the perspective of the green economy and green jobs, without focusing on the other side of the coin, unemployment and employment promotion (see eg. Angelov & Johansson, Reference Angelov, Johansson and Fitzpatrick2011; Cook et al., Reference Cook, Smith and Utting2012; Jackson & Victor, Reference Jackson and Victor2013). The International Labour Organization (ILO) has published numerous research papers and guidelines regarding the future of work and environmental sustainability (eg. International Labour Organization, 2018; Montt, Fraga, & Harsdorff, Reference Montt, Fraga and Harsdorff2018). The ILO prominently states that “economic activity and work cannot be understood independently from the natural environment in which they take place” (Montt et al., Reference Montt, Fraga and Harsdorff2018, p. V). It further emphasizes the importance of the decent work component in definitions of green jobs (International Labour Organization, 2018, p. 53) and identifies social protection as relevant for environmental sustainability. According to an ILO research paper by Montt et al. (Reference Montt, Fraga and Harsdorff2018, p. 28), social protection schemes can among others be adapted to meet environmental goals, for example in public work programmes with an environmental adaptation or mitigation component. Labour market or unemployment policies in detail as well as volunteering programmes are not discussed in ILO papers.

Often, the focus on paid work or gainful employment is also present in the literature on social policy and the environment when questioning the “work and spend cycle” and envisioning how to overcome it (eg. Cahill, Reference Cahill2002, p. 133). This critique is often linked to a new awareness of different forms of work – gainful employment, volunteering, care work and work for subsistence – and a feminist critic on the dominance of the male, full-time employment model (eg. Gibson-Graham, Cameron, & Healy, Reference Gibson-Graham, Cameron and Healy2013). A number of authors discuss social policy and social sustainability but limited to a certain city or a region (eg. Guillen-Royo, Guardiola, & Garcia-Quero, Reference Guillen-Royo, Guardiola and Garcia-Quero2017; Holden, Reference Holden2011) or they connect it to need theories and the concept of sustainable welfare (eg. Hirvilammi & Helne, Reference Hirvilammi and Helne2014; Koch & Mont, Reference Koch, Mont, Koch and Mont2016). Discussions on basic income and sustainability (eg. Andersson, Reference Andersson2009; Fitzpatrick, Reference Fitzpatrick, Fitzpatrick and Cahill2002) are also relevant in this context, but usually do not give detailed examples for new instruments for existing social security systems. Very few authors have so far sketched new ecosocial policies in detail related to labour market and unemployment policies. An exception is the concept of “green corps,” which is described simply as training programmes for unemployed people combining an environmental agenda with the overall goal of qualifying people for the labour market (cf. Forstater, Reference Forstater2003, Reference Forstater2006).

To sum up, all mentioned studies and concepts have one thing in common: they do not examine labour market and unemployment policies in detail as part of current social security systems in relation to environmental sustainability and not empirically based on existing practice examples such as ESIs. Clear gaps within the emerging debate on social policy and the environment become visible.

Case studies: materials and methods

The concept of ESI was developed for this cross-national study. Nevertheless, it is connected in various ways to other concepts, eg. innovations for sustainability (cf. Hargreaves, Longhurst, & Seyfang, Reference Hargreaves, Longhurst and Seyfang2013), sustainable innovations to ecosocial enterprises (Johanisová & Fraňková, Reference Johanisová, Fraňková and Anastasiadis2013) as well as grassroots or niche innovations (for sustainable development) (cf. Seyfang & Smith, Reference Seyfang and Smith2007). The field that ESIs are embedded in partly overlaps with what Jackson (Reference Jackson2009, p. 131) calls the “Cinderella economy,” which aims to reduce the use of resources and is set as an alternative to a consumption-based economy. Some ESIs are built as classical non-profit organizations with a clear bottom-up character and as an alternative to the market or public sector; others define themselves as social enterprises (cf. Defourny & Nyssens, Reference Defourny, Nyssens, Moulaert, MacCallum, Mehmood and Hamdouch2013; Clark & Johansson, Reference Clark, Johansson, Koch and Mont2016), sometimes with close ties to the market or public institutions.

Our empirical data of the cross-national multi-case study is based on an initial mapping phase conducted in five European countries, including the UK, leading to 50 ESIs as examples which best fulfilled the criteria of a local, innovative organization with a social and ecological agenda.Footnote 1 In the end, six cases were selected for a more in-depth case study. Three cases in Finland (due to the location of the research project) and one each in Germany, Italy and Belgium. Despite their different histories and path dependencies in their welfare state development, all four countries provide an elaborated set of labour market policies, including employment promotion or activation programmes combined with financial benefits, such as unemployment allowances and subsidized work schemes (cf. Schubert, de Villota, & Kuhlmann, Reference Schubert, Villota and Kuhlmann2016). All four countries have a national unemployment insurance system, some with different schemes for different age groups, and a social assistance system as a last resort allowance or minimum income system. In all countries, several labour market and unemployment policy reforms were implemented during the last 20 years, which basically followed the neoliberal activation turn, emphasizing, more than in the past, the goal of paid work and the individual duties of unemployed people (see eg. Kenworthy, Reference Kenworthy, Castles, Leibfried, Lewis, Obinger and Pierson2010; Knotz, Reference Knotz2018). Finland and Italy were hit hardest by the major economic crisis of 2008 and faced significant social policy reforms during the last 5–10 years (cf. Agostini & Natali, Reference Agostini, Natali, Schubert, de Villota and Kuhlmann2016; Kokkonen, Närhi, & Matthies, Reference Kokkonen, Närhi, Matthies, Kamali and Jönsson2018; Minas et al., Reference Minas, Jakobsen, Kauppinen, Korpi and Lorentzen2018; Saari, Reference Saari, Schubert, de Villota and Kuhlmann2016). In Finland, the activation measures were for a long time less coercive than in Germany for example (Busk, Reference Busk2016), but became stricter during the last five years (cf. Halmetoja, Wispelaere, & Perkiö, Reference Halmetoja, De Wispelaere and Perkiö2019). In Italy, unemployment policies are less centralized and regional instruments play a more significant role than in the other countries. In general, the activation turn was less influential in Italy (Agostini & Natali, Reference Agostini, Natali, Schubert, de Villota and Kuhlmann2016, p. 411). Germany had already conducted their significant reforms regarding unemployment benefits at the beginning of the twenty-first century and the economic crisis had surprisingly few effects on its unemployment policies (cf. Blum & Kuhlmann, Reference Blum, Kuhlmann, Schubert, de Vilotta and Kuhlmann2016; Zohlnhöfer, Reference Zohlnhöfer2011). Belgium on the other hand was partly forced to stay inactive due to a long phase of government crisis at the time of the economic crisis (cf. Marx & Schuerman, Reference Marx, Schuerman, Schubert, de Villota and Kuhlmann2016). Nevertheless, during the last five years, several reforms aiming for cost containment and higher pressure on unemployed people were introduced. Regional governments and administration also play an important role in Belgium, but compared to Italy, combined with strong national schemes. The different allowances and instruments as well as further descriptions on national idiosyncrasies are shown in the following section “Interlinkage between ESIs and public policies” including an overview.

In Finland, the innovations chosen consisted of an organic food cooperative based on the concept of community supported agriculture (Oma Maa, Helsinki area), a non-profit association defining itself as an open space for arts and culture (Hirvitalo, Tampere) as well as a centre of sustainable well-being, education and cultural activities (Lapinlahden Lähde, Helsinki). In the other three countries, the case studies were conducted with an association collecting, storing and up-scaling diverse second-hand and waste material (Kunst-Stoffe, Berlin/Germany), a social cooperative producing organic vegetables (Vinterra, Mals in South Tyrol/Italy) and a social enterprise providing training for young unemployed and promoting bike culture (VELO, Leuven/Belgium). The central part of the case study data consists of 28 semi-structured individual interviews as well as one group interview with narrative elements. We conducted two individual and one group interview within VELO, four interviews within Kunst-Stoffe, five interviews within Hirvitalo and Lapinlahde Lähde and six interviews within Oma Maa and Vinterra. The interviewees were founders and coordinators of the ESIs, employees and volunteers as well as users of their services such as trainees. For this study, we used a qualitative case-oriented and comparative approach. The focus is the connection between the ESIs and public policies in the field of labour market and unemployment policies. Instead of comparing indicators, the aim of the approach is to create knowledge and gain a better understanding of the connection in order to draw conclusions about ecosocial policies.

Interlinkage between ESIs and public policies

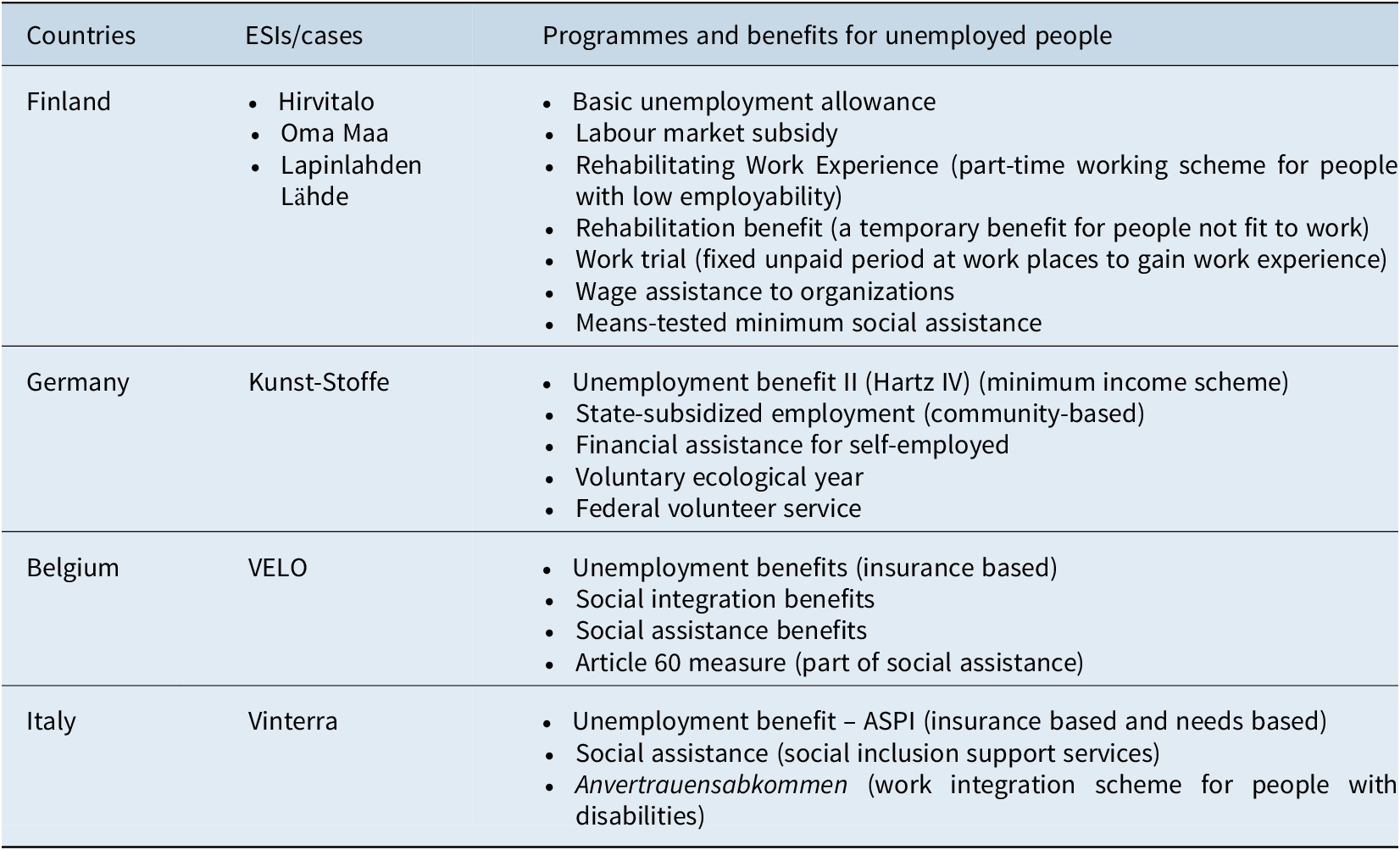

One central result gained from previous thematic analyses on the interview material was that they could all only be developed, established and maintained by a mix of different forms of employment, volunteering and publicly subsidized work (Stamm et al., Reference Stamm, Hirvilammi, Matthies and Närhi2017, p. 11). Table 1 provides an overview of the labour market instruments and unemployment benefits, services and financial benefits used by ESIs.

Table 1. Labour market instruments and unemployment benefits in ESIs.

The table already demonstrates in a compressed form the strong link between the ESIs and public programmes and benefits, and therefore also with regional and national public institutions related to unemployment. The labour market instruments and unemployment benefits, financial benefits as well as services like activation and employment programmes, but also volunteering programmes, play a significant role in keeping the activities of the innovations running. This became clear in all the interviews with founders and coordinators. The following summaries for each country will describe how the work of ESIs is connected to labour market and unemployment policies. These results serve as a basis for the concluding discussion on how these inter linkages could lead to new ecosocial policies, and what similarities and differences between the four countries involved could be identified.

Finland

The Finnish cases Oma Maa, Hirvitalo and Lapinlahden Lähde varied in terms of their organizational status, funding structure and field of activities. The smallest case, Hirvitalo (www.hirvikatu10.net), had no paid workers, but they could keep their art gallery open with the help of an unemployed person who conducted his/her work trial period or was entitled to wage assistance by the employment office. The activities in Oma Maa (www.omamaa.fi) were mainly based on voluntary work by people who were officially unemployed or self-employed, whereas Lapinlahden Lähde (www.lapinlahdenlahde.fi) relied on a small number of paid workers and volunteering. These various practices are partly explained by the deliberative differences in their origins and missions as well as inter linkages with labour market and unemployment policies.

In Finland, all unemployed jobseekers have to register themselves in a local employment office and thereafter they can receive unemployment benefits from the unemployment fund by trade unions or from the Social Insurance Institute, Kela. According to Kela, unemployment benefits can be paid to unemployed jobseekers between 17 and 64 years of age who are resident in Finland and “who are fit for work, are available to the labour market, look for a full-time job and are in need of financial assistance.” In addition to earnings-related unemployment allowances paid by the unemployment funds of trade unions, there are two different benefits that are paid by Kela: basic unemployment allowance and labour market subsidy. The former is paid to jobseekers who meet certain work requirements, whereas the latter means-tested benefit is directed to unemployed persons with no previous work experience or who have reached the maximum payment period of earnings-related or basic allowances (www.kela.fi/web/en/unemployment).

Some active participants who we interviewed in the Finnish ESIs were self-employed freelancers, students or in gainful employment somewhere else. Others were employed by the ESIs. However, there were also active participants who were recipients of different social benefits, mostly unemployment benefits plus additional housing benefits and last-resort social assistance. They lived in a paradoxical situation since they were fully occupied in creating the activities in ESIs, but in the eyes of the welfare institutions, they were categorized as unemployed or marginalized poor people.

In Finland, all unemployed people are objects of activation measures: they have to report to the employment office, actively seek jobs and accept work offers. Since 2001, the recipients of unemployed social assistance have been obliged to have an activation plan, in which officers from the Public Employment Service and social workers, together with the job seeker, agree to the most efficient pathways towards employment (see Minas et al., Reference Minas, Jakobsen, Kauppinen, Korpi and Lorentzen2018). The Finnish welfare systems aims to encourage unemployed people and social assistance recipients with the help of various activation programmes, such as Rehabilitating Work Experience, work trial and wage allowances. When taking part in these programmes, the unemployed person is entitled to unemployment benefits and a small daily allowance (nine euros per day). If a recipient refuses to participate in an offered activation measure, Kela has the right to reduce the level of social assistance by 20 per cent, and 40 per cent on the second refusal. This form of sanctioning is currently under revision by the new Finnish government, which was inaugurated in June 2019. Even though the Finnish constitution guarantees social protection for all, the minimum level, last-resort social assistance is made conditional.

The target of the Finnish policies is that all job seekers should participate in formal activation programmes rather than do informal volunteering. However, because officials cannot control all jobseekers, the social security system also leaves room for unemployed people to be active in various associations. Our interviews show that labour market subsidy and social assistance can be used for quite a long time without any disturbance, which enables people to be informally active in ESIs. If they informed the employment office that they are active in co-operatives, such as Oma Maa, they could be categorized as an entrepreneur, ie. a person who owns a company and is therefore not entitled to unemployment benefits. This rule can significantly reduce the incentives to be active in building ESIs.

Among our cases, Lapinlahden Lähde is the most established organization with an extensive use of various activation programmes. Due to the significant funding from European Social Fund, Lapinlahden Lähde has been able to employ three to four full-time workers. In addition, there are people who work with the help of the wage allowance. In the Finnish welfare state, an association can be entitled to a wage allowance measure, in which the state supports the association to employ a worker. First, the employment office has to agree with the length of the wage allowance period. With this system, both Lapinlahden Lähde and Hirvitalo have been able to hire workers and provide them with gainful employment. However, the amount of wage allowance positions is not fixed but depends on the state budget.

Lapinlahden Lähde has provided working possibilities for unemployed people with mental health problems and work disability under the scheme Rehabilitating Work Experience. Within the Rehabilitating Work Experience scheme, a long-term unemployed can work part-time according to his/her abilities. When taking part in the programme, the unemployed person is entitled both to the unemployment benefit and to a small daily allowance (nine euros per day). The organization that provides Rehabilitating Work Experience is required to have sufficient support for people with special needs and an official contract with authorities; therefore, Hirvitalo and Oma Maa have not used the scheme.

All cases had experiences of providing work trials for unemployed people. In practice, people who are officially unemployed can subscribe to employment officials to officially accept the work-trial period in public, private or third sector organizations. In most cases, the jobseekers can freely find the place for themselves and request that officials would accept the proposal and sign the contract. This was the case with Hirvitalo and Oma Maa as well, and they both emphasized that they did not want to accept people who were involuntarily posted there, or sent from the employment office without any previous knowledge of the organization and their mission. Due to the lack of professional social workers, they rather invite autonomous volunteers than engage forced unemployed people who are in need of guidance and support.

Germany

In the German case Kunst-Stoffe (www.kunst-stoffe-berlin.de), a registered association, a variety of different forms of subsidized employment, sometimes combined with financial unemployment benefits, as well as volunteering programmes, could be identified. During the time of the interviews (February 2018), only one person had a part-time employment contract.

The “standard” unemployment scheme in Germany is the Arbeitslosengeld (unemployment money) (ALG) II laid down in the German Social Code Book II. The benefits, as well as the system as a whole, is called Hartz IV by the majority of Germans, named after the far-reaching reforms of the early 2000s and one of the experts who envisioned them (see Adamy, Reference Adamy, Bispinck, Bosch, Hofemann and Naegele2012; Seeleib-Kaiser & Fleckenstein, Reference Seeleib-Kaiser and Fleckenstein2007). Unemployed people are entitled to receive the financial benefit of ALG II if they are not, or no longer, entitled to the insurance based ALG I. The financial benefit is paid monthly; costs for housing and energy and a few extra allowances are paid additionally. When someone receives ALG II and proves that they are “actively” seeking employment, they are also allowed to volunteer at the same time, if it does not hinder the job-seeking process (see also Stamm, Reference Stamm2015, Reference Stamm2017).

Many unemployed people receiving ALG II also work in so-called work opportunities with additional expenditure compensation. They are often called one-euro-jobs since unemployed people get an extra benefit of one to two euros per working hour. The one-euro-jobs are mostly offered to people who face long-term unemployment, and sometimes they are forced to take one of these work opportunities. Since this should not get in the way of real employment, they are mostly offered by the non-profit sector, including social work organizations. This is why an association like Kunst-Stoffe could be a suitable organization for unemployed people who want to or have to take a work opportunity. The interview partners emphasized several times that they would not accept anybody who had been forced to work there since this would not make sense for both parties.

Another model described by one of the interviewees was a certain form of state-subsidized employment. It was based on a combined state–regional programme and partly financed by the European Social Fund. It ended in 2012. In the case of Kunst-Stoffe, the programme was especially targeted at the cultural sector of Berlin. The programme was in use, eg. with one freelancing artist who had been given a three-year contract with Kunst-Stoffe. The salary was partly paid by the national programme and partly by the Federal states Berlin and Brandenburg. During the employment phase, the person was responsible for several educational projects with children and youngsters, and established the concept of repair-cafés within Kunst-Stoffe, which even up to today is one of the main successful projects of the association in several districts of Berlin. After the period of subsidized employment, the person became self-employed and received financial assistance from the BA (Federal Employment Agency) – another form of unemployment benefit especially for people trying to set themselves up as self-employed.

Two further German volunteering programmes are important for Kunst-Stoffe: the Voluntary Ecological Year and the Federal Volunteer Service. The first is an educational year that gives young people between the ages of 16 and 27 the possibility to become active in environmental protection. The programme has existed since 1986. It is often also taken as a gap year between school and studying or vocational training. The usual time period is 12 months of full-time work, and all participants are fully insured in the social insurance system and receive a “pocket money” of up to 330 euros per month. It is important to note that the programme is not part of the German social code and therefore not officially be part of unemployment policies. It is laid down in the Law on Youth Volunteering Services, which comes under the responsibility of the Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth (www.foej.de). The ministry is also politically responsible for the Federal Volunteer Service. It has only existed since 2011 and is open to all adults older than 27 years of age. The main sectors where volunteers can do volunteering work are the social, environmental and cultural sectors. The programme has been praised as a great success and the demand for participation is high. It is also possible to combine participation in the programme with the receipt of ALG II (www.bundesfreiwilligendienst.de).

In the ecosocial activities of Kunst-Stoffe, the work of volunteers coming from one of these two programmes is crucial. The official volunteers take on responsible tasks and learn a great deal, as the coordinators as well as the volunteers asserted in the interviews. An essential pre-condition is a genuine interest and high motivation for the main goals and activities of the association. The outline shows how strongly interlinked Kunst-Stoffe is with various public employment and volunteering programmes, often combined with unemployment allowances.

Belgium

The Belgian social enterprise, VELO (www.velo.be), located in Leuven, part of the northern Dutch-speaking Belgian region of Flanders, has the most employees among the cases involved. In total, around 120 people are active within the organization with approximately 55 full-time equivalents gainfully employed. In that sense, it is a very well-established employer in Leuven’s social economy sector. Nevertheless, VELO also cooperates with and strongly depends on the provision of unemployment benefits and employment programmes. It has established close working relations with the local social service OCMW (Openbaar Centrum voor Maatschappelijk Welzijn – Public Centre for Social Welfare, part of the Belgian system of social security) and the public employment service (VDAB) in Leuven.

The Belgian welfare state is known for having one of the most generous systems of unemployment benefits. Insurance-based unemployment benefits are still paid without a time limit. This is also the main reason why the number of social assistance recipients is comparatively low. Belgium has a comprehensive minimum income system, established in the 1960s and 1970s. Unemployed people who are not entitled to insurance-based unemployment benefits (because they do not qualify yet or have ceased to qualify) have a right either to social integration or to social assistance, regulated in two different legal acts. Both include financial benefits as well as employment promotion or active labour market programmes, which are often obligatory.

The Belgian welfare state has a multi-layered governance structure, in which the federal government plays only one role next to regional and local governments and administration (cf. Leibetseder et al., Reference Leibetseder, Gubrium, Dierckx, Fluder, Hauri and Raeymaeckers2017; Marx, Reference Marx, Schubert, Hegelich and Bazant2009; Marx & Schuerman, Reference Marx, Schuerman, Schubert, de Villota and Kuhlmann2016). Non-EU-citizens after five years of residence, as well as recognized refugees, are entitled to support under the social protection act. The costs are partly covered by the federal state. Expenditures for the right to social assistance are fully refunded by the federal state to the municipalities. The allowances and services are granted and handled by the OCMW (cf. Carpentier, Neels, & Van de Bosch, Reference Carpentier, Neels and Van de Bosch2017; European Union, 2018). During the last 20 years, the activation turn has also shaped the Belgian system of unemployment polices, leading to numerous new programmes and somewhat stricter obligations combined with possible sanctions for unemployed people. Due to the above-mentioned multi-layered governance structure, strong regional differences are prevalent.

VELO is, among other projects, offering training for young unemployed people. Nowadays, many of these young people (mostly men) are former refugees. Some of them are not yet officially registered as job seekers due to a lack of skills; first and foremost, many of them do not have sufficient language skills in Dutch. One important programme is the so-called article 60 measure (part of social assistance). People who are supported under this provision are not officially employed by VELO, but are given a contract with the local social services and are sent to VELO for training in metal work and welding, mostly practiced for fixing bikes; but also equally important, they receive language training, training in basic mathematics and technical knowledge. Moreover, they all receive social work support depending on their needs. Under the umbrella of the article 60 measure, they usually have a contract for one year. They receive social assistance or social integration-based benefits and get an extra benefit of one euro per hour when they work for VELO. During the time the interviews were conducted for the case study (September 2017), the subsidized period of training for the second group was shortened to only three months due to a policy decision at Flanders’ regional level, which, according to the social worker interviewed for the case study, made the accomplishment of the programme goals even harder. There is also a group undertaking work placements in another social economy organization, but who receive training at VELO as well. The long-term goal for these trainees is to find meaningful, gainful employment. Some of them can be officially registered as jobseekers after the training and therefore receive services from the public employment office VDAB. In some cases, this means they have already achieved a level of success given the severe problems that had faced them in entering the job market. Furthermore, the VDAB itself sends unemployed people to VELO. Some of these people are long-term unemployed for a variety of reasons.

Italy

The Italian case Vinterra (www.vinterra.it) and its relation to labour market and unemployment polices can only be understood by first looking at its legal status. Vinterra is a social cooperative, which is a very common form in Italy, particularly in the social sector (cf. Elsen, Reference Elsen, Matthies and Närhi2017, Reference Elsen2019). Overall, the role of the non-profit sector in Italy, or in other words, of actors of SSE, has increased during the last 25 years (Agostini & Natali, Reference Agostini, Natali, Schubert, de Villota and Kuhlmann2016; Natali, Reference Natali, Schubert, Hegelich and Bazant2009; Ranci & Montagnini, Reference Ranci, Montagnini, Evers and Zimmer2010). Vinterra is more precisely a social cooperative type B. These social cooperatives could be called social enterprises with a specific task. They follow the aim of supporting and re-integrating marginalized, deprived or socially underprivileged people. This group of people, in German sozial Benachteiligte, is defined in detail in a national law on cooperatives. Social cooperatives type B must have at least 30 per cent of their employees belonging to this group. The employees or workers are supposed to become members of the cooperative as well, depending on their capabilities.

In Italy, minimum income schemes as well as labour market policies are organized much more on the regional level than in the other three countries involved in the cross-national study (cf. Aurich-Beerheide et al., Reference Aurich-Beerheide, Catalano, Graziano and Zimmermann2015). There is still no nationwide system of minimum income protection, and in scope, the regional differences are huge (cf. Jessoula et al., Reference Jessoula, Kubisa, Madama and Zielenska2014; Madama, Reference Madama2013). The Autonomous Province of Bolzano was one of the first regions in the early 1990s to introduce a regional, means-tested minimum income scheme (cf. Natali, Reference Natali2018, p. 120). In South Tyrol, due to its economic strength, the minimum income system is one of the most established systems in Italy. Even though the number of recipients is still quite low, it has increased significantly during the last 10 years, partly caused by the economic crisis that hit the whole of Italy severely. Unemployment rates are still much lower than the national average (4.4 per cent in 2014), but are also on the rise after the economic crisis of 2008 (cf. Freie Universität Bozen, 2015).

The founding members of Vinterra run the cooperative on a voluntarily basis. Some of them are social workers working with people with mental impairments. According to the Italian law mentioned above, this group belongs to the labour market group of underprivileged people. One of the founding members of the cooperative has a professional background both as a social worker and as a farmer, and is therefore gainfully employed in Vinterra, for which he is mainly responsible for the farming. Unemployment benefits and subsidized work play a smaller role in Vinterra than in the other cases. The coordinators interviewed for the case study emphasized nevertheless their good relationship with the local unemployment office.

Vinterra mainly used one regional employment promotion instrument for underprivileged people: in this case, people with disabilities. With the so-called Anvertrauensabkommen, people with disabilities, in the case of Vinterra, mainly people mental impairments, could start working in the cooperative for a period up to three years. This work integration instrument is meant to enable people with disabilities to get to know a certain kind of work and the cooperative they are working in. In Vinterra, they are mainly responsible for growing, harvesting and selling organic vegetables. It can be seen as a form of apprenticeship. Furthermore, it is a form of subsidized employment because the unemployment office pays the salary. The contract is like any private employment contract embodied with social insurance contributions, which was valued by the workers we interviewed. The measurement is a successful instrument in South Tyrol that has existed for many years. The number of recipients is nevertheless rather small. In 2017, roughly 400 people with disabilities were supported by the programme (Abteilung Soziales, Reference Abteilung2017).

After the initial phase of the social cooperative, Vinterra was able to gainfully employ a number of people who started to work, subsidized by the unemployment office. The biggest challenge regarding the labour costs for Vinterra is the seasonal character of farm work. In winter months, they created smaller side projects in order to provide their employees with reasonable work. During the harvest time, on the other hand, more workers than employed are needed. In this case, as some of the coordinators reported in the interviews, recognized refugees, who are in general facing multiple difficulties in the Italian labour market (cf. Fullin & Reyneri, Reference Fullin and Reyneri2010), were hired for a limited period.

Summary

The previous sections draw a clear picture: the ESIs in all four countries are closely connected, or in other words, depend on labour market and unemployment policies. This is the clearest similarity between all four ESIs in the selected countries. The already-mentioned creative, sometimes also chaotic, and often complex mix of employment, volunteering, subsidized employment and self-employment within the ESIs is only possible with public support, even though the support systems are sometimes unreliable or fragile. As the interview material revealed, successful and even essential programmes – for the ESI and their clients and workers – are the target of cutback measures (see VELO) or meaningful regional employment promotion programmes are discontinued, as in the case of Kunst-Stoffe. Nevertheless, the public programmes and instruments make it possible for ESIs to maintain their activities because they enable, on one hand, the participants to get some form of income, and on the other, the organizations to recruit a labour force.

The results also show that interdependency has often been established between the ESIs and public institutions, such as employment offices, job centres or social administration. These institutions also rely on the training opportunities and professional work of some of the ESIs (mostly VELO, Vinterra). The underlying hypothesis that by examining the work and employment situation of ESIs, programmes or instruments in the field of labour market and unemployment policies, specifically targeted at environmental goals, could be found or discovered, was not confirmed. Based on our limited data on ESIs, all countries lack a direct connection between the social policy field and environmental sustainability. Only the German “voluntary ecological year” for young people up to age 27 combines social and environmental goals. The programme combines its environmental agenda with social goals, such as educating, qualifying and including young people in society. However, as described, it is not officially part of labour market policies or even of social policy (German Code of Social Law) in general.

A further similarity of the countries involved is that they leave the ESIs at least some discretion for creatively using their programmes and instruments. At the same time, on the level of policy implementation differences can be observed. Finland seems de facto to permit unemployed people the most freedom to choose their way of volunteering or doing subsidized work, while they are receiving unemployment allowances. This degree of freedom varies though, depending on the age of the beneficiary, their educational level and the duration of unemployment. In Belgium, the unemployment support system is quite generous, but this counts mostly for the unemployment insurance allowances. The social integration and social assistance systems are less generous, and as the example of the article 60 measure in the case of VELO has shown, certain instruments under the legal umbrella of these systems are at risk. Germany and Italy are somewhat stricter regarding sanctions, and a creative way of using available time for unemployed people is limited. In the interviews, it also became clear that increasing pressure and control of unemployed people does not serve their needs in many cases, particularly regarding their engagement in ESIs. This became most visible in the German case Kunst-Stoffe and in Hirvitalo in Finland, in which interviewees reported that certain workers could not continue their engagement or volunteering because the local job centre did not recognize their work at the ESI as meaningful in a sense that it could enhance their employability.

The differences between the countries involved can be described as national idiosyncrasies. This does not refer to the connection between ESIs and public policies (which often just depends on the legal status and the main activities of the ESIs), but more to the existing policies. Despite the common goal of activation, all countries certainly have particular instruments or programmes, which are unique. Nevertheless, some of these have the potential to be adopted by other countries and could be turned into new ecosocial policies in the field of labour market and unemployment policies. In Belgium, one example for these instruments or programmes is the article 60 measure, which could be combined with an ecological goal setting. In Italy, it is the special role of cooperatives, which are not yet closely linked to sustainability goals. In Finland, the work trial or Rehabilitating Work Experience could be an example. These programmes are already often connected to ecosocial practices but only as a side effect (eg. by establishing a gardening project or using second-hand material for workshops). Finally, in Germany, the volunteering programmes could be used as a model and extended to other groups in need of work and qualifications.

Discussion and concluding remarks

The results of the cross-national case study can be combined into three main lessons or recommendations on how to reach new ecosocial policies in the field of labour market and unemployment policies. These concluding remarks can also be considered as preliminary policy recommendations towards an ecosocial welfare state (Gough, Reference Gough2013, Reference Gough2017). The lessons can be applied to three levels – the sectoral level, the organizational level and the individual level. All are strongly interlinked, but for analytical reasons, they are divided here. The first lesson or recommendation becomes clear by looking at VELO in Belgium and Vinterra in Italy. The examples show how important public support is for certain sectors of SSE against an unsustainable, only for-profit thinking. In the case of VELO the city has been promoting the local social economy for a considerable time and therefore helped organizations like VELO and others to flourish, eg. in the field of waste reduction and second-hand use. The case study of Vinterra demonstrates the importance of public support for the cooperative sector (see also Elsen, Reference Elsen2018). This is a distinct national trait of Italy, but the sector is further promoted by regional instruments in South Tyrol. Without the support, eg. in form of tax refunds and employment programmes, cooperatives such as Vinterra could not exist and compete in the market (in the case of Vinterra, against conventional farmers). What is lacking in both cases is a clear connection with sustainability goals. In conclusion, the examples show that policy-makers would not necessarily have to invent new ecosocial policies, such as new programmes or instruments, for unemployed people. By supporting whole sectors, such as the cooperative sector within SSE, many effective ecosocial ideas and programmes, which are eg. visible in the work of ESIs, could automatically find their way into practice (eg. Utting, Reference Utting2018). This means more sustainable and decent jobs or subsidized work places could be created in these sectors. The second lesson to be learned refers directly to the ESIs. The overall project this cross-national research is based on has, first, shown that numerous ESIs exist across Europe (see Matthies et al., Reference Matthies, Stamm, Hirvilammi and Närhi2019) and, second, how most of them creatively and successfully have implemented their ideas. Yet, despite the described interdependency between ESIs and public institutions in the field of labour market and unemployment policies, the work of ESIs is not valued enough. In most cases, time, money and public acknowledgement are scarce or largely missing. Therefore, what would be needed on the organizational level is a national or regional policy programme to promote sustainable organizations, such as the ESIs. The environmental goals of the ESIs could be obligatorily merged with social and economic goals, such as social security, a minimum income, education as well as inclusion in cultural activities. The ESIs themselves could widen their networks and their practices could be further developed, and in some cases, could even become a standard in every city. Examples from our data are the re-use concept of Kunst-Stoffe in Berlin or the organic food bags invented by Oma Maa in the Helsinki area. These processes could be closely connected to unemployment support programmes. Furthermore, currently existing social enterprises or other associations that offer training, qualifications and work opportunities for unemployed people could learn from ESIs, so that integrating environmental sustainability in their services and programmes could become a legal requirement for all organizations in the field. The third lesson or recommendation refers to the individual level, which means programmes and measures for unemployed people. As the country-specific accounts show, a clear connection between unemployment policies and environmental sustainability is missing in all four countries. This also means in the situation where an unemployed person requests to participate in a training or qualification programme that is targeted at environmental goals, public employment services could not systematically fulfil such requests. One solution is to give unemployed people enough freedom to search for and undertake volunteering work, eg. in ESIs, while they are receiving unemployment allowances. It could also give them enough time to do subsistence work on an individual level, growing their own food for example. The Finnish employment offices seem to give the most “leeway” to unemployed people in this sense, but only informally. The problem remains that opportunities for unemployed people might not be available if organizations such as ESIs are not supported in a systematic way. Furthermore, clear legal regulations would mean more security for unemployed people. At the moment, they would still fear the threat of sanctions if they do not actively search for gainful employment and enhance their employability and instead work as volunteers. In Germany, the option to volunteer and receive unemployment allowances is only possible through participation in the Federal Volunteer Service. A better and, with regard to the long term, more sustainable solution would be to create specific new programmes with a clear ecosocial approach. These programmes could be quite similar to what Forstater (Reference Forstater2003, Reference Forstater2006) introduced as green corps. Sustainable solutions could also be subsidized work programmes, such as the national–regional programme in the case of Kunst-Stoffe or the Anvertrauensabkommen in South Tyrol, connected with environmental goals. A precondition would certainly be to have organizations offering places to conduct such programmes. This depends on the realization of the first two recommendations. Furthermore, suggested ecosocial policies such as work time reduction (eg. Coote, Reference Coote2015; Gough Reference Gough2017) are linked to the individual level, in the form of work contracts, but certainly would eventually need collective agreements including unions, employers’ organizations and the state. Even a basic income scheme, connected with environmental sustainability (cf. Andersson, Reference Andersson2009) could be part of lesson three, but would certainly mean a much bigger restructuring of the current (welfare) state and the relationship between the state and individuals.

No matter what, work and employment, and therefore also labour market and unemployment policies, are decisive for a sustainable future. They have always sought to fulfil economic and social objectives both for the individual and society. However, in times of climate change and other ecological threats, the goal of environmental sustainability needs to be considered much more (see also Koch & Mont, Reference Koch, Mont, Koch and Mont2016). Labour market and unemployment policies will have to change concertedly with a changing economy and shift towards an understanding of the social as always connected to the natural environment. The role of community based systems, commons and co-production will become more important (cf. Coote, Reference Coote2015). However, as Gough (Reference Gough2017) states, an ecosocial transition will not happen in a constructive way by accident but will require design (p. 192) and an active state. Social policy research is slowly opening up to sustainability, but as the case study material proves, the process of policy-change has not yet begun in the field of labour market and unemployment policies. It is very likely that local partners, such as the ESIs presented here, will play a more significant role in the future.

Acknowledgements.

We wish to acknowledge the Academy of Finland (no. 285868) for funding the research project. We also appreciate our colleagues in the networks and the participants in the ESIs who provided us with access to the field and data. We also wish to acknowledge Sarah Metcalf for helping us proofread the text.